Abstract

Background

The remodeling of vein bypass grafts following arterialization is incompletely understood. We have previously shown that significant outward lumen remodeling occurs over the first month of implantation, but the magnitude of this response is highly variable. We sought to examine the hypothesis that systemic inflammation influences this early remodeling response.

Methods and Results

Prospective observational study of patients(N=75) undergoing lower extremity bypass using autogenous vein. Graft remodeling was assessed using a combination of ultrasound and 2D high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Vein graft lumen diameter change from 0–1 month(22.7% median increase) was positively correlated with initial shear stress(P=.016), but this shear-dependent response was disrupted in subjects with an elevated baseline hsCRP(>5 mg/L). Despite similar vein diameter and shear stress at implantation, grafts in the elevated hsCRP group demonstrated less positive remodeling from 0–1 month(13.5% vs 40.9%, p=.0072). By regression analysis, the natural logarithm of hsCRP(ln-hsCRP), was inversely correlated with 0–1 month lumen diameter change(P=.018). HsCRP(β=−29.7, P=.006), statin therapy(β=23.1, P=.037), and initial shear stress(β=.85, P=.003) were independently correlated with early vein graft remodeling. In contrast, wall thickness at one month was not different between hsCRP risk groups. Grafts in the high hsCRP group tended to be stiffer at one month, as reflected by a higher calculated elastic modulus(E=50.4 vs 25.1 Mdynes/cm2, P=.07).

Conclusions

Early positive remodeling of vein grafts is a shear-dependent response that is modulated by systemic inflammation. These data suggest that baseline inflammation influences vein graft healing, and therefore inflammation may be a relevant therapeutic target to improve early vein graft adaptation.

Keywords: vein, bypass, remodeling, inflammation, ultrasonics, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Vein graft caliber is regulated by a complex interplay of hemodynamic stimuli, fluid-phase mediators, and vein wall biology. Final lumen dimension is ultimately a balance between the magnitude and direction of geometric remodeling. Using high-resolution ultrasound, we have previously demonstrated that lower extremity vein grafts dilate significantly during the first month of implantation, though considerable heterogeneity exists despite similar anatomic and technical circumstances. (1) Factors regulating the adaptive remodeling of arterialized veins are incompletely understood. Following implantation, the thin-walled vein is subjected to an acute increase in wall tension which induces a wall thickening response.(2) Early vein lumen enlargement (positive lumen remodeling) is conjectured to be a flow-induced, endothelium-dependent response to the acute increase in shear stress.(1, 4) Many other factors, including pre-existing vein pathology, the extent of operative injury, and the magnitude of the subsequent cellular responses, influence the response to these hemodynamic stimuli and contribute to changes in lumen caliber.

Patients with advanced peripheral arterial disease (PAD) undergoing lower extremity bypass reconstructions have an inflammatory phenotype characterized by elevated levels of markers such as high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).(5–9) Recently, we observed that among such patients, those with an elevated preoperative hsCRP (≥ 5 mg/L) level demonstrated an increased incidence of post-operative cardiovascular and vein graft related events.(9) However, the mechanism underlying this observation is unknown.

Endothelial dysfunction is an early manifestation of atherosclerosis and linked to adverse clinical events. Numerous investigators have noted an association between CRP, reflecting systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction in the brachial artery.(10, 11) In patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, CRP is independently and negatively associated with ex vivo acetylcholine-induced, endothelium-dependent relaxation of pre-implantation vein rings.(12) However, it is currently unknown whether inflammation affects venous endothelial function in vivo, and to what extent it may influence vein graft healing and changes in lumen caliber. In the present study, we sought to examine the hypothesis that systemic inflammation influences the early lumen remodeling of s lower extremity vein bypass grafts.

Methods

Study design and population

This investigation was designed as a substudy of a larger prospective study examining the relationship between systemic inflammation and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing lower extremity bypass surgery with autogenous vein. Details of the parent study inclusion/exclusion criteria are published elsewhere.(1, 9) Briefly, patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were undergoing primary or redo lower extremity arterial reconstruction with autogenous vein for either critical limb ischemia or lifestyle-limiting claudication. Patients were excluded if a non-autogenous graft was used for any portion of the bypass or if the patient was unlikely to comply with the follow up protocol. In order to ensure that the pre-operative hsCRP measurement represented the patient’s true baseline inflammatory status and was not reflective of an acute process, patients were excluded if there was evidence of local or systemic infection including cellulitis, osteomyelitis, or deep space infection of the foot or if they required operative debridement prior to bypass grafting. Other exclusion criteria included the use of immunosuppressive medication (prednisone, cyclosprine, etc.), recent acute illnesses such as myocardial infarction or stroke, systemic illness such as malignancies, or major surgery within 30 days of the index bypass.

We designed this prospective imaging substudy to characterize the patterns of vein graft remodeling and to examine the association between biomarkers of inflammation and measurements of structural change in the graft. All patients in the parent clinical study who were willing to comply with the imaging protocol were invited to participate in the substudy. The study protocol included duplex ultrasound graft surveillance at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after surgery; at each of these time points additional ultrasound measurements were obtained as outlined below. Patients were also asked to undergo high resolution MR imaging of the grafts at 1, 6, and 12 months. Patients were not eligible for the MRI subgroup if they had metal implants, were claustrophobic, or unable to lie in the gantry for the required imaging acquisition time. All participants in this study provided written informed consent and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA). Subjects were provided financial compensation for the additional time spent to acquire research imaging data.

The current report focuses on an analysis of early (0–1 month) remodeling patterns in this population. The cohort comprises 75 consecutive patients who consented to be in the imaging substudy and had at least one research ultrasound study in this early timeframe available for analysis. Of these, 62 subjects had ultrasound performed at the time of surgery, 51 have ultrasound data at one month, and 41 subjects had a study ultrasound performed at both the time of surgery and at one month. Data from patients who had a single ultrasound at one time point was included for descriptive purposes to represent the population at that particular point in time. Patients who had ultrasound observations at both the time of surgery and 1-month were used to characterize remodeling changes. Among these 75 patients, 28 also had MR imaging of the graft performed at the one-month time point. Study enrollment began in February 2004 and was closed for this analysis in December 2006.

Blood Collection and Assays for Inflammatory Markers

Plasma and blood were collected on the morning of the lower extremity bypass surgery by direct femoral vein puncture after the patient was anesthetized and prior to any surgical incision. Blood was collected into EDTA and citrate vacutainer tubes and immediately iced. Tubes were spun at 3000 revolutions per minute for 20 minutes at 4° C in a refrigerated centrifuge. Baseline plasma samples were stored at −80° C until the time of analysis. Assays for hsCRP, serum amyloid A (SAA), and fibrinogen were performed in a core laboratory using validated, high sensitivity assays as previously described.(9) The upper limit of normal defined for the hsCRP assay in this laboratory is 5 mg/L, a level that we employed for dichotomization in some of the endpoint analyses.

Operating Room Procedure

The vein graft configuration employed for bypass grafting was left to the discretion of the surgeon and depended on the availability of ipsilateral greater saphenous vein (GSV). In the majority of cases, veins were tunneled superficially for ease of graft surveillance. However, if a portion of the vein was tunneled in an anatomic position, the index segment (see below) was chosen in a superficial portion of the conduit. At the completion of the vascular reconstruction, routine completion duplex ultrasonography was performed to evaluate for flow disturbances or areas of stenosis. All intra-operative images were obtained on an ATL HDI 3000 scanner with a 10 MHz transducer.

Once the clinical duplex ultrasound scan was completed, we selected a straight, 5-cm long, superficial segment of graft to serve as the index segment for serial postoperative measurements of graft diameter. The index segment was selected far enough away from either anastomosis to minimize turbulent blood flow. Accurate spatial registration of the index segment for subsequent examinations was assured by carefully marking the distance between the index segment and the proximal anastomosis as well as another anatomic landmark, (e.g. scar or tibial tuberosity), and by placing metallic clips on nearby side branches. Schematic maps of the graft configuration and index segment location were made and shared among study personnel performing postoperative ultrasound and MR imaging to insure consistent interrogation of the index segment over time.

The index segment lumen dimensions were then obtained using a series of M-mode images with a cross-sectional view of the vein graft as previously described.(1) Five lumen diameter measurements were taken at each of five, 1-cm incremental locations along the index segment. These 25 measurements were then used to determine the mean lumen diameter of the index segment for that examination.

To determine vein graft stiffness, a pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurement of the vein graft was obtained as previously reported.(13) First, the length of the graft was measured using an umbilical tape, and this length was used for all subsequent PWV calculations. Then, waveforms of the graft were obtained 1 cm distal to the proximal anastomosis and 1 cm proximal to the distal anastomosis. A time delay between the internal ultrasound scan EKG trigger and the foot of the Doppler waveform was measured with the waveform and the EKG tracing simultaneously displayed. PWV was subsequently calculated as the distance (in meters) between the proximal and distal measurement locations divided by the time difference (in seconds) of the QRS-to-onset of flow waveform at the proximal and distal ends of the graft. At least 10 individual time delays were measured at each location and averaged for this calculation.

Finally, a sagittal view of the index segment accompanied by a gated-doppler waveform was recorded for determinations of volumetric flow and estimations of shear stress as described below.

MRI data acquisition

In order to characterize wall thickness, eligible patients (N=28) signed informed consent for high resolution MR imaging of their bypass grafts postoperatively. MR imaging was performed with a 1.5T GE Excite MR system equipped with 4 G/cm gradients capable of 15 G/cm/ms slew rate. The body coil was used for radiofrequency (RF) transmission (maximum B1 250 mG), and a 5-inch circular coil was used for RF reception. An ECG-gated 2D fast spin echo (FSE) sequence with a double inversion recovery (DIR) black blood module was used for T1-weighted (T1WI) and T2-weighted-imaging (T2WI). For T2WI, a frequency-selective fat suppression pulse was used.

A 256 × 256 matrix with 10 cm FOV and 4 signal averages per phase encode with the “no phase wrap option” were utilized for both contrast weightings; 2.2 min acquisition/ slice, depending on heart rate (HR) and with a 1 (~ 1sec) and 2 (~ 2sec) R-R TR period for T1- and T2WI, respectively. Effective echo times for T1- and T2WI are 14 and 58 ms, respectively. Echo train length was 8 for T1WI and 16 for T2WI, with 32 KHz and 16 KHz bandwidth respectively. In the typical protocol, five 4 mm thick slices orthogonal to the graft, spaced 10 mm apart were acquired sequentially over 10–11 minutes per contrast weighting.

Post-acquisition measurements were performed by direct planimetry using dedicated 3D post-processing software (Vital Images software version 3.9, Minnetonka, MN).

Follow-up Imaging Protocol

Postoperative examinations were performed in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Vascular Laboratory. Subjects were examined at rest and in a supine position to allow normalization of heart rate and blood pressure. Clinical noninvasive graft evaluation includes measurement of ankle:brachial indices and duplex ultrasound scans with peak systolic velocity maps. Once the surveillance protocol was completed, the aforementioned index segment was identified using the referenced external landmarks or clips placed at the time of surgery. M-mode diameter measurements, PWV, and time averaged flow were obtained and calculated as for the intraoperative imaging study. If an index segment developed a lesion requiring reintervention or the graft developed an occlusion, the patient would be removed from the imaging substudy. None of these patients developed graft occlusion.

Calculations

Calculations for wall stiffness were based on modifications of the Moens-Koerteweg formula (Equation 1),(14) relating the elastic modulus of the vein graft to overall stiffness,

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where E = elastic modulus, ρ = density of blood (1.050 g/cm3), re =external radius, and ri = internal radius. External and internal radius and thereby wall thickness (Equation 2) were determined by MRI. The product of the elastic modulus and the thickness of the vein represents the overall stiffness and is equal to the quantity 2ρri(PWV)2 (Equation 3).

Volumetric flow, Q, was calculated from commercially available software, (Brachial Analyzer, Medical Imaging Applications, Iowa City, Iowa), by integrating the area under the velocity spectral waveform and dividing by the time required to arrive at a time-averaged velocity. Mean flow was calculated by multiplying the time-averaged velocity by the mean area of the lumen (as obtained from the index segment M-mode measurements).

Mean shear stress was calculated according to the Hagen-Poiseuille formula Tw = 4μQ/πri3, where Tw is shear stress in dynes/cm2, and mean volumetric flow is Q. The viscosity of blood, µ, is assumed to be 0.035 poise. Lumen radius, ri, is in cm.

Statistical methods

All values are represented as either mean ± SEM or median and interquartile range depending on their distribution. Comparisons of measures between individual time points between groups were made with the Student’s t- test or Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric one-way analysis of variance.

Relationships between remodeling metrics and inflammatory marker levels were evaluated either by dichotomizing the population according to the pre-operative plasma hsCRP levels,(9) or as a continuous variable with a natural logarithmic transformation. Log transformation was necessary to normalize its distribution. The Spearman rank correlation was used to compare hsCRP levels and relevant patient demographics.

Stepwise multivariable linear regression analysis (sw regress)(15) was conducted to determine the independent contribution of variables within traditional cardiovascular risk factors, inflammation, and hemodynamic categories to percent lumen remodeling from 0–1 month. The following covariates with P < 0.2 were included in the final model: age, diabetes, statin use, initial shear stress, CRP risk group (elevated hsCRP > 5mg/L or ≤ 5 mg/L), or ln hsCRP. CRP was entered into the model either as a categorical (high or low) or continuous variable and both β-coefficients are presented.(16) Colinearity between explanatory variables was assessed by calculating variance inflation factors. The β-coefficient and confidence intervals as well as the P values are presented. Values of P<0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed on Intercooled Stata 7.0, College Station, Texas.

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

Patient demographics and risk factors

The mean age for the study cohort was 68.8 ± 11.1 years. Of the 75 subjects, 42 (56.0%) were male, 58 (79.5%) were white, 38 (51.4%) had diabetes mellitus 44 (59.5%) had known history of coronary artery disease, 5 (6.7%) had end stage renal disease, and 58 (77.3%) were taking a HMG CoA reductase inhibitor (statin).

Surgical procedures

The indication for the revascularization was critical limb ischemia (CLI, defined as rest pain or tissue loss) in 44 subjects (58.7%), claudication in 26 (36.0%), and repair of popliteal aneurysm in 5 (6.7%). Autogenous conduits included single segment greater saphenous vein (GSV; reversed or non-reversed) in 57 (76.0%) cases, spliced greater saphenous or lesser saphenous vein in 6 (8.0%), and single segment arm vein in 4 (5.3%), and spliced arm vein in 8 (10.7%). Inflow sites included the common femoral artery in 50 (66.7%) patients, superficial femoral artery in 17 (22.7%), or popliteal artery in 8 (10.7%). Distal anastomoses were performed to the popliteal artery in 39 (52.0%), to the tibial artery in 24 (32.0%), and to a pedal artery 12 (16.0%) patients

Inflammation and remodeling

The median hsCRP for the entire cohort was 3.25 mg/L (inter-quartile range (IQR)1.38–14.20). The median concentration for SAA and fibrinogen was .94 mg/dL (IQR, .56–2.85) and 472.75 (IQR, 404.8–610.2), respectively. High sensitivity CRP correlated with the presence of diabetes (R=.29, P=.0007), chronic kidney disease classification (R=.34, P=.0001), and critical limb ischemia (R=.35, P<.00001). In contrast to hsCRP, neither fibrinogen or SAA were predictive of any imaging endpoints.

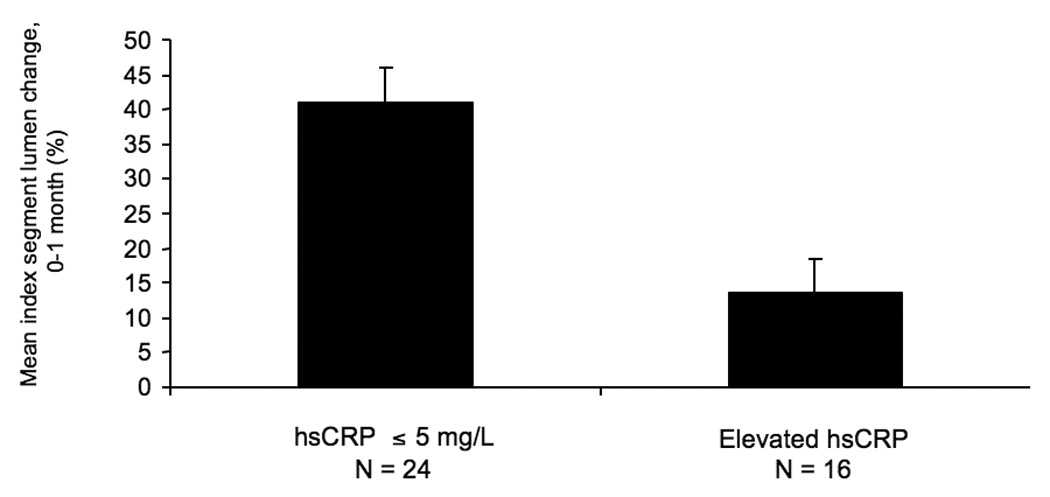

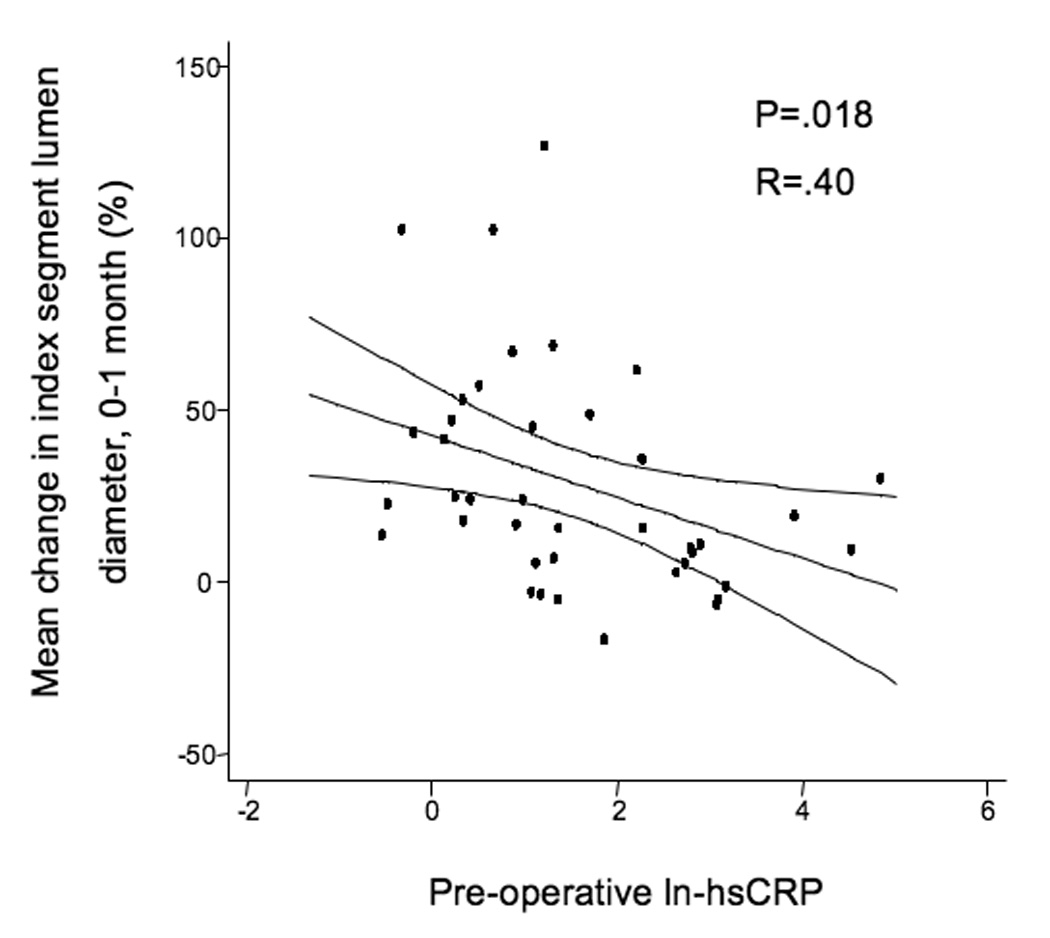

Vein graft morphometrics are summarized in Table 1. For the entire cohort, the mean lumen diameter of the index segment was 3.77 ± .14 mm at implantation and this increased to 4.67 ± .16 mm over the first month after surgery (p=.0001). The mean index segment lumen dilation (relative change) from the time of surgery to 1 month was 30.6 ± 32.3%, median 22.7% (IQ range 7.1–48.7%). There was no difference in the starting lumen diameters between patients in the low versus the elevated (>5 mg/L) hsCRP groups, 3.83 ± 1.43 mm v. 3.71 ± .82 mm. However, over the first postoperative month grafts in the low hsCRP group demonstrated greater lumen enlargement, 40.9 ± 34.4% (median 37.2%) vs. 13.5 ± 21.0% (median 9.49%; p=.0072, Figure 1a). Analyzing baseline hsCRP as a continuous risk variable, we observed a strong negative relationship between ln-hsCRP values and percent change in index segment lumen diameter over this period (R=.40, p=.010, Figure 1b).

Table 1.

Morphometrics of lower extremity vein grafts.

| A. High-resolution ultrasound imaging | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vein graft metrics | hsCRP ≤ 5 mg/L N=24 | Elevated hsCRP N=16 | P value |

| Lumen diameter (surgery), mm ± SEM | 3.83 ± 1.43 | 3.71 ± .82 | .696 |

| Lumen change (0–1 mo.), % ± SEM | 40.88 ± 7.02 | 13.54 ± 5.25 | .0072 |

| Shear stress (surgery), dynes/cm2 ± SEM | 27.63 ± 3.56 | 24.93 ± 3.00 | .566 |

| B. 2D magnetic resonance imaging | hsCRP ≤ 5 mg/L N=11 | Elevated hsCRP N=17 | P value |

| Wall thickness (1 mo.), mm ± SEM* | .75 ± .05 | .72 ± .04 | .685 |

| Elastic modulus (1 mo.), Mdynes/cm2 ± SEM* | 25.05 ± 6.51 | 50.44 ±12.22 | .069 |

P values are comparisons for high vs. low hsCRP groups.

N=28, Patients enrolled in an MRI substudy.

Figure 1.

A, Mean index segment lumen percent change dichotomizing the population by hsCRP levels (Elevated hsCRP > 5 mg/L), demonstrating less outward lumen remodeling in those subjects with elevated hsCRP levels, P=.0072. B, Linear regression of natural-logarithmic transformed hsCRP levels and percent lumen change from the time of surgery to 1-month, R=.371, P=.018.

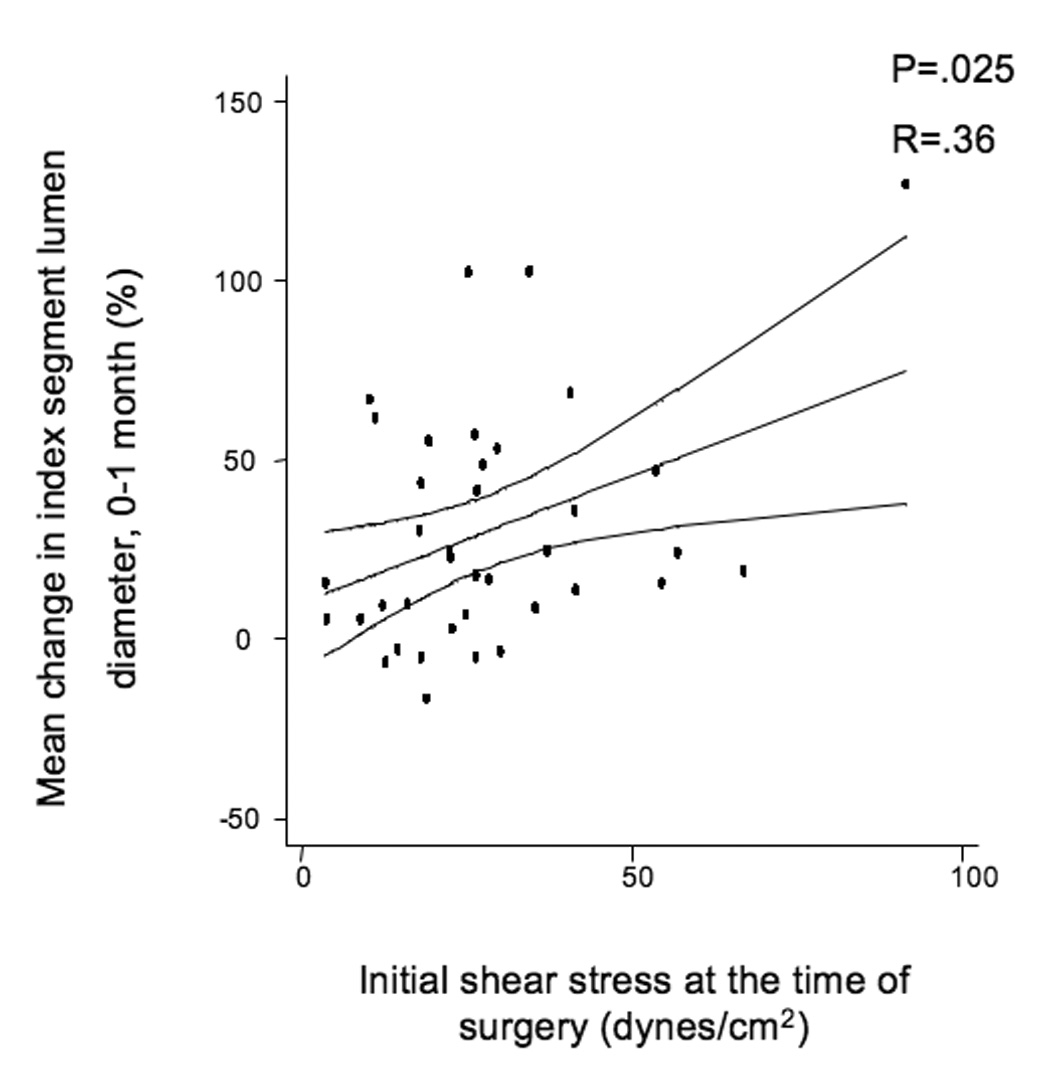

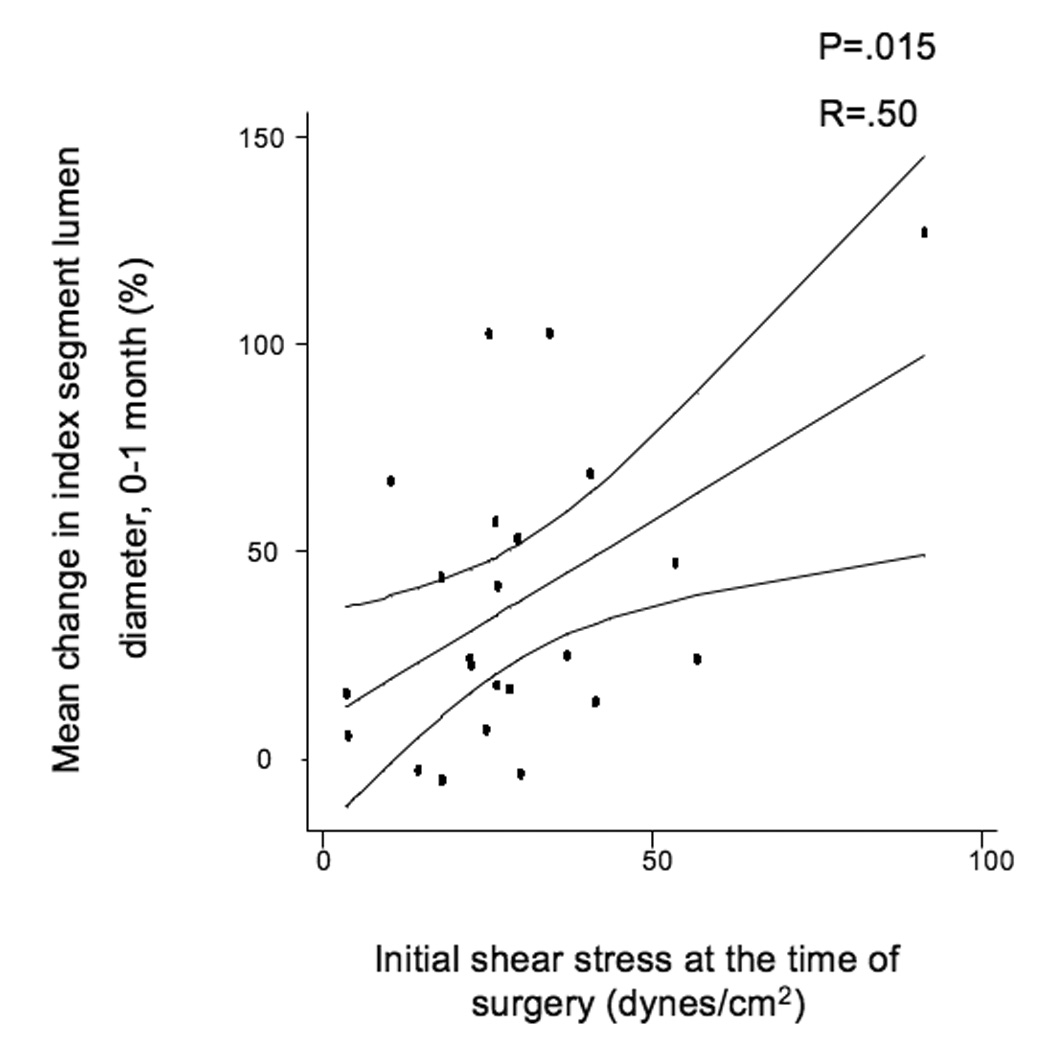

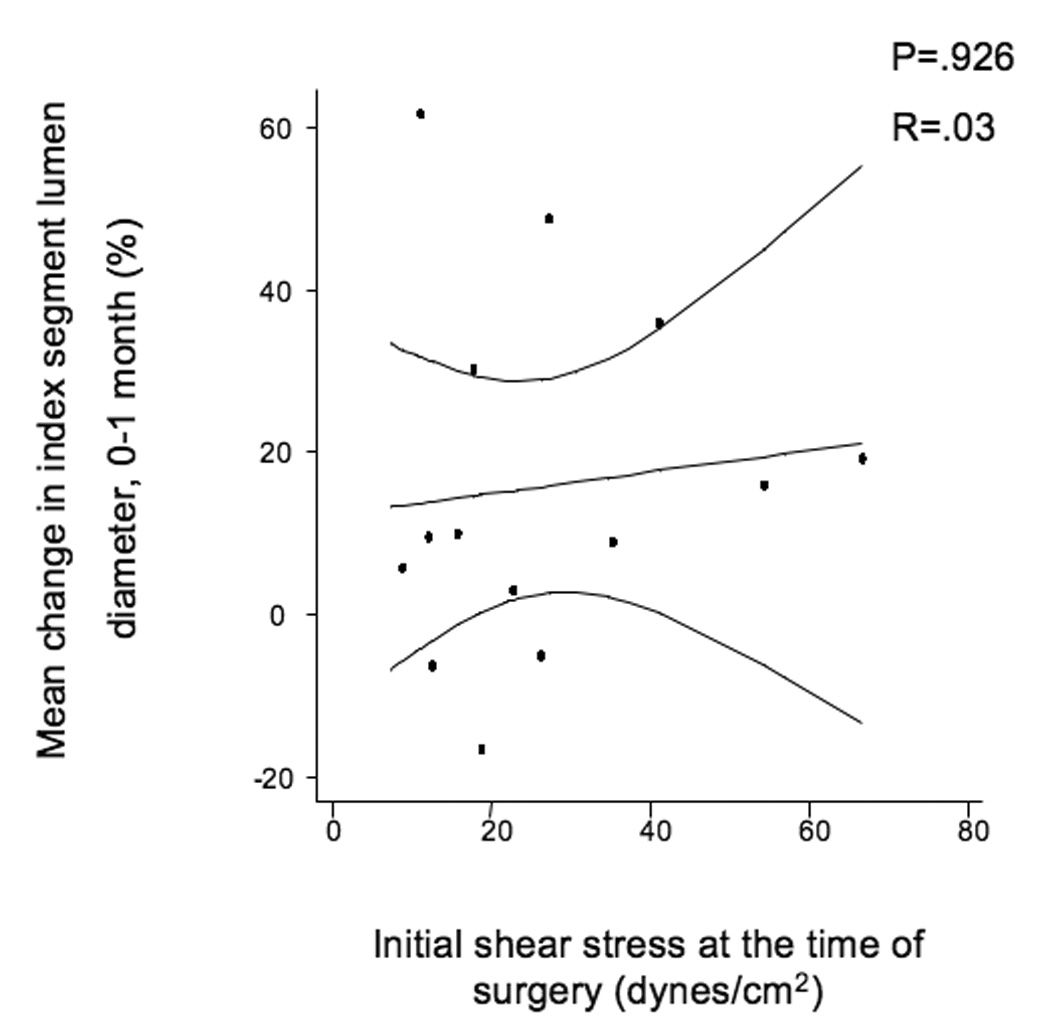

The mean initial shear stress for the entire cohort was 26.7 ± 1.9 dynes/cm2 and decreased to 20.5 ± 2.3 dynes/cm2 over the first month of implantation (P=.05). There were no significant differences in the initial shear stress between grafts in the elevated hsCRP population vs. those whose hsCRP is ≤ 5 mg/L. Over the first month of implantation, initial shear stress positively correlated with lumen dilation (R=.36, P=.025, Figure 2a). The association between initial shear stress and lumen dilation was relatively robust in subjects whose hsCRP was ≤ 5 mg/L (R=.50, P=.015, Figure 2b), but the association was not seen in patients with elevated hsCRP, (R=.03, P=.926, Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

A, Linear regression of the entire population comparing initial shear stress and mean index segment lumen dilation from 0–1 months, R=.387, P=.016. B, Subset of patients with hsCRP ≤ 5 mg/L, R=.5, P=.014, and C, Subset of patients with elevated hsCRP > 5 mg/L demonstrating loss of correlation between initial shear and lumen dilation, R=.103, P=.725.

A multivariable analysis was undertaken to assess variables contributing to early (0–1 month) vein graft remodeling (Table 2). Significant variables included age of the patient (P=.016), hsCRP risk group (P=.006), initial shear stress (P=.003), and current statin therapy (P=.037). These 4 variables account for approximately 45% of the variability in lumen dilation between surgery and one month. Of importance, conduit type (i.e. type or orientation of the vein), diabetes, or gender did not significantly add to the model. When modeling for final 1-month lumen diameter (Table 2), initial diameter, CRP risk group, and statin use were independently predictive.

Table 2.

Multivariable regression of factors influencing lumen diameter change, 0–1 month

| Factors influencing lumen remodeling, 0–1month | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | β (95 % CI) | P value |

| Elevated CRP | −29.7 (−50.5,−8.9) | .006 |

| lnCRP* | −10.8 (−18.2, −3.6) | .002 |

| statin | 23.1 (1.5, 44.2) | .037 |

| initial shear | .84 (.32, 1.4) | .003 |

| age | 1.17 (.23, 2.1) | .016 |

model created with either CRP as a dichotomized or natural log transformation variable

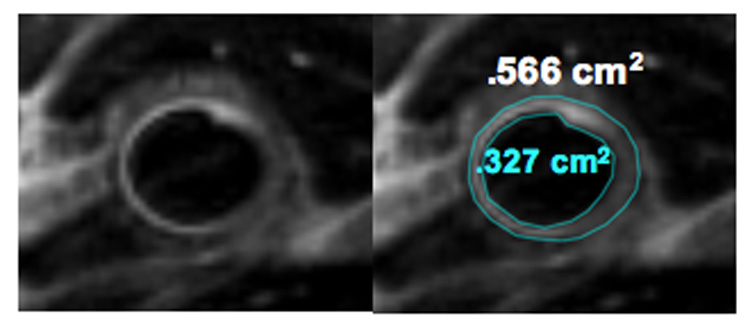

In a subset of patients (N=28) who agreed to participate in the MRI examinations, the vein graft wall thickness at 1-month post-implantation was assessed by T2WI (Figure 3). There was no difference in either total wall thickness or total wall area between high vs. low hsCRP risk groups (Table 1). However, there was a trend toward increased modulus of elasticity at 1 month in the high hsCRP group (50.44 ± 12.22 vs. 35.05 ± 6.51 Mdynes/cm2, P=.069), suggestive of greater conduit stiffness.

Figure 3.

A, Representative example of a high-resolution 2-D magnetic resonance T2 weighted image using black blood module of a human saphenous vein graft. B, The area inscribed by the two lines represents the T2 weighted wall area. The lumen area is .327 cm2 while the total vessel area is .566 cm2.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that in human lower extremity vein grafts, rapid lumen remodeling, which occurs within the first month after surgical implantation, is significantly modulated by systemic inflammation. Vein grafts in patients with baseline hsCRP values below 5 mg/L had significantly more early lumen dilation than those within the elevated hsCRP group, and there was a negative linear association between ln-hsCRP and early lumen remodeling. Furthermore, within the elevated hsCRP group, the positive correlation between shear stress and outward lumen remodeling was not seen, suggesting a level of dysfunction in either shear stress-signal transduction or vessel response. Moreover, in the multivariable regression model, baseline hsCRP was independently and negatively associated with early diameter change. Notably, the significance of the hsCRP variable was not attenuated with the inclusion of traditional cardiovascular risk factors into the model Conversely, utilization of statins, a class of agents known to reduce inflammation and improve endothelial function, was positively correlated with early lumen dilation.

Although preliminary, these results begin to integrate data from the domains of biomechanical, biochemical, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors to predict early changes in the vein graft lumen. A regression equation using four explanatory variables such as, lumen change= −10.9(ln hsCRP) + 23.1(presence of statin) + .85(initial shear stress) + 1.17(age) − 72.5, accounts for 45% of the variance seen in early lumen caliber change, which is a substantial improvement over any one factor alone. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an in vivo link between inflammation and early lumen remodeling in peripheral bypass grafts. However, of the three markers of inflammation that were measured, CRP, SAA, and fibrinogen, only CRP had a negative association with vein graft lumen changes.

Inflammation and endothelial function

Patients with PAD have a pro-inflammatory phenotype manifest as higher circulating levels of hsCRP in comparison to matched controls without PAD.(24) This is confirmed in the present report where the median hsCRP level was found to be 3.25 mg/L, which places this cohort in the highest risk category as defined for the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.(9, 25) Inflammation quantified by hsCRP has been shown to be associated in vivo with impaired brachial artery flow-mediated, endothelium-dependent, vasodilation in patients with PAD,(7) and blunted coronary endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease.(11) These observations suggest that inflammation impairs arterial endothelial function. In patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, circulating plasma CRP concentrations results in venous endothelial dysfunction and impaired acetylcholine-induced, endothelium-dependent relaxation of pre-implantation vein graft rings ex vivo, r = −.30, P = .02.(12) Further investigations are needed to characterize endothelial function in vein bypass grafts and to determine its relationship to the inflammatory response, structural remodeling, and clinical outcomes.

In vivo measurements of remodeling

Despite the clinical importance vein graft disease, there has been relatively little attention given to in vivo measurements of human vein graft remodeling. Most reports to date have involved intravascular ultrasound examinations of aorto-coronary bypass grafts which have the advantage of adequate echo-differentiation between the vein graft adventitia and surrounding pericardial tissue so that wall thickness measurements may be obtained.(26–29)Collectively, these reports demonstrate that the mechanisms of saphenous vein graft narrowing in the coronary circulation are often a combination of negative remodeling and intimal hyperplasia. While somewhat conflicting, these studies also demonstrate that saphenous vein grafts are capable of dilating to some degree in the face of an encroaching intimal hyperplastic lesion or atherosclerotic plaque. Consistent with these findings, Lau et al, using a non-contrast, ECG-gated, cardiac computed tomography scanner demonstrated a decrease in total vessel diameter of greater than 5 percent (defined as negative remodeling) in 62 percent of aorto-coronary vein grafts. Notably, none of these studies utilized serial imaging beginning at the time of implantation. Clearly, more effort is needed to accurately document remodeling characteristics of both coronary and lower extremity vein grafts and to determine the extent maladaptive remodeling contributes to vein graft failure.(30)

Even fewer studies have focused on the structural changes of peripheral vein grafts. Fillinger et. al. demonstrated a positive correlation between shear stress and percent change in lumen caliber over the first year of implantation.(4) Leotta et. al. observed negative lumen remodeling by 3D lumen reconstructions of lower extremity saphenous vein graft revisions (patch angioplasties). On average, there was a loss of lumen cross sectional area by 31% over a 35-week period. However, the average post-operative lumen diameter after patching was 7.5 mm, which was considerably larger than the un-revised vein grafts presented in our current report.(31)Neither of these studies were able to measure the vein graft wall, illustrating the technical difficulty in resolving the structure.

Limitations

Our characterization of vein graft remodeling currently focuses on the combined use of advanced noninvasive imaging tools, in particular the optimization of high-resolution MRI, to attain an accurate assessment of wall thickness which has eluded us with conventional ultrasound technology. This will allow temporal assessment of wall structural and total vessel area as opposed to changes in lumen diameter. Limitations related to assumptions of the Moens-Korteweg equation, and therefore accuracy of the elastic modulus and stiffness calculations have been detailed elsewhere.(1, 13) Briefly, the Moens-Korteweg equation assumes a thin-walled, non-tapered tube containing an ideal non-compressible liquid. The PWV is an integrated value over the entire vein graft and fails to account for heterogeneity in viscoelastic properties within the vein graft which may predispose it to local failure at susceptible sites. Despite these limitations, PWV is used extensively in the literature and is one of the most accurate non-invasive methodologies to assess stiffness.

While this study is not sufficiently powered to detect differences in patency between vein grafts that do and do not undergo favorable lumen remodeling, it suggests that inflammation has a detrimental effect on the vein’s ability to function as an arterial substitute which may ultimately impact patency. Finally, limited sample size and missing observations may introduce bias and confound our results. Post-operative wound complications accounted for the majority of missing ultrasound data. Other reasons included 1 patient who died, 2 patients experienced early graft occlusion, and the remainder either had scans that were un-interpretable, returned outside of their one-month study window (2-weeks), or unavailability of study staff. Of the many methods to handle missing values including last observation carried forward, imputation (mean or regression), or list-wise omission (32), we favored the latter as there were no discernable differences in terms of cardiovascular risk factors and levels of inflammation between those patients with missing values and those with all observations present.

Conclusions

This study confirms that lower extremity vein grafts undergo significant lumen remodeling within the first month of implantation, and that shear stress is strongly correlated with early changes in lumen caliber . We now report that baseline systemic inflammation, as reflected by hsCRP, appears to be an important modifier of this early hemodynamic response. This finding may have important clinical and therapeutic implications. Further effort is needed to characterize the temporal and spatial remodeling of the lumen and wall of peripheral vein grafts and to determine early remodeling signatures of healthy versus diseased grafts.

Acknowledgments

Supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL75771 to M.S.C., C.D.O., and F.J.R.), the Clinical Investigator Training Program, Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology (C.D.O.), NIBIB (K23-882) and the Whitaker Foundation (F.J.R.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competition of interest: none

References

- 1.Owens CD, Wake N, Jacot JG, et al. Early biomechanical changes in lower extremity vein grafts--distinct temporal phases of remodeling and wall stiffness. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(4):740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox JL, Chiasson DA, Gotlieb AI. Stranger in a strange land: the pathogenesis of saphenous vein graft stenosis with emphasis on structural and functional differences between veins and arteries. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1991;34(1):45–68. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(91)90019-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies MG, Hagen PO. Pathophysiology of vein graft failure: a review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1995;9(1):7–18. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(05)80218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillinger MF, Cronenwett JL, Besso S, Walsh DB, Zwolak RM. Vein adaptation to the hemodynamic environment of infrainguinal grafts. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19(6):970–978. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70208-x. discussion 978–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majewski W, Laciak M, Staniszewski R, Gorny A, Mackiewicz A. C-reactive protein and alpha 1-acid glycoprotein in monitoring of patients with acute arterial occlusion. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1991;5(6):641–645. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80899-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barani J, Nilsson JA, Mattiasson I, Lindblad B, Gottsater A. Inflammatory mediators are associated with 1-year mortality in critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brevetti G, Silvestro A, Di Giacomo S, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in peripheral arterial disease is related to increase in plasma markers of inflammation and severity of peripheral circulatory impairment but not to classic risk factors and atherosclerotic burden. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(2):374–379. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matzke S, Biancari F, Ihlberg L, et al. Increased preoperative c-reactive protein level as a prognostic factor for postoperative amputation after femoropopliteal bypass surgery for CLI. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2001;90(1):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owens CD, Ridker PM, Belkin M, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels are associated with postoperative events in patients undergoing lower extremity vein bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.048. discussion 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bisoendial RJ, Kastelein JJ, Peters SL, et al. Effects of CRP infusion on endothelial function and coagulation in normocholesterolemic and hypercholesterolemic subjects. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(4):952–960. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P600014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichtlscherer S, Rosenberger G, Walter DH, Breuer S, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and impaired endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000;102(9):1000–1006. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momin A, Melikian N, Wheatcroft SB, et al. The association between saphenous vein endothelial function, systemic inflammation, and statin therapy in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacot JG, Abdullah I, Belkin M, et al. Early adaptation of human lower extremity vein grafts: wall stiffness changes accompany geometric remodeling. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(3):547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols W, O'Rourke MF. McDonald's Blood Flow in Arteries. Fifth ed. New York: Hodder Arnold; 2005. Properties of the Arterial Wall: Theory; pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabe-Hesketh S. A Handbook of Statistical Analysis using Stata. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariable Statistics. 2 ed. Cambridge, MA: Harper & Row; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray CD. The Physiological Principle of Minimum Work: I. The Vascular System and the Cost of Blood Volume. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1926;12(3):207–214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.12.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milroy CM, Scott DJ, Beard JD, Horrocks M, Bradfield JW. Histological appearances of the long saphenous vein. J Pathol. 1989;159(4):311–316. doi: 10.1002/path.1711590408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Mey JG, Vanhoutte PM. Heterogeneous behavior of the canine arterial and venous wall. Importance of the endothelium. Circ Res. 1982;51(4):439–447. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luscher TF, Diederich D, Siebenmann R, et al. Difference between endothelium-dependent relaxation in arterial and in venous coronary bypass grafts. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(8):462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808253190802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu ZG, Ge ZD, He GW. Difference in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated hyperpolarization and nitric oxide release between human internal mammary artery and saphenous vein. Circulation. 2000;102 (19 Suppl 3):III296–III301. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishioka H, Kitamura S, Kameda Y, Taniguchi S, Kawata T, Mizuguchi K. Difference in acetylcholine-induced nitric oxide release of arterial and venous grafts in patients after coronary bypass operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116(3):454–459. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaikhouni A, Crawford FA, Kochel PJ, Olanoff LS, Halushka PV. Human internal mammary artery produces more prostacyclin than saphenous vein. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;92(1):88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckman JA, Preis O, Ridker PM, Gerhard-Herman M. Comparison of usefulness of inflammatory markers in patients with versus without peripheral arterial disease in predicting adverse cardiovascular outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke, and death) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(10):1374–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107(3):499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaneda H, Terashima M, Takahashi T, et al. Mechanisms of lumen narrowing of saphenous vein bypass grafts 12 months after implantation: an intravascular ultrasound study. Am Heart J. 2006;151(3):726–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishioka T, Luo H, Berglund H, et al. Absence of focal compensatory enlargement or constriction in diseased human coronary saphenous vein bypass grafts. An intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 1996;93(4):683–690. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong MK, Mintz GS, Hong MK, et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of the presence of vascular remodeling in diseased human saphenous vein bypass grafts. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(9):992–998. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canos DA, Mintz GS, Berzingi CO, et al. Clinical, angiographic, and intravascular ultrasound characteristics of early saphenous vein graft failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau GT, Ridley LJ, Bannon PG, et al. Lumen loss in the first year in saphenous vein grafts is predominantly a result of negative remodeling of the whole vessel rather than a result of changes in wall thickness. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I435–I440. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leotta DF, Primozich JF, Beach KW, Bergelin RO, Zierler RE, Strandness DE., Jr Remodeling in peripheral vein graft revisions: serial study with three-dimensional ultrasound imaging. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(4):798–807. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little RJA. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]