Abstract

Background

Impairment in maternal interpersonal function represents a risk factor for poor psychiatric outcomes among children of depressed mothers. However, the mechanisms by which this effect occurs have yet to be fully elucidated. Elevated levels of emotional or physiological reactivity to interpersonal stress may impact depressed mothers’ ability to effectively negotiate child-focused conflicts. This effect may become particularly pronounced when depressed mothers are parenting a psychiatrically ill child.

Methods

The current feasibility study evaluated mothers’ emotional and cardiovascular reactivity in response to an acute, child-focused stress task. Twenty-two depressed mothers of psychiatrically ill children were recruited from a larger clinical trial; half were randomly assigned to receive an adapted form of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-MOMS), while the other half received treatment as usual (TAU). For comparison purposes, a matched sample of 22 nondepressed mothers of psychiatrically healthy children was also evaluated.

Results

Depressed mothers receiving minimal-treatment TAU displayed the greatest increases in depressed mood, heart rate, and diastolic blood pressure in response to the child-focused stress task, and significantly differed from the relatively low levels of reactivity observed among nondepressed mothers of healthy children. In contrast, depressed mothers receiving IPT-MOMS displayed patterns of reactivity that fell between these extreme groups. Maternal stress reactivity was associated not only with maternal psychiatric symptoms, but also with levels of chronic parental stress and maternal history of childhood emotional abuse.

Conclusions

Future, more definitive research is needed to evaluate depressed mothers’ interpersonal stress reactivity, its amenability to treatment, and its long-term impact on child psychiatric outcomes.

Keywords: depression, stress, cardiovascular reactivity, emotional reactivity

INTRODUCTION

Maternal depression is a well-documented risk factor for child psychiatric disorder, with research suggesting that offspring of depressed parents are at 2- to 3-fold risk for both internalizing and externalizing disorders [1]. Conversely, recent data suggest that effective treatment of maternal depression is associated with improvement in child psychiatric disorders [2]. Although multiple factors may contribute to the negative outcomes observed in children of depressed mothers, [3] impairment in maternal interpersonal function has been consistently implicated in this process [4,5].

Being a mother is a demanding job that often requires managing stressful situations or conflicts with one’s children. Mothering when depressed poses additional interpersonal challenges [6,7], which are further compounded when both mother and child suffer from psychiatric problems. The frequency and intensity of child-focused interpersonal disputes may increase when parenting a psychiatrically ill child. Moreover, when mothers are depressed, their emotional and physiological responses to child-focused stressors may hinder their ability to effectively negotiate child-related conflicts.

Understanding how depressed mothers react to interpersonal conflicts with their psychiatrically ill children holds significance for both maternal and child psychiatric outcomes. Exaggerated or persistent dysphoria following child-focused conflicts may place mothers at risk for recurrence or worsening of syndromal depressive episodes. In addition, high levels of emotional or physiological reactivity to child-focused stressors may have an adverse impact on maternal parenting skills, such as problem-solving, positive communication, and limit-setting. Mothers who are highly reactive to child-focused disputes may respond to their children with elevated levels of negative affect, including criticism or hostility. Such aspects of maternal expressed emotion may, in turn, contribute to poor child psychiatric outcomes, thus perpetuating a cycle of increasing child psychiatric problems and worsening maternal depression.

The current pilot study was developed to evaluate the feasibility of measuring patterns of emotional and cardiovascular reactivity displayed by depressed mothers of psychiatrically ill children when faced with a child-focused interpersonal stressor. Specifically, we evaluated 22 depressed mothers recruited from pediatric mental health clinics as part of an ongoing treatment trial for depressed mothers of psychiatrically ill children (MH64518). Half of the depressed mothers had been assigned to receive treatment as usual (TAU), in which they were provided with a community-based mental health referral. The other half was randomized to receive IPT-MOMS, [8] a 9-session psychosocial intervention based on principles of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT [9,10]) and designed to meet the needs of depressed mothers caring for psychiatrically ill offspring. For comparison purposes, we also evaluated a matched sample of 22 nondepressed mothers whose children were not receiving psychiatric treatment.

A secondary goal of this pilot study was to compare patterns of emotional and physiological reactivity observed across these groups of mothers, in order to guide the development of future, more definitive studies in this area. In general, we expected that depressed mothers in the minimal-treatment TAU condition would display the greatest levels of reactivity to the child-focused stress task, particularly as compared with nondepressed mothers of psychiatrically healthy children. We also sought to explore the potential impact of an interpersonally focused depression treatment on maternal reactivity, by evaluating patterns of reactivity displayed by depressed mothers receiving active IPT-MOMS treatment. Finally, we sought to explore the extent to which maternal risk factors such as current psychiatric symptoms, perceived stress, adult attachment style, and history of childhood abuse were associated with mothers’ reactivity to the child-focused stress task.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Depressed mothers were recruited from a randomized clinical trial (MH64518) designed to compare treatment outcomes with IPT-MOMS versus a TAU control condition. This study has been described in detail elsewhere [11]. Depressed women entering the parent trial had been recruited from pediatric mental health clinics where their school-aged children were receiving psychiatric treatment. Nondepressed mothers were recruited via local advertisements. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants before study participation. All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Mothers were eligible for participation if they were aged 18–65 and the biological or adoptive mother and custodial parent of a child aged 6–18. Exclusion criteria included: not currently living with the child; serious risk for child abuse or neglect; substance abuse within the preceding 6 months; active suicidality; psychosis; diagnosis of borderline or antisocial personality disorder; and serious and/or unstable medical condition. Depressed mothers recruited into the parent trial met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder of at least moderate severity, as documented by DSM-IV diagnosis obtained via SCID interview (SCID-I [12]) and a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD [13]) score ≥ 15. Depressed mothers could not be receiving alternate forms of individual psychotherapy upon entry into the parent trial. However, depressed mothers on antidepressant medications were included if they met study entry criteria despite 8 weeks of treatment with a stable, therapeutic dose of antidepressant medication. Nondepressed mothers did not meet current or lifetime criteria for any mood disorder.

Procedures

Thirty-three depressed mothers who entered the parent trial between 03/10/04 and 04/18/06 were approached for participation in the current pilot. Of these, 26 were enrolled [reasons for non-enrollment: not interested (n = 2), interested but could not be contacted (n = 1), travel too difficult (n = 1), work conflict (n = 1)]. Of the 26 depressed mothers who enrolled, 22 completed reactivity assessments [reasons for noncompletion: early discontinuation from parent trial (n = 2), inability to schedule assessment (n = 1), and refusal to complete questionnaires (n = 1)]. Finally, 22 nondepressed mothers, matched to the depressed sample on age (within 4 years) and race were recruited to participate.

Participants completed two assessment sessions. For depressed mothers, assessment sessions were scheduled approximately one month after entry into the parent trial. [This assessment time point was selected to minimize the impact that pilot procedures may have on patient recruitment and engagement within the larger parent trial.] During the first session, participants completed self-report assessments of perceived life stress and early childhood trauma. Participants returned to the clinic one week later for completion of stress reactivity assessments. Participants were asked to abstain from smoking and caffeinated beverages for 1 h before participation in the reactivity session, which was scheduled in the late morning or early afternoon. For this session, mothers were situated in a comfortable chair within a private room of the research clinic. An occluding cuff was placed on the non-dominant arm for measurement of heart rate and blood pressure (Accutracker 2000). Following a 10-min habituation, mothers engaged in a 10-min resting baseline. Mothers then engaged in a 5-min “warm-up” speech, in which they were asked to speak freely about their child in an open-ended fashion, followed by a child-focused speech stress task. During the speech stress task, mothers were given 3 min to prepare a speech about a recent situation with their child that made them feel angry or stressed, and 4 min for video-taped speech delivery. Mothers were asked to discuss a series of points listed on a card during the speech stress (i.e., describe the situation, how you dealt with the situation, how you felt about the situation and the people involved, how well you think you handled the situation, etc). The speech stress was followed by a 20-min recovery period, in which participants relaxed without distraction. Following recovery, participants completed remaining self-reports, were debriefed, and dismissed.

Assessments

Physiological and emotional reactivity to the child-focused speech stress

Changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and self-reported mood states that occurred in response to the child-focused speech stress represented our primary study outcomes. Because variability among baseline scores is a problem when evaluating reactivity, we constructed residualized change scores using a simple linear regression model in which outcomes obtained during (or just after) the speech stress were predicted by resting baseline scores. The standardized residuals for each case were then saved from this model. In this way, change in response to the speech task was evaluated independent of (i.e., partialed from) individual differences in baseline scores.

To enhance measurement reliability, baseline blood pressure and heart rate values were calculated by averaging three assessments obtained at 90 s intervals during the final 5 min of the baseline period. Blood pressure and heart rate in response to the stress task were calculated by averaging two assessments obtained at 90 s intervals as mothers gave their child-focused speech.

Transient levels of depression and tension were assessed with brief self-report scales drawn from the Profile of Mood States (POMS [14,15]) completed following baseline assessment and again following the speech stress task. POMS-SF scales display good internal consistency (αs ranging from .87 to .91) and a close relationship to full POMS scales [16].

Psychosocial assessments

Depression and Anxiety:

Depression

The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI [17]) evaluated self-reported levels of affective, cognitive, and vegetative symptoms of depression as experienced by subjects over the past week.

Worry

The 16-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ [18]) assessed trait levels of worry, including the frequency, perceived controllability, and overwhelming nature of worrying as typically experienced by subjects. The PSWQ displays good internal consistency, and high PSWQ scores have been related to high levels of emotional reactivity in response to stress [18].

Perceived stress

The 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS [19]) evaluated subjects’ appraisal of their life as stressful over the past month. The PSS assesses perceptions of daily life as unpredictable, uncontrollable and overloading, and is well-validated within clinical and non-clinical samples.

Chronic parental stress

The 4-item Parental Stress subscale of the Chronic Stress Scale (CSS [20]) evaluated chronic stress related to parenting issues, as experienced over the past six months. CSS scores display good internal consistency (α = .83) and have been shown to mediate the long-term psychological effects of more acute life stressors [20].

Adult attachment

The 36-item Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR [21]) scale assessed levels of anxious (18 items) and avoidant (18 items) adult attachment dimensions. This self-report scale displays adequate validity as assessed with observer-based ratings of attachment-relevant behavioral and personality characteristics [22].

History of childhood abuse

A shortened form of the self-reported Early Trauma Inventory (ETI [23]) assessed women’s experience of physical and emotional abuse before age 18. The ETI Physical Abuse subscale included nine items, such as being disciplined by being slapped, punched, or kicked. The ETI Emotional Abuse subscale included seven items, such as often being put down, ridiculed, or yelled at by parents while growing up. Subjects were queried about the duration and frequency of endorsed items; this information was integrated to calculate a total severity score for each trauma domain [23].

Analysis Plan

ANOVAs were conducted to evaluate differences between the study groups in terms of residualized change scores for emotional (POMS depression and tension scores), heart rate, and blood pressure outcomes, with Tukey HSD tests run to examine specific group contrasts. Follow-up ANCOVAs were conducted to evaluate whether Group effects for cardiovascular outcomes remained following control for current smoking status and cardiovascular medication use. To explore psychosocial predictors of emotional and physiological reactivity to the child-focused stress task, Spearman ρcorrelation coefficients were used to evaluate the association of residualized reactivity scores with relevant psychological, stress-related, adult attachment, and childhood abuse history variables. Variables displaying a significant (P <.05) association were entered simultaneously into a multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis.

RESULTS

Participants

Mean age of participants was 44.18 years (SD = 7.73). Participants were mostly white (93.2%), married or living with a partner (72.7%), and well educated (average years of education = 15.25, SD = 2.54). Average number of children in the household was 2.5 (SD = 0.82). Most were nonsmokers (79.5%), and the average body mass index (BMI) was in the normal to overweight range (mean = 28.79, SD = 6.06). At time of reactivity assessment, only 3 of 12 mothers receiving TAU had pursued any community-based mental health treatment. In contrast, all mothers receiving IPT-MOMS were in active treatment, and had received an average of four individual therapy sessions.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the three study groups are provided in Table 1. The groups did not differ on age, race, BMI, education, marital/partner status, or number of children. The depressed IPT-MOMS mothers were more likely to be current smokers [χ2(2) = 12.44, P <.01] as compared with the other groups, and the depressed women displayed a nonsignificant trend toward a higher rate of cardiovascular medication use. As would be expected, the depressed groups were more likely to be taking antidepressant medications [χ2(2) = 11.32, P <.01], and displayed greater symptoms of depression, worry, and perceived stress as compared with the nondepressed mothers (Ps <.01). See Table 1. While the two depressed groups did not differ on depression scores at pretreatment assessment, there was a nonsignificant trend for mothers receiving IPT-MOMS to report lower levels of depression (BDI, P = .059) and worry (PSWQ, P = .056) at the time of the reactivity assessment, as compared with depressed mothers receiving TAU.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample

| Non-depressed (N = 22) |

Depressed IPT-MOMS (N = 10) |

Depressed TAU (N = 12) |

Test statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M (SD) | 44.30 (7.41) | 42.22 (7.82) | 45.58 (8.53) | F(2,41) = .51 |

| % Caucasian | N (%) | 21 (95.5%) | 9 (90%) | 11 (91.7%) | X2(2) = .382 |

| Education in yrs, M | M(SD) | 15.50 (2.44) | 14.40 (2.95) | 15.50 (2.43) | F(2,41) = .71 |

| Married or living with partner | N (%) | 19 (86%) | 6 (60%) | 7 (58%) | X2(2) = 4.13 |

| Number of children | M (SD) | 2.55 (.67) | 2.40 (1.17) | 2.50 (.80) | F(2,41) = .10 |

| Body mass index | M (SD) | 27.59 (5.85) | 28.35 (6.09) | 31.34 (6.16) | F(2,41) = 1.55 |

| Current smokers | N (%) | 2 (9.1%) | 6 (60%) | 1 (8.3%) | X2(2) = 12.44 ** |

| Antidepressants medication | N (%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (40%) | 5 (41.7%) | X2(2) = 11.32 ** |

| Taking cardiovascular medication | N (%) | 1 (4.5%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (25%) | X2(2) = 4.35 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | M (SD) | 2.05 (1.81) | 16.20 (5.47) | 21.17 (7.71) | F(2,41) = 67.41 ** |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) | M (SD) | 39.41 (10.60) | 51.38 (8.52) | 64.00 (13.09) | F(2,41) = 17.04 ** |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | M (SD) | 17.77 (5.34) | 33.20 (3.79) | 37.17 (5.65) | F(2,41) = 66.17 ** |

P <.05;

P <01.

Emotional Reactivity Outcomes

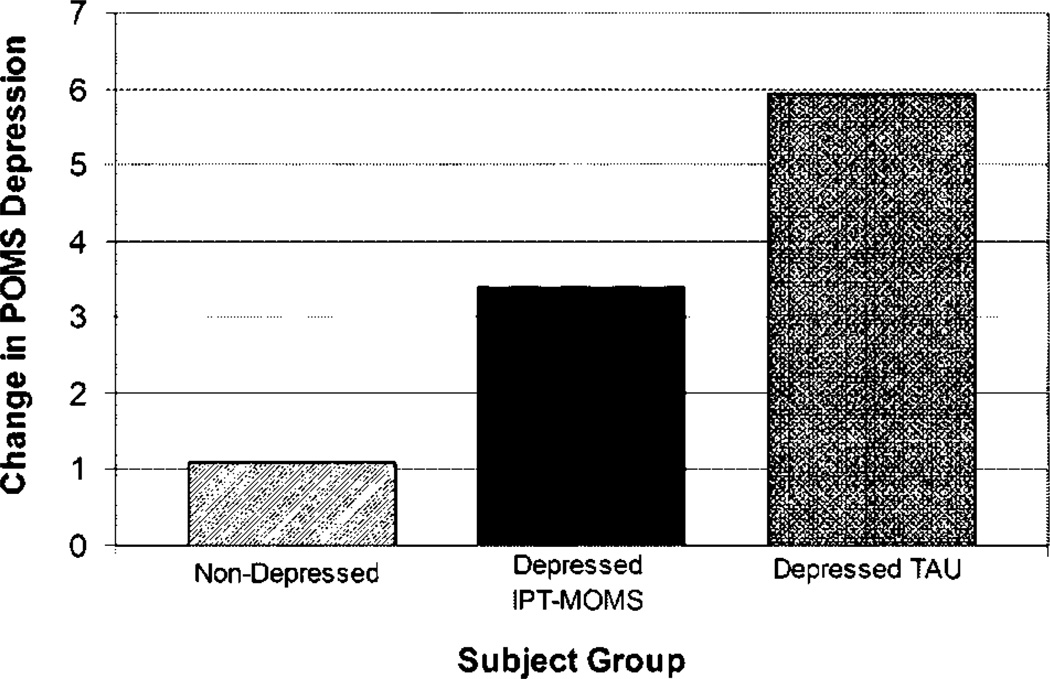

While the Group effect for reactivity on POMS depression scores did not reach statistical significance [F(2,41) = 3.02, P = .06], specific group contrasts indicated that the depressed mothers receiving TAU displayed significantly greater POMS depression reactivity to the interpersonal stress task as compared with nondepressed controls (P <.05). In contrast, the depressive reactivity of mothers receiving IPT-MOMS fell between the nondepressed and depressed TAU groups, but did not significantly differ from either of these two groups. See Figure 1. The groups did not differ in their reactivity with respect to POMS tension scores [F(2,41) = .12, P = .12].

Figure 1.

Raw score change in POMS depression scores from baseline to post-task assessment: depressive reactivity in response to the child-focused interpersonal stressor.

Secondary analyses indicated that women reporting greater levels of depression (BDI), perceived stress (PSS) and chronic parental stress (CSS—Parental), and women reporting a greater childhood history of emotional abuse (ETI—Emotional Abuse) displayed greater POMS depression reactivity to the child-focused stress task. See Table 2. When these variables were entered simultaneously into an MLR model, the resultant model accounted for 34% of the variance in emotional reactivity [F(4,39) = 6.46, P <.01, adjusted R2 = .337]. Within this model, only chronic parental stress (β = .66, P <.01) and childhood emotional abuse (β = .36, P <.01) remained significant following control for the other model variables.

TABLE 2.

Spearman correlations (P values) between self-reported psychosocial factors and mothers’ depression and heart rate reactivity (residualized change scores) to the child-focused interpersonal stress task (N = 44)

| POMS depression reactivity | Heart rate reactivity | |

|---|---|---|

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | .334 (.027) | .335 (.026) |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) | .224 (.170) | .471 (.002) |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | .393 (.008) | .362 (.016) |

| Chronic parental stress (CSS—parental) | .588 (.000) | .188 (.223) |

| Childhood physical abuse (ETI—physical abuse) | .287 (.059) | .152 (.323) |

| Childhood emotional abuse (ETI—emotional abuse) | .468 (.001) | .137 (.375) |

| Anxious attachment dimension (ECR—anxious) | .245 (.114) | .245 (.113) |

| Avoidant attachment dimension (ECR—avoidant) | .104 (.508) | .356 (.019) |

Physiological Reactivity Outcomes

ANOVA results indicated a significant effect of Group on heart rate reactivity in response to the interpersonal stress task [F(2,41) = 4.13, P <.05]. Similar to findings for depression reactivity, group contrasts indicated that the depressed mothers receiving TAU displayed significantly greater heart rate reactivity as compared with nondepressed controls (P <.05), while the depressed mothers receiving IPT-MOMS fell between these extreme groups. See Figure 2. Follow-up ANCOVA results indicated that the effect of Group on heart rate reactivity remained significant following control for smoking status and cardiovascular medication use [F(2,39) = 4.36, P <.05].

Figure 2.

Raw score change in heart rate from baseline to speech assessment: heart rate reactivity in response to the child-focused interpersonal stressor.

The groups did not significantly differ with respect to systolic blood pressure reactivity [F(2,41) = .29, ns]. However, the Group effect for diastolic blood pressure reactivity approached significance [F(2,41) = 3.10, P = .05], a result that was essentially unchanged in the ANCOVA model controlling for smoking status and cardiovascular medication use [F(2,39) = 3.10, P = .05]. See Figure 3. In this case, specific group contrasts indicated that the depressed TAU group displayed significantly greater diastolic blood pressure reactivity as compared with the IPT-MOMS group (P <.05).

Figure 3.

Raw score change in diastolic blood pressure from baseline to speech assessment: diastolic blood pressure reactivity in response to the child-focused interpersonal stressor.

Exploratory analyses evaluating correlates of heart rate reactivity indicated that greater levels of maternal depression (BDI), worry (PSWQ), perceived stress (PSS), and avoidant attachment (ECR-AVOID) were associated with greater heart rate reactivity to the child-focused stress task. When these variables were entered simultaneously into an MLR model, the resultant model accounted for 23% of the variance in heart rate reactivity [F(4,33) = 3.82, P = .01, adjusted R2 = .233]. In this model, only self-reported levels of maternal worry (PSWQ) remained significant following control for the other variables (β = .56, P = .012). In contrast, the only correlate of diastolic blood pressure reactivity was mother’s self-reported history of childhood emotional abuse (Spearman ρ = .32, P <.05).

DISCUSSION

Offspring of depressed mothers are at elevated risk for psychiatric disorders. In her intergenerational interpersonal stress model of depression, Hammen posits that maternal depression is associated with high levels of maternal interpersonal distress and impaired parenting skills [24,5]. Both of these factors, in turn, have detrimental effects on children’s interpersonal function and psychiatric outcomes.

Interpersonal disputes with one’s school-aged children represent an all-too-common event in the daily lives of mothers, and may be of particular significance for depressed mothers who are parenting psychiatrically ill children. Depressed mothers facing the chronic stress of parenting a psychiatrically ill child may be more likely to respond to child-focused stressors with elevated levels of emotional and physiological reactivity. Over time, these responses may have detrimental effects on maternal psychiatric outcomes, maternal parenting skills, and ultimate child psychiatric outcomes.

This study was developed to pilot a set of procedures designed to evaluate the emotional and physiological reactivity of depressed mothers to a child-focused interpersonal stress task. Results support the feasibility and utility of this assessment approach. Preliminary data suggest that depressed mothers receiving minimal-treatment TAU displayed high levels of child-focused stress reactivity as assessed via acute changes in depressed mood state, heart rate, and diastolic blood pressure, particularly as compared with the relatively low levels of reactivity displayed by nondepressed mothers of psychiatrically healthy children. In contrast, depressed mothers receiving IPT-MOMS displayed a reactivity profile that fell between those displayed by the minimally reactive controls and the highly reactive depressed mothers receiving TAU. Finally, results suggest that chronic levels of parental stress and maternal history of emotional abuse are independently associated with depressive mood reactivity, while chronic worry is independently associated with heart rate reactivity. Although preliminary in nature, these findings are nevertheless provocative, and may help to guide future, more definitive work in this area.

There are a number of limitations to the current report that should be considered. First, this investigation represented a feasibility study, and thus was underpowered to adequately test all group contrasts. Second, the nondepressed control mothers were recruited from the community and their offspring generally did not suffer from psychiatric illness. Thus, this study cannot tease out whether differences in reactivity observed between depressed and nondepressed mothers were the result of mothers’ depression, their children’s psychiatric problems, or some combination of the two. While we would favor the latter interpretation, future studies that include adequately sized samples of depressed and nondepressed mothers of psychiatrically ill children, as well as depressed and nondepressed mothers of psychiatrically healthy children, would be needed to examine this question directly. Indeed, identifying protective factors that may operate among nondepressed mothers parenting psychiatrically ill children may help to guide the development of targeted maternal or family-based interventions.

Third, this study was not designed to evaluate prospective changes in stress reactivity that might be observed over the course of an active treatment such as IPT-MOMS. Decisions regarding the timing and cross-sectional nature of this pilot protocol were largely determined by pragmatic constraints imposed by the parent study. Larger studies that include both pre- and post-treatment assessments are needed to test the impact of maternal depression treatment on maternal stress reactivity.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the current interpersonal stress task was, in fact, interpersonal by proxy. We evaluated mothers’ stress reactivity while they delivered a speech about a recent conflict with their child. The child in question was not in the room, and thus the mothers did not interact directly with their child during the task. Future research that examines the emotional and physiological reactivity of depressed mothers while they are discussing an issue of conflict with their child would provide further insight into dyadic patterns of interpersonal stress reactivity.

CONCLUSIONS

The current pilot study represented a novel approach to examining indicators of child-focused stress reactivity among depressed mothers of psychiatrically ill children. Preliminary results suggest that depressed mothers of psychiatrically ill children display elevated levels of emotional and cardiovascular reactivity to child-focused interpersonal stressors. Individual differences in maternal reactivity to the child-focused stressor were associated not only with maternal psychiatric symptoms, but also with mother’s self-reported levels of chronic parental stress and their own history of childhood emotional abuse. The current findings are provocative, and provide suggestive support for the idea that maternal depression treatment may serve to decrease levels of acute reactivity to child-focused stressors. Given the prevalence of depression among mothers, and the significant, cross-generational impact that maternal depression has on both mothers and their children, future, more definitive research in this area is clearly needed.

Acknowledgments

The current study was supported by NIH grants MH64518 (Dr. Swartz) and MH64144 (Dr. Cyranowski), and the Pittsburgh Mind-Body Center (NIH grants HL076852/076858). The authors thank the clinical staff of the WPIC Depression and Manic-Depression Prevention Program, as well as all of the women who participated in the current research. Some of the findings presented in this paper were presented at the Second International Conference on Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Toronto, Ontario (November, 2006).

Footnotes

This article is a US Government work and, as such, is in the public domain in the United States of America.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry. 2006a;163:1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al. Remission in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006b;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammen C. Depression Runs in Families: The Social Context of Risk and Resilience in Children of Depressed Mothers. New York: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA. Intergenerational transmission of depression: test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:511–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson J, Sweeney EM, Geller JL. Mothers with mental illness: the competing demands of parenting and living with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:635–642. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholson J, Henry AD, Clayfield JC, Phillips SM. Parenting Well When you’re Depressed. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swartz HA, Zuckoff A, Frank E, et al. An open-label trial of enhanced brief interpersonal psychotherapy in depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:398–404. doi: 10.1002/da.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartz HA, Frank E, Zuckoff A, et al. Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081339. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNair PM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. POMS Manual. 2nd ed. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shacham S. A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J Pers Assess. 1983;47:305–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): psychometric information. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Revised Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkoved TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1983;13:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norris FH, Uhl GA. Chronic stress as a mediator of acute stress: the case of Hurricane Hugo. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1993;23:1263–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klohnen EC, Bera S. Behavioral and experiential patterns of avoidantly and securely attached women across adulthood: a 31-year longitudinal perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:211–223. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bremner JD, Vermetten E, Mazure CM. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of an instrument for the measurement of childhood trauma: The Early Trauma Inventory. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12:1–12. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<1::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammen C. Interpersonal stress and depression in women. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]