Abstract

Optimal steroid hormone biosynthesis occurs via the integration of multiple regulatory processes, one of which entails a coordinate increase in the transcription of all genes required for steroidogenesis. In the human adrenal cortex adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) activates a signaling cascade that promotes the dynamic assembly of protein complexes on the promoters of steroidogenic genes. For CYP17, multiple transcription factors, including steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1), GATA-6, and sterol regulatory binding protein 1 (SREBP1), are recruited to the promoter during activated transcription. The ability of these factors to increase CYP17 mRNA expression requires the formation of higher order coregulatory complexes, many of which contain enzymatic activities that post-translationally modify both the transcription factors and histones. We discuss the mechanisms by which transcription factors and coregulatory proteins regulate CYP17 transcription and summarize the role of kinases, phosphatases, acetyltransferases, and histone deacetylases in controlling CYP17 mRNA expression.

Keywords: CYP17, p54nrb, GCN5, SRC-1, cAMP, Steroidogenic factor-1

1. Introduction

In the human adrenal cortex, glucocorticoids and adrenal androgens are synthesized in response to the trophic hormone adrenocorticotropin (ACTH). ACTH directs increased steroid hormone secretion by regulating multiple cellular processes, including substrate import, trafficking, and delivery, transcriptional activation, pyridine nucleotide metabolism, and electron transfer (Miller, 2005, 2007; Sewer et al., 2007; Stocco et al., 2005). One of the intracellular second messengers that mediates the adrenocortical response to ACTH is cAMP. cAMP, via activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) evokes rapid changes in the availability of free cholesterol and also acts to coordinately increase the transcription of all genes required for steroid hormone biosynthesis. These genes include adrenodoxin, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and members of the cytochromes P450 superfamily of monooxygenases. This review will briefly summarize factors that regulate the transcription of CYP17, the gene that encodes P450c17.

2. CYP17

P450c17 is a bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the 17α-hydroxylation of pregnenolone and progesterone for cortisol production and performs a 17, 20 bond scission reaction that results in adrenal androgen biosynthesis. CYP17 (and thus P450c17) is predominantly expressed in the adrenal gland, testicular Leydig cells, and ovarian thecal cells. However, expression has been detected in rat gastrointestinal tract (Dalla Valle et al., 1995; Le Goascogne et al., 1995), brain (Compagnone et al., 2000; Hojo et al., 2004), and liver (Vianello et al., 1997), in zebrafish brain, liver, and intestine (Wang and Ge, 2004), and in avian (Matsunaga et al., 2001) and frog (Do Rego et al., 2007) brain. It has been suggested that expression of CYP17 in the embryonic rodent central nervous system indicates that the enzyme plays a key role in providing androgens for sensory-motor function (Compagnone et al., 1995).

In the adult human adrenal cortex, selective expression of CYP17 in the zona fasciculata and zona reticularis, but not in the zona glomerulosa permits zone-specific production of steroid hormones. In fact, cAMP-dependent transcription of CYP17 is negatively regulated by agents that increase aldosterone production (Bird et al., 1996) and is unresponsive to nuclear receptors that increase the transcription of CYP11B2 and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (Bassett et al., 2004a,b,c). The ability of P450c17 to differentially carry out 17α-hydroxylase versus 17,20 lyase reactions is regulated by protein–protein interactions (Auchus et al., 1998; Geller et al., 1999) and post-translational modification (Pandey et al., 2003; Tee et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 1995). Therefore, in addition to 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, the expression and specific enzymatic reaction catalyzed by P450c17 determines functional zonation of the two inner zones of the adult adrenal cortex. Finally, the importance of CYP17 is evidenced by the embryonic lethal phenotype of 127/SvJ mice null for the enzyme (Bair and Mellon, 2004). In contrast, targeted disruption of CYP17 in C57BL/6 mice resulted in male infertility due to androgen imbalance (Liu et al., 2005).

3. Regulation by transcription factors

As mentioned above, like the vast majority of genes involved in adrenal steroidogenesis, the transcription of CYP17 is increased in response to ACTH signaling. Several DNA-binding proteins have been found to be important in conferring increased CYP17 gene expression. Some of these factors act to ensure basal transcription, while others act in response to activation of the ACTH signaling pathway.

3.1. Steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1)

SF-1 is a nuclear receptor that is essential not only for increased steroidogenic gene expression (including CYP17), but also for development and sex determination, as germ line disruption of the receptor results in postnatal lethality and male–female sex reversal (Luo et al., 1994). Recently, several elegant studies using mice generated to ablate SF-1 expression in a tissue-specific manner have revealed novel roles for the receptor in modulating neural function. Conditional knockout of SF-1 in the central nervous system increases anxiety-like behavior (Zhao et al., 2008) and mice lacking expression of the receptor in the anterior pituitary display hypogonadotropism (Zhao et al., 2001a,b). Additionally, SF-1 has been recently found to regulate the expression of the cannabinoid receptor 1 in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (Kim et al., 2008) and has been implicated in regulating energy homeostasis (Bingham et al., 2008; Dhillon et al., 2006). Collectively, these studies have expanded the role for SF-1 as a regulator of varied physiological processes.

Initial studies using reporter gene constructs to define ACTH-dependent transcription of the human CYP17 gene identified that the first 63 base pairs upstream of the transcription initiation site are required for cAMP-stimulated gene expression (Rodriguez et al., 1997). It was subsequently shown that activation of the ACTH signaling pathway promoted the binding of SF-1 to this region (Sewer et al., 2002). cAMP stimulation resulted in the assembly of a complex containing SF-1, the RNA and DNA-binding protein p54nrb, and the polypyrimidine-tract-binding protein associated factor (PSF) on the promoter (Sewer et al., 2002). Notably, the affinity of this complex for the human CYP17 promoter was found to be regulated by phosphatase activity (Sewer and Waterman, 2002). Although SF-1 is integral for activating the transcription of the CYP17 gene in other species (Zhang and Mellon, 1996), studies characterizing the bovine gene have demonstrated that in adrenocortical cells SF-1 acts in a reciprocal manner with chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor I which, when bound, represses CYP17 transcription (Bakke and Lund, 1995a).

It has become evident that post-translational modifications play a central role in controlling the transactivation potential of SF-1. In murine Y1 cells, SF-1 is phosphorylated at Ser-203 in response to epidermal growth factor signaling by extracellular related kinase (Hammer et al., 1999). Analyses of kinases that target Ser-203 have recently identified that cyclin-dependent kinase 7 phosphorylates this residue (Lewis et al., 2008). We have recently found that cAMP signaling increases phosphorylation of SF-1 in human H295R cells in a manner that requires glycogen synthase kinase 3β (Dammer et al., unpublished results). SF-1 is also acetylated (Chen et al., 2005; Ishihara and Morohashi, 2005; Jacob et al., 2001) and SUMOylated (Chen et al., 2004; Komatsu et al., 2004), adding to the complexity of post-translational mechanisms that control receptor function.

The ability of SF-1 to activate the transcription of human CYP17 is also regulated by ligand binding. Using mass spectrometry to identify ligands for SF-1, we found that sphingosine bound to the endogenous receptor and antagonized transactivation of CYP17 (Urs et al., 2006). In response to cAMP, sphingosine dissociates from the receptor, concomitant with phosphatidic acid binding and subsequent receptor activation (Li et al., 2007). These findings are supported by crystallographic studies carried out by three independent laboratories have found that the bacterially expressed receptor binds various phosphoplipids (Ingraham and Redinbo, 2005; Krylova et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). Moreover, given the large binding pocket (1600 Å3), it is likely that different sphingolipid and phospholipid species will be found to act as antagonists and agonists in specific tissues and/or in response to activation of varied signaling pathways.

3.2. GATA

Another family of transcription factors that regulates CYP17 transcription in the human adrenal cortex is the GATA family of transcription factors. These DNA-binding proteins control gene expression, cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis in diverse cell types, including the gonads and adrenal gland (Parviainen et al., 2007; Shimizu and Yamamoto, 2005; Tong et al., 2003; Tremblay and Viger, 2003; Viger et al., 2004). GATA-6 is highly expressed in the adrenal cortex, primarily in the zona reticularis of adults (Kiiveri et al., 2002). A role for GATA-6 in regulating the transcription of CYP17 in the H295R human adrenocortical cell line has been established, where synergy between GATA-6 and SF-1 directs adrenal androgen biosynthesis (Jimenez et al., 2003). Interestingly, the expression of GATA-6 is positively regulated by cAMP (Kiiveri et al., 2004), suggesting a role for trophic hormone stimulation in fine-tuning the function of this transcription factor in steroidogenic tissues. Complex formation between GATA-6 or GATA-4 and specificity protein (Sp) 1 mediates constitutive expression of CYP17 (Fluck and Miller, 2004). Significantly, the stimulatory actions of GATA-6 on CYP17 transcription are independent of DNA binding, but depend on protein–protein interactions with Sp1 (Fluck and Miller, 2004). GATA-6 also synergizes with SF-1 to regulate the transcription of cytochrome b5 (Huang et al., 2005) and steroid sulfotransferase 2A1 (Saner et al., 2005) in the human adrenal, further supporting the role of this transcription factor in adrenal development and steroidogenesis.

3.3. Sp1 and Sp3

In addition to associating with GATA proteins (Fluck and Miller, 2004), Sp1 and Sp3 also interact with nuclear factor 1 to control basal expression of CYP17 (Lin et al., 2001). Sp proteins were once thought of as transcription factors that controlled the expression of housekeeping genes, however emerging evidence supports roles for these proteins in regulating transcriptional responses to cell signaling (Li et al., 2004; Wierstra, 2008). Sp1 and Sp3 interact with numerous nuclear receptors to regulate target gene transcription (Safe and Kim, 2004). Intriguingly, both Sp1 and Sp3 can act as transcriptional activators or repressors (Li et al., 2004; Valin and Gill, 2007). Since both proteins are regulated by phosphorylation (Chu and Ferro, 2005) and SUMOylation (Valin and Gill, 2007), it is likely that activated intracellular signaling results in the concurrent post-translational modification of multiple transcription factors that control CYP17 gene expression.

3.4. Sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)

Another transcription factor that regulates the expression of the human CYP17 gene is sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) (Ozbay et al., 2006). SREBPs are transcription factors that not only function as cholesterol sensors (Horton et al., 2002), but also regulate the transcription of steroidogenic genes, including steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (Shea-Eaton et al., 2001). We have shown that in response to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), SREBP1c is cleaved and transported to the nucleus where it activates CYP17 transcription (Ozbay et al., 2006). Interestingly, activation of the ACTH signaling cascade promotes the rapid metabolism of complex sphingolipid species and promotes the secretion of S1P into the cell culture media (Ozbay et al., 2004; Ozbay et al., 2006). Since S1P is a ligand for a family of G-protein coupled receptors (Lee et al., 1998; Spiegel and Milstien, 2002; van Brocklyn et al., 1998, 2000), increased release of this bioactive lipid into extracellular space provides evidence for ACTH-induced paracrine signaling. Of note, given that we have recently found that S1P promotes migration of H295R adrenocortical cells and increases the trafficking of mitochondria (Li and Sewer, unpublished observations), it is probable that S1P will be found to regulate steroidogenesis and adrenal function by multiple mechanisms.

4. Regulation by coregulators

The ability of transcription factors to regulate the expression of target genes is controlled by complex formation with coregulatory proteins. Coregulators act to repress or activate target gene transcription by facilitating transcription factors to adopt either an active (mediated by coactivators) or inactive (corepressor-dependent) conformation (Lonard et al., 2007; Perissi and Rosenfeld, 2005). In general, agonist binding to a nuclear receptor induces a conformational change that increases the receptor’s ability to bind to coactivator proteins that contain Leu-x-x-Leu-Leu motifs (also called nuclear receptor boxes) (Ding et al., 1998; Heery et al., 1997; McInerney et al., 1998). Interestingly, nuclear receptor boxes are required for the interaction between diacylglycerol kinase theta, the enzyme that produces phosphatidic acid, and SF-1 (Li et al., 2007). These findings indicate that the protein machinery required for agonist synthesis forms a complex with the receptor, thus maximizing efficient ligand binding.

Many of these coactivator proteins harbor innate catalytic properties, such as lysine acetyltransferase and arginine methyl-transferase activities. Collectively, the goal of coactivator proteins is to establish a transcriptionally competent environment at the promoter of the target gene. This is achieved by post-translationally modifying histones and transcription factors, displacing nucleosomes, and providing interaction domains for RNA polymerase II and the general transcriptional machinery. In contrast, when a nuclear receptor, such as SF-1, is unliganded or occupied by antagonist (e.g. sphingosine), the activation function 2 domain interacts more favorably with proteins that contain a CoRNR (corepressor nuclear receptor) box motif (Hu et al., 2001). CoRNR boxes are typically found on nuclear receptor corepressors such as N-CoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) and SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor) (Hu and Lazar, 1999; Li et al., 1997). Indeed, sphingosine represses CYP17 transcription by promoting the interaction between SF-1 and SMRT (Urs et al., 2006).

Using temporal chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) in synchronized H295R cells, we have characterized the components of the protein complexes that associate with the CYP17 promoter during cAMP-stimulated transcriptional activation (Dammer et al., 2007). Like temporal ChIP studies carried out to interrogate other genes (Metivier et al., 2003; Winnay and Hammer, 2006), our experiments have revealed that complexes containing corepressors or coactivators are reciprocally recruited to the promoter (Dammer et al., 2007). Moreover, within 60 min after cAMP treatment, a complex containing steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1), general control nonderepressed 5 (GCN5), and SF-1 forms on the CYP17 promoter. Given that GCN5 is a histone acetytransferase that has been shown to acetylate SF-1 (Jacob et al., 2001), it is possible that formation of this trimer facilitates the acetylation of SF-1 and proximally localized histones. An increase in acetylated histone H4 at the 60-min time point supports a role for GCN5 in modifying adjacent nucleosomes (Dammer et al., 2007). Interestingly, we have data that suggests a role for acetylation of SF-1 in controlling ligand binding to the receptor (Dammer et al., unpublished observations). Dissociation of the SF-1/SRC1/GCN5 trimer is closely followed by recruitment of histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1 and the corepressors RIP140 (receptor interacting protein 140) and Sin3A. These findings confirm previous studies demonstrating that Sin3A represses CYP17 transcription (Sewer et al., 2002). Another important event that occur in response to cAMP stimulation is the recruitment of ATPase-containing chromatin remodeling complexes, which coincides with the rapid loss of histone H2 from nucleosomes within this region of the CYP17 promoter (Dammer et al., 2007).

Because our initial characterization of factors interacting with the CYP17 promoter identified p54nrb and PSF as members of a complex with SF-1 (Sewer et al., 2002), we also assessed the kinetics of binding of these two proteins to the promoter and found that in contrast to SF-1/GCN5/SRC1 trimer that forms early in transcriptional cycling, p54nrb and PSF are enriched at the promoter at a later time point (Dammer et al., 2007). At this later time point (180 min post-cAMP stimulation), SF-1 and RNA polymerase II re-associate with the promoter, thus enabling a second cycle of transcription. p54nrb is a multi-functional protein that contains both RNA (Peng et al., 2002) and DNA-binding domains (Yang et al., 1993), as well as motifs that facilitate interaction with proteins such as the spliceosome (Kameoka et al., 2004) and RNA polymerase II (Emili et al., 2002). p54nrb also promotes the binding of transcription factors to their cognate response elements (Yang et al., 1997) and regulates the transactivation potential of several nuclear receptors (Amelio et al., 2007; Fox et al., 2005). The presence of diverse functional domains in p54nrb has led to the hypothesis that the protein plays an integral role in coupling transcription and pre-mRNA splicing (Emili et al., 2002; Kameoka et al., 2004; Liang and Lutz, 2006). Of note, we have recently found that p54nrb binds to CYP17 pre-mRNA and to spliceosome proteins (Jagarlapudi and Sewer, unpublished observations). Further, the ability of p54nrb to differentially interact with nucleic acids and proteins is regulated by phosphorylation (Jagarlapudi and Sewer, unpublished observations).

Another important event in cAMP-dependent transcription of the CYP17 promoter is the association of carboxy terminal binding proteins (CtBPs) (Dammer et al., 2007). The enrichment of CtBPs at the promoter corresponds with the exchange of transcriptional activators for repressors. CtBP corepressors were initially identified and characterized based on their ability to suppress transformation by the E1A viral oncoprotein (Schaeper et al., 1995). It was subsequently found that CtBP corepressors bind to and are regulated by NADH (Kumar et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002). We have recently shown that ACTH signaling rapidly promotes the metabolism of pyridine nucleotides in H295R adrenocortical cells and that this change in the nuclear ratio of NADH/NAD+ regulates the ability of CtBPs to repress CYP17 transcription (Dammer and Sewer, 2008). These studies also demonstrated that PKA phosphorylates CtBPs and that phosphorylation regulates their dimerization and nuclear localization (Dammer and Sewer, 2008). In addition to defining the mechanism by which CtBPs repress CYP17 transcription, this work identified a role for ACTH in regulating pyridine nucleotide metabolism and provided support for the coupling of transcription to metabolism.

5. Summary

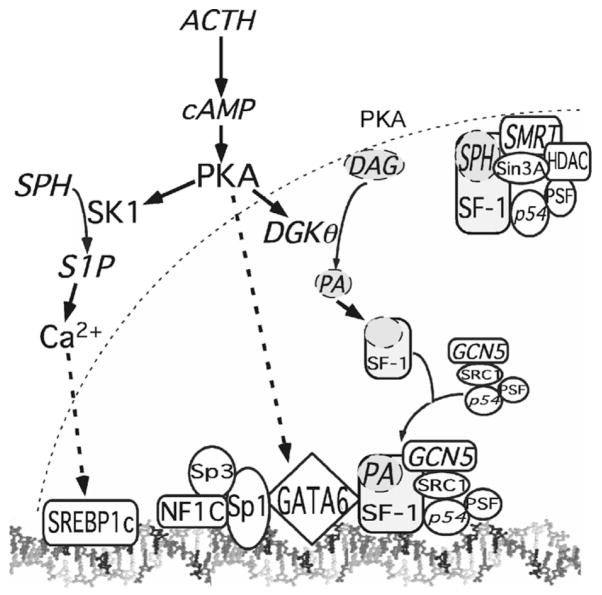

This brief review summarizes some of the proteins that regulate CYP17 transcription by associating with the promoter. As shown in Fig. 1, some of these proteins bind directly to DNA (e.g. SF-1), while others modulate CYP17 gene expression by forming higher order protein complexes. Additionally, it is clear that post-translational modification of nucleosomes, transcription factors, and coregulators modulate transcriptional potential during ACTH/cAMP signaling. Future studies are likely to uncover additional facets to the complex regulatory pathways involved in controlling CYP17 expression in the human adrenal cortex.

Fig. 1.

Model for transcriptional regulation of human CYP17. In response to ACTH, PKA activation stimulates multiple proteins, including SK1 (sphingosine kinase 1), DGKθ (diaclyglycerol kinase theta). It is likely that PKA modulates the activity of several other proteins in adrenocortical cells. Activated DGKθ phosphorylates diacylglycerol (DAG) to form phosphatidic acid (PA). Increased nuclear concentrations of PA facilitate dissociation of sphingosine (SPH) and corepressor proteins [Sin3A, histone deacetylase (HDAC), silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors (SMRT)]. Binding of PA to steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) promotes the assembly of a transcription activator complex containing SRC1 (steroid receptor coactivator 1), the histone acetyltransferase GCN5 (general control nonderepressed 5), p54, and polypyrimidine-tract binding protein-associated splicing factor (PSF). PKA also activates SK1, which converts SPH to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). S1P activates the cleavage and nuclear import of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) via a Ca2+-dependent pathway. Constitutive CYP17 expression is mediated by a complex containing specificity protein (Sp) 1, Sp3, and nuclear factor 1C (NF1C). Basal transcription is also mediated by GATA-6, which binds to Sp1. In response to cAMP GATA-6 synergizes with SF-1 to activate CYP17 transcription.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant GM073241.

Footnotes

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited.

References

- Amelio AL, Miraglia LJ, Conkright JJ, Mercer BA, Batalov S, Cavett V, Orth AP, Busby J, Hogenesch JB, Conkright MD. A coactivator trap identifies NONO (p54nrb) as a component of the cAMP-signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:20314–20319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707999105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchus RJ, Lee TC, Miller WL. Cytochrome b5 augments the 17,20 lyase activity of human P450c17 without direct electron transfer. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3158–3165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair SR, Mellon SH. Deletion of the mouse P450c17 gene causes early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5383–5390. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5383-5390.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke M, Lund J. Mutually exclusive interactions of two nuclear orphan receptors determine activity of a cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-responsive sequence in the bovine CYP17 gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1995a;9:327–339. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.3.7776979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MH, Suzuki T, Sasano H, De Vries CJ, Jimenez PT, Carr BR, Rainey WE. The orphan nuclear receptor NGFIB regulates transcription of 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Implications for the control of adrenal functional zonation. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:37622–37630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MH, Suzuki T, Sasano H, White PC, Rainey WE. The orphan nuclear receptors NURR1 and NGFIB regulate adrenal aldosterone production. Mol Endocrinol. 2004b;18:279–290. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MH, White PC, Rainey WE. A role for the NGFI-B family in adrenal zonation and adrenocortical disease. Endocr Res. 2004c;30:567–574. doi: 10.1081/erc-200043715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham NC, Anderson KK, Reuter AL, Stallings NR, Parker KL. Selective loss of leptin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus results in increased adiposity and a metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2138–2148. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird IM, Pasquarette MM, Rainey WE, Mason JI. Differential control of 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase expression in human adrenocortical H295R cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2171–2180. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.6.8964847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Lee WC, Hsu NS, Huang F, Chung BC. SUMO modification of repression domains modulates function of the nuclear receptor 5A1 (steroidogenic factor-1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38730–38735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Juan LJ, Chung BC. SF-1 (nuclear receptor 5A1) activity is activated by cyclic AMP via p300-mediated recruitment to active foci, acetylation, and increased DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10442–10453. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10442-10453.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S, Ferro TJ. Sp1: regulation of gene expression by phosphorylation. Gene. 2005;348:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone NA, Bulfone A, Rubenstein JL, Mellon SH. Steroidogenic enzyme P450c17 is expressed in the embryonic central nervous system. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5212–5223. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone NA, Zhang P, Vigne JL, Mellon SH. Novel role for the nuclear phosphoprotein SET in transcriptional activation of P450c17 and initiation of neurosteroidogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:875–888. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.6.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Valle L, Couet J, Larbrie Y, Simard J, Belvedere P, Simontacchi C, Labrie F, Colombo L. Occurrence of cytochrome P450c17 mRNA and dehydroepiandrosterone biosynthesis in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;111:83–92. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03553-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammer EB, Leon A, Sewer MB. Coregulator exchange and sphingosine-sensitive cooperativity of steroidogenic factor-1, general control nonderepressed 5, p54, and p160 coactivators regulate cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent cytochrome p450c17 transcription rate. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:415–438. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammer EB, Sewer MB. Phosphorylation of CtBP1 by PKA modulates induction of CYP17 by stimulating partnering of CtBP1 and 2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6925–6934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708432200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Ye C, Lee CE, McGovern RA, Tang V, Kenny CD, Christiansen LM, White RD, Edelstein EA, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Cowley MA, Chua SC, Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin directly activates SF-1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;49:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XF, Anderson CM, Ma H, Hong H, Uht RM, Kushner PJ, Stallcup MR. Nuclear receptor-binding sites of coactivators glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1): multiple motifs with different binding specificities. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:302–313. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.2.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Rego JL, Tremblay Y, Luu-The V, Repetto E, Castel H, Vallarino M, Bélanger A, Pelletier G, Vaudry H. Immunohistochemical localization and biological activity of the steroidogenic enzyme cytochrome P450 17 alpha-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase (P450c17) in the frog brain and pituitary. J Neurochem. 2007;100:251–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emili A, Shales M, McCracken S, Xie W, Tucker PW, Kobayashi R, Blencowe BJ, Ingles CJ. Splicing and transcription-associated proteins PSF and p54nrb/NonO bind to the RNA polymerase II CTD. RNA. 2002;8:1102–1111. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202025037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluck CE, Miller WL. GATA-4 and GATA-6 modulate tissue-specific transcription of the human gene for P450c17 by direct interaction with Sp1. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1144–1157. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AH, Bond CS, Lamond AI. p54nrb forms a heterodimer with PSP1 that localizes to paraspeckles in an RNA-dependent manner. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5304–5315. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DH, Auchus RJ, Miller WL. P450c17 mutations R347H and R358Q selectively disrupt 17,20 lyase activity by disrupting interactions with P450 oxidoreductase and cytochrome b5. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:167–175. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.1.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer GD, Krylova I, Zhang Y, Darimont BD, Simpson K, Weigel NL, Ingraham HA. Phosphorylation of the nuclear receptor SF-1 modulates cofactor recruitment: integration of hormone signaling in reproduction and stress. Mol Cell. 1999;3:521–526. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80480-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoarce S, Parker MG. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 1997;387:733–736. doi: 10.1038/42750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo Y, Hattori TA, Enami T, Furukawa A, Suzuki K, Ishii HT, Mukai H, Morrison JH, Janssen WG, Kominami S, Harada N, Kimoto T, Kawato S. Adult male rat hippocampus synthesizes estradiol from pregnenolone by cytochromes P450 17alpha and P450 aromatase localized in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:865–870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2630225100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Lazar MA. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1999;402:93–96. doi: 10.1038/47069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li Y, Lazar MA. Determinants of CoRNR-dependent repression complex assembly on nuclear hormone receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1747–1758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1747-1758.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N, Dardis A, Miller WL. Regulation of cytochrome b5 gene transcription by Sp3, GATA-6, and steroidogenic factor 1 in human NCI-H295A cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;10:2020–2034. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham HA, Redinbo MR. Orphan nuclear receptors adopted by crystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara SL, Morohashi K. A boundary for histone acetylation allows distinct expression patterns of the Ad4BP/SF-1 and GCNF loci in adrenal cortex cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob AL, Lund J, Martinez P, Hedin L. Acetylation of steroidogenic factor 1 protein regulates its transcriptional activity and recruits the coactivator GCN5. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37659–37664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez P, Saner K, Mayhew B, Rainey WE. GATA-6 is expressed in the human adrenal and regulates transcription of genes required for adrenal androgen biosynthesis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4285–4288. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameoka S, Duque P, Konarska MM. p54(nrb) associates with the 5′ splice site within large transcription/splicing complexes. EMBO J. 2004;23:1782–1791. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiiveri S, Liu J, Westerholm-Ormio M, Narita N, Wilson DB, Voutilainen R, Heikinheimo M. Differential expression of GATA-4 and GATA-6 in fetal and adult mouse and human adrenal tissue. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3136–3143. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiiveri S, Liu J, Keikkila P, Arola J, Lehtonen E, Voutilainen R, Heikinheimo M. Transcription factors GATA-4 and GATA-6 in human adrenocortical tumors. Endocr Res. 2004;30:919–923. doi: 10.1081/erc-200044149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KW, Jo YH, Zhao L, Stallings NA, Chua SC, Jr, Parker KL. Steroidogenic factor 1 regulates expression of the cannabinoid receptor 1 in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1950–1961. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu T, Mizusaki H, Mukai T, Ogawa H, Baba D, Shirakawa M, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama KI, Yamamoto H, Kikuchi A, Morohashi K. Small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1) modification of the synergy control motif of Ad4 binding protein/steroidogenic factor 1 (Ad4BP/SF-1) regulates synergistic transcription between Ad4BP/SF-1 and Sox9. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2451–2462. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylova IN, Sablin EP, Moore J, Xu RX, Waitt GM, MacKay JA, Juzuniene D, Bynum JM, Madauss K, Montana V, Lebedeva L, Suzawa M, Williams JD, Williams SP, Guy RK, Thornton JW, Fletterick RJ, Willson TM, Ingraham HA. Structural analyses reveal phosphatidyl inositols as ligands for the NR5 orphan receptors SF-1 and LRH-1. Cell. 2005;120:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Carlson JE, Ohgi KA, Edwards TA, Rose DW, Escalante CR, Rosenfeld MG, Aggarwal AK. Transcription corepressor CtBP is an NAD+-regulated dehydrogenase. Mol Cell. 2002;10:857–869. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00650-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Goascogne C, Sananes N, Eychenne B, Gouezou M, Baulieu EE, Robel P. Androgen biosynthesis in the stomach: expression of cytochrome P450 17 alpha-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase messenger ribonucleic acid and protein, and metabolism of pregnenolone and progesterone by parietal cells of the rat gastric mucosa. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1744–1752. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.4.7895686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Van Brocklyn JR, Thangada S, Liu CH, Hand AR, Menzeleev R, Spiegel S, Hla T. Sphingosine-1-phosphate as a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-1. Science. 1998;279:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AE, Rusten M, Hoivik EA, Vikse EL, Hansson ML, Wallberg AE, Bakke M. Phosphorylation of steroidogenic factor 1 is mediated by cyclin-dependent kinase 7. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:91–104. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Urs AN, Allegood J, Leon A, Merrill AH, Jr, Sewer MB. cAMP-stimulated interaction between steroidogenic factor-1 and diacylglycerol kinase—facilitates induction of CYP17. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6669–6685. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00355-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Leo C, Schroen DJ, Chen JD. Characterization of receptor interaction and transcriptional repression by the corepressor SMRT. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:2025–2037. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, He S, Sun JM, Davie JR. Gene regulation by Sp1 and Sp3. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:460–471. doi: 10.1139/o04-045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Choi M, Cavey G, Daugherty J, Suino K, Kovach A, Bingham NC, Kliewer SA, Xu HE. Crystallographic identification and functional characterization of phospholipids as ligands for the orphan nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor-1. Mol Cell. 2005;17:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Lutz CS. p54 is a component of the snRNP-free (SF-A) complex that promotes pre-mRNA cleavage during polyadenylation. RNA. 2006;12:111–121. doi: 10.1261/rna.2213506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Martens JWM, Miller WL. NF-1C, Sp1, and Sp3 are essential for transcription of the human gene for P450c17 (steroid 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase) in human adrenal NCI-H295R cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1277–1293. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.8.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yao ZX, Bendavid C, Borgmeyer C, Han Z, Cavalli LR, Chan WY, Folmer J, Zirkin BR, Haddad BR, Gallicano GI, Papadopoulos V. Haploinsufficiency of cytochrome P450 17 alpha-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17) causes infertility in male mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2380–2389. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators and human disease. Endocrine Reviews. 2007;28:575–587. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker KL. A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell. 1994;77:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga M, Ukena K, Tsutsui K. Expression and localization of cytochrome P450 17 alphaα-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase in the avian brain. Brain Res. 2001;899:112–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney EM, Rose DW, Flynn SE, Westin S, Mullen TM, Krones A, Inostroza J, Torchia J, Nolte RT, Assa-Munt N, Milburn MV, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Determinants of coactivator LXXLL motif specificity in nuclear receptor transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3357–3368. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Penot G, Hubner MR, Reid G, Brand H, Kos M, Gannon F. Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell. 2003;115:751–763. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL. Minireview: regulation of steroidogenesis by electron transfer. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2544–2550. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL. StAR search—what we know about how the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein mediates cholesterol import. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:589–601. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay T, Merrill AH, Jr, Sewer MB. ACTH regulates steroidogenic gene expression and cortisol biosynthesis in the human adrenal cortex via sphingolipid metabolism. Endocr Res. 2004;30:787–794. doi: 10.1081/erc-200044040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay T, Rowan Leon A, Patel P, Sewer MB. Cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate-dependent sphingosine-1-phosphate biosynthesis induces human CYP17 gene transcription by activating cleavage of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1427–1437. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AV, Mellon SH, Miller WL. Protein phosphatase 2A and phosphoprotein SET regulate androgen production by P450c17. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2837–2844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parviainen H, Kiiveri S, Bielinsta M, Rahman N, Huhtaniemi IT, Wilson DB, Heikinheimo M. GATA transcription factors in adrenal development and tumors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007:265–266. 17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R, Dye BT, Perez I, Barnard DC, Thompson AB, Patton JG. PSF and p54nrb bind a conserved stem in U5 snRNA. RNA. 2002;8:1334–1347. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202022070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Rosenfeld MG. Controlling nuclear receptors: the circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:542–554. doi: 10.1038/nrm1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez H, Hum DW, Staels B, Miller WL. Transcription of the human genes for cytochrome P450scc and P450c17 is regulated differently in human adrenal NCI-H295 cells than in mouse adrenal Y1 cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:365–371. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S, Kim K. Nuclear receptor-mediated transactivation through interaction with Sp proteins. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2004;77:1–36. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)77001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saner KJ, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Pizzey J, Ho C, Strauss JF, 3rd, Carr BR, Rainey WE. Steroid sulfotransferase 2A1 gene transcription is regulated by steroidogenic factor 1 and GATA-6 in the human adrenal. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:184–197. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeper U, Boyd JM, Verma S, Uhlmann E, Subramanian T, Chinnadurai G. Molecular cloning and characterizaton of a cellular phosphoprotein that interacts with a conserved c-terminal domain of adenovirus E1A involved in negative modulation of oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:10467–10471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewer MB, Huang NguyenV, Tucker CJ, Kagawa PW, Waterman MR. Transcriptional activation of human CYP17 in H295R adrenocortical cells depends on complex formation between p54nrb/NonO, PSF and SF-1, a complex which also participates in repression of transcription. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1280–1290. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewer MB, Waterman MR. ACTH/cAMP-mediated transcription of the human CYP17 gene in the adrenal cortex is dependent on phosphatase activity. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1769–1777. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.5.8820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewer MB, Dammer EB, Jagarlapudi S. Transcriptional regulation of adrenocortical steroidogenic gene expression. Drug Metab Rev. 2007;39:371–388. doi: 10.1080/03602530701498828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea-Eaton Trinidad MJ, Lopez D, Nackley A, McLean MP. Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1a regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1525–1533. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.4.8075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu R, Yamamoto M. Gene expression regulation and domain function of hematopoietic GATA factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel S, Milstien S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate, a key cell signaling molecule. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25851–25854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco D, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR. Multiple signaling pathways regulating steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: more complicated than we thought. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2647–2659. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee MK, Dong Q, Miller WL. Pathways leading to phosphorylation of P450c17 and to the posttranslational regulation of androgen biosynthesis. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2667–2677. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Q, Tsai J, Hotamisligil GS. GATA transcription factors and fat cell formation. Drug News Perspect. 2003;16:585–588. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2003.16.9.829340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay JJ, Viger RS. Novel roles for GATA transcription factors in the regulation of steroidogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;85:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urs AN, Dammer E, Sewer MB. Sphingosine regulates the transcription of CYP17 by binding to steroidogenic factor-1. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5249–5258. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valin A, Gill G. Regulation of the dual-function transcription factor Sp3 by SUMO. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1393–1396. doi: 10.1042/BST0351393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brocklyn JR, Lee MJ, Menzeleev R, Olivera A, Edsall L, Cuvillier O, Thomas DM, Coopman PJ, Thangada S, Liu CH, Hla T, Spiegel S. Dual actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate: extracellular through the Gi-coupled receptor Edg-1 and intracellular to regulate proliferation and survival. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:229–240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brocklyn JR, Graler MH, Bernhardt G, Hobson JP, Lipp M, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-6. Blood. 2000;95:2624–2629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianello S, Waterman MR, Valle LD, Colombo L. Developmentally regulated expression and activity of 17α-hydroxylase/C-17,20-lyase cytochrome P450 in rat liver. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3166–3174. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.8.5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viger RS, Taniguchi H, Robert NM, Tremblay JJ. Role of GATA family of transcription factors in andrology. J Androl. 2004;25:441–452. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Zhang C, Marimuthu A, Krupka HI, Tabrizizad M, Shelloe R, Mehra U, Eng K, Nguyen H, Settachatgul C, Powell B, Milburn MV, West BL. The crystal structures of human steroidogenic factor-1 and liver receptor homologue-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:7505–7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409482102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ge W. Cloning of zebrafish ovarian P450c17 (CYP17, 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase) and characterization of its expression in gonadal and extragonadal tissues. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2004;135:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierstra I. Sp1: emergin roles—beyond constitutive activation of TATA-less housekeeping genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnay JN, Hammer GD. Adrenocorticotropic hormone-mediated signaling cascades coordiate a cyclic pattern of steroidogenic factor 1-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:147–166. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YS, Hanke JH, Carayannopoulos L, Craft CM, Capra JD, Tucker PW. NonO, a Non-POU-Domain-Containing, Octamer-Binding Protein, Is the mammalian homolog of Drosophila nonAdiss. Mol Cell Bio. 1993;13:5593–5603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YS, Yang MCW, Tucker PW, Capra JD. NonO enhances the association of many DNA-binding proteins to their targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2284–2292. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Rodriguez H, Ohno S, Miller WL. Serine phosphorylation of human P450c17 increases lyase activity: implications for adrenarche and for the polycystic ovary syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:10619–10623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Mellon SH. The orphan nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor-1 regulates the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-mediated transcriptional activation of rat cytochrome P450c17 (17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase) Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:147–158. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.2.8825555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Piston DW, Goodman RH. Regulation of corepressor function by nuclear NADH. Science. 2002;295:1895–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.1069300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Bakke M, Krimkevich Y, Cushman LJ, Parlow AF, Camper SA, Parker KL. Hypomorphic phenotype in mice with pituitary-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor 1. Genesis. 2001a;30:65–69. doi: 10.1002/gene.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Bakke M, Parker KL. Pituitary-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001b;185:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Kim KW, Ikeda Y, Anderson KK, Beck L, Chase S, Tobet SA, Parker KL. Central nervous system-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor-1 results in increased anxiety-like behavior. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1403–1415. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]