Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress may cause gastrointestinal cancers. The evidence on whether antioxidant supplements are effective in preventing gastrointestinal cancers is contradictory.

Objectives

To assess the beneficial and harmful effects of antioxidant supplements in preventing gastrointestinal cancers.

Search methods

We identified trials through the trials registers of the four Cochrane Review Groups on gastrointestinal diseases, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 2007), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, SCI‐EXPANDED, and The Chinese Biomedical Database from inception to October 2007. We scanned reference lists and contacted pharmaceutical companies.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing antioxidant supplements to placebo/no intervention examining occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (GB and DN) independently selected trials for inclusion and extracted data. Outcome measures were gastrointestinal cancers, overall mortality, and adverse effects. Outcomes were reported as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) based on random‐effects and fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis. Meta‐regression assessed the effect of covariates across the trials.

Main results

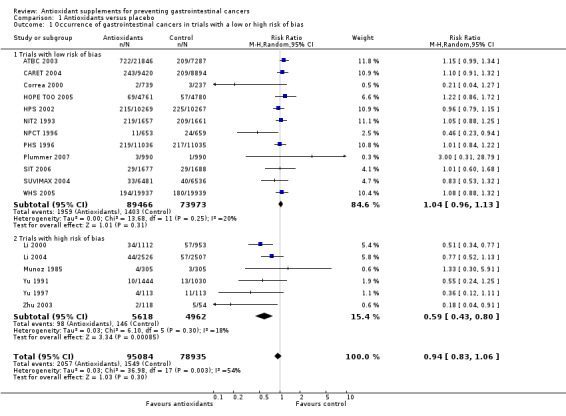

We identified 20 randomised trials (211,818 participants), assessing beta‐carotene (12 trials), vitamin A (4 trials), vitamin C (8 trials), vitamin E (10 trials), and selenium (9 trials). Trials quality was generally high. Heterogeneity was low to moderate. Antioxidant supplements were without significant effects on gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.06). However, there was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 54.0%, P = 0.003). The heterogeneity may have been explained by bias risk (low‐bias risk trials RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.13 compared to high‐bias risk trials RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.80; test of interaction P < 0.0005), and type of antioxidant supplement (beta‐carotene potentially increasing and selenium potentially decreasing cancer risk). The antioxidant supplements had no significant effects on mortality in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.07, I2 = 53.5%), but significantly increased mortality in a fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis (RR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.07). Beta‐carotene in combination with vitamin A (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.23) and vitamin E (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.11) significantly increased mortality. Increased yellowing of the skin and belching were non‐serious adverse effects of beta‐carotene. In five trials (four with high risk of bias), selenium seemed to show significant beneficial effect on gastrointestinal cancer occurrence (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.75, I2 = 0%).

Authors' conclusions

We could not find convincing evidence that antioxidant supplements prevent gastrointestinal cancers. On the contrary, antioxidant supplements seem to increase overall mortality. The potential cancer preventive effect of selenium should be tested in adequately conducted randomised trials.

Keywords: Humans, Dietary Supplements, Dietary Supplements/adverse effects, Antioxidants, Antioxidants/administration & dosage, Antioxidants/adverse effects, Gastrointestinal Neoplasms, Gastrointestinal Neoplasms/mortality, Gastrointestinal Neoplasms/prevention & control, Liver Neoplasms, Liver Neoplasms/mortality, Liver Neoplasms/prevention & control, Pancreatic Neoplasms, Pancreatic Neoplasms/mortality, Pancreatic Neoplasms/prevention & control, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Antioxidant supplements cannot be recommended for gastrointestinal cancer prevention

Our body cannot synthesize all compounds that are essential for health. Therefore such compounds must be taken through diet. Oxidative stress may cause cell damage that is implicated in chronic diseases like cancer. Gastrointestinal cancers are among the most common cancers worldwide. The poor prognosis of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancers made primary prevention a potentially attractive approach. The evidence on whether antioxidant supplements are effective in decreasing gastrointestinal cancers is contradictory.

In this review prevention with antioxidant supplements of oesophageal, gastric, small intestinal, colorectal, pancreatic, liver, and biliary tract cancers is assessed. The review includes 20 randomised clinical trials. In total, 211,818 participants were randomised to antioxidant supplements (beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium) versus placebo. Trial quality was exceptionally good.

Based on properly designed and conducted randomised clinical trials, convincing evidence that beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin E or their combinations may prevent gastrointestinal cancers is not found. A total of 2057 of 95084 participants (2.2%) randomised to antioxidant supplements and 1548 of 78935 participants (2.0%) randomised to placebo developed gastrointestinal cancers. These antioxidant supplements even seem to increase mortality. A total of 17114 of 122,501 participants (14.0%) randomised to antioxidant supplements and 8799 of 78693 participants (11.2%) randomised to placebo died. Selenium alone may have preventive effects on gastrointestinal cancers. This finding, however, is based on trials with flaws in their design and needs confirmation in properly conducted randomised clinical trials.

Background

Our body cannot synthesize all compounds that are essential for health. Therefore they must be taken through diet. Oxidative stress may cause cell damage that is implicated in chronic diseases like cancer (Sies 1985; Ames 1995). Antioxidants are compounds that can protect against oxidative stress (Diplock 1994; Poppel 1997; Papas 1999; Tamimi 2002; Willcox 2004). Laboratory and epidemiologic studies suggest a role of antioxidants in cancer prevention (Schrauzer 1977; Peto 1981). The possibility to improve health and prevent diseases by ameliorating excessive oxidative stress has attracted the attention of researchers in the last decades (Willcox 2004). Even though a healthy diet provides a sufficient amount of antioxidants, there are a number of people who regularly take antioxidant supplements (Balluz 2000; Millen 2004; Radimer 2004; Lichtenstein 2005; Nichter 2006).

Gastrointestinal cancers Gastrointestinal cancers are among the most common cancers and the leading cause of cancer death worldwide (Ferlay 2004). The poor prognosis of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancers made chemoprevention an attractive approach. It is, therefore, understandable that antioxidant prevention of gastrointestinal cancers has drawn much attention (Garcea 2003; Sharma 2004; Grau 2006).

Oesophageal cancer is characterized by low likelihood of cure (Enzinger 2003). Prevention is complicated by the fact that the two major histologic types, ie, squamous‐cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, differ substantially (Fitzgerald 2006; Holmes 2007). The role of oxidative stress in the aetiology of two histological types of oesophageal cancer is unclear (Tzonou 1996; Terry 2000; Mayne 2001). Antioxidants were discussed as protective agents in studies of oesophageal squamous‐cell carcinoma as well as Barrett's oesophagus, a precancerous condition for oesophageal adenocarcinoma (Cheng 1996; Terry 2000; Sihvo 2002; Mehta 2005; Stoner 2007).

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer death in the world (Ferlay 2004). Helicobacter pylori is the important aetiological agent of gastric cancer (Sugiyama 2004). Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and chemoprevention with antioxidants emerged as alternative strategies in reducing the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer (Leung 2006; SIT 2006; Plummer 2007).

Small intestinal cancers are rare (Neugut 1998), and prevention with antioxidant supplements has, according to our knowledge, not been extensively tested.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide (Ferlay 2004). It develops in multiple steps (Potter 1999). Most colorectal cancers arise from adenomas, as a result of a series of molecular changes that transform normal colonic epithelial cells into colorectal cancer (Janne 2000; Lynch 2002). The transition from normal mucosa to carcinoma offer opportunities for prevention (Gwyn 2002). Observational studies postulate that diet may be associated with colorectal cancer. A diet rich in antioxidants is claimed to be able to lower the risk of colorectal cancer (Boyle 1985; Bostick 1993; Kune 2006). Antioxidants were the first agents evaluated in prevention of colorectal cancer (Grau 2006). However, antioxidant supplements have no significant effect on primary or secondary prevention of colorectal adenoma (Bjelakovic 2006).

Pancreatic cancer has a poor prognosis. Possible aetiologic factors for pancreatic cancer include chronic pancreatitis, smoking, diabetes, and other medical conditions (Lowenfels 2006). Chronic inflammation, resulting in chronic phagocytic activity, one of the major endogenous sources of free radicals, is associated with cancer of several organs (Collins 1987; Shimoda 1994; Holzinger 1999). Experimental and observational studies have shown that antioxidants might be effective in the prevention of pancreatic cancer (Doucas 2006).

Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence has increased over the last decades. Cirrhosis and aflatoxins are the main risk factors for its development (Yates 2007). Viral or chemical damage to the liver results in oxidative damage that may inhibit apoptosis and promote hepatocarcinogenesis (Patel 1998; Tabor 1999; MacDonald 2001; Sasaki 2006). The liver is well endowed with antioxidant mechanisms to combat oxidative stress, including micronutrients, such as vitamin E and vitamin C, and some enzymes that metabolise reactive metabolites and reactive oxygen species (Kaplowitz 2000). Whether additional antioxidant supplements could be beneficial is not clear.

The role of antioxidant supplements in preventing biliary tract cancers is not sufficiently investigated. There are only a few experimental studies dealing with this question (Takeda 2002).

Antioxidant supplements Vitamin A is essential for growth. Since cancer involves disturbances in normal tissue growth and differentiation, it was one of the first vitamins to be evaluated with respect to carcinogenesis. Later studies indicated that protective effects were only observed for dietary vitamin A from plant sources (beta‐carotene) (Peto 1981; Ziegler 1989). Vitamin C has antioxidative properties with possible cancer preventive potential (Hanck 1988). Vitamin E acts as a free radical scavenger to prevent lipid peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and block nitrosamine formation (Oshima 1982; Poppel 1997). Vitamin E supplementation can increase production of humoral antibodies and may have antitumour proliferation capacities, possibly by modulating gene expression (Knekt 1994). Selenium, a trace element, is also important for antioxidant defences of the body as an integral component of metalloprotein enzymes. It is a component of selenoproteins, which have important enzymatic functions (Hughes 2000; Rayman 2000). There is an inverse relationship between selenium intake and cancer mortality (Schrauzer 1977). In the USA, cancer mortality rates are significantly higher in low selenium regions (Clark 1991).

The evidence on whether antioxidant supplements are effective in decreasing gastrointestinal cancers is contradictory (Nomura 1987; Dawsey 1994; Yu 1997). We conducted a systematic Cochrane review on the issue published in 2004 and were unable to demonstrate convincing beneficial effects of antioxidant supplements (beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium) on gastrointestinal cancers (Bjelakovic 2004a; Bjelakovic 2004b). Our results even suggested that these supplements, with the possible exception of selenium, may increase mortality (Bjelakovic 2004a; Bjelakovic 2004b). This present review is an update of the former review.

Objectives

To assess the beneficial and harmful effects of antioxidant supplements in preventing gastrointestinal cancers (oesophageal, gastric, small intestine, colorectal, pancreatic, liver, and biliary tract cancers).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised trials, irrespective of blinding, publication status, publication year, or language.

Types of participants

Adult participants (age 18 years or over) who were:

participants from the general population irrespective of age, sex, or ethnic origin; or

participants at high risk of developing gastrointestinal cancers (with premalignant conditions, or living in areas with high incidence of gastrointestinal cancers); or

participants coming from other patient groups, primarily with non‐gastrointestinal diseases.

Types of interventions

We considered for inclusion trials that compared antioxidant supplements (ie, beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium) at any dose, duration, and route of administration versus placebo or no intervention.

The antioxidants could have been administered:

singly; or

in any combination among themselves; or

in combination with other vitamins; or

in combination with trace elements without antioxidant function.

Concomitant interventions were allowed if used equally in both intervention arms of the trial.

Studies concerning antioxidant supplements in prevention of other organ system disease (cardiovascular, respiratory, urinary tract, etc.) were considered if data on the occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers during the trial could be obtained.

Types of outcome measures

Our primary outcome measures were: (1) Number of patients developing gastrointestinal cancers. We determined whether supplementation with antioxidants, administered separately or in combination, influenced the incidences of any of the gastrointestinal cancers (oesophageal, gastric, small intestinal, colorectal, pancreatic, liver, and biliary tract cancers) and all gastrointestinal cancers combined. (2) Overall mortality.

Our secondary outcome measures were: (3) Any adverse effects as reported in the trials. Incidence and types of adverse effects connected with the active intervention. (4) Quality‐of‐life measures. (5) Health economics.

Search methods for identification of studies

The trials search co‐ordinators of The Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group, The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group, The Cochrane Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group, and The Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group provided us with searches of their respective trials registers on antioxidant supplements and prevention of oesophageal, gastric, small intestinal, colorectal, pancreatic, liver, and biliary tract cancers. We also conducted electronic searches in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 2007), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2007), EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database) (1985 to October 2007), LILACS (1982 to October 2007), the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) (1945 to October 2007) (Royle 2003). All search strategies are given in Table 1. In addition, we obtained a search result in the Chinese Biomedical Database (1978 to October 2007).

1. Table.

| Database | Search performed | Search strategy |

| The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on the Cochrane Library | October 2007 | Digestive system neoplasms / explode all trees (MeSH), antioxidants / explode all trees (MeSH), (#1 and #2). |

| The Controlled Trials Registers of the four Cochrane gastrointestinal groups | October 2007 | 'oesophageal cancer' or 'gastric cancer' or 'stomach cancer' or 'bowel cancer' or 'colorectal cancer' or 'colon cancer' or 'rectal cancer' or 'pancreatic cancer' or 'hepatocellular carcinoma' or 'liver cancer' or 'biliary tract cancer' AND 'antioxidant*' or 'vitamin* and supplement* and random*'. |

| MEDLINE | October 2007 | #1 explode "Digestive‐System‐Neoplasms"/ all subheadings #2 retinol or beta carotene or ascorbic acid or alpha tocopherol or selenium or vitamin* or antioxidant* #3 TG = ANIMAL #4 random* #5 ((#1 and #2) not #3) and random* |

| EMBASE | October 2007 | #1 explode "digestive‐system‐tumor"/ all subheadings #2 retinol or beta carotene or ascorbic acid or alpha tocopherol or selenium or vitamin* or antioxidant* #3 random* #4 #1 and #2 and #3 |

| LILACS | October 2007 | #1 antioxidantes and cancer |

| The Web of Science (http://portal.isiknowledge.com/portal.cgi?DestApp=WOS&Func=Frame) | Accessed 01 October 2007 | #1 ‐ > [TS=(retinol or beta‐carotene or ascorbic acid or alpha tocopherol or selenium or vitamin* or antioxidant*) DocType=All document types; Language=All languages; Database(s)=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan=1945‐2003] #2 ‐ ((o)esophageal or gastric or small intestin* or colorectal or pancreatic or liver or biliary tract) and cancer* #3 ‐ > TS=(random*) DocType=All document types; Language=All languages; Database(s)=SCI‐EXPANDED; Timespan = 1945‐2003 #4 ‐ 62 #1 and #2 and #3 |

| The Chinese Biomedical Database | October 2007 | (retinol or beta‐carotene or ascorbic acid or alpha tocopherol or selenium or vitamin* or antioxidant*) and #1 ((o)esophageal or gastric or small intestin* or colorectal or pancreatic or liver or biliary tract) and cancer* |

We scanned reference lists from review articles retrieved from the searches above in order to identify additional trials.

We contacted DSM, Roche, Bristol‐Meyers Squibb, BASF AIS, Hoechst, Bayer, Aventis, Takeda, and Lederle Laboratories, manufacturers of antioxidant supplements, to ask for unpublished randomised trials. Of these, Roche suggested some published trials, which we knew of. No other information was received.

Data collection and analysis

Inclusion criteria application We retrieved the identified material for assessment. GB and DN independently applied the inclusion criteria to all potential studies. We performed this without blinding. No discrepancy occurred in the trial selection.

Data extraction Participant characteristics, diagnosis, and interventions We recorded the following data from the individual randomised trials: first author; country of origin; country income category (low, middle, high) (World Bank 2006); number of participants; characteristics of participants: age range (mean or median) and sex ratio; participation rate; dropout rate; trial design (parallel or factorial); type of antioxidant; dose; duration of supplementation; duration of follow‐up (ie, duration of intervention plus post‐intervention follow‐up); co‐interventions; and the occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers (oesophageal, gastric, small intestinal, colorectal, pancreatic, liver, and biliary tract cancers).

Trial characteristics We recorded the date, location, sponsor of the trial (known or unknown and type of sponsor) as well as publication status.

Assessment of methodological quality We assessed the methodological quality defined as the confidence that the design and report restrict bias in the intervention comparison based on the randomisation, blinding, and follow‐up (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001). The following definitions were used: Generation of the allocation sequence

Adequate, if the allocation sequence was generated by a computer or random number table. Drawing of lots, tossing of a coin, shuffling of cards, or throwing dice was considered as adequate if a person who was not otherwise involved in the recruitment of participants performed the procedure.

Unclear, if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used for the allocation sequence generation was not described.

Inadequate, if a system involving dates, names, or admittance numbers were used for the allocation of patients.

Allocation concealment

Adequate, if the allocation of patients involved a central independent unit, on‐site locked computer, identically appearing numbered drug bottles or containers prepared by an independent pharmacist or investigator, or sealed envelopes.

Unclear, if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used to conceal the allocation was not described.

Inadequate, if the allocation sequence was known to the investigators who assigned participants or if the study was quasi‐randomised.

Blinding (or masking)

Adequate, if the trial was described as double blind and the method of blinding involved identical placebo or active drugs.

Unclear, if the trial was described as double blind, but the method of blinding was not described.

Not performed, if the trial was not double blind.

Follow‐up

Adequate, if the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in all intervention groups were described or if it was specified that there were no dropouts or withdrawals.

Unclear, if the report gave the impression that there had been no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated.

Inadequate, if the number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals were not described.

Trials with adequate generation of the allocation sequence, adequate allocation concealment, adequate blinding, and adequate follow‐up were considered low‐bias risk trials (high methodological quality) (Kjaergard 2001; Gluud 2006a). Trials with one or more unclear or inadequate quality components were classified as high‐bias risk trials (low methodological quality) (Kjaergard 2001; Gluud 2006a).

We also reported on whether the investigators had performed a sample‐size calculation and used intention‐to‐treat analysis (Gluud 2001).

We used the classification of quality for sensitivity analyses and not as exclusion criteria.

Statistical analyses We performed the meta‐analyses according to the recommendations of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2006). For the statistical analyses, we used RevMan Analyses (RevMan 2003), STATA 8.2 (STATA Corp, College Station, Tex), Sigma Stat 3.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill), and Stats‐Direct (StatsDirect Ltd, Altrincham, England).

We analysed the data with both random‐effects (DerSimonian 1986) and fixed‐effect (DeMets 1987) models meta‐analyses. We present the results of the random‐effects model analysis if the two models concur regarding statistical significance (P < 0.05). If not, we present both analyses. Results are presented as the relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We assessed heterogeneity with I2, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2002). I2 can be calculated as I2 = 100% × (Q‐df)/Q (Q = Cochran's heterogeneity statistics, df = degrees of freedom). I2 ranged between 0% (ie, no observed heterogeneity) and 100% (maximal heterogeneity) (Higgins 2002). We used the STATA metareg command (Sharp 1998) for the random‐effects meta‐regression analyses to assess potential covariates predicting intertrial heterogeneity, ie, the covariates that are statistically associated with estimated intervention effects. The included covariates were type and dose of supplement, duration of supplementation, bias risk (low or high), and primary or secondary prevention. Trials with participants coming from the general population, areas with high incidence of gastrointestinal cancers, and other patient groups with non‐gastrointestinal diseases were considered primary prevention trials. Trials in participants with premalignant conditions of the gastrointestinal tract were considered secondary prevention trials. We performed univariate and multivariate analyses including all covariates.

All our analyses followed the intention‐to‐treat principle. We accounted all of the participants for each trial and performed the analyses irrespective of how the original trialists had analysed the data. Participants lost to follow‐up were considered survivors. For trials with a factorial design, we based our results on 'at‐margins' analysis, comparing all groups that received antioxidant supplements with groups that did not receive antioxidant supplements (McAlister 2003). To determine the effect of a single antioxidant we performed 'inside the table' analysis (McAlister 2003) in which we compared the single antioxidant arm with the placebo/no intervention arm. In the trials with parallel group design with more than two arms and additional therapy, we compared only the arms supplemented with antioxidants with the placebo arm (Higgins 2006).

Comparison of intervention effects was conducted with test of interaction (Altman 2003).

We performed adjusted rank correlation (Begg 1994) and regression asymmetry test (Egger 1997) for detection of bias. A P < 0.10 was considered significant.

Results

Description of studies

Search results We identified a total of 1096 references through the four gastrointestinal disease Cochrane Groups (n = 90), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library (n = 221), MEDLINE (n = 224), EMBASE (n = 269), LILACS (n = 75), Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐expanded) (n = 96), the Chinese Biomedical Database (n = 36), and reading references (n = 85). We excluded 411 duplicates and 374 clearly irrelevant references through reading abstracts. Accordingly, 311 references were retrived for further assessment. Of these, we excluded 58 references because they did not fulfill our inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion are listed in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. In total, 253 references describing 24 randomised trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Among these references, 11 references described 4 ongoing trials. These trials are listed under 'Characteristics of ongoing studies'. The remaining 242 references, describing 20 trials, fulfilled our inclusion criteria and provided data for the analyses. Details of the trials are shown in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Trial design Nine trials used factorial designs (one trial 'half replicate of two‐by‐two‐by‐two‐by‐two', 4 trials 'two‐by‐two‐by‐two', and 4 trials 'two‐by‐two') and 11 trials used the two‐ or more‐armed parallel group trial designs. One 'two‐by‐two‐by‐two' factorial trial proceeded as a 'two‐by‐two' factorial trial. Two of the 'two‐by‐two' factorial trials proceeded as two‐armed trials (Pocock 1991) (Table 2).

2. Table.

| Trial | Design of the trials | Number of arms | Antioxidant vitamin supplements plus any additional non‐antioxidant interventions in the experimental arm/arms | Control group | Analysis reported |

| Munoz 1985 | Parallel. | 2 | Vitamin A, vitamin B2, and zinc. | Placebo. | |

| Yu 1991 | Parallel. | 2 | Selenium. | Placebo. | |

| NIT1 1993 | Half replicate of a 2x2x2x2 factorial trial. | 8 | A) Vitamin A, vitamin B2, vitamin B3, and zinc. B) Vitamin A, vitamin C, zinc, and molybdenum. C) Vitamin A, beta‐carotene, vitamin E, selenium, and zinc. D) Vitamin C, vitamin B2, vitamin B3, and molybdenum. E) Beta‐carotene, vitamin E, selenium, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3. F) Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and molybdenum. G) Vitamin A, beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, zinc, vitamin B2, vitamin B3, and molybdenum. | Placebo. | Four‐way. |

| NIT2 1993 | Parallel. | 2 | 13 vitamins (vitamin A, beta‐carotene, vitamin E, vitamin C, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, vitamin D, folic acid, niacinamide, biotin, pantothenic acid) and 13 minerals (calcium, phosphorus, iodine, iron, magnesium, copper, manganese, potassium, chloride, chromium, molybdenum, selenium, and zinc). | Placebo. | |

| NPCT 1996 | Parallel. | 2 | Selenium. | Placebo. | |

| PHS 1996 | 2x2 factorial trial changed into two‐armed trial. | Initially 4, then changed into 2. | A) Aspirin. B) Beta‐carotene. C) Beta‐carotene and aspirin. | Placebo. | Two‐way. |

| Yu 1997 | Parallel. | 2 | Selenium. | Placebo. | |

| Correa 2000 | 2x2x2 factorial trial. | 8 | A random half of the patients were treated with anti‐Helicobacter pylori treatment medication (which consisted of amoxicillin, metronidazole, and bismuth subsalicylate) before the start of the 2x2 factorial design of beta‐carotene and/or vitamin C versus placebo. A) Beta‐carotene. B) Vitamin C. C) Beta‐carotene plus anti‐Helicobacter pylori treatment. D) Vitamin C plus anti‐Helicobacter pylori treatment. E) Beta‐carotene and vitamin C. F) Beta‐carotene and vitamin C plus anti‐Helicobacter pylori treatment. G) anti‐Helicobacter pylori treatment. | Placebo. | Eight‐way. |

| Li 2000 | Parallel. | 2 | Selenium. | Placebo. | |

| HPS 2002 | 2x2 factorial trial. | 4 | A) Vitamin E, vitamin C, and beta‐carotene. B) Simvastatin. C) Vitamin E, vitamin C, beta‐carotene, and simvastatin. | Placebo. | Two‐way. |

| ATBC 2003 | 2x2 factorial trial. | 4 | A) Vitamin E. B) Beta‐carotene. C) Beta carotene and vitamin E. | Placebo. | Four‐way |

| Zhu 2003 | Parallel. | 3 (A fourth group assessing folate and vitamin B12 was disregarded.) | A) Beta‐carotene (natural). B) Beta‐carotene (synthetic). | Placebo. | |

| CARET 2004 | 2x2 factorial trial changed into two‐armed trial. | Initially 4, then changed into 2. | Vitamin A and beta‐carotene. | Placebo. | |

| Li 2004 | Parallel. | 2 | Selenium, synthetic allitridum (garlic extract). | Placebo. | |

| SUVIMAX 2004 | Parallel. | 2 | Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and zinc [as gluconate]) . | Placebo. | |

| HOPE TOO 2005 | 2x2 | 4 | A) Vitamin E. B) Ramipril (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor). C) Vitamin E plus ramipril. | Placebo. | Two‐way. |

| WHS 2005 | 2x2x2 factorial trial. | Initially 8, changed into 4. | A) Beta‐carotene (abandoned after 22.8 months). B) Vitamin E. C) Beta‐carotene and vitamin E. D) Beta‐carotene and aspirin. E) Vitamin E and aspirin. F) Beta‐carotene, vitamin E, and aspirin. G) Aspirin. | Placebo. | Two‐way. |

| SIT 2006 | 2x2x2; 2x2 | 8 plus 4 | A) Amoxicillin and omeprazole, garlic, vitamin capsule* and selenium. B) Amoxicillin and omeprazole, garlic, vitamin placebo C) Amoxicillin and omeprazole, vitamin capsule* and selenium. D) Amoxicillin and omeprazole and vitamin placebo E) Garlic, vitamin capsule*, and selenium. F) Garlic and vitamin placebo. G) Vitamin capsule* and selenium. H) Garlic and selenium placebo. I) Garlic. J) Vitamin placebo. K) Selenium. *The vitamin capsule contained vitamin C (250 mg), vitamin E (100 IU), and selenium from yeast (37.5 µg) . | Placebo. | Two‐way |

| Plummer 2007 | Parallel | 2 | Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E. | Placebo. | |

| WACS 2007 | 2x2x2 | 8 Another arm testing a combination of folic acid (2.5 mg), vitamin B6 (50 mg), and vitamin B12 (1 mg) was disregarded. | A) Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E. B) Beta‐carotene placebo, vitamin C, and vitamin E. C) Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E placebo. D) Beta‐carotene placebo, vitamin C, and vitamin E placebo. E) Beta‐carotene, vitamin C placebo, and vitamin E. F) Beta‐carotene placebo, vitamin C placebo, and vitamin E. G) Beta‐carotene, vitamin C placebo, and vitamin E placebo. | Placebo. | Eight‐way |

Participants A total of 211,818 participants were randomised in the 20 trials. The number of participants in each trial ranged from 216 to 39876. We were not able to extract relevant data on the sex of the participants from two trials. The percentage of men was 58% of the trials reporting sex. The age varied from 18 to 84 years with a mean age of 56.5 years.

There were five trials with 122,411 participants from the general population (PHS 1996; ATBC 2003: CARET 2004; SUVIMAX 2004; WHS 2005), four trials (Munoz 1985; Yu 1991; NIT1 1993; Li 2004) with 37701 healthy participants living in areas at higher risk of developing gastrointestinal cancers, and four trials (NPCT 1996: HPS 2002; HOPE TOO 2005: WACS 2007) with 39560 participants with non‐gastrointestinal diseases; all were considered as primary prevention trials. There were seven trials (NIT2 1993; Yu 1997; Correa 2000; Li 2000; Zhu 2003; SIT 2006: Plummer 2007) with 12102 participants with premalignant conditions of the gastrointestinal tract; these were considered as secondary prevention trials.

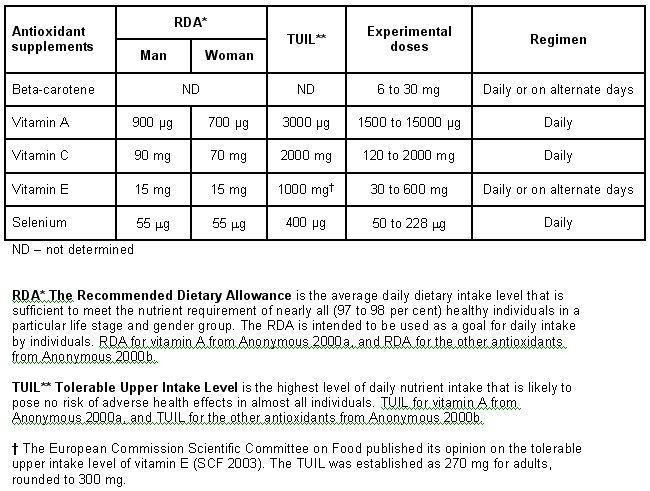

Experimental interventions The route of antioxidant administration was oral for all the trials. Antioxidants were administered either alone, or in combination with other antioxidants, or with or without other vitamins, minerals or other interventions (Table 2). The types, doses, dose regimens, and duration of supplementation with antioxidants were as follows: beta‐carotene 6 mg to 30 mg (12 trials), vitamin A 1500 µg to 15000 µg (4 trials), vitamin C 120 to 2000 mg (8 trials), vitamin E 30 to 600 mg (10 trials), daily or on alternate days for 1.1 to 12 years; selenium 50 to 228 µg (9 trials), daily for two to four years (Figure 1). In one trial antioxidant supplements (vitamin A, riboflavin, and zinc) were given once weekly (Munoz 1985). One trial administered beta‐carotene 30 mg daily for the first year and 30 mg two times a week for the second (Zhu 2003). One trial administered selenium 100 µg on alternate days for one month of each year during two years (Li 2004).

1.

Recommended dietary allowance, tolerable upper intake level, experimental doses, and regimen used in antioxidant supplements

Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, or selenium were administered as a single antioxidant supplement (Table 2). Beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium formed different combinations of antioxidant supplements only or were administered together with non‐antioxidant supplements (Table 3 and Table 2). The administered combinations consisting only of antioxidant supplements were: beta‐carotene and vitamin A; beta‐carotene and vitamin C; beta‐carotene and vitamin E; beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E; vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium; beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E, and selenium (see 'Characteristics of included studies' and Table 2).

3. Table.

| Experimental antioxidant supplements | Oesophageal cancer | Gastric cancer | Colorectal cancer | Pancreatic cancer | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Beta‐carotene (PHS 1996; Correa 2000; ATBC 2003; Zhu 2003) | 0.75, 0.25 to 2.30 | 1.12, 0.79 to 1.59 | 1.09, 0.79 to 1.51 | 1.02, 0.54 to 1.90 | 1.92, 0.96 to 3.85 |

| Vitamin E (ATBC 2003; HOPE TOO 2005) | 1.46, 0.72 to 2.96 | 1.30, 0.90 to 1.88 | 1.10, 0.87 to 1.39 | 0.97, 0.67 to 1.39 | 1.33, 0.63 to 2.82 |

| Selenium (Yu 1991; NPCT 1996; Yu 1997; Li 2000; Li 2004) | 0.40, 0.08 to 2.07 | 0.76, 0.44 to 1.31 | 0.48, 0.22 to 1.05 | ND | 0.56, 0.42 to 0.76 |

| Beta‐carotene and vitamin A (CARET 2004) | 1.43, 0.90 to 2.29 | 0.89, 0.46 to 1.73 | 0.97, 0.76 to 1.25 | 1.33, 0.84 to 2.09 | 1.35, 0.51 to 3.54 |

| Beta‐carotene and vitamin C (Correa 2000) | ND | 2.90, 0.12 to 70.52 | ND | ND | ND |

| Beta‐carotene and vitamin E (ATBC 2003) | 1.23, 0.59 to 2.56 | 1.40, 0.98 to 2.01 | 1.20, 0.89 to 1.63 | 0.93, 0.65 to 1.35 | 1.25, 0.59 to 2.67 |

| Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (HPS 2002; Plummer 2007) | 1.19, 0.71 to 2.01 | 1.25, 0.78 to 2.00 | 0.84, 0.65 to 1.07 | 1.00, 0.57 to 1.76 | 1.40, 0.44 to 4.41 |

| Vitamin A, riboflavin, and zinc (Munoz 1985) | 1.33, 0.30 to 5.91 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (SIT 2006) | ND | 1.01, 0.60 to 1.68 | ND | ND | ND |

| Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (SUVIMAX 2004) | 1.01, 0.14 to 7.16 | 1.01, 0.14 to 7.16 | 0.88, 0.49 to 1.58 | 0.67, 0.19 to 2.38 | 1.01, 0.06 to 16.12 |

| 26 vitamins/minerals (NIT2 1993) | 0.96, 0.76 to 1.22 | 1.19, 0.89 to 1.58 | ND | ND | ND |

| GI = gastrointestinal; ND = No data | |||||

| Relative risk, 95% confidence interval (random). |

Six trials added non‐antioxidant vitamins, ie, vitamin B12 and folic acid (Zhu 2003), vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and folic acid (WACS 2007), or non‐antioxidant vitamins and minerals (Munoz 1985; NIT1 1993; NIT2 1993; SUVIMAX 2004) to the experimental arms (see 'Characteristics of included studies' and Table 2).

Control interventions All trials used placebo capsules or tablets as control intervention.

Concomitant interventions The factorial designs of the trials permitted other interventions to be administered to some of the participants in the antioxidant experimental arms and in the control arms. Four trials primarily connected with the occurrence of cancers and cardiovascular diseases tested additional therapies: aspirin 100 mg to 325 mg, given daily or on alternate days (PHS 1996; WHS 2005); simvastatin (cholesterol lowering therapy) 40 mg (HPS 2002); or ramipril 10 mg (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor) (HOPE TOO 2005). Two trials assessed anti‐Helicobacter pylori interventions (Correa 2000; SIT 2006), two trials aged garlic extract 200 mg (Li 2004; SIT 2006), and one trial vitamin B6 50 mg, vitamin B12 1 mg, and folic acid 2.5 mg (WACS 2007) (Table 2).

Outcome measures All 20 trials examined gastrointestinal cancers. We were able to extract relevant data on the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers from 18 trials. We were not able to extract data on the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers for each arm separately from one trial (NIT1 1993), and the authors did not respond to our requests for further information. The data from WACS 2007 are not yet available.

Only 14 of the trials (70%) could provide data on overall mortality. Sponsorship Pharmaceutical companies were the provider or sponsor of antioxidant supplements in 17 trials. This information was not available in three trials (Yu 1991; Yu 1997; Li 2000). Roche was the sponsor or provider in 8 out of 17 trials (47%).

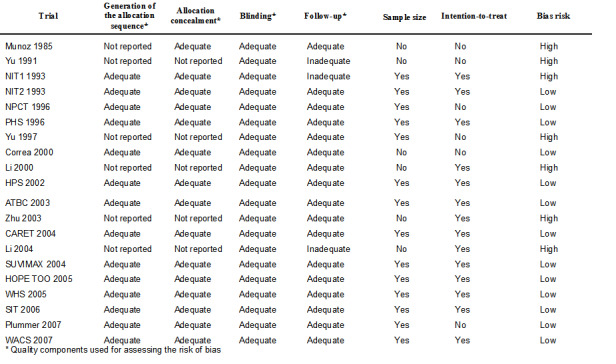

Risk of bias in included studies

For an overview of the methodological quality of the included trials see Figure 2.

2.

Table 05.

Bias risk of the trials

Gastrointestinal cancers Twelve trials out of the 18 (66.7%) providing data on gastrointestinal cancers reported adequate generation of the allocation sequence, 13 trials (72.3%) reported adequate allocation concealment, 18 trials (100%) used placebo and hence had presumed adequate blinding, and 16 trials (88.9%) reported adequate follow‐up. Twelve trials (66.7%) reported sample‐size calculations. Twelve trials (66.7%) based their analyses on the intention‐to‐treat principle.

There were 12 trials (66.7%) of low‐bias risk (high methodological quality) with adequate generation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, as well as follow‐up.

Overall mortality Among the 14 trials providing data on mortality, thirteen (92.9%) were of low‐bias risk (high methodological quality) with adequate generation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, as well as follow‐up. The 14th trial had inadequate follow‐up (NIT1 1993).

Effects of interventions

Gastrointestinal cancers Antioxidant supplements had no significant influence on gastrointestinal cancer occurrence (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.06, I2 = 54.0%). Approximately 2.2% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared with 2.0% in the placebo group developed gastrointestinal cancers at the end of follow‐up.

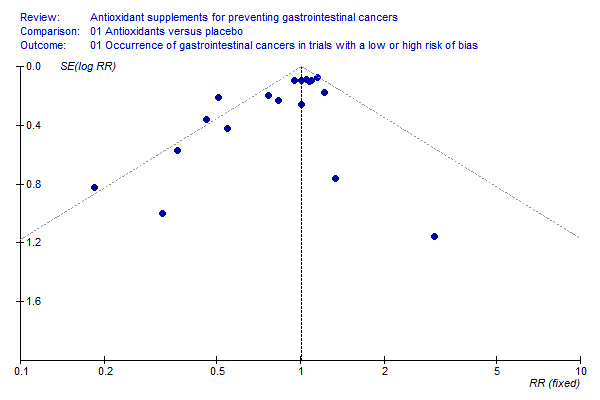

Funnel plot asymmetry We analysed the antioxidant effect on gastrointestinal cancers for funnel plot asymmetry (Figure 3). From inspection of the figure, one may suspect bias. The asymmetry was statistically significant (P = 0.009) by Egger's test and (P = 0.096) by Begg's test.

3.

Funnel plot ‐ occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers

Meta‐regression analysis Univariate meta‐regression analyses revealed that the following covariates were significantly associated with estimated intervention effect on the occurrence of the gastrointestinal cancers: dose of beta‐carotene (RR 1.01, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.02; P = 0.012) and dose of selenium (RR 0.997, 95% CI 0.995 to 0.998, P < 0.0001). None of the other covariates (dose of vitamin A; dose of vitamin C; dose of vitamin E; bias risk of the trials; duration of supplementation; and primary or secondary prevention) were significantly associated with estimated intervention effect on gastrointestinal cancers.

In multivariate meta‐regression analysis including all covariates, dose of selenium was associated with a significantly lower estimated intervention effect on the gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.996, 95% CI 0.994 to 0.999; P = 0.007). None of the other covariates was significantly associated with the estimated intervention effect on the gastrointestinal cancers.

Methodological quality and antioxidant effect on gastrointestinal cancer occurrence The trials with low risk of bias (n = 12) did not show a significant effect of antioxidant supplements on gastrointestinal cancers (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.13, I2 = 19.6%). In the trials with high risk of bias (n = 6) antioxidant supplements significantly decreased gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.80, I2 = 18.1%). The difference between the estimates obtained by trials with adequate and unclear or inadequate methodology was statistically significant by test of interaction (z = ‐3.53, P < 0.0005).

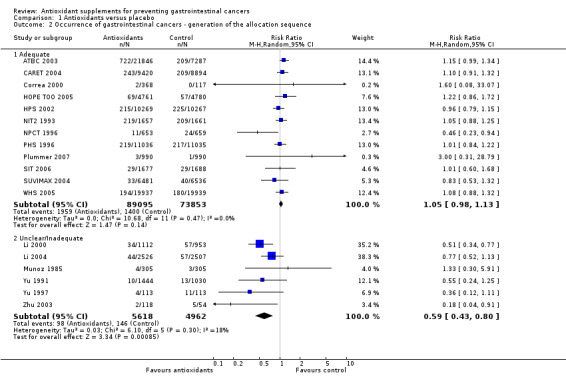

Generation of the allocation sequence In the trials with adequate generation of the allocation sequence, antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence gastrointestinal cancers (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.13, I2 = 0%). In the trials with unclear or inadequate generation of the allocation sequence, antioxidant supplements showed a significant beneficial effect on gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.80, I2 = 18.1%). The difference between the estimates obtained by trials with adequate and unclear or inadequate generation of the allocation sequence was statistically significant by test of interaction (z = ‐3.55, P < 0.0005).

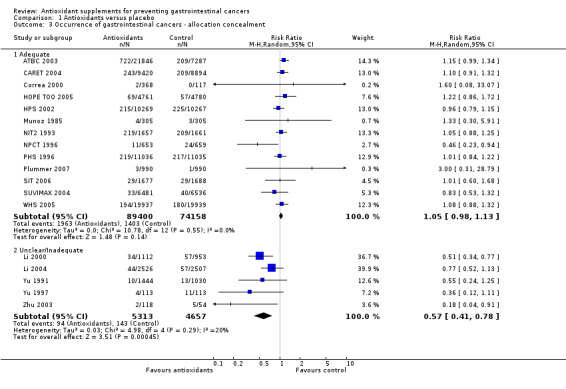

Allocation concealment In the trials with adequate allocation concealment, antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence gastrointestinal cancers (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.13, I2 = 0%). In the trials with unclear or inadequate allocation concealment, antioxidant supplements showed a significant beneficial effect on gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.78, I2 = 19.6%). The difference between the estimates obtained by trials with adequate and unclear or inadequate allocation concealment was statistically significant by test of interaction (z = ‐3.64, P < 0.0003).

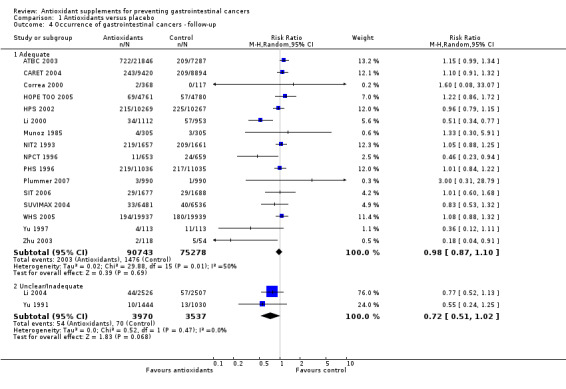

Blinding Blinding was assumed adequate in all the 18 trials due to the use of placebo.

Follow‐up In the trials with adequate follow‐up, antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.10, I2 = 49.8%). In the trials with unclear follow‐up, antioxidant supplements showed no significant effect on gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.02, I2 = 0%). The difference between the estimates obtained by trials with adequate and unclear or inadequate follow‐up was not statistically significant by test of interaction (z = ‐1.65, P = 0.0989).

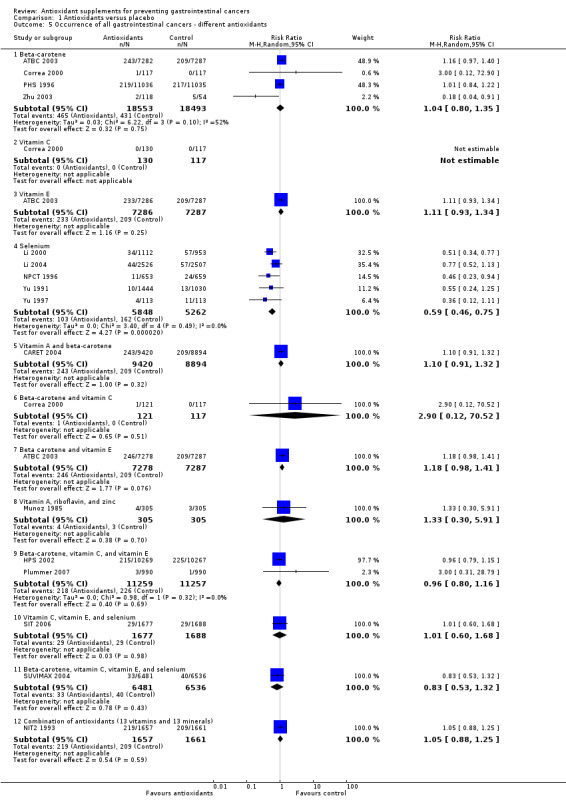

Type of antioxidant supplement Beta‐carotene (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.35) or vitamin E (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.34) given singly did not significantly influence gastrointestinal cancers. Different combinations of antioxidants, that is, beta‐carotene and vitamin A; beta‐carotene and vitamin C; beta‐carotene and vitamin E; vitamin A, riboflavin, and zinc; beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E; vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium; beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium, or combinations of 26 vitamins/minerals did not significantly influence gastrointestinal cancers (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.32; RR 2.90, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.52; RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.41; RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.30 to 5.91; RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.16; RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.68; RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.32; RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.25; respectively). Selenium given singly significantly decreased gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.75, I2 = 0%). Selenium combined did not significantly influence gastrointestinal cancers (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.19, I2 = 0%). Selenium given singly or combined significantly decreased gastrointestinal cancers (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.98, I2 = 60.8%). Five out of the nine trials assessing selenium had high‐bias risk. The effect of selenium given singly or combined in 4 low‐bias risk trials was not significant (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.18, I2 = 45.0%). For an overview of the effect of the different antioxidant supplements on different gastrointestinal cancers see (Table 3).

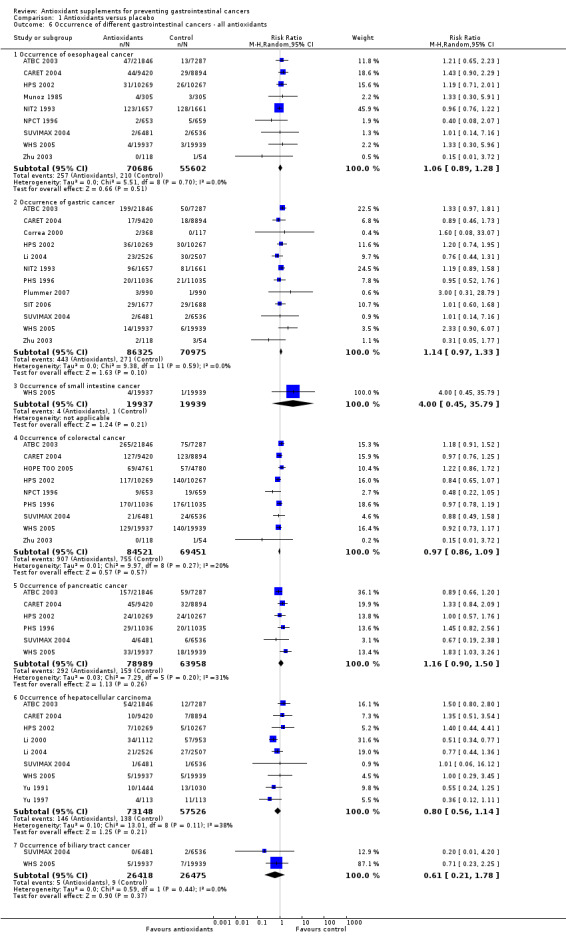

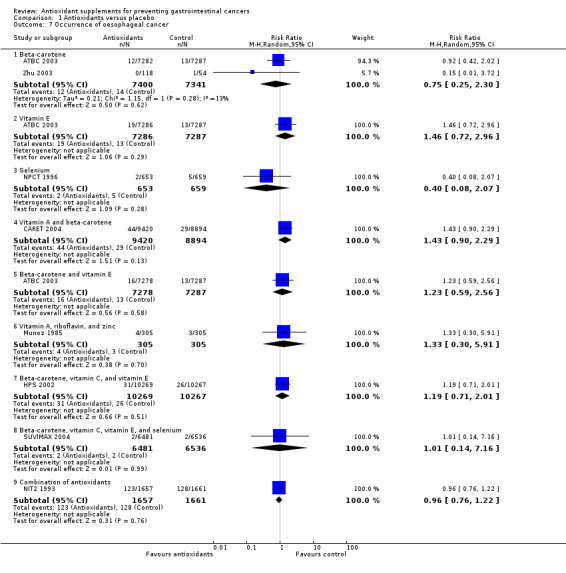

Occurrence of oesophageal cancer Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence oesophageal cancer (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.28, I2 = 0%). Approximately 0.36% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared to 0.38% in the placebo group developed oesophageal cancer at the end of follow‐up. Antioxidants administered singly, ie, beta‐carotene (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.30); vitamin E (RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.96); selenium (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.07), or in certain combinations as beta‐carotene and vitamin A (RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.90 to 2.29); beta‐carotene and vitamin E (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.56); vitamin A, riboflavin, and zinc (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.30 to 5.91); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.71 to 2.01); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E and selenium (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.14 to 7.16), or combination of 26 vitamins/minerals (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.22) versus placebo for a period of 1.1 to 10.1 years, with a follow‐up up to 14.1 years, did not significantly influence oesophageal cancer.

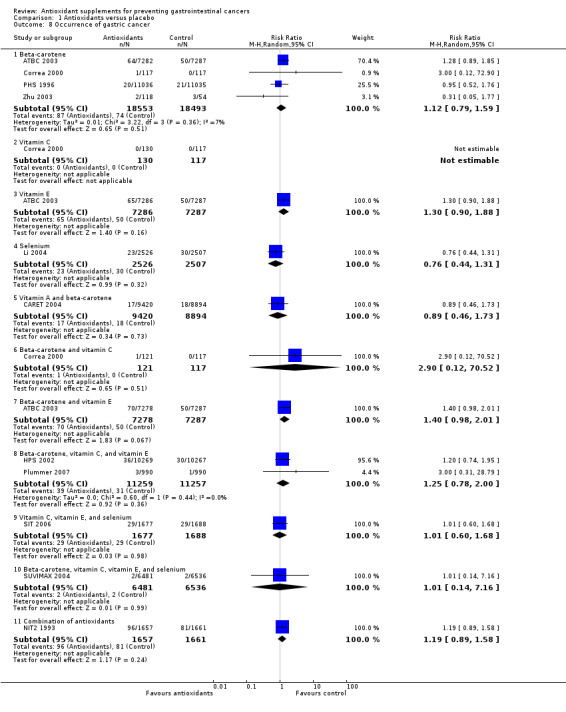

Occurrence of gastric cancer Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence gastric cancer (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.33, I2 = 0%). Approximately 0.51% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared to 0.38% in the placebo group developed gastric cancer at the end of follow‐up. Antioxidants administered singly, ie, beta‐carotene (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.59); vitamin E (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.88); selenium (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.31), or in certain combinations as beta‐carotene and vitamin A (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.73); beta‐carotene and vitamin C (RR 2.90, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.52); beta‐carotene and vitamin E (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.01); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.00); vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.68); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.14 to 7.16), or combination of 26 vitamins/minerals (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.58) versus placebo for a period of 2.1 to 12 years and follow‐up up to 14.1 years did not significantly influence gastric cancer.

Occurrence of small intestine cancer Only one trial had results about small intestine cancer (WHS 2005). Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence small intestine cancer (RR 4.00, 95% CI 0.45 to 35.79).

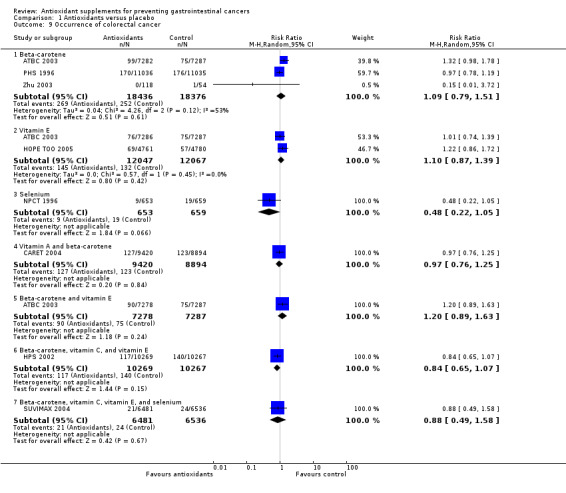

Occurrence of colorectal cancer Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence colorectal cancer (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09, I2 = 19.7%). Approximately 1.07% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared to 1.09% in the placebo group developed colorectal cancer at the end of follow‐up. Antioxidants administered singly, ie, beta‐carotene (RR 1,09 95%CI 0.79 to 1.51); vitamin E (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.39); selenium (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.05); or in combinations as beta‐carotene and vitamin A (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.25); beta‐carotene and vitamin E (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.63); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.07); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 0.88 95% CI 0.49 to 1.58) versus placebo for a period of 2.1 to 12 years and follow‐up up to 14.1 years did not significantly influence colorectal cancer.

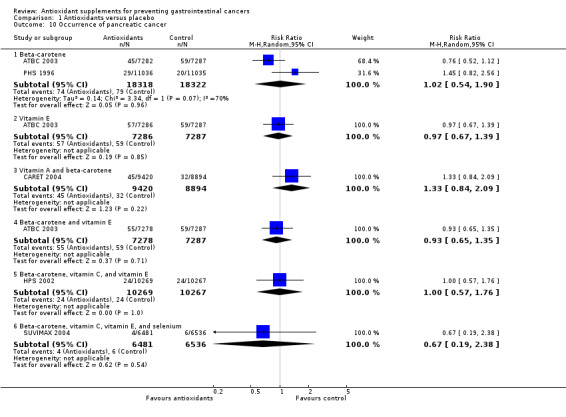

Occurrence of pancreatic cancer Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence pancreatic cancer (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.50, I2 = 31.4%). Approximately 0.37% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared to 0.25% in the placebo group developed pancreatic cancer at the end of follow‐up. Antioxidants administered singly, ie, beta‐carotene (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.90); vitamin E (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.39); or in combinations as beta‐carotene and vitamin A (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.09); beta‐carotene and vitamin E (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.35); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.76); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.38) versus placebo for a period of 2.1 to 12 years and follow‐up up to 14.1 years did not significantly influence pancreatic cancer.

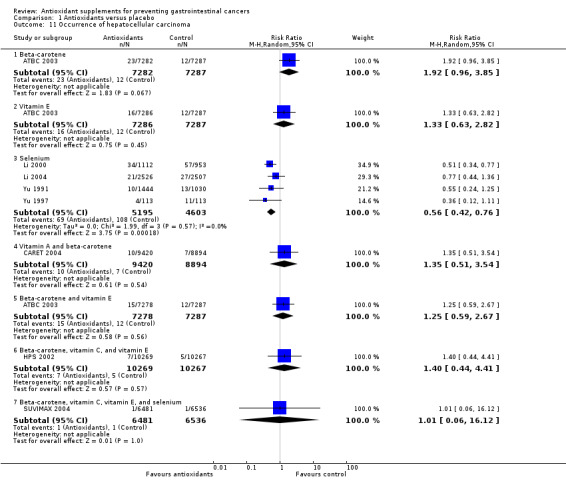

Occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence hepatocellular carcinoma (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.14, I2 = 38.5%). This effect was significantly beneficial in a fixed‐effect model (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.96). Approximately 0.20% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared to 0.24% in the placebo group developed hepatocellular carcinoma at the end of follow‐up. Beta‐carotene administered singly (RR 1.92 95% CI 0.96 to 3.85), and vitamin E administered singly (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.63 to 2.82) versus placebo for a period of 2 to 10.1 years and follow‐up up to 14.1 years did not significantly influence hepatocellular carcinoma. Antioxidants in combinations as beta‐carotene and vitamin A (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.51 to 3.54), beta‐carotene and vitamin E (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.67), beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.44 to 4.41), or beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.12) did not significantly influence hepatocellular carcinoma. Selenium administered singly versus placebo for two to four years significantly decreased hepatocellular carcinoma (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.76, I2 = 0%). All four trials assessing selenium singly had high‐bias risk.

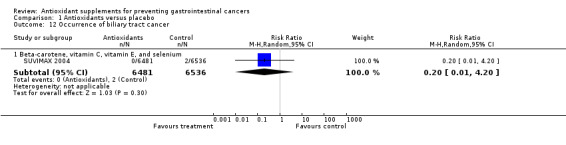

Occurrence of biliary tract cancer Antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence biliary tract cancers (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.78, I2 = 0%. Approximately 0.019% of the participants in the antioxidant group compared to 0.034% in the placebo group developed biliary tract cancers at the end of follow‐up. Antioxidants administered in combination as beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium had no significant influence on biliary tract cancers (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.20).

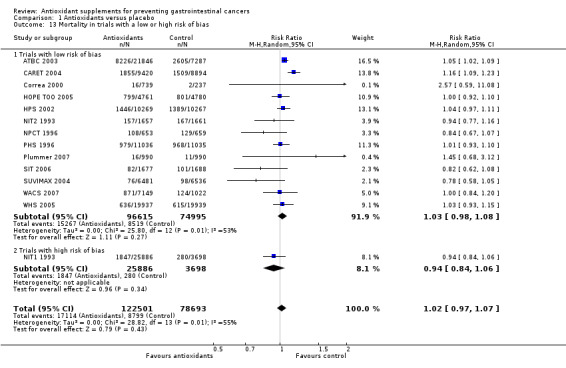

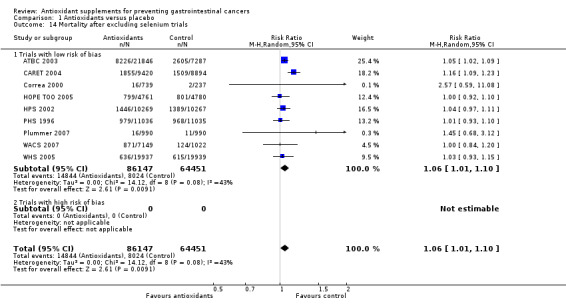

Overall mortality Antioxidant supplements had no significant effect on mortality in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.07, I2 = 54.9%). Antioxidant supplements significantly increased mortality in the fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis (RR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.07). A total of 17114 of 122,501 participants (14.0%) that were randomised to antioxidant supplements and 8799 of 78693 participants (11.2%) randomised to placebo died. To explore the reason for the difference between the two models, we excluded the trials administering selenium. After their exclusion, mortality was significantly higher in the antioxidant group with both the random‐effects (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.10, I2 = 43.3%) and fixed‐effect model meta‐analyses (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.09).

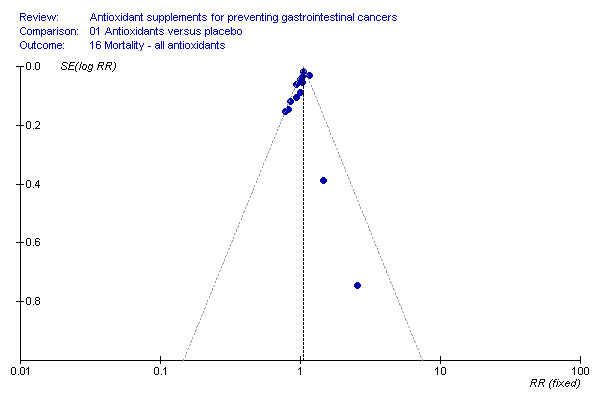

Funnel plot asymmetry We analysed the antioxidant effect on mortality for funnel plot asymmetry (Figure 4). The asymmetry was not statistically significant (P = 0.13) by Egger's test and (P = 0.15) by Begg's test.

4.

Funnel plot ‐ overall mortality

Meta‐regression analysis Univariate meta‐regression analyses revealed that the following covariates were significantly associated with estimated intervention effect on mortality: dose of beta‐carotene (RR 1.007, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.012; P = 0.003), dose of vitamin A (RR 1.000006, 95% CI 1.000001 to 1.000011, P = 0.009), and dose of selenium (RR 0.998, 95% CI 0.997 to 0.999, P = 0.002). None of the other covariates, ie, dose of vitamin C; dose of vitamin E; bias risk of the trials; duration of supplementation; and primary or secondary prevention, were significantly associated with estimated intervention effect on mortality.

In multivariate meta‐regression analysis including all covariates, dose of selenium was associated with the estimated intervention effect on mortality (RR 0.998, 95% CI 0.997 to 1.000, P = 0.043). None of the other covariates was significantly associated with the estimated intervention effect on mortality.

Methodological quality and antioxidant effect on overall mortality The effect of antioxidant supplements on mortality in trials with low risk of bias (high methodological quality) was not statistically significant in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.08, I2 = 53.5%). Antioxidant supplements significantly increased mortality in a fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis (RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.07). In the one trial with high risk of bias (NIT1 1993) antioxidant supplements did not significantly influence mortality (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.06). The difference between the estimate of antioxidant effect in low‐bias and high‐bias risk trials was not significant by test of interaction (z = ‐1.42, P = 0.156).

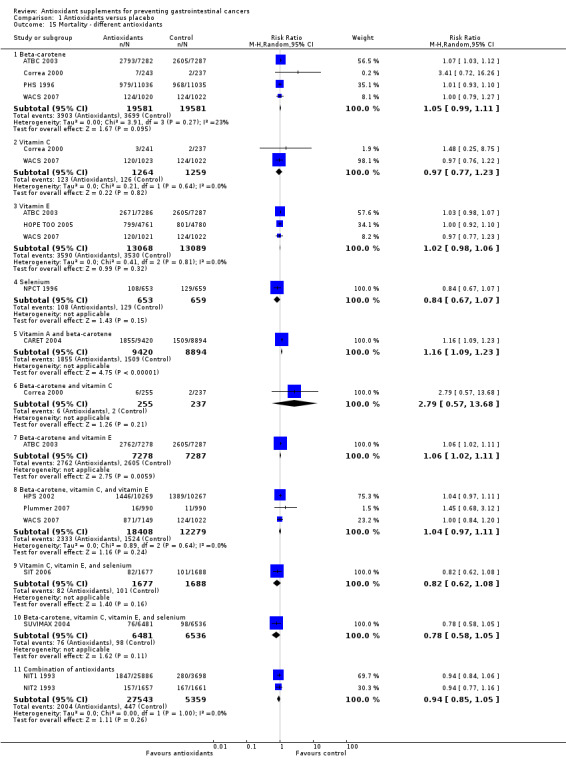

Type of antioxidant supplement Antioxidants given singly, ie, beta‐carotene (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.11), vitamin C (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23); vitamin E (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.06); and selenium (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.07) did not significantly influence mortality. Beta‐carotene used singly significantly increased mortality in a fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.10). Mortality in participants supplemented with beta‐carotene and vitamin A (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.23), or beta‐carotene and vitamin E (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.11) was significantly higher than in the placebo group. Antioxidants given in certain combinations, ie, beta‐carotene and vitamin C (RR 2.79, 95% CI 0.57 to 13.68); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.11); vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.08); beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.05), or combination of 26 vitamins/minerals (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.05) versus placebo did not significantly influence mortality.

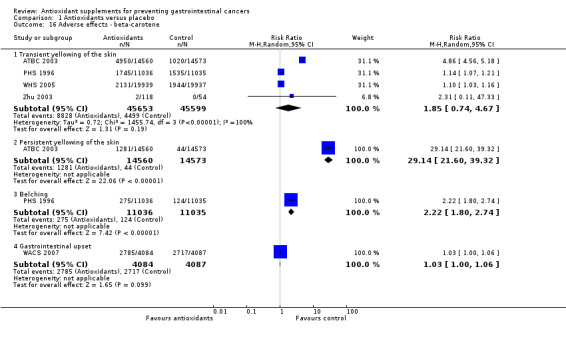

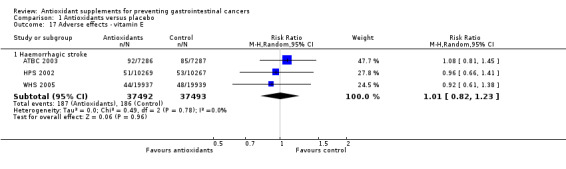

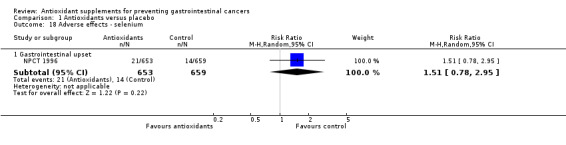

Non‐serious adverse effects Several adverse effects were recorded in the antioxidant group. Persistent yellowing of the skin and belching were significantly increased in participants supplemented with beta‐carotene (RR 29.14, 95% CI 21.60 to 39.32; RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.80 to 2.74; respectively). Transient yellowing of the skin (RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.74 to 4.67) and gastrointestinal upset (RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06) were not significantly influenced. Haemorrhagic stroke was not significantly influenced by vitamin E (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.23, I2 = 0%). Gastrointestinal upset in participants supplemented with selenium was not significantly different when compared to placebo (RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.95). Increased yellowing of the urine and the feeling of being hot and dry in participants taking a combination of 13 vitamins and 13 minerals was also not significantly different between the antioxidant and the placebo group.

Quality of life and cost‐effectiveness We did not find any data on quality of life in the randomised trials included in this review. We found cost‐effectiveness analyses in one trial (PHS 1996).

Discussion

Compared to our previous review (Bjelakovic 2004a), the number of included trials in the present review is expanded with six new trials (42.9%) adding 41293 participants (24.2%). Moreover, we have obtained updated results of longer follow‐up from three large‐scale randomised trials (ATBC 2003; CARET 2004; WHS 2005). Our results remain largely the same. Antioxidant supplements, ie, beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin E given singly or in combinations, do not seem to prevent gastrointestinal cancers. Beta‐carotene and vitamin A may increase the cancer risk. The studied antioxidants, other than selenium, also seem to increase overall mortality. Thus, the present results support our findings from 47 low‐bias risk trials showing increased mortality in participants undergoing primary or secondary prevention with similar antioxidant supplements (Bjelakovic 2007). Selenium might potentially reduce gastrointestinal cancers and mortality, but these observations run the risk of bias due to the low methodological quality of most of the assessed trials. Only one of the trials investigating selenium given as a single antioxidant had low‐bias risk (NPCT 1996). Although several hypotheses have been explored, the mechanisms involved in the possible cancer preventive role of selenium are largely unknown (Rayman 2005; Papp 2007). Recently, a randomised trial has shown that selenium may carry health risks, eg, increasing the risk of diabetes mellitus (Stranges 2007). Before therapeutic or preventive actions are considered, results of ongoing high‐quality randomised trials with selenium are needed (APPOSE 2001; SELECT 2003; HGPIN 2006).

Our review shows that beta‐carotene possesses significantly harmful effects on gastrointestinal cancers and seems to increase mortality when applied singly or in combination with vitamin A or vitamin E. A recent study suggests that beta‐carotene may act as a co‐carcinogen (Paolini 2003). In another review that we have performed, we have also demonstrated that beta‐carotene seems to increase mortality (Bjelakovic 2007). We were unable to identify trials assessing vitamin A alone in the prevention of gastrointestinal cancers. The combination of beta‐carotene and vitamin A was assessed in a high‐quality, large‐scale randomised trial having lung cancer prevention as the primary outcome (CARET 2004). Gastrointestinal cancer occurrence and overall mortality were significantly higher in the vitamin A supplemented group. Recent research in this field suggest that vitamin A might have pro‐oxidant abilities, which could lead to carcinogenesis (Murata 2000) and may even increase mortality (Bjelakovic 2007). This finding was corroborated in the present systematic review. The trials in which vitamin C was applied alone or in different combinations with beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin E, and selenium found no significant effect on gastrointestinal cancers, or on overall mortality. Vitamin E did not significantly influence gastric, pancreatic, and colorectal cancer or overall mortality. According to recent meta‐analyses, vitamin E seems to increase overall mortality (Miller 2005; Bjelakovic 2007). Therefore, preventive use of vitamin E cannot be recommended.

The bias risk of the trials had a significant impact on our results. The low‐bias risk trials either showed significant harmful effects or no significant effects of antioxidant supplements on the primary outcome measures. On the contrary, trials with high‐bias risk found either no significant effects or significant beneficial effects. These observations are in accordance with several studies linking high‐bias risk with significant overestimation of beneficial effects (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001; Jüni 2001; Egger 2003; Gluud 2006a; Gluud 2006b) and underreporting of adverse effects (D'Amico 2003). Our meta‐regression analysis failed to identify bias risk as associated with risk of cancer, but we observed that trials with high risk of bias found a decreased risk of cancer.

We can only speculate what caused the significantly higher mortality among the participants supplemented with antioxidants. Based on our present results as well as the results of previous randomised trials and meta‐analysis it is likely that both cardiovascular diseases (ATBC 2003; Vivekananthan 2003) and cancers (ATBC 2003; CARET 2004) have led to increased mortality. We observed a non‐significant tendency towards increased occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers in the supplemented group of low‐bias risk trials (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.13). Observational studies have shown possible detrimental effects of antioxidant supplements on cardiovascular mortality (Lee 2004), prostate cancer (Lawson 2007), and lung cancer (Slatore 2007). Cardiovascular diseases and cancers of the lung and gastrointestinal tract are the leading causes of death worldwide (Ferlay 2004; Lopez 2006; Mathers 2006). Reactive oxygen species in moderate concentrations are essential mediators of reactions by which unwanted cells are deleted from the body. Schulz et al found that the inhibition of reactive oxygen species formation in cells decreases the life span of nematodes (Schulz 2007). Excessive suppression of free radicals may have unwanted consequences to our health (Salganik 2001).

There are still many gaps in our knowledge of the mechanisms of bioavailability, biotransformation, and action of antioxidant supplements (Haenen 2002). Antioxidant supplements in pills are factory processed, biochemically unbalanced, and apparently unsafe compared to their naturally occurring counterparts (Herbert 1997; Seifried 2003). Antioxidant supplements also possess pro‐oxidant effects (Podmore 1998; Paolini 1999; Murata 2000; Lee 2003; Duarte 2005). A balanced diet typically contains safe levels of antioxidant vitamins and trace elements (Camire 1999). Some of the trials included in our review investigated the effects of antioxidant supplements administered at doses significantly higher than those found in a balanced diet. Some trials used dosages well above the recommended tolerable upper intake levels (Anonymous 2000a; Anonymous 2000b). The majority of the trials were conducted in middle‐ and high‐income countries among populations with already sufficient levels of antioxidant vitamins and trace elements. This might be a cause for the lack of protective effects and for the increase in mortality of antioxidant supplements.

For many years scientists have been concerned about possible harm caused by antioxidants (Herbert 1994; Schwartz 1996). However, large expectations and unconfined belief in the cancer preventive potential of the antioxidants have overwhelmed these concerns. The available data on adverse effects of antioxidant supplements are still limited (Mulholland 2007) and often underreported (Woo 2007). Less than 1% of all adverse effects associated with antioxidant supplements are notified (Woo 2007). Consumers presume antioxidant supplements to be safe and use them without physicians' supervision (Webb 2007). We find that it is high time that antioxidant supplements are moved from the free 'over the counter' market to the prescription regulatory market.

Certain potential limitations of this review warrant consideration. We are dealing with a group of trials, which by the nature of their topic, that is, preventive efforts over a number of years, may have inherent mistakes. We found a number of inconsistencies among the different reports of the individual trials. We tried in all cases to obtain clarification from the authors. However, this was not always possible. Diagnostic criteria and timing of screening differed among the trials or were not always well defined. We have compared the intervention effects of antioxidants of different types and their influence on different gastrointestinal cancers with different aetiology, biology, and epidemiology. Moreover, the examined populations varied. The effects of supplements were assessed in the general population, participants with premalignant conditions of gastrointestinal tract, and participants coming from other patient groups, primarily with non‐gastrointestinal diseases. The variable risk to develop cancer can influence the results. These populations mostly came from countries without overt deficiencies of specific supplements. Accordingly, we are unable to assess the influence of antioxidant supplements on gastrointestinal cancer occurrence in populations with specific needs. In general, the risk of individual cancer was below 1%. This may make it difficult to detect any effects ‐ beneficial or harmful.

The reporting of the occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers and overall mortality in the randomised trials was not always sufficient and consistent. Regarding gastrointestinal cancers, all included trials gave results. However, from one trial (NIT1 1993) we were unable to extract data for each arm separately. Data are awaited from another trial (WACS 2007). Of 20 trials included in our systematic review, only 14 (70%) reported overall mortality. We tried to obtain additional information from the authors but without success. Therefore, outcome reporting bias could influence the result of our meta‐analysis. Outcome reporting bias is defined as selective reporting of some results in trial publications and represent a threat to validity of meta‐analysis (Chan 2004a; Chan 2004b; Chan 2005; Williamson 2005; Furukawa 2007). We are well aware of the difficulties in collecting data on outcomes in clinical trials focusing on safety and efficacy evaluations. The worst result of outcome reporting bias and suppression of some significant or non‐significant findings could be the use of harmful interventions. Most of the included trials lacked detailed information on disease‐specific causes of mortality as well as separate reporting of cancers according to sex.

The choice of statistical model for performing meta‐analysis is important. The fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis assumes that the true intervention effect is the same in every randomised trial, ie, the effect is fixed across trials. The random‐effects model assumes that the effects being estimated based on the different randomised trials differ, but follow some general distribution. When there is no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), then fixed‐ and random‐effects models meta‐analyses tend to give the same result. If heterogeneity increases, the estimated intervention effect and the corresponding 95% confidence interval will differ in the two models. The trials in the present review had clinical heterogeneity. This argues in favour of the random‐effects model. The standard random‐effects model used in RevMan Analysis is the DerSimonian and Laird method, which models the known differences between trials by incorporating a variance parameter tau to account for across‐trial variation (DerSimonian 1986). Adoption of the random‐effects model in meta‐analysis permits inferences to a broader population of studies than the fixed‐effect model does namely because it includes the parameter tau in the model. The use of the random‐effects model may come at a price. If there is between‐trial heterogeneity, then the weight of the large trials (usually providing more realistic estimates of intervention effects) is reduced. At the same time, the weight of small trials (usually providing more unrealistic estimates of intervention effects due to 'bias' (systematic errors) and 'chance' (random errors)) increases. Therefore, we also analysed our meta‐analyses with the fixed‐effect model.

We only examined certain antioxidant supplements that had been tested in randomised trials. Our results should not be translated to the potential effects of fruits and vegetables, which are rich not only in antioxidants but also in a number of other substances. In spite of intensive research, it is still not clear exactly which specific dietary constituents of fruits and vegetables might have anticarcinogenic properties. The results of randomised clinical trials on cancer prevention with high intake of fruits and vegetables are inconsistent and vary by cancer type and affected organ (Neuhouser 2003; Nouraie 2005). Recently published results of a randomised trial found non‐significant effect of high fruit and vegetable diet on colorectal adenoma recurrence (Lanza 2007). Results of epidemiologic studies differ significantly too, reporting beneficial or null effects (Larsson 2006; Freedman 2007; Koushik 2007; Kubo 2007; Takachi 2007).

Our results are in accordance with the results of other recently published meta‐analyses and systematic reviews (Caraballoso 2003; Vivekananthan 2003; Bjelakovic 2004a; Bjelakovic 2004b; Miller 2005; Bjelakovic 2006; Bjelakovic 2007), as well as recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and British Nutrition Foundation for the use of vitamin supplementation (McKevith 2003; Morris 2003; USPSTF 2003).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no convincing evidence that the studied antioxidant supplements have beneficial effect on the occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers or on overall mortality. Beta‐carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, and/or vitamin E seem to increase overall mortality. Therefore, we cannot recommend the use of these antioxidant supplements as a preventive measure.

Implications for research.

Selenium may potentially possess beneficial effects on gastrointestinal cancers. The potential anticarcinogenic effects of selenium have to be elucidated. Randomised clinical trials with selenium are ongoing and further trials may be needed.

The significant association between unclear or inadequate methodological quality and overestimation of intervention effects has again focused on the need for more objective assessment of preventive and therapeutic interventions.

National and international laws and regulations should require that anything sold to the public claiming health benefits is subjected to adequate assessment of benefits and harms before market release. We suggest that antioxidant supplements should be regulated as drugs.

Researches wishing to examine the influence of antioxidant supplements on gastrointestinal cancers or other diseases should adopt the CONSORT statement while performing and reporting randomised clinical trials (CONSORT ‐ Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials: www.consort‐statement.org).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 30 September 2007 | New search has been performed | Six new trials were added. |

| 30 September 2007 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions did not change. |

Notes

The Protocol for this Review was published with a title 'Antioxidats for preventing gastrointestinal cancers'.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to all participants in the randomised clinical trials. We thank Ronald L. Koretz, Contact Editor of The CHBG for very helpful comments on the review. We thank Mike Clarke, The Director of The UK Cochrane Centre; David Forman, The Co‐ordinating Editor of The Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group; John McDonald, The Co‐ordinating Editor of The Cochrane Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group, and Peer Wille‐Jørgensen, The Co‐ordinating Editor of The Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group for their expert comments during preparation of the protocol. We thank Yan Gong and Bodil Als‐Nielsen for useful advice and comments, Yan Gong and Wendong Chen for translation of Chinese articles, and Maoling Wei, The Chinese Cochrane Centre, for performing searches on the Chinese Database and providing us with some articles. We are grateful to Jarmo Virtamo, Nea Malila, Julie Buring, Nancy Cook, Pelayo Correa, John A Baron, Howard Sesso, Serge Hercberg, Mark Thornquist, Matt Barnett, Gary Goodman, I‐Min Lee, Martyn Plummer and Mitchell H. Gail for the information on the trials they were involved in.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antioxidants versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers in trials with a low or high risk of bias | 18 | 174019 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.83, 1.06] |

| 1.1 Trials with low risk of bias | 12 | 163439 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.96, 1.13] |

| 1.2 Trials with high risk of bias | 6 | 10580 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.43, 0.80] |

| 2 Occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers ‐ generation of the allocation sequence | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Adequate | 12 | 162948 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.98, 1.13] |

| 2.2 Unclear/Inadequate | 6 | 10580 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.43, 0.80] |

| 3 Occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers ‐ allocation concealment | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Adequate | 13 | 163558 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.98, 1.13] |

| 3.2 Unclear/Inadequate | 5 | 9970 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.41, 0.78] |

| 4 Occurrence of gastrointestinal cancers ‐ follow‐up | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Adequate | 16 | 166021 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.87, 1.10] |

| 4.2 Unclear/Inadequate | 2 | 7507 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.51, 1.02] |

| 5 Occurrence of all gastrointestinal cancers ‐ different antioxidants | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Beta‐carotene | 4 | 37046 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.80, 1.35] |

| 5.2 Vitamin C | 1 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.3 Vitamin E | 1 | 14573 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.93, 1.34] |

| 5.4 Selenium | 5 | 11110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.46, 0.75] |

| 5.5 Vitamin A and beta‐carotene | 1 | 18314 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.91, 1.32] |

| 5.6 Beta‐carotene and vitamin C | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.90 [0.12, 70.52] |

| 5.7 Beta carotene and vitamin E | 1 | 14565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.98, 1.41] |

| 5.8 Vitamin A, riboflavin, and zinc | 1 | 610 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.30, 5.91] |

| 5.9 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E | 2 | 22516 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.80, 1.16] |

| 5.10 Vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium | 1 | 3365 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.60, 1.68] |

| 5.11 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium | 1 | 13017 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.53, 1.32] |

| 5.12 Combination of antioxidants (13 vitamins and 13 minerals) | 1 | 3318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.88, 1.25] |

| 6 Occurrence of different gastrointestinal cancers ‐ all antioxidants | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Occurrence of oesophageal cancer | 9 | 126288 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.89, 1.28] |

| 6.2 Occurrence of gastric cancer | 12 | 157300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.97, 1.33] |

| 6.3 Occurrence of small intestine cancer | 1 | 39876 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.00 [0.45, 35.79] |

| 6.4 Occurrence of colorectal cancer | 9 | 153972 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.86, 1.09] |

| 6.5 Occurrence of pancreatic cancer | 6 | 142947 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.90, 1.50] |

| 6.6 Occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma | 9 | 130674 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.56, 1.14] |

| 6.7 Occurrence of biliary tract cancer | 2 | 52893 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.21, 1.78] |

| 7 Occurrence of oesophageal cancer | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Beta‐carotene | 2 | 14741 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.25, 2.30] |

| 7.2 Vitamin E | 1 | 14573 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.72, 2.96] |

| 7.3 Selenium | 1 | 1312 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.08, 2.07] |

| 7.4 Vitamin A and beta‐carotene | 1 | 18314 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.90, 2.29] |

| 7.5 Beta‐carotene and vitamin E | 1 | 14565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.59, 2.56] |

| 7.6 Vitamin A, riboflavin, and zinc | 1 | 610 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.30, 5.91] |

| 7.7 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E | 1 | 20536 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.71, 2.01] |

| 7.8 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium | 1 | 13017 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.14, 7.16] |

| 7.9 Combination of antioxidants | 1 | 3318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.76, 1.22] |

| 8 Occurrence of gastric cancer | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Beta‐carotene | 4 | 37046 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.79, 1.59] |

| 8.2 Vitamin C | 1 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.3 Vitamin E | 1 | 14573 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.90, 1.88] |

| 8.4 Selenium | 1 | 5033 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.44, 1.31] |

| 8.5 Vitamin A and beta‐carotene | 1 | 18314 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.46, 1.73] |

| 8.6 Beta‐carotene and vitamin C | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.90 [0.12, 70.52] |

| 8.7 Beta‐carotene and vitamin E | 1 | 14565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.98, 2.01] |

| 8.8 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E | 2 | 22516 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.78, 2.00] |

| 8.9 Vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium | 1 | 3365 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.60, 1.68] |

| 8.10 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium | 1 | 13017 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.14, 7.16] |

| 8.11 Combination of antioxidants | 1 | 3318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.89, 1.58] |

| 9 Occurrence of colorectal cancer | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Beta‐carotene | 3 | 36812 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.79, 1.51] |

| 9.2 Vitamin E | 2 | 24114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.87, 1.39] |

| 9.3 Selenium | 1 | 1312 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.22, 1.05] |

| 9.4 Vitamin A and beta‐carotene | 1 | 18314 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.25] |

| 9.5 Beta‐carotene and vitamin E | 1 | 14565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.89, 1.63] |

| 9.6 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E | 1 | 20536 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.65, 1.07] |

| 9.7 Beta‐carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium | 1 | 13017 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.49, 1.58] |

| 10 Occurrence of pancreatic cancer | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Beta‐carotene | 2 | 36640 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.54, 1.90] |

| 10.2 Vitamin E | 1 | 14573 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.67, 1.39] |

| 10.3 Vitamin A and beta‐carotene | 1 | 18314 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.84, 2.09] |

| 10.4 Beta‐carotene and vitamin E | 1 | 14565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.65, 1.35] |