Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether providing active outreach and assistance to crime victims as part of comprehensive psychosocial services reduced disparities in access to state compensation funds.

Methods. We analyzed data from a randomized trial of injured crime victims (N = 541) and compared outcomes from comprehensive psychosocial services with usual community care. We examined the impact of outreach and assistance on disparities in applying for victim compensation by testing for interactions between victim characteristics and treatment condition in logistic regression analyses.

Results. Victims receiving comprehensive services were much more likely to apply for victim compensation than were victims receiving usual care. Comprehensive services decreased disparities associated with younger age, lower levels of education, and homelessness.

Conclusions. State-level victim compensation funds are available to help individuals recover physically, psychologically, and financially from crime victimization. However, few crime victims apply for victim compensation, and there are particularly low application rates among young, male, ethnic minority, and physical assault victims. Active outreach and assistance can address disparities in access to victim compensation funds for disadvantaged populations and should be offered more widely to victims of violent crime.

Violent crime victimization is associated with high individual and societal costs.1–4 It is estimated that violent crime victimization results in tangible costs to victims of over $17 billion annually because of medical and mental health care expenses, lost productivity, and property damage and in intangible costs of approximately $330 billion because of reduced quality of life, pain, and suffering.2 Victims pay approximately $44 billion out-of-pocket annually in tangible costs, and employers, insurers, and government programs pay the remaining costs directly through reimbursement or indirectly through lost revenues.2 Although financial stability and reimbursement for incurred costs or losses do not eliminate all adverse consequences of victimization, they do mitigate problems caused by a lack of material resources and financial strain, which can impair psychological recovery from criminal victimization and prevent a return to previctimization functioning.5 In fact, this financial peri-trauma tends to be a stronger predictor of the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than are features of the victimization itself.6

To help crime victims recover physically, psychologically, and financially from violent victimization, federal and state governments have developed special victim compensation programs to cover the costs of medical and mental health treatment, lost wages, and other expenses. Since passage of the federal Victims of Crime Act in 1984,7 the legislation that established the Office for Victims of Crime and the Crime Victims Fund, the federal government has provided nearly $5 billion to state victim compensation and assistance programs. Despite the availability of funds, there is considerable evidence that the vast majority of victims of violent crime do not access the victim compensation system; the number of applications represents fewer than 5% of total victimizations.8 Although not all victims are eligible for financial compensation, the number of applications received clearly shows drastic underutilization of the victim compensation system. A 1999 survey of 52 compensation administrators in all 50 US states, the District of Columbia, and US territories indicated that 35 of 52 state programs had, on average, annual surpluses of $1.8 million in unspent carryover funds.9 Most administrators (81%) believed the number of claims they received did not represent the number of eligible victims; they attributed this largely to victims’ lack of knowledge regarding government compensation programs.

Other evaluations similarly identify lack of awareness of reimbursement programs and lack of assistance with the application process as significant barriers to reimbursement. In a survey of crime victims identified through law enforcement offices in Maryland,10 less than one third of respondents had heard of victim compensation before being surveyed. However, even among those aware they could apply for compensation, 70% did not file a claim. In a survey of Maryland compensation claimants,10 a majority said they either received no assistance with their application or received assistance only from family and friends rather than from victim advocates, compensation board staff, or other professionals knowledgeable about compensation policies and procedures.

Several studies conducted by the Urban Institute indicate that in addition to general underutilization of victim compensation, there may be disparities between the types of victims who do and those who do not access compensation. State- and national-level data9–11 suggest that younger, male, and ethnic minority victims are underrepresented among claimants relative to the overall victim population. Black victims in particular are underrepresented as claimants in all categories of crime. Among victims of all ethnic backgrounds, sexual assault is overrepresented, whereas physical assault is under-represented. Studies are lacking on whether financially disadvantaged victims are under-served by the victim compensation system. However, those who are younger than 35 years or belong to an ethnic minority group tend to have a disadvantaged economic status. Because these 2 groups have been shown to be underrepresented among claimants, individuals of low socioeconomic status (SES) also may be underrepresented. It has been recommended that outreach and educational efforts target these underserved victim groups to increase their access to victim compensation funds.4,9,12,13

We examined access to victim compensation in California, which operates the largest state crime victim program in the country14 and, like other states, disburses compensation to only a small percentage of its crime victims. In 2004, the California Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board (CVCGCB) distributed approximately $58.8 million among 40 342 victims.15 The number of paid claims accounts for only about 20% of the 189 175 violent crimes reported in California during this same time period.16 The State Restitution Fund has consistently maintained a large cash reserve for more than a decade; the surplus in 2007 was $128 million.17 Thus, ample resources exist to provide compensation to a much greater proportion of California’s crime victims.

To examine ways to increase disadvantaged crime victims’ compensation and access to needed victims services, the CVCGCB funded a demonstration project that established the San Francisco General Hospital Trauma Recovery Center (hereafter “Trauma Recovery Center”). The Trauma Recovery Center provides comprehensive services designed to increase access to the victim services system, to victim services benefits, and to mental health care. Findings from the demonstration project showed that active outreach and assistance increased the number of eligible victims applying for reimbursement, thereby increasing the overall proportion receiving approval for claims.18 We examined whether active outreach and assistance also serves to reduce disparities in filing victim compensation applications related to victim characteristics.

METHODS

All study procedures have been described more fully elsewhere.19 Briefly, injured victims of violent crime were randomly assigned to receive Trauma Recovery Services or usual community care. Victims were followed for 12 months.

Sample

Our sample consisted of injured victims of violent crime who presented for emergency medical treatment at San Francisco General Hospital, a level-1 trauma center. Victims were eligible for the study if (1) they were the victim of domestic violence, physical assault (shooting, stabbing, or battery), or criminal vehicular assault; (2) they presented at San Francisco General Hospital for medical treatment related to the victimization; (3) they were 18 years or older; and (4) they were a San Francisco resident. Victims were excluded if (1) they were currently enrolled in mental health treatment or previously enrolled in Trauma Recovery Center services, (2) they were unable to provide informed consent because of brain injury or other cognitive impairment, (3) they lacked English proficiency, or (4) they had acute psychosis or acute suicidality requiring immediate treatment. The Trauma Recovery Center had an existing county contract to offer services to all sexual assault victims in San Francisco County. Because of this, sexual assault victims could not be randomized and were therefore excluded from the study.

Recruitment

Victims were identified by nurses or social workers in the emergency department or in-patient units. Research assistants also made daily visits to the emergency department and inpatient trauma surgery service to ask clinicians if any potentially eligible crime victims had been admitted. Referring clinicians obtained patients’ verbal consent for research contact. All participants provided written informed consent.

Interviews

Within 1 month of the index crime, research staff interviewed participants at the hospital, their residence, or another convenient location. Demographic information was obtained during these interviews. Interviews were completed an average of 6.7 days (SD = 9.0) after the crime. After obtaining informed consent, participants completed 60-minute baseline interviews, for which they were reimbursed $20.

Assignment to Treatment Condition

Victims were randomly assigned to Trauma Recovery Center services or usual care in a 2-to-1 ratio. Randomization took place upon completion of the baseline interview. Victims assigned to Trauma Recovery Center services completed intake appointments in the hospital, in the community, or at the Trauma Recovery Center and were offered case management services and trauma-informed psychotherapy when appropriate. Case management services included assistance obtaining housing, financial entitlements, and health insurance, as well as assistance working with law enforcement officials and social service agencies. Trauma Recovery Center services were generally offered for an initial 4-month period, with the option to extend services for additional 4-month periods if necessary. In usual care, victims chose whether to seek psychosocial services as they normally would.

Assistance Regarding Submitting a Victim Compensation Program Claim

Research staff gave all victims written information about the victim compensation program at the time of recruitment. Hospital staff, the police, or the district attorney’s office also may have independently provided victims with information about the victim compensation program.

Trauma Recovery Center.

Victims assigned to Trauma Recovery Center services were provided information about the victim compensation program and offered assistance with the application process as a part of case management services. Assistance included helping victims file a police report (if no report was generated at the time of the crime), obtain existing police reports and medical records, complete necessary forms, and for denied claims, file an appeal. Additionally, Trauma Recovery Center clinicians submitted applications directly to the victim compensation program office and maintained correspondence with victim compensation program personnel. Trauma Recovery Center clinicians were directed to assist all interested clients with applications, regardless of their chances of qualifying for reimbursement. When no application was filed, clinicians documented the reason for not filing.

Usual care.

Victims assigned to usual care received the initial information about the victim compensation program and San Francisco Victim Witness Assistance Center but no further assistance. The San Francisco Victim Witness Assistance Center provides general assistance and forwards completed applications to the victim compensation program on behalf of victims, but like most local victim’s assistance offices, it does not engage in outreach to victims who may be eligible for compensation.9 No information was available regarding why these victims did not file claims.

Measures

Victim characteristics.

In baseline interviews, participants were asked about age, ethnic background, years of education, monthly income, and housing and employment status. Ethnic background was categorized as White, Black, Latino, and mixed or other. Because average monthly income had a large amount of variance, income was categorized as falling above or below the federal poverty level. The cutoff point was $748, corresponding to the US Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines20 for a single individual for the year 2003; 2003 was the midpoint of study recruitment.

Dichotomous variables were used to represent age (35 years or younger vs older than 35 years), housing status (homeless vs housed), education (less than high school vs high school or beyond), and employment status (employed vs not employed). The age categorization was selected because although individuals older than 35 years are less likely to be victims of violent crime, they are more likely than younger victims to file compensation claims.9 The type of victimization, obtained from hospital records, fell into 1 of 3 categories: domestic violence, vehicular assault (including accidents caused by drunk driving, hit-and-run accidents, and intentional injury with a vehicle), or physical assault (including shooting, stabbing, and assaults without weapons). These victimization categories were chosen to correspond as closely as possible with those used in analyses by the Urban Institute.9,10

Victim compensation program claim status.

The state victim compensation program office provided claims information on all participants, including whether a claim was submitted and whether submitted claims were approved or denied. Claims information for a participant was examined for the 12-month period after study enrollment. Only claims associated with the index crime were examined. The primary outcome variable was whether victims had filed a claim within the 12-month period after victimization.

Analytic plan.

Analyses involved an intent-to-treat approach: all randomized participants were included regardless of whether they used services during the study period. We used hierarchical logistic regression analysis to examine whether active outreach and assistance provided by the Trauma Recovery Center ameliorated disparities in applications for victim compensation. Specifically, we tested for interactions between treatment condition and victim characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, level of education, income, housing status, and type of victimization.

A method of testing for interactions in multiple regression21 was applied to this logistic regression model. Both predictor (victim characteristics) and moderator (treatment condition) variables were entered first to partial out their effects from the cross product or interaction. In the first step, the model included (1) victim characteristics; (2) the type of crime, with physical assault as the reference group; and (3) treatment condition, with Trauma Recovery Center services coded as 1 and usual care coded as 0. Significant main effects for predictors or moderators are not necessary for the testing of interactions.

In the second step, variables representing the interaction between treatment condition and victim characteristics and type of crime were included. All possible interaction terms were tested separately. For the categorical variables of ethnicity and type of victimization, a series of dummy variables was created to compare each category of the variable to all other categories combined. For example, for ethnicity, 3 separate interaction terms were created: treatment condition × White and non-White race/ethnicity, treatment condition × Black and non-Black race/ethnicity, and treatment condition × Latino and non-Latino race/ ethnicity. All interaction terms that were significant when examined individually were included simultaneously in the second step of the final model.

A correlation matrix was used to identify potential independent variable multicollinearity, which would preclude inclusion in the same regression model. No correlation was higher than 0.34, indicating that all variables could be included in the model.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

Of the 696 eligible individuals, research staff successfully located and contacted 543 people (78.0%) 1 month after their initial hospital visit to explain the study. The contact rate was higher for men (81.7%) than for women (70.8%; χ29 = 0.81; df = 1; P = .002) and higher for hospitalized victims (83.7%) than for those seen only in the emergency department (72.7%; χ21 = 2.46; df = 1; P ≤ .001). There were no age or ethnic differences in the proportion of patients successfully contacted. Of the 543 offered enrollment in the study, all but 2 (0.4%) agreed to participate, for a final sample of 541.

As shown in Table 1 ▶, the sample was mostly male, ethnic minority, not employed, uninsured, and had very low incomes. The average age was 37 years, with 45% aged 35 years or younger, and the average level of education was 12 years, with 33% having less than a high school education. More than 40% were homeless. Most were victims of assault, with smaller numbers experiencing domestic violence and vehicular assault. There were no significant differences between treatment conditions of any victim characteristics.

TABLE 1—

Sample Demographic Characteristics of Injured Victims of Violent Crime: Trauma Recovery Center Demonstration Project, San Francisco, California, 2001–2006

| Variable | Total sample | Trauma Recovery Center | Usual Care |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 407 (75.1) | 245 (72.5) | 162 (79.4) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |||

| White | 113 (20.8) | 78 (23.1) | 35 (17.2) |

| Black | 280 (51.7) | 168 (49.9) | 112 (54.9) |

| Latino | 66 (12.2) | 43 (12.8) | 23 (11.3) |

| Mixed/Other | 83 (15.3) | 48 (14.2) | 34 (16.7) |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 37.0 (11.3) | 36.4 (11.5) | 38.1 (10.9) |

| ≤ 35 y, no. (%) | 243, 44.9 | 161, 47.8 | 82, 40.2 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 12.0 (2.3) | 12.0 (2.3) | 12.0 (2.2) |

| Less than high school education, no. (%) | 179 (33.1) | 111 (32.9) | 68 (33.5) |

| Homeless, no. (%) | 222 (41.0) | 135 (39.9) | 87 (42.6) |

| Not working, no. (%) | 343 (63.4) | 224 (66.5) | 119 (58.3) |

| Monthly income, $, mean (SD) | 1147 (2953) | 1283 (3617) | 921 (1191) |

| Income below federal poverty level, no. (%) | 302 (56.4) | 191 (57.2) | 111 (55.2) |

| Uninsured, no. (%) | 354 (65.3) | 221 (66.2) | 133 (65.5) |

| Type of victimization, no. (%) | |||

| Assault | 436 (80.4) | 270 (79.9) | 166 (81.4) |

| Domestic violence | 83 (15.3) | 51 (15.1) | 32 (15.7) |

| Vehicular assault | 23 (4.2) | 17 (5.0) | 6 (2.9) |

Note. There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 treatment groups.

Victim compensation program claims information for the 2 treatment conditions is shown in Table 2 ▶. Despite a higher rate of approval for claims by victims assigned to usual care, the overall higher proportion of victims submitting applications in the Trauma Recovery Center condition resulted in a much higher proportion of Trauma Recovery Center clients receiving compensation. The most common reasons victims assigned to the Trauma Recovery Center did not file claims were that victims did not engage in services or attended 4 or fewer sessions (83%). Other reasons were that victims said they were filing with the local Victim Witness Assistance Center and did not need Trauma Recovery Center assistance (but ultimately did not file an application, 3%), or that victims chose not to submit an application (3%). The reason victims did not file an application was unknown in 10% of cases.

TABLE 2—

Victim Compensation Claim Status of Injured Victims of Violent Crime, by Treatment Condition (Trauma Recovery Center or Usual Care): Trauma Recovery Center Demonstration Project, San Francisco, California, 2001–2006

| Comparison | |||||

| Variable | Total, No. (%) | TRC, No. (%) | Usual Care, No. (%) | X2 | P |

| Filed a claim | 236 (43.5) | 189 (55.9) | 47 (23.0) | 55.9 | ≤.001 |

| Status of filed claim | |||||

| Denied | 45 (19.1) | 41 (21.7) | 4 (8.5) | 4.2 | .04 |

| Approved | 191 (80.9) | 148 (78.3) | 43 (91.5) | . . . | . . . |

| Received compensation vs. no claim/denied claim | 191 (35.2) | 148 (43.8) | 43 (21.1) | 27.7 | ≤.001 |

Note. TRC = Trauma Recovery Center.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

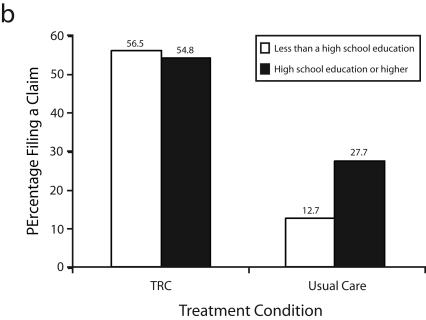

Results from the regression analysis are shown in Table 3 ▶. After partialling out the main effects of victim characteristics and treatment condition, 3 significant interactions were identified: those between treatment condition and age, education, and housing status. To aid in the interpretation of these interactions, general linear models were run with the usual care and Trauma Recovery Center groups separately to compare the proportions of respondents filing claims according to the 2 levels of each binary variable, with all other victim characteristics included as covariates. The interactions are graphed in Figure 1 ▶.

TABLE 3—

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Analyses of Filing a Victim Compensation Claim Showing Interactions Between Treatment Condition and Victim Characteristics: Trauma Recovery Center Demonstration Project, San Francisco, California, 2001–2005

| OR (95% CI) | |

| Step 1: Main effects | |

| Male gender | 1.00 (0.60, 1.67) |

| Ethnicity (referent = White) | |

| Black | 0.86 (0.52, 1.40) |

| Latino | 1.23 (0.62, 2.46) |

| Mixed/Other | 0.87 (0.46, 1.65) |

| Aged 35 y or younger | 0.72* (0.49, 1.06) |

| Less than high school education | 0.73 (0.48, 1.10) |

| Homeless | 0.44*** (0.29, 0.68) |

| Not working | 0.68 (0.44, 1.05) |

| Income below federal poverty level | 1.19 (0.79, 1.78) |

| Uninsured | 0.96 (0.62, 1.47) |

| Type of crime (referent = physical assault) | |

| Domestic violence | 0.60 (0.52, 1.40) |

| Vehicular assault | 2.09 (0.62, 2.46) |

| Treatment condition (TRC = 1, UC = 0) | 4.73*** (3.10, 7.22) |

| Model χ2 | 90.62*** |

| Step 2: Interactions | |

| Treatment condition × age | 3.32* (1.25, 8.81) |

| Treatment condition × education | 0.24* (0.08, 0.73) |

| Treatment condition × homelessness | 5.11** (1.81, 14.44) |

| Model χ2 | 111.56*** |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; TRC = Trauma Recovery Center; UC = usual care.

* P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of injured victims of violent crimes filing a victim compensation claim, by treatment condition (Trauma Recovery Center [TRC] or usual care) and age (a), education (b), and homelessness (c): Trauma Recovery Center Demonstration Project, San Francisco, California, 2001–2006.

Note. The percentages reported for filing a claim are adjusted for the victim characteristics included in the regression model.

For those assigned to usual care, those 35 years or younger were significantly less likely to file claims (12%) than were those older than 35 years (30%; F = 9.53; P = .002), whereas for those assigned to Trauma Recovery Center services, younger and older victims were equally likely to file claims (54% and 57% of victims, respectively; F = 0.24; P = .62).

A similar pattern was found for education. In usual care, those with less than a high school education were less likely to file claims (13%) than were those with a high school education or beyond (28%; F = 6.21; P = .02). For those assigned to Trauma Recovery Center services, education status was not related to filing a claim (57% of those with less than high school, 55% of those with high school or beyond; F = 0.08; P = .78).

For housing status, although homeless victims were less likely to file a claim than were housed victims in both treatment conditions, this gap was smaller and only marginally significant for those assigned to the Trauma Recovery Center (49% of homeless victims received compensation vs 60% of housed victims; F = 2.88; P = .09), compared with those in usual care (8% of homeless victims vs 34% of housed victims; F = 18.58; P < .001).

There were no other significant interactions, indicating that treatment condition did not differentially affect likelihood of filing a claim according to gender, ethnicity, type of crime, or other victim characteristics.

DISCUSSION

Of eligible crime victims, only a small proportion applies for and ultimately receives state victims’ compensation. National evaluations find that victims who are male, are younger, belong to an ethnic minority group, and are victims of physical assault are less likely to access the victim compensation system than are other groups of victims. In this demonstration project with disadvantaged crime victims in California, in the absence of active assistance, younger, less educated, and homeless victims were less likely to file claims for compensation than were their older and more socioeconomically advantaged counterparts. Active outreach and assistance to victims not only increased the overall proportion of victims filing claims but also reduced these disparities. In particular, comprehensive services diminished disparities associated with homelessness, education, and age. Among victims who were assigned to Trauma Recovery Center services, very few refused to submit an application (3%). Rather, most victims who did not file claims never or only briefly engaged in Trauma Recovery Center services. This suggests that the primary barriers to filing a claim are lack of information about victim compensation and difficulty navigating the application process, not lack of interest or reluctance to access the system.

The goal of government victim compensation programs is to provide the resources necessary to cover losses and to pay for services necessary for physical and psychological recovery. Therefore, victim compensation programs would be expected to serve as a gateway to needed medical, mental health, and social services that might not otherwise be obtainable. However, for disadvantaged crime victims it may be that social services and assistance similar to that provided at the Trauma Recovery Center are the gateway to accessing victim reimbursement. Direct service models appear to be a necessary addition to the current claims-based model to adequately serve disadvantaged victims of crime.

Some study limitations should be noted. First, the sample includes only victims of violent crime presenting for emergency medical care and therefore excludes some types of victims eligible for compensation (e.g., robbery victims who do not suffer injuries, family members of homicide victims). Further, sexual assault victims and non-English speakers could not be included in the randomized trial. As a result, a full test of the impact of treatment condition on possible disparities in victim compensation according to type of crime or language spoken could not be performed. This may explain why gender and ethnic disparities in the use of the victim compensation system found in other samples were not present.9,10

Second, because of the small number of claims submitted by victims in the usual-care condition and the very small number of denied claims, we could not explore potential disparities in the approval or denial of submitted claims. Finally, access to victim compensation was examined only in a single county in California. Disparities in access to victim compensation and strategies useful to address disparities may differ across geographic regions because of differences in population characteristics, crime rates, and community perceptions of law enforcement and victims services.

Providing outreach and direct assistance can increase the overall number of individuals who receive victim compensation and is particularly helpful in assisting those with the fewest resources to navigate the victim compensation system. Efforts to reach out to disadvantaged victims and provide assistance can help them receive the compensation and services they need to restore their lives after violent victimization.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the State of California Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board and by funds from the California Program on Access to Care (CPAC), California Policy Research Center, University of California (grant ENN02N).

The authors would like to thank Sukyung Chung, Eric Kessell, Kevin Mack, and George Unick for their comments on an earlier version of the article.

Note. The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily represent those of the regents of the University of California, CPAC, its advisory board, or any state or county executive agency represented thereon.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors J. Alvidrez conceptualized the study and conducted data analysis. M. Shumway and A. Boccellari assisted with data analysis and interpretation. J. D. Green, V. Kelly, and G. Merrill assisted with development of the data collection procedures.

References

- 1.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998; 55:626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller TR, Cohen MA, Wiersema B. Victim costs and consequences: a new look. National Institute of Justice Research Report, NCJ 155282; 1996. Available at: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/victcost.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 3.Solomon SD, Davidson JRT. Trauma: prevalence, impairment, service use, and cost. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarnoff SK. Paying for Crime: The Policies and Possibilities of Crime Victim Reimbursement. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1996.

- 5.Hobfoll SE, Tracy M, Galea S. The impact of resource loss and traumatic growth on probable PTSD and depression following terrorist attacks. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:867–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:52–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodino PW. Current legislation on victim assistance. Am Psychol. 1985;40:104–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herman S, Waul M. Repairing the harm: a new vision for crime victim compensation in America. Washington, DC: National Center for Victims of Crime; 2004. Available at: http://www.ncvc.org/ncvc/AGP.Net/Components/documentViewer/Download.aspxnz?DocumentID3=8573. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 9.Newmark L, Bonderman J, Smith B, Liner B. The national evaluation of state Victims of Crime Act compensation and assistance programs: trends and strategies for the future. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003. Available at: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/410924_VOCA_Full_Report.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 10.Newmark L, Schaffer M. Crime victim compensation in Maryland: accomplishments and strategies for the future. Report to the Maryland Governor’s Office of Crime Control and Prevention. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003. Available at: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/410799_Compensation_MD.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 11.Newmark LC. Crime victims’ needs and VOCA-funded services: findings and recommendations from two national studies. Alexandria, VA: National Institute of Justice; 2004. Report 214263. Available at: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/214263.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 12.Danis FS. Domestic violence and crime victim compensation. Violence Against Women. 2003;9: 374–390. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith HP. Violent crime and victim compensation: implications for social justice. Violence Vict. 2006;21: 307–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.California State and Consumer Services Agency. Strengthening victim services in California: a proposal for consolidation, coordination, and victim-centered leadership. 2003. Available at: http://www.boc.ca.gov/docs/reports/scsareport.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 15.California Victim Compensation and Claims Board. California Victim Compensation Program Newsletter, June 2006. Available at: http://www.vcgcb.ca.gov. Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 16.United States Department of Justice. Crime—State Level: One Year of Data. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. Available at: http://bjsdata.ojp.usdoj.gov/dataonline/Search/Crime/State/RunCrimeOneYearofData.cfm Accessed February 1, 2007.

- 17.California State Senate Rules Committee, Office of Senate Analysis. July, 2007. AB 1669.

- 18.Boccellari A, Okin RL, Alvidrez J, Shumway M, Green JD, Penko J. California State Crime Victims’ Services: Do They Meet the Mental Health Needs of Disadvantaged Crime Victims? Report to the California Program on Access to Care, California Policy Research Center. San Francisco: University of California; 2006.

- 19.Boccellari A, Alvidrez J, Shumway M, et al. Characteristics and psychosocial needs of victims of violent crime identified in a public-sector hospital: data from a large clinical trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2007;29: 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Prior HHSA Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.shtml. Accessed August 1, 2007.

- 21.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied Multiple Regression/ Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983.