Abstract

Glaucoma, cataracts, and proximal renal tubular acidosis are diseases

caused by point mutations in the human electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate

cotransporter (NBCe1/SLC4A4)

(1,

2). One such mutation, R298S,

is located in the cytoplasmic N-terminal domain of NBCe1 and has only moderate

(75%) function. As SLC transporters have high similarity in their membrane and

N-terminal primary sequences, we homology-modeled NBCe1 onto the crystal

structure coordinates of Band 3(AE1)

(3). Arg-298 is predicted to be

located in a solvent-inaccessible subsurface pocket and to associate with

Glu-91 or Glu-295 via H-bonding and charge-charge interactions. We perturbed

these putative interactions between Glu-91 and Arg-298 by site-directed

mutagenesis and used expression in Xenopus oocyte to test our

structural model. Mutagenesis of either residue resulted in reduced transport

function. Function was “repaired” by charge reversal (E91R/R298E),

implying that these two residues are interchangeable and interdependent. These

results contrast the current understanding of the AE1 N terminus as

protein-binding sites and propose that hkNBCe1 (and other SLC4) cytoplasmic N

termini play roles in controlling  permeation.

permeation.

Regulating and maintaining acid-base homeostasis is critical for normal

cell, tissue, and systemic function. Transporters in several transporter

families are involved in this multilevel pH regulation: Slc4 (bicarbonate

transporters), Slc94

(Na+-H+ exchangers), Slc16

(H+/monocarboxylate cotransporters), and Slc26 (anion and

bicarbonate transporters). Na+-H+ exchangers

(NHEs,5 Slc9 proteins)

play important pH regulatory roles in many cells and tissues. Nevertheless, in

many cells,  transporters carry

even more acid-base equivalents than NHEs and are often more active in

CO2/

transporters carry

even more acid-base equivalents than NHEs and are often more active in

CO2/ environments

(normal cellular and tissue buffering system).

environments

(normal cellular and tissue buffering system).

The importance of  transporters

has been further highlighted by the existence of severe pathogenic mutations

(reviewed in Ref. 4). Igarashi

et al. (1) described

the first patients with mutations in the NBCe1 (SLC4A4) gene and protein,

R298S and R510H. Since then, several additional patients have been identified

with recessive NBCe1 mutations (for review, see Ref.

5). These patients with

mutations in the NBCe1 coding sequence have permanent proximal renal tubular

acidosis (pRTA type II, i.e. pHblood ∼7.05,

[

transporters

has been further highlighted by the existence of severe pathogenic mutations

(reviewed in Ref. 4). Igarashi

et al. (1) described

the first patients with mutations in the NBCe1 (SLC4A4) gene and protein,

R298S and R510H. Since then, several additional patients have been identified

with recessive NBCe1 mutations (for review, see Ref.

5). These patients with

mutations in the NBCe1 coding sequence have permanent proximal renal tubular

acidosis (pRTA type II, i.e. pHblood ∼7.05,

[ ] = 3-11 mm; normal

blood pH = 7.35-7.45, [

] = 3-11 mm; normal

blood pH = 7.35-7.45, [ ] = 23-25

mm) with early onset, bilateral glaucoma, bilateral cataracts, and

band keratopathy, yet without obvious intestinal or pancreatic defects

(1).

] = 23-25

mm) with early onset, bilateral glaucoma, bilateral cataracts, and

band keratopathy, yet without obvious intestinal or pancreatic defects

(1).

In the renal proximal tubule, the major apical step of bicarbonate

absorption is acid secretion to the forming urine by the NHE3,

Na+-H+ exchanger

(6). The basolateral step of

proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption appears to rely exclusively on NBCe1

function (Na+/n cotransport). For example, the NHE3 knock-out mice have only a slight

metabolic acidosis (blood pH ∼7.27 and

[

cotransport). For example, the NHE3 knock-out mice have only a slight

metabolic acidosis (blood pH ∼7.27 and

[ ] = 21 mm)

(7,

8), indicating that NHE3 is not

the rate-limiting step in transepithelial bicarbonate absorption. However,

both humans with NBCe1 mutations

(1,

9-13)

and the NBCe1 knock-out mice

(14) have significant

metabolic acidosis (humans, see above; NBCe1-/-, blood pH 6.86,

[

] = 21 mm)

(7,

8), indicating that NHE3 is not

the rate-limiting step in transepithelial bicarbonate absorption. However,

both humans with NBCe1 mutations

(1,

9-13)

and the NBCe1 knock-out mice

(14) have significant

metabolic acidosis (humans, see above; NBCe1-/-, blood pH 6.86,

[ ] = 5.3 mm). Taken

together, these data indicate that the basolateral exit of

] = 5.3 mm). Taken

together, these data indicate that the basolateral exit of

via NBCe1 rather than apical

H+ secretion via NHE3 is the dominant and rate-limiting step in

kidney bicarbonate absorption. This loss-of-function/reduced-function

phenotype also indicates that NBCe1 is the only

via NBCe1 rather than apical

H+ secretion via NHE3 is the dominant and rate-limiting step in

kidney bicarbonate absorption. This loss-of-function/reduced-function

phenotype also indicates that NBCe1 is the only

absorption pathway in the renal

proximal tubule and that NBCe1 plays a key role for maintaining ocular

pressure and corneal clarity.

absorption pathway in the renal

proximal tubule and that NBCe1 plays a key role for maintaining ocular

pressure and corneal clarity.

Loss of NBCe1 function may result from (a) aberrant protein

processing or folding (12,

13,

15), (b) protein

truncation (10), or

(c) misfunction of the NBCe1 protein

(1,

9,

16). For example, S427L in

transmembrane span 1 is a biophysical (functional) mutation resulting in

unidirectional transport at 10% of wild-type

(9), whereas L522P in

transmembrane span 5 is a protein trafficking problem

(12). R298S-NBCe1 was

originally reported as having ∼50% wild-type function

(1), i.e. also a

biophysical mutation, but was more recently reported as a protein trafficking

problem (1,

9,

16). A transmembrane

topography of the human NBCe1-B has been proposed based on glycosylation

studies (17). None of the

proposed structural models dispute the Arg-298 location, i.e.

residing in the center of the cytoplasmic N terminus of NBCe1 and not

obviously associated with the transmembrane domain. How then does this

placement translate to malfunction of the R298S-NBCe1 protein? Does this imply

that  permeation and/or affinity is

associated with the cytoplasmic N terminus? Transmembrane domains of membrane

proteins are generally thought to control ion permeability across membranes.

However, knowing the sequence and predicted structural location (based on

linear sequence) is not always the best predictor of structure.

permeation and/or affinity is

associated with the cytoplasmic N terminus? Transmembrane domains of membrane

proteins are generally thought to control ion permeability across membranes.

However, knowing the sequence and predicted structural location (based on

linear sequence) is not always the best predictor of structure.

NBCe1 is a member of the  transporter gene family that includes Band 3 (AE1/SLC4A1). All SLC4 members

have >35% sequence identity, particularly in predicted membrane spans.

Although crystals were recently obtained for this region of NBCe1, only gross

topology rather than amino acid assignment was reported

(18). We hypothesized that we

could gain insights into NBCe1 structure and function by mapping its amino

acid sequence onto the AE1 N-terminal structure

(3). This structural prediction

indicated that Arg-298, a conserved residue in SLC4 proteins, is located in a

solvent-inaccessible pocket. The model further predicted that Arg-298 has

charge interactions with Glu-295 and Glu-91, both of which are also conserved

in SLC4

transporter gene family that includes Band 3 (AE1/SLC4A1). All SLC4 members

have >35% sequence identity, particularly in predicted membrane spans.

Although crystals were recently obtained for this region of NBCe1, only gross

topology rather than amino acid assignment was reported

(18). We hypothesized that we

could gain insights into NBCe1 structure and function by mapping its amino

acid sequence onto the AE1 N-terminal structure

(3). This structural prediction

indicated that Arg-298, a conserved residue in SLC4 proteins, is located in a

solvent-inaccessible pocket. The model further predicted that Arg-298 has

charge interactions with Glu-295 and Glu-91, both of which are also conserved

in SLC4  transporter proteins.

transporter proteins.

Are these sequence alignments coincidence, or is the Band 3 N-terminal

structure a good predictor of NBCe1 N-terminal structure? In this study, we

use point mutations to perturb the charge interaction between Glu-91 and

Arg-298. Our results indicate that Arg-298, Glu-91, and their interaction are

crucial for the NBCe1 N-terminal structure as well as the normal physiological

function of NBCe1. Thus, this structural model and the following experiments

elucidate, on the molecular level, “why” R298S causes a proximal

RTA with bilateral cataracts and glaucoma. These results suggest that the

NBCe1 cytoplasmic N terminus dictates/controls

permeation or affinity. These

results also challenge the general belief that the N terminus of membrane

proteins, like NBCe1, is not directly involved with substrate transport but

rather is merely serving as a protein anchor, as is believed for the AE1 N

terminus (3).

permeation or affinity. These

results also challenge the general belief that the N terminus of membrane

proteins, like NBCe1, is not directly involved with substrate transport but

rather is merely serving as a protein anchor, as is believed for the AE1 N

terminus (3).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

NBCe1 N Terminus Structure Modeling—A pair-wise alignment of sequences of human kidney NBCe1 (residues 62-371) and AE1 (residues 55-356) accession codes M27819 was prepared in the Swiss-PdbViewer (SPDBV (19)) or externally with SIM and the Blosum62 algorithm (20). These nearly identical alignments, when submitted together with the coordinates for AE1 (Protein Data Bank accession code 1HYN) to the Swiss-model server (21), did not yield an initial model due to failure of identifying appropriate loops. Despite a 36.5% overall sequence identity between these proteins, there is a region among NBCe1 (residues 113-174) and AE1 (residues 165-218) that does not show much sequence similarity, reducing the threading reliability in this area. Thus, multiple sequence alignments with the ClustalW algorithms (DNASTAR) were made to identify boundaries of conserved and variable sequence regions within and across homologous domains of the Slc4 protein families. The resulting manually optimized binary alignment between NBCe1 and AE1 served as input for Swiss model. The returned initial model, based on the four individual copies of the domain in HYN, was briefly minimized. Side chain conformations were subsequently optimized with SCWRL3 (22) and minimized to yield the present model structure (Fig. 2B). The NBCe1 model was then analyzed with the programs VADAR, Procheck, and WHAT IF (23-25) (Fig. 2,C-E).

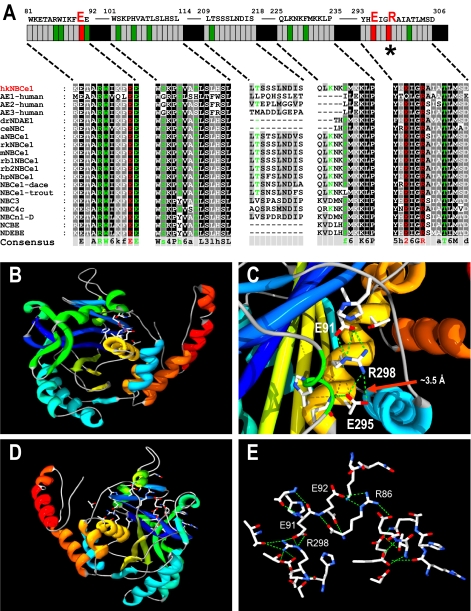

FIGURE 2.

Structural model of the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain (62-313) of hkNBCe1. A, sequence alignment of hkNBCe1 amino acid sequences 81-92, 101-114, 209-218, 225-235, and 293-306 with corresponding regions of other SLC4 bicarbonate transporter proteins. The intensity of the shading corresponds to the consensus level of the conserved residues in the gene family. The asterisk indicates missense human mutation R298S. Residues marked as green are residues within 4 Å from Glu-91, Arg-295, and Arg-298 (high-lighted in red) and highly likely to have charge interactions with these three residues. B, ribbon diagram structure of hkNBCe1 amino acid sequence 62-313 mapped onto the corresponding region of the Band 3 (human AE1) crystal structure (PDB number 1HYN) of Low and co-workers (3). The blue to red progressive color scheme denotes secondary structure succession from N terminus toward C terminus. C, human missense mutation R298S is located in the solvent-inaccessible pocket. Highlighted are residues Glu-91 and Glu-295 about 3.5 Å from the Arg-298 side chains putatively forming H-bond (green) with Arg-298. Side-chain charges of the three residues are color-coded to negative (red) and positive (blue). D, chain of polar residues creating a polar channel in the domain core. E, close up view on the hydrogen bond network of polar residues. The NCBI/GenBank™ accession numbers for these sequences are hkNBCe1 (human kidney form electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; AF007216), hAE1-hAE3 (human anion exchanger 1-3; M27819, U62531, and U05596), drNDAE1 (Drosophila sodium-dependent anion exchanger 1; AF047468), ceNBC (Caenorhabditis elegans Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter; AF004926), aNBCe1 (Ambystoma electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; AF001958), rkNBCe1 (rat kidney electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; NM_053424), mNBCe1 (murine electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; AF141934), rb1NBCe1 and -2 (rat brain electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1 and 2; AF124441 and AF254802), hpNBCe1 (human pancreas form electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; AF053753), NBCe1-dace (Osorezan dace electrogenic Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; AB055467), NBCe1-trout (rainbow trout Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1; AF434166), NBC3 (human Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 3; AF069512), NBC4c (human Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 4; AF293337), NBCn1-D (rat electroneutral Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1-D, NM_058211), NCBE (Na+-Cl-/bicarbonate exchanger; AB040457), NDCBE(Na+-driven chloride/bicarbonate exchanger; AY151155).

Cloning and Mutations—The human kidney NBCe1 (hkNBCe1) clone in a Xenopus expression plasmid was previously described (9). hkNBCe1 mutations were generated using QuikChange (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and sequenced for verification (W. M. Keck Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, New Haven, CT). Linearized cDNA was used to make capped cRNA with the SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) as described previously (26).

A hemagglutinin affinity tag “HA tag” was engineered into the extracellular loop of hkNBCe1 at the Ser-596 → Ser-610 region with a linker (SNDTTLAP-DYPYDVPDYAG-EYLPTMS) as that described in McAlear et al. (27). This HA tag insertion does not affect NBCe1 activity or sensitivity to stil-benes (27). Using an anti-HA 1° antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated 2° antibody with a chemiluminescent substrate, we were able to quantify surface expression of hkNBCe1 clones in a luminometer. The single-oocyte chemiluminescence technique utilizes enzyme amplification of chemiluminescence substrate to quantify a HA-tagged protein expressed at the cell surface (28, 29). This technique has a linear relationship between surface expression detected by single-oocyte chemiluminescence and functional activity of the K+ channel, ROMK (Kir 1.1), as reported by Yoo et al. (30).

Oocyte Experimental Solutions—The

CO2/ -free ND96 contained

96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2,

1.8 mm CaCl2, and 5 mm HEPES. In

CO2/

-free ND96 contained

96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2,

1.8 mm CaCl2, and 5 mm HEPES. In

CO2/ -equilibrated

solutions, 33 mm NaHCO3 replaced 33 mm NaCl;

all CO2/

-equilibrated

solutions, 33 mm NaHCO3 replaced 33 mm NaCl;

all CO2/ solutions are

5% CO2, 33 mm

solutions are

5% CO2, 33 mm

(pH 7.5). In 0-Na+

solutions, choline replaced Na+. All the solutions used in the

experiments were adjusted to pH 7.5 and 195-200 mosm.

(pH 7.5). In 0-Na+

solutions, choline replaced Na+. All the solutions used in the

experiments were adjusted to pH 7.5 and 195-200 mosm.

Oocyte Electrophysiology—50 nL of water (control) or RNA solution (25 ng of hkNBCe1 or mutant cRNA) was injected into stage V/VI Xenopus oocytes. Voltage electrodes, made from fiber-capillary borosilicate and filled with 3 m KCl, had resistances of 1-10 megaohms (31). Ion-selective electrodes were pulled similarly and silanized with bis-(dimethylamino)-dimethylsilane (Fluka Chemical Corp., Ronkonkoma, NY). pH electrode tips were filled with hydrogen ionophore 1 mixture B (Fluka) and back-filled with phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Electrodes were connected to a high-impedance electrometer (WPI-FD223 for intracellular pH (pHi) and Vm experiments), and digitized output data (filtered at 10Hz) were acquired by PCLAMP software sampling at 0.5 Hz. All ion-selective microelectrodes had slopes of -54 to -57 mV/decade ion concentration (or activity). pH electrodes were calibrated at pH 6.0 and 8.0. For voltage-clamp experiments, electrodes were filled with 3 m KCl/agar and 3 m KCl and had resistances of 0.2-0.5 megaohms. Oocytes were clamped at -60 mV, and current was constantly monitored and recorded at 10 Hz (Warner Inst. Co., Oocyte Clamp OC-725C). Voltage steps pulses (75 ms) were executed from -160 to +60 mV in 20 mV steps; the resulting I-V traces were filtered at 2 kHz (8 pole Bessel filter) and sampled at 10 kHz. Data were acquired and analyzed using Pulse and PulseFit (HEKA Instruments, Germany).

Oocyte Surface Protein Expression—Oocyte labeling was performed at 4 °C. Oocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in ND96 for 15 min, washed and incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin-ND96 blocking solution for 30 min. Oocytes were labeled with a 1° antibody (1:200 dilution, monoclonal rat-α-HA 1° antibody (Roche Applied Science)) for 60 min, and then with a 2° antibody (1:2000 dilution, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-α-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories)) for 30 min in 1% bovine serum albumin-ND96 blocking solution. Labeled oocytes were washed several times and incubated in ND96 for 10 min before exposure to 50 μl of the premixed SuperSignal ELISA Femto substrate solution (Pierce) at room temperature. Chemiluminescent was measured from single oocytes in a microcentrifuge tube using a TD-20/20n luminometer (Turner BioSystems). Measurements were taken at 30 s after initiation of the luminescent reaction.

Statistical Analysis—Values, quantity of ion activities, or

currents are indicated as the mean ± S.E. The total apparent buffering

power (βT, see Table

1) is defined as the change in pHi before and

after application of

CO2/ (once steady state

is reached) divided by the pHi change elicited from the

same solution changes, i.e. βT

=Δ[

(once steady state

is reached) divided by the pHi change elicited from the

same solution changes, i.e. βT

=Δ[ ]steady

state/ΔpHi(9).

Statistical analysis was performed with a one-tailed Student's t test

to have a significant difference at p < 0.05 or less.

]steady

state/ΔpHi(9).

Statistical analysis was performed with a one-tailed Student's t test

to have a significant difference at p < 0.05 or less.

TABLE 1.

transport and elicited

currents from WT- and mutant NBCe1

transport and elicited

currents from WT- and mutant NBCe1

Calculations are as indicated under “Experimental Procedures” and as previously described (9). The value for ΔβhkNBCe1 is βT(hkNBCe1) - βT(water). These data were collected using the three-electrode experiments (see “Experimental Procedures”) to voltage-clamped oocytes at −60 mV while also measuring pHi. Im is membrane current. For pHi and ΔpHi values, there are actually four significant digits, although three are shown for readability. Italicized columns are the average value for each parameter for each clone or control. % values for each clone are normalized to the wild-type hkNBCe1 (taken as 100%). Note that values should be compared with both WT-NBCel as well as the water-control because the water-control versus the WT-NBCe1 percentage increases and decreases depending on the parameter.

| Units | Water | hkNBCe1 | R298S | E91R | R298E | E91R-R298E | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Initial pHi | 7.42 | 0.11 | 6 | 100 | 7.44 | 0.02 | 19 | 7.48 | 0.02 | 7 | 101 | 7.35 | 0.04 | 9 | 99 | 7.40 | 0.03 | 9 | 100 | 7.50 | 0.01 | 7 | 101 | |

| Final pHi | 7.00 | 0.08 | 6 | 96 | 7.27 | 0.02 | 19 | 7.23 | 0.04 | 7 | 99 | 6.92 | 0.03 | 9 | 95 | 7.11 | 0.03 | 9 | 98 | 7.26 | 0.02 | 7 | 100 | |

| ΔpHi | −0.43 | 0.05 | 6 | 243 | −0.18 | 0.02 | 19 | −0.25 | 0.04 | 7 | 145 | −0.43 | 0.03 | 9 | 246 | −0.29 | 0.02 | 9 | 165 | −0.23 | 0.02 | 7 | 134 | |

| ΔpHi (0Na+-CO2) | −0.03 | 0.01 | 6 | 14 | −0.20 | 0.02 | 19 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 7 | 55 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 9 | 6 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 9 | 43 | −0.15 | 0.01 | 7 | 74 | |

| mm | [HCO3−]i | 9.45 | 1.63 | 6 | 57 | 16.55 | 0.84 | 19 | 15.05 | 1.28 | 7 | 91 | 7.31 | 0.49 | 9 | 44 | 11.55 | 0.73 | 9 | 70 | 16.01 | 0.71 | 7 | 97 |

| mm/pH unit | Apparent βT | 22.88 | 4.17 | 6 | 17 | 136.96 | 25.01 | 19 | 71.06 | 14.41 | 7 | 52 | 17.73 | 2.01 | 9 | 13 | 40.82 | 3.51 | 9 | 30 | 71.55 | 8.02 | 7 | 52 |

| mm/pH unit | ΔβNBCe1 | 114.08 | 48.18 | −5.15 | 17.94 | 48.66 | ||||||||||||||||||

| dpHi/dt (×10−5 pH unit/s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dpHi/dt | CO2/HCO3− | −299.33 | 46.17 | 6 | 179 | −167.16 | 21.29 | 19 | −297.86 | 56.40 | 7 | 178 | −373.67 | 42.94 | 9 | 224 | −286.89 | 36.11 | 9 | 172 | −233.57 | 28.57 | 7 | 140 |

| dpHi/dt | 0Na+-CO2 | 17.83 | 5.42 | 6 | 8 | 225.47 | 24.10 | 19 | 131.57 | 10.38 | 7 | 58 | 56.22 | 8.00 | 9 | 25 | 129.89 | 23.50 | 9 | 58 | 138.00 | 10.51 | 7 | 61 |

| dpHi/dt | ND96 wash | 140.17 | 24.37 | 6 | 173 | 80.89 | 30.18 | 19 | 164.86 | 23.72 | 7 | 204 | 202.00 | 18.62 | 9 | 250 | 138.78 | 22.25 | 9 | 172 | 134.86 | 14.12 | 7 | 167 |

| Im(nA)@ −60 mV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| nA | Basal | 17.36 | 39.27 | 6 | 24 | −73.63 | 11.01 | 19 | −36.51 | 8.73 | 7 | 50 | −37.01 | 13.58 | 9 | 50 | −48.56 | 24.45 | 9 | 66 | −82.11 | 19.86 | 7 | 112 |

| nA | CO2/HCO3− | 1.63 | 10.68 | 6 | 0 | 764.37 | 50.97 | 19 | 568.85 | 43.23 | 7 | 74 | 38.66 | 5.80 | 9 | 5 | 543.44 | 64.15 | 9 | 71 | 757.33 | 63.27 | 7 | 99 |

| nA | 0-Na+-CO2 | −10.58 | 9.56 | 6 | 2 | −688.99 | 66.14 | 19 | −506.42 | 60.94 | 7 | 74 | −36.04 | 7.72 | 9 | 5 | −495.42 | 69.52 | 9 | 72 | −666.42 | 40.04 | 7 | 97 |

| nA | Final ND96 | −49.80 | 39.00 | 5 | 24 | −208.29 | 25.61 | 19 | −158.34 | 11.64 | 7 | 76 | −42.32 | 14.21 | 9 | 20 | −487.02 | 303.23 | 9 | 234 | −223.22 | 61.11 | 7 | 107 |

RESULTS

The addition of CO2 to a solution, results in H+

formation because CO2 + H2O ↔ (slow)

H2CO3 ↔ (fast) H+ +

. When CO2 crosses to

the inside of a Xenopus oocyte, this H+ formation results

in a cellular acidification (decrease of pHi). The

addition of 5% CO2, 33 mm

. When CO2 crosses to

the inside of a Xenopus oocyte, this H+ formation results

in a cellular acidification (decrease of pHi). The

addition of 5% CO2, 33 mm

, pH 7.5

(CO2/

, pH 7.5

(CO2/ ) to the bath

solution resulted in a fast acidification in a water-injected control oocyte

(Fig. 1A). When

hkNBCe1 was expressed in Xenopus oocytes, this CO2-induced

acidification in oocytes was much less. This decrease reflects the transport

of extracellular

) to the bath

solution resulted in a fast acidification in a water-injected control oocyte

(Fig. 1A). When

hkNBCe1 was expressed in Xenopus oocytes, this CO2-induced

acidification in oocytes was much less. This decrease reflects the transport

of extracellular  into the cell

(via NBCe1), counteracting acidification by CO2 hydration

(Fig. 1B).

into the cell

(via NBCe1), counteracting acidification by CO2 hydration

(Fig. 1B).

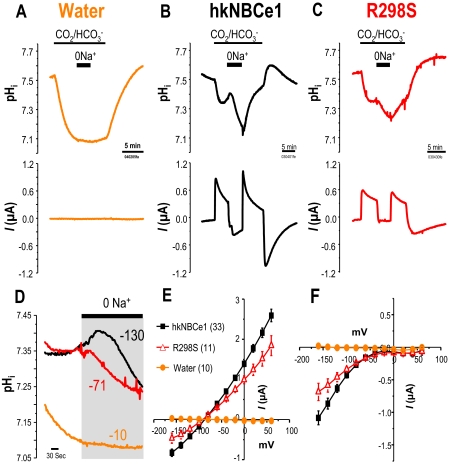

FIGURE 1.

Voltage-clamped hkNBCe1 physiology. A-C, water-injected

oocytes (A), oocytes expressing wild-type hkNBCe1 (B), and

R298S mutants (C) were voltage-clamped at -60 mV, and passing

currents I(μAmp) and pHi were measured simultaneously.

Data shown are representative experimental traces from different clones, and

the sample size of each clone is indicated in

Table 1. D, expanded

time scale of Na+ removal from panel (gray box) over 6.6

min before and after Na+ was removed from the

solution. NBCe1 transport

solution. NBCe1 transport

into the cell working against

acidification due to the CO2 exposure resulting in alkalized

pHi before the Na+ removal was only observed in

WT-hkNBCe1. After Na+ removal, pHi change (pH

units/s) of WT-hkNBCe1 (-130 × 10-5 pH units/s) decreased

fastest among the three (R298S = -71, × 10-5; water = -10

× 10-5). E and F, current-voltage

relationship of hkNBCe1 mutants. Oocytes were voltage-clamped at -60 mV and

stepped as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” Data shown

are corrected I-V traces by subtracting initial measurements in ND-96 at

corresponding voltage-steps; sample sizes are in parentheses. E,

averaged data collected in

CO2/

into the cell working against

acidification due to the CO2 exposure resulting in alkalized

pHi before the Na+ removal was only observed in

WT-hkNBCe1. After Na+ removal, pHi change (pH

units/s) of WT-hkNBCe1 (-130 × 10-5 pH units/s) decreased

fastest among the three (R298S = -71, × 10-5; water = -10

× 10-5). E and F, current-voltage

relationship of hkNBCe1 mutants. Oocytes were voltage-clamped at -60 mV and

stepped as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” Data shown

are corrected I-V traces by subtracting initial measurements in ND-96 at

corresponding voltage-steps; sample sizes are in parentheses. E,

averaged data collected in

CO2/ when the elicited

outward currents reached a steady state. The reversal potentials are -80 mV.

F, averaged traces when the inward current reached a steady state in

the 0Na+-CO2/

when the elicited

outward currents reached a steady state. The reversal potentials are -80 mV.

F, averaged traces when the inward current reached a steady state in

the 0Na+-CO2/ solution. The WT and R298S currents all rectified at positive holding voltages

with no obvious reversal potential.

solution. The WT and R298S currents all rectified at positive holding voltages

with no obvious reversal potential.

The bicarbonate transport is accompanied by a large positive (outward)

current (Fig. 1, B and

E, squares) due to the 1 Na+:

n stoichiometry of NBCe1

and the negative charge movement

(32-34).

No similar current can be observed in the water-injected oocytes

(Fig. 1, A and

E, circles). Sodium replacement with choline

(hereafter referred as Na+ removal or

“0Na+”) in a

stoichiometry of NBCe1

and the negative charge movement

(32-34).

No similar current can be observed in the water-injected oocytes

(Fig. 1, A and

E, circles). Sodium replacement with choline

(hereafter referred as Na+ removal or

“0Na+”) in a

solution reverses the

solution reverses the

transport direction

(Fig. 1, B and

D, 0Na+). That is,

transport direction

(Fig. 1, B and

D, 0Na+). That is,

is now moving out of the cell

resulting in a fast acidification and an inward current for a

hkNBCe1-expressing oocyte (9)

(Fig. 1, B and D,

0Na+, and Fig.

1F), equivalent to renal NaHCO3 absorption.

Na+ removal in

is now moving out of the cell

resulting in a fast acidification and an inward current for a

hkNBCe1-expressing oocyte (9)

(Fig. 1, B and D,

0Na+, and Fig.

1F), equivalent to renal NaHCO3 absorption.

Na+ removal in  creates

no detectable pHi change or current in the water-injected

oocytes. One can use these parameters (current magnitude,

Imax, and the rate of acidification,

dpHi/dt) with or without

CO2/

creates

no detectable pHi change or current in the water-injected

oocytes. One can use these parameters (current magnitude,

Imax, and the rate of acidification,

dpHi/dt) with or without

CO2/ solution

±Na+ to depict the transporter function

(Table 1). The overall

NBCe1-transporter contribution can also be portrayed by the buffering power

(βT) in the unit of mm/pH unit. The voltage

dependence of these hkNBCe1 currents (I-V curves;

Fig. 1, E and

F) illustrate that the membrane potential (electrical

driving force) can over-come the chemical gradients for both Na+

and

solution

±Na+ to depict the transporter function

(Table 1). The overall

NBCe1-transporter contribution can also be portrayed by the buffering power

(βT) in the unit of mm/pH unit. The voltage

dependence of these hkNBCe1 currents (I-V curves;

Fig. 1, E and

F) illustrate that the membrane potential (electrical

driving force) can over-come the chemical gradients for both Na+

and  .

.

To understand the R298S pathophysiology, we recreated this point mutation

in wild-type hkNBCe1 (WT) and expressed it in Xenopus oocytes.

Results show that R298S is a moderately functioning mutation with decreased

affinity/capacity

(Fig. 1, C-F, and

Table 1). The

CO2/

affinity/capacity

(Fig. 1, C-F, and

Table 1). The

CO2/ -elicited outward

current and the R298S-Na+-dependent currents are significantly

lower than those observed in WT. The R298S acidification rate is 78% faster

than that of WT in CO2/

-elicited outward

current and the R298S-Na+-dependent currents are significantly

lower than those observed in WT. The R298S acidification rate is 78% faster

than that of WT in CO2/ (indicating slower transport), and the acidification due to Na+

removal (renal absorption) is significantly slower than that of WT

(Fig. 1D; -71

versus -130 × 10-5 pH units/s). Comparing the rate

before (NaHCO3 influx) and after (NaHCO3 efflux)

Na+ removal in

(indicating slower transport), and the acidification due to Na+

removal (renal absorption) is significantly slower than that of WT

(Fig. 1D; -71

versus -130 × 10-5 pH units/s). Comparing the rate

before (NaHCO3 influx) and after (NaHCO3 efflux)

Na+ removal in  solution, the dpHi/dt of R298S is decreased rather than

increased as in WT, showing that

solution, the dpHi/dt of R298S is decreased rather than

increased as in WT, showing that  transport function is deficient in this human mutation. The βT

of R298S is also much less than that of WT

(Table 1). The differences in

the current magnitude between WT and R298S are voltage-dependent, yet the

reversal potential (at 0 current) remains unchanged

(Fig. 1E). The NBCe1

I-V responses further illustrate that R298S is a moderate mutation with lower

apparent

transport function is deficient in this human mutation. The βT

of R298S is also much less than that of WT

(Table 1). The differences in

the current magnitude between WT and R298S are voltage-dependent, yet the

reversal potential (at 0 current) remains unchanged

(Fig. 1E). The NBCe1

I-V responses further illustrate that R298S is a moderate mutation with lower

apparent  transport capacity and

Na+ affinity than WT.

transport capacity and

Na+ affinity than WT.

To elucidate the role of R298S in NBCe1 transport, we initiated structure-function studies. Our rationale was that sequence alignments of highly conserved residues of well characterized Slc4 protein sequences from divergent species could reveal candidate residues of transport importance (Fig. 2).

Members of the SLC4 family share 48.7% sequence identity through predicted

membrane-spanning regions, although the animal Slc4 family includes

functionally distinct

transporters(35): (a)

anion exchangers, (b)

Na+/ cotransporters, and

(c) Na+-driven

Cl--

cotransporters, and

(c) Na+-driven

Cl-- exchangers.

Interestingly, even higher identities among Slc4 members are found within

their N termini, particularly within spans of the folded N-terminal

cytoplasmic domains (57.2% on average; NBCe1 has 67% identity among

orthologs). Indeed, several 5-10-amino-acid stretches have 100% identity

(36)

(Fig. 2A), including

the absolutely conserved Arg-298 (hkNBCe1 numbering, equivalent to Arg-283 in

AE1) and its sequential neighbors. Since mutation of Arg-298 results in renal

and ocular disease and appears important for proper transporter function, we

reasoned that functional insight into NBCe1 would be gained by homology

modeling. The human NBCe1 N-terminal amino acid model

(Fig. 2, B-E) is based

on the only known Slc4 structure, the structure for the cytoplasmic N terminus

Band 3 (AE1/SLC4A1) solved by x-ray crystallography

(3).

exchangers.

Interestingly, even higher identities among Slc4 members are found within

their N termini, particularly within spans of the folded N-terminal

cytoplasmic domains (57.2% on average; NBCe1 has 67% identity among

orthologs). Indeed, several 5-10-amino-acid stretches have 100% identity

(36)

(Fig. 2A), including

the absolutely conserved Arg-298 (hkNBCe1 numbering, equivalent to Arg-283 in

AE1) and its sequential neighbors. Since mutation of Arg-298 results in renal

and ocular disease and appears important for proper transporter function, we

reasoned that functional insight into NBCe1 would be gained by homology

modeling. The human NBCe1 N-terminal amino acid model

(Fig. 2, B-E) is based

on the only known Slc4 structure, the structure for the cytoplasmic N terminus

Band 3 (AE1/SLC4A1) solved by x-ray crystallography

(3).

High sequence similarity of these two transporters and the other family members facilitated a straightforward structure prediction (Fig. 2, B-E). Corresponding sequence and secondary structural elements are found for AE1 and NBCe1 in this domain, thus confirming the identity of the entire fold. The lowest identity is observed for one larger loop region (NBCe1 residues 114-170; Fig. 2, B and D, light blue region), suggesting structural differences around the hairpin loop that binds ankyrin in Band 3. These differences are likely responsible for the lack of ankyrin binding by NBCe1. This domain fold is comprised of a central sheet surrounded by multiple helices. The spatially and somewhat separate helix-loop-helix motif represents a dimerization domain (Fig. 2B, right). Similar to Band 3, this domain in NBCe1 appears to dimerize (18). We represent NBCe1 as a monomer since we lack ultimate proof of the dimeric nature of NBCe1.

The structural model indicates that Arg-298 is located in a largely

solvent-inaccessible, polar subsurface pocket

(Fig. 2C) and that

Arg-298 is surrounded by multiple other charged and polar residues. Foremost,

Arg-298 likely forms H-bonds with either Glu-295 or Glu-91 (approximate

residue distance 3-3.5 Å) (Fig. 2,

C and E). NBCe1 residues Glu-295 and Glu-91 are

equivalent to human AE1 residues Gln-283 and Glu-85, respectively. Other

residues of this “pocket” are Thr-108 at the top (not shown) and

Thr-302 at the bottom (Fig.

2D). The pocket is flanked by two other potentially

charged residues: His-105 and His-294. The residues that form this pocket are

particularly well conserved among the Slc4

transporter sequences

(Fig. 2A), indicating

that this pocket is likely a general feature of all Slc4

transporter sequences

(Fig. 2A), indicating

that this pocket is likely a general feature of all Slc4

transporters.

transporters.

To test our putative structure for the NBCe1 N terminus, we created point

mutations in hkNBCe1 to perturb the putative charge interactions among three

residues (Arg-298, Glu-91, and Glu-295)

(Fig. 3). Our NBCe1 model

(Fig. 2, B and

E) predicted that the mutations would cause charge

repulsion, thereby opening the N-terminal structure and altering NBCe1

function. We began by evaluating the effect of R298E on the hkNBCe1 transport

function by altering the charge of the disease-mutation from a neutrally

charged (Ser) to a negatively charged residue

(37). The

-evoked currents and

Na+-dependent currents in R298E are ∼71% of WT

(Fig. 3, A and

E, and Table

1). CO2 acidifies R298E oocytes 72% faster than WT,

whereas Na+ removal in

-evoked currents and

Na+-dependent currents in R298E are ∼71% of WT

(Fig. 3, A and

E, and Table

1). CO2 acidifies R298E oocytes 72% faster than WT,

whereas Na+ removal in  acidifies WT 74% faster than R298E (Fig. 3,

A and D). These results represent an impaired

NBCe1 transport function resulting from the R298E mutation. All of these

results are consistent with R298E-expressing oocytes having a buffering power

(βT) three times smaller than that of WT. Nevertheless, the

I-V relationships for R298E (Fig. 3,

E and F) are similar to the R298S disease

mutation (Fig. 1, E and

F). The

CO2/

acidifies WT 74% faster than R298E (Fig. 3,

A and D). These results represent an impaired

NBCe1 transport function resulting from the R298E mutation. All of these

results are consistent with R298E-expressing oocytes having a buffering power

(βT) three times smaller than that of WT. Nevertheless, the

I-V relationships for R298E (Fig. 3,

E and F) are similar to the R298S disease

mutation (Fig. 1, E and

F). The

CO2/ reversal potentials

(-80 mV) are similar for R298S-, R298E-, and WT-hkNBCe1 (Figs.

1E and

3E), indicating no

fundamental change in stoichiometry of ion transport.

reversal potentials

(-80 mV) are similar for R298S-, R298E-, and WT-hkNBCe1 (Figs.

1E and

3E), indicating no

fundamental change in stoichiometry of ion transport.

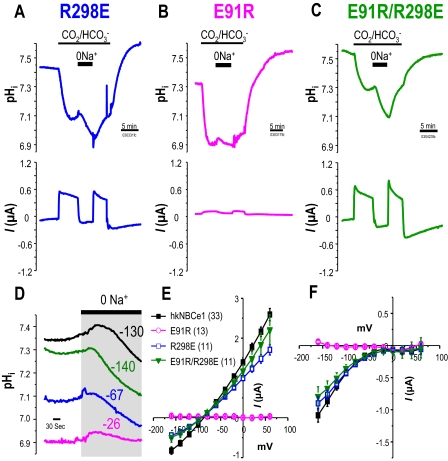

FIGURE 3.

Voltage-clamped hkNBCe1 mutants physiology. Oocytes expressing R298E

(A), E91R (B), or E91R/R298E (C) mutants were

voltage-clamped at -60 mV, and passing currents I(μAmp) and

pHi were measured simultaneously as in

Fig. 1. Data shown are

representative experimental traces from different clones, and the sample size

of each clone is indicated in Table

1. The R298E mutant has decreased currents and less substantial

pHi changes in response to the addition of

CO2/ and/or

Na+ removal. The E91R mutant transport function is almost abolished

in terms of current magnitude and pHi changes. Double

mutant E91R/R298E operates approximately like a wild-type hkNBCe1. D,

expanded time scale of Na+ removal from panel (gray box)

over 6.6 min before and after Na+ was removed from the

and/or

Na+ removal. The E91R mutant transport function is almost abolished

in terms of current magnitude and pHi changes. Double

mutant E91R/R298E operates approximately like a wild-type hkNBCe1. D,

expanded time scale of Na+ removal from panel (gray box)

over 6.6 min before and after Na+ was removed from the

solution. NBCe1 transports

solution. NBCe1 transports

into the cell, working against

acidification due to CO2 exposure, resulting in increased

pHi of different magnitudes prior to 0Na+.

After Na+ removal, the pHi changes

(×10-5 pH units/s) are E91R/R298E ≈ WT > R298E (=

R298S) > E91R. E and F, current-voltage relationship of hkNBCe1

mutants. Data shown are corrected I-V traces by subtracting initial

measurements in ND-96 at corresponding voltage-steps; numbers are in

parentheses. E, averaged data collected in

CO2/

into the cell, working against

acidification due to CO2 exposure, resulting in increased

pHi of different magnitudes prior to 0Na+.

After Na+ removal, the pHi changes

(×10-5 pH units/s) are E91R/R298E ≈ WT > R298E (=

R298S) > E91R. E and F, current-voltage relationship of hkNBCe1

mutants. Data shown are corrected I-V traces by subtracting initial

measurements in ND-96 at corresponding voltage-steps; numbers are in

parentheses. E, averaged data collected in

CO2/ . The reversal

potentials are approximately -80 mV. F, averaged steady state inward

current with

0Na+-CO2/

. The reversal

potentials are approximately -80 mV. F, averaged steady state inward

current with

0Na+-CO2/ solution. The wild-type and mutants currents all rectified at positive holding

voltages with no obvious reversal potential.

solution. The wild-type and mutants currents all rectified at positive holding

voltages with no obvious reversal potential.

Interestingly, E91R-hkNBCe1 exhibits very severe defects in ion transport

function (Fig. 3B and

Fig. S1B). The

CO2/ -evoked current in

E91R appears gradually and reaches a plateau only slowly, instead of

maximizing quickly followed by a slow decay as seen in the WT

(Fig. 1A and Fig.

S1A). The current magnitude is 20 times smaller than in WT

(Fig. 3, E and

F, and Table

1). Accordingly, the CO2-induced acidification is much

faster for E91R (Fig.

3B), i.e. greatly reduced

-evoked current in

E91R appears gradually and reaches a plateau only slowly, instead of

maximizing quickly followed by a slow decay as seen in the WT

(Fig. 1A and Fig.

S1A). The current magnitude is 20 times smaller than in WT

(Fig. 3, E and

F, and Table

1). Accordingly, the CO2-induced acidification is much

faster for E91R (Fig.

3B), i.e. greatly reduced

transport.

Na+-dependent currents (Fig. 3,

E and F, circles) and acidification

(Fig. 3D) are also

much less and slower in E91R. These properties translate into significantly

less

transport.

Na+-dependent currents (Fig. 3,

E and F, circles) and acidification

(Fig. 3D) are also

much less and slower in E91R. These properties translate into significantly

less  transport (lower

βT) of E91R than that of WT. The E91R I-V relationship has no

clear reversal potential in

CO2/

transport (lower

βT) of E91R than that of WT. The E91R I-V relationship has no

clear reversal potential in

CO2/ , but the small

, but the small

-elicited currents are still

voltage-dependent (Fig. 3, E and

F, circles). E91R is a much more impaired

mutation than R298S, as indicated by the E91R I-V relationships resembling

that of water-injected controls. However, these

-elicited currents are still

voltage-dependent (Fig. 3, E and

F, circles). E91R is a much more impaired

mutation than R298S, as indicated by the E91R I-V relationships resembling

that of water-injected controls. However, these

-elicited and

Na+-dependent currents of E91R are significantly higher than those

of water-injected controls (Table

1). The dpHi/dt

(

-elicited and

Na+-dependent currents of E91R are significantly higher than those

of water-injected controls (Table

1). The dpHi/dt

( transport) due to solution change

for E91R (Fig. 3, B and

D) is also significantly different from water-injected

controls (Fig. 1, A and

D).

transport) due to solution change

for E91R (Fig. 3, B and

D) is also significantly different from water-injected

controls (Fig. 1, A and

D).

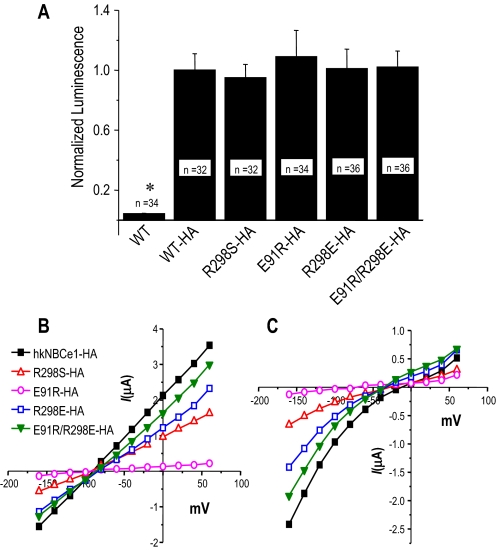

The surface expression of the NBCe1 transporter protein in the oocytes was

quantified by detecting an HA tag engineered into the extracellular loop of

hkNBCe1 and the NBCe1 mutants. Basal luminescence of oocyte surfaces was

determined using oocytes expressing the untagged WT-hkNBCe1 transporter. The

luminescence values of the HA-tagged mutants were not significantly different

from that of the HA-tagged WT-hkNBCe1, demonstrating that there was no

difference in surface expression of NBCe1 protein between the WT and mutants.

These data confirm that the E91R-hkNBCe1 protein is appropriately trafficked

and expressed at the oocyte plasma membrane

(Fig. 4A). These

results also verified that the extracellular HA tag did not alter the

-elicited current

(Fig. 4B) or the

0Na+/

-elicited current

(Fig. 4B) or the

0Na+/ -elicited currents

(Fig. 4C) when

compared with untagged NBCe1 proteins (Figs.

1, E and F,

and 3, E and

F).

-elicited currents

(Fig. 4C) when

compared with untagged NBCe1 proteins (Figs.

1, E and F,

and 3, E and

F).

FIGURE 4.

NBCe1 surface expression in oocytes. A, the normalized

luminescence value (mean ± S. E.) of oocytes expressing HA-tagged

hkNBCe1 mutants. The surface expression of the transporter protein on the

oocytes was labeled by a monoclonal rat-α-HA 1° antibody and a

goat-α-rat horseradish peroxidase-IgG 2° antibody and measured with

a luminometer after adding chemiluminescent substrate. The luminescence values

of the clones were normalized to the value of the WT-hkNBCe1 with HA tag. The

oocytes were from three different donor frogs and sample sizes of each clone

are shown in the bars. The asterisk indicates a luminescence

value for that clone that is statistically different (p < 0.01)

from that of HA-tagged WT-hkNBCe1. B and C, the

current-voltage relationship of hkNBCe1 mutants in

CO2/ (B) and in

0Na+-CO2/

(B) and in

0Na+-CO2/ solutions (C).

solutions (C).

The CO2/ -induced

acidifications (Fig. 3, C and

D) and currents (Fig.

5, A and B) of E91R/R298E are not significantly

different from WT (Table 1).

The Na+-dependent current (Fig.

5B) and Na+ removal-elicited acidifications

(Fig. 3D) are similar

for E91R/R298E and WT. Wt has a slightly higher (not significant)

βT than E91R/R298E. The E91R/R298E, I-V relationships are also

comparable with those of WT in

CO2/

-induced

acidifications (Fig. 3, C and

D) and currents (Fig.

5, A and B) of E91R/R298E are not significantly

different from WT (Table 1).

The Na+-dependent current (Fig.

5B) and Na+ removal-elicited acidifications

(Fig. 3D) are similar

for E91R/R298E and WT. Wt has a slightly higher (not significant)

βT than E91R/R298E. The E91R/R298E, I-V relationships are also

comparable with those of WT in

CO2/ solutions with and

without Na+ (Fig. 3, E

and F).

solutions with and

without Na+ (Fig. 3, E

and F).

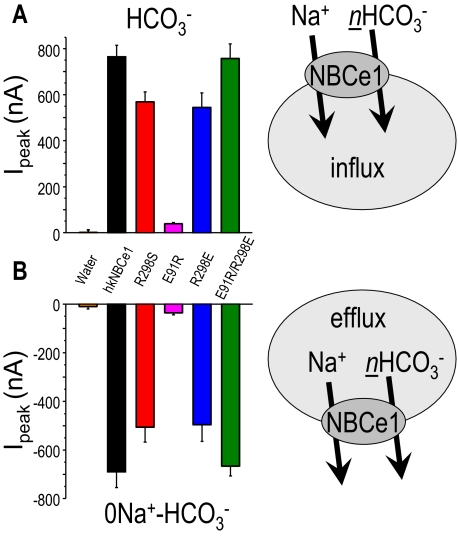

FIGURE 5.

Summary of structural effects on hkNBCe1 function. A,

averaged peak outward currents collected in

CO2/ (pH 7.5) solution,

i.e. inward NaHCO3 uptake (right). B,

average peak inward current in

0Na+-CO2/

(pH 7.5) solution,

i.e. inward NaHCO3 uptake (right). B,

average peak inward current in

0Na+-CO2/ (pH

7.5) solution, i.e. outward renal transport (right). Oocytes

expressing different hkNBC1 mutants and water-injected oocytes were

voltage-clamped at -60 mV. The current changes were recorded in various

experimental solutions, and peak current changes were calculated by

subtracting the elicited currents before and after the

(pH

7.5) solution, i.e. outward renal transport (right). Oocytes

expressing different hkNBC1 mutants and water-injected oocytes were

voltage-clamped at -60 mV. The current changes were recorded in various

experimental solutions, and peak current changes were calculated by

subtracting the elicited currents before and after the

or 0Na+

or 0Na+

solutions were introduced. The

sample size for each clone is in Table

1. R298S and R298E are mutants with less pronounced peak current

changes, which indicates altered transport functions. E91R is a severe

mutation with nearly abolished transport function having significantly less

current responses to solution changes. R298S, E91R, and R298E currents are

stoically different from WT and E91R/R298E. E91R/R298E double mutant has peak

current changes identical to WT-hkNBCe1, indicating that E91R/R298E restores

E91R to a fully WT-hkNBCe1-like function (not statistically different from

WT).

solutions were introduced. The

sample size for each clone is in Table

1. R298S and R298E are mutants with less pronounced peak current

changes, which indicates altered transport functions. E91R is a severe

mutation with nearly abolished transport function having significantly less

current responses to solution changes. R298S, E91R, and R298E currents are

stoically different from WT and E91R/R298E. E91R/R298E double mutant has peak

current changes identical to WT-hkNBCe1, indicating that E91R/R298E restores

E91R to a fully WT-hkNBCe1-like function (not statistically different from

WT).

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that we might gain additional insights of NBCe1 structure and function by mapping the hkNBCe1, SLC4A4, amino acid sequence onto the AE1 crystal structure (Protein Data Bank (PDB) number 1HYN) (3). From this NBCe1 structural model, Arg-298 of NBCe1 is predicted to hydrogen-bond with Glu-91 and Glu-295. R298S is a human NBCe1 mutation resulting in renal and eye disease (see “Results”). Interestingly, Arg-298 is a conserved residue in the animal Slc4 protein family and is predicted to lie in a “solvent-inaccessible pocket.” To test whether our structural model of NBCe1 was valid, we mutated these putative interacting residues. The modeling and functional data of the E91R-NBCe1 mutant imply that charge alterations (particularly the introduction of additional cationic side chains) are disruptive to the pocket structure around Arg-298. To further probe the role of residue charge at this putative solvent-inaccessible pocket, we examined the effect of charge reversal through a double mutation, E91R/R298E-hkNBCe1 (Fig. 3, C-F and Fig. S1C). If structure and charge interaction rather than exact sequence are important, we predicted that a clone that simultaneously reverses the charge of Glu-91 and Arg-298 (E91R/R298E) would have transporter function that resembles those of wild-type NBCe1.

The data presented here show that the double mutant (E91R/R298E) can restore E91R to full “WT-like” function (Fig. 5, A and B). Thus, either the double mutant reverses the structural effect of E91R on wild-type function or R298E quenches the effects of E91R on the transport function (Figs. 1, 3, and 4 and Fig. S1) by restoring the native structure (Fig. 2, B-E). Although all tested mutants imply a role for this domain and particularly this pocket in the transmembrane ion transport, this rescue mutation presents the strongest evidence and validation for the close proximity between Glu-91 and Arg-298, i.e. correctness of this model, and for a direct residue- and location-specific correlation of the structural and functional changes. A similar residue charge interaction was reported recently between a pair of arginine and glutamate residues in a Torpedo acetylcholine receptor structure model (38). Acetylcholine-evoked single-channel currents were measured from receptors with R209E or E45R mutation and the corresponding double mutation. The charge-reversal double mutation yielded surface expression and rescued wild-type acetylcholine-function abolished by single mutations.

Glu-91 and its sequential neighbor Glu-92 are part of the highly conserved motif (WRETARWIKFEE; amino acids 336-347 in hkNBCe1) (Fig. 2A) proposed to determine pH sensitivity of murine anion exchanger AE2/SLC4A2 (39-41). Intriguingly, Glu-92 similarly is suggested by the model to be part of a second unusual feature of this fold. Glu-92 is located on the opposite side of the β-sheet from Glu-91. It is involved in a network of interacting residues as it hydrogen-bonds to arginine 86 (Arg-86) and potentially Lys-227 (Fig. 2E). Arg-86 in turn interacts with Glu-272. Residues Arg-86, Glu-92, Lys-227, and Glu-272 are highly conserved in the Slc4 bicarbonate transporters (Fig. 2A), and these functionally important residues share number, charge, and residue type, nearly duplicating the properties of the pocket as for Glu-91, Glu-295, and Arg-298. Together, these residues create an unusual continuous chain of interconnected polar residues and a steady path of high polarity through the core of this domain from the membrane oriented C-terminal side (Fig. 2, D and E) to the interior.

It is intriguing to speculate on the function of this feature. This pathway may attenuate ion transport (or even serve as an ion transport pathway). Interestingly, when the same group of residues is mutated in AE2 (R341A, W342A, E346A, and E347A), pH sensitivity of wild-type anion transport is abolished (39-41). A mutagenesis study of murine AE2 residues identified a histidine residue, corresponding to His-105 in NBCe1 amino acid sequence, important for regulation of Cl- transport (40). Histidine and lysine are hydrophilic, positively charged basic amino acids highly likely to be a potential pH sensor(s) for NBCe1. These residues have been characterized as pH sensors in many studies: acid-sensing ion channels (42), tandem pore domain acid-sensitive K+ channel (TASK-3) (43), Na+/H+ antiporter (44), and ROMK1 channels (45). Glutamate, negatively charged and acidic amino acid, was also identified as the pH sensor in other investigations of uncoupling protein (46), TRPV5 channel (47), and ClC-2G Cl- channel (48).

Finally, it is noteworthy that the Slc4 gene family spans eukaryotes from

humans to yeast to plants. In plants and yeast, Slc4 proteins have not been

shown to transport  but rather

borate (49). The

Arabidopsis and mammalian boron transporter (BOR1/Slc4a11)

(50) members lack ∼391

cytoplasmic N-terminal sequence found in mammalian NBCe1 or other animal Slc4

members, and these boron transporters do not transport

but rather

borate (49). The

Arabidopsis and mammalian boron transporter (BOR1/Slc4a11)

(50) members lack ∼391

cytoplasmic N-terminal sequence found in mammalian NBCe1 or other animal Slc4

members, and these boron transporters do not transport

. In addition, human pancreatic

NBCe1 isoform (pNBC1/NBCe1-B) has an N-terminal variation with a lower

bicarbonate transport capacity

(17), which is disinhibited by

an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding protein (IRBIT)

(51). These results

corroborate the suggestion of a critical role of NBCe1 N terminus in

. In addition, human pancreatic

NBCe1 isoform (pNBC1/NBCe1-B) has an N-terminal variation with a lower

bicarbonate transport capacity

(17), which is disinhibited by

an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding protein (IRBIT)

(51). These results

corroborate the suggestion of a critical role of NBCe1 N terminus in

transport. The structure modeling

points us to candidate residues for mutation analysis that eventually gave

rise to a severe functional mutation, E91R

(Fig. 2).

transport. The structure modeling

points us to candidate residues for mutation analysis that eventually gave

rise to a severe functional mutation, E91R

(Fig. 2).

The effect of the R298S-hkNBCe1 mutation is unclear in the literature. R298S has been reported reducing wild-type function (1) and as a protein trafficking problem (1, 9, 16). This latter report uses Xenopus oocytes as we have in this study. Horita et al. (16) implied oocyte surface expression by coincident fluorescence of a NBCe1-A N-terminal antibody (intracellular epitope) and wheat germ agglutinin as a general marker of plasma membrane (extracellular). The data presented in Fig. 4A use an extracellular tag of the hkNBCe1 molecule, i.e. a direct assessment of the NBCe1 proteins at the plasma membrane. Contrary to the previous Xenopus oocyte report (1, 9, 16), the data in Fig. 4 also explicitly show that R298S-hkNBCe1 affects NBCe1 function and not NBCe1 protein processing.

This report provides a structure model and biophysical role for the NBCe1 N

terminus based in part on a human NBCe1 disease mutation (R298S), summarized

in Fig. 5. R298S-hkNBCe1

affects NBCe1 function and not NBCe1 protein processing

(Fig. 4). Further, we detect

the very unusual polarity of multiple core residues in the N-terminal domain,

suggesting that this chain of connected residues may create and ion transport

pathway, thus providing a possible explanation for its ion transport role and

putative pH sensitivity. This solvent-inaccessible pocket appears conserved in

all  -transporting Slc4 proteins.

Thus, this work brings to light a new structural domain critical for

-transporting Slc4 proteins.

Thus, this work brings to light a new structural domain critical for

transport in the Slc4

proteins.

transport in the Slc4

proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nathan Angle, Montelle Sanders, Gerald T. Babcock, Heather L. Holmes and Elyse M. Scileppi for technical support. We thank Dr. Jun-ichi Satoh and Brenda Smith for making and performing initial experiments with R298S-hkNBCe1, respectively. We also thank Drs. Corey Smith (Case Western Reserve University) and Steve Sine (Mayo Clinic) for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK056218 and EY017732 (to M. F. R.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure.

Footnotes

SLC is the Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) nomenclature for solute carrier genes (see Ref. 4). All capital names represent human genes, whereas lowercase designations represent orthologs from other species.

The abbreviations used are: NHE, Na+-H+ exchanger;

NBCe1, electrogenic Na+/ cotransporter 1; pHi, intracellular pH; AE1 (Band 3,

Slc4a1), anion exchanger 1; β, buffering capacity (mM/pH unit); NBC,

Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter; WT, wild type; HA, hemagglutinin;

hk, human kidney.

cotransporter 1; pHi, intracellular pH; AE1 (Band 3,

Slc4a1), anion exchanger 1; β, buffering capacity (mM/pH unit); NBC,

Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter; WT, wild type; HA, hemagglutinin;

hk, human kidney.

References

- 1.Igarashi, T., Inatomi, J., Sekine, T., Cha, S. H., Kanai, Y., Kunimi, M., Tsukamoto, K., Satoh, H., Shimadzu, M., Tozawa, F., Mori, T., Shiobara, M., Seki, G., and Endou, H. (1999) Nat. Genet. 23 264-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero, M. F., and Smith, B. L. (2002) FASEB J. 16 a52-a53 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, D., Kiyatkin, A., Bolin, J. T., and Low, P. S. (2000) Blood 96 2925-2933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alper, S. L. (2002) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64 899-923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero, M. F. (2005) Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 14 495-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biemesderfer, D., Pizzonia, J., Abu-Alfa, A., Exner, M., Reilly, R., Igarashi, P., and Aronson, P. S. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 265 F736-F742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultheis, P. J., Clarke, L. L., Meneton, P., Miller, M. L., Soleimani, M., Gawenis, L. R., Riddle, T. M., Duffy, J. J., Doetschman, T., Wang, T., Giebisch, G., Aronson, P. S., Lorenz, J. N., and Shull, G. E. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19 282-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, T., Yang, C. L., Abbiati, T., Schultheis, P. J., Shull, G. E., Giebisch, G., and Aronson, P. S. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277 F298-F302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinour, D., Chang, M.-H., Satoh, J.-I., Smith, B. L., Angle, N., Knecht, A., Serban, I., Holtzman, E. J., and Romero, M. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 52238-52246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igarashi, T., Inatomi, J., Sekine, T., Seki, G., Shimadzu, M., Tozawa, F., Takeshima, Y., Takumi, T., Takahashi, T., Yoshikawa, N., Nakamura, H., and Endou, H. (2001) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12 713-718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igarashi, T., Inatomi, J., Sekine, T., Takeshima, Y., Yoshikawa, N., and Endou, H. (2000) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11 A0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demirci, F. Y., Chang, M.-H., Mah, T. S., Romero, M. F., and Gorin, M. B. (2006) Mol. Vis. 12 324-330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toye, A. M., Parker, M. D., Daly, C. M., Lu, J., Virkki, L. V., Pelletier, M. F., and Boron, W. F. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. 291 C788-C801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gawenis, L. R., Bradford, E. M., Prasad, V., Lorenz, J. N., Simpson, J. E., Clarke, L. L., Woo, A. L., Grisham, C., Sanford, L. P., Doetschman, T., Miller, M. L., and Shull, G. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 9042-9052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inatomi, J., Horita, S., Braverman, N., Sekine, T., Yamada, H., Suzuki, Y., Kawahara, K., Moriyama, N., Kudo, A., Kawakami, H., Shimadzu, M., Endou, H., Fujita, T., Seki, G., and Igarashi, T. (2004) Pfluegers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 448 438-444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horita, S., Yamada, H., Inatomi, J., Moriyama, N., Sekine, T., Igarashi, T., Endo, Y., Dasouki, M., Ekim, M., Al-Gazali, L., Shimadzu, M., Seki, G., and Fujita, T. (2005) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16 2270-2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tatishchev, S., Abuladze, N., Pushkin, A., Newman, D., Liu, W., Weeks, D., Sachs, G., and Kurtz, I. (2003) Biochemistry 42 755-765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill, H. S., and Boron, W. F. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Crystalliz. Comm. 62 534-537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. C. (1997) Electrophoresis 18 2714-2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, X., and Miller, W. (1991) Adv. Appl. Math. 12 337-357 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwede, T., Kopp, J., Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. C. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3381-3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canutescu, A. A., Shelenkov, A. A., and Dunbrack, R. L., Jr. (2003) Protein Sci. 12 2001-2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willard, L., Ranjan, A., Zhang, H., Monzavi, H., Boyko, R. F., Sykes, B. D., and Wishart, D. S. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3316-3319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., and Thornton, J. M. (1998) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 631-639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vriend, G. (1990) J. Mol. Graph. 8 52-56, 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero, M. F., Fong, P., Berger, U. V., Hediger, M. A., and Boron, W. F. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274 F425-F432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAlear, S. D., Liu, X., Williams, J. B., McNicholas-Bevensee, C. M., and Bevensee, M. O. (2006) J. Gen. Physiol. 127 639-658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margeta-Mitrovic, M., Jan, Y. N., and Jan, L. Y. (2000) Neuron 27 97-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zerangue, N., Schwappach, B., Jan, Y. N., and Jan, L. Y. (1999) Neuron 22 537-548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo, D., Kim, B. Y., Campo, C., Nance, L., King, A., Maouyo, D., and Welling, P. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 23066-23075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romero, M. F., Hediger, M. A., Boulpaep, E. L., and Boron, W. F. (1997) Nature 387 409-413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sciortino, C. M., and Romero, M. F. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277 F611-F623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross, E., Abuladze, N., Pushkin, A., Kurtz, I., and Cotton, C. U. (2001) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 531 375-382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gross, E., Hawkins, K., Abuladze, N., Pushkin, A., Cotton, C. U., Hopfer, U., and Kurtz, I. (2001) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 531 597-603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero, M. F., Fulton, C. M., and Boron, W. F. (2004) Pfluegers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 447 495-509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero, M. F., and Boron, W. F. (1999) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61 699-723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham, R., Steplock, D., Wang, F., Huang, H., E, X., Shenolikar, S., and Weinman, E. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 37815-37821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, W. Y., and Sine, S. M. (2005) Nature 438 243-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chernova, M. N., Stewart, A. K., Jiang, L., Friedman, D. J., Kunes, Y. Z., and Alper, S. L. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. 284 C1235-C1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart, A. K., Kerr, N., Chernova, M. N., Alper, S. L., and Vaughan-Jones, R. D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 52664-52676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chernova, M. N., Jiang, L., Friedman, D. J., Darman, R. B., Lohi, H., Kere, J., Vandorpe, D. H., and Alper, S. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 8564-8580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baron, A., Schaefer, L., Lingueglia, E., Champigny, G., and Lazdunski, M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 35361-35367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajan, S., Wischmeyer, E., Xin Liu, G., Preisig-Muller, R., Daut, J., Karschin, A., and Derst, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 16650-16657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerchman, Y., Olami, Y., Rimon, A., Taglicht, D., Schuldiner, S., and Padan, E. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90 1212-1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fakler, B., Schultz, J. H., Yang, J., Schulte, U., Brandle, U., Zenner, H. P., Jan, L. Y., and Ruppersberg, J. P. (1996) EMBO J. 15 4093-4099 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klingenberg, M., Echtay, K. S., Bienengraeber, M., Winkler, E., and Huang, S. G. (1999) Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 23 (Suppl. 6) S24-S29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeh, B. I., Sun, T. J., Lee, J. Z., Chen, H. H., and Huang, C. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 51044-51052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stroffekova, K., Kupert, E. Y., Malinowska, D. H., and Cuppoletti, J. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275 C1113-C1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takano, J., Noguchi, K., Yasumori, M., Kobayashi, M., Gajdos, Z., Miwa, K., Hayashi, H., Yoneyama, T., and Fujiwara, T. (2002) Nature 420 337-340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park, M., Li, Q., Shcheynikov, N., Zeng, W., and Muallem, S. (2004) Mol. Cell 16 331-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shirakabe, K., Priori, G., Yamada, H., Ando, H., Horita, S., Fujita, T., Fujimoto, I., Mizutani, A., Seki, G., and Mikoshiba, K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 9542-9547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.