Abstract

Background and purpose:

Acute intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of cholecystokinin (CCK) is known to induce a significant, but short-lasting, reduction in food intake, followed by recovery within hours. Therefore, we had covalently coupled CCK to a 10 kDa polyethylene glycol and showed that this conjugate, PEG-CCK9, produced a significantly longer anorectic effect than unmodified CCK9. The present study assessed the dose–dependency of this response and the effect of two selective CCK1 receptor antagonists, with different abilities to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), on PEG-CCK9-induced anorexia.

Experimental approach:

Food intake was measured, for up to 23 h, after i.p. administration of different doses (2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 μg kg−1) of CCK9 or PEG-CCK9 in male Wistar rats. Devazepide (100 μg kg−1), which penetrates the BBB or 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1), which does not cross the BBB, were coadministered i.p. with PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) and food intake was monitored.

Key results:

In PEG-CCK9-treated rats, a clear dose-dependency was seen for both the duration and initial intensity of the anorexia whereas, for CCK9, only the initial intensity was dose-dependent. Intraperitoneal administration of devazepide or 2-NAP, injected immediately prior to PEG-CCK9, completely abolished the anorectic effect of PEG-CCK9.

Conclusions and implications:

The duration of the anorexia for PEG-CCK9 was dose-dependent, suggesting that PEGylation of CCK9 increases its circulation time. Both devazepide and 2-NAP completely abolished the anorectic effect of i.p. PEG-CCK9 indicating that its anorectic effect was solely due to stimulation of peripheral CCK1 receptors.

Keywords: cholecystokinin, PEGylated cholecystokinin, anorexia, dose–response, CCK1 receptor antagonists, devazepide, 2-NAP

Introduction

It is generally accepted that the gut peptide, cholecystokinin (CCK), is involved in the short-term regulation of the energy balance. CCK has been subject to many studies since its first description in 1927 (Ivy and Oldberg, 1927). However, there is still no consensus about how endogenous CCK causes meal termination. Studies in a number of animal species indicate that pretreatment with devazepide (L-364.718), a specific antagonist of both central and peripheral CCK1 receptors, completely abolishes the inhibitory effects of exogenous CCK on food intake (Weller et al., 1990; Smith and Gibbs, 1992, 1994; Weatherford et al., 1992). Furthermore, systemic administration of devazepide increases meal size in several species (Hewson et al., 1988; Ebenezer et al., 1990; Bado et al., 1991; Reidelberger et al., 1991; Weatherford et al., 1993; Covasa and Forbes, 1994; Ebenezer and Baldwin, 1995). These results suggest that endogenous CCK, released from the small intestine during a meal, results in satiety via the activation of CCK1 receptors. Other studies have shown that systemic administration of the specific CCK1 receptor antagonists, 2-naphthalenesulphonyl 1-aspartyl-(2-phenethyl) amide (2-NAP) (Baldwin et al., 1994; Ebenezer and Baldwin, 1995) or A70104 (Ebenezer, 2003), which do not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (Baldwin et al., 1994), does not increase meal size, although pretreatment with these drugs blocks the anorectic effect of intravenous CCK. These studies support the hypothesis that endogenous CCK plays a role in the regulation of food intake via activation of central CCK1 receptors (Baldwin et al., 1998). However, Reidelberger etal. (2003) showed that doses of A70104 did increase food intake in rats, challenging the above-mentioned hypothesis.

We have examined previously the physiological effects of simmondsin, an anorectic glucoside extracted from the jojoba plant (Simmondsia chinensis), and hypothesized that its anorectic effect might be caused by interference with the CCK signalling pathway (Cokelaere et al., 1995; Flo et al., 1998, 1999, 2000; Lievens et al., 2003). A direct comparison of simmondsin- and CCK-induced anorexia is hampered by the short anorectic action of CCK. To compare the effects of simmondsin with those of CCK, we prolonged the anorectic effect of CCK by coupling the hormone covalently to distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine via a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) spacer (De Cuyper et al., 2004). More recently, we successfully PEGylated CCK9 (molecular weight of the PEG fraction from 5 to 30 kDa) and we demonstrated that intraperitoneal (i.p.) bolus injection of rats with PEGylated CCK9 resulted in a prolonged anorectic effect compared to the unmodified molecule, the 10 kDa PEG-CCK9 being the most active (León-Tamariz et al., 2007). PEGylation is a recently developed method, in which a flexible strand or strands of PEG is covalently attached to a protein or small drug molecule, improving the pharmacokinetics of the PEGylated molecule (Abuchowski et al., 1977a; Veronese and Pasut, 2005). This newly synthesized PEG-CCK9 provides the means for investigating the importance of CCK in the control of feeding behaviour and whether endogenous peripheral CCK acts as a satiety signal.

In the present study, we first examined the anorectic potency of different doses of PEGylated CCK9 (10 kDa) given i.p. to free-feeding rats. We also investigated whether 10 kDa PEG-CCK9 induced its anorectic effect by stimulating peripheral and/or central CCK1 receptors by comparing the antagonistic effects of devazepide and 2-NAP on the 10 kDa PEG-CCK9-induced anorexia.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (Janvier, Le Genest Saint Isle, France), weighing 268±16 g at the start of the experiment, were housed individually in iron-wired cages (room temperature of 21±0.2°C, 40–60% relative humidity, reversed 12:12 h light–dark cycle with lights on at 2100 hours and lights off at 0900 hours), following national guidelines on animal care. Water and complete powdered rodent food (Sniff, Bioservices, Schaijk, The Netherlands) were provided ad libitum. Food intake was measured by weighing the mangers, which are specially designed to avoid spillage (Scholz, Overijse, Belgium). Animals were adapted to the experimental conditions and i.p. injections at least 10 days before the start of the experiment.

Experimental design: Experiment 1: dose-dependent effects of unmodified and PEGylated CCK9 on food intake in rats

Two series of experiments were performed. The first determined the dose–response relationship of unmodified CCK9 and the second that of PEGylated CCK9. The same rats were used in both series with 1 week of recovery between both series.

Dose–response relationship of unmodified CCK9.

The rats were divided into three groups of 10. The start of the food intake was synchronized by 1 h fasting before lights off. To test all five doses, two test periods were needed; these were separated by a 1 week recovery period during which the rats received no treatment. Each test period consisted of two consecutive days, the control day, on which all three groups received an i.p. injection of mPEG-OH dissolved in 0.5 ml saline, and the treatment day, on which each group received a different dose of i.p. injected unmodified CCK9 (2, 4 and 8 μg kg−1 in the first test period; 8, 16 and 32 μg kg−1 in the second test period). The test on the 8 μg kg−1 dose was repeated to check the reproducibility and to determine if there was a time effect caused by the recovery week. The data from the second test of the dose of 8 μg kg−1 were not included in subsequent analyses. All injections were given at 0845 hours, 15 min before the start of the measurements. Food intake was measured at time zero (0900 hours), after 30 min and 1 h, then every 1 h for 8 h. As there was no significant difference in control food intake between the three groups, the food intake data of the preceding control day were pooled and compared with the food intake data for each group on the treatment day.

Dose–response relationship for PEGylated CCK9.

The experimental design was identical to the design used in the preceding experiment except for one extra measurement at 23 h.

Experiment 2: effect of devazepide on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition

To test whether PEGylated CCK9 exerts its anorectic effect by activation of CCK1 receptors, devazepide, a specific CCK1 receptor antagonist, was coadministered with PEGylated CCK9. A dose of 6 μg kg−1 PEG-CCK9 was used, since experiment 1b indicated that its anorectic effect on cumulative food intake lasted for at least 6 h. Four groups of eight rats were used. One received an i.p. injection of mPEG-OH (32 μg kg−1), one an i.p. injection of devazepide (100 μg kg−1), one an i.p. injection of PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) and one an i.p. injection of devazepide (100 μg kg−1) immediately followed by an i.p. injection of PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1). Devazepide was administered as a single bolus injection, as it has a relatively long plasma half-life of over 4 h (Reidelberger et al., 2003). To synchronize the start of food intake, the rats were fasted 1 h before the start of the dark period. All test substances were injected at 0845 hours, 15 min before lights off and renewed access to food. Food intake was recorded at 1, 6 and 23 h after the start of the dark period.

Experiment 3: effect of 2-NAP on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition

Duration of the in vivo effect of 2-NAP.

The biological half-life of 2-NAP in vivo had not been determined previously. This series of experiments was performed to establish the time course of the ability of 2-NAP to inhibit CCK9- or PEG-CCK9-induced anorexia in vivo. Test rats were deprived of food for 6 h (from 0800 hours until 1400 hours), then were given free access to food. Four groups of eight rats received an i.p. injection of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1), 6, 4, 2 or 0 h before an i.p. injection of CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) or PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1), given 10 min before renewed access to food. Food intake was measured 30 min later and compared with that in 6 h food-deprived rats given either an i.p. injection of mPEG-OH (32 μg kg−1) or CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) or PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1), as appropriate, 10 min before food was re-supplied.

Effect of 2-NAP on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition.

To distinguish between a central or a peripheral mode of action of PEGylated CCK9, the effect of 2-NAP on the PEGylated CCK9-induced anorexia was investigated using the same protocol as in the devazepide experiment (experiment 2), except that, since the previous experiment (3a) showed that the antagonistic effect of 2-NAP on CCK9- or PEGylated CCK9-induced anorexia was halved within 2 h, the i.p. 2-NAP injection (3 mg kg−1) was repeated every 2 h for 6 h and the two other groups received an i.p. saline injection to create the same injection-induced stress. The four treatments were (i) i.p. injection of mPEG-OH (32 μg kg−1), (ii) i.p. injection of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1), (iii) i.p. injection of PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) or (iv) i.p. injection of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1) followed immediately by i.p. injection of PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1).

Data analysis and statistical procedures

The dose dependency of the initial intensity of anorexia was analysed by plotting food intake (g) measured at 0.5 h (Y) vs log dose (X) and was fitted by linear regression (Figure 2). To examine the effect of dose on the time course of the anorectic effect, mean cumulative food intake was represented as a percentage of control food intake, resulting in dose–response curves over time (Figures 1a and b). Each response curve was fitted with a sigmoidal curve (four-parameter logistic model) using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), which provided τ50 estimates for every concentration used; τ50 is the time needed to reach a response halfway between the baseline and maximum of the cumulative food intake. To compare the dose–response curves over time between unmodified CCK9 and PEG-CCK9, the relationship between dose (X) and τ50 (Y) for both unmodified CCK9 and PEG-CCK9 was approximated using linear regression (Figure 3).

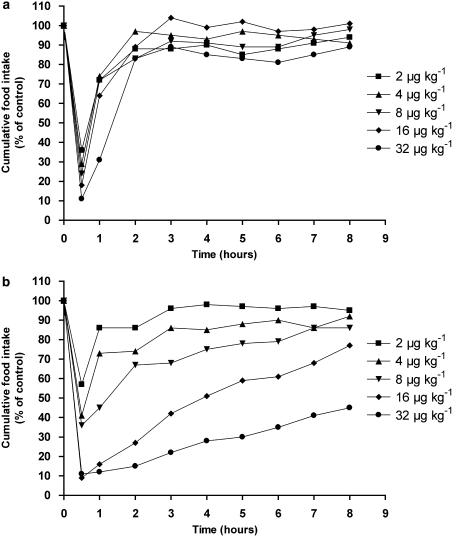

Figure 1.

Dose–response curves for the intraperitoneal injection of unmodified CCK9 (a) or PEGylated CCK9 (b) on food intake in rats over the dose range of 2–32 μg kg−1. The results are expressed as a percentage of the control food intake (100%). CCK, cholecystokinin; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

The effects of devazepide and 2-NAP on PEGylated CCK9-induced inhibition of food intake were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism (version 4, San Diego, CA, USA). Significant differences among treatment means were analysed by Tukey's multiple comparison test, with P-value<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Drugs, chemical reagents and other materials

The PEG-CCK9 conjugate was prepared as described by León-Tamariz et al. (2007). The PEG-CCK9 conjugates were quantified by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography, calibrated using pure CCK9 (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland). The amounts of PEG-CCK9 (μg kg−1) mentioned in the experiments indicate the amount of peptide present in the conjugate. The non-active linear methoxy-polyethylene glycol (mPEG-OH or CH3-(OCH2CH2)n-OH), used for control injections, was purchased from Nektar Therapeutics (Huntsville, AL, USA). The PEG-CCK9 conjugate consisted of 84.2% PEG and 15.8% CCK9 by weight. The amount of mPEG-OH given in the control injection was the same as the amount of PEG injected at the different doses of PEG-CCK9. Devazepide, kindly provided by Merck, Sharp and Dohme (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), was dissolved as a 1 mg ml−1 stock solution in a 7:3 (v/v) mixture of PEG 400 and glycerine. The stock solution was stored at 4°C and was diluted in 0.5 ml of saline before injection. 2-NAP was kindly provided by the James Black Foundation (London, UK) and was dissolved directly in saline.

Results

Experiment 1: dose–response effects of unmodified and PEGylated CCK9 on food intake in rats

The food intake reduction induced by a dose of 8 μg kg−1 was examined in both test periods for unmodified CCK9 and PEGylated CCK9 and no difference was observed between the results for the two test periods (P=0.3370 and P=0.2562). The data from the two test series could therefore be directly compared by statistical analysis.

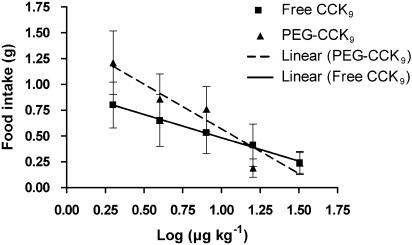

Food intake, measured 0.5 h after dark onset, was reduced compared to control food intake, by 67, 71, 79, 83 and 92% by injection of 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 μg kg−1, respectively for unmodified CCK9, whereas the same doses of PEG-CCK9 reduced food intake by 43, 59, 64, 91 and 89%, respectively (Figures 1a and b). Linear regression analysis revealed an inverse relationship between log dose and the 0.5 h food intake for both unmodified and PEGylated CCK9 (Figure 2). Both slopes were significantly different from zero, indicating a dose dependency of the initial intensity of anorexia for both drugs (CCK9; slope=−0.4526, P=0.0304; PEG-CCK9; slope=−0.8670, P=0.0002). There was no significant difference between the two slopes (P=0.1665).

Figure 2.

Dose dependency of the initial anorexic intensity in rats treated with unmodified CCK9 or PEGylated CCK9. The relationship between the log dose (X) and food intake measured at 0.5 h (Y) for unmodified CCK9 and PEG-CCK9 was approximated by linear regression. Both slopes were significantly different from zero (CCK9: slope=−0.4526, P=0.0304; PEG-CCK9: slope=−0.8670, P=0.0002). There was no significant difference between the two slopes (P=0.1665). CCK, cholecystokinin; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

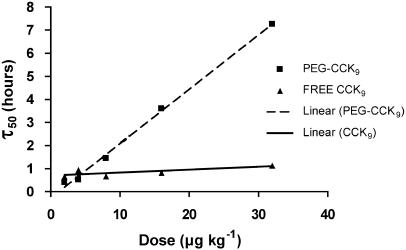

Figure 3 shows the relationship between dose (X) and τ50 (time for half-maximal food intake; Y) for both unmodified CCK9 and PEG-CCK9, approximated by linear regression. A significant linear relationship between the τ50 and the dose was seen for PEG-CCK9, but not for CCK9 (CCK9; P=0.1285, PEG-CCK9; slope=0.2357, P<0.0001, r2=0.9970). This shows that the duration of the anorectic effect of PEG-CCK9, but not that of CCK9, increased with dose.

Figure 3.

Dose response over time in rats treated with unmodified CCK9 or PEGylated CCK9. The relationship between dose (X) and τ50 (Y) for unmodified CCK9 and PEG-CCK9 was approximated by linear regression. The response curves as shown in Figures 1a and 1b were fitted with a sigmoidal curve (four-parameter logistic model), which provided τ50 estimates for every concentration used. τ50 is defined as the time for the half-maximal response. The slope of the line from the PEG-CCK9 results is significantly different from zero, indicating a clear correlation between dose and τ50, whereas that for CCK9 is not (CCK9: P=0.1285; PEG-CCK9: slope=0.2357, P<0.0001, r2=0.9970). CCK, cholecystokinin; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Experiment 2: effect of devazepide on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition

A statistically significant difference in food intake was observed between the different treatments used (ANOVA; P<0.0001 at 1 h, P<0.0001 at 6 h, P<0.0001 at 23 h). An i.p. injection of 100 μg kg−1 of devazepide stimulated cumulative food intake across the 23 h period, cumulative food intake at 1, 6 and 23 h being increased by 39, 19 and 18% respectively, compared to mPEG-OH-treated controls (Table 1). I.p. injection of 6 μg kg−1 PEGylated CCK9 significantly reduced cumulative food intake for 6 h, while simultaneous administration of devazepide and PEG-CCK9 restored cumulative food intake to control levels.

Table 1.

Effect of devazepide on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition

| Treatment |

Cumulative food intake (g) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 6 h | 23 h | |

| mPEG-OH (32 μg kg−1) | 2.8±0.2a | 12.5±0.3b | 27.1±0.7bc |

| Devazepide (100 μg kg−1) | 3.9±0.6a | 14.8±0.5a | 31.9±0.8a |

| PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) | 1.1±0.2b | 8.8±0.3c | 26.3±0.7c |

| Devazepide (100 μg kg−1) and PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) | 2.9±0.3a | 13.4±0.7ab | 29.8±0.8ab |

Abbreviations: CCK, cholecystokinin; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Values are expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n=8). The different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences within columns (P<0.05) (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Experiment 3: effect of 2-NAP on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition

Duration of the in vivo effect of 2-NAP

Table 2 shows that the antagonistic effect of 2-NAP on CCK9- and PEG-CCK9-induced anorexia decreased with increasing time between the injection of 2-NAP and the injection of CCK9 or PEG-CCK9. I.p. injection of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1), followed immediately by i.p. injection of CCK9 or PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1), was able to completely restore food intake to control levels, whereas the same dose of 2-NAP, injected 2 h or more before CCK9 or PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1), was not able to completely antagonize their anorectic effects. The food intake of the groups receiving the 2-NAP injection, 6 h before injection of CCK9 or PEG-CCK9, was similar to that of the groups receiving only the CCK9 or PEG-CCK9 injection.

Table 2.

Reduction over time of the antagonistic effect of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1) on CCK9- and PEG-CCK9-induced anorexia (6 μg kg−1) in rats

| Time before refeeding | Food intake 30 min after refeeding (g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 4 h | 2 h | 10 min | X=CCK9 | X=PEG-CCK9 |

| mPEG-OH | 5.3±0.2a | 5.0±0.3a | |||

| X | 1.2±0.4c | 2.4±0.2b | |||

| 2-NAP/X | 4.5±0.7ab | 5.2±0.5a | |||

| 2-NAP | X | 2.7±0.6bc | 3.2±0.3b | ||

| 2-NAP | X | 2.1±0.4c | 2.8±0.4b | ||

| 2-NAP | X | 1.6±0.4c | 2.0±0.2b | ||

Abbreviations: CCK, cholecystokinin; 2-NAP, 2-naphthalenesulphonyl 1-aspartyl-(2-phenethyl) amide; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Values are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. (n=8). The different letters indicate significant differences in food intake within columns (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Effect of 2-NAP on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake inhibition

The effect of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1) on PEG-CCK9-induced food intake inhibition is shown in Table 3. Statistical analysis of the data showed significant effects on the cumulative, 1 h and 6 h, but not the 23 h, food intake for the different treatments (P=0.0017 at 1 h; P=0.0001 at 6 h; P=0.5655 at 23 h). Repeated injections of 2-NAP alone (3 mg kg−1 every 2 h for 6 h) were not able to stimulate food intake, compared to mPEG-OH-treated controls. A single i.p. bolus injection of PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) induced a significant food intake reduction for at least 6 h and repeated injections of 2-NAP completely abolished the suppressant effect of PEG-CCK9.

Table 3.

Effect of 2-NAP on PEGylated CCK9-induced anorexia in rats

|

Cumulative food intake (g) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 6 h | 23 h | |

| mPEG-OH (32 μg kg−1) | 2.5±0.4a | 13.1±0.5a | 27.3±0.4a |

| 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1) | 2.2±0.3a | 13.5±0.7a | 26.9±0.5a |

| PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) | 1.2±0.1b | 10.4±0.3b | 26.4±0.6a |

| 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1) and PEG-CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) | 2.2±0.3a | 13.2±0.9a | 27.4±0.7a |

Abbreviations: CCK, cholecystokinin; 2-NAP, 2-naphthalenesulphonyl 1-aspartyl-(2-phenethyl) amide; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Values are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. (n=8). The different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences within columns (P<0.05) (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Discussion

Conjugation of PEG to peptides and proteins has become a popular approach to improve their therapeutic potential. With a minimal loss of biological activity, PEGylation results in an increase in the effective size of proteins, decreasing the kidney filtration rate, and protects the proteins from enzymatic degradation, thereby increasing their circulation time. It also renders proteins non-immunogenic and non-antigenic (Abuchowski et al., 1977b; Harris et al., 2001; Roberts et al., 2002; Harris and Chess, 2003; Veronese and Pasut, 2005). Previously, we successfully PEGylated CCK9 (molecular weight of the PEG fraction from 5 to 30 kDa) and demonstrated that an i.p. bolus injection of PEGylated CCK9 in rats resulted in a prolonged anorectic effect compared with unmodified CCK9, the 10 kDa PEG-CCK9 being the most active conjugate (León-Tamariz et al., 2007).

The present study showed that both the duration and initial intensity of the anorexia caused by PEGylated CCK9 displayed a clear dose–response effect (Figure 1b). In contrast, only the initial intensity of unmodified CCK9-induced anorexia showed a dose-related effect. To compare the dose–response curves over time of PEGylated CCK9 with unmodified CCK9, we used a four-parameter logistic model, which generated the quantitative parameter τ50, indicating the time at which the response was half-maximum. The τ50 showed that the anorectic effect of unmodified CCK9 was half-maximal within 1.15 h at every concentration used, whereas that of PEG-CCK9 was linearly dependent on the dose. The findings for free CCK9 are consistent with the earlier findings of Koulischer et al. (1982), who showed that CCK9 analogues are rapidly converted into their corresponding octapeptides, which are then degraded within 17 min in rat plasma. In general, PEGylation increases the circulation time in the body by protecting the active molecule from proteolytic enzymes and shielding immunoreactive sites (Harris et al., 2001; Harris and Chess, 2003). The fact that τ50 for PEGylated CCK9 showed a dose response whereas that for unmodified CCK9 did not suggests that PEG-CCK9 remains in the body longer than free CCK9. This confirms a previous report of León-Tamariz et al. (2007), who found that CCK9 incubated in fresh rat plasma at 37°C has a half-life between 2 and 3 min, whereas PEGylated CCK9 incubated under the same conditions is not degraded over a 24 h period. This higher resistance of PEGylated CCK9 to proteolysis suggests that the observed prolonged anorectic effect of the conjugate could be due to an increased circulation time. Further research is needed to substantiate this. The process of PEGylation can be accompanied by some loss of biological activity through steric hindrance (Veronese and Pasut, 2005) and this may explain the lower initial anorectic activity observed with PEG-CCK9 than with similar doses of free CCK9, although these differences were not statistically different.

Devazepide and 2-NAP, two selective CCK1 receptor antagonists with different abilities to penetrate the BBB, were used to examine whether PEG-CCK9 induced its anorectic effect by acting on central and/or peripheral CCK1 receptors. Devazepide can cross the BBB whereas 2-NAP cannot (Baldwin et al., 1994). In our experimental system, administration of devazepide alone resulted in a significant 23 h augmentation of food intake compared to controls. This observation is consistent with the hyperphagia originally reported in a variety of animal species under a number of different feeding schedules and sustains the hypothesis that endogenous CCK plays a role in the control of food intake through the activation of CCK1 receptors (Hewson et al., 1988; Ebenezer et al., 1990; Bado et al., 1991; Weatherford et al., 1993; Covasa and Forbes, 1994; Ebenezer and Baldwin, 1995). The present study also showed that coadministration of devazepide (100 μg kg−1) with the PEGylated CCK9 (6 μg kg−1) completely abolished the anorectic effect of PEG-CCK9 over the 23 h measurement period, showing that CCK1 receptors are involved in food intake reduction induced by PEGylated CCK9. The fact that devazepide was able to stimulate food intake and abolished the anorectic effect of PEG-CCK9 over a period of 23 h suggests that devazepide (100 μg kg−1) is at least active for 6 h, the active period of a dose of 6 μg kg−1 PEG-CCK9. Unpublished data (Dr Jiunn Lin, Merck Sharp and Dohme) reported in two studies (Reidelberger et al., 1991, 2003) give the half-life of devazepide as 3.5±1.8 or 4 h, although studies using [3H]devazepide have suggested that the half-life time may be longer than this (Reidelberger et al., 2003). It should be noted that the present study did not focus on the kinetics of binding of PEGylated CCK9 to the receptor and further research is needed to compare the binding kinetics of unmodified and PEGylated CCK9. Future competitive binding studies could provide useful information concerning the change of bioactivity by the process of PEGylation. As devazepide is known to block both central and peripheral CCK1 receptors (Pullen and Hodgson, 1987; Woltman et al., 1999), these results with devazepide could not discriminate between a peripheral or central mode of action of i.p.-injected PEG-CCK9. PEGylation of conjugates improves penetration into central nervous system (CNS) tissue (Wu and Pardridge, 1999; Ankeny et al., 2001; Calvo et al., 2001; MacKay et al., 2005) and it is possible that PEG-CCK9 can enter the brain, in contrast to free CCK9, which cannot (Passaro et al., 1982). To test this issue, further studies were performed using a specific CCK1 receptor antagonist 2-NAP, which cannot cross the BBB (Abuchowski et al., 1977a; Hull et al., 1993; Baldwin et al., 1994).

To investigate the effect of 2-NAP on the long-lasting anorectic effect of PEGylated CCK9, we first determined the reduction with time of the antagonistic effect of 2-NAP on CCK9- and PEGylated CCK9-induced anorexia in vivo and found that the antagonistic effect on unmodified CCK9- and on PEGylated CCK9-induced food intake reduction was significantly decreased within 2 h. Consequently, 2-NAP was injected every 2 h in the subsequent experiment. The observed reduction of the antagonistic effect of 2-NAP with time could probably be ascribed to the natural clearance rate of the peptide, although the ultimate reason for this decrease in antagonistic effect remains to be established as no published data are available on this point.

In our experimental system, it was observed that injections of 2-NAP alone (3 mg kg−1, every 2 h for 6 h) did not stimulate food intake. This observation is consistent with the report of Ebenezer and Baldwin (1995), promoting the role of endogenous CCK in satiety through central nervous system CCK1 receptors and questioning the hypothesis that endogenous peripheral CCK acts as a satiety signal. In contrast, Reidelberger etal. (2003) found that food intake in rats increases in response to systemic administration of A-70104, another CCK1 receptor antagonist that does not cross the BBB. On the other hand, Ebenezer and Parrot could not find a stimulating effect of A-70104 on food intake in pigs (Ebenezer and Parrot, 1993) and rats (Ebenezer, 2003). Reidelberger et al. (2003) suggested that the ineffectiveness of A-70104 in these studies of Ebenezer and Parrot could be ascribed to the small doses used. In the present study, we used a dose of 3 mg kg−1 of 2-NAP, which is reported to be sufficient to block the effects of exogenous peripheral CCK (Ebenezer and Baldwin, 1995), suggesting that this dose should also be sufficient to block the effects of the endogenous peripheral CCK. Using concentrations of 2-NAP up to 21 mg kg−1, identical observations were made (data not shown). However, the goal of our study was to unravel the pathway used by exogenous PEGylated CCK9 and not to determine whether endogenous CCK9 has a central or peripheral mode of action.

In the present studies, administration of 2-NAP (3 mg kg−1, every 2 h for 6 h) blocked the anorectic effect of PEG-CCK9, suggesting that the PEG-CCK9-induced anorexia is completely due to stimulation of peripheral CCK1 receptors. We cannot rule out the possibility that the PEGylated molecule is able to cross the BBB, but, if so, the present study suggests that it does not cause a significant anorectic effect by stimulation of central CCK1 receptors. Further research is needed to explore the possible movement of PEG-CCK9 across the BBB.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that PEGylated CCK9 shows a clear dose dependency of both the duration and initial intensity of anorexia, confirming the prolonged anorectic effect of PEGylated CCK9 compared with unmodified CCK9. Our results also show that the anorectic effect of PEGylated CCK9 is completely abolished by administration of devazepide, a CCK1 receptor antagonist that can cross the BBB, suggesting that the anorectic effect of PEGylated CCK9 is due to activation of CCK1 receptors. Repeated administration of 2-NAP, which does not cross the BBB, also completely inhibits the anorectic effect of PEG-CCK9, indicating that PEG–CCK9-induced anorexia is solely due to stimulation of peripheral CCK1 receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Onderzoeksraad van de K.U. Leuven, OT 04/32, and Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, FWO G. 0519.05.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CCK9

cholecystokinin9

- 2-NAP

2-naphthalenesulphonyl 1-aspartyl-(2-phenethyl) amide

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PEG-CCK9

PEGylated cholecystokinin9

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Abuchowski A, McCoy JR, Palczuk NC, van Es T, Davis FF. Effect of covalent attachment of polyethylene glycol on immunogenicity and circulating life of bovine liver catalase. J Biol Chem. 1977a;252:3582–3586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuchowski A, van Es T, Palczuk NC, Davis FF. Alteration of immunological properties of bovine serum albumin by covalent attachment of polyethylene glycol. J Biol Chem. 1977b;252:3578–3581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankeny DP, McTigue DM, Guan Z, Yan Q, Kinstler O, Stokes BT, et al. Pegylated brain-derived neurotrophic factor shows improved distribution into the spinal cord and stimulates locomotor activity and morphological changes after injury. Exp Neurol. 2001;170:85–100. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bado A, Durieux C, Moizo L, Roques BP, Lewin MJ. Cholecystokinin-A receptor mediation of food intake in cats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:693–697. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.4.R693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin BA, de la Riva C, Gerskowitch VP. Effect of a novel CCKA receptor antagonist (2-NAP) on the reduction in food intake produced by CCK in pigs. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin BA, Parrott RF, Ebenezer IS. Food for thought: a critique on the hypothesis that endogenous cholecystokinin acts as a physiological satiety factor. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55:477–507. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo P, Gouritin B, Chacun H, Desmaele D, D'Angelo J, Noel JP, et al. Long-circulating PEGylated polycyanoacrylate nanoparticles as new drug carrier for brain delivery. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1157–1166. doi: 10.1023/a:1010931127745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokelaere MM, Busselen P, Flo G, Daenens P, Decuypere E, Kuhn E, et al. Devazepide reverses the anorexic effect of simmondsin in the rat. J Endocrinol. 1995;147:473–477. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1470473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covasa M, Forbes JM. Effects of the CCK receptor antagonist MK-329 on food intake in broiler chickens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:479–486. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cuyper M, Lievens S, Flo G, Cokelaere M, Peleman C, Martins F, et al. Receptor-mediated biological responses are prolonged using hydrophobized ligands. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;20:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer IS. The effects of a peripherally acting cholecystokinin1 receptor antagonist on food intake in rats: implications for the cholecystokinin–satiety hypothesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;461:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02916-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer IS, Baldwin BA. 2-Naphthalenesulphonyl-L-aspartyl-2-(phenethyl) amide (2-NAP) and food intake in rats: evidence that endogenous peripheral CCK does not play a major role as a satiety factor. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2371–2374. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer IS, de la Riva C, Baldwin BA. Effects of the CCK receptor antagonist MK-329 on food intake in pigs. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer IS, Parrott RF. A70104 and food intake in pigs: implication for the CCK ‘satiety' hypothesis. NeuroReport. 1993;4:495–498. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199305000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flo G, Van Boven M, Vermaut S, Daenens P, Decuypere E, Cokelaere M. The vagus nerve is involved in the anorexigenic effect of simmondsin in the rat. Appetite. 2000;34:147–151. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flo G, Vermaut S, Darras VM, Van Boven M, Decuypere E, Kuhn ER, et al. Effects of simmondsin on food intake, growth, and metabolic variables in lean (+/?) and obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Br J Nutr. 1999;81:159–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flo G, Vermaut S, Van Boven M, Daenens P, Buyse J, Decuypere E, et al. Comparison of the effects of simmondsin and cholecystokinin on metabolism, brown adipose tissue and the pancreas in food-restricted rats. Horm Metab Res. 1998;30:504–508. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:214–221. doi: 10.1038/nrd1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JM, Martin NE, Modi M. Pegylation: a novel process for modifying pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:539–551. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewson G, Leighton GE, Hill RG, Hughes J. The cholecystokinin receptor antagonist L364,718 increases food intake in the rat by attenuation of the action of endogenous cholecystokinin. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;93:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull RA, Shankley NP, Harper EA, Gerkowitch VP, Black JW. 2-Naphthalenesulphonyl L-aspartyl-(2-phenethyl)amide (2-NAP) – a selective cholecystokinin CCKA-receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108:734–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy AC, Oldberg E. Contraction and evacuation of gall-bladder caused by a highly purified ‘secretin' preparation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1927;25:113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Koulischer D, Moroder L, Deschodt-Lanckman M. Degradation of cholecystokinin octapeptide, related fragments and analogs by human and rat plasma in vitro. Regul Pept. 1982;4:127–139. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(82)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León-Tamariz F, Verbaeys I, VanBoven M, DeCuyper M, Buyse J, Clynen E, et al. PEGylation of cholecystokinin prolongs its anorectic effect in rats. Peptides. 2007;28:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievens S, Flo G, Decuypere E, Van Boven M, Cokelaere M. Simmondsin: effects on meal patterns and choice behavior in rats. Physiol Behav. 2003;78:669–677. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay JA, Deen DF, Szoka FC. Distribution in brain of liposomes after convection enhanced delivery; modulation by particle charge, particle diameter, and presence of steric coating. Brain Res. 2005;1035:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passaro EJr, Debas H, Oldendorf W, Yamada T. Rapid appearance of intraventricularly administered neuropeptides in the peripheral circulation. Brain Res. 1982;241:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen RG, Hodgson OJ. Penetration of diazepam and the non-peptide CCK antagonist, L-364,718, into rat brain. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1987;39:863–864. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1987.tb05138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidelberger RD, Castellanos DA, Hulce M. Effects of peripheral CCK receptor blockade on food intake in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R429–R437. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00176.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidelberger RD, Varga G, Solomon TE. Effects of selective cholecystokinin antagonists L364,718 and L365,260 on food intake in rats. Peptide. 1991;12:1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90197-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MJ, Bentley MD, Harris JM. Chemistry for peptide and protein PEGylation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:459–476. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GP, Gibbs J. Role of CCK in satiety and appetite control. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1992;15:476A. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199201001-00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GP, Gibbs J. Satiating effect of cholecystokinin. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;713:236–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese FM, Pasut G. PEGylation, successful approach to drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherford SC, Chiruzzo FY, Laughton WB. Satiety induced by endogenous and exogenous cholecystokinin is mediated by CCK-A receptors in mice. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:574–578. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherford SC, Laughton WB, Salabarria J, Danho W, Tilley JW, Netterville LA, et al. CCK satiety is differentially mediated by high- and low-affinity CCK receptors in mice and rats. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:244–249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.2.R244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller A, Smith GP, Gibbs J. Endogenous cholecystokinin reduces feeding in young rats. Science. 1990;247:1589–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.2321020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltman TA, Hulce M, Reidelberger RD. Relative blood–brain barrier permeabilities of the cholecystokinin receptor antagonists devazepide and A-65186 in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1999;51:917–920. doi: 10.1211/0022357991773348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Pardridge WM. Neuroprotection with noninvasive neurotrophin delivery to the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:254–259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]