SUMMARY

Sympathetic activity and obesity have a reciprocal relationship. Firstly, hypothalamic obesity is associated with decreased sympathetic activity. Caffeine and ephedrine increase sympathetic activity and induce weight loss, of which 25% is due to increased metabolic rate and 75% is due to a reciprocally decreased food intake. Secondly, hormones and drugs that affect body weight have an inverse relationship between food intake and metabolic rate. Neuropeptide Y decreases sympathetic activity and increases food intake and body weight. Thirdly, a gastric pacemaker Transcend® and vagotomy increase the ratio of sympathetic to parasympathetic activation, decrease food intake, and block gut satiety hormones. Weight loss with the pacemaker or vagotomy is variable. Significant weight reduction is seen only in a small group of those treated. This suggests that activation of the sympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system may be most important for weight loss. Systemic sympathetic activation causes weight loss in obese patients, but side effects limited its use. We hypothesize that selective local electrical sympathetic stimulation of the upper gastrointestinal tract may induce weight loss and offer a safer, yet effective, obesity treatment. Celiac ganglia delivers sympathetic innervation to the upper gastrointestinal tract. Voltage regulated electrical simulation of the rat celiac ganglia increased metabolic rate in a dose-dependent manner. Stimulation of 6, 3, or 1.5 V increased metabolic rate 15.6%, 6.2%, and 5%, respectively in a single rat. These responses support our hypothesis that selective sympathetic stimulation of the upper GI tract may treat obesity while avoiding side effects of systemic sympathetic activation.

Introduction

Support for our hypothesis that sympathetic stimulation of the upper gastrointestinal tract may offer a safe and effective treatment for obesity comes from four general lines of evidence.

Hypothalamic obesity

Vagotomy can prevent hyperinsulinemia and obesity from hypothalamic damage in humans [38]. Rodents and humans with hypothalamic obesity show increased parasympathetic tone with augmented vagal activity, impaired responses of the sympathetic nervous system, decreased energy expenditure, and endocrine changes [9,25,31,38,41]. Human hypothalamic obesity was first reported by Frohlich [19], Bruch [11], and Babinski [4] at the beginning of the 20th century. Erdheim published one of the first collections of cases in 1904. The pathology showed damage to the medial hypothalamus, excluding the pituitary [17]. A collection of 134 patients, including eight original cases, were reported in 1975 [9]. An autopsy report by Reeves and Plum [33] showed that this syndrome was associated with bilateral injury to the ventromedial (or paraventricular) nuclei of the hypothalamus. Ventromedial nuclei control body weight. Destruction of these areas removes tonic inhibitory influences on traffic through the vagus nerve. The increased parasympathetic (vagal) tone elevates insulin release, increases food intake, and facilitates energy storage in adipose tissue [7]. Placing the islets under the kidney capsule removes them from vagal control, reverses the hyperinsulinemia resulting from hypothalamic damage, and prevents the development of obesity [24]. Leptin receptors are expressed in the hypothalamus. As in all obesities, leptin levels are high in hypothalamic obesity. The leptin responses, however, are reduced in hypothalamic injury due to damage to the leptin receptors. Hypothalamic obesity in humans, however, is uncommon.

In experimental animals, injury to the arcuate nucleus complex, ventromedial hypothalamic area, paraventricular nucleus or central nucleus of the amygdala increase food intake and obesity. The obesity occurs to some degree even when hyperphagia is prevented [26] in these animals with nervous system damage. Likewise, the injury is associated with an acute increase of vagal activity [5,23,27,39] accompanied by a decreased sympathetic activity [29,34,40,42].

Sympathetic activity in obesity

Low sympathetic activity is common in obesity of various etiologies including hypothalamic obesity [6]. An inverse relationship between sympathetic activity and food intake, and a direct relationship between sympathetic activity and metabolic rate are present [8]. Recently, an 18-year follow-up study demonstrated that lower sympathetic activity increased body fat over time [18].

Sympathetic activity is decreased in leptin deficiency and in other genetic mutant obesity. In leptin deficient mice, stimulation of the sympathetic innervation to brown adipose tissue results in less heat production than in lean littermates suggesting a reduced sympathetic activity [36]. The sympathetic activation seems to be mediated by cortocotrophin releasing factor (CRF) produced in the central nervous system (CNS) acting on the adrenal–pituitary circuit. Adrenalectomy reduces glucocorticoid feedback to the hypothalamus and increases the CRF that, in turn, stimulates the sympathetic nervous system. Thus, adrenalectomy stops the progression of obesity in ob/ob mice [10]. Diminished sympathetic activity is also seen in the yellow mouse that is obese as a consequence of overexpression of agouti-related protein. These data support that sympathetic activity is decreased as consequences of abnormalities in the CRF-pituitary–adrenal system that are present in the yellow mouse, ob/ob mouse, db/db mouse and the fa/fa rat, all of which have genetic defects in the leptin system or in agouti-related peptide [10,37]. Similarly, the reciprocal relationship of sympathetic activity to food intake takes place in normal humans as well. In an 18-year follow-up study, arterial plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine concentrations were measured in 99 healthy men during mental stress and baseline at rest. The data demonstrated that an increase in BMI and waist circumference are inversely related to the epinephrine and norepinephrine responses in the mental stress group compared to baseline (P < 0.05) [18]. The inverse relationship has also been shown when various drugs and hormones that affect body weight are administrated. Neuropeptide Y, β-endorphin, norepinephrine, and 2-deoxyglucose stimulate food intake and reduce sympathetic activity while enterostatin, glucagon, sibutramine, and amphetamine decrease food intake and increase sympathetic activity [8].

Sympatomimetic agents have shown some efficacy in the treatment of obesity. Clinical observations demonstrated that ephedrine stimulates β-adrenergic receptors to increase energy expenditure and decrease food intake [2]. Caffeine inhibits phosphodiesterase and adenosine receptors which otherwise blunt the effect of ephedrine [16]. Thus, a combination of ephedrine 20 mg and caffeine 200 mg three times a day was developed to treat obesity. Three hypothalamic obese patients lost an average of 10% of their body weight over 6 months when treated with the combination [21]. In a registration trial in Denmark to approve this combination for the treatment of obesity, the ephedrine and caffeine treated subjects lost 17.5% of initial body weight which was significantly greater than the placebo treated patients. A 13.6% of weight lost was seen in the placebo group, which is believed to be due to diet and nutritional consultation during the trial resulting in such a large loss in the placebo group [1]. In the case series of three hypothalamic obesity patients, without a stringent diet and nutritional counseling, all of the subjects with hypothalamic obesity lost less than 15% of their body weight with the combination. Unfortunately, acute side effects of nervousness, insomnia, rapid heartbeat, blood pressure elevation, and nausea were disadvantages of medication causing systemic sympathetic activation with ephedira, and these side effects resulted in the withdrawal of herbal caffeine from the unregulated dietary herbal supplement market by the US Food and Drug Administration [15,20].

Gastric pacemaker

Selective, rather than systemic, autonomic activation by electrical pacing for the treatment of obesity began in 1996 [14]. The Transcend® gastric pacemaker which stimulates the vagal innervation of the stomach is placed laparoscopically on the lesser curature of the stomach for the treatment of obesity [22]. The average weight loss in an unselected cohort of morbidly obese subjects was 10 kg [13]. Interestingly, a small group of subjects showed 30% weight loss, which is equivalent to the gastric bypass, an operation that gives durable weight loss over years of follow-up [13,22,32]. Increased vagal efferent activity elevates GI satiety hormones cholecystokinin (CCK), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and somatostatin, which is blocked by vagotomy [13]. All three of these hormones are associated with a decrease in food intake and they are paradoxically decreased by gastric stimulation [13]. The effect of the Transcend® pacemaker is believed to act through the vagal afferent signals to the brain and block the GI satiety hormones secretion mediated by efferent vagal activity. These and other stimulation data suggest that the local stimulation suppressed efferent and stimulated afferent vagal traffic to induce weight loss [12]. A similar variability of weight loss is seen with vagotomy as with the Transcend® gastric pacemaker [28]. This suggests to us that the ratio of sympathetic to parasympathetic activation is directly related to weight loss. One can consider that a predominance of vagal efferent overactivity causes obesity in the population that display 30% weight loss. By the same token, interruption of the efferent vagal pathway either by vagotomy or by vagal afferent stimulation causes significant weight loss in a small group of those treated. Taken together, both the sympathetic underactivity and the vagal overactivity may play an important role in perpetuating obesity. Thus, the ratio of sympathetic to parasympathetic activity would actually correlate better with obesity than either arm of the autonomic nervous system alone.

The hypothesis

We hypothesized that selectively stimulating the sympathetic nervous system that innervates the GI tract will have the potential to elevate metabolic rate while avoiding the systemic side effects.

Evaluation of the hypothesis

It is known that caffeine and ephedrine increase sympathetic tone and metabolic rate 19% over 3 h [2] and ephedrine increases metabolic rate 2% on an energy restricted diet measured in a metabolic chamber over 24 h [30]. Of the weight loss seen with caffeine and ephedrine, 25% is attributable to an increase in metabolic rate while 75% is due to a decrease in caloric intake [3]. However, the systemic stimulation of the cardiovascular and central nervous systems seen with caffeine and ephedrine resulted in their withdrawal from the non-prescription market [15].

An observation in a single rat

A cuff electrode made of plastic tubing and stainless steel wire was constructed [35]. The electrode was placed around the celiac ganglia of a Sprague Dawley rat under general anesthesia. The wires from the electrode exited from under the skin between the shoulder blades of the rat and ran through a long spring to protect them which was attached to a jacket placed around the animals forequarters. Post-operatively, the animal was allowed to recover for several weeks in its cage.

Impedance calculations were made on the electrode, and stimulus parameters were determined to protect the nerve from electrical injury. The upper end of the safe range was: 6 volts (V) at 30 cycles per second (cps) with a duration of 100 milliseconds (ms). Mean metabolic rate (MR) as oxygen consumption was measured, and data are expressed as mean ± SD.

The rat was placed in a metabolic chamber after surgery and given two days to acclimate followed by three stimulation periods. The rat was first stimulated for 2 days at 6 V/30 cps/100 ms. The stimulator was then turned off and the animal remained in the cage for an additional 2 days. A second stimulation period was performed to define the relationship between the voltage and the response of metabolic rate. The rat was allowed for another 2 days to acclimatize to the metabolic cage before the second stimulation. The stimulator was turned on for 2 days at 1.5 V/30 cps/100 ms. The stimulator was then turned off for 2 days and turned back on at 3 V/30 cps/100 ms for 2 days. After the last 2 days of stimulation, the stimulator was turned off and the rat was removed from the metabolic chamber and returned to its home cage.

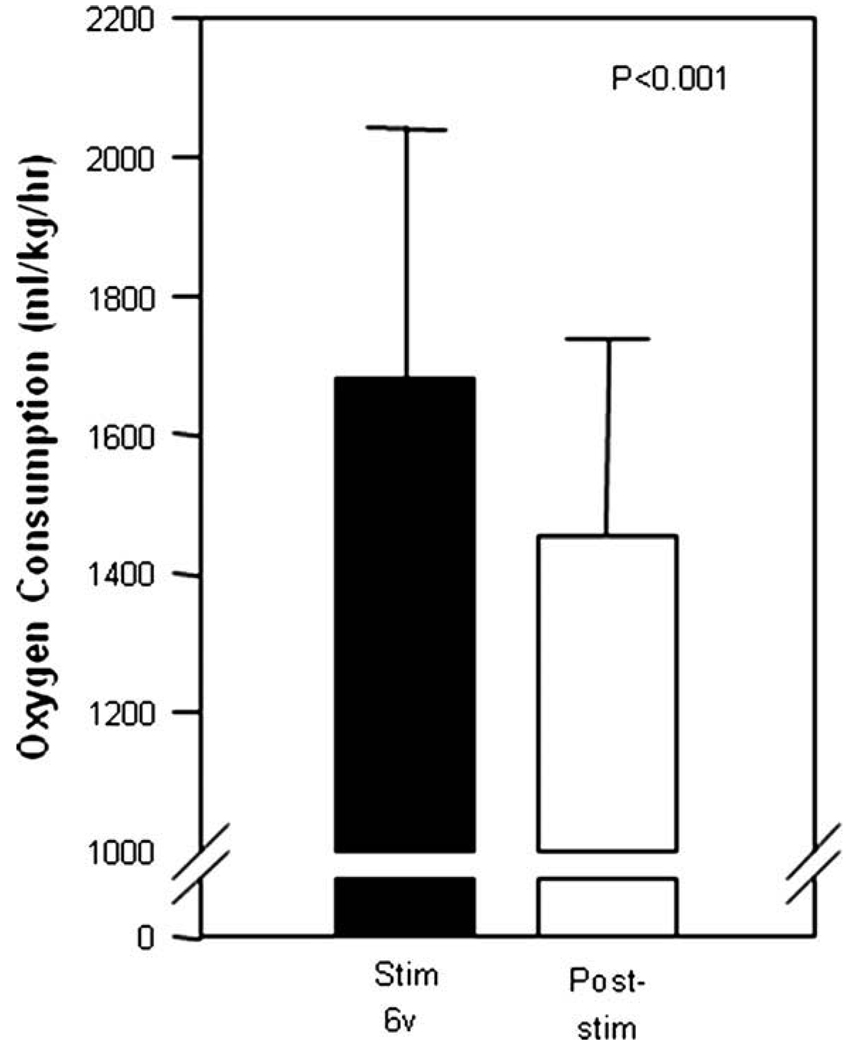

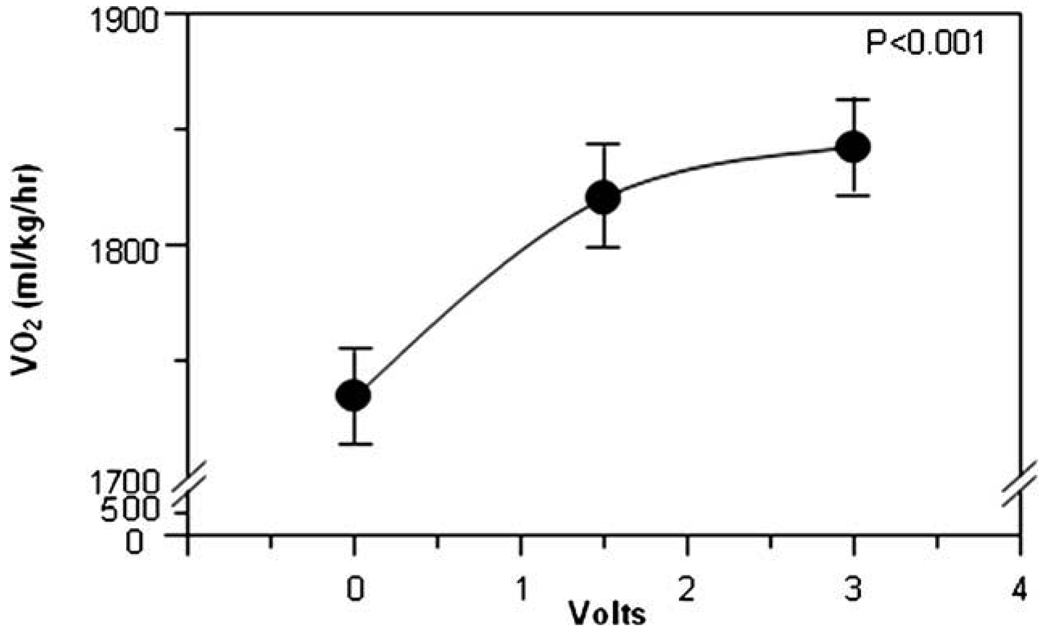

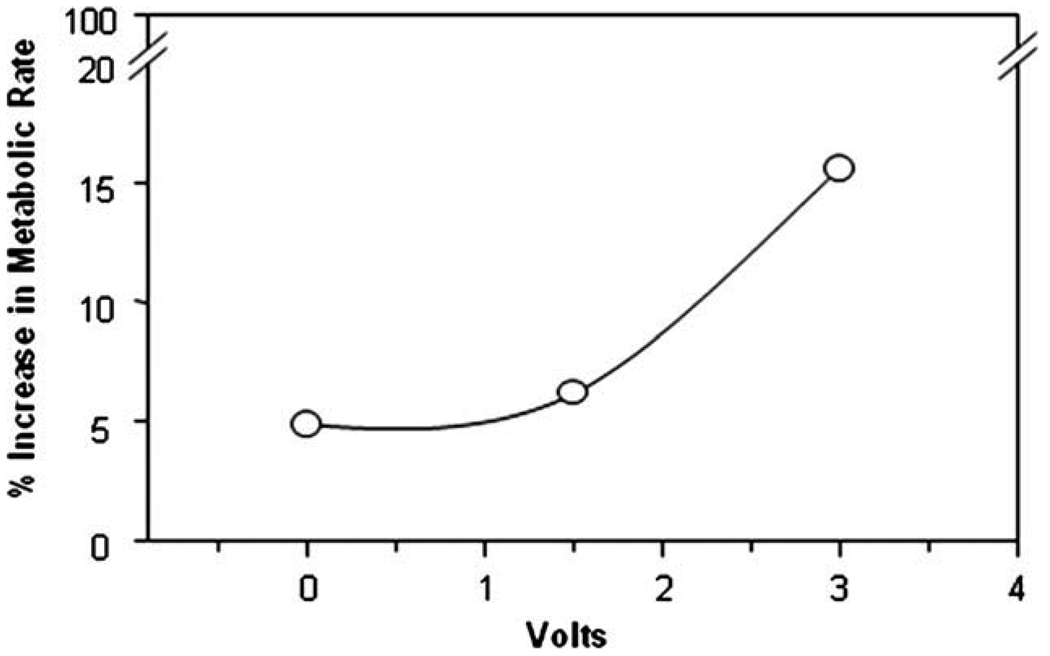

As expected, the first 2 days of the metabolic chamber stay had an elevated metabolic rate during the acclimatization in the metabolic chamber, due to the stress of the new environment. The data of the first 2 days of acclimatization are routinely eliminated from the analysis. The first 2 days of stimulation with 6 V gave metabolic rate of 1681 ± 359 ml/kg/h. The 2 days post-stimulation had a metabolic rate of 1454 ± 284 ml/kg/h. The period of stimulation had a 15.6% higher metabolic rate compared to the post-stimulation period (P < 0.001). Fig. 1 shows the metabolic rates over the days of the experiment. In the second period of stimulation, the control period had a mean MR of 1734 ± 387, the 1.5 V stimulation period had a mean MR of 1820 ± 419 (P < 0.001 compared to control) and the 3 V stimulation period had an increased mean MR of 1842 ± 287 (P < 0.001). The metabolic rate response in the second and third stimulation periods (Fig. 2) and the progressive percentage increase in metabolic rate (Fig. 3) demonstrated a voltage dependent increased metabolic rate.

Fig. 1.

The first selective electrical stimulation (6 V, filled bar) of the celiac ganglia significantly increased metabolic rate compared to post-stimulation (open bar) (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

The second stimulation of 1.5 V/30 cpa/100 ms followed by 3 V/30 cps/100 ms increased the metabolic in a voltage dependent manner.

Fig. 3.

The percentage increase in metabolic rate to electrical stimulation with 1.5 V/30 cps/100 ms followed by 3 V/30 cps/100 ms was greater than non-simulation.

At the end of the experiment, after the several months of placement, the animal was sacrificed and the electrode examined. The electrode placement around the celiac trunk in the correct position was verified. The celiac artery with the electrode in place was removed and placed in formalin. The electrode was then processed and examined histologically. There was a significant foreign body reaction in the tissues surrounding the artery. There was granulation tissue containing fibrin, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and neutrophils scattered in the tunica adventitia of the artery. The celiac ganglia were not injured, however. Sections of pancreas, lymph node, adrenal gland, nerves, and fat tissue adjacent to the celiac artery appeared normal.

Consequences of the hypothesis and discussion

We hypothesized that stimulation of the sympathetic innervation to the upper gastrointestinal tract could be a safe and effective treatment for obesity. We provided preliminary support of the hypothesis by stimulating the celiac ganglia that supplies the sympathetic innervation to the upper gastrointestinal tract in one rat. Our pilot data showed that a stimulation of 6 V/30 cps/100 ms increased 15.6% of metabolic rate without any evidence of discomfort. The metabolic rate increase was voltage dependent.

In hypothalamic obesity, treatment of the low sympathetic tone with caffeine and ephedrine, a sympathetic activating combination, resulted in weight loss. This weight loss was associated with symptoms of sympathetic stimulation of the cardiovascular and nervous systems over the first 8 weeks. Sympathetic activity is low in obesity and successful treatment, with either drugs or hormones, are associated with sympathetic activation and a reciprocal decrease in food intake. Sympathetic activation in humans under mental stress is inversely related to weight gain over the subsequent 18 years giving assurance that humans, as well as animals, are body weight responsive to endogenous sympathetic activation. The Transcend® gastric pacemaker blocks the increase in gastrointestinal hormones like cholecystokinin, glucagon-like peptide-1 and somatostatin that are associated with satiety. This suggests that the pacemaker blocks efferent vagal activity and may be similar to vagotomy which, like the pacemaker, gives variable weight loss. Although some subjects lose dramatic amounts of weight with these treatments, they are only small group of subjects which suggests that the sympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system plays a greater role in body weight control than the parasympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system.

We have shown in a single rat that stimulation with 6 V/30 cps/100 ms increased metabolic rate by 15.6%. A 15.6% increase in metabolic rate would be expected to give 0.28 kg of weight loss per week in a 70 kg man eating 2000 kcal/d. Assuming that 75% of weight loss is due to a reduction in food intake, as is the case with the combination of caffeine and ephedrine over 6 months, the total weight loss per week with stimulation to the celiac innervation of the GI tract would be estimated to be 1.13 kg per week. The gastric bypass gives an average weight loss of 30% of initial body weight sustained over many years [32]. Should the weight loss due to stimulation of celiac ganglia continue over 6 months, as is the case for caffeine and ephedrine, one may anticipate as much or more weight loss than is seen with gastric bypass surgery. A weight loss of this magnitude would be a twofold or greater increase compared to the 10–15% average weight loss seen with the Transcend® gastric pacemaker [22].

Clearly, we have only a medical hypothesis from our pilot study at this point. Together with the single rat data, however, the observations in hypothalamic obese patients, the demonstration of a reciprocal relationship between food intake and sympathetic tone, the evidence of the Transcend® pacemaker or vagotomy, are all supportive of our hypothesis. Further studies with larger numbers of animals to determine the effect of stimulation to the sympathetic innervation of the upper GI tract on food intake, blood pressure and body composition have been planned. The medical hypothesis that stimulation of the sympathetic innervation of the upper GI tract may be a safe and efficient future treatment for obesity will eventually require human testing and confirmation that systemic sympathetic stimulation of the cardiovascular and nervous systems does not occur.

Acknowledgement

Systems and methods for modulating sympathetic activity for the treatment of obesity were invented by DiLorenzo in 2003 (US Patent Publication No. US 2003/0018367 A1). This patent application was partial motivation for our hypothesis and the single rat study supports it.

References

- 1.Astrup A, Breum L, Toubro S, Hein P, Quaade F. The effect and safety of an ephedrine/caffeine compound compared to ephedrine, caffeine and placebo in obese subjects on an energy restricted diet. A double blind trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992:269–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astrup A, Buemann B, Christensen NJ, Toubro S, Thorbek G, Victor OJ, et al. The effect of ephedrine/caffeine mixture on energy expenditure and body composition in obese women. Metabolism. 1992:686–688. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90304-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astrup A, Toubro S, Christensen NJ, Quaade F. Pharmacology of thermogenic drugs. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992:246S–248S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.246s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babinski M. Tumeur du corps pituitaire sans acromegalie et avec arret de developpement des organes genitaux. Rev Neurol. 1900:531–533. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthoud HR, Niijima A, Sauter JF, Jeanrenaud B. Evidence for a role of the gastric, coeliac and hepatic branches in vagally stimulated insulin secretion in the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1983:97–110. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(83)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray GA. Obesity, a disorder of nutrient partitioning: the MONA LISA hypothesis. J Nutr. 1991:1146–1162. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.8.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bray GA. Genetic, hypothalamic and endocrine features of clinical and experimental obesity. Prog Brain Res. 1992:333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray GA. Reciprocal relation of food intake and sympathetic activity: experimental observations and clinical implications. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000:S8–S17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bray GA, Gallagher TF., Jr Manifestations of hypothalamic obesity in man: a comprehensive investigation of eight patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975:301–330. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray GA, York DA, Fisler JS. Experimental obesity: a homeostatic failure due to defective nutrient stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. Vitam Horm. 1989:1–125. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruch H. The Frohlich syndrome: report of the original case. Obes. 1939:329–331. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camilleri M, Toouli J, Herrera MF, Kulseng B, Kow L, Pantoja JP, et al. Intraabdominal vagal blocking (VBLOC therapy): clinical results with a new implantable medical device. Surgery. 2008:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cigaina V, Hirschberg AL. Gastric pacing for morbid obesity: plasma levels of gastrointestinal peptides and leptin. Obes Res. 2003:1456–1462. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cigaina V, Saggioro A, Rigo V, Pinato G, Ischai S. Long-term effects of gastric pacing to reduce feed intake in swine. Obes Surg. 1996:250–253. doi: 10.1381/096089296765556854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cockey CD. Ephedra banned. AWHONN.Lifelines. 2004:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6356.2004.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dulloo AG. Ephedrine, xanthines and prostaglandin-inhibitors: actions and interactions in the stimulation of thermogenesis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993:S35–S40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erdheim J. Uber hypophsenganggeschwulste und hirncholesteatome. Sitzungsb Akad Wissenchaften Wein. 1904:537–726. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flaa A, Sandvik L, Kjeldsen SE, Eide IK, Rostrup M. Does sympathoadrenal activity predict changes in body fat? An 18-y follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008:1596–1601. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frohlich A. Ein fall von tumor der hypophysis cerebri ohne akromegalie. Weiner Klin Rdsch. 1901:883–886. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenway FL. The safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical and herbal caffeine and ephedrine use as a weight loss agent. Obes Rev. 2001:199–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenway FL, Bray GA. Treatment of hypothalamic obesity with caffeine. Endocr Pract. 2008 doi: 10.4158/EP.14.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenway FL, Zheng J. Electrical stimulation as a treatment for obesity and diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007:251–259. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue S, Bray GA. The effects of subdiaphragmatic vagotomy in rats with ventromedial hypothalamic obesity. Endocrinology. 1977:108–114. doi: 10.1210/endo-100-1-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue S, Bray GA, Mullen YS. Transplantation of pancreatic beta-cells prevents development of hypothalamic obesity in rats. Am J Physiol. 1978:E266–E271. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.3.E266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeanrenaud B. Energy fuel and hormonal profile in experimental obesities. Experientia Suppl. 1983:57–76. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-6540-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King BM. The rise, fall, and resurrection of the ventromedial hypothalamus in the regulation of feeding behavior and body weight. Physiol Behav. 2006:221–244. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King BM, Frohman LA. The role of vagally-medicated hyperinsulinemia in hypothalamic obesity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1982:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(82)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kral JG. Vagotomy as a treatment for morbid obesity. Surg Clin North Am. 1979:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41991-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niijima A, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Jeanrenaud B. Role of ventromedial hypothalamus on sympathetic efferents of brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol. 1984:R650–R654. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.4.R650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasquali R, Casimirri F, Melchionda N, Grossi G, Bortoluzzi L, Morselli Labate AM, et al. Effects of chronic administration of ephedrine during very-low-calorie diets on energy expenditure, protein metabolism and hormone levels in obese subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992:85–92. doi: 10.1042/cs0820085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkins MN, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ, Stone TW. Activation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by the ventromedial hypothalamus. Nature. 1981:401–402. doi: 10.1038/289401a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995:339–350. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeves AG, Plum F. Hyperphagia, rage, and dementia accompanying a ventromedial hypothalamic neoplasm. Arch Neurol. 1969:616–624. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480120062005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakaguchi T, Bray GA, Eddlestone G. Sympathetic activity following paraventricular or ventromedial hypothalamic lesions in rats. Brain Res Bull. 1988:461–465. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sauter JF, Berthoud HR, Jeanrenaud B. A simple electrode for intact nerve stimulation and/or recording in semi-chronic rats. Pflugers Arch. 1983:68–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00585171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seydoux J, ssimacopoulos-Jeannet F, Jeanrenaud B, Girardier L. Alterations of brown adipose tissue in genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. I. Demonstration of loss of metabolic response to nerve stimulation and catecholamines and its partial recovery after fasting or cold adaptation. Endocrinology. 1982:432–438. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-2-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu H, Shargill NS, Bray GA. Adrenalectomy and response to corticosterone and MSH in the genetically obese yellow mouse. Am J Physiol. 1989:R494–R500. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.2.R494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith DK, Sarfeh J, Howard L. Truncal vagotomy in hypothalamic obesity. Lancet. 1983:1330–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tokunaga K, Fukushima M, Kemnitz JW, Bray GA. Effect of vagotomy on serum insulin in rats with paraventricular or ventromedial hypothalamic lesions. Endocrinology. 1986:1708–1711. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-4-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vander Tuig JG, Knehans AW, Romsos DR. Reduced sympathetic nervous system activity in rats with ventromedial hypothalamic lesions. Life Sci. 1982:913–920. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90619-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.York DA, Bray GA. Dependence of hypothalamic obesity on insulin, the pituitary and the adrenal gland. Endocrinology. 1972:885–894. doi: 10.1210/endo-90-4-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida T, Bray GA. Catecholamine turnover in rats with ventromedial hypothalamic lesions. Am J Physiol. 1984:R558–R565. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.4.R558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]