Abstract

Scientists have long hypothesized the existence of tissue-specific (somatic) stem cells and have searched for their location in different organs. The theory that adrenocortical organ homeostasis is maintained by undifferentiated stem or progenitor cells can be traced back nearly a century. Similar to other organ systems, it is widely believed that these rare cells of the adrenal cortex remain relatively undifferentiated and quiescent until needed to replenish the organ, at which time they undergo proliferation and terminal differentiation. Historical studies examining cell cycle activation by label retention assays and regenerative potential by organ transplantation experiments suggested that the adrenocortical progenitors reside in the outer periphery of the adrenal gland. Over the past decade, the Hammer laboratory, building on this hypothesis and these observations, has endeavored to understand the mechanisms of adrenocortical development and organ maintenance. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge of adrenal organogenesis. We present evidence for the existence and location of adrenocortical stem/progenitor cells and their potential contribution to adrenocortical carcinomas. Data described herein come primarily from studies conducted in the Hammer laboratory with incorporation of important related studies from other investigators. Together, the work provides a framework for the emerging somatic stem cell field as it relates to the adrenal gland.

I. Introduction

II. Adrenal Anatomy

III. Adrenal Gland Development and Establishment of the Definitive (Adult) Cortex

IV. Anatomic Evidence in Support of Adrenocortical Stem/Progenitor Cells

V. Regenerative Capacity of Adrenal Cortex

VI. Clonal Relationship of Undifferentiated Subcapsular Cells to Differentiated Cortical Cells

VII. Dual Role of Sf1-Mediated Transcription in Adrenocortical Development and Steroidogenesis

- VIII. Regulation of Sf1-Dependent Gene Expression in the Subcapsular Cortex by Endocrine and Paracrine Signaling

- A. Sf1 and Dax1 interactions

- B. Endocrine signaling

- C. Paracrine signaling

- IX. Adrenocortical Carcinomas in the Context of Cancer Stem Cells

- A. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and IGF-II

- B. Familial adenomatous polyposis

- C. Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- D. Telomeres, telomerase, stem cells, and cancer

- X. Future Directions

- A. Tissue-specific silencing of Sf1 gene expression

- B. Pod1 null mice

- C. Hedgehog signaling

- D. MicroRNAs

- E. Notch signaling pathway

XI. Summary

I. Introduction

Thomas Addison made a seminal contribution to the field of clinical endocrinology by defining the syndrome of primary autoimmune adrenal failure in the late 1830s. Over 40 years later, Gottschau described the processes of adrenal gland replenishment from the cells of an outer germinal layer and adrenal cellular breakdown in the “zona consumptive” at the interface of the adrenal cortex and medulla. In 1909, Bongomolez confirmed these findings and observed that proliferation in the adrenal cortex was restricted to the subcapsular gland and that cells from this region “migrated” centripetally to populate the inner cortex. Nearly 40 more years passed when Edward Kendall began purifying the major adrenocortical hormones and basic researchers were beginning to uncover the regenerative potential of the adrenal capsule/subcapsular unit through a series of innovative enucleation and lineage-tracing studies. Although these studies provided seminal observations in support of stem and/or progenitor-like cells in the adrenal cortex, work in this area was soon eclipsed by the availability of powerful cellular and molecular biology techniques that were applied to the growing field of steroidogenesis. Only recently, as gene-targeting technology has emerged to apply molecular approaches to whole organ studies, have scientists begun to readdress the questions raised by our scientific predecessors of the early 1900s. What are the mechanisms of adrenocortical cellular replenishment and maintenance? What are the mechanical and chemical stimuli that induce subcapsular proliferation? What is the relationship of the adrenal capsule to the proliferating subcapsular cells? In addition to their contribution to the development and the maintenance of the adrenal cortex, do these cells play a role in pathogenic states of the organ, namely hypoplasias and cancer? Such questions are at the heart of the burgeoning field of tissue stem/progenitor cells. This review will address the concept of adrenocortical somatic stem cells through an examination of the potential roles of such cells in development and homeostatic maintenance of the organ as well as their contributions to developmental pathogenesis and tumorigenesis. We will detail available data stemming from studies primarily conducted in the Hammer laboratory, with incorporation of related works from other groups contributing to this emerging field.

II. Adrenal Anatomy

The adrenal gland, a component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, is a major hormone-secreting organ. The gland is composed of two functionally distinct organs. The medulla, derived from neural crest cells of neuroectoderm lineage, synthesizes catecholamines that facilitate the acute mammalian stress or “fight-or-flight” response. The cortex, derived from the cells of the intermediate mesoderm, synthesizes steroid hormones that mediate body homeostasis and chronic stress responses. The cortex is organized into three concentric zones, zona glomerulosa (zG), zona fasciculata (zF), and zona reticularis (zR), each responsible for the production of different steroid hormones. In 1866, Arnold (2) first described the zonal organization of the cortex with nomenclature that is still in use today (2,3). The cells of the zG are organized in rounded clusters around capillary coils or glomeruli and synthesize mineralocorticoids. The cells of the zF synthesize glucocorticoids and are arranged in radial rows separated by trabeculae and blood vessels. The cells of the zR are arranged in a uniform reticular net of connective tissue and blood vessels and synthesize a subset of sex steroid precursors, including the neurohormone dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. Although histological and functional differences exist between the adrenal cortices of various mammalian species (mainly the absence of zR and the presence of the fetal/X-zone in some rodents), common developmental principles appear to mediate the formation and homeostatic maintenance of the gland (2,3,4).

III. Adrenal Gland Development and Establishment of the Definitive (Adult) Cortex

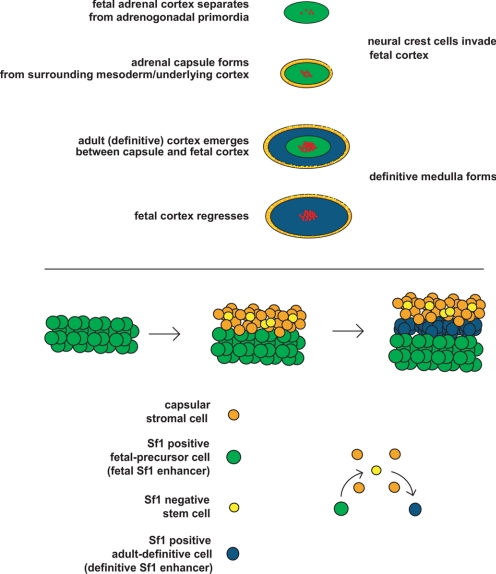

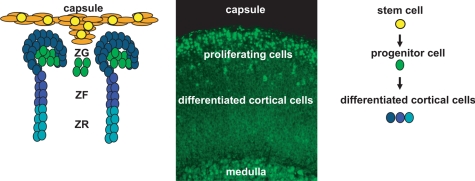

Adrenal gland development in the mammal is defined by discrete histological events (4,5,6). The first milestone is marked by the proliferation of the mesoderm-derived coelomic epithelia and underlying mesonephric mesenchymal cells, forming the embryonic adrenogonadal primordia (AGP) that reside between the primitive urogenital ridge and the dorsal mesentery (7,8) [reviewed by Else and Hammer (5) and Kim and Hammer (9)]. Essential for the formation of the adrenogonadal primordium is expression of the orphan nuclear receptor, Sf1 (Nr5a1, nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1, or Ad4BP). Although Sf1 expression is critical, a variety of loss-of-function studies indicate that additional transcription factors including pre-B cell leukemia homeobox 1 (Pbx1), odd-skipped related 1, and polycomb group protein M33 also participate in specification and/or expansion of the AGP (10,11,12). The bilateral AGP then divide into the adrenal primordia (adrenal blastema, often referred to as the fetal adrenal or fetal zone) and the gonadal primordia. The molecular specification of the adrenal primordia is initiated through the up-regulation of Sf1 expression by Wilm’s tumor 1 and Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain 2 (13). Upon separation of the adrenal primordia from the AGP, a different transcription complex containing the homeobox protein PKNOX1, homeobox gene 9b, and Pbx1 is recruited to maintain fetal zone expression of Sf1 through activation of a fetal zone-specific Sf1 enhancer (FAdE). Subsequently, Sf1 itself provides feed-forward activation of its own expression in this compartment (14). Coincident with this transcriptional cascade is the coalescence of the mesenchymal capsule around the fetal cortex (5,9). Once encapsulation is complete, the development of the definitive cortex (definitive zone or adult cortex) becomes evident between the capsule and fetal cortex (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Top, Stages of adrenal gland development. Bottom, Model of capsular and definitive zone cell lineage.

Because the cells of the definitive cortex are continually renewed throughout life, a unified model for the formation and maintenance of this structure is paramount. In a previous review, we provided two distinct possibilities for the developmental establishment and postnatal maintenance of the definitive cortex (9). First, the definitive cortex arises from the precursors within the mesenchymal capsule (i.e., the capsule contains the adrenal cortical stem cells) (9). Second, the fetal cortex contains precursors, which give rise to the adult cortex [i.e., capsule serves the role of stem cell “niche” (9)]. Recent and emerging data allow for a reconciliation of these two models in the form of an adrenocortical stem/progenitor niche hypothesis.

In the burgeoning field of stem cell biology, the concept of stem cell residence is used to define the complex microenvironment composed of the stem cells and the supporting niche cells. The stem cell niche provides structural and trophic support, topographical information, and physiological cues to resident stem cells that govern stem cell fate (i.e., self-renewal and symmetric or asymmetric division) (15,16,17). Data from organ systems such as the blood, gonad, and hair follicle reveal conserved niche components that include stromal support cells, extracellular matrix, and vasculature (15,16). Multiple studies have characterized a complex network of capillary beds together with an enrichment of extracellular matrix components within the adrenal capsule (18,19,20,21,22,23), and we suggest that these components provide the needed structural and physiological support to the adrenocortical stem cells. The capsular niche would serve both to recruit stem cells during development and to regulate stem cell fate throughout the life of the organism (16,24). We favor a model whereby the adrenocortical stem cells reside within the capsule itself (i.e., the capsule serves as the physical site of the adrenocortical stem cell as well as the niche) and give rise to the underlying definitive cortex in response to a variety of capsular/subcapsular morphogenic signals (Wnt, Shh, Notch). Indeed, circumstantial evidence comes from chimeric mouse studies that detail concordant clonality of patches of capsular cells and underlying cortical radial stripes (i.e., chimeric patches in capsule lined up with chimeric radial stripes in the cortex), suggesting a shared origin (25,26,27,28).

Although these data are provocative, there remains no conclusive molecular or genetic evidence confirming whether the capsule serves as a stem/progenitor cell pool and/or as a niche for the subcapsular cells. Therefore, determining the lineage relationship between the fetal cortex (precursor population), capsule, and definitive cortex is of paramount importance. Recent data from the Morohashi lab (14,29) demonstrate that the definitive cortex is derived from the fetal adrenal cortex. The data suggest that the FAdE is first shut off (in fetal cells destined to become definitive cells), followed by the activation of a definitive Sf1 enhancer in the emerging definitive cells (29). However, data emerging from our laboratory suggest that Sf1 expression is actively repressed in a subset of capsular cells by the capsule-specific helix-loop-helix (HLH) factor Pod-1 and that genetic loss of Pod-1 results in activation of Sf1 in a subset of capsular cells and an increased number of Sf1-expressing cells in the underlying cortex. Because the definitive cortex only becomes evident between the developing capsule (Sf1 negative) and fetal adrenal cells (Sf1 positive), we propose a model whereby the fetal precursor cells give rise to Sf1-negative cells that participate in the formation of the capsule (stem cell residence). In such a model, mitogenic/morphogenic signals (endocrine and capsular paracrine/autocrine) activate the Sf1-negative capsular stem cells that exit from the capsular niche into the subcapsular environment, where they commence Sf1 expression. Current data suggest that this process requires the loss of capsular Pod-1 expression in the Sf1-negative cell, subsequent activation of the yet to be determined definitive Sf1 enhancer, and ultimate expression of Sf1 in subcapsular rapidly amplifying progenitor cells. Data in support of these models are discussed throughout this review.

IV. Anatomic Evidence in Support of Adrenocortical Stem/Progenitor Cells

What is the evidence for the existence of adrenocortical stem/progenitor cells? While the glomerulosa has been classically defined as a homogenous aldosterone-producing zone directly under the capsule, three observations suggest that the glomerulosa is composed of multiple cell types that participate in the homeostatic maintenance of the adrenal cortex. Early microscopic studies of the adrenal glands of different vertebrates suggested the presence of peripheral undifferentiated cells. For example, in the arctic seal (Phoca vitulina vitulina), clusters of rounded large cells, referred to as adrenocortical blastema, reside within both the capsule and trabeculae that arise from the capsule as perpendicular cords piercing into the outer cortex (30). These cells contain conspicuously large euchromatin-rich nuclei and have high ratios of both rough to smooth endoplasmic reticulum and cristae-type to tubulus-type mitochondria, all characteristic features of less-differentiated cells (30). Because these cells have the histological appearance of progressive centripetal transition to the juxtaposed glomerulosa cells (30), it has been hypothesized that the blastema define a population of undifferentiated cells that undergo both proliferation and differentiation in response to homeostatic stimuli. Recent observational studies in the grass snake (Natrix natrix L.) suggest a similar peripheral pool of undifferentiated transitional cells that have the potential to differentiate into steroidogenic adrenocortical cells (31). The glomerulosa of other species exhibit variable thicknesses and tortuosity with a wide range of embedded, undifferentiated clusters that at times coalesce into circumferential zones of undifferentiated cells. The restricted circumferential expression of preadipocyte factor 1 or Pref-1 (a factor that serves to inhibit differentiation in a variety of tissues) in the glomerulosa of the rat supports such a hypothesis that the glomerulosa layer is composed of cells of varying degrees of differentiation (i.e., progenitor cells). Specifically, an outer layer expresses both Pref-1 and aldosterone synthase, a middle inner layer expresses only Pref-1, and an inner layer above the fasciculata zone expresses no Pref-1, aldosterone synthase, or 11β-hydroxylase (32). In the rat, the two inner aldosterone synthase-negative zones of the glomerulosa are referred to as the zona undifferentiated or zona intermedia (33). In the mouse adrenal, where a defined undifferentiated zone is not observable, such cells might be scattered between differentiated glomerulosa cells. The paucity of expression of certain steroidogenic enzyme genes (Cyp11b1 and Cyp11b2) in these cells has fueled the hypothesis that these cells undergo a morphological transition into differentiated steroidogenic cells of the zG (34,35,36).

Indeed, early histological studies place new adrenocortical cells in the most peripheral position of cellular columns/projections arising from the capsule (37). It has been proposed that the slowly proliferating cells in the capsule generate daughter cells that eventually are centripetally displaced to populate the adrenal cortex (38,39). The robust mitosis and proliferation in the subcapsular region (40,41) is more consistent with transiently amplifying progenitor population. Results of experiments employing radioactive thymidine, bromodeoxyuridine pulse chase, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen staining are consistent with this notion and indicate that subcapsular cells of the rat adrenal replenish the neighboring steroidogenic zones, suggesting that this population provides a pool of progenitors that serve to maintain the functional capacity of the cortex (33,34,36,41,42,43).

V. Regenerative Capacity of Adrenal Cortex

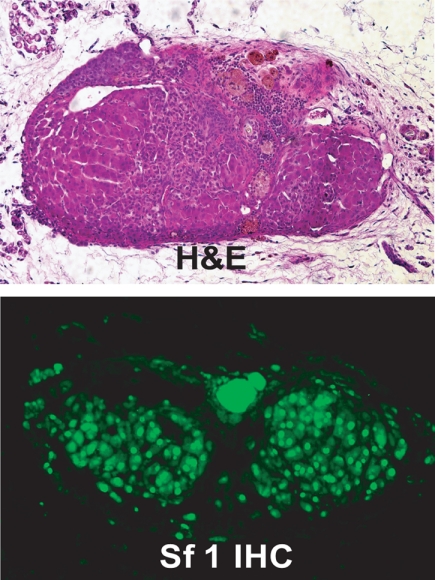

Does the adrenal cortex have regenerative capacity? Where do the adrenocortical stem/progenitors reside? The observations of undifferentiated adrenocortical cells proliferating and repopulating the organ are further supported by experiments assessing the regenerative potential of the adrenal gland. Although primary adrenocortical cells transplanted sc in immunodeficient mice form functional adrenocortical tissue within the grafted host and can respond to hormonal stimuli, the tissue lacks zonal organization and fails to undergo continued homeostatic cellular renewal (i.e., lacks viability after serial transplantation), presumably due to the absence of an intact capsular/subcapsular unit (44,45,46,47). Indeed, when the majority of the adrenal tissue in the living rat is removed, leaving only the capsule and the underlying subcapsular tissue (adrenal enucleation), functional adrenal tissue still regenerates. Moreover, ongoing studies in our group suggest that even when the capsule/subcapsular unit of a donor mouse is removed and sc implanted into syngeneic mice, regenerative potential is maintained, as evidenced by regrowth of Sf1-positive tissue (Fig. 2). Together these data support an essential role of the capsular/subcapsular unit in adrenocortical growth maintenance.

Figure 2.

Histological analysis of a regenerating mouse adrenal gland. Top, Hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of an enucleated mouse adrenal gland transplanted into the kidney capsule. Bottom, Immunohistochemistry with an anti-Sf1 antibody.

We believe that the proliferating cells arising in the remaining capsule/subcapsular unit initiate the reformation of the functional adrenal cortex. The majority of the regeneration takes place within first 15 d of the enucleation, and repopulation of the entire cortex is accomplished in approximately 3 months (48,49,50,51). Intuitively, the process of regeneration requires both the proliferation and differentiation of these cells. Although the endocrine signals (angiotensin II and ACTH) that define the differentiation or steroidogenic fate of the subcapsular cells have been well studied for decades (48), the autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine proliferative signals have just recently begun to emerge as major regulators of stem/progenitor cell populations. The requirement for ACTH in differentiation is highlighted by the adrenal insufficiency and adrenal hypoplasia in Pomc knockout mice and patients with proopiomelanocortin, Mc2R or Mc2R accessory protein mutations (5,52,53,54,55,56). Studies detailed below have begun to dissect how various signaling pathways regulate the capsular/subcapsular unit to maintain the dynamic balance of proliferation and differentiation that is essential to the function of the adrenal cortex as a central mediator of the mammalian stress response.

VI. Clonal Relationship of Undifferentiated Subcapsular Cells to Differentiated Cortical Cells

Although enucleation studies indicate that the capsular/subcapsular unit has the capacity to proliferate and differentiate, experiments have not been designed to establish the lineage relationships between inner and outer cells of the intact cortex. Immunohistochemical analyses of the adrenal glands of chimeric and transgenic mice (utilizing β-galactosidase reporters under the control of either the cytomegalovirus or steroidogenic gene promoter) reveal variegated expression of chimeric or reporter genes in cord-like radial stripes extending from the periphery to the corticomedullary boundary, consistent with a clonal origin of cells within each radial stripe. The data support the hypothesis that the adrenal cortex is maintained through proliferation and clonal replenishment of peripheral cells that undergo centripetal displacement and differentiation in response to endocrine stimulation (26,57,58,59,60).

VII. Dual Role of Sf1-Mediated Transcription in Adrenocortical Development and Steroidogenesis

Studies in which ACTH mediates steroidogenesis/differentiation coupled with the appropriate molecular tools have provided our laboratory and many others with the means to examine the processes of differentiation and proliferation in organ homeostasis. The independent discoveries by the Parker and Morohashi groups (7,61,62) of Sf1/Ad4BP as a critical transcriptional mediator of both steroidogenesis and organ development have provided seminal findings in the field of adrenocortical stem/progenitor biology. The orphan nuclear receptor Sf1 was discovered in both laboratories by its ability to interact with and transactivate promoters of ACTH-activated steroidogenic enzyme genes (61,63). Soon after it was shown to be essential for adrenocortical development, as evidenced by the adrenal aplasia of Sf1 null mice (7,63,64,65).

The subcapsular cells of the adrenal cortex are predicted to have the capacity to both proliferate and differentiate. Studies in other systems have detailed the processes by which quiescent undifferentiated cells undergo rapid and dynamic nuclear architectural changes as they become engaged in proliferative or differentiation programs. Preceding the necessary formation of the euchromatin and initiation of active transcription, many covalent modifications occur on both DNA and transcriptional factors that enable cell cycle-specific gene activation (66). In the mid 1990s, with no definitive Sf1 ligand, the mechanism by which peptide hormone-initiated signaling cascades result in activation of Sf1-dependent transcription was not entirely clear. We began exploring whether posttranslational modifications of Sf1 differentially activated proliferative and/or differentiation programs.

We first built on earlier observations in Holly Ingraham’s laboratory by Hammer et al. (67) that phosphorylation of Sf1 serine 203 by Erk1/2 plays a critical role in cofactor recruitment and Sf1-dependent transcriptional activation. Although we posited that phosphorylation of Sf1 in response to ACTH may be critical for gene activation, other work by Sewer and Waterman (68) soon demonstrated clearly that dephosphorylation of Sf1 also served a critical role in the activation of certain ACTH-dependent targets. We wondered whether these observations were mutually exclusive or whether both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are essential for different phases of transcriptional activation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments had recently revealed that transcriptional activation by ligand-dependent nuclear receptors is a dynamic process, occurring in an ordered, stepwise, and cyclical fashion (69,70). Therefore, our lab sought to explore whether ACTH might coordinate Sf1-mediated transcription through a series of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events that could regulate cofactor assembly/disassembly and subsequent transactivation of target gene promoters. Using ChIP in mouse adrenocortical Y1 cells, our lab demonstrated that Sf1 is actively recruited to the promoters of a variety of steroidogenic enzyme genes after ACTH stimulation (71). Moreover, Sf1 exhibited a cyclical occupancy on the Mc2r gene promoter that was coincident with phosphorylation of Sf1 and recruitment of coactivator proteins (71), supporting a dynamic model of ACTH-mediated phosphorylation of Sf1 that participates in the regulation of steroidogenesis (differentiation).

It has recently become apparent that Sf1 can be repressed and activated through a variety of mechanisms that might serve cell and/or gene-specific functions. For example, several lines of evidence have identified Sf1 as a SUMO target protein (72,73,74). Sf1 is SUMOylated at Lysine 194 (K194), which lies within a synergy control motif in the hinge region of Sf1. Mutation of the synergy control motif leads to an enhancement of synergistic transcription from a promoter containing multiple Sf1 sites (73). This result is further supported by evidence that mutations of SUMOylation sites enhance the transcriptional activity of Sf1 but do not affect the DNA binding affinity of Sf1. Therefore, the SUMOylation site of Sf1 functions as an intrinsic repression domain (72). Moreover, overexpression of SUMO-1 directs wild-type Sf1, but not SUMOylation-deficient Sf1 mutant, to nuclear speckles (72). These results demonstrate that SUMOylation is an important posttranslational modification that regulates the transcriptional activity of Sf1. Two E3 SUMO ligases, PIAS1 and PIAS3 (73), and the helicase ARIP4 (K. Morohashi, personal communication) have been found to interact with Sf1 and promote Sf1 SUMOylation. More recently, the DEAD-box RNA helicase DP103 (Dxd20/Gemin-3) has been found to promote PIAS-dependent SUMOylation and intranuclear relocalization of Sf1 (74). These studies provide evidence that helicases are directly coupled to Sf1 transcriptional repression by protein SUMOylation.

Although the context in which these modifications participate in the regulation of Sf1 remains unclear, a few recent observations provide the groundwork for future studies along these lines. The Bakke laboratory (75) has recently revealed that in the highly proliferative Y1 adrenocortical cell, CDK7 as opposed to Erk1 is the primary kinase responsible for phosphorylation of Sf1 serine 203. Whether such phosphorylation serves an in vivo function to uniquely engage Sf1 in proliferative (as opposed to differentiation) programs is unknown. Moreover, recent findings from others and from our lab in collaboration with the laboratory of Jorge Iniguez indicate that SUMOylation of Sf1 K194 serves to both inhibit phosphorylation of Sf1 by CDK7 and prevent occupancy of Sf1 on a variety of steroidogenic promoters (76,77). The data support a general model in which SUMOylation participates in transcriptional repression in part by preventing additional activating posttranslational modifications of nuclear receptors. Similarly, the Sewer laboratory (78,79) has reported that, after ACTH stimulation, endogenous adrenocortical sphingolipids in the Sf1 binding pocket are repressive and displaced by activating phospholipids [as characterized by the West, Xu, and Ingraham labs (80,81,82)]. Together these results indicate that posttranslational modifications and ligand availability may play coordinating roles in Sf1 activation. Because CDK7 is well-known to be activated only in the context of cell cycle activation and proliferation is restricted to the subcapsular cortex, a critical issue to resolve is the physiological context in which these modifications activate Sf1 in proliferating vs. differentiated cells of the intact adrenal cortex. The first clue to this riddle came in the form of a paradox.

VIII. Regulation of Sf1-Dependent Gene Expression in the Subcapsular Cortex by Endocrine and Paracrine Signaling

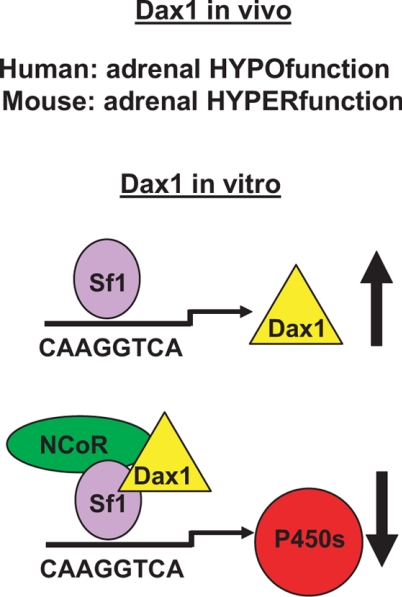

A. Sf1 and Dax1 interactions

DAX1 (NR0B1; dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia congenita critical region, on chromosome X, gene 1) was initially cloned as the gene responsible for X-linked congenital adrenal hypoplasia (83,84). Homozygous mutations in SF1 were later found in patients with a similar congenital adrenal aplasia/hypoplasia (85,86,87), suggesting a genetic or molecular interaction between these two atypical nuclear receptors. Consistent with this prediction, the Dax1 gene was determined to be a bona fide Sf1 target gene by multiple laboratories. However, the gene product of Dax1 was surprisingly found to serve as a repressor of Sf1-dependent transactivation (88). How such a repressive function could be reconciled with the phenotype of patients with mutations in DAX1 that partially phenocopied patients with SF1 mutations was unclear (Fig. 3). We hoped to gain insight into these potentially mutually exclusive observations by comparative studies of Sf1 haploinsufficient mice and combined Sf1 haploinsufficient/Dax1 null mice.

Figure 3.

Role of Dax1 in adrenal gland physiology. Model of Sf1- and Dax1-mediated transcription.

Although homozygous loss of the Sf1 gene in mice results in perinatal death of mice due to complications arising from adrenal aplasia, Sf1 heterozygous mice are viable with small adrenal glands (89,90). Using the paradigm of compensatory adrenal growth after unilateral adrenalectomy, Felix Beuschlein et al. (38) in our lab determined that Sf1+/− mice are not able to mount a compensatory proliferative response in the subcapsular cortex. Consistent with this result, mice engineered to express multiple copies of Sf1 in the adrenal cortex have recently been shown to exhibit pronounced subcapsular proliferation (91). Together, these studies provide evidence that Sf1 dosage is critical to the proliferative capacity of subcapsular cells and ultimately provide insight into the interactions of Sf1 and other transcription factors in these cells.

The Sf1 target genes Pbx1 and Dax1 provide examples of how Sf1 serves to regulate both a transcriptional activator and a repressor within the same cellular compartment. Studies in the Beuschlein group (92) demonstrated that Pbx1 is a direct target of Sf1, that Pbx1 expression was reduced 50% in the Sf1 haploinsufficient mice, and that Pbx1+/− mice phenocopied the subcapsular defect in Sf1 haploinsufficient mice after unilateral adrenalectomy, suggesting that Pbx1 is a downstream mediator of Sf1-dependent proliferation of subcapsular cells. Dax1, however, created a unique challenge. If Dax1 serves a primary role to inhibit Sf1-mediated transcription, loss of Dax1 would be expected to compensate for Sf1+/− haploinsufficiency. Alternatively, if Dax1 serves as a mediator of Sf1-dependent adrenal growth, we would expect either no change or a more severe adrenal hypoplasia. We examined these alternate hypotheses using Dax1 null mice generated in the laboratory of Larry Jameson. Surprisingly, Dax1 deficiency in mice did not appear to phenocopy the X-linked congenital adrenal hypoplasia seen in patients with a DAX1 mutation, but instead the combined Sf1+/−/Dax1−/Y mice almost completely rescued the hypoplasia and reduced steroidogenesis observed in Sf1+/− mice (93).

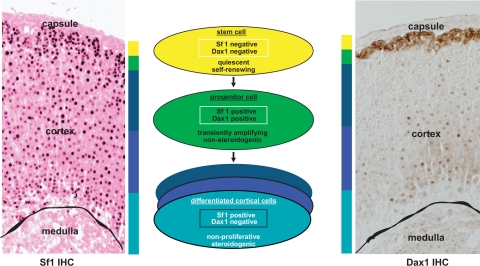

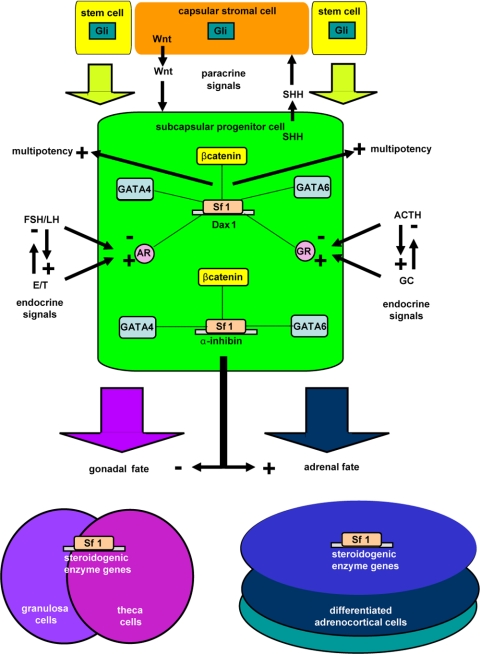

Several recent findings have provided insights to help explain these apparent discrepant observations. First, although Dax1 is expressed in the fetal zone of the adrenal, as the definitive zone emerges, expression becomes restricted to the subcapsular cortex. Sf1 would only be predicted to regulate Dax1 gene expression in this cell population. Secondly, we have recently observed that whereas the early enhanced differentiation in the adrenal glands of Dax1−/Y mice is coincident with early enhanced growth, the aging organ does not sustain homeostatic proliferation and ultimately develops biochemical adrenal failure with histological adrenal cytomegaly (our unpublished observation). The above data, together with the burgeoning role of Dax1 as a mediator of mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency (94), have led us to begin examining the paracrine and endocrine signals that regulate homeostatic proliferation and differentiation of adrenocortical subcapsular cells with a particular interest in Sf1 and the restricted expression of Dax1. The unique expression pattern of Sf1 and Dax1 in capsular (Sf1 negative, Dax1 negative), subcapsular (Sf1 positive, Dax1 positive), and mature steroidogenic (Sf1 positive, Dax1 negative) cortical cells predicts that binary decisions participate in paracrine and endocrine regulation of lineage relationships in these cellular populations (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Model of hierarchical organization of adrenocortical cells. Left, Immunohistochemistry (IHC) with anti-Sf1 reveals cortical staining. Middle, Model of Sf1 and Dax1 expression in stem/progenitor/differentiated adrenal cortex cells. Right, Immunohistochemistry with anti-Dax1 reveals membranous subcapsular expression and nuclear intracortical expression.

B. Endocrine signaling

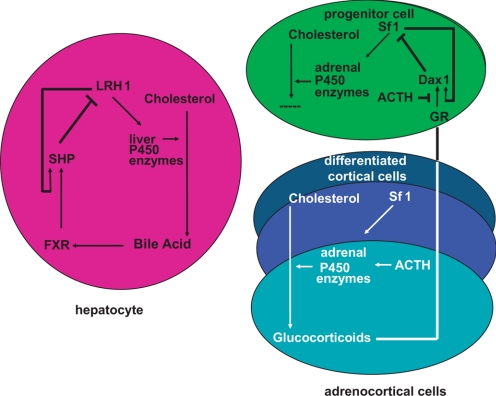

The structural and biochemical regulation of a nuclear receptor can often provide insight into the mechanism of action of a related gene family member. The phylogenetic relationship of the NR0B factors, DAX1 and small heterodimer partner (SHP), and of the NR5A factors, SF1 and liver receptor homolog (LRH), has provided a number of clues to the regulatory circuits controlling SF1 and DAX1 action in the adrenal cortex. The metabolism of cholesterol in the adrenal cortex parallels the metabolism of cholesterol in the liver. Both require the P450 enzymes for the conversion of cholesterol into its end products as well as transcription factors that regulate expression of these enzymes (31). Pioneering work of the Mangelsdorf lab (95) defined an intracellular biochemical feedback loop in the hepatocyte that regulates the synthesis of bile acid through the coordinated expression of LRH and SHP. LRH-1 was shown to regulate expression of CYP7A1, the rate-limiting P450 enzyme for bile acid production (96,97). LRH-1 also induces expression of a transcriptional repressor, SHP (98,99,100), which is analogous to the SF1-dependent regulation of DAX1 expression. The observations that 1) bile acid production in the liver was found to be accompanied by an increase in SHP expression, and 2) bile acids are activating ligands for the farnesoid X receptor, led to the discovery that farnesoid X receptor binds to the promoter for the SHP gene and synergizes with LRH-1 to activate SHP transcription. The increase in SHP levels results in SHP-mediated repression of LRH-1-dependent transcription of CYP7A1 and provides a biochemical basis of feedback control of bile acid synthesis (Fig. 5) (95).

Figure 5.

Comparative paradigm of nuclear receptor-mediated transcriptional feedback loop. The intracellular feedback regulation of adrenocortical steroid production parallels the regulation of bile acid synthesis in the liver.

These parallels suggested to us that similar mechanisms might participate in cholesterol metabolism in the adrenal cortex. However, if glucocorticoids inhibited adrenocortical steroidogenesis through a synergistic glucocorticoid receptor (GR)/Sf1-dependent activation of Dax1 transcription in adrenocortical cells, it seemed likely that such an intraadrenal system was a vestigial regulatory network in the presence of the robust hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis that is defined by endocrine-regulated long feed-forward and long feedback control. We ultimately defined an intraadrenal regulatory loop whereby glucocorticoid-bound GR synergistically activated Sf1-dependent Dax1 transcription (101). Moreover, quantitative ChIP analysis in synchronized cells allowed us to observe that: 1) Sf1 was bound constitutively to the Dax1 promoter at baseline; and 2) ACTH induced the clearance of both GR and Sf1 from the Dax1 promoter, resulting in transcriptional silencing of the Dax1 gene (101). This finding was in direct contrast to the near universal robust Sf1 recruitment and gene activation of other Sf1 target genes after ACTH treatment (101). Moreover, it held a critical clue to the Dax1 riddle. Because Dax1 is primarily expressed in the subcapsular region of the adrenal cortex coincident with the location of proliferating undifferentiated progenitor cells, we proposed a model whereby the differentiated cortical cell generates glucocorticoids that provide an endocrine signal (via centrifugal adrenal blood flow) to the undifferentiated progenitor cells to activate Dax1, which in turn inhibits Sf1-mediated differentiation (steroidogenesis). ACTH stimulation inactivates Dax1 and initiates steroidogenesis (Fig. 5). Because the presentation of adrenal failure in patients with DAX1 mutations is stochastic (even within the same kindred) (84,94,102), we would predict that such adrenal failure results from intrinsic differences in progenitor cell reserve. Loss of subcapsular cells would be reflected in premature differentiation at the expense of depletion of the progenitor pool. Indeed, a number of reports document persistent postnatal presence of 11-deoxycoritsol and testosterone in patients with X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita before the development of failure (103,104), consistent with this hypothesis.

However, the broad subcapsular expression of Dax1 in the mouse is not consistent with a solitary role of Dax1 in such an undifferentiated progenitor cell. Instead, two possibilities seem likely. Dax1, akin to Pref-1, is expressed in multiple types of granulosa cells (aldosterone synthase positive and aldosterone synthase negative), implying that Dax1 has roles in aldosterone synthase-positive glomerulosa cells that extend beyond its proposed role in the inhibition of differentiation of progenitor cells (aldosterone synthase-negative cells). Alternatively, the aldosterone synthase positive glomerulosa cell is the progenitor cell in the mouse, and Dax1 serves to inhibit the differentiation of a glomerulosa cell into ACTH-dependent fasciculata cells.

In addition to Pbx1 and Dax1 (105,106), Sf1 has been shown to interact with other transcription factors [i.e., cAMP-responsive element binding protein (107), androgen receptor (108), Sp1 (109), and β-catenin (101)] on a variety of gene promoters. Although these interactions (except Dax1) result in gene activation, the above data lend credence to the possibility that Sf1 might repress and Dax1 might activate transcription of certain genes in subcapsular cells. Indeed, in recent microarray analysis of Sf1-overexpressing cells, a number of transcripts proposed to be direct Sf1 targets were down-regulated (91). In collaboration with Bernard Schimmer (University of Toronto), we have shown that an Sf1/Sp1 interaction represses transcription of the type 4 adenylate cyclase, Adcy4 (110). Moreover, the human DAX1 gene generates an alternate transcript that lacks the repressive domain and therefore acts as a transcriptional activator (111). Our recent collaborative work with Ronald Koenig’s laboratory confirms that mouse Dax1 can function as a bona fide coactivator of Nr5a-dependent transcription at high doses in both adrenocortical cells and mouse embryonic stem cells (220). Although a better understanding of the cellular context of these interactions is required, these data may provide an additional layer of complexity to the regulation of Sf1-dependent transcription pertinent to organ homeostasis.

C. Paracrine signaling

A network of highly conserved developmental signaling pathways often orchestrates complex developmental events during embryogenesis as well as homeostatic events of adult organ system maintenance. Defects in TGFβ, hedgehog (Hh), Notch, and wingless-type MMTV integration site (Wnt) signaling pathways have been found to participate in the etiology of both developmental abnormalities and cancer (112). To explore the importance of such pathways in the adrenal cortex, we focused our efforts on Wnt and TGFβ signaling pathways in adrenocortical homeostasis.

1. Wnt signaling pathway.

Wnt signaling is categorized into two distinct intracellular pathways with different molecular mediators and cellular consequences: canonical Wnt signaling and noncanonical/planar-cell polarity pathway. Transcriptional activation after canonical pathway stimulation is mediated through the stabilization of the effector protein β-catenin, after the binding of a Wnt ligand to its respective Frizzled (Fzd) receptor. In the absence of Wnt ligands, the pool of β-catenin is sequestered to the cellular membrane/cell adherence junctions, and a low cytoplasmic concentration is maintained by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis through a degradation complex consisting of Axin/adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)/glycogen synthase kinase 3 β. Upon Wnt ligand binding, disruption of the degradation complex permits cytoplasmic and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. Inside the nucleus, β-catenin interacts with members of the lymphoid enhancer-binding factor/T cell factor (Tcf) family of transcription factors to activate expression of target genes. Through transcription of target genes, the canonical Wnt pathway regulates processes such as proliferation, specification of cell fate, stem cell maintenance, and differentiation. Recent studies have suggested that a number of Wnt ligands and Fzd receptors play roles in adrenocortical development and/or homeostasis. For example, loss of Wnt 4 (primarily a noncanonical Wnt) results in the aberrant migration of adrenocortical cells into the developing gonad (113). Due to the combinatorial complexity of the Wnt signaling pathway (19 ligands and 10 receptors in mouse), we focused our efforts on the role of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (i.e., β-catenin-dependent transcription) in adrenocortical development and maintenance.

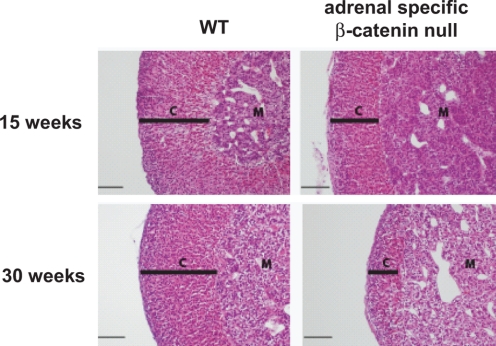

Initially, we examined the temporal and spatial expression of the β-catenin protein as well as the localization of the active β-catenin signaling using the Wnt-Gal transgenic reporter mouse line that expresses β-galactosidase only in cells with active β-catenin signaling. At embryonic day (E) 12.5, although β-catenin protein was expressed (as determined by immunohistochemistry) in nearly all cells of the newly formed fetal adrenal cortex, active signaling (as determined by the presence of lacZ) was absent (114). However, as the capsule of the adrenal formed, β-catenin protein and active β-catenin signaling became strictly localized to cells under the newly emerging adrenal capsule, the proposed location of the adrenocortical somatic progenitor cells. To further examine the role of β-catenin in the adrenal cortex, in collaboration with the laboratory of Keith Parker, we used the Cre-loxP conditional knockout strategy to inactivate β-catenin alleles in the adrenal cortex. In the study, we mated Ctnnb1tm2kem transgenic mice carrying floxed β-catenin alleles to two lines of transgenic mice, one carrying a low-expressing Sf1-Cre transgene (Sf1-Crelow) and one carrying a high-expressing Sf1-Cre transgene (Sf1-Crehigh) (114). With near complete excision of β-catenin alleles in the adrenocortical cells using the Sf1-Crehigh mice, we observed the absence of the adrenal gland at postnatal day zero. When examining the developing adrenal glands of these mice, we observed a marked failure of cellular proliferation under the developing capsule between E12.5 and E14.5 (114). With excision of β-catenin in only 50% of adrenocortical cells in the Sf1-Crelow mice, we observed normal development of the gland at birth followed by progressive cortical thinning (Fig. 6) and decreased steroidogenic capacity (as determined by steroidogenic enzyme mRNA levels) over a timeframe of 30 wk, presumably due to loss of proliferating subcapsular cells (114). Building upon this observation that canonical Wnt signaling is essential for the homeostatic maintenance of the adult gland, current efforts are focused on the isolation of Wnt-responsive subcapsular cells via flow cytometry and identification by cDNA expression arrays of downstream target genes that may contribute to subcapsular cell fate. Identifying the roles of specific Wnt ligands and their respective Fzd receptors responsible for canonical signaling in the adrenal cortex together with an exploration of the roles of noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway in the adrenal cortex are logical areas of future investigation.

Figure 6.

Role of canonical Wnt signaling in adrenocortical homeostasis. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of conditional β-catenin knockout adrenals. Progressive depletion in the adrenal cortex is evident at 30 wk of age. [Reproduced with permission of Development (114)].

2. TGFβ signaling and inhibin.

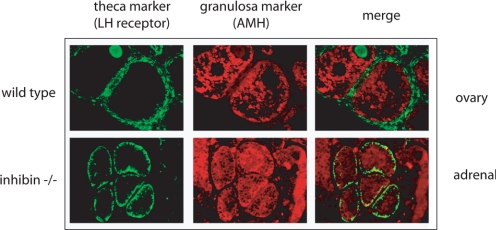

The shared origin of the adrenal and gonad, the existence of pluripotent stem/progenitor cells for steroidogenic lineage in both tissues, and the presence of 1) ACTH-driven adrenal rests in the gonads of patients with long-standing untreated congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and 2) gonadotropin-driven thecal metaplasia in the adrenal cortex of estrogen-naive postmenopausal women predict a mechanism that guides the stem/progenitor cells of the each tissue (gonad vs. adrenal) to differentiate selectively in response only to the appropriate peptide hormone and not the other (FSH/LH vs. ACTH). The adrenocortical defects in inhibin-α null mice provided a unique opportunity to evaluate this hypothesis.

The TGFβ superfamily encompasses approximately 30 growth and differentiation ligands that include TGFβs, activins, inhibins, and bone morphogenetic proteins, many of which have been shown to play essential roles in stem cell fate commitment (115). This highly conserved signaling pathway commences with the binding of a ligand to a TGFβ type II receptor. The type II receptor is a serine/threonine receptor kinase, which in turn phosphorylates the type I receptor. The type I receptor is then able to phosphorylate and activate the receptor-dependent Smad proteins upon which these mediators translocate to the nucleus, recruit other transcription factors to activate, and/or antagonize the expression of target genes (Fig. 7) (116).

Figure 7.

The role of TGFβ signaling in adrenal vs. gonadal fate determination. Histological analysis of adrenal cortex revealing follicular-like structures in the adrenal cortex of inhibin null mice (red, granulosa cell staining for anti-mullerian hormone; green, theca cell staining for LH receptor). [Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2006, The Endocrine Society (119)].

Our interest in this signaling pathway began with studies describing gonadal tumors and subsequent adrenocortical blastomas after gonadectomy in both inhibinα null mice (Inha−/−) (117) and in mice with overexpression of the simian virus 40 T-antigen gene under control of the inhibinα promoter (221). In the collaboration with the laboratory of John Nilson, we demonstrated that gonadectomy of Inha−/− mice (kindly provided by Marty Matzuk) resulted in the formation of large tumors in the adrenal glands that we ultimately showed were dependent upon chronically high levels of LH (118). Further analysis revealed that the tumors were actually newly differentiated ovarian tissue that was formed from LH-stimulated undifferentiated adrenal subcapsular progenitor cells. Two events were found to be critical for this ultimate manifestation of ovarian fate in the adrenal cortex of these mice. First, it appears that the adrenocortical subcapsular cells of wild-type adrenal cortex have the innate capacity to respond to gonadal-specific differentiation signals (LH and FSH) consistent with the singular origin of the adrenal cortex and gonad—the adrenogonadal primordium. Specifically, LH induces expression of gonadal-restricted Gata4 in the subcapsular cells of the adrenal with concomitant loss of adrenal-restricted Gata6. LH and Gata4 are both necessary (but not sufficient) to drive adrenocortical progenitor cells to ovarian fate. Indeed, these adrenal tumors display a global reprogramming of their cellular identity, manifesting in expression of genes normally restricted to theca and granulosa cells of the ovary (119). Second, we were able to show genetically that it is the specific loss of inhibin-α and consequent unopposed Smad3 activation that leads to expansion of these Gata4-positive cells and ultimate generation of ovarian tissue in the adrenal cortex (119). Consistent with this paradigm, the LH-driven gonadal-programmed subcapsular cells in wild-type mice are prevented from expanding and forming true ovarian tissue through the actions of inhibin (119). When Smad3 is genetically ablated in the context of compound inhibin-α-null/Smad3-null mice, while Gata4-positive cells still reside in the subcapsular progenitor cell region (in response to LH), no expansion occurs, indicating the importance of inhibin-α as a gatekeeper of adrenogonadal stem/progenitor cell fate (120).

It remains equally plausible that cells of the developing gonadal primordia are mislocalized in the adrenal cortex and hence respond normally to gonadotropins, albeit in an ectopic location. Indeed, in a recent paper by the Swain group (113), such a model has been proposed for the expression of adrenal-specific genes in the gonadal primordia of Wnt4 knockout mice. We would posit that the activation of gonadal genes in the subcapsular cells of nongenetically modified mice in multiple strains of mice argues against mislocalization and rather argues in favor of bona fide multipotency.

The dependence of adrenal-specific ovarian differentiation upon Smad3 indicated that inhibin-α loss allowed unopposed receptor activation by a stimulatory ligand of the TGFβ superfamily, namely a TGFβ or an activin, both of which signal primarily through Smad2 and-3. Inhibin is an atypical member of the TGFβ family of signaling ligands and is classically understood to function via competitive antagonism of activin ligand binding. However, because activin is not expressed in the adrenal cortex before tumor formation and is not induced by elevated LH levels, we are currently examining the hypothesis that adrenocortical tumorigenesis in Inha−/− mice is explained by a novel interaction between inhibin-α and the TGFβ2 ligand. Taken together, these observations provide rationale for the fetal adrenal production of massive amounts of inhibin-α. We predict that this is to ensure the specification of adrenal fate by preventing human chorionic gonadotropin-mediated ovarian differentiation of the gland.

IX. Adrenocortical Carcinomas in the Context of Cancer Stem Cells

Benign adrenal tumors are relatively common, with occurrences of 3–7% of the population. Malignant adrenal tumors or adrenocortical carcinomas (ACC) are relatively rare, with the incidence rate of approximately two cases per million people per year and representing only 0.2% of cancer deaths in the United States. Although rare, this form of cancer is highly malignant and presents with extremely poor prognosis as a consequence of metastasis or local invasion at the time of diagnosis (121,122,123). The recent findings that most ACC are monoclonal in origin (123) suggest that an initiating mutation within a single dividing cell might give rise to adrenal cancer (123). These suggestions, together with our observations that adrenocortical subcapsular somatic progenitor cells alone have a robust proliferation potential, support a stem and/or progenitor origin of adrenal cancer.

The cancer stem cell theory hypothesizes that a distinct subpopulation of cancer cells maintains the stem cell potential (124). These cells, termed “cancer stem cells,” are uniquely endowed with the ability to self-renew and differentiate into multiple different cell types within a cancer, analogous to normal tissue stem cells. Cancer stem cells have been identified in blood, breast, brain, colon, and pancreatic cancers, and the list is expanding (124). Furthermore, evidence is mounting that aberrant epigenetic reprogramming of stem/progenitor cells is another level of dysregulation contributing to the pathogenesis in human cancers (125). Although cancer stem cells are predicted to be the only cells within a tumor that can give rise to new tumor cells, they are also predicted to be the only cells that are not responsive to standard chemotherapeutic protocols. This theory challenges current dogma of cancer therapeutics that all tumor cells possess equal malignant potential. Thus, drug discovery is challenged to shift treatment paradigms toward targeting this tumorigenic subpopulation of cancer stem cells for potential cure.

Armed with emerging data on adrenocortical stem/progenitor cells and our data describing the important molecular mechanisms regulating adrenocortical organ maintenance, we began to examine the biology of genes known to be mutated in hereditary ACC syndromes such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), familial adenomatous polyposis, and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Because these genes are known to play various roles in the regulation of somatic stem cell fate in a variety of systems (122,123), we hoped to gain insights into both the normal and pathological roles of these factors in adrenocortical stem and/or progenitor cells.

A. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and IGF-II

BWS is a rare embryonic overgrowth disorder that manifests with macrosomia, macroglossia, abdominal wall defects, renal abnormalities, cleft palate, and an increase in a variety of childhood cancers, including ACC. It has a frequency in the United States of about 1 in 14,000, and about 10–15% of cases are familial (126). Approximately 85% of BWS patients have causative defects in the genomic imprinting of five genes located in two chromosomal clusters within the 11p15.5 region (127). The two genes comprising the distal cluster are the IGF-II and H19 (an untranslated mRNA) genes. The proximal cluster includes the CDKN1C (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57kip2), KCNQ1 (potassium voltage-gated channel) and KCNQ1OT1 (KCNQ1 overlapping transcript) genes. Several studies have demonstrated the association of IGF-II expression with malignant vs. benign adrenal tumors (128,129), and DNA microarray expression analyses in the laboratory of our collaborator Tom Giordano implicate IGF-II as the single highest expressed gene in the majority of sporadic ACC (130). Moreover, in these samples, H19 and p57 are characteristically down-regulated, consistent with a somatic epigenetic defect. Mouse models have also confirmed that overexpression of the IGF-II gene results in a BWS-like syndrome (131) that includes adrenal hyperplasias and cytomegaly (132).

IGF-II is often seen as a key growth factor employed during early fetal development, whereas postnatal IGF-I expression is used for maintaining normal growth as a downstream effector of growth hormone stimulation. Both IGF-II and IGF-I bind to the receptor tyrosine kinase, IGF-1R (IGF-I receptor) (and the insulin receptor to a lesser degree) to exert their physiological effects. Extracellular ligand binding causes IGF-1R autophosphorylation of its intracellular domain. Subsequently, the MAPK and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways are activated to induce expression of numerous genes that regulate progrowth/survival pathways in the cell (133). Because in the adrenal gland IGF-II is uniquely expressed in the capsule (http://www.GenePaint.org; ID MH523) (134) and has recently been shown to be a critical mediator of the embryonic and tissue stem/progenitor cell niche (135), the prediction that abnormal imprinting of the IGF-II locus in the capsule/subcapsular unit serves as an initiator of the disease becomes a testable hypothesis and the IGF-II pathway a possible target for therapeutic intervention in ACC. Supporting this hypothesis is the finding that the transcription factor Zac1, which regulates the IGF-II network of imprinted genes in tissue stem cells (223), is the most down-regulated gene in pediatric adrenal cancer (222). Extending similar findings of others (136), we have shown that antagonizing this pathway with two different pharmacological agents that target IGF-IR leads to a potent inhibition of growth of ACC cells in culture and in human ACC xenografts. We also demonstrated that the addition of mitotane (currently the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved therapy for ACC), increased the cytostatic effects of either compound on human ACC xenografts in mice (137). The above data support the testable hypothesis that aberrant epigenetic reprogramming of 11p15.5 and potentially other loci in stem/progenitor cells participates in the etiology of a subset of cancers including ACC. These studies have resulted in both a phase I trial of IGF-IR inhibition in refractory ACC patients and a current multi-institutional phase II trial using this targeted approach as front-line therapy in stage 4 ACC.

B. Familial adenomatous polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis is a hereditary disorder in which patients typically present with innumerable colonic polyps and ultimate colonic cancer. This disorder is characterized by mutations in the APC gene on chromosome 5q21-q22 that result in a truncated and/or nonfunctional APC protein (138,139). These patients also have increased risk of other cancers in the extracolonic organs, including the pancreas, thyroid, and adrenal glands (140,141,142,143).

The molecular mechanism of tumorigenesis resulting from APC gene mutations has been widely characterized (138,139,143,144). The product of the APC gene functions as a tumor suppressor mainly through regulation of β-catenin protein stability and hence β-catenin-mediated transcription. Inactivating mutations of APC result in up-regulation of the β-catenin target genes, subsequent unabated growth, and ultimate tumor formation. Although recent evidence suggests additional functions of APC in cell adhesion, cell polarity and migration, chromosome segregation, and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, this review addresses the role of APC only as a member of the β-catenin degradation complex (144). Predicated on the known role of APC in the regulation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in tissue development and homeostasis, our lab and others began analyzing the status of β-catenin in sporadic adrenocortical tumors. In earlier work, the Bertherat laboratory (145) had observed an increase in the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of β-catenin in sporadic ACC. In collaboration with the Giordano laboratory, we began screening a panel of ACC samples for stabilization of β-catenin and observed a subset of carcinoma samples with strong nuclear accumulation of β-catenin indicative of active signaling. Utilizing expression array profiling, we compared carcinomas with strong nuclear β-catenin staining to carcinomas with only membranous β-catenin staining. In the analysis, we observed marked up-regulation of classical β-catenin-mediated transcription targets, but only in ACC samples did we observe increased nuclear β-catenin. Such results support a potential role of active β-catenin signaling in a subset of patients with ACC.

To further test a hypothesis that active β-catenin signaling may initiate adrenocortical carcinogenesis through aberrant activation in adrenocortical subcapsular cells, we are using a conditional knockout approach to delete the Apc gene in the mouse adrenal cortex. We hypothesize that canonical Wnt signaling regulates the proliferation and the undifferentiated state of adrenocortical stem/progenitor cells. With constitutive activation of the canonical Wnt pathway, expansion of this population is predicted to result in ultimate tumor formation.

The additional mutations and signaling pathways contributing to these phenotypes are areas of active investigation. IGF and Wnt ligands are two such signals generated in the adrenal capsule that have been shown to be essential in the regulation of stem cell niches and/or the communication with neighboring stem/progenitor cells in multiple organ systems. Specifically, IGF is a critical mediator of the embryonic and tissue stem/progenitor cell niche, whereas Wnt signaling is essential for stem/progenitor cell self-renewal in multiple systems (135,146). Together with our above studies utilizing IGF-1R inhibition in ACC treatment, recent preclinical studies by the laboratory of Enzo Lalli using β-catenin antagonists (224) hold promise for new therapies for ACC that target defective signaling pathways in adrenocortical stem/progenitor cells that are predicted to participate in the initiation of adrenal cancer.

C. Li-Fraumeni syndrome

This familial syndrome arises from mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene and is associated with soft tissue sarcomas, osteosarcomas, as well as breast, brain, and adrenal cancer (147). p53 is often regarded as the “guardian of the genome” because it is a critical transcriptional mediator of cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and programmed cell death in response to DNA damage (148). Loss of p53 function confers impaired apoptosis, genomic instability, and loss of cell cycle control. Indeed, loss of p53 function is the most common mutation in human cancer, accounting for nearly half of all sporadic cancers (148). Recent work suggests that p53 is an important regulator of differentiation of both embryonic stem cells and adult tissue stem cells, where it functions as a rheostat that balances the induction of differentiation vs. apoptosis (149,150). Our recent work examining p53 in adrenocortical cancer is discussed below in the context of the roles of telomerase in adrenocortical homeostasis and cancer.

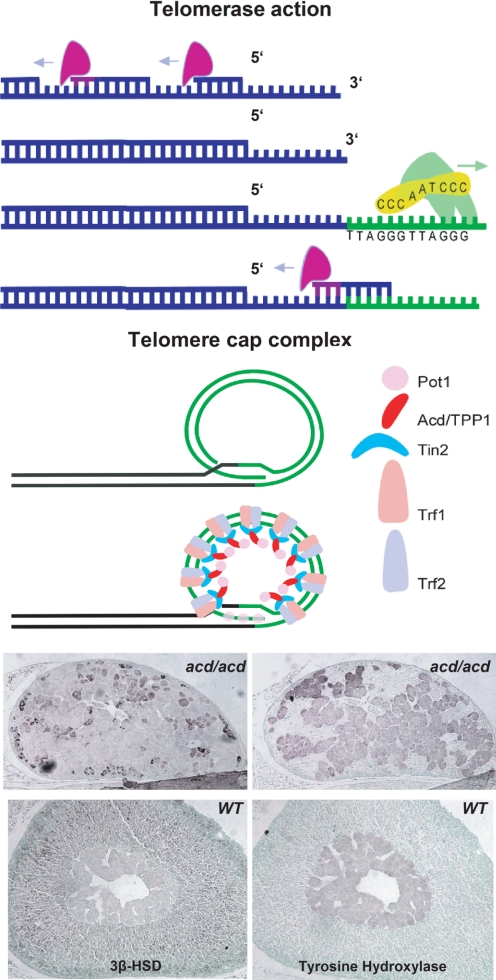

D. Telomeres, telomerase, stem cells, and cancer

The phenotype of adrenocortical dysplasia (Acd) mice consists of large cells with nuclear pleomorphy, nucleomegaly, and nuclear inclusion bodies, reminiscent of the adrenocortical histology of the cytomegalic form of congenital adrenal hypoplasia in patients with DAX1 mutations or IMAGe syndrome (151). As detailed below, the Acd phenotype in mice is caused by telomere dysfunction and subsequent senescence (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Importance of telomere stability in adrenal gland development. Top, Model of telomerase-mediated telomere elongation. Middle, Model of telomere cap complex. Bottom, Histological analysis of Acd-deficient mouse adrenals. Immunohistochemistry using anti-3β-HSD and antityrosine hydroxylase reveals aberrant adrenal development.HSD, Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. [The bottom panel is reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press (151)].

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein that adds telomeric repeats to the 3′ ends of chromosomes to prevent the loss of genetic material over consecutive cell divisions due to the inability of the DNA replication machinery to copy the ends of chromosomes fully (152). There is no active telomerase activity in resting somatic human cells. It can only be detected in rapidly dividing and renewing tissues such as germ cells, basal layers of the skin, and the hematopoietic system. Critically short or dysfunctional telomeres induce a p53-sensitive pathway to senescence or apoptosis, which removes these cells from the proliferating cell pool to prevent the accumulation of genomic aberrations (153). Dysfunctional telomeres can be detected and eventually joined by the DNA repair machinery, leading to dicentric chromosomes that can lead to amplification and loss of genetic material through breakage-fusion-bridge cycles. Telomerase activity, although usually confined to stem cell compartments, can be reactivated in neoplastic cells to prevent the progressive shortening of chromosomes over time and inhibit the subsequent induction of apoptosis or senescence (153). In the human adrenal cortex, the RNA component of telomerase is spatially exclusively expressed in the proliferative subcapsular cortex. The requirement of telomerase activity in stem cell compartments has been shown in human embryonic stem cells and can also be deduced from the progressive failure of bone marrow stem cells in patients with dyskeratosis congenita who harbor germline mutations in the telomerase gene (154).

Recent research has focused on the role of a six-protein complex termed shelterin that protects the telomere from being recognized as damaged DNA and prevents the potentially deleterious processing by the DNA repair machinery. Cloned by our laboratory, the gene responsible for adrenocortical dysplasia is the murine homolog of TPP1, a component of the shelterin complex (151). One can speculate that human syndromes accompanied by cytomegalic adrenocortical hypoplasia may represent the same endpoint of different forms of adrenocortical stem cell failure.

Multiple chromosomal fusions are observed in analyses of metaphases from acd mouse embryonic fibroblasts (225). These telomere dysfunction-derived fusions can potentially serve as starting points for breakage-fusion- bridge cycles and lead to a further shuffling of the genome generating oncogenic genomic losses and gains. To further examine the role of telomere decapping in the observed adrenal failure in acd mice and to analyze the impact of telomere dysfunction-derived chromosomal abnormalities in carcinogenesis, acd mice are being crossed to a p53-deficient background. This approach prevents the induction of telomere dysfunction-induced senescence through p53-sensitive pathways and, hence, leads to the accumulation of potential oncogenic mutations and finally a procancer genome. Such studies will help determine whether telomere dysfunction together with other deleterious events in the stem/progenitor cells (i.e., perturbations of the p53 pathway, defective IGF imprinting, gain-of-function β-catenin) serve as the pathogenetic basis of human adrenocortical carcinogenesis.

A two-step model for the role of telomere dysfunction has been proposed in human carcinogenesis: 1) an early event that leads to shuffling of the genome and the acquisition of oncogenic mutations ultimately leading to a procancer genome; and 2) a late event in which telomeres are maintained either by telomerase activity or alternative mechanisms of telomere maintenance. The latter is a rather ill-defined mechanism of telomere maintenance that is independent of telomerase activity. Most likely this mechanism includes homologous recombinations between chromosomes. An increase in telomere length and the colocalization of telomere sequences with promyelocytic leukemia bodies have been described as surrogate parameters of alternative telomere maintenance. We recently studied a large cohort of benign and malignant ACC and showed that the vast majority of ACC employ active telomere maintenance mechanisms, predominantly telomerase, but to a lesser extent also alternative, telomerase- independent mechanisms (155). Together these findings highlight the importance of the telomere-telomerase function in adrenocortical physiology to ensure the genomic integrity necessary for organ replenishment from the stem/progenitor cell compartment. In the case of carcinogenesis, the work underscores 1) the role of telomere dysfunction in generating oncogenic genomic alterations, and 2) the role of telomerase in maintenance of a malignant phenotype.

X. Future Directions

A. Tissue-specific silencing of Sf1 gene expression

1. Methylation.

Early data supported a role of the Sf1 E-box in the proximal promoter in the “basal” expression of Sf1 in Sf1-expressing tissue (156,157). In adrenocortical cell lines, it was shown that upstream stimulatory factor (USF) 1 and USF2 could bind this site and facilitate transcriptional activation (158). The context in which such activation or repression of activation is important has been unclear until recently. Recent data by the Bakke group (159) reveal that methylation of CpG sites in the E-box-containing proximal promoter is responsible for promoter silencing and the resultant restricted expression pattern of Sf1. Sf1 is only expressed in tissues where the region is hypomethylated. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses revealed that USF2 and RNA polymerase II were only recruited to this DNA region when hypomethylated (159). Moreover, recent studies indicate that the ectopic expression of Sf1 in human endometriotic cells, but not normal endometrial cells, is due to abnormal hypomethylation of the proximal promoter (160). Lastly, forced overexpression of Sf1 in transgenic mice induces adrenocortical hyperplasia of the subcapsular region of the mouse adrenal cortex (91) and amplification of 9q34, and an increased copy number of the embedded Sf1 gene has been observed in a high percentage of pediatric ACC and adrenocortical cancer cell lines (161,162). Whether epigenetic methylation of the Sf1 gene serves to regulate Sf1 levels as a normal mechanism in organ maintenance of the capsular/subcapsular unit remains unclear.

2. POD1.

Although the steroidogenic adrenocortical cell is identified by expression of Sf1, the mesenchymal capsular cell is devoid of Sf1. In the proposed model (Fig. 9) whereby the capsule serves as the residence and niche, a small number of quiescent cortical stem cells (derived from the Sf1-expressing fetal zone cells) would be predicted to actively repress the expression of the Sf1 gene until the cells differentiate into Sf1-positive proliferating progenitor cells. Indeed, histological evidence indicates differentiation of Sf1-positive steroidogenic cells within areas of Sf1-negative spindle cell hyperplasia of the capsule that extends into the outer parenchyma of zG (163). A number of basic HLH transcriptional regulatory proteins have been identified that govern similar processes of cellular differentiation and fate determination in various tissues. Pod1/capsulin/Tcf21 belongs to a subfamily of basic HLH proteins that control mesodermal development (164,165). In the embryonic gonads, Pod1 is expressed in regions from which progenitor cells migrate into the gonads to generate several somatic lineages of the testes. Loss of Pod1 in the testis leads to enhanced expression of Sf1, subsequently resulting in premature commitment of progenitor cells to a steroidogenic lineage. In Pod1-deficient testes, the Leydig cell population expands coincident with an increase in Sf1 and Cyp11a1 (a downstream target of Sf1) expression. This is presumably associated with the concomitant loss of peritubular myoid cells and pericytes. Moreover, Sf1 expression is observed in the LacZ-expressing Pod1 null cells (LacZ knock-in), indicating that the loss of Pod1 induces the expression of Sf1 (166,167). Therefore, it is proposed that Pod1 represses Sf1 expression in a multipotent cell precursor, allowing the differentiation of several interstitial lineages, such as Leydig cells, peritubular myoid cells, and pericytes. Indeed, Pod1 has been shown to specifically inhibit the expression of Sf1 by antagonizing the activity of USF1 on the proximal E-box of the Sf1 promoter (167). Within the adrenal gland, Pod1 is uniquely expressed in the developing capsule of the E11.5 mouse cortex, consistent with its known expression in mesenchymal cells within the developing kidney and gonad (164,165,166,167).

Figure 9.

Cellular organization of the adrenal cortex. Left, Model of adrenocortical homeostatic growth maintenance (right, color key for model). Middle, Immunohistochemistry using anti-PCNA reveals subcapsular localization of proliferating adrenocortical cells.

It is important to relate these Pod1/Sf1 interactions in the maintenance of the adult gland to the development of the adrenal capsule. At E11.5–12.5, loose condensations of flattened cells appear over the surface of the mouse fetal adrenal cortex. As these cells coalesce to form the capsule (coincident with Pod1 expression), the adult cortex slowly emerges between the fetal cortex and capsule (9). The temporal appearance of these three structures (and ultimate disappearance of the fetal cortex at birth) leaves open three possibilities regarding the developmental origin and fate of capsular cells: 1) capsule is unrelated to cortical lineages and the fetal cortex gives rise to the adult cortex; 2) capsule gives rise to the adult cortex, and the fetal zone is an unrelated lineage; and 3) the fetal zone cells give rise to stem cells that assume residence within the capsule, and these cells give rise to the subsequent definitive cortex. The ultimate residence of adult cortical progenitor cells within or underneath the capsule is consistent with each model. Sf1 expression defines both fetal and adult cortical cells, but the transcriptional activation of Sf1 utilizes unique enhancers in each tissue (14). If the cortical stem cells within the capsule arise from the underlying fetal cortex, Pod1 (which acts at the proximal E-box of the common basal promoter) would serve to actively repress the fetal and/or definitive enhancer-mediated Sf1 expression in the capsule. Reactivation of an adult Sf1 enhancer would serve to form the underlying adult cortex. Regardless of the developmental origins of capsular lineages (stromal and adrenocortical stem cells), two possible nonmutually exclusive mechanisms seem likely for how adrenal capsular Pod1 regulates the maintenance of the adult subcapsular adrenal cortex: 1) Pod1 represses Sf1 expression in capsular stem cells (i.e., differentiation of Sf1-negative capsular cells is mediated by a down-regulation of Pod1); and/or 2) Pod1 maintains the integrity of the capsular niche cell (164,165).

An additional mechanism for how Sf1 expression is extinguished in the fetal zone (utilizing the fetal Sf1 enhancer) before being actively repressed in capsular stem cells rests on the ability of Dax1 to antagonize Sf1-mediated gene expression. Because Sf1 maintains its own expression in the fetal adrenal, Dax1 (a target gene of Sf1) might be predicted to initially down-regulate the expression of the Sf1 gene itself in a fetal zone cell as it establishes residence in the coalescing capsule. However, once the Sf1-negative cell is in capsular residence, it is difficult to envision how Dax1 would participate in the maintenance of this Sf1-negative state because Dax1 is not expressed in this cellular compartment.

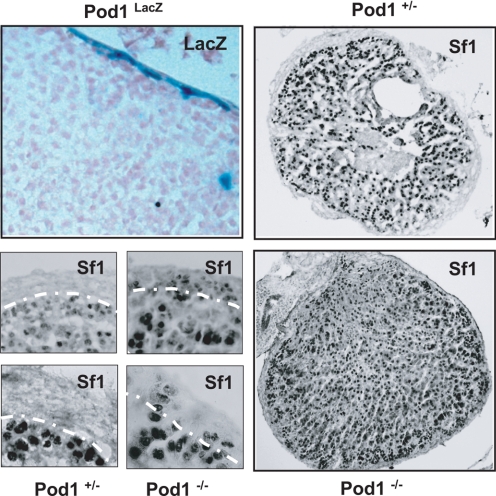

B. Pod1 null mice

The Pod1 locus was targeted by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells to generate a Pod1 null allele that expresses β-galactosidase or rtTA (tetracycline transactivator) under the regulation of the endogenous Pod1 promoter (168). We first examined LacZ expression in the adrenal glands of 4-month-old heterozygous Pod1/LacZ [LacZ knock-in (KI)] male mice and found robust LacZ expression restricted to the capsule as revealed by X-gal histochemistry. We then compared rtTA and Sf1 expression in E18.5 heterozygous Pod1 (rtTA KI) vs. Pod1 null (rtTA KI) mice. Immunohistochemistry confirmed mutually exclusive expression of rtTA (proxy for Pod1) in the capsule (VP16 epitope of rtTA) and Sf1 in the cortex in heterozygous Pod1 mice. However, in Pod1 null mice we now observe both rtTA expression in cortical cells and Sf1 expression in capsular cells. Together with an increased Sf1 mRNA in Pod1 null adrenals (1.64 ± 0.13-fold above Pod1+/− adrenals; P > 0.01), the data are consistent with the hypothesis that under normal circumstances Pod1 serves to inhibit Sf1 expression in a small subset of cells of the capsule (our unpublished observation, in collaboration with Sue Quaggin, University of Toronto) (Fig. 10). In our recent published expression data set of ACC tissue samples, we see down-regulation of 84 genes including POD1 at 6q23. POD1 is markedly down-regulated in ACC vs. ACA (Adrenocortical Adenoma) and normal adrenal tissue (219). Although these data do not prove that capsular Pod1-positive/Sf1-negative cells become the subcapsular Pod1-negative/Sf1 positive cortical cells or that capsular Pod1 has additional niche effects, the data provide a valuable tool that will allow us to examine the roles of the capsule as niche and residence of adrenocortical stem cells in more detail.

Figure 10.

Role of Pod1 in adrenocortical development. Top left, LacZ activity staining in Pod1-LacZ adrenals reveals preferential capsular staining. Bottom left, Comparative immunohistochemical analysis of heterozygous and homozygous Pod1 knockout adrenals. Staining reveals presence of Sf1-positive cells in the capsule of homozygous Pod1 knockout adrenals. Right, Low-power magnification of anti-Sf1 staining in Pod1 knockout adrenals reveals expansion of Sf1 positive cells in homozygous Pod1 knockout adrenals.

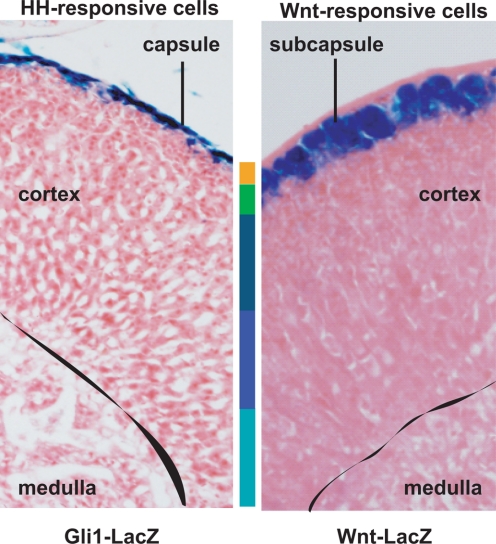

C. Hedgehog signaling

The Hh developmental signaling pathways are well-conserved and important in vertebrate development, such as foregut, neural tube, limbs, lungs, and skin (112,169). The Hh pathway has been implicated in the regulation of both embryonic and adult stem cell fate (112,170,171,172,173,174). Activating and inhibiting mutations of the Hh pathway members demonstrate their importance in cancers, including as pancreatic, basal cell, and medulloblastoma (174,175,176,177,178). The activation of the pathway occurs through binding of Hh morphogens [Sonic hedgehog (Shh), Indian hedgehog (Ihh), and Desert hedgehog (Dhh)] to the Patched-1 (Ptch1) receptor (112,169). In the absence of Hh ligands, Ptch inhibits downstream activation of the Smoothened receptor. The binding of Hh molecules to Ptch allows for activation of Smoothened and ultimate activation of the Gli transcription factors.

Recent studies indicate that Hh signaling is also a critical mediator of adrenogonadal development and growth maintenance. In the testis, the cell-restricted expression of Dhh in Sertoli cells and Ptch1 in fetal Leydig cells is consistent with the observations that Dhh is required for fetal Leydig cell formation and sex cord formation in mice (179,180,181,182). The decreased expression of Sf1 in the precursor Leydig cell population of Dhh null mice despite no change in the size of this population (182) suggests a defect in the lineage progression of the Sf1-positive precursors to bona fide Leydig cells. In the ovary, however, the dual (and potentially redundant) expression of both Dhh and Ihh in granulosa cells (with Ptch1 and Gli expressed in theca) (183) might explain the normal fertility of Dhh null mice (179). Nonetheless, loss-of function mutations in DHH resulting in human gonadal dysgenesis (184,185,186) indicate the clinical significance of these modeling studies.

Two clinical syndromes have provided insight into the importance of Shh in proper adrenocortical development. Adrenal hypoplasia/aplasia has been reported often in Pallister-Hall syndrome due to loss-of-function GLI3 mutations (187) and in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome due to cholesterol synthetic defects that result in altered Hh signaling (188,189). The resultant adrenal aplasia after the introduction of the Gli3 mutation in mice (190) supports such a role of Shh in adrenal development. The spatially restricted expression of Shh in the subcapsular adrenocortical cells that is temporally coincident with formation of the adrenal capsule (191) and the emergence of adrenocortical defects in Shh null mice precisely at E12.5 when the capsule is forming lends credence to a role of Shh in adrenocortical lineage progression dictated by capsule/subcapsule relationships (192). Indeed, the enriched expression of Gli1 in the adrenal capsule suggests a potential reciprocal relationship between these two compartments (our unpublished observation, in collaboration with Dr. A. Dlugosz, University of Michigan) (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.