Abstract

A prospective, open trial was conducted to evaluate the nutritional adequacy of a semi-elemental diet in 47 children with functional gastro-intestinal disorders. Nutritional adequacy was assessed based on growth relative to Euro-growth standards for body mass index (BMI)-for-age z-scores and evaluations of blood parameters. Twenty-five patients completed the study. In total, 533 l of “New-Alfare” was consumed during 775 trial-days. The mean intake per infant was 85.8 ± 26.8 kcal/kg/day or 122.5 ± 38.3 ml/kg/day. Weight and length evolution during the 4 weeks trial were within normal range. The mean BMI-for-age z-score (P < 0.05) and albumin concentration (P < 0.01) increased significantly after 4 weeks. Plasma threonine concentration decreased significantly (P = 0.01) and the tryptophan concentration increased (P = 0.06). No adverse events related to the study formula were reported. These results show that “New Alfaré” is safe and nutritionally adequate for pediatric patients with gastro-intestinal disease.

Keywords: Infant formula, Amino acids, Threonine, Milk hypersensitivity, Safety, Growth

Introduction

Infants with enteropathy who cannot be breast-fed, are best treated by replacing milk from their diet with alternative formulas based on hydrolyzed proteins or on amino acids. Hydrolyzed formulas have been shown to provide adequate nutrition in asymptomatic, unselected, healthy infants (Vandenplas et al. 1993; Exl et al. 2000). In one of these studies, hydrolyzed formula was shown to promote normal growth of healthy infants during at least the first 3 months of life even though the mean caloric intake was lower than that of infants fed on non-hydrolyzed formula (Vandenplas et al. 1993). Concentrations of zinc, urea, and iron binding capacity were also higher in infants fed on the hydrolyzed formula (but within normal range), and all other blood nutritional parameters were similar in the two groups (Vandenplas et al. 1993).

On the other hand, in infants with enteropathy of heterogeneous etiology, such as post-enteritis syndrome and cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA), the nutritional situation is different. For instance, it has been shown that children with CMPA ingest significantly smaller volumes of formula, and therefore a lower intake of calories, protein and fat compared to normal children (Tiainen et al. 1995). Consequently, allergic children on elimination diets who are not fed hydrolyzed formulas are significantly smaller than non-allergic children (Tiainen et al. 1995; Christie et al. 2002). Christie et al. showed that over a third of the children allergic to two or more foods and on an elimination diet were smaller than the 25th percentile for height-for-age, and more of these infants consumed less than 67% of the dietary reference for calcium, vitamin D and vitamin E, compared to healthy infants (Christie et al. 2002). Because children with GI diseases on an elimination diet are at an increased risk for growth retardation, their nutritional intake has to be closely monitored and formulas with sufficient supplementation of nutrients with improved absorbability need to be provided.

In the current study, we evaluated the nutritional adequacy and short-term safety of a formula for infants who require enteral feeding. This formula is based on an improved protein hydrolysis technique that generates an amino acid profile that better resembles that of breast milk (lower concentration of threonine) compared to the previous formula (Alfaré). It also contains nucleotides, which are thought to have beneficial effects on the immune and GI systems of infants (Yau et al. 2003; Carver 1999; Brunser et al. 1994).

Subjects and methods

Study design and population

This was a prospective, open, 4-week, mono-center study carried out in the Department of Pediatrics at the Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (Brussels, Belgium). Inclusion criteria were gestational age of ≥26 weeks, weighing ≥1,500 g, and being ≤36 months old at the time of the study. Infants and children that were hospitalized because of a variety of symptoms of GI disease and required diagnostic workup and nutritional treatment with a semi-elemental formula for at least 1 month were eligible for inclusion. Patients who were less than 1-year old were fed solely with the study formula for 4 weeks, and for those older than 1 year the study formula constituted ≥75% of the total caloric intake. Patients who were expected to be fed exclusively through parenteral route for longer than a month were not eligible.

Weight, length, and blood parameters were measured at the beginning (day 0) and end (day 28 ± 3) of the study. Additional weight measurements were taken at weekly intervals. Acceptability and tolerance (volume of formula intake, GI symptoms, and stool characteristics) were recorded daily by the parents.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Vrije University (VUB, Brussels, Belgium) and conformed to the Helsinki Declaration. Parents of all patients gave their written consent.

Product

The study formula, New Alfaré (Nestlé, Switzerland), was a nutritionally complete, semi-elemental formula based on extensively hydrolyzed acid whey. It consisted of small peptides (80%) and amino acids (20%), fat, carbohydrates, and nucleotides (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Nutritional content of the study formula compared to the previous formulation and to human milk

| New Alfaré | Alfaré | Human milk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (g/100 kcal) | 3.0 | 3.4 | 1.85 |

| Amino acids (mg/100 kcal) | |||

| Threonine | 120 | 278 | 77 |

| Tryptophan | 79 | 64 | 32 |

| Nucleotides (mg/100 kcal) | 8 | – | 4.5–4.9 |

| Fat (g/100 kcal) | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.8 |

| Total saturated (%) | 52.2 | 65.2 | 43 |

| Total monounsaturated (%) | 29.5 | 20.2 | 41 |

| Total polyunsaturated (%) | 18.1 | 14.6 | 16 |

| MCTa (% ) | 39.6 | 48 | 2.0 |

| Carbohydrate (g/100 kcal) | 10.9 | 10.8 | 10.8 |

a MCT medium chain triglyceride

Values for breast milk are based on human milk for full-term infants

Table 2.

Peptide profile (% of total peptide) of New Alfaré and Alfaré

| Number of Amino Acids (molecular weight in Da) | % of total peptides |

|---|---|

| New Alfaré | |

| 1–2 (<240) | 25 |

| 3–5 (240–600) | 43 |

| 5–10 (600–1,200) | 26 |

| >20 (>2,400) | 0.3 |

| Alfaré | |

| 1 (<200) | 22 |

| 2–3 (200–500) | 40 |

| 4–9 (500–1,500) | 26 |

| >20 (>2,400) | 1 |

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was growth relative to Euro-growth references (van’t Hof and Haschke 2000). Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on electronic scales and length was measured to the nearest 5 mm using a standardized length board. BMI-for-age z-scores were calculated based on the Euro-growth references. The secondary outcomes were tolerance and nutritional adequacy. Tolerance was evaluated based on: intake of the study formula (volume and calories/kg weight/day); stool characteristics, based on frequency in 24 h, consistency (liquid, soft, formed, and hard), color (black, brown, green, and yellow), and presence or absence of blood in stools; and GI symptoms (occurrence of flatulence and cramps and the frequency of spitting up or vomiting). Nutritional adequacy was evaluated based on measurements of blood concentrations of albumin, amino acids, retinol binding protein (RBP), and erythrocyte lipid profiles. Concentrations of sodium, chloride, potassium, bicarbonate, calcium, urea, C-reactive protein (CRP), alkaline phosphatase, urea nitrogen, triglycerides were also determined using standard analytical procedures. All blood parameters were measured at the beginning and end of the study.

Adverse events (AE)

AE were defined as illnesses and signs or symptoms of illnesses that occurred or worsened during the course of the study, or any abnormal laboratory findings. All AE was evaluated and assessed for seriousness and relation to the study formula by the investigator.

Statistical analysis

To obtain an accuracy of 0.2 z-points in the improvement of BMI with 95% confidence, 25 patients were required to complete the study. Assuming a 20% dropout, 32 patients had to be enrolled. For patients who had a gestational age of <37 weeks, their BMI z-scores were calculated based on their corrected age (subtracting the difference between their gestational age and 37 from their current age). Both primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed in the per protocol (PP) population. AE was analyzed in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population.

Mean plasma amino acid and fatty acid concentrations on days 0 and 28 were compared by paired t test.

Results

Study population

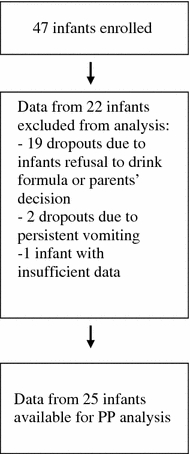

Forty-seven patients with symptoms of functional GI diseases, suggesting enteropathy, malabsorption, or CMPA were enrolled in the study (ITT population). Nineteen patients dropped out from the study either because they refused to drink the study formula or because the parents chose not to continue in the study, and two infants were withdrawn by the investigator due to persistent vomiting. One infant was dropped from the analysis because of lack of data on length, blood analysis or tolerance. Thus, there were 25 infants (11 boys and 14 girls) in the PP population (Table 3). They had been admitted to hospital for post-enteritis syndrome, including necrotizing enterocolitis (n = 2), gastroenteritis including rota virus infection (n = 8), food allergies including suspected and confirmed CMPA (n = 8) and other GI problems (e.g., failure to thrive, chronic diarrhea, and intestinal colic, n = 7).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the PP population at enrolment

| n | Mean (SD) | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | 25 | 38.6 (3.0) | 39.0 | 28.0–41.0 |

| Age (weeks)a | 25 | 23 (20) | 19 | 3–87 |

| Weight (g) | 25 | 3,139 (733) | 3,280 | 1,090–3,990 |

| Length (cm) | 24 | 49.2 | 49.6 | 39.0–52.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25 | 13.17 | 13.50 | 7.17–15.83 |

aAge at the beginning of formula administration (day 0)

Outcomes

Mean weight-for-age z-score did not change (P > 0.05) whereas mean length-for-age z-score showed a significant decrease at the end of the study (P < 0.005). The mean BMI-for-age z-score showed a significant increase after 4 weeks of feeding with the study formula (mean change = 0.54 [95% CI:+0.09 to +0.99], P = 0.02, Fig. 1). One of the premature infants showed the largest increase in BMI-for-age z-score, but even when its data were removed from analysis there was still a significant increase in mean the BMI-for-age z-score (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients in the study

The patients in the PP population consumed an average of 122.5 ± 38.3 ml/kg/day corresponding to 85.8 ± 26.8 kcal/kg/day (range: 35–137 kcal/kg/day). They had an average stool frequency of 2.1 ± 1.2/day, with soft and formed stools occurring more frequently (54%) than liquid stools (15%). No hard stools were reported. Brown and yellow stools occurred at about the same frequency as green stools (33 vs. 32%) and blood was reported once in the stools of three patients. During the feeding period with the study formula, there was a record of at least one incidence of flatulence in 16 infants (64%), cramps in 19 infants (76%), spitting up in 20 infants (50%), and vomiting in 17 infants (68%).

Compared to the beginning of the study, there was a significant increase in albumin concentration (from 3.45 ± 0.55 to 3.83 ± 0.58 g/dl, P < 0.001) at the end of the study. All other blood parameters, excluding amino acid concentrations, remained within the normal range, and apart from sodium concentration (which decreased slightly) did not show any significant change during the study.

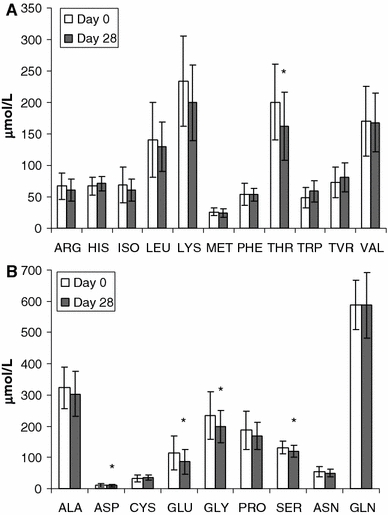

The plasma concentrations of threonine and four non-essential amino acids (aspartate, glutamine, glycine, and serine) decreased significantly (P ≤ 0.01, Fig. 2) at the end of the study. On the other hand, the concentration of tryptophan tended to increase (from 49.0 to 58.9 μmol/l), with the ratio of tryptophan relative to the other neutral amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, valine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine) higher at the end of the study (P = 0.07). There were no significant differences in the concentrations of short- and medium-chain fatty acids between the beginning and end of the study (data not shown). However, there was a significant increase in the concentrations of some long-chain fatty acids including di-homogammalinolenic acid (C20:2n-6), arachidonic acid (C22:4n-6), and eicosapentanoic acid (C20:5n-3). There was a significant decrease in the concentrations of palmitoleic acid (C16:1n7c), behenic acid (C22:0), and arachidic acid (C20:0) (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Mean ± SD plasma amino acid concentration of patients in the PP population. (a) Concentration of essential amino acids and (b) concentration of non-essential amino acids. * indicates t test P ≤ 0.01

Table 4.

Mean (standard deviation) percent of fatty acid acids with significant change after 4 weeks on study formula

| Fatty acid | Before | After | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| C20:3n6 | 2.13 (0.74) | 2.57 (0.74) | <0.001 |

| C20:5n3 | 0.44 (0.16) | 0.54 (0.15) | <0.001 |

| C22:4n6 | 4.26 (0.48) | 4.44 (0.47) | 0.04 |

| C16:1n7c | 0.32 (0.16) | 0.26 (0.11) | 0.02 |

| C20:0 | 0.37 (0.12) | 0.28 (0.09) | <0.01 |

| C22:0 | 1.08 (0.44) | 0.84 (0.41) | 0.02 |

aComparisons made by paired t test

Fifty-four adverse events were reported in 26 patients. Most of these were GI disorders (Table 5). The rest included infections, respiratory disorders, and medical procedures such as vaccination and mineral or vitamin supplementation. None of the AE was assessed to be related to the study formula. No serious adverse events occurred during the trial.

Table 5.

Adverse events reported in the study (ITT population)

| Adverse event preferred term | Number of events | Number of patients with the event |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrooesophageal reflux disease | 13 | 10 |

| Oesophagitis | 7 | 7 |

| Vitamin supplementation | 4 | 4 |

| Prophylaxis | 3 | 3 |

| Spesis | 3 | 2 |

| Enterocolitis infectious | 2 | 1 |

| Gastric disorder | 2 | 2 |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | 2 | 2 |

| Constipation | 2 | 2 |

| Bronchiolitis | 2 | 1 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 1 |

| Allergic colitis | 1 | 1 |

| Otitis media acute | 1 | 1 |

| Pneumonia bacterial | 1 | 1 |

| Increased viscosity of bronchial secretion | 1 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 1 |

| Anaemia neonatal | 1 | 1 |

| Neonatal apnoeic attack | 1 | 1 |

| Convulsion | 1 | 1 |

| Iron deficiencies | 1 | 1 |

| Pruritus ani | 1 | 1 |

| Laryngeal oedema | 1 | 1 |

| Eczema | 1 | 1 |

| Reflux gastritis | 1 | 1 |

Discussion

Development of infant formula is geared towards attaining a similar nutritional profile as human milk. Extensively hydrolyzed, whey-predominant formulas developed for infants with food allergies have been shown to promote growth of healthy infants similar to those who are breast-fed infants (Raiha et al. 2002; Vandenplas et al. 1993). Nevertheless, the nutritional adequacy of these formulas in sick children cannot be taken for granted. Thus, in this study, we evaluated whether New Alfaré is safe and provides sufficient nutrients in sick infants and children.

The subjects in this study were hospitalized infants and children, all of whom had GI problems severe enough to require enteral feeding. Their BMI-for-age z-scores relative to Euro-growth standards increased after 4 weeks of feeding with the new study formula (P < 0.05), suggesting the patients were catching up to the BMI of healthy infants. However, we are cautious in interpreting this observation; even though mean weight-for-age z-score was the same at the beginning and end of the study (P > 0.05), suggesting that the patients grew at a similar rate compared to the Euro-growth standards, there was a significant decrease in the mean length-for-age z-score at the end of the study (P < 0.005). Despite the statistical significance of the decrease in the mean length-for-age z-score, we do not think that this change is of clinical importance since the study period was probably too short to see any meaningful change in length. Furthermore, length measurements for this population are prone to high error rates and small changes cannot be accurately determined. Caution is also warranted in interpreting the lower BMI of infants in this study compared to Euro-growth references since the subjects were sick and some growth problems were to be expected. Thus, similar studies with longer duration will be necessary to confirm these results.

Whey- and total cow milk-based formulas contain much higher concentrations of amino acids and consequently, formula-fed infants tend to have higher plasma amino acid concentrations (Raiha 1989). A correlation between the amino acid concentrations in formulas and the plasma of infants fed on these formulas has been suggested previously (Priolisi et al. 1992; Rigo et al. 1989). Threonine, in particular, is present at significantly higher concentrations (two to three times higher) in infants fed whey-based formulas compared to infants fed human milk (Darling et al. 1999; Janas et al. 1985; Rigo et al. 1994a). This has called the safety of these formulas into question and recommendations to reduce threonine in infant formulas have been made (Picaud et al. 2001; Rigo et al. 1994b).

Accordingly, New Alfaré has a reduced threonine concentration compared to the previous formulation (Alfaré). After 4 weeks of feeding with New Alfaré, the plasma concentration of five amino acids, including threonine, showed a significant decrease but they remained within the normal range. The mean plasma threonine concentration at the end of the study (162.3 ± 53.6 μmol/l) was similar to concentrations observed in breast-fed infants (Janas et al. 1985; Jarvenpaa et al. 1982), suggesting that the threonine level in patients may have been effectively modulated by New Alfaré.

Similarly, the concentration of tryptophan, which was higher in New Alfaré compared to Alfaré, tended to increase in the patients at the end of the study. Unlike threonine, plasma concentration of tryptophan is generally lower in formula-fed infants compared with breast-fed infants (Fazzolari-Nesci et al. 1992; Janas et al. 1987; Lonnerdal and Chen 1990) and has raised concerns that this may cause metabolic or behavioral effects. Although no clear evidence is available from clinical trials, as a precursor of serotonin, tryptophan has been hypothesized to affect the sleeping behavior of infants. The relative increase in plasma concentration of tryptophan compared to the other neutral amino acids suggests that the proportion of tryptophan delivered to the brain is likely to increase. Finally, mean albumin concentration, which was below the normal range at the beginning of the study, increased significantly at the end of the study to within normal concentrations, indicating an improvement in the nutritional status of patients.

This study suggests that the new hydrolysis technique used in the preparation of New Alfaré appears to improve the nutritional quality of the formula by supplying less threonine and more tryptophan than standard hydrolyzed formulas. We demonstrated that “New Alfaré” has good short-term acceptability, tolerance, nutritional adequacy, and safety in infants and children who require semi-elemental diet for a variety of GI problems. Nevertheless, the effect of the formula on the growth of infants with GI diseases should be confirmed in long-term studies.

Acknowledgment

We thank Corinne Hager for statistical analysis and Makda Fisseha for medical writing services on behalf of HPM Geneva S.A. This study was sponsored by Nestlé Nutrition-Nestec Ltd. (Vevey, Switzerland).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse events

- BMI

Body mass index

- CMPA

Cow’s milk protein allergy

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- GI

Gastro-intestinal

- ITT

Intent-to-treat

- PP

Per protocol

- RBP

Retinol binding protein

References

- Brunser O, Espinoza J, Araya M, Cruchet S, Gil A. Effect of dietary nucleotide supplementation on diarrhoeal disease in infants. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:188–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver JD. Dietary nucleotides: effects on the immune and gastrointestinal systems. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1999;88:83–88. doi: 10.1080/080352599750029790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie L, Hine RJ, Parker JG, Burks W. Food allergies in children affect nutrient intake and growth. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1648–1651. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling PB, Dunn M, Sarwar G, Brookes S, Ball RO, Pencharz PB. Threonine kinetics in preterm infants fed their mothers’ milk or formula with various ratios of whey to casein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:105–114. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exl BM, Deland U, Secretin MC, Preysch U, Wall M, Shmerling DH. Improved general health status in an unselected infant population following an allergen-reduced dietary intervention programme: the ZUFF-STUDY-PROGRAMME. Part II: infant growth and health status to age 6 months. ZUg-FrauenFeld. Eur J Nutr. 2000;39:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s003940070018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzolari-Nesci A, Domianello D, Sotera V, Raiha NC. Tryptophan fortification of adapted formula increases plasma tryptophan concentrations to levels not different from those found in breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;14:456–459. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199205000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas LM, Picciano MF, Hatch TF. Indices of protein metabolism in term infants fed human milk, whey-predominant formula, or cow’s milk formula. Pediatrics. 1985;75:775–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas LM, Picciano MF, Hatch TF. Indices of protein metabolism in term infants fed either human milk or formulas with reduced protein concentration and various whey/casein ratios. J Pediatr. 1987;110:838–848. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvenpaa AL, Rassin DK, Raiha NC, Gaull GE. Milk protein quantity and quality in the term infant. II: effects on acidic and neutral amino acids. Pediatrics. 1982;70:221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnerdal B, Chen CL. Effects of formula protein level and ratio on infant growth, plasma amino acids and serum trace elements. I: cow’s milk formula. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:257–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picaud JC, Rigo J, Normand S, Lapillonne A, Reygrobellet B, Claris O, Salle BL. Nutritional efficacy of preterm formula with a partially hydrolyzed protein source: a randomized pilot study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:555–561. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200105000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priolisi A, Didato M, Gioeli R, Fazzolari-Nesci A, Raiha NC. Milk protein quality in low birth weight infants: effects of protein-fortified human milk and formulas with three different whey-to-casein ratios on growth and plasma amino acid profiles. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;14:450–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiha NC. Milk protein quantity and quality and protein requirements during development. Adv Pediatr. 1989;36:347–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiha NC, Fazzolari-Nesci A, Cajozzo C, Puccio G, Monestier A, Moro G, Minoli I, Haschke-Becher E, Bachmann C, Van’t Hof M, Carrie Fassler AL, Haschke F. Whey predominant, whey modified infant formula with protein/energy ratio of 1.8 g/100 kcal: adequate and safe for term infants from birth to four months. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:275–281. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo J, Verloes A, Senterre J. Plasma amino acid concentrations in term infants fed human milk, a whey-predominant formula, or a whey hydrolysate formula. J Pediatr. 1989;115:752–755. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(89)80656-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo J, Salle BL, Cavero E, Richard P, Putet G, Senterre J. Plasma amino acid and protein concentrations in infants fed human milk or a whey protein hydrolysate formula during the first month of life. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo J, Salle BL, Putet G, Senterre J. Nutritional evaluation of various protein hydrolysate formulae in term infants during the first month of life. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;402:100–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen JM, Nuutinen OM, Kalavainen MP. Diet and nutritional status in children with cow’s milk allergy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49:605–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van’t Hof MA, Haschke F. Euro-growth references for body mass index and weight for length: Euro-Growth Study Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31(Suppl 1):S48–S59. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200007001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenplas Y, Hauser B, Blecker U, Suys B, Peeters S, Keymolen K, Loeb H. The nutritional value of a whey hydrolysate formula compared with a whey-predominant formula in healthy infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:92–96. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau KI, Huang CB, Chen W, Chen SJ, Chou YH, Huang FY, Kua KE, Chen N, McCue M, Alarcon PA, Tressler RL, Comer GM, Baggs G, Merritt RJ, Masor ML. Effect of nucleotides on diarrhea and immune responses in healthy term infants in Taiwan. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]