Abstract

The optimization of digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) geometry and reconstruction is crucial for the clinical translation of this exciting new imaging technique. In the present work, the authors developed a three-dimensional (3D) cascaded linear system model for DBT to investigate the effects of detector performance, imaging geometry, and image reconstruction algorithm on the reconstructed image quality. The characteristics of a prototype DBT system equipped with an amorphous selenium flat-panel detector and filtered backprojection reconstruction were used as an example in the implementation of the linear system model. The propagation of signal and noise in the frequency domain was divided into six cascaded stages incorporating the detector performance, imaging geometry, and reconstruction filters. The reconstructed tomosynthesis imaging quality was characterized by spatial frequency dependent presampling modulation transfer function (MTF), noise power spectrum (NPS), and detective quantum efficiency (DQE) in 3D. The results showed that both MTF and NPS were affected by the angular range of the tomosynthesis scan and the reconstruction filters. For image planes parallel to the detector (in-plane), MTF at low frequencies was improved with increase in angular range. The shape of the NPS was affected by the reconstruction filters. Noise aliasing in 3D could be introduced by insufficient voxel sampling, especially in the z (slice-thickness) direction where the sampling distance (slice thickness) could be more than ten times that for in-plane images. Aliasing increases the noise at high frequencies, which causes degradation in DQE. Application of a reconstruction filter that limits the frequency components beyond the Nyquist frequency in the z direction, referred to as the slice thickness filter, eliminates noise aliasing and improves 3D DQE. The focal spot blur, which arises from continuous tube travel during tomosynthesis acquisition, could degrade DQE significantly because it introduces correlation in signal only, not NPS.

Keywords: amorphous selenium, breast imaging, flat-panel detector, tomosynthesis, linear system model, NPS, MTF, DQE, focal spot blur

INTRODUCTION

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is an emerging three-dimensional (3D) imaging technique for early detection of breast cancer. Phantom as well as clinical images have shown that DBT can improve lesion conspicuity compared to projection mammography by removing the obscuring effects of overlapping breast tissue.1 DBT is being investigated intensively as an imaging technique for both screening and diagnosis.2, 3, 4 Due to incomplete data sampling in tomosynthesis, many research efforts have been focused on the comparison between different reconstruction algorithms, both analytical5, 6, 7 and iterative.8, 9 It has been shown that with proper choice of reconstruction filters, filtered backprojection (FBP) reconstruction can produce satisfactory clinical images.10 In fact, FBP based algorithms are currently used in clinical prototype systems manufactured by both Hologic3 and Siemens,4 including the system used in our studies.

DBT systems are usually modified from existing screening mammography systems by adding tube motion. The performance of digital mammography detectors was improved to accommodate the increased acquisition speed and lower radiation dose (per view) used in tomosynthesis. The image quality of DBT is affected by many factors including angular range, number of views, detector performance, and reconstruction filters. Several studies have been published on tomosynthesis image quality. Wu et al. used the objects in an ACR phantom to study the effects of angular range and view number.1 Ren et al. investigated the dependence of in-plane resolution on inherent detector performance and focal spot blur (FSB).3 We built a computer simulation platform for DBT to investigate the effects of system geometry, detector performance, and reconstruction algorithms.11 The image quality was evaluated using contrast to noise ratio and in-plane modular transfer function (MTF) of reconstructed, simulated objects. Chen et al. measured and compared the image noise and resolution using in-plane image slices for several reconstruction algorithms.12 However, most studies used objects with mixed frequency components, and the evaluation was based on in-plane images only, i.e., 1D or 2D frequency domain.3, 6, 9 It is difficult to fully reveal the effects of imaging geometry because DBT uses a limited angular range, and the reconstructed images are highly anisotropic. Hence, it is important to develop 3D analysis methods.

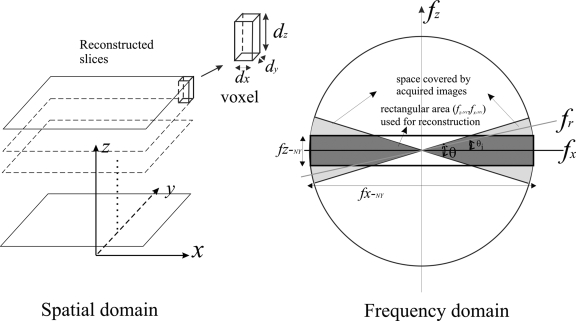

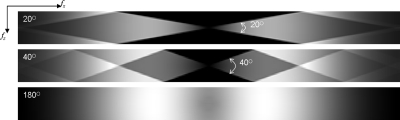

The goal of the present work is to build a 3D linear system analysis framework for DBT. Cascaded linear system models have been used extensively to study the performance of digital detectors in the context of projection imaging.13, 14 The theoretical foundation of noise power spectrum (NPS) analysis in 3D has been established for computed tomography (CT),15, 16 and more recently for cone beam CT (CBCT).17, 18 With linear reconstruction algorithms, e.g., FBP, linear system analysis can be applied to tomosynthesis and facilitate the understanding of the effects of system geometry, detector performance, and reconstruction filters on the image quality of reconstructed tomosynthesis slices. Compared with CBCT, tomosynthesis is performed with limited angular range (<50°) and number of views (typically <30). Due to incomplete data sampling, the images are reconstructed using anisotropic voxel size, with in-plane (parallel to detector surface) pixel size dx and dy comparable to that of the projection images, and in-depth dimension dz of 1 mm. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the reconstructed image space and the frequency domain in tomosynthesis. In tomosynthesis only the shaded area with an angular range of θ is sampled in the frequency domain.

Figure 1.

Diagrams showing the data sampling of the reconstructed images for DBT in the spatial domain (left) and spatial frequency domain (right). The area shaded in light gray with an angular range of θ shows the sampled frequency range as determined by the central slice theorem. The area shaded in darker gray indicates the frequency range below the Nyquist frequencies in both the x (tube travel) and z (slice thickness) directions. As described later in the article, frequency limiting filters, such as the slice thickness filter, can be applied in the FBP process to minimize aliasing in the reconstruction process.

In Sec. 2 of this article, we will first describe briefly a well-developed and verified cascaded linear system model for amorphous selenium (a-Se) flat-panel detectors, which forms the basis for the determination of signal and NPS of the projection images in the 3D model. Then we will describe the unique modification of the projection spectra in tomosynthesis, which is the additional blur in the tube travel direction (x) due to focal spot motion. Finally, we will extend the model to 3D and apply the reconstruction filters and backprojection process. In Sec. 3, we will present the modeled results of NPS, presampling MTF and detective quantum efficiency (DQE) in 3D. The relationship between 3D and in-plane imaging characteristics, as well as its dependence on imaging geometry, will be discussed.

THEORY

Our model is based on a linear system approximation for DBT, i.e., stationary and shift-invariant. The linear system assumption for a-Se detector in the projection domain has been described in detail previously.13 In the context of tomosynthesis reconstruction, a parallel beam approximation and FBP algorithm were used, similar to that used in linear system analysis of cone-beam CT. Several DBT system parameters affect the linear system assumption: (1) cone beam projection, which results in different magnification for object located at different planes; (2) stationary detector, which results in angular dependence in detector resolution due to oblique entry of x rays and difference in equivalent pixel spacing; and (3) continuous tube travel during exposure, which results in an additional focal spot blur that depends on the location of the object. Since in the DBT system the breast is compressed directly onto the surface of the detector, the magnification due to cone-beam projection is minimal. The maximum tube angle of the DBT acquisition is ∼20°, with corresponding cosine value of ∼0.94. It has been shown that the effect of this small angular range on the frequency response of the stationary detector was not the dominant factor for the MTF. Although a DBT system is not strictly linear, the cascaded linear system model could provide an estimate of the average performance of different image slice. The position dependence of a DBT imaging performance and its comparison with modeled results are presented in a separate publication.19

Here, we consider an example of DBT system that has been described previously.20 It is equipped with an a-Se detector with 85 μm pixel size. The source-to-imager distance is 65 cm. The x-ray tube travels continuously in an arc with a center of rotation (COR) that is 4.5 cm above the detector cover, which is 1.5 cm from the a-Se surface. For each tomosynthesis scan, N projection images are acquired within an angular range θ. The nominal value for θ is 40° (±20°), with maximum N=49. The actual angular position of the x-ray tube at the beginning of radiation exposure for each view was measured with an inclinometer mounted in the tube housing (MicroStrain, Inc., VT), which measures the tilt angle of the x-ray tube column with respect to gravity. The angular position measurements were saved in a parameter file and used later to set up the accurate geometry for image reconstruction. To keep scan time within 20 s, N⩽25 was usually used. A harder mammography energy spectrum with target∕filter combination of tungsten (W)∕rhodium (Rh) with nominal Rh thickness of 50 μm was preferred over molybdenum (Mo) spectrum to maximize the signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio in tomosynthesis.21 Since the detector performance and FSB due to tube travel depends on operational modes and dose in DBT acquisition, the parameters used in our model is based on those listed in Table 1. A total exposure of 144 mA s at 28 kVp was assumed, which corresponds to an average glandular dose of 1.5 mGy for a 4.2 cm average breast. The average detector entrance exposure after attenuation by the breast is 1.18 mR per view with 25 views.

Table 1.

Imaging system parameters used in the linear system model.

| Detector parameters | Pixel size: ax=ay=85 μm Nyquist frequency fr-NY: 5.88 cycles∕mm |

| X-ray spectrum | Target∕filter: W∕Rh Tube potential: 28 kVp |

| Imaging mode | Nominal angular range: ±20° (gantry rotation in x-z plane) View number: 25 Scan time: 20.8 s Total exposure: 144 mA s |

| Reconstruction | Algorithm: FBP Reconstructed voxel size (dx, dy, dz): 0.085×0.085×1 mm3 |

FBP methods were used to reconstruct 1 mm thick image slices that are parallel to the stationary detector. The pixel size for each reconstructed in-plane image could be as small as the detector pixel size, i.e., 85 μm. Therefore, the reconstructed voxel is highly anisotropic, with dimension of 0.085×0.085×1 mm3. As shown in Fig. 1, the axes of the imaging system are defined as follows: The x-y plane defines the reconstructed planes parallel to the detector, with the x axis representing the tube travel direction. The z axis is perpendicular to the detector plane. For the remainder of this article, the x-y plane is referred to as the “in-plane,” and the x-z plane, which corresponds to the cross-sectional plane in CT, is referred to as the “in-depth” plane. The frequency domain variables shown in Fig. 1 are defined as follows: fx and fz are the Cartesian coordinates for the spatial frequencies in the x and z directions; fr and θi are the polar coordinates, where fr is the radial frequency and θi is the angle. According to central slice theorem,22 the projection image taken at angle θi fills the frequency space along the same angle, and the frequency response of the projection image corresponds to the radial frequency fr along θi. The polar coordinates are related to the Cartesian coordinates of the reconstructed image through

| (1) |

Detector cascaded linear system model

The detector parameters for the a-Se flat-panel digital mammography detector (LMAM, Anrad Corporation, Canada) were used as an example in our model development.23 The detector has a pixel size of 85 μm and a-Se layer thickness of 200 μm. Previously, we have developed and validated a cascaded linear model for the detector.13, 24, 25 The model can be used to predict the detector performance, in the form of MTF, NPS, and DQE as a function of detector parameters and x-ray exposures. The output of this model, which will be used as the input for further stages in tomosynthesis, consists of the signal spectrum Φp and noise power spectrum Sp. They are related to the detector presampling MTF and DQE through

| (2) |

where q0 is the number of incident x-ray quanta per projection view and k is the pixel response of the detector for a given exposure.

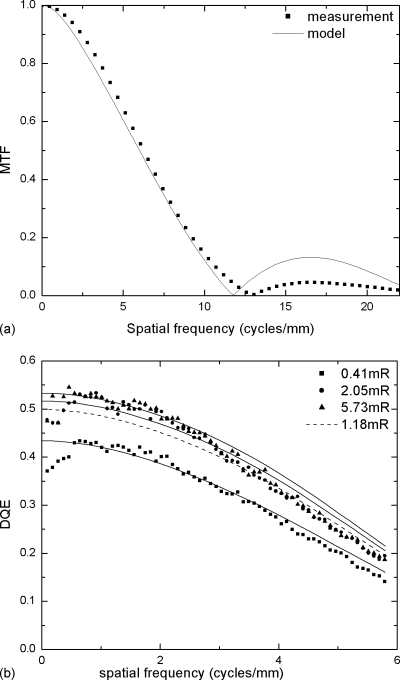

It was found previously that image correction could introduce additional noise to the images and result in a DQE that is lower than predicted by the model.23 Degradation of MTF and DQE could also result from scatter within the detector. Since the main focus of the present investigation is to extend the 2D model to 3D, as opposed to the development of the 2D model itself, we chose to modify the detector parameters in the existing 2D model to match the measured performance of a-Se flat-panel detector as that shown in Fig. 2.20 The following detector parameters in the model were varied until the measured and calculated MTF and DQE at different exposure levels have reasonable agreement: (1) the x-ray-to-charge conversion of a-Se, i.e., the energy W required to generate an electron hole pair; (2) the thickness of the top blocking layer for a-Se, which absorbs x rays but does not contribute to signal due to the limited range of free carriers; and (3) the electronic noise ne, usually given in number of electrons per pixel. The modeled results shown in Fig. 2 agree reasonably well with the measured MTF and DQE. The corresponding detector parameters are W=50 eV, thickness of 22 μm for the top blocking layer, and electronic noise ne=2000 electrons∕pixel. It is important to note that the modeled top blocking layer thickness is significantly larger than the real value used in the detector. It is increased to account for the additional drop in DQE due to image correction and other factors that are not accounted for in the detector model.

Figure 2.

Comparison between measured and modeled detector performance for an a-Se digital detector with 85 μm pixel size used in breast tomosynthesis: (a) MTF and (b) DQE.

Figure 2b shows that at 1.18 mR, which corresponds to the detector exposure per view (with 25 views) in DBT for an average 4 cm breast, DQE(0) is ∼0.5. There is no significant degradation by electronic noise from the maximum values measured at higher exposures.

3D model development for tomosynthesis

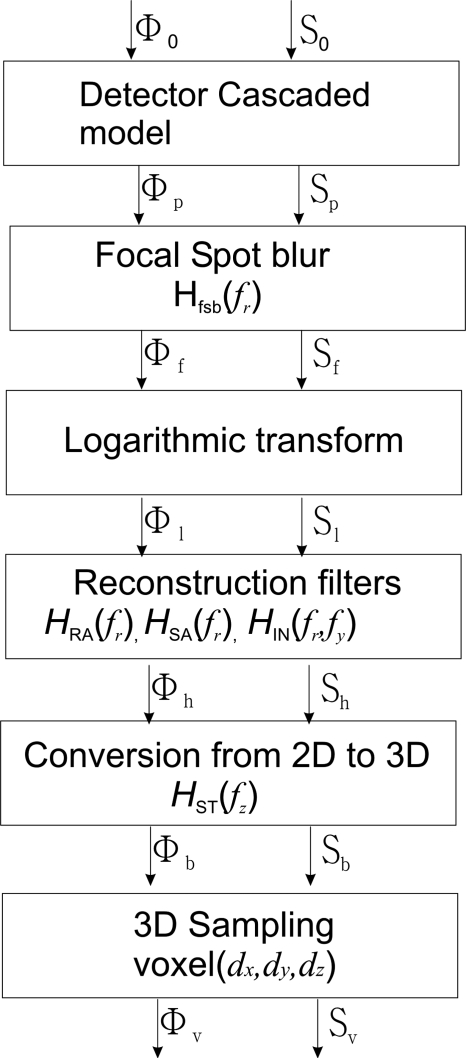

Figure 3 shows the flow chart of the 3D cascaded linear system model for tomosynthesis. The output spectra, Φp, and Sp, of the existing detector cascaded model are propagated through five more stages that are unique for tomosynthesis acquisition and reconstruction: (1) additional FSB due to focal spot motion, which is in the tube travel direction only; (2) logarithmic transformation on projection images; (3) reconstruction filters applied to the resulting projection images; (4) conversion and mapping of the 2D spectra along the projection angle within the limited angular range; and (5) 3D sampling according to the anisotropic voxel size, which introduces noise aliasing above the Nyquist frequencies in each direction. The output spectra for each stage are denoted by the subscripts of the signal spectrum Φ and noise power spectrum S, as defined in Fig. 3. Now we will describe separately the propagation of signal and noise spectra through each of the five stages.

Figure 3.

Flow chart for signal and noise propagation in the cascaded linear system model.

Focal spot blur

In a cascaded linear system model, FSB is usually implemented as a stage after the x-ray absorption and before the x-ray to charge conversion gain. In projection mammography, FSB is usually negligible due to the small focal spot and minimal magnification. To separate the effects of intrinsic detector parameters and extrinsic factors such as focal spot motion in tomosynthesis, in the present model the additional FSB caused by tube motion was implemented after the intrinsic detector model (described in Sec. 2A). Because FSB introduces a multiplicative factor to the MTF and does not affect the NPS,13 the results should be equivalent to the original linear system approach. Since this additional FSB is only in the tube travel direction, i.e., along θi direction of each projection image. The output signal and noise power spectra after FSB, which has a blur function of HFSB(f), is given by

| (3) |

FSB due to continuous tube motion during tomosynthesis acquisition could be significant.3, 4, 26HFSB(f) is given by the product of two aperture functions: (1) the finite focal spot size a0; and (2) focal spot travel distance a1 during the x-ray exposure of each view. Since a1⪢a0, HFSB(f) is simplified to a single aperture function and applied to fr along each θi direction

| (4) |

Although the implementation of our DBT linear system model assumes isocentric tomographic geometry for filter application and backprojection, HFSB(f) for a stationary detector DBT system is more severe.26 This is because the relative motion of the source is much smaller with isocentric geometry. There is essentially no FSB at the COR plane, and the FSB increases as the distance from the COR increases. With a stationary detector, FSB exists throughout the breast volume, and the effect of the focal spot motion on the projection image increases with the magnification of the plane of interest. To include the worst case scenario, the FSB for a prototype DBT system with stationary detector is adopted for HFSB(f) in our model. Due to the variation in magnification as a function of distance from the detector, HFSB(f) is position dependent. For simplicity, HFSB(f) was calculated for tube angle θ=0 and d=4 cm above the detector surface. The focal spot travel distance during each view in the tomosynthesis acquisition for x-ray parameters listed in Table 1 is 0.8 mm, resulting in a1=0.075 mm if the detector is stationary during x-ray exposure.

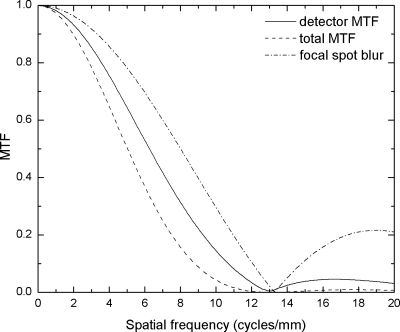

Plotted in Fig. 4 is the calculated HFSB(f) in comparison with the detector presampling MTF and the total MTF. It shows that the intrinsic detector MTF dominates the total MTF, and FSB causes an additional drop of 30% at the Nyquist frequency in the r direction, fr-NY (5.88 cycles∕mm). Consequently this will cause a decrease in 3D MTF and DQE for the reconstructed images as will be shown in Sec. 3. The total MTF with FSB shown in Fig. 4 was used in the 3D model for projection MTF in the x direction.

Figure 4.

Modeled presampling MTF curves to show the effect of FSB. The image acquisition parameters are shown in Table 1. The FSB was calculated for a DBT system with a stationary detector.

Logarithmic transformation

Logarithmic transformation was applied to each projection image to yield the line integral of x-ray attenuation prior to FBP reconstruction. Although this transformation is not a linear process, it can be considered linear within a small range of exposure. This is applicable for low-contrast objects. As shown in the Appendix, the output signal and noise power spectra are propagated through a gain stage, and can be written as

| (5) |

where k is the pixel response of the detector at a given exposure. Neither MTF nor DQE is affected by this process.

Reconstruction filters

During image reconstruction several filters are applied, which modify the signal and noise power spectra of the projection images as deterministic blur. These filters include: (1) ramp (RA) filter HRA, applied in the scan (r) direction of the projection image only; (2) spectrum apodization (SA) filter HSA, applied in the scan (r) direction only; (3) slice thickness (ST) filter HST, applied in the z direction, and (4) interpolation (IN) filter HIN, applied in both the r and y directions. It is important to note that in a DBT geometry where the detector stays stationary while the tube moves in an arc, the filtered projection image at each angle θi does not correspond to the same fr response, but differs by the inverse of cos (θi). However, this factor was ignored in our model to facilitate the comparison between DBT and CT. As shown by Wu et al., this factor is negligible with a DBT angular range of ±20°.1

The RA filter is given by5

| (6) |

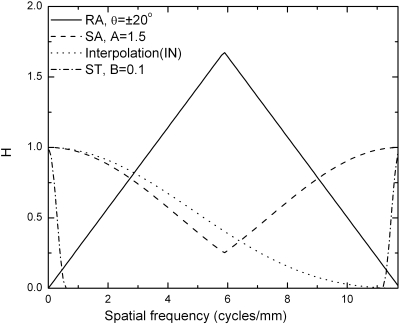

where θ is the angular range of the tomosynthesis acquisition. For ∣fr∣>fr-NY, the RA filter replicates at multiples of 2fr-NY. Shown in Fig. 5 is the RA filter used in the present investigation. Since the amplitude of the filter is dependent on θ, the magnitude of NPS is scaled by tan2(θ).

Figure 5.

Reconstruction filters plotted as a function of spatial frequency for full detector resolution, which corresponds to fNY=5.88 cycles∕mm. The angular range is ±20°, and the filter parameters are listed in Table 2.

The purpose of the SA and ST filters is to limit the bandwidth of the projection data and reduce noise and aliasing. In our implementation, both SA and ST filters use a Hanning window function given by H(f)=0.5[1+cos(πf∕Wf)], where Wf defines the width of the Hanning window, i.e., the lowest spatial frequency at which the value of H(f) decreases to zero. Wf is given in multiples of fNY of the projection images, and the multiplicative factors for the SA and ST filters are denoted A and B, respectively. The SA filter is applied in the tube travel direction of the image, i.e., along the r axis for each θi, and the 1D Hanning window function is given as

| (7) |

For ∣fr∣>fr-NY, the SA filter replicates at multiples of 2fr-NY and the maximum amplitude is unity. In the present study, A=1.5 was selected, which results in HSA(fr-NY)=0.25.

The ST filter is applied in the z direction only and will be incorporated in stage 4 when the 2D information is transferred to 3D. The ST filter (HST) with relative window width B is given by a Hanning window function

| (8) |

where fz=fr sin(θi). The ST filter presents 1D function of fz. A detailed discussion of the ST filter was provided in Refs. 5, 11. During reconstruction the ST filter is implemented on each projection image (with angle θi) individually by multiplication in the frequency domain. The difference of the ST from the SA filter is that the modulation to the projection image is both frequency and angle dependent.

Because voxel driven backprojection was used in the reconstruction, a bilinear interpolation filter HIN was applied in both the r and y directions. The filter function, HIN(fr,fy), associated with bilinear interpolation is a sinc2 function and is related to the pixel size in the r and y directions through

| (9) |

where dx and dy are the pixel dimensions of the projection image (as shown in Table 1).

To investigate the effect of filter functions, four different filter schemes, as summarized in Table 2, were incorporated in the model: (1) simple backprojection (SBP) reconstruction without any filters; (2) RA filter only; (3) RA and SA (A=1.5) filters, and (4) RA, SA and ST filters (B=0.1). HIN was applied in all schemes because voxel driven backprojection was used throughout the reconstruction. An explanation for the choice of B value will be provided in the description of stage 5 (3D sampling).

Table 2.

Summary of the four filter schemes used in reconstruction.

| Filter scheme 1 | SBP reconstruction |

| Filter scheme 2 | HRA only |

| Filter scheme 3 | HRA×HSA (A=1.5) |

| Filter scheme 4 | HRA×HSA (A=1.5)×HST(B=0.1) |

The frequency response curves of different filters are shown in Fig. 5. The RA filter, which increases linearly with frequency, reduces low frequency response of the projection images. Both the SA and IN filters reduce the high frequency response, resulting in a combined response of 0.1 at fr-NY. However, in the y direction, the IN filter is the only means to reduce high frequency response.

After propagation through all the filter functions, the signal and noise power spectra became

| (10) |

Conversion from 2D to 3D

The filtered signal and noise power spectra for each projection image at angular position θi are mapped into the 3D space using the central slice theorem, similar to the method used for CT.15 The difference is that in CT backprojection extends 1D spectra to 2D,15, 16, 27 whereas in tomosynthesis, just like in CBCT,18 the spectra are extended from 2D to 3D. For tomosynthesis acquisition with angular range θ and view number N, the output 3D signal spectrum Φb, signal power spectrum Ψb, and noise power spectrum Sb can be calculated using15

| (11) |

where δ[fx sin(θi)−fz cos(θi)] is incorporated to map the spectra of each projection image along angle θi into the 3D frequency domain. It represents the “spoke” along θi in the polar coordinate (Fig. 1). The signal power spectrum Ψb is listed as a separate parameter to facilitate the calculation of DQE. It is given by and is similar to the variable defined as “deterministic NPS” in the work of Siewerdsen and Jaffray18 When converting the 3D spectra in Eq. 11 from polar coordinates to Cartesian coordinates, the values should be normalized by the “spoke density,” which follows 1∕fr. This aspect has been explained in detail for the derivation of NPS in CT.16, 28

In CT and CBCT, more than 300 views are usually acquired with a full angular range of θ=360 deg (or 180 deg plus the cone angle as a minimum), resulting in an angular sampling interval of θ∕N of ∼1° or less. The propagation of presampling signal and noise power spectra are given by16, 28

| (12) |

where N∕θfr is the spoke density. Since in CT the result of reconstruction is normalized by the view number N to obtain the linear attenuation coefficients, the signal and noise power spectra are normalized accordingly.

The normalization factors for DBT were determined based on Eq. 12 as

| (13) |

The image value for each voxel in our FBP reconstruction was not normalized by the view number N since DBT does not provide accurate reconstruction of the linear attenuation coefficients of materials due to the limited angle. Compared with CT and CBCT, the angular sampling interval is usually larger in DBT, ranging from 1°–3°, e.g. 1.8° for 25 views with θ=±20°. In the present investigation, our model predicts the average system performance assuming sufficiently small angular sampling interval. We found this assumption to be reasonable for angular separation of <2° between views. In the limit of large angular separation, streaks will appear in the NPS (x-z plane). This factor is ignored in our model, which generates smooth curves.

3D sampling

The 3D sampling associated with finite voxel spacing in the backprojection process is the final stage of our cascaded linear system model. The 3D NPS is replicated at multiples of 2fNY in each direction. Noise aliasing is introduced in this stage and the output aliased NPS, Sv, is given by

| (14) |

The Nyquist frequencies in each direction is determined by the voxel dimension dx=dy=0.085 mm, and dz=1 mm.

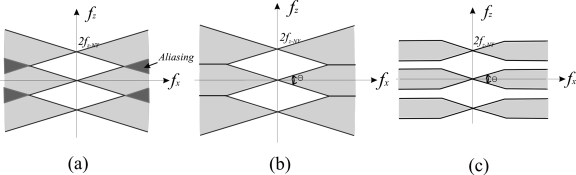

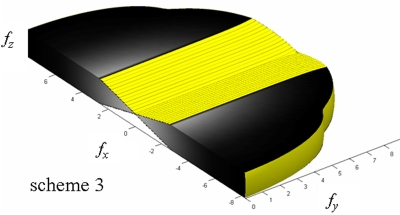

With the large voxel dimension in the z direction, aliasing would be significant without the application of ST filter, as shown in Fig. 6a. The information beyond fz-NY replicates at 2fz-NY and folds back to below fz-NY, which causes aliasing in the z direction (in darker gray). The ST filter, which limits the frequency component beyond fz-NY, prevents noise aliasing [Figs. 6b, 6c]. B=0.085 corresponds to a Hanning window width of fz-NY=0.5 cycles∕mm and completely eliminates noise aliasing. By varying B value or choosing different filter functions, an optimal compromise can be achieved between the detection of small objects (high frequency) and the reduction of noise aliasing. For the present article, B=0.1 was selected because the Hanning window decreases abruptly when approaching the window width. The slightly larger B value helps preserve high frequency information without significant increase in noise aliasing. The response of the ST filter is 10% at fz-NY.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagrams showing the aliased NPS after backprojection: (a) without ST filter; (b) with ST filter (B=0.085); and (c) with ST filter (B<0.085). The frequency space shown in white is not sampled by DBT, the area shaded in light gray is the sampled frequency space, and the area shaded in darker gray has NPS aliasing.

3D NPS, MTF, and detective quantum efficiency

The final 3D NPS, MTF, and DQE can be obtained from the signal and noise power spectra propagated through the cascaded stages. Due to the coarse z-direction sampling, the reconstructed DBT volume are usually viewed as a sequence of in-plane images parallel to the detector by the radiologists or computer-aided detection algorithms.29 Therefore, the image quality metrics for in-plane images, including MTF and NPS were also derived from the 3D parameters.

NPS

The final 3D aliased NPS was obtained directly from the output of the cascaded process [Sv in Eq. 14]. The in-plane (i.e., x-y plane) NPS, Sin-plane, was calculated by integrating Sv along the z axis

| (15) |

MTF

The presampling 3D MTF (Tb) was obtained by normalizing the output signal spectrum

| (16) |

In previous DBT studies, the resolution was usually investigated by placing a thin edge, a wire, or a slit phantom in a particular plane, and deriving the 1D MTF from the in-plane image.11, 30, 31 In a 3D perspective, these phantoms have infinitesimal dimension in the z direction. To predict the in-plane MTF measured using this method, the 3D MTF was aliased and then integrated in the z direction as

| (17) |

where Tv is the aliased MTF. This method of in-plane MTF calculation assumes that the phantom is placed at the center of the slice, and it provides the maximum MTF achievable for in-plane MTF measurement.32, 33 It is important to point out that the integral of the aliased MTF within ±fz-NY is equivalent to the integral of the presampling MTF over all fz.

DQE

The 3D DQE was calculated as the ratio between the squared 3D SNR at the output and that at the input,34

| (18) |

where q0 is the number of incident photons per unit area per view.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

NPS

3D NPS

From the above theory of linear system analysis, 3D NPS in DBT is affected by the following factors according to our model: (1) the aliased NPS of projection images, which has been included in the detector model; (2) reconstruction filters H(f); (3) angular range of DBT acquisition; and (4) 3D sampling and noise aliasing in the backprojection process. In this section, the effects of the last three factors will be discussed.

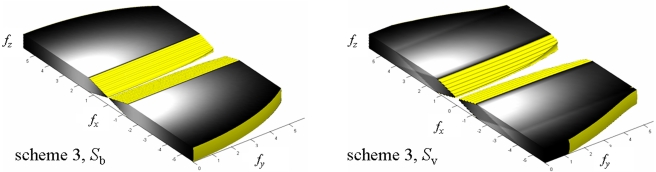

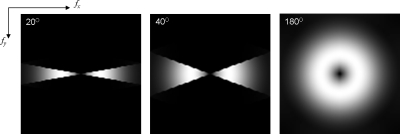

Figure 7 shows the NPS before and after 3D noise aliasing, Sb and Sv, respectively, for filter scheme 3. The results are plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=fy-NY=5.88 cycles∕mm, fz-NY=0.5 cycles∕mm). The gray scale of the NPS images was chosen to display the maximum contrast. The shape of the NPS in the y direction is due to the interpolation filter only. The aliasing of the NPS at high frequencies is clearly visible in Sv. To facilitate comparison, the aliased in-depth NPS are replotted in Fig. 8.

Figure 7.

3D NPS before (Sb) and after (Sv) aliasing reconstructed with scheme 3. The NPS is plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=fy-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm and fz-NY=±0.5 cycles∕mm). Half of the y axis is plotted. Lighter shade indicates higher noise intensity.

Figure 8.

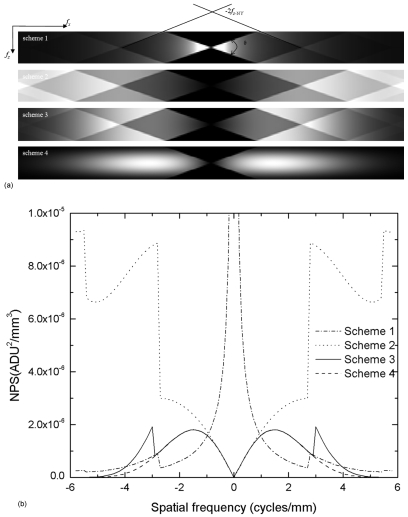

(a) In-depth NPS (at fy=0) for schemes 1–4 with angular range of ±20°. The NPS is plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm and fz-NY=±0.5 cycles∕mm). (b) In-depth NPS at fz=0 for filter schemes 1–4. Angular range=±20°.

Figure 8a shows the aliased in-depth NPS, i.e., the 2D slice of the 3D Sv at fy=0, for all four filter schemes. The NPS are plotted up to fNY in each direction. Due to the limited angular range (±20°), only a fraction of the spatial frequency space is filled and the remainder is not sampled, seen as black triangles in the center. Due to 3D sampling, the NPS is replicated at multiples of 2fz-NY (1 cycles∕mm) and 2fx-NY, which introduces noise aliasing. The result for scheme 1 (SBP) shows that the NPS is the highest at zero frequency due to the lack of RA filter. Since the high frequency component is not effectively reduced by the IN filter, aliasing is introduced from the fz components higher than fz-NY. With the RA filter, as shown for filter schemes 2 and 3 in Fig. 8a, the NPS is zero at zero frequency and increases with frequency. Consequently, noise aliasing at high frequencies also becomes more significant. With the application of the ST filter in scheme 4, noise aliasing is practically eliminated.

To facilitate quantitative comparison between different filter schemes, the in-depth NPS at fz=0 is plotted in Fig. 8b for all four schemes. It shows that for scheme 1, the NPS drops rapidly as frequency increases because of the normalization by spoke density [Eq. 13]. For schemes 2–4, NPS near zero frequency is proportional to f as a result of the RA filter and the normalization by spoke density. The increase in NPS at high frequencies for schemes 1–3 is due to noise aliasing. Since the NPS replicates at multiples of fz-NY, the adjacent NPS intersects the x axis at multiples of 2fz-NY∕tan(θ∕2), i.e., 2.75 and 5.5 cycles∕mm. As a result, an abrupt increase in NPS occurs at these frequencies. The NPS for scheme 4 has the lowest magnitude without noise aliasing due to the additional ST filter.

NPS also depends on the angular range of DBT acquisition and the reconstructed voxel size. Shown in Fig. 9 is the NPS calculated for three different angular ranges: 20° (±10°), 40° (±20°), 180° (±90°), all reconstructed into anisotropic voxel size (0.085×0.085×1 mm3) with filter scheme 3. With the increase in angular range, the frequency space for NPS is better sampled, especially at low frequencies. However, since the wider angular range introduces more frequency components into the region above fz-NY, aliasing in NPS is more severe.

Figure 9.

The in-depth NPS for three angular ranges (20°, 40°, 180°) with filter scheme 3 and anisotropic voxel size (0.085×0.085×1 mm3). The NPS is plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm and fz-NY=±0.5 cycles∕mm).

To illustrate the effect of 3D sampling on aliasing, Fig. 10 shows the in-depth NPS with isotropic voxel size (0.085×0.085×0.085 mm3). The small voxel dimension in the z direction essentially eliminates aliasing for all angular ranges. The complete sampling of frequency space (180°) corresponds to CT, and the drop in NPS at low frequencies is due to the RA filter.15

Figure 10.

In-depth NPS for three different angular ranges (20°, 40°, 180°), reconstructed with scheme 3 and isotropic voxel size (0.085×0.085×0.085 mm3). The NPS is plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm and fz-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm).

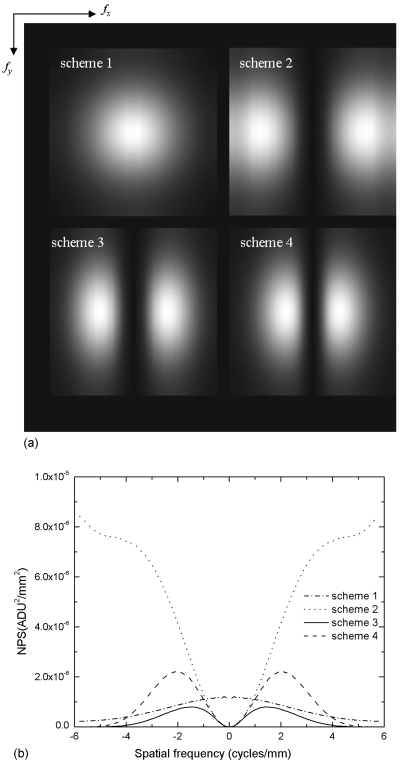

In-plane NPS

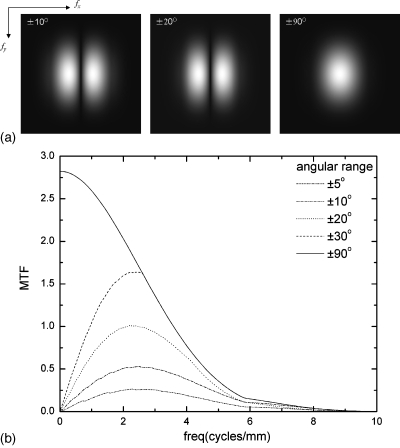

Figure 11a shows the in-plane NPS images for all four filter schemes obtained using Eq. 15, and the corresponding 1D plots at fy=0 are shown in Fig. 11b. The NPS of scheme 1 is isotropic, and the drop of NPS with f, as shown in Fig. 11b, is not as rapid as seen in the in-depth NPS. This is because the in-plane NPS is equal to the integration of the 3D NPS along the z direction, which cancels out the effect of spoke density and leaves the IN filter the only factor affecting the NPS. For schemes 2–4 with the RA filter, the in-plane NPS at low frequencies is essentially proportional to f2. This is because the f dependent 3D NPS is integrated in the z direction over a triangular shaped region of data sampled in DBT. It is interesting to point out that the noise aliasing pattern seen in the 3D NPS for filter schemes 1–3 is not observed in Figs. 11a, 11b. This is because the integration of aliased NPS along the z direction within fz-NY is equivalent to the integration of presampling NPS over all fz.

Figure 11.

(a) In-plane NPS for schemes 1–4 with angular range of ±20°. The NPS is plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=fy-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm). (b) In-plane NPS at fy=0 for filter schemes 1–4. Angular range=±20°.

MTF

3D MTF

The major factors affecting the presampling 3D MTF in our model are: (1) projection MTF of the detector; (2) focal spot blur; (3) reconstruction filters H(f); and (4) angular range of DBT acquisition. The results in this section will address the effects of factors 2–4 because they are unique to DBT.

Shown in Fig. 12 are the 3D presampling MTF plotted up to 2fNY in each direction for scheme 3. The 3D MTF is for a limited angular range of ±20°. Unlike the 3D NPS (Fig. 7), which is proportional to f at low frequencies, the 3D MTF at zero spatial frequency is unity for the sampled frequency space because as shown in Eq. 13, the f dependence of the RA filter cancels out the spoke density normalization factor.

Figure 12.

3D presampling MTF with scheme 3. The MTF is plotted up to 2fNY in each direction (2fx-NY=±11.8 cycles∕mm, 2fz-NY=±1 cycles∕mm). Half of the y axis is plotted. Lighter shade indicates higher value.

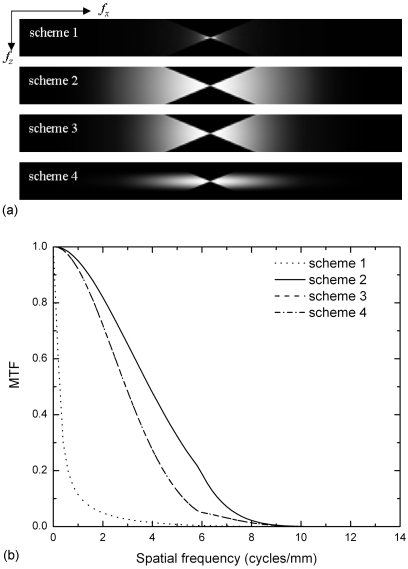

To facilitate the comparison of different filter schemes, the in-depth MTF (with fy=0) for all schemes are plotted in Fig. 13a. The MTF only has values within the angular range of DBT acquisition. For scheme 4, the presampling MTF does not extend beyond fz-NY=±0.5 cycles∕mm due to the application of the ST filter. The quantitative comparison of MTF can be better visualized using the 1D MTF plot shown in Fig. 12b for fy=fz=0.

Figure 13.

(a) In-depth MTF for the four filter schemes. Angular range=±20°. The MTF is plotted up to 2fNY in each direction (2fx-NY=±11.8 cycles∕mm, 2fz-NY=±1 cycles∕mm). (b) In-depth MTF at fz=0 for the four filter schemes. Angular range=±20°. The curves for schemes 3 and 4 overlap because the response of the ST filter is unity at fz=0.

The MTF for scheme 1 drops rapidly with frequency due to the normalization by spoke density. Its poor high frequency response predicts poor detection of calcification. The MTF for schemes 2 and 3 mainly differ in the high frequency response due to the application of the SA filter. Since the ST filter affects the response in the z direction only, the 1D MTF plot for schemes 3 and 4 essentially overlap.

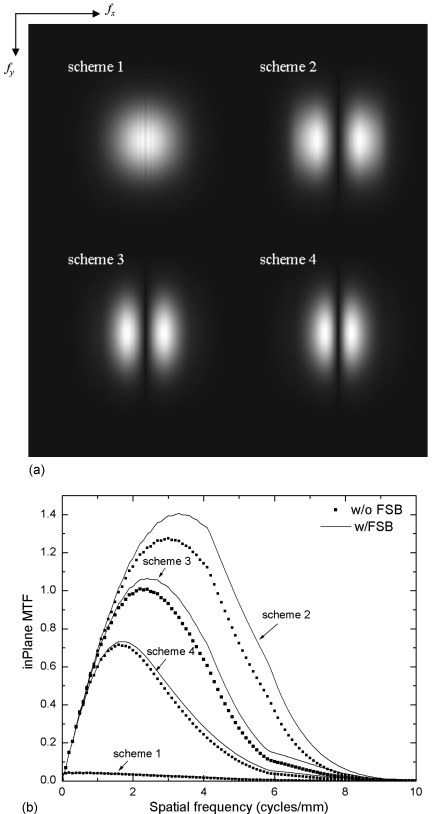

In-plane presampling MTF

Shown in Fig. 14a is the presampling in-plane MTF for all four filter schemes calculated by integrating the 3D MTF (Fig. 12) in the z direction using Eq. 17. The result corresponds to the in-plane presampling MTF measured with a point, slit, wire, or edge with infinitesimal dimension in the z direction. The in-plane MTF are shown for frequencies up to ±2fNY (11.8 cycles∕mm) in each direction. The shape of the MTF in the y direction is similar because the IN filter is identical for all cases. Due to the triangular shape of the sampled x-z frequency space [Fig. 13a] and the integration along the z direction, the in-plane presampling MTF in the x direction also has a triangular shape at low frequencies for schemes 2–4. This is shown more clearly in the 1D MTF plot in Fig. 14b with fy=0. The in-plane MTF was not normalized after integration of the 3D MTF in the z direction, hence, the MTF curves for schemes 2–4 exhibit the same slope, which reflects the angular range of DBT. The in-plane MTF for scheme 1 resembles the original MTF of the projection images because the effect of the z direction integration cancels out the spoke density normalization. The high frequency decrease in MTF is due to the combined high frequency response of different filters, with scheme 4 having the lowest values. To quantify the effect of additional FSB due to tube motion, the in-plane MTF with and without FSB are shown in comparison in Fig. 14b. The relative effect of FSB is less significant for schemes 3 and 4 compared to scheme 2 due to their poorer high frequency response of the filters. This is consistent to our previous study using a computer simulation platform.11 Since FSB does not introduce correlation in NPS, DQE would be degraded by the square of the MTF.

Figure 14.

(a) In-plane presampling MTF for different reconstruction filters. Angular range=±20°. The MTF is plotted up to 2fNY in each direction (2fx-NY=2fy-NY=±11.8 cycles∕mm). (b) In-plane presampling MTF at fy=0 cycles∕mm for the four filter schemes with and without FSB. Angular range=40°.

Figure 15a shows the dependence of the in-plane MTF on angular range (±10°, ±20°, ±90°) for filter scheme 3. A voxel dimension of dx=dy=0.085 mm and dz=1 mm was used for all cases. With complete data sampling (±90°), the low frequency drop in MTF disappears. To better visualize the effect of limited angular range, the in-plane MTF at fy=0 is plotted in Fig. 15b for five different angular ranges. The low frequency response increases with the increase in angular range while the high frequency response remains unchanged. The low frequency drop in MTF due to limited angular range is the main reason for the edge enhancement and decrease in object contrast seen in the images of mass in DBT.5, 11

Figure 15.

(a) In-plane presampling MTF at three angular ranges using reconstruction scheme 3 and anisotropic voxel size (0.085×0.085×1 mm3). The MTF is plotted up to 2fNY in each direction (2fx-NY=2fy-NY=±11.8 cycles∕mm). (b) In-plane presampling MTF at fy=0 at various angular range, using reconstruction scheme 3 and anisotropic voxel size (0.085×0.085×1 mm3).

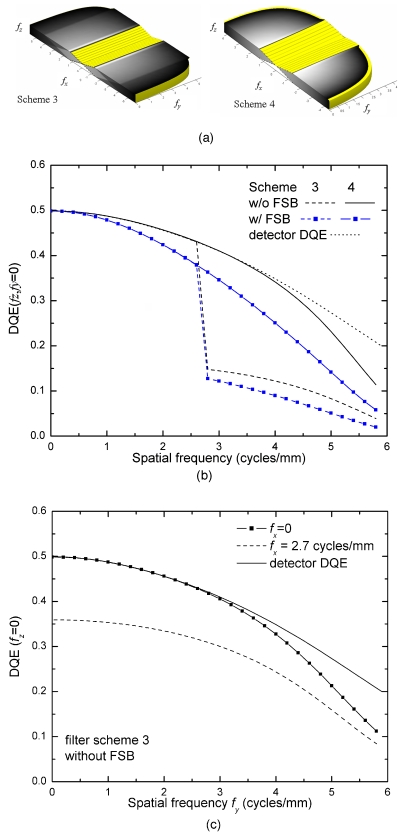

DQE

The 3D DQE was calculated using Eq. 18 and the output signal and noise power spectra, Ψb and Sv. The results for schemes 3 and 4 are shown in Fig. 16a. The DQE are given up to fNY in each direction. For scheme 3, the DQE exhibits a pattern that resembles the aliased NPS (Sv, Fig. 7). To facilitate comparison, the 1D DQE at fy=fz=0 are plotted in Fig. 16b. Without the ST filter (scheme 3), DQE drops by 50% at ∼2.7 cycles∕mm due to noise aliasing in the z direction because the SA filter is sufficient in minimizing noise aliasing in the x direction. With the ST filter (scheme 4), the DQE is very similar to the detector DQE except at high frequencies, where the interpolation filter is not sufficient to eliminate noise aliasing in the x direction. This demonstrates that the ST filter essentially eliminates 3D noise aliasing in the z direction and preserves 3D DQE. Also shown in Fig. 16b are the calculated DQE with FSB. At fNY=5.88 cycles∕mm, the additional drop of DQE due to FSB is 50%. This is because DQE is proportional to the square of the MTF due to FSB. For completeness, the DQE in the y direction (at fz=0) for filter scheme 3 (without FSB) are plotted in Fig. 16c. To illustrate the effect of noise aliasing, the DQE as a function fy is given for both fx=0 and 2.7 cycles∕mm, where the DQE drops abruptly due to noise aliasing in the z direction. Figure 16c shows that at fx=0, the 3D DQE is lower than the detector DQE at high fy. This is because in the y direction the interpolation filter is not sufficient to eliminate noise aliasing due to 3D sampling. At fx=2.7 cycles∕mm, an additional drop in DQE is seen at all frequencies due to noise aliasing in the z direction [as seen in Fig. 16b].

Figure 16.

(a) 3D DQE with filter schemes 3 and 4. The DQE is plotted up to fNY in each direction (fx-NY=fy-NY=±5.88 cycles∕mm and fz-NY=±0.5 cycles∕mm). Half of the y axis is plotted. Lighter shade indicates higher value. (b) The comparison of 3D DQE as a function of frequency in the x (tube travel) direction, with fy=fz=0. The solid lines with and without the square symbols represent the DQE for filter scheme 4 with and without the additional FSB, respectively. The dotted line shows the detector DQE (without FSB) for comparison. The dashed lines with and without the square symbols represent the DQE result for filter scheme 3 with and without the additional FSB. With filter scheme 3, the DQE drops abruptly at 2.7 cycles∕mm due to noise aliasing in the z (slice thickness) direction, as seen in Fig. 8b. (c) Comparison of 3D DQE in the y direction (perpendicular to tube travel direction) with fz=0. The solid curve shows the detector DQE, and the curve with solid squares shows the 3D DQE at fx=0. The dashed curve shows the 3D DQE at fx=2.7 cycles∕mm.

CONCLUSIONS

A 3D cascaded linear system model was developed for DBT to investigate the dependence of its imaging performance (in the form of 3D NPS, MTF, and DQE) on acquisition geometry and reconstruction parameters. The low frequency response for in-plane MTF is limited due to incomplete sampling in DBT. Both SA and ST filters help reduce high frequency noise and minimize 3D noise aliasing, resulting in improved 3-D DQE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support from the NIH (1 R01 EB002655), the U.S. Army Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-04-1-0554), and Siemens AG are gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Jennifer A. Segui and Dr. Jun Zhou for helpful discussion.

APPENDIX: SIGNAL AND NOISE PROPAGATION THROUGH LOGARITHMIC TRANSFORMATION

The logarithmic transformation can be regarded as a gain stage. Assuming the NPS of the projection image is Sp, and the average pixel intensity is kp=KX, where X is the entrance exposure and K is the x-ray sensitivity per pixel. The logarithmic transformation changes the mean signal to kl=log(kp). The gain associated with this process is x-ray exposure dependent and is given by the first derivative of kl with respect to kp,

| (A1) |

Since g depends on exposure, the logarithmic transformation can only be treated as a linear process within a small range of exposure, i.e., for NPS and low contrast signal. The signal and noise power spectra after the gain stage associated with logarithmic transformation are given by

| (A2) |

Since there is no additional noise associated with the gain stage, the DQE is not degraded.

References

- Wu T. et al. , “Tomographic mammography using a limited number of low-dose cone-beam projection images,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1543934 30, 365–380 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Moore R. H., Elizabeth A. B., Rafferty A., and Kopans D. B., in Categorical Courses in Diagnostic Radiology Physics: Advances in Breast Imaging: Physics, Technology, and Clinical Applications, edited by Karellas Andrew and Giger Maryellen L. (2004), pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ren B. et al. , “Design and performance of the prototype full field breast tomosynthesis system with selenium based flat panel detector,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.595833 5745, 550–561 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette M. et al. , “Digital breast tomosynthesis using an amorphous selenium flat panel detector,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.601622 5745, 529–540 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mertelmeier T., Orman J., Haerer W., and Dudam M. K., “Optimizing filtered backprojection reconstruction for a breast tomosynthesis prototype device,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.651380 6142, 61420F (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Lo J. Y., and J. T.DobbinsIII, “Impulse response analysis for several digital tomosynthesis mammography reconstruction algorithms,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.595684 5745, 541–549 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suryanarayanan S. et al. , “Evaluation of linear and nonlinear tomosynthetic reconstruction methods in digital mammography,” Acad. Radiol. 8, 219–224 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. et al. , “Digital tomosynthesis mammography using a parallel maximum-likelihood reconstruction method,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.534446 5368, 1–11 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. et al. , “A comparison of reconstruction algorithms for breast tomosynthesis,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1786692 31, 2636–2647 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A., “Full-field breast tomosynthesis,” Radiology management 27, 25–31 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Zhao B., and Zhao W., “A computer simulation platform for the optimization of a breast tomosynthesis system,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2558160 34, 1098–1109 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Lo J. Y., and J. T.DobbinsIII, “Noise power spectrum analysis for several digital breast tomosynthesis reconstruction algorithms,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.652282 6142, 614259 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. and Rowlands J. A., “Digital radiology using active matrix readout of amorphous selenium: Theoretical analysis of detective quantum efficiency,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.598097 24, 1819–1833 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewerdsen J. H. et al. , “Empirical and theoretical investigation of the noise performance of indirect detection, active matrix flat-panel imagers (AMFPIs) for diagnostic radiology,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.597919 24, 71–89 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijewski M. F. and Judy A., “The noise power spectrum of CT images,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/32/5/003 32, 565 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson K. M., “Detectability in computed tomographic images,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.594534 6, 441–451 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewerdsen J. H., Cunningham I. A., and Jaffray D. A., “A framework for noise-power spectrum analysis of multidimensional images,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1513158 29, 2655–2671 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewerdsen J. H. and Jaffray D. A., “Three-dimensional NEQ transfer characteristics of volume CT using direct- and indirect-detection flat-panel imagers,” Proceedings of SPIE, Medical Imaging 2003: Physics of Medical Imaging (SPIE, Bellingham, 2003) Vol. 5030, pp. 92–102.

- Zhao B. et al. , “Experimental validation of a three-dimensional linear system model for digital breast tomosynthesis,” Med. Phys. (submitted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. et al. , “Optimization of detector operation and imaging geometry for breast tomosynthesis,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.713718 6510, 65101M–65112M (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Deych R., and Dolazzab E., “Optimization of operational conditions for direct digital mammography detectors for digital tomosynthesis,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.597301 5745, 1272–1281 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kak A. C. and Slaney M., Principles of Computerized Tomographic Imaging (IEEE, New York, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. and Zhao W., “Characterization of a direct full-field flat-panel digital mammography detector,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.480388 5030, 157–167 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Ji W. G., and Rowlands J. A., “Effects of characteristic x rays on the noise power spectra and detective quantum efficiency of photoconductive x-ray detectors,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1405845 28, 2039–2049 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. et al. , “Imaging performance of amorphous selenium based flat-panel detectors for digital mammography: Characterization of a small area prototype detector,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1538233 30, 254–263 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Zhou J., and Zhao W., “Focal spot blur in tomosynthestic systems,” RSNA, 2005.

- Riederer S. J., Pelc N. J., and Chesler D. A., “The noise power spectrum in computed X-ray tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/23/3/008 23, 446–454 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner K. and Moores B. M., “Analysis of x-ray computed tomography images using the noise power spectrum and autocorrelation function,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/29/11/003 29, 1343–1352 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger M. L., RSNA Categorical Course in Diagnostic Radiology Physics: Advances in Breast Imaging—Physics, Technology, and Clinical Applications, 2004, pp. 205–217.

- Li B. et al. , “Optimization of slice sensitivity profile for radiographic tomosynthesis,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2742499 34, 2907–2916 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M. J., McGee R., and Blechinger J., “Spatial resolution of x-ray tomosynthesis in relation to computed tomography for coronal/sagittal images of the knee,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.713805 6510, 65100D–65109D (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- J. T.DobbinsIII, “Effects of undersampling on the proper interpretation of modulation transfer function, noise power spectra, and noise equivalent quanta of digital imaging systems,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.597600 22, 171–181 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segui J. A. and Zhao W., “Amorphous selenium flat panel detectors for digital mammography: Validation of a NPWE model observer with CDMAM observer performance experiments,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2349689 33, 3711–3722 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danty J. C. and Shaw R., Image Science, Principle, Analysis and Evaluation of Photographic-Type Imaging Processing (Academic, New York, 1974). [Google Scholar]