Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection often is associated with cognitive dysfunction and depression. HCV sequences and replicative forms were detected in autopsy brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid from infected patients, suggesting direct neuroinvasion. However, the phenotype of cells harboring HCV in brain remains unclear. We studied autopsy brain tissue from 12 HCV-infected patients, 6 of whom were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus. Cryostat sections of frontal cortex and subcortical white matter were stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for microglia/macrophages (CD68), oligodendrocytes (2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase), astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP]), and neurons (neuronal-specific nuclear protein); separated by laser capture microscopy (LCM); and tested for the presence of positive- and negative-strand HCV RNA. Sections also were stained with antibodies to viral nonstructural protein 3 (NS3), separated by LCM, and phenotyped by real-time PCR. Finally, sections were double stained with antibodies specific for the cell phenotype and HCV NS3. HCV RNA was detected in CD68-positive cells in eight patients, and negative-strand HCV RNA, which is a viral replicative form, was found in three of these patients. HCV RNA also was found in astrocytes from three patients, but negative-strand RNA was not detected in these cells. In double immunostaining, 83 to 95% of cells positive for HCV NS3 also were CD68 positive, while 4 to 29% were GFAP positive. NS3-positive cells were negative for neuron and oligodendrocyte phenotypic markers. In conclusion, HCV infects brain microglia/macrophages and, to a lesser extent, astrocytes. Our findings could explain the biological basis of neurocognitive abnormalities in HCV infection.

Patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection were reported to be more likely to manifest impairments in the quality of life, fatigue, and depression than patients with liver disease of other etiology (3, 12, 14, 39). More recently, HCV infection was associated with cognitive dysfunction (11, 13). Importantly, Forton and colleagues, using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS), demonstrated elevations of choline/creatine ratios in basal ganglia and white matter in patients with mild hepatitis C disease that were not present in healthy volunteers or patients with hepatitis (9, 11). The presence of similar abnormalities consisting of increased choline and reduced N-acetyl aspartate levels among HCV-positive patients relative to those of controls has since been reported by other researchers (25, 41). The 1H MRS changes in HCV infection are different from those seen in hepatic encephalopathy, where the choline ratios are depressed (40), but are similar to those found in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (24, 26). Additional evidence for the biological basis of HCV-related cognitive dysfunction is provided by a recent report showing differences in gene expression patterns between brain tissue from HCV-positive and HCV-negative patients (1).

Negative effects of HCV on the central nervous system also were reported among HIV-positive patients. Thus, HIV/HCV-coinfected patients were more likely to meet criteria for HIV-associated minor cognitive/motor disorders and HIV-associated dementia complex than HIV-positive, HCV-negative patients despite similar CD4+ and HIV RNA levels in both groups (36). Cherner et al. (6) analyzed 430 participants who were either normal controls or had HCV infection, HIV infection, a history of methamphetamine dependence, or combinations of these factors. Rates of global and domain-specific neuropsychological impairment increased with the number of risk factors, and HCV serostatus was a significant predictor of performance both globally and in the areas of learning, abstraction, and motor skills. In a recent study confined to women, Richardson et al. (35) found that HCV-positive patients were significantly more likely to demonstrate abnormal results of neuropsychological testing, and the combined effect of HCV and HIV was greater than that of either of these infections alone.

Several studies published in recent years suggest that HCV is neuroinvasive. While HCV is primarily a hepatotropic virus, the Flaviviridae family includes a number of well-known neurotropic viruses (e.g., West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, dengue virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus). HCV replicates through an RNA negative-strand intermediate, the presence of which is regarded as direct evidence of replication (16). Negative-strand HCV RNA was found in autopsy brain tissue (34), and two independent groups of researchers reported that the brain-derived HCV variants were more closely related to the virus present in the lymphoid system than to the virus circulating in serum (10, 34). Differences between HCV sequences in the brain and those circulating in plasma also were reported by others (8, 28). Finally, a recent study by Letendre et al. (23) demonstrated the presence of HCV proteins in brain tissue by Western blotting and immunostaining.

However, while there is convincing evidence of HCV neuroinvasion, it is not clear which cells in the brain harbor HCV. The only published study of the subject was limited in its approach to the immunostaining of viral proteins and included only HIV-positive patients (23). In the current study, which employed a multipronged approach consisting of laser capture microscopy (LCM), strand-specific HCV RNA amplification, and immunostaining, we identified CD68+ cells as the dominant brain cell population infected by HCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological samples.

A total of 12 HCV-positive patients who underwent autopsy were available for the study. Six of these patients were coinfected with HIV. The clinical characteristics of all patients, including histopathological data, are presented in Table 1. Since our aim was to determine the phenotype of brain cells harboring HCV, the presence of HCV RNA in brain tissue was confirmed in each case by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Three HCV-negative, HIV-negative cases and two HCV-negative, HIV-positive autopsy cases served as controls. Autopsy samples were provided by The National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium (NNTC), Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (University of Southern California), and Warsaw Medical University (Poland). Brain tissue samples were obtained during routine autopsies conducted within 4 to 27 h after death and stored at −80°C. The analysis was conducted on frontal cortex and subcortical white matter. This study was approved by the respective ethical committees of the involved institutions.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and demographic data on 12 HCV-positive patients and 5 HCV-negative patients from whom autopsy brain tissue was analyzed

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/gendera | Race | HCV statusb | HIV status | Brain pathology | Liver pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35/M | Black | Pos | Pos | Nodular ependymitis, perivascular lymphocytic cuffs | Minimal hepatitis, steatosis |

| 2 | 50/M | White | Pos | Pos | Normal | Cirrhosis |

| 3 | 57/M | White | Pos | Pos | Mild atherosclerosis, mild cerebral atrophy | Cirrhosis |

| 4 | 53/M | White | Pos | Pos | Hydrocephalus | Primary hemochromatosis |

| 5 | 51/M | White | Pos | Pos | Microinfarcts | Cirrhosis |

| 6 | 47/F | White | Pos | Pos | Microinfarcts, menigioma | Bridging fibrosis, hemangioma |

| 7 | 44/M | White | Pos | Neg | Alzheimer type 2, gliosis | Cirrhosis |

| 8 | 46/M | Hispanic | Pos | Neg | Alzheimer type 2, gliosis | Cirrhosis |

| 9 | 54/M | White | Pos | Neg | Alzheimer type 2, gliosis | Cirrhosis |

| 10 | 56/F | White | Pos | Neg | Normal | Cirrhosis |

| 11 | 46/M | White | Pos | Neg | Normal | Cirrhosis |

| 12 | 50/M | White | Pos | Neg | Normal | Steatosis |

| 13 | 52/M | White | Neg | Neg | Normal | Centrilobular necrosis |

| 14 | 54/F | Hispanic | Neg | Neg | Alzheimer type 2, gliosis | Cirrhosis |

| 15 | 40/M | Hispanic | Neg | Neg | Atherosclerosis | Mild steatosis |

| 16 | 48/M | White | Neg | Pos | Intracranial hemorrhage | Mild steatosis |

| 17 | 45/M | White | Neg | Pos | Normal | Normal |

M, male; F, female.

Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

LCM.

Brain tissue samples were cut into 14-μm-thick sections on a cryostat and directly mounted onto UV-irradiated polyethylene naphthalate membrane slides (Zeiss, Bernried, Germany). Slides were kept frozen on dry ice or at −80°C until use, and each cryostat section was stained with an antibody to a different cell type. First, slides were fixed in a mixture of 1:1 acetone:chloroform for 30 s, rinsed briefly in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies specific for macrophages/microglia, neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. The antibodies used were mouse anti-human CD68 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), mouse anti-human neuronal-specific nuclear protein (NeuN; Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse anti-human glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Millipore, Billerica, MA), and mouse anti-human 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase; Millipore, Billerica, MA). In the case of CNPase staining, the slides were incubated in formaldehyde for 10 min before the antibody incubation step. The concentration of antibodies and the duration of incubation were optimized for each tissue sample and ranged between 1:20 and 1:50 and between 20 and 30 min, respectively. To preserve RNA integrity, the staining time was kept to an acceptable minimum. In addition, a separate slide from each sample was incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody against HCV nonstructural protein 3 (NS3; Novocastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom) for 30 min at a 1:20 dilution. Following primary incubation, sections were incubated for 10 min with biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G diluted 1:100 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), followed by 5 min of incubation with avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (Vectastain elite ABC system; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB substrate kit; Vector Laboratories). To confirm the specificity of staining, control experiments included incubation without primary or secondary antibodies. In addition, the specificity of NS3 staining was ensured by testing brain tissue samples from five HCV-negative control subjects, two of whom were HIV positive. All of these control samples were persistently negative for NS3 staining. As an additional precaution, the NS3 staining analysis was repeated on blind-coded samples.

The harvesting of positively stained cells was accomplished using a Palm MicroBEAM system and PalmRoboSofware (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Germany), which allows for the catapulting of selected cells out of the slide section. The following parameters were used: laser beam size, 2.4 μm; pulse energy, 40 to 65 μJ; and the catapult energy was set at 15% above the pulse energy value. From 400 to 650 cells were separated from each slide, and total RNA was extracted using the Picopure isolation kit (Arcturus Bioscience, Sunnyvale, CA).

Detection of HCV RNA.

For the detection of HCV RNA, extracted RNA was incubated for 20 min at 42°C in a 30-μl reaction mixture containing 50 pmol of the antisense primer 5′-TGRTGCACGGTCTACGAGACCTC-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 342 to 320), 1× RT buffer (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD), 5 mmol/liter dithiothreitol, 5 mmol/liter MgCl2, 1 mmol/liter deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 20 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (Gibco). After being heated to 99°C for 10 min, 50 pmol of the sense primer 5′-RAYCACTCCCCTGTGAGGAAC-3′ (nt 35 to 55), 7 μl 10× PCR buffer II (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT), and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer) were added, and the volume was adjusted to 100 μl. The amplification was run in a GeneAmp thermal cycler 9700 (Perkin Elmer) with the following steps: initial denaturing at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 20 cycles of 94°C for 1 min and 58°C for 1 min, and then a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Two microliters of the final product was added directly into the second-round RT-PCR. The latter employed LightCycler FastStart DNA master SYBR green I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and the nested primers 5′-ACTGTCTTCACGCAGAAAGCGTC-3′ (nt 57 to 79) and 5′-CAAGCACCCTATCAGGCAGTACC-3′ (nt 307 to 285). The amplification was run in a LightCycler (Roche) as follows: an initial denaturation and activation of enzyme for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Each amplification was followed by melting-curve analysis to ensure that a single-size product was amplified and no significant primers-dimers were present. In addition, amplification products were run on agarose gels to confirm the correct product size. This assay was capable of detecting approximately 10 genomic equivalent (eq) molecules of the correct template but was not strand specific. Negative controls included brain tissue from uninfected subjects and normal sera.

Detection of negative-strand HCV RNA.

The specificity of our real-time RT-PCR for the detection of negative-strand HCV RNA was ascertained by conducting cDNA synthesis at high temperature with the thermostable enzyme Tth (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A description of the Tth-based assay and its quantitative real-time modification have been published elsewhere (18). This strand-specific assay is capable of detecting approximately 100 viral genomic eq/ml of the correct negative strand while nonspecifically detecting 107 to 108 viral genomic eq/ml of the incorrect positive strand. The sensitivity and specificity of this assay was not affected when up to 0.5 μg of RNA extracted from negative control tissue was added to the reaction mixture.

To allow for viral template quantification, serial dilutions of positive- and negative-strand HCV RNA synthetic template were tested in parallel as previously described (18). In short, to generate positive and negative HCV RNA strands, a PCR product encompassing the 5′-untranslated region was cloned into a plasmid vector (pGEM-3Z; Promega) and, after plasmid linearization, subsequently transcribed with T7 polymerase (Riboprobe Transcription System; Promega). The orientation of the insert was checked by the sequencing of the plasmid directly, and DNA template was removed by digestion with DNase I. The concentration of RNA target copies (in genomic eq) was deduced from A260 readings and the molecular weight of the synthesized transcript. Tenfold serial dilutions of synthetic RNA were tested in parallel with each quantitative RT-PCR run to generate a standard curve, which was used for the calculation of the target genomic eq number.

Determination of cell phenotype by RT-PCR.

For the determination of the cell phenotype by RT-PCR, sections were stained with monoclonal antibodies against NS3 protein and harvested by LCM as described above. After 400 to 650 positive cells were collected, total RNA was extracted with a Picopure isolation kit (Arcturus Bioscience) and split evenly into four different RT-PCRs. Cells were identified by the presence of mRNA transcripts that could be attributed to particular phenotypes. Microglia/macrophages were identified using RT-PCRs specific for the CD68 transcript (sense, 5′ CCTCCTCGCCCTGGTGCTTAT 3′; antisense, 5′ TCTTTGAGCCAGTTGCGTGTC 3′; product size, 158 bp), neurons were identified by the detection of enolase mRNA (sense, 5′ TCCCACTGATCCTTCCCGATA 3′; antisense, 5′ TTCTTCCACTGCCCGCTCAAT 3′; product size, 214 bp), astrocytes were identified by the detection of GFAP mRNA (sense, 5′ CAGTCCTTGACCTGCGACCTG 3′; antisense, 5′ CTGTAGGTGGCGATCTCGATG 3′; product size, 233 bp), and oligodendrocytes were identified by the detection of CNPase mRNA (sense, 5′ GGGAGAGCGAGGCCGAGCAAG 3′; antisense, 5′ CCTAAAGCCGCTGGAACCGAC 3′; product size, 172 bp).

Double immunostaining.

To determine the phenotype of cells containing HCV, 14-μm sections of tissue were directly mounted on glass slides and stained for NS3 protein as described above, with the exception that the incubation time with primary antibodies was extended to 2 h. After positive staining was observed, each section was stained with antibody for a different cell phenotype. For this purpose, the mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies that were used for LCM experiments (anti-CD68, anti-NeuN, anti-GFAP, and anti-GFAP) were directly labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Alexa Fluor 488 monoclonal antibody labeling kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Double immunostained sections were analyzed by alternating between normal and UV light using an Olympus BX51 reflective fluoroscope system. At least 400 HCV NS3-positive cells were analyzed in this fashion for each of the phenotype-specific stains.

RESULTS

Detection of HCV RNA in LCM-fractioned cells.

Autopsy brain tissue samples were stained with monoclonal antibodies against CD68, NeuN, GFAP, and CNPase, and positive cells were separated by LCM (Fig. 1). HCV RNA was detected in the CD68+ cell fraction in 8 of 12 patients, and the viral load ranged from approximately 3 × 103 to 10 genomic eq per 400 to 650 cells (Table 2). Furthermore, the virus negative strand was detected in CD68+ cells in three samples. HCV RNA also was detected in GFAP-positive cells in three patients, but the virus negative strand was not found in these cells. However, considering the low level of HCV RNA positive strands in astrocytes, it is possible that the level of HCV RNA negative strand was below the sensitivity of the strand-specific assay. Neurons and oligodendrocytes were persistently negative for HCV RNA in all patients analyzed. The HCV infection of CD68+ cells was more common in the presence of HIV coinfection, as it was detected in six out of six coinfected patients and in only two out of six HIV-negative patients. This difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06 by Fisher's exact test). The HCV RNA negative strand was found only among HCV/HIV-coinfected patients.

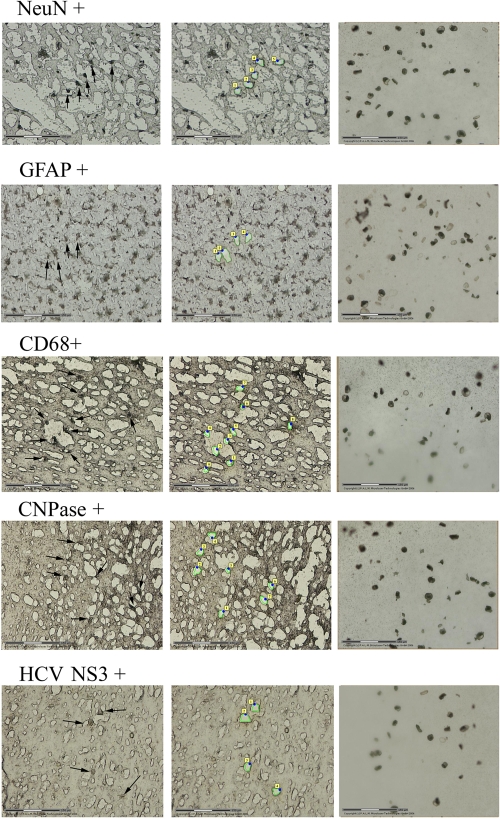

FIG. 1.

LCM separation of macrophages/microglia, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, neurons, and HCV-positive cells from HCV-positive brain tissue. Frontal cortex sections from patient 1 were stained with monoclonal antibodies against CD68, GFAP, CNPase, NeuN, and HCV NS3 protein. First column, stained tissue sections before LCM separation (subsequently separated cells are marked by arrows); middle column, sections after the positively staining cells were removed; last column, LCM-separated cells. The size of the bar corresponds to 150 nm.

TABLE 2.

Quantitative amplification of positive and negative HCV RNA strands in brain cells isolated by LCM from autopsy brain tissuea

| Patient no. | No. of cells positive forb:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD68

|

GFAP

|

NeuN

|

CNPase

|

|||||

| + str | − str | + str | − str | + str | − str | + str | − str | |

| 1 | 3 × 103 | 5 × 102 | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 2 | 2.1 × 103 | 1.2 × 102 | 1.2 × 102 | N | N | N | N | N |

| 3 | 1.7 × 102 | 102 | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 4 | 102 | N | 0.5 × 102 | N | N | N | N | N |

| 5 | 2.2 × 102 | N | 1.8 × 102 | N | N | N | N | N |

| 6 | 1.5 × 102 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 7 | 0.4 × 102 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 8 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 9 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 10 | 10 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 11 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 12 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

A total of 400 to 650 cells were separated from frontal cortex/subcortical white matter.

+ str, HCV RNA positive strand; − str, HCV RNA negative strand; N, negative.

In four patients, HCV RNA was not detected in any cell population, although it could be amplified directly from tissue samples. However, in this test the quantity of RNA used was approximately 1 μg/reaction, whereas 400 to 650 cells captured by LCM provided only 10 to 50 ng of RNA for amplification, as measured by spectrophotometry.

Phenotyping of NS3-positive cells.

Cryostat sections of brain tissue samples were stained with monoclonal antibodies against NS3 viral protein, and cells that were positive were harvested by LCM (Fig. 1, bottom row). Subsequently, these cells were phenotyped by the detection of phenotype-specific mRNAs by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 2E and F and Table 3, the dominant phenotypic marker amplified from NS3-positive cells was CD68.

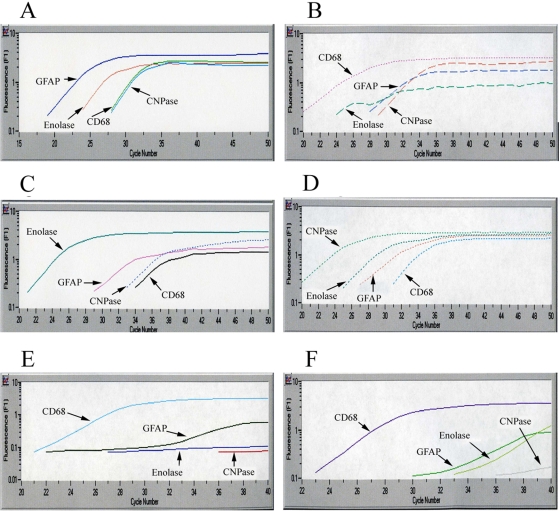

FIG. 2.

Determination of the specificity of real-time RT-PCR for the phenotyping of brain cells (A to D) and determining the phenotype of HCV-infected cells in autopsy brain tissue (E and F). Frontal lobe tissue samples from patient 1 were stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for different cells phenotypes, separated by LCM, and subjected to four different RT-PCRs specific for astrocytes, microglia/macrophages, neurons, and oligodendrocytes. (A) GFAP-positive cells; (B) CD68+ cells; (C) NeuN-positive cells; (D) CNPase-positive cells. (E and F) NS3-positive cells for patients 3 and 4 were separated by LCM and analyzed by phenotype-specific RT-PCR. In both of these cases the CD68 transcript predominated.

TABLE 3.

Identification of the phenotype of HCV NS3-positive cells by real-time PCR and double immunostaining in autopsy brain tissue samples from 12 HCV-infected patientsa

| Patient no. | Dominant cell-identifying transcript | % Positive by immunostaining for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD68 | GFAP | NeuN | CNPase | ||

| 1 | CD68+ | 86 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | CD68+ | 95 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | CD68+ | 90 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | CD68+ | 83 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | CD68+ | 80 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | CD68+ | 95 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | CD68+ | 92 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | CD68+ | 90 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | CD68+ | 90 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | CD68+ | 86 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | CD68+ | 85 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | CD68+ | 93 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

All five HCV-negative control patients, two of whom were HIV positive, were negative for NS3 staining.

However, cells of any particular phenotype, when separated by LCM, are likely to be contaminated by other cells, even when using thin tissue sections and a narrow laser beam. To determine the scale of the contamination problem, brain tissue cryostat sections were stained with monoclonal antibodies against CD68, NeuN, GFAP, and CNPase, separated by LCM, and phenotyped by real-time RT-PCR. As seen in Fig. 2A to D, the phenotypic signature of contaminating cells was approximately ≥2 logs weaker than the signal from the major cells. Thus, although present, inadvertent cell contamination during LCM is unlikely to have a major influence on results.

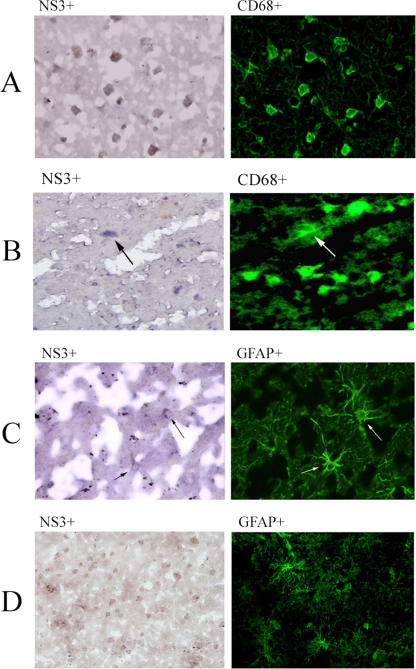

Double staining for NS3 and cell phenotype.

Tissue sections were indirectly stained for NS3 protein, followed by direct staining with phenotype-specific monoclonal antibodies. The results were in agreement with those of previous two approaches, as between 80 and 95% of NS3-positive cells also were CD68 positive, while 4 to 29% were positive for GFAP (Table 3). Double staining for NS3 and NeuN or CNPase was not observed. An example of a positive double stain for NS3 and CD68 is shown in Fig. 3A, while a positive double stain for NS3 and GFAP is shown in Fig. 3B. Figure 3C shows that the majority of NS3-positive cells did not stain with anti-GFAP and therefore were not astrocytes.

FIG. 3.

Double immunocytochemical analysis of HCV-positive brains for markers of HCV infection and astrocytes and the macrophage/microglia phenotype. Frontal cortex sections from patient 3 were stained with monoclonal antibodies against HCV NS3 protein and against CD68 or GFAP. NS3 staining was visualized with DAB under normal light (first column), while phenotyping monoclonal antibodies were directly conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and visualized under UV light (second column). (A) Staining with anti-NS3 and anti-CD68 FITC-conjugated antibodies in an area in which virtually all NS3-positive cells also are CD68-positive (magnification, ×400). (B) The same staining in a different area, where most CD68-positive cells are NS3 negative. (C) Staining with anti-NS3 and anti-GFAP conjugated with FITC; arrows mark two cells that are positive for both markers (magnification, ×400). (D) The same stain in a different region; the NS3-positive cells all are negative for GFAP staining (magnification, ×200).

DISCUSSION

In the current study conducted on autopsy brain tissue, we identified brain cells harboring HCV infection as being mainly CD68+ cells (macrophages/microglia) and, to a lesser extent, astrocytes. The phenotype of HCV-positive cells was identical in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. The specific sites of HCV infection were established by three independent approaches: the detection of positive and negative HCV RNA in LCM-isolated cells, the phenotyping of HCV NS3-positive cells, and the double staining of cells for viral and phenotype-specific markers. In the only other report devoted to the phenotyping of HCV-infected brain cells, Letendre et al. (23) identified astrocytes as the principal site of HCV infection, while macrophage/microglia were considered a less robust infection site. Thus, there is a degree of congruence between the results of our study and those published by Letendre et al., the only difference being the perceived dominant infected cell population. This discrepancy could be due to the use of a different population of patients and also to different antibodies used for the immunostaining of viral proteins. Accordingly, Letendre et al. (23) used polyclonal antibody against NS5A protein in their double immunocytochemical analysis to determine the cellular localization of HCV, whereas we used monoclonal antibodies against NS3 protein.

However, it should be emphasized that in addition to immunostaining, in our study the presence of virus in particular cells was confirmed by the demonstration of HCV RNA and occasionally by the detection of viral replicative forms.

The HCV infection of brain CD68+ cells (microglia/macrophages) is not unexpected. HCV is becoming recognized as being lymphotrophic; several groups of researchers have detected viral replicative forms in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and it also was demonstrated that viral genomic sequences present in PBMCs may differ from those found in serum and the liver (20-22, 29). HCV RNA also has been detected in PBMCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells by in situ hybridization (37). Importantly, the same minor variants of HCV strain H77, which were selected in lymphoblastoid cells in vitro, were found to be replicating in vivo in the PBMCs of chimpanzees inoculated with the same parental strain (38). Within the population of PBMCs, the cells harboring replicating virus have been identified as monocytes/macrophages and B cells, although T cells can be infected as well, particularly in long-lasting infection (2, 7, 19). Native human macrophages also are susceptible to HCV infection in vitro, as demonstrated by the detection of HCV RNA, viral replicative forms, and positive immunostaining for viral proteins (5, 33). Such infection may be consequential: in one study, the exposure of primary macrophages to HCV-positive serum resulted in the enhanced production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-8 (IL-8) and their respective mRNAs (33).

Infected leukocytes could provide access for HCV into the central nervous system (the Trojan horse phenomenon). This hypothetical scenario, which is similar to that postulated for HIV type 1 (HIV-1) infection (31, 43), is supported by studies showing a close relationship between HCV sequences found in the brain and/or cerebrospinal fluid and sequences found in PBMCs and lymph nodes (10, 17, 34). Infected macrophages and microglial cells could release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-1, and IL-6, neurotoxins such as nitric oxide, and viral proteins, which could induce changes in brain function that in turn lead to neurocognitive dysfunction and depression (4, 42). HCV infection also may be associated with oxidative stress, which could be due to the release of reactive oxygen species by macrophages or to the direct effect of viral proteins on mitochondria (27, 30). Similar mechanisms may be operational in HIV-1 infection (15, 32).

However, despite some similarities, there is a fundamental difference between HIV-1 and HCV infections, as the latter does not progress into AIDS-type dementia. This could be due to the fact that HCV replication in macrophages is at a low level and is confined to a limited number of cells. It also is possible that the infection is not productive, infecting virions are not generated, or the local spread of infection is limited.

In summary, we provide evidence that in HCV-positive patients, CD68+ cells (brain macrophages and microglia) and, to a lesser extent, astrocytes harbor HCV. These findings could relate directly to the common presence of neurocognitive dysfunction among chronic hepatitis C patients and could explain the negative effects of HCV in HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 1R21 MH073422 from the National Institute of Mental Health. M.R. is supported by grant 0548/PO5/2005/28 from the Polish Ministry of Science.

We thank the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium (supported by NIH grant N01MH32002) and the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (Carol Miller, University of Southern California; supported by NIH grant 5P50AG005142) for providing the samples for the study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 November 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adair, D. M., M. Radkowski, J. Jablonska, A. Pawelczyk, J. Wilkinson, J. Rakela, and T. Laskus. 2005. Differential display analysis of gene expression in brains from hepatitis C-infected patients. AIDS 19(Suppl. 3)S145-S150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain, C., A. Fatmi, F. Zoulim, J. P. Zarski, C. Trepo, and G. Inchauspe. 2001. Impaired allostimulatory function of dendritic cells in chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology 120512-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkhuizen, A., H. R. Rosen, S. Wolf, K. Flora, K. Benner, and R. M. Bennett. 1999. Musculoskeletal pain and fatigue are associated with chronic hepatitis C: a report of 239 hepatology clinic patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 941355-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capuron, L., and R. Dantzer. 2003. Cytokines and depression: the need for a new paradigm. Brain Behav. Immun. 17(Suppl. 1)S119-S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caussin-Schwemling, C., C. Schmitt, and F. Stoll-Keller. 2001. Study of the infection of human blood derived monocyte/macrophages with hepatitis C virus in vitro. J. Med. Virol. 6514-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherner, M., S. Letendre, R. K. Heaton, J. Durelle, J. Marquie-Beck, B. Gragg, and I. Grant. 2005. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology 641343-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducoulombier, D., A. M. Roque-Afonso, G. Di Liberto, F. Penin, R. Kara, Y. Richard, E. Dussaix, and C. Feray. 2004. Frequent compartmentalization of hepatitis C virus variants in circulating B cells and monocytes. Hepatology 39817-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishman, S. L., J. M. Murray, F. J. Eng, J. L. Walewski, S. Morgello, and A. D. Branch. 2008. Molecular and bioinformatic evidence of hepatitis C virus evolution in brain. J. Infect. Dis. 197597-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forton, D. M., J. M. Allsop, J. Main, G. R. Foster, H. C. Thomas, and S. D. Taylor-Robinson. 2001. Evidence for a cerebral effect of the hepatitis C virus. Lancet 35838-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forton, D. M., P. Karayiannis, N. Mahmud, S. D. Taylor-Robinson, and H. C. Thomas. 2004. Identification of unique hepatitis C virus quasispecies in the central nervous system and comparative analysis of internal translational efficiency of brain, liver, and serum variants. J. Virol. 785170-5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forton, D. M., H. C. Thomas, C. A. Murphy, J. M. Allsop, G. R. Foster, J. Main, K. A. Wesnes, and S. D. Taylor-Robinson. 2002. Hepatitis C and cognitive impairment in a cohort of patients with mild liver disease. Hepatology 35433-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster, G. R. 1999. Hepatitis C virus infection: quality of life and side effects of treatment. J. Hepatol. 31250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilsabeck, R. C., W. Perry, and T. I. Hassanein. 2002. Neuropsychological impairment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 35440-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenny-Walsh, E., et al. 1999. Clinical outcomes after hepatitis C infection from contaminated anti-D immune globulin. N. Engl. J. Med. 3401228-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolson, D. L., E. Lavi, and F. Gonzalez-Scarano. 1998. The effects of human immunodeficiency virus in the central nervous system. Adv. Virus Res. 501-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanford, R. E., C. Sureau, J. R. Jacob, R. White, and T. R. Fuerst. 1994. Demonstration of in vitro infection of chimpanzee hepatocytes with hepatitis C virus using strand-specific RT/PCR. Virology 202606-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, A. Bednarska, J. Wilkinson, D. Adair, M. Nowicki, G. B. Nikolopoulou, H. Vargas, and J. Rakela. 2002. Detection and analysis of hepatitis C virus sequences in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Virol. 7610064-10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, J. Jablonska, K. Kibler, J. Wilkinson, D. Adair, and J. Rakela. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus facilitates infection/replication of hepatitis C virus in native human macrophages. Blood 1033854-3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, A. Piasek, M. Nowicki, A. Horban, J. Cianciara, and J. Rakela. 2000. Hepatitis C virus in lymphoid cells of patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence of active replication in monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 181442-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, L. F. Wang, S. J. Jang, H. Vargas, and J. Rakela. 1998. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies in patients infected with HIV-1: correlation with extrahepatic viral replication. Virology 248164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, L. F. Wang, M. Nowicki, and J. Rakela. 2000. Uneven distribution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in tissues from subjects with end-stage liver disease: confounding effect of viral adsorption and mounting evidence for the presence of low-level extrahepatic replication. J. Virol. 741014-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lerat, H., S. Rumin, F. Habersetzer, F. Berby, M. A. Trabaud, C. Trepo, and G. Inchauspe. 1998. In vivo tropism of hepatitis C virus genomic sequences in hematopoietic cells: influence of viral load, viral genotype, and cell phenotype. Blood 913841-3849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letendre, S., A. D. Paulino, E. Rockenstein, A. Adame, L. Crews, M. Cherner, R. Heaton, R. Ellis, I. P. Everall, I. Grant, and E. Masliah. 2007. Pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus coinfection in the brains of patients infected with HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 196361-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcus, C. D., S. D. Taylor-Robinson, J. Sargentoni, J. G. Ainsworth, G. Frize, P. J. Easterbrook, S. Shaunak, and D. J. Bryant. 1998. 1H MR spectroscopy of the brain in HIV-1-seropositive subjects: evidence for diffuse metabolic abnormalities. Metab. Brain Dis. 13123-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAndrews, M. P., K. Farcnik, P. Carlen, A. Damyanovich, M. Mrkonjic, S. Jones, and E. J. Heathcote. 2005. Prevalence and significance of neurocognitive dysfunction in hepatitis C in the absence of correlated risk factors. Hepatology 41801-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyerhoff, D. J., C. Bloomer, V. Cardenas, D. Norman, M. W. Weiner, and G. Fein. 1999. Elevated subcortical choline metabolites in cognitively and clinically asymptomatic HIV+ patients. Neurology 52995-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minagar, A., P. Shapshak, R. Fujimura, R. Ownby, M. Heyes, and C. Eisdorfer. 2002. The role of macrophage/microglia and astrocytes in the pathogenesis of three neurologic disorders: HIV-associated dementia, Alzheimer disease, and multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 20213-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray, J., S. L. Fishman, E. Ryan, F. J. Eng, J. L. Walewski, A. D. Branch, and S. Morgello. 2008. Clinicopathologic correlates of hepatitis C virus in brain: a pilot study. J. Neurovirol. 1417-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navas, S., J. Martin, J. A. Quiroga, I. Castillo, and V. Carreno. 1998. Genetic diversity and tissue compartmentalization of the hepatitis C virus genome in blood mononuclear cells, liver, and serum from chronic hepatitis C patients. J. Virol. 721640-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuda, M., K. Li, M. R. Beard, L. A. Showalter, F. Scholle, S. M. Lemon, and S. A. Weinman. 2002. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastroenterology 122366-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price, R. W., J. Sidtis, and M. Rosenblum. 1988. The AIDS dementia complex: some current questions. Ann. Neurol. 23S27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulliam, L., B. G. Herndier, N. M. Tang, and M. S. McGrath. 1991. Human immunodeficiency virus-infected macrophages produce soluble factors that cause histological and neurochemical alterations in cultured human brains. J. Clin. Investig. 87503-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radkowski, M., A. Bednarska, A. Horban, J. Stanczak, J. Wilkinson, D. M. Adair, M. Nowicki, J. Rakela, and T. Laskus. 2004. Infection of primary human macrophages with hepatitis C virus in vitro: induction of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 8. J. Gen. Virol. 8547-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radkowski, M., J. Wilkinson, M. Nowicki, D. Adair, H. Vargas, C. Ingui, J. Rakela, and T. Laskus. 2002. Search for hepatitis C virus negative-strand RNA sequences and analysis of viral sequences in the central nervous system: evidence of replication. J. Virol. 76600-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson, J. L., M. Nowicki, K. Danley, E. M. Martin, M. H. Cohen, R. Gonzalez, J. Vassileva, and A. M. Levine. 2005. Neuropsychological functioning in a cohort of HIV- and hepatitis C virus-infected women. AIDS 191659-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan, E. L., S. Morgello, K. Isaacs, M. Naseer, and P. Gerits. 2004. Neuropsychiatric impact of hepatitis C on advanced HIV. Neurology 62957-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sansonno, D., A. R. Iacobelli, V. Cornacchiulo, G. Iodice, and F. Dammacco. 1996. Detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) proteins by immunofluorescence and HCV RNA genomic sequences by non-isotopic in situ hybridization in bone marrow and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronically HCV- infected patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 103414-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimizu, Y. K., H. Igarashi, T. Kanematu, K. Fujiwara, D. C. Wong, R. H. Purcell, and H. Yoshikura. 1997. Sequence analysis of the hepatitis C virus genome recovered from serum, liver, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infected chimpanzees. J. Virol. 715769-5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh, N., T. Gayowski, M. M. Wagener, and I. R. Marino. 1999. Quality of life, functional status, and depression in male liver transplant recipients with recurrent viral hepatitis C. Transplantation 6769-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor-Robinson, S. D. 2001. Applications of magnetic resonance spectroscopy to chronic liver disease. Clin. Med. 154-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissenborn, K., J. Krause, M. Bokemeyer, H. Hecker, A. Schuler, J. C. Ennen, B. Ahl, M. P. Manns, and K. W. Boker. 2004. Hepatitis C virus infection affects the brain-evidence from psychometric studies and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Hepatol. 41845-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson, C. J., C. E. Finch, and H. J. Cohen. 2002. Cytokines and cognition—the case for a head-to-toe inflammatory paradigm. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 502041-2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng, J., and H. E. Gendelman. 1997. The HIV-1 associated dementia complex: a metabolic encephalopathy fueled by viral replication in mononuclear phagocytes. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 10319-325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]