Abstract

The regulation of DNA relaxation by topoisomerase 1 (TOP1) is essential for DNA replication, transcription, and recombination events. TOP1 activity is elevated in cancer cells, yet the regulatory mechanism restraining its activity is not understood. We present evidence that the tumor suppressor protein prostate apoptosis response-4 (Par-4) directly binds to TOP1 and attenuates its DNA relaxation activity. Unlike camptothecin, which binds at the TOP1-DNA interface to form cleavage complexes, Par-4 interacts with TOP1 via its leucine zipper domain and sequesters TOP1 from the DNA. Par-4 knockdown by RNA-interference enhances DNA relaxation and gene transcription activities, and promotes cellular transformation in a TOP1-dependent manner. Conversely, attenuation of TOP1 activity either by RNA-interference or Par-4 over-expression impedes DNA relaxation, cell cycle progression, and gene transcription activities, and inhibits transformation. Collectively, our findings suggest that Par-4 serves as an intracellular repressor of TOP1 catalytic activity and regulates DNA topology to suppress cellular transformation.

Keywords: Par-4, Topoisomerase 1, DNA relaxation, cellular transformation

Introduction

Topoisomerase 1 (TOP1) is a monomeric enzyme, which relaxes both negative and positive supercoils in the DNA by generating a single-strand nick, allowing rotation of the nicked strand around the intact strand, and re-ligating the cleaved DNA in an ATP-independent manner (1, 2, 3, 4). The DNA relaxation function of TOP1 is essential for the fundamental biological processes of DNA replication, transcription, and recombination (1), and accordingly mutants completely lacking TOP1 activity are lethal (5, 6). A number of tumor suppressor proteins have been shown to bind TOP1 and promote its DNA relaxation function (1), yet the intracellular feedback control mechanisms that restrict excessive accessibility of TOP1 to the DNA remain poorly defined.

Consistent with the role of TOP1 in promoting cell growth, TOP1 protein levels are elevated in proliferating cells (7), while reduced TOP1 activity is observed in non-proliferating cells (8). Moreover, TOP1 enzyme activity and/or levels are elevated in several types of cancers (9). Therefore, TOP1 inhibitors of the camptothecin (CPT, a cytotoxic plant alkaloid) family, are used clinically to treat small cell lung cancer, as well as ovarian and colon cancer (3). CPTs crosslink TOP1 and DNA at their interface, and, as a result, prevent the nicked DNA from being re-ligated thereby abrogating DNA synthesis and transcription, and causing S-phase arrest and apoptosis in proliferating cells (3, 10).

While TOP1 activity is essential for cell viability, unrestricted TOP1 activity results in illegitimate recombination events (11). This implies that if DNA-TOP1 cleavage complexes accumulate longer they may promote indiscriminate recombination events and genomic instability (12, 13). Although such observations suggest a role for TOP1 in tumor promotion and maintenance, the precise involvement of TOP1 in cellular transformation and tumorigenesis has not been described. We present here evidence that the tumor suppressor protein, prostate apoptosis response-4 (Par-4) (14), functions as an endogenous regulator of TOP1-dependent DNA relaxation and cellular transformation by binding to TOP1 and sequestering it from its DNA substrate.

Although first identified in prostate cancer cells undergoing apoptosis in response to an exogenous insult (14), Par-4 is widely known to be expressed ubiquitously among the various tissue types (15, 16, 17, 18, 19). The biological significance of Par-4 is underscored by its effects in mice. Par-4 knockout mice develop spontaneous tumors in various tissues, and show an increased incidence of chemical- and hormone-inducible tumors of the bladder and endometrium (20). Consistent with its tumor suppressor function, Par-4 is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma (16) and endometrial tumors (21). Moreover, in prostate cancer, endogenous Par-4 is inactivated via binding and phosphorylation (at S230 in human Par-4 and S249 in rat Par-4) by the cell survival kinase, Akt1 (22). In contrast to the Par-4 knockout mice, transgenic mice that ubiquitously express additional copies of Par-4 or its core SAC-domain display normal development and life span, and are resistant to the growth of spontaneous, as well as oncogene-induced, autochthonous tumors (23). Resistance to tumorigenesis was linked to inhibition of NF-κB activity and Par-4/SAC domain-mediated induction of apoptosis in the oncogene-expressing cells (23). Most of the studies thus far have elucidated the role of Par-4 in induction of apoptosis. Although Par-4 is amply expressed in normal/immortalized cells and most cancer cells, its physiological role in cell metabolism remains uncharacterized. We sought to identify interaction partners of Par-4 to determine the function of Par-4 in normally growing cells. Our studies identified TOP1 as a binding partner of Par-4, and suggest Par-4-mediated sequestration of TOP1 from its DNA substrate regulates DNA relaxation and prevents cellular transformation.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human immortalized epithelial cells BPH-1, prostate cancer cells PC-3, lung cancer cells A549, cervical cancer cells HeLa, human primary lung fibroblasts HEL, and mouse immortalized fibroblasts NIH 3T3 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection, MD). The medium and conditions for growth of the cell lines have been previously described (24, 25). NIH 3T3 cells stably expressing oncogenic H-ras-V12 (NIH 3T3/Ras) (24,25) (from Albert Baldwin, Jr., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC) were previously described.

Plasmids, recombinant proteins, and chemical reagents

The mammalian plasmid expression constructs for full length Par-4-GFP (tagged to green fluorescent protein) or Par-4 mutants (1-204aa, 1-267aa/ΔZIP-GFP), adenoviral expression constructs for Par-4-GFP and GFP, as well as the Escherichia coli plasmid expression constructs GST-Par-4, GST-ΔZIP (1-267), and GST have been previously described (12, 13). The reporter plasmid pTA-Luciferase (pTal) containing the TATA-box (from the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter), and pTal-NF-kappaB, pTal-AP1, pTal-SRE, containing transcription enhancer elements for NF-kappaB, AP1 or SRF were from Clontech, Inc. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged TOP1 expression construct (26), was kindly provided by William T. Beck, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL.

E. coli BL21DE3 cells (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) were transformed with GST-Par-4, GST-ΔZIP, GST-ZIP, or GST vector (27) and induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (Sigma). The fusion proteins were purified using glutathione beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Co.).

Human TOPI purified from freshly extracted human placenta was purchased from either TopoGEN, Inc. (Columbus, Ohio) or Calbiochem Corp., or was purified from TN5 insect cells using a Baculovirus construct (HighFive, Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA). Camptothecin was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp. (San Diego,CA), or from the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD).

Antibodies, siRNAs and other reagents

The polyclonal antibody for Par-4 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Two different polyclonal antibodies for TOP1 were used: TOP1 (Ab1) was from TopoGEN, Inc., and TOP1 (Ab2) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The antibodies for caspase-3 were from Cell Signaling, Inc. The monoclonal antibody for β-actin was from Sigma Chemical Corp. The control siRNA and siRNAs for human and mouse Par-4 or TOP1 were from Dharmacon, Inc and SantaCruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Transfection and Reporter Assays

Cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter along with the β-galactosidase expression construct (for an internal control) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corp.). Whole-cell extracts from the transfectants were examined for either luciferase activity (using the SteadyLite Plus kit; PerkinElmer) or β-galactosidase activity as described previously (28, 29). The luciferase activity in each reaction was normalized with respect to the corresponding β-galactosidase activity, and expressed as relative luciferase activity.

Western blot analysis

Nuclear extracts (prepared with NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit from Pierce, Corp.) and whole-cell protein extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and subjected to Western blot analysis for Par-4, TOP1, or β-actin with the indicated antibodies. Blots were developed by using enhanced chemi-luminescence (Amersham Corp.).

GST-pull down assay

Purified GST (6 μg) or GST-Par-4 (3 μg) protein was incubated with glutathione beads for 30 min, and subsequently washed and incubated with cell extracts (10 μg), for 18 h at 4°C. Protein eluted from the beads was resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Coomassie blue staining and mass spectrometry at the Protein Core Facility of the Columbia University Medical Center.

To study direct binding of Par-4 and TOP1, purified GST (1 μg) or GST-Par-4 (200 ng) was incubated in the presence or absence of purified TOP1 (600 ng) for 3 h at 4°C, and incubated with glutathione beads for 1 h. Bound complexes were pulled down with the beads, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer (containing 1× PBS at pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM sodium chloride, and protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche, Inc.), centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min to remove cell debris, and pre-cleared by adding 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads. Pre-cleared lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with 2.5 or 5 μg of antibody conjugated to 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads. The immunoprecipitates were washed with lysis buffer, and subjected to Western blot analysis.

DNA relaxation assays, CPT-induced DNA cleavage assays, and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

TOP1 activity was measured by the relaxation of supercoiled plasmid pUC19 DNA (from Invitrogen Corp.). The assay mixture consisted of 1 μg of pUC19 DNA, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 10 mM EDTA, 1.5 M NaCl, 1 mM spermidine, 50% glycerol, and 0.1 mg/ml BSA. GST-Par-4 or GST proteins (200 ng) were added prior to the addition of TOP1. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 20 ng of TOP1 and allowed to proceed at 37°C for 30 min. Products were run on a 1% agarose gel at 75 V for 30 min in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, and 2 mM EDTA, pH 8). The gels were stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) for 30 min. The bands were visualized by illumination from below with short-wave UV light and photographed.

TOP1 cleavage assays used a 161-bp 3′-end labeled DNA fragment (containing TOP1 binding sites) from pBluescript SK(-) phagemid DNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) that was generated as previously described (28, 29). Labeled DNA (∼50 fmol/reaction) was incubated with 50 ng of recombinant TOP1, with or without CPT (1 μM), GST-Par-4 or mutant proteins (75, 150, 300, or 600 ng amounts), in reaction buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 EDTA, 15 mg/ml BSA, and 0.2 mM DTT at 25° C for 20 minutes. Reactions were stopped by adding SDS (0.5% final concentration). The samples were then diluted 1:1 with Maxam Gilbert loading buffer [80% formamide, 10 mM sodium hydroxide, 1 mM sodium EDTA, 0.1% xylene cyanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue (pH 8.0)], and aliquots were separated in 16% denaturing (7 M urea) polyacrylamide gels in TBE buffer for 2 h at 40 V/cm at 50°C. Gels were dried and visualized by using a phosphoimager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

EMSAs were performed by incubating purified human recombinant TOP1 (12.5 ng) with 200 ng amounts of GST-Par-4, GST-ΔZIP, GST-Leu.ZIP, or GST protein in standard reaction buffer [7.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 40 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5% Sucrose, 0.1% BSA, 5 ng/l poly(dI-dC).(poly(dI-dC)], for 10 min on ice. The DNA probe, a 52-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide(5′-TCTAGAGGATTTCGAAGACTTAGAGAAATTTCGAAGATCCCCGGGCGAGCTC-3′) (28, 29) containing the TOP1 binding sequence, was then added, and the reaction mix was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For competition assays, the 22-mer double-stranded oligonucleotide (5′-AAAAAGACTTGGAAAAATTTTT-3′) with the TOP1 binding sequence, or a 42-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the NF-B binding sequence (GATCCAAGGGGACTTTCCATGGATCC AAGGGGACTTTCCATG) were added in 10-fold molar excess over the amount of radiolabeled TOP1 probe. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 6× dye (0.125% bromophenol blue and 40% glycerol) to a 1× final concentration. Samples were loaded on 6% polyacrylamide (37.5:1) gels and electrophoresed at 100 V in 0.25× TBE. Products were visualized by autoradiography and phosphorimaging.

Immunocytochemistry, apoptosis, cellular transformation/colony formation assays, and cell cycle analysis

Cells in chamber slides were transfected, using Lipofectamine 2000 or Lipofectamine Plus, with the indicated plasmids or siRNAs, and subjected to immunocytochemistry, using antibodies for active caspase-3, Par-4 or TOP1, followed by staining with secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor-488 (green fluorescence) or Alexa Fluor-610 (red fluorescence) (Molecular Probes). Apoptotic nuclei were identified by TUNEL assay, caspase-3 immunostaining, or 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. A total of three independent experiments were performed; and approximately 500 cells were scored in each experiment for apoptosis under a confocal microscope, as described previously (22).

NIH 3T3/iRas cells were plated at a density of 1.6 ×105/well, in 6-well plates, transfected with control siRNA or siRNA for Par-4 or TOP1 for 24 h, and then treated with IPTG or vehicle; transformed colonies (foci) were counted after 96 h. For cell cycle analysis, BPH-1 cells were transfected with TOP1 siRNA or scrambled control siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000, or infected with Par-4-GFP or GFP adenovirus, and fixed in isopropanol. Cells in various compartments of the cell cycle were quantified by propidium iodide-based fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis at the University of Kentucky Flow Cytometry Core Facility on a BD FACSCaliber using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate to verify the reproducibility of the findings. Statistical analyses were carried out with Statistical Analysis System software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and P values were calculated using the Student t test.

Results

Par-4 binds to TOP1 via its leucine zipper domain

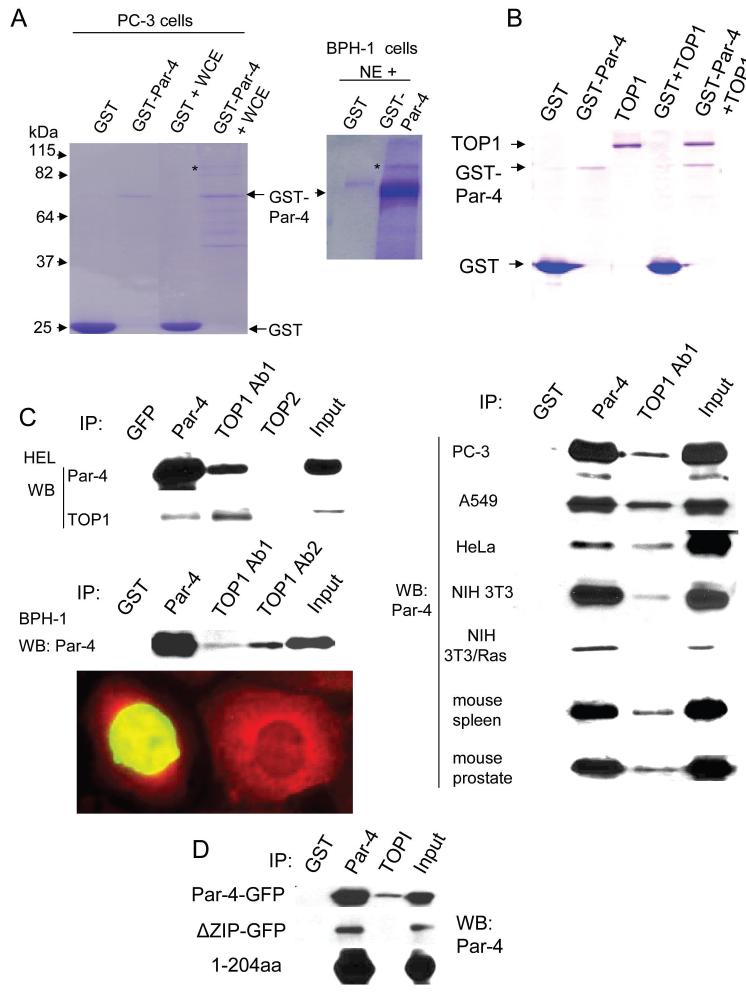

To identify proteins that interact with Par-4, we performed GST-pull down assays using whole cell extracts from PC-3 cells, and either GST-Par-4 or GST protein as bait. As seen in Figure 1A, GST-Par-4, but not GST, bound a number of proteins, and mass spectrometry identified the ∼90 kDa band (marked by the asterisk) as TOP1 (mass spectrometry data are shown in Supplemental Figure S1 and Supplemental Table 1). In view of the fact that TOP1 is a nuclear protein expressed in both non-transformed and cancer cells, we examined the interaction between Par-4 and TOP1 using nuclear extracts from non-transformed BPH-1 cells, and GST-Par-4 or GST as bait. Consistently, GST-Par-4, but not GST, bound to the ∼90 kDa protein confirmed by mass spectrometry as TOP1 (Figure 1A). To determine whether Par-4 interacted directly with TOP1, we tested the binding of GST-Par-4 or GST protein to purified TOP1 protein in GST-pull down experiments. As seen in Figure 1B, GST-Par-4 but not GST, bound TOP1, therefore implying a direct interaction between Par-4 and TOP1.

Figure 1. Par-4 binds to TOP1.

A. TOP1 in cell extracts binds to GST-Par-4 protein. Purified GST (6 μg) or GST-Par-4 (3 μg) protein was incubated with 10 μg of whole-cell extracts (WCE) of prostate cancer PC-3 cells or 5 μg of nuclear extracts (NE) of immortalized prostate epithelial BPH-1 cells for 18 h at 4°C. Proteins pulled down with the bait (which was immobilized on glutathione beads) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The protein molecular weight markers were loaded for approximate size (kDa) of the proteins (not shown). The band labeled by an * (asterisk) was identified afterward by mass spectrometry as TOP1. The protein bands for GST and GST-Par-4 are indicated by arrows.

B. GST-Par-4 binds to purified TOP1 protein in vitro. Purified GST (1 g) or GST-Par-4 (200 ng) was incubated in the presence or absence of purified TOP1 (600 ng) for 3 h, and further incubated with glutathione beads for 1 h. Bound complexes were pulled down with the beads, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The bands corresponding to each protein are indicated by arrows.

C. Endogenous Par-4 binds to endogenous TOP1 in mammalian cells. Nuclear extracts from the indicated tissues and cell lines were subjected to immunoprecipitation with Par-4 antibody, two different polyclonal antibodies for TOP1 (Ab1 from TopoGEN, Inc., and Ab2 from SantaCruz Biotechnology, Inc.), TOPII antibody, or GST control antibody. The immunoprecipitates and input were subjected to Western blot analysis for Par-4 (left panel, and upper right panel). BPH-1 cells were transiently transfected with EGFP-TOP1 expression construct, and the transfectants were examined by indirect immunofluorescence for Par-4 (Alexa Fluor-610 red fluorescence; lower right panel). Cells that were not transfected with EGFP-TOP1 (represented by the cell on the right) show Par-4 (red fluorescence) in the nucleus, as well as in the cytosol. Cells transfected with EGFP-TOP1 (represented by the cell on the left) show green fluorescence in the nucleus that partially co-localizes (yellow fluorescence) with endogenous Par-4.

D. Ectopic Par-4 binds to TOP1 in transfected cells. NIH 3T3 cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs for Par-4-GFP, ΔZIP-GFP, or 1-204aa, and subsequently subjected to immunoprecipitation with GST, Par-4, or TOP1 (Ab1) antibody. The immunoprecipitates were examined by Western blot analysis with the Par-4 antibody.

Next, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays to examine whether endogenous Par-4 interacts with TOP1 in normal tissues (spleen and prostate), as well as in various primary (HEL), immortalized (BPH-1 and NIH 3T3), Ras-transformed (NIH 3T3/Ras), and cancer (PC-3, A549, HeLa) cell lines. The NIH 3T3/Ras cells were used as control, as they express very low levels of Par-4 owing to suppression by oncogenic Ras (25)(Supplemental Figures S2). Except for the NIH 3T3/Ras cell extracts, the TOP1 antibody co-immunoprecipitated Par-4 from each of the cell line and tissue extracts; similarly, Par-4 antibody, but not the GST control or TOP2 antibodies, co-immunoprecipitated TOP1 (Figure 1C). Moreover, BPH-1 cells transfected with EGFP-TOP1 expression construct showed expression of TOP1 in the nucleus that co-localized with endogenous Par-4 (Figure 1C). Collectively, these findings indicate Par-4 binds to TOP1 both in vitro and in the nucleus of mammalian cells.

Previous studies have suggested that Par-4 interacts with its partner proteins via the carboxy-terminal leucine zipper domain. To determine if the TOP1 interaction with Par-4 requires the leucine zipper domain, whole-cell extracts from cells transfected with expression constructs for Par-4-GFP, ΔZIP-GFP or 1-204aa were examined for co-immunoprecipitation of TOP1 and ectopic Par-4 proteins. As seen in Figure 1D, the TOP1 antibody co-immunoprecipitated Par-4-GFP, but not ΔZIP-GFP or 1-204aa protein. As expected, the Par-4 antibody immunoprecipitated Par-4-GFP, ΔZIP-GFP, and 1-204aa protein, whereas the GST control antibody did not co-immunoprecipitate ectopic Par-4 proteins. These findings reveal the leucine zipper domain of Par-4 is essential for interaction with TOP1.

Par-4 sequesters TOP1 to prevent DNA relaxation and formation of CPT-induced cleavage complexes

As TOP1 is primarily involved in direct binding and relaxation of supercoiled DNA, we explored whether the interaction of Par-4 with TOP1 modulates the DNA relaxation activity of TOP1. Supercoiled DNA was incubated with TOP1 in the presence or absence of GST-Par-4, or CPT (control). As seen in Figure 2A (left panel), TOP1 caused relaxation of the supercoiled DNA, whereas GST-Par-4 inhibited TOP1-induced DNA relaxation, and maintained the DNA in its supercoiled form. In contrast, when TOP1 was used in the presence of CPT, which allows TOP1 to nick the DNA yet prevents re-ligation, the DNA lost its supercoiled form and co-migrated with the relaxed form (Figure 2A, left panel). As the recombinant proteins were purified from E. coli, we confirmed by immune-depletion experiments that the observed effects of GST-Par-4 on TOP1 activity were indeed due to GST-Par-4 in the protein preparation (Supplemental Figure S3). Importantly, the 258-332aa/ZIP mutant containing the leucine zipper domain, but neither 1-267aa/ΔZIP mutant of Par-4 nor the GST control protein, inhibited DNA relaxation by TOP1 (Figure 2A, middle panel), thereby implying the leucine zipper domain of Par-4 is essential for inhibition of TOP1 activity.

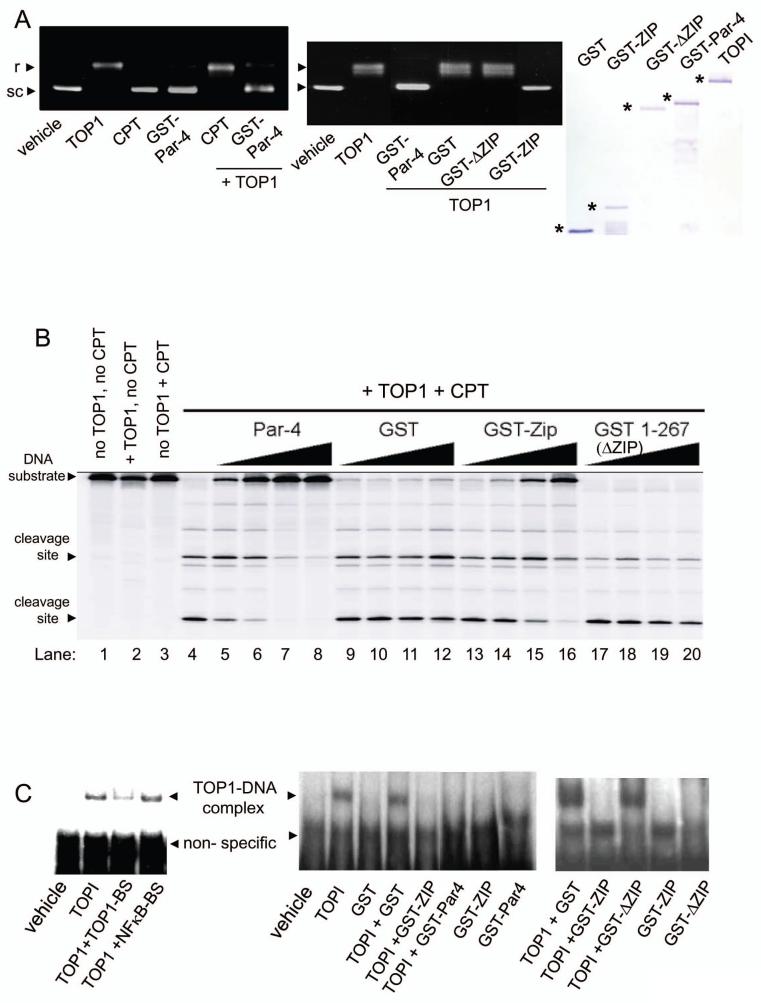

Figure 2. Recombinant Par-4 inhibits the DNA relaxation activity of TOP1 in vitro.

A. Recombinant Par-4, but not CPT, inhibits relaxation of supercoiled DNA. pUC19 supercoiled DNA (1 μg) was incubated with vehicle, TOP1 (20 ng), camptothecin (CPT, 1 μM), GST-Par-4 (200 ng) protein, or a combination of TOP1 and CPT or TOP1 and GST-Par-4 for 30 minutes at 37°C (left panel). To test the requirement of the leucine zipper domain of Par-4, pUC19 supercoiled DNA (1 μg) was incubated with vehicle, TOP1 (20 ng) alone, and TOP1 (20 ng) plus GST-Par-4, GST-ΔZIP, GST-ZIP, or GST (200 ng) protein, for 30 minutes at 37°C (middle panel). The DNA was resolved on agarose gels (without ethidium bromide), and stained with ethidium bromide. The supercoiled (sc) and relaxed (r) DNA bands are shown. The integrity of the proteins was tested by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (right panel).

B. Recombinant Par-4 inhibits CPT-induced trapping of TOP1 and formation of CPT-inducible cleavage complexes. The radiolabeled 161-bp TOP1-substrate deoxyoligonucleotide was incubated with TOP1 (50 ng) in the absence or presence of CPT (1 μM), and various amounts (75, 150, 300 and 600 ng) of GST-Par-4, GST, GST-ΔZIP, or GST-ZIP protein at 25°C for 30 min. Reactions were stopped and resolved by electrophoresis. Lanes 1-3 indicate the size of the 3′-radiolabeled deoxyoligonucleotide substrate, and Lane 4 shows the TOP1-dependent DNA fragments produced with CPT.

C. Par-4 sequesters TOP1 from its DNA interface. EMSAs were performed by incubating the radiolabeled 52-bp TOP1-substrate with (1) vehicle or TOP1 (12.5 ng) in the presence of 10× molar excess of competing unlabeled 22-bp TOP1-substrate deoxyoligonucleotide (TOP1-BS) or 42-bp NF-kappaB binding sequence (NF-kappaB-BS) (left panel), or (2) 200 ng of GST, GST-Par-4, GST-ΔZIP, or GST-ZIP alone or with TOP1 (12.5 ng) (middle and right panels). The TOP1 bound DNA complex and non-specific complex are indicated by arrows. Note the GST-Par-4 and GST-ZIP preclude the formation of the TOP1-DNA complex.

As GST-Par-4 inhibited DNA relaxation by TOP1, we tested the ability of GST-Par-4 to block the formation of TOP1-dependent DNA cleavage complexes by CPT. As demonstrated in Figure 2B, TOP1 (Lane 2) or CPT (Lane 3) alone did not form DNA cleavage complexes, yet incubation of the DNA with TOP1 and CPT (Lane 4) triggered the formation of cleavage complexes, as expected (3, 10). Incubation of the DNA with TOP1 and CPT in the presence of 75 ng of GST-Par-4 prevented the formation of cleavage complexes (Figure 2B, Lane 5); and increasing concentrations (75, 150, 300, and 600 ng) of GST-Par-4 inhibited the formation of cleavage complexes in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B, Lanes 5-8). On the other hand, 75 or 150 ng amounts of other proteins (GST, GST-ΔZIP or GST-ZIP) did not prevent the formation of the cleavage complexes (Figure 2B, Lanes 9,10,13,14,17,18). Moreover, higher concentrations, 300 or 600 ng, of GST-ZIP (Lanes 15 & 16), but not of GST or GST-ΔZIP (Lanes 11, 12, 19, 20), diminished the formation of cleavage complexes in a dose-dependent manner. These data indicate Par-4 inhibits TOP1-dependent DNA cleavage by CPT in a leucine zipper domain-dependent manner.

Par-4-mediated inhibition of both TOP1-dependent DNA relaxation and CPT-inducible, TOP1-dependent DNA cleavage complexes could be caused by either sequestration of TOP1 from the DNA, or by directly inhibiting the DNA nicking activity of TOP1 that is already bound to DNA. To elucidate the mechanism of Par-4 action, we performed EMSAs to explore whether Par-4 prevented binding of TOP1 to the DNA. As seen in Figure 2C, TOP1 formed a slowly migrating complex with the TOP1 DNA substrate (TOP1-DNA complex), and this complex was out-competed by the presence of unlabeled TOP1 binding sequence, but not by the NF-κB binding sequence, indicating specificity of the interaction of TOP1 with its DNA target. We next performed EMSAs in the presence of either GST-Par-4 or Par-4 mutants to determine if these Par-4 proteins could obstruct the formation of the TOP1-DNA complex. Neither GST-Par-4 nor the Par-4 mutants on their own directly bound to the DNA, yet GST-Par-4 and GST-ZIP, but not GST-ΔZIP or GST, inhibited the formation of the TOP1-DNA complex (Figure 2C). These data suggest Par-4 binds to TOP1, via its leucine zipper domain, and prevents TOP1 interaction with the DNA.

Endogenous Par-4 inhibits TOP1 activity

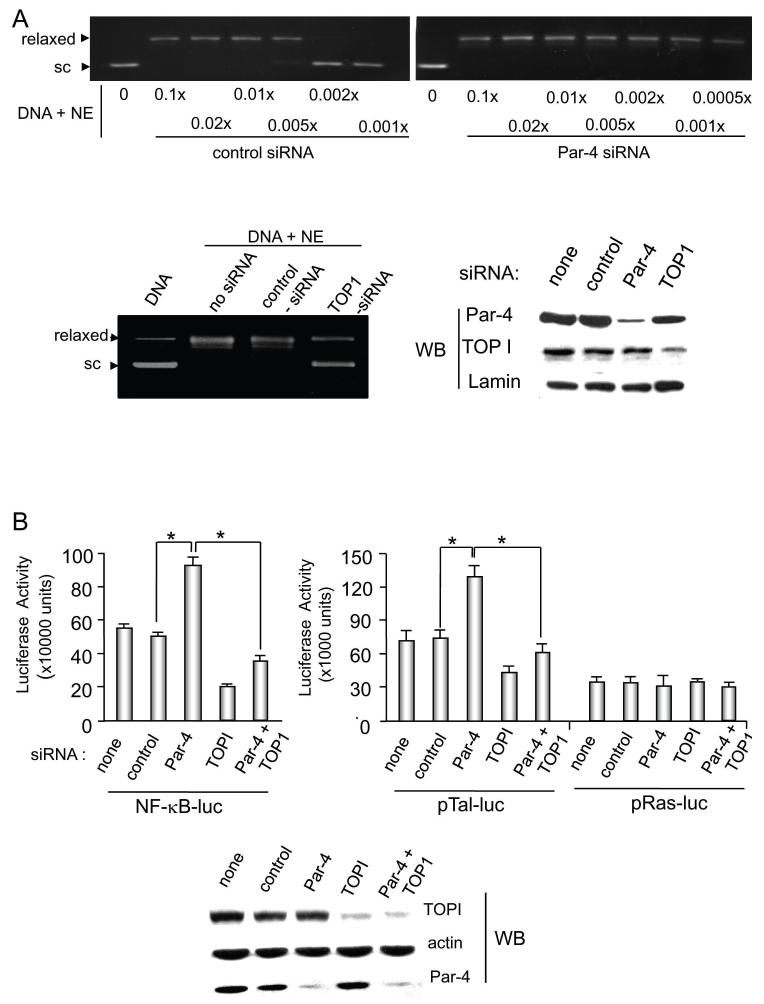

To determine whether the interaction of Par-4 and TOP1 in mammalian cells influences TOP1-driven DNA relaxation, endogenous Par-4 was knocked down in BPH-1 cells with Par-4 siRNA, and nuclear extracts were assayed via in vitro DNA relaxation assays. As seen in Figure 3A (upper panel), knockdown of Par-4 expression resulted in increased TOP1 activity in the 0.005-0.001x nuclear extracts of BPH-1 cells, implying inhibition of a functional component of the TOP1 activity in the cells by endogenous Par-4. As expected, knockdown of TOP1 with siRNA [confirmed by Western blot analysis of nuclear extracts (Figure 3A, lower right panel)] severely depleted the DNA relaxation activity in the BPH-1 nuclear extracts (Figure 3A, lower left panel), verifying that TOP1 primarily contributed to the DNA relaxation activity in the nuclear extracts. Together these findings suggest endogenous Par-4 negatively regulates the DNA relaxation activity of TOP1.

Figure 3. Par-4 attenuates TOP1 activity in mammalian cells.

A. Endogenous Par-4 knockdown with siRNA enhances TOP1 DNA relaxation. BPH-1 cells were transiently transfected with human Par-4 siRNA or control siRNA, and, following this transfection, various amounts of BPH-1 nuclear extract (NE; 0.0005X to 0.1X prepared by dilution in phosphate-buffered saline) were incubated with pUC19 supercoiled DNA (1 μg) for 30 minutes at 37°C (top panel). To ascertain whether DNA relaxation was due to TOP1, knockdown of TOP1 was performed in BPH-1 cells with TOP1 siRNA or scrambled siRNA as control, and nuclear extracts from the transfectants were incubated with pUC19 supercoiled DNA (1 μg) for 30 minutes at 37°C (lower left panel). The supercoiled and relaxed DNA bands are shown. Knockdown of Par-4 and TOP1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis of the nuclear extracts, using lamin as a loading control for nuclear protein (lower right panel).

B. Endogenous Par-4 knockdown with siRNA enhances transcription activities in mammalian cells. To study the effect of Par-4 on TOP1-dependent transcription, BPH-1 cells were left untransfected or were transiently transfected with siRNAs for control, Par-4, TOP1, or Par-4 and TOP1, and 24 h later re-transfected with pTal-luc, NF-κB-luc or Ras-luc reporter in the presence of β-galactosidase expression construct. Cell lysates were prepared after 24 h, and subjected to luciferase and β-galactosidase assays. Relative luciferase activity (normalized to corresponding β-galactosidase activity) indicates mean ± standard deviation bars of three separate experiments with three independent readings in each experiment. Asterisk (*) indicates the difference is statistically significant (P < 0.0001) by the Student’s t test. Western blot analysis of the lysates was used to confirm knockdown of the corresponding proteins (lower panel).

TOP1 activity selectively inhibits transcription from TATA-box containing promoters, but not from Inr-element containing promoters (30). As an independent means for assaying the effect of Par-4-TOP1 interaction on TOP1 activity, we therefore used the TATA-box containing pTal-luc and pTal-NF-κB constructs, or Inr-element containing Ras-promoter-luc construct to measure luciferase activity. BPH-1 cells were transfected with the reporter constructs and siRNA for Par-4, TOP1, or control, and cell extracts were used for in vitro luciferase reporter assays; untransfected cells also served as a control. Knockdown of Par-4 and TOP1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 3B, lower panel). As shown in Figure 3B, knockdown of Par-4 yielded increased reporter activity from the pTal-luc and pTal-NF-κB-luc constructs but not from pRas-luc construct, whereas knockdown of TOP1 resulted in decreased reporter activity from pTal-luc and pTal-NF-κB constructs. Importantly, concomitant knockdown of Par-4 and TOP1 significantly reduced reporter activity that was elevated following Par-4 knockdown alone (Figure 3B). Consistently, Par-4 over-expression caused over 50% inhibition of TATA-box containing constructs (pTal-luc, pTal-NF-κB-luc, pTal-AP1-luc and pTal-SRE-luc), but not Inr-element containing pRas-luc construct (Supplemental Figure S4). Thus, Par-4 abrogates TATA-box-dependent DNA transcription activity of TOP1, further confirming the functional relevance of the interaction between endogenous Par-4 and TOP1.

Reduction of TOP1 activity by Par-4 impedes S-phase progression and oncogenic transformation of mammalian cells

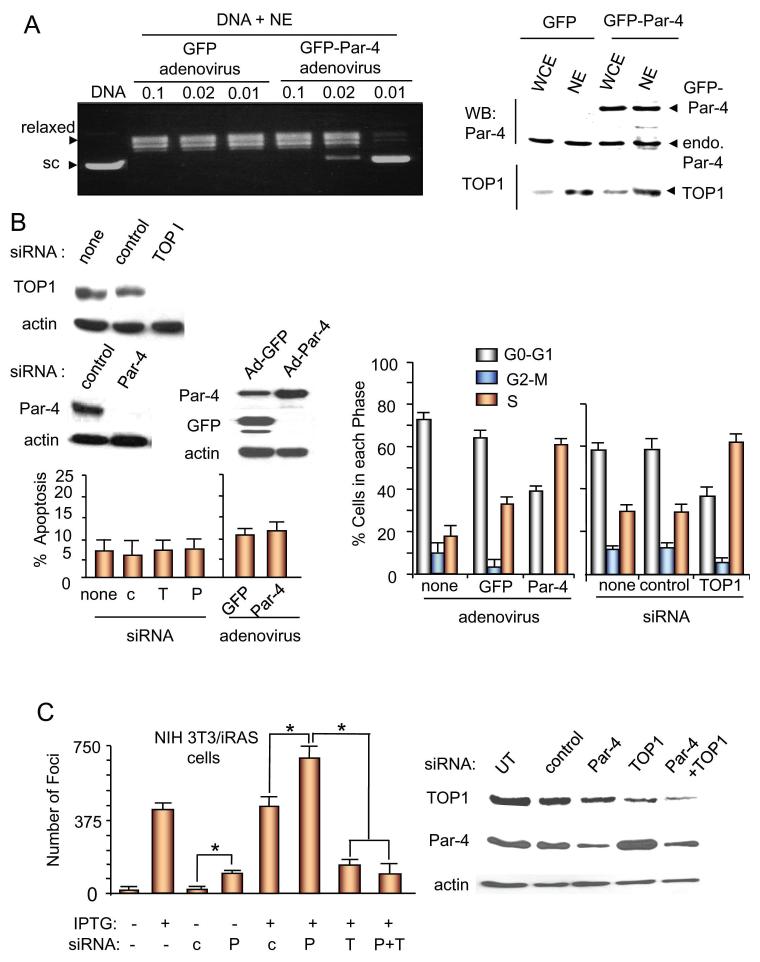

We also examined the effect of ectopic Par-4 on TOP1 by infecting BPH-1 cells with either Par-4-GFP adenovirus or GFP adenovirus (control) and testing nuclear extracts for inhibition of DNA relaxation activity. As seen in Figure 4A, Par-4-GFP over-expression did not influence the expression of endogenous TOP1 (right panel), yet extracts from Par-4-infected cells showed diminished TOP1 DNA relaxation activity (left panel); GFP-infected cells did not impact TOP1-mediated DNA relaxation activity. These data indicate over-expression of Par-4-GFP inhibits TOP1 activity, but not TOP1 expression.

Figure 4. Par-4 causes accumulation of cells in the S-phase, and prevents TOP1-dependent cellular transformation.

A. Ectopic Par-4 inhibits the relaxation of supercoiled DNA. BPH-1 cells were infected with adenoviral expression constructs for Par-4-GFP or GFP (control) for 72 hr, and whole cell extracts (WCE) or nuclear extracts (NE) were prepared from these cells. The nuclear extracts were diluted with PBS and 0.1x, 0.02x, or 0.01x diluted extracts were incubated with pUC19 supercoiled DNA (1 μg) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Controls included pUC19 supercoiled DNA incubated with vehicle or TOP1 for 30 min at 37°C. The supercoiled and relaxed DNA bands are shown (left panel). Expression of ectopic Par-4-GFP and endogenous Par-4 or TOP1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis with Par-4 or TOP1 antibody (right panel).

B. Inhibition of TOP1 by siRNA or adenoviral Par-4 inhibits cell cycle progression, but does not induce apoptosis. BPH-1 cells were left untransfected (no siRNA) or were transfected with siRNA for TOP1, Par-4, or control for 72 h, or infected with adenoviral expression constructs for Par-4-GFP or GFP (control) for 72 hr. The cells were examined for apoptosis by immunocytochemistry for caspase-3 (left panel) or subjected to propidium iodide-based FACS analysis for cell cycle progression (right panel). Expression of Par-4 or TOP1 was tested by Western blot analysis (top left panel).

C. Par-4 curtails TOP1-dependent cellular transformation. NIH 3T3/iRas cells were transiently transfected with siRNA for Par-4 (P), TOP1 (T), or control (c) as indicated, and then treated or left untreated with IPTG to induce oncogenic Ras. Transformed colonies (foci) were scored 96 h after IPTG treatment. Mean values (± standard deviation bars) of three separate experiments are shown. Asterisk (*) indicates the difference is statistically significant (P < 0.0001) by the Student’s t test. Knockdown of Par-4 or TOP1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (right panel).

As the DNA relaxation activity of TOP1 is essential for DNA replication and S-phase progression (31), we examined possible Par-4 regulation of TOP1-dependent cell cycle progression and apoptosis in BPH-1 cells. As seen in Figure 4B, siRNA-mediated knockdown of TOP1 or over-expression of adenoviral Par-4 caused S-phase arrest, but not apoptosis, of BPH-1 cells. Together with the foregoing observations, these findings imply reduction of TOP1 activity by Par-4 hampers S-phase progression of proliferating cells.

As Par-4 is a tumor suppressor protein that inhibits oncogenic transformation of cells, we examined whether inhibition of TOP1-dependent DNA relaxation by endogenous Par-4 could explain the tumor suppressor function of Par-4, by specifically testing the effect of Par-4 and TOP1 knockdown on cellular transformation. Knockdown of Par-4 with siRNA in NIH 3T3/iRas cells in the absence of oncogenic Ras induction by IPTG resulted in approximately 5-fold increase in the formation of transformed colonies (foci) over NIH 3T3/iRas cells expressing normal endogenous levels of Par-4 following transfection with control siRNA (Figure 4C). Interestingly, induction of oncogenic Ras with IPTG (which causes suppression of Par-4 expression, Supplemental Figure S2) produced a sharp increase in the number of foci, and the frequency of foci formation was further enhanced by concomitant Par-4 knockdown in these corresponding cells (Figure 4C). Conversely, knockdown of TOP1 suppressed foci formation by oncogenic Ras (Figure 4C). Importantly, concurrent knockdown of Par-4 and TOP1 resulted in significantly fewer foci relative to those observed with Par-4 knockdown (Figure 4C). The foci with oncogenic Ras expression or Par-4 knock down were of similar size and morphology; however, the foci were approximately 50% smaller in size and relatively less compact when TOP1 was knocked down (data not shown). Collectively, these results imply 1) TOP1 is essential for cellular transformation, and 2) Par-4 suppresses transformation by inhibition of TOP1 function.

Discussion

Although Par-4 is broadly expressed in normal and cancer cells, its normal cellular function has remained unclear since it does not contain a conserved domain for biochemical activity that might provide a clue about its endogenous function (17). Of the two conserved domains of Par-4, the central SAC domain is involved in the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells and is inactive in normal cells, whereas the carboxy-terminal leucine zipper domain is involved in protein-protein interactions with proteins of diverse functions, including PKC, ZIP kinase, and Akt1, which regulate cell survival/apoptosis (32, 33), and WT1, which regulates gene transcription (27, 34). Excepting the interaction of Par-4 with the tissue-specific protein WT1, which identifies Par-4 as a transcriptional co-repressor in certain cellular contexts (27, 34), none of the previously identified interactions have uncovered the general biochemical function of Par-4. The present study has identified TOP1, a protein that is essential for the fundamental biological process of DNA relaxation (1, 3, 4), as a binding partner of Par-4 in normal, immortalized, and cancer cells. Consistent with the fact that DNA relaxation is an integral component of cell function and its complete inhibition leads to loss of cell viability (5, 6), the interaction of endogenous Par-4 with TOP1 in normally growing cells is adequate to reduce, but not completely suppress, TOP1 activity. Unlike CPT, which inhibits TOP1 by inducing the formation of TOP1 cleavage complexes (3, 10), and tumor suppressor proteins (p53, ARF, and NKX3.1), which interact with TOP1 to enhance its function (35, 36, 37), Par-4 sequesters TOP1 from its DNA substrate, thereby regulating its access to the DNA. Given that unrestricted TOP1 access to DNA contributes to aberrations in DNA replication, transcription, and recombination, thereby leading to illegitimate recombination events and genomic instability (38), regulation of TOP1 activity by Par-4 functions as a genomic safeguard. Consistent with this rationale, Par-4 knockout mice grow tumors in diverse tissues (20), and Par-4 knockdown in cell culture leads to cellular transformation in a TOP1-dependent manner (Figure 4C). Thus, this study identifies Par-4 as an essential attenuator of TOP1 activity.

Par-4 interaction with TOP1 via its leucine zipper domain does not induce apoptosis

Par-4 and its central SAC domain induce apoptosis in cancer cells, but not in normal cells, thus the carboxy-terminal leucine zipper domain is entirely dispensable for apoptosis (17, 18, 39). In fact, the presence of the leucine zipper domain compromises Par-4 function in cancer cells, as it allows Akt1 to interact with Par-4 and sequester Par-4 from its nuclear targets (22), although Par-4 activity does persist in normal/immortalized and cancer cells despite Akt1-mediated sequestration (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure S5). Previous reports have shown that TOP1 shuttles dynamically between the nucleoplasm and nucleolus (40), and our studies demonstrate co-localization of TOP1 and Par-4 in the nucleoplasm. Par-4 binds to TOP1 in both normal and cancer cells, and this interaction is mediated by the leucine zipper domain; the leucine zipperless mutant of Par-4 (ΔZIP), which contains the apoptosis-effector SAC domain, fails to interact with TOP1. Moreover, in agreement with previous findings (31), knockdown of TOP1 in normal or cancer cells by RNA-interference or by adenoviral Par-4 induces S-phase accumulation of the cells, but not apoptosis (Figure 4B and Supplemental Figure S5). Consistent with the possibility that TOP1 inactivation precludes apoptosis, TOP1 cleavage complexes are induced by a variety of apoptotic inducers (41-43). Thus, the interaction between Par-4 and TOP1 may not be sufficient to induce apoptosis.

Par-4 regulates DNA relaxation activity of TOP1 and guards against cellular transformation

It is noteworthy that unlike other tumor suppressor proteins such as p53, ARF, and NKX3.1 (35-37), which bind TOP1 at its DNA interface and promote its DNA relaxation activity, Par-4 sequesters TOP1 from the DNA. Thus, unlike the aforementioned tumor suppressors, which are hypothesized to play a role in DNA repair following TOP1/DNA interactions, Par-4 may function to prevent TOP1-dependent DNA damage induced by chemotherapeutic agents and ultra violet irradiation.

TOP1 exhibits both DNA nicking and DNA re-ligation activities essential for DNA relaxation. The process of DNA relaxation by TOP1 involves binding of TOP1 to the DNA, nicking a single strand as an intermediate step in the relaxation cycle to form the cleavage complex, and finally re-ligating the DNA. Control of the superhelical and relaxed DNA topology is critical during replication and transcription: lack of coordinated TOP1 activity may cause the accumulation of negatively/positively supercoiled regions behind/ahead of the replication and transcription machineries, thus resulting in genomic instability (31). Because slight perturbations could lead to aberrant phenotypes, it is essential the process of DNA relaxation is tightly controlled. In view of this observation, segregating TOP1 from DNA to block TOP1-dependent DNA relaxation could, in principle, result in genomic perturbations, particularly if TOP1 sequestration is not adequately fine-tuned. As endogenous Par-4 reduces, but does not completely abrogate, the DNA relaxation function of TOP1 in normal cells, this action of Par-4 does not result in aberrant phenotypic outcomes. However, since the impact of TOP1 sequestration may be cell type- and/or context-dependent, we examined whether TOP1 or Par-4 knockdown itself caused cellular transformation. Interestingly, we noted that TOP1 knockdown prevented transformation of cells by oncogenic Ras, whereas Par-4 knockdown enhanced oncogenic Ras-mediated transformation, which was in turn prevented by concurrent Par-4 and TOP1 knockdown. These findings imply sequestration of TOP1 by Par-4 to regulate DNA relaxation is a well orchestrated physiological process, and does not generate anomalous outcomes. Indeed, this study showed the regulatory process prevents the emergence of a TOP1-dependent transformed phenotype.

During tumorigenesis, expression of the Par-4 gene is silenced by DNA methylation, as in Ras transformed cells (44), or inactivated by mutation, such as the insertion of a stop codon in the SAC domain (21) In addition, Par-4 protein is inactivated in cancer cells by phosphorylation by Akt1, and subsequent 14-3-3-mediated sequestration of Par-4 in the cytoplasm (22). Consistent with these observations, TOP1 activity is generally elevated in transformed cells. For instance, NIH 3T3/Ras transformed cells show diminished expression of Par-4 (Supplemental Figure S2) and negligible interaction between Par-4 and TOP1 (Figure 1C), and express over 30-fold higher TOP1 activity relative to parental NIH 3T3 cells (45). These observations suggest inactivation of Par-4 function contributes to higher TOP1 activity in cancer cells. Accordingly, although Par-4 may bind to TOP1 in cancer cell lines (HeLa, A549, PC-3) as noted in this study, excessive TOP1 activity in the cells apparently overrides the regulatory consequences of this interaction.

The present study has identified a novel mechanism of TOP1 regulation: Par-4-mediated binding and sequestration of TOP1, an interaction that reduces the TOP1 DNA relaxation potential without causing perturbations in normal cell function. This interaction also serves as regulatory mechanism to prevent TOP1-dependent cellular transformation. Importantly, due to the inactivation of Par-4, TOP1 activity is higher in transformed cells relative to corresponding normal/immortalized progenitor cells; this phenomenon may explain their transformed phenotype. Thus, Par-4 functions as an essential biological response modifier of intra-nuclear TOP1 for normal cellular activity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NCI grants CA60872, CA105453, and CA84511 (to VMR).

References

- 1.Champoux JJ. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koster DA, Palle K, Bot ES, et al. Antitumour drugs impede DNA uncoiling by topoisomerase I. Nature. 2007;448:213–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pommier Y. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:789–802. doi: 10.1038/nrc1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JC. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MP, Brown SD, Chen A, Hsieh TS. DNA topoisomerase I is essential in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6656–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morham SG, Kluckman KD, Voulomanos N, Smithies O. Targeted disruption of the mouse topoisomerase I gene by camptothecin selection. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6804–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwong CL, Chen CY, Shang HF, Hwang J. Increased synthesis and degradation of DNA topoisomerase I during the initial phase of human T lymphocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18982–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tricoli JV, Sahai BM, McCormick PJ, et al. DNA topoisomerase I and II activities during cell proliferation and the cell cycle in cultured mouse embryo fibroblast (C3H 10T1/2) cells. Exp Cell Res. 1985;158:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(85)90426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen AK, Gobert C. DNA topoisomerase I in oncology: Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? Pathol Oncol Res. 1999;5:171–8. doi: 10.1053/paor.1999.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsiang YH, Hertzberg R, Hecht S, Liu LF. Camptothecin induces protein-linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14873–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu J, Schiestl RH. Human topoisomerase I mediates illegitimate recombination leading to DNA insertion into the ribosomal DNA locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;271:347–58. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-0987-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laine JP, Opresko PL, Indig FE, et al. Werner protein stimulates topoisomerase I DNA relaxation activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7136–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lebel M, Spillare EA, Harris CC, Leder P. The Werner syndrome gene product co-purifies with the DNA replication complex and interacts with PCNA and topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37795–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sells SF, Wood DP, Jr, Joshi-Barve SS, et al. Commonality of the gene programs induced by effectors of apoptosis in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:457–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boghaert ER, Sells SF, Walid AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of the proapoptotic protein Par-4 in normal rat tissues. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:881–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook J, Krishnan S, Ananth S, et al. Decreased expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Par-4 in renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 1999;18:1205–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Guendy N, Zhao Y, Gurumurthy S, et al. Identification of a unique core domain of par-4 sufficient for selective apoptosis induction in cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5516–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5516-5525.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurumurthy S, Goswami A, Vasudevan KM, Rangnekar VM. Phosphorylation of Par-4 by protein kinase A is critical for apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1146–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1146-1161.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu G, Ahmed M, Sells SF, et al. Mutually exclusive expression patterns of Bcl-2 and Par-4 in human prostate tumors consistent with down-regulation of Bcl-2 by Par-4. Oncogene. 1999;18:623–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Cao I, Duran A, Collado M, et al. Tumour-suppression activity of the proapoptotic regulator Par4. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:577–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno-Bueno G, Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Collado M, et al. Inactivation of the candidate tumor suppressor par-4 in endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1927–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goswami A, Burikhanov R, de Thonel A, et al. Binding and phosphorylation of par-4 by akt is essential for cancer cell survival. Mol Cell. 2005;20:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Burikhanov R, Qiu S, et al. Cancer resistance in transgenic mice expressing the SAC module of Par-4. Cancer Research. 2007;67:9276–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nalca A, Qiu SG, El-Guendy N, et al. Oncogenic Ras sensitizes cells to apoptosis by Par-4. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29976–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu SG, Krishnan S, el-Guendy N, Rangnekar VM. Negative regulation of Par-4 by oncogenic Ras is essential for cellular transformation. Oncogene. 1999;18:7115–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mo YY, Wang C, Beck WT. A novel nuclear localization signal in human DNA topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41107–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnstone RW, See RH, Sells SF, et al. A novel repressor, par-4, modulates transcription and growth suppression functions of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor WT1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6945–56. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrell A, Placzek M, Parmley S, et al. Nitrated indenoisoquinolines as topoisomerase I inhibitors: a systematic study and optimization. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4419–30. doi: 10.1021/jm070361q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strumberg D, Pommier Y, Paull K, et al. Synthesis of cytotoxic indenoisoquinoline topoisomerase I poisons. J Med Chem. 1999;42:446–57. doi: 10.1021/jm9803323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merino A, Madden KR, Lane WS, Champoux JJ, Reinberg D. DNA topoisomerase I is involved in both repression and activation of transcription. Nature. 1993;365:227–32. doi: 10.1038/365227a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miao ZH, Player A, Shankavaram U, et al. Nonclassic functions of human topoisomerase I: genome-wide and pharmacologic analyses. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8752–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz-Meco MT, Lallena MJ, Monjas A, et al. Inactivation of the inhibitory kappaB protein kinase/nuclear factor kappaB pathway by Par-4 expression potentiates tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19606–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diaz-Meco MT, Municio MM, Frutos S, et al. The product of par-4, a gene induced during apoptosis, interacts selectively with the atypical isoforms of protein kinase C. Cell. 1996;86:777–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheema SK, Mishra SK, Rangnekar VM, et al. Par-4 transcriptionally regulates Bcl-2 through a WT1-binding site on the bcl-2 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19995–20005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowen C, Stuart A, Ju JH, et al. NKX3.1 homeodomain protein binds to topoisomerase I and enhances its activity. Cancer Res. 2007;67:455–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karayan L, Riou JF, Seite P, et al. Human ARF protein interacts with topoisomerase I and stimulates its activity. Oncogene. 2001;20:836–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao Y, Okada S, Chang LS, Muller MT. p53 dependence of topoisomerase I recruitment in vivo. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4538–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pommier Y, Jenkins J, Kohlhagen G, Leteurtre F. DNA recombinase activity of eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase I; effects of camptothecin and other inhibitors. Mutat Res. 1995;337:135–45. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00019-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakraborty M, Qiu SG, Vasudevan KM, Rangnekar VM. Par-4 drives trafficking and activation of Fas and Fasl to induce prostate cancer cell apoptosis and tumor regression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7255–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen MO, Barthelmes HU, Boege F, Mielke C. The N-terminal domain anchors human topoisomerase I at fibrillar centers of nucleoli and nucleolar organizer regions of mitotic chromosomes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35932–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sordet O, Khan QA, Plo I, et al. Apoptotic topoisomerase I-DNA complexes induced by staurosporine-mediated oxygen radicals. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50499–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sordet O, Khan QA, Pommier Y. Apoptotic topoisomerase I-DNA complexes induced by oxygen radicals and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1095–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sordet O, Liao Z, Liu H, et al. Topoisomerase I-DNA complexes contribute to arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33968–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404620200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pruitt K, Ulku AS, Frantz K, et al. Ras-mediated loss of the pro-apoptotic response protein Par-4 is mediated by DNA hypermethylation through Raf-independent and Raf-dependent signaling cascades in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23363–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohira T, Nishio K, Kanzawa F, et al. Hypersensitivity of NIH3T3 cells transformed by H-ras gene to DNA-topoisomerase-I inhibitors. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:702–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960904)67:5<702::AID-IJC19>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]