Abstract

Forty years after the discovery by Marshal R. Urist of a substance in bone matrix that has inductive properties for the development of bone and cartilage, there are now 15 individual human bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) that possess varying degrees of inductive activities. Two of these, BMP-2 and BMP-7, have become the subject of extensive research aimed at developing therapeutic strategies for the restoration and treatment of skeletal conditions. This has led to three different therapeutic preparations, each for a distinct clinical application. Non-union, open tibial fractures and spinal fusions are the three conditions for which there is clinical approval for use of BMPs. This article reviews the evidence supporting the therapeutic applications of BMPs as they are presently available and suggests future applications based on current research. Among the future directions discussed are percutaneous injections, protein carriers, advances in gene transfer technology and the use of BMPs to engineer the regeneration of skeletal parts.

Résumé

Quarante ans après la découverte par R. Marshal Urist d’une substance de la matrice osseuse ayant des propriétés d’induction du développement osseux et cartilagineux ont été recensés 15 types de BMP, avec des degrés variables de propriétés inductives. Deux d’entre-elles, la BMP2 et la BMP7 ont fait l’objet de recherches importantes et de développements dans des stratégies thérapeutiques de façon à restaurer de bonnes conditions osseuses et ont conduites à trois différentes préparations thérapeutiques pour des indications bien précises: qu’il s’agisse de pseudarthroses, de fractures ouvertes du tibia ou d’arthrodèses vertébrales. Ce travail passe en revue ces applications thérapeutiques et suggère de nouvelles applications basées sur les recherches actuelles. Parmi les différentes possibilités de recherches, sont discutées les injections percutanées, les protéines de transport, les technologies de transfert génique et les possibilité de régénération osseuse par les BMP.

Introduction

It is estimated that approximately 7.9 million fractures are sustained in the United States each year, with 5–10% resulting in delayed or impaired healing [11]. Trauma is the second most expensive medical problem in the US, after heart conditions, and costs the health care system $56 billion per year, of which nearly half is used for the treatment of broken bones alone [12]. Approximately 1.5 million bone grafting operations are performed annually in the United States [4]. These procedures are performed to enhance the healing of spinal fusions, bone defects, fractures of the long bones and to augment skeletal reconstruction in the treatment of maxillofacial injuries and conditions. Because of the well-established osteogenic properties and compliment of live cells present in these grafts, autologous bone remains the preferred material for these procedures. However, the harvesting of autologous bone is associated with increased postoperative pain, increased intra-operative blood loss and extended operative time. In addition, complications such as injury to sensory or motor nerves, major blood vessel injury, hematoma, infection and postoperative gait disturbances may occur after these procedures. The development of a readily available graft material could limit the need for harvesting autologous bone and represent a potential major advance in the treatment of skeletal conditions.

Overview of current materials and technologies

Autologous bone graft is known to possess osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties. Osteoconduction is a process that supports the ingrowth of capillaries, perivascular tissue and osteoprogenitor cells into the three-dimensional structure of the implant graft [21]. Autologous bone graft possesses substantial osteoconductive properties as a result of its architecture, chemical composition and surface charge. Synthetic osteoconductive materials (e.g., calcium phosphate, calcium sulphate, calcium hydroxyapatite and collagen-calcium phosphate composites) attempt to mimic these properties [7]. Osteoinduction is a process that supports the proliferation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and the formation of osteoprogenitor cells with the capacity to form bone [21]. It is the osteoinductive properties of autologous bone graft that distinguish it from synthetic osteoconductive bone graft substitutes.

Other materials such as combinations of allogeneic bone and autologous bone marrow have been used to manage non-union and skeletal defects; however, their efficacy is less than that of autologous bone alone [7]. Human demineralised bone matrix (DBM) is currently commercially available, but when used alone has failed to demonstrate equivalent efficacy to autologous bone [7]. A recent retrospective study of 41 non-unions treated with Allomatrix (DBM plus CaSO4) also showed high rates of wound drainage, infection and treatment failure [24].

Tissue repair factors such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factors (IGF) or growth hormone (GH) are under investigation for their potential roles in the enhancement of musculoskeletal tissue healing. Theses signalling molecules have been shown to promote cell proliferation and differentiation in in-vitro systems and to enhance skeletal repair in animal models. However, none have true inductive properties and therefore are not mitogenic for undifferentiated stem cells.

Two BMPs are currently available for clinical applications, recombinant human BMP-2 [rhBMP-2, (InFUSE); Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN] and rhBMP-7, [osteogenic protein 1 (OP-1); Stryker Biotech, Hopkinton, MA]. Both are manufactured by a process involving mammalian cell expression. Three clinical trials have supported the use of these recombinant BMPs [1, 3, 8]. These have led to various regulatory agency approvals for specific indications in the United States, Europe and several other countries.

Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 for the treatment of tibial non-unions was investigated by Friedlaender et al. [8]. In a prospective, randomised clinical trial of tibial non-unions, they showed that rhBMP-7 (OP-1) and autograft were comparable by several clinical outcome parameters, however the morbidity and pain associated with surgical harvesting of autologous bone graft was eliminated. It was concluded that OP-1 implanted with a type-I collage carrier is a safe and effective treatment for tibial non-unions. On the basis of these data, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a ‘Humanitarian Device Exemption’ for the application of the OP-1 implant as an alternative to autograft in recalcitrant long bone non-unions where use of autograft is unfeasible and alternative treatment has failed. Multiple clinical examples of resistant tibial non-unions treated with rhBMP-7 have been described [13, 14]. Figure 1 shows an example of BMP-7 in the treatment of an insulin-dependent diabetic 40-year-old woman with a 10-month-old, infected, supracondylar femoral non-union. She had previously undergone irrigation, debridement and open reduction and internal fixation followed by allogeneic bone grafting and supplementation with demineralised bone matrix (Fig. 1a through f). Pecina et al. [14] described a patient that had failed treatment of a tibial non-union for 14 years that went on to heal using BMP-7, iliac bone marrow cells and Ilizarov external fixator.

Fig. 1.

a–f Use of OP-1 in the treatment of a 10-month-old, infected, supracondylar femoral non-union in a 40-year-old woman with insulin-dependent diabetes who had undergone prior irrigation, debridement and open reduction and internal fixation followed by allogeneic bone grafting and supplementation with demineralised bone matrix. The presence of drains in the preoperative radiographs indicate recent surgical efforts to manage the wound infection. Preoperative antero-posterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs showing no evidence of union. Immediate postoperative anteroposterior (c) and lateral (d) radiographs showing implantation of allogeneic bone chips in combination with demineralised bone matrix and OP-1. Anteroposterior (e) and lateral (f) radiographs, made 3 months postoperatively, showing healing of the non-union. (Radiographs courtesy of Paul Tornetta III, Boston University Medical Center)

Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) for treatment of open tibial fractures was investigated by the BESTT trial (the BMP-2 Evaluation in Surgery for Tibial Trauma) [1] and a subgroup analysis by Swiontkowski et al. [19]. The BESTT study [1] was a prospective randomised trial of 450 patients with open tibial shaft fractures treated with initial irrigation and debridement followed by fixation with a statically locked intramedullary nail at the time of wound closure (so-called standard of care) or standard of care plus different concentrations rhBMP-2. This showed that compared with patients treated with standard of care, those treated with 1.50 mg/kg rhBMP-2 had fewer hardware failures, fewer infections and faster wound healing [1]. Swiontkowski et al. [19] in 2006 performed a subgroup analysis from two prospective randomised studies observing two subgroups. Group 1 had Gustilo-Andersen type-IIIA or III-B open tibial fractures, and group 2 was treated with reamed intramedullary nailing. Group 1 demonstrated significant improvements in the rhBMP-2-treated patients with fewer bone-grafting procedures, fewer interventions and a lower rate of infection compared with controls. Group 2 showed no differences between rhBMP-2 treated patients and controls. This led the authors to conclude that the addition of rhBMP-2 to the treatment of type-III open fractures can significantly reduce the frequency of bone-grafting procedures and other secondary interventions [19].

Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 has also been tested in clinical settings in single-level interbody fusion of the lumbar spine. In a prospective, randomised, non-blinded, 2-year multi-centre study, 279 patients with degenerative lumbar disc disease who had anterior interbody fusion with the use of two tapered threaded fusion cages were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The investigational group of 143 patients received rhBMP-2 on an absorbable collagen sponge and a control group of 136 patients received autogenous iliac-crest bone graft. Plain radiographs and computed tomography scans were used to evaluate fusion at 6, 12 and 24 months after surgery. The results showed that the mean operative time and blood loss were less in the BMP-treated group, and the fusion rate at 24 months was higher for the BMP-treated group compared with that for controls, 94.5% compared with 88.7%, respectively. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability score and the neurological status improved in both groups with similar outcomes. The control group had eight adverse events related to the harvesting of iliac-crest bone graft, and new bone formation was noted in all patients treated with BMP [3].

Percutaneous injections

Pre-clinical and clinical studies have shown the utility of BMPs in open surgical applications. However, the ability to inject this osteoinductive factor could have many clinical advantages such as in the percutaneous treatment of delayed and non-unions, minimally invasive spinal fusion and accelerated healing closed fractures. In a femoral fracture model in rats, a single, local, percutaneous injection of rhBMP-2 was shown to accelerate fracture healing [6]. The strength of the BMP-injected calluses was 34% greater than buffered solvent-injected controls at 3 weeks (p < 0.03) and was 60–70% higher at 4 weeks (p < 0.005). At 4 weeks, the stiffness and strength were equivalent to the unfractured contralateral femora. The stiffness of the BMP-injected calluses was twice that of both control groups from 2 to 4 weeks after fracture.

BMPs are soluble, local-acting differentiation factors, and if delivery is in a buffer solvent, its clearance is rapid. A protein carrier helps to maintain the concentration of rhBMP at the repair site for a longer period of time, possibly enhancing its inductive effects. In some cases, the carrier can provide an osteoconductive matrix. Calcium phosphate paste [alpha bone substitute material (α-BSM); ETEX, Cambridge, MA] in combination with rhBMP-2 has been shown to accelerate bone healing and result in torsional mechanical properties equivalent to those of normal bone. In a non-human primate model of fibular osteotomy healing, a single percutaneous injection of rhBMP-2/α-BSM accelerated bone healing by approximately 40% [15]. Further studies have indicated that the addition of 20% sodium bicarbonate (by weight) to the calcium phosphate cement [calcium phosphate matrix (CPM)] resulted in the most consistent granulation and dispersion of the protein and led to the most consistent radiographic healing. Using a non-human primate fibular osteotomy model, a single percutaneous injection of rhBMP-2/CPM accelerated healing over a wide range of concentrations and treatment times from 3 h to 2 weeks. Delaying treatment for 1 week further accelerated healing because of an increase in the number of responding cells and an increase in the direct bone formation [16]. A phase-1 clinical trial is evaluating single percutaneous injection at varying doses of rhBMP-2/CPM in patients with closed diaphyseal fractures treated with a reamed statically locked intramedullary nail.

The future of BMPs

Preclinical animal studies have demonstrated a robust response to fracture healing in the presence of BMPs. However, while results of human clinical trials have shown equivalence to or improvement over autologous bone grafting in specific applications, lack of as robust a response as is seen in animal models raises questions regarding how much more clinical responsiveness should be achieved with BMPs. Moreover, the effective doses of BMP required in humans are very high as compared to smaller animals. For example, 1 kg of human bone yields 1 µg of BMP. One vial of OP-1 (rhBMP-7) contains 3.5 mg, and this amount is equivalent to all the BMP-7 in the entire skeletons of two people.

One possible explanation for the requirement for such high doses of BMPs in humans may relate to a less responsive BMP signalling pathway compared with animals. However, using immunohistochemistry, Kloen et al. [10] demonstrated the presence of normal BMP signalling components in callus from human fractures (malunions undergoing reoperation). They demonstrated the presence of BMPs −2, −3, −4 and- 7; their receptors, BMPR-IA, -IB and -II; and the phosphorylated receptor-regulated SMADs. Thus, BMP signalling is completely normal and operational in humans. Yet despite having all of the components for BMP signalling, the regulation of BMP functions differently in humans. This was demonstrated by Diefenderfer et al. [5] who, using cultures of bone marrow stromal cells from patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, showed that despite normal BMP signalling, bone formation in humans is not responsive to BMP. Using alkaline phosphatase activity as a marker for bone formation, these investigators found that BMPs −2, −4 and −7 induced expression of other osteogenic genes such as bone sialoprotein (BSP) and osteopontin, as well as BMP-2 and noggin. However, in order to see increased alkaline phosphatase activity, dexamethasone was required, and this response was only seen in half the cultures. Interestingly, a greater response was seen in male subjects. By comparison, cells cultured from rats and mice showed reproducible alkaline phosphatase expression and bone formation upon stimulation with BMP alone. Thus, the mechanism by which BMPs modulate alkaline phosphatase induction is presumably indirect, involving a BMP-regulated transcription factor that is controlled differently in rodents and humans.

Although the current limitations of human responsiveness to BMPs are poorly understood, rapid clearance of the proteins, too short a resident time in tissues and an insufficient number of responding cells are possible causes. With regard to clearance and tissue exposure, this may be corrected with improved delivery involving strategies for sustained release of theses proteins. In addition, advances in gene transfer technology provide an opportunity to deliver complementary DNAs (cDNAs) that can encode osteogenic proteins rather than delivering the proteins themselves. Using this strategy, it is possible to achieve a sustained, local presence of the growth factor at efficacious concentrations with minimal exposure of non-target sites. The growth factor is synthesised in situ, undergoes normal posttranslational processing and is presented to the surrounding tissues in a natural cell manner.

Healing of segmental bone defects can be induced experimentally with genetically modified osteoprogenitor cells, an ex vivo strategy that requires two operative interventions and substantial cost. Direct transfer of osteogenic genes offers an alternate, clinically expeditious approach that is simpler, faster and less invasive. This approach is compatible with the use of recombinant, first-generation adenovirus vectors that are straightforward to produce and very efficient. Betz et al. [2] used direct percutaneous gene delivery to enhance the healing of segmental, critical-size bone defects in the rat model. Forty-eight male rats with critical midfemoral defect were created and stabilised with an external fixator. After 24 h, each received a single intralesional percutaneous injection of adenovirus carrying human BMP-2 cDNA (Ad.BMP-2), or luciferase cDNA(Ad.luc.) or remained untreated. At 8 weeks a single percutaneous, intralesional injection of Ad.BMP-2 induced healing. Thus, direct administration of adenovirus carrying BMP-2 could provide a straightforward, cost effective treatment for large osseous defects with adequate surrounding soft tissue support.

A potential clue to the enhancement of human host responsiveness may lie in an understanding of the pathogenesis of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), a heritable disorder of connective tissue characterised by formation of ectopic bone. Investigation of this disorder has generated a human clinical model of over-expression of BMPs causing excessive osteogenesis. A study by Shafritz et al. [17] showed that BMP-4 is expressed in the lymphocytes of 26/32 patients with FOP and only 1/12 of normal subjects. More recently, these investigators have shown that treatment of cells from normal subjects with rhBMP-4 upregulates noggin expression, but this response is attenuated in cells from patients with FOP, indicating loss of a negative feedback loop. Additionally, a recurrent mutation in the BMP type-I receptor (ACVR1) can cause inherited and sporadic FOP. Linkage analysis in five families with well-defined FOP led to the characterisation of a mutation in activin receptor-like kinase (Alk-2), also called the activin receptor type I (ACVR1). BMP action involves its binding to type II receptors that then activate (phosphorylate) type-I receptors with the subsequent activation of intracellular signalling proteins called Smads and the regulation of target genes. Alk-2 is one such type I receptor. The ACVR1 617G to A mutation in codon 206 causes an amino acid change (histidine is substituted for arginine) in this receptor, resulting in uninhibited receptor activity. How this mutation specifically disrupts BMP signalling is unknown, but could involve dysregulation of BMP receptor internalisation and/or activation of downstream signalling. Constitutive activation of ACVR1 induces alkaline phosphatase activity in C2C12 cells, up regulates BMP4, down regulates BMP antagonists, expands cartilage elements, induces ectopic chondrogenesis, osteogenesis and joint fusion seen in FOP [18]. These findings suggest bone growth could be regulated through ACVR1, a BMP-type receptor. Further studies may determine the regulation of this receptor and allow for pharmacological agents to stimulate bone growth.

Tissue engineering using BMPs

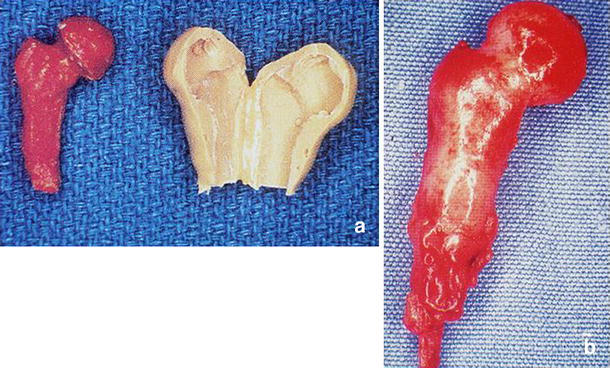

The use of BMPs to engineer the regeneration of skeletal parts is in its infancy. Khouri et al. [9] were able to transform mesenchymal tissue into bone with BMP-3 and demineralised bone matrix. In a rat model, the adductor magnus muscle was placed inside a bivalved silicone rubber mould on the pedicle of the femoral artery. The mould was in the shape of a proximal femur. Prior to closure of the mould, the experimental group was injected with osteogenin (BMP-3) and the mould coated with demineralised bone matrix. Moulds in the control group were injected with vehicle alone. The moulds were harvested at 10 days. The control flaps consisted of intact muscle without any evidence of tissue transformation, whereas the flaps treated with osteogenin and demineralised bone matrix were entirely transformed into cancellous bone that matched the exact shape of the mould (Fig. 2a and b). The clinical relevance of this report is demonstration of the ability to produce vascularised bone grafts, as needed, in predetermined anatomical shapes that are ready for microvascular transfer and anastomosis.

Fig. 2.

a–b Mould of a rat femur cast using inert silicone rubber and bivalved to allow placement of the muscle flap (a). Resultant bone in the shape of a femoral head obtained following removal for the mould 10 days later (b). Note the femoral vessel pedicle at the inferior portion of the flap [9]

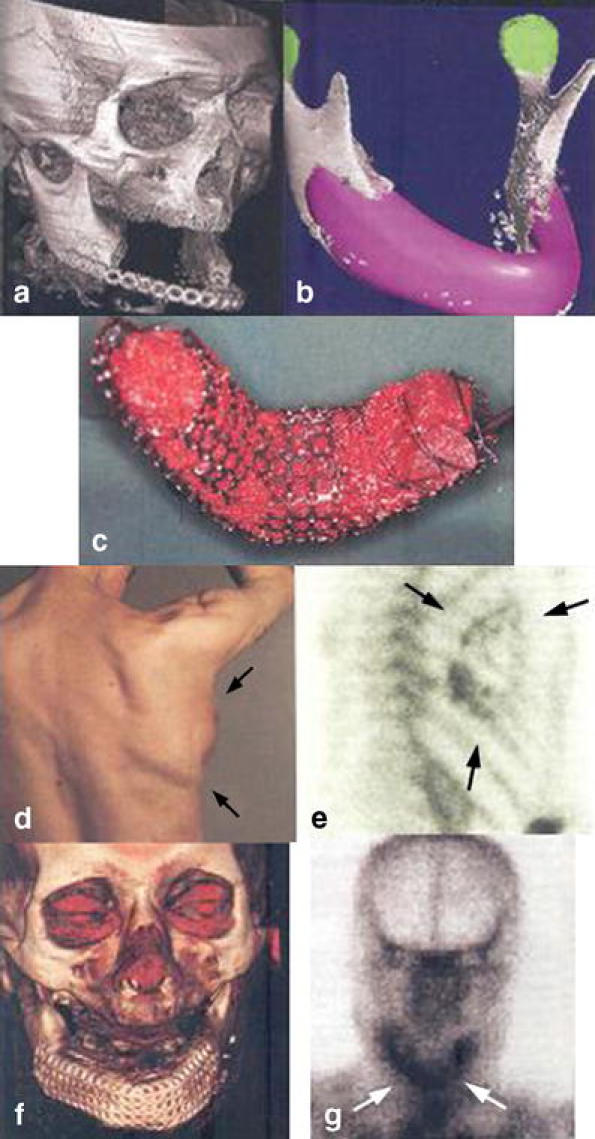

Warnke et al. [22] were the first to actually demonstrate the concept of BMP-induced vascularised bone regeneration in humans. A man who had undergone a subtotal manibulectomy 8 years previously was able to undergo mandibular reconstruction with a de novo mandibular segment. Three-dimensional CT imaging and computer-assisted design techniques were used to produce a virtual replacement for a 7-cm mandibular defect (Fig. 3a and b). A titanium mesh cage that was constructed in the shape of the defect was filled with bone mineral blocks, 20 ml of the patient’s bone marrow and infiltrated with 7-mg rhBMP-7 (Fig. 3c). The construction was implanted into the latissimus dorsi muscle on the vascular pedicle of the thoracodorsal artery. Seven weeks later, a free vascularised bone-muscle flap was transferred and anastomosed to repair the mandibular defect (Fig. 3f and g). The patient was pleased with the cosmetic result, but even more pleased to be able to perform real mastication after 8 years of a liquid/ soft food diet.

Fig. 3.

a–g Three-dimensional CT scan of size defect (a) and CAD plan of ideal mandibular transplant (b). Titanium cage filled with bone mineral block infiltrated with recombinant human BMP7 and bone-marrow mixture (c). Dorsal view of mandibular replacement 3 weeks after implantation (d). Skeletal scintigraphy of implant (e). Three-dimensional CT scan after transplantation of the bone replacement with enhancement of soft tissue (f) and repeat skeletal (g) scintigraphy with tracer enhancement showing continued bone remodelling and mineralisation (arrows) [22]

Conclusions

BMPs have been shown in preclinical and clinical studies to enhance bone healing. However, the effects of BMPs in clinical studies have only displayed safety and efficacy equivalent to autologous bone graft without the same robust response that is seen in laboratory animals. The reason for this is still under investigation, and future studies must be targeted at this unmet need to enhance human host responsiveness. However, while research should continue to focus on improving the use of BMPs in the current clinical applications, the ability to engineer bone and restore injured or diseased skeletal tissues represents a unique opportunity for BMPs in the future.

Acknowledgements

Paul Tornetta III.

Contributor Information

Gavin B. Bishop, Phone: +1-617-4141663, FAX: +1-617-4141661, Email: gavin.bishop@bmc.org

Thomas A. Einhorn, Phone: +1-617-6388939, FAX: +1-617-6388493, Email: thomas.einhorn@bmc.org

References

- 1.The BMP-2 Evaluation in Surgery for Tibial Trauma (BESTT) Study Group; Govender S, Csimma C, Genant HK, Valentin-Orpan A (2002) Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 for treatment of open tibial fractures: a prospective, controlled, randomized study of 450 patients. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 84-A:2123–2134 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Betz OB, Betz VM, Nazarian A, Pilapil CG, Vrahas MS, Bouxsein ML, Gerstenfeild LC, Einhorn TA, Evans CH (2006) Direct percutaneous gene delivery to enhance healing of segmental bone defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:355–365 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Burkus JK, Transfeldt EE, Kitchel SH, Watkins RG, Balderston RA (2002) Clinical and radiographic outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine 27:2396–2408 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Deutche Banc, Alex Brown (2001) Estimates and company information. February

- 5.Diefenderfer DL, Osyczka AM, Garino JP, Leboy PS (2003) Regulation of BMP-induced transcription in cultured human bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 85-A:19–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Einhorn TA, Majeska RJ, Mohaideen A, Kagel EM, Bouxsein ML, Turek TJ, Wozney JM (2003) A single percutaneous injection of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 accelerates fracture repair. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 85-A:1425–1435 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Finkemeier CG (2002) Bone-grafting and bone graft substitute. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 84-A:454–464 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Friedlaender GE, Perry CR, Cole JD, Cook SD, Cierny G, Muschler GF, Zych GA, Calhoun JH, LaForte AJ, Yin S (2001) Osteogenic protein-1 (bone morphogenetic protein-7) in the treatment of tibial nonunions. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 83-A:151–158 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Khouri RK, Koudsi B, Reddi H (1991) Tissue transformation into bone in vivo. A potential practical application. JAMA 266:1953–1955 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kloen P, Di Paola M, Borens O, Richmond J, Perino G, Helfet DL, Goumans MJ (2003) BMP signaling components are expressed in human fracture callus. Bone 33:362–371 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Musculoskeletal injuries report: incidence, risk factors and prevention. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (2000) researchinfo@aaos.org

- 12.National Trauma Data Bank Report (2002) The American College of Surgeons

- 13.Pecina M, Giltaij LR, Vukicevic S (2001) Orthopaedic applications of osteogenic protein-1 (BMP-7). Int Orthop 25:203–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pecina M, Haspl M, Jelic M, Vukicevic S (2003) Repair of a resistant tibia non-union with a recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-7 (rh-BMP-7). Int Orthop 27:320–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Seeherman HJ, Bouxsein ML, Kim H, Li R, Li XJ, Aiolova M, Wozney JM (2004) Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 delivered in an injectable calcium phosphate paste accelerates osteotomy-site healing in a nonhuman primate model. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 86-A:1961–1972 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Seeherman HJ, Li R, Bouxsein ML, Kim H, Li XJ, Smith-Adaline EA, Aiolova M, Wozney JM (2006) rhBMP-2/Calcium phosphate matrix accelerates osteotomy- site healing in a nonhuman primate model at multiple treatment times and concentrations. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 88:144–160 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Shafritz A, Shore EM, Gannon FH, Zasloff MA, Taub R, Muenke M, Kaplan FS (1996) Overexpression of an osteogenic morphogen in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. N Engl J Med 335:555–561 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Brown MA, Kaplan FS (2006) A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet 38:525–527 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Swiontkowski MF, Aro HT, Donell S, Esterhai JL, Goulet J, Jones A, Kregor PJ, Nordsletten L, Paiement G, Patel A (2006) Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in open tibial fractures. A subgroup analysis of data combined from two prospective randomized studies. J Bone Joint Surg -Am 88:1258–1265 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Urist MR (1965) Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science 150:893–899 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Urist MR (1980) Bone transplants and implants. Lippencott, Philadelphia Pennsylvania

- 22.Warnke PH, Springer IN, Wiltfang J, Acil Y, Eufinger H, Mehmoller M, Russo PAJ, Bolte H, Sherry E, Behrens E, Terheyden H (2004) Growth and transplantation of a custom vascularised bone graft in a man. Lancet 364:766–770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW, Hewick RM, Wang EA (1988) Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science 242:1528–1534 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ziran BH, Smith WR, Lahti Z, Williams A (2004) Use of calcium-based demineralized bone matrix (DBM) allograft product for nonunions and posttraumatic reconstruction of the appendicular skeleton: preliminary results and complications. Orthopaedic Trauma Association Annual Meeting, Oct 8–10th, 2004, Paper #64