Abstract

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the benefit of using a new fluorescence-reflectance imaging system, Onco-LIFE, for the detection and localization of intraepitheal neoplasia and early invasive squamous cell carcinoma. A secondary objective was to evaluate the potential use of quantitative image analysis with this device for objective classification of abnormal sites.

Design

This study was a prospective, multicenter, comparative, single arm trial. Subjects for this study were aged 45 to 75 years and either current or past smokers of more than 20 pack-years with airflow obstruction, forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity less than 75%, suspected to have lung cancer based on either sputum atypia, abnormal chest roentgenogram/chest computed tomography, or patients with previous curatively treated lung or head and neck cancer within 2 years.

Materials and Methods

The primary endpoint of the study was to determine the relative sensitivity of white light bronchoscopy (WLB) plus autofluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy compared with WLB alone. Bronchoscopy with Onco-LIFE was carried out in two stages. The first stage was performed under white light and mucosal lesions were visually classified. Mucosal lesions were classified using the same scheme in the second stage when viewed with Onco-LIFE in the fluorescence-reflectance mode. All regions classified as suspicious for moderate dysplasia or worse were biopsied, plus at least one nonsuspicious region for control. Specimens were evaluated by the site pathologist and then sent to a reference pathologist, each blinded to the endoscopic findings. Positive lesions were defined as those with moderate/severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ (CIS), or invasive carcinoma. A positive patient was defined as having at least one lesion of moderate/severe dysplasia, CIS, or invasive carcinoma. Onco-LIFE was also used to quantify the fluorescence-reflectance response (based on the proportion of reflected red light to green fluorescence) for each suspected lesion before biopsy.

Results

There were 115 men and 55 women with median age of 62 years. Seven hundred seventy-six biopsy specimens were included. Seventy-six were classified as positive (moderate dysplasia or worse) by pathology. The relative sensitivity on a per-lesion basis of WLB + FLB versus WLB was 1.50 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26–1.89). The relative sensitivity on a per-patient basis was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.13–1.70). The relative sensitivity to detect intraepithelial neoplasia (moderate/severe dysplasia or CIS) was 4.29 (95% CI, 2.00–16.00) and 3.50 (95% CI, 1.63–12.00) on a per-lesion and per-patient basis, respectively. For a quantified fluorescence reflectance response value of more than or equal to 0.40, a sensitivity and specificity of 51% and 80%, respectively, could be achieved for detection of moderate/severe dsyplasia, CIS, and microinvasive cancer.

Conclusions

Using autofluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy as an adjunct to WLB with the Onco-LIFE system improves the detection and localization of intraepitheal neoplasia and invasive carcinoma compared with WLB alone. The use of quantitative image analysis to minimize interobserver variation in grading of abnormal sites should be explored further in future prospective clinical trial.

Keywords: Autofluorescence, Bronchoscopy, Early detection, Lung neoplasm, Screening, Intraepithelial neoplasm, Dysplasia

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer and cancer-deaths in the world.1,2 It accounts for 13% of new cancer diagnoses, is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and women, and is responsible for 29% of all cancer deaths. Lung cancer survival is strongly associated with the stage of disease and tumor size at the time of diagnosis3—the 5-year relative survival rate when disease is diagnosed at a local stage is 49%, but drops to 2% if the cancer has spread from the primary tumor. Five-year survival rates are significantly higher for preinvasive stage 0 lung cancers (carcinoma in situ [CIS]) at approximately 74 to 91%.4–6 Currently, only 16% of lung cancers are diagnosed when disease is localized and few lung cancers are diagnosed at stage 0, resulting in a combined 5-year survival rate of only 15%.7

White light bronchoscopy (WLB) is usually used in the detection of lung cancer. Nevertheless, although conventional bronchoscopy can be used to detect early lung cancer, the detection of preinvasive lesions is difficult even for experienced bronchoscopists. A study by Woolner et al.8 showed that only 29% of CIS lesions were visible to experienced bronchoscopists. The detection of moderate to severe dysplasia is even more difficult under WLB.

Autofluorescence endoscopy (AFB) improves the sensitivity for detection of preinvasive lesions in the lung.9 AFB capitalizes on the observation that when the bronchial surface is illuminated by blue/violet light, normal bronchial tissues fluoresce strongly in the green, whereas premalignant and malignant tissues have significantly lower green autofluorescence. 10–13 AFB, when used as an adjunct to WLB, capitalizes on this difference to enhance a bronchoscopist’s ability to differentiate areas of intraepithelial neoplasia in the tracheobronchial tree.6,9,13–28 In addition to single center studies, two multicenter and single as well as two randomized clinical trials have documented the usefulness of AFB as an adjunct to WLB for detection of high-grade dysplasia and CIS.9,17,28,29

The newly developed Onco-LIFE device (Onco-LIFE Endoscopic Light Source and Video Camera; Xillix Technologies Corp.; Richmond, BC, Canada) is a multimode bronchoscopic imaging system for both white light and fluorescence bronchoscopy. In white light mode, the device functions similar to the conventional fiberoptic bronchoscopic imaging systems, illuminating the tissue with a broad spectrum, visible light, and acquiring full color video images. In fluorescence mode, the device uses blue light (395–445 nm) and small amount of red light (675–720 nm) from a filtered mercury arc lamp for illumination. The Onco-LIFE camera then captures and combines the green autofluorescence image and red reflectance image and displays the combined fluorescence-reflectance images at normal video rates on a color video monitor. Whereas the green autofluorescence image will change with the pathology of the bronchial tissue, the red reflectance image intensity is not significantly affected by tissue pathology and can therefore be used as a reference signal that corrects for differences in light intensities from changes in angle and distance of the bronchoscope from the bronchial surface. An area demarcated by a small target in the center of the displayed fluorescence-reflectance image is further processed and a value based on the ratio of red reflectance to green fluorescence signal intensities in that area is calculated.

Combining the red reflectance image with the green fluorescence image has the theoretical advantage of enhancing the contrast between premalignant, malignant, and normal tissues (when compared with the use of red fluorescence image in earlier technology) and also of improving image definition, because reflected light images can be captured with less sensitive, but more spatially precise image sensors. Using reflected red light as a reference also has the theoretical advantage over using reflected blue/green light in that it is absorbed less by hemoglobin and hence may be influenced less by changes in vascularity associated with inflammation. Red light is also more uniformly scattered within the tissue. It is re-emitted in a more diffuse manner than blue or green light and may serve as a better reference.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether using such autofluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy (ARB) as an adjunct to WLB with Onco-LIFE could improve the bronchoscopist’s ability to locate areas suspicious of moderate/severe dysplasia, CIS, and invasive carcinoma as compared with WLB alone. The secondary objective was to determine whether WLB + ARB could detect intraepithelial neoplasms (moderate/severe dysplasia and CIS) better than WLB alone. In addition, as an exploratory study, we collected data to determine whether it might be feasible to use quantitative imaging as a computed assisted aid to minimize interobserver variation in classification of normal and abnormal sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a multicenter, prospective, comparative, single arm trial. Subjects first underwent WLB followed by Onco-LIFE, and, hence, acted as their own control. Each clinical center’s pathologist, and the reference pathologist, was blinded to the endoscopic visual classifications of biopsied lesions. The institutional review board at each clinical center approved the protocol before study initiation.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the relative sensitivity of a WLB + ARB examination as compared with a WLB examination alone for the detection of moderate/severe dysplasia, CIS, or invasive cancer. Secondary endpoints included an additional relative sensitivity measure for the detection of moderate/severe dysplasia or CIS (i.e., invasive cancer excluded from analysis). This parameter was specifically measured to ascertain the ability of WLB + ARB to detect and localize preinvasive lesions. In addition, the false-positive rate (i.e., 1-specificity) was determined.

To compare devices, a population with the highest likelihood of abnormal mucosa was selected. The criteria for enrollment in the study were aged 45 to 75 years and either current or past smokers of more than 20 pack-years with airflow obstruction defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity less than 75%, suspected to have lung cancer based on either sputum atypia, abnormal chest roentgenogram/chest computed tomography, or patients with previous curatively treated lung or head and neck cancer within 2 years.

Patients were excluded if they had uncontrolled hypertension, unstable angina, known or suspected pneumonia, acute bronchitis within the previous month, known uncontrollable bleeding disorders, bronchoscopy within previous 3 years with no available bronchoscopy report or more than or equal to 1 bronchoscopy in previous 3 years with more than four biopsies. Subjects were also excluded if they had treatment with photosensitizing or retinoid chemopreventative drugs within previous 12 months, treatment with ionizing radiation or cytotoxic chemotherapy agents within previous 6 months, known allergy to xylocaine, fentanyl, morphine, midazolam, diazepam, and/or codeine (if used), treatment with anticoagulants in previous 6 days, or pregnancy. All patients who participated in the trial gave written informed consent. In total, 204 subjects at seven sites in Europe and North America met the enrollment criteria. The number of patients enrolled at each site ranged from 4 to 65.

The trial was conducted in two phases: a training phase and a data collection phase. The training phase encompassed 18 of the 204 subjects who underwent the investigational procedure described below. Data obtained from these subjects was included in the analysis of safety, but not in the efficacy analyses. The data collection phase encompassed the remaining 186 subjects. Nevertheless, 16 of these patients were excluded from efficacy analyses because of reasons, such as unavailability of reference pathology, violation of enrollment criteria, etc., leaving 170 subjects evaluated to collect efficacy data.

The examination was conducted using local anesthesia and conscious sedation with midazolam, fentanyl, or alfentanyl. All bronchoscopies were videotaped and involved examination of the vocal cords, trachea, main carina, and orifices of the subsegmental bronchi to the extent that they could be examined without causing trauma to the bronchial wall. Unless contraindicated, the bronchoscopist examined at least to the third generation bronchi.

Bronchoscopy with Onco-LIFE was carried out in two stages. The first stage was performed under white light. During this stage, sites of interest were visually classified (Table 1). No change in classification was allowed once the white light examination had been completed. Under this visual classification system, areas without any visual abnormality were classified as class I. Areas with the appearance of inflammation, trauma, anatomic abnormalities, which could be areas of metaplasia or mild dysplasia, were classified as class II. Areas suggestive of moderate dysplasia, severe dysplasia, or CIS were class III. Appearance of a gross, visible tumor was classified as class IV.

TABLE 1.

Description of Visual Classifications

| Classification | Description | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Class I | Normal: not visually abnormal or suspicious | Negative |

| Class II | Abnormal: appearance of inflammation, trauma, anatomical abnormalities, metaplasia, or mild dysplasia |

Negative |

| Class III | Suspicious for preinvasive cancer: suggestive of moderate dysplasia, severe dysplasia, or carcinoma in situ |

Positive |

| Class IV | Suspicious for invasive cancer: appearance of gross, visible tumor |

Positive |

After WLB, the device was switched to ARB mode and another examination of the airways was performed. Areas of interest were visually classified using the same classification scheme (Table 1). Sites classified as III or IV under ARB but not classified under WLB were automatically defaulted to class I under white light. Still images of all sites of interest were recorded with a digital image capture system under both WLB and ARB. During capture of the still image under ARB mode, the endoscopist tried to center a small target over the most abnormal part of the lesion. A value for the fluorescence-reflectance response based on the red to green light intensity ratio in this area was computed by Onco-LIFE. This value was recorded automatically by the digital image capture system. The bronchoscopist was blinded to this value, because it was not displayed on the video monitor. The visual classification results and recorded fluorescence-reflectance response values were used for comparison with the pathology of the biopsies after the trial had been completed.

After ARB examination, all regions classified as III or IV under either imaging modality were biopsied, as well as at least one class I/II region as a control. Biopsy was acquired under ARB unless the lesion was only visible under WLB. The clinical center’s pathologist, who was blinded to the endoscopic findings, first evaluated the biopsy slide followed by a reference pathologist who was blinded to the previous results. Pathologists coded the biopsy slides based on a 9-point scheme (Table 2). In case of disagreement between center and reference pathologist, slides were reread by the reference pathologist, and these results were taken as final.

TABLE 2.

Pathology Coding

| Pathology Classification |

Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 1.x | Normal |

| 2.x | Inflammation | |

| 3.x | Hyperplasia | |

| 4.x | Mild atypia | |

| Positive | 5.1–5.25 | Moderate atypia |

| 5.3–5.45 | Severe atypia | |

| 6.x | CIS | |

| 7.x | Microinvasive | |

| 8.x | Carcinoma | |

| Unevaluable | 9.x | Unsatisfactory |

CIS, carcinoma in situ.

For analyses using the lesion as the basis of analysis, positive lesions were defined as those with a visual classification of III or IV under WLB and/or ARB and a corresponding biopsy result of moderate/severe dysplasia, CIS, or invasive carcinoma. For analyses using the patient as the unit of analysis, a patient was defined as positive if they had at least one lesion visually classified as class III or IV and a corresponding biopsy result of moderate/severe dysplasia, CIS, or invasive carcinoma for that lesion. For analyses measuring detection of early intraepithelial lesions, the same definitions of positive lesions and patients described above were used, except positive pathology only included moderate/severe dysplasia or CIS.

During the examination, all procedure-relevant data, including adverse effects, was recorded. The subject was followed-up 7 days after bronchoscopy to determine whether any side effects from the procedure were experienced.

Statistical Methods

Statistically unbiased estimates of sensitivity and specificity were not possible to obtain because serial sections of the entire tracheobronchial tree would need to be examined after the bronchoscopic procedures for these to be defined. Nevertheless, because the objective of the study was to determine whether the addition of ARB examination to WLB was better than WLB alone, the relative sensitivity, or the ratio of the sensitivity of WLB + ARB as compared with WLB alone, along with the 95% confidence interval (CI), was calculated to evaluate the contribution of the fluorescence examination to detect neoplastic lesions. A relative sensitivity more than 1 would indicate a significant improvement of WLB + ARB versus WLB alone. Two other statistically unbiased estimates, the positive predictive value and negative predictive value, were also calculated to evaluate the performance.

The statistical analyses were calculated for all the data combined (moderate dysplasia or worse) as well as subsets of the data, such as moderate/severe dysplasia and CIS (intraepithelial neoplasia). The data were analyzed on a per-lesion basis and a per patient basis. For the per-lesion analysis, each biopsy specimen was evaluated and considered positive if the final diagnosis was positive. For the per-patient analysis, each patient was considered positive if he or she had at least one positive lesion (biopsy).

RESULTS

There were 115 men and 55 women with a median age of 62 years (range, 45–75 years). Approximately 99% of subjects were current or former smokers with mean packyears (packs per day × number of years smoked) of ~50. Approximately 15% of subjects had a previous history of lung cancer. A total of 864 biopsy specimens were acquired. Of these, 88 were not evaluable: 84 because of unsatisfactory biopsy specimen from insufficient epithelium for diagnosis, 4 because of lack of matching still image. The final pathologic diagnoses for the remaining 776 biopsy specimens were as follows: normal to mild dysplasia in 700, moderate dysplasia in 33, severe dysplasia in 6, CIS in 2, microinvasive carcinoma in 4, and invasive carcinoma in 31.

Table 3 summarizes efficacy results obtained in this study. A total of 76 lesions were classified as positive (moderate dysplasia or worse) by pathology. Thirty-six of these lesions were detected during WLB examination. An additional 18 were detected by ARB, totaling 52 lesions. Therefore, the relative sensitivity on a per-lesion basis of a WLB + ARB examination versus WLB alone was 1.50 (95% CI, 1.26 –1.89). When the patient was used as the unit of analysis, 24 patients with positive pathology were identified during WLB. An additional eight were identified with ARB totaling 32. Therefore, the relative sensitivity on a per-patient basis was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.13–1.70).

TABLE 3.

Summary of Efficacy Results: Sensitivity

| Moderate Dysplasia or Worse | Moderate/Severe Dysplasia/CIS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit of Analysis |

WLB | WLB + ARB | Relative Sensitivity (95% CI) |

WLB | WLB + ARB | Relative Sensitivity (95% CI) |

| Lesion | 47% | 71% | 1.50 (1.26–1.89) | 10% | 44% | 4.25 (2.00–16.0) |

| Patient | 56% | 74% | 1.33 (1.13–1.70) | 16% | 56% | 3.50 (1.63–12.0) |

CIS, carcinoma in situ; WLB, white light bronchoscopy; ARB, autofluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy; CI, confidence interval.

The data was then analyzed to compare the ability to detect intraepithelial lesions (moderate/severe dysplasia or CIS). Of the 41 intraepithelial lesions, 4 (10%) were detected by WLB. An additional 13 were detected by ARB totaling 17 (44%). Therefore, the relative sensitivity of WLB + ARB versus WLB alone was 4.25 (95% CI, 2.00 –16.00). The specificity of WLB and ARB examination was 94% and 75%, respectively. The ratio of false positive results (i.e., the ratio of 1-specificity) of WLB + AF versus WLB alone for the detection of moderate dysplasia or worse was 3.56. An additional 10 individuals were identified with ARB totaling 14. Therefore, the relative sensitivity was 3.50 (95% CI, 1.63–12.00).

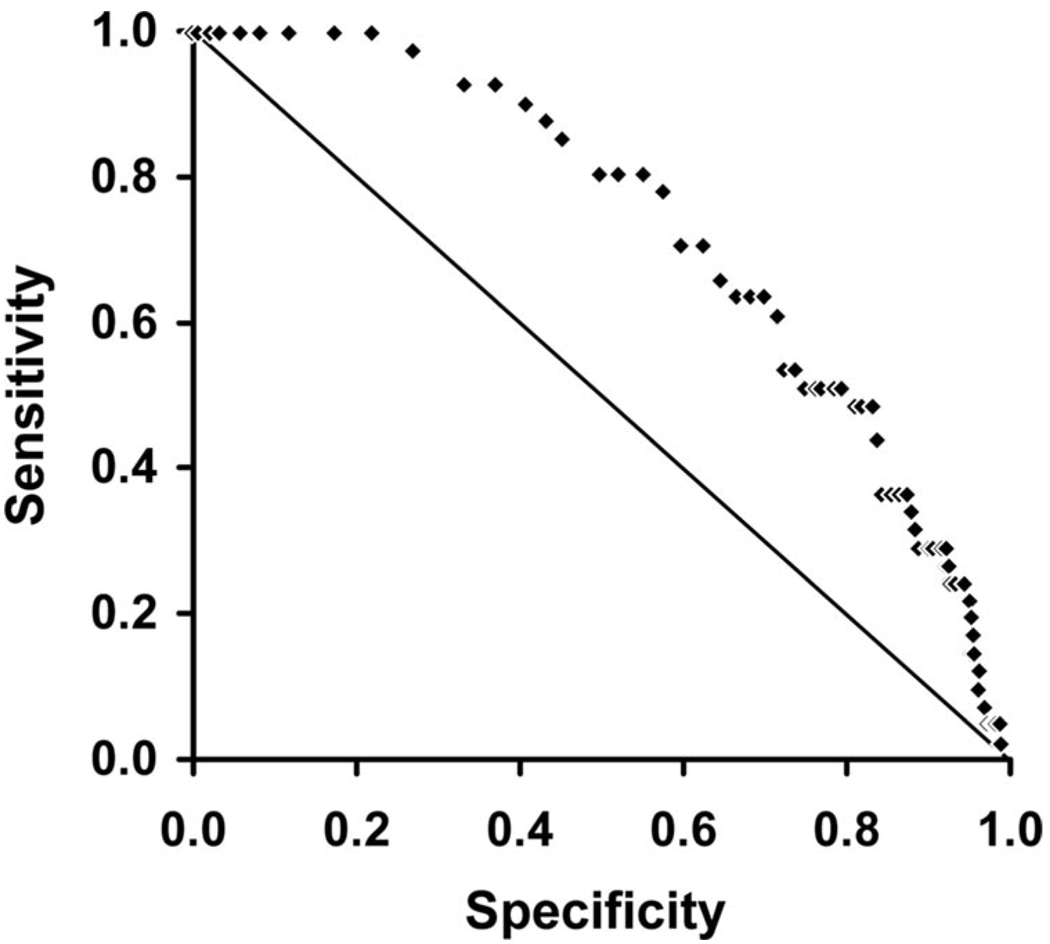

The fluorescence-reflectance response values computed from the red-green light intensity ratios at 710 sites were available for correlation. Sites where the target was not directly over the abnormal part of the lesion were excluded from the analysis. The pathology of the sites included in the analysis was normal/hyperplasia (37), inflammation (3), metaplasia (479), mild dysplasia (150), moderate dysplasia (29), severe dysplasia (8), CIS (1), microinvasive cancer (3). The receiver operating characteristic curve of lesions with moderate dysplasia or worse versus lower grade lesions is shown in Figure 1. The area under the curve is 0.735. Using a value of more than or equal to 0.40 as a threshold, a sensitivity of 51% and a specificity of 80% could be achieved.

FIGURE 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of quantitative imaging using the red-green light intensity ratios measured with a target over the lesion before taking a biopsy.

All 204 patients enrolled were included in the analysis of safety. On average, bronchoscopy, including WLB, ARB, and biopsy acquisition, took 22 minutes. Adverse effects were observed in nine patients. All adverse effects observed were commensurate with bronchoscopy, and none were at-tributable to the Onco-LIFE device. Serious complications include fever and hypoxia resulting in hospitalization in four patients. One patient experienced hypoxia requiring manual ventilation. One individual died after the 7-day follow-up period from pulmonary edema and underlying metastatic small cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of ARB when used as an adjunct to WLB to detect lesions suspicious for intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma using a new AFB bronchoscopy device. Similar to our previous study using autofluorescence alone,9 these results confirm that ARB significantly adds value to a conventional WLB by improving the sensitivity of detection of diseased tissue, especially early stage, intraepithelial neoplasias. The advantage of Onco-LIFE compares to LIFE-Lung is that by using a combination of reflectance and fluorescence, the image quality is improved. The use of a filtered lamp instead of a laser decreases the cost of the device and allows rapid switching between white-light and fluorescence examinations. A similar principle has also been implemented in other devices.29–31

A direct comparative study between white-light bronchoscopy using fiberoptic bronchoscopes as used in the Onco-LIFE system versus charge-coupled device tipped videobronchoscopes has not been performed. A recent study showed that AFB using the LIFE-Lung system was still more sensitive than WLB using state of the art video-bronchoscope in the detection of high grade dysplasia and CIS (96% versus 72%, respectively).25 Studies using videobronchoscope for both white-light and fluorescence examinations instead of fiberoptic bronchoscopes showed similar improvements in detection rates with AFB.30,31

The differences in tissue autofluorescence between healthy and diseased areas visualized using LIFE technology provide new information for the endoscopist to use when assessing the health of the lung. This information has been shown to enhance the physicians’ ability to detect intraepithelial dysplasia or neoplasia, even above and beyond any benefit obtained from improved image resolution obtained with a conventional white light videoscope.27 Since its introduction into the field in 1998, AFB has been used for numerous applications, such as molecular biology studies of lung carcinogenesis, chemoprevention trials, and monitoring areas of field cancerization during intervention of preneoplasia. 32–34 The improved sensitivity provided by AFB has also been used in postinterventional surveillance, such as evaluation of the recurrence of CIS in bronchial resection margins34 and postoperative surveillance of patients with non-small cell lung cancer.19 In addition, AFB has been used to overcome the difficulty WLB has in identifying early mucosal lesions amenable to photodynamic therapy curative therapy.35

As observed in this study, improved sensitivity for the detection of disease obtained through the adjunctive use of AFB is associated with an increase in false positives, resulting in acquisition of more biopsies for evaluation. Nevertheless, the high sensitivity, lower specificity of AFB are commensurate with other imaging modalities, such as computed tomography,36 as well as occult blood testing and mammography. 37 Moreover, it has been suggested that lesions obtained under AFB and denoted as false positives may be from sites carrying molecular genetic lesions associated with malignancy despite their normal histologic appearance.38 Our exploratory study using quantitative imaging suggested that a good sensitivity and specificity could be achieved with computed assisted aid. This approach should be incorporated into future prospective clinical trials.

Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) uses blue light centered at 415 nm and green light centered at 540 nm corresponding to the maximal hemoglobin absorption peaks. The blue light highlights the superficial capillaries, whereas the green light can penetrate deeper and highlight the larger blood vessels in the submucosa. Preliminary studies suggest that NBI can improve detection of dysplasia and CIS compared with WLB.39 A direct comparison between NBI and autofluorescence bronchoscopy has not been done. Some NBI studies use NBI to evaluate localized sites of interest that are detected with AFB.40

The next step in the assessment of the clinical utility of LIFE technology is to evaluate the link between improved detection of disease achievable with this technology and improved long-term patient outcome. Toward this goal, an international Autofluorescence Bronchoscopy Registry for Intraepithelial Neoplasia coordinated by the Rosewell Park Cancer Institute Stacey Scott Lung Cancer Registry is under-way to establish a large database to determine the long-term outcome of patients undergoing AFB.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Xillix® Technologies Corp. supported this investigation, in part. None of the investigators were full or part-time employees of Xillix® Technologies Corp. or had financial interest in the outcome of the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motta G, Carbone E, Spinelli E, Nahum MA, Testa T, Flocchini GP. Considerations about tumor size as a factor of prognosis in NSCLC. Ann Ital Chir. 1999;70:893–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortese DA, Pairolero PC, Bergstralh EJ, et al. Roentgenographically occult lung cancer: a 10-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;86:373–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechtel JJ, Petty TL, Saccomanno G. Five year survival and later outcome of patients with X-ray occult lung cancer detected by sputum cytology. Lung Cancer. 2000;30:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam S, MacAulay C, LeRiche JC, Palcic B. Detection and localization of early lung cancer by fluorescence bronchoscopy. Cancer. 2000;89:2468–2473. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11+<2468::aid-cncr25>3.3.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Facts & Figures 2005. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolner LB, Fontana RS, Cortese DA, et al. Roentgenographically occult lung cancer: pathologic findings and frequency of multicentricity during a 10-year period. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:453–466. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam S, Kennedy T, Unger M, et al. Localization of bronchial intraepithelial neoplastic lesions by fluorescence bronchoscopy. Chest. 1998;113:696–702. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palcic B, Lam S, Hung J, MacAulay C. Detection and localization of early lung cancer by imaging techniques. Chest. 1991;99:742–743. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung J, Lam S, LeRiche JC, Palcic B. Autofluorescence of normal and malignant bronchial tissue. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:99–105. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam S, MacAulay C, Hung J, LeRiche J, Profio AE, Palcic B. Detection of dysplasia and carcinoma in situ using a lung imaging fluorescence endoscopy (LIFE) device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:1035–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam S, MacAulay C, leRiche JC, Ikeda N, Palcic B. Early localization of bronchogenic carcinoma. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1994;1:75–78. doi: 10.1155/DTE.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rens MT, Schramel FM, Elbers JR, Lammers JW. The clinical value of lung imaging fluorescence endoscope for detecting synchronous lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2001;32:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiberville L, Sutedga T, Vandershueren R, et al. A multicenter European study using the lung fluorescence endoscopy system to detect precancerous lesions of the bronchus in high risk individuals. Eur Respir J. 1999;S30:247S. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thieberville L, Calduk H, Metayer J, Dominique S, Labbe D, Nouvet G. Auto-fluorescence versus white light endoscopy: improvement in preinvasive lesions detection and false positive images. Eur Respir J. 1996;S23:11S. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch FR, Prindiville SA, Miller YE, et al. Fluorescence versus white light bronchoscopy for detection of preneoplastic lesions: a randomized study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1385–1391. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.18.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusunoki Y, Imamura F, Uda H, Mano M, Horai T. Early detection of lung cancer with laser-induced fluorescence endoscopy and spectrofluometry. Chest. 2000;118:1776–1782. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.6.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weigel TL, Kosco PJ, Dacic S, Rusch VW, Ginsberg RJ, Luketich JD. Postoperative fluorescence bronchoscopic surveillance in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:967–970. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato M, Sakurada A, Sagawa M, et al. Diagnostic results before and after introduction of autofluorescence bronchoscopy in patients suspected of having lung cancer detected by sputum cytology in lung cancer mass screening. Lung Cancer. 2001;32:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venmans BJ, Van Boxem TJ, Smit EF, Postmus PE, Sutedja TG. Results of two years experience with fluorescence bronchoscopy in detection of preinvaisve bronchial neoplasia. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1999;5:77–84. doi: 10.1155/DTE.5.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermylen P, Pierard P, Roufosse C, et al. Detection of bronchial preneoplastic lesions and early lung cancer with fluorescence bronchoscopy: a study about its ambulatory feasibility under local anaesthesis. Lung Cancer. 1999;25:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee F, Ng AWK, Wang YT. Early detection of lung cancer with the LIFE laser [abstract] Chest. 1995;108 poster discussions. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khanavkar B, Gnudi F, Muti A, et al. Basic principles of LIFE-autofluorescence bronchoscopy. Pneumologie. 1998;52:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dal Fante M, De Paoli F, Pilotti S, Spinelli P. Fluorescence bronchos-copy in early detection of lung cancer [abstract] Eur J Cancer. 1996;32:S8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierard P, Martin B, Verdebout J-M, et al. Fluorescence bronchoscopy in high-risk patients—a comparison of LIFE and Pentax systems. J Bronchol. 2001;8:254–259. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chhajed PN, Shibuya K, Hoshino H, et al. A comparison of video and autofluorescence bronchoscopy in patients at high risk of lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:951–955. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00012504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ernst A, Simoff MJ, Mathur PN, Yung RC, Beamis JF., Jr D-Light autofluorescence in the detection of premalignant airway changes: a multicenter trial. J Bronchol. 2005;12:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haussinger K, Becker H, Stanzel F, et al. Autofluorescence bronchoscopy with white light bronchoscopy compared with white light bronchoscopy alone for the detection of precancerous lesions: a European randomised controlled multicentre trial. Thorax. 2005;60:496–503. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda N, Honda H, Hayashi A, et al. Early detection of bronchial lesions using newly developed videoendoscopy-based autofluorescence bronchoscopy. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiyo M, Shibuya K, Hoshino H, et al. Effective detection of bronchial preinvasive lesions by a new autofluorescence imaging bronchovideoscope system. Lung Cancer. 2005;48:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiberville L, Payne P, Vielkinds J, et al. Evidence of cumulative gene losses with progression of premalignant epithelial lesions to carcinoma of the bronchus. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5133–5139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam S, MacAulay C, leRiche JC, et al. A randomized phase IIb trial of anethole dithiolethione in smokers with bronchial dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1001–1009. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasic A, Grunberg K, Mooi JJ, Paul MA, Postmus PE, Sutedja TG. The natural history of carcinoma in situ involving bronchial resection margins. Chest. 2005;128:1736–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weigel T, Shatzer M, Maple M, Luketich J. LIFE bronchoscopy: a promising new tool to monitor for recurrence after curative, photodynamic therapy of early non-small cell lung carcinoma [abstract] Chest. 1998;114(4S):403. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelvitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354:99–105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy T, Lam S, Hirsch FR. Review of recent advances in fluorescence bronchoscopy in early localization of central airway lung cancer. Oncologist. 2001;6:257–262. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-3-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helfritzsch H, Junker K, Bartel M, Scheele J. Differentiation of positive autofluorescence bronchoscopy findings by comparative genomic hybridization. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vincent BD, Fraig M, Silvestri GA. A pilot study of Narrow Band Imaging compared to white light bronchoscopy for evaluation of normal airways and premalignant and malignant airways disease. Chest. 2007;131:1794–1799. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibuya K, Hoshino H, Chiyo M, et al. High magnification bronchovideoscopy combined with Narrow Band Imaging could detect capillary loops of angiogenic squamous dysplasia in heavy smokers at high risk for lung cancer. Thorax. 2003;58:989–995. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.11.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]