Abstract

Blast injuries to the hand are not just a wartime phenomenon but also quite common in rural communities throughout northern California. The purpose of this study is to review our experience with blast injuries in the community and review the most common patterns in an attempt to identify the pathomechanics of the hand injury and the reconstructive procedures that are required. This is a retrospective study of blast injuries to the hand treated between 1978 and 2006. Medical records, X-rays, and photos were reviewed to compile standard patient demographics and characterize the injury pattern. Explosives were classified based on their rate of decomposition. Reconstructive solutions were reviewed and characterized based on whether damaged tissues were repaired or replaced. Sixty-two patients were identified with blast injuries to their hand. Patients were predominantly male (92%) with an average age of 27 years. Firecrackers were the most commonly encountered explosives. Thirty-seven patients were identified as holding a low explosive in their dominant hand and were used for characterization of the injury pattern. The apparent pattern of injury was hyperextension and hyperabduction of the hand and digits. Common injuries were metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joint hyperextension with associated soft tissue avulsion, hyperabduction at the web spaces with associated palmar soft tissue tears, and finger disarticulation amputations worse at radial digits. Given the mechanisms of injury with tissue loss, surgical intervention generally involved tissue replacement rather than tissue repair. Blast injuries to the hand represent a broad spectrum of injuries that are associated with the magnitude of explosion and probably, the proximity to the hand. We were able to identify a repetitive pattern of injury and demonstrate the predominant use for delayed tissue replacement rather than microsurgical repair at the acute setting.

Keywords: Blast hand injuries, Injury pattern, Hand reconstruction, Mutilating hand injuries, Explosives

Introduction

Blast hand injuries, primarily seen during wartime [7, 9], are now frequently encountered in major civilian trauma centers [11]. Injuries range from minor lacerations to devastating crush avulsions requiring staged reconstructive procedures. Knowledge of the injury pattern and understanding of the destructive nature of these explosions can assist clinicians in designing a better reconstructive plan. The purpose of this study is to identify the individual injuries associated with an explosive blast to the hand and determine if there is a common pattern of injury following the explosion. A survey of our microsurgical procedures is used to demonstrate patterns in our reconstructive approach.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed all the blast hand injuries that were transferred to our clinic in San Francisco from 1978 to 2006. Medical notes, X-rays, and preoperative photographs were used to compile standard patient demographics, frequency of complex microsurgical procedures, and trends in the reconstructive approach to blast injuries. With the aid of our institution search engine, we used the keywords blast, explosion, and explosive, to identify all 62 patients with blast-related injuries to the hand. Inclusion criteria consisted of all patients sustaining an injury from an explosive and requiring an operative procedure. When preoperative photos were not available, detailed operative records were used to diagrammatically reconstruct the wounded hand and enumerate the injuries. Sixty-two patients were identified, of which, 37 had a common mechanism of injury where the patient was holding an explosive in the palm of the dominant hand. These cases were used for analysis of the injury pattern in order to identify the pathomechanics of the injury.

Commercially available explosives were classified as either low or high based on their rate of decomposition. Low explosives deflagrate at rates of up to 400 m/s, while high explosives detonate at rates of 1,000 to 9,000 m/s [16]. Other forms of explosives included mechanical detonators, industrial explosives, and homemade explosives.

Results

Of the 62 patients, 92% were male with an average of 27 years age (range 12–64). Most cases (89%) resulted in injury to the dominant hand, while eight patients (13%) presented with bilateral hand injuries. Nineteen patients (31%) presented with associated injuries. These include soft tissue loss of the lower extremities (14.5%), the face (9.7%), the torso (6.4%), and the arm and forearm (8.0%). Hearing loss and visual deficits were noted in 6.4% and 8.0% of the patients, respectively.

There were more than three times as many injuries from low explosives than from high explosives (Table 1). Some of the more frequently used explosives include firecrackers, pipe bombs, and dynamites. In a significant number of cases, homemade firecrackers and other devices were the cause of explosion.

Table 1.

Classification of explosives as the cause of blast for the 62 patients.

| Explosive | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Low explosive | |

| Firecracker | 18 |

| Pipe bomb | 5 |

| Gunshot | 5 |

| Black powder | 3 |

| Rocket explosive device | 2 |

| High explosive | |

| Dynamite | 5 |

| Bomb | 2 |

| Grenade | 1 |

| Lead azide | 1 |

| Mechanical detonator | 3 |

| Miscellaneous | 10 |

| Unknown | 7 |

| Total | 62 |

A review of the overall finger involvement indicates a radial to ulnar trend with the thumb being the most frequently injured digit (Fig. 1). The distribution of lacerations in the palm and digits indicates a predominance of injuries to the radial fingers and mid-palm. Significant tissue destruction was noted primarily at the first web space and mid-palm region.

Figure 1.

Percentage of injuries in the fingers, mid-palm, first web space, thenar eminence, and hypothenar eminence (n = 62).

The frequency amputations and near-complete amputations at various levels is detailed in Fig. 2. Amputations of the thumb and digits were predominantly at the periarticular surface. Most blast amputations occurred at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and interphalangeal (IP) joints. Fractures of the metacarpal bones, carpometacarpal disarticulations, and avulsions of the hand at the wrist were less common.

Figure 2.

Distribution of amputations, near-complete amputations, joint disarticulations, and fractures. IP Interphalangeal, DIP distal interphalangeal, PIP proximal interphalangeal, MCP metacarpophalangeal, MC metacarpal, CMC carpometacarpal (n = 62).

A common mechanism of injury was identified in 37 cases. It involves a young man holding or in the process of throwing a low explosive in his dominant hand. The apparent pattern was hyperextension and hyperabduction of the hand and digits. The joint hyperextension was associated with soft tissue avulsion and finger disarticulation amputations worse at the radial digits. The hyperabduction at the web spaces was associated palmar soft tissue tears.

Injuries were usually treated with replacement rather than tissue repair. A total of 45 microsurgical procedures were performed; however, only five of them were carried out at the acute setting. Delayed reconstruction involved replacement of amputated digits and soft tissue coverage (Fig. 3). Restoration of function was attempted with toe-to-hand procedures and first web space deepening (Fig. 4). In one case, metacarpal reconstruction of the thumb was accomplished with a fibular osteocutaneous flap. A variety of flaps were used for soft tissue coverage, first web deepening, or resurfacing of exposed structures in combination with finger reconstruction.

Figure 3.

Microsurgical reconstructive procedures following a blast hand injury (n = 62).

Figure 4.

Flaps used for soft tissue reconstruction and first web space release (n = 62).

Discussion

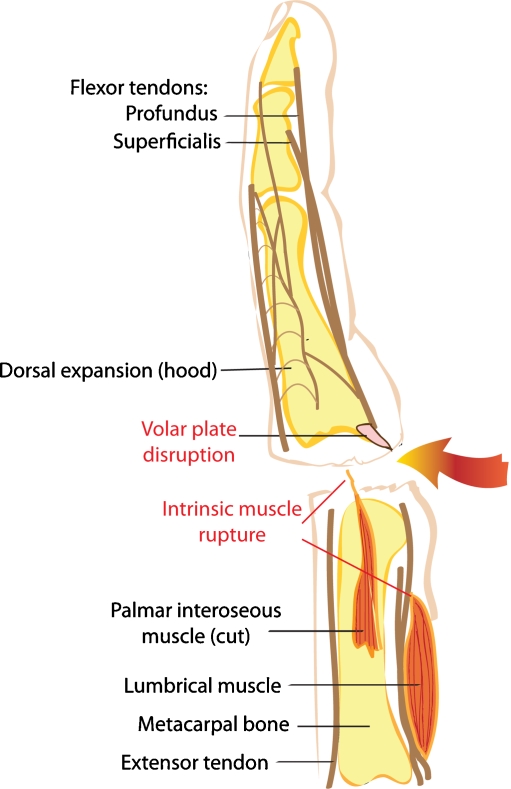

Several classifications of mutilating hand injuries exist in the literature [13, 18, 19]; however, the complex mechanism of a hand blast injury has not been addressed. We identified a recurring pattern of palmar hyperextension, thumb and fingers hyperabduction, IP and MCP hyperextension, and dorsal dislocation. The impact of a forceful blast and hyperextension of the digits cause a disruption of the volar plates and disinsertion of the intrinsic muscles (Fig. 5). Subsequently, patients sustain significant palmar tissue destruction (Fig. 6), digit amputations at the MCP or IP levels with degloving of proximal residual bone, and disruption of the web spaces, particularly the first web (Fig. 7).

Figure 5.

Pathomechanics of a blast injury while exerting a hyperextensive force at the articular level. The figure demonstrates joint disarticulation, volar plate disruption, and intrinsic muscle rupture.

Figure 6.

A 33-year-old right-hand-dominant man with a right-hand blast injury from an M-1000 firecracker explosion. The wound demonstrates a significant thenar eminence avulsion with degloving injuries of the thumb and long finger. The pattern is consistent with the predominantly radial distribution of injuries in the hand.

Figure 7.

A 15-year-old right-hand-dominant man with a right hand blast injury following a firecracker explosion (unspecified). Tissue avulsion at the first web space and hypothenar eminence with exposure of the flexor pollicis longus and multiple palmar lacerations. The pattern is consistent with hyperabduction and hyperextension of the thumb and widening of the first web space.

Analysis of our patient demographics reveals a profile of a young man holding an explosive in his dominant hand at the time of explosion. Blast injuries are usually due to firecrackers or homemade devices. The impact of the blast is most noticeable in the radial aspect of the hand as evident in the number of injuries involving the thumb, index finger, thenar eminence, first web space, and mid-palm. The magnitude of the explosion and the proximity to the hand are probably associated with these findings. Patients holding or in the process of throwing a firecracker sustained palmar and radial injuries of the thumb, index, and first web space. We hypothesize that when a firecracker or a pipe bomb is gripped in a closed fist, the wick and the detonator are in close proximity to the palmar and radial aspects of the hand. In an attempt to classify the level of destruction, we categorized injuries that were amendable to simple primary closure as lacerations. Larger wounds repaired with skin grafting or by secondary healing were labeled as deep abrasions. Any region of the palm reconstructed with a free tissue transplant was classified as a tissue avulsion. Although a broad spectrum of injuries exists between simple lacerations and deep avulsions, we regard the aforementioned classification as a clinically relevant method of organizing the various injuries to the palm (Fig. 1).

Once the immediate life-threatening conditions have been treated and the injured extremity has been stabilized, a plan for reconstruction of bone and soft tissue is formulated [4]. Although revascularization of ischemic tissues and replantation of amputated parts are time-honored procedures [3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15], repair at the acute setting after an explosion has been limited because of the destructive forces exerted during the blast. Completion amputations, delayed primary closure, and local wound care are the mainstay of initial treatment when revascularization is not a viable option [11]. During the early phase, debridement and skeletal fixation are essential components in preparation for major reconstructive procedures. Logan et al. [11] described a sequence of management which dovetails our approach to blast hand injuries. It includes an initial, reparative, reconstructive, and rehabilitative phase. In their series of 27 patients, revascularizations were only performed in two cases. Three toe-to-hand transfers and three free flap transplantations were performed during the delayed reconstructive phase.

In our series, the attempt to restore function was also primarily done with toe transplantation. In order to regain prehension for proper grip and grasp [14], our preferred method has been great-toe-to-thumb transplantation [17]. Fingers restored with second toe-to-hand transfer [5] have shown to be a reliable technique as well. In one case, a double second toe transplant was successfully achieved. In four other cases, a combined great-toe and second-toe transfer to the injured hand was performed. Although not covered in the scope of this survey, a thorough study of global function following reconstruction and the chance of returning to work after a mutilating blast injury is needed.

For soft tissue coverage, an array of flaps was used for resurfacing upper extremity wounds. The zone of injury, contour, and surface area guided our choice of flaps. The rectus abdominis muscle flap served as the workhorse for a wide range of defects. These included management of the mid-palm injuries, coverage of thenar and hypothenar avulsions, and widening of the first web space. The presence of an adequate first web space is essential for thumb prehensile hand function [1]. After a blast hand injury, the wide zone of injury excludes the use of local flaps previously described [2, 20]. Results from our survey revealed a recent trend of increased use of the lateral arm flap when compared to the rectus abdominis and serratus anterior muscle flaps. The rectus abdominis muscle was initially the workhorse flap for reconstruction of the first web in our clinic. The lateral arm flap has replaced the rectus as a thin and pliable fasciocutaneous flap, which makes it an excellent choice for deepening of the first web after a blast injury.

The limitations of this study are inherent in its nature as a retrospective survey of injury patterns and reconstructive trends. In order to determine the value of late microvascular reconstruction following a blast injury and its functional outcome, additional work is needed.

Conclusion

Blast hand injuries represent a wide spectrum of wounds associated with a distinct pattern. It is characterized by hyperextension and hyperabduction injuries, ranging from lacerations to complete amputation. In the acute phase, complex mutilating injuries cause substantial tissue destruction that requires completion amputation and soft tissue reconstruction rather than replantation or revascularization. Restoration of function is attempted with toe-to-hand procedures. First web contractures are treated with release and soft tissue replacement. In order to determine the functional outcome of blast hand injuries following microsurgical reconstruction, further investigation is required.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the California Society of Plastic Surgeon 57th Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, May 25, 2007.

Financial Disclosure

None of the authors have any commercial association or financial disclosure that pose or create a conflict of interest with information presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Adani R, Tarallo L, Marcoccio I, Fregni U. First web-space reconstruction by the anterolateral thigh flap. J Hand Surg (Am). 2006;31:640. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Akyurek M, Safak T, Kecik A. Coverage of thumb wound and correction of first webspace contracture using a longitudinally split reverse radial forearm flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Biemer E. Replantation of fingers and limb parts(:) technique and results. Chirurg. 1977;48:353. [PubMed]

- 4.Bumbasirevic M, Lesic A, Mitkovic M, Bumbasirevic V. Treatment of blast injuries of the extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(Suppl):S77. [PubMed]

- 5.Buncke HJ. Digital reconstruction by second-toe transplantation. In: Buncke HJ, editor. Microsurgery: transplantation–replantation. An atlas text. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1991. p. 61–101.

- 6.Buncke HJ. Microsurgery: transplantation–replantation. An atlas text. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1991.

- 7.Burkhalter WE, Butler B, Matz W, Omer G. Experience with delayed primary closure of war wounds of the hands in Vietnam. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1968;50:945. [PubMed]

- 8.Kleinert HE, Juhala CA, Tsai TM, Van Beek A. Digital replantation: selection, technique, and results. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:309. [PubMed]

- 9.Labaley ME, Peterson HD. Early treatment of war wounds of the hand and forearm in Vietnam. Ann Surg. 1973;177:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lendvay PG. Replacement of the amputated digit. Br J Plast Surg. 1973;26:398. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Logan SE, Bunkis J, Walton RL. Optimum management of hand blast injuries. Int Surg. 1990;75:109. [PubMed]

- 12.Patradul A, Ngarmuukos C, Parkpian V. Distal digital replantation and revascularivations(.) 237 digits in 192 patients. J Hand Surg (Br). 1998;23:578. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Reid DAC, Tubiana R. Mutilating injuries of the hand. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1984.

- 14.Tubiana R. Prehension in the mutilated hand. In: Reid DAC, Tubiana R, editors. Mutilating injuries of the hand. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1984.

- 15.Urbaniak JR. To replant or not to replant? That is not the question [editorial]. J Hand Surg (Am). 1983;8:507. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.US Naval Academy. Military explosives. In: Fundamentals of naval weapons systems. Federation of American Scientists website. Available at: http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/navy/docs/fun/part12.htm. Accessed February 11, 2008.

- 17.Wei FC. Toe to hand transplantation. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Peterson WC, Wolfe SW, editors. Green’s operative hand surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 1835–63.

- 18.Wei FC, El-Gammal TA, Lin CH, et al. Metacarpal hand: classification and guidelines for microsurgical reconstruction with toe transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Weinzweig J, Weinzweig N. The “Tic-Tac-Toe” classification system for mutilating injuries of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:1200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Zancolli EA, Angrigiani C. Posterior interosseous island forearm flap. J Hand Surg (Br). 1988;13:130. [DOI] [PubMed]