Abstract

The escape swim response of the marine mollusc Tritonia diomedea is a well-established model system for studies of the neural basis of behavior. While the swim neural network is reasonably well understood, little is known about the transmitters used by its constituent neurons. In the present study, we provide immunocytochemical and electrophysiological evidence that the S-cells, the afferent neurons that detect aversive skin stimuli and in turn trigger Tritonia’s escape swim response, use glutamate as their transmitter. First, immunolabeling revealed that S-cell somata contain elevated levels of glutamate compared to most other neurons in the Tritonia brain, consistent with findings from glutamatergic neurons in many species. Second, pressure-applied puffs of glutamate produced the same excitatory response in the target neurons of the S-cells as the naturally released S-cell transmitter itself. Third, the glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX completely blocked S-cell synaptic connections. These findings support glutamate as a transmitter used by the S-cells, and will facilitate studies using this model system to explore a variety of issues related to the neural basis of behavior.

Keywords: Tritonia diomedea, glutamate, afferent neurons

Introduction

Upon skin contact with its seastar predators, the marine mollusc Tritonia diomedea launches a stereotyped escape swim response consisting of a series of alternating ventral and dorsal whole-body flexions that propel it away to safety. The neural circuit mediating this escape behavior is reasonably well understood, and consists of known afferent neurons, command interneurons, central pattern generator interneurons, and efferent flexion neurons (Fig. 1A; (Willows et al., 1973, Getting, 1976, 1983, Frost and Katz, 1996, Frost, 2001)). Because the neural program underlying the escape swim can be elicited and studied in experimentally tractable isolated brain preparations (Fig. 1B, 2A), this model system has been used to study a number of issues concerning the neural basis of behavior. These include cellular mechanisms related to learning and memory, rhythmic pattern generation, multifunctional networks, and prepulse inhibition (Getting, 1983, Katz et al., 1994, Katz and Frost, 1995a, b, Frost et al., 1996, Frost et al., 1998, Mongeluzi et al., 1998, Mongeluzi and Frost, 2000, Popescu and Frost, 2002, Frost et al., 2003, Frost et al., 2006). Further mechanistic studies of these topics would benefit from increased knowledge of the transmitters used by the swim circuit neurons. While the Dorsal Swim Interneurons (DSIs) of the swim central pattern generator have been shown to be serotonergic (McClellan et al., 1994, Katz et al., 1994, Katz and Frost, 1995a, Fickbohm et al., 2001), the neurotransmitters used by the other swim circuit neurons have yet to be identified, with the possible exception of a role for the peptide TPep (Beck et al., 2000) and a preliminary report of immunoreactivity for the peptide transmitters SCPB and FMRFamide in Cerebral Neuron 2 (C2) (Longley, 1987). Here we focused on the transmitter used by the afferent neurons for the escape swim circuit, the S-cells.

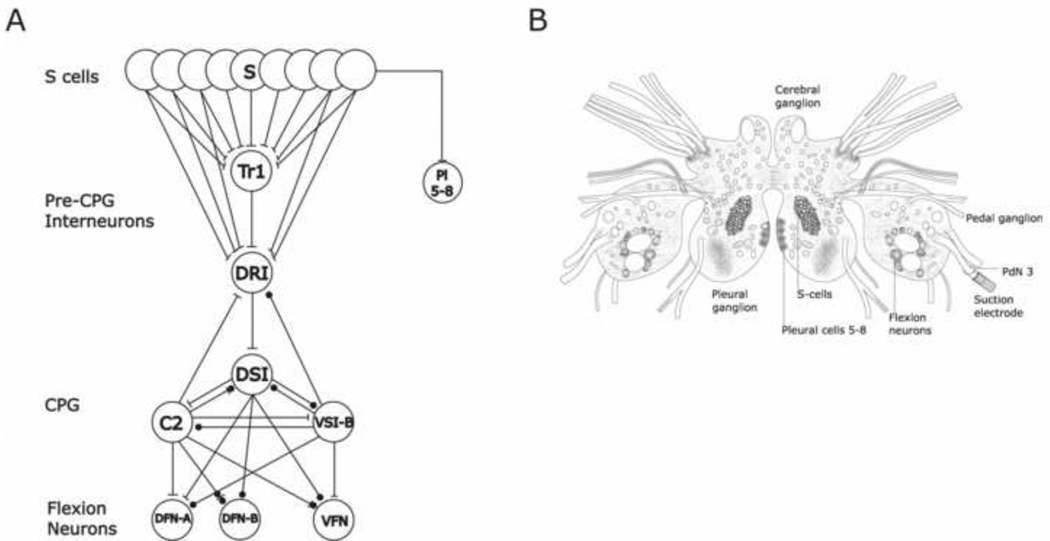

Figure 1.

The Tritonia isolated brain preparation and the escape swim network. (A) The escape swim circuit, which includes the afferent neurons (S-cells), the pre- central pattern generator excitatory interneurons (Tr1 and DRI), central pattern generator interneurons (C2, DSI and VSI-B), and the flexion neurons (VFN and DFN). Pleural cells 5–8, located outside the swim network, are also indicated. Excitatory synapses are indicated as bars, inhibitory as circles. (B) Schematic illustration of the isolated brain preparation, depicting the positions of the S-cells, the Pleural cells 5–8 and the suction electrode placement onto Pedal Nerve 3 for the peripheral nerve stimulation used to trigger the swim motor program.

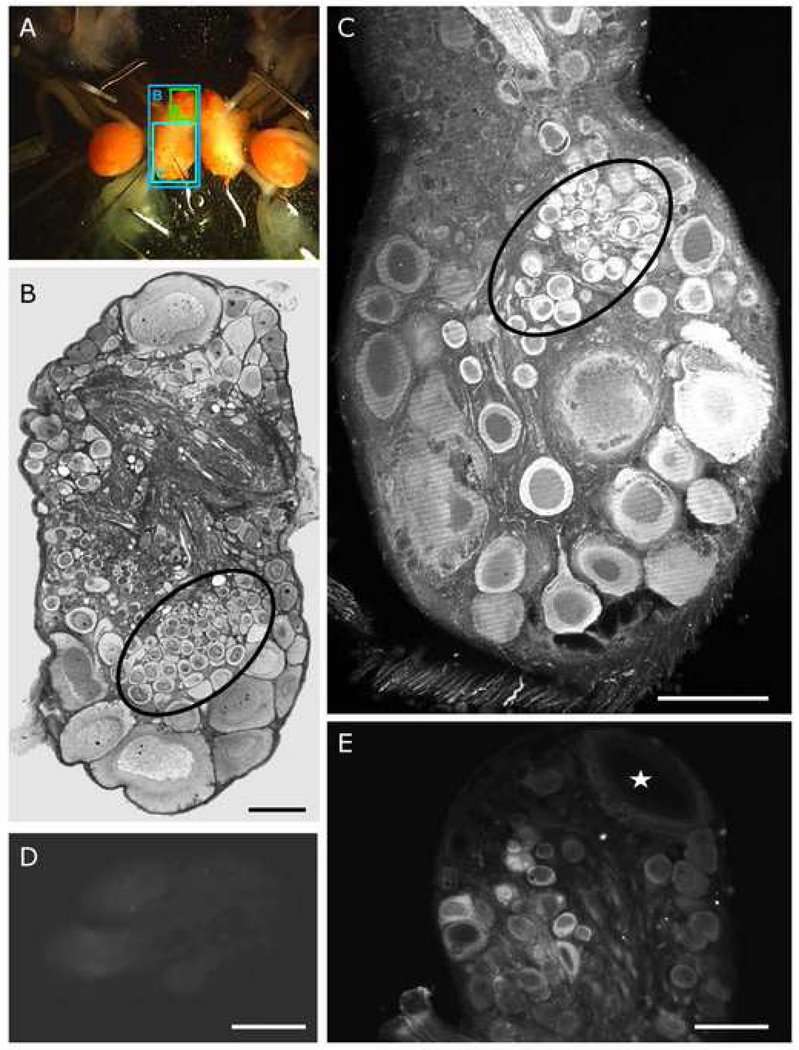

Figure 2.

Glutamate immunoreactivity in S-cells. (A) Tritonia diomedea brain ganglia in the living state, pinned out before fixation. Lettered boxes indicate the specific areas depicted in the corresponding figure panels. (B) Light micrograph image of a non-immunostained 2 µm epoxy section of the left dorsal cerebro-pleural ganglion through the S-cell cluster (circled). (C) Confocal image of a 50 µm horizontal section through the left dorsal pleural ganglion. The S-cells (circled) showed strong glutamate immunolabeling in their cytoplasm. (D) Sections incubated with a solution in which the primary antibody was pre-absorbed to a glutamate-glutaraldehyde conjugate failed to show immunoreactivity (section though the S-cell cluster). (E) C1 (star), a known serotonergic cell, showed no specific immunolabeling and served as a control for antibody specificity. All calibration bars 100µm.

The S-cells form a bilateral cluster of several dozen neurons each, located on and below the surface of the dorsal side of the pleural ganglia (Fig. 1B, 2B; (Getting, 1976)). Each S-cell sends one or more peripheral axons into nerves that innervate the skin. Mechanical and some chemical skin stimuli elicit action potentials in the afferent terminals of these pseudounipolar neurons, which then propagate orthodromically to the central S-cell somata and synapses. In isolated brain preparations, the swim motor program can readily be elicited by stimulating any of several peripheral nerves containing S-cell axons, such as Pedal Nerve 3, which innervates the animal’s mid-body and tail (Fig. 1B; (Dorsett et al., 1973, Cain et al., 2006)). The importance of the S-cells in swim initiation was established by removing these neurons, which eliminated the ability of skin stimuli to trigger the swim motor program (Getting, 1976). They are of additional interest because they exhibit experience-dependent plasticity. For example, they undergo rapid and pronounced homosynaptic depression when repeatedly stimulated (Getting, 1976, Hoppe, 1998). In addition, through the action of identified inhibitory interneurons they undergo presynaptic inhibition of transmitter release, a mechanism shown to play a role in mediating prepulse inhibition in Tritonia (Frost et al., 2003). The S-cells initiate the swim motor program through their excitatory monosynaptic connections with swim interneurons Trigger Neuron 1 (Tr1) and Dorsal Ramp Interneuron (DRI). Each one also makes monosynaptic excitatory connections with a small number of other S-cells, and with Pleural cells 5–8 (Fig. 1A; (Getting, 1976, Hoppe, 1998, Frost et al., 2003)), a group of large, easily identified pleural ganglion neurons (Willows et al., 1973) located outside the swim circuit.

Various molecules have been identified as afferent neuron transmitters in vertebrates and invertebrates. For example, acetylcholine (Lutz and Tyrer, 1988, Burrows, 1996) and histamine (Buchner et al., 1993, Melzig et al., 1996) perform this role in insects. Glutamate has been implicated as an afferent neuron transmitter in many species, including mammals (Raab and Neuhuber, 2007), zebrafish (Edwards and Michel, 2002), leech (Groome and Vaughan, 1996) and Caenorhabditis elegans (Lee et al., 1999, Rankin and Wicks, 2000, Mellem et al., 2002). Several studies have shown glutamate to play this role in molluscs, including the sea slug Aplysia (Dale and Kandel, 1993, Levenson et al., 2000, Chin et al., 2002, Antzoulatos and Byrne, 2004) and the terrestrial snail Helix (Bravarenko et al., 2003).

In Tritonia, a preliminary study reported that glutamate and glutamate agonists activated the swim pattern generator, and that glutamate antagonists blocked its activation by peripheral nerve stimulation (Brown and Willows, 1993), raising the possibility that the S-cells might be glutamatergic. Here we employed several standard criteria for determining neuronal transmitter type. Because the S-cells play a central role in several features of network function common to vertebrates and invertebrates, such as behavioral initiation and prepulse inhibition, establishing the identity of their transmitter will assist mechanistic studies of these fundamental phenomena in this invertebrate model preparation. Some of these results have been previously reported in abstract form (Megalou, 2005).

Materials and methods

Animals

Tritonia diomedea were obtained from Living Elements (North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), and maintained at 11°C in recirculating artificial seawater systems at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

Immunocytochemistry

Tritonia brains (Fig. 1B, 2A), consisting of the fused cerebral-pleural ganglia and the pedal ganglia, were removed and pinned out in Sylgard-lined petri dishes, where they were fixed for 3 days at room temperature in freshly-prepared fixative containing 4% formaldehyde (itself freshly made from paraformaldehyde) in 0.2M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4. Following fixation, the ganglia were rinsed for 2 h in several washes of phosphate-buffered saline (0.015M sodium phosphate, 0.135M NaCl, pH 7.4). Next they were embedded in low-gelling-temperature agarose gel, and 50 µm sections were cut with a vibrating microtome. To minimize nonspecific binding, tissue sections were incubated, before exposure to the antibody, for 2 h in a buffer solution of 3% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X100 (PBS-TX). The primary antibody (rabbit antiserum to glutamate, #AB5018, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) was raised against a covalent conjugate of glutamate and glutaraldehyde. Three brains were exposed to primary antiserum diluted 1:100 in buffer solution. Another brain had alternate sections exposed either to this diluted primary antiserum or to a control antiserum, which was prepared by adding 12 µg of a glutamate-glutaraldehyde conjugate per ml of diluted primary antiserum, as described by Di Cosmo et al (Di Cosmo et al., 1999). Brain sections were exposed to the antisera for 18 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. After washing in PBS-TX for 2 h, sections were incubated for another 18 h in secondary antibody (goat antiserum to rabbit IgG, conjugated to Cy3; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:1000 in PBS-TX containing 1% normal goat serum. Sections were then washed again in PBS-TX for 2 h. Finally, sections were cleared by immersion in glycerol:PBS (4:1) for 1 h before being mounted on glass slides and coverslipped.

Glutamate immunofluorescence was visualized with either an inverted microscope equipped with an Olympus FluoView300 confocal head (argon laser excitation 450–490 nm and LP 590 nm emission filter), or with a Nikon Optiphot epifluorescence microscope equipped with a standard RITC ("G") filter cube. In one preparation, two S-cells were injected with Lucifer Yellow (5% Lucifer Yellow in 1 M lithium chloride) via iontophoresis (1 nA hyperpolarizing current pulses, 500 ms duration, 1 Hz) before fixation in order to independently confirm the identity of the immunolabeled neurons as S-cells.

Electrophysiology

Isolated brain preparation: The brain, consisting of the paired cerebro-pleural and pedal ganglia and associated nerve roots, was dissected from the animal and pinned to the bottom of a Sylgard-lined chamber. The chamber was continuously perfused with 4°C artificial seawater (Instant Ocean, Aquarium Systems, Mentor, OH) while the connective tissue and ganglionic sheath were surgically removed. The saline was then warmed up to the animals’ physiological temperature of 11°C for the duration of the experiment. Data acquisition and analysis: Intracellular recordings were made with single-barrel electrodes (16–20 MΩ) filled with 4 M potassium acetate or 3 M potassium chloride connected to either Axoclamp 2B (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) or Dagan IX2-700 (Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) amplifiers. Data were digitized at 1–2 kHz and analyzed using Axon Instruments (Digidata 1322A, Clampex, Union City, CA) and Biopac Systems (MP100, AcqKnowledge, Goleta, CA) hardware and software.

Drugs

Glutamate (Sigma, MO), dissolved to a concentration of 100 mM in artificial seawater with Fast Green to allow visualization of the puff, was focally applied by pressure ejection via a micropipette (Picospritzer, Parker Hannifin Corporation, Fairfield, NJ). The pH of the puffed glutamate and control solutions was not measured or controlled. The specific non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione; Sigma, MO), was dissolved in 100% DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) to prepare a 10 mM stock solution. This was then diluted in artificial seawater to make specific CNQX concentrations, with the DMSO concentration never exceeding 1.5%. Identical DMSO-containing drug-free solutions were used to control for effects of the DMSO itself. Studies in various molluscs (Storozhuk and Castellucci, 1999, Kimura et al., 2001, Hochner et al., 2003, Lima et al., 2003, Piscopo et al., 2007) as well as hippocampus (Poncer et al., 1995, Du et al., 2000) have used CNQX in the concentrations employed in the present study (100 – 300 µM) to block glutamate responses.

Statistics

Electrophysiological data were analyzed with either paired t-tests, or a repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests.

Results

To evaluate the hypothesis that the S-cells are glutamatergic, we tested whether they had elevated glutamate immunoreactivity, whether the postsynaptic neurons they excite were depolarized by glutamate, and whether a glutamate antagonist blocked S-cell synapses.

S-cells show elevated glutamate immunoreactivity

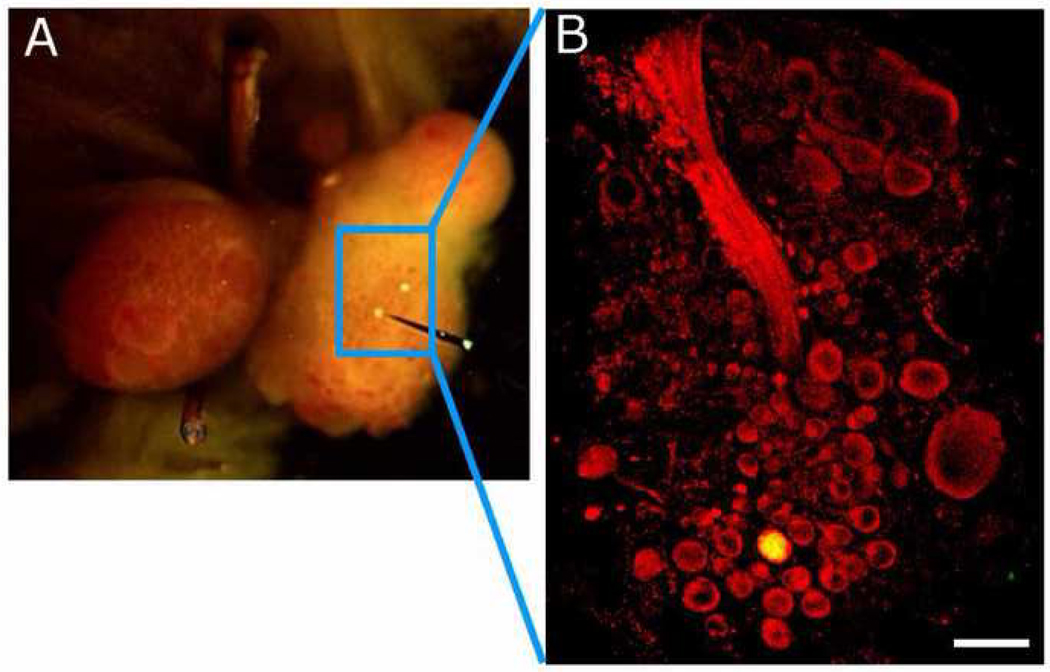

Prior immunocytochemical studies have reported that the somata of glutamatergic neurons display visibly elevated levels of glutamate labeling compared to those of non-glutamatergic neurons in Aplysia (Levenson et al., 2000), Lymnaea (Hatakeyama et al., 2007), and vertebrates (Kai-Kai and Howe, 1991). To evaluate this for the Tritonia S-cells, cerebral-pleural ganglia from 4 animals were formaldehyde-fixed and then treated with a polyclonal antibody raised against a glutaraldehyde-glutamate conjugate, followed by a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. While many neurons displayed noticeable glutamate immunoreactivity, the S-cell cluster neurons were consistently labeled more strongly than the majority of neurons in all four preparations examined (Figs. 2C, 3B). The S-cell cluster is easily recognized in the tissue slices used for immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2B). We further confirmed this by injecting two electrophysiologically identified S-cells in one preparation with Lucifer Yellow, prior to fixation (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B shows one of these S-cells located among the antibody-labeled pleural S-cell cluster.

Figure 3.

Lucifer Yellow and glutamate co-labeling of S-cells. (A) Two S-cells (yellow cells) were injected with Lucifer Yellow prior to fixation. They are shown here in the live isolated brain preparation. (B) One of the dye-filled S-cells appears in this confocal image of a 50 µm section taken through the glutamate immunolabeled dorsal pleural cluster (circle), independently confirming it as the S-cell cluster. Calibration bar 100 µm.

In one preparation, alternating sections were treated with either the primary antiserum directly, or with the primary antiserum after it had been exposed to a glutamate-glutaraldehyde conjugate. This latter procedure served as a control for nonspecific binding by the primary antiserum. These alternate control sections were found to be unlabeled (Fig. 2D), supporting the conclusion that the primary antibody did indeed label neurons containing elevated levels of glutamate. An additional indication of antibody specificity was that cell C1, a known Tritonia serotonergic neuron (Weinreich et al., 1973, Sudlow et al., 1998, Fickbohm and Katz, 2000, Fickbohm et al., 2001, Fickbohm et al., 2005), consistently showed no elevated glutamate labeling (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these immunocytochemical data are consistent with the hypothesis that the S-cells are glutamatergic.

S-cell postsynaptic neurons are excited by glutamate puffed onto their somata

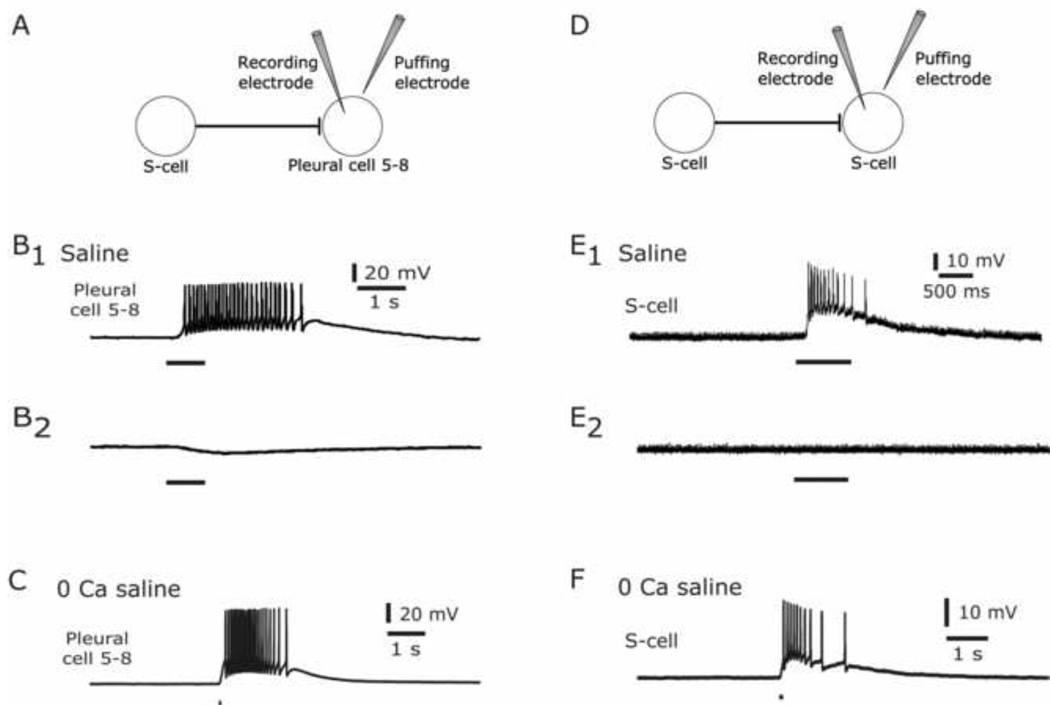

Postsynaptic targets of glutamatergic neurons often express functional glutamate receptors in the soma membrane, not just at postsynaptic densities (Dale and Kandel, 1993 Dale, 1993 #285, Bravarenko et al., 2003). We therefore tested whether pressure-applied l-glutamate puffs directed onto the somata of known postsynaptic excitatory targets of the S-cells would excite those neurons. The first such neurons tested were Pleural Cells 5–8 (Pl 5–8) (Frost et al., 2003), a group of large neurons originally described by Willows, et al (1973) that are located outside the swim network. A stimulator-controlled Picospritzer was used to apply small puffs of 100 mM l-glutamate colored with Fast Green from a glass micropipette onto the somata of Pl 5–8 neurons, while recording the membrane potential of the same neuron with a second, intracellular pipette (Fig. 4A). Such glutamate puffs reliably elicited action potentials in Pl 5–8 neurons in normal saline (Fig. 4B1; n = 5 cells, 3 preparations), while puffs of the saline vehicle alone had no excitatory effect (Fig. 4B2; n = 2 cells, 2 preparations). We also applied glutamate puffs to the S-cells themselves (Fig. 4D), because prior paired intracellular recording studies found that the S-cells make a low number of excitatory connections onto one another (Hoppe, M.S. Thesis, 1998). Glutamate puffs onto S-cell somata consistently elicited action potentials in the target S-cell (Fig. 4E1; n = 7 cells, 4 preparations), while vehicle puffs had no excitatory effect (Fig. 4E2; n = 3 cells, 2 preparations).

Figure 4.

S-cell postsynaptic neurons are excited by pressure-applied glutamate to the soma. (A) Schematic illustration of the monosynaptic connection between S-cells and Pleural cells 5–8 and of the recording (left) and puffing (right) microelectrode placement. (B) Response of Pleural Cells 5–8 in normal saline. B1. A puff of 100mM glutamate elicited action potentials. B2. A puff of the saline vehicle produced no depolarizing response. (C) Pleural Cells 5–8 depolarized and fired in response to a 100 mM glutamate puff in 0 mM calcium, 10 mM cobalt saline. (D) Schematic illustration of the monosynaptic connection between S-cells and of the microelectrode placement. (E) Response of S-Cells in normal saline. E1. A puff of 100 mM glutamate elicited action potentials. E2. A puff of the saline vehicle produced no depolarizing response. (F) S-cells depolarized and fired in response to a 100 mM glutamate puff in 0 mM calcium, 10 mM cobalt saline. In all panels, the horizontal bar beneath the response indicates the duration of the puff.

In a more discriminating test that these excitatory responses resulted from receptors located on the target neurons, we conducted another set of experiments in which the calcium in the artificial saline was replaced with cobalt, a calcium channel antagonist (composition (in mM): 420 NaCl, 10 KCl, 10 CoCl2, 50 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.6, and 11 D-glucose). This solution blocks chemical synaptic transmission, minimizing the likelihood that the excitatory responses we recorded were due to synaptic responses to the firing of neighboring neurons unintentionally excited by the glutamate puffs. Glutamate puffs again produced depolarization and firing in both the Pleural 5–8 neurons (Fig. 4C; n = 3 cells, 3 preparations) and the S-cells (Fig. 4F; n = 11 cells, 4 preparations). As before, puffing the saline vehicle had no excitatory effect in either neuron type (n = 2 cells of each type). These results indicate that the S-cell postsynaptic neurons contain glutamate receptors in their plasma membrane that mediate depolarizing responses, matching the responses of the same neurons to the natural S-cell transmitter.

The glutamate antagonist CNQX blocks the swim motor program elicited by peripheral nerve stimulation

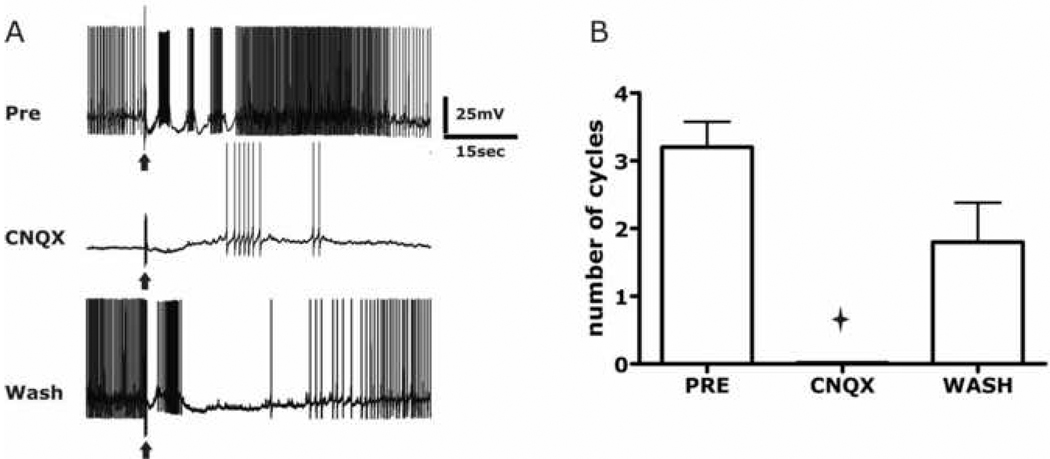

Each centrally-located S-cell sends one or more axons out through peripheral nerves to the skin. Electrical stimulation of these peripheral nerves elicits action potentials in S-cell axons, which then propagate orthodromically to elicit the swim motor program. A preliminary study reported that bath application of the non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX blocked the ability of such nerve stimulation to trigger the swim motor program (Brown and Willows, 1993), but the locus of the blocking effect of CNQX was not determined (e.g., whether it was at S-cell synapses or at glutamatergic synapses made by interneurons within the swim circuit). Here we began by attempting to replicate this effect of CNQX. The ability of a Pedal Nerve 3 stimulus to trigger the motor program was tested before, during, and after the application of CNQX via bath perfusion at 1 ml/min to our 1 ml recording chamber (Fig. 5). The motor program was monitored via intracellular recordings from pedal ganglion swim flexion neurons located near pedal neurons 5 and 6 (Willows et al., 1973). Before CNQX, a 1 s, 10 Hz stimulus to Pedal Nerve 3 elicited swim motor programs with an average duration of 3.2 ± 0.4 cycles (n = 5 preparations). When tested after 30 min in 200–300 µM CNQX, nerve stimulation no longer elicited the motor program (0.0 ± 0.0 cycles, t = 8.55, P < 0.002). The nerve stimulus was delivered every 10 min during the wash period to test for motor program recovery, which began to develop after approximately 20 min. Taken together, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that the swim network contains glutamatergic synapses, which may include the synapses made by the S-cells.

Figure 5.

The glutamate antagonist CNQX blocked the ability of sensory input to elicit the swim motor program. (A) Upper trace: Pedal Nerve 3 stimulation elicited a 3-cycle swim motor program, recorded in a pedal ganglion flexion neuron in normal saline. Middle trace: The motor program response was blocked during bath application of 300 µM CNQX. Lower trace: The motor program was starting to reoccur after 45 min in wash. (B) Group data for the experiment (n = 5 preparations).

CNQX blocks monosynaptic EPSPs elicited by S-cell intracellular stimulation

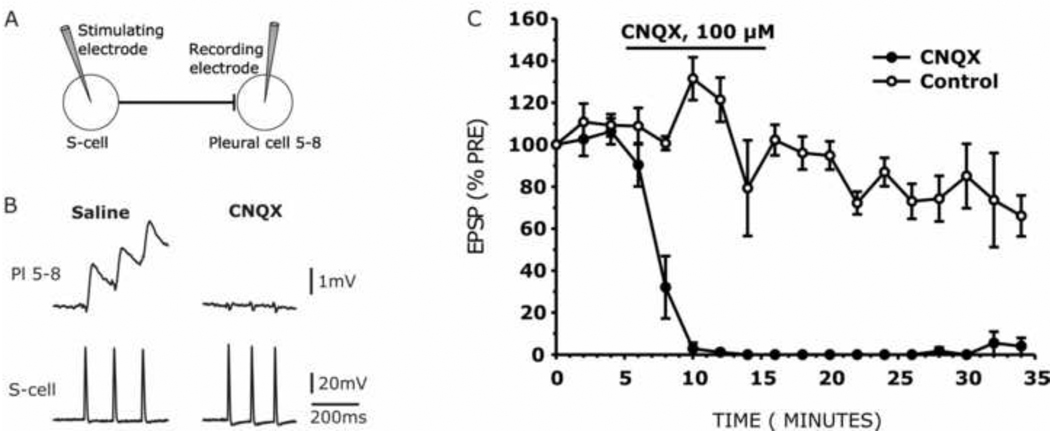

After confirming that CNQX blocks the ability of peripheral nerve stimulation to elicit the swim motor program, we proceeded to more directly test the hypothesis that this occurs, at least in part, by blocking S-cell glutamatergic synapses. Thus, we examined the effects of CNQX on the amplitude of the S-cell monosynaptic EPSP. An S-cell was impaled and stimulated with intracellular current injection to fire a 1 s, 10 Hz train of action potentials once every two minutes, while the evoked monosynaptic EPSPs in one of the Pleural 5–8 neurons was recorded with another micropipette (Fig. 6A). Preparations were then perfused for 10 min (2 ml/min) with either CNQX (100 µM; n = 5 preparations) or the 1% DMSO saline vehicle (n = 5 preparations), beginning just after the third pretest trial. We found that CNQX rapidly and completely eliminated the S-cell-to-Pleural 5–8 EPSP (Fig. 6B; F (1, 8) = 292.36, P < 0.001). The EPSP block began within 2 min after the start of CNQX perfusion into the recording chamber, and was still in effect after 20 min in wash (Fig. 6C; Tukey HSD post-hoc tests, P < 0.001). The control group showed no EPSP block effect. Instead, the control group EPSP displayed a slow and steady decline in amplitude, consistent with the known homosynaptic depression at S-cell synapses (Getting, 1976, Hoppe, 1998).

Figure 6.

CNQX blocked an S-cell synapse. (A) Schematic illustration of the monosynaptic S-cell to Pleural cell 5–8 connection, together with the stimulating (left) and recording (right) microelectrode placement. (B) Intracellular recording showing elimination of the S-cell-to-Pl 5–8 EPSP before (Saline), and again after 8 min in CNQX. In the drug, the EPSPs are eliminated, with only the stimulus artifacts remaining. In each 2 minute test, an impaled S-cell was stimulated with intracellular current to fire for 1 s at 10 Hz. Just the first three EPSPs of the test trains are shown. (C) Mean amplitude of the first EPSP in each train, normalized to its amplitude in the first pretest train, for CNQX (black circles, n = 5 preparations) and control experiments (white circles, n = 5 preparations). In the CNQX group, the mean normalized EPSP was blocked during the 10 min bath application of 100 µM CNQX as compared to the control group. Figure plots are expressed as means ± S.E.M.

Discussion

Several criteria must be met for a molecule to be established as a neuron’s neurotransmitter (Purves et al., 2007). The putative transmitter should be present in the neuron, depolarization should cause it to be released, postsynaptic neurons should have receptors for the transmitter, and their activation by the candidate transmitter should elicit a response similar to that produced by the presynaptic neuron itself. In the present study our findings supported these criteria with respect to the hypothesis that the S-cells utilize glutamate as a transmitter.

Transmitter localization in the presynaptic neuron

Because glutamate is involved in intermediary metabolism in all cells, it can be expected that many or most neurons would show some level of glutamate immunolabeling. However, neurons using glutamate as a transmitter often show elevated levels of glutamate in their cytoplasm. For example, the somata of the glutamatergic Aplysia pleural ganglion mechanosensory neurons have elevated levels of glutamate immunoreactivity (Levenson et al., 2000). Drake et al (Drake et al., 2005) showed that these neurons contain 29 mM glutamate, compared to 3 mM glutamate in non-sensory pleural ganglion neurons. In our study, the Tritonia S-cells displayed stronger glutamate immunolabeling than the majority of neurons in the cerebro-pleural ganglia, consistent with their use of it as a neurotransmitter. The cerebral ganglion neuron C1, which contains serotonin and is Tritonia’s counterpart to the Aplysia serotonergic metacerebral giant cell (Weinreich et al., 1973, Sudlow et al., 1998, Fickbohm and Katz, 2000, Fickbohm et al., 2001, Fickbohm et al., 2005), displayed no elevated glutamate immunolabeling, supporting the specificity of the antibody used.

Presynaptic depolarization releases the substance, which acts on receptors present on the postsynaptic neuron

Several studies have shown that the non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonists DNQX and CNQX block sensory neuron transmission in invertebrates (Dale and Kandel, 1993, Trudeau and Castellucci, 1993, Conrad et al., 1999, Storozhuk and Castellucci, 1999, Wessel et al., 1999, Baccus et al., 2000, Chitwood et al., 2001, Antonov et al., 2003, Li and Burrell, 2008). We found that CNQX blocked the monosynaptic connections of S-cells onto both postsynaptic neuron groups tested: other S-cells and Pl cells 5–8. CNQX also blocked the ability of peripheral nerve stimulation to elicit the swim motor program. These results indicate that presynaptic depolarization causes the S-cells to release glutamate, which acts on non-NMDA receptors present on the postsynaptic neurons. We did not test the efficacy of the NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist APV, which other studies have shown to be ineffective in blocking sensory neuron synaptic transmission in molluscs (Trudeau and Castellucci, 1993, Wessel et al., 1999, Chitwood et al., 2001), although effects of APV suggest that NMDA-like receptors play some role in sensory transmission in Aplysia (Murphy and Glanzman, 1999).

Postsynaptic responses to the putative transmitter mimic the responses to the transmitter released by the presynaptic neuron

We found that puffing l-glutamate onto the cell bodies of Pleural cells 5–8 depolarized these cells in both normal and zero calcium saline, mimicking the physiological response of these neurons to intracellular S-cell stimulation. In addition, guided by the observation that S-cells receive EPSPs from some other S-cells (Hoppe, 1998), we also similarly puffed l-glutamate onto S-cell somata and found that it depolarized these neurons as well. Invertebrate neurons have often been shown to express the same glutamate receptors on the non-innervated soma membrane as they express at their postsynaptic membranes (Dale and Kandel, 1993, Bravarenko et al., 2003).

Conclusion

In the present study, we showed that the S-cell neurons of the Tritonia diomedea swim circuit are likely to be glutamatergic, because 1) they show glutamate immunoreactivity, 2) presynaptic depolarization releases a transmitter that acts on non-NMDA glutamate receptors to elicit the physiological response, and 3) glutamate applied to the postsynaptic neurons elicits the same response as the S-cell transmitter. Our results are consistent with findings from other studies concluding that molluscan sensory neurons use glutamate as their neurotransmitter, including the marine mollusc Aplysia (Dale and Kandel, 1993, Levenson et al., 2000, Chin et al., 2002, Antzoulatos and Byrne, 2004) and the terrestrial snail Helix (Bravarenko et al., 2003). Until now, serotonin and the peptide TPep are the only transmitters identified in the Tritonia swim circuit (McClellan et al., 1994, Sudlow et al., 1998, Beck et al., 2000, Fickbohm and Katz, 2000). The present results thus expand our knowledge of the neurotransmitters used by the escape swim network neurons. This will facilitate further research in this model preparation on topics such as the cellular mechanisms of learning and memory, pattern generation, multifunctional networks, and prepulse inhibition.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank T. Tzounopoulos for numerous useful discussions, J. Wang for advice on electrophysiological issues, and E. Hill for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants NS36500 and DA16320.

Abbreviations

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- EPSP

excitatory postsynaptic potential

Literature Cited

- Antonov I, Antonova I, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Activity-dependent presynaptic facilitation and hebbian LTP are both required and interact during classical conditioning in Aplysia. Neuron. 2003;37:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzoulatos EG, Byrne JH. Learning insights transmitted by glutamate. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccus SA, Burrell BD, Sahley CL, Muller KJ. Action potential reflection and failure at axon branch points cause stepwise changes in EPSPs in a neuron essential for learning. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1693–1700. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JC, Cooper MS, Willows AO. Immunocytochemical localization of pedal peptide in the central nervous system of the gastropod mollusc Tritonia diomedea. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;425:1–9. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000911)425:1<1::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravarenko NI, Korshunova TA, Malyshev AY, Balaban PM. Synaptic contact between mechanosensory neuron and withdrawal interneuron in terrestrial snail is mediated by L-glutamate-like transmitter. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;341:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Willows AOD. The role of glutamate in the swim neural circuit of Tritonia. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1993;19:1700. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner E, Buchner S, Burg MG, Hofbauer A, Pak WL, Pollack I. Histamine is a major mechanosensory neurotransmitter candidate in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;273:119–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00304618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows M. The Neurobiology of an insect brain. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cain SD, Wang JH, Lohmann KJ. Immunochemical and electrophysiological analyses of magnetically responsive neurons in the mollusc Tritonia diomedea. J. Comp. Physiol. A. Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 2006;192:235–245. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Burdohan JA, Eskin A, Byrne JH. Inhibitor of glutamate transport alters synaptic transmission at sensorimotor synapses in Aplysia. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:3165–3168. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood RA, Li Q, Glanzman DL. Serotonin facilitates AMPA-type responses in isolated siphon motor neurons of Aplysia in culture. J. Physiol. 2001;534:501–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P, Wu F, Schacher S. Changes in functional glutamate receptors on a postsynaptic neuron accompany formation and maturation of an identified synapse. J. Neurobiol. 1999;39:237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N, Kandel ER. L-glutamate may be the fast excitatory transmitter of Aplysia sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1993;90:7163–7167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cosmo A, Nardi G, Di Cristo C, De Santis A, Messenger JB. Localization of L-glutamate and glutamate-like receptors at the squid giant synapse. Brain Res. 1999;839:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsett DA, Willows AO, Hoyle G. The neuronal basis of behavior in Tritonia. IV. The central origin of a fixed action pattern demonstrated in the isolated brain. J. Neurobiol. 1973;4:287–300. doi: 10.1002/neu.480040309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake TJ, Jezzini S, Lovell P, Moroz LL, Tan W. Single cell glutamate analysis in Aplysia sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2005;144:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Feng L, Yang F, Lu B. Activity- and Ca(2+)-dependent modulation of surface expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptors in hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1423–1434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JG, Michel WC. Odor-stimulated glutamatergic neurotransmission in the zebrafish olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;454:294–309. doi: 10.1002/cne.10445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickbohm DJ, Katz PS. Paradoxical actions of the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan on the activity of identified serotonergic neurons in a simple motor circuit. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1622–1634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01622.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickbohm DJ, Lynn-Bullock CP, Spitzer N, Caldwell HK, Katz PS. Localization and quantification of 5-hydroxytryptophan and serotonin in the central nervous systems of Tritonia and Aplysia. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;437:91–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickbohm DJ, Spitzer N, Katz PS. Pharmacological manipulation of serotonin levels in the nervous system of the opisthobranch mollusc Tritonia diomedea. Biol. Bull. 2005;209:67–74. doi: 10.2307/3593142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost WN, Brandon CL, Mongeluzi DL. Sensitization of the Tritonia escape swim. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1998;69:126–135. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost WN, Brandon CL, Van Zyl C. Long-term habituation in the marine mollusc Tritonia diomedea. Biol. Bull. 2006;210:230–237. doi: 10.2307/4134560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost WN, Brown GD, Getting PA. Parametric features of habituation of swim cycle number in the marine mollusc Tritonia diomedea. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1996;65:125–134. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost WN, Katz PS. Single neuron control over a complex motor program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:422–426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost WN, Hoppe TA, Wang J, Tian L-M. Swim intiation neurons in Tritonia diomedea. Amer. Zool. 2001;41:952–961. [Google Scholar]

- Frost WN, Tian LM, Hoppe TA, Mongeluzi DL, Wang J. A cellular mechanism for prepulse inhibition. Neuron. 2003;40:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getting PA. Afferent neurons mediating escape swimming of the marine mollusc, Tritonia. J. Comp. Physiol. [A] 1976;110:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Getting PA. Neural control of swimming in Tritonia. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1983;37:89–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groome JR, Vaughan DK. Glutamate as a transmitter in the sensory pathway from prostomial lip to serotonergic Retzius neurons in the medicinal leech Hirudo. Invert. Neurosci. 1996;2:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02214115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama D, Aonuma H, Ito E, Elekes K. Localization of glutamate-like immunoreactive neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system of the adult and developing pond snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. Biol. Bull. 2007;213:172–186. doi: 10.2307/25066633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochner B, Brown ER, Langella M, Shomrat T, Fiorito G. A learning and memory area in the octopus brain manifests a vertebrate-like long-term potentiation. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3547–3554. doi: 10.1152/jn.00645.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe TA. An evaluation of the role of synaptic depression at afferent synapses in habituation of the escape swim response of Tritonia diomedea, Masters Thesis. The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kai-Kai MA, Howe R. Glutamate-immunoreactivity in the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia, and intraspinal neurons and fibres in the dorsal horn of the rat. Histochem. J. 1991;23:171–179. doi: 10.1007/BF01046588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PS, Frost WN. Intrinsic neuromodulation in the Tritonia swim CPG: serotonin mediates both neuromodulation and neurotransmission by the dorsal swim interneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995a;74:2281–2294. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PS, Frost WN. Intrinsic neuromodulation in the Tritonia swim CPG: the serotonergic dorsal swim interneurons act presynaptically to enhance transmitter release from interneuron C2. J. Neurosci. 1995b;15:6035–6045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06035.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PS, Getting PA, Frost WN. Dynamic neuromodulation of synaptic strength intrinsic to a central pattern generator circuit. Nature. 1994;367:729–731. doi: 10.1038/367729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Kawasaki S, Takashima K, Sasaki K. Physiological and pharmacological characteristics of quisqualic acid-induced K(+)-current response in the ganglion cells of Aplysia. Jpn. J. Physiol. 2001;51:511–521. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.51.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RY, Sawin ER, Chalfie M, Horvitz HR, Avery L. EAT-4, a homolog of a mammalian sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter, is necessary for glutamatergic neurotransmission in caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:159–167. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00159.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J, Sherry DM, Dryer L, Chin J, Byrne JH, Eskin A. Localization of glutamate and glutamate transporters in the sensory neurons of Aplysia. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;423:121–131. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000717)423:1<121::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Burrell BD. CNQX and AMPA inhibit electrical synaptic transmission: a potential interaction between electrical and glutamatergic synapses. Brain Res. 2008;1228:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima PA, Nardi G, Brown ER. AMPA/kainate and NMDA-like glutamate receptors at the chromatophore neuromuscular junction of the squid: role in synaptic transmission and skin patterning. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:507–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley RD, Longely AJ. Evolution of behavior: An homologous peptidergic escape swim interneuron on swimming gastropod nudibranchs (Tritonia, Hermissenda) and a related non-swimming species (Aeolidia) Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1987;13:822. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz EM, Tyrer NM. Immunohistochemical localization of serotonin and choline acetyltransferase in sensory neurones of the locust. J. Comp. Neurol. 1988;267:335–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.902670304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan AD, Brown GD, Getting PA. Modulation of swimming in Tritonia: excitatory and inhibitory effects of serotonin. J. Comp. Physiol. [A] 1994;174:257–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00193792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megalou EV, Brandon C, Eliot LS, Frost WN. Program No. 888.5. 2005 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2005. The Tritonia diomedea swim afferent neurons may use glutamate as their neurotransmitter. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Mellem JE, Brockie PJ, Zheng Y, Madsen DM, Maricq AV. Decoding of polymodal sensory stimuli by postsynaptic glutamate receptors in C. elegans. Neuron. 2002;36:933–944. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzig J, Buchner S, Wiebel F, Wolf R, Burg M, Pak WL, Buchner E. Genetic depletion of histamine from the nervous system of Drosophila eliminates specific visual and mechanosensory behavior. J. Comp. Physiol. [A] 1996;179:763–773. doi: 10.1007/BF00207355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongeluzi DL, Frost WN. Dishabituation of the Tritonia escape swim. Learn. Mem. 2000;7:43–47. doi: 10.1101/lm.7.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongeluzi DL, Hoppe TA, Frost WN. Prepulse inhibition of the Tritonia escape swim. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:8467–8472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08467.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GG, Glanzman DL. Cellular analog of differential classical conditioning in Aplysia: disruption by the NMDA receptor antagonist DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:10595–10602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10595.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscopo S, Moccia F, Di Cristo C, Caputi L, Di Cosmo A, Brown ER. Pre- and postsynaptic excitation and inhibition at octopus optic lobe photoreceptor terminals; implications for the function of the 'presynaptic bags'. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:2196–2203. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncer JC, Shinozaki H, Miles R. Dual modulation of synaptic inhibition by distinct metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 1995;485(Pt 1):121–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu IR, Frost WN. Highly dissimilar behaviors mediated by a multifunctional network in the marine mollusk Tritonia diomedea. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1985–1993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01985.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia A-S, McNamara JO, White LE. Neuroscience. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Raab M, Neuhuber WL. Glutamatergic functions of primary afferent neurons with special emphasis on vagal afferents. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2007;256:223–275. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)56007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin CH, Wicks SR. Mutations of the caenorhabditis elegans brain-specific inorganic phosphate transporter eat-4 affect habituation of the tap-withdrawal response without affecting the response itself. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4337–4344. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04337.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storozhuk MV, Castellucci VF. The synaptic junctions of LE and RF cluster sensory neurones of Aplysia californica are differentially modulated by serotonin. J. Exp. Biol. 1999;202:115–120. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudlow LC, Jing J, Moroz LL, Gillette R. Serotonin immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the marine molluscs Pleurobranchaea californica and Tritonia diomedea. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;395:466–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau LE, Castellucci VF. Excitatory amino acid neurotransmission at sensory-motor and interneuronal synapses of Aplysia californica. J. Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1221–1230. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich D, McCaman MW, McCaman RE, Vaughn JE. Chemical, enzymatic and ultrastructural characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine-containing neurons from the ganglia of Aplysia californica and Tritionia diomedia. J. Neurochem. 1973;20:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel R, Kristan WB, Jr, Kleinfeld D. Supralinear summation of synaptic inputs by an invertebrate neuron: dendritic gain is mediated by an "inward rectifier" K(+) current. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5875–5888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05875.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willows AO, Dorsett DA, Hoyle G. The neuronal basis of behavior in Tritonia. I. Functional organization of the central nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 1973;4:207–237. doi: 10.1002/neu.480040306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]