Abstract

Background

Smallpox was eradicated by 1980, but its possible use as a bioweapon has rekindled interest in the development of protective vaccines. Therefore, stockpiled calf lymph‐derived vaccines and recently developed cell‐cultured vaccines have been investigated to contribute information to smallpox emergency response plans, while newer (non‐replication competent) vaccines are developed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of smallpox vaccines in preventing the disease, in inducing immunity, and in regard to adverse events.

Search methods

In December 2006, we searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 4), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, and Current Controlled Trials, and handsearched Index Medicus. We also searched three databases of vaccine safety in December 2005.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials of smallpox vaccines versus placebo, other smallpox or non‐smallpox vaccine, no intervention, or different dose of the same vaccine in people receiving smallpox vaccination irrespective of age.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We combined dichotomous data using risk ratio with a random‐effects model.

Main results

Ten trials involving 2412 participants were included. The vaccines investigated were calf‐lymph derived first‐generation vaccines (Dryvax, APVS, Lancy‐vaxina, Lister), and cell‐cultured second‐generation vaccines (ACAM, CCSV). Vaccines were investigated in different dilutions. All undiluted vaccines induced a reaction in 95% of people vaccinated in terms of pustule and immunogenicity. Also 1:10 dilutions were fully efficient when the starting concentration was defined. Serious adverse events were reported in 1% to 2% of the volunteers. Fever was observed in 11% to 22% of participants, and headache in roughly half of the participants. Fever was less frequent when new vaccines were administered, but rates of headache were similar in new and old vaccines.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence shows that stockpiled vaccines have maintained their immunogenicity and new cell‐cultured vaccines are similar to stockpiled vaccines in terms of vaccination success rate and immunogenicity. First‐ and second‐generation vaccines diluted to at least 1:10 are as effective as undiluted vaccine in terms of clinical success rate and immunogenicity. Dilution did not reduce the frequency of adverse events. Success rate and immunogenicity were similar in naive and previously vaccinated persons, but there were fewer adverse events in previously vaccinated persons. The rate of adverse events found in this review reveals the need for further development and improvement of smallpox vaccines.

15 April 2019

No update planned

Other

This is not a current research question.

Plain language summary

Vaccines for preventing smallpox

Smallpox is an acute viral infection unique to humans. A worldwide smallpox campaign (including mass vaccination, patient isolation, and surveillance) contributed to the eradication of the disease by 1980. However, there is growing concern that the virus could now be used as a biological weapon. Smallpox spreads from one person to another by infected saliva droplets. The incubation period is 7 to 17 days. The symptoms begin with severe headache, backache, and fever up to 40 °C, all beginning abruptly. Then a rash appears on the face and spreads, the spots become watery blisters containing pus that form scabs and leave pitted scars when they fall off. The infected person is contagious until the last smallpox scab has fallen off, although most of the transmission occurs in the first week. Most people with smallpox recover, but some do die and the risk depends on the strain of virus. The early vaccines were effective, but they had a number of adverse effects, including headache, fever, and reaction at the infection site, and also the possibility of death. New vaccines continue to be developed. The review identified 10 trials that involved 2412 participants. Overall, the quality of the trials was not high but the review showed that stockpiles of the vaccines maintained their effectiveness even when diluted. New second‐generation vaccines seemed to be effective but still have adverse events. There were too few participants overall to be able to assess rare outcomes. Further research is needed, particularly on the third‐generation vaccines.

Background

Smallpox is an acute viral disease that is unique to humans and is caused by the variola virus (an orthopoxvirus). The virus has two major variants named Variola major and Variola minor. After a worldwide smallpox eradication campaign comprising a broad array of measures such as mass vaccination, containment (patient isolation), and surveillance, the last case of endemic smallpox occurred in Somalia in 1977, and eradication of the disease was declared in 1980 (WHO 1980). However, there is growing concern that stores of variola virus may have resided in laboratories other than the two World Health Organization (WHO) designated repositories (Henderson 2001). The virus is one of several widely known microorganisms that could be used as a biological weapon with great potential for devastation (Henderson 1999b).

Smallpox and how it spreads

Smallpox is spread from one person to another by infected saliva droplets. There are no subclinical carriers (infected persons without symptoms) and no non‐human hosts. Generally, direct and rather prolonged face‐to‐face contact is required, but also aerosols, infected body fluids, or contaminated objects such as bedding or clothing may transmit the disease. The incubation period is 7 to 17 days (mean, 10 to 12 days) and is followed by a prodromal phase of two or three days, which is characterized by severe headache, backache, and fever up to 40 °C, all beginning abruptly. Subsequently, a papular rash develops over the face and spreads to the extremities. The rash soon becomes vesicular (watery blisters) and later, pustular (blisters containing pus). The patient remains febrile throughout the evolution of the rash and experiences considerable pain as the pustules grow and expand. Gradually scabs form, which eventually separate, leaving pitted scars. The infected person is contagious until the last smallpox scab has fallen off although the vast majority of transmission occurs in the first week of illness. The majority of people with smallpox recover, but death may occur in 30% to 40% of cases during the second week in those who contracted Variola major. The case‐fatality rate for Variola minor is 1% (Fenner 1988; Henderson 1999a).

Treatment and vaccination

There is no specific treatment for smallpox disease, and vaccination is the only prevention measure besides containment. In 1796, Edward Jenner discovered that humans inoculated with cowpox became immune to smallpox. Since then the inoculum against smallpox has been distributed in a liquid form of often variable quality. The virus used in most smallpox vaccines is a live‐attenuated virus (less virulent, causing less disease) of the Poxviridae family known as vaccinia virus, which is closely related to the variola virus. The vaccinia virus is derived from cowpox or possibly horsepox. Many different strains and application methods of vaccinia virus have been employed. From the 1920s onwards, some laboratories have produced air‐dried or freeze‐dried vaccines. After 1971, the freeze‐dried vaccine was the only one used by any country engaged in a national smallpox eradication programme, with two strains in particular ('Lister' and 'New York City Board of Health' (NYCBOH)) being recommended by the WHO for administration (Fenner 1988). Also the application methods were standardized and two new vaccination techniques were mainly used: intradermal inoculation by the jet injector and multiple‐puncture inoculation with the bifurcated needle. Vaccination success rates (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate) were reported to be more than 90% when the bifurcated needle was used (Karchmer 1971; Vaughan 1972; Vaughan 1973).

Smallpox eradication

The progressive decrease of the disease that followed introduction of Jenner's vaccine in various European countries during the 19th century appeared to be the most persuasive evidence that vaccination was effective in preventing smallpox. However, in 1967, when the WHO started the intensified smallpox eradication programme, some 10 to 15 million cases were still occurring annually in more than 30 endemic countries worldwide (Fenner 1988). A decade later, smallpox had totally disappeared. This was mainly attributed to the vaccine, but, in hindsight, one might ask to what extent the three main constituents of the programme (vaccination, containment, and surveillance) as well as other factors such as better life quality and hygiene contributed to the elimination of the disease (Hopkins 1988).

Smallpox vaccines in the biowarfare scenario

Concern that remaining variola virus, which can be grown in large quantities and aerosolized, might be used as a biological weapon has led to proposals that smallpox vaccination be offered to some, if not all, of the population in various countries (Bicknell 2002). There are two major concerns if smallpox vaccine is needed for protection against biowarfare or bioterrorism: first the availability of enough vaccine, and secondly the rate of adverse events that might occur. To address the first issue, several studies were initiated to find out if the vaccine doses available could be increased by diluting the vaccine that had been stored since the end of the eradication campaign (Frey 2002a; Frey 2002b; Frey 2003; Rock 2004; Talbot 2004; Kim 2005; Hsieh 2006), and these studies are reviewed here. Adverse events are discussed in the next two sections and results from included trials are presented in this review.

Adverse effects of the vaccine in the eradication era

Adverse effects caused by smallpox vaccination range from mild and self‐limited to severe and life‐threatening. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance guidelines recommend that the following be reported after smallpox vaccination: superinfection of the vaccination site or regional lymph nodes; inadvertent autoinoculation; contact transmission; ocular vaccinia; generalized vaccinia; eczema vaccinatum; progressive vaccinia; erythema multiforme major or Stevens‐Johnson Syndrome; fetal vaccinia; postvaccinial central nervous system disease; myo/pericarditis; and dilated cardiomyopathy (MMWR 2006).

An early trial reported fever (> 38.3 °C) in 6% (38/632) of vaccinees (Karchmer 1971). Serious adverse events (including death) that followed smallpox vaccination caused considerable public anxiety during the eradication period. The rate of all serious adverse events was estimated to be 40 to 400 cases per million vaccinations, with wide variations according to strains used, age groups, and pre‐immunization status. Generalized vaccinia ranged from 1 to 70/106 vaccinations and eczema vaccinatum ranged from 8 to 80/106 vaccinations. Progressive vaccinia occurred in 1/106 vaccinations, and post‐vaccination encephalitis or encephalopathy occurred in 2 to 1200/106 vaccinations. One in one million vaccinated persons died (Lane 1970a; Lane 1970b). A systematic review of risks from smallpox vaccination between 1963 and 1968 in the USA reported that 29% (11/38) of patients with post‐vaccinial encephalitis and 15% (2/13) of patients with vaccinia necrosum died (Aragon 2003).

Adverse events of the vaccine in the post‐eradication era

In December 2002, a programme to vaccinate up to 500,000 US military personnel was launched (Grabenstein 2003), and smallpox vaccination of civilian volunteer healthcare workers began on 24 January 2003 (MMWR 2003). In February 2003, the US Food and Drug Administration temporarily suspended all vaccinia trials due to adverse events noted in these civilian and military vaccination campaigns (MMWR 2003). After completion of the military and healthcare worker trials in May 2003 and June 2003, respectively, myopericarditis was found to occur at a statistically elevated rate of up to 7.5 times higher than in the non‐vaccinated population (Arness 2004). On the basis of historical experience, cardiac complications such as myocarditis and pericarditis were not expected with use of the US‐licensed strain of smallpox vaccine. A mathematical model (hierarchical Bayesian approach) that included various strains used during the eradication campaign estimated the death toll during a present‐day mass vaccination in Germany to range from 46.2 to 1381 deaths per million inhabitants (Kretschmar 2006). One hundred and twenty‐five people would be expected to die of complications after vaccination of the entire USA population of 282 million people with the NYCBOH strain only (Lane 2003). Indeed, more serious adverse events could reasonably be expected with resumption of widespread, indiscriminate vaccination given the increased prevalence of disease patterns with impaired immune responses, such as atopic dermatitis and immune deficiency syndromes. Also, as the vaccinia virus may be transmitted accidentally from vaccinees, it could also cause adverse reactions in non‐vaccinated individuals (Neff 2002).

Problems of research in smallpox vaccines

Public discussion of the reintroduction of smallpox mass vaccination has become highly controversial and is charged with bias both for and against this intervention. Vaccines still in use will be replaced soon by a new generation of smallpox vaccines that are expected to reduce adverse effects and increase protection (Drexler 2003). Attenuation (lessening of virulence) of viral vaccines may be achieved by multiple passages of the virus through unusual host cells, by unusual environmental growth conditions, or by recombinant DNA technology (gene engineering). However, immunological surrogate markers that could provide information about the potential protective efficacy of smallpox vaccines do not exist in the absence of a good animal model and, even if the disease was still present, challenge studies or field trials would be considered unethical. In this situation randomized controlled trials investigating immunogenic efficacy and adverse events of smallpox vaccines are the only way to investigate new vaccines.

Types of smallpox vaccines

Smallpox vaccines are generally called first generation if they are old vaccines prepared on the skin of live animals, usually containing viable bacteria, and usually not able to guarantee that adventitious animal viruses are not present in the vaccine. Second‐generation vaccines are those that use the old seed viruses (Lister, NYCBOH, etc), but grow the vaccine in modern sterile media, ensuring they are free of bacteria and adventitious animal viruses. Third‐generation are strains that have been in some way attenuated so that at least in theory or in animal models they are less pathogenic or reactogenic than first‐ and second‐generation vaccines. The trials reviewed here are of dilutions of first‐ and second‐generation vaccines, or are comparison of second‐generation vaccines with first‐generation vaccines generally accepted as being able to prevent smallpox. These latter trials are usually called trials of non‐inferiority because they show that the newer vaccines behave in the same way as the older vaccines despite our lack of a proven surrogate index of efficacy. There are several third‐generation vaccines in early stages of development, but in the absence of randomized clinical human trials within the time period of this literature research they are not reviewed here and will be included in a future update of the review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of smallpox vaccines in preventing the disease, in inducing immunity, and in regard to adverse events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

People of any age.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Smallpox vaccine of any type and given by any route.

Control

Placebo, other smallpox vaccine, other (non‐smallpox) vaccine, no intervention, or different dose of the same vaccine.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

Death from smallpox.

Cases of smallpox.

Secondary outcomes

Vaccination success rates (pustule at vaccination site,'take' rate).

Immunological outcomes (parameters of humoral and cell‐mediated immunity, duration of the immune response).

Adverse events

Serious adverse events (fatal, life threatening, or requiring hospitalization).

Other adverse events associated with the vaccine (referring to the case definitions of the Brighton Collaboration; Brighton 2004).

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

We searched the following bibliographic databases using the search terms and strategy described in Appendix 1: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (December 2006); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library (2006, Issue 4); MEDLINE (1966 to December 2006); EMBASE (1974 to December 2006); and LILACS (1982 to December 2006). We also searched the Current Controlled Trials website (accessed December 2006), using the search terms 'smallpox AND (vaccin* OR immuni*)'. We also handsearched Index Medicus (1920 to 1966).

We searched three databases of vaccine safety using the search terms 'smallpox AND (vaccin* OR immuni*)': The Brighton Collaboration (www.brightoncollaboration.org; December 2005); Institute of Vaccine Safety, Bloomberg School of Public Health (www.vaccinesafety.edu; December 2005); and Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (vaers.hhs.gov/; December 2005).

We checked the reference lists of all studies identified by the above methods.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We, Wolfram Metzger (WM) and Benjamin Mordmueller (BM), independently screened the titles and abstracts of the studies identified by the search strategy for potentially relevant studies. We obtained the full reports for those considered potentially relevant (and for those where there was uncertainty) and applied independently an eligibility form based on the inclusion criteria. We resolved any differences in opinion through discussion. We gave the reason for excluding any of the potentially relevant studies in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. Trial reports were scrutinized to ensure that multiple publications from the same trial were included only once. Trial investigators were contacted for clarification if trial eligibility was unclear.

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data using a standardized data extraction form. WM entered the data into Review Manager 5, and BM cross checked the data. We aimed to extract data according to the intention‐to‐treat principle (all randomized participants should be analysed in the groups to which they were originally assigned). If there was discrepancy in the number randomized and the numbers analysed in each treatment group, we reported this information. For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of participants experiencing the event and the number analysed in each treatment group. We resolved disagreement through discussion, and, if necessary, involved a statistician or an Editor of the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We independently assessed the risk of bias in the included trials using the full‐text article and a validity form. We classed generation of allocation and allocation concealment to be adequate, inadequate, or unclear according to Jüni 2001. We considered the inclusion of participants in the analysis to be adequate if greater than 80% and inadequate if 80% or less. We classified blinding as open (all parties are aware of treatment), single (participant or care provider or assessor is aware of the treatment given), or double (trial uses placebo or a double‐dummy technique such that neither the participant nor care provider or assessor know which treatment is given), and reported who specifically was blinded. We attempted to contact the authors if this information was not specified or if it was unclear. We resolved disagreement through discussion and displayed the results of the quality assessment in a table.

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we analysed data using Review Manager 5. All included participants were included in the analysis ('intention to treat'). We stratified the analysis by vaccine dilution, new generation versus original vaccine (Dryvax), and non‐naive versus naive participants. We assessed the homogeneity of effect sizes between studies by visually examining the forest plots and by using the chi‐squared test for heterogeneity (10% level of statistical significance) and the I2 test (50% level). We assessed homogeneity of participants, interventions, and outcomes before deciding to combine data. We combined dichotomous data (such as adverse events) using risk ratio and the random‐effects model, and presented the results with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Description of studies

Identification of studies

Of the 60 potentially relevant studies identified with the search strategy, 10 trials met the inclusion criteria (see 'Characteristics of included studies') and 50 were excluded (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies'). We also identified 33 registered ongoing (or newly completed) studies (see 'Characteristics of ongoing studies').

Time‐frame and participants

The included trials were carried out from the year 2000 onward and included 2412 participants. Six investigated young healthy volunteers who had never been vaccinated before (naive), and four included older persons who had been vaccinated before (Frey 2003; Greenberg 2005; Kim 2005; Hsieh 2006).

Vaccines

Seven trials analysed different dilutions of vaccines that were produced before smallpox was eradicated and had been stored since then (Frey 2002a; Frey 2002b; Frey 2003; Rock 2004; Talbot 2004; Kim 2005; Hsieh 2006). Three trials compared safety and immunogenicity of new cell‐cultured vaccines with the stored, calf lymph‐derived vaccine from Dryvax/Wyeth (Weltzin 2003; Artenstein 2005; Greenberg 2005). Four trials included investigations to find out if naive participants differ from non‐naive persons in regard to reaction profile and adverse events (Frey 2003; Greenberg 2005; Kim 2005; Hsieh 2006). Six different types of vaccine were investigated (see Appendix 2).

Outcomes

The trials did not investigate the review's primary outcome measures − protective efficacy with regard to death or smallpox cases. All explored efficacy in terms of a major reaction to the vaccine (pustule at vaccination site, take rate) and immunogenicity in terms of humoral and/or cellular immune responses to the vaccines (neutralizing antibodies and/or cytokines).

Risk of bias in included studies

The trials differed in methodological quality (details provided in the 'Characteristics of included studies'). Only two trials mentioned how the allocation sequence was generated (Talbot 2004; Greenberg 2005), and none described allocation concealment. None of the trials was named quasi‐randomized. Six trials blinded participants and investigators (Frey 2002b; Weltzin 2003; Rock 2004; Talbot 2004; Artenstein 2005; Greenberg 2005), while four trials blinded only the participants (Frey 2002a; Frey 2003; Kim 2005; Hsieh 2006). All trials included an adequate (> 80%) of participants in the analysis.

Effects of interventions

Death from smallpox and cases of smallpox

None of the trials reported on these outcome measures.

Vaccination success rates

Success (major reaction) of vaccination was measured as the presence of a vesicle seven to nine days after scarification.

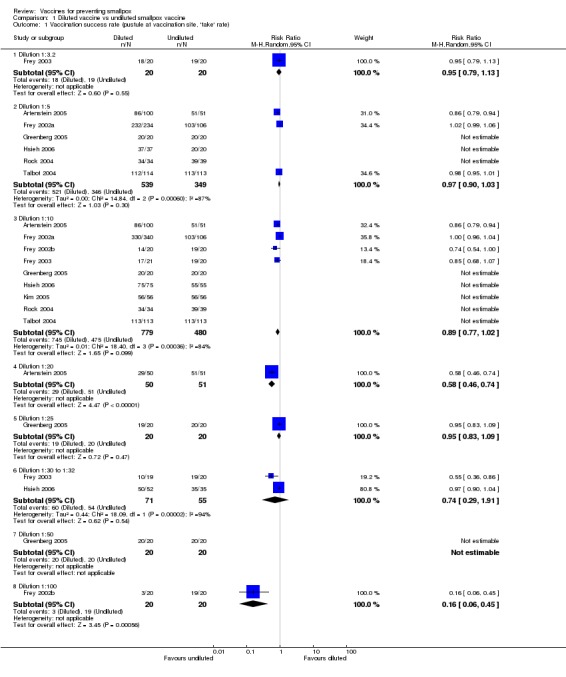

Diluted versus undiluted vaccines

Nine trials that compared dilutions of vaccines measured this outcome (Analysis 1.1). The undiluted vaccines generated success in 95% or more of the volunteers. Dilution of up to 1:10 of the stocked calf lymph‐derived vaccines (Dryvax, APVS, Lancy‐vaxina, and Lister) did not diminish success rates overall. However, dilutions of Dryvax vaccine (1:10 and 1:100) reduced the success rates in two trials (Frey 2002b; Frey 2003). This was probably the result of different start concentrations in the original undiluted vaccines. Consequently, it was suggested that Dryvax can be diluted to a titre of 107 plaque‐forming units per millilitre (Frey 2002a). Dilutions of new cell‐cultured vaccines maintained full success rates in all but the 1:20 dilution of one trial, Artenstein 2005 (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.93; 151 participants).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine, Outcome 1 Vaccination success rate (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate).

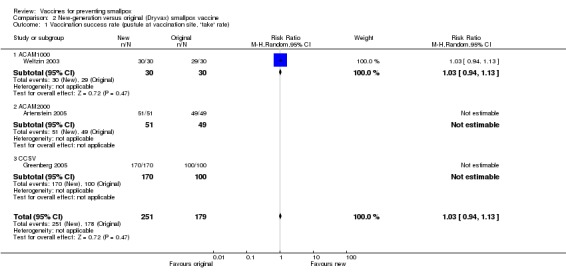

New versus old vaccines

No failures were seen in trials testing the new cell‐cultured vaccines (ACAM1000, ACAM2000, and CCSV) compared with the old calf lymph‐derived control vaccine (Dryvax) in three trials (with 430 participants) (Analysis 2.1) (Weltzin 2003; Artenstein 2005; Greenberg 2005).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine, Outcome 1 Vaccination success rate (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate).

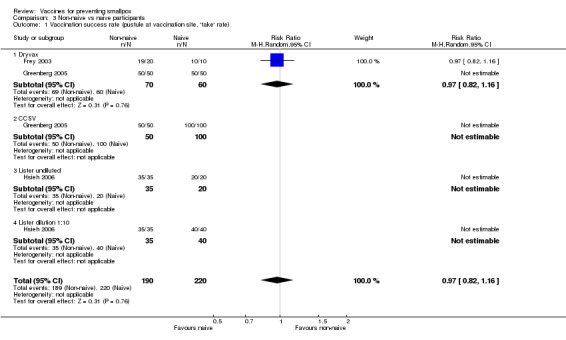

Naive versus non‐naive participants

Three trials (with 410 participants) made this comparison and found no failures between the groups (Analysis 3.1) (Frey 2003; Greenberg 2005; Hsieh 2006).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐naive vs naive participants, Outcome 1 Vaccination success rate (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate).

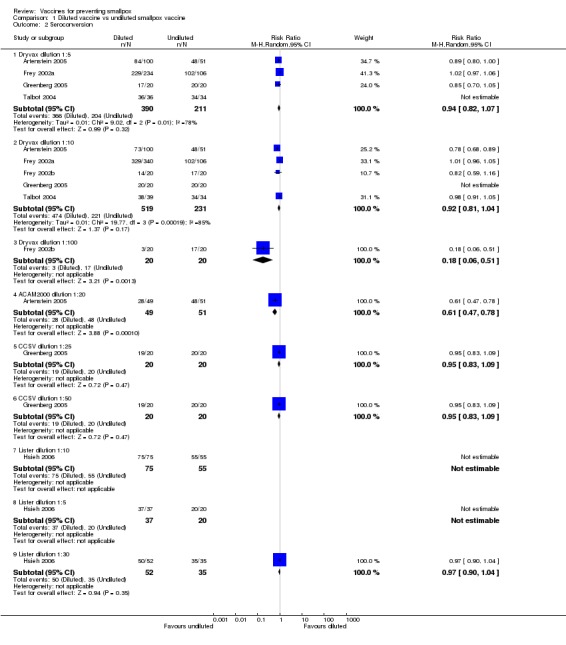

Immunological outcomes

Humoral responses

Humoral responses paralleled successful vaccination. Nearly all volunteers who showed a vesicle seroconverted in regard to antibodies neutralizing the smallpox vaccine virus (the definition of seroconversion in each trial is given in the 'Characteristics of included studies'). Consequently, similar results to the success rates were shown in the comparisons of diluted versus undiluted vaccines (6 trials, Analysis 1.2), new versus old vaccines (3 trials, Analysis 2.2), and naive versus non‐naive participants (2 trials, Analysis 3.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine, Outcome 2 Seroconversion.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine, Outcome 2 Seroconversion.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐naive vs naive participants, Outcome 2 Seroconversion.

Cellular responses

Cellular responses were investigated in five trials. Similar to humoral responses, almost all participants with vesicle formation had vaccinia virus‐specific T‐cell responses, increased numbers of interferon‐gamma‐producing T‐cells, and lymphocyte proliferation (Frey 2002b; Weltzin 2003; Greenberg 2005; Hsieh 2006). One trial reported that participants who did not report an adverse event presented different cytokine profiles from those who did report an adverse event (Rock 2004).

Adverse events

Serious adverse events

All 10 trials collected data on serious adverse events, but only three trials reported their occurrence: Frey 2002a (12/680 participants (2%), dilution comparison); Talbot 2004 (4/340 participants (1%), dilution comparison); and Artenstein 2005 (1/304 participants for ACAM2000 vaccine (0.03%), versus none for Dryvax vaccine). Of the 12 participants in Frey 2002a, the trialists classified three with serious adverse events possibly (1) or definitely (2) related to the vaccine, and probably unrelated (2) or unrelated (7) to the vaccine. Comparisons of vaccine types and dilutions did not show significant differences because the number of these events was low. The reported serious adverse events were high fever (1), severe headache and nausea (1), large erythema (1), nausea/dehydration (1), orthostatic dizziness (1), facial nerve dispalsy (1), colitis flare (1), and myopericarditis (1). Retrospectively, and after the addition of cardiac screening questions, cardiac symptoms or chest pain were reported in 1% (5/340) of participants (Talbot 2004), and 3% (11/353) of participants (ACAM2000: 8/304 (3%), Dryvax 3/49 (6%)) (Artenstein 2005).

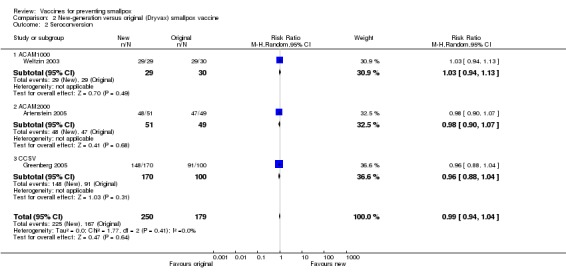

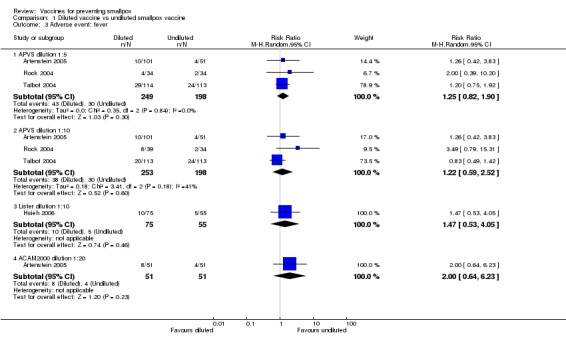

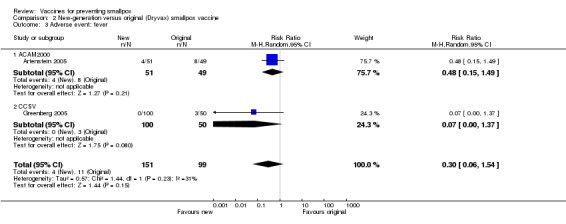

Fever

In all trials, changes from baseline body temperature were seen with varying frequency, and as the trials differed in their definition of fever, we cannot make a conclusive statement. The reported fever frequencies were 21.5% (73/340) (Talbot 2004), 8.9% (59/665) (Frey 2002a), and 10.5% (32/304) (Artenstein 2005). Fever was not significantly reduced by vaccine dilution (4 trials, Analysis 1.3) or use of new vaccines (2 trials, Analysis 2.3). Fever was less common in non‐naive participants than in naive participants (2 trials, Analysis 3.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine, Outcome 3 Adverse event: fever.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine, Outcome 3 Adverse event: fever.

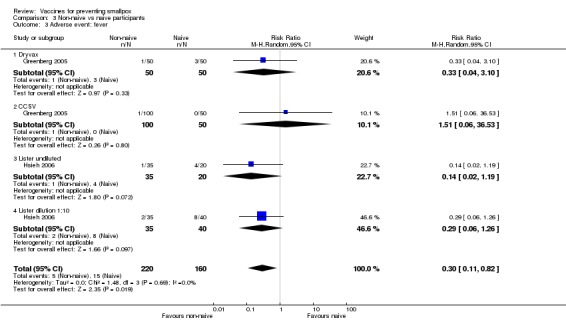

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐naive vs naive participants, Outcome 3 Adverse event: fever.

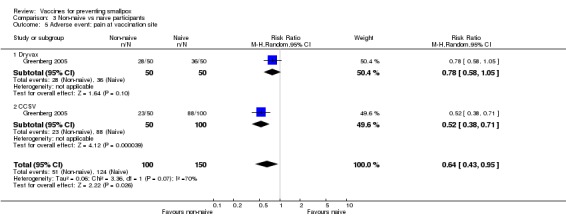

Headache

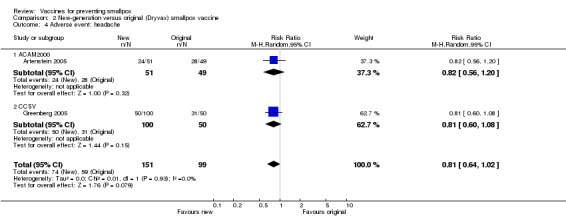

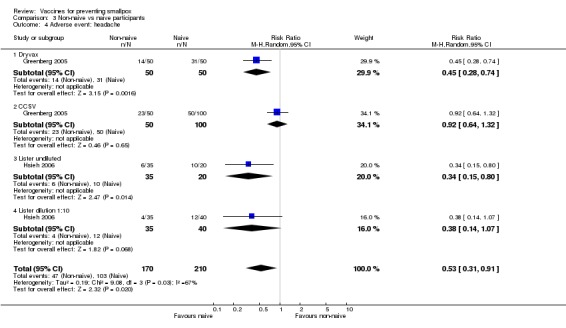

Roughly half of the volunteers in five trials complained of headaches (Frey 2002a; Talbot 2004; Artenstein 2005; Greenberg 2005; Kim 2005), whereas, surprisingly, no complaint of headache was reported in three other trials (Frey 2002b; Frey 2003; Rock 2004). One trial stated that "all 60 subjects experienced at least one adverse event" (Weltzin 2003), but it was not specified if headache was amongst them. Headache was not reduced significantly by vaccine dilution (4 trials, Analysis 1.4). New vaccines performed similar to Dryvax in regard to headache (2 trials, Analysis 2.4). Interestingly, non‐naive participants had significantly less headache when revaccinated than first‐time vaccinated participants (2 trials, Analysis 3.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine, Outcome 4 Adverse event: headache.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine, Outcome 4 Adverse event: headache.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐naive vs naive participants, Outcome 4 Adverse event: headache.

Local reactions

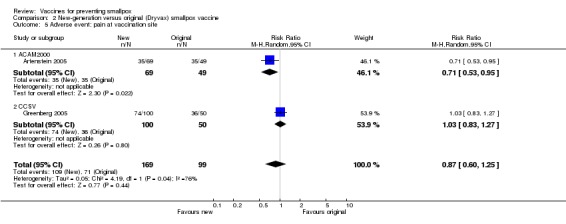

Pain at vaccination site

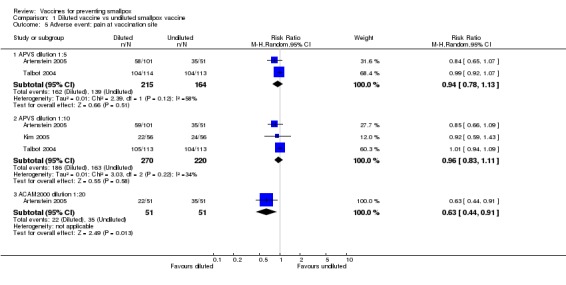

The different smallpox vaccines caused pain at the vaccination site in 68% (1208/1775) of the volunteers with studies ranging from 7% to 92%. The 1:20 dilution reduced pain, but only in one of the three dilution trials reporting on this outcome (Analysis 1.5). Overall, there was no difference between new and old vaccines (2 trials, Analysis 2.5), while naive participants reported more pain at the vaccination site than non‐naive participants (1 trial, Analysis 3.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine, Outcome 5 Adverse event: pain at vaccination site.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine, Outcome 5 Adverse event: pain at vaccination site.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐naive vs naive participants, Outcome 5 Adverse event: pain at vaccination site.

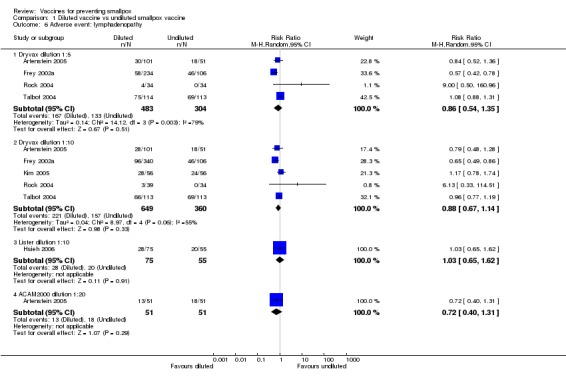

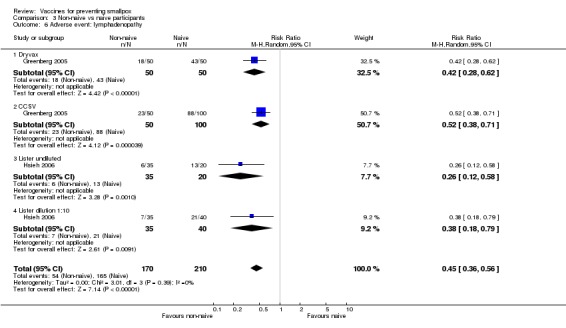

Lymphadenopathy

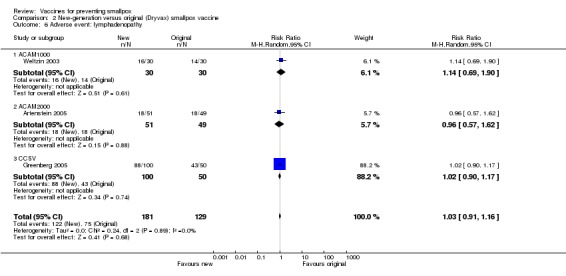

Lymphadenopathy was not mentioned in one trial (Frey 2002b), but volunteers in all other trials showed signs of lymphadenopathy, with percentages ranging from 7% to 88%. The 1:5 and 1:10 dilutions in Frey 2002a, one of the six dilution trials reporting on this outcome, reduced lymphadenopathy (Analysis 1.6), but no difference was shown between new and old vaccines (3 trials, Analysis 1.6). More naive participants presented with lymphadenopathy than non‐naive participants (2 trials, Analysis 3.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine, Outcome 6 Adverse event: lymphadenopathy.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐naive vs naive participants, Outcome 6 Adverse event: lymphadenopathy.

Other

Three trials (with 1355 participants) reported the missing of scheduled duties or recreational activities and sleeping disorders in 36% (Frey 2002a), 25% (Talbot 2004), and 12% (Greenberg 2005) of participants. Dilution subgroups were not compared in regard to this parameter, and new and old vaccines did not differ significantly in regard to this parameter. Non‐naive participants missed scheduled activities significantly less than naive participants (Greenberg 2005).

Discussion

This review's objective was to assess the effects of smallpox vaccines in preventing the disease, in inducing immunity, and in regards to adverse events. It was not surprising that we were not able to find randomized controlled trials reporting the efficacy of smallpox vaccines in terms of disease prevention. Such trials were not a must in the pre‐eradication era, and, moreover, a placebo control group would have been considered unethical because the vaccine was presumed to be effective. We identified 10 randomized controlled trials with the primary goal to assess the immunogenicity of stocked calf lymph‐derived first‐generation vaccines or second‐generation cell‐cultured vaccines in terms of major reaction rate as well as humoral and cellular responses as surrogate markers of protection. The prevailing question in the bioterrorism debate, whether a possible attack with smallpox could be countered with sufficient vaccinations, was addressed in these trials investigating different dilutions of the vaccines.

Although the methodological quality of most of the trials was not optimal (eg none mentioned allocation concealment), and homogeneity of parameters was not perfect (eg the threshold for fever differed slightly), the basic question about immunogenicity of the vaccines in non‐immune participants could be answered satisfactorily. All vaccines under investigation provided full immunogenicity (more than 95%) when undiluted, and even the 1:10 dilutions of the vaccines were still fully immunogenic when the starting concentration was defined. Thus, in case of a bioterrorist attack, Appendix 2 shows that at least 1000 million doses of first generation vaccine would be available, at least to those with access to the stockpile of 100 million undiluted doses. It was not surprising that many of the humoral and cellular immunity tests being used do not fully correlate with each other. This is because no generally agreed‐upon test for the level of humoral or cellular immunity proven to protect against smallpox was ever established during the eradication era, and modern trials cannot simply test for such a level when the disease is not existent. Therefore, studies meeting Prentice's conditions for the validation of these markers as surrogates for protection (Prentice 1989) do not exist and nothing can be said about the predictive value of major reaction rate and immune responses.

None of the trials investigated the duration of protection. However, three trials working with non‐naive participants reported rates of pre‐existing antibody levels displaying long‐lasting immune responses in most of the participants (Frey 2003; Greenberg 2005; Hsieh 2006). Both protective efficacy and duration of protection have been carefully formulated by the CDC as follows: "Smallpox vaccination provides high level immunity for 3 to 5 years and decreasing immunity thereafter. If a person is vaccinated again later, immunity lasts even longer. Historically, the vaccine has been effective in preventing smallpox infection in 95% of those vaccinated. In addition, the vaccine was proven to prevent or substantially lessen infection when given within a few days of exposure. It is important to note, however, that at the time when the smallpox vaccine was used to eradicate the disease, testing was not as advanced or precise as it is today, so there may still be things to learn about the vaccine and its effectiveness and length of protection" (CDC 2006).

Vaccines are frequently thought of as preventive measures which do much greater good than harm. So far, this does not apply to smallpox vaccines. The possible dangers of smallpox vaccines resurfaced in 2003 when mass vaccinations of healthcare workers and military were carried out and unforeseen cardiac complications were detected (Poland 2005a). As a consequence, the USA released the Smallpox Emergency Personnel Protection Act of 2003, and a Smallpox Vaccine Injury Compensation Program was established in order to provide "medical, lost employment income, and death benefits for eligible individuals who sustained covered injuries as a result of receiving smallpox vaccine or other covered countermeasures, or as a result of accidental exposure to vaccinia" (HRSA 2006).

The included trials reported no fatal adverse events, but 17 serious adverse events were registered. This number could possibly be higher because cardiac complications were taken into account only after some trials had already started. Moreover, a remarkable prevalence of local adverse events was observed. The rate of headache and fever in every second and tenth vaccinee, respectively, is in line with other studies (Frey 2002c). Severe headache following smallpox vaccination seemed to be generally transient, but debilitating headache may occur (Sejvar 2005). As expected for a live virus, local reactions (inflammation at vaccination site, lymphadenopathy) were common, but the reporting of these events was too variable to give an overall rate. In the three trials with the biggest numbers of participants, roughly every fifth person was missing scheduled activities or reported sleeping disorders. All participants knew that they received smallpox vaccine, so this might be a reason to check this effect with a placebo vaccine.

Because of contraindications and safety concerns, the public probably will not accept the use of first‐ and second‐generation vaccines unless there is a documented case of smallpox. Therefore, research leading to third‐generation vaccines, such as vaccinia viruses that are further attenuated, inactivated viruses, or, more promising, subunit or peptide‐based vaccines with or without adjuvants, should remain a significant goal of public health (Poland 2005b). A crucial consideration in the development of future vaccines is the ability of the virus to replicate. LC16m8, a replication‐competent attenuated smallpox vaccine, was developed in Japan during the 1960s by 53 serial passages of Lister strain through rabbit kidney cells in order to identify a less neutrovirulent strain (Wiser 2007). Mass trials in the 1970s were promising with "major reaction" rates similar to the parent Lister strain. Research on LC16m8 was resumed in 2002 in order to acquire an emergency stockpile of attenuated smallpox vaccine (Kenner 2006). Other research focuses on replication deficient, highly attenuated vaccines. The Modified Vaccinia Ankara strain (MVA) was developed in Germany during the 1970s by 572 serial passages of the Ankara strain in chicken embryo fibroblasts. In this process, the virus lost about 15% of its parental genome and its replication capability in most mammalian cells, including human cells (Drexler 2003; Wiser 2007). MVA was discussed as a vaccine candidate for immunosuppressed vaccinees and research on this strain was resumed in recent years. Research on subunit and DNA vaccines against smallpox is ongoing and first results are reviewed elsewhere (Wiser 2007). We have identified a number of registered ongoing trials and will include these results in future updates of this review. The use of smallpox vaccines in the absence of the disease is a political decision. Like many political issues, there is a spectrum of opinion about the risk of bioterrorism and the need for pre‐event vaccination. There is a rich literature about this subject, and a number of mathematical models have attempted to predict the nature of a smallpox outbreak with and without various levels of pre‐event vaccination. This debate is outside the scope of this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

First‐ and second‐generation vaccines diluted up to at least 1:10 are as effective as undiluted vaccine in terms of clinical success rate and immunogenicity. Dilutions did not reduce the frequency of adverse events. Success rate and immunogenicity were similar in naive and previously vaccinated persons, but adverse events were lower in previously vaccinated persons.

Smallpox vaccines display a high degree of immunogenicity plus a high rate of adverse events. Consequently a certain degree of protection can be expected, and there should be a high threshold for recommending smallpox vaccines.

The debate about biowarfare and its consequences, as well as the argument about the appropriate response to an attack with bioweapons, is outside the scope of this review.

Implications for research.

If the biowarfare threat is real, then it is relevant and important to have good data. To facilitate practical decisions, research on smallpox vaccines should be extended to reduce adverse events and maintain immunogenicity. Researchers should intensify efforts to educate the public about infection with smallpox and possible preventive measures.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format with minor editing. |

Acknowledgements

The editorial base for the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods: detailed search strategies

| Search set | CIDG SRa | CENTRAL | MEDLINE and EMBASEb | LILACSb |

| 1 | smallpox | SMALLPOX VACCINE | SMALLPOX VACCINE | smallpox |

| 2 | vaccin* | smallpox | smallpox | vaccin* |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | SMALLPOX | SMALLPOX | 1 and 2 |

| 4 | — | 2 or 3 | 2 or 3 | — |

| 5 | — | vaccin* | vaccin* | — |

| 6 | — | (4 and 5) or 1 | (4 and 5) or 1 | — |

aCochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register. bSearch terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2006); upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; lower case: free text term.

Appendix 2. Smallpox vaccines used in the included trials

| Vaccine | Company | Generation | Strain | Growing procedure | Other information | Trial(s) |

| Dryvax | Wyeth | First | NYCBOH | Calf lymph derived | Lyophilized, about 15 million doses stock | Frey 2002a, Frey 2002b, Frey 2003 |

| APSV | Aventis Pasteur | First | NYCBOH | Calf lymph derived | Frozen, about 85 million doses stock | Rock 2004, Talbot 2004 |

| Lancy‐vaxina | Berna Biotech | First | Lister | Calf lymph derived | Lyophilised | Kim 2005 |

| ACAM | Acambis | Second | NYCBOH | Cell culture | MRC‐5 cells (human diploid fibroblasts) | Artenstein 2005 (ACAM2000), Weltzin 2003 (ACAM1000) |

| CCSV | Dynport | Second | NYCBOH | Cell culture | MRC‐5 cells (human diploid fibroblasts) | Greenberg 2005 |

| Lister/Elstree | CDC Taiwan | First | Lister | Calf lymph derived | Lyophilized | Hsieh 2006 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Diluted vaccine vs undiluted smallpox vaccine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaccination success rate (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate) | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Dilution 1:3.2 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.79, 1.13] |

| 1.2 Dilution 1:5 | 6 | 888 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.90, 1.03] |

| 1.3 Dilution 1:10 | 9 | 1259 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.77, 1.02] |

| 1.4 Dilution 1:20 | 1 | 101 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.46, 0.74] |

| 1.5 Dilution 1:25 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.83, 1.09] |

| 1.6 Dilution 1:30 to 1:32 | 2 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.29, 1.91] |

| 1.7 Dilution 1:50 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.8 Dilution 1:100 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.06, 0.45] |

| 2 Seroconversion | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Dryvax dilution 1:5 | 4 | 601 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.82, 1.07] |

| 2.2 Dryvax dilution 1:10 | 5 | 750 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.81, 1.04] |

| 2.3 Dryvax dilution 1:100 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.06, 0.51] |

| 2.4 ACAM2000 dilution 1:20 | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.47, 0.78] |

| 2.5 CCSV dilution 1:25 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.83, 1.09] |

| 2.6 CCSV dilution 1:50 | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.83, 1.09] |

| 2.7 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.8 Lister dilution 1:5 | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.9 Lister dilution 1:30 | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.90, 1.04] |

| 3 Adverse event: fever | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 APVS dilution 1:5 | 3 | 447 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.82, 1.90] |

| 3.2 APVS dilution 1:10 | 3 | 451 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.59, 2.52] |

| 3.3 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.53, 4.05] |

| 3.4 ACAM2000 dilution 1:20 | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.64, 6.23] |

| 4 Adverse event: headache | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 APVS dilution 1:5 | 2 | 379 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.79, 1.03] |

| 4.2 APVS dilution 1:10 | 3 | 490 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.76, 1.16] |

| 4.3 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.40, 1.34] |

| 4.4 ACAM2000 dilution 1:20 | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.86, 1.81] |

| 5 Adverse event: pain at vaccination site | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 APVS dilution 1:5 | 2 | 379 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.78, 1.13] |

| 5.2 APVS dilution 1:10 | 3 | 490 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.83, 1.11] |

| 5.3 ACAM2000 dilution 1:20 | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.44, 0.91] |

| 6 Adverse event: lymphadenopathy | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Dryvax dilution 1:5 | 4 | 787 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.54, 1.35] |

| 6.2 Dryvax dilution 1:10 | 5 | 1009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.67, 1.14] |

| 6.3 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.65, 1.62] |

| 6.4 ACAM2000 dilution 1:20 | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.40, 1.31] |

Comparison 2. New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaccination success rate (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate) | 3 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.94, 1.13] |

| 1.1 ACAM1000 | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.94, 1.13] |

| 1.2 ACAM2000 | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 CCSV | 1 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Seroconversion | 3 | 429 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.94, 1.04] |

| 2.1 ACAM1000 | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.94, 1.13] |

| 2.2 ACAM2000 | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.90, 1.07] |

| 2.3 CCSV | 1 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.88, 1.04] |

| 3 Adverse event: fever | 2 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.06, 1.54] |

| 3.1 ACAM2000 | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.15, 1.49] |

| 3.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.37] |

| 4 Adverse event: headache | 2 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.64, 1.02] |

| 4.1 ACAM2000 | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.56, 1.20] |

| 4.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.60, 1.08] |

| 5 Adverse event: pain at vaccination site | 2 | 268 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.60, 1.25] |

| 5.1 ACAM2000 | 1 | 118 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.53, 0.95] |

| 5.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.83, 1.27] |

| 6 Adverse event: lymphadenopathy | 3 | 310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.91, 1.16] |

| 6.1 ACAM1000 | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.69, 1.90] |

| 6.2 ACAM2000 | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.57, 1.62] |

| 6.3 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.90, 1.17] |

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 New‐generation versus original (Dryvax) smallpox vaccine, Outcome 6 Adverse event: lymphadenopathy.

Comparison 3. Non‐naive vs naive participants.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaccination success rate (pustule at vaccination site, 'take' rate) | 3 | 410 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.82, 1.16] |

| 1.1 Dryvax | 2 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.82, 1.16] |

| 1.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 Lister undiluted | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.4 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Seroconversion | 2 | 380 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.92, 1.11] |

| 2.1 Dryvax | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.86, 1.11] |

| 2.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.92, 1.20] |

| 2.3 Lister undiluted | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.4 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Adverse event: fever | 2 | 380 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.11, 0.82] |

| 3.1 Dryvax | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.04, 3.10] |

| 3.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.06, 36.53] |

| 3.3 Lister undiluted | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.02, 1.19] |

| 3.4 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.06, 1.26] |

| 4 Adverse event: headache | 2 | 380 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.31, 0.91] |

| 4.1 Dryvax | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.28, 0.74] |

| 4.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.64, 1.32] |

| 4.3 Lister undiluted | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.15, 0.80] |

| 4.4 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.14, 1.07] |

| 5 Adverse event: pain at vaccination site | 1 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.43, 0.95] |

| 5.1 Dryvax | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.58, 1.05] |

| 5.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.38, 0.71] |

| 6 Adverse event: lymphadenopathy | 2 | 380 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.36, 0.56] |

| 6.1 Dryvax | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.28, 0.62] |

| 6.2 CCSV | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.38, 0.71] |

| 6.3 Lister undiluted | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.12, 0.58] |

| 6.4 Lister dilution 1:10 | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.18, 0.79] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Artenstein 2005.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: double (participants and investigators) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; none lost to follow up or withdrew, see 'Participants' Length of follow up: 6 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 656 screened and 353 enrolled; 5 participants excluded from antibody or efficacy analysis (reason: baseline seropositivity or study assessment not performed or outside of allowable window) Inclusion criteria: healthy adults; 18 to 29 years; women of childbearing potential utilized combined hormonal contraception or an intrauterine device for at least 30 days before screening Exclusion criteria: military service before 1989; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; immunosuppression; renal disease; history of atopic dermatitis; open wound or burn; laboratory abnormalities indicating significant organ dysfunction or infection; allergy to latex or the antibiotics present in Dryvax and ACAM2000; hepatitis C seropositivity; hepatitis B surface antigenemia; blood product transfusion within previous 6 months; and household or intimate exposures to pregnant women, immunosuppressed persons, persons with atopic dermatitis, or infants aged 1 year or less; based on previously unsuspected findings of cardiac complications that occurred during the concurrent US Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC) smallpox vaccination programme using Dryvax, exclusion criteria amended to include known cardiac disease |

|

| Interventions | ACAM2000:

1. Undiluted

2. Dilution 1:5

3. Dilution 1:10

4. Dilution 1:20 Dryvax: 5. Undiluted |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (50% plaque‐forming units (PFU) reduction) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA | |

Frey 2002a.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: single (participants) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; see 'Participants' Length of follow up: 56 days |

|

| Participants | Number: 680 enrolled and vaccinated; 665 developed a positive reaction ("take") at vaccination site and this number (665) used in trial report as denominator of analysis of adverse events Inclusion criteria: healthy adults aged 18 to 32 years Exclusion criteria: vaccinia scar; vaccinia vaccination; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐AB; vaccination contraindications according to package insert (ie pregnancy, immunosuppression, and eczema), and protocol‐specified (history of live‐attenuated virus vaccination within 60 days before trial, receipt of blood products or immunoglobulin within 6 months before trial, household contact, sexual contact, or occupational exposure to someone with 1 or more of exclusion criteria listed in package insert); contact with infants < 12 months |

|

| Interventions | Dryvax smallpox vaccine: 1. Undiluted (108.1 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL) 2. Dilution 1:5 3. Dilution 1:10 | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (60% PFU reduction) and cellular response 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA | |

Frey 2002b.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: double (participants and investigators) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; see 'Participants' Length of follow up: 12 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 60 enrolled; 1 withdrew for reasons unrelated to study; 55 provided blood samples 1 year after the study Inclusion criteria: healthy adults aged 18 to 30 years Exclusion criteria: vaccinia scar; vaccinia vaccination; HbS‐AB; HepC‐AB; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐AB; vaccination contraindications according to package insert (ie pregnancy, immunosuppression, and eczema) and protocol‐specified (ie history of live‐attenuated virus vaccination within 60 days before trial, receipt of blood products or immune globulin within 6 months before study, and household contact, sexual contact, or occupational exposure to pregnant women, immunosuppressed persons, persons with eczema, or infants < 12 months) |

|

| Interventions | Dryvax smallpox vaccine: 2. Undiluted (107.8 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL) 2. Dilution 1:10 3. Dilution 1:100 | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (60% PFU reduction) and cellular response 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA | |

Frey 2003.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: single (participants) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; see 'Participants' Length of follow up: 6 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 90 (80 vaccinia non‐naive volunteers, 10 vaccinia naive volunteers) enrolled; 64/80 developed a positive reaction ("take") at vaccination site, and this number (64) used in the article as denominator of analysis of adverse events Inclusion criteria: healthy adults; 32 to 60 years; smallpox vaccination before 1971 and typical vaccinia scar or documentation Exclusion criteria: allergies to vaccine components, vaccinia immunoglobulin, cidofovir, probenecid, or allergies to vaccine components, vaccinia Ig, cidofovir, probenecid, or contraindications according to package insert (ie pregnancy, immunosuppression, and eczema) and protocol‐specified (history of live‐attenuated virus vaccination within 60 days before trial, receipt of blood products or immunoglobulin within 6 months before study, household contact, sexual contact, or occupational exposure to someone with 1 or more of exclusion criteria listed in package insert); contact with infants < 12 months |

|

| Interventions | Dryvax smallpox vaccine 1. Undiluted (107.5 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL) 2. Dilution 1:3.2 3. Dilution 1:10 4. Dilution 1:32 | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (60% PFU reduction) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA | |

Greenberg 2005.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: computer‐generated process (PROC PLAN in SAS) Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: double (participants and investigators) and single (1 cohort) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; see 'Participants' Length of follow up: 6 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 457 screened for eligibility, 350 enrolled in 5 cohorts; cohort 1 to 3 and cohort 5 vaccinia‐naive, and cohort 4 was vaccinia‐non‐naive; cohort 5 enrolled half a year after other cohorts; none lost to follow up at day 60, 1 lost to follow up at day 180 Inclusion criteria: healthy adult men and women aged between 18 and 30 years with no previous smallpox vaccination; aged between 32 and 65 with history of smallpox vaccination and characteristic vaccination scar; agreed to use barrier or hormonal contraception if of child‐bearing potential Exclusion criteria: volunteer or any household or intimate contacts of the volunteer with (1) history of any acute or chronic exfoliative skin condition or other conditions that disrupt the integrity of the skin, or (2) condition resulting in immunocompromise whether due to disease or medication; healthcare workers caring for vulnerable people (neonates, pregnant women, those with degraded skin integrity, or who were immunocompromised for any reason) unable to be away from direct patient care until vaccine scab fallen off; household contact or regular contact with a child < 3 years; history of cancer; present medical or psychiatric condition that precluded compliance with protocol; allergy to any components in either vaccine, vaccinia immune globulin, thiomeral, probenecid, or cidofovir; participation in another investigational trial within 1 month of screening; previous vaccination for influenza within 2 weeks or any live vaccine within 3 months before or after vaccination; treatment with any immunosuppressive drug within 3 months of enrolment; admission to hospital within 6 months of enrolment; sex, or other close contact with a woman who is or intends to become pregnant within 60 days after vaccination; positive pregnancy test within 14 days of enrolment; history of any chronic or acute medical condition judged to be not well controlled; previous admission to hospital as a result of previous smallpox vaccination; any other reason volunteer thought to be unsuitable by the principal investigator |

|

| Interventions | CCSV (Dynport)

1. Undiluted (2.5 x 105 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL)

2. Dilution 1:5

3. Dilution 1:10

4. Dilution 1:25

5. Dilution 1:50 Dryvax: 6. Undiluted (2.5 x 105 PFU/mL) |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (50% PFU reduction) and cellular response (measured in a semiquantitative cell‐mediated cytoxicity assay) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA | |

Hsieh 2006.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: unclear Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: single (participants) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; 100% (no loss to follow up) Length of follow up: 8 weeks |

|

| Participants | Number: 219; 97 naive (aged 20 to 23 years) and 122 previously vaccinated participants (aged 24 to 65 years)

Inclusion criteria: healthy adult Exclusion criteria: pregnancy; severe eczema; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; history of live‐attenuated virus vaccination within 60 days; receipt of blood products or immune globulin within last 6 months; household contact; sexual contact or occupational exposure to pregnant women |

|

| Interventions | Lister vaccine, Elstree strain, produced in 1981 or earlier by the Centers for Disease Control Taiwan For naive participants: 1. Undiluted vaccine 109 plaque‐forming units (PFU) 2. 1:5 dilution 3. 1:10 dilution For previously vaccinated participants: 4. Undiluted vaccine 109 PFU 5. 1:10 dilution 6. 1:30 dilution |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response and T‐cell response (measured by vaccinia‐specific CD69 expression on T‐cell subsets) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: China Significant neutralizing antibody titre defined one that caused a 60% reduction in pock count Significant antibody response defined as positive seroconversion or ≥ 4‐fold rise of vaccinia‐specific antibody titre |

|

Kim 2005.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: single (participants) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate 100% (no loss to follow up) Length of follow up: 1 month |

|

| Participants | Number: 138 screened for eligibility, and 112 enrolled Inclusion criteria: healthy adults aged 25 to 60 years Exclusion criteria: according to US Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for exclusion |

|

| Interventions | Lancy‐Vaxina vaccine (Berna Biotech) 1. Undiluted (107.7 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL) 2. Dilution 1:10 | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (60% PFU reduction) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: South Korea | |

Rock 2004.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: double (participants and investigators) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; 100% (no loss to follow up) Length of follow up: 1 month |

|

| Participants | Number: 148 enrolled; 107 participated in a substudy evaluating adverse events in relation to cytokine levels Inclusion criteria: healthy adults aged 18 to 32 years Exclusion criteria: vaccinia scar; vaccinia vaccination; HbS‐AB; HepC‐AB; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐AB; vaccination contraindications according to package insert (ie pregnancy, immunosuppression, and eczema) and protocol‐specified (ie history of live‐attenuated virus vaccination within 60 days before trial, receipt of blood products or immune globulin within 6 months before trial, household contact, sexual contact, or occupational exposure to pregnant women, immunosuppressed persons, persons with eczema, or infants < 12 months) |

|

| Interventions | Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APVS) 1. Undiluted 2. Dilution 1:5 3. Dilution 1:10 | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Cellular response (assessed using cytometric Bead Array (CBA) FACS analysis software) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA | |

Talbot 2004.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: in‐house custom‐built programme with blocks of size 6 Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: double (participants and investigators) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; 100% (no loss to follow up) Length of follow up: 6 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 458 screened for eligibility, and 340 enrolled Inclusion criteria: healthy adults aged 18 to 32 years Exclusion criteria: vaccinia scar; vaccinia vaccination; history of any of autoimmune disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, solid organ or bone marrow transplantation, malignancy, eczema, prior vaccination with any vaccinia‐vectored or other poxvectored experimental vaccine, or allergies to the vaccine components; volunteers with history of or current illegal injection drug use; current exfoliative skin disorders; use of immunosuppressive medications; medical or psychiatric conditions or occupational responsibilities that precluded volunteer compliance; and pregnant or lactating women; volunteers with household or sexual contacts with a history of or concurrent eczema, a history of exfoliative skin disorders, a history of the immunosuppressive conditions noted above, ongoing pregnancy, or children < 1 year also prohibited from participation |

|

| Interventions | Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APVS) 1. Undiluted (107.6 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL) 2. Dilution 1:5 3. Dilution 1:10 | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (60% PFU reduction) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: USA Trial terminated before time, because US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) temporarily suspended (in February 2003) all vaccinia trials due to adverse events noted in the ongoing civilian and military vaccination campaigns; number of participants was supposed to be 444, and at time of interruption 340 volunteers were recruited |

|

Weltzin 2003.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: not described Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: double (participants and investigators) Inclusion of all randomized participants: adequate; 100% (no loss to follow up) Length of follow up: 6 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 60 enrolled Inclusion criteria: healthy adults aged 18 to 29 years Exclusion criteria: vaccinia vaccination; risk factors for serious adverse events (immune deficiency, eczema) in participants or close contacts |

|

| Interventions | 1. ACAM1000 undiluted (108 plaque‐forming units (PFU)/mL) 2. Dryvax undiluted (108 PFU/mL) | |

| Outcomes | 1. Success rate 2. Humoral response (50% PFU reduction) and cellullar response (assessed using CTL activity assays, ELISPOT, and lymphoproliferation assays) 3. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: [USA] | |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Agafonov 1977 | Non‐randomized study |

| Andzhaparidze 1980 | Non‐randomized study |

| Banerji 1972 | Non‐randomized study |

| Benenson 1977 | Non‐randomized study |

| Chernos 1977 | Non‐randomized study |

| Chernos 1990 | Non‐randomized study |

| Cherry 1977 | Non‐randomized study |

| Christensen 1966 | Non‐randomized study |

| Denisov 1975 | Non‐randomized study |

| Evgrafov 1978 | Non‐randomized study |

| Galasso 1977 | Non‐randomized study |

| Gateff 1973 | Non‐randomized study |

| Herrero 1969 | Non‐randomized study |

| Huerta 2006 | Non‐randomized study |

| Karchmer 1971 | Simultaneous application of vaccines and no appropriate outcomes reported |

| Kennedy 2004 | Non‐randomized study |

| Khliabich 1978 | Non‐randomized study |

| Lelong 1952 | Non‐randomized study |

| Lev 1972 | Non‐randomized study |

| Lin 1965 | Non‐randomized study |

| Marennikova 1966 | Non‐randomized study |

| Marennikova 1977 | Non‐randomized study |

| Martin du Pan 1966 | Non‐randomized study |

| Mel'nikov 2005 | Non‐randomized study |

| Meyer 1964 | Non‐randomized study |

| Mihailescu 1988 | Non‐randomized study |

| Millar 1969 | Non‐randomized study |

| Mobest 1974 | Non‐randomized study |

| Murruzzu 1967 | Non‐randomized study |

| Nath 1970 | Non‐randomized study |

| Neff 1969 | Quasi‐randomized controlled trial |

| Nyerges 1968 | Non‐randomized study |

| Nyerges 1972 | Non‐randomized study |

| Nyerges 1973 | Non‐randomized study |

| Pattanayak 1970 | Non‐randomized study |

| Petersen 1966 | Non‐randomized study |

| Podkuiko 1993 | Non‐randomized study |

| Roberto 1969 | Non‐randomized study |

| Sergeev 2004 | Non‐randomized study |

| Sherman 1967 | Non‐randomized study |

| Shinozaki 1969 | Non‐randomized study |

| Snell 1965 | Non‐randomized study |

| Tauraso 1972 | Non‐randomized study |

| Unanov 1966 | Non‐randomized study |

| Vaughan 1972 | Simultaneous administration of Bacille Calmette‐Guérin (BCG) vaccine and smallpox vaccine; no smallpox‐only group |

| Vaughan 1973 | No appropriate outcome measures reported |

| Vollmar 2006 | Non‐randomized study |

| Waibel 2004 | Does not fit inclusion criteria (a trial to prevent secondary transmission) |

| Waibel 2006 | Does not fit inclusion criteria (a trial of different vaccination sites) |

| Wesley 1975 | Non‐randomized study |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Acambis‐a.

| Trial name or title | "The effect of dose on safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of ACAM2000 smallpox vaccine in adults with previous smallpox vaccination" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 28+ years Expected total enrolment: 350 |

| Interventions | 1. ACAM2000: 4 dose levels 2. Dryvax: standard dose |

| Outcomes | 1. Safety and tolerabilty 2. Immunogenicity by (a) major cutaneous reaction; (b) neutralizing antibodies, including fold‐increase in antibody titre between baseline and day 30 sera, and geometric mean vaccinia neutralizing antibody titre on day 30 3. Minimum dose calculated to produce major cutaneous reaction in at least 90% of the population |

| Starting date | January to March 2003 |

| Contact information | Acambis website (www.acambis.com) |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00053482 Sponsor: Acambis Location: USA Phase II study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, dose comparison, parallel assignment |

Acambis‐b.

| Trial name or title | "The effect of dose on safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of ACAM2000 smallpox vaccine in adults without previous smallpox vaccination" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 29 years Expected total enrolment: 350 |

| Interventions | 1. ACAM2000: 4 dose levels 2. Dryvax: standard dose |

| Outcomes | As for Acambis‐a |

| Starting date | January to March 2003 |

| Contact information | Acambis website (www.acambis.com) |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00053495 Sponsor: Acambis Location: USA Phase II study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, dose comparison, parallel assignment |

Acambis‐c.

| Trial name or title | "The effect of dose on safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of ACAM1000 smallpox vaccine in adults without previous smallpox vaccination A Phase 2, randomized, double‐blind, dose‐response study" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 29 years Expected total enrolment: 350 |

| Interventions | 1. ACAM1000: 3 dose levels 2. Dryvax: standard dose |

| Outcomes | As for Acambis‐a |

| Starting date | Start: September 2002 |

| Contact information | Acambis website (www.acambis.com) |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00053508 Sponsor: Acambis Location: USA Phase II study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, dose comparison, parallel assignment |

Acambis‐d.

| Trial name or title | "Safety, tolerability, and immune response of ACAM3000 Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) smallpox vaccine in adults" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 31 years Expected total enrolment: 110 |

| Interventions | 1. ACAM3000 2. MVA 3. Dryvax |

| Outcomes | 1. Safety and effectiveness 2. Immunogenicity |

| Starting date | Start: April 2004 |

| Contact information | Paul S Blum, Acambis NIH Vaccine Research Center for Disease Control |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00079820 Sponsor: Acambis Location: USA Phase I study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, parallel assignment, safety study |

Acambis‐e.

| Trial name or title | "A Phase 1, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to assess the safety and immunogenicity of MVA3000 Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) smallpox vaccine in vaccinia‐naive human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐seropositive subjects" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 35 Expected total enrolment: 90 |

| Interventions | 1. ACAM3000 2. MVA |

| Outcomes | 1. Safety 2. Immunogenicity |

| Starting date | Start: October 2006 Last follow up: February 2008 |

| Contact information | Matt Desmond +617 7614200 matt.desmond@acambis.com NCT00282581 |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00282581 Sponsor: Acambis Location: USA Phase I study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, single group assignment |

Acambis‐f.

| Trial name or title | "A Phase 1, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study of the safety and immunogenicity of two injections of MVA3000 Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) smallpox vaccine in vaccinia naive adult subjects with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD)" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 35 years Expected total enrolment: 45 |

| Interventions | MVA3000 |

| Outcomes | 1. Primary: safety 2. Secondary: immunogenicity |

| Starting date | Start: October 2006 Last follow up: September 2007 |

| Contact information | Acambis website (www.acambis.com) |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00389103 Sponsor: Acambis Location: USA Phase I study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, parallel assignment |

Bavarian Nordic‐a.

| Trial name or title | "A multicenter, open‐label Phase I/II study to evaluate safety and immunogenicity of MVA‐BN® smallpox vaccine in HIV infected subjects (CD4 counts >350/µl) and healthy subjects with and without previous smallpox vaccination" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 55 years Expected total enrolment: 150 |

| Interventions | IMVAMUNE (MVA‐BN) |

| Outcomes | Primary:

1. Serious and/or unexpected adverse reaction Secondary: 2. Neutralization assay specific seroconversion rates and geometric mean titres 3. ELISA specific seroconversion rates and geometric mean titres |

| Starting date | Start: July 2005 |

| Contact information | Richard N Greenberg, Principal Investigator, University of Kentucky School of Medicine, Kentucky 40536‐0093, USA |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00189904 Sponsor: Bavarian Nordic Location: Kentucky, USA Phase I/Phase II study design: prevention, non‐randomized, open label, uncontrolled, parallel assignment |

Bavarian Nordic‐b.

| Trial name or title | "An open‐label, controlled Phase I pilot study to evaluate safety and immunogenicity of MVA‐BN® smallpox vaccine in 18‐40 year old vaccinia‐naïve subjects with atopic disorders" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 40 years Expected total enrolment: 60 |

| Interventions | IMVAMUNE (MVA‐BN) |

| Outcomes | Primary:

1. Serious adverse events Secondary: 2. ELISA specific seroconversion rates and geometric mean titres 3. Neutralization assay specific seroconversion rates and geometric mean titres |

| Starting date | Start: April 2004 Completion: April 2006 |

| Contact information | Frank von Sonnenburg, Principal Investigator, Dept. of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, University of Munich |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00189917 Sponsor: Bavarian Nordic Location: Bavaria, Germany Phase I Study design: prevention, non‐randomized, open label, active control, parallel assignment |

Bavarian Nordic‐c.

| Trial name or title | "Phase I study on safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of the MVA‐BN vaccine administered to healthy subjects" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 20 to 55 years Expected total enrolment: 90 |

| Interventions | MVA‐BN |

| Outcomes | 1. Safety and tolerability 2. Immunogenicity |

| Starting date | Start: April 2001 Completion: July 2003 |

| Contact information | Karl M Eckl, Principal Investigator, Pharma PlanNet Contract Research GmbH, Moenchengladbach 41061, Germany |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00189943 Sponsor: Bavarian Nordic Location: Germany Phase I study design: prevention, randomized, double blind, uncontrolled, parallel assignment |

Bavarian Nordic‐d.

| Trial name or title | "Phase II, double‐blind, randomised, dose‐finding study to evaluate the immunogenicity of three different doses of MVA‐BN smallpox vaccine in 18‐30 year old smallpox naïve healthy subjects" |

| Methods | — |

| Participants | Male/female 18 to 30 years Expected total enrolment: 165 |

| Interventions | IMVAMUNE (MVA‐BN) |

| Outcomes | Primary: 1. ELISA specific seroconversion rate and geometric mean titres (at all blood sampling time points) Secondary: 2. Occurrence, relationship and intensity of adverse event at any time during the study |