Abstract

Objective

Ghrelin, a novel growth-hormone releasing peptide, is implicated to play a protective role in cardiovascular tissues. However, it is not clear whether ghrelin protects vascular tissues from injury secondary to risk factors such as homocysteine (Hcy). The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect and potential mechanisms of ghrelin on Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction.

Methods

Porcine coronary artery rings were incubated for 24 hours with ghrelin (100 ng/mL), Hcy (50 μM), or ghrelin plus Hcy. Endothelial vasomotor function was evaluated using the myograph tension model. The response to thromboxane A2 analog U466419, bradykinin, and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was analyzed. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression was determined using real time PCR and immunohistochemistry staining, and superoxide anion production by lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence analysis. Human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs) were treated with different concentrations of Hcy, ghrelin, and/or anti-ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1a) antibody for 24 hours, eNOS protein levels were determined by western blot analysis.

Results

Maximal contraction with U466419 and endothelium-independent vasorelaxation with SNP were not different among the four groups. However, endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation with bradykinin (10-6M) was significantly reduced by 34% with Hcy compared with controls (P<0.05). Addition of ghrelin to Hcy had a protective effect, with 61.6% relaxation, similar to controls (64.7%). Hcy significantly reduced eNOS expression, while ghrelin co-treatment effectively restored eNOS expression to the control levels. Superoxide anion levels, which were increased by 100% with Hcy, returned to control levels with ghrelin co-treatment. Ghrelin also effectively blocked Hcy-induced decrease of eNOS protein levels in HCAECs in a concentration dependent manner. Anti-ghrelin receptor antibody effectively inhibited ghrelin’s effect.

Conclusions

Ghrelin has a protective effect in the porcine coronary artery by blocking Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction, improving eNOS expression, and reducing oxidative stress. Ghrelin also shows protective effect on HCACEs from Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels. Ghrelin’s effect is receptor-dependent. Thus, ghrelin administration may have beneficial effects in the treatment of vascular disease in hyperhomocysteinemic patients.

Keywords: ghrelin, homocysteine, endothelial dysfunction, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, superoxide anion, oxidative stress, coronary artery

INTRODUCTION

Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid peptide first identified in the rat stomach and reported as an endogenous ligand for growth hormone secretagogue-receptors (GHS-R).1 It primarily functions to stimulate food intake and induce adiposity through growth-hormone-independent mechanisms within the hypothalamus and stomach fundus lining.2 Ghrelin and its receptors have been isolated from various tissues including the stomach, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, blood vessels, and myocardium. Recent studies focused on the cardiovascular system have demonstrated that ghrelin is able to cause vasodilation and increase cardiac index, stroke volume, left ventricular contractility, and left ventricular fractional shortening.3,4 More notably, ghrelin has been implicated in improving endothelial dysfunction, increasing endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression5 and reducing pro-inflammatory reactions in human endothelial cells.6 It is thought that the n-octanoylation at serine-3 is critical for the activity of ghrelin.6,7 Previous studies have demonstrated that deacylated ghrelin (D-ghrelin), unlike the standard form of ghrelin, does not inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)-induced interleukin-8 (IL-8) release.6,7

Cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure affect greater than 70 million Americans and result in nearly 1 million deaths annually.8 The major pathological factor of these diseases is atherosclerotic plaque formation in small and large arteries. It is hypothesized that the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis commences with an inflammatory process resulting in endothelial injury and dysfunction.9 Endothelial injury causes compensatory responses leading to a procoagulant state as well as release of vasoactive molecules and cytokines. The etiology of endothelial injury relates to many factors including hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, and various infectious agents. Elevated homocysteine (Hcy) levels have also proven to be an under-diagnosed cause of endothelial dysfunction. Previous studies by our laboratory have demonstrated that Hcy decreases endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and eNOS reactivity, causing endothelial dysfunction in porcine carotid and coronary arteries.10,11 As a result, individuals with elevated Hcy levels are at an increased risk for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.12,13

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the protective role of ghrelin on Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction and to test the hypothesis that ghrelin may block the endothelial injury and reduction of eNOS expression caused by Hcy. Ghrelin may also have the capacity to reduce Hcy-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. These findings may have important implications concerning ghrelin as a potential therapy for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Human ghrelin and D-ghrelin were obtained from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Belmont, CA). Other reagents including thromboxane A2 analog (9,11-Dideoxy-11a, 9 a-epoxymethanoprostaglandin F2a) (U46619), bradykinin, Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution, PBS solution, and all others, unless stated, were obtained from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) was obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY) and the antibiotic-antimycotic solution was obtained from Mediatech Inc. (Herndon, VA). The protein assay kit, polyacrylamide gels, iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit, and iQ SYBR Green SuperMix Kit were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Anti-ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1a) antibody was obtained from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Burlingame, CA). This antibody has a neutralizing activity for ghrelin.14

Isometric tension model

The myograph tension model using porcine coronary arteries has been previously described by our laboratory.15 Briefly, the myograph device (Danish Myo Technology Organ Bath 700 MO, Aarhus, Denmark) records the tension on two wires caused by contraction of the blood vessel in response to various reagents. Fresh porcine hearts were harvested and stored in cold PBS, and the right coronary artery was isolated. The artery was then divided into 5-mm rings and incubated in DMEM solution for 24 hours at 37°C. The rings were cultured in the following groups: control, ghrelin (100 ng/mL), Hcy (50 μM), and ghrelin (100 ng/mL) plus Hcy (50 μM). Following 24 hours of incubation, the rings were mounted on the myograph wires in an organ bath of Krebs Hensleit solution. The chambers were oxygenated with 100% O2 and maintained at 37°C. The rings were allowed to equilibrate for 15 minutes after being subjected in a stepwise fashion to a predetermined optimal tension of 30 milinewton (mN). After equilibration, vasoconstriction was induced with thromboxane A2 analog U46619 (3×10-8M). Once maximal contraction had reached a plateau, a concentration response curve of vasorelaxation was obtained using endothelium-dependant vasodilator bradykinin (10-9M, 10-8M, 10-7M, 10-6M, and 10-5M) at 3-minute intervals. Finally, to measure the full relaxation of the ring, endothelium-independent vasodilator sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 10-5M) was added to the organ bath. The volume of reagents added were no more than 1% of the total chamber volume to reach the final concentration required. The percent relaxation was calculated based on changes in the tension with vasodilators in relation to the maximal contraction value.

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

After treatment with ghrelin, Hcy, or ghrelin plus Hcy, the porcine coronary artery endothelial cells were scraped from the rings, and their total RNA was isolated using the Tri-Reagent kit. The iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit was used to generate cDNA from isolated mRNA. The iQ SYBR Green SuperMix Kit was then used for the real time PCR. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which is a housekeeping gene, was applied as an internal control for eNOS expression. A total of 1 μg of RNA was loaded for all samples. The GAPDH (GenBank no. AF017079) primer sequences are 5’-TGTACCACCAACTGCTTGGC-3’ forward primer and 5’-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3’ for reverse primer. eNOS (GenBank no. AY266137) primers are forward 5’-CCTACCAACGGCTCCCCTC-3’ and reverse 5’-GCTGTCTGTGTTACTGGATTC-3’. Real-time PCR was completed using the iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system. The thermal cycles for reverse transcription included 5 minutes at 25°C, 30 minutes at 42°C, and 5 minutes at 85°C. Real-time PCR was set for 3 minutes at 95°C, 40 repeated cycles of 20 seconds at 95°C, and one minute at 60°C. The sample cycle threshold (Ct) values were assessed from plots of relative fluorescence units (RFU) versus PCR cycle numbers during exponential amplification so that sample measurement comparisons were possible. Subsequently, the eNOS gene expression level for each sample was calculated as 2ˆ(40-Ct) and eNOS relative expression was normalized against GAPDH as 2ˆ[Ct (GAPDH)-Ct(eNOS)].

Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence analysis

Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence with Sirius Luminometer and FB12 software (Berthold Detection Systems GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany) was used to detect superoxide anion production by endothelial cells. Treated porcine coronary artery rings were incubated for 24 hours and then rinsed in a modified Kreb’s HEPES buffer solution. Each ring was cut longitudinally into an approximate 5 × 5 mm segment. Assay tubes were filled with 500 μL of KHBS and 25 μL lucigenin (5 μM). After mixing the reagents in the tube, the arterial segment was placed with the endothelial surface facing the bottom of the tube. Over 12 minutes, measurements of relative light units per second (RLU/s) were obtained every 15 seconds and the measurements between 5 and 10 minutes were averaged. The area of each arterial segment was measured with a caliper to normalize the data for each sample with the final unit of RLU/s/mm2.

Immunohistochemistry

Treated porcine coronary rings were fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm thick cross-sections. The sections were incubated with monoclonal antibody against human eNOS (1:1000, BD Biosciences) diluted in PBS (with 5% normal horse serum, 0.1% Triton-X 100) overnight at 4°C. Following rinsing, the sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:250) at room temperature for 40 minutes. For diaminobenzidine visualization, the sections were incubated in avidin-biotin-peroxidase solution at room temperature for one hour, followed by 0.1% diaminobenzidine and 0.003% H2O2 in TBS for 10 minutes. Next, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin, cover slipped and visualized under an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus USA Inc., Melville, NY). A SPOT-RT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI) was used to capture the images.

Cell culture

HCAECs and endothelial growth medium-2 (EGM-2) were purchased from Cambrex BioWhittaker Inc. (Walkersville, MD). When HCAECs grew to 80%-90% confluence with EGM-2 plus 10% FBS, they were undergone serum starvation for 6 hours and then, the cells were treated with different reagents including Hcy and/or ghrelin in EGM-2 plus 2% FBS for 24 hours. For anti-ghrelin receptor antibody blocking experiment, antibody (1:500) was pre-incubated with cells for 1 hour before Hcy and/or ghrelin were added into the cells.

Western blot

Total proteins were isolated from HCAECs using cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The same amount of endothelial proteins (6 μg) was resolved electrophoretically by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide), and transferred to the nitrocellulose filter. The eNOS protein was detected using a mouse anti-human eNOS monoclonal antibody diluted 1:1000 (BD Biosciences) and β-actin protein was detected using a mouse anti-human β-actin monoclonal antibody diluted 1:10000 (Chemicon). The eNOS and β-actin primary antibodies were detected with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody diluted 1:2000. Blots were developed using ECL-plus kit and analyzed with gel documentation system and analysis software (Alpha Innotech Co., San Leandro, CA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed by comparing the data between treatment and control groups using Student’s t test (two-tail, Minitab software, Sigma Breakthrough Technologies Inc., San Marcos, TX). The bradykinin-induced vasorelaxation, eNOS mRNA and superoxide anion data generated from multiple groups was analyzed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Finally, the statistical values are reported as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Ghrelin specifically blocks Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries

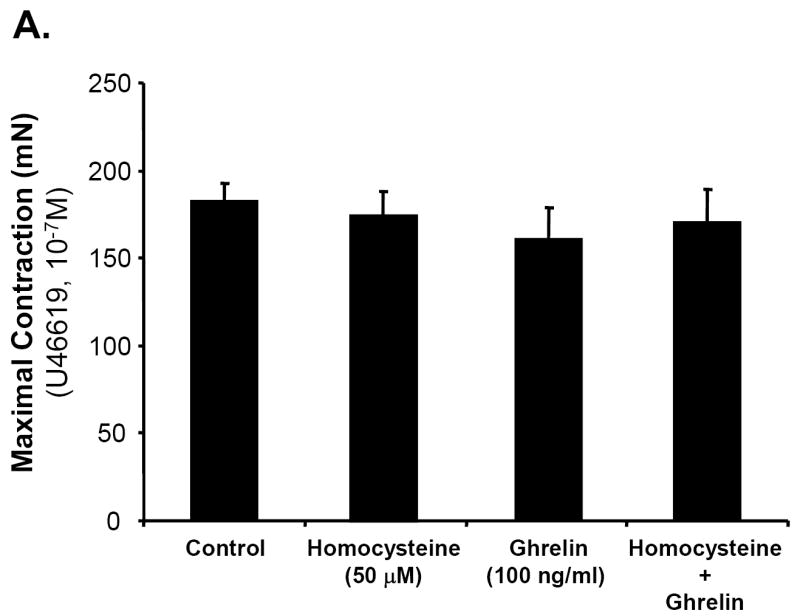

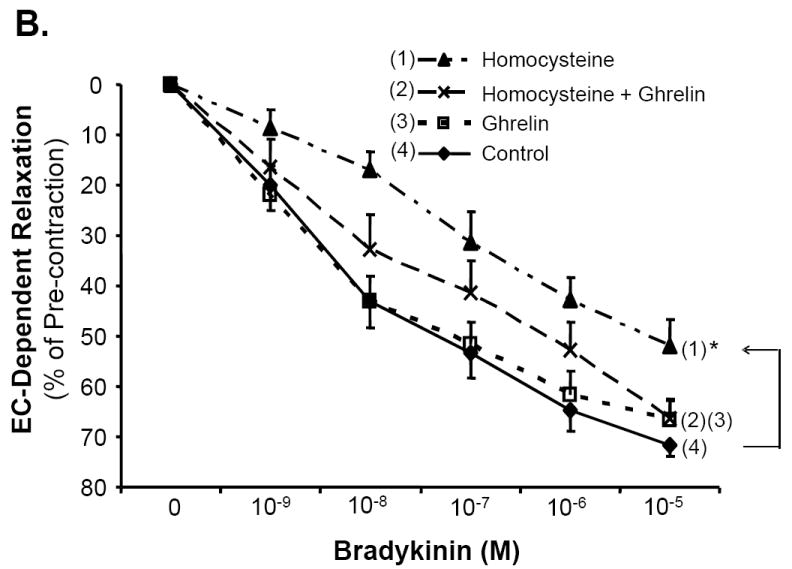

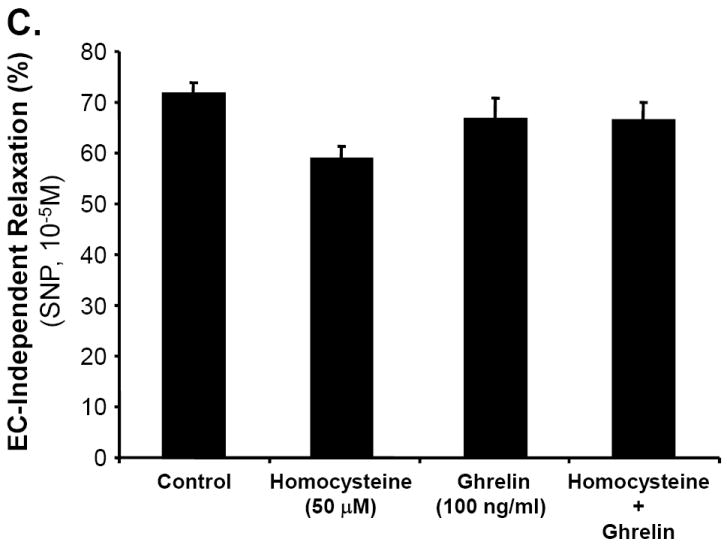

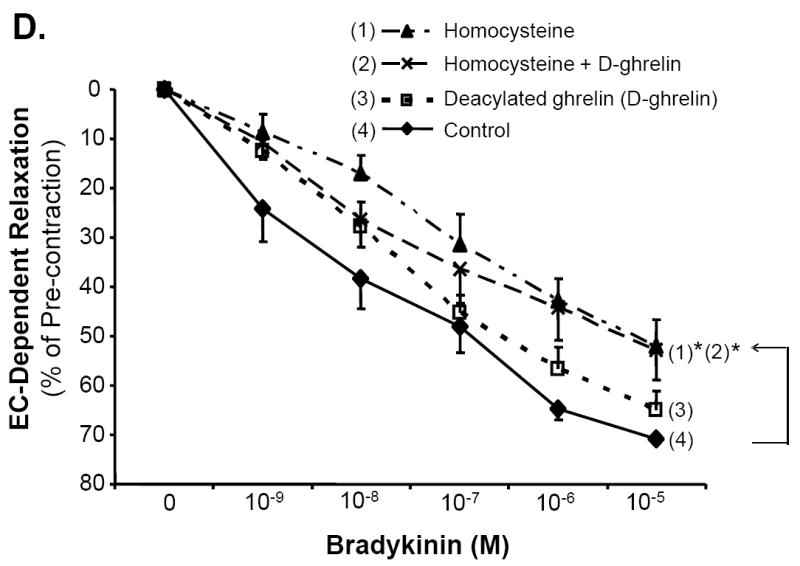

Porcine coronary artery rings were divided into four treatment groups: control, ghrelin (100 ng/mL), Hcy (50 μM), and ghrelin plus Hcy. In response to the vasoconstrictor, thromboxane A2 analog U46619 (10-7M), the vessels contracted with no significant difference among all groups (Fig 1A). The endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in response to each cumulative concentration of bradykinin was measured and depicted in Fig 1B. When the vasodilator, bradykinin (10-5M), was added to the rings, ghrelin-treated rings responded with 66.64±4.23% relaxation, not statistically different from the control group. There was a reduction in the relaxation of the Hcy-treated group (51.95±5.27%) compared with the control group (71.63±2.22%, n = 8, P<0.05, t-test and ANOVA test). However, co-treatment of ghrelin plus Hcy resulted in relaxation of 66.4±3.62%, similar to the control rings. Ghrelin did not affect endothelium-independent vasorelaxation in response to SNP in porcine coronary artery rings (Fig 1C). To confirm the specificity of ghrelin’s action on endothelial cells, non-functional D-ghrelin was used to the myograph system. As expected, D-ghrelin was not able to block the Hcy-induced inhibition of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in response to bradykinin (Fig 1D). D-ghrelin also had no effects on vasomotor reactivities in response to U46619 and SNP. Thus, ghrelin specifically blocks Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries.

Fig 1.

Effects of ghrelin and homocysteine (Hcy) on vasomotor functions in porcine coronary arteries. The vessel rings were treated with or without ghrelin, Hcy or Hcy plus ghrelin for 24 hours. Vasomotor reactivity was determined by the myograph system in response to vasoactive drugs. A. Vessel contraction in response to thromboxane A2 analog U46619 (10-7M). B. Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in response to accumulative concentrations of bradykinin (10-9 to 10-5M). C. Endothelium-independent vasorelaxation in response to sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 10-5M). n = 8. *P<0.05 (t-test and ANOVA test). D. Effects of deacylated ghrelin (D-ghrelin) and homocysteine (Hcy) on vasomotor functions in porcine coronary arteries. The vessel rings were treated with or without D-ghrelin, Hcy or Hcy plus D-ghrelin for 24 hours. The vessel rings were precontracted with thromboxane A2 analog U46619 (10-7M), and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation was recorded in response to accumulative concentrations of bradykinin (10-9 to 10-5M). n = 8. *P<0.05 (t-test and ANOVA test).

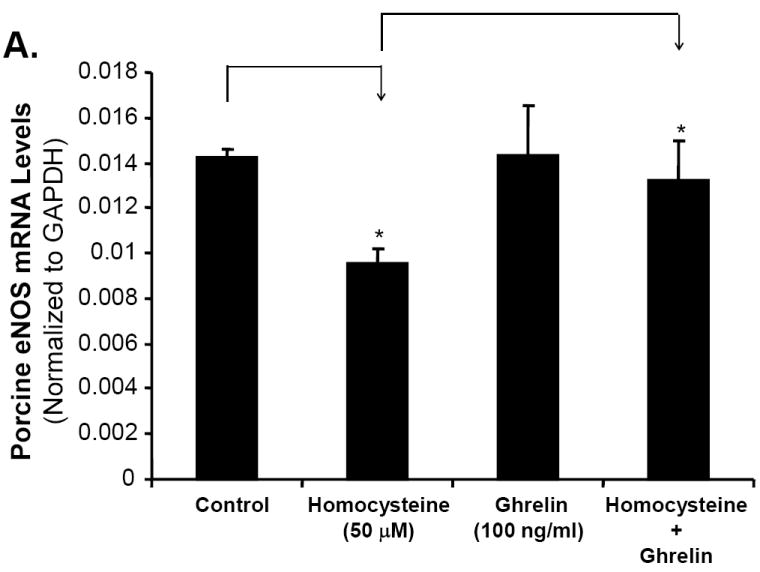

Ghrelin, not D-ghrelin, blocks Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS mRNA levels in porcine coronary arteries

The level of eNOS mRNA in treated porcine coronary endothelial cells was measured using real-time PCR. All values were normalized to GAPDH as the internal control. Treatment with ghrelin resulted in eNOS mRNA level of 0.014±0.002, not statistically different from the control group (0.014±0.0003). There was a 47% reduction in the eNOS mRNA level in Hcy-treated rings (0.0095±0.0006) when compared with the control untreated rings (Fig 2A, n = 3, P<0.05). However, co-treatment of ghrelin with Hcy led to eNOS mRNA level of 0.013±0.0018, which was similar to the control group, while it was significantly higher than that in the Hcy group (Fig 2A, n = 3, P<0.05, t-test and ANOVA test). By contrast, non-functional D-ghrelin was not able to block Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS mRNA levels in porcine coronary arteries (Fig 2B). Thus, ghrelin specifically blocks Hcy-induced eNOS down-regulation in porcine coronary artery rings.

Fig 2.

Effects of ghrelin, deacylated ghrelin (D-ghrelin) and homocysteine (Hcy) on eNOS mRNA levels in porcine coronary arteries. The vessel rings were treated with or without ghrelin, D-ghrelin, Hcy, or Hcy plus ghrelin or D-ghrelin for 24 hours. The mRNA levels of porcine eNOS and GAPDH were determined by real time PCR. A. Effects of ghrelin and Hcy. B. Effects of D-ghrelin and Hcy. Relative eNOS mRNA levels were calculated as 2ˆ[Ct (GAPDH)-Ct(eNOS)]. n = 3. *P<0.05. Both t-test and ANOVA test were performed.

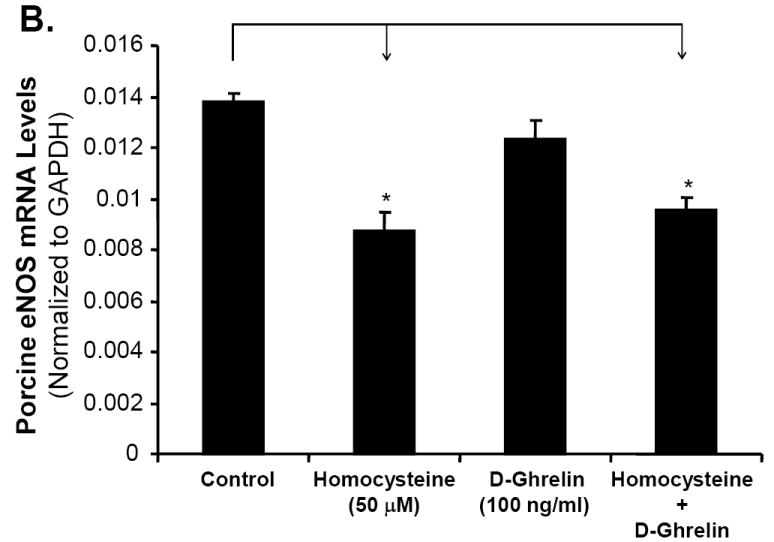

Ghrelin blocks Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS immunoreactivity in porcine coronary arteries

Immunohistochemical staining for eNOS protein was performed in control, ghrelin, Hcy, and ghrelin plus Hcy treated porcine coronary artery rings. As depicted in Fig 3, eNOS immunoreactivity of porcine coronary artery rings treated with ghrelin reveals the same intensity of staining as the control rings. Treatment with Hcy resulted in a reduction of eNOS staining. However, addition of ghrelin to Hcy resulted in eNOS staining intensity to return to the control level.

Fig 3.

Effects of ghrelin and homocysteine (Hcy) on eNOS immunoreactivity in porcine coronary arteries. The vessel rings were treated with or without ghrelin, Hcy or Hcy plus ghrelin for 24 hours. Porcine eNOS protein levels were determined with immunohistochemistical staining. A. Control. B. Homocysteine (Hcy). C. Ghrelin. D. Hcy plus ghrelin.

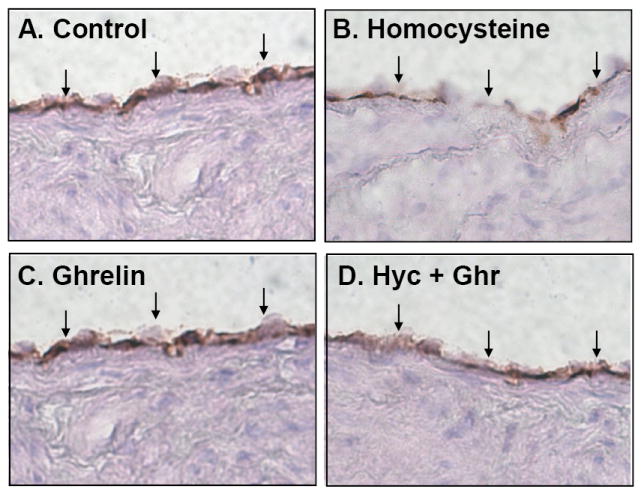

Ghrelin blocks Hcy-induced increase in superoxide anion in porcine coronary arteries

In order to determine whether ghrelin could block the Hcy-induced oxidative stress, a key molecular event of Hcy vascular pathogenesis, the production of superoxide anion, a major type of ROS, was analyzed with the lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence method. As shown in Fig 4, there was a 117% increase in the amount of superoxide anion production in Hcy-treated rings (25.2±2.7 RLU/s/mm2) versus control rings (11.58±1.1 RLU/s/mm2, n = 8, P<0.05, t-test and ANOVA test). Ghrelin-treated rings led to superoxide anion production of 13.26±0.8 RLU/s/mm2, which was not statistically different from the control. The addition of ghrelin to Hcy-treated rings led to a superoxide anion production of 15.57±1.4 RLU/s/mm2, similar to the control group. Thus, ghrelin was able to significantly reduce the superoxide anion production by 61% over that in Hcy-treated vessels (Fig 4, n = 8, P<0.05).

Fig 4.

Effects of ghrelin and homocysteine (Hcy) on superoxide anion production in porcine coronary arteries. The vessel rings were treated with or without ghrelin, Hcy or Hcy plus ghrelin for 24 hours. Superoxide anion production from the endothelial surface of porcine coronary rings was detected by lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence. Relative light units per second (RLU/s) were recorded and the measurements between 5 and 10 minutes were averaged and normalized to the area of each arterial segment as RLU/s/mm2. n = 8. *P<0.05. Both t-test and ANOVA test were performed.

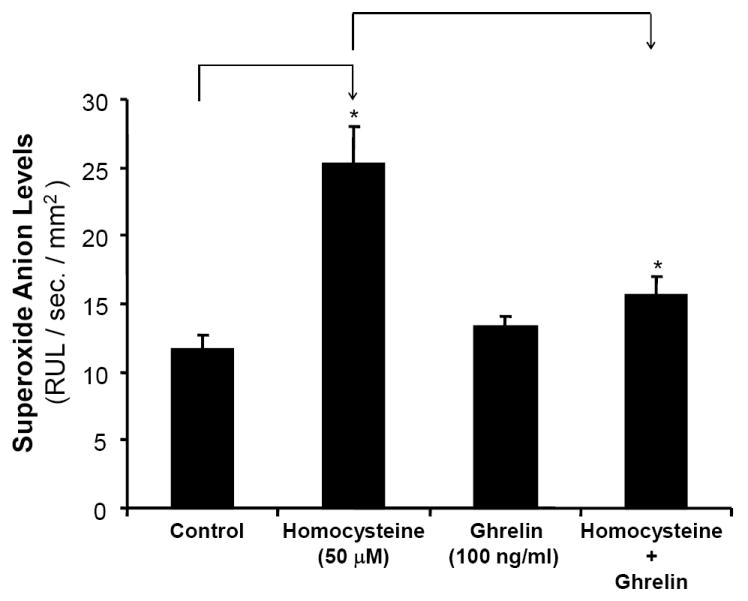

Ghrelin, not D-ghrelin, blocks Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels in HCAECs

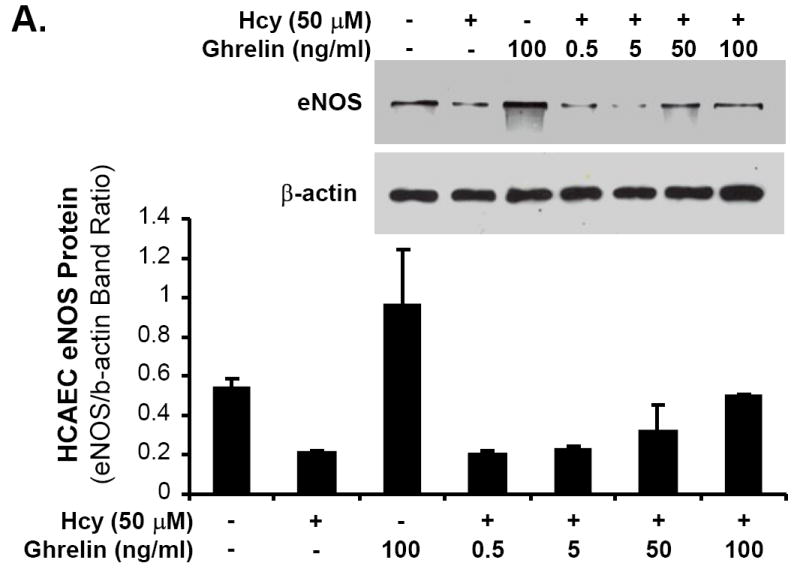

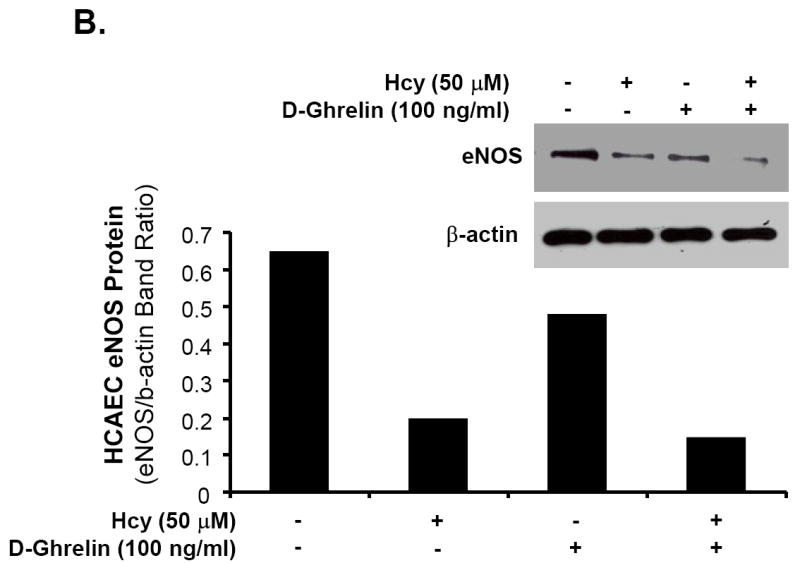

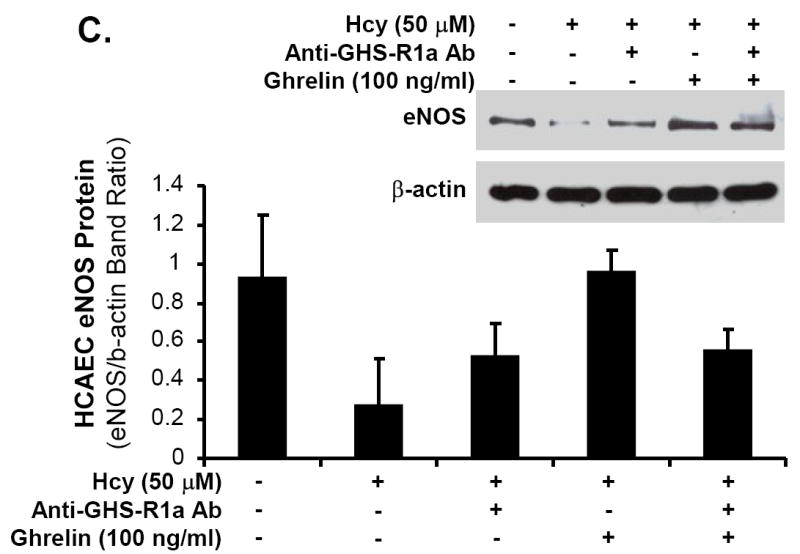

HCAECs were treated with Hcy (50 μM) for 24 hours and eNOS protein levels were determined by western blot analysis and band intensity quantitation. Hcy substantially decreased eNOS protein levels, while ghrelin effectively blocked Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig 5A). However, D-ghrelin (100 ng/mL) did not have such blocking effects of ghrelin (Fig 5B). Furthermore, neutralizing antibody against ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1a, 1:500 dilution) effectively inhibited ghrelin’s blocking effect on Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels in HCAECs (Fig 5C). Thus, ghrelin’s effect is receptor-dependent.

Fig 5.

Effects of ghrelin and homocysteine (Hcy) on eNOS protein levels in HCAECs. The cells were treated with or without ghrelin, Hcy (50 μM) or plus ghrelin (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Human eNOS protein levels were determined with western blot and band intensity quantitation. A. Ghrelin concentration-dependent study (0, 0.5, 5, 50 and 100 ng/mL). B. Effect of D-ghrelin (100 ng/mL). C. Blocking effect of anti-ghrelin receptor antibody (anti-GHS-R1a Ab, 1:500).

DISCUSSION

Ghrelin, a ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R), has been extensively studied in relation to obesity and appetite suppression. A recent cohort study regarding obesity related to atherosclerosis found a direct link between the two factors. The authors noted a greater risk of coronary artery calcium (17%), internal carotid artery intima-media thickness (32%), common carotid artery intima-media thickness (45%), and increased left ventricular mass.16 Basal plasma ghrelin was significantly lower in the patients with obesity-associated metabolic syndrome than in healthy controls.17 The metabolic and cardiovascular effects of ghrelin are believed to be mediated by both growth hormone-dependent and independent mechanisms.18 Nagaya et al. showed that administration of ghrelin to healthy adults leads to an increase in cardiac index and stroke volume without an increase in the heart rate and plasma norepinephrine levels.3 Administration of intravenous ghrelin has also been beneficial in myocardial reperfusion injury and cardiac cachexia due to probable inhibition of cytokine release. Specifically, ghrelin may inhibit basal and TNF-α-induced chemotactic cytokine production and mononuclear cell adhesion, promoting improved cardiovascular health and function.6 In the current study, ghrelin was used as a protective agent to effectively block Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction, eNOS down-regulation and oxidative stress in porcine coronary arteries. The specific concentration of ghrelin (100 ng/mL) was selected based on previous studies and documented plasma levels.12,19-21 Human physiologic plasma concentration of ghrelin was reported around 0.75 ng/mL. However, one study noted physiologic plasma ghrelin levels in healthy adults to be 20.35 ± 5.10 ng/mL.22 In many in vitro studies, much high concentrations of ghrelin are used such as 100 ng/mL.6,23,24 Although this concentration is much higher than physiologic levels, it may have therapeutic values. For therapeutic purpose, we also used this concentration (100 ng/mL) to effectively block Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. Furthermore, we have performed additional experiments using human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs). Different concentrations of ghrelin (0.5, 5, 50 and 100 ng/mL) were used in the experiments. Ghrelin effectively blocked Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels at 50 and 100 ng/mL.

Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hcy >100 μM) is a rare inborn error of metabolism that has been correlated with premature vascular diseases, including thromboembolic events and atherosclerosis. It typically presents in the third or fourth decade of life. If untreated by the age of 30, 50% suffer acute thromboembolic events with a 20% mortality rate.25 The severe form results from a genetic error resulting in a deficiency of cystathionine ß-synthase.13 In addition, a more common and milder form of the disorder may be induced by various nutritional deficiencies (folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6), chronic diseases such as renal failure, pernicious anemia, hypothyroidism, and various medications and toxins.13 Hcy is believed to affect the coagulation system as well as the resistance of endothelial cells to thrombosis and the vasodilatory function of nitric oxide (NO).12 Nygård et al. demonstrated a concentration-dependant relation between total plasma Hcy levels and mortality from cardiovascular causes.13 These studies along with our previous study were utilized to select the appropriate concentration of Hcy (50 μM) used in the current investigation.10,11

Through previous experiments, our laboratory has established and characterized an in vitro culture model of porcine coronary artery rings utilizing myograph analysis.10,11,26-28 Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation was analyzed based on a challenge of bradykinin, a potent vasodilator that acts through endothelial B2 kinin receptors to stimulate the release of NO through eNOS activation.29 Several clinical risk factors or molecules have been examined by our laboratory to find the effect on endothelial functions.10,11,26-28 In the current study, ghrelin was used to negate the damaging effects of Hcy on the porcine coronary artery. Based on myograph data, Hcy reduced endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in coronary vessels by 31% compared with untreated controls. Co-treatment with ghrelin, however, effectively blocked Hcy-induced decrease in endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Importantly, D-ghrelin did not change the Hcy-induced reduction in vasorelaxation. This suggests that the functionality and mechanism of ghrelin on the endothelium depends on the acylated portion of the molecule. In the current report, it could be a limitation that the time course study was not performed in the porcine coronary artery model because the 24-hour time point is the optimal time for this model system. Due to the porcine coronary precondition in the culture system requires certain hours, the vascular response of these vessel rings is not sensitive or consistent to certain reagents include Hcy and ghrelin at earlier time points.

Central to vascular biology and endothelial cell homeostasis is the regulation of NO bioavailability. NO is generated by eNOS and is a potent vasodilator with multiple cardiovascular functions. Patients with eNOS polymorphism and a reduction in eNOS reactivity exhibit higher rates of myocardial events.30 The observed changes in the current study within endothelium-dependent relaxation are primarily due to a decrease in eNOS expression. This theory was confirmed by real-time PCR data showing a significant decrease in eNOS mRNA levels of Hcy-treated porcine coronary artery rings and then an increase to control levels when treated with ghrelin. A 31% reduction of eNOS mRNA levels in Hcy-treated porcine coronary artery rings compared with control rings may account for the Hcy-induced inhibition of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. When Hcy-treated artery rings were then combined with ghrelin and incubated over 24 hours, only a 7% reduction from control eNOS mRNA levels was observed. Immunoreactivity of eNOS was reduced in Hcy-treated vessels; however, the ability to block Hcy with co-treatment of ghrelin was confirmed as eNOS staining returned to near control levels. These findings, together with the functional data obtained from myograph analysis, suggest a potential mechanism of improved function and reversal of the Hcy-induced damage to endothelial cells via increased eNOS expression and NO bioavailability by treatment with ghrelin. Furthermore, we have performed several new experiments using human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs). Specifically, we treated HCAECs with Hcy (50 μM) for 24 hours and determined eNOS protein levels by western blot analysis and band intensity quantitation. We showed that homocyteine substantially decreased eNOS protein levels. Different concentrations of ghrelin (0.5, 5, 50 and 100 ng/mL) were used in the experiments. Indeed, ghrelin effectively blocked Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner. However, D-ghrelin did not have such blocking effects. A neutralizing antibody against ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1a) effectively inhibited ghrelin’s blocking effect on homocysteine-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels in HCAECs. Thus, ghrelin’s effect is receptor-dependent.

Disproportion in the quantity of ROS generated during aerobic metabolism is known to lead to oxidative stress and contributes to vascular disease. This process is carried out through a variety of mechanisms including NO consumption and depletion,31 intracellular alkalinization,32 and regulation of gene transcription.33 The chemiluminescence method is a reliable and reproducible method for measuring ROS production.34 In the present analysis, ghrelin reduced the production of superoxide anion, a major type of ROS, in Hcy-treated rings. These outcomes are comparable to work done in other laboratories. Iantorno et al. demonstrated that ghrelin stimulates endothelial cell NO production through GHS-R1a, PI3K, and Akt pathways, thereby improving endothelial function.5 Shimizu et al. showed that administration of ghrelin to growth hormone-deficient rats leads to improved vasorelaxation and increased eNOS expression of the thoracic aorta.1

Major enzymatic activity of eNOS is to convert L-arginine to L-citrulline and NO. This enzyme activity is maintained by co-enzyme component tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and a sufficient level of L-arginine. However, if H4B and/or L-arginine are low or not available to eNOS, eNOS can activate oxygen and generate superoxide free radicals, but not NO. This process is termed “eNOS uncoupling”, which has a negative impact on endothelial functions. Several compounds including lucigenin, nitroblue tetrazolium, 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol, and quinones can cause eNOS uncoupling.35,36. A previous study demonstrated that Hcy could cause eNOS uncoupling and increased superoxide anion production though alternation of intracellular BH4 availability.37 Thus, it is possible that increased superoxide anion could be generated from eNOS uncoupling in the current study. In addition, we did not confirm whether reduced NO availability is solely responsible for Hcy-induced decrease in endothelium-dependent relaxation and increase in superoxide production. Application of eNOS inhibitor such as NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) in combination with Hcy in the experimental models could address this important issue. Thus, it is warranted to further investigations.

Mechanistic work regarding superoxide production related to ghrelin has been shown in previous work.34 Li et al. examined the role of proinflammatory cytokines,6 reporting that ghrelin inhibits the TNF-α-induced IL-8 release in a concentration-dependent manner. Mononuclear cell adhesion molecules have been an integral part of vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis, induced by chemotactic cytokines. Ghrelin inhibits the activity of NF-κB, crucial in the production of chemotactic cytokines and adhesion molecule expression that adversely affects endothelial cell response.6 Ghrelin has also been shown to improve left ventricular function in heart failure.15,38 In our previous studies regarding NADPH oxidase subunits, we noted an increase in the protein expression of these subunits. Also, dihydroethidium staining and flow cytometry analysis showed a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential indicating an increase in free oxygen radical species from mitochondrial dysfunction.39,40 Xu et al. showed that ghrelin time-dependently stimulated Akt and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation in both cultured endothelial cells and intact vessels. Also, ghrelin’s mechanism of action on endothelial cells may be linked to the GHS-R, a seven-transmemberane G protein-coupled ghrelin receptor. Stimulation of GHS-R with ghrelin leads to activation of G protein, calcium mobilization and mutiple downstream signaling.41

Beside determental effects of Hcy on cardiovascular system,10,13 the elevation of Hcy levels is also associated with peripheral arterial disease as well as venous disease such as deep venous thrombosis.42 Thus, the effects of Hcy are present in other peripheral vascular beds besides coronary arteries. However, there is not much reference to ghrelin’s effect on peripheral vascular disease within the literature. Based on the blocking effect of ghrelin on Hcy-induced vascular damage, our data may be extrapolated to other areas of the vasculature.

Although there is strong evidence to suggest that ghrelin leads to increased food intake and increased lipid deposition, its cardiovascular benefits, such as inhibition of cytokine production and improved left ventricular function have also been well documented. Ghrelin receptors have been isolated in various tissues such as endocrine glands and cardiovascular tissues. In addition, receptor density changes have been demonstrated as an important part of the cardiovascular effects of ghrelin.43 Targeting the specific tissue receptors with modification of the ghrelin molecule may achieve the desired cardiovascular effects without activating the unwanted effects of ghrelin.

In conclusion, ghrelin is a potent and effective protein that inhibits the effects of Hcy and other potentially damaging mechanisms on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in porcine coronary arteies. The mechanism of improvement in endothelial function relates to improved eNOS expression and a reduction in oxidative stress. Ghrelin also has a potent effect on blocking Hcy-induced decrease in eNOS protein levels in HCACEs in a concentration-dependent manner and its effect is GHS-R1a specific. Enhanced eNOS expression leading to an increase in NO release is an important factor in the treatment of atherosclerosis. As an increasing number of patients with premature vascular disease are being diagnosed with hyperhomocysteinemia, the potential for the treatment of these individuals with ghrelin warrants further investigation and may lead to exciting new therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (Yao: DE15543; Lin: HL076345; and Chen: HL65916, HL72716, and EB-002436), and from the Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Texas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shimizu Y, Nagaya N, Teranishi Y, Imazu M, Yamamoto H, Shokawa T, et al. Ghrelin improves endothelial dysfunction through growth hormone-independent mechanisms in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:830–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wren AM, Small CJ, Abbott CR, Dhillo WS, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, et al. Ghrelin causes hyperphagia and obesity in rats. Diabetes. 2001;50:2540–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagaya N, Kojima M, Uematsu M, Yamagishi M, Hosoda H, Oya H, et al. Hemodynamic and hormonal effects of human ghrelin in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1483–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.5.R1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch GN, Loscalzo J. Homocysteine and atherothrombosis. N Eng J Med. 1998;338:1042–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804093381507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iantorno M, Chen H, et al. Ghrelin has novel vascular actions that mimic PI 3-kinase-dependent actions of insulin to stimulate production of NO from endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E756–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00570.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li WG, Gavrila D, Liu X, Wang L, Gunnlaugsson S, Stoll LL, et al. Ghrelin inhibits proinflammatory responses and nuclear factor-κB activation in human endothelial cells. Circulation. 2004;109:2221–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127956.43874.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–60. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardiovascular Diseases. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2005 Update. American Heart Association; http://www.americanheart.org. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross R. Atherosclerosis-An inflammatory disease. N Eng J Med. 1999;340:115–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C, Conklin BS, Ren Z, Zhong D. Homocysteine decreases endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in porcine arteries. J Surg Res. 2002;102:22–30. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou W, Chai H, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Ginsenoside Rb1 blocks homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagaya N, Moriya J, Yasumara Y, Uematsu M, Ono F, Shimizu W, et al. Effects of ghrelin administration on left ventricular function, exercise capacity, and muscle wasting in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:3674–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149746.62908.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nygård O, Nordrehaug JE, Refsum H, Ueland PM, Farstad M, Vollset SE. Plasma homocysteine levels and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. N Eng J Med. 1997;337:230–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viani I, Vottero A, Tassi F, Cremonini G, Sartori C, Bernasconi S, Ferrari B, Ghizzoni L. Ghrelin inhibits steroid biosynthesis by cultured granulosa-lutein cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1476–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaya N, Uematsu M, Kojima M, Ikeda Y, Yoshihara F, Shimizu W, et al. Chronic administration of ghrelin improves left ventricular function and attenuates development of cardiac cachexia in rats with heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1430–5. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke GL, Bertoni AG, Shea S, Tracy R, Watson KE, Blumenthal RS, Chung H, Carnethon MR. The impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical vascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:928–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tesauro M, Schinzari F, Iantorno M, Rizza S, Melina D, Lauro D, Cardillo C. Ghrelin endothelial function in patients with metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2005;112:2986–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith RG, Jiang H, Sun Y. Developments in ghrelin biology and potential clinical relevance. Trends improves Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:436–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enomoto M, Nagaya N, Uematsu M, Okumura H, Nakagawa E, Ono F, et al. Cardiovascular and hormonal effects of subcutaneous administration of ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing peptide, in healthy humans. Clin Sci. 2003;105:431–5. doi: 10.1042/CS20030184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagaya N, Kangawa K. Ghrelin improves left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac cachexia in heart failure. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:146–51. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, Breen PA, Ma MK, Dellinger EP, Purnell JQ. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1623–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An JY, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Jin DK, Kim S. Clinical significance of ghrelin concentration of plasma and tumor tissue in patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Res. 2007;143:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixit VD, Schaffer EM, Pyle RS, Collins GD, Sakthivel SK, Palaniappan R, Lillard JW, Jr, Taub DD. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:57–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Liu X, Shu Q, Li S, Luo F. Ghrelin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury through no pathway. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:BR141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surowiec SM, Conklin BS, Li LS, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Chen C. A new perfusion culture system used to study human vein. J Surg Res. 2000;88:34–41. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kougias P, Chai H, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Adipocyte-derived cytokine resistin causes endothelial dysfunction of porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:691–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paladugu R, Fu W, Conklin BS, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, et al. HIV Tat protein causes endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:549–55. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chai H, Zhou Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Ginsenosides block HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir-induced vascular dysfunction of porcine coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2965–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01271.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groves P, Kurz S, Just H, Drexler H. Role of endogenous bradykinin in human coronary vasomotor control. Circulation. 1995;92:3424–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leeson CP, Hingorani AD, Mullen MJ, Jeerooburkhan, Kattenhorn NM, Cole TJ, et al. Glu298Asp endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphism interacts with environmental and dietary factors to influence endothelial function. Circ Res. 2002;90:1153–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020562.07492.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibanuma M, Kuroki T, Nose K. Superoxide as a signal for increase in intracellular pH. J Cell Physiol. 1988;136:379–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041360224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer M, Schreck R, Baeuerle PA. H2O2 and antioxidants have opposite effects on activation of NF-kappa B and AP-1 in intact cells AP-1 as secondary antioxidant-responsive factor. Embo J. 1993;12:2005–15. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawczynska-Drozdz A, Olszanecki R, Jawien J, Brzozowski T, Pawlik WW, Korbut R, Guzik TJ. Ghrelin inhibits vascular superoxide production in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:764–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauersachs J, Schafer A. Tetrahydrobiopterin and eNOS dimer/monomer ratio—a clue to eNOS uncoupling in diabetes? Cardiovas Res. 2005;65:768–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuehr D, Pou S, Rosen GM. Oxygen Reduction by Nitric-oxide Synthases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14533–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topal G, Brunet A, Millanvoye E, Boucher J, Rendu F, Devynck M, David-Dufilho M. Homocysteine induces oxidative stress by uncoupling of no synthase activity through reduction of tetrahydrobiopterin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1532–41. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagaya N, Kangawa K. Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing peptide, in the treatment of chronic heart failure. Regul Pept. 2003;114:71–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(03)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohashi R, Yan S, Mu H, Chai H, Yao Q, Lin PH, Chen C. Effects of homocysteine and ginsenoside Rb1 on endothelial proliferation and superoxide anion production. J Surg Res. 2006;133:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Mu H, Chai H, Liao D, Yao Q, Chen C. Human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor ritonavir inhibits cholesterol efflux from human macrophage-derived foam cells. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:304–14. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu X, Jhun BS, Ha CH, Jin ZG. Molecular mechanisms of ghrelin-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation. Endocrinology. 2008 May 1; doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0255. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhargava S, Parakh R, Manocha A, Ali A, Srivastava LM. Prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in vascular disease: comparative study of thrombotic venous disease vis-à-vis occlusive arterial disease. Vascular. 2007;15:149–53. doi: 10.2310/6670.2007.00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katugampola SD, Maguire JJ, Kuc RE, Wiley KE, Davenport AP. Discovery of recently adopted orphan receptors for apelin, urotensin II, and ghrelin identified using novel radioligands and functional role in the human cardiovascular system. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:369–74. doi: 10.1139/y02-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]