Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of reported sexual, physical, or emotional abuse on the symptoms suggestive of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) and to determine the effect of race/ethnicity on these patterns.

Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey used a multi-stage stratified cluster sample to randomly sample 5,506 adults aged 30–79 from the city of Boston. BACH recruited 2,301 men (700 Black, 766 Hispanic, and 835 White). Interviewers administered questions approximating the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index (CPSI), and symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS were measured by the definition of perineal and/or ejaculatory pain and CPSI pain score of 4+. Questions about previous abuse were obtained from a validated self-administered questionnaire during the home visit. Logistic regression was used to determine the effect of abuse on the likelihood of a man having symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS.

Results

The prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS was 6.5%. Men who reported having experienced sexual, physical, or emotional abuse had increased odds (1.7–3.3) for symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS. Previous abuse increased both the pain and urinary scores from the CPSI.

Conclusion

Symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS are not uncommon in a community-based population of men. For men presenting with symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS, clinicians may wish to consider screening for abuse.

Key words: chronic prostatitis, abuse, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is a poorly understood constellation of symptoms estimated to affect about 10%–14% of the population.1–3 Infection or inflammation of the prostate and/or spasm of the pelvic floor muscles may contribute to the disease process; however, little is known regarding its exact etiology or pathophysiology. Presenting symptoms range from pain and/or discomfort in the perineum or on ejaculation to obstructive and/or irritative lower urinary tract symptoms. Primarily a diagnosis of exclusion, it confuses and frustrates patients and physicians alike; moreover, the condition is burdensome in terms of both the health-related quality-of-life implications4,5 and the economic impact.6,7 Socioeconomic factors such as lower income, lower education, and unemployment are associated with more severe CP/CPPS symptoms.8 Flor and Turk describe a diathesis-stress model of chronic back pain, which proposes that the interaction of personal stressors and a predisposing organic condition may result in chronic pain.9 Although several studies have examined the association of stressors such as sexual, physical, and emotional abuse with female chronic pelvic pain,10–13 the association of a history of abuse with male chronic pelvic pain, namely CP/CPPS, remains unexplored.

The prevalence of sexual and physical abuse is not insignificant, ranging from 4%–31% in men and 19%–37% in women.14–16 In addition, sexual and physical abuse in women may impact mental and physical health as well as utilization of healthcare services.7,17 Studies have established a relationship between self-reported sexual abuse and chronic pelvic,10, musculoskeletal,18,19 and gastrointestinal pain in women.16 Mounting evidence suggests that abuse may leave female survivors psychologically distressed and more likely to (1) attempt suicide, (2) report a history of substance abuse,7,20 (3) visit the emergency room,17 and (4) have a psychiatric admission.7 Finally, a history of abuse may prevent successful long-term treatment of chronic pain syndromes.21

As little is known about the association of abuse and pelvic pain in men, the aim of our study was to examine the relationship between sexual, physical, or emotional abuse and symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS and to assess the effect of race/ethnicity on this relationship.

METHODS

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) study is a population-based, random sample epidemiologic survey of a broad range of urologic symptoms supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. The BACH survey is a response to a NIH consensus panel recommendation that research on urologic conditions in minorities be given the highest priority, and a detailed description of the study methods has been published.22 A primary goal of the research design was to recruit equal numbers of subjects in each of 24 design cells, defined by age (30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–79 years), gender, and race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, White). The BACH 2-stage, stratified cluster sample (N = 5,506) was recruited from April 2002 through June 2005. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New England Research Institutes.

Race/ethnicity was defined by self report. Subjects were first asked if they considered themselves to be Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino (Latina). Next, they were queried: What race do you consider yourself to be? According to the Office of Management and Budget requirements, subjects selected from the following choices: American Indian or Alaska native; Asian; Black or African American; Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; or White or Caucasian, or other. If the response to the first question was yes, the subject was classified as Hispanic regardless of their response to the second question. A subject was classified as Black if they were not Hispanic and responded Black to the second question. A subject was classified as White if they were not Hispanic, not Black, and responded White to the second question.

Screenings were completed for 36.0% of the selected households, 30.0% of the households refused screening, and 34.0% of the households could not be contacted after at least 16 different attempts to reach them by mail, telephone, or field visit. In total, we successfully recruited 2,301 men and 3,205 women, 1,770 Blacks, 1,877 Hispanics, and 1,859 Whites. Interviews were completed with 63.3% of the screener identified eligible individuals from the selected households. Of the 5,506 interviews, 1,461 were conducted in Spanish mostly with Hispanic subjects.

A well-trained (bi-lingual) phlebotomist/interviewer obtained data by conducting a 2-h, in-person interview, generally in the subject’s home. Wherever possible, the questions and scales employed on BACH were selected from published instruments with documented metric properties and approved by a multidisciplinary Scientific Advisory Committee. Because the various source urologic symptom questionnaires were developed separately and used different recall intervals or contained similar questions, pretesting revealed that slight modifications were often necessary to maintain clarity for respondents.

Definitions of Symptom Complex

Symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS included: pain or discomfort in the pubic or bladder area, perineum, testicles, at the tip of the penis not related to urination; ejaculatory pain, pain, or burning during urination, incomplete emptying, and urinary frequency. The NIH chronic prostatitis symptom index (NIH-CPSI)23 is a validated scale to measure these symptoms. Based on previous work, the criteria used to identify significant symptoms associated with CP/CPPS were pain in the perineum and/or with ejaculation and a CPSI pain score of at least 4 points.2,3

To identify CP/CPPS-like symptoms, the 4-item pain scale of the NIH-CPSI and the 2-item urinary scale of the NIH-CPSI were approximated from the BACH baseline questionnaire. The BACH questionnaire used a recall period of 1 month for all questions, in contrast to 1 week on the NIH-CPSI. The BACH questionnaire asked about frequency of pain symptoms (I do not have the symptom, rarely, a few times, fairly often, usually, almost always) in contrast to yes/no on the NIH-CPSI. Responses of rarely to almost always were counted as yes. The third NIH-CPSI pain question on frequency was approximated by the highest frequency of the 6 pain questions. The average level of pain question only asked about pain or discomfort associated with your bladder. Thus, an approximate NIH-CPSI pain score could be calculated by simple addition (range 0–21). The 2 urinary questions from the NIH-CPSI were asked verbatim on the BACH questionnaire. The urinary score is a sum of the frequency of incomplete emptying and urinary frequency from never (=0) to almost always (=5; range 0–10).

Definition of Abuse

Respondents were asked about abuse experienced as a child (age 13 or younger) or as an adolescent/adult (age 14 or older) using a validated scale.24 Sexual abuse was present if any of the following experiences occurred (the perpetuator was an adult, and the experiences were unwanted): exposed sex organs of their body (childhood only), threatened to have sex with you, touched the sex organs of your body, made you touch the sex organs of their body, forced you to have sex, or other unwanted sexual experience. Physical abuse was present if an adult hit, kicked, or beat you (occasionally or often) or if an adult seriously threatened your life (seldom, occasionally, or often). Emotional abuse was present if an adult emotionally abused, humiliated, or insulted you (occasionally or often).

Definition of Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) was defined by a combination of education and income25 and was categorized such that one quarter of the BACH population was lower, one half middle, and one quarter upper.

Statistical Analyses

Multiple imputation was used to impute plausible values for missing data.27,28 Twenty-five imputations using the Markov chain Monte Carlo option in the SAS multiple imputation procedure were done separately by gender and race/ethnicity. Variables included in the multiple imputation were those considered in this analysis as well as numerous covariates such as comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and other urologic symptoms. Because of design requirements, the BACH subjects had unequal probabilities of selection into the study. In order for analyses to be representative of the city of Boston, it was necessary to weigh observations inversely proportional to their probability of selection into the study.26,29 Weights were further post-stratified to the population of Boston according to the 2000 Census. Chi-square tests were used to determine whether the prevalence of abuse differed by race/ethnicity or if the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS differed by presence or absence of abuse. Logistic regression was used to determine if the presence of abuse was a significant predictor of symptoms suggestive of prostatitis. Regression was used to determine the effect of abuse on the NIH-CPSI pain, urinary, and pain + urinary scores. Analyses were conducted in version 9.1 of SAS and version 9.0.1 of SUDAAN.

RESULTS

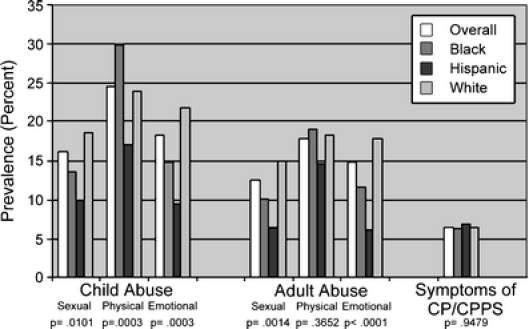

The prevalence of abuse in this BACH population ranged from 10%–30% and varied by race/ethnicity, Figure 1. The prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS was 6.5% and did not vary significantly by race/ethnicity (Fig. 1), age (Table 1), or SES (Table 1). There was no interaction of SES and the effect of abuse overall or by race/ethnicity (p > .05 for all interactions).

Figure 1.

Prevalence (in percent) of different types of abuse and symptoms suggestive of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) overall and by race/ethnicity. The p value is from a χ2 test of whether the prevalence of each type of abuse or symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS varies by race/ethnicity

Table 1.

Symptoms Suggestive of CP/CPPS by Demographics and Type of Abuse

| Percent | Odds ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Point estimate | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| Overall | 6.5 | ||

| Age group | (.2322) | (.1943) | |

| 30–39 | 4.2 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 40–49 | 5.6 | 1.36 | 0.56, 3.33 |

| 50–59 | 8.2 | 2.04 | 0.81, 5.14 |

| 60–70 | 11.2 | 2.87 | 0.98, 8.40 |

| 70–79 | 10.2 | 2.58 | 0.92, 7.23 |

| Race/ethnicity | (.9479) | (.9471) | |

| Black | 6.3 | 0.96 | 0.54, 1.72 |

| Hispanic | 6.9 | 1.06 | 0.63, 1.79 |

| White | 6.5 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Childhood sexual abuse | (.1401) | (.0900) | |

| Yes | 9.8 | 1.73 | 0.92, 3.26 |

| No | 5.9 | ||

| Childhood physical abuse | (.0371) | (.0158) | |

| Yes | 10.1 | 1.97 | 1.14, 3.41 |

| No | 5.4 | ||

| Childhood emotional abuse | (.0494) | (.0167) | |

| Yes | 11.2 | 2.19 | 1.15, 4.16 |

| No | 5.5 | ||

| Adult sexual abuse | (.1456) | (.0781) | |

| Yes | 10.6 | 1.89 | 0.93, 3.83 |

| No | 5.9 | ||

| Adult physical abuse | (.0091) | (.0001) | |

| Yes | 14.3 | 3.29 | 1.81, 5.98 |

| No | 4.8 | ||

| Adult emotional abuse | (.0258) | (.0037) | |

| Yes | 12.9 | 2.60 | 1.37, 4.95 |

| No | 5.4 | ||

| Number of types of childhood abuse | (.1189) | (.0363) | |

| 0 | 5.4 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 1 | 5.7 | 1.05 | 0.55, 2.01 |

| 2 or 3 | 11.6 | 2.30 | 1.20, 4.40 |

| Number of types of adult abuse | (.0246) | (.0004) | |

| 0 | 4.9 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 1 | 6.5 | 1.36 | 0.60, 3.09 |

| 2 or 3 | 16.4 | 3.81 | 1.98, 7.34 |

p values are in parenthesis and pertain to: (1) a χ2 test of independence in the Percent column; (2) a logistic regression model in the Point estimate column, and pertain to whether the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS varies by subject demographics and types of abuse

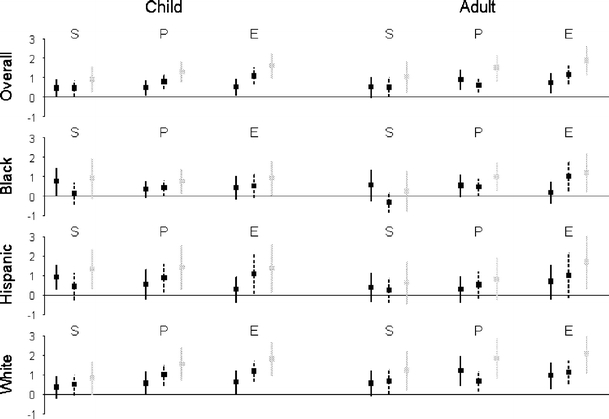

Men reporting sexual, physical, or emotional abuse have increased odds of having symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS. Of the different types of abuse, adult physical abuse was most strongly associated with symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS, Table 1, and this did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity, Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Change in CPSI pain, urinary, pain + urinary score and 95% confidence intervals for different types of abuse. Abuse experienced as a child or as an adolescent/adult: S (sexual), P (physical), E (emotional). CPSI pain score (black line), CPSI urinary score (dashed line), CPSI pain + urinary score (gray line). A line at 0 indicates no effect.

The prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS was significantly higher for men reporting a history of physical or emotional abuse, Table 1. The odds of symptoms of CP/CPPS were higher for men who reported sexual abuse, but this was not statistically significant at the α = 0.05 level. Although we had less statistical power to examine the effect of race/ethnicity on the association of abuse and symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS, the pattern was similar by race/ethnicity (data not shown). We also considered models that included race/ethnicity, age group, and any abuse (odds ratio [OR] = 1.69, p = .07), any childhood abuse (OR = 1.57, p = .10), or any adult abuse (OR = 2.21, p = .01). There was no interaction of abuse and SES on the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS.

Bradford Hill30 suggested that a dose response curve is a criterion that indicates causality. Using a measure of frequency (never, seldom, occasionally, often) for the physical and emotional abuse questions, we examined whether frequency of abuse was associated with prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS. For the questions of hit, kick, and beat, seriously threaten life, and emotionally abuse, greater frequency of both childhood and adult abuse was associated with an increased prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS (at least 3 out of the 4 prevalences were increasing; data not shown). We also examined the number of types of childhood or adult abuse reported (0–3). If a man reported more than 1 type of abuse, he was at increased odds of reporting symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS, Table 1.

All forms of abuse increased both the pain and urinary scores of the NIH-CPSI, Figure 2. There was also increasing trends in both the pain and urinary scores with increasing frequency of physical and emotional abuse (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our study has several important findings. First, abuse was not uncommon in our cohort, ranging from 10% to 30% with significant racial/ethnic variation. The prevalence of abuse in this cohort is similar to other published studies.14,15 Most population-based surveys report a higher prevalence of abuse in women, ranging from 20% to 30%31; however, the reported prevalence of male childhood sexual abuse ranges from 4% to 76%.31,32 In addition, most small-sample studies indicate that the prevalence of sexual abuse is higher in non-White versus White males.33–36 In contrast, we found a higher prevalence of emotional and sexual abuse in Whites, whereas Blacks experienced the highest rates of physical abuse, and Hispanics reported the lowest prevalence of all types of abuse.

Second, symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS were not uncommon in a diverse, urban, community-based population of men. Our estimate of 6.5% of men aged 30–79 falls in the prevalence range of 2% to 10% described in the Olmstead County study cohort3 and Canadian men.2 Furthermore, although symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS were most common in Hispanic men, the prevalence did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity.

Third, men who reported a history of physical and emotional abuse were significantly more likely to experience symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS; however, the presence of any type of abuse increased both the NIH-CPSI pain and urinary scores. Moreover, physical and emotional abuses were independently associated with symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS. Men who suffered multiple (2 or more) types of abuse were also more likely to experience symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS, suggesting a cumulative effect of types of both childhood and adult abuse.

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between physical, emotional37, and sexual abuse with female chronic pelvic pain10,11,38,39; however, evidence associating abuse with male chronic pelvic pain is lacking. An association between male sexual abuse and gastrointestinal complaints has been described; a random survey of men within 1 county in Minnesota showed that sexual abuse was associated with twice the risk of irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia, and heartburn.40 Other studies have demonstrated that sexual abuse is detrimental to men’s health. A meta-analysis examining the impact of child sexual abuse on mental health outcomes (posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, suicide) concluded that men and women were similarly affected by abuse.41 Finally, national probability studies demonstrate that males who have been sexually abused were at greatly increased risk for more physical symptoms,42–44 functional impairment,42 poor subjective health,43,45 eating disorders,46,47 substance disorders,48 and risky behavior.49

Patients with CP/CPPS compared to controls have been shown to have higher scores for a range of psychological factors including anxiety, somatization, and hypochondriasis.50,51 In addition, an observational study demonstrated that 90% of 134 men reported improvement in symptoms of CP/CPPS when only stress-management therapy was given.52 However, the effectiveness of psychological approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy has not been evaluated in CP/CPPS.

Our study has many strengths. It is a community-based random sample, not a convenience sample of patients. It involves a large number of subjects (2,301 men and 3,205 women). It includes a large age range of 30–79 and is racially and ethnically diverse. We have asked questions about many urologic symptoms and have accompanying data on comorbidities, quality of life, medication use, lifestyle, psychosocial factors, and other variables.

Our study has several limitations. A potential limitation is that BACH was conducted in 1 geographic area. Consequently, important racial and ethnic groups (such as Asians and Native Americans) could not be adequately represented. In addition, nonresponse bias may have affected our prevalence estimates. Any nonresponse bias would have entered largely at the screening level, where about two thirds of contacts from selected households either declined screening or could not be reached, despite repeated, diligent efforts. Conversely, once a successful screening process identified 1 or more eligible household members, about two thirds were successfully recruited into BACH. Although response rates have declined for all epidemiologic studies, urologic studies are a “hard sell,” especially among younger and middle age subjects. Furthermore, surveying urologic symptoms may be embarrassing for some subjects. Cellphone use, unlisted numbers, and message machines made it difficult to reach subjects directly, and epidemiologic surveys may be confused with telephone sales solicitations. Understandably, potential subjects may be (especially the elderly) advised to avoid talking to strangers, not to allow them into one’s home, and never to sign anything (BACH involved an in-home interview with signed informed consent). Another potential limitation may be use of the approximations of the validated symptom measure, the NIH-CPSI, to generate the definitions of the CP/CPPS symptom complex. However, we feel that the relatively minor differences in questions should not have a major impact on the prevalence of the CP/CPPS symptom complex. We recognize that questions concerning abuse may be of a sensitive nature. Although the questions were asked in a self-administered questionnaire, we recognize that the validity of self-reported abuse may vary by race/ethnicity. More Hispanics refused to answer these questions (12%–17%) compared to Whites (5%–6%) and Blacks (9%–10%). We also recognize that the definition of abuse may have cultural variability. Our study is based on the data we have.

In conclusion, we found that symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS were not uncommon in a community-based population of men, and the history of abuse increased the odds of having chronic pelvic pain symptoms. Our results suggest that clinicians may wish to screen for abuse in men presenting with symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS. Conversely, clinicians may wish to inquire about pelvic pain in patients who have experienced abuse.

Acknowledgments

BACH was funded by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH, NIDDK) U01DK56842.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Contributor Information

Jim C. Hu, Phone: +1-617-7326907, FAX: +1-617-5663475, Email: jhu2@partners.org.

John B. McKinlay, Email: JMcKinlay@neriscience.com.

References

- 1.Mehik A, Hellstrom P, Lukkarinen O, Sarpola A, Jarvelin M. Epidemiology of prostatitis in Finnish men: a population-based cross-sectional study. BJU Int. 2000;86(4):443–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, Clark J. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study using the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol. 2001;165(3):842–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a community based cohort of older men. J Urol. 2002;168(6):2467–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O’Leary MP, et al. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Turner JA, Ciol MA, Von Korff M, Berger R. Prognosis of patients with new prostatitis/pelvic pain syndrome episodes. J Urol. 2004;172(2):538–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Calhoun EA, McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, et al. The economic impact of chronic prostatitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(11):1231–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: unhealed wounds. Jama. 1997;277(17):1362–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of men with chronic prostatitis: the national institutes of health chronic prostatitis cohort study. J Urol. 2002;168(2):593–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Flor H, Turk DC. Etiological theories and treatments for chronic back pain. I. Somatic models and interventions. Pain. 1984;19(2):105–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Lampe A, Solder E, Ennemoser A, Schubert C, Rumpold G, Sollner W. Chronic pelvic pain and previous sexual abuse. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(6):929–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Reiter RC, Gambone JC. Demographic and historic variables in women with idiopathic chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(3 Pt 1):428–32. [PubMed]

- 12.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Neraas K, Jemelka RP, Massoth D. Dissociation in women with chronic pelvic pain. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):534–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Harrop-Griffiths J, Katon W, Walker E, Holm L, Russo J, Hickok L. The association between chronic pelvic pain, psychiatric diagnoses, and childhood sexual abuse. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(4):589–94. [PubMed]

- 14.Briere J, Elliott DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(10):1205–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Trocme N, et al. Prevalence of child physical and sexual abuse in the community. Results from the Ontario Health Supplement. Jama. 1997;278(2):131–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(11):828–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bailey BE, Freedenfeld RN, Kiser RS, Gatchel RJ. Lifetime physical and sexual abuse in chronic pain patients: psychosocial correlates and treatment outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(7):331–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Linton SJ. A population-based study of the relationship between sexual abuse and back pain: establishing a link. Pain. 1997;73(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mustard CA, Kalcevich C, Frank JW, Boyle M. Childhood and early adult predictors of risk of incident back pain: Ontario Child Health Study 2001 follow-up. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(8):779–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Green CR, Flowe-Valencia H, Rosenblum L, Tait AR. The role of childhood and adulthood abuse among women presenting for chronic pain management. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(4):359–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.McMahon MJ, Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Mayer TG. Early childhood abuse in chronic spinal disorder patients. A major barrier to treatment success. Spine. 1997;22(20):2408–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Mckinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: Design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007 Aug;52(2):389–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, Jr., et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162(2):369–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med. 1995;21(3):141–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85(9):815–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Kish L. Survey Sampling. New York: Wiley; 1965.

- 27.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Survey. New York: Wiley; 1987.

- 28.Schafer J. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997.

- 29.Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques, 3rd edn. New York: Wiley; 1977.

- 30.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Holmes WC, Slap GB. Sexual abuse of boys: definition, prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management. Jama. 1998;280(21):1855–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Finkelhor D. Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. Future Child. 1994;4(2):31–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Moore KA, Nord CW, Peterson JL. Nonvoluntary sexual activity among adolescents. Fam Plann Perspect. 1989;21(3):110–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Muram D, Dorko B, Brown JG, Tolley EA. Child sexual abuse in Shelby County, Tennessee: a new epidemic? Child Abuse Negl. 1991;15(4):523–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Reinhart MA. Sexually abused boys. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(2):229–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Resnick MD, Blum RW. The association of consensual sexual intercourse during childhood with adolescent health risk and behaviors. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6 Pt 1):907–13. [PubMed]

- 37.Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. Bmj. 2006;332(7544):749–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Walling MK, Reiter RC, O’Hara MW, Milburn AK, Lilly G, Vincent SD. Abuse history and chronic pain in women: I. Prevalences of sexual abuse and physical abuse. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(2):193–9. [PubMed]

- 39.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Hansom J, et al. Medical and psychiatric symptoms in women with childhood sexual abuse. Psychosom Med. 1992;54(6):658–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1040–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. J Psychol. 2001;135(1):17–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Golding JM. Sexual assault history and limitations in physical functioning in two general population samples. Res Nurs Health. 1996;19(1):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer D, Plant EA, Arnow B. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and the 1-year prevalence of medical problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Health Psychol. 2005;24(1):32–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Bendixen M, Muus KM, Schei B. The impact of child sexual abuse—a study of a random sample of Norwegian students. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18(10):837–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Golding JM, Cooper ML, George LK. Sexual assault history and health perceptions: seven general population studies. Health Psychol. 1997;16(5):417–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Beuhring T, Resnick MD. Disordered eating among adolescents: associations with sexual/physical abuse and other familial/psychosocial factors. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(3):249–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Laws A, Golding JM. Sexual assault history and eating disorder symptoms among White, Hispanic, and African-American women and men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(4):579–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(5):753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Simmons KW. Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult HIV-risk behaviors and heavy drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(2):151–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Berghuis JP, Heiman JR, Rothman I, Berger RE. Psychological and physical factors involved in chronic idiopathic prostatitis. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41(4):313–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Jarvinen H, Lehtonen T. Psychic disturbances in patients with chronic prostatis. Ann Clin Res. 1981;13(1):45–9. [PubMed]

- 52.Miller HC. Stress prostatitis. Urology. 1988;32(6):507–10. [DOI] [PubMed]