Abstract

Objectives. We sought to determine whether US physicians’ practice patterns in treating tobacco use at ambulatory visits improved over the past decade with the appearance of national clinical practice guidelines, new smoking cessation medications, and public reporting of physician performance in counseling smokers.

Methods. We compared data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, an annual survey of a random sample of office visits to US physicians, between 1994–1996 and 2001–2003.

Results. Physicians identified patients’ smoking status at 68% of visits in 2001–2003 versus 65% in 1994–1996 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.04, 1.30). Physicians counseled about smoking at 20% of smokers’ visits in 2001–2003 versus 22% in 1994–1996 (AOR=0.84; 95% CI=0.71, 0.99). In both time periods, smoking cessation medication use was low (<2% of smokers’ visits) and visits with counseling for smoking were longer than those without such counseling (P<.005).

Conclusions. In the past decade, there has been a small increase in physicians’ rates of patients’ smoking status identification and a small decrease in rates of counseling smokers. This lack of progress may reflect barriers in the US health care environment, including limited physician time to provide counseling.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of mortality in the United States.1,2 Despite strong evidence that brief physician interventions at office visits increase patients’ smoking cessation rates, US physicians have had low rates of identifying patients’ smoking status and counseling about smoking.3–6 Analysis of data from the 1991–1995 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NAMCSs) revealed that US physicians identified patients’ smoking status at 66% of outpatient visits and counseled about smoking at 22% of visits by smokers.3

Since these data were collected, substantial efforts have been made to increase physicians’ activities regarding the treatment of tobacco dependence. The US Public Health Service released and promoted evidence-based national guidelines for the treatment of tobacco use in 1996 and updated them in 2000.4,7 These guidelines recommend that at every office visit physicians identify a patient’s smoking status, advise every smoker to quit, and offer brief counseling and pharmacotherapy to all smokers who are ready to quit. In 1997, tobacco treatment became a quality-of-care measure for assessing the performance of physicians and health plans.8 Since 1996, new smoking cessation medications (bupropion and new nicotine replacement products) have become available for physician prescription, and the nicotine gum and patch have switched to nonprescription status.9

These factors expanded treatment options and increased national attention on physicians’ treatment of smokers. We hypothesized that US physicians’ rates of identifying smoking status, counseling about smoking, and prescribing cessation medications would have increased over the past decade. We used the NAMCS to compare US physicians’ practice patterns between 1994–1996 and 2001–2003.

METHODS

Sample

The NAMCS is an ongoing annual survey of US office-based physicians conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.10 Doctors of medicine and osteopathy are selected by stratified random sampling from American Medical Association and American Osteopathic Association listings of all US practicing physicians. The unit of analysis is the patient visit. The National Center for Health Statistics utilizes a complex 3-stage sampling design that has been described elsewhere.11,12 The probability sampling is the same for all years and is based on geographically related primary sampling units, physician practices within those units, and patient visits within practices. The same physician cannot be sampled more frequently than every 3 years.

Each participating physician completes a 1-page encounter form for each systematically sampled ambulatory care visit during a randomly assigned week. Outpatient care in hospital settings, by telephone, or by nonphysician providers is excluded. Physicians record information about patient demographics, patient’s smoking status, expected source of payment, reasons for patient’s visit, the physician’s diagnoses, counseling and education provided, patient’s current medications, and the duration of the visit in minutes.

Measures

We compared pooled data from the 1994–1996 NAMCSs with data from the 2001–2003 surveys. We included all visits by patients aged 18 years or older and examined 3 outcomes: (1) identification of the patient’s smoking status, (2) provision of smoking counseling, and (3) report of smokers’ use of nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion. We were unable to examine these outcomes for the years 1997–2000 because the smoking status item was not included on the NAMCS in those years.

Physicians identified a patient’s smoking status by answering the question, “Does patient use tobacco?” Smoking status was considered identified if the answer was “yes” or “no”; responses of “unknown” or left blank were considered not identified. Physicians recorded smoking counseling by checking the “Tobacco use/exposure” box under “Counseling/Education.” Prescription and nonprescription medications were recorded on the survey form under “Medications.” All adult patient visits were included in the analysis of smoking status. Analyses of smoking counseling and smoking medications were restricted to visits by patients identified as smokers. Because bupropion is also used to treat depression, we excluded bupropion prescriptions prior to 1997, the year it was approved for smoking cessation.

We chose 4 categories of medical conditions as predictor variables because they are associated with adverse outcomes from continued smoking: cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, and pregnancy. A condition was considered present if it was listed as either a patient’s reason for visit or as a physician’s diagnosis. Each condition variable was constructed with a combination of reason for visit codes, created by National Center for Health Statistics for NAMCS, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, diagnosis codes.13 All diagnosis categories were created as binary variables (e.g., cardiovascular disease vs no cardiovascular disease). Therefore, each visit could be included in more than 1 diagnosis category. Physicians were categorized as primary care (general internists, family practitioners, and generalists) or specialists (all other specialties). Type of visit was categorized as acute, chronic, or preventive care. Patients were classified as either established patients seen within the past 12 months, established patients not seen in the past 12 months, or new patients.

A priori we also defined a “best case” scenario in which a physician would clearly be expected to counsel about smoking: a visit to a primary care physician for a general medical examination by a patient who had not been seen in the past 12 months. We calculated how often physicians reported counseling at these types of visits.

Data Analysis

We assessed change over time by comparing the rates of identification of smoking status and smoking counseling for visits in 1994–1996 and in 2001–2003. We compared rates using weighted multiple logistic regression and controlled for patient demographics, physician specialty, and patient diagnoses.

Using data from 2001–2003, we determined factors independently associated with smoking status identification and smoking counseling using logistic regression. Covariates included in the model for determining predictors were patient demographics (age, gender, race), expected payment source for the visit, diagnoses and reasons for visit, new versus established patient status, physician specialty, and counseling for other behavioral risk factors (cholesterol, weight reduction, diet and nutrition, and exercise) provided during the visit. In a separate analysis, we assessed the impact of smoking counseling on the length of a visit using a t test and multiple linear regression to compare the mean duration of smokers’ visits with and without smoking counseling.

To preserve confidentiality, the public use data files contained only the first stage design information; however, these data files have been shown to produce reasonably accurate variance estimates.14 To produce unbiased national estimates, each patient visit was assigned an inflation factor called the “patient visit weight,” which was based on the probability of selection, the differences in response rates, and the specialty distributions. All of our statistical estimates were weighted to reflect national estimates. We determined a relative standard error for an estimate by dividing the standard error by the estimate itself to gauge the reliability of estimates for an individual year. An estimate with a relative standard error greater than 30% could be unreliable.12

All analyses were conducted with Stata version 8.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex). This software offers estimation and regression commands that handle stratified sampling and allow specification of sample weights. NAMCS data included variables that can be used to account for the clustering intrinsic to this design; we used these variables throughout our analyses.14

RESULTS

Data were available on 58991 adult patient visits to 2902 physicians in 2001–2003 and on 84104 visits to 4118 physicians in 1994–1996. Physician response rates were 67% for 2001–2003 and 71% for 1994–1996 (P=.001). Compared with 1994–1996 patients, patients from the 2001–2003 surveys were older (mean age 53.4 years vs 51.7 years; P<.001) and more likely to have cardiovascular disease and diabetes, but they did not differ in gender, race, or other diagnoses.

Figure 1 ▶ displays the rates at which physicians identified patients’ smoking status at office visits for each year during the study period. Overall, smoking status was identified at 68% of all visits in 2001–2003 compared with 65% in 1994–1996 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.04, 1.30). Patients were identified as smokers at 11% of all visits and at 17% of visits in which smoking status was known in 2001–2003, compared with 11% and 18%, respectively, in 1994–1996.

FIGURE 1—

US physicians’ rates of identifying patients’ smoking status at office visits: National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys, 1994–1996 and 2001–2003.

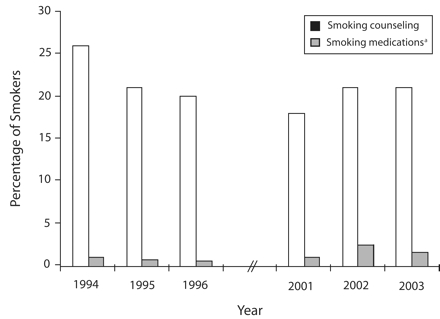

Figure 2 ▶ displays the rates at which physicians counseled about smoking and recorded smoking cessation medications at smokers’ visits. Overall, physicians counseled about smoking at 20% of all smokers’ visits in 2001–2003 compared with 22% of all smokers’ visits in 1994–1996 (AOR = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.71, 0.99). Smoking cessation medication use (nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion) was recorded infrequently. The relative standard errors for the estimates of medication use exceeded 30% and may be unreliable (see “Methods” section). Overall, smoking cessation medication use (bupropion or nicotine replacement therapy) was recorded at 1.70% of all smokers’ visits in 2001–2003. Nicotine replacement therapy use was reported at 0.30% of smokers’ visits in 2001–2003 and at 0.77% of smokers’ visits in 1994–1996. Bupropion use was recorded at 1.52% of nondepressed smokers’ visits and 1.87% of all smokers’ visits in 2001–2003.

FIGURE 2—

US physicians’ rates of providing smoking counseling and of reporting smoking cessation medications at office visits by smokers: National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys, 1994–1996 and 2001–2003.

aIncludes nicotine replacement therapy for all years and bupropion for the years 2001–2003.

To assess recent trends, we examined data from individual years from 2001 to 2003. The proportion of visits during which a patient’s smoking status was identified increased significantly from 64% of visits in 2001 to 71% of visits in 2003 (OR=1.15; 95% CI=1.02, 1.19; P=.02) and remained significant after adjustment for physician specialty and diagnoses (Figure 1 ▶). The rate of counseling smokers increased between 2001 (18% of smokers’ visits) and 2003 (21% of smokers’ visits) but was not statistically significant (OR=1.06; 95% CI=0.90, 1.24; P=.47; Figure 2 ▶).

Table 1 ▶ demonstrates trends over time in identification of smoking status and smoking counseling by physician specialty and diagnosis. The rate of smoking status identification increased significantly for specialists but not for primary care physicians. Both types of physicians had nonsignificant decreases in counseling over time.

TABLE 1—

Trends in the Identification of Smoking Status and Smoking Counseling, by Physician Specialty and Patient Diagnoses: National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys, 1994–1996 and 2001–2003

| Identification of Smoking Status at All Visitsa | Smoking Counseling at Smokers’ Visitsa | |||||

| 1994–1996, % | 2001–2003, % | AOR (95% CI)b | 1994–1996, % | 2001–2003, % | AOR (95% CI)b | |

| All visits | 65 | 68 | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 22 | 20 | 0.84 (0.71, 0.99) |

| Physician type | ||||||

| Primary care | 68 | 70 | 1.10 (0.91, 1.32) | 30 | 26 | 0.81 (0.65, 1.00) |

| Specialist | 62 | 67 | 1.21 (1.06, 1.39) | 15 | 14 | 0.87 (0.68, 1.12) |

| Diagnosis or reason for visitc | ||||||

| General medical examination | 65 | 69 | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) | 33 | 32 | 0.89 (0.62, 1.29) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 74 | 74 | 1.02 (0.84, 1.23) | 37 | 33 | 0.83 (0.62, 1.11) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 75 | 76 | 1.05 (0.80, 1.38) | 48 | 44 | 0.87 (0.62, 1.24) |

| Pregnancy | 79 | 82 | 1.24 (0.84, 1.83) | 29 | 29 | 1.15 (0.51, 2.57) |

| Diabetes | 72 | 73 | 1.09 (0.87, 1.36) | 32 | 29 | 0.87 (0.52, 1.50) |

Notes. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aPercent estimates were weighted to reflect national estimates.

bOdds ratios were adjusted for patient demographics, physician specialty, and diagnosis.

cReference for each diagnosis category includes all visits for diagnoses other than those specified in table.

Table 2 ▶ displays factors independently associated with physicians’ identification of a patient’s smoking status and provision of smoking counseling at visits in 2001–2003. These patterns are similar to those previously observed in 1994–1995.3 Primary care physicians were as likely as specialists were to identify a patient’s smoking status but were almost twice as likely to counsel smokers. All physicians were more likely to identify a patient’s smoking status and counsel about smoking during visits by patients with cardiovascular disease or chronic pulmonary disease than during visits by patients without these diagnoses.

TABLE 2—

Variables Associated With the Identification of Smoking Status and Smoking Counseling at Ambulatory Visits: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2001–2003

| Visits With Smoking Status Identified | Smokers’ Visits With Smoking Counseling | |||

| Variables | % | AOR (95% CI)b | % | AOR (95% CI)b |

| Total | 68 | . . . | 20 | . . . |

| Physician type | ||||

| Specialist | 67 | Ref | 14 | Ref |

| Primary care | 70 | 1.13 (0.94, 1.35) | 26 | 1.94 (1.48, 2.54) |

| Diagnosis or reason for visitc | ||||

| General medical examination | 69 | 1.02 (0.81, 1.27) | 32 | 1.05 (0.71, 1.57) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 74 | 1.38 (1.20, 1.58) | 33 | 2.03 (1.54, 2.67) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 76 | 1.56 (1.28, 1.90) | 44 | 3.79 (2.63, 5.45) |

| Pregnancy | 82 | 2.20 (1.65, 2.94) | 29 | 0.95 (0.54, 1.69) |

| Diabetes | 73 | 1.10 (0.94, 1.30) | 29 | 1.05 (0.69, 1.59) |

| Type of visit | ||||

| Acute problem | 70 | Ref | 20 | Ref |

| Chronic problem | 67 | 0.86 (0.78, 0.96) | 19 | 0.92 (0.69, 1.59) |

| Preventive care | 71 | 0.86 (0.70, 1.05) | 32 | 1.89 (1.33, 2.68) |

| Type of patient | ||||

| Established patient not seen in the past 12 months | 70 | Ref | 30 | Ref |

| Established patient seen in the past 12 months | 69 | 0.84 (0.69, 1.03) | 19 | 0.46 (0.33, 0.65) |

| New patient | 70 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.21) | 20 | 0.71 (0.47, 1.07) |

| Counseling about other behavioral risk factorsd | ||||

| No | 66 | Ref | 16 | Ref |

| Yes | 78 | 1.75 (1.53, 2.01) | 40 | 3.40 (2.64, 4.38) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–34 | 70 | Ref | 19 | Ref |

| 35–64 | 68 | 0.96 (0.88, 1.06) | 21 | 1.06 (0.80, 1.41) |

| ≥65 | 68 | 0.88 (0.75, 1.02) | 19 | 0.87 (0.55, 1.38) |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 65 | Ref | 19 | Ref |

| Women | 70 | 1.26 (1.16, 1.35) | 21 | 1.14 (0.94, 1.39) |

| Race | ||||

| Non-White | 68 | Ref | 21 | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68 | 1.10 (0.94, 1.30) | 18 | 1.17 (0.89, 1.55) |

| Expected source of payment | ||||

| Private insurance | 70 | Ref | 20 | Ref |

| Medicare | 69 | 1.11 (0.95, 1.29) | 19 | 0.95 (0.63, 1.43) |

| Medicaid | 73 | 1.10 (0.89, 1.37) | 29 | 1.79 (1.35, 2.37) |

| Other | 66 | 0.87 (0.72, 1.05) | 15 | 0.77 (0.54, 1.12) |

Notes. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aPercentage estimates were weighted to reflect national estimates.

bOdds ratios were adjusted for all variables listed in the table.

cReference for each diagnosis category includes all visits for diagnoses other than those specified in table.

dIncluded counseling for cholesterol, weight reduction, diet and nutrition, and exercise.

In a “best-case” scenario (visits by smokers who had not been seen in the past 12 months to primary care physicians for general medical exams), physicians counseled about smoking 54% of the time. Because time constraints are frequently cited by physicians as a barrier to counseling, we compared the duration of smokers’ visits with smoking counseling to those without counseling. In 2001–2003, smokers’ visits with counseling were longer than smokers’ visits without such counseling (20.9 vs 18.8 minutes; P<.001). This difference remained significant in a multivariate analysis after we controlled for physician specialty, patient diagnoses, and counseling about other behavioral risk factors. The duration of visits with smoking counseling in 1994–1996 was also longer than visits without such counseling (20.9 vs 19.6 minutes; P=.005) and was not significantly different from 2001–2003.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of a large national survey of US physicians revealed little progress in the rates at which physicians addressed patients’ tobacco use at office visits over the past decade. Physicians’ rates of identifying smoking status gradually increased, but their rates of counseling smokers decreased slightly. The pattern was consistent among primary care and specialist physicians and among patients with various diagnoses. Even when seeing a smoker for a smoking-related diagnosis or for preventive care in 2001–2003, physicians counseled about tobacco less than half of the time. The rate at which physicians prescribed medication for smoking cessation remains low. This minimal progress followed several external influences that were expected to have a greater impact on physicians’ practices.

There was a small increase over the past decade in the rate at which physicians identified patient smoking status, and the improvement from 2001 to 2003 suggests this trend is continuing. This could represent either an increase in how often physicians ask about smoking status or better physician documentation of smoking status. In either case, the efforts to make smoking status a “vital sign” are associated with a small improvement in identification of smoking status but no improvement in smoking counseling.4,15

Since 1994–1996, a small decrease in physicians’ counseling of smokers has occurred despite substantial national efforts to encourage physicians to do more. Even in a “best-case” scenario, smoking counseling occurred only about half of the time. Other national surveys have reported higher rates of counseling, but the discrepancy is likely attributable to differences in survey methodology.16–19 Data from the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set show a small improvement in the proportion of health plan members who smoke and report being advised to quit by a physician in the past year, from 62% in 1996 to 69% in 2003.16 Unlike NAMCS, which is visit based and derived from physician reports, the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set and other national surveys use patient recall and require only that a patient be advised to quit once in the past year. There is some evidence that patient recall is biased toward overreporting of advice to quit,20 and patients might misinterpret being asked about smoking as advice to quit. If so, the increase in Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set smoking counseling rates might reflect an increase in identification of smoking status rather than actual counseling. Studies that used direct observation of primary care physicians to collect data have also demonstrated low rates of smoking counseling at ambulatory visits that are similar to our data.5,21

It is important to consider why physicians’ rates of counseling about smoking have not improved. Most physicians regard addressing smoking as important and report feeling prepared to counsel about smoking.22,23 Limited time is often cited as a major barrier to counseling during an office visit.24–27 Our data confirm that visits with smoking counseling last significantly longer than visits without it. Other studies have shown that visits that include preventive services are longer and that time constraints limit the ability of physicians to comply with preventive services recommendations.24,25,27,28 Other major barriers to the provision of smoking counseling include competing demands of other medical problems during a visit, lack of insurance coverage for smoking cessation pharmacotherapies, and physician pessimism about whether smokers can quit.6,29

The results of this study indicate that there continues to be ample room for improvement in the treatment of smoking in the US health care setting. National guidelines and experts in tobacco treatment call for embedding physicians in a broader system that integrates smoking cessation treatment more easily into practice and continues the process of quitting outside the office.4,29,30 Health maintenance organizations have documented reductions in smoking prevalence after the adoption of aggressive system-level strategies to identify and document patients’ smoking status and to refer smokers to cessation resources.29,31–34

The visit-based nature of NAMCS allowed us to assess smoking interventions at each visit, as is recommended by national guidelines, but did not allow us to assess the likelihood that the patient was counseled over a discrete period of time, such as a year. Some physicians may have interpreted “counseling” as advice to quit, whereas others may have provided a more comprehensive intervention. The lower response rate of physicians in 2001–2003 could have influenced the results if the likelihood of survey response was associated with a physician’s likelihood of addressing tobacco at an office visit.

Between 1994 and 2003, the adult smoking prevalence in the United States decreased from 25.5% to 21.6% coincident with advances in tobacco control policy and public health efforts.35–37 By contrast, despite substantial national efforts to alter physician practice patterns and the availability of new drugs for treating tobacco, physicians made little progress in addressing their patients’ tobacco use. The lack of improvement likely reflects barriers in the current practice environment, most notably the lack of time to provide adequate preventive counseling. Our data suggest that for health care systems to improve their performance in tobacco treatment, efforts must broaden to include systems-level interventions that identify all patients’ smoking status and support clinicians’ efforts by facilitating referral to resources outside the physician’s office.

Acknowledgments

A. N. Thorndike received a Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award, Massachusetts General Hospital. N. A. Rigotti received a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K24-HL04440).

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors A. N. Thorndike and N. A. Rigotti originated the study. A. N. Thorndike supervised all aspects of its implementation. S. Regan was responsible for acquisition of the data and completed the analyses. All authors contributed to conceptualizing ideas, interpreting findings, and reviewing drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51: 300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Stafford RS, Singer DE. National patterns in the treatment of smokers by physicians. JAMA. 1998;279:604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- 5.Ellerbeck EF, Ahluwalia JS, Jolicoeur DG, Gladden J, Mosier MC. Direct observation of smoking cessation activities in primary care practice. J Fam Pract. 2001; 50:688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaén CR, McIlvain H, Pol L, Phillips RL, Flocke S, Crabtree BF. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:859–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore MC, Wetter DW, Bailey WC, et al. Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1996.

- 8.HEDIS 3.0, Volume 2: Technical Specifications. Washington DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 1997.

- 9.Burton SL, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of FDA-approved pharmacologic treatments for tobacco dependence—United States, 1984–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Public Use Data Tape Documentation, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1994–2003.

- 11.Bryant E, Shimizu I. Sample design, sampling variance, and estimation procedures for the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Vital Health Stat 2. 1988:1–39. [PubMed]

- 12.Cherry DK, Burt CW, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2001 Summary. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics; No. 337. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. 2003. [PubMed]

- 13.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1977.

- 14.Hing E, Gousen S, Shimizu I, Burt C. Guide to using masked design variables to estimate standard errors in public use files of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Inquiry. 2003:40: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle R, Solberg LI. Is making smoking status a vital sign sufficient to increase cessation support actions in clinical practice? Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:22–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The State of Health Care Quality: 2004. Washington DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2004.

- 17.Denny CH, Serdula MK, Holtzman D, Nelson DE. Physician advice about smoking and drinking: are US adults being informed? Am J Prev Med. 2003;24: 71–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cokkinides VE, Ward E, Jemal A, Thun MJ. Under-use of smoking-cessation treatments: results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2000. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, et al. Tobacco-cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward J, Sanson-Fisher R. Accuracy of patient recall of opportunistic smoking cessation advice in general practice. Tob Control. 1996;5:110–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Making time for tobacco cessation counseling. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis CE, Clancy C, Leake B, Schwartz JS. The counseling practices of internists. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsler H, Levine S, Idelson RK, Schor EL, Coakley E. The physician’s role in health promotion revisited—a survey of primary care practitioners. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:996–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA. Opportunistic preventive services delivery. Are time limitations and patient satisfaction barriers? J Fam Pract. 1998;46: 419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stange KC, Woolf SH, Gjeltema K. One minute for prevention: the power of leveraging to fulfill the promise of health behavior counseling. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 22:320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stafford RS, Saglam D, Causino N, et al. Trends in adult visits to primary care physicians in the United States. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder SA. What to do with a patient who smokes. JAMA. 2005;294:482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiore MC, Croyle RT, Curry SJ, et al. Preventing 3 million premature deaths and helping 5 million smokers quit: a national action plan for tobacco cessation. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson RS, Taplin SH, McAfee TA, Mandelson MT, Smith AE. Primary and secondary prevention services in clinical practice. Twenty years’ experience in development, implementation, and evaluation. JAMA. 1995;273:1130–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bentz CJ. Implementing tobacco tracking codes in an individual practice association or a network model health maintenance organisation. Tob Control. 2000;9 (suppl 1):I42–I45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.University of California, San Francisco. Smoking Cessation Leadership Center home page. Available at: http://smokingcessationleadership.ucsf.edu. Accessed July 26, 2007.

- 34.Stevens VJ, Solberg LI, Quinn VP, et al. Relationship between tobacco control policies and the delivery of smoking cessation services in nonprofit HMOs. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:1121–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroeder SA. Tobacco control in the wake of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]