Abstract

Objectives. We measured the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) immunization and HBV infection among men aged 23 to 29 years who have sex with men.

Methods. We analyzed data from 2834 men who have sex with men in 6 US metropolitan areas. Participants were interviewed and tested for serologic markers of immunization and HBV infection in 1998 through 2000.

Results. Immunization prevalence was 17.2%; coverage was 21.0% among participants with private physicians or health maintenance organizations and 12.6% among those with no source of health care. Overall, 20.6% had markers of HBV infection, ranging from 13.7% among the youngest to 31.0% among the oldest participants. Among those susceptible to HBV, 93.5% had regular sources of health care, had been tested for HIV, or had been treated for a sexually transmitted disease.

Conclusions. Although many young men who have sex with men have access to health care, most are not immunized against HBV. To reduce morbidity from HBV in this population, providers of health care, including sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevention services, should provide vaccinations or referrals for vaccination.

Although the incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has declined more than 70% since it peaked in the mid-1980s, an estimated 60000 Americans were newly infected with HBV in 2004.1 Men who have sex with men (MSM) are at high risk for HBV infection: those aged 20 to 39 years have the highest rate of reported acute HBV infection, and from 1996 to 2002 the percentage of reported acute cases among MSM increased.2 Data also continue to show high incidence of hepatitis A and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and high prevalence of HIV infections among MSM.3–7 Because of these facts, integration of prevention services for MSM such as STD testing and treatment, HIV testing, and hepatitis A and B vaccinations has become a public health priority.5 Many MSM diagnosed with acute hepatitis A or B infection report visiting primary health care providers within the past year8 or using a regular source of health care.9,10 These infections could have been prevented by vaccination.

The need for improved vaccination coverage against HBV among young MSM was shown by the results of the Young Men’s Survey (YMS).9 Phase 1 of the YMS was conducted in 7 US cities in the mid-1990s, and results show that only 9% of 3432 MSM aged 15 to 22 years had serologic evidence of immunization and self-reported vaccination. Eleven percent of these young men had serologic markers of previous HBV infection. Prevalence of past or current infection ranged from 2% among those aged 15 years to 17% among those aged 22 years, indicating a high annual incidence of infection.9

To determine whether trends in the prevalence of HBV infection and immunization found among young MSM in YMS phase 1 continued among older MSM, we analyzed the results of YMS phase 2 and compared them with the results of phase 1.

METHODS

Sampling Procedure

YMS phase 1 was a cross-sectional anonymous survey of men aged 15 to 22 years who attended MSM-identified venues (e.g., dance clubs) in Baltimore, Maryland; Dallas, Texas; Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; Miami, Florida; New York, New York; and Seattle, Washington, in 1994 to 1998. YMS phase 1 methods have been described previously.11 Conducted in 6 of the 7 phase-1 cities (all except San Francisco) from 1998 to 2000, YMS phase 2 used the same methods as phase 1 with the exception of enrolling men aged 23 to 29 years. Other eligibility criteria included residing in the selected metropolitan areas and having never previously participated in YMS phase 2. Venues for enrollment were identified from advertisements, individual and group interviews, and field observations. Sampling frames were constructed of venues and any periods of the day during which a minimum of 7 eligible men might be encountered during a 4-hour sampling effort. Each month, 12 or more venues and their associated times were randomly selected from sampling frames of venues in these cities. These venues and periods were scheduled for sampling in the upcoming month. During sampling events, recruiters approached men who appeared to be under age 30 years and asked them to participate in a brief eligibility interview.

In a nearby van or office location, trained interviewers obtained informed consent from participants, administered a standard questionnaire, conducted prevention counseling, and obtained blood specimens. Interview subjects included sociodemographics, health care use, social factors (including the degree to which participants disclosed their sexual identify to others), and sexual and substance-use behaviors. Health care use questions assessed the use and sources (if applicable) of health care and whether respondents had ever been vaccinated against HBV, tested for HIV, or diagnosed with an STD. Participants were reimbursed $50 for their time and were scheduled to receive their laboratory test results within 2 weeks. Participants who returned for their test results received risk-reduction counseling and referrals for health care if needed.

Interviewers rated their confidence in the validity of the participant’s answers after each interview. Low-confidence interviews were those with contradictory responses, open hostility toward the interviewer, or impaired judgment from suspected alcohol or drug use. Data from low-confidence interviews were removed from analyses. The YMS protocol was approved by institutional review boards at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and at state and local institutions conducting the survey.

Laboratory Testing

Specimens were tested for antibody to HBV surface antigen (anti-HBs), antibody to HBV core antigen (anti-HBc), and HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) at 6 local laboratories with assays licensed by the Food and Drug Administration. We defined vaccine-associated immunity by the presence of anti-HBs with no other serologic markers of HBV infection, independent of self-reported history of HBV vaccination. Current or chronic HBV infection was defined by the presence of HBsAg confirmed with either anti-HBc, high-titer, or neutralization assay. HBV infection (including chronic infection and previous infection) was defined by the presence of anti-HBc or confirmed HBsAg. Susceptibility to HBV infection was defined as absence of the 3 serologic markers; in addition, persons with unconfirmed HBsAg alone were considered susceptible.

After all interview and laboratory results were collected, antibody profile assays were used to test specimens of participants suspected of enrolling twice.12 When antibody profiles matched, indicating that a participant had enrolled twice, only data from the first interview and specimen were analyzed.

Data Analysis

Prevalence of immunization and HBV infection (chronic and past) were reported overall and for each of the 6 sites. In univariate analyses examining predictors of immunization and infection, we used the Cochran–Armitage trend test for interval-scaled data and the χ2 test for categorical data. The α level was set at less than .05.

To assess independent predictors of immunization and infection, 2 separate multiple logistic regression models were used. For both models, we used stepwise logistic regression, with an entry criterion of a P value of less than .05 and a retention criterion of a P value of less than .05, to enter each variable that was found to be associated (at P<.05) in our univariate analysis or suspected to be associated with hepatitis B immunization or infection in the literature. Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistics were used to assess model fit (P=.45 for immunization model; P=.32 for infection model). We used a general linear model to evaluate the prevalence of HBV infection by age with data from both YMS phases 1 and 2. Finally, we examined the proportion of participants who were found to be susceptible to HBV infection who used health care services. We used SAS version 8 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary NC) for all analyses.

RESULTS

Participants

At 181 venues in the 6 cities, staff enrolled 3137 (58%) of the 5443 men who were identified as eligible. Of the 3137 participants, data from 53 (2%) with antibody profile duplicates and 13 (0.4%) with low interviewer confidence were removed from analyses. Of the remaining 3071 men, 2968 (97%) had serologic samples usable for HBV serologic testing. Of these, 134 (5%) reported never having had oral or anal intercourse with men. We limited our analysis to the remaining 2834 men who had ever had sexual intercourse with men.

Racial and ethnic characteristics of the enrolled men varied across the 6 study sites (Table 1 ▶). Overall, 49% were aged 23 to 25 years, 44% were college graduates, almost three quarters (72%) were employed full time, and 13% were employed part time. Ninety-five percent of the participants reported ever having had anal intercourse with a man, and 7% reported ever having injected drugs (Table 2 ▶). Eighty-one percent had 6 or more lifetime male sexual partners.

TABLE 1—

Recruitment Outcomes and Demographic Characteristics of Men Who Have Sex With Men, by Metropolitan Area: Young Men’s Survey Phase 2, 1998–2000

| Baltimore | Dallas | Los Angeles | Miami | New York | Seattle | All | |

| Recruitment | |||||||

| Venues, No. | 19 | 26 | 40 | 32 | 38 | 26 | 181 |

| Participation rate,a % | 58 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 59 | 54 | 58 |

| Enrolled, No. | 488 | 459 | 436 | 452 | 533 | 466 | 2834 |

| Age, y, % | |||||||

| 23–25 | 53 | 49 | 46 | 48 | 54 | 44 | 49 |

| 26–29 | 47 | 51 | 54 | 52 | 46 | 56 | 51 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | |||||||

| Asian | 3 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 5 |

| Black | 30 | 20 | 10 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 17 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 26 | 22 | 54 | 30 | 6 | 23 |

| White | 59 | 51 | 53 | 35 | 23 | 78 | 49 |

| Mixed/other | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| Education, y, % | |||||||

| < 12 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| 12 | 26 | 23 | 18 | 22 | 23 | 16 | 21 |

| 13–15 | 27 | 34 | 32 | 35 | 25 | 27 | 30 |

| 16 | 29 | 28 | 36 | 29 | 35 | 46 | 34 |

| > 17 | 14 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

aRate was for men identified as eligible; 53 duplicate participants were excluded.

TABLE 2—

Hepatitis B Virus Immunization and Infection Among 2834 Men Who Have Sex With Men, by Demographic Characteristics, Access to Health Care, and Risk Behaviors: Young Men’s Survey Phase 2, 1998–2000

| No. (%) | Hepatitis B Immunization, % (95% CI) | HBV Infection,a % (95% CI) | HBV Infection, AORb (95% CI) | |

| Total | 2834 (100) | 17.2 (15.7, 18.4) | 20.6 (19.1, 22.1) | |

| Study Sitec,d | ||||

| Dallas, TX | 459 (16.2) | 13.7 (10.8, 17.2) | 24.0 (20.1, 27.9) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) |

| New York, NY | 533 (18.8) | 14.8 (12.0, 18.0) | 28.3 (24.2, 31.8) | 2.1 (1.4, 2.9) |

| Los Angeles, CA (Ref) | 436 (15.4) | 15.4 (11.6, 18.4) | 15.6 (12.6, 19.4) | 1.00 |

| Baltimore, MD | 488 (17.2) | 16.0 (12.7, 19.3) | 17.8 (14.6, 21.4) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) |

| Miami, FL | 452 (15.9) | 17.0 (13.5, 20.5) | 17.5 (13.5, 20.5) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) |

| Seattle, WA | 466 (16.4) | 26.4 (22.0, 30.0) | 19.3 (15.4, 22.6) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) |

| Race/ethnicityc,d | ||||

| White (Ref) | 1395 (49.2) | 20.4 (18.2, 22.5) | 16.1 (14.2, 18.0) | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | 676 (23.9) | 13.5 (10.9, 16.1) | 21.5 (18.4, 24.6) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) |

| Asian | 155 (5.5) | 29.0 (21.9, 36.1) | 24.5 (17.7, 31.3) | 2.5 (1.6, 3.8) |

| Black | 485 (17.1) | 10.1 (7.4, 12.8) | 31.6 (27.5, 35.7) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) |

| Age,d y | ||||

| 23–25 (Ref) | 1384 (48.8) | 18.1 (16.1, 20.1) | 14.9 (13.0, 16.8) | 1.00 |

| 26–29 | 1444 (51.0) | 16.4 (14.5, 18.3) | 26.1 (23.8, 28.4) | 2.0 (1.62, 2.5) |

| Education,c,d y | ||||

| < 12 (Ref) | 122 (4.3) | 9.0 (3.9, 14.1) | 35.3 (26.8, 43.8) | 1.00 |

| 12 | 607 (21.4) | 10.1 (7.7, 12.5) | 28.8 (25.2, 32.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) |

| 13–15 | 842 (29.7) | 13.8 (11.5, 16.1) | 19.6 (16.9, 22.3) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) |

| 16 | 958 (33.8) | 21.6 (19.0, 24.2) | 17.6 (15.2, 20.0) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) |

| > 17 | 305 (10.8) | 30.2 (25.0, 35.4) | 13.1 (9.3, 16.9) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) |

| Annual income,d $ | ||||

| < 20 000 (Ref) | 1068 (37.7) | 15.2 (13.0, 17.4) | 25.2 (22.6, 27.8) | 1.00 |

| > 20 000 | 1766 (62.3) | 18.4 (16.6, 20.2) | 18.2 (16.4, 20.0) | 0.72 (0.6, 0.9) |

| Ever had a diagnosis of STDc | ||||

| No (Ref) | 2074 (73.4) | 17.6 (16.0, 19.2) | 16.0 (12.0, 20.0) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 750 (26.6) | 16.0 (13.4, 18.6) | 33.2 (27.4, 39.0) | 1.9 (1.6, 2.4) |

| Anti-HIV serologyc,d | ||||

| Negative (Ref) | 2480 (87.5) | 17.9 (16.4, 19.4) | 17.1 (13.5, 20.7) | 1.00 |

| Positive | 354 (12.5) | 12.4 (9.0, 15.8) | 45.5 (37.8, 53.2) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.3) |

| Lifetime male partnersd | ||||

| 1–50 (Ref) | 2234 (78.8) | 17.6 (16.0, 19.2) | 17.9 (16.3, 19.4) | 1.00 |

| ≥ 51 | 600 (21.2) | 15.7 (12.8, 18.6) | 31.0 (27.3, 34.7) | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1) |

| Ever had anal intercoursed | ||||

| No (Ref) | 139 (4.9) | 19.4 (12.8, 26.0) | 9.4 (4.5, 14.3) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2695 (95.1) | 17.1 (15.6, 18.5) | 21.2 (19.7, 22.7) | 1.9 (1, 3.4) |

| Ever injected drugsd | ||||

| No (Ref) | 2632 (92.6) | 17.3 (15.9, 8.7) | 19.7 (18.2, 21.2) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 202 (7.1) | 17.2 (12.0, 22.4) | 32.7 (26.2, 39.2) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) |

| Disclosed sexual orientationc | ||||

| To less than half of acquaintances | 1890 (67.3) | 14.1 (11.8, 16.3) | 23.5 (20.8, 26.3) | |

| To at least half of acquaintances | 918 (32.7) | 19.0 (17.1, 20.6) | 19.4 (17.6, 21.2) | |

| Ever tested for HIVb,d | ||||

| No | 315 (11.1) | 16.2 (12.1, 20.3) | 14.9 (10.9, 18.8) | |

| Yes | 2518 (88.8) | 17.3 (15.8, 18.8) | 21.4 (19.8, 23.0) | |

| Regular source of health careb,c | ||||

| None | 1040 (36.7) | 12.6 (10.6, 14.6) | 21.9 (19.4, 24.4) | |

| Doctor or HMO | 1257 (44.4) | 21.0 (18.7, 23.3) | 17.5 (15.4, 19.6) | |

| School, company, or military clinic | 106 (3.7) | 28.3 (19.7, 36.9) | 13.2 (6.8, 19.6) | |

| Public clinic | 188 (6.6) | 16.5 (11.2, 21.8) | 27.1 (20.7, 33.5) | |

| Hospital or emergency department | 208 (7.3) | 13.5 (8.9, 18.1) | 29.8 (23.6, 36.0) | |

Note. CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; STD = sexually transmitted disease; HMO = health maintenance organization. Hepatitis B immunization was determined by the presence of antibodies to HBV surface antigen in the absence of other seromarkers. HBV-prevalent infection was defined as the presence of HBV surface antigen or antibody to HBV core antigen.

aTotal number of men who have sex with men tested = 2829; 5 participants did not have hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen test results.

bBecause this logistic model was estimating odds of ever being infected with HBV given potential exposures or risk behaviors, variables related to healthcare access were not included in the model. AORs are presented only for variables that remained significant in the final logistic models.

cSignificant differences existed (P < .05) in univariate analysis of immunization levels.

dSignificant differences existed (P < .05) in univariate analysis of HBV infection levels.

Immunization Coverage

Overall, 17.2% (487) of the participants had serologic evidence of hepatitis B immunization, ranging from 13.7% to 26.4% across sites (Table 2 ▶), and 31.4% (891) reported receiving at least 1 dose of HBV vaccine; overall 13.3% both reported HBV vaccination and had serologic evidence of vaccination. Receipt of a full 3-dose HBV vaccination series was reported by 25.7% (728) of respondents, and 5.8% (163) reported receiving an incomplete vaccine series. Anti-HBs seropositivity alone was found among 46.3% (337/728) who reported receiving 3 vaccine doses, 25.2% (41/163) who reported fewer than 3 doses, and 5.6% (109/1943) of those with no history of vaccination. Of those with serologic evidence of immunization, 77.6% (378/487) reported receiving at least 1 vaccine dose in the past.

Immunization against HBV varied among study sites; Seattle participants had the highest immunization coverage (Table 2 ▶). Coverage decreased with increasing age (from 19.9% among 23-year-olds to 14.0% among 29-year-olds; P = .01) and increased with increasing years of education (P < .001). Prevalence of immunization did not vary by participant risk behavior, including lifetime numbers of sexual partners and injection drug use. Individuals who reported having disclosed their sexual orientation to at least “half the people they know” were more likely to be immunized than were those who had disclosed to fewer than half of their acquaintances (19.0% vs 14.1%; P = .002).

Of 1363 (48.0%) participants who reported using a regular source of health care (i.e., a private physician, health maintenance organization, or school, company, or military clinic), 21.6% were immunized; 13.1% of men with no usual source of care or who used a hospital, emergency department, or public clinic were immunized (P < .001). Participants reporting having ever been tested for HIV or diagnosed with an STD were equally as likely to be immunized as other respondents (16.2% vs 17.3%; P = .64). HIV-seropositive men were less likely to be immunized than were HIV-seronegative men (12.4% vs 17.9%; P = .01), although among the 92 individuals who knew that they were HIV infected, 21.7% were immunized compared with 9.9% of the 203 persons who first learned that they were HIV seropositive at the time of their YMS interview (P = .006).

A multiple logistic regression model (results not shown) found that more years of education, younger age, Asian or White race, living in Seattle, and having a regular source of medical care were independently associated with immunization. When we used self-report of HBV vaccination as the marker of immunization, we found that the same factors that were associated with immunization were associated with self-reported vaccination. However, although men who were HIV seropositive were less likely to be immunized, equal percentages of men who were HIV seropositive and seronegative reported having received 3 doses of vaccine (27.1% and 25.5%, respectively; P = .51).

Prevalence of Hepatitis B Infection

Overall, 20.6% (585) of participants had serologic evidence of HBV infection, including 2.3% (64) who had current or chronic infection. HBV infection was significantly higher among Blacks and Asians than among Whites (Table 2 ▶). HBV infection prevalence was lower with increasing years of education; individuals with at least 17 years of education had half the prevalence of infection of persons with fewer than 12 years of education (Table 2 ▶). In a multivariate logistic model that controlled for study site, race, age group, years of education, annual income, and HIV infection, HBV infection was significantly associated with a history of having an STD, having more lifetime partners, ever engaging in anal intercourse, and ever using injection drugs (Table 2 ▶).

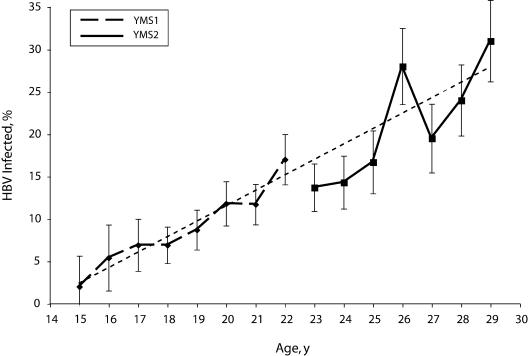

HBV infection in YMS phases 1 and 2 increased linearly with age (Figure 1 ▶). Prevalence in phase 1 ranged from 1.8% among 15-year-olds to 17.1% among 22-year-olds; in phase 2, prevalence ranged from 13.7% among 23-year-olds to 31.1% among 29-year-olds.

FIGURE 1—

Trends in hepatitis B infection among men aged 15 to 29 years who have sex with men, by age: Young Men’s Survey Phases 1 and 2, 1994 to 2000.

Note. HBV = hepatitis B virus. HBV infection was defined as the presence of HBV core antibody or HBV surface antigen. Cities included in Young Men’s Survey (YMS) phase 1: Baltimore, Maryland; Dallas, Texas; Miami, Florida; Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; New York, New York; and Seattle, Washington. YMS phase 2 included all except San Francisco. Linear regression showed no significant differences between the slopes (P = .25) or intercepts (P = .13) of the YMS phase-1 and phase-2 samples. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Dotted line represents linear estimate of trend.

Susceptible and Unvaccinated Participants

Sixty-two percent (1762/2834) of participants tested negative for all HBV serologic markers. Of these MSM who were susceptible to infection, 93.5% (1647) reported having a regular source of health care (such as a doctor, health maintenance organization, or school or company clinic [47.4%] or a hospital or community clinic [14.8%]), having been tested for HIV (87.6%), or having been diagnosed with an STD (21.7%; data not shown).

The 1550 susceptible participants who had previously been tested for HIV reported testing a median of 3 times (interquartile range: 2–6). Of the 1631 (57.6%) anti-HBs–seronegative participants who reported never having been vaccinated against HBV, 93.3% had had 1 of the above opportunities for vaccination. Among these participants, 795 (48.7%) had not talked to their doctors about the HBV vaccine, 793 (48.6%) reported not knowing about the vaccine, and 263 (16.1%) believed they were at low risk for infection (categories were not mutually exclusive).

DISCUSSION

Immunization and Infection

Despite more than 2 decades of public health recommendations to vaccinate MSM against HBV, we found that fewer than 20% of MSM aged 23 to 29 years residing in 6 major US urban centers were immunized against HBV. The 13% who both reported HBV vaccination and had serologic evidence of immunization represented a very small increase in vaccine coverage compared with 9% among MSM aged 15 to 22 years surveyed in YMS phase 1 (1994–1998).10 The increasing HBV prevalence observed in the YMS studies from 1.8% among 15-year-olds in phase 1 to 31.1% among 29-year-olds in phase 2 is likely to be related to the low HBV vaccination coverage and higher prevalence of risk behaviors among the older MSM cohort. As has been found in other studies,13,14 sexual behavior and injection drug use continue to be associated with HBV transmission among MSM.

Missed Opportunities

Part of the ongoing failure to prevent HBV infection among MSM may be attributable to missed vaccination opportunities in HIV/STD prevention systems.9,15–17 Others have described how STD testing and treatment venues miss opportunities for HBV infection prevention: Goldstein et al. found that 35.6% of persons with acute HBV infection had been previously treated for an STD,15 and Williams et al. found that 39% of patients with HBV infection had visited STD clinics in 6 US counties.17 Furthermore, Williams et al. found that approximately 55% of patients with acute HBV infections who were MSM had previously been seen in an STD clinic.

In our study, nearly all participants who were susceptible to HBV infection either had been tested for HIV at least once or had received STD treatment services. In YMS phase 1, HIV-tested MSM were more likely to be vaccinated against HBV,9 but YMS phase 2 did not find this correlation. A higher percentage of YMS phase 2 than phase 1 participants used HIV testing (88% vs 65%) or STD services (22% vs 13%)9; fewer YMS phase 2 participants reported using a regular source of health care (63%, vs 90% in YMS phase 1).10 Therefore, HIV and STD testing and treatment systems may be even more promising sites for HBV infection prevention for men in their 20s than for younger men. Although federal guidelines for STD treatment have recommended routine hepatitis A and B immunization for MSM in addition to annual testing for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea,5 federal HIV counseling and testing guidelines do not include recommendations for HBV vaccination.18

Participants reporting a regular source of health care had a higher prevalence of immunization than did those without regular health care. However, even among persons with a source of care, relatively few (1 in 5) were immunized. Many HBV-susceptible MSM were unaware of the HBV vaccine or had not discussed it with a health care provider. Low levels of vaccination may be attributable to providers’ reluctance to inquire about sexual and drug-related risk behaviors. Assessment of patients’ risk behaviors is recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force and by professional medical organizations.19 Risk assessment also has the ancillary benefit of identifying candidates for other prevention interventions (e.g., screening for HIV infection and other STDs and drug treatment counseling).

Although the US Preventive Services Task Force has, since 1996, recommended asking all patients about risk behaviors,19 surveys of physicians and patients during 1995 to 1999 found that less than 50% of patients were asked about sexual behaviors.20–23 Furthermore, although MSM may be reluctant to report their sexual behaviors to their providers because of perceived provider attitudes, we observed low immunization prevalence even among the approximately one third of participants in this survey who reported being “completely out” to everyone. Identifying at-risk MSM through taking sexual histories is important, but providers need to respond by recommending appropriate prevention services for MSM once they have been identified.

Limitations

Because of the lack of concordance between self-reported vaccination history and serology showing only anti-HBs, we used serologic evidence as the marker for immunization, assuming some persons might be misremembering their history of HBV vaccination.24–27 Because detectable anti-HBs wanes with time after immunization, and because HIV infection is associated with lower vaccine efficacy, the immunization coverage reported here should be considered a minimum estimate. Waning anti-HBs titer might explain some of the difference we found between vaccination self-report and serologic evidence of immunization.28 We found the largest discrepancy between self-report and serology among HIV-seropositive men. Thus, although we report that 17% had evidence of immunization, as many as 32% may have received at least 1 dose of vaccine.

An additional limitation to this analysis was in attempting to determine a trend in HBV infection incidence from the cross-sectional data of YMS phase 1 and phase 2. Phase 1 was conducted earlier among younger MSM and found a lower prevalence of HBV infection; in phase 2, conducted later and among older men, higher prevalence was found. There is no assurance that these cross-sectional prevalence estimates by age actually reflected incidence of infection rather than an age cohort effect; however, low immunization coverage and high numbers of male sexual partners could result in increasing prevalence, as seen in Figure 1 ▶. The higher HBV infection prevalence among 26-year-olds in the YMS phase 2 study is also noteworthy; this was found in all sites and across racial and ethnic groups. Indicators of risk behaviors, including injection drug use, history of jail stay, number of times tested for HIV, and number of lifetime sexual partners, did not correlate with increased prevalence in men aged 26 years, and immunization in this age group was not lower than that of adjacent groups. We are therefore unable to explain this observation.

This study reports findings related to hepatitis B immunization and infection among self-identified MSM recruited from selected public venues in urban areas. Although others have found that high percentages (74%–91%) of young MSM participating in randomized household telephone surveys have attended 1 of these venues,14 the venue-based sampling strategy limits the generalizability of our findings. Because of our reliance on self-identification, we also were unable to sample men who would deny having sexual intercourse with men. Further studies in nonurban communities and alternative sampling methods that can find men who will not self-identify may be needed to derive a more comprehensive portrait of trends in MSM in the United States.

Conclusions

Although there has been great success in widespread hepatitis B vaccination and subsequent lowering of HBV infections among children and young adolescents,29 it is essential that efforts continue to immunize MSM during the years before universal childhood hepatitis B vaccination programs eliminate new HBV infections among adults. A report of the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System from November 2003 to April 2005 found that 54% of MSM aged 25 to 34 years self-reported receiving a hepatitis vaccination, including vaccination against either hepatitis A or B, suggesting that vaccination coverage may be continuing to increase among this at-risk population.30 Another survey found that hepatitis B vaccination in STD clinic settings may be increasing.31 Addressing missed opportunities for HBV infection prevention in both primary health care and HIV and STD prevention systems could eliminate HBV transmission among MSM in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the young men who volunteered for this research project and to the dedicated staff who contributed to its success. We are especially grateful to the Young Men’s Survey (YMS) coordinators: David Forest (Miami), Henry Artiguez (Miami), Vincent Guilin (New York City), John Hylton and Karen Yen (Baltimore), Tom Perdue (Seattle), Santiago Pedraza (Dallas), and Denise Johnson (Los Angeles). We appreciate and acknowledge the dedicated effort of laboratory and data management staff in all cities. We also thank David Culver (Division of Viral Hepatitis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for statistical expertise.

The following organizations participated in the YMS: Baltimore: Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, Baltimore City Health Department, and Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Dallas: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and Texas Department of Health; Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Department of Public Health; Miami: Health Crisis Network, University of Miami, and Florida Department of Health; New York City: New York Blood Center and New York City Department of Health; San Francisco: San Francisco Department of Public Health; Seattle: Public Health–Seattle and King County and HIV/AIDS.

The following are the members of the YMS Group: Baltimore: David D. Celentano and John B. Hylton; Dallas: Anne C. Freeman, Douglas A. Shehan, Santiago Pedraza, and Eugene Thompson; Los Angeles: Peter R. Kerndt, Wesley L. Ford, Susan R. Stoyanoff, Denise Johnson, and Bobby Gatson; Miami: Al Bay, John Kiriacon, Marlene LaLota, and Thomas Liberti; New York City: Vincent Guilin, Beryl A. Koblin, and Lucia V. Torian; San Francisco: William McFarland; Seattle: Thomas Perdue and Hanne Thiede; CDC: Bradford N. Bartholow, Stephanie K. Behel, Robert S. Janssen, Duncan A. MacKellar, Gina M. Secura, and Linda A. Valleroy.

Human Participant Protection The Young Men’s Survey protocol was approved by institutional review boards at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and at state and local institutions conducting the survey.

Peer Reviewed

Note. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributors C. M. Weinbaum led the writing of the article and analyzed and interpreted the data. R. Lyerla originated the article and contributed to its writing and analyses. D. A. MacKellar and L. A. Valleroy originated and designed the study and assisted in the interpretation of data. G. Secura and S. Behel contributed to the national coordination of the study and assisted in the management and analysis of data. T. Bingham, D. D. Celentano, B. A. Koblin and H. Thiede, M. LaLota, D. Shehan, and L. V. Torian were responsible for the scientific and operational oversight of the studies; they also contributed to the interpretation and analysis of the data.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease burden from Hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/resource/PDFs/disease_burden2004.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2006.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis Surveillance Report No. 59. Atlanta, Ga: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2004.

- 3.Blocker ME, Levine WC, St Louis ME. HIV prevalence in patients with syphilis, United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of syphilis among men who have sex with men—Southern California, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(7):117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-6):1–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis–United States, 2000–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(43): 971–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, Levine WC. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter SM, Sansom S, Long T, Koch E, Kellerman S, Smith F, et al. Outbreak of hepatitis A among men who have sex with men: implications for hepatitis A vaccination strategies. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, et al. Two decades after vaccine license: hepatitis B immunization and infection among young men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond C, Thiede H, Perdue T, et al. Viral hepatitis among young men who have sex with men: prevalence of infection, risk behaviors, and vaccination. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackellar D, Valleroy L, Karon J, Lemp G, Janssen R. The Young Men’s Survey: methods for estimating HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among young men who have sex with men. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(suppl 1): 138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unger TF, Strauss A. Individual-specific antibody profiles as a means of newborn infant identification. J Perinatol. 1995;15:152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn J. Preventing hepatitis A and hepatitis B virus infections among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. Young Men’s Survey Study Group. JAMA. 2000;284:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein ST, Alter MJ, Williams IT, et al. Incidence and risk factors for acute hepatitis B in the United States, 1982–1998: implications for vaccination programs. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handsfield HH. Hepatitis A and B immunization in persons being evaluated for sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 10A):69S–74S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams IT, Boaz K, Openo KP, et al. Missed opportunities for hepatitis B vaccination in correctional settings, sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics, and drug treatment programs. Presented at: 43rd Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; October 5–9, 2005; San Francisco, Calif. Abstract 1031.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. Technical expert panel review of CDC HIV counseling, testing, and referral guidelines. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 2001;50(RR-19):1–110. [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Available at: http://odphp.osophs.dhhs.gov/pubs/guidecps/PDF/CH62.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2006.

- 20.Maheux B, Haley N, Rivard M, Gervais A. STD risk assessment and risk-reduction counseling by recently trained family physicians. Acad Med. 1995;70:726–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bull SS, Rietmeijer C, Fortenberry JD, et al. Practice patterns for the elicitation of sexual history, education, and counseling among providers of STD services: results from the gonorrhea community action project (GCAP). Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maheux B, Haley N, Rivard M, Gervais A. Do physicians assess lifestyle health risks during general medical examinations? A survey of general practitioners and obstetrician-gynecologists in Quebec. CMAJ. 1999;160:1830–1834. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40(RR-13):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suarez L, Simpson DM, Smith DR. Errors and correlates in parental recall of child immunizations: effects on vaccination coverage estimates. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czaja C, Crossette L, Metlay JP. Accuracy of adult reported pneumococcal vaccination status of children. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein KP, Kviz FJ, Daum RS. Accuracy of immunization histories provided by adults accompanying preschool children to a pediatric emergency department. JAMA. 1993;270:2190–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gindi M, Oravitz P, Sexton R, Shpak M, Eisenhart A. Unreliability of reported tetanus vaccination histories. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:120–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzsimons D, Francois G, Hall A, et al. Long-term efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine, booster policy, and impact of hepatitis B virus mutants. Vaccine. 2005;23:4158–4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence of acute hepatitis B—United States, 1990–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004; 52(51–52):1252–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez T, Finlayson T, Drake A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk, prevention, and testing behaviors—United States, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System: men who have sex with men, November 2003–April 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(SS-6):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbert LK, Bulger J, Scanlon K, Ford K, Bergmire-Sweat D, Weinbaum C. Integrating hepatitis B prevention into sexually transmitted disease services: US sexually transmitted disease program and clinic trends–1997 and 2001. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32: 346–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]