Abstract

Background

For many years amitriptyline has been considered one of the reference compounds for the pharmacological treatment of depression. However, new tricyclic drugs, heterocyclic compounds and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been introduced on the market with the claim of a more favourable tolerability/efficacy profile.

Objectives

The aim of the present systematic review was to investigate the tolerability and efficacy of amitriptyline in comparison with the other tricyclic/heterocyclic antidepressants and with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Search methods

The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register (CCDANCTR‐Studies) was searched on 28‐11‐2005. Reference lists of all included studies were checked.

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials were included. Study participants were of either sex and any age with a primary diagnosis of depression. Included trials compared amitriptyline with another tricyclic/heterocyclic antidepressant or with one of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted using a standardised form. The number of patients undergoing the randomisation procedure, the number of patients who completed the study and the number of improved patients were extracted. In addition, group mean scores at the end of the trial on Hamilton Depression Scale or any other depression scale were extracted. In the tolerability analysis, the number of patients failing to complete the study and the number of patients complaining of side‐effects were extracted.

Main results

A total number of 194 studies were included in the review. The estimate of the overall odds ratio (OR) for responders showed that more subjects responded to amitriptyline in comparison with the control antidepressant group (OR 1.12 to 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 1.23, number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) = 50). The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline and control agents on a continuous outcome revealed an effect size which also significantly favoured amitriptyline (Standardised Mean Difference (SMD) 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.23). Whilst these differences are statistically significant, their clinical significance is less clear. When the efficacy analysis was stratified by drug class, no difference in outcome emerged between amitriptyline and either tricyclic or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor comparators. The dropout rate in patients taking amitriptyline and control agents was similar; however, the estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side‐effects significantly favoured control agents in comparison with amitriptyline (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.74). When the tolerability analysis was stratified by drug class, the dropout rate in patients taking amitriptyline and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors significantly favoured the latter (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.95, number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) = 40). When the responder analysis was stratified by study setting amitriptyline was more effective than control antidepressants in inpatients (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.42, NNTB = 24), but not in outpatients (OR 1.01, 95%CI 0.88 to 1.17, NNTB = 200).

Authors' conclusions

This present systematic review indicates that amitriptyline is at least as efficacious as other tricyclics or newer compounds. However, the burden of side‐effects in patients receiving it was greater. In comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors amitriptyline was less well tolerated, and although counterbalanced by a higher proportion of responders, the difference was not statistically significant.

Keywords: Humans; Amitriptyline; Amitriptyline/therapeutic use; Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic; Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic/therapeutic use; Depression; Depression/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Amitriptyline for depression

Amitriptyline still has a place in the pharmacological management of depressive episodes. The findings of this systematic review showed that in comparison with control agents, amitriptyline was slightly more effective, but the burden of side‐effects was greater for patients receiving it.

Background

Depression is one of the major mental health problems in primary and secondary healthcare settings. It is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity, and creates significant demands on service providers in terms of workload. Treatment is predominantly pharmaceutical or psychological. For many years the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) amitriptyline has been considered one of the reference compounds for the pharmacological treatment of depression. In the last thirty years, however, new tricyclic drugs, heterocyclic compounds and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine and citalopram have been introduced on to the market (Anon 1993 a). As a result, a large number of antidepressant (AD) drugs are now available (Anon 1993 b; Barbui 1999). These new ADs have been compared with amitriptyline in many randomised controlled trials (RCTs), but evidence of advantages, in terms of tolerability and efficacy has not been clearly provided. Therefore, debate persists as to whether amitriptyline should still be considered the reference AD in the pharmacological management of depression.

Amitriptyline has a wide range of pharmacological actions. In addition to the increased receptor site concentration of noradrenaline and serotonin, that is thought to be relevant for the antidepressant effect, amitriptyline has some affinity for the muscarinic, histaminergic and adrenergic systems (Garattini 1988). This affinity is considered significant for most of the side‐effects of amitriptyline. Other TCAs have been shown to act on similar pathways, though to a lesser extent. From a clinical viewpoint, however, trials comparing amitriptyline to the other tricyclic/heterocyclic drugs have failed to clearly demonstrate that amitriptyline is less well tolerated, even though data suggest patients on amitriptyline complain of more side‐effects than those receiving other TCAs.

Some data indicates amitriptyline is less well tolerated in comparison with SSRIs. Systematic reviews comparing the tolerability of TCAs versus SSRIs in terms of patients who fail to complete the study demonstrated a modest advantage of SSRIs in total discontinuation rates (Anderson 1995). The Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment showed that drop‐out rates due to adverse events were 2% lower for SSRIs (CCOHTA 1997). The comparison of SSRIs with old tricyclics (imipramine and amitriptyline), newer tricyclics (dothiepin, nortriptyline, desipramine, clomipramine and doxepin) and heterocyclic antidepressants (bupropion, mianserin, trazodone, maprotiline, amineptine and nomifensine) showed a lower discontinuation rate of the SSRIs only against amitriptyline and imipramine (Hotopf 1997), thus providing evidence that SSRIs are better tolerated than these two old tricyclic antidepressants.

The evidence of the disadvantage of amitriptyline in terms of dropouts against SSRIs must however be weighed against possible advantages in terms of efficacy. Perry (Perry 1996) reviewed the Hamilton scores in trials comparing TCAs with SSRIs and found TCAs more effective than SSRIs in patients suffering from severe depression with melancholic features. Similar conclusions were reached by Joffe (Joffe 1996), who found a nonsignificant advantage of TCAs against SSRIs in terms of effect size, and by Anderson (Anderson 2000), who showed that TCAs appeared more effective in inpatients but not in outpatients with depression.

The present meta‐analysis, which is the updated Cochrane version of a previously published systematic review (Barbui 2001a) was undertaken to test whether amitryptiline is less well tolerated than tricyclic/heterocyclic drugs and SSRIs, and to investigate whether this disadvantage might be counterbalanced by a better efficacy profile. The possible contribution of study setting on treatment outcome was also investigated.

Objectives

To investigate the tolerability and efficacy of amitriptyline in comparison with tricyclic/heterocyclic AD, other related antidepressants and SSRIs; versus tricyclic/heterocyclic and other related antidepressants; and versus SSRIs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials were included.

Types of participants

Study participants were of either sex and any age with a primary diagnosis of depression. Studies adopting any criteria to define patients suffering from depression were included; in addition, a concurrent diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder was not considered an exclusion criteria. AD trials in depressive patients with a concomitant medical illness were not included in this review.

Types of interventions

Included trials compared amitriptyline with another tricyclic/heterocyclic AD or with one of the SSRIs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram).

Types of outcome measures

Efficacy was evaluated using the following outcome measures: (1) number of patients to respond to treatment out of the total number of randomised patients (intention‐to‐treat analysis); (2) group mean scores at the end of the trial on Hamilton Depression Scale (HMD)(Hamilton 1960), or Montgomery Depression Scale (MADRS)(Montgomery 1979), or any depression scale.

Tolerability was evaluated using the following outcome measures: (1) numbers of patients dropping out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients; (2) numbers of patients complaining of side‐effects out of the total number of randomised patients.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic Searches CCDANCTR‐Studies was searched ‐ 28/11/2005 ‐ using the following terms;

Diagnosis = Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Affective Disorder*" and Intervention = Amitriptyline

Reference lists Reference lists of relevant papers and previous systematic reviews were handsearched for published reports and citations of unpublished research.

Data collection and analysis

Duplicate studies Considerable care was taken to exclude duplicate publications and data from single centres contributing to multi‐centre studies. Data extraction Data were extracted using a standard form.

Dichotomous outcomes Two reviewers independently extracted the number of patients undergoing the randomisation procedure, the number of patients who failed to complete the study and that of patients complaining side‐effects. The number of improved patients was extracted in agreement with the definition of responders adopted in the primary studies. When authors did not report any definition of responders, the number of patients showing a 50% reduction in the HMD or MADRS scale was extracted; if these figures were not available, we extracted the number of patients categorised as "much improved" and "improved" at the Clinical Global Impression (CGI), or the number of patients in the corresponding categories at any other rating scale.

Continuous outcomes The mean scores at endpoint, the standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE) of these values, and the number of patients included in these analyses, were extracted. Data were extracted from the HMD. If this scale was not available, data were extracted from the MADRS. If both the HMD and MADRS were not available, data were extracted from any other depression scale. When only the SE was reported, it was converted into SD according to Altman 1996.

Statistical analysis

Measures of treatment effect The primary analysis used a fixed effect approach, the Peto Odds Ratio. In addition, a random‐effects estimate, which takes accounts of any additional between‐study variation, was calculated using a moment estimator of the between‐study variance (Der Simonian 1986) as a sensitivity check on the fixed‐effect estimate.

Tolerability data were analysed by calculating the proportion of patients who failed to complete the study and who experienced adverse reactions out of the total number of randomised patients.

A standardised mean difference (SMD) was estimated for each continuous outcome. This measure provides the effect size of the intervention in units of standard deviations. Scores from different outcome scales can be summarized in an overall SMD.

Management of missing data Responders to treatment were calculated including drop‐outs in the analysis, on an intention‐to‐treat basis. When data on drop‐outs were carried forward and included in the efficacy evaluation (Last Observation Carried Forward, LOCF), they were analysed according to the primary studies; when dropouts were excluded from any assessment in the primary studies they were considered as drug failures (both in the amitriptyline and comparator arms). Scores from continuous outcomes were analysed including patients with a final assessment or with a last observation carried forward to the final assessment.

Exploration of heterogeneity and subgroup analyses Heterogeneity of treatment effect between studies was formally tested using the Chi Square statistic. A subgroup and meta‐regression analysis was carried out using the statistical software STATA 7.0. We investigated the extent that study setting predicted size of treatment effect on response and drop‐out. For the purposes of this analysis, studies carried out in psychiatric wards of general hospitals or in psychiatric hospitals and studies that recruited inpatients in these facilities and followed them up on an outpatient basis were considered RCTs in inpatients. Studies carried out in outpatient psychiatric settings (public or private facilities) or among general practice patients or in any other outpatient services were considered RCTs in outpatients.

Results

Description of studies

Design and setting A total number of 227 RCTs met the inclusion criteria; of these, 33 studies were excluded for the reasons listed in the Table of Excluded Studies. Of the 194 remaining studies, 147 RCTs compared amitriptyline with another TCA or related AD, and 47 RCTs compared amitriptyline with one of the SSRIs. In six studies amitriptyline was administered in combination with perphenazine and in two studies in combination with chlordiazepoxide. In two studies a single blind approach was followed, five studies were not blind, and in other seven studies blindness was not clear. The mean and median sample size was 81.7 patients (SD 81.3) and 51 patients, respectively. The mean and median length of follow‐up was 5.2 weeks (SD 2.22) and 5 weeks, respectively. A total of 54 studies was conducted in inpatient psychiatric settings, whilst 70 were conducted in outpatient settings. In the remaining studies patients were enrolled either in both in and outpatient settings (27 studies), or in a general practice setting (24 studies). The setting was unclear in 19 studies. Participants Most of the included trials enrolled patients suffering from major depression. Five studies enrolled patients with bipolar affective disorder during a depressive episode, whilst six and two trials enrolled patients with mixed anxiety‐depressive syndrome and dysthymic disorder, respectively. In about 27% of the trials the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM) criteria were followed to make the diagnosis (APA 1980; APA 1994). The Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Spitzer 1977), the Feighner (Feighner 1972) criteria and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 1974; WHO 1992) criteria were also used. Fifty three per cent of the studies adopted implicit diagnostic criteria. The severity of illness at baseline was measured with the Hamilton Depression Scale (HMD) or the Montgomery scale (MADRS). The study population mostly involved patients aged between 18 and 65, although in some trials patients above 65 were enrolled.

Risk of bias in included studies

A formal quality assessment was performed using the Quality Rating Scale (QRS) (Moncrieff 2001). The rating system is such that the higher the score, the higher is the quality of the trial. Overall QRS scores for the total sample ranged from 8 to 32, out of a maximum of 46. The mean QRS score was 18.0 (SD 3.99), indicating an average medium/low quality of included RCTs. The mean QRS score for studies comparing amitriptyline with other TCA or related ADs was 17.2 (SD 3.71), and the same figure for studies comparing amitriptyline with the SSRIs was 20.3 (SD 3.94), indicating a higher quality in the latter group of studies (z ‐4.36, p < .001).

Of the 194 RCTs included, only 12 reported a method for concealing allocation. In seven of the 12 RCTs the allocation concealment was inadequate, while in the remaining five it was not used. With regard to blindness, in six RCTs blinding was not clear, and in nine RCTs procedure was single blind only. In the remaining RCTs, double blind was clearly indicated.

Effects of interventions

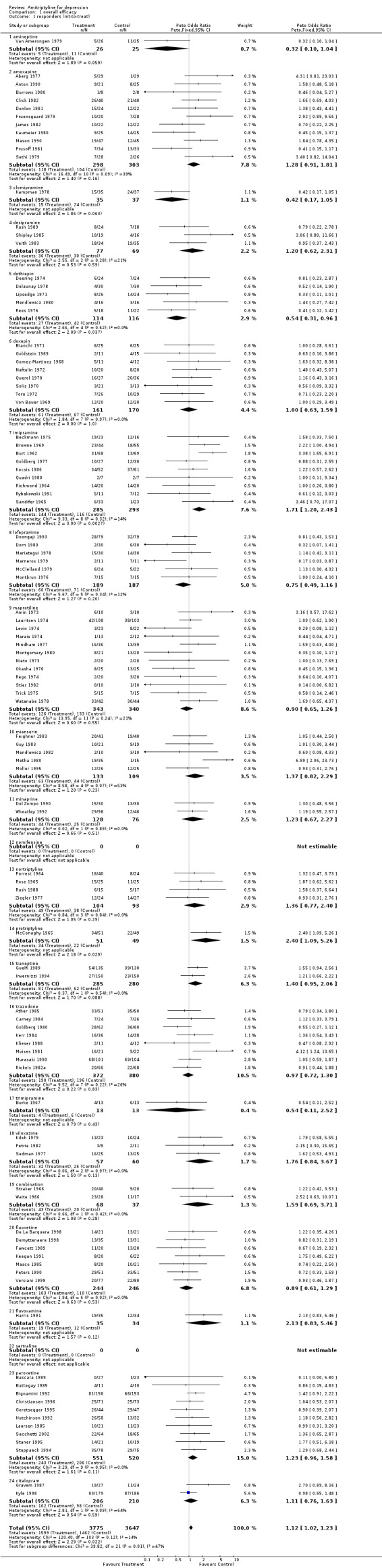

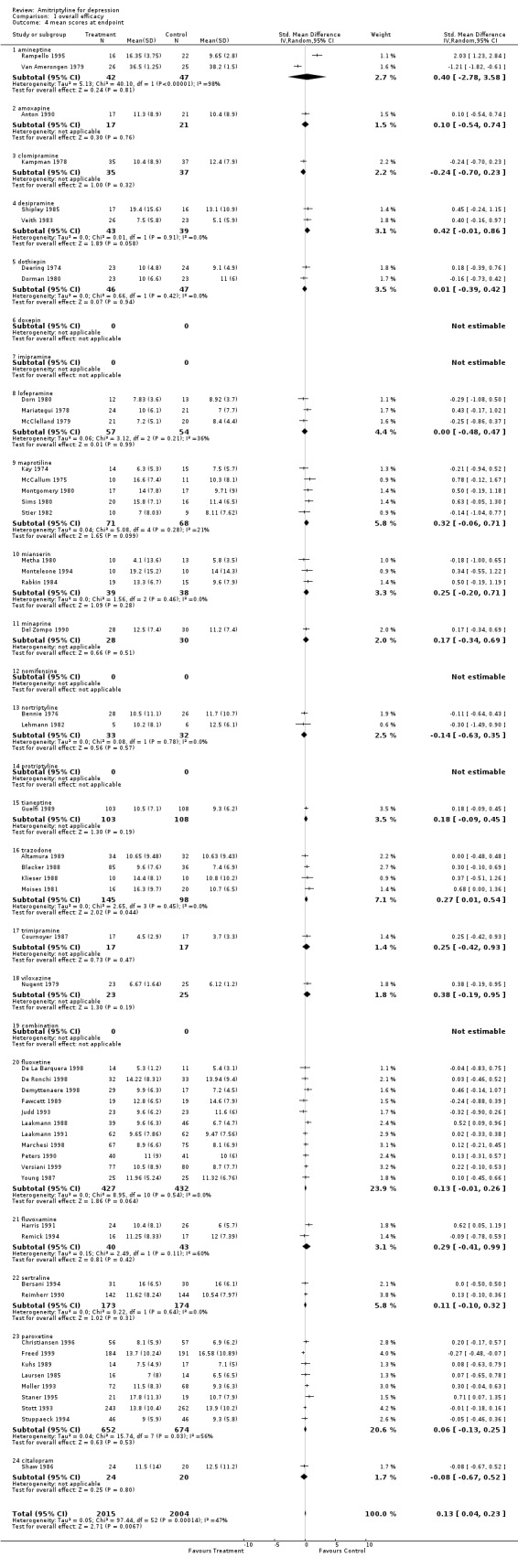

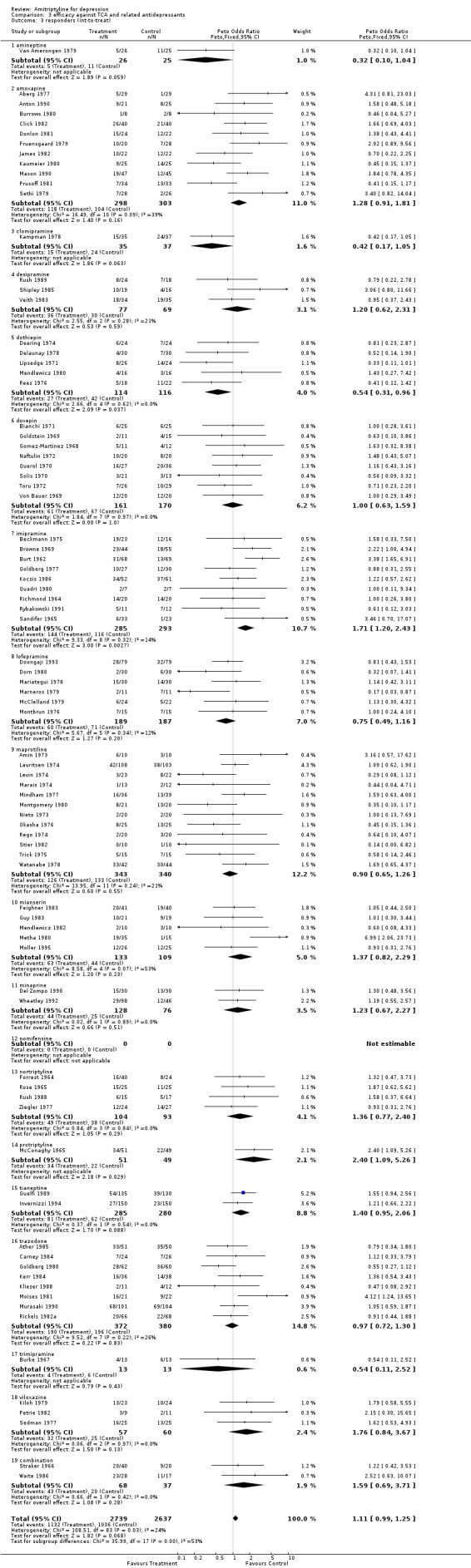

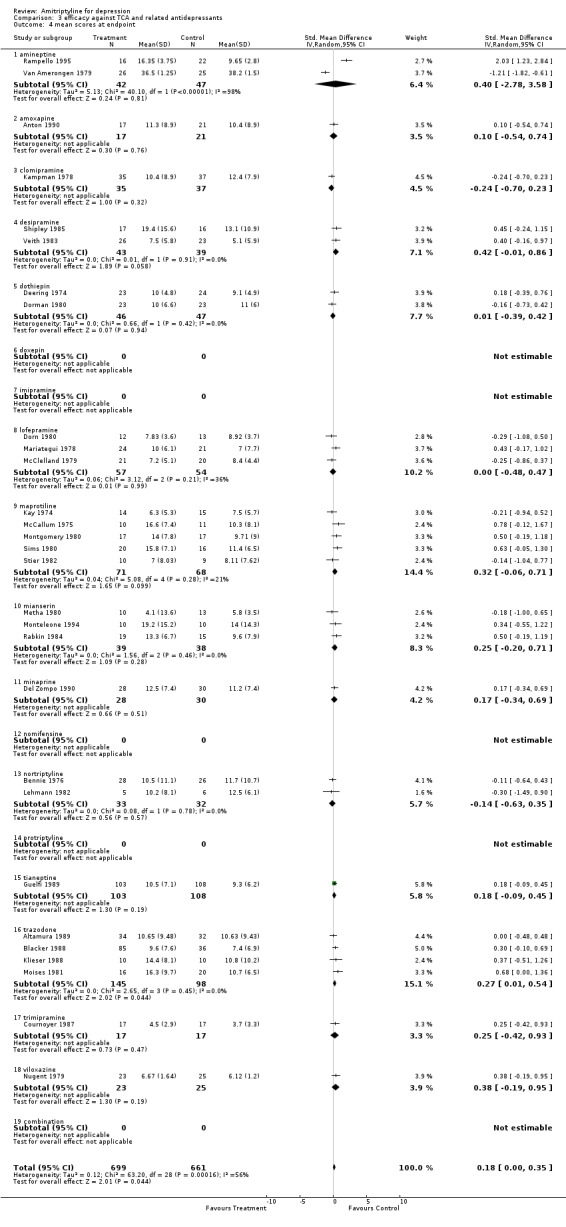

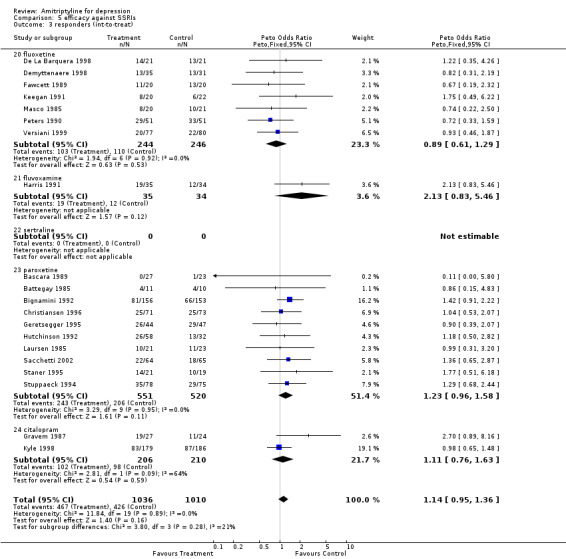

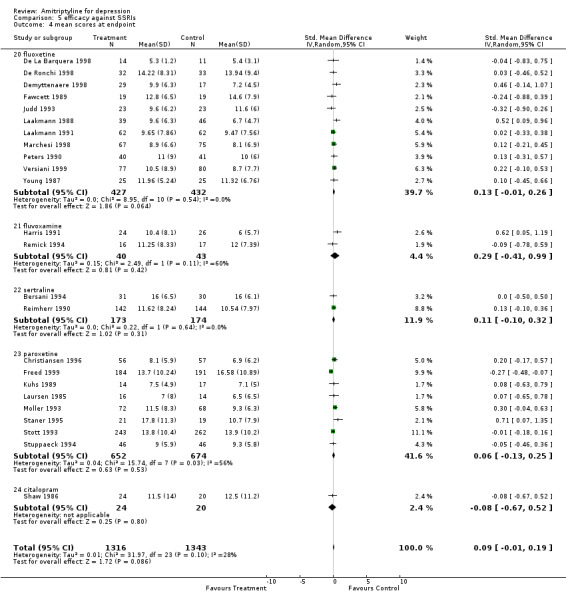

Amitriptyline versus tricyclic/heterocyclic and other related antidepressants and SSRIs Comparison 01: Efficacy of amitriptyline With regards to responders, a total number of 104 RCTs contributed to this analysis, with 7422 patients included (Graph 01.01). The estimate of the overall odds ratio for responders showed that more subjects responded to amitriptyline in comparison with the control AD group (odds ratio (OR) 1.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 1.23). Test for heterogeneity was performed (Chi2=120.40, df= 103 (p=0.12), I2=14.4%). The Number Needed to Treat to Benefit (NNTB) was 50 subjects. The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline and control ADs on continuous measures of depression (Graph 01.04), performed on 2004 and 2015 subjects respectively, included 53 studes and revealed an effect size which also significantly favoured amitriptyline (Standardised Mean Difference (SMD) 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.23). The test for heterogeneity yielded the following result: Chi2=97.44, df= 152 (p=0.0001), I2=46.6%.

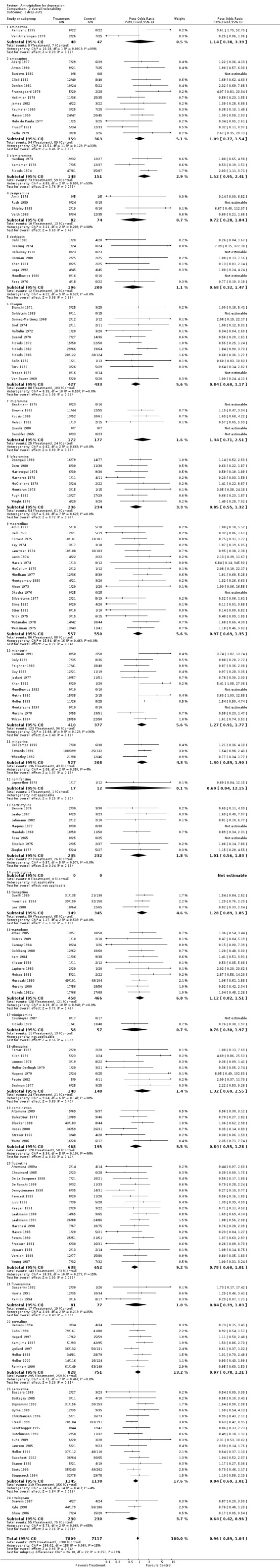

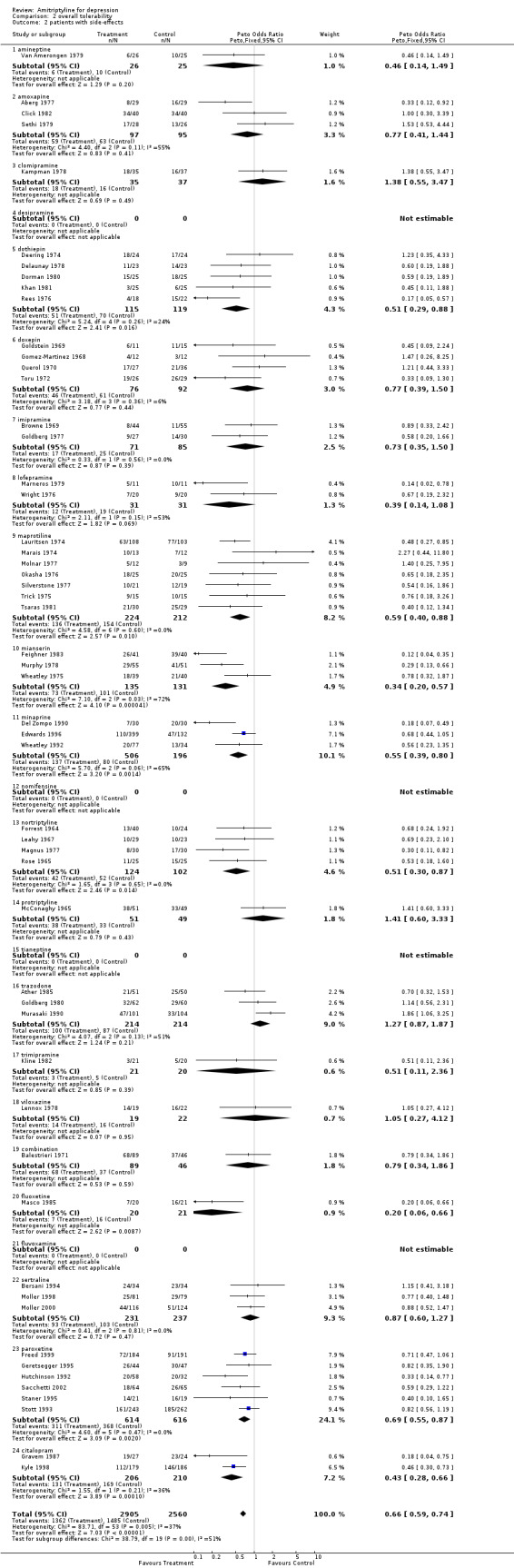

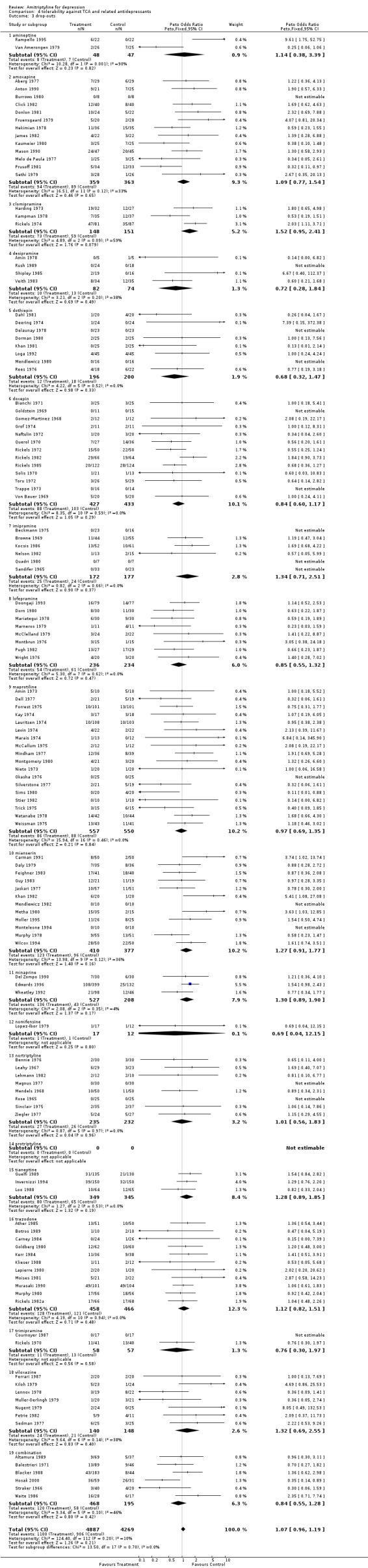

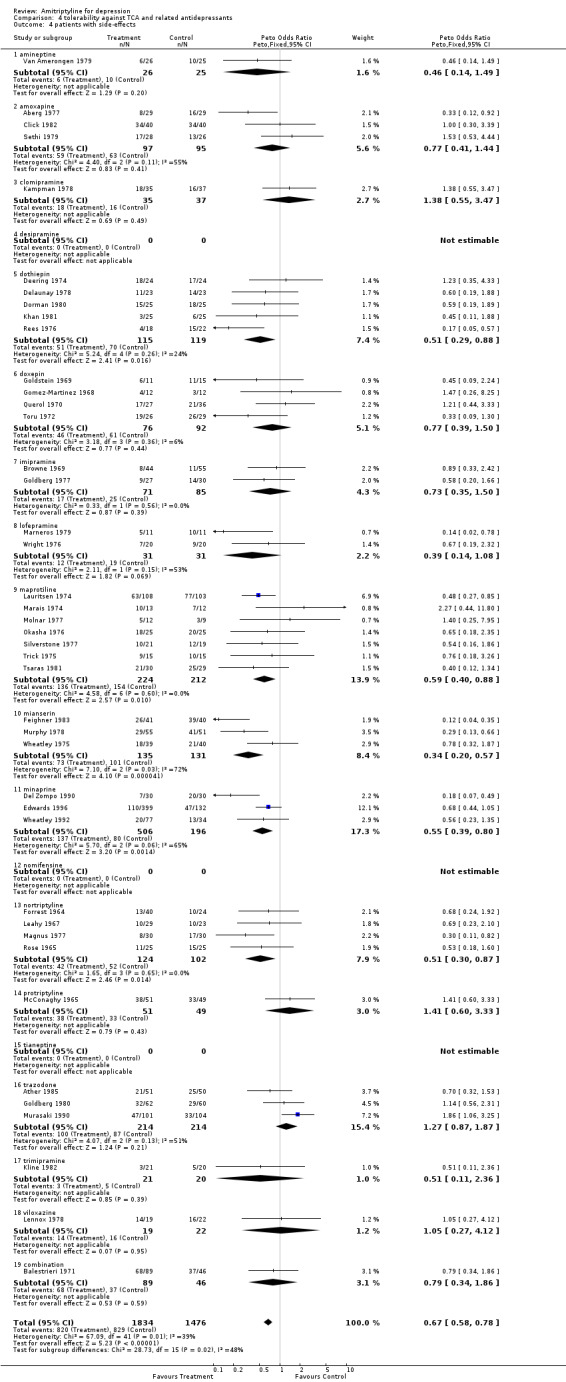

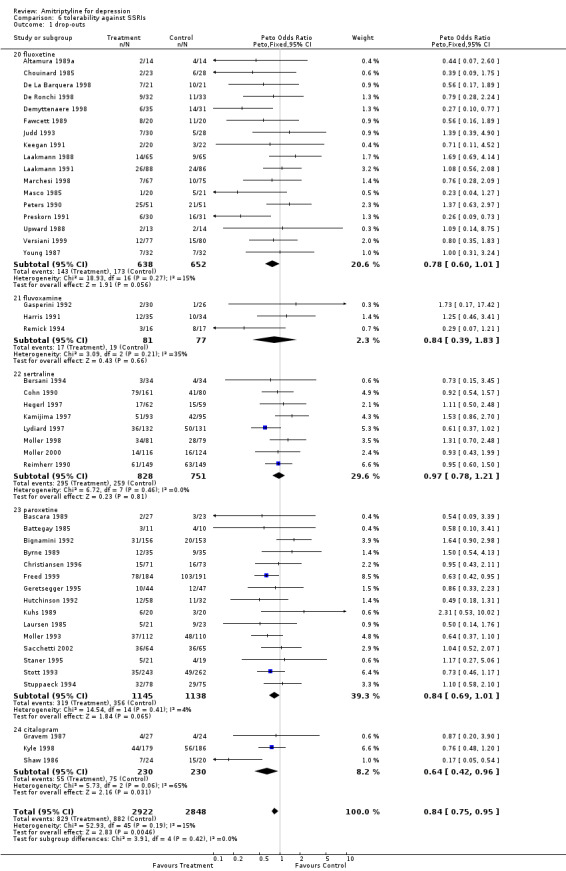

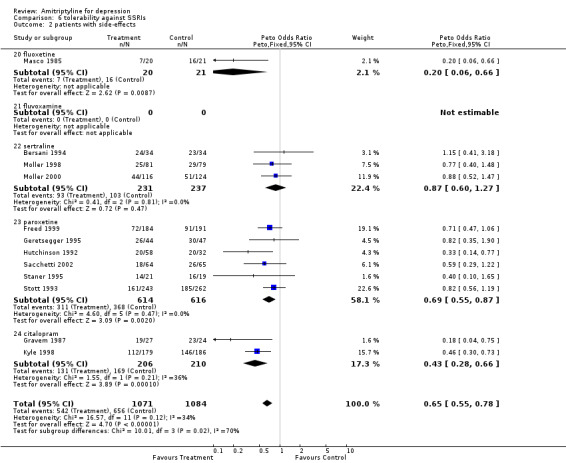

Comparison 02: Tolerability of amitriptyline A total number of 159 RCTs contributed to this analysis, with 14926 patients included. The dropout rate in patients taking amitriptyline and control ADs (analysis 02.01) was similar, yielding an OR of 0.96 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.04; test for heterogeneity: Chi2 =186.02, df=158 (p=0.06), I2 =15.1%). The Number Needed to Treat to Harm (NNTH) was 345 subjects. The estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side‐effects, performed on 54 studies (5465 patients )(analysis 02.02), significantly favoured control ADs in comparison with amitriptyline (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.74; test for heterogeneity: Chi2=83.71, df=53 (p=0.005), I2=36.7%). The NNTH was 8 subjects.

Amitriptyline versus tricyclic/heterocyclic and other related antidepressants Comparison 03: Efficacy against tricyclic/heterocyclic and other related antidepressants The analysis of studies that compared amitriptyline with other TCA and related ADs (Graph 03.03), performed on 84 RCTs (5376 subjects), provided an OR for responders of 1.11 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.25), indicating a non‐significant advantage for amitriptyline (NNTB = 50). Test for heterogeneity showed Chi2 = 108.51, df=83 (p=0.03) and I2=23.5%. The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline in comparison with other TCA and related ADs on continuous measures of depression (Graph 03.04), performed on 29 RCTs (1360 subjects), revealed an effect size that favoured amitriptyline (SMD 0.18 95% CI 0.00 to 0.35), although this figure did not reach significance. A test for heterogeneity yielded the following results: Chi2=63.20, df=28 (p=0.0002) and I2=55.7%.

Comparison 04: Tolerability against tricyclic/heterocyclic and other related antidepressants (Comparison 04) The dropout rate in patients taking amitriptyline and control TCA or related AD (113 RCTs and 9156 subjects; Graph 04.03) was similar, yielding an OR of 1.07 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.19; test for heterogeneity: Chi2 =124.40, df =112 (p=0.20), I2=10.0%) favouring amitriptyline (NNTB = 71). However, the estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side‐effects (42 RCTs and 3310 subjects; Graph 04.04) significantly favoured control TCA or related AD over amitriptyline (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.78; test for heterogeneity: Chi2 = 67.09, df =41 (p=0.006), I2 =38.9%). The NNTH was 9.5 subjects.

Amitriptyline versus SSRIs Comparison 05: Efficacy against SSRIs The analysis of the 20 studies (2046 subjects) that compared amitriptyline with the SSRIs (Graph 05.03) provided an OR of 1.14 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.36), indicating a non‐significant advantage for amitriptyline (test for heterogeneity: Chi2=11.84, df=19 (p=0.89), I2=0%). The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline in comparison with the SSRIs on continuous measures of depression (24 RCTs and 2659 subjects; Graph 05.04) again revealed no statistically significant difference (SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.19; test for heterogeneity: Chi2 =31.97, df =23 (p =0.10), I2 =28.1%). Comparison 06: Tolerability against SSRIs The dropout rate in patients taking amitriptyline and the SSRIs (Graph 06.01), derived from a total number of 46 RCTs (5770 subjects), significantly favoured the latter, yielding an OR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.95; test for heterogeneity: Chi2df =45 (p =0.19), I2 =15.0%) and a NNTH of 40. In addition, the estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side‐effects (performed on 12 RCTs, with 2155 subjects; Graph 06.02), significantly favoured the SSRIs in comparison with amitriptyline (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.76; test for heterogeneity: Chi2 =16.57, df =11 (p =0.12), I2 =33.6%). The NNTH was 10 subjects.

Sub‐group analyses Efficacy and tolerability by study setting On treatment response, amitriptyline resulted more effective than control ADs in inpatients (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.42, NNTB = 24), but not in outpatients (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.17, NNTB = 200). Among inpatients amitriptyline was significantly more effective than TCAs (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.42) and non‐significantly more effective than SSRIs (OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.96). Among outpatients no statistically significant differences emerged between amitriptyline and TCAs (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.17) and between amitriptyline and SSRIs (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.35).

Amitriptyline was less well tolerated than control ADs in outpatients (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81to 0.99, NNTH = 91), but not in inpatients (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.25, NNTB = 77). Among inpatients no statistically significant differences emerged between amitriptyline and TCAs (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.97, 1.38) and between amitriptyline and SSRIs (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.78, 1.24). Among outpatients amitriptyline was significantly less well tolerated in comparison with SSRIs (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.89) but not in comparison with TCAs (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.19).

The predictive effect of study setting on responders and dropouts is presented in Table 01. A positive estimate indicates that the factors included in the meta‐regression model predicted a statistically significant advantage (in terms of responders or dropouts) for amitriptyline in comparison with control ADs; a negative estimate indicates that the factors included in the meta‐regression model predicted a statistically significant disadvantage for amitriptyline in comparison with control ADs. In comparison with studies carried out in inpatients, studies carried out in psychiatric outpatient settings predicted a statistically significant disadvantage for amitriptyline over control AD in terms of treatment responders. Given the fact that subgroup analysis should be interpreted with caution, the findings on the differences between in‐patients and out‐patients are exploratory.

Discussion

This present systematic review of clinical trials comparing amitriptyline with all other AD drugs indicates that overall amitriptyline is slightly more efficacious than the pooled results of other TCA or newer compounds. For the efficacy analysis of continuous measures of depression, the SMD significantly favoured amitriptyline over control ADs. However, this analysis only included patients with a final assessment or patients whose efficacy data were carried forward to the final assessment. Thus patients who dropped out of treatment were often excluded. This would have had the effect of favouring amitriptyline. For the analysis of the binary outcome (responders versus non‐reponders) dropouts were assumed to have failed to improve. This conservative approach, which theoretically takes into consideration efficacy and tolerability within the same outcome measure, yielded an odds ratio which indicated a small but significant advantage for amitriptyline over control ADs. When this analysis was stratified by drug class, the effect size was similar, but was no longer statistically significant because of the smaller sample sizes included in each subgroup analysis.

Amitriptyline was less well tolerated than SSRIs, but this disadvantage was counterbalanced by a slightly higher proportion of responders, yielding a no difference in outcome in terms of responders. In practical terms this suggests that the proportion of improved patients after six to eight weeks of therapy is very similar for amitriptyline and the SSRIs, even taking into consideration the higher dropout rate associated with amitriptyline. Despite this, amitriptyline was found to be associated with more side‐effects, as can be seen by the proportion of subjects who complained adverse reactions during the study period, which was significantly higher in comparison with the SSRIs.

Amitriptyline showed a more favourable profile over control agents in inpatients but not in outpatients. Inpatients with depression responded better to amitriptyline than control TCA or SSRI, although the difference in comparison with SSRIs, calculated on a small number of studies, was not statistically significant. In terms of dropouts, amitriptyline was not less well tolerated either in comparison with control TCA or SSRI. These findings are in agreement with those provided by Anderson (Anderson 1998), who showed that among inpatients with depression TCA resulted more effective than SSRIs, and that overall treatment discontinuation rates were not significantly different. In outpatients with depression, in contrast, amitriptyline was not more effective than control agents and resulted less well tolerated. The role of RCT setting was further confirmed by the meta‐regression model, which demonstrated that studies carried out in inpatients were associated with a significant advantage of amitriptyline over control agents in terms of treatment responders. However, no significant associations emerged when treatment dropouts were entered in the model as the dependent variable.

This study has limitations. Firstly, the findings on dropout rates in this meta‐analysis should be interpreted with care, as reasons for dropping out were not given in a high proportion of trials. There are many different reasons for dropping‐out of treatment, and therefore this measure might be an oversimplification of the true tolerability of amitriptyline. Some studies reported the proportion of subjects who discontinued the study because of side‐effects or AD inefficacy or because of other reasons. These figures were not extracted and analysed because reasons for dropping out were given in some studies only, and in many of these studies they were reported for some drop‐out patients only. Secondly, we observed great variability in the overall quality of included studies. The quality rating showed an overall medium/low quality of studies; moreover, RCTs comparing amitriptyline with control TCA or related AD scored significantly lower than RCTs comparing amitriptyline with the SSRIs. A possible explanation of this is that the majority of studies comparing amitriptyline with other TCAs have been published in the 1960s and 1970s, while those comparing amitriptyline with the SSRIs have been published in the last 20 years. Trial methodology has changed during the last four decades, both in terms of design and statistical techniques, and this may explain the difference in the mean quality score between the two groups of studies (Barbui 2001b). Another study limitation is that heterogeneity was investigated by stratifying the analysis according to study setting only; the role of other study characteristics such as length of follow‐up, diagnostic criteria and outcome measures was not assessed. Although this leaves some uncertainty about the role of these independent variables in influencing the overall treatment effect, the analysis was not stratified because we would have inevitably increased the probability of detecting significant difference by chance, but also because we would have decreased the sample size of each analysis, thus increasing the possibility of detecting borderline findings of uncertain clinical relevance.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Amitriptyline still has a role in the pharmacological management of depressive episodes. It has the edge in terms of efficacy in comparison with control ADs, but patients have to sustain a great burden of side‐effects. From a clinical viewpoint the intriguing issue is to identify subgroups of subjects who could benefit from amitriptyline therapy. Some data suggest that it should be prescribed to patients suffering from severe depression with melancholia, or to patients admitted to hospital because of the severity of symptoms (Perry 1996; Joffe 1996; Anderson 2000). The present review, by showing a more favourable profile of amitriptyline over control agents in inpatients but not in outpatients, supports this suggestion. On the other side, however, it seems reasonable to suggest the use of the SSRIs in patients at suicide risk, since amitriptyline and other TCAs are less safe when taken in overdose (Spigset 1999). Moreover, the cost of fluoxetine and that of other SSRIs has fallen over the last few years, both in the US and in Europe, making these compounds more cost‐effective. Unfortunately, little evidence is available on the long‐term efficacy and tolerability of amitriptyline versus the SSRIs. Many side‐effects are often experienced at the beginning of treatment, and therefore it might be possible that amitriptyline and other TCAs could be more tolerable in the long‐term. However, no data support this speculation.

Implications for research.

Amitriptyline should still be considered a reference comparator in terms of efficacy in clinical trials of new AD drugs. Future studies, however, should adopt a higher standard in terms of design and statistical analysis. The quality rating has in fact shown that a great proportion of studies does not meet the quality requirements to provide reliable findings, especially in terms of sample size and length of follow‐up. The issue of long‐term treatment of depression with respect to efficacy and tolerability should definitely be addressed, as in real‐life conditions patients with depression receive treatment for more than 6‐12 weeks.

In the light of the increasing use of the SSRIs and newer compounds, future research has to clarify the position of amitriptyline and other old compounds in the pharmacological management of depressive episodes. In particular, large pragmatic RCTs should provide direct evidence on whether amitriptyline is cost‐effective in special patient populations, for example hospitalised patients with severe depression.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1999 Review first published: Issue 2, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 May 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CCDAN Editorial Team for their support, information and advice.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. overall efficacy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 responders (int‐to‐treat) | 104 | 7422 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [1.02, 1.23] |

| 1.1 amineptine | 1 | 51 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.10, 1.04] |

| 1.2 amoxapine | 11 | 601 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.91, 1.81] |

| 1.3 clomipramine | 1 | 72 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.17, 1.05] |

| 1.4 desipramine | 3 | 146 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.62, 2.31] |

| 1.5 dothiepin | 5 | 230 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.31, 0.96] |

| 1.6 doxepin | 8 | 331 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.63, 1.59] |

| 1.7 imipramine | 9 | 578 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [1.20, 2.43] |

| 1.8 lofepramine | 6 | 376 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.49, 1.16] |

| 1.9 maprotiline | 12 | 683 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.65, 1.26] |

| 1.10 mianserin | 5 | 242 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.82, 2.29] |

| 1.11 minaprine | 2 | 204 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.67, 2.27] |

| 1.12 nomifensine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.13 nortriptyline | 4 | 197 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.77, 2.40] |

| 1.14 protriptyline | 1 | 100 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.40 [1.09, 5.26] |

| 1.15 tianeptine | 2 | 565 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.95, 2.06] |

| 1.16 trazodone | 8 | 752 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.72, 1.30] |

| 1.17 trimipramine | 1 | 26 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.11, 2.52] |

| 1.18 viloxazine | 3 | 117 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.84, 3.67] |

| 1.19 combination | 2 | 105 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.59 [0.69, 3.71] |

| 1.20 fluoxetine | 7 | 490 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.61, 1.29] |

| 1.21 fluvoxamine | 1 | 69 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [0.83, 5.46] |

| 1.22 sertraline | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.23 paroxetine | 10 | 1071 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.96, 1.58] |

| 1.24 citalopram | 2 | 416 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.76, 1.63] |

| 4 mean scores at endpoint | 53 | 4019 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.23] |

| 4.1 amineptine | 2 | 89 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [‐2.78, 3.58] |

| 4.2 amoxapine | 1 | 38 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.54, 0.74] |

| 4.3 clomipramine | 1 | 72 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.24 [‐0.70, 0.23] |

| 4.4 desipramine | 2 | 82 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [‐0.01, 0.86] |

| 4.5 dothiepin | 2 | 93 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.39, 0.42] |

| 4.6 doxepin | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.7 imipramine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.8 lofepramine | 3 | 111 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.48, 0.47] |

| 4.9 maprotiline | 5 | 139 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [‐0.06, 0.71] |

| 4.10 mianserin | 3 | 77 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐0.20, 0.71] |

| 4.11 minaprine | 1 | 58 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.17 [‐0.34, 0.69] |

| 4.12 nomifensine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.13 nortriptyline | 2 | 65 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.14 [‐0.63, 0.35] |

| 4.14 protriptyline | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.15 tianeptine | 1 | 211 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [‐0.09, 0.45] |

| 4.16 trazodone | 4 | 243 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.01, 0.54] |

| 4.17 trimipramine | 1 | 34 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐0.42, 0.93] |

| 4.18 viloxazine | 1 | 48 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐0.19, 0.95] |

| 4.19 combination | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.20 fluoxetine | 11 | 859 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [‐0.01, 0.26] |

| 4.21 fluvoxamine | 2 | 83 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [‐0.41, 0.99] |

| 4.22 sertraline | 2 | 347 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.10, 0.32] |

| 4.23 paroxetine | 8 | 1326 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.13, 0.25] |

| 4.24 citalopram | 1 | 44 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.67, 0.52] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 overall efficacy, Outcome 1 responders (int‐to‐treat).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 overall efficacy, Outcome 4 mean scores at endpoint.

Comparison 2. overall tolerability.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 drop‐outs | 174 | 14926 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.89, 1.04] |

| 1.1 amineptine | 2 | 95 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.38, 3.39] |

| 1.2 amoxapine | 13 | 722 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.77, 1.54] |

| 1.3 clomipramine | 3 | 299 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.95, 2.41] |

| 1.4 desipramine | 4 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.28, 1.84] |

| 1.5 dothiepin | 8 | 396 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.32, 1.47] |

| 1.6 doxepin | 13 | 860 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.60, 1.17] |

| 1.7 imipramine | 6 | 349 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.71, 2.51] |

| 1.8 lofepramine | 8 | 470 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.55, 1.32] |

| 1.9 maprotiline | 18 | 1107 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.69, 1.35] |

| 1.10 mianserin | 12 | 787 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.91, 1.77] |

| 1.11 minaprine | 3 | 735 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.89, 1.90] |

| 1.12 nomifensine | 1 | 29 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.04, 12.15] |

| 1.13 nortriptyline | 8 | 467 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.56, 1.83] |

| 1.14 protriptyline | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.15 tianeptine | 3 | 694 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.89, 1.85] |

| 1.16 trazodone | 11 | 924 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.82, 1.51] |

| 1.17 trimipramine | 2 | 115 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.30, 1.97] |

| 1.18 viloxazine | 7 | 288 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.69, 2.55] |

| 1.19 combination | 6 | 663 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.55, 1.28] |

| 1.20 fluoxetine | 17 | 1290 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.60, 1.01] |

| 1.21 fluvoxamine | 3 | 158 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.39, 1.83] |

| 1.22 sertraline | 8 | 1579 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.78, 1.21] |

| 1.23 paroxetine | 15 | 2283 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.69, 1.01] |

| 1.24 citalopram | 3 | 460 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.42, 0.96] |

| 2 patients with side‐effects | 54 | 5465 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.59, 0.74] |

| 2.1 amineptine | 1 | 51 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.14, 1.49] |

| 2.2 amoxapine | 3 | 192 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.41, 1.44] |

| 2.3 clomipramine | 1 | 72 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.55, 3.47] |

| 2.4 desipramine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.5 dothiepin | 5 | 234 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.29, 0.88] |

| 2.6 doxepin | 4 | 168 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.39, 1.50] |

| 2.7 imipramine | 2 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.35, 1.50] |

| 2.8 lofepramine | 2 | 62 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.14, 1.08] |

| 2.9 maprotiline | 7 | 436 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.40, 0.88] |

| 2.10 mianserin | 3 | 266 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.20, 0.57] |

| 2.11 minaprine | 3 | 702 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.39, 0.80] |

| 2.12 nomifensine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.13 nortriptyline | 4 | 226 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.30, 0.87] |

| 2.14 protriptyline | 1 | 100 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.60, 3.33] |

| 2.15 tianeptine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.16 trazodone | 3 | 428 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.87, 1.87] |

| 2.17 trimipramine | 1 | 41 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.11, 2.36] |

| 2.18 viloxazine | 1 | 41 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.27, 4.12] |

| 2.19 combination | 1 | 135 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.34, 1.86] |

| 2.20 fluoxetine | 1 | 41 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.06, 0.66] |

| 2.21 fluvoxamine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.22 sertraline | 3 | 468 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.60, 1.27] |

| 2.23 paroxetine | 6 | 1230 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.55, 0.87] |

| 2.24 citalopram | 2 | 416 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.28, 0.66] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 overall tolerability, Outcome 1 drop‐outs.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 overall tolerability, Outcome 2 patients with side‐effects.

Comparison 3. efficacy against TCA and related antidepressants.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 responders (int‐to‐treat) | 84 | 5376 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.99, 1.25] |

| 3.1 amineptine | 1 | 51 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.10, 1.04] |

| 3.2 amoxapine | 11 | 601 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.91, 1.81] |

| 3.3 clomipramine | 1 | 72 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.17, 1.05] |

| 3.4 desipramine | 3 | 146 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.62, 2.31] |

| 3.5 dothiepin | 5 | 230 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.31, 0.96] |

| 3.6 doxepin | 8 | 331 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.63, 1.59] |

| 3.7 imipramine | 9 | 578 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [1.20, 2.43] |

| 3.8 lofepramine | 6 | 376 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.49, 1.16] |

| 3.9 maprotiline | 12 | 683 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.65, 1.26] |

| 3.10 mianserin | 5 | 242 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.82, 2.29] |

| 3.11 minaprine | 2 | 204 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.67, 2.27] |

| 3.12 nomifensine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.13 nortriptyline | 4 | 197 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.77, 2.40] |

| 3.14 protriptyline | 1 | 100 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.40 [1.09, 5.26] |

| 3.15 tianeptine | 2 | 565 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.95, 2.06] |

| 3.16 trazodone | 8 | 752 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.72, 1.30] |

| 3.17 trimipramine | 1 | 26 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.11, 2.52] |

| 3.18 viloxazine | 3 | 117 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.84, 3.67] |

| 3.19 combination | 2 | 105 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.59 [0.69, 3.71] |

| 4 mean scores at endpoint | 29 | 1360 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.00, 0.35] |

| 4.1 amineptine | 2 | 89 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [‐2.78, 3.58] |

| 4.2 amoxapine | 1 | 38 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.54, 0.74] |

| 4.3 clomipramine | 1 | 72 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.24 [‐0.70, 0.23] |

| 4.4 desipramine | 2 | 82 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [‐0.01, 0.86] |

| 4.5 dothiepin | 2 | 93 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.39, 0.42] |

| 4.6 doxepin | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.7 imipramine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.8 lofepramine | 3 | 111 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.48, 0.47] |

| 4.9 maprotiline | 5 | 139 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [‐0.06, 0.71] |

| 4.10 mianserin | 3 | 77 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐0.20, 0.71] |

| 4.11 minaprine | 1 | 58 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.17 [‐0.34, 0.69] |

| 4.12 nomifensine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.13 nortriptyline | 2 | 65 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.14 [‐0.63, 0.35] |

| 4.14 protriptyline | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.15 tianeptine | 1 | 211 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [‐0.09, 0.45] |

| 4.16 trazodone | 4 | 243 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.01, 0.54] |

| 4.17 trimipramine | 1 | 34 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐0.42, 0.93] |

| 4.18 viloxazine | 1 | 48 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐0.19, 0.95] |

| 4.19 combination | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 efficacy against TCA and related antidepressants, Outcome 3 responders (int‐to‐treat).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 efficacy against TCA and related antidepressants, Outcome 4 mean scores at endpoint.

Comparison 4. tolerability against TCA and related antidepressants.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 drop‐outs | 128 | 9156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.96, 1.19] |

| 3.1 amineptine | 2 | 95 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.38, 3.39] |

| 3.2 amoxapine | 13 | 722 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.77, 1.54] |

| 3.3 clomipramine | 3 | 299 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.95, 2.41] |

| 3.4 desipramine | 4 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.28, 1.84] |

| 3.5 dothiepin | 8 | 396 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.32, 1.47] |

| 3.6 doxepin | 13 | 860 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.60, 1.17] |

| 3.7 imipramine | 6 | 349 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.71, 2.51] |

| 3.8 lofepramine | 8 | 470 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.55, 1.32] |

| 3.9 maprotiline | 18 | 1107 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.69, 1.35] |

| 3.10 mianserin | 12 | 787 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.91, 1.77] |

| 3.11 minaprine | 3 | 735 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.89, 1.90] |

| 3.12 nomifensine | 1 | 29 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.04, 12.15] |

| 3.13 nortriptyline | 8 | 467 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.56, 1.83] |

| 3.14 protriptyline | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.15 tianeptine | 3 | 694 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.89, 1.85] |

| 3.16 trazodone | 11 | 924 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.82, 1.51] |

| 3.17 trimipramine | 2 | 115 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.30, 1.97] |

| 3.18 viloxazine | 7 | 288 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.69, 2.55] |

| 3.19 combination | 6 | 663 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.55, 1.28] |

| 4 patients with side‐effects | 42 | 3310 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.58, 0.78] |

| 4.1 amineptine | 1 | 51 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.14, 1.49] |

| 4.2 amoxapine | 3 | 192 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.41, 1.44] |

| 4.3 clomipramine | 1 | 72 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.55, 3.47] |

| 4.4 desipramine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.5 dothiepin | 5 | 234 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.29, 0.88] |

| 4.6 doxepin | 4 | 168 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.39, 1.50] |

| 4.7 imipramine | 2 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.35, 1.50] |

| 4.8 lofepramine | 2 | 62 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.14, 1.08] |

| 4.9 maprotiline | 7 | 436 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.40, 0.88] |

| 4.10 mianserin | 3 | 266 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.20, 0.57] |

| 4.11 minaprine | 3 | 702 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.39, 0.80] |

| 4.12 nomifensine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.13 nortriptyline | 4 | 226 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.30, 0.87] |

| 4.14 protriptyline | 1 | 100 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.60, 3.33] |

| 4.15 tianeptine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.16 trazodone | 3 | 428 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.87, 1.87] |

| 4.17 trimipramine | 1 | 41 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.11, 2.36] |

| 4.18 viloxazine | 1 | 41 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.27, 4.12] |

| 4.19 combination | 1 | 135 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.34, 1.86] |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 tolerability against TCA and related antidepressants, Outcome 3 drop‐outs.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 tolerability against TCA and related antidepressants, Outcome 4 patients with side‐effects.

Comparison 5. efficacy against SSRIs.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 responders (int‐to‐treat) | 20 | 2046 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.95, 1.36] |

| 3.20 fluoxetine | 7 | 490 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.61, 1.29] |

| 3.21 fluvoxamine | 1 | 69 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [0.83, 5.46] |

| 3.22 sertraline | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.23 paroxetine | 10 | 1071 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.96, 1.58] |

| 3.24 citalopram | 2 | 416 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.76, 1.63] |

| 4 mean scores at endpoint | 24 | 2659 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [‐0.01, 0.19] |

| 4.20 fluoxetine | 11 | 859 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [‐0.01, 0.26] |

| 4.21 fluvoxamine | 2 | 83 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [‐0.41, 0.99] |

| 4.22 sertraline | 2 | 347 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.10, 0.32] |

| 4.23 paroxetine | 8 | 1326 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.13, 0.25] |

| 4.24 citalopram | 1 | 44 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.67, 0.52] |

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 efficacy against SSRIs, Outcome 3 responders (int‐to‐treat).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 efficacy against SSRIs, Outcome 4 mean scores at endpoint.

Comparison 6. tolerability against SSRIs.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 drop‐outs | 46 | 5770 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.75, 0.95] |

| 1.20 fluoxetine | 17 | 1290 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.60, 1.01] |

| 1.21 fluvoxamine | 3 | 158 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.39, 1.83] |

| 1.22 sertraline | 8 | 1579 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.78, 1.21] |

| 1.23 paroxetine | 15 | 2283 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.69, 1.01] |

| 1.24 citalopram | 3 | 460 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.42, 0.96] |

| 2 patients with side‐effects | 12 | 2155 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.55, 0.78] |

| 2.20 fluoxetine | 1 | 41 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.06, 0.66] |

| 2.21 fluvoxamine | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.22 sertraline | 3 | 468 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.60, 1.27] |

| 2.23 paroxetine | 6 | 1230 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.55, 0.87] |

| 2.24 citalopram | 2 | 416 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.28, 0.66] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 tolerability against SSRIs, Outcome 1 drop‐outs.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 tolerability against SSRIs, Outcome 2 patients with side‐effects.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aberg 1977.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: presence of depression, HMD 25+ and Beck 12+ Age: 49 mean Country: Sweden Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | amoxapine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 22 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Altamura 1989.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 5 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 17+ Age: 60‐83 Country: Italy Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | mianserin versus trazodone versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint responders drop‐outs | |

| Notes | quality rating: 17 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Altamura 1989a.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 5 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 18+ Age: 65+ Country: Italy Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | fluoxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Amin 1973.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 8 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients with depression Age: 19‐62 Country: Canada Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | maprotiline versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 17 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Amin 1978.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 3 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: endogenous and neurotic depression Age: 24‐56 Country: Canada Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | desipramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 13 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Anderson 1972.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: anxiety and mild depression, 25+ on a symptom checklist Age: not clear Country: UK Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | nortriptyline+fluphenazine versus amitriptyline+perphenazine | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Anton 1990.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression with psychotic features | |

| Interventions | amoxapine versus amitriptyline+perphenazine | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint drop‐outs | |

| Notes | quality rating: 22 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ather 1985.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: primary diagnosis of depression, HMD 14+ Age: 59+ Country: UK Setting: in and outpatients | |

| Interventions | trazodone versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders drop‐outs patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 22 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Balestrieri 1971.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 3 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients suitable for antidepressant treatment Age: 52.9 mean Country: Italy Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | imipramine versus maprotiline versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | drop‐outs patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bascara 1989.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III R major depression, HMD 18+ Age: 33 average Country: Philipines Setting: not clear | |

| Interventions | paroxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Battegay 1985.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 7 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III endogenous and reactive depression, HMD 20+ Age: 18‐60 Country: Switzerland Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | paroxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 19 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Beaini 1980.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: primary depressive illness Age: less than 75 Country: UK Setting: not clear | |

| Interventions | imipramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders | |

| Notes | quality rating: 13 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Beckmann 1975.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: Feighner primary affective disorder, unipolar Age: 20‐72 Country: US Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | imipramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders drop‐outs | |

| Notes | quality rating: 9 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bennie 1976.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients with anxiety‐depressive states Age: 18‐65 Country: UK Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | nortriptyline/fluphenazine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bersani 1994.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 8 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III R major depression, HMD 22+ Age: 21‐69 Country: Italy Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | sertraline versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 15 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bianchi 1971.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 5 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: Slater and Roth criteria of neurotic and endogenous depression Age: 50 mean Country: Australia Setting: in and outpatients | |

| Interventions | doxepin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 15 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bignamini 1992.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 18+ Age: 18‐70 Country: Italy Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | paroxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 19 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Blacker 1988.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 17+ Age: 18‐65 Country: UK Setting: family practice | |

| Interventions | dothiepin versus mianserin versus trazodone versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint (trazodone‐amitriptyline) drop‐outs (combination‐amitriptyline) | |

| Notes | quality rating: 23 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Botros 1989.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: primary depressive illness, HMD 17+ Age: 18‐80 Country: UK Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | trazodone versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 18 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Browne 1969.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depressive illness Age: 40‐69 Country: UK Setting: in and outpatients | |

| Interventions | imipramine versus amitriptyline+perphenazine | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 scale not validated | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Burke 1967.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depressive syndrome requiring hospitalisation Age: 20+ Country: Australia Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | trimipramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Burrows 1980.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: moderate to severe depression requiring hospitalisation Age: 16+ Country: Australia Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | amoxapine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 17 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Burt 1962.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: female hospitalised patients with "primary affective alteration" Age: 30‐70 Country: Australia Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | imipramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders | |

| Notes | quality rating: 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Byrne 1989.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: endogenous depression, HMD 23+ Age: 18‐65 Country: Belgium, France, UK Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | paroxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 17 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Carman 1991.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 17+ Age: 18+ Country: US Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | mianserin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Carney 1984.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depression, HMD 14+ Age: not clear Country: Ireland Setting: in and outpatients | |

| Interventions | trazodone versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders drop‐outs | |

| Notes | quality rating: 13 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Chouinard 1985.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: RDC major depressive disorder, HMD 20+, Raskin greater than Covi Age: 24‐59 Country: Canada Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | fluoxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Christiansen 1996.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 8 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients with depression, HMD 15+ Age: 18‐65 Country: Denmark Setting: family practice | |

| Interventions | paroxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 21 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Click 1982.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depressive patients, HMD 25+, Raskin 8+, Zung 50+ Age: 18‐60 Country: US Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | amoxapine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 15 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cohn 1990.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 8 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III R major depressive episode, HMD 18+, Raskin greater than Covi Age: 65+ Country: US Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | sertraline versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cournoyer 1987.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 3 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III and RDC criteria major depressive episode, unipolar and bipolar, HMD 20+ Age: 26‐72 Country: Canada Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | trimipramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 18 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dahl 1981.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depressive disorder, 'masked depression' Age: 20‐68 Country: Sweden Setting: family practice | |

| Interventions | dothiepin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Daly 1979.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 3 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depression Age: 18‐65 Country: Ireland Setting: inpatients | |

| Interventions | mianserin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 15 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

De La Barquera 1998.

| Methods | Double‐blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM‐III‐R major depressive disorder, HMD‐21 18+ Age: 18‐65 Country: Mexico Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | fluoxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 22 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

De Ronchi 1998.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 10 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III R major depressive disorder, HMD 16+ Age: 60+ Country: Italy Setting: inpatients and outpatients | |

| Interventions | fluoxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 25 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Deering 1974.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: 'change of mood which exceeded the normal variation in mood by virtue of its severity and duration' Age: 40 average Country: UK Setting: family practice | |

| Interventions | dothiepin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 19 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Del Zompo 1990.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 16+ Age: 47 mean Country: Italy Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | minaprine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 23 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Delaunay 1978.

| Methods | Double blind: not clear RCT, allocation concealment may be inadequate Active treatment: 3 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients who need antidepressant treatment Age: 18‐75 Country:France Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | dosulepine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Dell 1977.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 3 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: depression of sufficient severity as to warrant treatment with antidepressant drugs Age: 45 average Setting: family practice | |

| Interventions | maprotiline versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 19 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Demyttenaere 1998.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 9 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III R major depression, unipolar, HMD 15+ Age: 18‐60 Country: Belgium Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | fluoxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Donlon 1981.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: RDC endogenous depression, HMD 25+, Raskin 8+, Zung 50+ Age: 18‐60 Country: US Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | amoxapine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 19 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Doongaji 1993.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, HMD 20+, CGI 4+ Age: 20‐65 Country: India Setting: in and outpatients | |

| Interventions | lofepramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 24 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dorman 1980.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 5 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients whose condition was judged appropriate for antidepressant treatment Age: 18‐60 Country: UK Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | dothiepin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | mean scores at endpoint dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 21 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dorn 1980.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients with depression Age: 65+ Country: Germany Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | lofepramine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 17 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Edwards 1996.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM IIIR depression, HMD 17+ Age: 18‐70 Country: UK, Ireland Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | minaprine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 32 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Fawcett 1989.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: DSM III major depression, unipolar, HMD 20+ Age: 18+ Country: US Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | fluoxetine versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders mean score at endpoint dropouts | |

| Notes | quality rating: 21 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Feighner 1983.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: Feighner and RDC criteria for major depressive disorder, HMD 19+ Age: 40 average Country: US Setting: outpatients | |

| Interventions | mianserin versus amitriptyline | |

| Outcomes | responders dropouts patients with side‐effects | |

| Notes | quality rating: 18 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ferrari 1987.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Active treatment: 4 weeks | |