Abstract

The molecular basis of microtubule lattice instability derives from the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP in the lattice-bound state of αβ-tubulin. While this has been appreciated for many years, there is ongoing debate over the molecular basis of this instability and the possible role of altered nucleotide occupancy in the induction of a conformational change in tubulin. The debate has organized around seemingly contradictory models. The allosteric model invokes nucleotide-dependent states of curvature in the free tubulin dimer, such that hydrolysis leads to pronounced bending and thus disruption of the lattice. The more recent lattice model describes a predominant role for the lattice in straightening free dimers that are curved regardless of their nucleotide state. In this model, lattice-bound GTP-tubulin provides the necessary force to straighten an incoming dimer. Interestingly, there is evidence for both models. The enduring nature of this debate stems from a lack of high-resolution data on the free dimer. In this study, we have prepared αβ-tubulin samples at high dilution and characterized the nature of nucleotide-induced conformational stability using bottom-up hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (H/DX-MS) coupled with isothermal urea denaturation experiments. These experiments were accompanied by molecular dynamics simulations of the free dimer. We demonstrate an intermediate state unique to GDP-tubulin, suggestive of the curved colchicine-stabilized structure at the intradimer interface but show that intradimer flexibility is an important property of the free dimer regardless of nucleotide occupancy. Our results indicate that the assembly properties of the free dimer may be better described on the basis of this flexibility. A blended model of assembly emerges in which free-dimer allosteric effects retain importance, in an assembly process dominated by lattice-induced effects.

Tubulin is a central component of the cytoskeleton, with significant roles in cell division, intracellular transport, and maintenance of cell polarity. An important property of this structural protein involves its well-regulated capacity to polymerize into a cylindrical polymeric state, the microtubule (1). Tubulin is a heterodimer composed of structurally homologous α and β subunits, both of which bind GTP1 in analogous locations. In α-tubulin, the nucleotide is bound at a nonexchangeable site (N-site) and together with chelation of Mg2+ is important in maintaining the stability of the dimer (2, 3). Fundamental to the properties of the assembled state is GTP hydrolysis at the exchangeable site (E-site) in β-tubulin, initiated only following assembly into the microtubule (1). Hydrolysis occurs at the E-site in an assembled dimer, under the action of Glu-254 in the H8 helix of α-tubulin on an incoming dimer in a head-to-tail arrangement (4). Release of Pi imparts a lattice instability within the polymer and provides the basis for microtubule dynamic instability, which is its hallmark. Thus, tubulin primed with GTP at the E-site (GTP-tubulin for brevity) constitutes the assembly unit whereas tubulin primed with GDP at the E-site (GDP-tubulin) induces instability within the microtubule and is generated after a slight kinetic lag (5).

The mechanism of nucleotide priming of instability has been the subject of considerable interest. The most straightforward model proposes that free GTP-tubulin exists in a straight polymerization-competent orientation whereas free GDP-tubulin possesses a noticeable polymerization-inhibiting kink at the intradimer interface, between α and β subunits (6, 7). This model is used to reconcile structural studies that establish GDP-tubulin in a curved protofilament structure using stabilizers for the curved form (8). The model assumes that the straight structure, described in a seminal structural study by Nogales, represents the GTP-tubulin (9). This assumption receives support from the presence of sheet-like structures at microtubule growing ends that would require a “nearly straight” organization (10) and more recently by structures of polymerized αβ-tubulin with the nonhydrolyzable GTP analogue guanosine 5′-[(α,β)-methylene]-triphosphate at the E-site (GMPCPP-tubulin) (6). This model has recently been referred to as the allosteric model, in which nucleotide binding influences the intradimer bend angle, 40Å distant from the E-site (11).

Conversely, the lattice model recognizes that αβ-tubulin dimers exist in the bent form regardless of nucleotide state, which is also true of the distantly related bacterial homologues (12) and most recently γ-tubulin in GTP form (11). In this model, there is no transition inducible by nucleotide occupancy; the straightening of the dimer is the result of assembly since lattice-bound GTP-tubulin reduces the energy barrier to this conformational change by providing stronger lattice contacts for an incoming dimer. Some evidence for the equivalency of GDP-tubulin and GTP-tubulin conformations has been presented in a SAXS study conducted on both, where it was concluded that the two nucleotide forms are equivalent structurally, and by inference favoring the bent form of γ-tubulin (11).

The difficulty in establishing an accurate atomistic model stems from the challenges inherent in generating structures from a dynamic, polymerizing protein at sufficiently high resolution. Aside from the SAXS studies, all existing structural evidence for the free dimer is derived from various states of assembly assumed to reflect the unassembled dimer (e.g., the colchicine/ RB3-stabilized double dimer) (8). Hydrogen/deuterium exchange (H/DX) processes provide a very sensitive probe of hydrogen-bonding networks based on backbone amide hydrogens, reflective of the protein conformational ensemble (13, 14). When studying protein–ligand interactions, perturbations of these networks can often be rationalized in terms of interfacial and allosteric properties of the interaction (15, 16), provided that care is taken to avoid altering the population of free protein and the underlying exchange mechanism (17). A bottom-up application of the technique monitors deuteration levels by mass spectrometry (MS) of pepsin-generated fragments to support higher resolution (18). This presents an opportunity for interrogating free αβ-tubulin in an effort to establish the nature of nucleotide-induced conformational instability. Bottom-up H/DX-MS has recently been applied to drug-stabilized microtubules in order to establish the basis for taxol-induced stabilization and to characterize new binding sites (19, 20).

The current study was undertaken to test whether the allosteric or lattice model is best supported, using dilute free tubulin dimer otherwise under assembly conditions. The high sensitivity of MS supports tubulin monitoring at concentrations sufficiently low to ensure the absence of polymerized or otherwise partially assembled states. Here we present a combination of differential HDX-MS and isothermal urea denaturation analysis; when combined, they demonstrate differences between free GTP and GDP-tubulin dimer. This work builds upon previous studies of urea-induced denaturation of tubulin, which established the existence of low-energy states for tubulin below 1.5 M urea under conditions approximating equilibrium (21, 22). Bottom-up H/DX-MS analysis allows for a higher resolution probe of these states, without requiring functional assays involving assembly, hydrolysis, or drug binding. In this manner, the impact of nucleotide exchange can be monitored in a solution environment free of possible structure-inducing stimuli, as may be the case in the existing structural models of tubulin. Combined with results from molecular dynamics simulations, we propose a revised model of tubulin assembly, in which both nucleotide-induced conformational changes and lattice effects establish the properties of assembled tubulin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Preparation

For studies of the free dimer, bovine brain tubulin stock solutions were prepared fresh each day to 50 μM from the same lot of lyophilized tubulin (Cytoskeleton Inc., catalog no. TL238-A, lot no. 753) reconstituted in 1 mM nucleotide-containing, assembly-competent buffer and held on ice until point of use. Buffer consisted of 100 mM KCl, 10 mM K-PIPES, and 1 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9. Upon reconstitution the stock solution also contained 2.5% w/v sucrose and 0.5% w/v Ficoll for protein stabilization. Tubulin stock solutions were then diluted in assembly buffer to concentrations below the critical point for assembly. To determine an acceptable concentration for the buffer composition used, serially diluted tubulin solutions were incubated for 30 min in 1 mM GMPCPP-containing assembly buffer at 37 °C. Aliquots were taken before and after centrifugation (14000g for 5 min) to determine the reduction in free tubulin dimer as a result of microtubule formation, where the polymerization event would be expected to reduce the tubulin concentration in the supernatant. For example, at a tubulin concentration of 3.4 μM we measured an absorbance of 0.48 ± 0.01 in a Bradford assay, equivalent to the preincubation sample absorbance (0.48 ± 0.01), indicating the absence of microtubules. For all H/DX-MS experiments, except where noted, tubulin was held to a concentration of 1.25 μM and an incubation temperature ≤20 °C, further diminishing the probability of self-assembly. At this dilution, the protein stabilizers are reduced to 0.06% w/v (2 mM) sucrose and 0.01% w/v Ficoll, well below concentrations expected to influence tubulin stability (23, 24). The absence of microtubule assembly for all nucleotide forms of tubulin was further confirmed under these conditions by H/DX-MS (data not shown), and the polymerization competence of the solution composition was confirmed at elevated tubulin concentration (60 μM) and 37 °C.

Sample Processing for H/DX-MS

Aliquots were diluted from stock as indicated and incubated in 1 mM nucleotide buffer for 30 min on ice. The sample was then warmed to 20 °C in 1 min, combined with D2O held at the same temperature, and labeling was allowed to proceed for 4 min (with final tubulin concentration of 1.25 μM and D2O concentration at 25% v/v). Previous studies confirmed that labeling was essentially complete by this time (19). The termination of labeling and the initiation of digestion were achieved by adding the labeled sample to a chilled slurry of immobilized pepsin (Applied Biosystems Inc.) in 0.1 M glycine hydrochloride (pH 2.3) and digested for 2.5 min on ice. Digestion was terminated by centrifugation of the immobilized pepsin, and an aliquot of the supernatant (containing ~6 pmol of digest) was injected into an LC-MS system for analysis. Analyses were performed in quadruplicate for each of three nucleotides tested (GTP, GDP, and GMPCPP) and included a nucleotide-free preparation containing only assembly buffer and residual nucleotide from the stock solution (≤5-fold the tubulin concentration).

An additional control consisting of polymerized GMPCPP-tubulin was prepared and processed. Briefly, lyophilized tubulin was reconstituted in nucleotide-free buffer (20 mM KCl, 10 mM K-PIPES, pH 6.9) to 20 mg/mL and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to initiate polymerization and hydrolysis of GTP present in storage buffer. The resulting microtubules were pelleted and washed with a small amount of assembly buffer (1 mM GMPCPP, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM K-PIPES, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9) and then depolymerized on ice to a concentration of >60 μM. Prior to conducting HDX-MS experiments, an aliquot of this solution was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to induce polymerization. The solution was brought to room temperature and labeled with D2O as above.

H/DX LC-MS System

The LC-MS system consisted of an injection valve, a column loading pump, a prototype splitless low-flow gradient pump (Upchurch Scientific Inc.), and a QStar Pulsar i mass spectrometer (AB/Sciex Inc.) fitted with a turbo ion spray source. Chilled digest was injected onto a 150 μm i.d. × 65 mm C18 column prepared in-house. The valve, column, and fluid lines were housed in a chilled container (~0 °C) to minimize the back-exchange of deuterium label during analysis. A rapid gradient separation was performed, and the total time for analysis (from digestion to analysis) was 16 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive polarity and TOF-MS mode (m/z range from 300 to 1200).

Peptide Identification

The peptide map is essentially as described in a previous study (19), with the inclusion of 46 additional peptides for an improved sequence coverage of 94% (α-tubulin) and 93.9% ( β-tubulin). These additions were determined by recursive information-dependent acquisition LC-MS/MS runs, and the resulting data were searched against all SwissProt entries for bovine tubulin. Hits were manually validated via inspection of the raw MS/MS spectra. Several different tubulin isotypes were detected; however, no cases of isotype specific labeling were noted, as in previous work (19).

Data Analysis and Presentation

Average deuterium incorporation for all verified peptide sequences was determined using Hydra, a software package for interrogating large sets of LC-MS and LC-MS/MS data, following an alternative analysis procedure reported separately (25). Briefly, this involves the selection of a subset of peaks within a given peptide's isotopic distribution. When combined with reduced D2O concentration for labeling, this provides a sensitive means of detecting differential deuteration levels for large protein systems. Standard deviations in deuteration levels were determined from quadruplicate analyses on a per-peptide basis and on an aggregate basis, involving the combination of data from all peptides, as a surrogate for total protein. Data collection followed a randomized block strategy within each urea concentration to minimize the introduction of systematic error (26). This permitted conventional random error propagation calculations for determining precision on the aggregate measurements. Systematic error was further controlled via referencing measured values to GTP-tubulin runs of 0 M urea, and measurements were shown to be repeatable in day-over-day experiments. Although the lyophilization additives present in the stock solution appear to increase the stability of tubulin, as verified by time-course analysis using H/DX-MS, our randomization strategy ensured that any minor time dependency in sample quality would not interfere with data interpretation.

Differential labeling between two nucleotide states for a given peptide is reported as significant if it passed a two-tailed t test (p < 0.05) using pooled standard deviations, where pooling was deemed acceptable on the basis of per-peptide F-tests. Levels of altered deuteration were color coded per peptide on PDB entry 1JFF, except where noted. Tubulin structures were rendered in all figures using Pymol (http://pymol.sourceforge.net) except where noted.

Urea-Induced Equilibrium Denaturation Measurements of Free Dimer

Experiments were as above, with the addition of an aliquot of stock urea solution (8 M, prepared fresh) at the first dilution, prior to labeling with D2O. An incubation time of 30 min under dilute conditions was preserved, as was the dimer concentration (1.25 μM). Urea concentrations from 0 to 1 M were tested and the H/DX-MS analyses performed in quadruplicate for each of the three nucleotides. Nucleotide incorporation was measured with the chromatographic method described below, for each urea concentration tested.

Quantitation of Nucleotide Incorporation

Following a revised perchlorate method of Seckler and Timasheff (27), nucleotide incorporation under the conditions described was determined by first separating free nucleotide from tubulin-bound nucleotide using size exclusion chromatography (Zorbax GF-450, Agilent, 9.4 mm i.d., 250 mm length, flow rate 1 mL/min) with a buffer consisting of 0.2 M K2HPO4, 0.1 M acetic acid, and 0.1 mM MgCl2 (pH 7). Ice-cold HClO4 was added to the tubulin-containing fraction to a final concentration of 0.5 M to denature and precipitate the protein. After centrifugation, the supernatant was recovered and neutralized with a high concentration phosphate buffer (1 M K2HPO4, pH 7) and chilled to precipitate potassium perchlorate. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was filtered and injected on an ion-pair reverse-phase chromatography column for quantitation of nucleotide (Ascentis C18, Supleco, 4 mm i.d., 25 cm length, 1 mL/min). This used an isocratic buffer consisting of 4 mM tetrabutylammonium phosphate in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and detection at a wavelength of 254 nm. To quantitate fractional nucleotide content as a function of urea treatment, the area of each resolved nucleotide (GTP and GDP) was quantitated and referenced against guanosine peak area as an internal standard. These values were then referenced against the total nucleotide content in the absence of urea, assumed to represent full occupancy of both N- and E-sites (eq 1)

| (1) |

where Fi represents the nucleotide content at the ith urea concentration referenced against the concentration of nucleotide in the absence of urea. GXPi refers to the nucleotide peak area and Gi the guanosine peak area at the ith urea concentration. GXP0 refers to the nucleotide peak area and G0 the guanosine peak area in the absence of urea. This expression was also used to represent the fractional GDP occupancy at the E-site, using only the GDP peak areas. Calculating the fractional GTP occupancy at the E-site was done in a similar fashion, after subtracting the contribution of the N-site GTP to the GTP peak, which was assumed to be constant over the urea concentration range probed (0–1 M). The N-site contribution was measured using the chromatography data collected in the absence of urea (eq 2)

| (2) |

Error in the measurements of nucleotide content was determined from triplicate analyses at 0 and 0.25 M urea and the average error applied as an estimate over the urea concentration range.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Whole tubulin dimers for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were constructed from the 1JFF structure (4). Unresolved atoms in the 1JFF structure were either taken from the 1TUB structure (28), specifically for residues 35–60 of α-tubulin, or by adding residues in an extended conformation, as for both α- and β-tubulin N-terminal residues and the C-terminals tails. Three nucleotide states of the E-site of free tubulin (empty, GDP, and GTP3 Mg2+) were built from this modified 1JFF structure. As 1JFF is in the GDP-tubulin nucleotide state, the two additional states were created by deleting the nucleotide from the E-site or replacing it with a copy of the nucleotide from the N-site, respectively creating the empty and GTP3 Mg2+-tubulin states. Finally, ions and counterions consistent with 150 mM KCl were added using the PSFGEN module of VMD (29). An equilibrium configuration of ions was established by running 10 ns of in vacuo Langevin dynamics computer simulations using NAMD (30) with a dielectric constant of 80 and all tubulin atoms fixed. Following this, the system was solvated with preequilibrated TIP3P water molecules (31). Before production MD simulation in NAMD, the force fields CHARMM22 (32) (for proteins) and CHARMM27 (33) (for GTP/GDP) were applied, and all three systems were energy minimized and equilibrated. A total of 200 steps of conjugate gradient minimization were performed to eliminate steric clashes. The systems were then heated over a period of 1 ps to 310 K. This was followed by 6 ns of equilibration at constant temperature and constant pressure using the Berendsen weak-coupling method (34). Electrostatic interactions were calculated with particle mesh Ewald summation (35), and a 10Å cutoff was used for nonbonded interactions. Production molecular dynamics was then carried out for 20 ns. Only the last 10 ns of simulation data was used for analysis. Analysis of various properties, such as local and global root-mean-squared deviations (rmsd) of the structure from the mean, suggested that the conformation of tubulin in all three systems was stable for this period.

RESULTS

Nucleotide Incorporation

Based on previous protocols, nucleotide exchange was achieved by applying a concentration excess of the desired nucleotide. Incorporation was monitored using the chromatographic method adapted from Seckler and Timasheff (27) (see Materials and Methods), and a plot of the total recovered nucleotide (E-site plus N-site) as a function of urea treatment is shown in Figure 1A. Retention of nucleotide appears to decline above 0.25 M urea in GTP- and GDP-treated samples. During these analyses, it was noted that the area of the size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) peak for free tubulin dimer decreased with the application of ≥0.5 M urea, accompanied by the appearance and increase of an earlier eluting peak, presumably representing an aggregated state of tubulin. As a result, the reduction in nucleotide content may be due to dimer loss, removal of nucleotide from the E-site, or both. N-Site occupancy is safely assumed in the free dimer peak due to the high stability of the dimer (3). To determine the relative contributions of these two phenomena, the total recovered nucleotide was corrected for protein yield on the basis of the SEC peak areas for the free dimer, relative to the urea-free experiment. The corrected recoveries are shown in Figure 1B, indicating that loss of free dimer accounts for most of the reduction in nucleotide content as a result of urea treatment. Nucleotide occupancy in GTP-treated tubulin appears to be weakly dependent on urea, however. To explore this further, panels C and D of Figure 1 show the E-site nucleotide occupancy for GDP- and GTP-treated tubulin, respectively, as a function of urea concentration. In both cases, GDP occupancy of the E-site remains essentially constant, whereas the GTP occupancy declines at 0.5 M urea and beyond. It appears that urea treatment destabilizes elements of the E-site unique to the binding of the γ-phosphate, which is somewhat surprising given the slightly lower Kd value for GTP relative to GDP (36). However, the effect could arise from destabilizing E-site Mg2+; a reduction in E-site Mg2+ has been shown to dramatically reduce the affinity of GTP while affecting GDP binding hardly at all (37).

Figure 1.

(A) Effect of urea-induced destabilization on total nucleotide occupancy, summing contributions from both the N- and E-sites, arising from simple equilibration with excess nucleotide (specific nucleotide shown in the legend). Values are normalized against the yield achieved in the absence of urea under GDP-saturating conditions, according to eq 1. (B) Results as in (A), adjusted for a reduced recovery of free dimer upon urea treatment. (C, D) Fractional E-site occupancy as a function of urea for tubulin equilibrated with excess GDP (C) and GTP (D), assuming full retention of N-site nucleotide occupancy. Error bars represent ±1 SD (see text for details).

The total nucleotide content for GMPCPP-treated tubulin is not significantly different than a nucleotide-free preparation, with both demonstrating significantly lower nucleotide yield than either GDP- or GTP-treated forms (see Figure 1B). The reduced nucleotide recovery corresponds to a total apparent E-site occupation of only 60%. For GMPCPP-treated tubulin, only GDP and GTP were detected. These results appear inconsistent with those of Hyman et al., suggesting an E-site affinity only 4–8-fold lower than GTP (38). However, we note that this earlier study was conducted on the basis of a polymerization assay, in which the polymerized state is likely critical for high GMPCPP affinity. GMPCPP likely binds under our chosen conditions to the unoccupied E-site fraction but weakly and with a rapid off-rate, such that it dissociates from free tubulin during SEC analysis. The likelihood of this is supported by the assembly competence of the tubulin preparation and the stability of the resulting microtubules.

Overall, this analysis shows that H/DX-MS data derived from simple GDP and GTP treatment of tubulin will reflect a significant change in E-site occupation across the urea concentration range. However, attributing perturbations arising from nucleotide exchange may only safely be restricted to urea concentrations at and below 0.25 M. Beyond this concentration, E-site occupancy declines for GTP-tubulin, at least as determined by SEC analysis. As with GMPCPP-tubulin, this decline may reflect weaker overall binding of GTP relative to GDP, but nonetheless this argues for caution in the interpretation of perturbations detected at urea concentrations ≥0.5 M. Caution is similarly required for GMPCPP-treated tubulin over the entire range of urea concentration; thus we restrict our assessment of the H/DX-MS data for GMPCPP-treated tubulin to 0 M urea. In an effort to increase GMPCPP uptake in free tubulin, the protein was cycled through one round of assembly and depolymerization in the presence of this nucleotide. While this led to the appearance of increased occupancy as detected by the chromatographic method, H/DX-MS analysis revealed significant contamination from a partially assembled state as evidenced by reduced deuteration at key interdimer residues (data not shown). This is consistent with the observed resistance of the GMPCPP micro-tubule to disassembly by isothermal dilution (38).

The SEC-based separation of tubulin into two fractions at urea concentrations ≥0.5 M suggests the presence of an aggregated state even under these simple conditions, which could complicate an interpretation of the perturbation data based on a simple equilibrium denaturation model. However, the relative abundance of the higher mass fraction was observed to be concentration-dependent, disappearing at ~10 μM tubulin (5-fold lower than the tubulin concentration represented in the analyses of Figure1). The high-mass component did not exhibit a nucleotide dependency and may simply represent nonspecific aggregation of partially unfolded states at higher protein concentration. The absence of aggregation is supported by the H/DX-MS data where no reductions in deuteration were observed, vide infra.

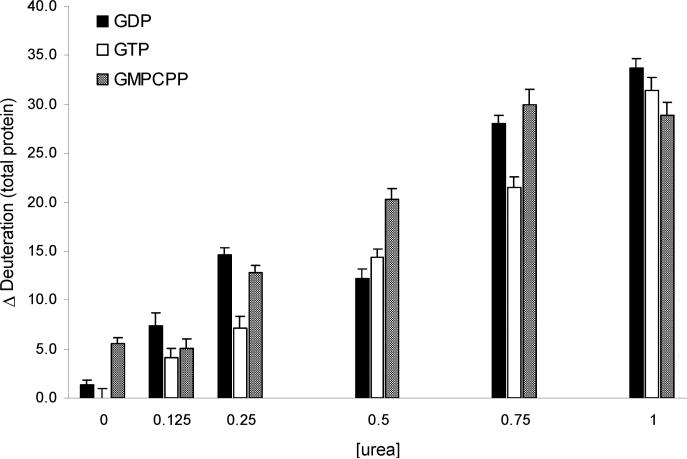

H/DX-MS Analysis of Urea-Induced Equilibrium De-stabilization

The dilute nucleotide-tubulin samples were then subjected to denaturant analysis with peptide-based H/DX-MS detection. To quantify denaturation at the protein level as a function of urea treatment, all peptide deuteration levels were summed. Using the deuteration levels of GTP-tubulin at 0 M urea as a baseline, the differential deuteration levels of all three nucleotide-tubulins are shown in Figure 2. This method is preferred over the more common measure from the intact protein, as peak width and asymmetry for large intact proteins generate measurements with lower precision. Note that differential deuteration levels calculated in this fashion do not reflect the true difference, as overlapping and redundant peptides were used. However, relative deuteration levels between nucleotide states can be compared as a common set of peptides was used across all states and urea concentrations.

Figure 2.

Effect of E-site nucleotide occupancy on the deuteration levels of αβ-tubulin as determined by an H/DX-MS-based urea denaturation study. Deuteration values are relative to GTP-tubulin measured in the absence of urea. Total protein deuteration values were estimated by summation of peptides spanning the sequence (see Materials and Methods).

These data support several observations. First, there is a notable lack of differentiation between GTP-tubulin and GDP-tubulin in the absence of urea. Second, GDP-tubulin exhibits a step in the denaturation curve with a midpoint of approximately 0.125 M urea. Third, as H/D exchange correlates with protein conformational stability (39), GTP-tubulin is more stable than either GDP-tubulin or GMPCPP-tubulin up to approximately 0.5 M urea. Fourth, GMPCPP-tubulin is markedly less stable than GTP-tubulin over most of the concentration range but most notably in the absence of urea. Here, the deuteration level for GMPCPP-tubulin is equivalent to the nucleotide-free preparation (data not shown).

These findings in the first place suggest a low-energy intermediate state unique to GDP-tubulin, which may be relevant to its assembly properties. Before considering a higher resolution analysis using the peptide-level H/DX-MS data, we tested the reversibility of this intermediate to establish if the underlying conformational state was at or near equilibrium. To measure reversibility, replicate H/DX-MS analyses of GDP-tubulin were conducted at 0.025 M urea, 0.25 M urea, and a 10-fold dilution of 0.25 M urea. Full sequence coverage could not be maintained in the high dilution experiment; thus assessment was restricted to those peptides with a sufficiently high S/N and measurable changes in deuteration between 0.025 and 0.25 M urea (see Figure 3A). All such peptides demonstrated a return to deuteration levels measured in the 0.025 M urea control, thus confirming reversibility (example shown in Figure 3B). This is in general agreement with earlier findings, which demonstrated the functional reversibility of GTP-tubulin below 0.5 M urea (22).

Figure 3.

Reversibility assessment of the structural intermediate in GDP-tubulin suggested by Figure 2, evaluated at 0.25 M urea. (A) Peptides represent the set detectable at 10-fold dilution (190 nM tubulin) and demonstrating a significant increase in deuteration at 0.25 M urea. Experiments were done in triplicate, and error bars represent ±SD. (B) Representative isotopic clusters for VVEPYNSIL, demonstrating reversibility in deuteration level upon dilution.

Higher Resolution Analysis of Nucleotide-Induced Intermediates

The peptide-level H/DX-MS measurements provide an exploration of the response to nucleotide exchange at higher resolution. In the absence of urea, there is little difference in overall stability between GTP- and GDP-tubulin dimers, as noted above. This is shown in Table 1, where perturbations are more conveniently described as deuteration ratios. As may be expected, the peptide on β-tubulin comprising the T3 loop (β91–100) is slightly higher in deuteration for the GDP state; this loop is essential for stabilizing the γ-phosphate on GTP (4). The only other peptide affected is also on β-tubulin (β302–310) in the recently proposed peloruside binding site (19).

Table 1.

Perturbation of Deuterium Labeling for α/β-Tubulin as a Function of Nucleotide Occupancy at the E-Site for 0 M Urea Treatment

| sequence start–stop | peptide sequence | GDP/GTPa | GMPCPP/GTPa | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β91–100 | VFGQSGAGNN | 1.075 | 0.049 | |

| β302–310 | ACDPRHGRY | 1.039 | 0.043 | |

| α68–77 | VDLEPTVIDE | 1.039 | 0.042 | |

| α92–102 | LITGKEDAANN | 1.043 | 0.012 | |

| α93–102 | ITGKEDAANN | 1.079 | 0.021 | |

| α369–376 | AKVQRAVC | 1.078 | 0.001 | |

| α421–427 | AREDMAA | 1.134 | 0.004 | |

| β1–20 | MREIVHIQAGQCGNQIGAKF | 1.061 | 0.001 | |

| β4–20 | IVHIQAGQCGNQIGAKF | 1.081 | 0.011 | |

| β101–111 | WAKGHYTEGAE | 1.114 | 0.004 | |

| β101–112 | WAKGHYTEGAEL | 1.090 | 0.030 | |

| β133–150 | FQLTHSLGGGTGSGMGTL | 1.135 | 0.000 | |

| β133–151 | FQLTHSLGGGTGSGMGTLL | 1.132 | 0.000 | |

| β167–187 | FSVMPSPKVSDTVVEPYNATL | 1.095 | 0.007 | |

| β179–187 | VVEPYNATL | 1.104 | 0.003 | |

| β389–397 | FRRKAFLHW | 1.060 | 0.019 | |

| β408–415 | FTEAESNM | 1.090 | 0.004 |

Ratio of average deuteration levels for indicated states, where deuteration level is calculated as [Mr(measured) – Mr(calc)]/(D – H).

Significance values determined from deuteration levels, n = 8.

A considerably larger set of perturbations was observed when comparing GMPCPP-tubulin with GTP-tubulin. These are mapped on the PDB 1JFF structure (see Figure 4A). The perturbations concentrate at both the E-site in β-tubulin and the N-site in α-tubulin and are shown more clearly in the zoomed views of Figure 4B,C. This figure demonstrates that altered E-site occupancy influences dimer stability in the immediate vicinity of the N-site, particularly the T3 loop. There is a general destabilization of the E-site under GMPCPP-saturated conditions, which is most likely a result of weak binding to the fraction of tubulin unoccupied by either GTP or GDP at the E-site (Figure 1B). This is supported by the observation that the stability of the βT3 loop is comparable to the GTP-bound state (see Figure 4B) and is consistent with GMPCPP being a GTP mimic. A truly void E-site would not likely demonstrate this increased stabilization. Most importantly, it is evident that a destabilization of the E-site is commuted to the N-site, indicating a regulation of the intradimer interface stability via E-site occupancy. This agrees well with an earlier study of the intradimer interface (3).

Figure 4.

(A) Structural representation of α/β-tubulin (α, pale green; β, cyan) at an oblique angle of the protofilament axis to highlight both the E-site and N-site nucleotides, with increases in deuteration arising from GMPCPP treatment relative to GTP superimposed in red. Nucleotides are represented as green spheres. (B) As in (A), with a face-on view of nucleotide at the E-site. (C) As in (A), with a face-on view of GTP at the N-site.

Figure 2 demonstrates that a GDP-dependent state is significantly populated at 0.25 M urea. Table 2 provides the higher resolution labeling data for GDP and GMPCPP (relative to GTP) at this urea concentration. The GDP-induced perturbations of β-tubulin from the perspective of the E-site nucleotide are shown in Figure 5 and differentiate between peptides directly in contact with the nucleotide (yellow) and those distally affected by the change in nucleotide (red). The effect on the N-site is shown by an increased deuteration in critical intradimer contacts βH8 (residues 251–265) and the αT5 loop (residues 170–179) (see Table 2) (4).

Table 2.

Perturbation of Deuterium Labeling for α/β-Tubulin as a Function of Nucleotide Occupancy at the E-Site for 0.25 M Urea Treatment

| sequence start–stop | peptide sequence | GDP/GTPa | GMPCPP/GTP | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α78–91 | VRTGTYRQLFHPEQ | 1.060 | 0.015 | |

| α170–179 | SIYPAPQVST | 1.120 | 0.009 | |

| α170–180 | SIYPAPQVSTA | 1.083 | 0.027 | |

| β4–17 | IVHLQAGQCGNQIG | 1.056 | 0.005 | |

| β4–20 | IVHIQAGQCGNQIGAKF | 1.044 | 0.043 | |

| β74–89 | DSVRSGPFGQIFRPDN | 1.063 | 0.026 | |

| β91–100 | VFGQSGAGNN | 1.079 | 0.032 | |

| β128–132 | DCLQG | 1.082 | 0.032 | |

| β133–151 | FQLTHSLGGGTGSGMGTLL | 1.066 | 0.032 | |

| β212–230 | FRTLKLTTPTYGDLNHLVS | 1.064 | 0.030 | |

| β251–265 | RKLAVNMVPFPRLHF | 1.037 | 0.042 | |

| β256–265 | NMVPFPRLHF | 1.042 | 0.033 | |

| β294–301 | FDSKNMMA | 1.065 | 0.034 | |

| β331–340 | LNVQNKNSSY | 1.070 | 0.049 | |

| β332–340 | NVQNKNSSY | 1.068 | 0.011 | |

| α24–39 | YCLEHGIQPDGQMPSD | 1.042 | 0.049 | |

| α117–135 | LVLDRIRKLADQCTGLQGF | 1.046 | 0.031 | |

| α170–179 | SIYPAPQVST | 1.091 | 0.034 | |

| β4–17 | IVHLQAGQCGNQIG | 1.049 | 0.001 | |

| β74–89 | DSVRSGPFGQIFRPDN | 1.055 | 0.021 | |

| β168–187 | SVMPSPKVSDTVVEPYNATL | 1.049 | 0.034 | |

| β251–265 | RKLAVNMVPFPRLHF | 1.029 | 0.019 |

Ratio of average deuteration levels for indicated states, where deuteration level is calculated as [Mr(measured) – Mr(calc)]/(D – H).

Significance values determined from deuteration levels, n = 9.

Figure 5.

Alternative views of the differential deuteration level data for GDP/GTP at 0.25 M urea, mapped to PDB 1JFF (α-tubulin in pale green, β-tubulin in cyan). (A) Peptides with increased deuteration upon exchange with GDP, and in direct contact with E-site nucleotide, are shown in yellow. All others are shown in red. View is down the z-axis, corresponding to the microtubule protofilament axis viewed from the plus end, where y represents radial direction out from the center of the microtubule. (B) Color scheme as in (A), highlighting the intradimer region.

We then sought to determine if the nucleotide-induced alteration of labeling at the intradimer interface correlates with increased solvent exposure in this region. All peptides with altered labeling at the E-site were removed from the data set for clarity, and the remaining perturbations were mapped to two different structural models of the tubulin dimer (namely, 1JFF shown in Figure 6A and 1SA0 shown in Figure 6B). The 1JFF structure is an accepted model for the “straight” form of tubulin stabilized by taxol (6). The 1SA0 file represents the dimer structure determined from a colchicine-RB3-stabilized “double dimer” of α/β-tubulin and is a model for the “curved dimer” form (8). We compared the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) at the intradimer interface for both PDB files, calculated using the Lee and Roberts method in NACCESS (40), and retained those residues showing an increase in surface area greater than 50% relative to 1JFF (see Figure 6C). Colchicine was removed from 1SA0 for these calculations. The overlap between Figure 6C and the differential deuteration data is strong and suggestive of a straight-to-bent structural transition permitted by nucleotide exchange. This is considered in more detail in the Discussion.

Figure 6.

Differential deuteration data for GDP/GTP at 0.25 M urea, mapped to (A) PDB 1JFF and (B) PDB 1SA0. Data associated with the E-site are removed for clarity. GDP-induced increases in deuteration are again shown in red, with α-tubulin in pale green and β-tubulin in cyan. Peptides indicated in A represent the two sequences in contact with both inter and intradimer interface peptides. Colchicine is displayed in B as yellow spheres. (C) Differential SASA data for 1SA0 relative to 1JFF, restricted to the intradimer interface. Red represents >+50% change (colchicine removed for clarity).

While there is no direct evidence for a distinct intermediate for GMPCPP-tubulin based on the denaturation analysis, the intradimer instability is evident already in the absence of urea, as shown in Figure 4. Upon treatment with 0.25 M urea, further destabilization is induced in this region, but in a less potent manner than was seen with GDP-tubulin (see Table 2). Interestingly, GMPCPP-treated tubulin retains stability of the βT3 loop relative to GTP, as was observed in the absence of urea treatment. Indeed, no measurable destabilization of this loop was seen over the entire urea concentration range studied (data not shown). Other elements of the nucleotide binding pocket undergo progressive destabilization, however, centering on the ribose and nucleobase (see Figure 7). These observations further support that GMPCPP does bind at the E-site.

Figure 7.

View of the differential deuteration level data from the E-site for GMPCPP/GTP at 0.25 M urea mapped to PDB 1JFF as in Figure 5. Color scheme follows Figure 5.

Finally, we then compared these nucleotide-induced perturbations of the free dimer with changes induced by microtubule assembly. These comparisons were focused on the intradimer interface alone. GMPCPP-tubulin was induced to assemble at 37 °C and at 120 μM tubulin. The resulting data were compared with the level of deuteration obtained for GMPCPP-tubulin in the vicinity of the intradimer interface (see Table 3). Substantial interface stabilization can be seen in the large reductions in deuteration resulting from assembly, in every peptide that spans this region. As expected, there were additional reductions in deuteration at the interdimer interface upon assembly, as well as at putative lateral contacts between protofilaments (data not shown). We note that these extensive changes in deuteration upon assembly are inconsistent with those of Xiao et al., where little in the way of measurable deuteration change was noted upon assembly of GTP dimer (20).

Table 3.

Perturbation of Deuterium Labeling in the Intradimer Interface Region Comparing GMPCPP Microtubules with GMPCPP Dimer

| sequence start–stop | peptide sequence | MT/dimera | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| α68–77 | VDLEPTVIDE | 0.133 | 1.2E–06 |

| α92–102 | LITGKEDAANN | 0.459 | 7.9E–07 |

| α170–180 | SIYPAPQVSTA | 0.597 | 4.1E–05 |

| α203–207 | MVDNE | 0.187 | 3.0E–06 |

| α203–208 | MVDNEA | 0.225 | 1.1E–05 |

| α203-211 | MVDNEAIYD | 0.029 | 0.00042 |

| α214–227 | RRNLDIERPTYTNL | 0.916 | 0.0018 |

| α388–398 | WARLDHKFDLM | 0.222 | 2.8E–05 |

| α400–408 | AKRAFVHWY | 0.495 | 0.00032 |

| β130–134 | DCLQG | 0.800 | 0.0024 |

| β233–241 | ATMSGVTTC | 0.117 | 8.5E–07 |

| β233–248 | ATMSGVTTSLRFPGQL | 0.165 | 1.1E–06 |

| β242–248 | LRFPGQL | 0.233 | 2.3E–06 |

| β253–259 | RKLAVNM | 0.365 | 0.0010 |

| β260–267 | VPFPRLHF | 0.713 | 0.00022 |

| β326–332 | KEVDEQM | 0.174 | 2.4E–06 |

| β326–333 | KEVDEQML | 0.209 | 2.5E–05 |

| β343–355 | FVEWIPNNVKTAV | 0.469 | 6.1E–06 |

Ratio of deuteration levels with GMPCPP incorporated in both the microtubule (MT) and the dimer states.

Significance values determined from deuteration levels, n = 6.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Tubulin Dimer

The influence of E-site occupancy on subunit orientation and flexibility was tested computationally with molecular dynamics. During the first 16 ns a number of conformational changes were observed for both GDP-tubulin and GTP-tubulin, relative to the straight dimer model in 1JFF. Three changes occurred in the form of intradimer bending, a domain shift in β-tubulin, and a shift in the βT3 loop (see Supporting Information Figure 1). The intradimer bend is not out of the plane of the microtubule wall but tangential to it. This alternative bending mode is in general agreement with the MD simulations of Gebremichael et al. (41). A difference in orientation between the two nucleotide states was observed at the intradimer interface, suggesting bending is slightly greater for GDP-tubulin. This difference encouraged us to evaluate nucleotide-induced changes in solvent accessibility, which may accompany differential bending.

Hydration

The protein and nucleotide SASA obtained using 1000 frames from the last 10 ns of the simulation was calculated using MSMS (42) and the contribution decomposed by atom. In an attempt to meaningfully compare our MD results to H/DX-MS data, only the SASA of backbone amides were considered, and the data were rendered at lower resolution by quantifying the SASA at the peptide level, using the peptide map from the H/D analysis. This analysis compared GTP-tubulin with an empty E-site as a model for weakly bound GMPCPP in the one case and with GDP-tubulin in the other (see Supporting Information Figure 2). SASA differences between nucleotide states were considered statistically significant if they differed by more than one standard deviation in a first-pass analysis.

In both cases, the greatest changes in SASA occur on β-tubulin, clustered around the E-site. However, the direction of change is both positive and negative, even within the E-site. Decreased solvent accessibility is seen at the base of the nucleotide binding site when compared to an empty site. This correlates with the H/DX data sets for GMPCPP-tubulin, but as one moves outward from the base, the correlation erodes. In the extreme, the T3 loop region demonstrates greater solvent accessibility for the GTP-bound state. This may be a limitation of empty state as a model for GMPCPP; however, we note very similar findings in the simulation of solvent accessibility for the GDP-tubulin. These differences may reflect a combination of unequal thresholds for perturbation detection (SASA vs H/DX-MS) as we note that filtering the SASA data for differences that exceed two standard deviations retains essentially only these changes at the E-site. It may also signal an imperfect correlation between the exchange process and solvent accessibility (43). It is simplistic to interpret the H/DX-MS data solely from the standpoint of altered solvent accessibility, as fluctuations in atomic position due to local unfolding events are better correlated with hydrogen–deuterium exchange than solvent accessibility (43). While a positive correlation between solvent accessibility and exchange processes is intuitively sensible and numerous examples of such a correlation exist, these simulations suggest this may not always be true, particularly when the deviations in exchange rate are small.

Taken together, the slight increase in bending of β-tubulin relative to α-tubulin is best interpreted as an increase in flexibility in the intradimer region, when comparing GDP-tubulin to GTP-tubulin (see Supporting Information Figure 1). It is not accompanied by an obvious increase in solvent accessibility at the intradimer interface, at least for an unperturbed state.

DISCUSSION

In this study, nucleotide exchange was undertaken under conditions that controlled for overall protein stability, incubation time, and degree of assembly. One common method for nucleotide exchange involves treatment with alkaline phosphatase, followed by purification and reintroduction of nucleotide. While such methods may be required for very high conversion, simple incubation of αβ-tubulin with excess free nucleotide promoted a acceptable conversion at the E-site for GDP and GTP (see Figure 1C,D). This level of altered occupancy is sufficient for a comparison of nucleotide states and had the advantage of strong control over sample composition and handling. We chose to avoid multistep nucleotide exchange processes for all nucleotide preparations in the interests of controlling the buffer composition and reducing excessive error in the deuteration measurements arising from these strategies (data not shown).

Using these controlled buffer conditions, the H/DX-MS data show that the αβ-tubulin dimer can undergo distal perturbations as a result of altered nucleotide occupancy at the E-site. Weakly bound GMPCPP highlights an allosteric control of the N-site at the intradimer region and as far away as α369–376, almost 80Å removed from the E-site (see Table 1 and Figure 4). The data show that allosteric control is possible but do not in themselves provide evidence of a differential control based on GDP vs GTP occupancy. Such control may appear to be nonexistent when comparing these two states in the absence of urea treatment. However, a low-lying intermediate state detectable at very low urea concentrations favors the existence of a unique state with relevance to tubulin assembly processes.

The higher resolution analysis of this nucleotide-induced state presents a localized region of increased labeling with strong similarities to the colchicine binding site (see Figure 6). This region strongly overlaps the difference in solvent-accessible surface area between the αβ-tubulin structures representative of the straight and curved models, respectively. This may suggest that GTP hydrolysis reduces the energy barrier to an outwardly curved state although precautions are warranted. The altered H/D exchange levels cannot readily convey the magnitude of a domain motion or its precise direction; therefore, we do not suggest that the intermediate we observe is necessarily equivalent to the 1SA0 structure. We do suggest that the very low urea concentration required to induce this intermediate state implies that it is reasonably well populated under native conditions and that nucleotide exchange to GDP enhances an underlying flexibility in this region. The observation of a curved state is not inconsistent with this (8). It rather suggests that various orientations are inducible, dependent upon the nature of the applied stabilizer. Whether the enhanced flexibility observed for GDP-tubulin affects ligand binding is an open question; however, we do note that at least one colchicine-site ligand shows a slightly decreased affinity for GDP-tubulin compared to GTP-tubulin (44).

These observations form the basis for a model in which the unperturbed free dimer is characterized by considerable flexibility around the intradimer interface. Intradimer plasticity is evident in molecular dynamics simulations by Gebremichael et al. (41) and in the current study. Both sets of simulations describe only minor differences between the conformations of GDP- and GTP-tubulin, which are not in the direction suggested by 1SA0. Our simulations disagree with Gebremichael et al. on the direction of the GDP-tubulin bend relative to the 1JFF structure; however, given the limited sampling of both calculations, this very likely reflects the extensive flexibility of the dimer in this region. While this differential flexibility is not seen in the H/DX-MS data for GDP-tubulin and GTP-tubulin in the absence of urea, it may reflect insufficient sensitivity to detect such subtle changes. Comparing the H/DX-MS results between the dimer and the assembled state, however (see Table 3), highlights the dramatic stabilization of the intradimer interface achieved upon assembly. It may therefore be argued that none of the existing tubulin structures adequately convey the high flexibility of the free dimer, at least in this region.

Other studies have presented arguments for the existence of a curved equilibrium orientation for both GTP- and GDP-tubulin (reviewed in ref 12). More recently, an SAXS study of GTP- and GDP-tubulin proposed that both nucleotide states are essentially identical and consistent with a known curved control (11). Our findings do not negate these studies but do suggest that flexibility may be a more significant characteristic of the intradimer interface than its equilibrium orientation. An additional outward bending mode does appear permissible for GDP-tubulin in the absence of selective perturbants. The extensive underlying flexibility with a preference for outward curvature is consistent with the diversity of structures permitted by GDP-tubulin but also with their general description as outwardly curved (6, 8, 45).

We note that additional conformational responses accompany the nucleotide exchange, which argue against defining the nucleotide dependency in terms of a singular perturbation around the intradimer interface. Conformational instabilities abound in the vicinity of the E-site in β-tubulin, as seen in the urea-induced intermediate. In addition to the βT3 loop, GDP destabilizes the N-terminal end of the H6–H7 loop region (β212–230) and the H2 loop region (β74–89) (see Figure 5A). The H6–H7 loop region has been implicated as a sensor of hydrolysis state in earlier structural studies (46), which appears consistent with our findings. Destabilizing this region under the action of hydrolysis promotes a hinging action between the intermediate domain and the nucleotide binding domain (47), drawing contact away from the adjacent dimer across the interdimer interface. Destabilizing the H2 loop at the interdimer interface as noted would also destabilize contacts with the adjacent dimer. Collectively, these instabilities detected by H/DX-MS indicate that hydrolysis could directly impact inter-dimer affinity, which is consistent with earlier findings (3). Less obvious is the effect of hydrolysis on putative lateral contacts. The H2 loop region may bridge into lateral contact areas, but this is not clear from the existing structural studies (46). The effects of hydrolysis appear to propagate through the interior of β-tubulin (see Figure 5B). These may drive the intradimer instability discussed above, thus presenting unfavorable lateral contacts in β-tubulin for the hydrolyzed state, or may alter lateral contacts more directly. Unfortunately, this cannot be conclusively determined from the current data.

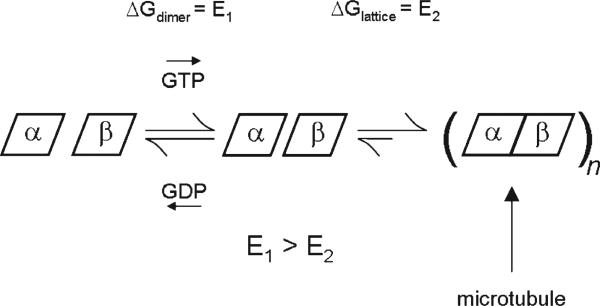

Overall, our study suggests a revised assembly model where the free dimer presents two energetic penalties upon assembly, with respect to the intradimer interface (see Figure 8). The first penalty is suggested by the GDP-tubulin state observed in the denaturation study, perhaps represented by an average conformation with some degree of curvature relative to GTP-tubulin but more likely representing greater flexibility than GTP-tubulin. We propose that this state is significantly populated upon hydrolysis under typical assembly conditions. Restricting this flexibility represents an entropic barrier to assembly into straight microtubules not shared by GTP-tubulin (E1, Figure 8). In this model, molecular perturbations such as colchicine can drive the equilibrium toward a specific bent state. Colchicine binding need not require GDP, however. As the intradimer region retains significant flexibility regardless of E-site nucleotide occupancy, a subset of the conformational ensemble would permit colchicine trapping and induction of an outwardly bent state. The second penalty is shared by both GTP-tubulin and GDP-tubulin, in the form of a lattice-induced stabilization (E2, Figure 8). This may be accompanied by an overall straightening from an equilibrium curved position as suggested by others (11, 12) but does not absolutely require it; we suggest it simply reflects the significant energy required to restrict the flexibility of the free dimer.

Figure 8.

Proposed model of nucleotide control over αβ-tubulin assembly from an intradimer perspective. The most flexible state of αβ-tubulin (left dimer, symbolized by greater spacing between α- and β-tubulin) is shown in equilibrium with a less flexible state (right dimer, symbolized by reduced spacing between α- and β-tubulin), with the relative population of states dictated at least in part by nucleotide occupancy, as shown. Intradimer flexibility is stabilized by the straight microtubule lattice upon assembly (symbolized by no spacing between α- and β-tubulin). On the basis of the significantly larger change in deuteration upon assembly, we suggest that the energy required for intradimer stabilization of GTP-tubulin (E2) is only slightly less than that required to stabilize GDP-tubulin (E1 + E2).

The proposed model presents a merging of the lattice model and the free-dimer allosteric model (11). A nucleotide-independent state dominates, which requires significant lattice energy to stabilize. This is in keeping with the lattice model (12) but departs from it in the description of the dimer state and the effect of nucleotide exchange on flexibility. The model suggests both GTP- and GDP-tubulin exist in an equilibrium bent state and that GTP binding actually reduces the free energy difference between the curved and straight form. It proposes that GTP-tubulin permits greater flexibility at the intradimer interface, sufficient to promote straightening. For an incoming GTP-tubulin dimer, lattice contacts would be favored at β-tubulin, but unless the lattice is primed with GTP-tubulin, insufficient binding energy would be available to stabilize the dimer (11, 12). The revised model based on our data suggests the inherent flexibility at the intradimer interface provides the most significant energy barrier to straightening and that it is GDP-tubulin that exhibits greater flexibility than GTP-tubulin. This returns an element of the free-dimer allosteric model in proposing a dimer-based, GDP-dependent energy penalty to lattice incorporation. Although small, any such energy penalty must be of low magnitude in order to explain the existence of lattice-bound GDP-tubulin. This concept is not unlike that proposed by Wang and Nogales (6), in which lattice effects follow a dimer-based conformational change. Retaining a role for allosteric effects in the free dimer rationalizes the characteristics of lattice instability in the first place, where hydrolysis to GDP-tubulin leads to the splaying of outwardly curved proto-filaments that retain a bend at the intradimer interface. This notion is captured in the first version of the lattice model (12), although it proposed GTP-tubulin as the more flexible form.

The revised model also rationalizes how GDP-tubulin is excluded at the plus end of a growing microtubule, in favor of a “GTP cap”. A pure lattice model does not differentiate between a GTP-tubulin and GDP-tubulin conformations and thus does not suggest how the latter would be selected against at the growing end (48). Our data suggest hydrolysis weakens lattice contacts and increases intradimer curvature, which would combine to disfavor inclusion into the growing end. Revising the lattice model in this fashion, to allow a role for the nucleotide as an allosteric effector in the free dimer, remains consistent with the kinetic model of nucleation and assembly as proposed by Rice et al. (11).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the Alberta Cancer Board, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and intramural funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH. D.C.S. gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Research Chair program and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). J.T. gratefully acknowledges generous support of the Allard Foundation and Alberta Advanced Education and Technology.

Abbreviations: GTP, guanosine triphosphate; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; GMPCPP, guanosine 5′-[(α,β)-methylene]triphosphate; H/DX, hydrogen/deuterium exchange; MS, mass spectrometry; LC, liquid chromatography; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; TOF, time of flight; PIPES, piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid); SAXS, small-angle X-ray scattering; PDB, Protein Data Bank; MD, molecular dynamics; rmsd, root-mean-squared deviation; SEC, size-exclusion chromatography; SASA, solvent-accessible surface area.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Additional figures describing the MD simulations and time-averaged SASA determinations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menendez M, Rivas G, Diaz JF, Andreu JM. Control of the structural stability of the tubulin dimer by one high affinity bound magnesium ion at nucleotide N-site. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:167–176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplow M, Fee L. Dissociation of the tubulin dimer is extremely slow, thermodynamically very unfavorable, and reversible in the absence of an energy source. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2120–2131. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E01-10-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. Refined structure of alpha beta-tubulin at 3.5Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:1045–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlier MF, Pantaloni D. Kinetic analysis of guanosine 5′-triphosphate hydrolysis associated with tubulin polymerization. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1918–1924. doi: 10.1021/bi00510a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- =6.Wang HW, Nogales E. Nucleotide-dependent bending flexibility of tubulin regulates microtubule assembly. Nature. 2005;435:911–915. doi: 10.1038/nature03606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nogales E, Wang HW. Structural mechanisms underlying nucleotide-dependent self-assembly of tubulin and its relatives. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature. 2004;428:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogales E, Whittaker M, Milligan RA, Downing KH. High-resolution model of the microtubule. Cell. 1999;96:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chretien D, Fuller SD, Karsenti E. Structure of growing microtubule ends: two-dimensional sheets close into tubes at variable rates. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:1311–1328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice LM, Montabana EA, Agard DA. The lattice as allosteric effector: structural studies of alphabeta- and gamma-tubulin clarify the role of GTP in microtubule assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:5378–5383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801155105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buey RM, Diaz JF, Andreu JM. The nucleotide switch of tubulin and microtubule assembly: a polymerization-driven structural change. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5933–5938. doi: 10.1021/bi060334m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englander SW, Krishna MM. Hydrogen exchange. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:741–742. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai Y, Sosnick TR, Mayne L, Englander SW. Protein folding intermediates: native-state hydrogen exchange. Science. 1995;269:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner MH, Wemmer DE. Identification of a protein-binding surface by differential amide hydrogen-exchange measurements. Application to Bowman-Birk serine-protease inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:873–889. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90407-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand GS, Law D, Mandell JG, Snead AN, Tsigelny I, Taylor SS, Ten Eyck LF, Komives EA. Identification of the protein kinase A regulatory RIalpha-catalytic subunit interface by amide H/2H exchange and protein docking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:13264–13269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wildes D, Marqusee S. Hydrogen exchange and ligand binding: Ligand-dependent and ligand-independent protection in the Src SH3 domain. Protein Sci. 2005;14:81–88. doi: 10.1110/ps.04990205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englander JJ, Del Mar C, Li W, Englander SW, Kim JS, Stranz DD, Hamuro Y, Woods VL., Jr. Protein structure change studied by hydrogen-deuterium exchange, functional labeling, and mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 2003;100:7057–7062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232301100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huzil JT, Chik JK, Slysz GW, Freedman H, Tuszynski J, Taylor RE, Sackett DL, Schriemer DC. A unique mode of microtubule stabilization induced by peloruside A. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:1016–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao H, Verdier-Pinard P, Fernandez-Fuentes N, Burd B, Angeletti R, Fiser A, Horwitz SB, Orr GA. Insights into the mechanism of microtubule stabilization by Taxol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:10166–10173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603704103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guha S, Bhattacharyya B. A partially folded intermediate during tubulin unfolding: Its detection and spectroscopic characterization. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6925–6931. doi: 10.1021/bi00021a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sackett DL, Bhattacharyya B, Wolff J. Local unfolding and the stepwise loss of the functional properties of tubulin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12868–12878. doi: 10.1021/bi00209a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frigon RP, Lee JC. The stabilization of calf-brain microtubule protein by sucrose. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1972;153:587–589. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JC, Timasheff SN. The stabilization of proteins by sucrose. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:7193–7201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slysz GW, Percy AJ, Schriemer DC. Restraining expansion of the peak envelope in H/D exchange-MS and its application in detecting perturbations of protein structure/dynamics. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:7004–7011. doi: 10.1021/ac800897q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JC, Miller JN. Statistics for Analytical Chemistry. 3rd ed. Ellis Harwood; Amsterdam: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seckler R, Wu GM, Timasheff SN. Interactions of tubulin with guanylyl-(beta-gamma-methylene)diphosphonate. Formation and assembly of a stoichiometric complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:7655–7661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature. 1998;391:199–203. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foloppe N, MacKerell AD. All-atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:86–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Vangunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald—an N.Log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeeberg B, Caplow M. Determination of free and bound microtubular protein and guanine nucleotide under equilibrium conditions. Biochemistry. 1979;18:3880–3886. doi: 10.1021/bi00585a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Correia JJ, Baty LT, Williams RC., Jr. Mg2+ dependence of guanine nucleotide binding to tubulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:17278–17284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyman AA, Salser S, Drechsel DN, Unwin N, Mitchison TJ. Role of GTP hydrolysis in microtubule dynamics: Information from a slowly hydrolyzable analogue, GMPCPP. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:1155–1167. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huyghues-Despointes BM, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. Protein conformational stabilities can be determined from hydrogen exchange rates. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:910–912. doi: 10.1038/13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee B, Richards FM. The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J. Mol. Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gebremichael Y, Chu JW, Voth GA. Intrinsic bending and structural rearrangement of tubulin dimer: Molecular dynamics simulations and coarse-grained analysis. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2487–2499. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Spehner JC. Reduced surface: An efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers. 1996;38:305–320. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199603)38:3%3C305::AID-BIP4%3E3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bahar I, Wallqvist A, Covell DG, Jernigan RL. Correlation between native-state hydrogen exchange and cooperative residue fluctuations from a simple model. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1067–1075. doi: 10.1021/bi9720641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbier P, Peyrot V, Leynadier D, Andreu JM. The active GTP- and ground GDP-liganded states of tubulin are distinguished by the binding of chiral isomers of ethyl 5-amino-2-methyl-1,2-dihydro-3-phenylpyrido[3,4-b]pyrazin-7-yl carbamate. Biochemistry. 1998;37:758–768. doi: 10.1021/bi970568t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amos LA. Bending at microtubule interfaces. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:745–747. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, DeRosier DJ, Nicholson WV, Nogales E, Downing KH. Microtubule structure at 8Å resolution. Structure. 2002;10:1317–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amos LA, Lowe J. How Taxol stabilises microtubule structure. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R65–R69. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)89002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dimitrov A, Quesnoit M, Moutel S, Cantaloube I, Pous C, Perez F. Detection of GTP-tubulin conformation in vivo reveals a role for GTP remnants in microtubule rescues. Science. 2008;322:1353–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1165401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.