Abstract

Aims

To describe issues noted and recommendations made by community pharmacists during reviews of medicines and lifestyle relating to coronary heart disease (CHD), and to identify and quantify missed opportunities for making further recommendations and assess any relationships with demographic characteristics of the pharmacists providing the reviews.

Methods

All issues and recommendations noted by 60 community pharmacists during patient consultations were classified and quantified. Two independent reviewers studied a subsample of cases from every participating pharmacist and identified and classified potential issues from the available data. The findings of the pharmacists and the reviewers were compared. Relevant pharmacist characteristics were obtained from questionnaire data to determine relationships to the proportion of potential issues noted.

Results

A total of 2228 issues and 2337 recommendations were noted by the pharmacists in the 738 patients seen, a median of three per patient (interquartile range 2–4). The majority of the recommendations made (1719; 74%) related to CHD. In the subsample of 169 patients (23% of the total), the reviewers identified 1539 potential issues, of which pharmacists identified an average of 33.8% (95% confidence interval 30.1, 36.4). No relationship was found between the proportion of issues noted and potentially relevant factors such as pharmacists' characteristics and their experience of doing reviews.

Conclusions

The majority of issues and recommendations noted by pharmacists related to CHD, although pharmacists recorded only a minority of the issues identified by reviewers. Variation between pharmacists in the completeness of reviews was not explained by review or other relevant experience.

What is already known about this subject?

There is conflicting evidence concerning the potential benefits of pharmacist-led medication review.

Little work has been published on the completeness of medication reviews provided by community pharmacists.

What this study adds

The 60 community pharmacists taking part in a large randomized controlled trial showed considerable variation in the completeness of the reviews they recorded for intervention patients.

Overall, pharmacists recorded only a minority of the potential issues present in these patients.

The frequency with which pharmacists recorded issues was not related to key characteristics or to the number of reviews completed.

Keywords: community pharmacy services, pharmaceutical care, primary care

Introduction

Community pharmacists in the UK are being encouraged to engage in medicines management activities such as medicines use reviews (MURs) as part of their new contract [1, 2]. Pharmacists wishing to conduct such reviews must undergo accreditation and their premises must also be approved. The type of review conducted by community pharmacists includes a consultation with a patient, supported by data abstracted from pharmacists' patient medication records (PMRs), in the absence of clinical data obtained from medical records. Studies of medicine reviews of this type have failed to demonstrate benefits such as a reduction in hospital admissions, reduced costs or improved quality of life [3–5]. However, several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that clinical medication review by highly trained pharmacists who have full access to all relevant information both identifies and resolves the number of problems relating to medicines more frequently than routine care [6] and may contribute to lower prescribing costs [7, 8]. Reasons for the apparent differences in these findings are unknown, but the equivocal nature of most studies has lead to calls for the MUR service to be re-considered [5, 9].

Prior to the instigation of the MUR service, a large randomized controlled trial, approved by a UK Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (reference number MREC/01/0/95) was conducted of a similar service: The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project (CPMMP). The study involved community pharmacists from nine areas of England who provided medicines reviews to patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) as part of a medicines management service. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their inclusion in the study. The reviews provided were of slightly greater depth than the current MUR service descriptor, because data obtained during consultations with patients and data from PMRs were supplemented with an agreed care dataset of clinical information extracted from the patients' medical records by audit clerks [10].

The results of this study have been reported elsewhere [11]. In line with other studies involving community pharmacists and limited data, there were no significant benefits in terms of quality of life, cost of medicines, health service utilization or prescribing appropriateness in line with the National Service Framework (NSF) for CHD [11]. As part of the evaluation of the CPMMP, the training provided to community pharmacists, which was specifically designed for the project [12], and the reviews they delivered were studied.

This study reports the pharmaceutical care issues identified and recommendations documented by pharmacists following consultations with intervention patients. Pharmaceutical care issues are defined as ‘elements of pharmaceutical need which can be addressed by pharmacists’[13] and the pharmacists providing reviews were required to record all pharmaceutical care issues they had identified as a result of their data gathering and also any recommendations for intervention or advice provided. The content of the reviews provided was studied further to assess their ‘quality’. As no published methods are available for this purpose, a method was devised which used the data provided to the pharmacists, supplemented with data obtained from the patient consultation and their own PMRs. A subsample of patients was used for this purpose.

The objectives were:

to describe the issues noted and recommendations made by community pharmacists as a result of their review of medicines and lifestyle in patients with CHD

to identify any missed opportunities for making further recommendations

to assess whether the frequency with which opportunities were missed related to differences between pharmacists

to assess whether there was any improvement over time in the proportion of issues identified by pharmacists.

Methods

Original documentation completed by pharmacists during the reviews with all patients who received the intervention was studied. The documentation included the data provided by audit clerks on prescribed medicines and basic clinical data plus the data added by pharmacists from their PMRs and their records of the responses patients gave to the questions they posed. These included questions relating to understanding of the need for each medicine, its purpose, their willingness to continue its use, any perceived adverse effects and benefits, and knowledge of monitoring having been carried out. Pharmacists were also required to record all the issues they identified, whether or not action was required, all recommendations to general practitioners (GP)s, advice given to patients and any other actions taken.

The issues, recommendations and actions recorded by pharmacists on the documentation were classified using a modified version of a previously published method [14, 15], with an additional category for lifestyle issues. The drugs involved in the issues and recommendations were categorized using the British National Formulary (BNF) [16]. A quality assurance check was performed on the categorization by a clinical pharmacist not associated with the study, using a randomly selected 10% sample of cases. Issues relevant to improving health outcomes in CHD were analysed in more detail.

In-depth evaluation

A subsample of clinical records from every pharmacist was included in the in-depth evaluation to facilitate the objectives relating to the effect of pharmacist characteristics and review experience on performance. The sampling frame chosen was three clinical record forms for each pharmacist: one from a patient seen early in the study, one around the mid point and one at the end. Where pharmacists saw only three or fewer patients, all clinical record forms were reviewed. Cases were selected independently by a technical assistant, who had no input into the subsequent evaluation, based on the date of review and the total number of patients seen by the pharmacists.

A practising clinical pharmacist (J.K.) and a practising GP (A.J.A.) independently noted and classified issues identifiable from the same set of clinical information which was provided to the pharmacists, without reference to the issues the pharmacists had noted. A systematic approach was taken which incorporated points in Box 1.

Box 1

Criteria used in identifying potential pharmaceutical care issues from clinical information records

Blood pressure or lipid levels above the limits set by the National Service Framework (NSF) for CHD [17]

Glucose above 6 mmol l−1 whether fasting, random or not specified (for patients with no diagnosis of diabetes mellitus)

Body mass index (BMI) >25

No available monitoring data for blood pressure, lipids, glucose, BMI or data >1 year old (except height)

No available recording of pulse if patient had atrial fibrillation

Any issues regarding the appropriateness of prescribed medication in terms of dose, reason for taking the medication, compliance, side-effects, monitoring and interactions with other drugs or diseases

Lack of appropriate treatment for secondary prevention for CHD (antiplatelet, lipid-lowering, β-blocker, ACE inhibitor)

Lack of effectiveness of existing treatment for angina, hypertension and diabetes

Inequivalent quantities of medication prescribed and discontinued medications still on repeat list

Lifestyle issues present which merit intervention

Medicines where cost savings could reasonably be made without affecting patient care (such as recommended by the Audit Commission report on rational prescribing) [18]

Other issues which could potentially affect compliance

Issues which were decided by the reviewers and project steering group to be outside the remit of study pharmacists were excluded from further analysis. These included: lack of appropriate treatment for secondary prevention for CHD where data were old or missing, certain monitoring requirements considered to be the responsibility of the GP, potential drug–drug interactions where an adverse event was considered unlikely, and noncardiovascular drugs for which no indication was found. Where the reviewers could not confirm whether issues were present because of the limitations of the individual data they had about each patient, these were not counted as missed issues. Following independent review of the forms, the two reviewers discussed all remaining cases where different issues had been identified.

All issues identified by study pharmacists, but not by the reviewers, were assessed for appropriateness, taking account of all data available, using the categories:

‘appropriate’ (definition – in line with the NSF for CHD or other UK guidance, including the BNF)

‘inappropriate’ (definition – has the potential to be detrimental to the patient)

‘not inappropriate’ (definition – not necessarily the ideal option, but not inappropriate).

Only those issues considered to be appropriate were included in further analysis. After reaching consensus by discussion on which issues should be included, the frequencies of each type of issue noted by reviewers (potential issues) and those noted by study pharmacists (noted issues) were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

To ensure that the sample of cases for in-depth analysis was representative of the total number of cases seen, sampled cases were compared with nonsampled cases in terms of sex, age, number of prescribed medicines, number of issues identified and number of recommendations made by study pharmacists, using χ2 and Mann–Whitney U-tests.

Using all the cases included in the in-depth evaluation, the average proportion of the agreed potential issues which each individual pharmacist identified was calculated. These average values, illustrating performance, were compared with the demographic characteristics of the pharmacists obtained from self-completed questionnaires, using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

For the pharmacists for whom clinical records from three different time points were available, the mean percentage of issues identified at each time point was calculated. Repeated measures anova was used to assess whether performance improved over time.

Results

Description of issues, recommendations and actions

Sixty different pharmacists saw a total of 738 intervention patients. The number seen per pharmacist ranged from one (four pharmacists) to 62 [median nine, interquartile range (IQR) 4–16]. At least one issue was identified in 653 (88.5%) patients. A total of 2228 issues were noted and 2337 recommendations were made by study pharmacists, both with a median of three per patient (IQR 2–4). The number of issues and recommendations recorded showed considerable variation between the 60 pharmacists. Table 1 shows the different types of issues documented. The most frequently noted type of issue was the need for monitoring (27.4%) and the largest number of recommendations was related to lipid-lowering therapy, either directly or via a request for liver function tests. The following were also frequently identified: an indication for treatment to be added, such as aspirin or a statin (15.3%) and potentially ineffective therapy (10.1%) for hypertension, lipid management and angina. Lifestyle issues for CHD comprised 10.3% of all issues noted. There were relatively few issues concerning prescribed drugs with no indication (1.8%), items no longer required (2.5%), or cost (1.4%).

Table 1.

Frequency and type of issues documented (n = 2228)

| Type of issue | Total issues % of total (n) | Issues relating to CHD, hypertension and diabetes, % of issue type (n) | Other issues % of issue type (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring issues | 27.4 (612) | 93 (569) | 7 (43) |

| Indication but no treatment | 15.3 (341) | 70 (239) | 30 (102) |

| Lifestyle issues for CHD | 10.3 (231) | 100 (231) | 0 |

| Potentially ineffective therapy | 10.1 (226) | 75 (169) | 25 (57) |

| Inappropriate administration | 7.8 (174) | 83 (145) | 17 (29) |

| Adverse drug reaction | 7.0 (156) | 80 (124) | 20 (32) |

| Need for education | 4.0 (89) | 43 (38) | 57 (51) |

| Compliance and concordance issues | 3.9 (88) | 63 (55) | 37 (33) |

| Repeat medicine no longer required | 2.5 (56) | 18 (10) | 82 (46) |

| Non-equivalent quantities | 2.4 (54) | 7 (4) | 93 (50) |

| Inaccurate repeat medicine record | 1.9 (43) | 70 (30) | 30 (13) |

| Drug with no indication | 1.8 (41) | 49 (20) | 51 (21) |

| Cost issue | 1.4 (32) | 81 (26) | 19 (6) |

| Out of date medicines | 0.9 (21) | 90 (19) | 10 (2) |

| Duration of therapy | 0.9 (20) | 5 (1) | 95 (19) |

| Drug–drug interaction | 0.8 (19) | 79 (15) | 21 (4) |

| Potential drug–disease interaction | 0.6 (14) | 100 (14) | 0 |

| Duplication of therapy | 0.5 (11) | 73 (8) | 27 (3) |

| Total | 100 (2228) | 77.1 (1717) | 22.9 (511) |

Table 2 shows the different types of recommendations documented by the pharmacists. Overall 74.8% of recommendations were directed towards the GP or another healthcare professional and 25.2% to the patient. As would be expected from the issues noted, recommendations for monitoring were frequent (31.7%), as was lifestyle advice (10.3%). Adding a drug (11.7%) and changing a dose (8.6%) were common recommendations, but there were few recommendations to stop a drug (2.0%).

Table 2.

Frequency and type of recommendations made (n = 2337)

| Type of recommendation | Total recommendations, % of total (n) | Recommendations relating to CHD, hypertension and diabetes, % of recommendation type (n) | Other recommendations, % of recommendation type (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendations to healthcare professionals 74.8% (1748) | |||

| Carry out monitoring | 31.7 (743) | 94 (700) | 6 (43) |

| Add drug | 11.7 (275) | 84 (232) | 16 (43) |

| Change dose of drug | 8.6 (202) | 83 (167) | 17 (35) |

| Other advice | 8.1 (190) | 67 (128) | 33 (62) |

| Change computer record | 6.9 (162) | 31 (50) | 69 (112) |

| Change drug | 5.5 (128) | 72 (92) | 28 (36) |

| Stop drug | 2.0 (48) | 46 (22) | 54 (26) |

| Recommendations to patients 25.2% (589) | |||

| Lifestyle advice | 10.3 (242) | 100 (242) | 0 |

| Other advice about medicines | 4.9 (114) | 49 (56) | 51 (58) |

| Change time of administration | 4.0 (94) | 81 (76) | 19 (18) |

| Consult GP | 2.8 (65) | 48 (31) | 52 (34) |

| Other advice | 1.5 (36) | 8 (3) | 92 (33) |

| Out of date medicines | 0.8 (19) | 90 (17) | 10 (2) |

| Provide compliance aid | 0.2 (5) | 0 | 100 (5) |

| Change dose of medicine | 0.3 (6) | 17 (1) | 83 (5) |

| Change method of administration | 0.2 (4) | 75 (3) | 25 (1) |

| Stop OTC medicine | 0.2 (4) | 0 | 100 (4) |

| Total | 100 (2337) | 77.9 (1820) | 22.1 (517) |

The majority of the issues noted (1717, 77.1%) and the recommendations made (1820, 77.9%) related to cardiovascular conditions, diabetes and lifestyle relevant to these conditions.

In-depth evaluation of issues

The in-depth evaluation included a total of 169 cases seen by the 60 study pharmacists. There were no differences between the sampled and nonsampled cases in any of the characteristics studied (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients sampled for in-depth analysis compared with those not sampled

| Characteristic | In-depth sample (n = 169) | Remaining patients (n = 569) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (percentage) of female patients | 120 (71%) | 393 (69%) | 0.277* |

| Median (interquartile range) age, years | 69 (62–74.5) | 69 (63–76) | 0.156** |

| Median (interquartile range) number of prescribed medicines | 7 (5–10) | 7 (5–10) | 0.817** |

| Median (interquartile range) number of problems identified by pharmacists | 3 (2–4) | 3 (1–4) | 0.183** |

| Median (interquartile range) number of issues identified by pharmacists | 3 (2–5) | 3 (1–4) | 0.305** |

χ2test.

Mann–Whitney U-test.

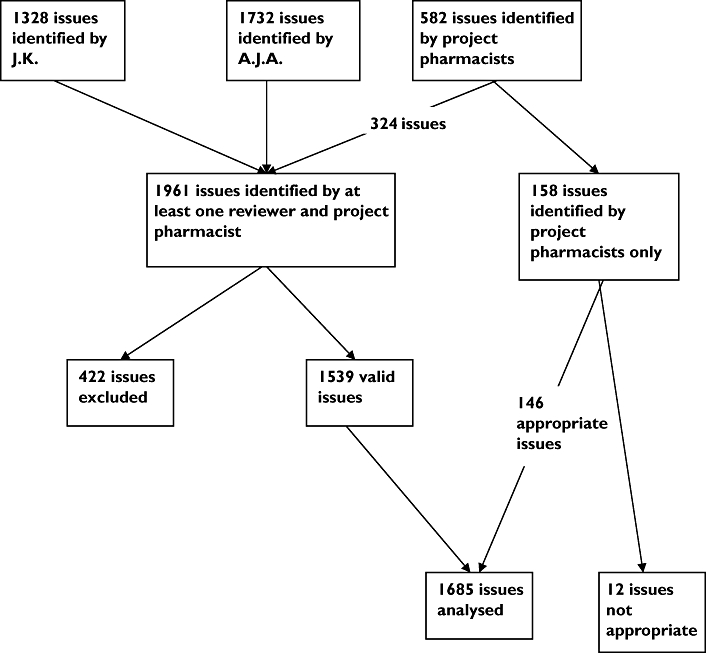

The clinical pharmacist identified 1328 issues and the GP identified 1732, giving a total of 1803 different issues. Study pharmacists recorded a total of 582 issues, 324 of which were identified by one or both of the reviewers. The remaining 158 issues noted by study pharmacists included many which could not be confirmed by reviewers from the documented information. The total number of issues identified by either one of the reviewers or by a study pharmacist was 1961 (Figure 1). Of the 1961 issues, reviewers initially agreed on the presence of 1079 (55.3%) and on the classification of 910 (84.3%) of these. Issues identified by reviewers but considered to be outside the remit of study pharmacists as outlined in Methods were excluded at this point, leaving 1539 issues. Both reviewers also assessed the 158 issues identified by the study pharmacists and agreed that 146 (92.4%) were appropriate (Figure 1). This resulted in a total of 1685 realistic potential issues identifiable from the clinical information available to the study pharmacists [median 10.0 (IQR 7–12) per patient].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram to illustrate pharmaceutical care issues identified and included in the in-depth analysis

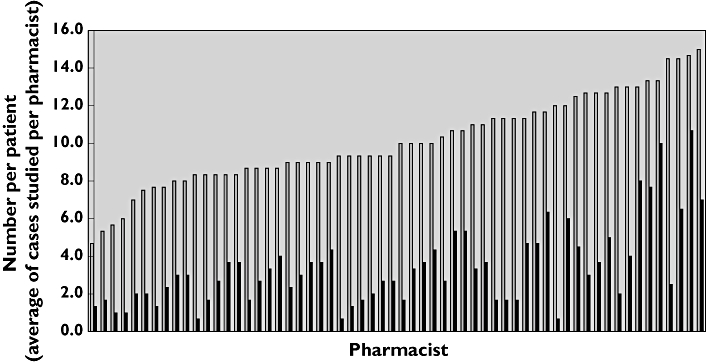

Study pharmacists identified 570 of the 1685 issues, with a mean frequency of 33.3% (95% confidence interval 30.1, 36.4). The median number of issues identified was 3.0 (IQR 2–4) per patient, the same as for the full cohort of intervention patients. Of the 60 pharmacists, 19 (32%) identified ≤25% of the potential issues, 32 (53%) identified 25–49% of issues and only nine (15%) identified ≥50% (Figure 2). In total, 80% of all issues identified by both study pharmacists and reviewers were related to cardiovascular disease, diabetes or lifestyle issues for CHD, indicating that a high proportion of those not documented related to the main aim of the study.

Figure 2.

Performance of individual pharmacists shown as average number of issues per patient identified compared with average number per patient identified by reviewers. Potential issues/patient identified by reviewers, ( ); issues/patient noted by study pharmacists, (

); issues/patient noted by study pharmacists, ( )

)

The extent to which pharmacists documented potential issues of different types varied (Table 4). Many instances where additional medication related to CHD or hypertension could have been recommended (n = 77) or dose changes suggested to improve efficacy (n = 84) were not recorded by the pharmacists. The reviewers identified a total of 141 lifestyle issues that had not been noted by pharmacists. Although the need for monitoring was noted frequently by pharmacists (168 times in the 169 cases), there were a further 385 parameters requiring monitoring which they did not record. These were identified by the reviewers in cases where monitoring data were missing, were old or were required to assess drug-related toxicity.

Table 4.

Frequency of issues noted and not noted by study pharmacists in 169 cases

| Number of issues noted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue type | By study pharmacists | Additionally by reviewers | Total | Percent of total noted by study pharmacists |

| Monitoring | 168 | 385 | 553 | 30 |

| Lifestyle | 77 | 141 | 218 | 35 |

| Potentially ineffective therapy | 67 | 90 | 137 | 49 |

| Indication for therapy | 66 | 83 | 149 | 44 |

| Inappropriate use of medicine | 41 | 51 | 92 | 45 |

| Potential/suspected ADR | 37 | 62 | 99 | 37 |

| Potential/actual compliance | 24 | 45 | 69 | 35 |

| Need for education | 25 | 31 | 56 | 45 |

| Repeat medicine no longer needed | 12 | 34 | 46 | 26 |

| Repeat record not accurate | 10 | 17 | 27 | 37 |

| Quantities not aligned | 9 | 55 | 64 | 14 |

| No indication for medicine | 7 | 8 | 15 | 47 |

| Drug–disease interaction | 8 | 31 | 39 | 21 |

| Cost | 6 | 52 | 58 | 10 |

| Excess duration of treatment | 5 | 10 | 15 | 33 |

| Drug–drug interaction | 3 | 16 | 19 | 16 |

| Out of date medicines | 3 | 1 | 4 | 75 |

| Duplication of therapeutic group | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 570 | 1115 | 1685 | 34 |

Issues relating to prescribing costs were noted infrequently (n = 6), although a further 52 drugs prescribed could have been changed to less expensive alternatives, providing cost savings with no clinical detriment to the patient. These included enteric-coated aspirin (n = 7), modified release isosorbide mononitrate (n = 26), glyceryl trinitrate patches (n = 4) and expensive selective or modified release nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (n = 5). There were also very few cases (n = 9) where pharmacists noted that the quantities of medicines were not aligned or items were no longer required (n = 12), although this was apparent from the data in 89 more cases (Table 4).

Quality of recommendations

The pharmacists made a total of 533 recommendations in the 169 cases. Of these, 504 (94.6%) were classified as ‘appropriate’, 21 (3.9%) ‘inappropriate’ and eight (1.5%) ‘not inappropriate, but not necessarily ideal’. Just over half the recommendations classed as appropriate were related to the NSF for CHD (275, 51.6%), the remaining 229 being in line with other national guidance or otherwise considered appropriate. Those classified as inappropriate are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Details of recommendations considered inappropriate

| Type of recommendation | Frequency | Reason inappropriate |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring required | 8 | Not required |

| Reduce antihypertensive therapy | 1 | Lowering blood pressure of benefit |

| Stop β-blocker | 1 | Risk of angina |

| Reduce statin dose | 3 | Lowering cholesterol of benefit |

| Change dose of diuretic | 1 | Inadequate information to make this recommendation |

| Change times of isosorbide mononitrate | 1 | Timing appropriate |

| Change drug | 2 | Potential to reduce efficacy or cause further problems |

| Start new drug (nitrate) | 1 | Not required |

| Start new drug (Cialis) | 1 | Not highlighted as requiring caution in CHD |

| Start Gastrocote for dyspepsia | 1 | Patient on high-dose aspirin, dose change required |

| Consider enteric coated aspirin to minimize GI side-effects | 1 | No evidence of reduced gastrointestinal side-effects with enteric coated formulation |

| Total | 21 |

Data were available for most study pharmacists on the number of years qualified and whether or not they had a postgraduate qualification or worked in a medical practice (Table 6). None of these variables explained the differences between the pharmacists in terms of percentage of issues not documented. Of the nine pharmacists who stated they worked in a medical practice, two (12%) identified <25% of potential issues, four (13%) between 25 and 49% and only three (33%) ≥50%. Twelve pharmacists stated they had a clinical diploma/MSc, of whom three (18%) identified <25% of potential issues, seven (24%) between 25 and 49% and two (22%) >50%. Ten pharmacists had qualified within 5 years of starting the project. Of these, two (12%) identified <25% of issues, five (17%) between 25 and 49% and three (33%) identified ≥50%.

Table 6.

Comparison of pharmacist characteristics to proportion of potential issues identified

| Characteristic | Number of pharmacists | Median proportion of issues noted (interquartile range) | P-value (Mann–Whitney U-test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualified ≤5 years | 10 | 38 (26.35–53.75) | 0.285 (172) |

| Qualified >5 years | 44 | 31 (20–43.75) | |

| Postgraduate qualification | 12 | 30 (22–46) | 0.857 (237.5) |

| No postgraduate qualification | 41 | 34 (20–44) | |

| Work in medical practice | 9 | 43 (23.5–54) | 0.237 (158.5) |

| Do not work in medical practice | 47 | 33 (20–43) |

For 41 pharmacists, clinical records forms were available from three time points, thus allowing assessment of performance over time. The mean (SD) percentages of potential issues identified at the first, second and third time points were 33% (17), 36% (24) and 32% (23), respectively. Repeated measures anova confirmed no change in performance over time (F: 0.54; P = 0.59).

Discussion

Main findings

Community pharmacists participating in the CPMMP identified a wide range of issues and made recommendations to GPs. The four most frequent types of issue identified related to the need for monitoring, additional therapy or alterations to therapy or lifestyle advice. A median of three issues and recommendations were made per patient, with 75% of all recommendations being directed to a health professional and 25% towards the patient. The in-depth evaluation undertaken showed that where recommendations were made, they were almost all appropriate, but that pharmacists on average documented only a third of potential issues, suggesting that many more recommendations relevant to CHD could have been made. Underrecording of issues relating to lifestyle, potentially ineffective therapy and indication for additional therapy could have affected the primary outcome of the study. Other areas where recommendations were identified and recorded very infrequently by study pharmacists were quantity, cost and interactions.

There was a wide variation in the number of issues identified between pharmacists, but this variation could not be related to any factor considered likely to have an influence.

Study strengths and limitations

The classification systems used have been developed for other similar studies of medication review. The system used to classify issues was found to accommodate all those identified in the study and both a quality check and comparison of classifications by two independent reviewers from different professional backgrounds illustrated its relevance to the issues identified in the study. The sampling strategy used for the in-depth evaluation was designed to ensure that all pharmacists were represented and to take account of the possible development of pharmacists' skills with increasing numbers of patients seen. Due to the large variation in the numbers of patients seen by each pharmacist, this meant that the proportion sampled varied between pharmacists. Overall, a 23% sample was reviewed, which did not differ from the remainder of the patient cohort in terms of the age, sex and number of medicines or in the number of issues and recommendations documented by the study pharmacists. The reviewers conducting the in-depth evaluation were practising professionals (a GP and a clinical pharmacist), with complementary skills which reflected the two key professional stakeholder groups involved in the CPMMP. It is acknowledged, however, that the use of only two reviewers increases the likelihood of agreement being reached and that the reviewers used may not have been representative of other GPs and clinical pharmacists and might have identified more issues than their peers. Criteria for what issues should be analysed were agreed prior to independent evaluation to minimize subjectivity and ensure uniformity of approach, but did not allow for professional judgement on the part of the study pharmacists.

The study is limited by its reliance on the completeness of documentation and the fact that study pharmacists conducted interviews with patients, whereas reviewers were limited to the resultant documentation. Studies showing benefits from medication review have involved few pharmacists, who were highly trained and motivated to complete documentation fully [6–8]. Limited training was provided to pharmacists participating in this large study but, as 60 different pharmacists were involved and no formal assessment of their competency to conduct reviews was made, it is possible that some failed to complete all aspects of the documentation. Pharmacists were instructed to record patients' responses to questioning on a form specifically designed for this purpose, which acted as their clinical record until the end of the study. Thus, the data available to reviewers, in particular all the clinical data obtained from medical records, were in most cases likely to be as complete as those available to pharmacists. Despite this, some additional unrecorded data may have been available to the community pharmacists from patient interviews, which could have resulted in some issues being identified by pharmacists and not reviewers. Furthermore, pharmacists may have addressed additional issues during their consultation which they failed to document. Other work has shown that issues can be identified at any stage of a medication review process: the prescription, the medical record or the patient interview, and then resolved without any further intervention once additional data are obtained [14]. If this was the case here and these issues were not recorded, the study would underestimate the overall number of issues identified. It is recognized that pharmacists may also have prioritized issues to be addressed following the initial consultation, leaving less important issues to be considered at follow-up appointments, although only 28 patients reported receiving follow-up interviews [11].

Little research has been published on the completeness of medication reviews. Methods described in the literature are applied to each medicine prescribed for the patient [19–21]. These are used to assess the appropriateness of medicines to assign each medication a ‘quality use of medicines outcome’ before and after reviews. Whether these methods are able to identify missed issues such as an indication for an additional drug or the inappropriate use of drugs as reported by patients is questionable. None of the issues in the present study arising from information noted by pharmacists during interview which related to ability to comply, understanding and lifestyle would be detected by such methods. As it is not feasible to re-interview patients, the methodology used would appear to be a reasonable mechanism of evaluating the reviews.

Comparison with published work

In comparison with other studies, the pharmacists participating in the CPMMP documented similar or lower rates of recommendations. Two studies in nursing home residents found 1.65 and 2.75 recommendations per patient [22, 23], one involving community pharmacists visiting patients at home found 2.58 per patient [4], whereas reviews conducted by clinical pharmacists in general practices found 2.8 per patient [8]. In one study using the same system of classifying issues, the number of issues identified was higher at 7.0 per patient [6], which was nearer to that found in the in-depth evaluation in the present study. Several of these studies have suggested that the pharmacists' intervention may reduce drug costs [7, 8, 23]. This was not found in the present study, although the in-depth evaluation suggests that there were opportunities to do so. This current evaluation may also provide insight into why the primary outcomes of the trial were not achieved.

The difficulties in evaluating the completeness of reviews may be the reason for the paucity of research on this subject. Only one recent evaluation has been identified of reviews carried out by community pharmacists in a domiciliary setting, which suggests that they also failed to identify a large range of clinical problems [24]. However, another large UK study involving 22 community pharmacists has noted differences between pharmacists in their documentation of some issues [25]. This study also found there were no differences between pharmacists with a higher degree, years qualified or other relevant characteristics in terms of their impact on the main outcome (in this case hospital admissions), which is in agreement with our findings [25].

This study suggests problems with the completeness of medication reviews by community pharmacists and lack of uniformity between pharmacists, which may have been affected by the limited training provided [12], but which also bore no relationship to demographic characteristics. This variation may have contributed to the lack of benefit shown in the CPMMP [11]. These issues may be of relevance to the current situation, whereby community pharmacists throughout the UK increasingly provide MURs under the terms of the new contract [2], which, although focusing on concordance, often also include clinical interventions [26].

Acknowledgments

The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project was funded by the Department of Health for England and Wales, and managed by a collaboration led by the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (including the National Pharmaceutical Association, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, the Company Chemist Association, and the Co-operative Pharmacy Technical Panel). We thank the pharmacists and patients who were involved in this study and Carol Coupland for checking the repeated measures anova.

References

- 1.Bellingham C. How to offer a medicines use review. Pharm J. 2004;273:602. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. The Pharmaceutical Services (Advanced and Enhanced Services) (England) Amendment Directions 2006. [10 October 2006]. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/10/75/97/04107597.pdf.

- 3.Nazareth I, Burton A, Shulman S, Haines A, Timberall H. A pharmacy discharge plan for hospitalized elderly patients – a randomized, controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2001;30:33–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland R, Lenaghan Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A, Christou M, Evans D, Hand C. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:293–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38338.674583.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pacini M, Smith RD, Wilson ECF, Holland R. Home-based medication review in older people: is it cost-effective? Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:171–80. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D, Duffus PRS. Pharmacist-led medication review in patients over 65: randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30:205–11. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zermansky AG, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Vail A, Lowe C. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients on repeat prescriptions in general practice: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;323:1340–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7325.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackie CA, Lawson DH, Campell A, MacLaren A, Waigh R. A randomized controlled trial of medication review in patients receiving polypharmacy in general practice. Pharm J. 1999;263(Suppl.):R7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland R, Smith R, Harvey I. Where now for pharmacist led medication review? J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60:92–3. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.035188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Briefing note for community pharmacists. Aylesbury: PSNC; 2001. The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team. The MEDMAN study: a randomised controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients with coronary heart disease. Fam Pract. 2007;24:189–200. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaffray M, Krska J, Bond CM, Lee A. on behalf of The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team. The MEDMAN project: Evaluation of the medicines management training for community pharmacists. Pharmacy Education 2008. in press.

- 13.Scottish Office Department of Health Clinical Resource and Audit Group. Clinical Pharmacy Practice in Primary Care. Edinburgh: Scottish Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krska J, Jamieson D, Arris A, McGuire A, Abbott S, Hansford D, Cromarty J. A classification system for issues identified in pharmaceutical care practice. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D. Providing pharmaceutical care using a systematic approach. Pharm J. 2000;265:656–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary. London: BMJ and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health. National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease. [10 October 2006]. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/05/75/26/04057526.pdf.

- 18.Audit Commission. A Prescription for Improvement: Toward More Rational Prescribing in General Practice. London: HMSO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, Cohen HJ, Feussner JR. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oborne CA, Batty GM, Maskrey V, Swift CG, Jackson SH. Development of prescribing indicators for elderly medical inpatients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:91–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1997.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorenson L, Grobler MP, Roberts MS. Development of a quality of medicines coding system to rate clinical pharmacists' medication review recommendations. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:212–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1025860615268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furniss L, Burns A, Craig SKL, Scobie S, Cooke J. Effects of a pharmacist's medication review in nursing homes: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiat. 2000;176:563–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Easthaugh J, Bowie P. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist for elderly people living in care homes: randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2006;35:586–91. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foulsham RM, Goodyer LI. The Development and Delivery of Pharmaceutical Domiciliary Services to Housebound Patients. Health Service Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference. 2005. [30 June 2007]. Available at http://www.hsrpp.org.uk/abstracts/2005_35.shtml.

- 25.Holland R, Lenaghan E, Smith R, Lipp A, Christou M, Evans D, Harvey I. Delivering a home-based medication review, process measures from the HOMER randomised controlled trial. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14:71–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elvey R, Bradley F, Ashcroft DM, Noyce P. Medicines use reviews under the new community pharmacy contract. Health Service Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference proceedings 2007. Int J Pharm Pract. 2007;15(Suppl 1):A3. [Google Scholar]