Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is the causative agent of AIDS (10, 38, 105, 114). It is characterized by extensive and dynamic genetic diversity, generating variants falling into distinct molecular subtypes as well as recombinant forms; these forms display an uneven global distribution (55). This diversity has implications for our understanding of viral transmission, pathogenesis, and diagnosis and profoundly influences strategies for vaccine development.

Here we review selected aspects of the genetic diversity of HIV-1, with particular emphasis on its pathogenetic and therapeutic implications.

HIV-1 GENETIC SUBTYPES

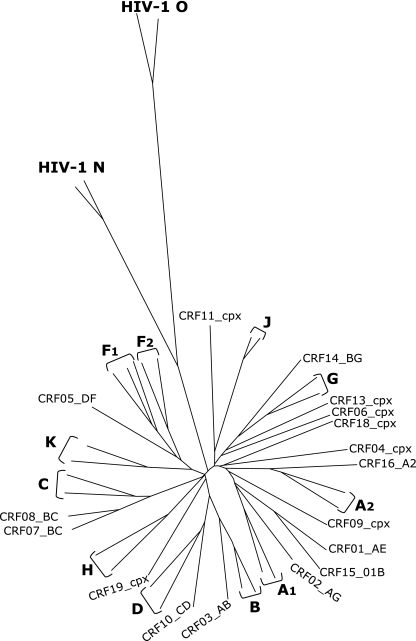

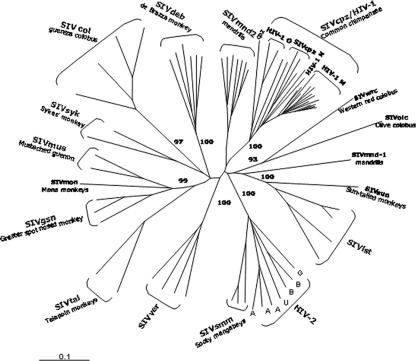

HIV-1 is characterized by extensive genetic heterogeneity driven by several factors, such as the lack of proofreading ability of the reverse transcriptase (RT) (96, 108), the rapid turnover of HIV-1 in vivo (56), host selective immune pressures (84), and recombination events during replication (122). Due to this variability, HIV-1 variants are classified into three major phylogenetic groups: group M (main), group O (outlier), and group N (non-M/non-O) (6, 52, 116). Group M, which is responsible for the majority of infections in the worldwide HIV-1 epidemic, can be further subdivided into 10 recognized phylogenetic subtypes, or clades (A to K), which are approximately equidistant from one another (Fig. 1). Within group M, the average intersubtype genetic variability is 15% for the gag gene and 25% for the env gene (58, 64, 68, 70, 92, 109).

FIG. 1.

Evolutionary relationships among nonrecombinant HIV-1 strains. The phylogenetic tree shows HIV-1 groups M, O, and N and subtypes and CRFs within the M group. The phylogenetic analysis was performed on nearly full-length sequences and is based on the neighbor-joining method. The internal branches defining a subtype have been estimated from 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Moreover, within a subtype, it is possible to identify groups of viral isolates forming genetically related sister clades, termed subsubtypes (109), which appear to be phylogenetically more closely related to each other than to other subtypes. This is the case with the A and F clades, whose members are currently classified into subsubtypes A1 to A2 and F1 to F2, respectively (42, 123). Clades B and D are more closely related to each other than to other subtypes, and clade D is considered the early clade B African variant, but their original designation as subtypes is retained by authors for consistency with earlier published works (40, 74).

Classification of HIV-1 subtypes was originally based on the subgenomic regions of individual genes. However, with an increasing number of viral isolates available worldwide and improvements in sequencing methods, HIV-1 phylogenetic classifications are currently based either on nucleotide sequences derived from multiple subgenomic regions (gag, pol, and env) of the same isolates or on full-length genome sequence analysis. This approach has revealed virus isolates in which phylogenetic relations with different subtypes switch along their genomes. These intersubtype recombinant forms are thought to have originated in individuals multiply infected with viruses of two or more subtypes. When an identical recombinant virus is identified in at least three epidemiologically unlinked people and is characterized by full-length genome sequencing, it can be designated as a circulating recombinant form (CRF) (99, 110) (Fig. 1).

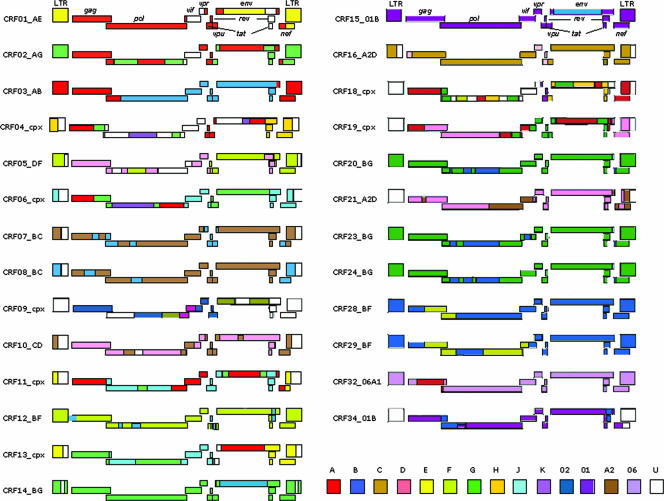

More than 20 CRFs whose origins can be tracked to areas where the parental strains are cocirculating have been reported (Fig. 2). Cocirculation of multiple subtypes and CRFs in the same populations increases the probability that individuals will become “superinfected” with different HIV-1 genetic forms which can swap parts of their genetic material, resulting in the generation of several recombinants, called “unique recombinant forms,” or URFs, which, if spread to other people, will lead to their classification as CRFs (79).

FIG. 2.

Mosaic structure of HIV-1 CRFs. All CRFs that have been described to date are shown (modified from http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/CRFs/CRFs.html). The letters and graphic patterns represent the different subtypes of HIV-1 involved in the recombination events. U, unknown.

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF HIV-1 SUBTYPES

Molecular epidemiological studies show that, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa, where almost all subtypes, CRFs, and several URFs have been detected, there is a specific geographic distribution pattern for HIV-1 subtypes (55, 97). This distribution pattern seems to be the consequence of either accidental trafficking (viral migration), with a resulting “founder effect,” or a prevalent route of transmission, which results in a strong advantage for and local predominance of the prevalent subtype transmitted in that population (17, 81, 91, 93, 98).

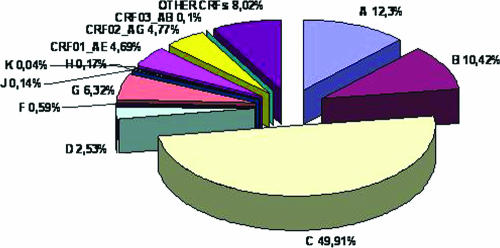

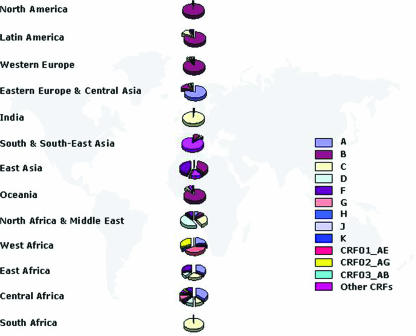

According to recent studies, on a global scale the most prevalent HIV-1 genetic forms are subtypes A, B, and C, with subtype C accounting for almost 50% of all HIV-1 infections worldwide (Fig. 3). Subtype A viruses are predominant in areas of central and eastern Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda) and in eastern European countries formerly constituting the Soviet Union. Subtype B is the main genetic form in western and central Europe, the Americas, and Australia and is also common in several countries of Southeast Asia, northern Africa, and the Middle East and among South African and Russian homosexual men. Subtype C viruses are predominant in those countries with >80% of all global HIV-1 infections, such as southern Africa and India. The relevance of CRFs in the global HIV-1 pandemic is increasingly recognized, accounting for 18% of infections (55, 97) and representing the predominant local form in Southeast Asia (CRF01-AE) (82, 89, 104) and in West and West Central Africa (CRF02-AG) (80, 87) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Global prevalence of HIV-1 genetic forms. The global prevalence of each form, expressed as a percentage of the total number of HIV-1 isolates identified worldwide, is shown. Isolates from HIV-1 groups O and N were not included in this analysis.

FIG. 4.

Global geographical distribution of HIV-1 genetic forms. Genetic forms predominant in different world regions are shown. The pie charts show the prevalence of individual genetic forms in each region.

HIV-1 DIVERSITY AND ITS ORIGIN

Strong phylogenetic evidence suggests that HIV-1 originated by zoonotic cross-species transmission of the simian lentivirus simian immunodeficiency virus SIVcpz from the chimpanzee subspecies Pan troglodytes troglodytes to humans (39). This cross-species transmission could have occurred in West Equatorial Africa from direct exposure to animal blood as a consequence of hunting, butchering, and consumption of raw meat (53). In fact, this region includes countries (Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, and the Republic of Congo) where the following conditions in support of this hypothesis are found: (i) HIV-1 groups M, N, and O cocirculate in human populations; (ii) HIV-1 group M viruses show the greatest diversity (28, 59, 85, 86, 88, 101, 127); and (iii) chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) have been found to be infected with genetically closely related viruses (26, 39, 78, 102, 116). These conditions both support long-lasting circulation of the whole spectrum of the known HIV-1 genetic forms, possibly resulting from multiple founders, and make zoonotic transmission from infected animals to humans plausible.

Moreover, the interspersion of HIV-1 group M, N, and O sequences among different SIVcpz (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) lineages in phylogenetic trees requires that HIV-1 viruses from the three groups originated from no fewer than three separate SIVcpz transmission events (Fig. 5). However, while group M viruses appear to have efficiently adapted to the new host species, spreading all around the world and generating multiple genetic subtypes, the other two groups show less efficient adaptations to humans. HIV-1 group O seems to be endemic to Cameroon and neighboring countries in West Central Africa, where it represents only approximately 1 to 5% of HIV-1-positive samples (102); likewise, group N viruses have been identified only in a limited number of individuals from Cameroon (6, 116). Moreover, group N viruses appear to be the result of a recombination event between an SIVcpz-like and an HIV-1-like virus (39), and their high degree of similarity to chimpanzee viruses may indicate a significantly recent zoonotic cross-species transmission. This evidence suggests that cross-species zoonotic transmissions to humans of additional primate lentiviruses and/or recombinations between HIV-1 viruses and primate lentiviruses may still occur, giving rise to new HIV-1 groups with unpredictable virulence.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic tree of primate lentivirus sequences. Phylogenetic tree analysis was performed by using the neighbor-joining method, based on a 550-base pair pol fragment from SIV and HIV isolates. One isolate per each HIV-1 group M subtype was used. Branch lengths are drawn to scale (the bar indicates 10% divergence). The branches were estimated from 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and only bootstrap values of >80% are shown.

Considering that African primates are the natural hosts of several different lentiviruses (100), it is quite reasonable that such cross-species zoonotic lentivirus transmissions to humans have periodically occurred through the centuries in West Equatorial Africa. Exposure to SIV in natural settings is common for individuals exposed to blood and body fluids of naturally SIV-infected nonhuman primates. However, although there is a significant percentage of seropositivity to SIV antigens in such high-risk groups (17.1%), no productive infection has been detected (60). It has been proposed that the lack of productive infections is a consequence of either exposure to nonviable or defective SIV, a nonproductive cleared infection, or sequestering of the virus in lymphoid tissues. The reason why HIV-1 gave rise to the AIDS pandemic only in the 20th century has not yet been determined but could reasonably be the sum of significant cultural and socio-behavioral changes, the use of nonsterile needles for parenteral injections and vaccinations, and the unwitting contamination of biological products for medical treatments (e.g., oral polio vaccine) (46, 57). The earliest case of HIV-1 infection, dating from 1959, was identified in the Democratic Republic of Congo (134), and using different methods of molecular clock analysis, it has been estimated that HIV-1 group M began to radiate from its source around the 1930s (63, 113).

HIV-1 SUBTYPES AND TRANSMISSION

Diverse risk behaviors sustain HIV-1 transmission in different regions of the world, and within the same region, multiple transmission routes can be involved in spreading the epidemic. For example, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia in 2005, 67% of HIV infections were due to needle sharing among intravenous drug users (IDUs). In South and Southeast Asia, not including India, 49% of HIV infections reported were in commercial sex workers and their clients, while 22% were in IDUs. In Latin America, 26% of HIV infections were in men who have sex with men (MSM), and 19% were in IDUs (http://www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2006GlobalReport/default.asp). In Western Europe, unprotected intercourse among heterosexuals accounted for 45%, and among MSM, 28%, of HIV infections (http://www.eurohiv.org/reports/report_73/pdf/report_eurohiv_73.pdf).

As reported in the previous paragraph, the HIV-1 epidemic in these regions is sustained by different subtypes, and within each region, segregation of subtypes to different risk groups has been reported. For example, the cocirculation of subtype B among IDUs and CRF01_AE (originally defined as subtype E) among heterosexuals was originally described in Thailand (41); the segregation of subtype B to homosexuals and subtype C to heterosexuals was described in South Africa (126); more recently, two concurrent epidemics in Argentina have been reported, one among MSM, sustained by subtype B, and the other among heterosexuals and IDUs, sustained by BF recombinants (5). In Europe, where subtype B has sustained the HIV-1 epidemic among the “historical” IDU and homosexual risk groups, non-B subtypes and CRFs are progressively being introduced in association with increased heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 between migrants and/or immigrants from regions where HIV-1 is endemic and their European partners (19, 20, 121).

All these observations, reported at different phases of the HIV-1 epidemic around the world, may suggest different biological properties for the subtypes, resulting in their segregation among individuals with different risk behaviors for HIV-1 infection. Nevertheless, a consistent demonstration of this association has not been given. There is clearly no predetermined linkage between a specific subtype and a unique mode of transmission. In fact, subtype A is transmitted among heterosexuals in sub-Saharan Africa and IDUs in Eastern Europe; similarly, subtype B is transmitted among all the historical risk groups in Western countries.

Therefore, the apparent segregation of HIV-1 subtypes by type of risk behavior rather than as a result of virologic factors (cell tropism, coreceptor specificity) could derive from genetic, demographic, economic, and social factors that separate the different risk groups for HIV-1 infection. Moreover, the overwhelming predominance of the C subtypes in areas where unprotected heterosexual intercourse is the main transmission route could result from a founder effect with a fast-colonization outcome.

IMPACT OF HIV-1 GENETIC DIVERSITY ON SPECIFICITY AND SENSITIVITY OF DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The genetic variability of HIV-1 may pose significant problems for the specificity and/or sensitivity of serological and molecular diagnostic tests, which may represent a serious risk factor for the spreading of unidentified infections.

Fourth-generation HIV immunoassays are designed to detect both the HIV p24 antigen and antibody in a single test in order to reduce the seroconversion window (131). The sensitivity of these assays for the p24 antigen and seroconversion, however, can vary significantly (76, 130). Nevertheless, recent comparative studies have shown that some of these immunoassays have levels of specificity and sensitivity comparable to those of second- and third-generation assays designed to detect either antigens or antibodies and can identify most of the known group M subtypes, the most diffused CRFs (CRF01_AE and CRF02_AG), and group O viruses (69).

In parallel, a similar comparative study reported on molecular diagnostic tests, which might be even more affected by the high variability of the target HIV-1 nucleotide sequences. Analysis has shown that the widely used real-time RT-PCR for viral load measurements is able to identify all the tested group M and group O isolates within a target concentration ranging from approximately 316,230 copies/ml (5.5 log10) to below 50 copies/ml (1.6 log10), with a coefficient of correlation between 0.991 and 0.999 (120).

Therefore, these reports indicate that the currently used serological and molecular diagnostic tests for HIV-1 are still sufficiently specific and sensitive to detect the most prevalent HIV-1 genetic forms worldwide. Nevertheless, anecdotal unidentified HIV-1 isolates have been reported in primary HIV-1 infection cohorts in monoclade HIV epidemics (21). Therefore, the continuous genetic variation and intersubtype recombination events make frequent evaluation analyses of the diagnostic tests and, possibly, national registries to report undiagnosed cases necessary. These measures would help greatly in keeping the diagnostic capacity of the tests up to date.

CORRELATION BETWEEN HIV-1 GENETIC DIVERSITY AND DRUG RESISTANCE

The genetic variability characterizing the different HIV-1 subtypes and CRFs also affects the protease and RT genes coding for the viral enzymes that are the main targets of antiretroviral drugs. These polymorphisms, if conferring drug resistance, can be selected by drug-selective pressure and dramatically influence the therapeutic outcome. Alternatively, the polymorphisms do not confer drug resistance but may change the “genetic barrier,” which is defined as the number of viral mutations required to develop escape mutations able to overcome the drug-selective pressure. In general, several mutations are generally required for the virus to become resistant to protease inhibitors (high genetic barrier), whereas a single amino acid substitution can induce resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) (low genetic barrier) (12).

The frequency and pattern among HIV-1 subtypes of polymorphisms inducing resistance per se or leading to a faster emergence of drug resistance under pharmacological pressure have been evaluated in several recent studies. In particular, considering the lack of extensive information on non-B subtypes, which predominate in countries where the availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is very limited, great emphasis has been given to comparative studies of B versus non-B subtypes. In a large European study performed on approximately 2,000 protease and RT gene sequences (>600 non-B) from antiretroviral-naïve patients, a genetic barrier similar for B and non-B subtypes was found at almost all positions (125).

In addition, specific data are available for individual ART drug classes. In regard to the few positions of the protease sequence where differences were found, such as the 82A and 82T polymorphism, the genetic barrier was either lower for subtype C or higher for subtype G, suggesting that non-B subtypes may require even more mutations than B subtypes to develop drug resistance. Moreover, specific polymorphisms in protease positions may confer greater susceptibility to protease inhibitors to other non-B subtypes. In particular, subtype C and CRF02_AG recombinant viruses from drug-naïve patients show an in vitro hypersusceptibility to protease inhibitors (1, 48), a finding which needs to be confirmed by in vivo clinical studies.

Extensive differences between the subtypes were found for the minor protease substitutions, which do not impair drug susceptibility but may affect the genetic pathway of resistance once the virus generates a relevant major substitution (47, 83, 106). This finding implies that a faster emergence of drug resistance to a particular protease inhibitor could be expected in some non-B subtypes.

In regard to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor compounds, non-B subtypes do not show a lower genetic barrier in any resistance-associated substitutions, indicating evolution to the drug-resistance phenotype at a rate comparable to that of subtype B isolates. For NNRTI resistance-related substitutions, the most relevant finding is the reduced genetic barrier for the V106M substitution in subtype C, which has been observed in different studies and which confers high-level resistance to all NNRTIs (16, 124, 125). In particular, the V106M mutation in RT is facilitated in subtype C by a single transition (GTG to ATG), compared to two transitions in viruses of other subtypes (GTA to ATG). Moreover, natural resistance to NNRTIs has been observed in patients carrying group O HIV-1 viruses (29, 107), and it is believed to have a genetic basis relating to the natural RT Y181C polymorphism, similar to the Y181I divergence seen in naturally NNRTI-resistant HIV-2 (117).

All these in vitro genetic studies showing both the absence of naïve drug resistance mutations in non-B subtypes and substantial similarity between B and non-B subtypes in the degree of probability that they will develop drug resistance are confirmed by a generally conserved drug susceptibility in vivo. In fact, HIV-1 subtypes do not appear to affect the efficacy of first-line therapy and currently available protease and RT inhibitors are equally active on all HIV-1 subtypes (3, 13, 37, 103). A global collaborative study based on non-B subtype sequences from 3,686 individuals showed (i) that most of the protease and RT positions associated with drug resistance in subtype B viruses are selected by ART in one or more non-B subtypes as well and (ii) that no evidence is available that non-B viruses develop resistance by mutations at positions that are not associated with resistance in subtype B viruses (61). However, a few exceptions to this general rule have been reported in ART-treated patients. Subtype C viruses show a faster emergence of drug resistance to NNRTIs resulting from the appearance of the V106M mutation (73). A Ugandan study to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 showed that a single dose of nevirapine induced more frequent selection of genotypic mutations associated with resistance to nevirapine in women infected with subtype D than in women infected with subtype A viruses (34).

In contrast to the overall extensive genetic variability along the HIV-1 genome, the overall observed genetic similarities in the drug resistance-related codons among HIV-1 subtypes can be explained by the biological relevance of such sites. In fact, sequences containing major drug resistance-associated substitutions show reduced fitness, which results in less efficient replication and spread of these viral populations (75, 128).

HIV-1 GENETIC DIVERSITY AND VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

Transmission of HIV in the general population can possibly be blocked by an effective, safe, and affordable anti-HIV-1 vaccine, which should induce a strong humoral, as well as cellular, immune response against the whole array of HIV-1 genetic forms.

The significant intra- and intersubtype variability of the HIV-1 envelope protein (58, 64, 68, 70, 92, 109), the main target of a preventive and possibly sterilizing vaccine approach, together with the undeniable “fiasco” of the first clinical trial of a phase III vaccine based on a monomeric gp120 (35, 50), has drastically driven the HIV-1 vaccine field in recent years toward the development of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)-inducing vaccine approaches. This approach is also based on early observations of the strong correlation between the anti-HIV-1 CTL response and disease progression (67, 90, 95). Moreover, CTL responses can be raised against Gag and Pol proteins, which are less variable proteins, possibly circumventing the variability of the virus as well as the necessity of using HIV vaccine candidates that correspond to the HIV-1 strains prevalent in the target population.

In support of this strategy, promising broad cross-clade cellular immunity against specific HIV-1 epitopes has been described (27, 45, 51, 133); however, only a few epitopes are conserved across different subtypes, and single amino acid substitutions are selected by the CTL immune pressure, allowing the virus to escape with a dramatic deterioration of clinical conditions (8, 9). Moreover, several studies have identified sequence variability within, as well as proximal to, characterized optimal epitopes, which can either modulate binding to the HLA molecule, reduce the binding affinity to the cognate T-cell receptor, or interfere with efficient antigen processing, resulting in escape from CTL surveillance (4, 14, 31, 71).

As a consequence, it is now currently believed that an anti-HIV-1 vaccine should elicit efficient cellular, as well as humoral, immune responses and, in particular, broadly anti-envelope neutralizing antibodies able to target the largest number of HIV-1 genetic forms. Most of the envelope immunogens developed, however, have failed to achieve this objective (11, 23, 77).

Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies targeting different epitopes in gp120 and gp41 have been obtained from naturally infected individuals (for a comprehensive review, see Srivastava et al., [119]), suggesting that envelope immunogens able to raise such a broad neutralizing response can be generated. However, polyspecific reactivity of some of these monoclonal antibodies with autoantigens has recently been reported, raising serious doubts about the possibility of eliciting such broad anti-HIV humoral responses in vaccinees (2, 54). Nevertheless, using this concept, a few laboratories are currently focusing on designing an HIV vaccine by following a “working backwards“ strategy, consisting of isolating and characterizing human/animal antibodies that can neutralize a broad range of HIV strains and then using these antibodies to identify the HIV target regions to be incorporated into vaccines. The effectiveness of such vaccine candidates in developing protective immunity will be tested in the near future.

In the meantime, several strategies have been developed to engineer envelope immunogens presenting epitopes able to induce neutralizing antibodies with broad efficacy against T-cell-adapted as well as primary HIV-1 isolates (7, 18, 22, 32, 36, 118, 132).

Furthermore, the genetic diversity of HIV-1 and the distribution of different subtypes in each population is currently being addressed by vaccine approaches based on either multivalent formulations or consensus and ancestral sequences. The first approach is based on using envelope molecules from different HIV-1 subtypes in order to induce antibodies with a broader breadth of neutralizing activities (15, 24, 25, 49, 111, 112, 115). The second approach is based on computer-derived sequences (“consensus sequences”) generated by aligning circulating primary isolates and selecting the most common nucleotide at each position. The resulting inferred genes are in an intermediate position within an evolutionary tree, being equidistant from the currently circulating isolates (30, 33, 44, 62, 94). However, these presumed consensus sequences are subject to sampling bias and may include polymorphisms, posttranslational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) that do not reflect the naturally spreading viruses, which may severely influence their antigenicity and immunogenicity. For example, out of five envelope consensus and ancestral sequences generated (30, 43, 65, 66, 72, 129), only one envelope consensus of the group M sequences has been shown to elicit high titers of neutralizing antibodies effective against primary isolates from three different group M clades (72).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The genetic complexity of the worldwide HIV-1 epidemic is still growing, with continuous molecular evolution of existing subtypes and identification of new CRFs, as well as URFs. The B subtype is still predominant in Western countries, with a progressive introduction of non-B subtypes from countries with higher levels of epidemic disease, while subtype C represents the most prevalent form globally. A founder effect with a fast-colonization outcome, along with genetic, demographic, economic, and social factors, appears to explain this epidemic distribution of different subtypes. The available serological and molecular diagnostic tools show levels of specificity and sensitivity appropriate for identifying the broad spectrum of circulating genetic variants. The antiretroviral drugs currently used are equally active on all HIV-1 subtypes (with the exception of group O viruses, which are resistant to NNRTIs), although subtype-related differences in the rate of drug resistance emergence strongly suggest the need for HIV-1 presubtyping to guide selection of the appropriate therapeutic strategy. The development of an effective anti-HIV-1 preventive vaccine with broad efficacy against the vast array of HIV-1 genetic forms is still a “work in progress.” However, it is extremely relevant that vaccines targeted to subtypes other than B are now being developed, a model which did not have many fans until a few years ago. This modified attitude, together with the growing body of information and better technologies, should accelerate the process of developing vaccines with the desired broad immunoprotection efficacy. Efforts to meet the unprecedented challenge to develop such vaccines, which is perceived as a difficult-to-achieve goal, may benefit from understanding the exceptional cross-species transmission of SIV to humans.

In conclusion, continuing studies of HIV-1 molecular phylogenetics are necessary to trace the genetic evolution of the virus and to keep the diagnostic, preventive (vaccine), and therapeutic tools necessary to control the spread of the global HIV-1 epidemic up to date.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministero Italiano della Sanità (Ricerca Corrente and Progetto Finalizzato AIDS 2006) and the ICSC-World Lab, Lausanne, Switzerland (project MCD-2/7).

We are grateful to Marv Reitz (Institute of Human Virology, Baltimore, MD) for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abecasis, A. B., K. Deforche, L. T. Bacheler, P. McKenna, A. P. Carvalho, P. Gomes, A. M. Vandamme, and R. J. Camacho. 2006. Investigation of baseline susceptibility to protease inhibitors in HIV-1 subtypes C, F, G and CRF02_AG. Antivir. Ther. 11:581-589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam, S. M., M. McAdams, D. Boren, M. Rak, R. M. Scearce, F. Gao, Z. T. Camacho, D. Gewirth, G. Kelsoe, P. Chen, and B. F. Haynes. 2007. The role of antibody polyspecificity and lipid reactivity in binding of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 envelope human monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to glycoprotein 41 membrane proximal envelope epitopes. J. Immunol. 178:4424-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander, C. S., V. Montessori, B. Wynhoven, W. Dong, K. Chan, M. V. O'Shaughnessy, T. Mo, M. Piaseczny, J. S. Montaner, and P. R. Harrigan. 2002. Prevalence and response to antiretroviral therapy of non-B subtypes of HIV in antiretroviral-naive individuals in British Columbia. Antivir. Ther. 7:31-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, X. G. Yu, K. M. O'Sullivan, M. Lichterfeld, G. S. Le, M. John, B. R. Mothe, P. K. Lee, E. T. Kalife, D. E. Cohen, K. A. Freedberg, D. A. Strick, M. N. Johnston, A. Sette, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, P. J. Goulder, C. Brander, and B. D. Walker. 2004. Selection, transmission, and reversion of an antigen-processing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 78:7069-7078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avila, M. M., M. A. Pando, G. Carrion, L. M. Peralta, H. Salomon, M. G. Carrillo, J. Sanchez, S. Maulen, J. Hierholzer, M. Marinello, M. Negrete, K. L. Russell, and J. K. Carr. 2002. Two HIV-1 epidemics in Argentina: different genetic subtypes associated with different risk groups. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 29:422-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayouba, A., S. Souquieres, B. Njinku, P. M. Martin, M. C. Muller-Trutwin, P. Roques, F. Barre-Sinoussi, P. Mauclere, F. Simon, and E. Nerrienet. 2000. HIV-1 group N among HIV-1-seropositive individuals in Cameroon. AIDS 14:2623-2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett, S. W., S. Lu, I. Srivastava, S. Cherpelis, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, S. Wang, I. Mboudjeka, L. Leung, Y. Lian, A. Fong, C. Buckner, A. Ly, S. Hilt, J. Ulmer, C. T. Wild, J. R. Mascola, and L. Stamatatos. 2001. The ability of an oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope antigen to elicit neutralizing antibodies against primary HIV-1 isolates is improved following partial deletion of the second hypervariable region. J. Virol. 75:5526-5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barouch, D. H., J. Kunstman, J. Glowczwskie, K. J. Kunstman, M. A. Egan, F. W. Peyerl, S. Santra, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, K. Beaudry, G. R. Krivulka, M. A. Lifton, D. A. Gorgone, S. M. Wolinsky, and N. L. Letvin. 2003. Viral escape from dominant simian immunodeficiency virus epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in DNA-vaccinated rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 77:7367-7375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barouch, D. H., J. Kunstman, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, S. Santra, F. W. Peyerl, G. R. Krivulka, K. Beaudry, M. A. Lifton, D. A. Gorgone, D. C. Montefiori, M. G. Lewis, S. M. Wolinsky, and N. L. Letvin. 2002. Eventual AIDS vaccine failure in a rhesus monkey by viral escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 415:335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barré-Sinoussi, F., J. C. Chermann, F. Rey, M. T. Nugeyre, S. Chamaret, J. Gruest, C. Dauguet, C. Axler-Blin, F. Vézinet-Brun, C. Rouzioux, W. Rozenbaum, and L. Montagnier. 1983. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 220:868-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddows, S., S. Lister, R. Cheingsong, C. Bruck, and J. Weber. 1999. Comparison of the antibody repertoire generated in healthy volunteers following immunization with a monomeric recombinant gp120 construct derived from a CCR5/CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate with sera from naturally infected individuals. J. Virol. 73:1740-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beerenwinkel, N., M. Daumer, T. Sing, J. Rahnenfuhrer, T. Lengauer, J. Selbig, D. Hoffmann, and R. Kaiser. 2005. Estimating HIV evolutionary pathways and the genetic barrier to drug resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1953-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bocket, L., A. Cheret, S. Deuffic-Burban, P. Choisy, Y. Gerard, X. de la Tribonnière, N. Viget, F. Ajana, A. Goffard, F. Barin, Y. Mouton, and Y. Yazdanpanah. 2005. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype on first-line antiretroviral therapy effectiveness. Antivir. Ther. 10:247-254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brander, C., K. E. Hartman, A. K. Trocha, N. G. Jones, R. P. Johnson, B. Korber, P. Wentworth, S. P. Buchbinder, S. Wolinsky, B. D. Walker, and S. A. Kalams. 1998. Lack of strong immune selection pressure by the immunodominant, HLA-A*0201-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in chronic human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. J. Clin. Investig. 101:2559-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brave, A., K. Ljungberg, A. Boberg, E. Rollman, M. Isaguliants, B. Lundgren, P. Blomberg, J. Hinkula, and B. Wahren. 2005. Multigene/multisubtype HIV-1 vaccine induces potent cellular and humoral immune responses by needle-free intradermal delivery. Mol. Ther. 12:1197-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner, B., D. Turner, M. Oliveira, D. Moisi, M. Detorio, M. Carobene, R. G. Marlink, J. Schapiro, M. Roger, and M. A. Wainberg. 2003. A V106M mutation in HIV-1 clade C viruses exposed to efavirenz confers cross-resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. AIDS 17:F1-F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buonaguro, L., E. Del Gaudio, M. Monaco, D. Greco, P. Corti, E. Beth-Giraldo, F. M. Buonaguro, and G. Giraldo. 1995. Heteroduplex mobility assay and phylogenetic analysis of V3 region sequences of HIV 1 isolates from Gulu, Northern Uganda. J. Virol. 69:7971-7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buonaguro, L., L. Racioppi, M. L. Tornesello, C. Arra, M. L. Visciano, B. Biryahwaho, S. D. K. Sempala, G. Giraldo, and F. M. Buonaguro. 2002. Induction of neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic T lymphocytes in Balb/c mice immunized with virus-like particles presenting a gp120 molecule from a HIV-1 isolate of clade A. Antivir. Res. 54:189-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buonaguro, L., M. Tagliamonte, M. L. Tornesello, and F. M. Buonaguro. 2007. Evolution of the HIV-1 V3 region in the Italian epidemic. New Microbiol. 30:1-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buonaguro, L., M. Tagliamonte, M. L. Tornesello, and F. M. Buonaguro. 2007. Genetic and phylogenetic evolution of HIV-1 in a low subtype heterogeneity epidemic: the Italian example. Retrovirology 4:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buonaguro, L., M. Tagliamonte, M. L. Tornesello, E. Pilotti, C. Casoli, A. Lazzarin, G. Tambussi, M. Ciccozzi, G. Rezza, F. M. Buonaguro, et al. 2004. Screening of HIV-1 isolates by reverse heteroduplex mobility assay and identification of non-B subtypes in Italy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 37:1295-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buonaguro, L., M. L. Visciano, M. L. Tornesello, M. Tagliamonte, B. Biryahwaho, and F. M. Buonaguro. 2005. Induction of systemic and mucosal cross-clade neutralizing antibodies in BALB/c mice immunized with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade A virus-like particles administered by different routes of inoculation. J. Virol. 79:7059-7067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bures, R., A. Gaitan, T. Zhu, C. Graziosi, K. M. McGrath, J. Tartaglia, P. Caudrelier, R. El Habib, M. Klein, A. Lazzarin, D. M. Stablein, M. Deers, L. Corey, M. L. Greenberg, D. H. Schwartz, and D. C. Montefiori. 2000. Immunization with recombinant canarypox vectors expressing membrane-anchored glycoprotein 120 followed by glycoprotein 160 boosting fails to generate antibodies that neutralize R5 primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:2019-2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catanzaro, A. T., R. A. Koup, M. Roederer, R. T. Bailer, M. E. Enama, Z. Moodie, L. Gu, J. E. Martin, L. Novik, B. K. Chakrabarti, B. T. Butman, J. G. Gall, C. R. King, C. A. Andrews, R. Sheets, P. L. Gomez, J. R. Mascola, G. J. Nabel, and B. S. Graham. 2006. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-1 candidate vaccine delivered by a replication-defective recombinant adenovirus vector. J. Infect. Dis. 194:1638-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakrabarti, B. K., X. Ling, Z. Y. Yang, D. C. Montefiori, A. Panet, W. P. Kong, B. Welcher, M. K. Louder, J. R. Mascola, and G. J. Nabel. 2005. Expanded breadth of virus neutralization after immunization with a multiclade envelope HIV vaccine candidate. Vaccine 23:3434-3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clewley, J. P. 2004. Enigmas and paradoxes: the genetic diversity and prevalence of the primate lentiviruses. Curr. HIV Res. 2:113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coplan, P. M., S. B. Gupta, S. A. Dubey, P. Pitisuttithum, A. Nikas, B. Mbewe, E. Vardas, M. Schechter, E. G. Kallas, D. C. Freed, T. M. Fu, C. T. Mast, P. Puthavathana, J. Kublin, C. K. Brown, J. Chisi, R. Pendame, S. J. Thaler, G. Gray, J. Mcintyre, W. L. Straus, J. H. Condra, D. V. Mehrotra, H. A. Guess, E. A. Emini, and J. W. Shiver. 2005. Cross-reactivity of anti-HIV-1 T cell immune responses among the major HIV-1 clades in HIV-1-positive individuals from 4 continents. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1427-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaporte, E., W. Janssens, M. Peeters, A. Buvé, G. Dibanga, J. L. Perret, V. Ditsambou, J. R. Mba, M. C. Courbot, A. Georges, A. Bourgeois, B. Samb, D. Henzel, L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, G. van der Groen, and B. Larouzé. 1996. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of HIV infection in Gabon, 1986-1994. AIDS 10:903-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Descamps, D., G. Collin, F. Letourneur, C. Apetrei, F. Damond, I. Loussert-Ajaka, F. Simon, S. Saragosti, and F. Brun-Vézinet. 1997. Susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group O isolates to antiretroviral agents: in vitro phenotypic and genotypic analyses. J. Virol. 71:8893-8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doria-Rose, N. A., G. H. Learn, A. G. Rodrigo, D. C. Nickle, F. Li, M. Mahalanabis, M. T. Hensel, S. McLaughlin, P. F. Edmonson, D. Montefiori, S. W. Barnett, N. L. Haigwood, and J. I. Mullins. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype B ancestral envelope protein is functional and elicits neutralizing antibodies in rabbits similar to those elicited by a circulating subtype B envelope. J. Virol. 79:11214-11224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Draenert, R., G. S. Le, K. J. Pfafferott, A. J. Leslie, P. Chetty, C. Brander, E. C. Holmes, S. C. Chang, M. E. Feeney, M. M. Addo, L. Ruiz, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, M. Altfeld, S. Thomas, Y. Tang, C. L. Verrill, C. Dixon, J. G. Prado, P. Kiepiela, J. Martinez-Picado, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. Immune selection for altered antigen processing leads to cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape in chronic HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 199:905-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Earl, P. L., W. Sugiura, D. C. Montefiori, C. C. Broder, S. A. Lee, C. Wild, J. Lifson, and B. Moss. 2001. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp140. J. Virol. 75:645-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellenberger, D. L., B. Li, L. D. Lupo, S. M. Owen, J. Nkengasong, M. S. Kadio-Morokro, J. Smith, H. Robinson, M. Ackers, A. Greenberg, T. Folks, and S. Butera. 2002. Generation of a consensus sequence from prevalent and incident HIV-1 infections in West Africa to guide AIDS vaccine development. Virology 302:155-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eshleman, S. H., G. Becker-Pergola, M. Deseyve, L. A. Guay, M. Mracna, T. Fleming, S. Cunningham, P. Musoke, F. Mmiro, and J. B. Jackson. 2001. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) subtype on women receiving single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis to prevent HIV-1 vertical transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 184:914-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flynn, N. M., D. N. Forthal, C. D. Harro, F. N. Judson, K. H. Mayer, and M. F. Para. 2005. Placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine to prevent HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 191:654-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fouts, T., K. Godfrey, K. Bobb, D. Montefiori, C. V. Hanson, V. S. Kalyanaraman, A. Devico, and R. Pal. 2002. Crosslinked HIV-1 envelope-CD4 receptor complexes elicit broadly cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11842-11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frater, A. J., D. T. Dunn, A. J. Beardall, K. Ariyoshi, J. R. Clarke, M. O. McClure, and J. N. Weber. 2002. Comparative response of African HIV-1-infected individuals to highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 16:1139-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallo, R. C., P. S. Sarin, E. P. Gelmann, M. Robert-Guroff, E. Richardson, V. S. Kalyanaraman, D. Mann, G. D. Sidhu, R. E. Stahl, S. Zolla-Pazner, J. Leibowitch, and M. Popovic. 1983. Isolation of human T-cell leukemia virus in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 220:865-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao, F., E. Bailes, D. L. Robertson, Y. Chen, C. M. Rodenburg, S. F. Michael, L. B. Cummins, L. O. Arthur, M. Peeters, G. M. Shaw, P. M. Sharp, and B. H. Hahn. 1999. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature 397:436-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao, F., S. G. Morrison, D. L. Robertson, C. L. Thornton, S. Craig, G. Karlsson, J. Sodroski, M. Morgado, B. Galvao-Castro, H. von Briesen, S. Beddows, J. Weber, P. M. Sharp, G. M. Shaw, B. H. Hahn, et al. 1996. Molecular cloning and analysis of functional envelope genes from human deficiency virus type 1 sequence subtypes A through G. J. Virol. 70:1651-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao, F., D. L. Robertson, S. Morrison, H. Hui, S. Craig, J. M. Decker, P. N. Fultz, M. Girard, G. M. Shaw, B. H. Hahn, and P. M. Sharp. 1996. The heterosexual human immunodeficiency virus type 1 epidemic in Thailand is caused by an intersubtype (A/E) recombinant of African origin. J. Virol. 70:7013-7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao, F., N. Vidal, Y. Li, S. A. Trask, Y. Chen, L. G. Kostrikis, D. D. Ho, J. Kim, M.-D. Oh, K. Choe, M. Salminen, D. L. Robertson, G. M. Shaw, B. H. Hahn, and M. Peeters. 2001. Evidence of two distinct subsubtypes within the HIV-1 subtype A radiation. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:675-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao, F., E. A. Weaver, Z. Lu, Y. Li, H.-X. Liao, B. Ma, S. M. Alam, R. M. Scearce, L. L. Sutherland, J.-S. Yu, J. M. Decker, G. M. Shaw, D. C. Montefiori, B. T. Korber, B. H. Hahn, and B. F. Haynes. 2005. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of a synthetic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M consensus envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 79:1154-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaschen, B., J. Taylor, K. Yusim, B. Foley, F. Gao, D. Lang, V. Novitsky, B. Haynes, B. H. Hahn, T. Bhattacharya, and B. Korber. 2002. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science 296:2354-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geels, M. J., S. A. Dubey, K. Anderson, E. Baan, M. Bakker, G. Pollakis, W. A. Paxton, J. W. Shiver, and J. Goudsmit. 2005. Broad cross-clade T-cell responses to Gag in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 non-B clades (A to G): importance of HLA anchor residue conservation. J. Virol. 79:11247-11258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldberg, B., and R. B. Stricker. 2000. Bridging the gap: human diploid cell strains and the origin of AIDS. J. Theor. Biol. 204:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez, L. M. F., R. M. Brindeiro, R. S. Aguiar, H. S. Pereira, C. M. Abreu, M. A. Soares, and A. Tanuri. 2004. Impact of nelfinavir resistance mutations on in vitro phenotype, fitness, and replication capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with subtype B and C proteases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3552-3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez, L. M. F., R. M. Brindeiro, M. Tarin, A. Calazans, M. A. Soares, S. Cassol, and A. Tanuri. 2003. In vitro hypersusceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C protease to lopinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2817-2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graham, B. S., R. A. Koup, M. Roederer, R. T. Bailer, M. E. Enama, Z. Moodie, J. E. Martin, M. M. McCluskey, B. K. Chakrabarti, L. Lamoreaux, C. A. Andrews, P. L. Gomez, J. R. Mascola, and G. J. Nabel. 2006. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-1 DNA candidate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 194:1650-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graham, B. S., and J. R. Mascola. 2005. Lessons from failure—preparing for future HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials. J. Infect. Dis. 191:647-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta, S. B., C. T. Mast, N. D. Wolfe, V. Novitsky, S. A. Dubey, E. G. Kallas, M. Schechter, B. Mbewe, E. Vardas, P. Pitisuttithum, D. Burke, D. Freed, R. Mogg, P. M. Coplan, J. H. Condra, R. S. Long, K. Anderson, D. R. Casimiro, J. W. Shiver, and W. L. Straus. 2006. Cross-clade reactivity of HIV-1-specific T-cell responses in HIV-1-infected individuals from Botswana and Cameroon. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 42:135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gurtler, L., J. Eberle, A. von Brunn, S. Knapp, H. P. Hauser, L. Zekeng, J. M. Tsague, E. Selegny, and L. Kaptue. 1994. A new subtype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (MVP-5180) from Cameroon. J. Virol. 68:1581-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hahn, B. H., G. M. Shaw, K. M. De Cock, and P. M. Sharp. 2000. AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Science 287:607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haynes, B. F., J. Fleming, E. W. St. Clair, H. Katinger, G. Stiegler, R. Kunert, J. Robinson, R. M. Scearce, K. Plonk, H. F. Staats, T. L. Ortel, H. X. Liao, and S. M. Alam. 2005. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science 308:1906-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemelaar, J., E. Gouws, P. D. Ghys, and S. Osmanov. 2006. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS 20:W13-W23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ho, D. D., A. U. Neumann, A. S. Perelson, J. Chen, J. M. Leonard, and M. Markowitz. 1995. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infections. Nature 373:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hooper, E. 2000. Search for the origin of HIV and AIDS. Science 289:1140-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janssens, W., L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, J. Motte, M. Peeters, J. N. Nkengasong, P. M. Ndumbe, E. Delaporte, J. L. Perret, C. Atende, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen. 1994. Genetic and phylogenetic analysis of env subtypes G and H in Central Africa. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:877-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janssens, W., J. N. Nkengasong, L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, P. M. Ndumbe, E. Delaporte, M. Peeters, J. L. Perret, A. Ndoumou, C. Atende, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen. 1994. Further evidence of the presence of genetically very aberrant HIV-1 strains in Cameroon and Gabon. AIDS 8:1012-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalish, M. L., N. D. Wolfe, C. B. Ndongmo, J. McNicholl, K. E. Robbins, M. Aidoo, P. N. Fonjungo, G. Alemnji, C. Zeh, C. F. Djoko, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, D. S. Burke, and T. M. Folks. 2005. Central African hunters exposed to simian immunodeficiency virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1928-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kantor, R., D. A. Katzenstein, B. Efron, A. P. Carvalho, B. Wynhoven, P. Cane, J. Clarke, S. Sirivichayakul, M. A. Soares, J. Snoeck, C. Pillay, H. Rudich, R. Rodrigues, A. Holguin, K. Ariyoshi, M. B. Bouzas, P. Cahn, W. Sugiura, V. Soriano, L. F. Brigido, Z. Grossman, L. Morris, A.-M. Vandamme, A. Tanuri, P. Phanuphak, J. N. Weber, D. Pillay, P. R. Harrigan, R. Camacho, J. M. Schapiro, and R. W. Shafer. 2005. Impact of HIV-1 subtype and antiretroviral therapy on protease and reverse transcriptase genotype: results of a global collaboration. PLoS Med. 2:e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korber, B., B. Gaschen, K. Yusim, R. Thakallapally, C. Kesmir, and V. Detours. 2001. Evolutionary and immunological implications of contemporary HIV-1 variation. Br. Med. Bull. 58:19-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korber, B., M. Muldoon, J. Theiler, F. Gao, R. Gupta, A. Lapedes, B. H. Hahn, S. Wolinsky, and T. Bhattacharya. 2000. Timing the ancestor of the HIV-1 pandemic strains. Science 288:1789-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kostrikis, L. G., E. Bagdades, Y. Cao, L. Zhang, D. Dimitriou, and D. D. Ho. 1995. Genetic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains from patients in Cyprus: identification of a new subtype designated subtype I. J. Virol. 69:6122-6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kothe, D. L., J. M. Decker, Y. Li, Z. Weng, F. Bibollet-Ruche, K. P. Zammit, M. G. Salazar, Y. Chen, J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, Z. Moldoveanu, J. Mestecky, F. Gao, B. F. Haynes, G. M. Shaw, M. Muldoon, B. T. Korber, and B. H. Hahn. 2007. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of HIV-1 consensus subtype B envelope glycoproteins. Virology 360:218-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kothe, D. L., Y. Li, J. M. Decker, F. Bibollet-Ruche, K. P. Zammit, M. G. Salazar, Y. Chen, Z. Weng, E. A. Weaver, F. Gao, B. F. Haynes, G. M. Shaw, B. T. Korber, and B. H. Hahn. 2006. Ancestral and consensus envelope immunogens for HIV-1 subtype C. Virology 352:438-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koup, R. A., J. T. Safrit, Y. Cao, C. A. Andrews, G. McLeod, W. Borkowsky, C. Farthing, and D. D. Ho. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuiken, C., B. Foley, B. H. Hahn, F. E. McCutchan, J. W. Mellors, J. I. Mullins, J. Sodroski, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber. 2000. Human retroviruses and AIDS 2000: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acids and amino acid sequences. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico.

- 69.Kwon, J. A., S. Y. Yoon, C. K. Lee, C. S. Lim, K. N. Lee, H. J. Sung, C. A. Brennan, and S. G. Devare. 2006. Performance evaluation of three automated human immunodeficiency virus antigen-antibody combination immunoassays. J. Virol. Methods 133:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leitner, T., A. Alaeus, S. Marquina, E. Lilja, K. Lidman, and J. Albert. 1995. Yet another subtype of HIV type 1? AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:995-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leslie, A. J., K. J. Pfafferott, P. Chetty, R. Draenert, M. M. Addo, M. Feeney, Y. Tang, E. C. Holmes, T. Allen, J. G. Prado, M. Altfeld, C. Brander, C. Dixon, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, S. A. Thomas, A. St. John, T. A. Roach, B. Kupfer, G. Luzzi, A. Edwards, G. Taylor, H. Lyall, G. Tudor-Williams, V. Novelli, J. Martinez-Picado, P. Kiepiela, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat. Med. 10:282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liao, H. X., L. L. Sutherland, S. M. Xia, M. E. Brock, R. M. Scearce, S. Vanleeuwen, S. M. Alam, M. McAdams, E. A. Weaver, Z. Camacho, B. J. Ma, Y. Li, J. M. Decker, G. J. Nabel, D. C. Montefiori, B. H. Hahn, B. T. Korber, F. Gao, and B. F. Haynes. 2006. A group M consensus envelope glycoprotein induces antibodies that neutralize subsets of subtype B and C HIV-1 primary viruses. Virology 353:268-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loemba, H., B. Brenner, M. A. Parniak, S. Ma'ayan, B. Spira, D. Moisi, M. Oliveira, M. Detorio, and M. A. Wainberg. 2002. Genetic divergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Ethiopian clade C reverse transcriptase (RT) and rapid development of resistance against nonnucleoside inhibitors of RT. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2087-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Louwagie, J., F. E. McCutchan, M. Peeters, T. P. Brennan, E. Sanders-Buell, G. A. Eddy, G. van der Groen, K. Fransen, G. M. Gershy-Damet, R. De Leys, and D. S. Burke. 1993. Phylogenetic analysis of gag genes from 70 international HIV-1 isolates provides evidence for multiple genotypes. AIDS 7:769-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lucas, G. M. 2005. Antiretroviral adherence, drug resistance, viral fitness and HIV disease progression: a tangled web is woven. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:413-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ly, T. D., S. Laperche, C. Brennan, A. Vallari, A. Ebel, J. Hunt, L. Martin, D. Daghfal, G. Schochetman, and S. Devare. 2004. Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of six HIV combined p24 antigen and antibody assays. J. Virol. Methods 122:185-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mascola, J. R., S. W. Snyder, O. S. Weislow, S. M. Belay, R. B. Belshe, D. H. Schwartz, M. L. Clements, R. Dolin, B. S. Graham, G. J. Gorse, M. C. Keefer, M. J. McElrath, M. C. Walker, K. F. Wagner, J. G. McNeil, F. E. McCutchan, and D. S. Burke. 1996. Immunization with envelope subunit vaccine products elicits neutralizing antibodies against laboratory-adapted but not primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Infect. Dis. 173:340-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mauclere, P., I. Loussert-Ajaka, F. Damond, P. Fagot, S. Souquieres, L. M. Monny, F. X. Mbopi Keou, F. Barre-Sinoussi, S. Saragosti, F. Brun-Vezinet, and F. Simon. 1997. Serological and virological characterization of HIV-1 group O infection in Cameroon. AIDS 11:445-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McCutchan, F. E. 2006. Global epidemiology of HIV. J. Med. Virol. 78(Suppl. 1):S7-S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McCutchan, F. E., J. K. Carr, M. Bajani, E. Sanders-Buell, T. O. Harry, T. C. Stoeckli, K. E. Robbins, W. Gashau, A. Nasidi, W. Janssens, and M. L. Kalish. 1999. Subtype G and multiple forms of A/G intersubtype recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Nigeria. Virology 254:226-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCutchan, F. E., P. A. Hegerick, T. P. Brennan, P. Phanupak, P. Singharaj, A. Jugsude, P. Berman, A. M. Gray, A. K. Fowler, and D. S. Burke. 1992. Genetic variants of HIV-1 in Thailand. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:1887-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Menu, E., T. X. Truong, M. E. Lafon, T. H. Nguyen, M. C. Muller-Trutwin, T. T. Nguyen, A. Deslandres, G. Chaouat, Q. T. Duong, B. K. Ha, H. J. Fleury, and F. Barre-Sinoussi. 1996. HIV type 1 Thai subtype E is predominant in South Vietnam. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:629-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Menzo, S., A. Castagna, A. Monachetti, H. Hasson, A. Danise, E. Carini, P. Bagnarelli, A. Lazzarin, and M. Clementi. 2004. Resistance and replicative capacity of HIV-1 strains selected in vivo by long-term enfuvirtide treatment. New Microbiol. 27:51-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Michael, N. L. 1999. Host genetic influences on HIV-1 pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:466-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mokili, J. L., M. Rogers, J. K. Carr, P. Simmonds, J. M. Bopopi, B. T. Foley, B. T. Korber, D. L. Birx, and F. E. McCutchan. 2002. Identification of a novel clade of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18:817-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mokili, J. L., C. M. Wade, S. M. Burns, W. A. Cutting, J. M. Bopopi, S. D. Green, J. F. Peutherer, and P. Simmonds. 1999. Genetic heterogeneity of HIV type 1 subtypes in Kimpese, rural Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:655-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Montavon, C., C. Toure-Kane, F. Lieggeois, E. Mpoudi, A. Bourgeois, L. Vergne, J. L. Perret, A. Boumah, E. Saman, S. Mboup, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2000. Most env and gag subtype A HIV-1 viruses circulating in West and West Central Africa are similar to the prototype AG recombinant virus IBNG. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:363-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Montavon, C., C. Toure-Kane, J. N. Nkengasong, L. Vergne, K. Hertogs, S. Mboup, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2002. CRF06-cpx: a new circulating recombinant form of HIV-1 in West Africa involving subtypes A, G, K, and J. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 29:522-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Motomura, K., S. Kusagawa, K. Kato, K. Nohtomi, H. H. Lwin, K. M. Tun, M. Thwe, K. Y. Oo, S. Lwin, O. Kyaw, M. Zaw, Y. Nagai, and Y. Takebe. 2000. Emergence of new forms of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 intersubtype recombinants in central Myanmar. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1831-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Musey, L., J. Hughes, T. Schacker, T. Shea, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 1997. Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Myers, G. 1994. Tenth anniversary perspectives on AIDS. HIV: between past and future. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1317-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Myers, G., K. MacInnes, and B. Korber. 1992. The emergence of simian/human immunodeficiency viruses. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:373-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Naderi, H. R., M. Tagliamonte, M. L. Tornesello, M. Ciccozzi, G. Rezza, R. Farid, F. M. Buonaguro, and L. Buonaguro. 2006. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of HIV-1 variants circulating among injecting drug users in Mashhad-Iran. Infect. Agents Cancer 1:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nickle, D. C., M. A. Jensen, G. S. Gottlieb, D. Shriner, G. H. Learn, A. G. Rodrigo, and J. I. Mullins. 2003. Consensus and ancestral state HIV vaccines. Science 299:1515-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ogg, G. S., X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffer, P. R. Dunbar, M. A. Nowak, S. Monard, J. P. Segal, Y. Cao, S. L. Rowland-Jones, V. Cerundolo, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. F. Nixon, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science 279:2103-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Op de Coul, E. L. M., M. Prins, M. Cornelissen, A. van der Schoot, F. Boufassa, R. P. Brettle, I. Hernandez-Aguado, V. Schiffer, J. McMenamin, G. Rezza, R. Robertson, R. Zangerle, J. Goudsmit, R. A. Coutinho, and V. Lukashov. 2001. Using phylogenetic analysis to trace HIV-1 migration among western European injecting drug users seroconverting from 1984 to 1997. AIDS 15:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Osmanov, S., C. Pattou, N. Walker, B. Schwardlander, J. Esparza, et al. 2002. Estimated global distribution and regional spread of HIV-1 genetic subtypes in the year 2000. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 29:184-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ou, C. Y., Y. Takebe, C. C. Luo, M. Kalish, W. Auwanit, C. Bandea, N. de la Torre, J. L. Moore, G. Schochetman, and S. Yamazaki. 1992. Wide distribution of two subtypes of HIV-1 in Thailand. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:1471-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peeters, M. 2001. Recombinant HIV sequences: their role in the global epidemic, p. 54-72. In C. Kuiken, B. Foley, B. Hahn, F. E. McCutchan, J. W. Mellors, J. I. Mullins, J. Sodroski, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber (ed.), HIV sequence compendium 2000. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM.

- 100.Peeters, M., and V. Courgnaud. 2002. Overview of primate lentiviruses and their evolution in non-human primates in Africa, p. 2-23. In C. Kuiken, B. Foley, E. Freed, B. Hahn, B. Korber, P. A. Marx, F. E. McCutchan, J. W. Mellors, and S. Wolinsky (ed.), HIV sequence compendium 2002. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM.

- 101.Peeters, M., A. Gaye, S. Mboup, W. Badombena, K. Bassabi, M. Prince-David, M. Develoux, F. Liegeois, G. van der Groen, E. Saman, and E. Delaporte. 1996. Presence of HIV-1 group O infection in West Africa. AIDS 10:343-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peeters, M., A. Gueye, S. Mboup, F. Bibollet-Ruche, E. Ekaza, C. Mulanga, R. Ouedrago, R. Gandji, P. Mpele, G. Dibanga, B. Koumare, M. Saidou, E. Esu-Williams, J. P. Lombart, W. Badombena, N. Luo, H. M. Vanden, and E. Delaporte. 1997. Geographical distribution of HIV-1 group O viruses in Africa. AIDS 11:493-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pillay, D., A. S. Walker, D. M. Gibb, A. de Rossi, S. Kaye, M. Ait-Khaled, M. Muñoz-Fernandez, and A. Babiker. 2002. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes on virologic response and emergence of drug resistance among children in the Paediatric European Network for Treatment of AIDS (PENTA) 5 trial. J. Infect. Dis. 186:617-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Piyasirisilp, S., F. E. McCutchan, J. K. Carr, E. Sanders-Buell, W. Liu, J. Chen, R. Wagner, H. Wolf, Y. Shao, S. Lai, C. Beyrer, and X.-F. Yu. 2000. A recent outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in southern China was initiated by two highly homogeneous, geographically separated strains, circulating recombinant form AE and a novel BC recombinant. J. Virol. 74:11286-11295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Popovic, M., M. G. Sarngadharan, E. Read, and R. C. Gallo. 1984. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science 224:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Prado, J. G., S. Franco, T. Matamoros, L. Ruiz, B. Clotet, L. Menendez-Arias, M. A. Martinez, and J. Martinez-Picado. 2004. Relative replication fitness of multi-nucleoside analogue-resistant HIV-1 strains bearing a dipeptide insertion in the fingers subdomain of the reverse transcriptase and mutations at codons 67 and 215. Virology 326:103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Quiñones-Mateu, M. E., J. L. Albright, A. Mas, V. Soriano, and E. J. Arts. 1998. Analysis of pol gene heterogeneity, viral quasispecies, and drug resistance in individuals infected with group O strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:9002-9015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Roberts, J. D., K. Bebenek, and T. A. Kunkel. 1988. The accuracy of reverse transcriptase from HIV-1. Science 242:1171-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Robertson, D. L., J. P. Anderson, J. A. Bradac, J. K. Carr, B. Foley, R. K. Funkhouser, F. Gao, B. H. Hahn, M. Kalish, C. Kuiken, G. H. Learn, T. Leitner, F. E. McCutchan, S. Osmanov, M. Peeters, D. Pieniazek, M. Salminen, P. M. Sharp, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber. 2000. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science 288:55-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Robertson, D. L., J. P. Anderson, J. A. Bradac, J. K. Carr, B. Foley, R. K. Funkhouser, F. Gao, B. H. Hahn, M. L. Kalish, C. Kuiken, G. H. Learn, T. Leitner, F. E. McCutchan, S. Osmanov, M. Peeters, D. Pieniazek, M. Salminen, P. M. Sharp, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber. 2000. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal, p. 492-505. In C. Kuiken, B. Foley, B. H. Hahn, B. Korber, F. E. McCutchan, P. A. Marx, J. W. Mellors, J. I. Mullins, J. Sodroski, and S. Wolinsky (ed.), Human retroviruses and AIDS, 1999: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM.

- 111.Rollman, E., A. Bråve, A. Boberg, L. Gudmundsdotter, G. Engström, M. Isaguliants, K. Ljungberg, B. Lundgren, P. Blomberg, J. Hinkula, B. Hejdeman, E. Sandström, M. Liu, and B. Wahren. 2005. The rationale behind a vaccine based on multiple HIV antigens. Microbes Infect. 7:1414-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rollman, E., J. Hinkula, J. Arteaga, B. Zuber, A. Kjerrstrom, M. Liu, B. Wahren, and K. Ljungberg. 2004. Multi-subtype gp160 DNA immunization induces broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies. Gene Ther. 11:1146-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Salemi, M., K. Strimmer, W. W. Hall, M. Duffy, E. Delaporte, S. Mboup, M. Peeters, and A. M. Vandamme. 2001. Dating the common ancestor of SIVcpz and HIV-1 group M and the origin of HIV-1 subtypes using a new method to uncover clock-like molecular evolution. FASEB J. 15:276-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sarngadharan, M. G., M. Popovic, L. Bruch, J. Schupbach, and R. C. Gallo. 1984. Antibodies reactive with human T-lymphotropic retroviruses (HTLV-III) in the serum of patients with AIDS. Science 224:506-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Seaman, M. S., L. Xu, K. Beaudry, K. L. Martin, M. H. Beddall, A. Miura, A. Sambor, B. K. Chakrabarti, Y. Huang, R. Bailer, R. A. Koup, J. R. Mascola, G. J. Nabel, and N. L. Letvin. 2005. Multiclade human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope immunogens elicit broad cellular and humoral immunity in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 79:2956-2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Simon, F., P. Mauclère, P. Roques, I. Loussert-Ajaka, M. C. Müller-Trutwin, S. Saragosti, M. C. Georges-Courbot, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and F. Brun-Vézinet. 1998. Identification of a new human immunodeficiency virus type 1 distinct from group M and group O. Nat. Med. 4:1032-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Spira, S., M. A. Wainberg, H. Loemba, D. Turner, and B. G. Brenner. 2003. Impact of clade diversity on HIV-1 virulence, antiretroviral drug sensitivity and drug resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Srivastava, I. K., L. Stamatatos, E. Kan, M. Vajdy, Y. Lian, S. Hilt, L. Martin, C. Vita, P. Zhu, K. H. Roux, L. Vojtech, C. Montefiori, J. Donnelly, J. B. Ulmer, and S. W. Barnett. 2003. Purification, characterization, and immunogenicity of a soluble trimeric envelope protein containing a partial deletion of the V2 loop derived from SF162, an R5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate. J. Virol. 77:11244-11259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Srivastava, I. K., J. B. Ulmer, and S. W. Barnett. 2005. Role of neutralizing antibodies in protective immunity against HIV. Hum. Vaccines 1:45-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Swanson, P., S. Huang, K. Abravaya, C. de Mendoza, V. Soriano, S. G. Devare, and J. Hackett, Jr. 2007. Evaluation of performance across the dynamic range of the Abbott RealTime HIV-1 assay as compared to VERSANT HIV-1 RNA 3.0 and AMPLICOR HIV-1 MONITOR v1.5 using serial dilutions of 39 group M and O viruses. J. Virol. Methods 141:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tagliamonte, M., N. Vidal, M. L. Tornesello, M. Peeters, F. M. Buonaguro, and L. Buonaguro. 2006. Genetic and phylogenetic characterization of structural genes from non-B HIV-1 subtypes in Italy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 22:1045-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Temin, H. M. 1993. Retrovirus variation and reverse transcription: abnormal strand transfers result in retrovirus genetic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6900-6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Triques, K., A. Bourgeois, N. Vidal, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, C. Mulanga-Kabeya, N. Nzilambi, N. Torimiro, E. Saman, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2000. Near-full-length genome sequencing of divergent African HIV-1 subtype F viruses leads to the identification of a new HIV-1 subtype designated K. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:139-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Turner, D., B. Brenner, D. Moisi, M. Detorio, R. Cesaire, T. Kurimura, H. Mori, M. Essex, S. Maayan, and M. A. Wainberg. 2004. Nucleotide and amino acid polymorphisms at drug resistance sites in non-B-subtype variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2993-2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.van de Vijver, D. A., A. M. Wensing, G. Angarano, B. Asjö, C. Balotta, E. Boeri, R. Camacho, M. L. Chaix, D. Costagliola, A. De Luca, I. Derdelinckx, Z. Grossman, O. Hamouda, A. Hatzakis, R. Hemmer, A. Hoepelman, A. Horban, K. Korn, C. Kücherer, T. Leitner, C. Loveday, E. MacRae, I. Maljkovic, C. de Mendoza, L. Meyer, C. Nielsen, E. L. Op de Coul, V. Ormaasen, D. Paraskevis, L. Perrin, E. Puchhammer-Stöckl, L. Ruiz, M. Salminen, J. C. Schmit, F. Schneider, R. Schuurman, V. Soriano, G. Stanczak, M. Stanojevic, A. M. Vandamme, K. Van Laethem, M. Violin, K. Wilbe, S. Yerly, M. Zazzi, and C. A. Boucher. 2006. The calculated genetic barrier for antiretroviral drug resistance substitutions is largely similar for different HIV-1 subtypes. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 41:352-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.van Harmelen, J., R. Wood, M. Lambrick, E. P. Rybicki, A. L. Williamson, and C. Williamson. 1997. An association between HIV-1 subtypes and mode of transmission in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS 11:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vidal, N., M. Peeters, C. Mulanga-Kabeya, N. Nzilambi, D. L. Robertson, W. Ilunga, H. Sema, K. Tshimanga, B. Bongo, and E. Delaporte. 2000. Unprecedented degree of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M genetic diversity in the Democratic Republic of Congo suggests that the HIV-1 pandemic originated in central Africa. J. Virol. 74:10498-10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wainberg, M. A. 2004. The impact of the M184V substitution on drug resistance and viral fitness. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weaver, E. A., Z. Lu, Z. T. Camacho, F. Moukdar, H.-X. Liao, B.-J. Ma, M. Muldoon, J. Theiler, G. J. Nabel, N. L. Letvin, B. T. Korber, B. H. Hahn, B. F. Haynes, and F. Gao. 2006. Cross-subtype T-cell immune responses induced by a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M consensus Env immunogen. J. Virol. 80:6745-6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Weber, B. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antigen-antibody combination assays: evaluation of HIV seroconversion sensitivity and subtype detection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4402-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Weber, B., E. H. Fall, A. Berger, and H. W. Doerr. 1998. Reduction of diagnostic window by new fourth-generation human immunodeficiency virus screening assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2235-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yang, X., R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Improved elicitation of neutralizing antibodies against primary human immunodeficiency viruses by soluble stabilized envelope glycoprotein trimers. J. Virol. 75:1165-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yu, X. G., M. Lichterfeld, B. Perkins, E. Kalife, S. Mui, J. Chen, M. Cheng, W. Kang, G. Alter, C. Brander, B. D. Walker, and M. Altfeld. 2005. High degree of inter-clade cross-reactivity of HIV-1-specific T cell responses at the single peptide level. AIDS 19:1449-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhu, T., B. T. Korber, A. J. Nahmias, E. Hooper, P. M. Sharp, and D. D. Ho. 1998. An African HIV-1 sequence from 1959 and implications for the origin of the epidemic. Nature 391:594-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]