Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) frequently have co-occurring depressive disorders and are often seen in multiple-care settings. Existing research does not assess the impact of care setting on delivery of evidence-based depression care for these patients.

Objective

To examine the prevalence of guideline-concordant depression treatment among these co-morbid patients, and to examine whether the likelihood of receiving guideline-concordant treatment differed by care setting.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Patients

A total of 5,517 veterans with COPD that experienced a new treatment episode for major depressive disorder.

Measurements and Main Results

Concordance with VA treatment guidelines for depression; multivariate analyses of the relationship between guideline-concordant depression treatment and care setting. More than two-thirds of the sample was over age 65 and 97% were male. Only 50.6% of patients had guideline-concordant antidepressant coverage (defined by the VA). Fewer than 17% of patients received guideline recommended follow-up (≥3 outpatient visits during the acute phase), and only 9.9% of the cohort received both guideline-concordant antidepressant coverage and follow-up visits. Being seen in a mental health clinic during the acute phase was associated with a 7-fold increase in the odds of receiving guideline-concordant care compared to primary care only. Patients seen in pulmonary care settings were also more likely to receive guideline-concordant care compared to primary care only.

Conclusions

Most VA patients with COPD and an acute depressive episode receive suboptimal depression management. Improvements in depression treatment may be particularly important for those patients seen exclusively in primary care settings.

KEY WORDS: depression, evidence-based treatment, medical comorbidity, COPD

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and depression are among the leading causes of disability worldwide.1 These 2 conditions also commonly co-occur. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among COPD patients has been estimated at 40–50%.2–4 There are important consequences associated with these symptoms. In COPD patients, depression has been found to be a strong predictor of COPD treatment failure,5 diminished functional status,6 worse general and COPD-specific health-related quality of life,7 and mortality,8 which suggests the need to better understand the interactions between these 2 conditions and the potential mediating effect of depression treatment.

Fortunately, effective depression care exists. Clinical practice guidelines for antidepressant treatment have been developed by the American Psychiatric Association,9 National Committee for Quality Assurance,10 and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).11 Evidence suggests that guideline adherence improves functioning and well-being outcomes12,13 and is associated with a lower probability of relapse or recurrence.14 However, there is variation in the extent to which persons with depression receive guideline-concordant medication and follow-up visits. The proportion of persons diagnosed with a new depression treatment episode that received guideline-concordant antidepressant medication during the acute phase ranges from 46.4% (Medicaid patients) to 60.9% (commercially insured patients).15,16 Among VA patients, national estimates of acute phase, medication guideline adherence range from 66% to 84.7%.17,18 Limited evidence suggests that even fewer persons with depression receive guideline-concordant follow-up care. The only national study of depression follow-up visits among veterans reports that 16% of those with depression receive guideline concordant follow-up care.18 These studies have not assessed guideline-concordant depression treatment in patients with medical comorbidities such as COPD or the factors that are associated with guideline concordance among these patients. This is important because there is evidence that the odds of receiving adequate depression care may vary by medical comorbidity.19 In particular, 1 study showed that patients with depression and COPD were less likely to receive adequate antidepressant coverage than patients with depression and other medical comorbidities such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, or osteoarthritis.20

Furthermore, the existing literature does not adequately explain the best processes for treating patients with depression and medical comorbidities such as COPD. Although the most effective depression treatment involves referral to mental health specialty care21–24 or primary-care-based depression care management that involves mental health specialty care,25,26 it is unclear how these approaches impact patients who also have COPD because these patients are seen in a variety of care settings. Although some COPD-depression patients are referred to mental health specialty care, some are only seen in primary care, where there is a risk that depression follow-up care will fail to occur because of the competing demands problem.27 Other COPD-depression patients are seen in pulmonary settings, where we would not expect clinicians to provide follow-up depression care. Still other COPD-depression patients are seen in multiple settings during their depression episode, raising questions about care coordination across settings.

The objectives of this study are to determine: (1) the extent to which patients with COPD and comorbid depression receive guideline-concordant depression care, and (2) whether care setting is related to the likelihood of receiving guideline-concordant depression care, when controlling for other patient factors such as demographics and comorbid conditions that may influence the receipt of such care.

METHODS

Using a retrospective cohort design, VA administrative data were used to identify patients with a diagnosis of COPD (ICD-9 491.×, 492.×, 496) any time between October 1, 1997 and September 30, 1998. Patients who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD 295.×× excluding 295.4×) or bipolar disorder (ICD 296.×× excluding 296.2× and 296.3×) any time between October 1, 1997 and September 30, 2002 were excluded from the cohort as these conditions often change depression treatment recommendations. Because we only wanted to include patients that used VA pharmacy services, patients that did not receive at least one 30-day supply of a medication from a VA pharmacy were excluded. The institutional review board at the Hines VA Hospital approved the study, and the need for written informed consent was waived.

New Depression Treatment Episode

Our definition of new depression treatment episodes was based on the VA performance measures for major depressive disorder. Patients were considered to have a new depression treatment episode if they had an eligible depression diagnosis between February 1, 1999 and September 30, 2002. An eligible depression diagnosis was defined as having: (a) a primary diagnosis of major depression (ICD 296.2×, 296.3×, 298.0×, 300.4×, 309.1×, 311.××) in any inpatient or outpatient setting, (b) a secondary diagnosis of major depression during an inpatient stay, or (c) at least 2 secondary diagnoses of major depression on different days within a 12-month period in any outpatient setting. We identified the index date as the date of the first eligible diagnosis of depression during the observation period. Patients with a depression diagnosis within 120 days before the index date were excluded from the cohort.

Because we were interested in rates of guideline-concordant care, patients also had to have an index prescription for an antidepressant to be included in the cohort. An index prescription was defined as the first antidepressant prescription that was filled either within 30 days before the index date or 14 days after the index date. If patients had another antidepressant prescription filled less than 90 days before their index prescription, they were excluded from the analysis because they were not considered new treatment episodes.

Guideline-Concordant Depression Care

Guideline-concordant care for patients with new treatment episodes of major depression was defined according to the VA performance criteria and consists of 2 separate criteria, a medication criterion and a follow-up visits criterion. To meet the medication criteria, patients had to have an adequate supply of antidepressants to cover at least 84 days of the 114 days after their index prescription date. To meet the follow-up visit criteria, patients had to have 3 clinical encounters for depression management in the 84 days after their index date. We determined whether patients met the medication criteria and follow-up criteria separately and whether patients met both criteria.

To determine whether patients received the 84 days of antidepressant treatment during the acute phase, we identified all prescriptions filled from the index prescription date to 114 days after the index prescription date. We summed the total days supply of these prescriptions to determine the total number of days of antidepressant treatment for each patient during this period. For patients receiving more than 1 antidepressant, we avoided double-counting days of antidepressant treatment by only counting 1 prescription if multiple prescriptions were filled on the same day and by not counting overlaps in days’ supply of more than 1 medication.

To meet the criteria for follow-up visits, patients had to have at least 3 qualifying follow-up visits during the 84-day period after their diagnosis, where only 1 of the qualifying visits could be a telephone contact. The qualifying mental health visits were any psychiatric visit or any non-psychiatric visit with a mental health diagnosis code (ICD 290.×, 293.×, 294.×, 295.×, 296.×, 297.×, 298.×, 299.×, 300.×, 301.×, 302.×, 306.×, 307.×, 308.×, 309.×, 310.×, 311.×, 312.×, 313.×, 314.×, 315.×, 316.×) associated with that encounter. Telephone encounters were identified with procedure codes (CPT 99371, 99372, 99373).

Care Setting as a Predictor of Guideline-Concordant Care

Care setting was defined as the sector or location of care (primary care, mental health specialty, pulmonary, other specialty) where patients received outpatient treatment. Looking at all outpatient visits, we identified whether patients were not seen in a mental health setting before their treatment episode but received mental health specialty care during their treatment episode. We also identified the care sectors in which patients were seen 12 months before their depression treatment episode, using 6 mutually exclusive groups to describe combinations of where care was received: primary care only, mental health only, primary care and mental health, primary care and pulmonary care, primary care and mental health and pulmonary care, or other.

Covariates

We used encounter data in the 12-month period preceding the index date to define covariates for age, gender, race, and marital status. We identified individual comorbidities using ICD-9 codes. Behavioral health comorbidities were identified from inpatient and outpatient encounters in the 12-month period before the index date and included anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, and dementia. Medical comorbidities included coronary heart disease (CHD), lung cancer, colon cancer, stroke, hypertension, arthritis, and diabetes. To help characterize the severity of COPD, we determined the number of COPD-related hospitalizations and the total length of stay for COPD-related hospitalizations during the 12 months before the index date. We also determined the number of non-COPD related hospitalizations during this period.

Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of the patients included in the analysis were described using count and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Comparisons between the groups with and without guideline-concordant depression care were made with χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. The association between having guideline-concordant depression care and patient characteristics was first evaluated in unadjusted models. After ruling out potential multicollinearity, multivariate logistic regression was then used to estimate the odds of receiving guideline-concordant depression care by care setting while controlling for age, race, marital status, comorbidities and COPD-related hospitalizations. All analyses were performed with Stata statistical software, version 9.2 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

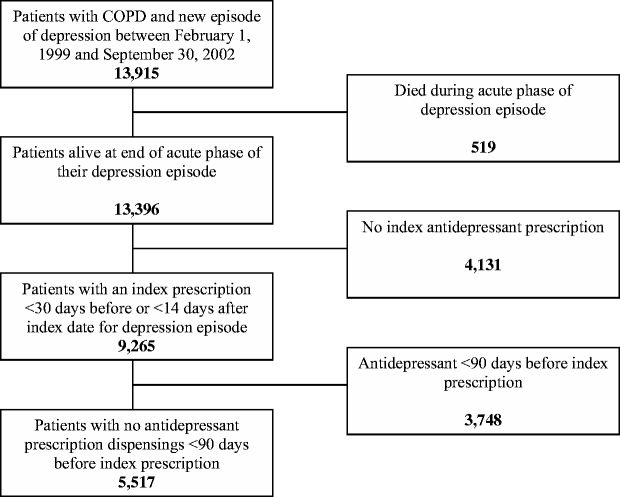

We identified a cohort of 179,216 patients with a diagnosis of COPD. Of those, 13,915 (7.8%) had a new treatment episode for depression during the observation period (Fig. 1). From this cohort, we excluded 519 (3.7%) that died during the acute phase, 4,131 (29.7%) with no index antidepressant prescription, and 3,748 (26.9%) with an antidepressant dispensed less than 90 days before their index prescription. There were 5,517 patients included in the final cohort for the analysis.

Fig. 1.

Patient cohort included in the analysis

During the acute phase of the treatment episode, 50.6% of the patients received guideline-concordant care with antidepressants (Table 1). The proportion of patients that had guideline-concordant follow-up visits was 16.3%. When medication and follow-up visit criteria were combined, only 9.9% of patients received guideline-concordant care for both components of the performance measure.

Table 1.

Depression Treatment During Acute Phase (N = 5,517)

| Guideline-concordant depression care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Medications | 2,794 | (50.6) | 2,723 | (49.4) |

| Follow-up visits | 899 | (16.3) | 4,618 | (83.7) |

| Both | 545 | (9.9) | 4,972 | (90.1) |

Patients that received guideline-concordant care were twice as likely to have not received mental health specialty care before their index depression episode but received such specialty care during their treatment episode (Table 2). Those receiving guideline-concordant care were also more likely to have received mental health specialty care before their depression treatment episode, whether solely or in combination with primary care or pulmonary care.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Guideline-concordant Depression Care

| Received guideline-concordant depression care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p value | |||

| N | 545 | 9.9% | 4,972 | 90.1% | |

| Age, n (%) | <.001 | ||||

| Under 55 | 84 | 15.4 | 480 | 9.7 | |

| 55–64 | 128 | 23.5 | 894 | 18.0 | |

| 65–74 | 137 | 25.1 | 1,612 | 32.4 | |

| 75 and over | 196 | 36.0 | 1,986 | 39.9 | |

| Male, n (%) | 531 | 97.4 | 4,851 | 97.6 | .85 |

| Race, n (%) | .54 | ||||

| White | 363 | 66.6 | 3,228 | 64.9 | |

| Black | 24 | 4.4 | 273 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 14 | 2.6 | 102 | 2.1 | |

| Unknown | 144 | 26.4 | 1,369 | 27.5 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | .43 | ||||

| Married | 325 | 59.6 | 3,052 | 61.4 | |

| Other | 220 | 40.4 | 1,920 | 38.6 | |

| COPD-related hospitalization in 12 months before index date, n (%) | 121 | 22.2 | 1,082 | 21.8 | .81 |

| Non-COPD hospitalization before index date, n (%) | 76 | 13.9 | 590 | 11.9 | .16 |

| Hospitalization (any cause) during acute phase | 66 | 12.1 | 465 | 9.4 | .04 |

| Behavioral health comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Anxiety disorder | 106 | 19.5 | 641 | 12.9 | <.001 |

| PTSD | 46 | 8.4 | 226 | 4.6 | <.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 133 | 24.4 | 1,125 | 22.6 | .35 |

| Drug abuse | 13 | 2.4 | 41 | 0.8 | <.001 |

| Dementia | 17 | 3.1 | 93 | 1.9 | .05 |

| Care settings before index date, n (%) | <.001 | ||||

| Primary care only | 288 | 52.8 | 3,188 | 64.1 | |

| Mental health (MH) only | 6 | 1.1 | 11 | 0.2 | |

| Primary care + mental health | 98 | 18.0 | 582 | 11.7 | |

| Primary care + pulmonary | 94 | 17.3 | 828 | 16.7 | |

| Primary care + mental health + pulmonary | 45 | 8.3 | 177 | 3.6 | |

| Other | 14 | 2.6 | 186 | 3.7 | |

| No MH care before index date and MH care during acute phase, n (%) | 286 | 52.5 | 1,297 | 26.1 | <.001 |

| Comorbid medical conditions before index date, n (%) | |||||

| CHD | 202 | 37.1 | 1,858 | 37.4 | .89 |

| Lung cancer | 24 | 4.4 | 173 | 3.5 | .27 |

| Colon cancer | 5 | 0.9 | 73 | 1.5 | .30 |

| Stroke | 37 | 6.8 | 391 | 7.9 | .37 |

| Hypertension | 317 | 58.2 | 2,812 | 56.6 | .47 |

| Arthritis | 205 | 37.6 | 1,821 | 36.6 | .65 |

| Diabetes | 135 | 24.8 | 1,058 | 21.3 | .06 |

Patients that received guideline-concordant care were slightly younger and more likely to have been hospitalized during the acute phase of their treatment episode. Patients receiving guideline-concordant care had higher rates of anxiety disorder and PTSD and a slightly higher rate of drug abuse.

The results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 3. Among the patients that were not seen by a mental health provider before their index depression episode, being seen in a mental health clinic during the acute phase was associated with more than a 7-fold (odds ratio [OR] = 7.59, 95% CI 5.87–9.81) increase in the odds of receiving guideline-concordant care. Patients seen in a mental health clinic before their index treatment episode were 17 times (95% CI 5.92–48.62) more likely to have received guideline-concordant care than patients seen only in primary care. With the exception of the “other” care setting, all of the settings that we examined were associated with increased odds of receiving guideline-concordant care compared to the primary care setting alone.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Guideline-concordant Depression Care

| Antidepressants only | Follow-up visits only | Both | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. OR | 95% CI | Adj. OR | 95% CI | Adj. OR | 95% CI | |

| No MH care before index date and MH care during acute phase | 1.11 | [0.98, 1.26] | 7.94 | [6.45, 9.77] | 7.59 | [5.87, 9.81] |

| Seen in PC and MH before index date | 1.03 | [0.85, 1.25] | 5.53 | [4.19, 7.31] | 5.40 | [3.82, 7.63] |

| Seen in MH only before index date | 2.03 | [0.74, 5.60] | 8.03 | [2.85, 22.63] | 16.97 | [5.92, 48.62] |

| Seen in PC and pulmonary before index date | 1.00 | [0.85, 1.16] | 2.87 | [2.26, 3.66] | 2.68 | [2.01, 3.58] |

| Seen in PC and MH and pulmonary before index date | 1.15 | [0.86, 1.53] | 8.04 | [5.64, 11.46] | 8.24 | [5.40, 12.56] |

| Seen in other care setting before index date | 0.81 | [0.61, 1.09] | 1.10 | [0.70, 1.72] | 0.80 | [0.45, 1.45] |

| 55–64 | 1.09 | [0.89, 1.35] | 0.77 | [0.59, 1.00] | 0.90 | [0.66, 1.22] |

| 65–74 | 1.04 | [0.85, 1.26] | 0.60 | [0.46, 0.78] | 0.60 | [0.44, 0.82] |

| 75 and above | 1.01 | [0.83, 1.23] | 0.70 | [0.55, 0.91] | 0.73 | [0.54, 1.00] |

| Non-white | 0.69 | [0.56, 0.85] | 1.04 | [0.79, 1.38] | 0.74 | [0.51, 1.07] |

| Race unknown | 0.97 | [0.86, 1.09] | 1.00 | [0.83, 1.19] | 0.96 | [0.77, 1.18] |

| Married | 1.13 | [1.01, 1.26] | 0.84 | [0.72, 0.98] | 0.99 | [0.81, 1.20] |

| Had COPD hospitalization before index date | 0.91 | [0.79, 1.04] | 0.96 | [0.79, 1.16] | 0.96 | [0.76, 1.22] |

| Had non-COPD hospitalization before index date | 0.81 | [0.68, 0.96] | 1.16 | [0.91, 1.46] | 1.09 | [0.82, 1.45] |

| Hospitalized during acute phase (any cause) | 1.20 | [1.00, 1.45] | 1.13 | [0.87, 1.45] | 1.27 | [0.95, 1.71] |

| Anxiety before index date | 1.12 | [0.96, 1.33] | 1.34 | [1.08, 1.65] | 1.32 | [1.02, 1.70] |

| PTSD before index date | 0.88 | [0.68, 1.15] | 1.65 | [1.21, 2.23] | 1.22 | [0.85, 1.77] |

| Alcohol use disorder before index date | 0.87 | [0.76, 0.99] | 1.11 | [0.92, 1.34] | 0.95 | [0.75, 1.19] |

| Drug use disorder before index date | 1.04 | [0.60, 1.80] | 2.68 | [1.48, 4.85] | 1.93 | [0.98, 3.78] |

| Dementia before index date | 1.52 | [1.03, 2.26] | 1.13 | [0.68, 1.87] | 1.54 | [0.89, 2.68] |

| CHD before index date | 1.08 | [0.96, 1.21] | 1.00 | [0.85, 1.19] | 0.94 | [0.77, 1.16] |

| Lung cancer before index date | 1.05 | [0.78, 1.40] | 1.61 | [1.10, 2.35] | 1.45 | [0.92, 2.31] |

| Colon cancer before index date | 0.77 | [0.49, 1.21] | 0.49 | [0.22, 1.11] | 0.64 | [0.25, 1.63] |

| Stroke before index date | 1.01 | [0.82, 1.23] | 0.84 | [0.62, 1.14] | 0.87 | [0.60, 1.26] |

| Hypertension before index date | 0.97 | [0.87, 1.09] | 1.07 | [0.91, 1.27] | 1.06 | [0.87, 1.30] |

| Arthritis before index date | 1.00 | [0.89, 1.12] | 1.02 | [0.87, 1.20] | 0.94 | [0.78, 1.15] |

| Diabetes before index date | 0.96 | [0.84, 1.10] | 1.15 | [0.95, 1.38] | 1.22 | [0.98, 1.52] |

Adj. ORs in bold text were statistically significant at p <0.05.

Older age was associated with lower odds of receiving guideline-concordant care, as patients in the 2 older age categories (65–74 years, OR = 0.60 [95% CI 0.46–0.78]; 75 and over, OR = 0.70 [95% CI 0.55–0.91]) had lower odds of receiving guideline-concordant follow-up visits. Non-whites had lower odds of receiving medication-related guideline-concordant care (OR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.56–0.85). Other factors that were associated with increased odds of receiving guideline-concordant care were a history of drug use disorder (follow-up visits only), an anxiety diagnosis (follow-up visits only and both), a PTSD diagnosis (follow-up visits only), a lung cancer diagnosis (follow-up visits only), and a dementia diagnosis (antidepressants only).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that there is an opportunity to increase the number of veterans with COPD and depression that receive guideline-concordant care for their depressive symptoms. Only 50.6% of the study sample received an adequate supply of antidepressant medication during the acute phase of their depression, and only 16.3% received an adequate number of follow-up visits during this same period. Nearly 9 of 10 veterans with COPD and depression failed to receive an overall course of guideline-concordant, acute-phase depression care.

These rates of guideline-concordant depression care are consistent with previous studies of the VA population. The 50.6% rate of guideline-concordant antidepressant coverage is lower than the lowest published national estimate (66%),18 but similar to a regional study of veterans with depression and COPD (52.8%).20 The 16.3% rate of guideline-concordant follow-up visits is similar to 1 study,18 but much lower than the other published estimate (62%), in which the authors allowed the initial diagnosis visit to count as 1 of the 3 required visits.21

Clinic setting was an important predictor of receiving guideline-concordant depression treatment. Even after controlling for other characteristics, patients seen in a mental health clinic during the acute phase were more than 7 times more likely to have received guideline-concordant care than those seen only in primary care. This association between exclusive treatment in primary care and inadequate depression care is consistent with other studies of VA21 and non-VA populations,24,28–30 although none of these previous studies explicitly addressed patients with additional comorbidities such as COPD.

Whereas the relationship between mental health specialty care and receipt of guideline-concordant depression care was not surprising, the effect of pulmonary care on the receipt of guideline-concordant depression care was unexpected. Patients seen in a pulmonary setting before their depression treatment episode were more than 2 times more likely to have received guideline-concordant care than those seen only in primary care. This may occur because primary care providers know that the patient’s COPD is being managed in the pulmonary clinic, allowing them to focus on the patient’s depression.

Regardless of care location, most patients with depression and COPD fail to receive guideline-concordant depression treatment. Previous studies of guideline-concordant depression care have focused on patients seen in primary care or mental health specialty care. This study extends those findings to show that low rates of guideline-concordant depression care exist in subspecialty settings such as pulmonary, and even the majority of patients being seen in mental health settings still do not receive guideline-concordant care. Despite additional opportunities for follow-up care for patients referred by their primary care “gatekeeper”, who are likely to have more severe depression than patients not referred, patients seen in clinic setting combinations that included mental health (primary care and mental health, primary care and mental health and pulmonary) only had a 2-in-10 chance of receiving guideline-concordant depression care, leaving an opportunity to improve depression care regardless of care setting.

Given that a little less than half of the study sample was only seen in primary care during the acute phase, these findings point to a large gap in depression management within the VA. Although previous efforts, such as early identification via the electronic medical record, and more recent quality improvement efforts within the VA have enabled ∼80% of patients to be treated effectively in primary care,25 collaborative depression care is not routinely used.31 These findings suggest the need for increased care coordination for patients with depression and COPD to insure that these patients receive adequate depression follow-up care.

There are several limitations associated with these findings. With administrative data we were unable to control for depression severity, and we may expect patients seen in mental health clinics may have more severe depression and thus receipt of guideline-concordant care may be related to depression severity. However, preliminary findings from the STAR*D clinical trial suggest that specialty care and primary care patients have equivalent levels of depression severity.32 Furthermore, if comorbid mental health conditions are a proxy for depression severity, then the presence of these comorbidities may confound the relationship between site of care and receipt of guideline-concordant care. We may have underestimated the number of follow-up visits for veterans who seek care outside the VA system, although recent research shows that supplementing VA data with Medicare data does not significantly increase the number of depression follow-up visits identified.33 Poor treatment adherence is also affected by patient knowledge and attitudes as well as provider- and system-level factors,34 but our dataset lacked these measures.

The study findings point to other areas for future research. The VA’s depression guidelines have not as yet been conclusively linked to improved depression outcomes,35 so future studies should assess whether receipt of guideline-concordant care by veterans with COPD and depression is associated with better depression outcomes. Similarly, future research should consider the impact of guideline-concordant depression care on COPD outcomes. Furthermore, this study suggests that for patients with depression and COPD, single-setting treatment in the primary or pulmonary setting, as well as shared care without mental health services, currently is associated with poor depression guideline adherence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Bartle for his assistance in preparing the data for analysis.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Footnotes

This study was funded by the VA Health Services Research & Development Service.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy—lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Sci Mag. 1996;1:740–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Clary GL, Palmer SM, Doraiswamy PM. Mood disorders and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current research and future needs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(3):213–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mikkelsen RL, Middelboe T, Pisinger C, Stage KB. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2004;58(1):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Norwood R, Balkissoon R. Current perspectives on management of co-morbid depression in COPD. COPD. 2005;2(1):185–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dahlen I, Janson C. Anxiety and depression are related to the outcome of emergency treatment in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 2002;122(5):1633–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Weaver TE, Richmond TS, Narsavage GL. An explanatory model of functional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nurs Res. 1997;46(1):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Felker B, Katon W, Hedrick SC, Rasmussen J, McKnight K, McDonnell MB, et al. The association between depressive symptoms and health status in patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(2):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echaguen A, et al. Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1441–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for major depressive disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(4 Suppl):1–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Antidepressant medication management. The State of Health Care Quality, 2002 [cited October 5, 2005]. Available from: DOI www.ncqa.org/sohc2002/SOHC_2002_AMM.html.

- 11.Veterans Health Administration Office of Quality and Performance. Clinical practice guideline for major depressive disorder [cited October 5, 2005]. Available from: DOI www.oqp.med.va.gov/cpg/MDD/MDD_base.htm.

- 12.Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):696–703. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1128–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality, 2005. Washington, DC; 2005.

- 16.Akincigil A, Bowblis JR, Levin C, Walkup JT, Jan S, Crystal S. Adherence to antidepressant treatment among privately insured patients diagnosed with depression. Med Care. 2007;45(4):363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Busch SH, Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA. Comparing the quality of antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the Department of Veterans Affairs and the private sector. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(12):1386–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.McCarthy JF, Bambauer KZ, Austin K, Jordan N, Valenstein M. Datapoints: treatment for new episodes of depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007; 58:1035. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC, Kallas H. The influence of comorbid chronic medical conditions on the adequacy of depression care for older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2178–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Pirraglia PA, Charbonneau A, Kader B, Berlowitz DR. Adequate initial antidepressant treatment among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of depressed veterans. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(2):71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, et al. Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Med Care. 2003;41(5):669–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kniesner TJ, Powers RH, Croghan TW. Provider type and depression treatment adequacy. Health Policy. 2005;72(3):321–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS. Caring for depression. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- 24.Weilburg JB, O’Leary KM, Meigs JB, Hennen J, Stafford RS. Evaluation of the adequacy of outpatient antidepressant treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(9):1233–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Felker BL, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Developing effective collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(1):12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Coyne JC, Cooper-Patrick L, Rubenstein L. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(2):150–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):569–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Pincus HA, Pechura CM, Elinson L, Pettit AR. Depression in primary care: linking clinical and systems strategies. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(6):311–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Solberg LI, Korsen N, Oxman TE, Fischer LR, Bartels S. The need for a system in the care of depression. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):973–9. [PubMed]

- 31.Rubenstein LV. Improving care for depression: there’s no free lunch. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):544–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi M, et al. A direct comparison of presenting characteristics of depressed outpatients from primary vs. specialty care settings: preliminary findings from the STAR*D clinical trial. Gen Hosp Psych. 2005;27(2):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.McCarthy JF, Bambauer KZ, Austin K, Kales HC, Valenstein M. VA Treatment for New Episodes of Depression: Does Dual-System Use Explain Poor Performance? VA HSR&D National Meeting; 2007; Arlington, VA; 2007.

- 34.Miller NH, Hill M, Kottke T, Ockene IS. The multilevel compliance challenge: Recommendations for a call to action—A statement for healthcare professionals. Circulation. 1997;95(4):1085–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Katon WJ, Unutzer A, Simon G. Treatment of depression in primary care—Where we are, where we can go. Medical Care. 2004;42(12):1153–7. [DOI] [PubMed]