Abstract

Background

African-American women have the highest breast cancer death rates of all racial/ethnic groups in the US. Reasons for these disparities are multi-factorial, but include lower mammogram utilization among this population. Cultural attitudes and beliefs, such as fear and fatalism, have not been fully explored as potential barriers to mammography among African-American women.

Objective

To explore the reasons for fear associated with breast cancer screening among low-income African-American women.

Methods

We conducted four focus groups ( = 29) among a sample of African-American women at an urban academic medical center. We used trained race-concordant interviewers with experience discussing preventive health behaviors. Each interview/focus group was audio-taped, transcribed verbatim and imported into Atlas.ti software. Coding was conducted using an iterative process, and each transcription was independently coded by members of the research team.

Main Results

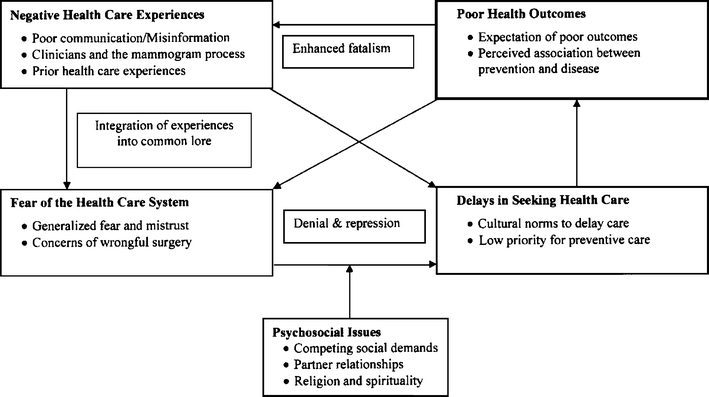

Several major themes arose in our exploration of fear and other psychosocial barriers to mammogram utilization, including negative health care experiences, fear of the health care system, denial and repression, psychosocial issues, delays in seeking health care, poor health outcomes and fatalism. We constructed a conceptual model for understanding these themes.

Conclusions

Fear of breast cancer screening among low-income African-American women is multi-faceted, and reflects shared experiences within the health care system as well as the psychosocial context in which women live. This study identifies a prominent role for clinicians, particularly primary care physicians, and the health care system to address these barriers to mammogram utilization within this population.

KEY WORDS: breast cancer, mammography, African-Americans, barriers to healthcare

INTRODUCTION

African-American women are more likely to die from breast cancer than any other racial/ethnic group in the US.1 Nationally, African-American women have a 35% higher breast cancer mortality rate than white women (33.8 deaths per 100,000 versus 25.0, respectively) and in Chicago, the mortality rate for black women is 73% higher than white women (40.5 deaths per 100,000 compared with 23.4 respectively).1,2 This racial gap in breast cancer mortality has steadily increased over the past decade.1,2

The reasons for the disparities in breast cancer outcomes are multi-factorial, and have been attributed to differential rates of screening mammography, delays in the diagnostic evaluation of breast abnormalities, biological differences, and inequalities in cancer treatment.3,4 Although the disparity in screening mammography rates between African-American and white women has narrowed, there are subpopulations of African-Americans who remain at high risk for under-screening, including the uninsured, women without a primary care provider and women of lower socioeconomic status.3,5–7

There are many barriers to breast cancer screening among medically underserved women. Financial and logistical barriers, such as cost, insurance, transportation and childcare are particularly relevant to this population.3 Although less well studied, cultural attitudes and beliefs, such as cancer fear and fatalism, have also been identified as barriers to mammogram utilization among African-Americans.8–11 There is a paucity of research investigating the root causes of this fear and exploring which phenomena contribute to the sense of cancer fatalism in this population. Spirituality and religion have been identified as major determinants of fatalism, in that women who “turn it over to God” may feel a loss of control over their own health.9,10

We sought to explore the underlying reasons for the fear and fatalism associated with breast cancer screening among low-income African-American women in Chicago.

METHODS

Study Design

This research project was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rush University Medical Center. We conducted four focus groups with a total of 29 participants. Enrollment was discontinued after theme saturation was reached. Each focus group consisted of 6–8 people and lasted approximately 90 minutes. Because research has shown that racial concordance fosters a “safe environment” that facilitates conversation, accurate data collection, and comprehension of cultural phenomena, each focus group was led by experienced African-American moderators.12

Participant Recruitment

Our study targeted low-income, medically underserved African-American women who lived in urban, economically challenged neighborhoods throughout Chicago. Participants were recruited from public housing developments, a transitional housing program and a church-based outreach program with the use of culturally-appropriate, low-literacy materials describing the study. Partnerships with grassroots community groups, tenant council organizations, and local community leaders were utilized to facilitate recruitment efforts. Eligible participants included African-American women at least 40 years old. Participants received a $15 gift certificate to a local grocery store as a participation incentive.

Data Collection and Analysis

A short self-report questionnaire was administered before each focus group, which contained questions about demographic information, health screening behaviors (clinical breast examinations, mammograms and Pap tests), and breast cancer knowledge (i.e. mammogram definition and efficacy).

The focus groups were guided by a questioning route based on the validated conceptual models of health belief and self-efficacy.13,14 We used a funnel approach to our discussion, beginning with questions that were broadest in scope and ultimately focusing on psychosocial barriers (e.g. fear) to mammography. We started our discussion with the following: “We would like to hear your thoughts on mammography. What do you know about mammograms and what do you think of them?” All questions were open-ended, and we used probes to query unaddressed areas that we believed to be rich in content. In order to capture the full range of cross-generational attitudes and cultural norms, we also asked participants about the attitudes and experiences of friends, relatives, and neighbors regarding mammograms.

Each focus group was audiotaped, transcribed verbatim and imported into Atlas.ti software. Each researcher independently read the transcripts and, using the method of content analysis, identified broad themes in the data.15 A coding structure was developed using an iterative process and reviewed by the research team (MP, JS, RM). Differences of opinion were resolved through discussion and consensus. The investigators applied the final coding scheme to each transcript using Atlas.ti software. A conceptual framework was created based on predominant themes that arose from the data.

RESULTS

Twenty-nine women participated in our study. Of these, 24 (83%) had completed high school or less, 25 (86%) had an annual household income of less than $25,000 and 22 (76%) were unemployed (Table 1). Only one woman in our study had a history of breast cancer. Of the 29 women interviewed, only 16 (55%) reported having a mammogram within the prior 2 years (Table 2). Breast cancer screening knowledge (definition of a mammogram, mammogram efficacy) was higher than the self-reported adherence with screening mammography (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics, = 29

| (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |

| 40–49 | 11 (38) |

| 50–65 | 16 (55) |

| >65 | 2 (7) |

| Annual household income | |

| <$10, 000 | 16 (55) |

| $10,000 to< $25,000 | 9 (31) |

| >$25,000 | 4 (14) |

| Education | |

| <12 | 13 (45) |

| 12 | 11 (38) |

| >12 | 5 (17) |

| Insurance status | |

| Insured | 10 (34) |

| Uninsured | 19 (66) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 22 (76) |

| Blue collar | 4 (14) |

| White collar | 2 (7) |

| Retired | 1 (3) |

| Prior history of breast cancer | 1 (3) |

Table 2.

Breast Cancer Screening Knowledge and Behaviors, = 29

| (%) | |

|---|---|

| Last self-reported mammogram | |

| ≤2 years | 16 (55) |

| 2–5 years | 8 (28) |

| ≥5 years | 5 (17) |

| Correct knowledge of mammogram definition | |

| Yes | 20 (69) |

| No | 9 (31) |

| Awareness that mammograms can detect a mass before self exams | |

| Yes | 22 (76) |

| No | 7 (24) |

Several major themes arose in our exploration of fear and other psychosocial barriers to mammograms: negative health care experiences, fear of the health care system, denial and repression, psychosocial issues, delays in seeking health care, poor health outcomes, and fatalism. These themes are discussed in detail below.

Negative Health Care Experiences

This theme included the individual experiences of women in the focus groups as well as those of their friends, family and neighbors. We classified these experiences as either real or perceived. Negative experiences were often the result of poor communication and/or misinformation, and generally fell into two areas: 1) clinicians and the mammogram process, or 2) prior health care experiences.

Clinicians and the Mammogram Process

Women reported fear and concern about negative interpersonal interactions with clinicians, such as being treated with disrespect. Underlying feelings of physician mistrust were reinforced by new encounters with providers during the mammogram process. For example, many women had unpleasant emotional reactions to the wait time associated with radiological film development. Some felt intentionally abandoned and afraid during this waiting period. Others assumed that the mammograms were being interpreted by their doctor in secret, without consultation or disclosure of the results, rather than the more likely scenario where the film was being processed and evaluated for quality by a technician.

But the thing that I don’t feel comfortable [about is] when you go to get a mammogram, the doctor tells you to ‘sit down.’ A bunch of doctors come over to check your mammogram and they make you wait and then they come and say ‘Oh that’s nothing.’ You’ve been waiting for half an hour for them to come and tell you that’s nothing. I mean, I don’t know who they can fool, but they don’t fool me that’s for sure.

You see, when they left me, there wasn’t nobody with me to talk to me...

As anticipated, women reported fear about the process of mammography itself, including pain and discomfort. However, additional fears arose about the mammogram process that were distinct from physical discomfort. One woman told the following story:

When I got in the hospital to take the mammogram they put me in the machine, put my breast in a machine, and it got hung up... and she couldn’t get it out... She said ‘I’m sorry, but this is an old machine, we need a new one... and I’ve got to leave you to go get some help,’ and that frightened me. I said ‘if you ever get me out of here, you’ll never get me in again.’... And then they [left] me in the room, and they’re gone and I’m thinking the radiation [is] coming down in my body. So, I know I’m full of radiation, and that’s why I’ll never come back.

This story reflects a negative experience that has components that are both real (her breast was actually trapped in the machine for a period of time) and perceived (radiation was not being continually delivered while her breast was in the mammogram equipment, but this misunderstanding was never clarified).

Prior Health Care Experiences

Women also extrapolated negative, fear-inducing health experiences from other areas of health care (such as screening for tuberculosis or treatment of chronic disease) onto their expectations and fears about breast cancer screening. These prior experiences generally reflected issues of disrespect and perceived discrimination.

It took me to make a complaint about the doctor who took care of me to be treated right at the hospital. It’s not necessary. Why do I have to jeopardize somebody’s job for me to be treated right? I’m a human being; I’m not a dog. Even dogs get treated better than us... Do you think these people would take extra care during a mammogram? They don’t care about your pain.

In several instances, it was clear that the health care team failed to adequately communicate with the patient about what was happening and why. This lack of information left women feeling vulnerable and had a negative overall impact on how they experienced and interpreted their health care encounter.

[After I was hospitalized for pneumonia], what I didn’t like is why did they have to put the gloves and masks on? They came in with all these gloves and masks. And it made me feel scared and uncomfortable kind of like you were... I don’t know. My door had to stay shut... It makes me not want to go back there for anything that I don’t have to.

Integration of Experiences

We found that the stories and experiences women told about getting mammograms were generally negative. No one recalled any positive stories being shared within the community—those of women having pleasant or pain-free experiences with a mammogram, women feeling informed and empowered about the breast cancer screening process, or of women diagnosed with early breast cancer who went on to live healthy, cancer-free lives. Moreover, we found that women’s individual experiences with screening mammography and breast cancer were integrated into communal folklore that impacted the attitudes and beliefs of others who had no prior experience with breast cancer screening.

Because they hear a horror story from somebody else and word of mouth goes around and that discourages a whole community.

Well, I’ve never had [a mammogram] in my life, and the stories that I heard about them really discouraged me a lot, you know? Because all the ladies that I’ve talked to that had them talk about how painful that the mammogram is and how bad it hurts, you know?

Fear of the Health Care System

Another important theme was a generalized fear of the health care system and clinicians. Some of this represented a fear of the unknown—a fear that stemmed from a lack of knowledge and information about what to expect during the process of having a mammogram.

Young women today are scared. Young women in this building today may not even [go] to the doctor. They’re afraid. If you come in and [explain] it down to them, they won’t be scared.

Okay, my thing would be—maybe have someone to come out and explain the routine because [there are] probably some out there that [have] fear like I do.

Generalized Fear and Mistrust

Other dimensions of this generalized, nonspecific fear arose in part from issues of mistrust. In these situations, women often were unable to articulate the underlying reasons for their fear, but were acutely aware of its presence.

[The doctor] would have to go ahead of me [for the mammogram] first, and I see how she comes out. [laughter] [I’d say to the] doctor: ‘Put your breast in there and make sure, and then I know I’m okay to go in behind you.’

I’m scared of the doctor, and I don’t know why, but I just get scared.

They asked me if I had a mammogram in the past year and I hadn’t... I was just scared.

Concerns of Wrongful Surgery

Some women feared having unnecessary surgery or mastectomy. Some of this fear of “wrongful surgery” was due to inaccurate health beliefs and misinformation. For example, the well-documented myth that surgery causes cancer to spread (and would therefore be unnecessary or harmful) was prevalent among this group of African-American women, despite health education efforts over the prior decades to eradicate such beliefs.16 Moreover, some fears arose from a mistrust of the medical system, reflecting concerns about physician incompetence and/or medical errors (unintentional harm), or concerns about unethical experimentation (intentional harm).

At one point they were saying that a lot of the test results [that] had came back from the past were inaccurate, which caused them to have unnecessary surgeries—things like that—because the tests findings were not right. So through the years, I hear the word mammogram, and I’ll say ‘Okay if something hurts me I’ll go, but if it doesn’t hurt...’

Denial and Repression

A common psychological response to negative feelings and fear is denial and repression, particularly when the person feels otherwise powerless to control or mitigate the situation.17 Women reported using denial of health symptoms as a coping mechanism to deal with the fear and uncertainty associated with potential illness. In these circumstances, proactive screening for breast cancer would necessarily involve acknowledging a vulnerability to disease and disability.

When I had breast cancer, I didn’t think I was having a problem until my kids seen that I was getting real sick.

Say for instance if you probably know you got breast cancer but you ain’t going to the doctor... Because this lady told me she’s scared of the doctor and her breast is really gone.

Psychosocial Issues

There were a variety of psychosocial factors described that hindered women’s willingness to participate in screening for breast cancer, including concerns about competing social demands, intimate partner relationships, and spirituality.

Competing Social Demands

The complex social and environmental hazards caused many women to focus their priorities on the management of acute issues, both medical (e.g. asthma exacerbations, injuries, and destabilization of chronic disease) and non-medical (e.g. neighborhood violence, housing issues, and substance abuse). As a result, preventive care measures such as breast cancer screening became a lower priority for many women in this population, not only because of the immediacy of competing psychosocial demands, but also because of the reduced expectations for health and longevity.

Sometimes our social background discourages us, our people, from getting any type of care, medical care. So, we really need to find out the social backgrounds... like family problems or maybe other health problems or they could just be discouraged because of their surroundings. What’s the use of caring about having a mammogram or having a Pap smear, who cares? Or maybe there’s a drug problem or something like that. So these are things that could limit, could really discourage, anyone from even wanting to be concerned about their care.

Partner Relationships

Some women reported having fears of downstream psychosocial sequelae that might arise from a diagnosis of breast cancer. The potential impact of a mastectomy on body image and interpersonal relationships was a commonly reported concern. For example, there was concern that having a mastectomy would precipitate abandonment by their partners. For low-income women, meeting financial and caregiving obligations at home may make sustaining such relationships particularly important.

Her husband rejected her when she had her breast removed. And she really went through extra trauma because of that.

If I had to have [a breast] removed and my husband was still living with me... it would cause me to have concern. The first thing to come to mind is ‘Oh, he’s going to get another woman now... I’m no longer attractive.’

Religion and Spirituality

There is a significant body of literature describing the role of spirituality within the African-American community and its impact on health behaviors.8–11 While women discussed how their faith in God helped alleviate fears about future uncertainties, disease and death, by “leaving it in God’s hands,” some of the women abdicated their own agency in preventing breast cancer.

So I don’t worry about [breast cancer screening] because only God can decide when it’s my time to go.

Everything depends on how much faith you [have].

I know I could die tomorrow, so I don’t worry about [screening for breast cancer].

Delays in Seeking Health Care

Another prominent theme was delayed health care seeking behaviors. Women described community cultural norms to delay care and prioritize acute or deteriorating conditions over preventive health care.

I know what you mean when you say Black women don’t believe in going to the doctor, and they don’t go unless something happens. Then she’ll go, but sometimes it’s too late then.

If she finds out something, she may have to have her breast removed... So she’s like, ‘I’d rather not know just yet.’

Poor Health Outcomes

Women in our study shared experiences and stories about breast cancer that reflected late-stage diagnoses and poor health outcomes. We heard no accounts of early diagnosis, the use of breast-conserving therapy or of treatment cures. Mastectomy, chemotherapy and death were generally expected treatments and outcomes associated with a breast cancer diagnosis. We heard multiple stories of women having metastatic disease at the time of breast cancer diagnosis, where women reportedly had a screening mammogram and were ultimately diagnosed with late-stage cancer. As a result, women described negative associations between prevention and disease, such that they were not just worrying about being diagnosed with breast cancer when they went for a mammogram, but were actually expecting it.

[Women] might feel that every time you go for your mammogram, you got cancer.

When it comes to the Pap smear, I [am] all scared and holding on all tight and I’ve had seven babies. [I’m afraid of] what they might find. That is my biggest fear. After that first [mammogram], I was a nervous wreck. I figured they would tell me I had breast cancer. And after they told me to sit down—Oh, I really got nervous. The doctor asked me what was wrong, and I told him I was just afraid. So he assured me that it wasn’t cancerous.

Enhanced Fatalism

The cancer literature has documented a prevailing sense of cancer fatalism among African-American women, but it has primarily been attributed to underlying spiritual beliefs and an external locus of control.9 Women in our study described a sense of fatalism that was grounded in perceptions of the community’s experience with breast cancer rather than religion.

I just thought you just died; if you had breast cancer you was gonna die anyway.

I didn’t know that it was a possibility to live after you had breast cancer or had been found having breast cancer.

Everybody I know who had breast cancer [has] died. I [wasn’t aware] of anything different.

We used the themes from our study to create a conceptual model that describes the relationships between fear and delayed breast cancer screening behaviors (Fig. 1). In our model, negative health care experiences (which were often the result of poor patient/provider communication) are shared throughout the community and individually internalized to create a more generalized, nonspecific fear of clinicians and the health care system, even among women who have never had a mammogram. Women in our focus groups described using denial and repression as coping strategies for this fear that resulted in cultural norms to delay care and not seek preventive care, such as breast cancer screening. Thus, fear of the health care system and subsequent denial/repression is one mechanism (of many) by which negative health care experiences may facilitate delays in seeking health care. These delays in health care lead to worse health outcomes among women in the community, such as late-stage diagnoses and higher mortality rates. These observed poor health outcomes led some women to equate screening mammograms with an impending breast cancer diagnosis, contribute to fears of the health care system, and have created a sense of cancer fatalism within the community. Such attitudes and beliefs influence women’s perceptions of their own experiences within the health care system, where inadequate information reinforces the perception of a bad or negative experience.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of fear, fatalism and breast cancer screening among low-income African-American women.

Discussion

Our research identifies a prominent role for clinicians and the health care system in creating and perpetuating a sense of fear about breast cancer screening. Perceptions of disrespect, mistrust and unfair treatment were prevalent in our study and are worthy of further attention and research. There is a long, unfortunate history of unethical experimentation and substandard medical treatment in the US that has given rise to mistrust of physicians and health care organizations among African-Americans.18,19 Women in our study reported concerns about physician incompetence and/or medical errors (unintentional harm), or concerns about unethical experimentation (intentional harm). For example, women feared being subjected unnecessary mastectomy, and prior literature suggests that African-Americans may be less likely to receive breast-conserving therapy (lumpectomy) than whites.20 Jacobs et al. also identified issues of physician distrust, concerns about technical incompetence and experimentation, and racism in their work exploring trust among African-American patients.19 Physician bias, either conscious or unconscious, has been recognized as a potential contributor to health disparities and could account for some of the negative encounters women in our study experienced.21,22 Physician cultural competency training is one potential solution. For example, Margolis et al. found that women who received clinical breast exams by culturally sensitive providers were more likely to obtain subsequent screening mammograms in comparison to the control group.23 Improved communication skills and cultural awareness has the potential to increase patient trust, improve the patient-provider relationship and potentially reduce perceived and/or real occurrences of unfair treatment and discrimination.

Some of the fear associated with breast cancer screening arose from the mammogram process itself. Physicians and health systems can improve the quality of breast cancer screening available to patients by reducing the wait time during a mammogram procedure, updating radiology equipment, enhancing personnel resources and infrastructure, and training radiology technicians to educate patients and “talk them through” the mammogram process.

Much of the fear women discussed in our study arose from a lack of accurate information and poor communication between patients and their health care providers (e.g. physicians, mammogram technicians, nurses) about the mammogram process. Oliver et al. documented that African-Americans are less likely than whites to have their physicians discuss treatment plans and preventive health care during clinical encounters, which suggests that racial disparities may exist in the amount of information communicated to African-American women about screening mammograms.24 Our research indicates that African-American women have an increased need for such information, making comprehensive communication about breast cancer screening particularly important among this population. A fear of the unknown, the presence of misinformation within the community, and misinterpretations about standard breast cancer screening protocols accounted for a significant portion of the fear that women described. As such, there is an important role for patient education, with unique tasks for clinicians and community health educators.

Physicians, particularly primary care physicians, can play an important role in communicating with patients and educating them about what to expect during a screening mammogram, in order to help women interpret their experiences correctly and limit the misperceptions that may arise from underlying feelings of mistrust of the health care system. For example, women should be informed that they may be asked to wait while the radiographs are being developed to ensure a good quality picture and that the mammogram will likely be interpreted at a later time by the physician.

There is a different, but equally important, role for peer educators and community health workers (CHWs) in addressing issues of fear among low-income African-American women. In addition to reinforcing physician education and communicating with women about standard mammography procedures, CHWs can arrange for community-based breast cancer screening through mobile mammography programs and help patients navigate complex health care systems from screening through follow-up.25,26 More importantly, they can add positive stories to the community folklore about mammograms that can begin to modify beliefs and attitudes about breast cancer screening, and change the cultural norms that promote delaying health care and devalue the role of preventive health care.

This study has several limitations. First, it is comprised of a narrowly defined study group in a single urban area (Chicago) that is small in number. As such, our findings may have limited generalizability to women of different racial or socioeconomic groups, or to women living in different environments. However, our goal was to explore the experiences and attitudes of urban, low-income African-American women about breast cancer screening and determine what factors account for the fear that prevents many such women from full participation in the breast cancer screening process. As such, our findings shed important light in an area that has yet to be fully explored. A second limitation is that a large proportion (nearly 40%) of study participants were women in their forties, an age group that has historically had controversial recommendations regarding screening mammography.27,28 However, since 2002, all US organizations with breast cancer recommendations have promoted screening mammograms beginning at age 40.28,29

Our study demonstrates that fear of breast cancer screening among low-income African-American women is multi-faceted, and reflects shared experiences within the health care system as well as the psychosocial context in which women live. There is a need for greater patient education by physicians and health educators to help address this fear and promote mammogram utilization among this population.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Open Society Institute, Medicine as a Profession (MAP) fellowship program and Susan G. Komen for the Cure. Dr. Peek is currently supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development program. An abstract of this work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine 28th Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, May 11–14, 2005.

Conflict of Interest The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.SEER Cancer Statistics. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed July 14, 2008.

- 2.Hirshman J, Whitman S, Ansell D. The black:white disparity in breast cancer mortality: the example of Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:323–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Peek ME, Han JH. Disparities in screening mammography: Current status, interventions and implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:184–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Masi CM, Blackman DJ, Peek ME. Interventions to enhance breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment among racial and ethnic minority women. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:195S-242S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Katz SJ, Hofer TP. Socioeconomic disparities in preventive care persist universal coverage: breast and cervical cancer screening in Ontario and the United States. JAMA. 1994;272;530–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Blackman DK, Bennet EM, Miller DS. Trends in self-reported use of mammograms (1989–97) and papanicuolaou tests 1991–97—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;4:1–22. [PubMed]

- 7.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States. Results from the 2000 National Health Information Study. Cancer. 2003;97:1528–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Phillips JM, Cohen MZ, Moses G. The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare. Breast cancer screening and African American women: Fear, fatalism, and silence. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:561–71. [PubMed]

- 9.Jennings K. Getting black women to screen for cancer: Incorporating health beliefs into practice. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 1996;8:53–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mansfield CJ, Mitchell J, King DE. The doctor as God’s mechanic? Beliefs in the southeastern United States. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:399–409. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Guidry JJ, Matthews-Juarez P, Copelan VA. Barriers to breast cancer control for African American women. Cancer. 2003;91:318S-23S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Jackson J. Methodologic approach. In Jackson JS, ed. Life in black America. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

- 13.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health Behavior and Health Education. Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco: Wiley: 2002.

- 14.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Loehrer PJ, Greger HA, Weinberger M, Musick B, Miller M, Nichols C, Bryan J, Higgs D, Brock D. Knowledge and beliefs about cancer in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. Cancer. 1991;68:1665–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):358–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, Whitaker EE, Warnecke RB. Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:642–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Nattinger AB, Gottlieb MS, Veum J, Yahnke D, Goodwin JS. Geographic variation in the use of breast-conserving treatment for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1102–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.vanRyn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Finucane TE, Carrese JA. Racial bias in presentation of cases. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:120–1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Margolis KL, Lurie N, McGovern PG, Tyrrell M, Slater JS. Increasing breast and cervical cancer screening in low-income women. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:515–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Oliver MN, Goodwin MA, Gotler RS, Gregory PM, Stange KC. Time use in clinical encounters: are African-American patients treated differently? J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93:380–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Brownstein JN, Cheal N, Ackerman SP, Bassford TL, Campos-Outcalt D. Breast and cervical cancer screening in minority populations: a model for using lay health educators. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7:321–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Anderson, MR, Yasui Y, Meischke H, Kuniyuki A, Etzioni R, Urban N. The effectiveness of mammography promotion by volunteers in rural communities. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kerlikowski K. Efficacy of screening mammography among women aged 40 to 49 years and 50 to 69 years: comparison of relative and absolute benefit. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1997;22:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Peek ME, Ganschow P, Elmore J. Screening Mammography. In Ganschow P, Norlock F, Jacobs E, Marcus E, eds. A Physician’s Guide to Breast Health and Benign Breast Disease. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2004.

- 29.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:344–6. [DOI] [PubMed]