Abstract

We performed aCGH, SKY /FISH, molecular mapping and expression analyses on a permanent CD8+ NK/T cell line, ‘SRIK-NKL’ established from a lymphoma (ALL) patient, in attempt to define the fundamental genetic profile of its unique NK phenotypes. aCGH revealed hemizygous deletion of 6p containing genes responsible for hematopoietic functions. The SKY demonstrated that a constitutive reciprocal translocation, rcpt(5;14)(p13.2;q11) is a stable marker. Using somatic hybrids containing der(5) derived from SRIK-NKL, we found that the breakpoint in one homologue of no. 5 is located upstream of IL7R and also that the breakpoint in no. 14 is located within TRA@. The FISH analysis using BAC which contains TRA@ and its flanking region further revealed a ~231 kb deletion within 14q11 in the der(5) but not in the normal homologue of no. 14. The RT-PCR analysis detected mRNA for TRA@ transcripts which were extending across, but not including, the deleted region. IL7R was detected at least at mRNA levels. These findings were consistent with the immunological findings that TRA@ and IL7R are both expressed at mRNA levels and TRA@ at cytoplasmic protein levels in SRIK-NKL cells. In addition to rept(5;14), aCGH identified novel copy number abnormalities suggesting that the unique phenotype of the SRIK-NKL cell line is not solely due to the TRA@ rearrangement. These findings provide supportive evidence for the notion that SRIK-NKL cells may be useful for studying not only the function of NK cells but also genetic deregulations associated with leukemiogenesis.

1. Introduction

Although the fundamental understanding of defense systems involving most hematopoietic repertoires in responses to external pathogens such as virus and bacteria as well as neoplasm has been established, the role of a specialized lymphocyte subset called “natural killer (NK) cells” still remains unclear. This is largely due to the fact that, whereas NK and T cells are well established to evolve from common pluripotential cells [1-4], a question remains unanswered as to at which stage the NK phenotypes emerges. A family of NK cells is definitely innate lymphocyte effector cells, but is distinct from a classic family of T cells in that functional cytolysis-triggering receptors such as NKp46, NKp44 and NKp30 are apparently expressed [5-7]. Despite such puzzling phenotypes, a general consensus is that NK cells are composed of a large family of lymphocytes, which includes NK-T, NK-CTL, CD8αα+ NK, CD3+ NK, decidual and intestinal NK cells [1, 3, 4, 8-10]. Because of their ability to purge transformed cells in vitro, the viable NK cells and their genetically engineered variants [for example, ref 11-13] may have potential values in clinical applications such as biological therapies. To manipulate the biological functions of NK cells, e.g. interaction with malignant cells and external pathogens as well as the signal transduction pathway in response to cytokines, many investigators have attempted to establish cell lines, which stably express distinct NK-specific phenotypes. Unfortunately, many, if not all, of the cell lines hitherto ‘dubbed’ as NK cells, do not meet this fundamental criterion [14-16]. We have recently established an autocrine cell line from a patient of acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL), to which the term “CD8+NK/T (SRIK-NKL)” was coined because of their constitutive expression of discrete, bi-functional CD8+ T/NK phenotypes [17, 18]. For example, like classical T cells, SRIK-NKL cells express NKG2D and TRB@ surface molecules. On the other hand, unlike classic T cells, SRIK-NKL cells apparently use non-MHC, non-TRA@ restricted mechanisms to kill NK-sensitive K562 cells [14, 17, 18]. These findings indicate that SRIK-NKL cells might have originated from a novel subset of lymphocyte-lineage repertoire.

The break/fusion-points of chromosome translocations often contain genes which affect biologically and genetically crucial functions as well as differentiation processes [19-23]. We have analyzed SRIK-NKL cells at various culture passages over 15 years, and found that this cell line contains rept [5;14][p13.2;q11], a constitutive reciprocal translocation which has not previously been described for NK leukemia or lymphoma, T-ALL or any other human malignancies [24-25]. In terms of cytogenetic profile, Drexler classified leukemia-lymphoma lines which consists of 10 NK cell lines [4]. SRIK-NKL cell line is not like any of these NK cell lines which are of heterogenous origins [4]. Interestingly, the SRIK-NKL cells hardly express surface TRA@ (gene clusters are located on no. 14) but express surface markers encoded by TRB@ which frequently undergoes physiological gene recombination-rearrangements [17]. In ALL carrying t(7;9), the structural rearrangements usually occur very frequently concomitant with disruption of TRB@ genes and such rearrangements activate oncogenes flanking the breakpoints [26-29]. In view of these findings, we undertook genomic and molecular analyses to validate the SRIK-NKL cells and answer the central question if their genetic profile may merit a future application in cancer therapy. This study was focused on the following specific questions: 1) whether or not the breakpoint of chromosome 14 is located in the TRA@ domain, 2) whether or not any genes on chromosome 5 are on or in the flanking region of the fusion points in this rept(5;14)(p13.2;q11) translocation, and 3) whether any rearrangement has taken place in the region of no. 7 containing TRB@ genes. We also addressed to the question whether any changes occurred in the expression levels of TRA@ and TRB@.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Establishment and maintenance of SRIK-NKL cell line

The cell line was established from peripheral leukocytes of an acute lymphoblastic lymphoma patient during relapse phase and has been maintained at ~0.7×106 cell/ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (17, 18). The doubling time was 36-48 hours.

Establishment of somatic hybrid cells containing t(5;14)

SRIK-NKL cells were fused with TK-minus mouse 3T3 mutant cell line using standard PEG protocols [30-33]. The HAT-resistant cells were subcloned and propagated for DNA/RNA extraction, SKY/FISH analysis and molecular mapping.

2.2 Spectral Karyotyping (SKY) analysis

The cells treated with Colcemid at 0.06 μg/ml for 2-4 hr were harvested according to the conventional methods. After treatment with CHS solution for 50 min, cells were fixed with Carnoy’s fixative (1:3 glacial acetic acid/methanol). Chromosome spreads were prepared using air-drying methods, and subjected to sequential digestion with RNase and pepsin according to the procedure recommended by Applied Spectral Imaging, Inc. (API: Carlsbad, CA), followed by denaturation in 70 % formamide and hybridization with human SKY paint probes. The detailed methods using a variable ratio and combination of individual fluorochromes (Rhodamine, Texas-Red, Cy5, FITC and CY5.5) were described elsewhere [34]. The SKY-DAPI images were captured using a Nikon microscope equipped with a Spectral cube and Interferometer module. Spectra-Karyotypes were prepared using SKY View software (Version 1.62).

2.3 Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization

The BAC DNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was carried out as described by Chernova and Cowell [35]. The BAC DNA partially purified with standard alkaline-lysis procedures was labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP using the DIG-Nick Translation Kit or with Biotin-16-dUTP using the Biotin-Nick Translation Kit (Roche). Two μg of the labeled probe was mixed with a 4-fold excess of human Cot-1 DNA (Roche) and a 17-fold excess of salmon sperm DNA (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 20 μl of hybridization mixture consisting of 50% formamide, 2X SSC, and 10% dextran sulfate. Chromosome slides were denatured at 70 °C in 70% formamide/2X SSC for 2 min. followed by washes in 70%, 80%, and 100% ethanol for 2 min. each prior to hybridization. The probe mixture, denatured for 5 min at 80 °C and then annealed for 45 min at 37 °C, was applied to the slide overlaid with a cover slip and sealed with rubber cement. After hybridization for 16-20 hours at 37 °C, the slides were developed by washing 3 times at 45 °C in 50% formamide/2X SSC, 2 times in 1X SSC, followed by one time wash in 4X SCC/1% Tween. The FISH signals were detected using anti-digoxigenin fluorescein Fab fragments or Avidin-Rhodamine (Roche) and the DAPI images of chromosomes were captured using a Nikon fluorescent microscope and analyzed with EasyFISH software (ASI).

2.4 Mapping of break/fusion points using somatic cell hybrids and PCR

A series of somatic cell hybrid cells derived from the CD8+ SRIK-NKL/TK− 3T3 fusion was screened to subclone the cells carrying der(5)t(5;14) or der(14)t(5;14). Genomic DNA was extracted from the parental and somatic cell hybrid subclones using a standard phenol/chloroform method described previously [36]. Molecular markers screened for the presence of normal and derivative chromosomes 5 and 14 were four genomic primer sets specific for human gene sequences on chromosome regions, 5p13.2, 5q34, 14q11.2 and 14q32.32. The screening primers included: RAD1 Exon 5 Forward 5′-ACGTATAAAGTGAAATCTAGGACCTT-3′ and Reverse 5′-TGAATTGGCATTAGCTTTCTG-3′, SLIT3 Exon 38 Forward 5′-AAAGCAGCCTACCTGGGAAC-3′ and Reverse 5′-CTGTCCCAACTCCA TCAAGC-3′, RAB2B Exon 9 Forward 5′-CGTGCCTGGCCTAAATAAAT-3′ and Reverse 5′-GCTCTTGGGCAAGTAGAGGA-3′ and TNFAIP2 Exon 2 Forward 5′-CCACATCAGAGGCAGAGTCA-3′ and Reverse 5′-TTGGTGAAGACGCAGAACAC-3′. PCR reactions were performed using 50 ng of genomic DNA in final concentrations of 1x PCR buffer, 2.25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 2.5% Q Buffer and 1 U of Taq polymerase (QIAGEN). The reactions were performed using a hot-start protocol at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 20 sec, 58°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec, and concluding with a 5 min elongation step at 72°C.

Three somatic cell hybrid clones were found to contain the derivative chromosome 5, but only those containing neither normal copies of chromosomes 5 and 14 nor the derivative chromosome 14 were used to map the translocation breakpoints. A series of multiple primer sets were used to fine map the break/fusion points until arriving at the final primer pairs for the chromosome 5 (IL7R 5’ORF (2.6Kb) Forward 5′-CTGTTGTTCCCCCACAATCT-3′ and Reverse 5′-CATGTGCTGGTTTGTTCTGG-3′, IL7R 5’ORF (3.1 Kb) Forward 5′-CAGCCCTGAGTAGCCAAGAC-3′ and Reverse 5′-TCCTCCTCTTCACCCATCAC-3′) and chromosome 14 (TRAJ48 proximal to breakpoint (BP) Forward 5′-GACGGAA-CGTCAGGCAGTAT-3′ and Reverse 5′-CCAAACCCAGAGATTTCCAA-3′, TRAJ47 distal to BP Forward 5′-CAAAATGGAACGGAAAGCAT-3′ and Reverse 5′-AGGGAGCAGACTAACCGTCA-3′).

2.5 RT-PCR gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the SRIK-NKL, HL60 and LNCaP cell lines using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA was performed using the SuperScript II® protocol (Invitrogen). PCR reactions were carried-out using a 10% aliquot of the RT reaction and the following primers: IL7R Forward 5′-AATACATCACACTTGCAAAAGAAG-3′ and Reverse 5′-ATTCCCAGCCAGGCATGT-3′, TRA@ Forward 5′-TCGTCTGTTCCACCATATCTCT-3′ and Reverse 5′-GCACTGTTGCTCTTGAAGTCC-3′, GAPDH Forward 5′-TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGG-3′ and Reverse 5′-CATGTAGGCCATGA GGTCCACCAC-3′. The reaction conditions included a hot-start at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 20 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec, and concluding with a 5 min elongation step at 72°C.

RPCI custom CGH Array

The preparation of Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) custom CGH arrays using RPCI-11 BACs has been described previously [37, 38]. Briefly, the RPCI array contains ~6,000 RPCI-11 BAC clones that provide an average resolution across the genome of 420 kilobases. BACs were printed in triplicate on amino-silanated glass slides (Schott Nexterion, type A) using a MicroGrid ll TAS arrayer (Apogent Discoveries, Hudson, NH) to generate an array of ~18,000 elements. Genomic pooled normal control DNA and tumor DNA were fluorescently labeled by random priming, and hybridized as described previously (Cowell et al 2004a). Hybridizations of normal and tumor DNA were performed as sex-mismatches to provide an internal hybridization control for chromosome X and Y copy number differences. The hybridized slides were scanned using an Axon 4200a scanner to generate 10 μm resolution images for both Cy3 and Cy5 channels, and image analysis was performed using ImaGene (version 4.1) software (BioDiscovery, Inc, El Segundo, CA). Mapping information was added for each BAC using the NCBI May 2004 build (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway?org=human), and to the best of our knowledge, clones with ambiguous assignments in the databases were removed.

3 Results

3.1 SKY analysis of SRIK-NKL cells

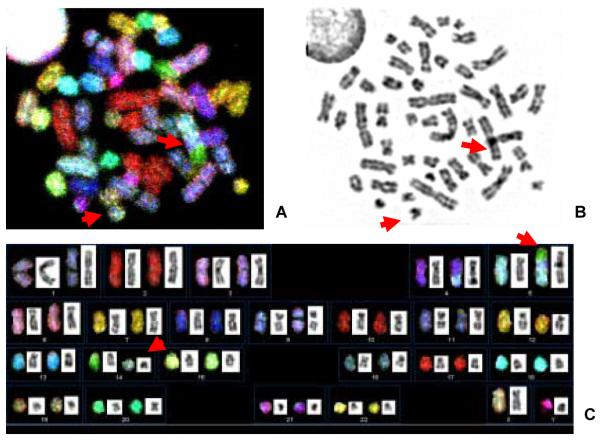

Figure 1 shows a typical SKY image as well as DAPI/G-band profile of the SRIK-NKL cell. All the cell preparations obtained from various passages contained a reciprocal translocation, rcpt(5;14)(p13.2;q11). Therefore, this rearrangement can be regarded as “constitutive” marker associated with the stem cells of this cell line. The break/fusion points were assessed by DAPI banding to be located in 5p13.2 and 14q11, respectively. There was neither numerical nor structural rearrangement of other chromosomes involving no. 7.

Figure 1.

Cytogenetic profile of SRIK-NKL cell. A. SKY image. B. DAPI/G-band. C. Combined SKY-DAPI/G-band karyotype. Arrows indicate der(5)t(5;14) and der(14) t(14;5).

3.2 Determination of break/fusion points involved in translocation t(5;14) by FISH walking with BAC probes

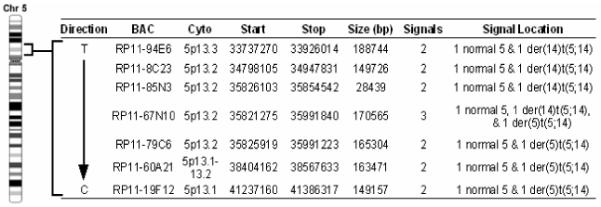

Using the DAPI-banding based assessments as approximate guides for break/fusion points, we combed through the domains spanning tens of megabases over the area corresponding to 5p and 14q breakpoints (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway) using BAC/FISH mapping (probes of 30-190 kb) (Figs. 2 and 3). As shown in Fig. 4, a 170 kb BAC RP11-67N10 produced split signals over three chromosomes: i.e. normal no. 5, one der(5)t(5;14), and one der(14)t(5;14), indicating that this BAC contains the genomic span over the breakpoint. Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate that two BAC probes (RP11-1100M7 & RP11-319H1 spanning 249 kb) gave a signal only on one normal homologue of chromosome 14 (Fig. 4), indicating a micro-deletion in the 14q fragment translocated on 5p. The BAC probe containing sequences flanking this deletion site produced FISH signals on either the der(5) or the der(14) chromosome (data not shown). These data indicate that the breakpoint on chromosome 14 lies adjacent to the micro-deletion.

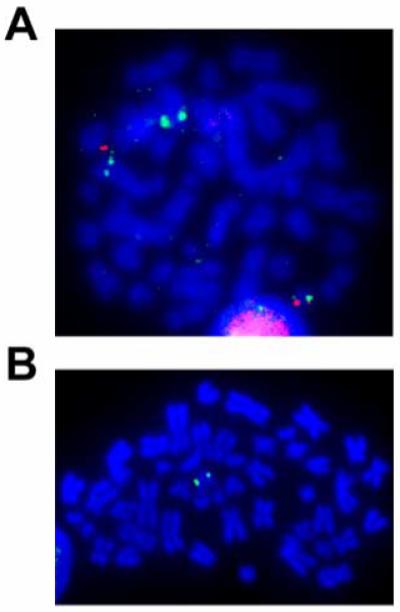

Figure 2.

Summary of the FISH analysis of the chromosome 5 breakpoint in the t(5;14) of the SRIK-NKL cells. BAC RP11-67N10 gave three signals indicating that the breakpoint lies within the span of this BAC.

Figure 3.

Summary of the FISH analysis of the chromosome 14 breakpoint in the t(5;14) of the SRIK-NKL cells. BACs RP11-1100M7 and RP11-319H1 only give 1 signal on a normal homologue of chromosome 14 indicating a micro-deletion within the region translocated on the der(5).

Figure 4.

SRIK-NKL mitosis probed by BAC/FISH using RP11-67N10 BAC (green) on chromosome 5 and BAC, RP11-14J7 on chromosome 14 (red). Notice that RP11-67N10 binds to a normal chromosome 5, the der(5)t(5;14), and the der(14)t(5;14) while RP11-14J7 binds to a normal 14 and the der(14)t(5;14). B. FISH mapping of RP11-1100M7 (green). Notice only one signal on the normal homologue of chromosome 14.

3.3 Molecular mapping of the t(5;14) translocation

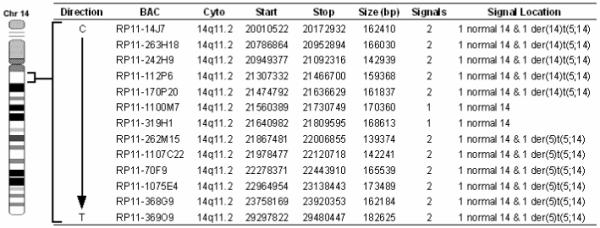

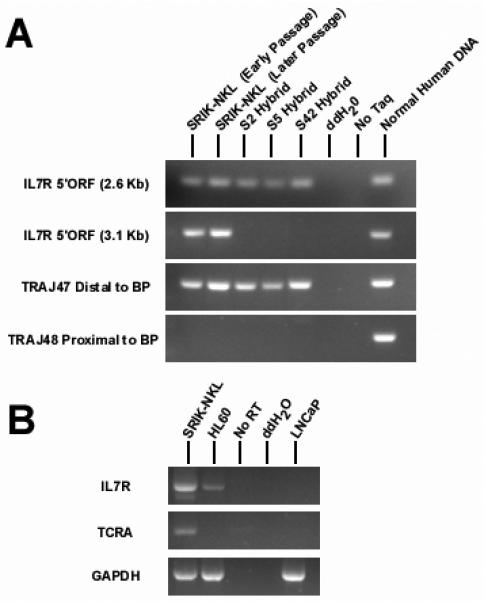

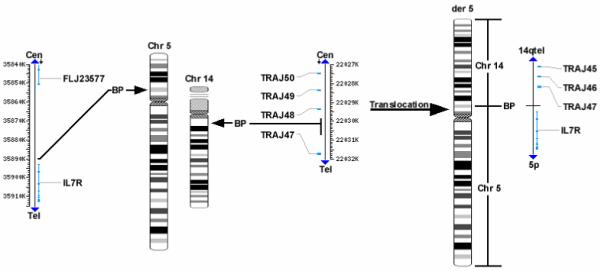

Somatic cell hybrids were mainly used to map the breakpoints of chromosomes 5 and 14 involved in the translocation. Of over thirty hybrid clones screened, none contained the derivative 14 in the absence of the normal chromosomes 5 and 14 (data not shown). Therefore, three clones containing the isolated derivative 5 but not normal nos. 5 and 14 were used to map the breakpoints. PCR results indicate that the breakpoint on no. 5 is located within a 275 bp region approximately 2,800 bp prior to the start methionine in exon 1 of the IL7R gene (Figure 5). PCR primer sequences proximal and distal to the breakpoint aligned to the component GenBank sequence AC112204 (RP11-79C6) and all observed PCR product sizes corresponded to their calculated length according to the AC112204 sequence information. We also tested for the presence of four exons (1, 4, 5 and 7) of the IL7R gene, and found that all four exons are exclusively present in the hybrid cells containing der(5) (data not shown). On the other hand, the chromosome 14 breakpoint is located within a 900 bp region between the TRAJ48 and TRAJ47 genes (Figure 6). Genomic position of the chromosome 14 breakpoint was determined by sequence alignment of PCR primer pairs to component GenBank sequences NG_001332 and AE000661. Depending on their proximity to the breakpoint, a series of primer pairs spanning TRA@J locus consistently detected the absence or presence of regions proximal or distal to the breakpoint, respectively (data not shown). NCBI mapping information indicates that BAC RP11-262M15 is contained within the AE000661 sequence, suggesting that the der(5) contains the portion of chromosome 14 distal to the interstitial deletion. These results not only confirmed that there is a deletion in no. 14 forming the t(5;14), but were also consistent with the FISH data which demonstrated that the RP11-262M15 BAC was the most proximal region of chromosome 14 contained within the derivative no. 5.

Figure 5.

Breakpoint mapping and gene expression analysis. A. PCR was used to locate the t(5;14) breakpoint from genomic DNA isolated from three somatic cell hybrids (S2, S5 and S42) containing the der(5). The chromosome 5 breakpoint was identified using two primer sets, approximately 2.6 and 3.1 kb prior to the open reading frame (ORF) of the IL7R gene. There was no evidence of chromosome 5 genetic material present in the der(5) proximal to the 3.1 Kb reverse primer, suggesting that the chromosome 5 breakpoint occurs in a 275 bp region between the PCR products obtained using the 2.6 and 3.1 kb primer sets. In the same respect, the entire distal portion of chromosome 14 including TRAJ48 is included in the der(5). This indicates that 14 breakpoint occurs within a 900 bp region between TRAJ48 and TRAJ47. B. RT-PCR was performed to access the status of IL7R and TRA@ gene expression. Both IL7R and TRA@ were expressed in the SRIN-NKL. The IL7R gene was also expressed in the AML derived HL60 cell line, but the TRA@ gene was expressed in neither the HL60 nor the prostate LNCaP cell line.

Figure 6.

Composite representation of the candidate genes involved in the t(5;14) of the CD8+NK/T cell line. The chromosome 14 deletion/translocation involves a breakpoint in the T cell receptor alpha variable region between TRAJ48 and TRAJ47. The chromosome 5 translocation breakpoint between the IL7R gene and FLJ23577 genes.

3.4 IL7R and TRA@ gene expression in SRIK-NKL cells

We addressed the question using RT-PCR if IL7R and TRA@ genes, which were on or flanking the break/fusion points of nos. 5 and 14 were expressed in SRIK-NKL cells. The HL60 (AML) and LNCaP (prostate) cell lines were used as negative controls. As shown in Figure 6B, both IL7R and TRA@ were expressed in SRIK-NKL cells. Primer pairs for TRA@ flanked the deleted region, and the intensity of the RT-PCR product suggests that only one functional TRA@ locus is present. From the intensity of the IL7R band, it appears that the translocation near the IL7R gene did not affect its transcription.

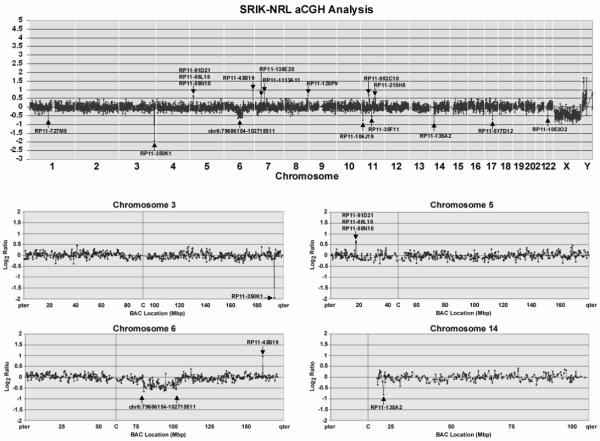

Copy number abnormalities detected by RPCI custom aCGH

As shown in Fig. 7, SRIK-NKL cells have, in addition to a specific reciprocal translocation, t(5;14), several copy number abnormalities (CNAs). These CNAs include amplification of a region 18 megabases upstream of no. 5 breakpoint and a hemizygous deletion of a 23 megabase region of 6q. Over one hundred genes map to this region, chr6:79686154-102715511 and more than twenty of these genes are listed in Table 1. Individual spikes of BACs indicating possible loss or gain of these regions were generally considered problematic because of possible mis-mapping of BACs or other technical artifacts. However, apparent loss of a region defined by a single BAC, RP11-135A2, corroborates our FISH and PCR mapping data, and, therefore, we cannot wholly discount these events. With this in mind, potential loss of chromosome 3q defined by RP11-350K1 and containing the FGF12 gene, as well as possible gain of the RP11-43B19 region of 6q containing the LPA gene is, at the very least, worthy of verification. The biological significance of such changes is not obvious, but further study of these loci may provide new insights into our understanding of NK cells.

Figure 7.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) Analysis of the SRIK-NRL Cell Line. The complete genomic profile of the SRIK-NRL cell line is shown with labeled BACs which define gain or loss of discrete chromosomal regions. Losses include a homozygous deletion of a region defined by BAC RP11-350K1 on chromosome 3 as well as hemizygous loss of a 23 megabase pair region of chromosome 6q14.1-q16.3. Several gains were also observed including a region defined by BAC RP11-43B19. We observed copy number gain of a region of 5p15.1 defined by three BACs (RP11-91D21, RP1188L18 and RP11-55N10) which is upstream of the 5p13.2 breakpoint region. Consistent with our FISH data was loss of a region of 14q defined by BAC RP11-135A2 and within the TRA@ gene.

Table 1. Genes encompassed in 6q (bps 79,686,154-102,715,511)*.

| PHIP: | Pleckstrin Homology Domain Interacting Protein |

| HMGN3: | High Mobility Group Nucleosomal Binding Domain 3 |

| BCKDHB: | Branched Chain Keto Acid Dehydrogenase E1, beta |

| IBTK: | Inhibitor of Bruton’ Tyrosine Kinase |

| ME1: | Cytosolic Malic Enzyme 1 |

| SNX14: | Sorting Nexin 14 |

| ORC3L: | Origin Recognition Complex, Subunit 3 |

| SPACA1: | Sperm Acrosome Associated 1 |

| CNR1: | Central Cannabinoid Receptor 1 |

| GABRR1: | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptor, Rho 1 |

| GABRR2: | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptor, Rho 2 |

| UBE2J1: | Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme E2, J1 |

| CASP8AP2: | Caspase 8 Associated Protein 2 |

| MAP3K7: | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase 7 |

| EPHA7: | Ephrin Receptor A7 |

| MANEA: | Mannosidase, Endo-Alpha |

| FUT 9: | Fucosyl Transferase 9 |

| FHL5: | Activator of cAMP-Responsive Element Modulator |

| POU3F2: | POU Domain, Class 3, Transcription Factor 2 |

| FBXL4: | F-Box and Leucine-Rich Repeat Protein 4 |

| CCNC: | Cyclin C |

| PRDM13: | PR Domain Containing 13 |

| SIM1: | Single Minded Homolog |

| GRIK2: | Glutamate Receptor, Ionotropic, Kainate 2 |

This is hemizygously-deleted region corresponding to 6q14.1-16.3 (see Text).

4. Discussions

In this study, we addressed ourselves to a specific question as to whether or not the bi-functional phenotype of SRIK-NKL cells [17, 18] derived from one of the ALL patients was associated with any genomic alteration which may preclude their application to future cancer therapy. We found that SRIK-NKL cells carries rept(5;14), a constitutive translocation which has not been previously found in hematological or other disorders [2, 4, 24]. Using somatic hybrids containing der(5)t(5;14) (Figs. 4 - 6), we further mapped the fusion/break points. The breakpoint on 14q11 seems to lie within TRA@ variable region (Fig. 6), the region known to be responsible for a formation of variants of the T-cell receptor genes and also that breakpoint in 5p13.2 is located within a non-coding region between 358,212 and 359,918 metric distance upstream of IL7R. Although the FISH and PCR analyses revealed an unexpected micro-deletion in 14q near the breakpoint (Figs. 3 - 6), the RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the expression of TRA@ and IL7R was not significantly affected (Fig. 5B). Thus it was obvious that the normal homologues have compensated these genes as templates for transcription.

A variety of lympho-proliferative disorders such as ALL, CLL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, malignant lymphoma, plasma cell leukemia are associated with structural rearrangements of no. 14 [25]. With major partners including nos. 1, 8, 10, 11, 14, 18 and 22 [39], the breakpoints are consistently located within TRA@ domain. Interestingly, none of these disorders containing structural rearrangements involving no. 5 has been described before [4]. Cell NK cell lines established so far are of heterogeneous origins and generally consist of aneuploid chromosome numbers [4]. The SRIK-NKL cells are most likely of T- cell lineage origin but are not of myeloid cell origin for the following grounds: First, SRIK-NKL cells have no myeloid markers [17], secondly they contain disturbed TRA@ genes as a result of translocation, rept(5;14), consistent with a consensus reached by pathological studies that 14q11 rearrangement is a specific parameter characterizing T-lineage disorders but not B-lineage [4, 24-26, 39-41]. Second, the structural rearrangements of myeloid leukemia such as AML and CML involve many chromosomes but not nos. 5 and 14. It should be also noted that balanced translocations involving 14q11 have been widely noticed in mature T and NK-cell malignancy [24, 26]. In view of these findings, we believe that SRIK-NKL cells originated from a subclone of the pluripotential cells at a very critical differentiation window when T- and B-cell phenotypes were about to branch out.

The present findings demonstrated that chromosomal rearrangements between nos. 5 and 14 shut down neither TRA@ nor IL7R (Fig. 5B). However, in view of several lines of evidence, this result alone cannot rule out the possibility that other genes near the breakpoints, which may be crucial for determining unique phenotypes of SRIK-NKL cells, are up- or down-regulated by this rearrangement. For example, The “classical t(14;18) rearrangement involving the BCL2 gene on chr. 18 as seen in the majority of follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas involve the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH) on chromosome 14q32, even though a rare case of translocation t(11;14)(14q11) was reported in some T-cell tumors which apparently caused relocation of TRA@ locus (ref. 39). Furthermore, there is ample evidence which implicates the role of genes around the flanking region of the break/fusion points in distinct phenotypes of many hematological disorders [4, 26-29, 41]. For examples, 5p13 deletion is one of the most common regions emerging in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphoblastic lymphoma, acute monoblastic leukemia, acute myleoblastic leukemia with maturation, acute myeloid leukemia, adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, etc [4, 24, 25, 41-45]. Despite a strong implication for genes located in 5p, the molecular mechanisms underlying their deregulation in these characteristic disorders still remain unknown. The rearrangements of no. 7 also occur very frequently concomitant with disruption of TRB@ genes in ALL carrying t(7;9) and such rearrangements activates oncogenes positioned near the breakpoints [26-29]. For the same reasons, the micro-deletion of genes in 14q, as detected in der(5), would result in de-regulation of the neighboring genes located on 5p if the disruption of these genes activated highly potent promoter motifs. As a matter of fact, the recent studies demonstrated that the genomic imbalance associated with the change of chromosome copy numbers could result in complex deregulation of gene expression in immortalized cells [37], and also that the regional imbalance resulting in higher or lower copy numbers of certain genes could induce disturbed regulation of phenotypes in general. Thus, a conclusive answer about the role of rept(5;14) and micro-deletion in the expression of unique SRIK-NKL phenotypes has to await further analysis of genes located in 5p13, e.g. a gene termed FLJ23577 located upstream of IL7R and two genes termed MGC26610 and FLJ34658 located downstream of IL7R (Fig. 8). Similarly, as discussed under RESULTS, CNAs as detected by CGH, particularly the detection of a 23 megabase region of no. 6 may have profound implications, the significance of which is not presently obvious and would require further work.

The majority of NK leukemia and lymphomas as well as the established NK cell lines, such as KHYG-1, NK-92, NKL, YT, are composed of highly heterogeneous aneuploid cells [4, 45-48]. These NK cell lines usually contain random chromosome rearrangements which differ from one cell to another. Thus, it remains difficult to assess and pinpoint precisely their inherent genetic phenotypes. By contrast, a constitutive rept(5;14) is the only chromosomal rearrangement found in SRIK-NKL which has been maintained throughout many culture passages. The genomic stability of this cell line is a strong advantage considering the potential clinical application utilizing its NK ability to purge malignant cells.

Acknowledgments

This work supported by a grant from Charles W. McCatchen Foundation and in part by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant CA 16056 and Roswell Park Alliance Foundation.

Footnotes

Current Address: Department of Genetics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520-8005

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1.].Jonges LE, Albertson P, VanVlierberghe RLP, Ensink NG, Johanson BR, VanDevelde CJH, et al. The phenotypic heterogeneity of human natural killer cells: Presence of at least 48 different subsets in the peripheral blood. Scand J. Immunol. 2001;53:103–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2.].Greer JP, Kinney MC, Loughran TP., Jr. B-cell and NK cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Hematology. Am. Soc. Hematology Euro. Program. 2003;1001:259–81. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2001.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3.].Sivori S, Cantoni C, Prolini S, Marcenaro E, Conte R, Moretta L, et al. IL-21 induces both rapid maturation of human CD34+ cell precursors towards NK cells and acquisition of surface killer Ig-like receptors. Euro. J. Immunol. 2003;33:3439–47. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4.].Drexler HG. Guide to Leukemia-Lymphoma Cell Lines. Braunschweig: 2005. For a CD with PDF file, please write to Dr. Drexler HG, is hdr@dsmz.de. [Google Scholar]

- [5.].Pessino A, Sivori S, Bottino C, Malasspina A, Morelli L, Moretta L, et al. Molecular cloning of NKp46: a novel member of the immunoglobulin super family involved in triggering of natural cytotoxicity. J Exp. Med. 1998;188:955–960. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6.].Cantoni C, Bottino C, Vatale M, Pessino A, Augualiaro R, Malaspina A, et al. NKp44, a triggering receptor involved in tumor cell lysis by activated human natural killer cells, ks a novel member of the immunoglobulin super family. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:785–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7.].Pende D, Paronini S, Pessino A, Sivori S, Augualiar R, Morelli L, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of NKp30, a novel triggering receptor involved in natural cytotoxicity mediated by human natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1505–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8.].Ferlazzo G, Thomas D, Lin S, Goodman K, Morandi B, Muller WA, et al. The abundant NK cells in human secondary lymphoid tissue require activation to express killer cell Ig-like receptors and become cytolytic. J. Immunol. 2004;172:1455–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9.].Koopman LA, Kopenow HD, Rybalow B, Boyson JE, Orange JS, Schatz F, et al. Human decidual national killer cells are a unique NK cell subset with immunomodulatory potential. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1201–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10.].Leon F, Roldan E, Sanchez L, Lamarero C, Bootello A, Roy G. Human small intestinal epithelium contains functional natural killer lymphocytes. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:345–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11.].Roszkowski JJ, Lyons GE, Martin Kast W, Yee C, Van Besien K, Nishimura MI. Simultaneous generation of CR8+ and CD4+ melanoma-reactive T cells by retroviral-mediated transfer of a single T-cell receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1570–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12.].Clay TM, Custer MC, Sachs J, Hsu P, Rosenberg SA, Nishimura MI. Efficient transfer of a tumor antigen-reactive TRA@ to human peripheral blood lymphocytes confers anti-tumor reactivity. J. Immunol. 1999;163:501–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13.].Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:666–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14.].Matsuo Y, Drexler HG. Immunoprofiling of cell lines derived from natural killer cell and natural killer-like T-cell leukemia lymphoma. Leuk. Res. 2003;27:935–45. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15.].Drexler HG, Matsuo Y. Malignant hematopoietic cell lines: in vitro models for the study of natural killer cell leukemia-lymphoma. Leuk. Res. 2002;14:777–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16.].Wong KF. Genetic changes in natural killer cell neoplasms. Leuk. Res. 26:977–78. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17.].Srivastava BIS, Srivastava MD. Establishment and characterization of SRIK-NKL; A novel CD8+ natural killer/T cell line derived from a patient with leukemic phase of acute lymphoblastic lymphoma. Leuk. Res. 2005;29:771–83. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18.].Srivastava MD, Srivastava BIS. Expression of mRNA and proteins for toll-like receptors, associated molecules, defensins and LL-37 by SRIK/NKL, a CD8+ NK/T cell line. Leuk. Res. 2005;29:813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19.].Snijders AM, Nowak N, Segraves R, Blackwood S, Brown N, Conroy J. Assembly of microarrays for genome-wide measurement of DNA copy number by CGH. Nat. Genet. 2006;29:263–4. doi: 10.1038/ng754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20.].Chernova OB, Huyadi A, Malaj E, Pan H, Crooks C, Roe B, et al. A novel member of the WD-repeat gene family, WDR11, maps to the 10q26 region and is disrupted by a chromosome translocation in human glioblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:5378–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21.].Le Bean MM, Pettenatti MJ, Lemons RS, Diza MO, Westbrook CA, Larson RA. Assignment of GM-CSF, CSF-1, and FMS genes to human chromosome 5 provides evidence for linkage of a family of genes regulating hematopoiesis and for their involvement in the deletion (5q) in myeloid disorders. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1986;51:899–909. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22.].Rowley JD. Human oncogene locations and chromosome aberrations. Nature. 1983;301:290–1. doi: 10.1038/301290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23.].Still IH, Chervona O, Hurd D, Stone RM, Cowell JK. Molecular characterization of the t(8;13)(p11;q12) translocation associated with an atypical myeloproliferative disorder: evidence for three discrete loci involved in myeloid leukemias on 8p11. Blood. 1997;90:3136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24.]. http://www.infobiogen.fr/services/chromcancer/index.html.

- [25.]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=cancerchromosomes.

- [26.].Raimondi SC, Behm FG, Robertson PK, Pui C-H, Rivera GK, Murphy SB, Williams DL. Cytogenetics of childhood T-cell leukemia. Blood. 1988;72:1560–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27.].Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynods TC, Smith SD, et al. TAN-1, the human homologue of the Drosophila Notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66:649–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28.].Burnett RC, David J-C, Harden AM, Le Beau MM, Rowley JD, Diaz MO. The LCK gene is involved in the t(1;7)(p34;q34) in the T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia derived cell line, HSB-2. Genes Chrom. & Cancer. 1991;3:461–7. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870030608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29.].Fitzgeral TJ, Neale GAM, Raimondi SC, Boorha RM. c-tal, a helix-loop helix protein, is juxtaposed to the T-cell receptor- chain gene by a reciprocal chromosomal translocation: t(1;7)(p32;q35) Blood. 1991;78:2686–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30.].Washington SS, Bowecock AM, Gerke N, Matsunami N, Lesh D, Osbourne-Lawrence SL, et al. A somatic cell hybrid map of human chromosome 13. Genomics. 1994;18:486–95. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(11)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31.].Roberts T, Mead RS, Cowell JK. Characterization of a human chromosome 1 somatic cell hybrid mapping panel and regional assignment of 6 novel STS. Ann. Hum. Genet. 1996 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1996.tb00424.x. 60-213-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32.].Pontecorvo G. Production of mammalian somatic cell hybrids by means of polyethylene glycol treatment. Somatic Cell Genet. 1975;4:397–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01538671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33.].Kelsell DP, Rooke L, Warne D, Bouzyk M, Cullin L, Cox R. Development of a panel of monochromosomal somatic cell hybrids for rapid gene mapping. Ann Hum Genet. 1995;59:233–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1995.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34.].Ried T, Koehler M, Padilla-Nash H, Schroek E. Chromosome analysis by spectral Karyotyping. In: Spector DL, Goldman RD, Leinwand LA, editors. Cells: a laboratory manual. CSHL Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [35.].Chernova O, Cowell JK. Molecular definition of chromosome translocations involving 10q24 and 1913 in human malignant glioma cells. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1998;105:60–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36.].Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Edition Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [37.].Cowell JK, Matsui SI, Wang J, LaDuca J, Conroy J, McQuaid D, et al. Application of comparative genome hybridization using BAC arrays (CGHa) and spectral karyotyping (SKY) to the analysis of glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;151:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38.].Rossi MR, Conroy J, McQuaid D, Nowak NJ, Rutka JT, Cowell JK. An array CGH analysis of pediatric medulloblastomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:180–303. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39.].Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Word Health Organization Classification of tumors. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2001. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. [Google Scholar]

- [40.].Heim S, Mitelman F. Cancer cytogenetics: Chromosomal and molecular genetic aberrations of tumor cells. 2ed Edition Wiley-Liss, Inc.; NY: [Google Scholar]

- [41.].Croce CM, Erikson J, Haluska FG, Finger LR, Showe LC, Tsujimoto Y. Molecular genetics of human B- and T-cell neoplasia. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1986;51(Pt2):891–898. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42.].Sandberg AA. The chromosomes in human cancer and leukemia. 2nd edition Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc.; NY, Amsterdam and Oxford: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [43.].Tie HF, Su U, Tang JL, Lei MC, Lee FY, Chen YC, et al. Cloncal chromosomal abnormalities as direct evidence for clonality in nasal T/NK cell lymphomas. Br. J. Haematol. 1997;97:621–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.752711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44.].Upender MB, Habermann JK, McShane LM, Korn EL, CariBarrett J, Difilippantonia MJ, et al. Chromosome transfer induced aneuploidy results in complex dysregulation of the cellular transcriptome in immobilized and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6941–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45.].Wong N, Wong KF, Chan JK, Johnson PJ. Chromosomal translocations are common in NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia as shown by spectral Karyotyping. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31:771–4. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.7625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46.].MacLeod RAF, Nagel S, Kaufmann M, Grulich-Bode K, Drexler HG. Multicolor FISH analysis of a natural killer cell line (NK-92) Leuk. Res. 2002;26:1027–33. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47.].Wong N, Zhang YM, Chan JK. Cytogenetic abnormalities in NK cell lymphoma/leukemia is there a consistent pattern: Leuk. Lymphoma. 1999;34:241–50. doi: 10.3109/10428199909050949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48.].Wong KF, Chan JK, Kwong YL. Identification of del(6)(q21q25) as a recurring chromosomal abnormality in putative NK cell lymphoma/leukemia. Br. J. Haematol. 1997;98:922–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3223139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]