Abstract

We previously demonstrated that aldosterone, which stimulates collagen production through the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR)-dependent pathway, also induces elastogenesis via a parallel MR-independent mechanism involving insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) signaling. The present study provides a more detailed explanation of this signaling pathway. Our data demonstrate that small interfering RNA-driven elimination of MR in cardiac fibroblasts does not inhibit aldosterone-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation and subsequent increase in elastin production. These results exclude the involvement of the MR in aldosterone-induced increases in elastin production. Results of further experiments aimed at identifying the upstream signaling component(s) that might be activated by aldosterone also eliminate the putative involvement of pertussis toxin-sensitive Gαi proteins, which have previously been shown to be responsible for some MR-independent effects of aldosterone. Instead, we found that small interfering RNA-dependent elimination of another heterotrimeric G protein, Gα13, eliminates aldosterone-induced elastogenesis. We further demonstrate that aldosterone first engages Gα13 and then promotes its transient interaction with c-Src, which constitutes a prerequisite step for aldosterone-dependent activation of the IGF-IR and propagation of consecutive downstream elastogenic signaling involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt. In summary, the data we present reveal new details of an MR-independent cellular signaling pathway through which aldosterone stimulates elastogenesis in human cardiac fibroblasts.

Aldosterone is a major component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays an important role in the regulation of electrolyte and fluid balance (1, 2). The majority of aldosterone-induced effects occur after it binds to the intracellular MR. The activated aldosterone-MR complex translocates to the nucleus, where it modulates the transcription and translation of “aldosterone-induced” proteins involved in blood pressure homeostasis.

Aldosterone has also been implicated in the stimulation of collagen synthesis and myocardial fibrosis through a process that is independent of its effect on blood pressure (3–5). Two clinical studies, the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (6) and the Eplerenone Post-acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (7), demonstrated that low doses of MR2 antagonists lead to a dramatic reduction in the mortality rate of patients who suffered acute myocardial infarctions. Despite the suggestion that these MR antagonists may alleviate maladaptive remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of post-infarct hearts (8, 9), the molecular mechanisms by which they improve overall heart function in those patients have not been fully resolved.

It has been also shown that aldosterone can induce numerous effects in a wide range of nonepithelial tissues, including heart, and that it may act through membrane receptors other than the traditional MR (alternative receptors) in epithelial and nonepithelial tissue in a nongenomic manner (10–13).

Although the classical genomic model of aldosterone action has long been accepted, the rapid, nongenomic mechanism of aldosterone action is not yet fully elucidated (2). However, it has been proposed that some of these nongenomic effects of aldosterone also require the presence of MR or a closely related protein (14). In contrast, other studies have shown that the nongenomic aldosterone effects still occur in cell lines lacking the classical MR and in yeast devoid of MR or in normal cells treated with MR antagonists (2, 11, 15). Such results strongly suggest the involvement of other receptor(s), distinct from the classic MR, that may interact with aldosterone and trigger the nongenomic effects of this hormone. Although full structural characterization of this putative receptor (or receptors) has not been completed yet (16), data suggest that some MR-independent effects of aldosterone occur after activation of the pertussis toxin-sensitive heterotrimeric G proteins (13, 17).

Results of our previous studies have revealed a novel mechanism in which aldosterone and its antagonists modulate the production of elastin, an important ECM component that provides resilience to many tissues, including stroma of the heart. We discovered that aldosterone can stimulate elastogenesis in cultures of human cardiac fibroblasts via an MR-independent mechanism involving IGF-IR activation (18). We have therefore uncovered another level of complexity in which aldosterone in conjunction with MR antagonists may modulate the remodeling of the injured heart.

In the present study we provide compelling evidence demonstrating that cultured cardiac fibroblasts, in which the production of MR has been inhibited by siRNA, still exhibit the aldosterone-induced increase in elastin production. We also present the first evidence that this MR-independent elastogenic effect of aldosterone can be triggered by a signaling pathway that involves initial activation of the heterotrimeric G protein Gα13 and consecutive activation of c-Src, IGF-IR, and PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All chemical grade reagents, aldosterone, proteinase inhibitors, agarose-linked protein A, pertussis toxin, recombinant human IGF-I, PD 98059, PD123319, AlCl3, and NaF, as well as secondary antibodies fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse, and fluorescein-conjugated rabbit anti-goat were obtained from Sigma. Wortmannin, PP2, SP600125, and Y-27632 were purchased from Calbiochem. Losartan was purchased from Cayman Chemicals Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). A cell-permeable Rho inhibitor (exoenzyme C3 transferase, CT04) was purchased from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO). Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium, fetal bovine serum, 0.2% trypsin with 0.02% EDTA, and other cell culture products were acquired from Invitrogen. Polyclonal antibody to tropoelastin was purchased from Elastin Products (Owensville, MI). Polyclonal antibody to collagen type I was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Polyclonal antibodies against phosphorylated c-Src (Tyr416), total c-Src, phosphorylated Akt (Ser437), total Akt, and monoclonal antibody against β-actin and GAPDH were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Monoclonal antibody against phosphotyrosine (PY99), polyclonal antibody against IGF-IR-β and MR, rabbit and goat polyclonal antibodies against Gα13, rabbit polyclonal antibody against Gα12, normal rabbit or goat agarose-conjugated IgGs, and rabbit polyclonal antibody and mouse monoclonal antibody against c-Src as well as human whole cell lysates were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal antibody against MR was purchased from ABR Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). Species- and type-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, an enhanced chemiluminescence kit, and the radiolabeled reagent [3H]valine were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Precast 4–12% Tris-glycine gel was purchased from Invitrogen. A DNeasy tissue system for DNA assay, RNeasy mini kit for isolating total RNA, and a one-step RT-PCR kit were purchased from Qiagen. Two different predesigned Gα13 siRNA oligonucleotide duplexes were purchased from Ambion, Inc. (Austin, TX), and a custom designed Gα13 siRNA oligonucleotide duplex, as well as predesigned ON-TARGETplus SMART pool MR siRNA, was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). A DeliverX plus siRNA transfection reagent kit, including GAPDH-specific siRNA and nonsilencing (scrambled) siRNA oligonucleotide duplexes, was purchased from Panomics, Inc. (Fremont, CA). BSA-conjugated aldosterone was purchased from Fitzgerald Industries Intl. (Concord, MA). As specified by the manufacturer, 25 aldosterone molecules are covalently linked to each BSA molecule through a carboxymethyl oxyme residue on the C-3 of the hormone, forming a stable conjugate (19).

Cultures of Human Cardiac Fibroblasts

We used cardiac fibroblasts isolated from human fetal hearts (which are responsible for the production of cardiac ECM) to make our studies clinically relevant. Human fetal cardiac fibroblasts of 20–22 weeks gestation, a generous gift from Dr. John Coles, were prepared in accordance with an institutional review board-approved protocol (20). Confluent cultures were passaged by trypsinization and maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 1% antibiotics/antimycotics and 10% fetal bovine serum. Passage 1–3 cells were used in all experiments. The purity of these cultures at passage 1 was 95%. Cardiac fibroblasts were determined by positive staining for vimentin and negative for von Willebrand factor and α-smooth muscle cell actin, as previously described (21).

In experiments aimed at assessing ECM production, fibroblasts were initially plated (100,000 cells/dish) and maintained in a normal medium until confluency, the point at which they produce abundant ECM. Confluent cultures were then treated for 72 h with or without 50 nm of aldosterone (22).

In separate experiments we also tested the influence of an equimolar concentration of aldosterone that was coupled to BSA, which prevents it from penetrating into the cell interior, as demonstrated in previous studies (23, 24). The G protein inhibitor pertussis toxin (13), MAPK kinase inhibitor PD98059 (25, 26), JNK inhibitor SP600125 (27, 28), PI 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin (29, 30), c-Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 (31), and Rho-associated kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (32, 33), as well as the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan (34, 35) and the AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319 (36, 37), were added 1 h prior to aldosterone treatment. Cell-permeable Rho inhibitor (CTO4) was added 2 h prior to aldosterone treatment, as specified by the manufacturer. The cells were also treated for 3 h with aluminum fluoride solution (AlCl3 and NaF) prepared immediately before use, as previously described (38). All of the control cell cultures received an equal amount of the solvent vehicle.

Immunostaining

At the end of the 72-h incubation period with the indicated treatment, confluent cultures were fixed in cold 100% methanol at −20 °C (for elastin and MR staining) or in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature (for collagen staining) for 30 min and blocked with 1% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. The cultures were then incubated for 1 h with either 10 μg/ml of polyclonal antibody to tropoelastin, 10 μg/ml of monoclonal antibody to MR, or 10 μg/ml of polyclonal antibody to collagen type I. All of the cultures were then incubated for an additional hour with either fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse, or fluorescein-conjugated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibodies to detect elastin, MR, and collagen type I staining, respectively. The nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide. Secondary antibody alone was used as a control. All of the cultures were then mounted in elvanol and examined with a Nikon Eclipse E1000 microscope attached to a cooled CCD camera (QImaging, Retiga EX) and a computer-generated video analysis system (Image-Pro Plus software, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Initial magnification for all images was 600×.

Quantitative Assay of Insoluble Elastin

Fetal human cardiac fibroblasts were grown to confluency in 35-mm culture dishes (100,000 cells/dish) in quadruplicate. Then 2 μCi of [3H]valine/ml of fresh medium were added to each dish and treated as specified in the figure legends. Following a 72-h incubation, the cells were extensively washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and the cells including deposited insoluble ECM were scraped and boiled in 500 μl of 0.1 n NaOH for 30 min to solubilize all matrix components except elastin (39). The resulting pellets containing the insoluble elastin were then solubilized by boiling in 200 μl of 5.7 n HCl for 1 h, and the aliquots were mixed in scintillation fluid and counted (40). The aliquots taken from each culture were also used for DNA determination according to Rodems and Spector (41) using the DNeasy Tissue System from Qiagen. Final results reflecting the amounts of metabolically labeled insoluble elastin in the individual cultures were normalized according to their DNA content and expressed as cpm/1 μg of DNA.

One-step RT-PCR Analysis

Confluent fetal human cardiac fibroblast cultures were treated with or without the specified treatment in the figure legend for 24 h, unless otherwise indicated. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, 1 μg of total RNA was added to each one-step RT-PCR kit, and the reactions were set up according to the manufacturer's instructions in a total volume of 25 μl. The reverse transcription step was performed for elastin and GAPDH reactions at 50 °C for 30 min, followed by 15 min at 95 °C. The elastin PCR (sense primer: 5′-GGTGCGGTGGTTCCTCAGCCTGG-3′; antisense primer: 5′-GGGCCTTGAGATACCCCAGTG-3′; designed to produce a 255-bp product) was performed under the following conditions: 25 cycles of 94 °C denaturation for 20 s, 63 °C annealing for 20 s, and 72 °C extension for 1 min and one cycle of 72 °C final extension for 10 min. The Gα13 PCR (sense primer: 5′-CGTGATCAAAGGTATGAGGG-3′; antisense primer: 5′-CAGATTCACCCAGTTGAAATT-3′; designed to produce a 249-bp product) was performed under the following conditions: 25 cycles of 94 °C denaturation for 30 s, 60 °C annealing for 30 s, and 72 °C extension for 1 min and 1 cycle of 72 °C final extension for 10 min. The collagen type I (pro-α1(I) chain) PCR (sense primer: 5′-CCCACCAATCACCTGCGTACAGA-3′, antisense primer: 5′-TTCTTGGTCGGTGGGTGACTCTGA-3′) was performed under the following conditions: 20 cycles of 94 °C denaturation for 30 s, 58 °C annealing for 30 s, and 72 °C extension for 10 min and 1 cycle of 72 °C final extension for 10 min. The GAPDH PCR (sense primer: 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG-3′; antisense primer: 5′-GACCACAGTCCATGCCATCACT-3′; designed to produce a 450-bp product) was performed under the following conditions: 21 cycles of 94 °C denaturation for 20 s, 58 °C annealing for 30 s, and 72 °C extension for 1 min and 1 cycle of 72 °C final extension for 10 min. 5-μl samples of the elastin, Gα13, collagen type I, and GAPDH PCR products from each reaction were run on a 2% agarose gel and post-stained with ethidium bromide. The amount of elastin, Gα13, and collagen type I mRNA was standardized relative to the amount of GAPDH mRNA.

Western Blotting

Confluent fetal human cardiac fibroblast cultures were exposed with or without the treatment specified in the figure legends for the indicated time points. At the end of each experiment, the cells were lysed using an radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaF, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate) containing a mixture of antiproteases (20 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm dithiothreitol) and antiphosphates (200 m orthovanadate, 2 μg/ml pepstatin). Then 40–60 μg of protein extract was resuspended in sample buffer (0.5 m Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 10% glycerol, 4% 2-β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.05% bromphenol blue), and the mixture was boiled for 5 min. The protein lysates were resolved by precast SDS-PAGE gel (4–12% gradient), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked for an hour, and then immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-MR antibody, anti-phospho-c-Src (Tyr416) antibody, anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) antibody, anti-Gα13 (goat) antibody, anti-SCAP2 antibody, or with buffer (TBS-T) at 4 °C overnight. All of the blots were then incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for an hour and examined using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. As indicated in the figure legends, the blots were stripped and reprobed using specified antibodies. For all Western blot experiments human whole cell lysates were also electrophoresed and immunoblotted with the mentioned antibodies that served as a positive control and accordingly produced the appropriate molecular weight band (data not shown). The degree of expression or phosphorylation of immunodetected signaling molecules was measured by densitometry.

Immunoprecipitation

To evaluate the level of IGF-IR-β phosphorylation, confluent fetal human cardiac fibroblast cultures were incubated for the indicated time in the presence or absence of 50 nm aldosterone or for 10 min with 100 ng/ml of IGF-I, as specified in the figure legends. For co-immunoprecipitation experiments, confluent cultures were incubated with the treatment indicated in the figure legends. At the end of each experiment the cells were lysed as specified above, and 300 μg of protein extract were then precleared for 1 h with normal rabbit agarose-conjugated IgG at 4 °C and incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against IGF-IR-β, c-Src, or with Gα13 for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by the addition of 4% protein A-beaded agarose and left overnight, as previously described (42). The resulting protein-antibody conjugate was centrifuged at 4 °C and washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline. The final pellet was resuspended in sample buffer, and the proteins were resolved as specified above. Following immunoprecipitation of IGF-IR-β, the membrane was immunoblotted using monoclonal anti-p-Tyr antibody, stripped, and reprobed using anti-IGF-IR-β. Following immunoprecipitation of c-Src, the membranes were immunoblotted using polyclonal goat antibodies against anti-Gα13, whereas those immunoprecipitated with anti-Gα13 were developed with monoclonal anti-c-Src antibody. As indicated in the figure legends, the blots were stripped and reprobed for equal loading.

For all of the immunoprecipitation experiments, rabbit IgG was also immunoprecipitated and used as a negative control and accordingly did not produce a band (data not shown). The degree of expression or phosphorylation of immunodetected signaling molecules was measured by densitometry.

Silencing MR and Gα13 Expression Using siRNA-specific Oligonucleotides and MR- and Gα13-specific siRNA Oligonucleotides

ON-TARGET plus SMART pool MR siRNA (gene ID 4306) containing a mixture of four SMART-selection predesigned siRNAs exclusively targeting MR (MR siRNA) was purchased from Dharmacon. Two different Silencer® predesigned siRNA duplexes against human Gα13 (standard purity, siRNA identification numbers 119735 and 119733) were obtained from (Ambion). The custom designed oligonucleotide duplex (Dharmacon) was synthesized to correspond to target sequences on the full-length human Gα13 protein. The custom designed oligonucleotide target sequence was as follows: 5′-GAA GAU CGA CUG ACC CAA UC-3′, which was previously shown to completely eliminate Gα13 in HeLa cells (43). A nonsilencing control and GAPDH siRNA duplex sequences (Panomics) were used as controls for the transfections.

Transfection of MR and Gα13 siRNA Oligonucleotides

Cardiac fibroblasts were seeded in 6-well plates, maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). 80–90% confluent cardiac fibroblast cultures were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and 30 nm of Gα13, GAPDH, or nonsilencing siRNA or 90 nm of MR or nonsilencing siRNA were transfected into cells using DeliverX plus siRNA transfection reagent (Panomics), according to the manufacturer's instructions. MR production was monitored by Western blotting, whereas Gα13 expression was monitored by one-step RT-PCR and Western blotting post-transfection, as specified in the figure text. The Gα13 siRNA 1 oligonucleotide (Ambion) provided the greatest knockdown of Gα13 and was used in all siRNA experiments to silence Gα13 expression.

Data Analysis

In all of the biochemical studies, quadruplicate samples in each experimental group were assayed in three separate experiments. The means and standard deviations were calculated for each experimental group, and statistical analyses were carried out by analysis of variance. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Absence of MR Does Not Prevent an Aldosterone-induced Increase in IGF-IR Phosphorylation and Subsequent Elastin Production in Cultures of Cardiac Fibroblasts

In our previous study we demonstrated that treatment with 1–50 nm of aldosterone increases elastin mRNA levels, tropoelastin synthesis, and elastic fiber deposition in a dose-dependent manner. Strikingly, neither spironolactone (an MR antagonist) nor RU 486 (a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist) eliminated aldosterone-induced increases in elastin production, which were induced after aldosterone-dependent phosphorylation of IGF-IR (18).

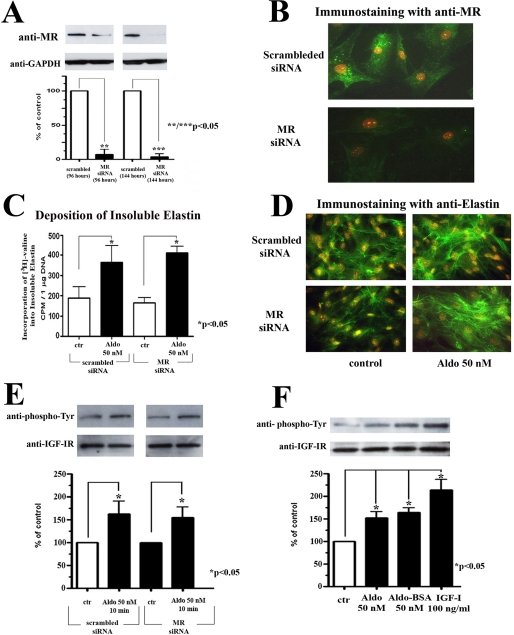

The present study was intended to produce a detailed characterization of the signaling pathway through which aldosterone up-regulates elastin production. We first used MR-specific siRNA oligonucleotides to eliminate the production of MR in cardiac fibroblast cultures to exclude the conventional involvement of MR in aldosterone-induced elastogenesis. We first demonstrated using MR-specific siRNA oligonucleotides that MR protein levels decreased to ∼11% of the scrambled control levels 96 h after transfection and to ∼6% of scrambled control levels 144 h after transfection (Fig. 1A). Importantly, results of the consecutive experiments demonstrated that this effective siRNA-dependent inhibition of MR synthesis in cultures of cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 1, A and B) did not diminish their elastogenic response to 50 nm of aldosterone (Fig. 1, C and D). Furthermore, we also showed that a 10-min exposure to 50 nm of aldosterone, which produced a transient increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of the IGF-IR in control cultures, produced a similar increase in cultures treated with MR siRNA (Fig. 1E). Then we utilized BSA-conjugated aldosterone to determine whether this membrane-impermeable form of aldosterone would trigger IGF-IR phosphorylation by direct stimulation of a cell surface-residing component (or components). Indeed, treatment for 10 min with 50 nm of BSA-conjugated aldosterone produced the same effect on IGF-IR phosphorylation as treatment with equimolar free aldosterone (Fig. 1F).

FIGURE 1.

Eliminating the production of MR with siRNA-specific oligonucleotides in cultures of human cardiac fibroblast does not affect aldosterone-induced increases in elastin production. A, representative Western blots of cellular lysates from cultures that were transfected for either 96 or 144 h with scrambled and MR siRNA-specific oligonucleotides. B, immunohistochemistry with anti-MR antibody confirmed that production of MR was completely attenuated in cultures that were transfected for 144 h with MR siRNA. C, results of a quantitative assay of newly deposited insoluble elastin metabolically labeled with [3H]valine in cultures that were initially transfected for 72 h with scrambled or Gα13 siRNA and then transfected again for an additional 72 h and kept in the presence or absence of 50 nm of aldosterone. D, representative photomicrographs immunostained with anti-elastin antibody confirm the results presented in C. E and F, the cultures were either transfected for 96 h with scrambled siRNA control and Gα13 siRNA-specific oligonucleotides and treated for 10 min with or without 50 nm of aldosterone (E) or treated for 10 min with or without 50 nm of aldosterone, 50 nm of aldosterone conjugated to BSA (Aldo-BSA), or 100 ng/ml of IGF-I (F). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an IGF-IR antibody and probed with an anti-phosphotyrosine (anti-phospho-Tyr) antibody or anti-IGF-IR antibody. The graphs depict the means ± S.D. of data from three individual experiments, expressed as percentages of control phosphorylation values obtained by normalizing to the corresponding total level of IGF-IR. ctr, control.

Search for the Cell Membrane Component(s) Involved in Aldosterone-induced Elastogenesis

The results described above suggested that MR-independent activation of the IGF-IR leading to increased elastin production by aldosterone does not require the entry of this hormone into the cell interior. We therefore speculated that such an effect might be triggered through the direct interaction of aldosterone with certain cell membrane-residing component(s). Consequently, our next experiments were aimed at identifying the initial stages of aldosterone-induced signaling leading to enhanced elastogenesis.

Inspired by reports indicating that some MR-independent effects of aldosterone may be induced through the modulation of angiotensin II-dependent signaling (12, 44, 45), we first examined the possibility that aldosterone-induced elastogenesis might involve the cross-activation of angiotensin II receptor(s). Our results demonstrated that the addition of angiotensin II type I (losartan) and angiotensin II type 2 (PD 123319) receptor antagonists to cultures of cardiac fibroblasts did not abrogate their elastogenic response to aldosterone (data not shown). Thus, the possibility that angiotensin II receptors were involved was eliminated.

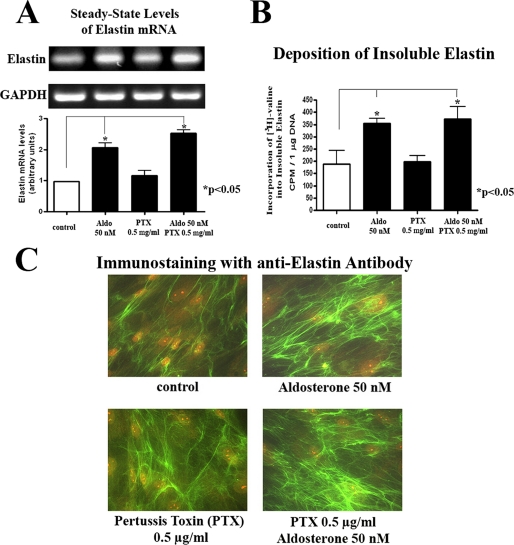

Because other reports also suggested that certain MR-independent effects of aldosterone can be mediated by activation of the pertussis toxin-sensitive heterotrimeric G protein Gαi (13, 17), we then tested its potential involvement in aldosterone-induced elastogenesis. However, the data we obtained demonstrated that pretreatment of cultured cardiac fibroblasts with pertussis toxin does not attenuate the pro-elastogenic effect of aldosterone (Fig. 2). Thus, the putative involvement of Gαi proteins in this process was also eliminated.

FIGURE 2.

The Gαi inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTX) does not attenuate aldosterone-induced increases in elastin production in human cardiac fibroblast cultures. A, results of one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing elastin mRNA transcripts (normalized for GAPDH) in cultures treated for 24 h with or without 50 nm of aldosterone prior to 1 h of preincubation with 0.5 mg/ml of PTX. B, results of a quantitative assay of [3H]valine-labeled insoluble elastin. C, immunohistochemistry with anti-elastin antibody of 1-h pretreated cultures with 0.5 mg/ml of PTX, following 72 h of incubation with 50 nm of aldosterone.

We therefore concentrated our investigation on another member of the G protein family, Gα13, which has recently been shown to mediate nongenomic actions of estrogen (46).

Silencing Gα13 in Cardiac Fibroblast Cultures Eliminates Aldosterone-induced Elastogenesis

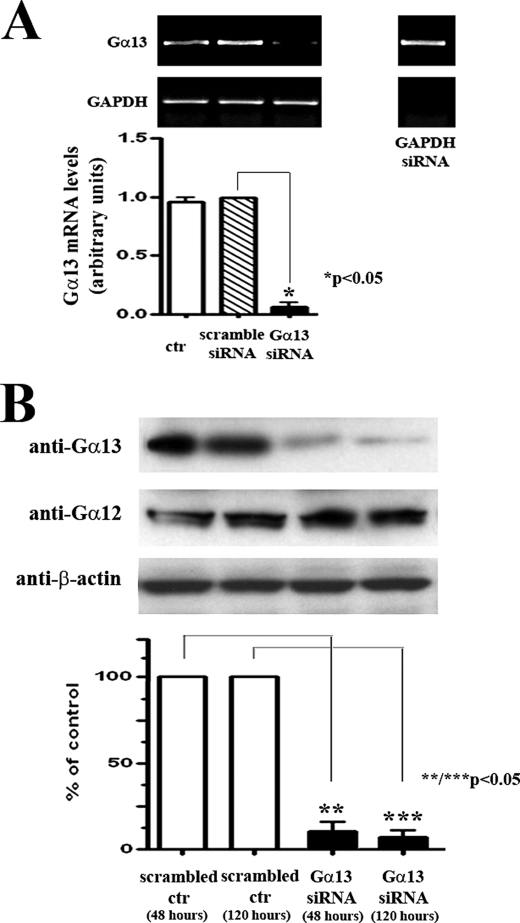

To examine whether Gα13 would be involved in the initiation of the cellular signaling leading to an aldosterone-induced increase in elastin production, we specifically silenced Gα13 mRNA expression to about 8% of scrambled siRNA control levels 24 h after transfection (Fig. 3A) and protein production to ∼14 and 9% of scrambled control levels 48 and 120 h after transfection, respectively, in cardiac fibroblast cultures without affecting the levels of its related family member, Gα12 (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Silencing Gα13 expression/production in human cardiac fibroblast cultures. A, one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing Gα13 and GAPDH transcript levels in a negative control culture, a scrambled siRNA control culture, and cultures containing Gα13 and GAPDH siRNA-specific oligonucleotides, 24 h after transfection. GAPDH siRNA served as a positive control. B, representative Western blot of cellular lysates obtained from cultures that were transfected for either 48 h or for 48 h and then transfected again for an additional 72 h (120 h) with scrambled and Gα13 siRNA-specific oligonucleotides and immunoblotted with anti-Gα13 antibody. The blots were then stripped and reprobed with anti-Gα12 and anti-β-actin antibodies. The graphs depict the densitometric evaluation of results obtained from three individual experiments. The means ± S.D. of data were expressed by normalizing Gα13 mRNA levels to the corresponding levels of GAPDH mRNA transcripts (A) and as a percentage of scrambled control Gα13 protein levels (B). ctr, control.

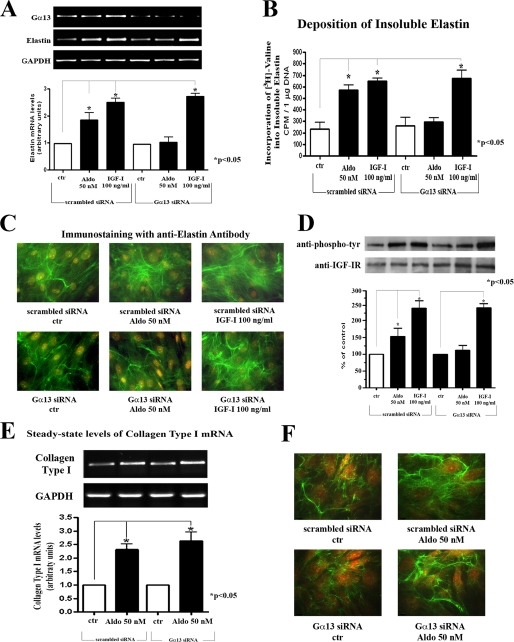

Our results indicated that the aldosterone-induced increase in elastin mRNA (observed in cultures transfected with scrambled siRNA) did not occur in cultures in which Gα13 expression was effectively silenced (Fig. 4A). Consequently, cultures of cardiac fibroblasts that were transfected with Gα13 siRNA did not demonstrate any increase in elastin deposition in response to aldosterone treatment (Fig. 4, B and C). Meaningfully, parallel cultures transfected either with Gα13-specific or with scrambled siRNA demonstrated heightened elastin message levels and increased deposition of mature (metabolically labeled and immunodetectable) elastin in response to IGF-I treatment. Additionally, we found that in contrast to cultures transfected with scrambled siRNA, which demonstrated a significant increase in IGF-IR phosphorylation, cultures transfected with Gα13-specific siRNA did not demonstrate any up-regulation in IGF-IR phosphorylation following aldosterone treatment (Fig. 4D). We also demonstrated that Gα13 is not involved in the collagenogenic effect of aldosterone (Fig. 4, E and F). These results clearly demonstrated that Gα13 is engaged in the initial stage of the aldosterone-induced increase in elastogenesis that occurs prior to IGF-IR activation.

FIGURE 4.

Silencing Gα13 expression/production in cardiac fibroblast cultures attenuates the aldosterone-induced increase in elastin production and IGF-IR phosphorylation but does not affect the collagen production. A, results of a one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing Gα13, elastin, and GAPDH mRNA transcript levels of cultures transfected for 72 h with scrambled siRNA control and Gα13 siRNA-specific oligonucleotides and treated for the last 24 h with or without 50 nm of aldosterone or 100 ng/ml of IGF-I. B, results of a quantitative assay of newly deposited [3H]valine-labeled insoluble elastin in cultures that were initially transfected for 48 h with scrambled or Gα13 siRNA and then transfected again for an additional 72 h and kept in the presence or absence of 50 nm of aldosterone or 100 ng/ml of IGF-I. C, representative photomicrographs of cultures immunostained with anti-elastin antibody confirm the results presented in B. D, cultures transfected for 72 h with scrambled siRNA control and Gα13 siRNA oligonucleotides were treated for 10 min with or without 50 nm of aldosterone or 100 ng/ml of IGF-I. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an IGF-IR antibody and probed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody or anti-IGF-IR antibody. E, results of a one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing collagen type I and GAPDH mRNA transcript levels of cultures transfected for 72 h with scrambled siRNA control and Gα13 siRNA-specific oligonucleotides and treated for the last 24 h with or without 50 nm of aldosterone. F, representative photomicrographs of cultures immunostained with anti-collagen antibody that were initially transfected for 48 h with scrambled or Gα13 siRNA and then transfected again for an additional 72 h and kept in the presence or absence of 50 nm of aldosterone. ctr, control.

Aldosterone Also Induces a Transient Interaction between Gα13 and c-Src That Leads to c-Src Phosphorylation

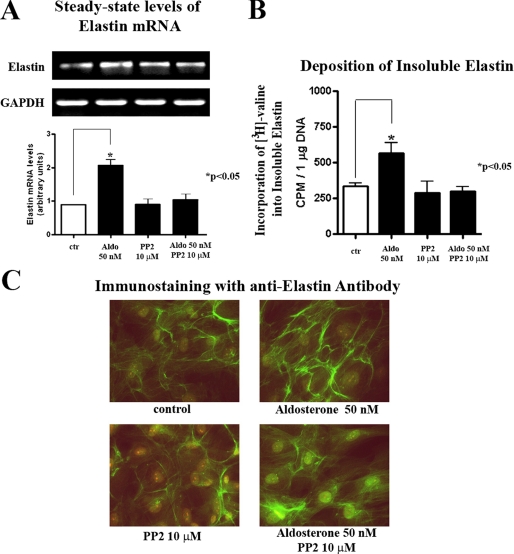

Results from further experiments suggested that this initial Gα13-dependent effect may also involve the activation of cytosolic tyrosine kinase c-Src. This conclusion was based on the observation that pharmacological inhibition of c-Src (with PP2) abolished an increase in elastin mRNA levels and the consequent up-regulation in elastic fiber production in aldosterone-treated cultures (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

c-Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 eliminates aldosterone-induced increases in elastin production in human cardiac fibroblast cultures. A, results of a one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing elastin and GAPDH mRNA transcripts in cultures maintained for 24 h in the presence or absence of 50 nm aldosterone, with or without 1 h pretreatment with 10 μm of PP2. B, levels of [3H]valine-labeled insoluble elastin in cultures 1 h pretreated with PP2 following 72 h of incubation with 50 nm of aldosterone. C, representative photomicrographs of confluent cultures immunostained with anti-elastin antibody confirm the results presented in B. ctr, control.

Because the most characterized downstream signaling mediated by Gα13 involves GTPase Rho (28, 47), we examined the possible involvement of Rho and its downstream effector, Rho-associated kinase, in aldosterone-dependent elastogenesis. Because pretreatment of cultured cardiac fibroblasts, either with a cell membrane-permeable Rho inhibitor, CT04, or with a specific Rho-associated kinase inhibitor, Y-27632, did not eliminate the aldosterone-induced increase in elastin mRNA expression and elastin production in our cardiac fibroblast cultures, we concluded that the Rho pathway is not involved in the described elastogenic effect of aldosterone (data not shown).

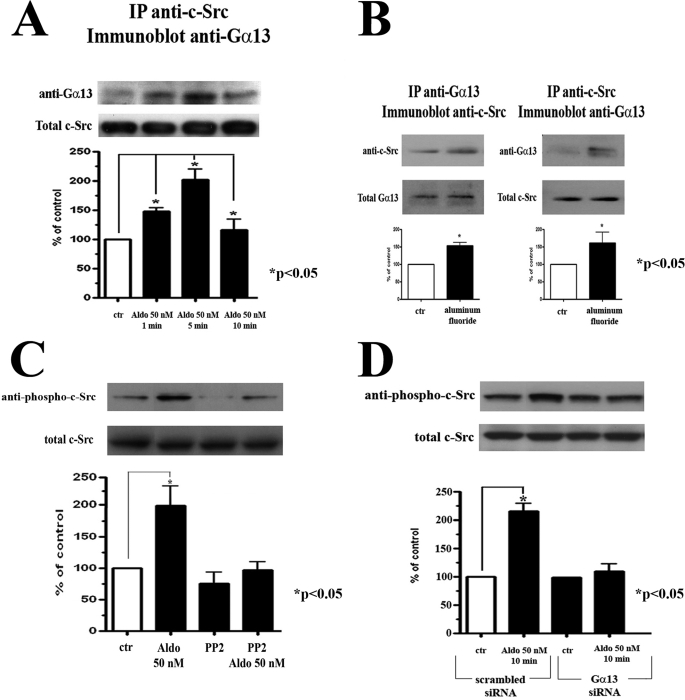

Instead, we have established that Gα13 transiently interacts with c-Src proteins following aldosterone treatment. This conclusion was based on results of experiments indicating that Gα13 and c-Src can be co-immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates that were maintained in the presence and absence of aldosterone for 1, 5, or 10 min. Interaction between these two proteins was most evident after 5 min of aldosterone exposure (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Aldosterone treatment increases the interaction between Gα13 and c-Src, leading to activation of c-Src in human cardiac fibroblast cultures. A, cellular lysates of cardiac fibroblast cultures treated with or without 50 nm of aldosterone for 1, 5, and 10 min were immunoprecipitated with anti c-Src antibody and probed with an anti-Gα13 antibody or anti-c-Src antibody. B, cellular lysates obtained from cultures treated with or without aluminum fluoride for 30 min were immunoprecipitated with anti-Gα13 antibody (left panel) or anti-c-Src antibody (right panel) and probed with an anti-c-Src antibody or anti-Gα13 antibody, respectively. C and D, Western blot analysis of cellular lysates obtained from cultures treated with or without 50 nm of aldosterone for 10 min (C) after they were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of 10 μm of PP2 or (D) following 72 h of transfection with scrambled siRNA control and Gα13 siRNA oligonucleotides and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-c-Src (Tyr416) and then reprobed with anti-c-Src antibody. ctr, control.

We then investigated whether pharmacological activation of Gα13 enforces its transient association with c-Src. We found that a nonspecific activator of Gα proteins, aluminum fluoride (48, 49), also increased the interaction between c-Src and Gα13 (Fig. 6B). Specifically, we found that c-Src imunoprecipitated from cellular lysates treated with aluminum fluoride consistently displayed greater interaction with Gα13 than untreated controls (Fig. 6B).

Because phosphorylation of c-Src at Tyr416 in the activation loop of the kinase domain up-regulates the enzymatic activity of c-Src (50), we then examined whether aldosterone treatment would increase c-Src phosphorylation at Tyr416. Indeed, Western blotting with a specific anti-phospho-c-Src (Tyr416) antibody indicated that lysates of cells treated with aldosterone displayed increased phosphorylation of c-Src on Tyr416, as compared with the control. We also demonstrated that PP2 pretreatment abolished this effect (Fig. 6C). Importantly, we also found that the Gα13 siRNA-transfected cultures did not demonstrate any increase in c-Src phosphorylation in response to aldosterone treatment. This was in contrast to scrambled siRNA-transfected cultures, which demonstrated a significant increase in c-Src phosphorylation after treatment with aldosterone (Fig. 6D). These results thus further enforced the notion that in cardiac fibroblasts aldosterone engages Gα13 signaling that in turn interacts with c-Src, causing its activation.

PI 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling Pathway Propagates the Elastogenic Signal upon IGF-IR Activation

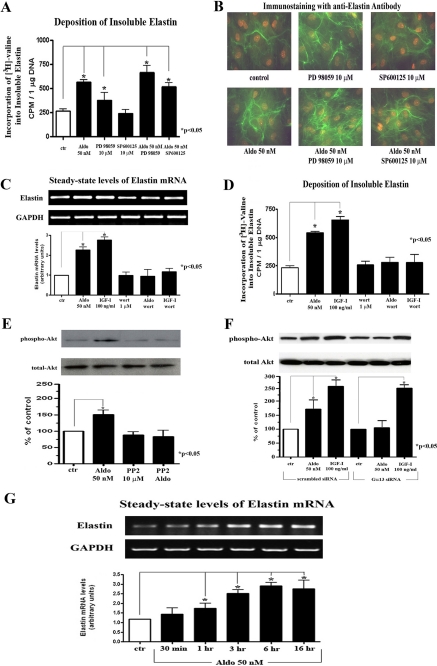

Having established that the IGF-IR receptor mediates the effect of aldosterone on elastin production, we now attempted to determine which downstream IGF-IR signaling pathway, the PI 3-kinase/Akt or the MAPK/ERK pathway (51), propagates the elastogenic signal. Results from metabolic labeling studies and immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated that blocking the activation of the MAPK pathway by its specific MEK inhibitor, PD 98059, did not eliminate the elastogenic effect of aldosterone but instead led to a further increase in the production of elastin (Fig. 7, A and B). Also, treatment with an inhibitor (SP600125) that inactivated another MAPK family member, JNK, did not diminish the elastogenic effect of aldosterone (Fig. 7, A and B). On the other hand, results from one-step RT-PCR analysis and metabolic labeling studies demonstrated that the addition of the PI 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin to cultures treated with aldosterone or IGF-I abolished the elastogenic effects of both stimulators (Fig. 7, C and D). These results indicate that the IGF-IR-PI 3-kinase pathway propagates the elastogenic signal and that inhibition of the parallel MAPK pathway further enhances the net elastogenic effect.

FIGURE 7.

Aldosterone- or IGF-I-induced increases in elastin production in human cardiac fibroblast cultures is propagated via the PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. A and B, results of a quantitative assay of [3H]valine-labeled insoluble elastin (A) and immunohistochemistry with anti-elastin antibody of cultures pretreated for an hour with or without 10 μm of PD 98059 or SP600125 prior to 72 h treatment with 50 nm of aldosterone (B). C, results of a one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing elastin and GAPDH mRNA transcripts in cultures maintained for 24 h in the presence or absence of 50 nm aldosterone or 100 ng/ml of IGF-I, prior to 1 h pretreatment with 1 μm of wortmannin. D, results of a quantitative assay of [3H]valine-labeled insoluble elastin of cultures treated for 72 h with 50 nm of aldosterone or with 100 ng/ml of IGF-I prior to 1 h pretreatment with 1 μm of wortmannin. E and F, Western blot analysis of cellular lysates obtained from cultures treated for 10 min with or without 50 nm of aldosterone after they were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of 10 μm of PP2 (E) or treated for 10 min with aldosterone or 100 ng/ml of IGF-I following 72 h of transfection with scrambled siRNA control and Gα13 siRNA-specific oligonucleotides (F) and immunoblotted using anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) antibody and then stripped and reprobed with anti-Akt antibody. G, one-step RT-PCR analysis assessing elastin and GAPDH mRNA transcripts in cultures treated for 30 min or 1, 3, 6, or 16 h with or without 50 nm of aldosterone. ctr, control.

To finally link the early steps of aldosterone-induced signaling (Gα13-dependent c-Src activation) with the downstream elastogenic pathway (PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling transduced through the IGF-IR following its activation), we tested whether this IGF-IR-dependent downstream signaling event would still occur after inhibition of c-Src with PP2 and in cultures lacking Gα13. Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-Akt antibody revealed that the aldosterone-induced increase in the phosphorylation of Akt is indeed eliminated in cultures treated with the c-Src inhibitor PP2 and in cultures transfected with Gα13 siRNA (Fig. 7, E and F). Furthermore we showed that the levels of tropoelastin mRNA began to significantly increase as early as 1 h after exposure to aldosterone, reached a maximum level between 3–6 h, and remained elevated throughout the course of the experiment (Fig. 7G). This endorsed the suggested link between the early aldosterone induced signaling and consequent increase in elastin mRNA steady-state levels. Thus, the data presented reveal the details of an elastogenic signaling pathway that is triggered by aldosterone and involves the consecutive activation of Gα13, c-Src, and IGF-IR and its downstream PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that aldosterone stimulates elastogenesis via IGF-IR signaling in both fetal and adult and cultures of human cardiac fibroblasts, even in the presence of the MR-antagonist spironolactone (18). Results of the experiments presented in this report additionally demonstrate that aldosterone still induces elastogenesis in cardiac fibroblast cultures in which the synthesis of MR protein is inhibited by the use of MR-specific siRNA oligonucleotides. Thus, these data further confirm that the elastogenic effect of aldosterone is executed via an MR-independent mechanism. Moreover, we have established that membrane-impermeable, BSA-conjugated aldosterone produces the same magnitude of IGF-IR phosphorylation as equimolar concentrations of free aldosterone (Fig. 1). This suggests that the signaling pathway leading to the MR-independent elastogenic effect of aldosterone may be initiated after the interaction of this steroid hormone with a certain moiety residing on the cell surface of cardiac fibroblasts. This assumption is further supported by other studies that have demonstrated the existence of high affinity membrane-binding sites for aldosterone in human vascular endothelium (52) human mononuclear leukocytes (53) and in pig kidneys (10) and livers (54). It has also been suggested that a 50-kDa protein may meet the criteria for the alternative cell surface receptor for aldosterone (53). However, this putative aldosterone receptor that mediates MR-independent action has not been characterized yet.

Because previous reports have suggested that G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are involved in the propagation of certain steroid receptor-independent effects of other steroid hormones in animals (55, 56) and humans (57–60) and that some MR-independent effects of aldosterone can also be mediated through pertussis toxin-sensitive Gαi proteins (13, 17), we first investigated whether Gαi would propagate the elastogenic effect of aldosterone. However, the results of our experiments, as depicted in Fig. 2, excluded the possibility that activation of Gαi may be involved in aldosterone-induced elastogenesis. Instead, we demonstrated for the first time that another heterotrimeric Gα protein, a member of the G12 subfamily, Gα13, participates in a cellular response to aldosterone that involves IGF-IR activation and a consequent enhancement of elastogenesis. This conclusion was based on data indicating that the elimination of Gα13 in cultured cardiac fibroblasts by MR-specific siRNA oligonucleotides completely attenuated the aldosterone-induced increase in IGF-IR phosphorylation and subsequent elastin production (Figs. 3 and 4). At the same time we also demonstrated that the absence of the Gα13 protein did not eliminate the elastogenic response of IGF-I (Fig. 4). This also reinforced our belief that Gα13 is located upstream of the IGF-IR in the elastogenic signaling pathway triggered by aldosterone.

Although previous studies have also shown that Gα13 can stimulate the activation of the cytosolic tyrosine kinase c-Src in various cell types, including cardiac fibroblast cultures (28, 47, 61–65), the results of our co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that treatment with aldosterone enhances the transient interaction between Gα13 and c-Src (Fig. 6). Because the inactivation of c-Src (by its specific PP2 inhibitor) eliminated the elastogenic effect of aldosterone, we concluded that the action of this kinase constitutes a prerequisite for the propagation of the aldosterone-dependent elastogenic signal (Figs. 5 and 6).

It has been previously shown that Gα13 can directly bind and activate various proteins (66), including cytosolic tyrosine kinases such as Pyk2 (67). Currently, we do not know whether the aldosterone-triggered interaction between Gα13 and c-Src is direct or whether it requires other proteins, such as Pyk2, that might bind and facilitate phosphorylation of c-Src (68, 69). We have established, however, that in aldosterone-treated cardiac fibroblasts, Gα13 stimulates phosphorylation of c-Src, via the Rho-independent pathway and that the consecutive steps of elastogenic signaling involve increased phosphorylation of the IGF-IR and its downstream PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway (Fig. 7).

It has been previously shown as well that c-Src may not only phosphorylate the IGF-IR on ligand-induced auto-phosphorylation sites but also significantly increase the phosphorylation of this receptor on Tyr1316 (70), which has been implicated as a potential PI 3-kinase-binding site (71, 72). We may therefore speculate that aldosterone-induced Gα13/c-Src activation facilitates IGF-IR signaling by enhancing its Tyr1316 phosphorylation. This in turn selectively promotes the downstream PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway needed for elastogenesis but not the alternative IGF-IR-propagated mitogenic MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Our speculation seems to be additionally endorsed by data indicating that the aldosterone-induced elastogenic effect was enhanced in the presence of the MEK inhibitor PD 98059. Also, treatment with an inhibitor (SP600125) inactivating JNK, another MAPK family member, did not diminish the elastogenic effect of aldosterone (Fig. 7, A and B).

Because phosphorylation on Tyr1316 of the insulin receptor, which is closely related to the IGF-IR, has been shown to play an inhibitory role in mitogenic signaling (73), we also speculate that the aldosterone-induced signaling enhancing phosphorylation of Tyr1316 on the IGF-IR may contribute to the mechanism maintaining the balance between signals stimulating differentiation and mitogenesis. Further studies are needed to confirm this concept.

In this study we did not investigate further the already well disclosed elastogenic mechanism in which IGF-I induces an increase in elastin gene expression. It has been previously documented that in aortic smooth muscle cells (74–76) IGF-I induces an increase in elastin gene expression via a derepressive mechanism involving the abrogation of Sp3, a retinoblastoma protein (Rb)-associated element, that allows for activation of the elastin promoter by Rb on its retinoblastoma control element (75, 76). Because Rb lies downstream of the PI 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway (77), we may speculate that the aldosterone-dependent activation of this signaling pathway also modulates the interaction between Rb and pro-elastogenic transcription factors (74–76), leading to an increase in elastin gene expression in cardiac fibroblasts. Because we found that inhibition of the promitogenic MAPK/ERK signaling pathway further enhanced the effect of aldosterone on elastin production (Fig. 7, A and B), we may also suggest that the PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway induces elastogenesis by altering the phosphorylation state of Rb, whereas the mitogenic MAPK/ERK pathway antagonizes this effect. Interestingly, a similar pro-elastogenic effect involving the PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway has been reported in lung fibroblasts after exposure to transforming growth factor-β (78).

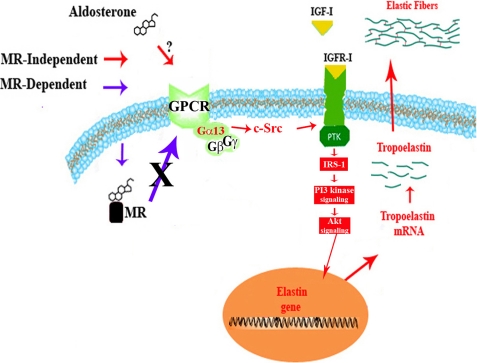

In summary, the data presented in this study suggest that the elastogenic effect of aldosterone in cardiac fibroblasts is propagated through the MR-independent action of this hormone. This novel mechanism likely involves a still unidentified GPCR (or GPCRs) that couples to Gα13 to stimulate c-Src, which in turn facilitates the activation of tyrosine kinase-dependent phosphorylation of the IGF-IR and its downstream PI 3-kinase signaling pathway (Fig. 8). This signaling pathway ultimately leads to the up-regulation of the elastin gene and the efficient production of elastic fibers by cardiac fibroblasts. We speculate that the heightened production of elastic fibers that results from the MR-independent action of aldosterone may counterbalance MR-mediated maladaptive fibrosis in the post-infarct heart in patients using MR antagonists, thus providing resilience to the cardiac stroma and facilitating normal ventricular function.

FIGURE 8.

Proposed mechanism by which aldosterone increases elastin production in cardiac fibroblast cultures. Aldosterone interacts with a still unidentified GPCR that causes the activation of Gα13. Activated Gα13, in turn, interacts with cytosolic c-Src. This interaction facilitates the activation of IGF-IR-IRS/PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling, which occurs even in the presence of sub-physiological levels of IGF-I, and subsequently induces increased elastin transcription and production. This effect of aldosterone is not dependent on the presence of the MR.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research through Grant PG 13920, by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario through Grants NA 5435 and NA 4381, and by Career Investigator Award CI 4198 (to A. H.).

- MR

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- IGF-I

- insulin-like growth factor-I

- IGF-IR

- IGF-I receptor

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- Rb

- retinoblastoma protein

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- RT

- reverse transcription

- MEK

- MAPK/ERK kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jennings D. L., Kalus J. S., O'Dell K. M. ( 2005) Pharmacotherapy 25, 1126– 1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connell J. M., Davies E. ( 2005) J. Endocrinol. 186, 1– 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber K. T., Brilla C. G. ( 1991) Circulation 83, 1849– 1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brilla C. G., Matsubara L. S., Weber K. T. ( 1993) Am. J. Cardiol. 71, 12A– 16A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young M., Fullerton M., Dilley R., Funder J. ( 1994) J. Clin. Investig. 93, 2578– 2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt B., Zannad F., Remme W. J., Cody R., Castaigne A., Perez A., Palensky J., Wittes J. ( 1999) N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 709– 717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitt B., Remme W., Zannad F., Neaton J., Martinez F., Roniker B., Bittman R., Hurley S., Kleiman J., Gatlin M. ( 2003) N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1309– 1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zannad F., Alla F., Dousset B., Perez A., Pitt B. ( 2000) Circulation 102, 2700– 2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zannad F., Dousset B., Alla F. ( 2001) Hypertension 38, 1227– 1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christ M., Sippel K., Eisen C., Wehling M. ( 1994) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 99, R31– 34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haseroth K., Gerdes D., Berger S., Feuring M., Günther A., Herbst C., Christ M., Wehling M. ( 1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266, 257– 261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai W., Garrelds I. M., de Vries R., Batenburg W. W., van Kats J. P., Danser A. H. ( 2005) Hypertension 46, 701– 706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gekle M., Silbernagl S., Wünsch S. ( 1998) J. Physiol. 511, 255– 263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mihailidou A. S. ( 2006) Steroids 71, 277– 280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Böhmer S., Carapito C., Wilzewski B., Leize E., Van Dorsselaer A., Bernhardt R. ( 2006) Biol. Chem. 387, 917– 929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisen C., Meyer C., Christ M., Theisen K., Wehling M. ( 1994) Cell. Mol. Biol. 40, 351– 358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urbach V., Harvey B. J. ( 2001) J. Physiol. 537, 267– 275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunda S., Liu P., Wang Y., Liu K., Hinek A. ( 2007) Am. J. Pathol. 171, 809– 819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlanger B. F., Borek F., Beiser S. M., Lieberman S. ( 1957) J. Biol. Chem. 228, 713– 727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coles J. G., Boscarino C., Takahashi M., Grant D., Chang A., Ritter J., Dai X., Du C., Musso G., Yamabi H., Goncalves J., Kumar A. S., Woodgett J., Lu H., Hannigan G. ( 2005) J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 129, 1128– 1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafsson A. B., Brunton L. L. ( 2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 1470– 1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou G., Kandala J. C., Tyagi S. C., Katwa L. C., Weber K. T. ( 1996) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 154, 171– 178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Moëllic C., Ouvrard-Pascaud A., Capurro C., Cluzeaud F., Fay M., Jaisser F., Farman N., Blot-Chabaud M. ( 2004) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15, 1145– 1160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arima S. ( 2006) Steroids 71, 281– 285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alessi D. R., Cuenda A., Cohen P., Dudley D. T., Saltiel A. R. ( 1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27489– 27494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagai Y., Miyata K., Sun G. P., Rahman M., Kimura S., Miyatake A., Kiyomoto H., Kohno M., Abe Y., Yoshizumi M., Nishiyama A. ( 2005) Hypertension 46, 1039– 1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett B. L., Sasaki D. T., Murray B. W., O'Leary E. C., Sakata S. T., Xu W., Leisten J. C., Motiwala A., Pierce S., Satoh Y., Bhagwat S. S., Manning A. M., Anderson D. W. ( 2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 13681– 13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishida M., Onohara N., Sato Y., Suda R., Ogushi M., Tanabe S., Inoue R., Mori Y., Kurose H. ( 2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23117– 23128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura I., Takahashi N., Sasaki T., Tanaka S., Udagawa N., Murakami H., Kimura K., Kabuyama Y., Kurokawa T., Suda T., Fukui Y. ( 1995) FEBS Lett. 361, 79– 84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yano H., Nakanishi S., Kimura K., Hanai N., Saitoh Y., Fukui Y., Nonomura Y., Matsuda Y. ( 1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25846– 25856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karni R., Mizrachi S., Reiss-Sklan E., Gazit A., Livnah O., Levitzki A. ( 2003) FEBS Lett. 537, 47– 52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uehata M., Ishizaki T., Satoh H., Ono T., Kawahara T., Morishita T., Tamakawa H., Yamagami K., Inui J., Maekawa M., Narumiya S. ( 1997) Nature 389, 990– 994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yanazume T., Hasegawa K., Wada H., Morimoto T., Abe M., Kawamura T., Sasayama S. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8618– 8625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji H., Leung M., Zhang Y., Catt K. J., Sandberg K. ( 1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 16533– 16536 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hafizi S., Wharton J., Morgan K., Allen S. P., Chester A. H., Catravas J. D., Polak J. M., Yacoub M. H. ( 1998) Circulation 98, 2553– 2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Widdop R. E., Gardiner S. M., Kemp P. A., Bennett T. ( 1993) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 265, H226– 231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang X. Y., Gao G. D., Du X. J., Zhou J., Wang X. F., Lin Y. X. ( 2007) Acta Cardiol. 62, 429– 438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi Y., Katoh H., Negishi M. ( 2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14936– 14939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinek A., Rabinovitch M. ( 1994) J. Cell Biol. 126, 563– 574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinek A., Rabinovitch M. ( 1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1405– 1413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodems S. M., Spector D. H. ( 1998) J. Virol. 72, 9173– 9180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinek A., Rabinovitch M., Keeley F., Okamura-Oho Y., Callahan J. ( 1993) J. Clin. Investig. 91, 1198– 1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krumins A. M., Gilman A. G. ( 2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10250– 10262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazak I., Fiebeler A., Muller D. N., Park J. K., Shagdarsuren E., Lindschau C., Dechend R., Viedt C., Pilz B., Haller H., Luft F. C. ( 2004) Circulation 109, 2792– 2800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao F., Puddefoot J. R., Barker S., Vinson G. P. ( 2004) Hypertension 44, 340– 345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simoncini T., Scorticati C., Mannella P., Fadiel A., Giretti M. S., Fu X. D., Baldacci C., Garibaldi S., Caruso A., Fornari L., Naftolin F., Genazzani A. R. ( 2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1756– 1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S., Jin J., Kunapuli S. P. ( 2006) Blood 107, 947– 954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hart M. J., Jiang X., Kozasa T., Roscoe W., Singer W. D., Gilman A. G., Sternweis P. C., Bollag G. ( 1998) Science 280, 2112– 2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L. ( 2003) Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 14, 100– 114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roskoski R., Jr. ( 2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 1– 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeRoith D., Werner H., Beitner-Johnson D., Roberts C. T., Jr. ( 1995) Endocr. Rev. 16, 143– 163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wildling L., Hinterdorfer P., Kusche-Vihrog K., Treffner Y., Oberleithner H. ( 2009) Pflugers Arch., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wehling M., Eisen C., Christ M. ( 1992) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 90, 5– 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer C., Christ M., Wehling M. ( 1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 229, 736– 740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Losel R. M., Wehling M. ( 2008) Front. Neuroendocrinol. 29, 258– 267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu Y., Rice C. D., Pang Y., Pace M., Thomas P. ( 2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 2231– 2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Filardo E. J., Quinn J. A., Bland K. I., Frackelton A. R., Jr. ( 2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1649– 1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Filardo E. J., Quinn J. A., Frackelton A. R., Jr., Bland K. I. ( 2002) Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 70– 84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Filardo E. J., Quinn J. A., Sabo E. ( 2008) Steroids 73, 870– 873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Y., Bond J., Thomas P. ( 2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 2237– 2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adarichev V. A., Vaiskunaite R., Niu J., Balyasnikova I. V., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. A. ( 2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 285, C922– 934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim M., Nozu F., Kusama K., Imawari M. ( 2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 339, 271– 276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minuz P., Fumagalli L., Gaino S., Tommasoli R. M., Degan M., Cavallini C., Lecchi A., Cattaneo M., Lechi Santonastaso C., Berton G. ( 2006) Biochem. J. 400, 127– 134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dib K., Melander F., Andersson T. ( 2001) J. Immunol. 166, 6311– 6322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klages B., Brandt U., Simon M. I., Schultz G., Offermanns S. ( 1999) J. Cell Biol. 144, 745– 754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kurose H. ( 2003) Life Sci 74, 155– 161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi C. S., Sinnarajah S., Cho H., Kozasa T., Kehrl J. H. ( 2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24470– 24476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dikic I., Tokiwa G., Lev S., Courtneidge S. A., Schlessinger J. ( 1996) Nature 383, 547– 550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J., Avraham H., Rogers R. A., Raja S., Avraham S. ( 1996) Blood 88, 417– 428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peterson J. E., Kulik G., Jelinek T., Reuter C. W., Shannon J. A., Weber M. J. ( 1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31562– 31571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu D., Zong C. S., Wang L. H. ( 1993) J. Virol. 67, 6835– 6840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jiang Y., Chan J. L., Zong C. S., Wang L. H. ( 1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 160– 167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ando A., Momomura K., Tobe K., Yamamoto-Honda R., Sakura H., Tamori Y., Kaburagi Y., Koshio O., Akanuma Y., Yazaki Y. ( 1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 12788– 12796 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolfe B. L., Rich C. B., Goud H. D., Terpstra A. J., Bashir M., Rosenbloom J., Sonenshein G. E., Foster J. A. ( 1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 12418– 12426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jensen D. E., Rich C. B., Terpstra A. J., Farmer S. R., Foster J. A. ( 1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6555– 6563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Conn K. J., Rich C. B., Jensen D. E., Fontanilla M. R., Bashir M. M., Rosenbloom J., Foster J. A. ( 1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28853– 28860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mita M. M., Mita A., Rowinsky E. K. ( 2003) Cancer Biol. Ther. 2, 169– 177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kuang P. P., Zhang X. H., Rich C. B., Foster J. A., Subramanian M., Goldstein R. H. ( 2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292, L944– 952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]