Abstract

This study investigated whether body mass index (BMI) was associated with effectiveness of carpal tunnel release as measured by physical and self-assessment tests. This prospective, longitudinal study was conducted from March 2001 to March 2003 using 598 cases (hands) diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome and scheduled for surgery at The Curtis National Hand Center, Baltimore, Maryland, and at the Pulvertaft Hand Centre, Derby, England. Body mass index was calculated, and demographic, clinical, and functional data were collected preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up. Grip, pinch, and Semmes–Weinstein scores were measured preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up. Levine–Katz self-assessment scores for symptom severity and functional status were measured preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up. Grip and pinch increased, whereas Semmes–Weinstein, symptom severity, and functional scores decreased by 6-month follow-up. Cases with BMI >35 had lower grip strength and higher symptom severity in males and higher functional status in both sexes pre- and postoperatively compared to normal-weight BMI cases. BMI had no relationship to patient satisfaction. Although morbidly obese cases did worse on some physical and self-assessment tests compared to normal BMI cases preoperatively, all improved to the same extent postoperatively regardless of BMI.

Keywords: Body mass index, Carpal tunnel syndrome

Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a symptom complex involving numbness in the median nerve distribution (thumb, index finger, and middle finger) as a result of compression of the median nerve under the flexor retinaculum at the wrist. The syndrome affects an estimated 2.7% of the population [2, 3, 7, 8, 13]. Overall prevalence of CTS in the United States may affect as many as 1.9 million people and may account for 500,000 surgical procedures annually, with costs over $2 billion [12]. The syndrome accounts for 3% of all workers’ compensation claims and can cost $38,000 per case in disability benefits [15]. The prevalence of CTS in the United Kingdom is thought to be 70 to 160 cases per thousand [4].

Carpal tunnel syndrome has a multifactorial etiology involving systemic, anatomic, idiopathic, and ergonomic factors. It is associated with both occupational and nonoccupational risk factors such as age, sex, obesity, diabetes, thyroid conditions, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, smoking, late pregnancy, and rapid weight loss [3, 7, 8, 13, 14, 16]. Carpal tunnel syndrome has been associated with increased body mass index (BMI) [16], a common measure expressing the relationship of weight to height, which is more highly correlated with body fat than any other indicator of height and weight.

Our objective was to determine the success of carpal tunnel release as measured by physical findings (Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s sign, Semmes–Weinstein, grip and pinch strength), as well as subjective patient evaluation of symptoms and functional limitations using the Levine–Katz questionnaire. We examined prospectively the relationship between five demographic characteristics of CTS patients in each BMI category. We also determined distribution of weight in the study population, in terms of normal, overweight, obese, and morbidly obese BMI, and compared this prevalence to the general population.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Review Board in Baltimore and the local ethics committee in Derby reviewed and approved the protocol of this study, and informed consent was obtained. Between March 2001 and March 2003, 803 cases were enrolled. At the time of analysis (11/04), 598 cases had completed their 6-month follow-up. Eleven hand surgeons evaluated and performed surgery on 343 hands in 261 patients at The Curtis National Hand Center. Four hand surgeons performed 255 procedures on 201 patients at the Pulvertaft Hand Centre.

Disease Criteria

Diagnosis of CTS was based on clinical history and symptoms suggestive of CTS and electrophysiological evidence of reduction of distal conduction velocity of the median nerve. At both hand centers, diagnosis of CTS was based on clinical criteria supplemented, if necessary, by electrophysiological tests if the diagnosis remained in doubt. The diagnostic criteria used included history and physical examination findings.

Patients eligible for this study met the following inclusion criteria: they had a clinical diagnosis of CTS, were between 20 and 90 years, were scheduled for surgery at our institutions, were English speaking, were willing to return for postoperative evaluation, and were able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were prior carpal tunnel surgery in the same hand, pregnancy, current renal dialysis, acute peripheral neuropathy due to lead exposure, or a terminal medical condition.

A preoperative assessment and history was administered to all participants. Personal history including age, gender, handedness, race, education, occupation and employment status, symptoms (onset, duration, and quality), prior treatment, and medical history (diabetes, thyroid, hypertension, and depression) was recorded. The physical examination included Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s test at 1 min, grip strength (kilograms), and pinch strength (kilograms). Semmes–Weinstein monofilament testing was done based on the following five levels: normal (1.65–2.83), diminished light touch (3.22–3.61), diminished protective sensation (3.84–4.31), loss of protective sensation (4.56–6.45), and deep pressure sensation (6.46–6.65). Weight, in pounds, and height, in inches, were recorded, and BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Normal BMI was defined as <25; overweight, 25 to 30; obese, 30 to 35; and morbidly obese, >35. The Levine–Katz self-administered questionnaire on severity, symptoms, and functional status of CTS was administered at the preoperative assessment and at the 6-month follow-up to evaluate symptoms and function. It provides a severity score based on 11 questions about CTS symptoms and a functional score based on the level of difficulty the patients experience performing eight activities of daily living. The scores are based on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 is the worst score and 1 is the best. This questionnaire has been found to be highly consistent and valid [1, 9].

Postoperative progress was recorded at the 6-month follow-up assessment. We chose a 6-month follow-up because a previous study at The Curtis National Hand Center reported improvement in symptom severity, and functional status made by the 6-month follow-up did not improve at the 12-month follow-up [5]. Responses to questions of satisfaction after surgery, complications of surgery, and return to work were collected. A physical examination was performed, including Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s test, grip strength, pinch strength, and Semmes–Weinstein testing. Patients were asked to complete a Levine–Katz questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data (e.g., Tinel’s sign and Phalen’s test) were analyzed by chi-square analysis. Because four BMI categories were used, the chi-square test was used for the overall study, and if found to be significant (p < 0.05), individual comparisons between pairs of age groups were made for detailed analyses. If expected cells in this analysis had fewer than five observations, a Fisher’s exact test was used. Continuous data (e.g., grip strength and pinch strength) were calculated by two-factor analysis of variance with BMI group and time (i.e., presurgery vs. postsurgery) as the factors with BMI by time interactions included in the analysis. Separate calculations were made by ANOVA to determine if there were gender differences. Calculations were done using SPSS and Statgraphics statistical programs.

Results

Demography

The demographic distribution of our cases is presented in Table 1. Average patient age was 55.5 years with a range of 20 to 90 years. There was a small but significant (p = 0.02) difference in age among BMI groups. Of the cases, 57.4% of them were from the United States and 42.6% were from the United Kingdom, with no significant difference in the distribution among BMI groups. Primary race was white (93%). There were more females (71.1%) than males (28.9%) although the proportion of males was lower and was significantly different among BMI groups (p = 0.002). Fifty-five percent of the cases represented the dominant hand and did not vary significantly among the BMI groups.

Table 1.

Demography by BMI category.

| BMI category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25–30 | >30–35 | >35 | Total | p | |

| Demography (n) | 112 | 200 | 153 | 133 | 598 | |

| Males (%) | 22.3 | 33.5 | 36.6 | 18.8 | 28.9 | 0.002 |

| White (%) | 6.2 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 12.0 | 7.0 | 0.01 |

| United States site (%) | 59.8 | 56.0 | 53.6 | 61.7 | 57.4 | 0.51 |

| Age (years) | 55.9 | 57.4 | 55.6 | 52.5 | 55.5 | 0.02 |

| Insurance | 22.8 | 25.0 | 30.0 | 22.7 | 25.6 | 0.39 |

| College | 41.1 | 43.0 | 35.3 | 36.1 | 39.1 | 0.41 |

| Manual labor (%) | 35.7 | 36.0 | 49.3 | 44.2 | 41.2 | 0.05 |

| Both hands | 39.3 | 48.5 | 43.8 | 48.1 | 45.5 | 0.39 |

| Dominant hand | 53.2 | 57.0 | 52.3 | 57.3 | 55.2 | 0.75 |

Medical History

The symptoms reported were numbness (95.0%), pain (75.6%), and loss of function (30.3%). These were not significantly different among BMI groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medical history by BMI category.

| BMI category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25–30 | >30–35 | >35 | Total | p | ||

| Medical symptoms | Pain symptoms | 69.6 | 80.0 | 73.9 | 76.1 | 75.6 | 0.21 |

| Numbness symptoms | 97.3 | 94.5 | 94.7 | 93.9 | 95.0 | 0.62 | |

| Loss of hand function | 29.5 | 31.5 | 26.1 | 33.8 | 30.3 | 0.53 | |

| Comorbidity | Wrist trauma | 6.3 | 4.0 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 0.69 |

| Neck trauma | 6.5 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 0.96 | |

| Wrist arthritis | 22.3 | 18.1 | 24.2 | 9.0 | 18.4 | 0.006 | |

| Neck arthritis | 9.8 | 13.1 | 16.3 | 9.8 | 12.6 | 0.29 | |

| Depression | 13.5 | 15.6 | 22.4 | 14.3 | 16.6 | 0.17 | |

| Diabetes | 3.6 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 18.8 | 9.7 | 0.001 | |

| Thyroid | 16.9 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 10.6 | 0.11 | |

| Hypertension | 16.2 | 27.1 | 42.5 | 42.9 | 32.6 | <0.001 | |

| Gout | 0.0 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 0.004 | |

| Complications | Any complications | 28.5 | 19.5 | 19.6 | 26.3 | 22.7 | 0.02 |

| Superficial infection | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.36 | |

| Sensitive scar | 8.0 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 0.71 | |

| Pillar pain | 7.1 | 6.0 | 3.9 | 8.3 | 6.2 | 0.46 | |

| Sympathetic dystrophy | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.55 | |

| Nerve symptoms | 4.5 | 6.5 | 0.7 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 0.06 | |

| Other complications | 12.5 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 0.73 | |

Data are expressed as percent of cases within each BMI group.

Wrist and neck traumas were reported in 4.9 and 5.5% of the cases, respectively, and were not significantly different among BMI groups. Wrist and neck arthritides were present in 18.4 and 12.6% of the cases, respectively. Prevalence of diabetes was 9.7%, and prevalence of hypertension was 32.6%. Both demonstrated a higher prevalence in the higher BMI groups (p < 0.001), with 18.8% having diabetes and 42.9% having hypertension in the >35 BMI group. Depression was present in 16.6% of cases and did not differ among BMI groups. Thyroid disease was present in 10.6% and gout in 4.4% of cases. Because diabetes, hypertension, and wrist arthritis were present in substantial numbers and were significantly different among the BMI groups, these variables were treated as covariates in subsequent ANOVA analysis for outcomes.

Preoperative and 6-Month Follow-up Outcome Measurements

The presence of diabetes and hypertension was found to be significantly different among BMI groups and was thought to possibly influence results. Therefore, these variables were treated as covariates in the statistical computations. Probabilities presented are the adjusted values.

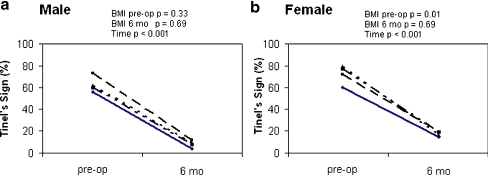

Before surgery, 65.1% of all cases reported a Tinel’s sign. This decreased to 34.9% at 6-month follow-up (p = 0.001). In females, there was a lower prevalence of Tinel’s sign preoperatively in the normal BMI category (58.6%) compared to the higher BMI categories (71.4% in overweight, p = 0.05; 79.2% in obese, p = 0.003; and 76.9% in morbidly obese, p = 0.006) (Fig. 1b). At 6-month follow-up, the prevalence decreased overall to 12.6% with no difference among the BMI groups. Although the lowest prevalence of Tinel’s sign in males was in the normal BMI group, it was not significantly different from the other BMI groups (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Tinel’s sign preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from chi-square analysis for BMI effects preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up and for time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as indicated.

Phalen’s sign was present in 83.7% of male cases before surgery and decreased to 5.6% at 6-month follow-up (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). In females, the prevalence was 91.3% before surgery and 13.1% after surgery (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2b). There was no difference in Phalen’s sign among BMI groups.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Phalen’s sign preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from chi-square analysis for BMI effects preoperatively and at 6-month follow-up and for time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as indicated.

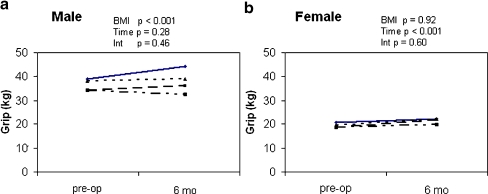

Grip strength was higher in males than in females (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). In males, overall grip strength in the normal BMI group was 41.6 ± 1.8 kg (mean ± SEM; p < 0.001) compared to BMI >35, which was 32.9 ± 1.8 kg (p < 0.001). The absolute change in grip strength was not significantly different between the BMI groups. BMI was not related to overall grip strength or changes from baseline in females (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Preoperative and 6-month follow-up grip strength for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from two-factor ANOVA with BMI categories and time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as main effects and BMI × time interactions (Int).

Pinch strength was higher in males than in females (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in pinch strength between the normal BMI group or any group with BMI >25. There was, however, a difference between BMI 25–30 (overweight) compared to BMI >30–35 (obese). There was no significant difference in the change in pinch strength from baseline among the BMI groups.

Figure 4.

Preoperative and 6-month follow-up pinch strength for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from two-factor ANOVA with BMI categories and time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as main effects and BMI × time interactions (Int).

There was an overall improvement (decrease) in the Semmes–Weinstein score from 2.52 ± 0.06 points preoperatively to 2.11 ± 0.06 points at 6 months in males and from 2.24 ± 0.03 to 1.70 ± 0.03 points in females (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5a). Males had significantly higher scores than females (p < 0.001). BMI was not related to Semmes–Weinstein scores or change in scores in either gender.

Figure 5.

Preoperative and 6-month follow-up Semmes–Weinstein scores for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from two-factor ANOVA with BMI categories and time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as main effects and BMI × time interactions (Int).

For all cases, 90% reported that they were satisfied with the surgery at 6-month follow-up. There was no significant difference between genders or among BMI groups (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Satisfaction for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group.

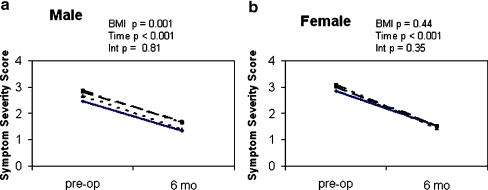

As measured by the Levine–Katz self-administered questionnaire, symptom severity scores improved (decreased) significantly from 2.7 ± 0.1 to 1.4 ± 0.1 in males and from 3.0 ± 0.1 to 1.5 ± 0.1 in females at 6-month follow-up (p < 0.001) (Fig. 7). Overall, males reported lower symptom severity scores than females (p = 0.001). In males, there were significantly lower symptom severity scores in the normal BMI group compared to the 25–30 BMI and the >35 BMI groups (p < 0.001) but not the 30–35 BMI group. There was no difference in the change in scores over the 6 months among the BMI groups. There was no difference among BMI groups in females regarding symptom severity scores or change in scores.

Figure 7.

Preoperative and 6-month follow-up symptom severity scores for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from two-factor ANOVA with BMI categories and time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as main effects and BMI × time interactions (Int).

Functional status scores improved from 2.2 ± 0.1 to 1.4 ± 0.1 in males and from 2.5 ± 0.1 to 1.6 ± 0.1 in females (p < 0.001) (Fig. 8), with the scores in males being significantly lower than females (p < 0.001). For both males and females, the groups with normal BMI had the lowest functional status scores and were significantly lower (p < 0.001) than the morbidly obese scores. There was no significant difference in the change in scores from preoperative to 6-month follow-up among the BMI groups for either gender.

Figure 8.

Preoperative and 6-month follow-up functional status scores for males (a) and females (b) in each BMI group. –––––– <25 BMI, – – – – – – 25–30 BMI, ——– >30–35 BMI, and –– – –– – –– >35 BMI. p values are from two-factor ANOVA with BMI categories and time (preoperative vs. 6 months) as main effects and BMI × time interactions (Int).

Complications

Table 2 lists the complication rates by BMI groups. Twenty-three percent of the cases reported one or more complications. There was no difference among the BMI groups regarding total or specific complications.

Discussion

The World Health Organization considers obesity, defined as a BMI of more than 30, to be a global epidemic, with 7% of the adult population worldwide and 1.2 billion people now categorized as overweight and 300 million as obese [17]. The 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, using measured heights and weights, indicates that an estimated 65% of U.S. adults are either overweight or obese, with 31% considered obese [11]. The 2002 Health Survey for England reports that 61% of U.K. adults are overweight or obese [6]. The sample of carpal tunnel cases reporting for surgery in this study has a prevalence of overweight or obese of 81%. If this is reflective of carpal tunnel patients as a whole, it would suggest that obesity may be a risk factor in the disorder. Thirty-three percent of our study patients were overweight, 25% were obese, and 22% were morbidly obese. The incidence of comorbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension, was significantly higher in obese and morbidly obese groups than in normal or overweight groups although the overweight group still had significant amounts of diabetes and hypertension.

In our study, the results of the functional status Levine–Katz questionnaires show significantly lower overall scores in the normal BMI groups than in the morbidly obese group in both males and females. Symptom severity was lower in normal-weight males than in morbidly obese males, but there was no difference in symptom severity in females. There was no difference in the absolute change in scores for either males or females. Thus, although the amount of improvement was the same in all BMI groups, where the morbidly obese groups started with a higher score, the 6-month follow-up score ended higher.

Obesity has been implicated as a contributory factor in many medical conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid conditions, and connective tissue disorders. Carpal tunnel syndrome is an obesity-associated morbidity that has been correlated to increases in weight and BMI [3, 7, 13, 16]. Although our study was not designed to determine the prevalence of obesity in carpal tunnel patients, our data indicated that 81% of our patients were either overweight or obese compared to 65% of the U.S. population and 61% of the U.K. population. In this sense, our data support the findings of those other authors such as Nathan et al. [10], who find obesity a risk factor for CTS.

Even though obesity is a significant factor in CTS, does it affect the outcome of surgery? The data in this study show that overweight and obese patients did show improvement after carpal tunnel surgery and improved self-assessment scores for symptom and function as measured by the Levine–Katz questionnaire. Our results also reported improvement in the diminution of the number of patients with positive Tinel’s sign and positive Phalen’s test. However, morbidly obese patients did not score as well as normal BMI patients in the Levine–Katz symptom severity score and functional status score both before and after surgery.

In conclusion, all patients improved to the same extent after carpal tunnel surgery regardless of BMI although males with BMI >35 (morbidly obese) began and ended with lower grip strength and higher symptom severity scores. Both males and females who were morbidly obese had higher overall functional status scores.

Acknowledgments

This study received research support from the Southern Derbyshire Acute Hospitals National Health Trust Matching Grant Research Scheme and the Derby Hand Surgery Trust Funds. The investigators thank the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand, the Raymond M. Curtis Research Foundation, and the Medstar Research Institute for the financial support of this study.

References

- 1.Amadio PC, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Jensen LM. Outcome assessment for carpal tunnel surgery: the relative responsiveness of generic, arthritis-specific, disease-specific, and physical examination measures. J Hand Surg 1996;21A:338–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Ornstein E, Ranstam J, Rosen I. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA 1999;282:153–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Becker J, Nora DB, Gomes I, Stringari FF, Seitensus R, Panosso JS, et al. An evaluation of gender, obesity, age and diabetes mellitus as risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 2002;113:1429–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bland JD, Rudolfer SM. Clinical surveillance of carpal tunnel syndrome in two areas of the United Kingdom, 1991–2001. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Guyette TM, Wilgis EFS. Timing of improvement after carpal tunnel release. J Surg Orthop Adv 2004;13:206–9. [PubMed]

- 6.Health Survey for England. Body mass index by sex, adults aged 16–64, 1986/87–2002, England. Available at http://www.heartstats.org. Accessed March 3, 2005. Health Survey for England 2005.

- 7.Karpitskaya Y, Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Prevalence of smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and thyroid disease in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. Ann Plast Surg 2002;48:269–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kouyoumdjian JA, Morita MD, Rocha PR, Miranda RC, Gouveia GM. Body mass index and carpal tunnel syndrome. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2000;58:252–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Levine DW, Simmons BP, Koris MJ, Daltroy LH, Hohl GG, Fossel AH, et al. A self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg 1993;75A:1585–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Nathan PA, Istvan JA, Meadows KD. A longitudinal study of predictors of research-defined carpal tunnel syndrome in industrial workers: findings at 17 years. J Hand Surg 2005;30B:593–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES 1999–2002 data files. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/product/pubs/pubd/hestats/obese/obse99.htm. Accessed March 3, 2005. National Center for Health Statistics 2004.

- 12.Palmer DH, Hanrahan LP. Social and economic costs of carpal tunnel surgery. Instr Course Lect 1995;44:167–72. [PubMed]

- 13.Sungpet A, Suphachatwong C, Kawinwonggowit V. The relationship between body mass index and the number of sides of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Med Assoc Thai 1999;82:182–5. [PubMed]

- 14.Tanaka S, Wild DK, Cameron LL, Freund E. Association of occupational and non-occupational risk factors with the prevalence of self-reported carpal tunnel syndrome in a national survey of the working population. Am J Ind Med 1997;32:550–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Diagnosis and treatment of worker-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2002;62:1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Werner RA, Albers JW, Franzblau A, Armstrong TJ. The relationship between body mass index and the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve 1994;17:632–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases—report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. World Health Organization 2003. [PubMed]