Abstract

In 1991, a novel robot, MIT-MANUS, was introduced to study the potential that robots might assist in and quantify the neuro-rehabilitation of motor function. MIT-MANUS proved an excellent tool for shoulder and elbow rehabilitation in stroke patients, showing in clinical trials a reduction of impairment in movements confined to the exercised joints. This successful proof of principle as to additional targeted and intensive movement treatment prompted a test of robot training examining other limb segments. This paper focuses on a robot for wrist rehabilitation designed to provide three rotational degrees-of-freedom. The first clinical trial of the device will enroll 200 stroke survivors. Ultimately 160 stroke survivors will train with both the proximal shoulder and elbow MIT-MANUS robot, as well as with the novel distal wrist robot, in addition to 40 stroke survivor controls. So far 52 stroke patients have completed the robot training (ongoing protocol). Here, we report on the initial results on 36 of these volunteers. These results demonstrate that further improvement should be expected by adding additional training to other limb segments.

Index Terms: Neurorehabilitation, rehabilitation robotics, stroke, wrist robot

I. INTRODUCTION

EACH year, about 700 000 Americans suffer a stroke [1], making it the third most frequent cause of death and the leading cause of permanent disability in the country. The damage to the central nervous system (CNS) caused by stroke can lead to impaired motor control on the affected side (hemiparesis). The natural history of poststroke motor recovery reveals a dynamic process traditionally described as a period of flaccidity followed by changes including hyperactive stretch reflexes, increased resistance to passive movement due to changes in the passive mechanical properties of muscle (spasticity), hypo-extensibility of the muscle–tendon contracture, as well as the frequent development of synkinesis or associated movement. This synkinesis is characterized by involuntary, composite movement patterns that accompany an intended motor action [2]. Complete motor recovery, when it occurs, will unfold rapidly. However, the more commonly observed partial recovery unfolds over longer periods that range from 2 to 11 weeks [3], [4].

Despite some promising developments in acute stroke treatment [5], most survivors remain burdened with significant and permanent residual physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments. Although interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs focus on impairment as well as disability, shorter inpatient hospitalizations shift program emphases toward compensatory techniques that facilitate functional abilities [6]. Recent data suggest that hasty compensation for impaired motor skills engenders a pattern of disuse that can mute the potential for future improvements in motor ability or function [7]–[10]. Current studies take a balanced approach and, while focusing on impairment and disability outcomes, have used task specific training techniques to influence stroke recovery [11]–[13].

Our treatment focus has been on hastening and managing impairment reduction via movement therapy [14]–[17]. The human brain is capable of self-reorganization, or plasticity. Afferent and efferent limb stimulation can lead to synaptogenesis and the re-establishment of the neural pathways that control volitional movement, potentially leading to impairment reduction, added functional capabilities, and reduced disabilities.

Conventional therapy generally involves one-on-one interaction with a therapist who assists and encourages the patient through repetitive exercises. The repetitive nature of therapy makes it amenable to administration by properly designed robots. A robotic therapist can act as a modern, effective, and novel tool that delivers a reproducible motor learning experience, quantitatively monitors and adapts to patients’ progress, and ensures consistency in planning a therapy program. MIT-MANUS, developed at the Newman Laboratory for Biomechanics and Human Rehabilitation at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, was developed as a test-platform for the study of human motor control and recovery as well as a tool for the administration of physical or occupational therapy. It is a planar, two-degree-of-freedom robot providing exercises to the upper extremity as the patient completes a series of “video games” that involve positioning the robot end effector. The design of this robot, completed in 1991, is based on a five-bar, parallel drive selective compliance assembly robot arm (SCARA). By minimizing the endpoint impedance of the robot, the feel of the robot can be modulated through control, allowing safe patient interaction and without excessively interfering with the patient’s natural arm dynamics. The controller sets up a virtual spring and damper between the task-defined, time-dependent equilibrium point and the position of the end effector [18].

Clinical trials involving MIT-MANUS (see Fig. 1) and its commercial version have shown that robot-aided neuro-rehabilitation has a positive impact, reducing impairment in both in-patients and outpatients [19]–[26]. The results of these studies, as measured by standard clinical instruments, showed statistically significant improvement in impairment at the shoulder and elbow (the focus of the exercise routines), but no change at the wrist and fingers (which were not exercised). This result suggests a local effect with limited generalization of the benefits to the unexercised limb or muscle groups. According to the notion of task specificity, improvements due to rehabilitation are focused on a targeted limb, so that in order for a patient to relearn a given task, each required limb segment for that task must be rehabilitated. If this is true, the shoulder-and-elbow robotic-assistance should be expanded to exercise different groups of muscles and limb segments. New modules have, therefore, been designed for rehabilitation of the wrist, hand, and fingers, ankle, and pelvis. This paper focuses on the design and characterization of a wrist robot, as well as on the initial clinical results of training with the shoulder-and-elbow MIT-MANUS, as well with the robot for wrist rehabilitation. The proximal shoulder and elbow play a critical role in the transport of the arm. Wrist and forearm articulation play an important role in enhancing the usefulness of the hand by allowing it to take a variety of orientations with respect to the elbow (poses), which are critical for object manipulation.1,2

Fig. 1.

Planar shoulder-and-elbow robot during clinical trials at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital.

II. DESCRIPTION OF THE WRIST ROBOT

The wrist robot has three active degrees-of-freedom (DOF): abduction–adduction; flexion–extension; pronation–supination. This unique 3-DOF robot can be operated standalone (see Fig. 2) or mounted at the tip of our companion planar robot, MIT-MANUS, allowing five active DOF (plus two passive DOF) at the shoulder, elbow, and wrist (see Fig. 3).3 The two robots also allow us to verify whether outcomes are affected by the training sequence to different limb segments; in particular, the proximal versus distal training, which is the focus of the NICHD-NCMRR sponsored research. Proximal limb segments are responsible for limb transport, while the distal limb segments are responsible for object manipulation. There is evidence that the CNS might act through different pathways on different limb segments. The CNS appears to act on shoulder and elbow segments via the rubrospinal pathway [30], [31], while it acts on the more distal wrist and hand via the pyramidal tracts. Conventional therapy focuses on training of the proximal limb segments first, since the process of neurorecovery typically progresses from proximal to distal limb segments. Owing to this sequence, however, a possible opportunity to harness synapses for distal limb segment control may be diminished or even lost. If so, conventional therapy maybe forgoing a significant opportunity in the competition for the brain’s precious “real-estate.”

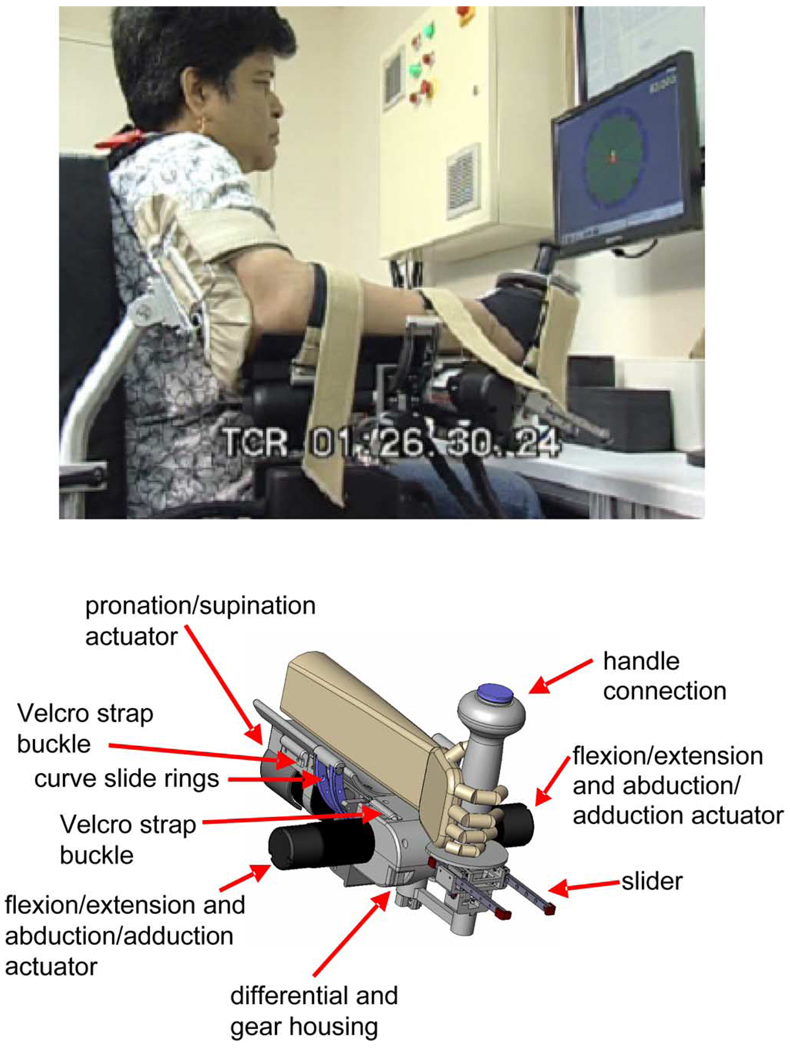

Fig. 2.

Wrist robot. Top figure shows a stroke survivor during therapy sessions at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital. Bottom figure shows a solid view of the design.

Fig. 3.

Whole-arm robot. The wrist robot can be added to the tip of the planar robot affording five active DOFs (and two passive DOFs) for transport of the arm and manipulation.

It is of paramount importance that a robotic rehab wrist device be easy for the therapist and the patient to use. To prevent daily use from becoming a chore for the patient and the therapist, only a minimum amount of time and effort must be required to attach and remove the patient from the wrist device. The target setup time was estimated at 2 min maximum. At the time of completion of MIT-MANUS in 1991, we also completed an initial version of a wrist module [18]. While this initial wrist module could achieve the design targets, it suffered from a significant handicap: it took too long to secure the hand of stroke patients onto the device. The patient’s hand had to be maneuvered through an opening and it proved to be particularly slow and tedious to position the hand of a patient with hypertonia. Hence, the device was deemed inadequate to treat the stroke population.

Another key aspect is low endpoint impedance. That is, when a patient attempts to backdrive the robot, the effective friction, inertia, and stiffness should be low enough to feel as if no robot were connected. In this case, the robot hardware is termed “backdrivable.” The maximum reflected inertia for backdriveability of the device for each wrist degree of freedom was estimated to be 30 × 10−4 to 45 × 10−4 kg · m2. The maximum reflected friction for backdriveability was estimated to be 0.29 Nm for pronation/supination and 0.075 Nm for flexion/extension and abduction/adduction. The ranges of motion (ROM) matches the ROM of a normal wrist in everyday tasks, i.e., flexion/extension 60°/60°, abduction/adduction 30°/45°, pronation/supination 70°/70°. The torque output from the device must be capable of lifting the patient’s hand against gravity, accelerating the inertia, and overcoming any tone. Maximum torque for flexion/extension and abduction/adduction is 1.43 Nm and for pronation/supination 1.85 Nm. Achievable impedances range from 0 to 60 Nm/rad and 0 to 1 Nm/rad/s for pronation/supination and 0 to 40 Nm/rad and 0 to 0.45 Nm/rad/s for flexion/extension and abduction/adduction.4 A summary of the design choices has been previously reported elsewhere [32]–[38].

Fig. 2 shows the robot during clinical trials. Even for severe spasticity, it takes less than 2 min for setup. The patient’s fist must be loosened slightly and the hand is dropped in place. The two side-mounted actuators are connected to a differential mechanism, which allows for flexion/extension, abduction/adduction movements and their combinations. Joint torque production on the differential is a result of the proper combination of motor torques. Each motor contributes equal components of vertical and horizontal motion of the handle when actuated. When the two motors cooperate, motion is purely abduction/adduction; when the motion generated from these two motors opposes each other, the resulting motion is flexion/extension. The entire differential mechanism is mounted onto a curved rack so that it can be actuated from beneath the forearm, enabling pronation and supination movements. This qualitative description can be summarized by the equations [33]

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where θlong and θlat are the longitude and latitude of the robot arm, θ̃R and θ̃L are the rotation of the right and left differential end gears referenced to a neutral handle position,5 and τlong, τlat, τ̃R, and τ̃L are the corresponding torques. During therapy, the patient’s wrist is positioned over the spider gear,6 so that θlong is equal to the angle of wrist flexion and extension. Abduction/adduction is accommodated through the handle kinematics; the handle is attached to the robot arm through a linear ball slide guide which can pivot. The entire handle mechanism can pivot about one orthogonal axis. This results in a one-to-one mapping between θlat and wrist abduction/adduction, with the precise relationship determined by the geometry of the patient. Here, we present the characterization of the prototype robot’s subsystems and achievable impedances.

A. Actuator Characterization

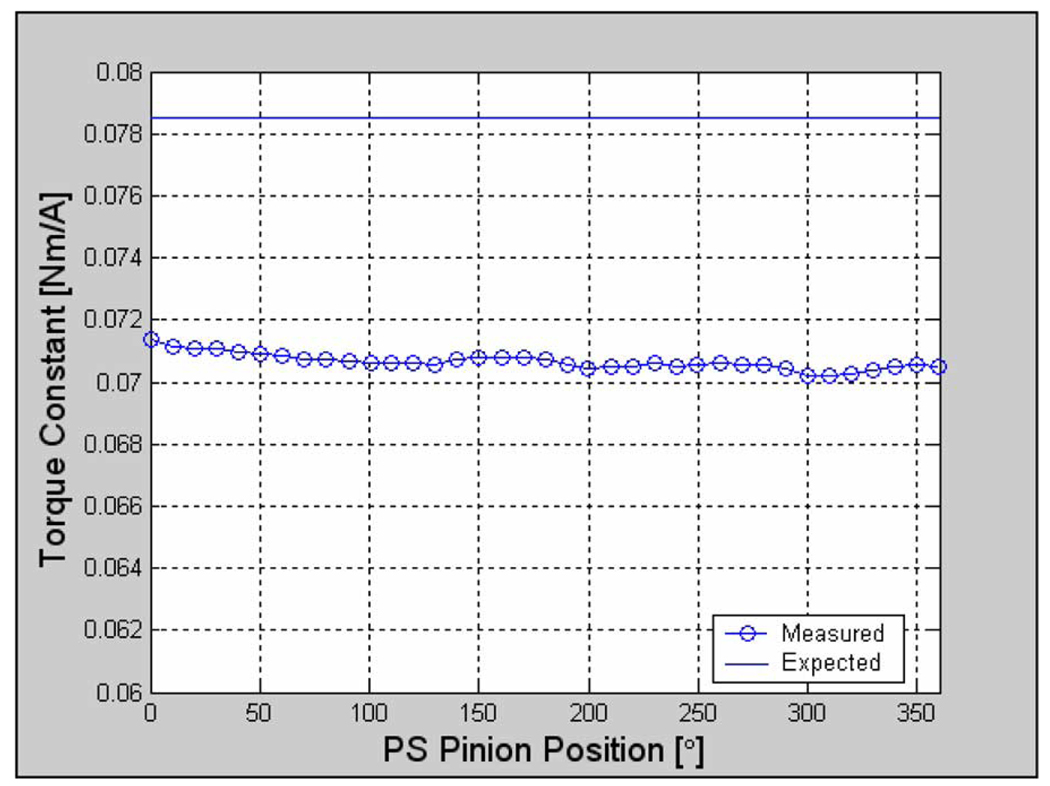

The pronation/supination (PS) motor is a MAXON motor, model #136201. Product specification sheets list the maximum continuous torque of this motor at 176 mNm and the motor constant at 78.5 mNm/A. The differential right and left motors (ADR and ADL, respectively) are each MAXON model #118899 motors with a published maximum continuous torque of 101.8 mNm and torque constant of 145 mNm/A. Static torque tests were performed by inputting a slow sinusoidal voltage and measuring the torque with an ATI Gamma FT US 30/100 force transducer. The resulting positional dependence of the torque constant is plotted in Fig. 4 for pronation/supination; the motor has no discernable torque ripple. The measured torque constant is less than the published value, and similar results were observed for the motors employed to drive the differential.

Fig. 4.

PS motor torque constant as a function of position. The difference in readings at 0° and 360° can be attributed to the experimental variability in the force transducer readings.

Static and dynamic friction values were investigated using ramp tests. Testing the ramp response over many velocities produced a number of plots with distinct loci of points of interest. Points near low velocities gave a good estimate of the static friction in the motor, while outer points at higher speeds provided estimates of the dynamic friction. Our experimental results suggested that outside the low speed region, friction is predominantly characteristic of Coulomb friction.

To determine inertia and Coulomb friction we employed step tests. The natural frequency was used to estimate the rotor inertia, and the linear decay of the step test was used to estimate Coulomb friction (see Table I for results). In this table, τ is a friction torque, with the subscript s standing for static friction, the subscript k standing for Coulomb friction, the superscript + representing movement in the positive direction, and the superscript − representing movement in the negative direction. The friction values given are averages.

TABLE I.

SUMMARY OF OBSERVED ROTOR PROPERTIES

| Axis | J [10−6kg·m2] |

[10−3Nm] |

[10−3Nm] |

[10−3Nm] |

[10−3Nm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADR | 6.53 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| ADL | 6.66 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| PS | 10.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

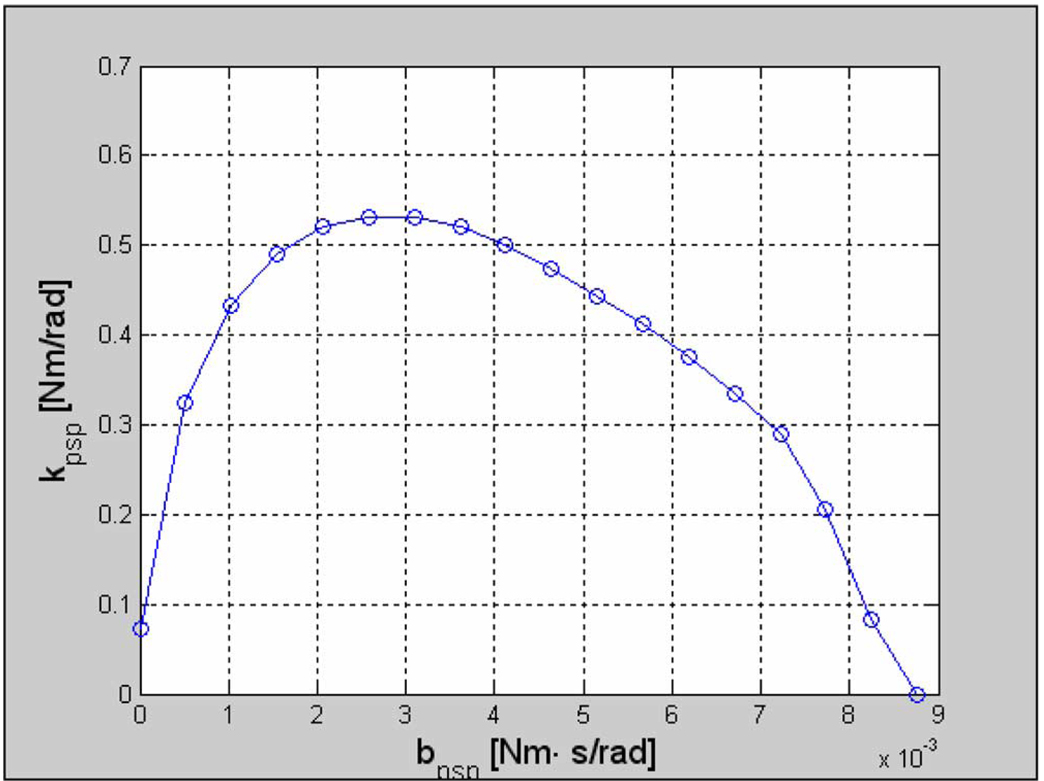

Stability tests were carried out on the free rotors (see Fig. 5), as well as on the assembled robot at the end-effector (results discussed later). The stability test involved prescribing a stiffness and damping to the axis and running a step test on the rotor. In this free rotor configuration, a simple second-order system with a few nonlinearities can model well the observed behavior (namely: coulomb friction, discretization, and actuator saturation) [33].

Fig. 5.

PS motor stability map (the region below the curve is considered stable). Note that the stability conditions apply only to the conditions tested (step size of 50°). The system behaves differently to different sized inputs (a trademark of a nonlinear system). The values of stiffness and damping shown are for the free motor with the pinion and do not represent the stability limits of the assembled system.

B. System Characterization

We employed the step and ramp tests to characterize the assembled wrist robot. Here, we focus on determining axis inertia, static and coulomb friction, and gravity terms. Table II summarizes robot measured properties when actuating one DOF at a time: abduction/adduction (AD), flexion/extension (FL), and pronation/supination (PS). The last column of this table presents an estimate of the gravity term. For the AD axis, this gravity compensation is assumed to be constant, while for the PS axis, the table figure is multiplied by sin(θps).

TABLE II.

SUMMARY OF ROBOT PROPERTIES

| Axis | J [10−3kg·m2] |

[Nm] |

[Nm] |

[Nm] |

[Nm] |

mgl [Nm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 3.1 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.020 | 0.025 | 0.3 |

| FL | 4.0 | 0.020 | 0.060 | 0.032 | 0.033 | – |

| PS | 5.8 | 0.210 | 0.230 | 1.240 | 0.760 | 1.1 |

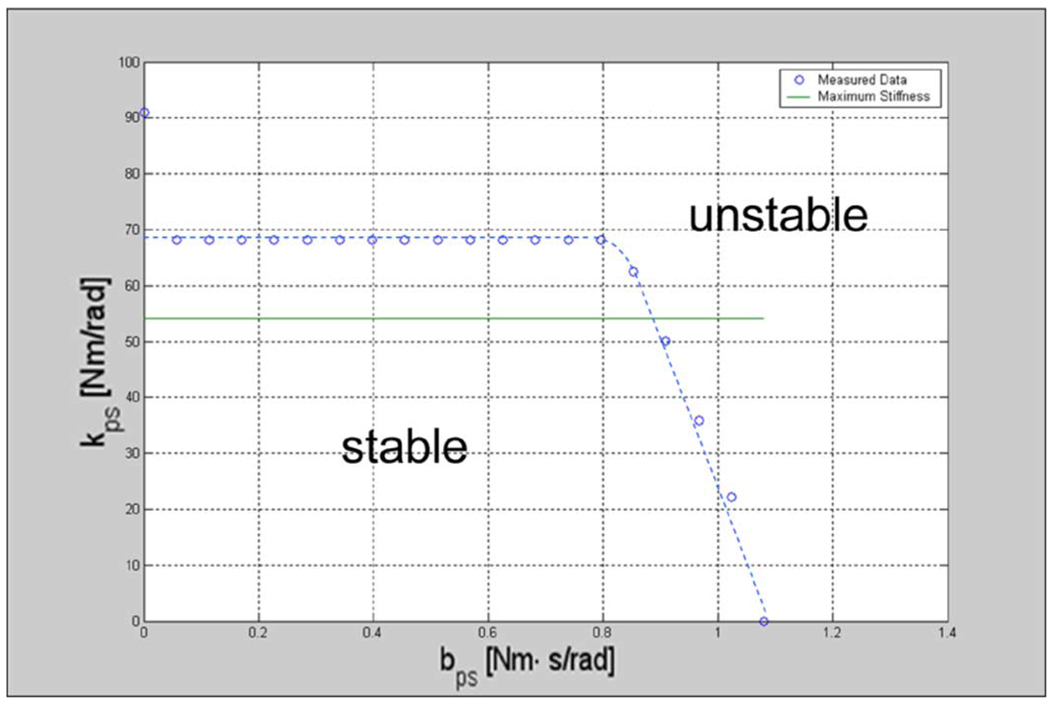

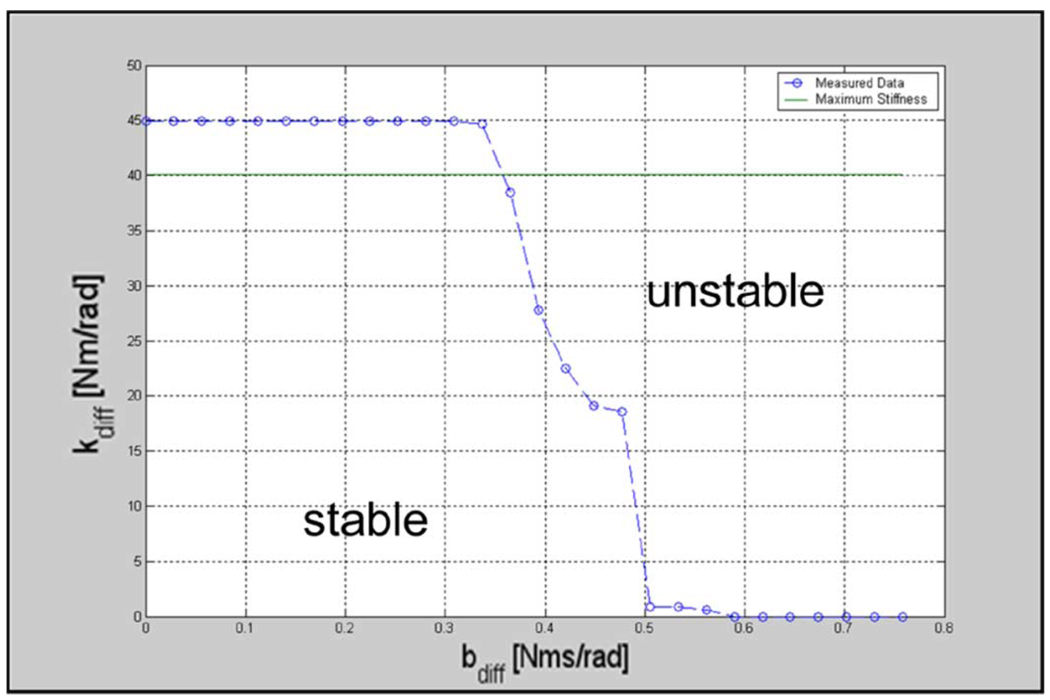

Testing for endpoint stability involved exciting the system via PD controlled input steps in position. Stability tests and maps are shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. The line on each map indicates the maximum perceivable stiffness, which was estimated as the maximum actuator torque divided by the just noticeable difference (JND) for change in position for the wrist and forearm rotations. We used a JND value of 2° [39]. If the system was stable for a stiffness above this line at a given damping, it was considered stable at “any” stiffness at that damping. The threshold acts as a marker for a haptic perception of “infinite” stiffness.

Fig. 6.

Robot PS stability map. Region under the curve represents the stability region.

Fig. 7.

Robot differential stability map (flexion/extension, abduction/adduction and its combinations). Region under the curve represents the stability region.

From this testing, it is apparent that the mechanism is dominated by the effects of gravity and backlash in the gear train.

III. ONGOING TRIAL—PROXIMAL VERSUS DISTAL TRAINING

Robotic wrist therapy is administered through interactive video games comparable to those used with MIT-MANUS. The 3-DOF provided by the wrist robot are mapped into a two-dimensional graphical display on a monitor screen.

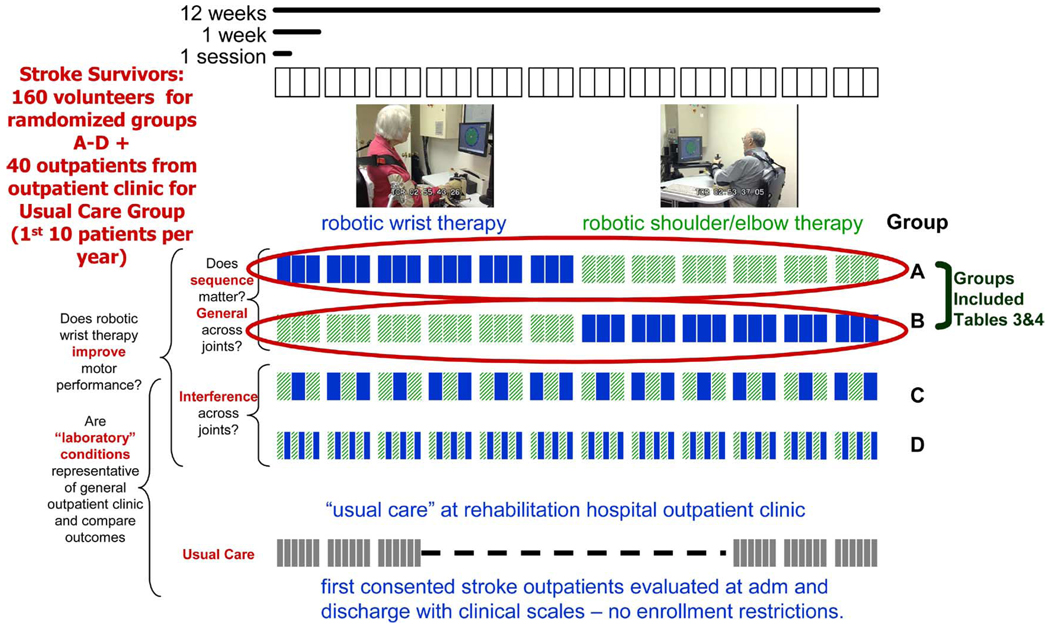

To compare the effects of specifically training proximal versus distal limb segments, we have begun a study in which we recruit naive persons with chronic impairments after stroke (i.e., never trained on the robot before). Outpatients are included in the study if they meet the following criteria: the subject 1) has a first single focal unilateral lesion with diagnosis verified by brain imaging (MRI or CT scans) that occurred at least six months prior; 2) has cognitive function sufficient to understand the experiments and follow instructions (Mini-Mental Status Score of 22 or higher or interview for aphasic subjects); 3) has a motor power (MP) score ≥1/5 and <4/5 (neither hemiplegic nor fully recovered motor function in the muscles of the shoulder and elbow and wrist); 4) is naive in that he/she has never experienced robot-assisted therapy; 5) has given informed written consent to participate in the study. Patients are excluded from the study if they have a fixed contraction deformity in the affected limb. Trials commence only after baseline assessment across three consecutive evaluations, two weeks apart, shows a stable condition in motor impairment scales [Fugl–Meyer (F-M) and MP]. Patients qualified for robot therapy are randomly assigned to one of four groups7 (see Fig. 8):

Fig. 8.

Proximal-versus-distal robot training protocol.

Six weeks of robot-delivered wrist therapy followed by six weeks of robot-delivered shoulder-and-elbow training (three times per week: 36 sessions total).

Six weeks of shoulder-and-elbow training followed by six weeks of wrist training (three times/week: 36 sessions).

Twelve weeks of alternating days of shoulder-and-elbow and wrist training (with at least 24 hours between alternations) using the planar and wrist robots in standalone mode (three times/week: 36 sessions).

Twelve weeks of training with half of the day’s session focusing on shoulder-and-elbow training and half of the session focusing on wrist training (three times/week: 36 sessions) using the planar and wrist robots in standalone mode.

For the shoulder-and-elbow training, the patient is seated with the robot aligned with the patient’s midline and the hand placed into a hand holder with fingers curled around a handle. A four-point seatbelt is tightened to minimize movement of the torso. Elbow support is provided during all training and evaluation procedures with the exception of force measurements. The elbow is supported at 40° flexion when resting on center target. The proximal-to-distal shoulder-and-elbow protocol consists of three batches of 320 “assisted-as-needed” point-to-point movements from a center to eight outbound targets distributed along a circle. The assistance is tuned based on patient’s performance (for the description of the performance-based control algorithm see [40]). Each assisted batch is preceded and succeeded by an unassisted game [18].

For the wrist training, the patient is seated with the robot to his side and is secured at the hand, wrist, and above the elbow. The workstation is meant to fit the patient comfortably with around 20° of shoulder abduction and 30° of shoulder flexion. The forearm rests comfortably on a curved rest so that the ulnar styloid sits barely beyond the distal edge. The hand is secured to the handle in a comfortable composite flexion grip with the least restrictive support provided. Humeral and forearm supports are supplied to maintain snug support. A four-point seat-belt is tightened to minimize movement of the torso. As with the shoulder-and-elbow protocol, the proximal-to-distal wrist protocol also consists of three batches of 320 “assisted-as-needed” point-to-point movements. Each assisted batch is preceded and succeeded by an unassisted game and the assistance is tuned based on patient’s performance (see [40] for the description of the performance-based control algorithm). The first two assisted batches exercise wrist flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and combination of these movements with eight outbound targets distributed around an ellipse with major axis of 60° (30° for flexion-extension each) and minor axis of 30° (15° for adduction/abduction each). The last assisted batch exercises exclusively pronation and supination (30° for pronation/supination each).

The first two groups (groups a and b) may answer the question posed earlier of whether harnessing the proximal shoulder-and-elbow first limits the potential recovery of the more distal wrist. The other two groups (group c and d) were intended to provide further evidence that a model of motor learning might be used to guide a model of neuro-recovery. In particular, they are intended to test interference [41].

A characteristic of motor learning is that two distinct tasks, trained in close temporal proximity, will interfere with each other; the performance gains obtained on the first task will be eroded or eliminated by training on the second task. The latter groups (c and d) allow us to test whether subjects training daily on both transport and manipulation concurrently achieve better outcomes than subjects training on the two tasks in alternate sessions. If we do not find that performance is degraded in the second group (group d), it will demonstrate either that this characteristic of motor learning is not shared by motor recovery, or that the effect is too subtle to be detected by the means we used. Conversely, if we find a degradation of performance, it will provide further evidence of a quantitatively measurable parallel between motor learning and motor recovery. Note that we are not attempting here to elucidate whether the mechanism of motor consolidation, if present, is due to time elapsed since training at a different task [41] or due to sleep [42].

In addition to the 160 volunteers receiving robot training, we are enrolling 40 stroke survivors of Burke Rehabilitation Hospital’s (White Plains, NY) outpatient clinic (first ten subjects per year, who consent to participate). This group receives only the standard care. We evaluate these outpatient clinic volunteers using the same clinical instruments as the robot-trained groups. Goals are twofold: first, to determine whether our self-selected highly motivated subjects enrolled in robot training are representative of the general stroke population receiving therapy at a rehabilitation hospital’s outpatient clinic and, second, to compare improvement in the robot-trained subjects versus these outpatients receiving usual-care at Burke’s outpatient clinic.

In this paper, we report results from the initial 36 subjects enrolled in groups a and b. Seventeen naive stroke outpatients with no previous exposure to robot therapy were enrolled in group a and have received six weeks of training on the wrist robot (three sessions/week) followed by six weeks of training on the planar robot (three sessions/week) at the Burke Rehabilitation Hospital, and 19 outpatients were enrolled in group b and received training in the reverse order. Of these initial 36 patients in groups a and b, the average age was 60.5 ± 2 years old (mean ± sem, range 28–82) with the onset of the stroke occurring 2.35 ± 0.31 years prior to enrollment (mean ± sem, range 0.88–7.97 years). Admission F–M score (max/66) for these 36 patients was 17.35 ± 1.73 (mean ± sem) with a range in the three pretreatment evaluations of 4–38. Table III shows the results for the shoulder-and-elbow and wrist-and-fingers subcomponents of the UE FM and MP scale expanded to incorporate wrist muscle groups (max/90). We opted not to run any meaningful statistics until we complete recruitment for these two groups, which is expected by summer of 2007, but the results are quite promising. First, as in our previous trials with chronic stroke, we observed a drop in tone as measured by the modified Ashworth Scale (6.85 ± 0.70 and 4.5 ± 0.53 mean ± sem adm and disch, respectively) [43]. Second, while this protocol lasts longer than our past studies, it is encouraging to see improvements 20%–100% larger than our own past studies with a similar population8 [24]–[26]. Preliminary analysis nevertheless suggests that the order of therapy focus on proximal followed by distal segments or vice-versa has no impact on total F–M change. F-M change in the 12 week program reduces patients’ impairment by roughly 10% of the absolute scale (end-of-scale 66) for both groups. However, a more careful analysis appears to elucidate a more insightful view of the impact of order effect. Table IV shows the amount of skill transferred due to the shoulder and elbow training to the untrained wrist and vice-versa. Training the more distal wrist first appears to lead to a higher skill transfer to the more proximal segments than vice-versa. We speculate that perhaps the patient, albeit restrained, is also working very hard at the proximal segments. One must take this preliminary observation with the appropriate caveat as the study is still ongoing.

TABLE III.

CLINICAL SCORES OF THE ONGOING STUDY

| Timeline Group A (N1=17) wrist 6wks shoulder&elbow 6wks |

Change Admission to Discharge of Wrist Training (mean±sem) |

Change Admission to Discharge of Planar Training (mean±sem) |

Total Change (mean+sem) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-M s/e (/42) | 2.23 ± 0.44 | 1.18 ± 0.43 | 3.41 ± 0.61 |

| F-M w/h (/24) | 1.94 ± 0.84 | 1.17 ± 0.48 | 3.12 ± 1.16 |

| MP (/90) | 1.96 ± 0.80 | 2.88 ± 0.95 | 4.84 ± 1.03 |

|

Timeline Group B (N2=19) shoulder&elbow 6wks wrist 6wks |

Change Admission to Discharge of Planar Training (mean+sem) |

Change Admission to Discharge of Wrist Training (mean±sem) |

Total Change (mean±sem) |

| F-M s/e (/42) | 3.79 ± 0.52 | 1.05 ±0.34 | 4.84 ± 0.54 |

| F-M w/h (/24) | 0.54 ± 0.45 | 1.42 ± 0.42 | 1.96 ± 0.73 |

| MP (/90) | 3.26 ± 0.92 | 1.58 ± 0.60 | 4.84 ± 0.90 |

TABLE IV.

SKILL TRANSFER OF THE ONGOING STUDY

| Timeline Group A (N1=17) wrist 6wks shoulder&elbow 6wks |

Skill Transfer Admission to Discharge Wrist Training (% of scale) |

Skill Transfer Admission to Discharge Planar Training (% of scale) |

Total Change (%of scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-M s/e (/42) | 5.3 | 2.8 | 8.1 |

| F-M w/h (/24) | 8.1 | 4.9 | 13 |

|

Timeline Group B (N2=19) shoulder&elbow 6wks wrist 6wks |

Skill Transfer Admission to Discharge Planar Training (% of scale) |

Skill Transfer Admission to Discharge Wrist Training (% of scale) |

Total Change (% of scale) |

| F-M s/e (/42) | 9.0 | 2.5 | 11.5 |

| F-M w/h (/24) | 2.2 | 5.9 | 8.1 |

The first observation is that six weeks of training focused on a particular limb segment shows no indication that further potential of improvement in that particular limb is exhausted, as we did not hit any “plateau.” Further improvement in that particular limb segment was observed in the subsequent six-week training period. Among naive outpatients, who had never experienced robot training, the improvement is on the order of 8%–9% on the trained limb segment when first experiencing robot training, and 11.5%–13% following total training. The second limb segment to be trained improved a total of 8.1%. The picture gets far more interesting upon analysis of generalization and skill transfer. Training of the more distal limb segments leads to twice as much carryover effect to the proximal segments than in the reverse order of training (see Table IV). Furthermore, it appears that improvement in more distal segments continues significantly even without further training for that limb segment, as demonstrated by the larger improvement of the distal segment of outpatients while training the shoulder and elbow (group a). We expect that the four-month followup results will likely provide an even richer insight as will the robot-based measurements.

IV. Conclusion

The development and success of MIT-MANUS as a robotic aid for neuro-rehabilitation has prompted the development of new robotic devices targeting motions often affected by stroke. This paper provides an overview of the transition of the wrist robot from its design to its implementation as a clinical device. The wrist robot is capable of providing continuous passive motion, strength, sensory, and sensorimotor training for the wrist. In its final form, this device will offer insights into human motor control and human learning, as well as the potential for customizable, adaptive, and rigorously quantified therapy in solo operation or mounted at the tip of the planar MIT-MANUS.

Of notice in this initial clinical application employing both the shoulder and elbow robot and the wrist robot, we observed improvement of the order of 10% in a 12-week program of 36 sessions. This kind of improvement in persons with severe to very-severe chronic impairment (mean F–M at admission 17.35 ± 1.73) due to stroke is remarkable and very promising. These clinical changes far exceed the minimum impairment change of three points in the F–M, which appears to be necessary to achieve significant functional changes [44].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NICHD-NCMRR under Grant 1 R01-HD045343. The work of S.K.Charles was supported by the HST MEMP Fellowship.

Biography

Hermano Igo Krebs (M’96–SM’06) received the electrician degree from Escola Tecnica Federal de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 1976, the B.S. and M.S. degrees in naval engineering (option electrical) from University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 1980 and 1987, respectively. He received the M.S. degree in ocean engineering from Yokohama National University, Yokohama, Japan, in 1989, and the Ph.D. degree in ocean engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, in 1997, with the thesis: “Robot-aided neuro-rehabilitation and functional imaging.”

He joined the Mechanical Engineering Department, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in 1997, where he is a Principal Research Scientist and Lecturer—Newman Laboratory for Biomechanics and Human Rehabilitation. He also holds an affiliate position as an Adjunct Professor at University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Neurology and as Adjunct Assistant Research Professor of Neuroscience at Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York. He is one of the founders of Interactive Motion Technologies, a Cambridge-based startup company commercializing robot technology for rehabilitation. From 1977 to 1978, he taught electrical design at Escola Tecnica Federal de Sao Paulo. From 1978 to 1979, he worked at University of Sao Paulo in a project aiming at the identification of hydrodynamic coefficients during ship maneuvers. From 1980 to 1986, he was a surveyor of ships, offshore platforms, and container cranes at the American Bureau of Shipping, Sao Paulo. In 1989, he was a visiting researcher at Sumitomo Heavy Industries-Hiratsuka Laboratories, Japan. From 1993 to 1996, he worked at Casper, Phillips & Associates in container cranes and control systems. His present goal is to revolutionize the way rehabilitation medicine is practiced today by applying robotics and information technology to assist, enhance, and quantify rehabilitation; particularly neurorehabilitation. This goal translates into research interests in neurorehabilitation, functional imaging, human–machine interactions, robotics, and dynamic systems modeling and control.

Bruce T. Volpe received the B.S. and M.D. degrees from Yale University, New Haven, CT, in 1969 and 1973, respectively.

He trained in medicine and neurology at the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Columbia University, New York, and Cornell University, New York. He is a Lecturer in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, and also a member of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Cornell University. He is now a Professor of Neurology and Neuroscience at Weill Medical College, Cornell University, where he has continued his interest in neuroplasticity especially as it pertains to recovery from stroke. He has been very lucky to be able to work with the engineers at MIT where the team has developed novel strategies to improve the training protocols to encourage motor learning and recovery. He also has a long standing interest in preclinical models of brain injury and has become fascinated by the neurotoxicity of autoantibodies. Recently, with a group of immunologists, they have described an anti-DNA, anti-NMDA receptor antibody that may play a role in autoimmune diseases of the brain.

Dustin Williams received the B.S. degree in mechanical engineering from University of California, Los Angeles, where he graduated summa cum laude, and he received the M.S. degree in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, where he graduated at the top of his class.

Following MIT, he worked as a Research and Development Engineer for Intuitive Surgical, where he helped develop a new line of endowrist instruments. He has since worked at Interactive Motion Technologies (IMT) as an Research and Development Engineer and Operations Manager for the ankle, shoulder/elbow, wrist, hand, and antigravity machines. IMT commercializes the rehabilitation machines developed by MIT’s Newman Laboratory.

James Celestino was a M.S. student at the Newman Laboratory for Biomechanics and Human Rehabilitation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

He is currently working as an engineer in the medical device industry.

Steven K. Charles received the B.S. degree in mechanical engineering from Brigham Young University, Provo, UT and the M.S. degree in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge. He is currently working toward the Ph.D. degree in mechanical and medical engineering at the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge. His doctoral research investigates the biomechanics and neural control of wrist rotation, particularly in comparison to what is known about reaching movements.

Mr. Charles is a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the Society for Neuroscience (SfN), and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).

Daniel Lynch received the B.S. and M.S. degrees from Dominican College, Orangeburg, NY, in 2001, and the M.B.A. degree from Long Island University, Purchase, NY, in 2006.

He was an Occupational Therapist at the Burke Rehabilitation Hospital, White Plains, NY, and then was recruited to join the research team at the Burke Medical Research Institute (BMRI). He has been the Research Clinical Coordinator since 2004. He has been the mainstay of the stroke robotics research program; running the clinical program at BMRI and training therapists from around the country who will be carrying out a VA-funded multicenter study of the effects of robotic training. He is an author of several works, especially a study that shows in patients with stroke that passive motion effectively maintains the integrity of the shoulder joint, but has no effect on upper limb motor function. He is now a certified financial manager.

Neville Hogan was born in Dublin, Ireland. He received the Dip. Eng. (with distinction) from Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin, Ireland, and the M.S., M.E., and Ph.D. degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

He is Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge. He is Director of the Newman Laboratory for Biomechanics and Human Rehabilitation and a founder and director of Interactive Motion Technologies, Inc., a company offering innovative robotic tools to study and treat neuro-motor impairments. Following industrial experience in engineering design, he joined MIT’s school of Engineering faculty in 1979 and has served as Head and Associate Head of the MIT Mechanical Engineering Department’s System Dynamics and Control Division.

Dr. Hogan has been awarded Honorary Doctorates from the Delft University of Technology and the Dublin Institute of Technology and the Silver Medal of the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland.

Footnotes

Reprinted from IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering.

This material is posted here with permission of the IEEE. Such permission of the IEEE does not in any way imply IEEE endorsement of any of this web site’s products or services. Internal or personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution must be obtained from the IEEE by writing to pubs-permissions@ieee.org.

By choosing to view this document, you agree to all provisions of the copyright laws protecting it.

In addition to the shoulder-and-elbow robot and wrist robot, we have recently completed a novel hand robot and are presently in planning phase of the whole-arm therapy trial [27].

The Coop Studies and the Research and Development Offices of the Veterans Affairs are presently employing these robots as an integrated unit at a multisite trial (CSP 558). MIT is not part of this multisite study.

The major source of backlash in MIT’s design is the construction of the differential gearset and curved rack. One of the coauthors, D. Williams, reported that specifying tighter tolerances for the differential gear and curved rack used in the commercial counterpart of MIT’s wrist robot improved the stability range significantly to 0–115 Nm/rad and 0–6.5 Nm/rad/s for pronation/supination and 0–160 Nm/rad and 0–1.86 Nm/rad/s for flexion/extension and abduction/adduction.

Sign convention holds that clockwise rotation of the motors is positive.

The spider gear connects the right and left differential end gears.

Target enrollment is 40 patients per group and robots are only used in standalone mode for all four groups.

Our working hypothesis is that a change of three points or higher in the F-M impairment scale leads to significant change also in disability (H. I. Krebs submitted).

Contributor Information

Hermano Igo Krebs, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA, and with the Neurology Department, Weill Medical College, Cornell University, Burke Medical Research Institute, White Plains, NY 10605 USA, and also with the Neurology Department, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA (e-mail: hikrebs@mit.edu)..

Bruce T. Volpe, Neurology Department, Weill Medical College, Cornell University, Burke Medical Research Institute, White Plains, NY 10605 USA and with the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA.

Dustin Williams, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA. He is now with Interactive Motion Technologies, Inc., Cambridge, MA 02138 USA..

James Celestino, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA. He is also with Shelhigh, Inc., Union, NJ 07083 USA..

Steven K. Charles, Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA.

Daniel Lynch, Burke Medical Research Institute, White Plains, NY 10605 USA..

Neville Hogan, Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA..

References

- 1.Heart disease and stroke statistics—2003 update American Heart Association. Dallas, TX: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twitchell TE. The restoration of motor function following hemiplegia in man. Brain. 1951;vol. 74(no 4):443–480. doi: 10.1093/brain/74.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Vive-Larsen J, Stoier M, Olsen TS. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part I: Outcome and Part II: Time course of recovery. The Copenhagen stroke study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995;vol. 76:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakayama H, Jorgensen HS, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of upper extremity function in stroke patients: The Copenhagen stroke study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1994;vol. 75:394–398. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marler JR, Tilley BC, Lu M, Brott TG, Lyden PC, Grotta JC, Broderick JP, Levine SR, Frankel MP, Horowitz SH, Haley EC, Jr, Lewandowski CA, Kwiatkowski TP. Early stroke treatment associated with better outcome: The NINDS rt-PA stroke study. Neurology. 2000;vol. 55:1649–1655. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wade D. Rehabilitation therapy after stroke. Lancet. 1999;vol. 354:176–177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liepert J, Bauder H, Wolfgang HR, Miltner WH, Taub E, Weiller C. Treatment-induced cortical reorganization after stroke in humans. Stroke. 2000;vol. 31:1210–1216. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miltner WH, Bauder H, Sommer M, Dettmers C, Taub E. Effects of constraint-induced movement therapy on patients with chronic motor deficits after stroke: A replication. Stroke. 1999;vol. 30:586–592. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taub E, Miller NE, Novack TA, Cook EW, 3rd, Fleming WC, Nepomuceno CS, Connell JS, Crago JE. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1993;vol. 74:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasoli SE, Krebs HI, Ferraro M, Hogan N, Volpe BT. Does shorter rehabilitation limit potential recovery poststroke? Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2004;vol. 18(no 2):88–94. doi: 10.1177/0888439004267434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dromerick AW, Edwards DF, Hahn M. Does the application of constraint-induced movement therapy during acute rehabilitation reduce arm impairment after ischemic stroke? Stroke. 2000;vol. 31:2984–2988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Lee JH. Constraint-induced therapy for stroke: More of the same or something completely different? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2001;vol. 14:741–744. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Lee JH, Wagenaar RC, Lankhorst GJ, Vogelaar TW, Deville WL, Bouter LM. Forced use of the upper extremity in chronic stroke patients: Results from a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Stroke. 1999;vol. 30:2369–2375. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trombly CA. Conceptual foundations for practice. In: Trombly CA, Radomski MV, editors. Occupational Therapy for Physical Dysfunction. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr J, Shepherd R. Neurological Rehabilitation: Optimizing Motor Performance. Oxford, U.K.: Butterworth Heinemann; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr JH, Shepherd RB. A Motor Relearning Programme for Stroke. 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Aspen Systems; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wade D. Rehabilitation therapy after stroke. Lancet. 1999;vol. 354:176–177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krebs HI, Hogan N, Aisen ML, Volpe BT. Robot aided neuro-rehabilitation. IEEE Trans. Rehabil. Eng. 1998 Mar.vol. 6(no 1):75–87. doi: 10.1109/86.662623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aisen ML, Krebs HI, McDowell F, Hogan N, Volpe BT. The effect of robot assisted therapy & rehabilitative training on motor recovery following a stroke. Arch. Neurol. 1997;vol. 54:443–446. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160075019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Aisen ML, Hogan N. Increasing productivity and quality of care: Robot-aided neurorehabilitation. VA J. Rehabil. Res. Develop. 2000;vol. 37(no 6):639–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volpe BT, Krebs HI, Hogan N, Edelstein L, Diels CM, Aisen ML. Robot training enhanced motor outcome in patients with stroke maintained over 3 years. Neurology. 1999;vol. 53:1874–1876. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volpe BT, Krebs HI, Hogan N, Edelstein L, Diels CM, Aisen ML. A novel approach to stroke rehabilitation: Robot aided sensorymotor stimulation. Neurology. 2000;vol. 54:1938–1944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.10.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpe BT, Krebs HI, Hogan N. Is robot-aided sensorimotor training in stroke rehabilitation a realistic option? Current Opinion Neurol. 2001;vol. 14(no 6):745–752. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferraro M, Palazzolo JJ, Krol J, Krebs HI, Hogan N, Volpe BT. Robot aided sensorimotor arm training improves outcome in patients with chronic stroke. Neurology. 2003;vol. 61:1604–1607. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095963.00970.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fasoli S, Krebs HI, Stein J, Frontera WR, Hughes R, Hogan N. Robotic therapy for chronic motor impairments after stroke: Follow-up results. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;vol. 85:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein J, Krebs HI, Frontera WR, Fasoli SE, Hughes R, Hogan N. Comparison of two techniques of robot-aided upper limb exercise training after stroke. Amer. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;vol. 83(no 9):720–728. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000137313.14480.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masia L, Krebs HI, Cappa P, Hogan N. Design and characterization of hand module for whole-arm rehabilitation following stroke. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics. 2007 Aug.vol. 12(no 4):399–407. doi: 10.1109/TMECH.2007.901928. “,” presented at the 2006 IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatronics, Pisa, Italy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hesse S, Schulte-Tigges G, Konrad M, Bardeleben A, Werner C. Robot-assisted arm trainer for the passive and active practice of bilateral forearm and wrist movements in hemiparetic subjects. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003;vol. 84(no 6):915–920. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(02)04954-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.OMalley MK, Ro T, Levin HS. Assessing and inducing neuro-plasticty with transcranial magnetic stimulation and robotics for motor function. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006;vol. 87(no 12):S59–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.332. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Motor Control: Theory and Practical Applications. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luft AR, McCombe-Waller S, Whitall J, Forrester LW, Macko R, Sorkin JD, Schulz JB, Goldberg AP, Hanley DF. Repetitive bilateral arm training and motor cortex activation in chronic stroke a randomized controlled trial. J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 2004;vol. 292(no 15):1853–1861. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams D. M.S. thesis. Cambridge: Dept. Mech. Eng., Massachusetts Inst. Technol.; 2001. A robot for wrist rehabilitation. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Celestino J. M.S. thesis. Cambridge: Dept. Mech. Eng., Massachusetts Inst. Technol.; 2003. Characterization and control of a robot for wrist rehabilitation. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DJ, Krebs HI, Hogan N. A robot for wrist rehabilitation. presented at the 2001 23rd Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE EMBS; Istanbul, Turkey: [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celestino J, Krebs HI, Hogan N. A robot for wrist rehabilitation: Characterization and initial results. presented at the 2003 ICORR Conf.; Daejeon, Korea: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krebs HI, Celestino J, Williams DJ, Ferraro M, Volpe BT, Hogan N. A wrist extension to MIT-MANUS. In: Bien Z, Stefanov D, editors. Advances in Human-Friendly Robotic Technologies for Movement Assistance/Movement Restoration for People With Disabilities. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Lenninhan L, Fasoli S, Lynch D, Do-minick L, Hogan N. Notes on rehabilitation robotics and stroke. In: Lofaso F, Roby-Brami A, Ravaud JF, editors. Technological Innovations and Handicap. Paris, France: Frison Roche; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charles SK, Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Lynch D, Hogan N. Wrist rehabilitation following stroke: Initial clinical results. presented at the 2005 ICORR Conf.; Chicago, IL: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanney K. Handbook of Virtual Environments. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krebs HI, Palazzolo JJ, Dipietro L, Ferraro M, Krol J, Ran-nekleiv K, Volpe BT, Hogan N. Rehabilitation robotics: Performance-based progressive robot-assisted therapy. Autonomous Robots. 2003;vol. 15(no 1):7–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brashers-Krug T, Shadmehr R, Bizzi E. Consolidation in human motor memory. Nature. 1996;vol. 382:252–255. doi: 10.1038/382252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker MP, Brakefield T, Seidman J, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Sleep and the time course of motor skill learning. Learning Memory. 2003;vol. 10:275–284. doi: 10.1101/lm.58503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krebs HI, Ferraro M, Buerger SP, Newbery MJ, Makiyama A, Sandmann M, Lynch D, Volpe BT, Hogan N. Rehabilitation robotics: Pilot trial of a spatial extension for MIT-manus. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2004;vol. 1(no 5):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Stein J, Bever C, Dipietro L, Palazzolo JJ, Fasoli SE, Hughes R, Lynch D, Finley M, Ohlhoff J, Frontera WR, Hogan N. Graded robotic protocols differentially alter aspects of motor recovery from chronic stroke. unpublished. [Google Scholar]