Abstract

Cobalt is a transition metal which can substitute for iron in the oxygen-sensitive protein and mimic hypoxia. Cobalt was known to be associated with the development of lung disease. In this study, when lung cells were exposed to hypoxia induced by CoCl2 at a sub-lethal concentration (100 μM), their thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) expression was greatly reduced. Under this condition, SP-B promoter activity was down regulated, but SP-C promoter remained active. Therefore, we hypothesized that other factor(s) besides TTF-1 might contribute to the modulation of SP-C promoter in hypoxic lung cells. Pleomorphic adenoma gene like-2 (PLAGL2), a previously identified TTF-1-independent activator of the SP-C promoter, was not down regulated, nor increased, within those cells. Its cellular location was redistributed from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and quantitative RT-PCR analyses demonstrated that nuclear PLAGL2 occupied and transactivated the endogenous SP-C promoter in lung cells. Thereby, through relocating and accumulating of PLAGL2 inside the nucleus, PLAGL2 interacted with its target genes for various cellular functions. These results further suggest that PLAGL2 is an oxidative stress responding regulator in lung cells.

Keywords: PLAGL2, TTF-1, Translocation, SP-C, SP-B, Cobalt Chloride, Hypoxia

INTRODUCTION

Surfactant proteins B (SP-B) and C (SP-C) are two small hydrophobic proteins, essential for maintaining surface tension in pulmonary alveoli. The regulation of SP-B and SP-C genes is attributed to the binding of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), a homeodomain transcription factor, to their promoters [1; 2]. For SP-C, its cell specificity is controlled within the proximal region of the SP-C promoter, which contains two essential TTF-1 binding sites (T4 and T5) and a previously identified cis-element for Pleomorphic adenoma gene like-2 (PLAGL2) binding [3]. Thus, besides TTF-1, PLAGL2 was suspected to be another modulator of the SP-C promoter. The cis-element for PLAGL2 binding on the SP-C promoter is functional [3]. In addition, transfection studies in lung and non-lung cells further indicated that PLAGL2 activation of the SP-C promoter was independent of TTF-1 and other lung cell-specific factor(s)[3].

PLAGL2 was first identified by homology to PLAG1, a zinc finger protein [4]. PLAG1, PLAGL2, and another PLAG-like protein, PLAGL1, form a PLAG gene family. Both PLAGL2 and PLAG1 transform NIH3T3 cells [5]. However, they induce apoptosis rather than proliferation in other types of cell [6], suggesting a versatile role of PLAGL2 in cell cycle regulation. In addition, PLAGL2 could be induced by hypoxia or “hypoxia-mimics”- namely cobalt chloride (CoCl2) in some cells [7].

Cobalt, one of the transition metals, can substitute for the iron atom in the heme protein which binds oxygen. The mechanism by which Co2+ activates hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and mimics hypoxia in cells may be by substitution for Fe2+ in the regulatory dioxygenase to inactivate the enzyme [8]. In lung cells, the underlying mechanism of cobalt-induced pneumotoxic effect was suggested by the down-regulation of the negative regulators of HIF-1 [9]. Though Cobalt has been known to associate with the development of lung interstitial fibrosis disease, there is little known about its influence on surfactant protein genes expression. In this study, we showed that CoCl2-induced oxidative stress down-regulated SP-B promoter activity by repressing TTF-1 expression. On the other hand, the SP-C promoter stayed active despite the reduction of TTF-1, raising a possibility of other factor(s) contribution to the promoter activity. Given that PLAGL2, a previously identified SP-C promoter activator, was not down-regulated but relocated and accumulated in the nucleus, a role of PLAGL2 in preventing the loss of SP-C-related lung function by hypoxia was suggested.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Cell culture

MLE12 cells (murine type II cells, ATCC CRL-2110) and H441 cells (human lung adenocarcinoma cells, ATCC HTB-174) were maintained as previously described [3; 10]. For immunofluorescent study, cells were seeded overnight before being treated with 100 μM CoCl2 for 48 hours. Both treated and untreated cells were then fixed in situ by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized by 0.1% saponin, and probed with the monoclonal antibody to PLAGL2 (mAb85C47-1). Rabbit anti-mouse-FITC antibody was used as the secondary antibody for the detection and was observed under a fluorescent microscope.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP)

ChIP assay was performed using a protocol exactly as previously described [10]. The SP-B or SP-C promoter fragments were generated by PCR using the following primers: SP-B promoter, 5'-primer GTTTGACGGTGAACAAAGTCAGGCT and 3'-primer GACCTCAGTGTTTGCCTGTGTCT for mouse, 5'-primer CCAGGAACATGGGAGTCTGG and 3'-primer TAGGAGTGGCAGCGACCTC for human; SP-C promoter, 5'-primer GGCAGACATGCAGAAAGACA and 3'-primer TCCTTGGCTTTGTAGCTTGTT for mouse, 5'-primer CCCGAGGGCAAGTTTGCTC and 3'-primer CAAGCCCTTGGCTTTGAAGC for human. The program for PCR reactions was: 95°C, 1 min; 59°C, 1 min; and 72°C, 1 min.

Western blot analysis

Cellular proteins obtained from cell lysates used in the luciferase assay were fractionated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to a PVDF membrane for Western blot analysis. The membrane was probed with antibodies to PLAGL2 (mAb85C47-1, 1:3000), anti-TTF-1 antibody (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA; 1:3000), or anti-Actin monoclonal antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA; 1:10000) followed by goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)(Pierce, Rockford, IL; 1:50,000) and then developed with HRP Supersignal substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

In vitro transfection and plasmids

Transfection assays were conducted as described in the previous manuscripts [10; 11]. Each data point presented in the transfection studies was collected from at least three individual experiments with triplicates (N ≥ 9) or otherwise as stated. The data were then summarized and plotted as an average mean ± SE (standard errors). The significance of activity changes was calculated by a 2-tailed t-test analysis. A probability value p<0.05 was accepted as significantly different from the control.

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from MLE12 cells. Cultured MLE12 cells prepared for RT-PCR gene analysis were harvested at 80 – 90% confluence. MLE12 cells, treated with various reagents or transfected with expression plasmid (pCIN-Flag or Flag-PLAGL2) in 24-well plate (∼ 8 × 105/well) were harvested for RNA preparation using RNeasy Kit (Qiagene, Valencia, CA). Total RNAs isolated from 3 wells were combined together and then subjected to cDNA synthesis [3].

All of the primers used in the PCR analysis were designed to amplify across exon and intron junctions. For quantitative measurement of GAPDH, SP-C, SP-B, TTF-1, and PLAGL2 transcripts, real-time PCR analysis was employed by incorporating Sybr-green in the amplification reaction and cycled on iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primers used for the real-time and RT-PCR analyses were listed in the previous manuscript. The gene transcripts measurement and statistic analysis were performed as previously described [3].

RESULTS

Gene expression in CoCl2 treated lung cells

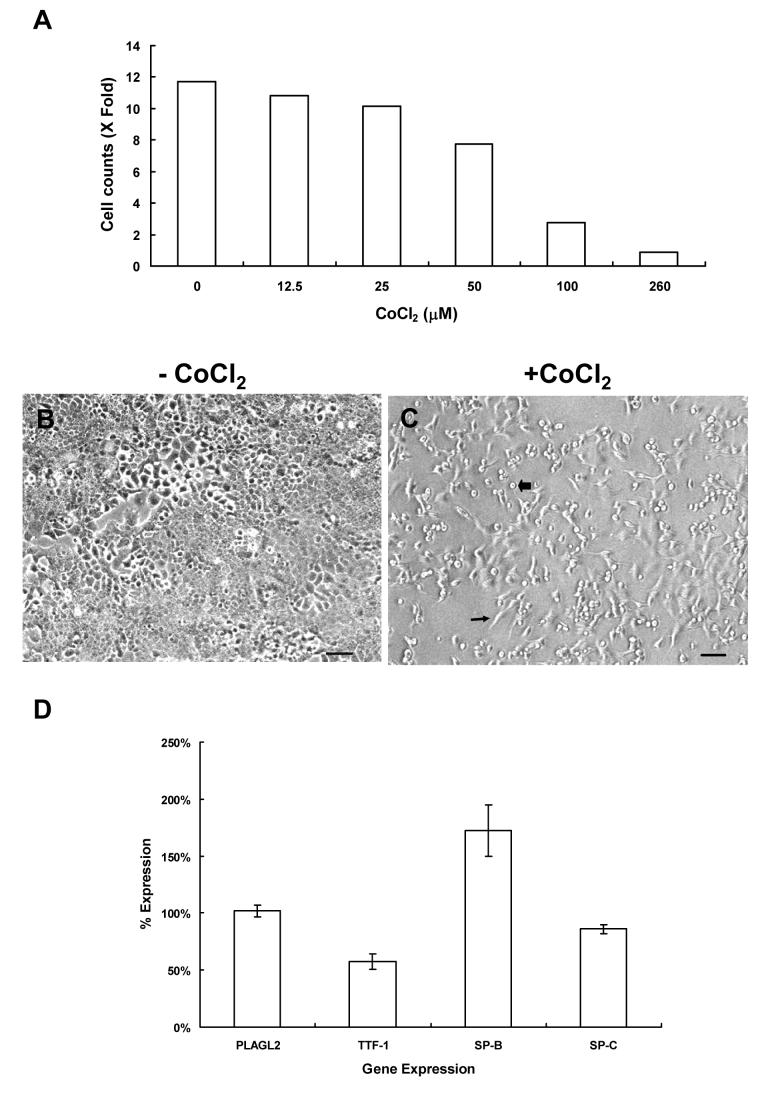

Exposure to Co2+ was known to cause lung disease; however, its concomitant effect on surfactant protein gene expression has never been examined. Here, we evaluated the impact of chemical-induced hypoxia on SP-B and SP-C expression. MLE12 cells were seeded and treated with CoCl2 at a concentration that was not lethal to cells, but with delayed normal cell growth. The concentration, which was applied to cells, was determined by the cell growth curve (Figure 1A). There was a 2.75-fold increase in the cell counts of 100 μM CoCl2 treated cells versus an 11.7-fold increase in the control sample when compared to the originally seeded cells (Figure 1A). The chosen concentration for this study was 100 μM and it was similar to that in other report [7]. With this treatment, besides a slower cell growth rate, cell morphology was also changed from spread and adherent in normal control cells (Figure 1B) to spindle or spherical in treated cells (Figure 1C). Those cells were not dead according to propidium iodide or trypan blue staining. At a higher concentration of CoCl2 (>200 μM), the decrease of cell numbers indicated the toxicity effects on cell viability.

Figure 1.

MLE12 cells growth rate and TTF-1 expression were suppressed by CoCl2-induced hypoxia. (A) The cell number changes of MLE12 cells were graphed against various concentrations of CoCl2 in medium. Cell counts in duplicated wells from two individual experiments were averaged and plotted. Fold of cell number increase was compared to the cell number in the overnight culture before treated with CoCl2. (B and C) The growth and cell morphology of MLE12 cells were changed by CoCl2 treatment. Equal amounts of cells (2X104/well) were seeded overnight before treated with CoCl2. After 48 hours of treatment, cells without (B) or with (C) the CoCl2 treatment were observed under microscope with phase contrast. Arrow and blockarrow in C denoted cells with morphological changes to spindle or spherical and lose adhering. The size bar indicated 100 μm. Magnification 10X. (D) Gene expression pattern in MLE12 cells treated with 100 μM CoCl2 for 48 hours. Total RNA from harvested cells was isolated and analyzed for the expression of indicated genes. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed to measure and compare the level of individual gene transcript in CoCl2 treated and control samples. The expression level in the control was set at 100%. Data collected for statistical analysis was as described (N≥12).

To examine gene expression in those lung cells under the hypoxia condition, total RNAs were prepared from treated and untreated MLE12 cells and then subjected to quantitative PCR analysis. MLE12 cells express SP-B, SP-C, and TTF-1 type II cell-specific markers. As shown in Figure 1D, quantitative RT-PCR showed that TTF-1 expression was sensitive to CoCl2 treatment (58±7 % of the control), but PLAGL2 expression was resistant to the treatment and remained unchanged (108±5 %) (Figure 1D). Thus, PLAGL2 and TTF-1 clearly have differential responses to CoCl2 induced hypoxia. Regarding SP-B and SP-C expression, there were no significant decreases of their transcripts in treated cells (172±23% and 83±4 %, respectively). Certainly, the amounts of SP-B and SP-C messages were not parallel to TTF-1 reduction in CoCl2 treated cells.

The SP-C promoter remains active in cells under the hypoxia condition

The mechanism by which SP-B and SP-C transcripts were remained in CoCl2 treated MLE12 cells could be due to continuously activated promoter. To test this possibility, luciferase reporter gene driven by the promoters were employed for examination. With higher PLAGL2 protein level than that in MLE12 cells [3], H441 cells were utilized for the investigation. Similar to the response of MLE12 cells to CoCl2, TTF-1 expression was also reduced in H441 cells; but PLAGL2 expression remained (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, when cells were treated with 100 μM CoCl2, the SP-B promoter activity was reduced (Figure 2B, closed bar, 61±3 %) correspondingly to the level of TTF-1 (Figure 2A). However, the SP-C promoter stayed active (open bar, 85±5 %)(N=12) in those cells. This result indicated that in oxidative stress cells, SP-C promoter activity was not as tightly linked to the level of TTF-1 as the SP-B promoter. Thus, the continuous activation of the promoter preserved SP-C expression in those cells. Evidently, the mechanism by which the SP-B transcript steady-state level maintained in those hypoxic cells was not due to improved transcription activity. It could be by the increase of mRNA stability [12]. Nonetheless, the difference of promoter activities between the SP-C versus the SP-B promoter under this condition was significant (p<0.01, N=12).

Figure 2.

SP-C promoter activity remained in CoCl2 treated H441 cells. (A). PLAGL2 expression was not changed in CoCl treated H441 cells. A total of 4X104 cells/well in 24-well plate were seeded 48 hours before being treated with various amounts of CoCl2 in culture medium. Cells were harvested after 48 hours treatment, lysed, western blotted, and probed with mAb85C47-1, anti-TTF-1, and anti-actin antibodies sequentially. (B). The SP-C promoter remained active in 100 μM CoCl2 treated H441 cells. Cells as described in panel A were transfected with pGL3-hSP-BP (closed bar, 50 ng/well) or pGL3-hSP-CP (open bar, 400 ng/well) promoter with various concentrations of CoCl2 as labeled. Luciferase activities in cells were measured after 48 hours of transfection and statistically analyzed. Reporter gene activities in control without CoCl2 treatment were set to 100%. The difference of luciferase activities between SP-B and SP-C promoters in 100 μM CoCl2 treated cells was significant (**: p<0.01, N=12)

PLAGL2 translocation to the nucleus of CoCl2 treated cells

PLAGL2 was induced in cells under the hypoxia stress [7], however, our data showed that PLAGL2 expression remained constant in hypoxic lung cells (Figure 1 and 2A). We suspected that other mechanism, such as relocation of its cellular distribution, might be involved in the regulation of PLAGL2 activity in those cells. Exponentially growing H441 cells, with or without CoCl2 treatment, were fixed and probed with mAb85C47-1. In normaxia cells, PLAGL2 was diffusely distributed within both cytosolic and nuclear compartments (Figure 3A and B). In some cells, it was observed to concentrate at the perinuclear region (Figure 3B, block arrow). A recent report also showed that PLAGL2 was in both cytosolic and nuclear fractions of leucocytes [13]. Interestingly, upon exposure to CoCl2, the signal of PLAGL2 became more intense in the nuclei, indicating the translocation of PLAGL2 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

CoCl2 induced PLAGL2 translocation into the nuclei of H441 cells. H441 cells without (A and B) or with (C and D) CoCl2 (100 μM) treatment were fixed and probed with mAb85C47-1 (B and D). PLAGL2 was distributed in the cytoplasm and the nucleus compartments (B, arrows) or around the perinuclear region (B, blockarrow) of H441 cells. After adding CoCl2 for 48 hours, PLAGL2 signal was observed more intense in the nuclei (D, arrows). The size bar represented 100 μm. Magnification (20X).

Association of PLAGL2 to the SP-C promoter complex in lung cells

Since PLAGL2 was a modulator of the SP-C promoter [3], we expected that nuclear PLAGL2 should bind to the promoter in chromatin and improve its transcription. To further confirm the interactions between PLAGL2 and the SP-C promoter in vivo, the direct contact in cells was examined by ChIP assay. H441 cells were fixed in situ by formaldehyde and their chromatin complexes were prepared for the analysis. The fixed chromatin was immunoprecipitated with various antibodies and the associated antibody-antigen complexes were subsequently analyzed by PCR with specific primers to the SPB and SP-C promoters. As shown in Figure 4A (Lanes 1 and 2), chromatins precipitated by mAb85C47-1 and TTF-1 (positive control) antibodies contained the SPC promoter. The SP-B promoter was only detected in the TTF-1 associated chromatin complex but not in the PLAGL2 associated fraction. Neither the SP-C nor the SP-B promoter was detected in the negative control using mouse IgG (mIgG) antibody (Lane 3). Thus, like TTF-1, PLAGL2 in the nuclei was also associated with the SP-C promoter.

Figure 4.

PLAGL2 is associated with the SP-C promoter in H441 and transfected MLE12 cells. H441 (A) or Flag-PLAGL2 transfected MLE12 cells (B) were fixed in situ for the ChIP analysis. The harvested chromatin were immunoprecipitated with various antibodies as indicated above the panel. PCR was used to detect the SP-C and SP-B promoters within the precipitated chromatin associated with those antigen-antibody complexes. PCR amplified DNA fragments were visualized in a 2% agarose gel. The arrow points to the amplified SP-C or SP-B promoter DNA fragment in (B). The association of PLAGL2 to the SP-C promoter increases endogenous SP-C expression in transfected MLE12 cells (C). MLE12 cells transfected with 400 ng of pCIN-Flag (open bar) or Flag-PLAGL2 (closed bar) were incubated for 48 hours, harvested, and then subjected for gene expression evaluation by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. A t-test (N=5) was performed by comparing the expression of SP-B or SP-C genes in PLAGL2 transfected cells and pCIN-Flag vector transfected cells. The value for the control cells was set to 100%. (**: p<0.01).

PLAGL2 associated promoter complex has improved SP-C expression

Despite TTF-1 and PLAGL2 occupancy on the SP-C promoter, for an unknown reason, there was no measurable SP-C transcript in H441 cells (see Discussion). Thus, the change of endogenous SP-C expression cannot be determined in this cell. Since MLE12 cells have SP-C and low PLAGL2 expression ([3], and Figure 1), they were suitable for the examination. As shown in Figure 4B, the SP-C promoter fragment was detected in anti-Flag and anti-PLAGL2 antibodies (monoclonal and polyclonal) precipitated chromatin complexes (Figure 4B, Lanes 3, 4, and 7) isolated from PLAGL2 over expressed MLE12 cells. The same size of promoter amplicon was also detected in anti-TTF-1 and anti-RNA polymerase II antibodies precipitated complexes (Lanes 2 and 5, positive controls). Neither mIgG nor rabbit anti-mIgG antibody (negative controls) could immunoprecipitate the SP-C or SP-B promoter (Lanes 1 and 6). Thus, the ectopically expressed PLAGL2 could associate with the SP-C promoter in the chromatin of MLE12 cells. The presence of SP-C promoter in PLAGL2 containing complex was specific since the SP-B promoter was not present in the same complex (Figure 4B lower panel). Both anti-TTF-1 and anti-RNA-polymerase II positive control antibodies brought down the SP-C and the SP-B promoter complexes (Figure 4B, Lanes 2 and 5).

To further examine the function of PLAGL2 occupancy on the promoter, the level of endogenous SP-C message was measured. Total RNAs collected from Flag-PLAGL2 or pCIN-Flag (empty vector) transfected MLE12 cells were subjected to quantitative PCR analysis of SP-B and SP-C transcripts by using real-time PCR. As shown in Figure 4C, a 40 % increase of SP-C message was detected in Flag-PLAGL2 transfected cells (N=5, p<0.01) whereas the amount of SP-B transcripts remained unchanged (Figure 4C). Thus, together with the ChIP and real-time quantitative PCR results (Figure 4B), our data supported a role of PLAGL2 in mediating SP-C promoter activity in lung cells.

DISCUSSION

Though PLAGL2 is likely responsible for the activation of various genes leading to apoptosis or tumorigenesis [6; 14], its induction in CoCl2 treated cells further suggests a role of PLAGL2 in cellular response to stress. Previously, we demonstrated that PLAGL2 transactivated the SP-C promoter [3]; in this study, the association of PLAGL2 with the SP-C promoter in chromatin of H441 cells was further determined by its occupancy in vivo. Our ChIP results indicated that both PLAGL2 and TTF-1 were associated with the SP-C promoter in H441 and MLE12 cells and the presence of PLAGL2 functionally advanced the promoter activity (Figures 4). It is worth mention that the occupancy and activation of the promoter was detected on the endogenous gene. Thus, it confirms the physical contact of PLAGL2 with the SP-C promoter in chromatin and its function in activating the promoter. Since the SP-B promoter is absent in the PLAGL2 complex, the interaction between PLAGL2 and the SP-C promoter in chromatin appears to be specific.

The underlying mechanism by which no SP-C transcripts were detected in H441 cells despite TTF-1 or PLAGL2 binding to the SP-C promoter could be the epigenetic regulation of the SP-C promoter. With methylated histone H3 and/or the methylation of CpG island sequence on the promoter, the gene expression could be silenced. That possibility requires further investigation.

In the previous study, we showed that the expression of SP-B correlated well with the amounts of TTF-1 and its associated protein TAP26 in cells [15], but only up to a certain level of SP-C promoter activity could be enhanced by the complex in MLE12 cells [10]. Since both SP-B and SP-C expression are TTF-1-dependent and their transcripts have relatively similar half lives [16], a stronger transcription complex may be required for SP-C expression in the lung. Our ChIP and quantitative RT-PCR studies suggests that PLAGL2 association with the SP-C promoter in chromatin could further up regulate its activity in vivo (Figures 4).

TTF-1 expression is impaired in lung epithelial cells during the acute lung injury [17] or in cells under an oxidative stress condition (Figures 1 and 2). Thereby, the impact of reduced TTF-1 on SP-B and SP-C expression is anticipated. However, a recent report showed that a low dose of bleomycin administration resulted in a decrease of SP-B, but not SP-C expression [18]. That result supports the original hypothesis that a TTF-1-independent regulation may be involved in the control of SP-C expression during lung injury or within cells under the oxidative stress. Given that lung cells respond to hypoxia by translocating PLAGL2 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus (Figure 3), the relocation could then provide a mechanism to raise PLAGL2 concentration within the nucleus, subsequently, to activate its down-stream target genes (Figure 4B). Besides the known SP-C promoter in lung cells as a target of PLAGL2, others may include those genes for the cell survival, cell cycle, or cellular signaling of which are interesting and worthy for further exploration.

PLAGL2 may offer a protective role in preventing lung cells from hypoxia damage since MLE12 cells with PLAGL2 over expression are more tolerant to CoCl2-induced hypoxia than parental cells (unpublished data). In addition, less cell growth and morphological impact on H441 cells (Figure 3) also correlates well with its higher level of PLAGL2 expression than in MLE12 cells. Because SP-C, like SP-B, also plays a protective role in lung injury and in maintaining normal lung function [19], the preservation of SP-B and SP-C homeostasis could be an important response of lung cells to prevent them from an extensive damage by hypoxia. The result of PLAGL2 relocation to the nucleus, conceptually, provides a defensive mechanism to avoid SP-C expression loss by means of sustaining its promoter activity in hypoxic lung cells.

More interestingly, PLAGL2 also modulates the promoter activation of NCF2 gene [13], which encodes p67phox, a cytosolic protein involved in the NADPH oxidase electron transfer from NADPH to molecular oxygen. Taken together with our results that PLAGL2 responds to hypoxia and could prevent lung cells from hypoxia-induced functional and cytotoxic damages, it further raises an inevitable role of PLAGL2 in mediating the cellular response to oxidative stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NHLBI grant R01HL63525 (YSY), and funding from the Will Rogers Institute and the James M. Collins Center for Biomedical Research (JCW).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kelly SE, Bachurski CJ, Burhans MS, Glasser SW. Transcription of the lung-specific surfactant protein C gene is mediated by thyroid transcription factor 1. J Biol.Chem. 1996;271:6881–6888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohinski RJ, Di Lauro R, Whitsett JA. The lung-specific surfactant protein B gene promoter is a target for thyroid transcription factor 1 and hepatocyte nuclear factor 3, indicating common factors for organ-specific gene expression along the foregut axis. Mol.Cell Biol. 1994;14:5671–5681. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang MC, Weissler JC, Terada LS, Deng F, Yang YS. Pleiomorphic Adenoma Gene-Like-2, a Zinc Finger Protein, Transactivates the Surfactant Protein-C Promoter. Am.J.Respir.Cell Mol.Biol. 2005;32:35–43. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0422OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kas K, Voz ML, Hensen K, Meyen E, Van de Ven WJ. Transcriptional activation capacity of the novel PLAG family of zinc finger proteins. J.Biol Chem. 1998;273:23026–23032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hensen K, Van Valckenborgh IC, Kas K, Van de Ven WJ, Voz ML. The tumorigenic diversity of the three PLAG family members is associated with different DNA binding capacities. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1510–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizutani A, Furukawa T, Adachi Y, Ikehara S, Taketani S. A zinc-finger protein, PLAGL2, induces the expression of a proapoptotic protein Nip3, leading to cellular apoptosis. J.Biol.Chem. 2002;277:15851–15858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa T, Adachi Y, Fujisawa J, Kambe T, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Sasaki R, Kuwahara J, Ikehara S, Tokunaga R, Taketani S. Involvement of PLAGL2 in activation of iron deficient- and hypoxia-induced gene expression in mouse cell lines. Oncogene. 2001;20:4718–4727. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maxwell P, Salnikow K. HIF-1: an oxygen and metal responsive transcription factor. Cancer Biol.Ther. 2004;3:29–35. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.1.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ke Q, Kluz T, Costa M. Down-regulation of the expression of the FIH-1 and ARD-1 genes at the transcriptional level by nickel and cobalt in the human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell line. Int.J Environ.Res.Public Health. 2005;2:10–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2005010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang MC, Guo Y, Liu CC, Weissler JC, Yang YS. The TTF-1/TAP26 complex differentially modulates surfactant protein-B (SP-B) and -C (SP-C) promoters in lung cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;344:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang YS, Yang MC, Wang B, Weissler JC. BR22, a novel protein, interacts with thyroid transcription factor-1 and activates the human surfactant protein B promoter. Am.J.Respir.Cell Mol.Biol. 2001;24:30–37. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.1.4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George TN, Miakotina OL, Goss KL, Snyder JM. Mechanism of all trans-retinoic acid and glucocorticoid regulation of surfactant protein mRNA. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L560–L566. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammons MC, Siemsen DW, Nelson-Overton LK, Quinn MT, Gauss KA. Binding of Pleomorphic Adenoma Gene-like 2 to the Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-{alpha}-responsive Region of the NCF2 Promoter Regulates p67phox Expression and NADPH Oxidase Activity. J.Biol.Chem. 2007;282:17941–17952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landrette SF, Kuo YH, Hensen K, van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani Barjesteh, Perrat PN, Van d., V, Delwel R, Castilla LH. Plag1 and Plagl2 are oncogenes that induce acute myeloid leukemia in cooperation with CbfbMYH11. Blood. 2005;105:2900–2907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang MC, Wang B, Weissler JC, Margraf LR, Yang YS. BR22, a 26 kDa thyroid transcription factor-1 associated protein (TAP26), is expressed in human lung cells. Eur.Respir.J. 2003;22:28–34. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00117702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatesh VC, Iannuzzi DM, Ertsey R, Ballard PL. Differential glucocorticoid regulation of the pulmonary hydrophobic surfactant proteins SP-B and SP-C. Am J Respir.Cell Mol.Biol. 1993;8:222–228. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stahlman MT, Gray ME, Whitsett JA. Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1(TTF-1) in fetal and neonatal human lung. J Histochem.Cytochem. 1996;44:673–678. doi: 10.1177/44.7.8675988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawson WE, Polosukhin VV, Stathopoulos GT, Zoia O, Han W, Lane KB, Li B, Donnelly EF, Holburn GE, Lewis KG, Collins RD, Hull WM, Glasser SW, Whitsett JA, Blackwell TS. Increased and Prolonged Pulmonary Fibrosis in Surfactant Protein C-Deficient Mice Following Intratracheal Bleomycin. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1267–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61214-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitsett JA. Genetic disorders of surfactant homeostasis. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 2006;7:S240–S242. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2006.04.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]