Abstract

At present, a number of transfection techniques are available to introduce foreign DNA into cells, but still minimal intrusion or interference with normal cell physiology, low toxicity, reproducibility, cost efficiency and successful creation of stable transfectants are highly desirable properties for improved transfection techniques.

For all previous transfection experiments done in our labs, using serum-free cultivated host cell lines, an efficiency value of ∼0.1% for selection of stable cell lines has not been exceeded, consequently we developed and improved a transfection system based on defined liposomes, so-called large unilamellar vesicles, consisting of different lipid compositions to facilitate clone selection and increase the probability for creation of recombinant high-production clones. DNA and DOTAP/DOPE or CHEMS/DOPE interact by electrostatic means forming so-called lipoplexes (Even-Chen and Barenholz 2000) and the lipofection efficiency of those lipoplexes has been determined via confocal microscopy.

In addition, the expression of the EGFP was determined by FACS to investigate transient as well as stable transfection and the transfection efficiency of a selection of different commercially available transfection reagents and kits has been compared to our tailor-made liposomes.

Keywords: CHO-cells, EGFP, Liposomes, SAXS analysis, Serum-free transfection, Transient transfection

Introduction

Modern mammalian cell culture technology has gained importance based on the constant growing demand for recombinant proteins in technological and clinical application (Muller et al. 2005). For generation of the recombinant protein producing cell lines a broad variety of techniques like calcium phosphate precipitation (Graham and van der Eb 1973; Loyter et al. 1982), liposome fusion (Cudd et al. 1984), retroviruses (Cepko et al. 1984), microinjection (Graessmann and Graessmann 1983), electroporation (Neumann et al. 1982), cationic polymers (Boussif et al. 1995) and protoplast fusion (Schaffner 1980) have been described in literature.

Successful gene expression depends on the prerequisite that intact DNA can cross the endosomal or lysosomal membrane and thus reaches the cytoplasm and finally enters the nucleus (Wattiaux et al. 2000). To avoid lysosomal degradation of the DNA an early escape from this compartment is of primary importance. One option is that the cationic lipids act destabilizing on the lipid bilayer and thus enable the DNA to escape (Wattiaux et al. 1997). Wrobel and et al. were the first to demonstrate the fusion between the cationic liposomes and endocytic vesicles in cell cultures (Wrobel et al. 1995), but still the exact mechanism of the endosomal membrane crossing (Zuhorn et al. 2005) and the DNA transfer across the nuclear membrane remain unresolved (Escriou et al. 2001).

The resulting three-dimensional structures of the lipoplexes represent another crucial parameter after the addition of DNA to the liposomes. Especially the inverted hexagonal phase shows high transfection efficiencies (Boomer and Thompson 1999; Rejman et al. 2005). A close correlation could be found between the occurrence of a lamellar to inverted hexagonal phase transition and the presence of helper lipids like DOPE (Smisterova et al. 2001) which strongly promotes formation of such inverted lipid structures (Lohner 1996). Therefore, cationic lipids in combination with DOPE represent attractive DNA vehicles. However, it was not possible to predict the DNA delivery from the lipoplex structure alone (Zuidam and Barenholz 1998), since a variety of additional parameters e.g. the cell line, plasmid size and DNA property are of equal importance.

Despite different companies, e.g. Avanti Polar Lipids offer transfection kits based on DOTAP/DOPE or premixed compositions, those reagents are more expensive than the crude lipids moreover they have to be extruded and characterized.

Qbiogene has developed a CHO-K1 transfection kit based on DOTAP/DOPE, but the liposome cocktail and the transfection solutions are not chemically defined and the ratio between DOTAP/DOPE is not specified.

The intention was to create a cheap and efficient method that combines a protein-free adapted host cell line with a chemically defined transfection method using an easy detectable model protein to compare transfection efficiencies of different transfection methods.

Thus, we generated tailor-made liposomes consisting of DOTAP/DOPE or CHEMS/DOPE and characterized their structure in a dual way by SAXS (Krishnaswamy et al. 2006) and DLS analysis (Martin et al. 2005). Further we investigated their toxicity and applicability for stable as well as transient transfection experiments. Finally we compared them to a selection of commercially available systems to determine their suitability and potency.

Material and methods

DOTAP was obtained from Merck Eprova AG (Darmstadt, Germany). DOPE was purchased from Lipoid (Ludwigshafen, Germany). CHEMS and genomic calf thymus DNA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Handels GmbH, Vienna, Austria). The fluorescence lipid N-Rh-PE was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). The plasmid pBSKII used for SAXS analysis and pEGFP-N3 used for transfection experiments were purchased from Stratagene (Cedar Creek, TX, USA) and Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, USA).

DNA

Plasmid DNA from transformed E.coli Top10 cells cultivated in 500 mL LB ampicilin medium over night was purified using a Qiagen Maxi-prep kit. Isolated plasmids were stored in water to avoid interactions between buffer salts and cationic liposomes during the lipoplex formation. The plasmid concentration and purity was determined by measuring the absorption at 260 nm spectrophotometrically (Biophotometer, Eppendorf). The A260/A280 ratio was typically between 1.7 and 1.8.

Lipid assembly preparation

Hydrated unilamellar lipid vesicles were prepared from lyophilized lipid mixtures as described (Zuidam and Barenholz 1997). DOTAP/DOPE (Simberg et al. 2001) and CHEMS/DOPE (Slepushkin et al. 1997) were used in 1:1 and 4:6 molar ratios, respectively. About 0.0262 g DOTAP and 0.028 g DOPE were dissolved in 500 μL 96% (v/v) ethanol and incubated for 2 h at 37 ± 2 °C. About 0.0122 g CHEMS and 0.028 g DOPE were dissolved in 500 μL 96% (v/v) ethanol and incubated for 2 h at 55 ± 2 °C. These solutions were injected into 5 mL HBS-buffer (10 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) with a Hamilton syringe to generate liposomes with a concentration of either 7.52 mM DOTAP and 7.52 mM DOPE or 5.02 mM CHEMS and 7.52 mM DOPE in HBS. The produced liposomes had a concentration of 11 mg mL−1 for the DOTAP/DOPE and 12 mg mL−1 for the CHEMS/DOPE preparation. The next day, these liposomes were downsized and homogenized by extrusion through a 100 nm polycarbonate filter membrane by repeated extrusion cycles (10 times). Finally, the extruded liposomes were characterized by DLS analysis using the Malvern Zetasizer Nano to determine the mean diameter and quality of the liposomes. To follow the uptake and internalization of the lipoplexes by CHO-cells, 0.5 mol% N-Rh-PE was added to the lipid solution before injection.

For the SAXS analysis liposome suspensions with a concentration of 100 mg mL−1 were used. For these preparations the tenfold amount of lipid was dissolved in the tenfold volume of ethanol and injected into 50 mL HBS. Afterwards, 30 mL of the preparation were concentrated in a stirred cell 1:10 to a final volume of 3 mL using a 100 kDa regenerated cellulose-membrane, followed by an extrusion step. Finally the liposome quality was determined using DLS analysis with respect to size distribution and homogeneity.

DLS

A Zetasizer Nano NS 3600 (Malvern, UK) was used for DLS analysis to determine the mean diameter and distribution of particle size. The laser within the Zetasizer is a nominal 5 mW Helium Neon continuous power model with a wavelength of 633 nm, whereby the Zetasizer measures the 171° backscatter. To generate significant and reproducible results series of three measurements were performed at 25 ± 2 °C.

SAXS

For the SAXS measurements two different DNA preparations were utilized to determine potential differences between lipoplex associated genomic calf thymus DNA and plasmid DNA. Liposomes and DNA were mixed to generate lipoplexes with a final lipid concentration of 5 mg per 100 μL. Utilized liposome to DNA ratios were 10:1 for pBSKII, 10:1 and 5:1 for genomic DNA.

X-ray scattering experiments were performed on a SWAX camera (HECUS X-ray systems, Graz, Austria) as described previously (Laggner and Mio 1992; Pozo Navas et al. 2005). Ni-filtered Cu Kα-radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm) originating from a sealed-tube X-ray generator (Seifert, Ahrensburg, Germany) with a power of 2 kW. The camera was equipped with a Peltier-controlled variable-temperature cuvette (temperature resolution 0.1 K) and two linear one-dimensional position sensitive detectors OED 50-M (MBraun, Garching, Germany), where q = 4 = 4π sin θ/λ is the scattering vector. Programmable temperature and time controller (HECUS X-ray systems, Graz, Austria) were utilized for temperature control and data acquisition. After equilibrating the samples rested for 10 min at the respective temperature and diffractograms were recorded for 3600 s. Background corrected data were evaluated in terms of a global analysis model that has been reviewed recently (Pabst 2006).

Cell culture

Dihydrofolate-reductase deficient CHO-cells (ATCC; CRL-9096) were used for transient and stable transfection experiments. The cultivation medium consisted of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany) containing 4 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), 0.25% Soya-peptone/UF (HY-SOY/UF Quest International GmbH, Erfstadt-Lechenich, Germany), 0.1% Pluronic-F68 (Sigma-Aldrich Handels GmbH, Vienna, Austria), protein-free supplement (Polymun Scientific, Vienna, Austria) and HT (Hypoxanthine; Thymidine: Sigma-Aldrich Handels GmbH, Vienna, Austria). The cells were cultivated at 37 °C/7% CO2 and split 1:5 twice a week.

Lipoplex preparation and transfection experiments

Liposomes and plasmid were diluted in HBS to a total volume of 100 μL for the formation of lipoplexes. First 11 μg DOTAP/DOPE or 12 μg CHEMS/DOPE and 1 μg pEGFP-N3 were added to HBS and at least incubated at 22 ± 2 °C for 30 min, resulting in the formation of lipoplexes with a molar charge ratio of 2.5:1 (cationic lipid:DNA) (Regelin et al. 2000). About 5 × 105 CHO-cells were seeded into each well of a 12-well plate (Nunc; Amex Export-Import GmbH, Vienna, Austria). The lipoplexes were added to the cells by gentle pipetting and incubated at 37 ± 2 °C for 4 h, before the cultivation medium was exchanged. After 72 h the cells were screened for the EGFP-reporter gene expression by FACS analysis in transient experiments. Viability and cell number were determined via trypan blue vital stain using a Bürker-Türk chamber. During the stable transfection experiments we started selection after 72 h with G418 (cultivation medium +0.5 mg mL−1 G418), expanded the transfectants to T-25 Nunclon delta Flask (Nunc; Amex Export-Import GmbH, Vienna, Austria) and cultivated them for 12 weeks.

Comparison of transfection efficiency

Our cationic liposomal transfection systems were further compared to several commercially available transfection systems like Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen), Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Austria), DMRIE-C reagent (Gibco) and the Nucleofector CHO-cell optimized Kit T with the transfection program H14 (Amaxa). The transfection H14 shows the best ratio between viability and transfection efficiency for CHO dhfr− cells. The transfections with these systems were carried out according to the manufacturers instructions and transient expression of EGFP was analyzed after 72 h.

Microscopic analysis

To analyze the DNA transfer into the nucleus, PicoGreen (Invitrogen) was diluted 1:200 according to the manual in 100 μL TE-buffer (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and mixed 1:1 with either DNA and/or liposomes diluted in 100 μL HBS to a total volume of 200 μL. The benefits of PicoGreen include reduced interference with DNA condensation, a 10-times lower dye concentration compared to propidium iodide or ethidium bromide and no interference with the diffusion coefficient (Hof et al. 2005).

The final transfection cocktail consisting of PicoGreen (λex 488 nm, λem523 nm) stained DNA and N-Rh-PE (λex 550 nm, λem 590 nm) stained liposomes was mixed and incubated for 30 min at 22 ± 2 °C in the dark and finally added to the cells, which were transfected for 4 h at 37 °C/7% CO2. For microscopic analysis 20 μL of the cell suspension was pipetted onto the adhesion slides (Bio-Rad Clin. Div. München-Herkules, CA, USA) and incubated for 10 min at 37 ± 2 °C, washed with PBS and dried. Afterwards, the cells were fixed by incubation with 3% paraformaldehyde (Merck, Germany) for 10 min and washed with PBS. Finally the slides were mounted with Vectashield H1000 (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA 94010) and covered with a cover slip. Confocal slides were prepared 4 and 72 h after transfection. DNA and lipid uptake was visualized on a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope with an Ar-laser (488 nm) and a 63 × water objective in the XYZ mode with 400 Hz.

The Olympus IMT-2 was either used as a light microscope or as an UV microscope. Pictures were taken with an Olympus DP 11 camera 72 h after transfection to determine the EGFP expression.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting

The relative fluorescence units were determined with a FACS-Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA). Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in PBS and 10,000 counts were measured in each sample (λex 488 nm, λem 530 nm). Viable single cells were gated by size (FSC-H) and granularity (SSC) using the Cell Quest Pro software to eliminate dead cells and the cell debris from further analysis. These viable single cells were again gated to determine the EGFP expressing cells. Since FACS-analyses do not result in absolute fluorescence values and we did not use any standard curve, the samples of one experiment were collected and the measured results were immediately compared with similar FACS settings.

Results

Liposome characterization

Liposome preparations were characterized by DLS using the Malvern DTS Zetasizer Nano NS3600 to determine the size-distribution and the quality of the liposomes by PDI and the intercept. The Z-average mean is the average vesicle size in nm. The PDI describes the particle dispersion within the sample. Optimal values are between 0.1–0.3 and indicate a normal size distribution of the liposomes. The intercept is a coefficient for the correctness of a measurement, influenced by the dilution of the sample. Values between 0.95 and 1 indicate a reproducible result, as defined by the protocol. The two liposome preparations used for the transfection experiments were DOTAP/DOPE with a PDI of 0.196 and CHEMS/DOPE with a PDI of 0.099, indicating a proper particle size distribution. The average vesicle size was estimated to be 147 nm for DOTAP/DOPE and 96.6 nm for CHEMS/DOPE. In both cases a high reproducibility of the preparations could be deduced from the intercept value, being 0.96 for the former and 0.94 for the latter. For SAXS analysis separate liposome preparations were produced to gain liposome concentrations of 100 mg mL−1, necessary for SAXS analysis. PDI, Z-average and intercept displayed a homogenous dispersion of vesicles with the expected average size of 120–134 nm similar to the more diluted liposome preparations.

SAXS

For biophysical SAXS analysis, separate liposome-preparations were produced to gain liposome concentrations of 100 mg mL−1. Liposomes composed of DOTAP/DOPE showed a diffuse scattering pattern characteristic for unilamellar vesicles (Pabst et al. 2003). Global data analysis revealed a bilayer thickness of 43 Å. Upon addition of calf thymus DNA to DOTAP/DOPE at a molar lipid to DNA ratio of 10:1, the appearance of a quasi-Bragg peak indicates the formation of multilamellar lipid to DNA stacks with a repeated distance of 66Å, with DNA strands (diameter ∼20 Å) intercalated within the water gaps between the lipid bilayers. At a lipid to calf thymus DNA molar ratio of 5:1, the Bragg peak is more pronounced, indicating an increased correlation of the lipid to DNA stacks. Closer inspection reveals additional intensity around q = 0.15 Å−1 and q = 0.03 Å−1 (Fig. 1) which became more pronounced upon heating up to 65 ± 2 °C. Further, the appearance of additional Bragg peaks suggested the occurrence of a cubic phase. Up to seven orders of diffraction space in the ratio of √2:√3:√4:√6:√8:√9:√10 could be deduced and indexed as (110), (111), (200), (211), (220), (221) and (310) reflections on a three-dimensional cubic phase of space group Pn3m. The reciprocal spacing (s) of cubic phases is related to the lattice spacing (a) by

|

1 |

where h, k, and l are the Miller indices (Seddon 1990). Thus, the lattice spacing can be calculated from the reciprocal gradient of the plot s vs. (h2 + k2 + l2) 1/2. This plot was utilized to calculate a lattice spacing of 13.7 nm for the Pn3m phase. This value is in the same range as reported previously (12.5–14 nm) for PE lipids adopting the Pn3m space group (Gruner et al. 1988). However, besides the Pn3m, remnants of the lamellar phase still were observed. These data strongly suggest that the additional intensity observed at 25 ± 2 °C arises from traces of the cubic phases. In the presence of plasmid DNA, the Bragg peak indicating the formation of lamellar stacks is barely visible, probably due to the lower DNA concentration. In the CHEMS/DOPE mixture, diffuse scattering was observed before and after addition of either calf thymus DNA or plasmid DNA indicating that neither cubic phases nor lamellar stacks were formed in the presence of DNA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Small-angle scattering pattern of DOTAP/DOPE (A), DOTAP/DOPE + genomic calf thymus DNA 10:1 (B), DOTAP/DOPE + genomic calf thymus DNA 5:1 (C), DOTAP/DOPE + genomic calf thymus DNA 5:1 (65 °C ±2) (D) and DOTAP/DOPE + pBSKII 10:1 (E). Data were recorded at 25 ± 2 °C, if not indicated otherwise. Arrows indicate Bragg peaks corresponding to a Pn3m phase. Circle indicates the remnant lamellar phase

Fig. 2.

Small-angle scattering pattern of CHEMS/DOPE (A), CHEMS/DOPE + genomic calf thymus DNA 10:1 (B) and CHEMS/DOPE + pBSKII 10:1 (C). Data were recorded at 25 ± 2 °C

Cellular uptake of lipoplex and EGFP expression

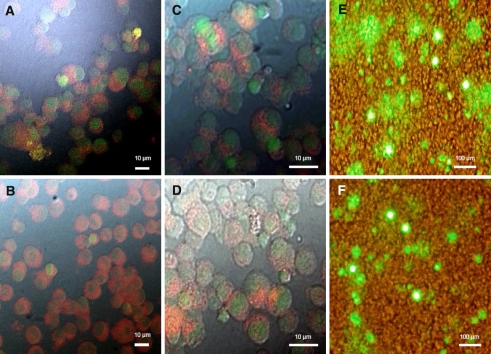

Intracellular location and distribution of the liposomes and DNA after transfection was investigated by rhodamine labeled liposomes and PicoGreen stained DNA in the confocal microscope. Merely, the DNA entered the nucleus while the liposomes stayed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A, B) 4-h post-transfection. After 72 h the lipoplexes were degraded in both transfections (Fig. 3C, D) by the cellular environment indicated by alleviated staining. Panel 3E shows the EGFP expression of the DOTAP/DOPE transfected CHO-cells, while panel 3F shows the reporter gene expression of the CHEMS/DOPE transfected CHO-cells indicating an overall weaker staining compared to the DOTAP/DOPE transfection. Additionally, we quantified all samples at the same time points by FACS. The data revealed a better EGFP expression of DOTAP/DOPE compared to CHEMS/DOPE transfection, confirming our confocal data. Comparison between panel 3A and 3B reveals that DNA transported by DOTAP/DOPE lipoplexes enters the nucleus more efficiently compared to CHEMS/DOPE lipoplexes causing a higher expression of the reporter gene. To ensure PicoGreen does not permeate the cell and the nucleus, negative controls were performed including the addition of free PicoGreen, PicoGreen together with N-Rh-PE labeled liposomes and merely stained liposomes to the cells. The controls showed no staining of cellular DNA, confirming that the fluorescence in Fig. 3A–D resulted from introduced plasmid DNA (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Intracellular uptake and dissociation of lipoplexes consisting of DOTAP/DOPE and CHEMS/DOPE liposomes labeled with N-Rh-PE (red) and PicoGreen stained pEGFP-N3 (green). Transfected cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP2) after 4 h (A, B) and 72 h (C, D). Panels E, F were shot 72-h post-transfection with an UV-microscope. Lipoplexes composed of DOTAP/DOPE/N-Rh-PE (A, C and E) and CHEMS/DOPE/N-Rh-PE (B, D and F). (A, B) The liposomes were located in the cytoplasm while the DNA moved into the nucleus and was visualized by PicoGreen. Panels C & D show alleviated staining of cells after 72 h due to degradation of the lipid/rhodamine complex. Panel E & F show the EGFP expressing cells after 72 h in UV-excitation in parallel with transmitted light to localize the EGFP expressing cells. PicoGreen, cells with PicoGreen and liposomes or cells served as controls (data not shown)

Toxicity

CHO-cells were transfected with increasing amounts of liposomes ranging from 11 to 240 μg depending on the liposome composition and with a constant amount of 1 μg pEGFP-N3. Cell numbers and viability were determined after 48 h using a Bürker-Türk chamber and trypan blue as vital stain (Table 1). Three independent experiments were performed to determine the cytotoxicity of the self-tailored liposomes.

Table 1.

The toxicity of the liposomes was determined by increasing liposome amount

| Liposome composition | Liposome [μg] | Cell number (105cells mL−1)a | SDa | Viability (%)a | SDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTAP/DOPE | 11 | 15.1 | ±4.3 | 96 | ±3.1 |

| DOTAP/DOPE | 110 | 8.4 | ±4.5 | 80 | ±3.4 |

| DOTAP/DOPE | 220 | 1.2 | ±1.1 | 0 | ±0 |

| CHEMS/DOPE | 12 | 10.9 | ±0.86 | 93 | ±0.6 |

| CHEMS/DOPE | 120 | 2.47 | ±0.4 | 6 | ±10.1 |

| CHEMS/DOPE | 240 | 1.71 | ±0.2 | 0 | ±0 |

| Control | – | 13.3 | ±4.3 | 98 | ±3.1 |

The cells were transfected with 1 μg pEGFP-N3 and varying liposome concentration for 4 h. Cell number and viability were detected after 48 h; seeding density was 5 × 105 cells per mL. Mean values and standard deviations were obtained by three different experiments

a48 h post-transfection

Cells transfected with DOTAP/DOPE were able to tolerate 110 μg liposomes while cells exposed to the CHEMS/DOPE formulation died almost completely at 120 μg liposomes after 48 h. Higher liposome concentrations resulted in 100% lethality in both lipid formulations. The measured viabilities declined from 96 via 80 down to 0% for DOTAP/DOPE and 93 via 6 down to 0% for CHEMS/DOPE. These results suggest that both formulations are toxic, but the CHO-cells were able to survive higher amounts of DOTAP/DOPE.

Transfection optimization

To optimize transfection efficiency we varied the DNA (0.2–5 μg) and liposome concentration (2.2–60 μg) in transient transfection experiments. About 2.2, 11 and 55 μg DOTAP/DOPE were combined with 0.2, 1 and 5 μg DNA. FACS analyses were performed to determine the transient EGFP expression after 72 h (Table 2). At each liposome concentration 1 μg DNA generated the highest transfection rates ranging from 12 to 16% positive transfectants after 72 h. Increase from 2.2 to 11 μg DOTAP/DOPE improved the relative number of transfectants by one quarter and showed a fluorescence intensity of 113 rfu, further increase of lipid to 55 and 1 μg DNA per transfection resulted in reduced fluorescence intensity of 24 rfu. Similar results were observed with the highest DNA concentration (5 μg) and 55 μg liposomes resulting in a fluorescence of 31 rfu. The transfection efficiency was not improved upon increase of liposome concentration and the relative fluorescence intensity dropped to approximately 50% of the initial fluorescence units reached with 11 μg. In parallel the viability of all transfections was above 90% indicating that this method is suitable for the generation of stable cell lines. All transfections with CHEMS/DOPE showed poor transfection efficiencies at low percentage range with only about one fifth of fluorescence intensity (data not shown). However, cellular viability as well as cell concentration was not distinguished. Therefore, we decided to test both liposome preparations in stable clone development.

Table 2.

Optimization of the transfection approaches by varying the amount of DNA and liposomes

| DNA (μg) | DOTAP/DOPE (μg) | Transfectants (%)a | Fluorescence (relative units)a | Cell number (1 × 105cells mL−1)a | Viability (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 2.2 | 0 | 31 | 9.84 | 96 |

| 1 | 12 | 138 | 7.8 | 93 | |

| 5 | 2 | 103 | 1.18 | 92 | |

| 0.2 | 11 | 1 | 28 | 6.66 | 97 |

| 1 | 16 | 113 | 6.42 | 98 | |

| 5 | 4 | 126 | 10.2 | 91 | |

| 0.2 | 55 | 2 | 19 | 5.3 | 99 |

| 1 | 14 | 24 | 6.48 | 98 | |

| 5 | 16 | 31 | 8.04 | 91 | |

| – | 11 | 0 | 16 | 12.5 | 96 |

Ascending DNA concentrations (0.2, 1 and 5 μg) were mixed with different DOTAP/DOPE concentrations ranging from 2.2 to 55 μg. As negative control cells were merely incubated with DOTAP/DOPE. Seeding density was 5 × 105 cells per mL

a72-h post-transfection

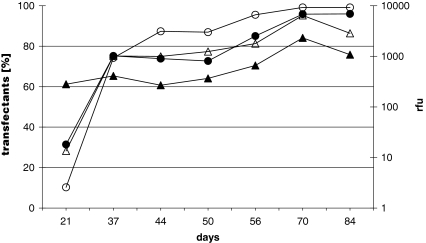

Stable transfection

The process of generating stable recombinant cell lines with DOTAP/DOPE or CHEMS/DOPE was investigated by transfecting CHO-cells and long time cultivation of the cells in selective medium. The percentage of transfected cells was routinely determined every second to third passage using FACS analysis (Fig. 4) and EGFP expression intensity was quantified by the rfu. In both experiments cell numbers increased from 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells per mL after two weeks of cultivation in G418. In contrast to transient experiments, transfection with CHEMS/DOPE showed similar results like DOTAP/DOPE. After 37 days of transfection a homogenous cell population could be selected consisting of 75% EGFP expressing cells in the population. The number of positive transfectants increased continuously until a homogenous population was established 70 days after transfection. Furthermore, the EGFP expression rate increased continuously during the selection process. As already shown during transient transfection, the initial efficiency of CHEMS/DOPE was lower but stable clones reached similar expression titers indicated by the rfu (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Stable transfection experiments along with the tailor-made liposomes. CHO-cells were either transfected with 11 μg DOTAP/DOPE or with 12 μg CHEMS/DOPE. Selection started 24 h after transfection with G418. EGFP expressing cells were quantified at the indicated days post-transfection by detecting the percentage of positive cells (% transfectants) and the relative expression titer indicated by the rfu. (-•-) [%] DOTAP/DOPE transfectants, (-○-) [%] CHEMS/DOPE transfectants, (-▴-) fluorescent DOTAP/DOPE transfected cells and (-▵-) fluorescent CHEMS/DOPE transfected cells

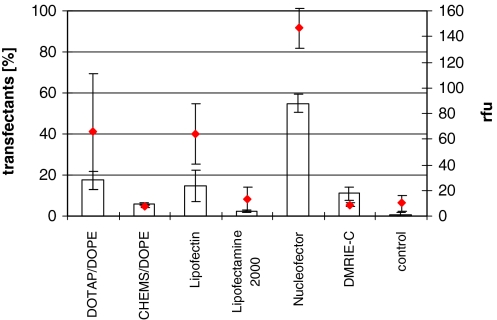

Comparison of different transfection methods

To evaluate different transfection methods regarding their potential for transient protein expression we compared several commercially available products (lipofectin, lipofectamin 2000, DMRIE-C reagent and the nucleofector) with our tailor-made liposomes (Fig. 5). The nucleofector kit showed the highest transient transfection efficiency with 55% EGFP positive transfectants and 147 rfu. CHEMS/DOPE and lipofectamin 2000 showed the lowest with 6 and 2% positive cells. DMRIE-C showed a solid performance of 11%, but a low fluorescence of 9 rfu, whereas DOTAP/DOPE and lipofectin transfected 18 and 15% of the cells with nearly the same fluorescence of 66 and 64 rfu, respectively. Viability of all cell populations was acceptable with values above 90%. However, the nucleofector transfected cells showed a rather coarse structure correlating with cell death, resulting in a viability of 80% after 24 h and 85% after 72 h (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the transient transfection efficiencies of six methods. The CHO-cells were transfected according to the manual and cultivated in 12-well plates. Bars indicate the standard deviation derived from three independent experiments, columns are the positive transfectants [%] and diamonds (-(- -)-) are relative fluorescence

-)-) are relative fluorescence

Discussion

We generated DOTAP/DOPE and CHEMS/DOPE liposomes and characterized them by DLS and SAXS analysis. The appearance of a quasi-Bragg peak indicates the formation of lamellar DOTAP/DOPE lipoplex stacks. Upon heating to 65 ± 2 °C, a Pn3m was formed, while still remnants of the lamellar phase were present. Consequently we suggest that the additional intensity observed at 25 ± 2 °C results from traces of the cubic phase. Our resulting observation is in disagreement with the data described by Simberg and co-workers suggesting DOTAP/DOPE liposome composition to form HII phases (Simberg et al. 2001). The CHEMS/DOPE liposomes neither formed Pn3m nor lamellar stacks in the presence of DNA (Fig. 2). Thus, it is plausible that the transfection mode of these vesicular structures differs from the DOTAP/DOPE lipoplex stacks due to the propensity of the latter system to form non-lamellar structures. Such Pn3m can be intermediate structures between a lamellar to inverse hexagonal phase transition (Seddon 1990) and thus enhance membrane fusion (Siegel and Epand 1997), which is described to play an essential role in the transfection mechanism of DOTAP/DOPE liposomes (Boomer and Thompson 1999; Rejman et al. 2005).

To follow the fate of lipoplexes within the cell we incorporated N-Rh-PE into the liposomes, labeled the plasmid DNA with PicoGreen and transfected CHO-cells with these lipoplexes. Via rhodamine stained cells confocal microscopy revealed the internalization of the complexes 4-h post-transfection (Fig.3A, B) and the DNA could be visualized in the nucleus with PicoGreen. In case of CHEMS/DOPE at least part of the rhodamine stained cells did not show any PicoGreen signal while the cytoplasmic rhodamine staining has been found weaker and nuclear PicoGreen staining was increased in DOTAP/DOPE transfected cells. Thus, we assume that the initial uptake of the lipoplex presents a prerequisite, but the expression rate of the transgen is determined by the optimal DNA uptake into the nucleus reflected by much higher relative fluorescence of DOTAP/DOPE transfectants (Figs. 3 and 5). The exclusion of the liposomes from the nucleus is another necessity for efficient expression (Xu and Szoka 1996). This is supported by Zabner et al. (1995), who observed very low expression rates when the lipoplexes were microinjected into the nucleus directly.

In a different experiment we tested the influence of the lipid concentration in the transfection cocktail. The increase of liposomes resulted in a reduced viability of the cells (Table 1) but did not correlate with transfection efficiency (Table 2) despite positively charged lipoplexes enable efficient binding to the cell surface (Scarzello et al. 2005), an overload of lipoplexes enhances the cell-toxicity (Templeton et al. 1997). EGFP expression was merely driven by total DNA uptake (Farhood et al. 1995). Best results were generated by transfection with 1 μg pEGFP-N3 independent of the liposome concentration. Further increase of plasmid DNA did not improve the transfection efficiency (Table 2). Comparison of transient transfection with stable clone development showed that the selection of high production clones does not correlate with the initial transfection efficiency in case of intracellular EGFP expression. Despite transient DOTAP/DOPE expression resulted in two to three fold higher transfection efficiencies, CHEMS/DOPE transfectants behaved similar after three weeks regarding EGFP productivity and clone homogeneity. The percentage of transfectants and the expression titers converged in both clones selected during time progression and resulted in homogenous recombinant cell populations with slightly higher expression rates of CHEMS/DOPE transfectants 84 days after transfection (Fig.4).

For the evaluation of the potency of various transfection techniques, four commercial systems were selected and compared with DOTAP/DOPE and CHEMS/DOPE. Lipofectin (DOTMA/DOPE), DMRIE-C and DOTAP/DOPE belong to the family of cationic lipids that release the associated DNA into the cytoplasm by membrane destabilization. The transfection data were evaluated via an one-way ANOVA along with post-hoc differences calculated with Tuckey honest significant difference test. Transient transfection experiments employing Lipofectin, DMRIE-C and DOTAP/DOPE showed similar transfection efficiencies, according to the statistical evaluation with no significant differences detectable. CHEMS/DOPE showed a reduced transfection rate of cells during transient transfection in contrast to the nucleofector kit providing 55% transiently transfected cells after 72 h. The nucleofector kit showed a significant difference (p < 0.001) with respect to the number of transfectants and fluorescence intensity. This might be ascribed to the direct DNA delivery into the nucleus predicted by the supplier. However, the lack of information about the transfection cocktail makes it difficult to generate defined stable production cell lines. Furthermore, the nucleofector bears the disadvantages of significantly reduced cell viability of 60–80% compared to the lipofections (data not shown) with viabilities above 90%, the limited scalability as well as the high cell concentrations necessary for transfection.

Efficient transient gene expression gains increasing importance to accumulate adequate amounts of recombinant protein for research purpose and preclinical studies in a short time schedule. Therefore further studies concerning our lipoplexes in this protein-free system will focus on the expression of secreted recombinant proteins in transient approaches. The next step will be to evaluate the suitability of our liposomes for transient transfection in different host systems since the amount of expressed recombinant protein mainly depends on maximal cell density and viability of the culture in an extended batch.

As a conclusion our chemically defined liposomes are adaptable for transient large-scale production since the costs of the transfection cocktail is one to two orders of magnitude cheaper than commercial DNA vehicles. Further the toxicity is lower compared to lipofectin, nucleofector, lipofectamin 2000 and DMRIE-C.

Among a set of different parameters like vesicle size, mixing rate, order of addition, ionic strength of the mixing buffer and lipid to DNA charge ratio represent quite a few parameters affecting lipoplex characteristics (Zuhorn and Hoekstra 2002). Furthermore, the high variability in lipid composition leaves room for the improvement of transfection efficiency of the tailored liposomes, which may be greatly enhanced upon understanding of the details of the molecular mechanism of this process.

We already started the optimization of transfection protocols for protein-free adapted host cell lines a couple of years ago mainly using lipofection and the Amaxa nucleofector. These methods enabled us to isolate recombinant clones with different transfection efficiency and quality. Besides, we tested the self made DOTAP/DOPE lipoplexes for stable transfection and antibody expression. In a series of experiments carried out with the same monoclonal antibody and identical expression plasmids our tailor-made liposomes reduced the number of required transfections. We had to screen less growing wells for generation of suitable stable clones and selection was much faster. The transfection efficiency was more reproducible and primary transfectants were easier to select and adapt to MTX pressure with an outcome of more IgG producing clones.

Acknowledgement

This research was part of the Pharma-Planta Project (LSHB-CT-2003–503565), kindly funded by an EU FP6 program.

Abbreviations

- a.u.

Arbitrary units

- CHEMS

Cholesteryl hemisuccinate

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- DLS

Dynamic light scattering

- DOPE

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- DOTAP

1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane

- DOTMA

N-(1–2,3-Dioleyloxypropyl)-N,N,N-triethylammonium

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescence protein

- FACS

Fluorescence activated cell sorter

- HII phase

Inverted hexagonal phases

- HBS

Hepes buffered saline

- N-Rh-PE

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PDI

Polydispersity index

- Pn3m

Cubic phase

- rfu

Relative fluorescence units

- SAXS

Small angle X-ray scattering

- LB

Luria Bertani

- LUV

Large unilamellar vesicles

Contributor Information

Hannes Reisinger, Phone: +43-1-360066805, FAX: +43-1-3697615, Email: hannes.reisinger@boku.ac.at.

Hermann Katinger, Phone: +43-1-360066203, FAX: +43-1-3697615, Email: office@polymun.com.

References

- Boomer JA, Thompson DH (1999) Synthesis of acid-labile diplasmenyl lipids for drug and gene delivery applications. Chem Phys Lipids 99:145–153 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boussif O, Lezoualch F, Zanta MA, Mergny MD, Scherman D, Demeneix B, Behr JP (1995) A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:7297–7301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cepko CL, Roberts BE, Mulligan RC (1984) Construction and applications of a highly transmissible murine retrovirus shuttle vector. Cell 37:1053–1062 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cudd A, Labbe H, Gervais M, Nicolau C (1984) Liposomes injected intravenously into mice associate with liver mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 774:169–180 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Escriou V, Carriere M, Bussone F, Wils P, Scherman D (2001) Critical assessment of the nuclear import of plasmid during cationic lipid-mediated gene transfer. J Gene Med 3:179–187 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Even-Chen S, Barenholz Y (2000) DOTAP cationic liposomes prefer relaxed over supercoiled plasmids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1509:176–188 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Farhood H, Serbina N, Huang L (1995) The role of dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine in cationic liposome mediated gene transfer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1235:289–295 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Graessmann M, Graessmann A (1983) Microinjection of tissue culture cells. Methods Enzymol 101:482–492 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Graham FL, van der Eb AJ (1973) A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology 52:456–467 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gruner SM, Tate MW, Kirk GL, So PT, Turner DC, Keane DT, Tilcock CP, Cullis PR (1988) X-ray diffraction study of the polymorphic behavior of N-methylated dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine. Biochemistry 27:2853–2866 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hof M, Kral T, Langner M, Adjimatera N, Blagbrough IS (2005) DNA condensation characterized by Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS). Cell Mol Biol Lett 10:23–25 [PubMed]

- Krishnaswamy R, Pabst G, Rappolt M, Raghunathan VA, Sood AK (2006) Structure of DNA-CTAB-hexanol complexes. Phys. Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 73(031904) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laggner P, Mio H (1992) SWAX—a dual-detector camera for simultaneous small- and wide-angle X-ray diffraction in polymer and liquid crystal research. Nucl Instr Meth Phys Res A323:86–90 [DOI]

- Lohner K (1996) Is the high propensity of ethanolamine plasmalogens to form non-lamellar lipid structures manifested in the properties of biomembranes? Chem Phys Lipids 81:167–184 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Loyter A, Scangos GA, Ruddle FH (1982) Mechanisms of DNA uptake by mammalian cells: fate of exogenously added DNA monitored by the use of fluorescent dyes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:422–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martin B, Sainlos M, Aissaoui A, Oudrhiri N, Hauchecorne M, Vigneron JP, Lehn JM, Lehn P (2005) The design of cationic lipids for gene delivery. Curr Pharm Des 11:375–394 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Muller N, Girard P, Hacker DL, Jordan M, Wurm FM (2005) Orbital shaker technology for the cultivation of mammalian cells in suspension. Biotechnol Bioeng 89:400–406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Neumann E, Schaefer-Ridder M, Wang Y, Hofschneider PH (1982) Gene transfer into mouse lyoma cells by electroporation in high electric fields. Embo J 1:841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pabst G (2006) Global properties of biomimetic membranes: prespectives on molecular features. Biophys Rev Lett 1:57–84 [DOI]

- Pabst G, Koschuch R, Pozo-Navas B, Rappolt M, Lohner K, Laggner P (2003) Structural analysis of weakly ordered membrane stacks. J Appl Cryst 36:1378–1388 [DOI]

- Pozo Navas B, Lohner K, Deutsch G, Sevcsik E, Riske KA, Dimova R, Garidel P, Pabst G (2005) Composition dependence of vesicle morphology and mixing properties in a bacterial model membrane system. Biochim Biophys Acta 1716:40–48 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Regelin AE, Fankhaenel S, Gurtesch L, Prinz C, von Kiedrowski G, Massing U (2000) Biophysical and lipofection studies of DOTAP analogs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1464:151–164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rejman J, Bragonzi A, Conese M (2005) Role of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis in gene transfer mediated by lipo- and polyplexes. Mol Ther 12:468–474 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scarzello M, Smisterova J, Wagenaar A, Stuart MC, Hoekstra D, Engberts JB, Hulst R (2005) Sunfish cationic amphiphiles: toward an adaptative lipoplex morphology. J Am Chem Soc 127:10420–10429 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schaffner W (1980) Direct transfer of cloned genes from bacteria to mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77:2163–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Seddon JM (1990) Structure of the inverted hexagonal (HII) phase, and non-lamellar phase transitions of lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1031:1–69 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Siegel DP, Epand RM (1997) The mechanism of lamellar-to-inverted hexagonal phase transitions in phosphatidylethanolamine: implications for membrane fusion mechanisms. Biophys J 73:3089–3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Slepushkin VA, Simões S, Dazin P, Newman MS, Guo LS, Pedroso de Lima MC, Düzgünes N (1997) Sterically stabilized pH-sensitive liposomes. Intracellular delivery of aqueous contents and prolonged circulation in vivo. J Biol Chem 272:2382–2388 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Simberg D, Danino D, Talmon Y, Minsky A, Ferrari ME, Wheeler CJ, Barenholz Y (2001) Phase behavior, DNA ordering, and size instability of cationic lipoplexes. Relevance to optimal transfection activity. J Biol Chem 276:47453–47459 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smisterova J, Wagenaar A, Stuart MC, Polushkin E, ten Brinke G, Hulst R, Engberts JB, Hoekstra D (2001) Molecular shape of the cationic lipid controls the structure of cationic lipid/dioleylphosphatidylethanolamine-DNA complexes and the efficiency of gene delivery. J Biol Chem 276:47615–47622 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Templeton NS, Lasic DD, Frederik PM, Strey HH, Roberts DD, Pavlakis GN (1997) Improved DNA: liposome complexes for increased systemic delivery and gene expression. Nat Biotechnol 15:647–652 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wattiaux R, Jadot M, Warnier-Pirotte MT, Wattiaux-De Coninck S (1997) Cationic lipids destabilize lysosomal membrane in vitro. FEBS Lett 417:199–202 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wattiaux R, Laurent N, Wattiaux-De Coninck S, Jadot M (2000) Endosomes, lysosomes: their implication in gene transfer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 41:201–208 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wrobel I, Collins D (1995) Fusion of cationic liposomes with mammalian cells occurs after endocytosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1235:296–304 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Szoka FC, Jr. (1996) Mechanism of DNA release from cationic liposome/DNA complexes used in cell transfection. Biochemistry 35:5616–5623 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zabner J, Fasbender AJ, Moninger T, Poellinger KA, Welsh MJ (1995) Cellular and molecular barriers to gene transfer by a cationic lipid. J Biol Chem 270:18997–19007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zuhorn IS, Bakowsky U, Polushkin E, Visser WH, Stuart MC, Engberts JB, Hoekstra D (2005) Nonbilayer phase of lipoplex-membrane mixture determines endosomal escape of genetic cargo and transfection efficiency. Mol Ther 11:801–810 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D (2002) On the mechanism of cationic amphiphile-mediated transfection. To fuse or not to fuse: is that the question? J Membr Biol 189:167–179 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zuidam NJ, Barenholz Y (1997) Electrostatic parameters of cationic liposomes commonly used for gene delivery as determined by 4-heptadecyl-7-hydroxycoumarin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1329:211–222 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zuidam NJ, Barenholz Y (1998) Electrostatic and structural properties of complexes involving plasmid DNA and cationic lipids commonly used for gene delivery. Biochim Biophys Acta 1368:115–128 [DOI] [PubMed]