Abstract

There remains a great need for effective, cost-efficient, and acceptable youth smoking cessation interventions. Unfortunately, only a few interventions have been demonstrated to increase quit rates among youth smokers, and little is known about how elements of cessation interventions and participants’ psychosocial characteristics and smoking histories interact to influence program outcomes. Additionally, few studies have examined how these variables lead to complete smoking abstinence, reduction or acceleration over the course of a structured cessation intervention. Data for the present investigation were drawn from a sample of teen smokers (n = 5892) who voluntarily participated in either a controlled study or field study (i.e., no control group) of the American Lung Association's Not On Tobacco (N-O-T) program between 1998 and 2006 in five states. Results suggest that those who reduce smoking (but do not achieve full abstinence) are similar to those who quit on most measures except stage of change. Furthermore, it was found that those who increased smoking were heavier smokers at baseline, more addicted, were more likely to have parents, siblings, and significant others who smoked and reported less confidence in and less motivation for quitting than did those who quit or reduced smoking. Finally, a path model demonstrated how peers, siblings and romantic partners affected tobacco use and cessation outcomes differently for males and females. Implications for interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Adolescent, Smoking, Cessation, Not On Tobacco, Path analysis

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking is responsible for more annual deaths in the United States than illicit drug and alcohol use, motor vehicle accidents, suicide and murders combined (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005). Adolescence is a critical period for smoking initiation; almost 4000 youth initiate tobacco use every day (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). If these smokers continue their habit into adulthood, they can expect to spend over $75,000 in excess medical care related to their smoking, and a life expectancy up to 20 years shorter than non-smokers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). However, those who quit smoking earlier in life can regain their health and anticipate a normal life span (Ostbye et al., 2002). Given the early age of smoking initiation and the dramatic implications of decreased quality of life, increased economic costs, and risk of early death associated with smoking, there remains a great need for effective, cost-efficient, and acceptable youth smoking cessation interventions (Lantz et al., 2000).

Unfortunately, only a few interventions have been demonstrated to increase quit rates among youth smokers. A recent Cochrane review notes that only one psychosocial intervention, the American Lung Association's Not On Tobacco (N-O-T) program, shows promise as an effective cessation program for adolescents (Grimshaw and Stanton, 2006). In addition to a relative shortage of research on youth tobacco cessation interventions in general (Backinger et al., 2003), there is a clear need to increase the understanding of how specific intervention elements and participants’ psychosocial characteristics may influence program outcomes, and how these factors are related to developmental issues (Garrison et al., 2003).

Unfortunately, existing theoretical approaches have struggled to effectively assist in the effort to characterize youth smoking cessation. In a review of sixty-six cessation studies, it was discovered that at least eight different theoretical approaches were used across all programs, and that many of these programs used bit and pieces of difference theories (Sussman, 2002). Whereas Sussman found that transtheoretical and contingency management theoretical approaches demonstrated some advantages over other theoretical programs, and other theoretical models have been successfully evaluated (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior; Norman et al., 1999), there exists no single theory of adolescent smoking cessation which suggests how social context, smoking history, and level of addiction may work together to influence key predictors of cessation (e.g., stage of change, motivation) and cessation itself.

Whereas theoretical approaches have had difficulty capturing smoking cessation among youth, a number of epidemiological studies have examined and identified psychosocial predictors of smoking cessation (Ellickson et al., 2001; Pederson et al., 1998; Tyas and Pederson, 1998; Vink et al., 2003a,b; Zhu et al., 1999). Attributes that have consistently emerged as important cessation predictors are smoking history, frequency of smoking, level of nicotine dependence and age of first use (Breslau, 1996; Horn et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 1999), presence of family members or peers who smoke (Tucker, 2002; Ellickson et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2001) motivation for quitting and confidence in cessation (Dino et al., 2004; Sargent et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1999). Despite these important findings, questions remain. For example, some studies have found no differences between quitters and non-quitters in smoking history or psychological characteristics (Chen et al., 2001), no differences in variables that influence motivation (Engels et al., 1998a), and that the influence of individual, historical and contextual variables may differ based on gender (Tucker, 2002). In addition, a large number of youth smoking cessation studies have been criticized for methodological and measurement problems (Backinger et al., 2003; Mermelstein et al., 2002; Tyas and Pederson, 1998). One critical concern has been the measurement of smoking abstinence in youth populations. Research suggests that adolescents may have irregular smoking patterns that differ from those of adults and may define their own cessation differently than do adults. For example, teens may not consider themselves quitters even after prolonged periods of abstinence (Mermelstein et al., 2002; Mermelstein, 2003). Moreover, there is a paucity of data on the developmental process of how adolescents change smoking patterns over time. Consequently, there is a need to examine how cessation predictors may be related to changes in adolescent smoking patterns in addition to exploring total abstinence. To illustrate, there are four possible outcomes for a smoking cessation intervention: (1) quitting, (2) no change in use, (3) reducing use, and (4) increasing use. Very few studies examine the latter two outcomes. In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of intervention outcomes and to insure these interventions are best serving their clientele, it may be important to identify and compare the characteristics of teen participating in cessation programs who quit, those who reduce use, and those who are genuine treatment failures (i.e., those who increase use).

Finally, and critically, much of the prior work examining predictors of quitting has utilized population-based approaches and has not delineated the specific methods of cessation. Although these population-based studies are instructive, they do not identify predictors of smoking cessation when individuals are utilizing structured, evidence-based cessation interventions. An understanding of how individual, familial, and contextual factors work together with specific interventions will help guide dissemination, acceptability, recruitment and outcome research and ultimately improve the overall effectiveness of the interventions.

The present paper addresses some of these knowledge gaps by exploring how smoking history, intervention readiness, and social context predict three possible outcomes (cessation, reduction, and increased use) to an evidence-based, widely disseminated school-based cessation program. Additionally, the present paper systematically evaluates a conceptual path model of how contextual and individual factors interact to influence smoking outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data for the present investigation were drawn from a sample of teen smokers (n = 5892) who voluntarily participated in either a controlled study or field study (i.e., N-O-T program only; no control group) of the American Lung Association's Not On Tobacco (N-O-T) program between 1998 and 2006 (Horn et al., 2005). Participants represented five states FL (n = 4007), NC (n = 71), NJ (n = 750), WI (n = 947), and WV (n = 117), and were between 14 and 19 years of age (M = 16; S.D. = 1.15). Females constituted 55% of the sample, and a majority of teens were Caucasian (74.75%). Refer to Table 1 for additional descriptive data. All study procedures were administered according to a protocol approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board. Participants did not receive compensation for participation.

Table 1.

Sample demographics

| Total |

Male |

Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age | ||||||

| 14 | 514 | 8.7 | 177 | 6.8 | 336 | 10.2 |

| 15 | 1479 | 25.1 | 603 | 23.1 | 876 | 26.7 |

| 16 | 1787 | 30.3 | 761 | 29.2 | 1025 | 31.2 |

| 17 | 1482 | 25.2 | 720 | 27.6 | 762 | 23.2 |

| 18 | 568 | 9.6 | 307 | 11.8 | 261 | 7.9 |

| 19 | 62 | 1.1 | 38 | 1.5 | 24 | .7 |

| Grade | ||||||

| 7 | 14 | .2 | 6 | .2 | 8 | .2 |

| 8 | 72 | 1.2 | 30 | 1.2 | 42 | 1.3 |

| 9 | 1482 | 25.2 | 644 | 24.7 | 837 | 25.5 |

| 10 | 1653 | 28.1 | 705 | 27.1 | 948 | 28.9 |

| 11 | 1540 | 26.1 | 669 | 25.7 | 870 | 26.5 |

| 12 | 1059 | 18.0 | 518 | 19.9 | 541 | 16.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 4234 | 71.9 | 1799 | 69.0 | 2434 | 74.1 |

| African American | 214 | 3.6 | 109 | 4.2 | 104 | 3.2 |

| American Indian | 79 | 1.3 | 36 | 1.4 | 43 | 1.3 |

| Asian American | 104 | 1.8 | 59 | 2.3 | 45 | 1.4 |

| Hispanic | 711 | 12.1 | 359 | 13.8 | 352 | 10.7 |

| Native Hawaiian | 19 | .3 | 9 | .3 | 10 | .3 |

| Other/multi-racial | 303 | 5.1 | 130 | 5.0 | 173 | 5.3 |

The N-O-T program was designed specifically for adolescent smokers, using a gender-sensitive, 10-session curriculum. The sessions are delivered by trained facilitators in the schools and other community settings. The program includes modules on life management skills to help teens deal with stress, decision-making and peer and family relationships. It also addresses healthy lifestyle behaviors such as alcohol or illicit drug use as well as related health issues such as exercise and nutrition. Effectiveness studies on the N-O-T program reveal end-of-program intent-to-treat quit rates between 15% and 19% for 1998−2003 (Horn et al., 2005). These rates are among the highest quit rates reported in the literature and have resulted in N-O-T's federal recognition as a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) evidence-based Model Program, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Research Tested Intervention Program, and an Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) Model Program. Moreover, a cost-effectiveness analysis comparing N-O-T to a minimal-contact brief intervention indicated that N-O-T is a highly cost-effective option for school-based tobacco intervention (Dino et al., 2008). Importantly, N-O-T has been disseminated in 48 states and has been rigorously assessed for adoptability. In fact, a recent survey of youth smoking cessation programs found N-O-T to be the most widely used intervention in the nation (Curry et al., 2007).

2.2. Measures

The data were collected using self-report instruments completed by adolescent participants. All measures were administered at the time of program enrollment (“baseline”) prior to participation in the first cessation session. Additionally, all participants were queried about their current smoking status, frequency of smoking on weekdays and weekends following completion of the 10-week study period.

2.2.1. Demographics

Following receiving signed consent and assent forms, all participants completed pencil-and-paper questionnaires regarding their current age, gender, grade in school, ethnicity and current family living situation (e.g., living with biological parents, adoptive parents, a biological and step-parent).

2.2.2. Smoking history

Using pencil-and-paper questionnaires we assessed several dimensions of smoking history previously identified as related to cessation, including: (1) age of first cigarette use (coded as age in years), (2) previous quit attempts (coded as “yes” or “no”), (3) frequency of cigarette use on weekdays and weekends (coded as total number of cigarettes smoked; Dino et al., 2001a,b; Ellickson et al., 2001; Sussman, 1995; Plested et al., 1999) and (4) level of nicotine dependence. All N-O-T studies between 1998 and 2000 assessed nicotine dependence using the eight-item questionnaire Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) developed for adults (Fagerstrom, 1978). In 2001, a version of the FTQ that was specifically developed to assess nicotine dependence in teens was used. This modification is a seven-item revision that eliminates the item related to cigarette brand (Prokhorov et al., 1996; Pomerleau et al., 1994). The FTQ is the most widely used self-reported assessment of nicotine dependence, and has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties, including Chronbach's alpha >70, significant correlation with objective measures of cotinine levels (Prokhorov et al., 2000), and is predictive of smoking cessation (de Leon et al., 2003). In order to have uniform FTQ results across studies, we collapsed data from both versions of the instrument into three levels of nicotine dependence (scores of 0−2 = no dependence or low dependence, scores of 3−5 = moderate dependence, and 6 or higher = high dependence).

2.2.3. Smoking outcomes

For the purposes of this study, we defined cessation as no cigarette use in the past >24 h (1 day; Velicer and Prochaska, 2004). Decreased use was defined as a net reduction in overall cigarette use (combined weekday and weekend use) from baseline to post-program. Increased use was defined as a net increase in cigarette use from baseline to end of the program.

2.2.4. Social context

In the initial pencil-and-paper questionnaires administered at baseline, participants were asked about the smoking status of their parents, their siblings, their friends and their romantic partner (if applicable).

2.2.5. Intervention readiness

To assess participant's readiness to quit smoking, we assessed three separate dimensions supported by the literature (Zhu et al., 1999; Prokhorov et al., 2003; Wang et al., 1999; Curry et al., 1997; Carey, 1999; Biener and Abrams, 1991). These three dimensions are motivation to quit, confidence to quit, and stage of change. To assess motivation, we asked participants to rate, on a five-point scale, how motivated they were to stop smoking (1 = not motivated; 5 = very highly motivated). To assess confidence in quitting, we asked participants to rate, on a five-point scale, how confident they were that they would be able to stop smoking (1 = not confident; 5 = very highly confident). These questions in this format have been used in a number of studies of the N-O-T program, and have been found to be associated with stage of change and cessation outcomes (Dino et al., 2001a,b, 2004; Horn et al., 2005, 2004). Finally, our stage of change assessment included response options suggested by Prochaska and colleagues in the transtheoretical model (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983), specifically: (1) precontemplation (“do not plan to quit in next 6 months”), (2) contemplation (“plan to quit in next 6 months”), (3) preparation (“plan to quit in next 30 days”), (4) action (“made a serious quit attempt in past 6 months”), and (5) maintenance (“quit less than 6 months ago”). Again, these items have been used in numerous studies of the N-O-T program, and have been associated with end-of-program outcomes (Dino et al., 2004; Horn et al., 2005).

2.3. Analytic plan

The analytic process was completed in two stages. First, we examined how adolescents who achieved complete smoking abstinence (quitters) differed from those who reduced cigarette use from baseline (reducers) and those who increased use from baseline (increasers) on measures of smoking history, contextual factors and intervention readiness. For analyses involving categorical outcome, we used a test of homogeneity of proportions (Fleiss, 1981), a procedure similar to the chi-square goodness of fit test. The test of proportions applies the following formula to yield a z-score indicating differences in proportions:

In this formula, p1 is equal to the proportion in group 1, p2 is the proportion in group 2, and P is the pooled proportion between groups 1 and 2. Resultant z-scores are then compared to a standard normal distribution table to determine 2-tailed significance. Additionally, for outcomes on a continuous scale (e.g., ratio/interval), we used ANOVA analyses and t-test, where appropriate, to determine group differences.

Next, we used structural equation modeling (SEM; specifically, we utilized path analysis techniques) using AMOS 7.0 software (Arbuckle, 2006) to examine how smoking history, contextual factors and intervention readiness interact to influence smoking outcomes. We selected SEM because of its flexibility to analyze covariance, means, deal with multicolinearity, model measurement error, and to examine the direct and indirect effects of a range of predictors and potential mediators on outcomes. Additionally, the use of SEM to evaluate smoking treatment outcomes has been recognized as a desirable way to develop sophisticated models that are “well suited for determining the influence of complex sets of mediators and predictors on a complex outcome” (Williams et al., 2005, p. 14). Evaluation of the overall data-model fit was done using standard chi-square, CFI (comparative fit index), and RMSEA (root mean square of approximation) fit indices.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Prior research indicates that adolescent males and female may differ in their smoking patterns and in the factors, which influence cessation outcomes (Tucker et al., 2002). Therefore, we presented descriptive sample characteristics by gender in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of study variables at baseline

| Total |

Male |

Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age of first try | ||||||

| <9 years | 764 | 13.0 | 375 | 14.4 | 389 | 11.8 |

| 10−14 years | 4376 | 74.3 | 1839 | 70.6 | 2535 | 77.2 |

| >15 years | 752 | 12.8 | 392 | 15.0 | 360 | 11.0 |

| Level of nicotine dependence | ||||||

| Low | 72 | 11.0 | 32 | 11.3 | 40 | 10.8 |

| Moderate | 197 | 30.0 | 78 | 27.5 | 119 | 32.0 |

| High | 387 | 59.0 | 174 | 61.3 | 213 | 57.3 |

| Tried to quit | 4537 | 78.2 | 1943 | 74.8 | 2592 | 80.1 |

| Parent smokes | 1492 | 65.3 | 646 | 64.8 | 846 | 65.7 |

| Sibling smokes | 1068 | 55.2 | 449 | 54.1 | 619 | 56.1 |

| Friend smokes | 2143 | 93.5 | 934 | 93.7 | 1208 | 93.3 |

| Boy/girlfriend smokes | 149 | 59.8 | 42 | 46.7 | 107 | 67.3 |

| Stage of change | ||||||

| Precontemplation | 168 | 11.9 | 89 | 14.0 | 79 | 10.2 |

| Contemplation | 723 | 51.3 | 318 | 50.1 | 405 | 52.3 |

| Preparation | 301 | 21.3 | 139 | 21.9 | 161 | 20.8 |

| Action | 218 | 15.5 | 89 | 14 | 129 | 16.7 |

| Maintenance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Motivation to quit | ||||||

| None | 26 | 2.5 | 16 | 3.3 | 10 | 1.8 |

| Low | 178 | 16.8 | 70 | 14.3 | 108 | 18.9 |

| Moderate | 503 | 47.4 | 237 | 48.3 | 266 | 46.7 |

| High | 276 | 26.0 | 128 | 26.1 | 148 | 26.0 |

| Very high | 78 | 7.4 | 40 | 8.1 | 38 | 6.7 |

| Confidence in quitting | ||||||

| None | 37 | 3.9 | 21 | 4.7 | 16 | 3.1 |

| Low | 214 | 22.4 | 90 | 20.1 | 124 | 24.4 |

| Moderate | 474 | 49.6 | 210 | 47.0 | 264 | 51.9 |

| High | 172 | 18.0 | 89 | 19.9 | 83 | 16.3 |

| Very high | 59 | 6.2 | 37 | 8.3 | 22 | 4.3 |

| Quit use | 879 | 23.4 | 632 | 24.3 | 745 | 22.7 |

| Reduced use | 3635 | 61.7 | 1582 | 60.7 | 2052 | 62.5 |

| Increased use | 1378 | 14.9 | 392 | 15.0 | 487 | 14.8 |

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes per weekday, baseline | 12.0 | 10.4 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 11.1 | 9.2 |

| Cigarettes per weekend, baseline | 18.2 | 12.6 | 19.0 | 13.5 | 17.7 | 11.9 |

| Cigarettes per weekday, F/U-up | 7.5 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

| Cigarettes per weekend, F/U-up | 12.1 | 10.2 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 9.5 |

3.1.1. Demographics

Overall, there were significant differences between males and females on several variables. Males were older, t(5888) = 8.21, p < .001, smoked more cigarettes on weekdays at baseline, t(5839) = 7.04, p < .001 and smoked more cigarettes on weekends at baseline, t(5805) = 3.82, p < .001 than did their female counterparts. Additionally, a significantly higher proportion of females reported previous quit attempts than did males, z = 2.75, p = .006, and a higher proportion of females than males reported having a boy/girlfriend who smoked, z = 10.03, p < .001. There were no differences on any study variables based on the state in which participants lived. Overall attrition rates across studies were 20.6%, and no differences were found on studies variables between study completers and drop outs.

3.1.2. Smoking history

Increasers were found to be significantly older than were quitters or reducers, F(2, 5889) = 12.46, p < .001, to smoke more on the weekdays at baseline, F(2, 5836) = 82.40, p < .001, and to smoke more on the weekends at baseline, F(2, 5806) = 108.87, p < .001 than were quitters and reducers. We also found that a significantly higher proportion of increasers were classified as “highly” nicotine dependent than were reducers, z = 4.55, p < .001, and quitters, z = 11.02, p < .001.

3.1.3. Social context

A significantly higher proportion of increasers reported having a parent who smokes, z = 2.64, p = .008 than did quitters. Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of those increasers reported having friends who smoke than did reducers, z = 2.33, p = .02, and quitters, z = 2.11, p = .03. Moreover, a greater proportion of those who increased use reported having siblings who smoke than did those who reduced use, z = 3.03, p = .002 and those who quit use, z = 3.27, p = .001. Finally, it was found that a greater proportion of increasers reported having a boy or girlfriend who smokes than did those who reduced use, z = 4.72, p < .001, and those who quit, z = 3.32, p = .001.

3.1.4. Intervention readiness

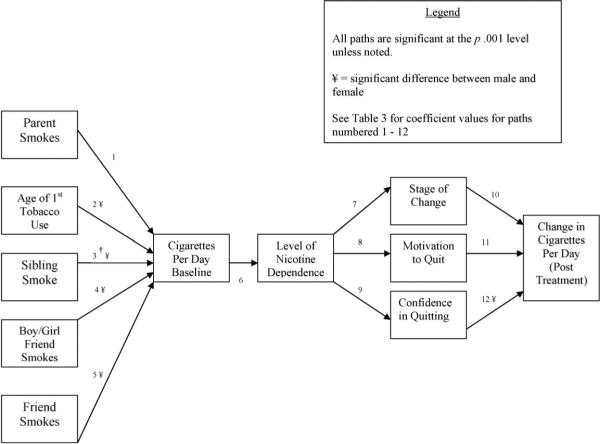

We used one-way ANOVA analyses (see Fig. 1) to examine how those who increased use, reduced use and quit use differed in confidence in quitting and motivation to quit. Increasers were significantly more likely than reducers and quitters to have low motivation, F(2, 1058), p < .001, and low confidence, F(2, 953), p = .001. We used tests of homogeneity of proportions to examine how the three groups differed in stage of change. Results found that a greater proportion of increasers were in the precontemplation stage than were reducers, z = 2.8, p = .005, and quitters, z = 6.5, p < .001. Likewise, there was a significantly higher proportion of reducers in the precontemplation stage than quitters, z = 3.7, p < .001. Interestingly, it was found that a significantly higher proportion of reducers reported being in the contemplation stage than did quitters, z = 3.25, p = .001, and increasers, z = 4.29, p < .001. Next, it was found that there was a significantly higher proportion of quitters in the preparation stage than reducers, z = 3.95, p = < .001 and increasers, z = 3.3, p < .001. Finally, as expected, there was a significantly higher proportion of quitters in the action stage than reducers, z = 3.00, p = .002 and increasers, z = 2.15, p = .03.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of quitters, reducers and increasers on baseline stage of change.

3.2. Path model of outcomes

3.2.1. Path analysis

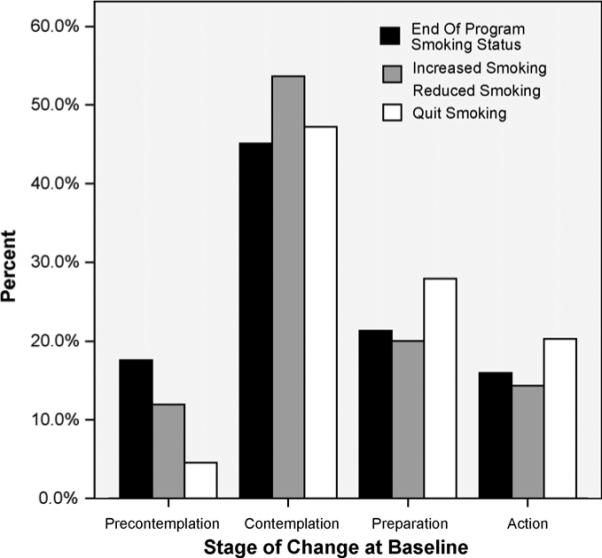

Because no comprehensive theory of adolescent smoking cessation exists which simultaneously accounts for social context, history of smoking, nicotine dependence, and intervention readiness, we developed our prediction model of cessation based on different aspects of several theories. For example, social learning theory (Akers and Lee, 1996) and the social development model (Hawkins and Weis, 1985) would suggest how peers and parents may relate to adolescent smoking (left side of Fig. 2). Likewise, the transtheoretical model would suggest how stage of change and motivation may relate to cessation outcomes (right side of Fig. 2). Additionally, our prediction model incorporated empirical evidence which may suggest how earlier onset of smoking may lead to increased tobacco use and nicotine dependence over time, how increased tobacco use leads to increase nicotine dependence, and how variables such as confidence in cessation may be related to outcomes (e.g., Zhu et al., 1999; Tyas and Pederson, 1998; Tucker, 2002; Sussman et al., 1998; Sargent et al., 1998; Horn et al., 2003; Engels et al., 1998a; Ellickson et al., 2001; Dino et al., 2004). The model shown in Fig. 2 was found to have acceptable data-model fit indices, X2 = 149.25, d.f. = 29, p < .001; CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03, 9% CI = .022−.031. It should be noted that the outcome, labeled “end of program smoking,” was calculated by subtracting average end-of program cigarettes smoked from average baseline cigarettes smoked. Therefore, this variable represents a change in overall smoking.

Fig. 2.

Path model of adolescent smoking cessation.

Fig. 2 demonstrates the influence of contextual variables and smoking history on the average number of cigarettes smoked per day at baseline. Specifically, it was found that the parent, peer, sibling, and romantic partner smoking are all associated with an increase in mean cigarettes smoked at baseline. Additionally, it was found that smoking at an earlier age was associated with an increased number of cigarettes smoked at baseline. Next, the model depicts a significant relation between number of cigarettes smoked at baseline and an increased level of nicotine dependence, and a relation between increased nicotine dependence, a lower stage of change classification, and less motivation and confidence in quitting. Finally, the model demonstrates how increased confidence, motivation and a higher stage of change classification are associated with a decrease in smoking from baseline. See Table 3 for standardized and unstandardized coefficient values by gender.

Table 3.

Standardized and unstandardized path coefficients by gender

| Path # | Male |

Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | β | B | S.E. | β | |

| 1 | 2.10 | .47 | .07 | 2.96 | .58 | .08 |

| 2 | −1.43 | .32 | −.07 | −2.82 | .34 | −.14¥ |

| 3 | .80 | .49 | .03† | 2.68 | .60 | .07¥ |

| 4 | 41.39 | 1.13 | .61 | 57.47 | 1.34 | .73¥ |

| 5 | 28.36 | .95 | .46 | 31.95 | 1.16 | .43¥ |

| 6 | .04 | .01 | .82 | .04 | .02 | .85 |

| 7 | −.37 | .03 | −.28 | −.30 | .02 | −.26 |

| 8 | −.19 | .02 | −.18 | −.18 | .02 | −.18 |

| 9 | −.17 | .02 | −.19 | −.17 | .02 | −.19 |

| 10 | .39 | .03 | .24 | .42 | .03 | .24 |

| 11 | .36 | .05 | .17 | .41 | .05 | .20 |

| 12 | .31 | .05 | .13 | .11 | .05 | .05¥ |

Note: B/S.E. represent unstandardized coefficient values. β represents standardized coefficient values. All paths are significant at the p < .01 level, except

= not significant

= significant difference between male and female coefficients.

To examine how the relations among model variables differ by gender, we ran two models; the first with male participants and the second with female. It should be noted that the variables in the present study have been found to be invariant across gender (Branstetter et al., 2007). We then evaluated the difference in coefficient values between males and females. All but one coefficient was significant for both males and females; therefore we used a Student's t-test to evaluate if the strength of these relations differed significantly by gender. This method of comparing regression coefficients is based on the following formula:

In this formula b1 is the unstandardized path coefficient for females, b2 is the unstandardized path coefficient for males, and Sb1 and Sb2 are the standard errors of path coefficients b1 and b2, respectively.

Results demonstrate that having a sibling who smokes was significantly related to the number of cigarettes smoked at baseline for females, but not for males. Additionally, the relation between having a friend who smokes and number of cigarettes smoked at baseline was significantly stronger for females than it is for males, t(5886) = 2.39, p = .02. Likewise, having a boy or girlfriend who smokes was more strongly associated with number of cigarettes smoked at baseline for females than it is for males, t(5886) = 9.17, p < .001. There was no difference between the gender on the relation between parental smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked at baseline. Finally, age of first cigarette use was more strongly associated with number of cigarettes smoked at baseline for females than it was for males, t(5886) = 3.64, p < .001. Finally, it was demonstrated that confidence in quitting was a significantly stronger predictor of outcome for males than it was for female, t(5886) = −3.09, p < .001.

4. Discussion

This paper examines the predictors of smoking cessation program outcomes among teens who participated in the American Lung Association's N-O-T program, a structured, evidence-based, widely disseminated intervention. Specifically, we compared predictors associated with three program outcomes: (1) cessation, (2) reduction, and (3) increased use. Conventionally, cessation intervention studies focus on quitting only; that is, participants who report complete abstinence from cigarette smoking at the designated point of observation. A few youth cessation studies report information on reducers (Dino et al., 2004; Horn et al., 2004); even fewer report information on increasers. This investigation allowed us to characterize not only quitters, but to examine reducers and increasers as well.

Our results demonstrated that reducers were similar to quitters with only a few exceptions. For example, quitters were more likely to enter treatment in the preparation stages than were reducers and increasers. Interestingly, reducers were more likely than both quitters and increasers to enter treatment in the contemplation stage.

In contrast, increasers looked distinctly different than participants who showed favorable change in cigarette smoking (i.e., quitters or reducers). From a program effectiveness standpoint, increasers represent clear program failures. We believe that garnering an understanding of our treatment failures will be invaluable in developing additional strategies to reach this population. Furthermore, given that reducers seem to be more similar to quitters than dissimilar, we believe that categorizing reducers and increasers into a single category (e.g., “non-quitters”) may make it more difficult to identify those individuals who are at greatest risk for continued smoking (i.e., increasers) and the related health problems associated with smoking. This study found that treatment failures had significant psychosocial challenges at program entry. They were heavier smokers at baseline; more addicted; and were more likely to have parents, siblings, and significant others who smoked than were youth who quit or reduced smoking. Understandably, increasers also reported less confidence in and less motivation for quitting; they were also were more likely to be in the earlier stages of change than were their counterparts who quit or reduced.

In spite of these challenges, these individuals chose to join an intensive, 10-session cessation program. This choice provides the field of teen smoking cessation with an opportunity and, more importantly, an obligation specifically target the special challenges and needs of these teens. It is incumbent upon researchers and practitioners to work together to modify existing methods, identify and incorporate additional program components, and offer evidence-based ancillary strategies, so that our present program failures may become future successes. Possibilities include additional guidance and support for dealing with friends and family who smoke, enhancements to increase motivation and confidence, and further incorporation of strategies specifically designed for precontemplators and contemplators.

It is also possible that these treatment improvements may help increase the reach of existing efforts to teens who currently do not seek help with cessation. It is important to note that treatment improvements must be accompanied by effective “marketing” strategies to increase the likelihood that teens will both join and be helped by improved interventions.

Our path model demonstrated several important findings about the pathways to cessation, and may help integrate or expand theories of cessation. First, it suggests how environmental (family and peer use) and history of smoking factors (age of first use) combine to influence the amount of smoking prior to intervention, which in turn relates to program outcomes. It further demonstrates how the number of cigarettes smoked increases nicotine dependence, which in turn has a strong negative influence on stage of change, motivation and confidence in quitting. Specifically, this model suggests that teens with higher levels of nicotine dependence may be less ready to quit, have less motivation and less confidence in quitting than those with lower levels of dependence. This model demonstrates how aspects of the social development model, which holds that important socialization units (e.g., parents, peers, romantic partners) are key predictors of behavior, may combine with a behavioral history (e.g., age of smoking onset) to influence current smoking behavior.

Consistent with both theoretical and empirical work (Dino et al., 2004; Engels et al., 1998b; Pallonen et al., 1998), the model demonstrates that readiness to quit as assessed through motivation, stage of change and confidence in quitting ability is strongly related to actual treatment program outcomes. Finally, this path model suggests that there are important differences in the path to cessation outcome between males and females. For example, having a sibling who smokes is strongly related to mean cigarettes per day for females, but not for males. Additionally, the strength of the relations between several of the variables in the path models is significantly different for males and females. For example, having a romantic partner who smokes has a significantly stronger relation to cigarettes smoked per day among females than among males. This relates to previous research that social support may be a more important predictor of cessation for females than for males, and that confidence in quitting is more associated with successful cessation among males than females (Gritz et al., 1996). Indeed, the implication of the present study support the notion that adolescent smoking cessation interventions should emphasize gender sensitivity, and perhaps emphasize issues of social context for females more so than for males.

Programs such as N-O-T are specifically designed to provide the tools necessary to help teens quit smoking. However, they also create an opportunity to promote smoking cessation among those who are not yet able or ready to completely quit. Although reduction is a sub-optimal outcome, reduction may be clinically significant. Although some researchers argue against the positive impacts of reduction, many studies have reported that smoking reduction may parallel harm reduction, and that a reduction in smoking does not undermine future cessation attempts (Hughes, 2000). Furthermore, smoking reduction may have a positive influence on increased motivation to quit (Etter et al., 2003; Fagerstrom, 1999). Because reducers maybe primed for complete cessation in the near future, it is important for researchers and practitioners to offer additional cessation strategies to teens who reduce smoking. Additionally, it may be important to examine if attending programs such as N-O-T more than once is an effective way to move reducers to complete cessation.

The present study is not without its limitations, and the results should be interpreted with those limitations in mind. For example, all data collected in the present study come from self-report instruments from the individual participants. Biological markers of smoking status and data from multiple reporters (e.g., parents, siblings, friends) could yield more valid results and produce greater confidence. Second, the present study is based on end-of-program outcomes, using intent-to-treat, 24-h point prevalence. Future work needs to examine these issues in the light of sustained cessation 6 and 12 months post-program, under longer term point prevalence, such as 30 days (Velicer and Prochaska, 2004). Third, this study examines findings from only one cessation program. It is not clear how these findings would be related to other quit smoking interventions.

Nevertheless, the present findings provide the first look at the differences among teens who quit, reduce, or increase cigarette use as a result of participation in an evidence-based, widely available cessation intervention. The study also provides a conceptual model of how contextual and individual factors interact to influence quitting, reduction, and acceleration of smoking. Finally, it is our intent that the findings from this analysis encourage the development of improved strategies to increase the number of youth who are able to quit smoking completely, thereby addressing a public health problem of the highest priority.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the Translational Tobacco Reduction Research Program (T2R2) at the Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center at West Virginia University for feedback and contributions to this study.

Role of funding source: There was no external funding provided by any source for the present study.

Footnotes

5. Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Akers RL, Lee G. A longitudinal test of social learning theory: adolescent smoking. J. Drug Issues. 1996;26:317–343. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 User’s Guide. SPSS; Chicago: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Backinger CL, Fagan P, Matthews E, Grana R. Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: current status and future directions. Tob. Control. 2003:12. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The contemplation ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branstetter S, Horn K, Dino G. Factor structure of youth tobacco use measures: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. West Virginia University; 2007. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. Smoking cessation in young adults: age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. Am. J. Public Health. 1996;86:214–220. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey K. Assessing readiness to change substance abuse: a critical review of instruments. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1999;6:245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 1997−2001. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2005;54:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [07.15.08];Smoking-attributable mortality, morbidity, and economic costs. 2006 Available: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/sammec/

- Chen PH, White HR, Pandina RJ. Predictors of smoking cessation from adolescence into young adulthood. Addict. Behav. 2001;26:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, Emery S, Sporer AK, Mermelstein R, Flay BR, Berbaum M, et al. A national survey of tobacco cessation programs for youths. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97:171. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, Grothaus L, McBride C. Reasons for quitting: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation in a population-based sample of smokers. Addict. Behav. 1997;22:727–739. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon J, Diaz FJ, Becona E, Gurpegui M, Jurado D, Gonzalez-Pinto A. Exploring brief measures of nicotine dependence for epidemiological surveys. Addict. Behav. 2003;28:1481–1486. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dino G, Horn K, Abdulkadri A, Kalsekar I, Branstetter S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the not on tobacco program for adolescent smoking cessation. Prev. Sci. 2008;9:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dino G, Horn K, Goldcamp J, Fernandes A, Kalsekar I, Massey C. A 2-year efficacy study of not on tobacco in Florida: an overview of program successes in changing teen smoking behavior. Prev. Med. 2001a;33:600–605. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dino G, Kamal K, Horn K, Kalsekar I, Fernandes A. Stage of change and smoking cessation outcomes among adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2004;29:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dino GA, Horn KA, EdD MSW, Goldcamp J, Maniar SD, Fernandes A, Massey CJ. Statewide demonstration of not on tobacco: a gender-sensitive teen smoking cessation program. J. Sch. Nurs. 2001b;17:90–97. doi: 10.1177/105984050101700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McGuigan KA, Klein DJ. Predictors of late-onset smoking and cessation over 10 years. J. Adolesc. Health. 2001;29:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RC, Knibbe RA, de Vries H, Drop MJ. Antecedents of smoking cessation among adolescents: who is motivated to change? Prev. Med. 1998a;27:348–357. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME, Knibbe RA, de Vries H, Drop MJ. Antecedents of smoking cessation among adolescents: who is motivated to change? Prev. Med. 1998b;27:348–357. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, le Houezec J, Landfeldt B. Impact of messages on concomitant use of nicotine replacement therapy and cigarettes: a randomized trial on the Internet. Addiction. 2003;98:941–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict. Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO. Interventions for treatment-resistant smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 1999;1:201–205. doi: 10.1080/14622299050012071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd edition John Wiley; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison MM, Christakis DA, Ebel BE, Wiehe SE, Rivara FP. Smoking cessation interventions for adolescents: a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003;25:363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw G, Stanton A. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. The Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006;(Issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. Art. No.: CD003289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Nielsen IR, Brooks LA. Smoking cessation and gender: the influence of physiological, psychological, and behavioral factors. J. Am. Med. Womens Assoc. 1996;51:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: an integrated approach to delinquency prevention. J. Prim. Prev. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn K, Dino G, Kalsekar I, Mody R. The impact of not on tobacco on teen smoking cessation: end-of-program evaluation results, 1998 to 2003. J. Adolesc. Res. 2005;20:640. [Google Scholar]

- Horn K, Fernandes A, Dino G, Massey CJ, Kalsekar I. Adolescent nicotine dependence and smoking cessation outcomes. Addict. Behav. 2003;28:769–776. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn KA, Dino GA, Kalsekar ID, Fernandes AW. Appalachian teen smokers: not on tobacco 15 months later. Am. J. Public Health. 2004;94:184–191. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Reduced smoking: an introduction and review of the evidence. Addiction. 2000;95:3–7. doi: 10.1080/09652140032008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Berson J, et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob. Control. 2000;9:47–63. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein R. Teen smoking cessation. Tob. Control. 2003:12. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_1.i25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein R, Colby SM, Patten C, Prokhorov A, Brown R, Myers M, et al. Methodological issues in measuring treatment outcome in adolescent smoking cessation studies. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2002;4:395–403. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000018470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Conner M, Bell R. The theory of planned behavior and smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1999;18:89–94. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostbye T, Taylor DH, Jung SH. A longitudinal study of the effects of tobacco smoking and other modifiable risk factors on ill health in middle-aged and old Americans: results from the health and retirement study and asset and health dynamics among the oldest old survey. Prev. Med. 2002;34:334–345. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallonen UE, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Prokhorov AV, Smith NF. Stages of acquisition and cessation for adolescent smoking: an empirical integration. Addict. Behav. 1998;23:303–324. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson LL, Koval JJ, McGrady GA, Tyas SL. The degree and type of relationship between psychosocial variables and smoking status for students in grade 8: is there a dose–response relationship? Prev. Med. 1998;27:337–347. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plested B, Smitham DM, Jumper-Thurman P, Oetting ER, Edwards RW. Readiness for drug use prevention in rural minority communities. Subst. Use Misuse. 1999;34:521–544. doi: 10.3109/10826089909037229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF. Reliability of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire and the Fager-strom test for nicotine dependence. Addict. Behav. 1994;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, De Moor C, Pallonen UE, Hudmon KS, Koehly L, Hu S. Validation of the modified Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire with salivary cotinine among adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2000;25:429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Stancic N. Adolescent smoking: epidemiology and approaches for achieving cessation. Pediatr. Drugs. 2003;5:1–10. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200305010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L, Niaura R. Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addict. Behav. 1996;21:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Mott LA, Stevens M. Predictors of smoking cessation in adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1998;152:388–393. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, O.O.A.S. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings, Rep. No. NSDUH Series H-30, DHHS Publication No. SMA 06−4194. Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S. Effects of sixty-six adolescent tobacco use cessation trials and seventeen prospective studies of self-initiated quitting. Tob. Induced Dis. 2002;1:35–81. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-1-1-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Severson H, Burton D, Flay BR. Self-initiated quitting among adolescent smokers. Prev. Med. 1998;27:19–28. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman SY. Developing School-based Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation Programs. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Rippens PD. Predicting natural resolution of alcohol-related problems: a prospective behavioral economic analysis. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:248–257. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS. Smoking cessation during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2002;4:321–332. doi: 10.1080/14622200210142698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas SL, Pederson LL. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. BMJ. 1998;7:409. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. A comparison of four self-report smoking cessation outcome measures. Addict. Behav. 2004;29:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI. The association of current smoking behavior with the smoking behavior of parents, siblings, friends and spouses. Addiction. 2003a;98:923–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Willemsen G, Engels R, Boomsma DI. Smoking status of parents, siblings and friends: predictors of regular smoking? Findings from a longitudinal twin-family study. Twin Res. 2003b;6:209–217. doi: 10.1375/136905203765693861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MQ, Fitzhugh EC, Green BL, Turner LW, Eddy JM, Westerfield RC. Prospective social–psychological factors of adolescent smoking progression. J. Adolesc. Health. 1999;24:2–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, McGregor H, Borrelli B, Jordan PJ, Strecher VJ. Measuring tobacco dependence treatment outcomes: a perspective from the behavior change consortium. Ann. Behav. Med. 2005;29:11–19. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Sun J, Billings SC, Choi WS, Malarcher A. Predictors of smoking cessation in US adolescents. A.J. Prev. Med. 1999;16:202–207. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]