Abstract

The optimal administration time for applying epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors combined with radiotherapy has been unclear. We investigated the efficacy of combining gefitinib with radiation in different treatment schedules. We demonstrated that gefitinib was administered to A549 lung cancer cells in three ways (administration before irradiation, administration upon irradiation, administration after irradiation) to establish the radiosensitizing effect. Cell‐survival rates were evaluated by colony‐forming assays. Cell apoptosis and cell‐cycle distribution were investigated using flow cytometry; meanwhile, the expression of P21, Cdc25c, Bcl‐2, Bax, Rad51 and phosphorylated DNA‐PKcs (phospho‐DNA‐PK) after 6 Gy irradiation and/or gefitinib were determined by Western blot analysis. The sensitizer enhancement ratios of the gefitinib administration before irradiation, administration upon irradiation, and administration after irradiation groups were 2.23, 1.51 and 1.30, respectively. A higher apoptosis rate and G2/M phase arrest were observed in cells at 48 h after exposure to 6 Gy irradiation when gefitinib was administrated before irradiation. Increased cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest were further supported by the expression changes of Bcl‐2, Bax, P21, Cdc25c, Rad51 and phospho‐DNA‐PK at the same time. The best radiosensitizing effect was obtained when gefitinib was delivered before irradiation. Apoptosis might be an important way of cell killing and G2/M phase arrest might be an important mechanism of apoptosis. The expression proportion changes of P21/Cdc25c proteins may play an important role in G2/M cell cycle arrest. Moreover, the pro‐apoptotic/antiapoptotic and DNA repair factors may be important modulators taking part in the molecular events of the radiosensitizing effect of gefitinib combined with irradiation. (Cancer Sci 2009)

It is known that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that regulates fundamental processes of cell growth and differentiation. Overexpression of EGFR and its ligands were reported for various epithelial tumors in the 1980s( 1 , 2 ) and interest was generated in EGFR as a potential target for cancer therapy.( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) These efforts have been rewarded in recent years, as ATP site‐directed EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors has shown antitumor activity in subsets of patients with non‐small cell lung cancer,( 10 , 11 ) squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck( 12 ) and other malignancies.( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ) Rather, their greatest potential may be realized when used in conjunction with conventional anticancer therapies, for example, radiotherapy. The best validation of this combination has been the results of clinical trials in patients. However, in most studies, EGFR inhibitors were given once a week at the same time or close to the time of the first fraction radiotherapy.( 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ) The optimal administration time of EGFR inhibitors combined with radiotherapy has not been studied. The data presented herein describe the different radiosensitizing effects and the mechanisms of tyrosine kinase inhibitors at different times for adding drugs in A549 lung cancer cells. Our study may have potential effects on the clinical applications of combining tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) with irradiation therapy to improve the therapeutic effects.

Materials and Methods

Reagents. Cell culture media were provided by Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute (Dr JP Yu). Primary antibodies against phosphorylated EGFR (phospho‐EGFR), Bcl‐2, Bax, P21, Cdc25c, Rad51 and phospho‐DNA‐PK were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA); Propidium iodide (PI) and annexin V were purchased (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Gefitinib was generously provided by AstraZeneca (ZY You, Beijing). All other materials were from the Cancer Institute of our university.

Cell culture. The A549 lung cancer cell line was kindly provided by Peking University Center for Human Disease Genomics. It was maintained in RPMI1640 supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 4 mM glutamine and 10% heat‐inactivated FBS (Hangzhou Sijiqing Biological Engineering Materials Company, Hangzhou, China) in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Ionizing radiation treatment. Exponentially growing A549 cells in a tissue‐culture flask (75 cm2) were irradiated by an X‐ray generator (Elekta Precise, Stockholm, Sweden) with a 1.0‐mm aluminum filter at 200 kV and 10 mA, at a dose of 1.953 Gy/min, which was determined using a Fricke's chemical dosimeter. Radiation was performed in the Tianjin Medical University Cancer hospital.

Clonogenic survival.

Clonogenic survival is defined as the ability of cells to maintain clonogenic capacity and to form colonies. Briefly, cells of the control and gefitinib groups were exposed to different radiation dosages (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 Gy). After incubation for 14 days, the cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted. The plating efficiency (PE) and surviving fraction (SF) were calculated as follows: PE = (colony number/inoculating cell number) × 100%; SF = PE (tested group)/PE(0‐Gy group) × 100%. A dose‐survival curve was obtained for each experiment and used for calculating several survival parameters. Parallel samples were set at each radiation dosage. The cell‐survival curve was plotted with Origin v7.5 software, using the equation:  . The multitarget, single‐hit model was applied to calculate the cellular radiosensitivity (mean lethal dose, D0), the capacity for sublethal damage repair (quasithreshold dose, Dq), and the extrapolation number (N). The D0 values were used to calculate the sensitizer enhancement ratios (SER).

. The multitarget, single‐hit model was applied to calculate the cellular radiosensitivity (mean lethal dose, D0), the capacity for sublethal damage repair (quasithreshold dose, Dq), and the extrapolation number (N). The D0 values were used to calculate the sensitizer enhancement ratios (SER).

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry (FCM). The treatment schedule for FACS incorporated five groups in the experiments (control, gefitinib‐treated, irradiation‐treated, and gefitinib‐pre, post, and concurrent with irradiation). Additions of gefitinib were carried out 24 h before irradiation, the same time of irradiation, and 24 h after irradiation in the three combination groups, respectively. After 12 h of incubation, gefitinib was removed and replaced with fresh media in all treatment schedules. The dose of gefitinib used for the present experiments was 100 nmol/L. The radiation‐alone group and the combination groups were all exposed to X‐rays at 6 Gy and all the cells were harvested 48 h after irradiation. For detection of apoptotic cells, cells were trypsinized, counted and washed twice with cold PBS. Cells used for apoptosis tests were stained with PI and annexin V for 15 min in the dark. Cells used for cell‐cycle testing were stained with PI after ethanol fixation and analyzed by fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) using Coulter EPICS and ModFit software (Verity Software House, Topsham, MN). Each test was performed three times.( 23 )

Western blot analysis. Western blot analysis was used to determine the P21, Cdc25c, Bcl‐2, Bax, Rad51 and phospho‐DNA‐PK expression in A549 cells after irradiation and/or gefitinib treatment. The treatment schedule for Western blot analysis was the same as FACS. After treatment, cells were collected, and total protein was extracted, resolved, and analyzed by Western blot analysis. In brief, cells were washed with cold PBS, scraped in RIPA buffer (100 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 5% NP40, pH 8.0) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and kept for at least 30 min on ice. Cells were subjected to further analysis by one freeze–thaw cycle and centrifuged at 14 000g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatants were carefully removed and protein concentrations were determined by a Bio‐Rad‐DC protein estimation kit (Bio‐Rad, CA, USA). Electrophoresis was performed on polyacrylamide gel (10%) using equal amounts of protein samples under reducing conditions. Resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with primary antibodies followed by incubation with corresponding horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies. The signal was detected with an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Kit (Amersham Biosciences). Meanwhile, Western blot analysis was used to determine the EGFR expression of A549 cells.

Statistical analysis. Data were plotted as means ± SD. A Student's t‐test was used for comparisons. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

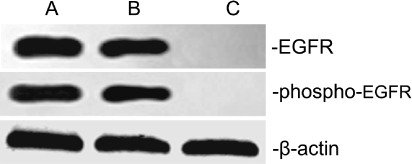

EGFR expression of A549 cells. It was reported that A549 cells might express EGFR.( 24 ) In the present study, we confirmed the expression of the bulk of EGFR and phospho‐EGFR on A549 cells by using western‐blot analysis (Fig. 1). A549 cells expressed high levels of EGFR and phospho‐EGFR, as reported previously.( 24 ) The A431 skin cancer cell was as a positive control and the striated muscle cell of nude mouse was as the negative control.

Figure 1.

EGFR and phospho‐EGFR expressions in A549 cells. Western blots of EGFR, phospho‐EGFR and β‐actin as a control. A549 cells expressed high levels of EGFR and phospho‐EGFR (lanes A). The A431 skin cancer cell was as a positive control (lanes B) and the striated muscle cell of nude mouse was as the negative control (lanes C).

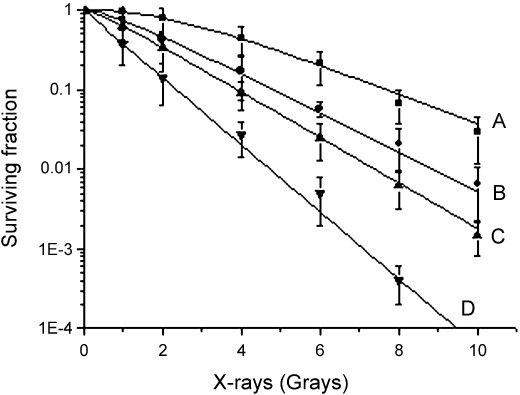

Survival curve of A549 cells after different dose irradiation and/or gefitinib. The plating efficiency of A549 cells was between 60 and 90%. The survival curve of control and gefitinib‐treated A549 cells after irradiation is shown in Fig. 2. The radiobiological parameters of gefitinib‐treated A549 cells were D0 = 1.02, Dq = 0.12, N = 1.31 in groups of administration before irradiation; D0 = 1.50, Dq = 0.21, N = 1.35 in groups of administration with irradiation synchronously; and D0 = 1.74, Dq = 0.35, N = 1.58 in groups of administration after irradiation, while those of A549 cells radiated alone were D0 = 2.27, Dq = 1.08, N = 3.00. In the present study, SER = D0 (control)/D0 (gefitinib group). Data for different groups are shown in Table 1. The enhanced SER in gefitinib‐treated cells indicated that treatment with gefitinib significantly improved the biological effect of irradiation, and 24 h before irradiation was found to be the optimal administration time for the enhancement of radiosensitivity.

Figure 2.

Dose–survival curves of A549 cells after irradiation with and without gefitinib at different administration times. A, Radiation; B, gefitinib administration after irradiation; C, gefitinib administration upon irradiation; D, gefitinib administration before irradiation. Compared with the other groups, the cells exposed to gefitinib before irradiation revealed more sensitivity to X‐rays.

Table 1.

Radiobiological parameters of A549 cells after irradiation and/or gefitinib at different administration times

| D0 | Dq | N | SER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation | 2.27 | 1.08 | 3.00 | – |

| Gefitinib before radiation | 1.02 | 0.12 | 1.31 | 2.23 |

| Gefitinib upon radiation | 1.50 | 0.21 | 1.35 | 1.51 |

| Gefitinib after radiation | 1.74 | 0.35 | 1.58 | 1.30 |

D0, mean lethal dose; Dq, quasithreshold dose, the capacity for sublethal damage repair; N, extrapolation number; SER, sensitizer enhancement ratios.

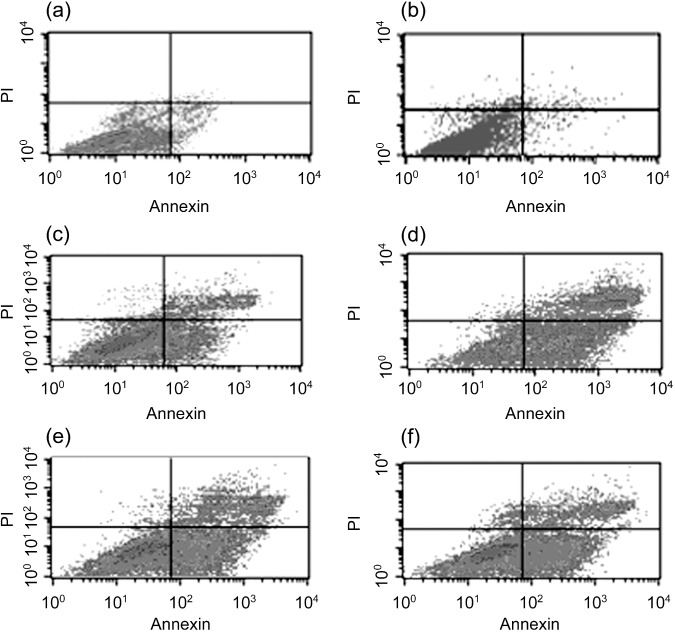

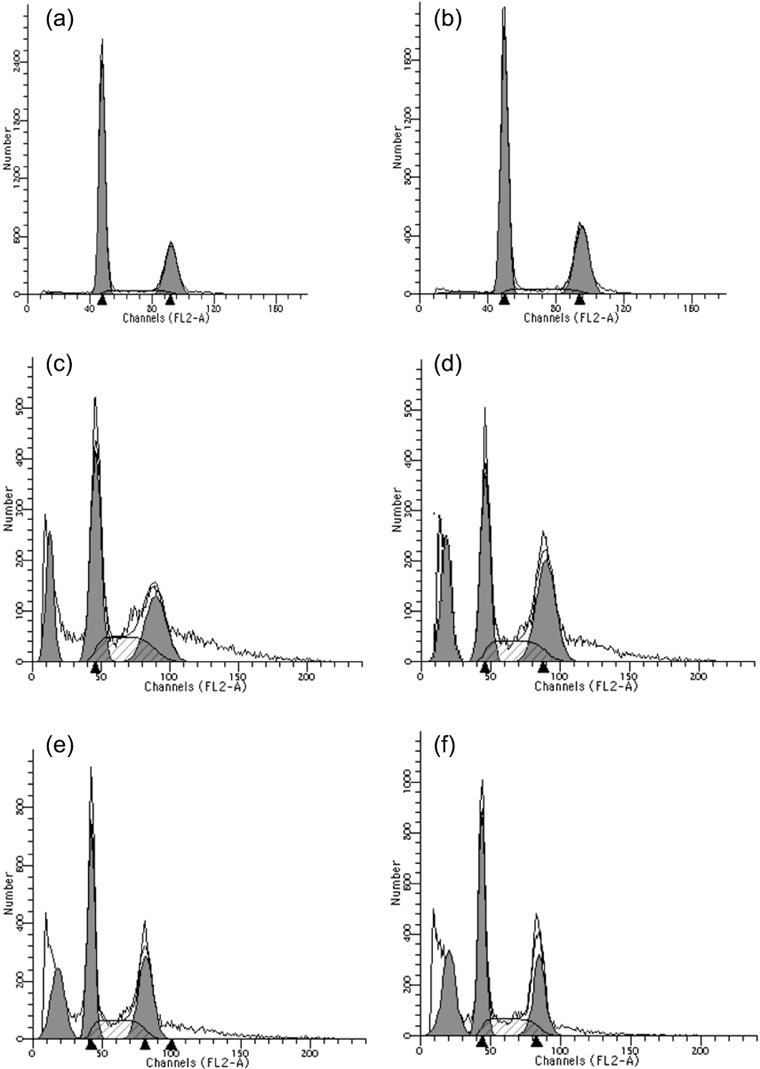

Cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Cell death was detected by FCM in the present study, as shown in Table 2 and 3, 4. In combination groups, the A549 cells had higher apoptosis rates than gefitinib/irradiation‐treated groups. The G2/M cell cycle arrest rates of combination groups were also significantly higher than irradiation‐treated A549 cells after 6 Gy irradiation. Change tendency of the apoptosis index was in accordance with that of G2/M cell cycle arrest rates, and the effect of administration before irradiation group was most significant (P < 0.05 compared with every group, paired Student's t‐test). Quantitative measurements of apoptotic cell death and G2/M cell cycle arrest by FCM in A549 indicated that apoptosis followed by G2/M cell cycle arrest might be an important mechanism of the radiosensitizing effect.

Table 2.

Apoptosis index and cell cycle distribution after irradiation and/or gefitinib at different administration times (%, × ± s)

| Apoptosis | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.67 ± 0.59 | 64.94 ± 5.87 | 8.62 ± 0.59 | 26.44 ± 2.53 |

| Gefitinib | 11.74 ± 1.63 | 84.14 ± 3.16 | 6.25 ± 1.34 | 9.61 ± 2.79 |

| Radiation | 16.27 ± 3.82 | 36.60 ± 2.84 | 13.56 ± 2.68 | 49.84 ± 4.96 |

| Gefitinib before radiation | 53.46 ± 7.61* | 21.69 ± 4.58 | 6.72 ± 2.29 | 71.59 ± 5.21* |

| Gefitinib upon radiation | 39.58 ± 6.25 | 25.87 ± 5.37 | 11.54 ± 3.49 | 62.59 ± 5.63 |

| Gefitinib after radiation | 32.58 ± 3.84 | 31.73 ± 4.29 | 12.68 ± 2.15 | 55.59 ± 6.81 |

P < 0.05 compared with every group, paired Student's t‐test.

G1, cells intermediate sensitivity to radiation; G2/M, cells most sensitive to irradiation; S, cells resistant to radiation.

Figure 3.

A549 cell apoptosis rates of combining gefitinib with radiation in different treatment schedules. The apoptotic rates were detected by flow cytometry. There were few apoptotic cells in (a) control group, (d) administration before irradiation group, (e) administration upon irradiation group and (f) administration after irradiation group. A549 cells had higher apoptosis rates when compared with (c) irradiation or (b) gefitinib‐alone treated group, and the highest was in gefitinib preradiation treatment group.

Figure 4.

Effects of irradiation and/or gefitinib‐treatment on cell cycle distribution in A549 cells. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the fraction of cells in G0/G1 increased after treatment with gefitinib (b) while those in G2/M increased after treatment with irradiation (c) compared with untreated cells (a). In administration before 6‐Gy irradiation group (d), a sharp increase in the fraction of cells in the G2/M phase was observed. The G2/M phase arrests in administration upon irradiation group (e) and administration after irradiation group (f) were lower than that in group D, but sustained at a relatively high level.

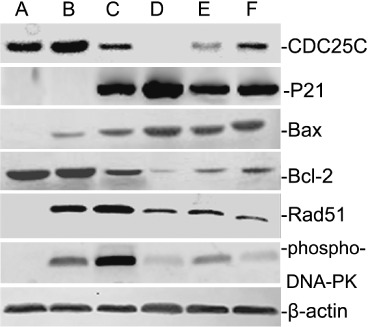

Expression of Bcl‐2, Bax, P21, Cdc25c, Rad51 and phospho‐DNA‐PK in A549 cells after irradiation and/or gefitinib treatment. At 48 h after 6 Gy radiation and/or gefitinib treatment, the Bax protein was increased and reached a peak in groups where gefitinib was administered before irradiation. On the contrary, the Bcl‐2 protein was decreased and showed the lowest value in the same groups. When G2/M phase arrests were observed, as an important factor in the regulation of the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint, P21 protein increased significantly and showed a maximum in the groups of gefitinib administration before irradiation. However, the other regulator of G2/M phase, the change in Cdc25c, showed the opposite trend. There were identical trends in the variation of phospho‐DNA‐PK and Rad51 among all the experimental groups (Fig. 5). That is, the root activity was low in control groups, while increasing after irradiation, and then decreasing when irradiation was combined with gefitinib. The protein changes suggested that a synergistic effect sequence for irradiation combined with gefitinib is: drugs delivered before radiation > drugs delivered upon radiation > drugs delivered after radiation.

Figure 5.

Expressions of Bcl‐2, Bax, P21, Cdc25c, Rad51 and phospho‐DNA‐PK in A549 cells subjected to 6 Gy irradiation and/or gefitinib‐treatment. Control groups (lanes A), gefitinib‐treated groups (lanes B), irradiation‐treated groups (lanes C), gefitinib preradiation treatment groups (lanes D), concurrent treatment groups (lanes E), gefitinib postradiation treatment groups (lanes F). The results suggested that the radiosensitizing effect of gefitinib combined with irradiation might be influenced by the protein related to cell cycle redistribution, the pro‐/antiapoptotic factors regulation, and DNA repair factors changes.

Discussion

After 30 years of exploration, from theory to practice, from research to clinical practice, EGFR has been identified as an important target for cancer therapies,( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) and EGFR inhibitors combined with radiotherapy have an encouraging curative effect in clinical practice.( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ) However, there is little research of optimal administration time when EGFR inhibitors are combined with radiotherapy and it is unclear.( 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ) In order to increase the efficacy of EGFR inhibitors combined with radiotherapy, optimal administration time is an urgent demand for cancer therapy.

Clonogenic assay is the classical method to evaluate the kill effectiveness of radiation. In comparison with the single irradiation and single gefitinib groups, it showed higher desirable results in every combined group. Further, the survival fraction in the group where gefitinib was administered before radiation was obviously higher than that in other synergistic groups. The dose–survival curve of administration before radiation exhibited a narrow shoulder (indicating decrease in D0 and N) and a greater slope (indicating decrease in Dq). The decreased SF value in the group cells indicated the greatest radiosensitization effect on A549 cells (P < 0.05 compared with other groups).

The apoptosis analysis provided comments for different SF curves when tyrosine kinase inhibitors were administered at different times. Our results indicated that exposure to gefitinib before radiation enhanced the apoptosis of A549 cells more significantly than the other groups. It also indicated that apoptosis was an important mechanism of cell death when radiation was combined with gefitinib. Then, the cell cycle arrest provided further support to the apoptosis. G2/M cell cycle arrest was observed in all cells exposed to irradiation and/or gefitinib at different degrees, and it was the most obvious in the group exposed to gefitinib before radiation. Thus, the entire results showed the cell cycle phase distribution might also play a central role regarding the observed enhancement of radiosensitivity. As for the reasons for the higher G2/M cell cycle arrest in groups were drugs were delivered before radiation than in groups where drugs were delivered upon radiation and drugs delivered after radiation, it may be that gefitinib induced G1 cell cycle arrest( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ) and played a role in cell cycle synchronization. When the gefitinib was removed, in the interval between administration and irradiation, the cell cycle arrest revived and moved simultaneously to the G2/M phase. As we know, the G2/M cells are most sensitive to irradiation, with G1 cells intermediate and S cells resistant.( 34 , 35 ) At this point, cells were irradiated with X‐rays. The radiosensitive cells easily trend to apoptosis or necrosis. As a result, the surviving fraction was further decreased and the radiosensitive effect was further improved. However, the situations were different in groups where drugs were delivered upon radiation and after radiation. Because of reasons of administration times, the G2/M arrest induced by irradiation and G1 arrest induced by gefitinib conflicted with each other. Cells did not move simultaneously to the radiosensitive phase when the cells were irradiated. Thereby, there was no opportunity for proliferation kinetics to promote the cell killing effect, and to influence the efficacy of irradiation combined with gefitinib.

Increased cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest were further supported by the expression changes of protein related to cell cycle redistribution, the pro‐/antiapoptotic factors and DNA repair factors. Our results indicate that exposure of A549 cells to gefitinib and radiation stimulated production of P21 protein and decreased the expression of Cdc25c, most obviously in the cells of gefitinib preradiation treatment groups. Both P21 and Cdc25c are important regulators of the G2/M checkpoint.( 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ) High expression of P21 could improve the G2/M cell cycle arrest and Cdc25c is the contrary. From the Cdc25c and P21 expression, we conclude that the expression chances of the pair of positive and negative regulators of the G2/M phase were one of the main reasons for different G2/M phase arrest when drugs were added at different times. Our results also showed that irradiation combined with gefitinib produced an increase in the expression of Bax protein and a decrease in the expression of Bcl‐2 (Fig. 5), and it was most significant in group of administration before radiation. As we know, Bax and Bcl‐2 are factors related to cell apoptosis. High expression of Bax protein could promote apoptosis and Bcl‐2 is the contrary. Based on this, we conclude the balance changes of promotion and inhibitory factors on apoptosis also influenced the killing effect. At the same time, significant reduction in the level of phospho‐DNA‐PK and Rad51 were observed in the experiments and most obviously in gefitinib preradiation treatment groups. Because phospho‐DNA‐PK and Rad51 are believed to play major roles in repairing DNA injuries,( 41 , 42 , 43 ) these findings suggest that irradiation combined with gefitinib might impair DNA repair by reducing the nuclear level of phospho‐DNA‐PK and Rad51. As for the lower expression of these two proteins in preradiation treatment groups, it was possible that the cells were in the radiosensitive phase when they were irradiated and prone to lethal damage after the same dose of irradiation. Therefore, the possibility of repair was relatively less and the expression of repair‐related proteins decreased. As a result, the surviving fraction decreased and the radiosensitive effect increased.( 44 , 45 ) The trend of changes and expression levels in these genes provided an experimental basis at a deeper level for different radiosensitizing effects after different schedules.

It must be pointed out that the research was focused on the radiosensitization of different administration times for single irradiation. However, there is fractionated radiotherapy in clinical settings. After the first fractionated irradiation, the proliferation kinetics influenced by the subsequent process may be complicated when gefitinib is combined with irradiation, and the detailed effect on proliferation kinetics of gefitinib is unclear. Regarding these factors, because the best time for drug delivery was before irradiation, the damage effects of gefitinib and the influence on proliferation kinetics of the tumor cells had been formed before irradiation. Based on this, the effect of gefitinib combined with the first fractionated irradiation was more powerful and important than the influence of subsequent radiation. So, this study on the combination of gefitinib with single irradiation is still significant for improving the radiotherapeutic effect. In addition, only one cell line was studied in the experiment in vitro, and more cell lines should be studied and experiments in vivo conducted.

In contrast to previous reports, we found that treatment schedule was important when gefitinib was combined with irradiation, as it did in previous studies.( 46 , 47 ) However, we studied SF, cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, cell cycle related proteins, apoptosis related proteins and DNA repair in the present experiments. Results were more comprehensive and persuasive when compared with previous reports. The major difference between our study and other studies was that the optimal administration time is different; it is possible that the mitotic cycle times were different in different cells. However, considering the G1 cell cycle arrest when gefitinib acted on cancer cells and the general law of cell proliferation kinetics, gefitinib preradiation treatment should cause the optimal administration time for the radiosensitizing effect.

In summary, our study provides a beneficial exploration of optimal administration time when gefitinib is combined with radiation. Although many issues remain to be addressed, we believe that, with further development of fundamental research, application of irradiation in combination with EGFR inhibitors in clinical practice will continue to be improved.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr J Zhang for his kind review of the manuscript, Dr F Wei for expert technical assistance and Ms MY Wang for excellent laboratory management. This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Civil Affair, China ([2008]18).

Hong‐Qing Zhuang and Jian Sun contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Masui H, Kawamoto T, Sato JD et al . Growth inhibition of human tumor cells in athymic mice by anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res 1984; 44: 1002–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yaish P, Gazit A, Gilon C et al . Blocking of EGF‐dependent cell proliferation by EGF receptor kinase inhibitors. Science 1988; 242: 933–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gschwind A, Fischer OM, Ullrich A. The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jose B. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway inhibitors. Update on Cancer Therapeut 2006; 1: 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fortunato C, Giampaolo T. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1160–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fortunato C, Giampaolo T. Novel approach in the treatment of cancer: targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 2958–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu ZP. Targeted cancer therapies based on antibodies directed against epidermal growth factor receptor: status and perspectives. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2007; 28: 1476–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harari PM. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition strategies in oncology. Endocr Relat Cancer 2004; 11: 689–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olivier D, Alexandre B, Gerard M et al . EGFR targeting therapies: monoclonal antibodies versus tyrosine kinase inhibitors similarities differences. Crit Rev Oncol Hemato 2007; 62: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non‐small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 290: 2149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G. Multi‐institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected]. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 2237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous‐cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 567–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan‐refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haas‐Kogan DA, Prados MD, Tihan T. Epidermal growth factor receptor, protein kinase B/Akt, and glioma response to erlotinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 880–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinaseinhibitors. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2012–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barber TD, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Somatic mutations of EGFR in colorectal cancers and glioblastomas. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2270–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marie Y, Carpentier AF, Omuro AM. EGFR tyrosine kinase domain mutations in human gliomas. Neurology 2005; 64: 1444–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harari PM. Promising new advances in head and neck radiotherapy. Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crombet T, Osorio M, Cruz T et al . Use of the humanized anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody h‐R3 in combination with radiotherapy the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 1646–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang RR, Wang SX, Zhao C et al . Phase II clinical trial of h‐R3 combined radiotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer 2007; 26: 874–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang XD, Yi JL, Gao L et al . Multi‐center phase II clinical trial of humanized anti‐epidermal factor receptor monoclonal antibody h‐R3 combined with radiotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Onco 2007; 29: 197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. James AB, Paul MH, Abdollahi A et al . Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous‐cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Engl J Med 2006; 354: 567–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prakash C, Shyhmin H, Geetha V et al . Mechanisms of enhanced radiation response following epidermal growth factor receptor signaling inhibition by erlotinib (Tarceva). Cancer Res 2005; 65: 3328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaramillo ML, Banville M, Collins C et al . Differential sensitivity of A549 non‐small lung carcinoma cell responses to epidermal growth factor receptor pathway inhibitors. Cancer Biol Ther 2008; 7: 557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nyati MK, Morgan MA, Feng FY et al . Integration of EGFR inhibitors with radiochemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baumann M, Krause M, Dikomey E et al . EGFR‐targeted anti‐cancer drugs in radiotherapy: preclinical evaluation of mechanisms. Radiother Oncol 2007; 83: 238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zips D, Krause M, Yaromina A et al . Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors for radiotherapy: biological rationale and preclinical results. J Pharm Pharmacol 2008; 60: 1019–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ciardiello F, Bianco R, Caputo R et al . Antitumor activity of ZD6474, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in human cancer cells with acquired resistance to antiepidermal growth factor receptor therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 784–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chinnaiyan P, Huang S, Vallabhaneni G et al . Mechanisms of enhanced radiation response following epidermal growth factor receptor signaling inhibition by erlotinib (Tarceva). Cancer Res 2005; 65: 3328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harari PM, Huang SM. Modulation of molecular targets to enhance radiation. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6: 323–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scaltriti M, Baselga J. The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway: a model for targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 5268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baselga J, Cortes J. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway inhibitors. Cancer Chemother Biol Response Modif 2005; 22: 205–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baselga J. Why the epidermal growth factor receptor? The rationale for cancer therapy. Oncologist 2002; 7 (Suppl. 4): 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McIlwrath A, Vasey PA, Ross GM et al . Cell cycle arrests and radiosensitivity of human tumor cell lines: dependence on wild‐Type p53 for radiosensitivity. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 3718–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williams JR, Zhang Y, Zhou H et al . Little, Genotype‐dependent radiosensitivity: clonogenic survival, apoptosis and cell‐cycle redistribution. Int J Radiat Biol 2008; 84: 151–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaushal N, Bansal MP. Inhibition of CDC2/Cyclin B1 in response to selenium‐induced oxidative stress during spermatogenesis: potential role of Cdc25c and p21. Mol Cell Biochem 2007; 298: 139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mi Q, Kim S, Hwang BY et al . Silvestrol regulates G2/M checkpoint genes independent of p53 activity. Anticancer Res 2006; 26: 3349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen YL, Lin SZ, Chang JY et al . In vitro and in vivo studies of a novel potential anticancer agent of isochaihulactone on human lung cancer A549 cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2006; 72: 308–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang KL, Kung ML, Chow NH et al . Genistein arrests hepatoma cells at G2/M phase: involvement of ATM activation and upregulation of p21waf1/cip1 and Wee1. Biochem Pharmacol 2004; 67: 717–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ando T, Kawabe T, Ohara H et al . Involvement of the interaction between p21 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen for the maintenance of G2/M arrest after DNA damage. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 42 971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Iliakis G, Wang H, Perrault AR et al . Mechanisms of DNA double strand break repair and chromosome aberration formation. Cytogenet Genome Res 2004; 104: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gastaldo J, Viau M, Bencokova Z et al . Lead contamination results in late and slowly repairable DNA double‐strand breaks and impacts upon the ATM‐dependent signaling pathways. Toxicol Lett 2007; 173: 201–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Short SC, Bourne S, Martindale C et al . DNA damage responses at low radiation doses. Radiat Res 2005; 164: 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chin C, Bae JH, Kim MJ et al . Radiosensitization by targeting radioresistance‐related genes with protein kinase A inhibitor in radioresistant cancer cells. Exp Mol Med 2005; 37 (6): 608–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carlomagno F, Burnet NG, Turesson I et al . Comparison of DNA repair protein expression and activities between human fibroblast cell lines with different radiosensitivities. Int J Cancer 2000; 85: 845–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stea B, Falsey R, Kislin K et al . Time and dose‐dependent radiosensitization of the glioblastoma multiforme U251 cells by the EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 (‘Iressa’). Cancer Lett 2003; 202: 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Andersson U, Johansson D, Behnam‐Motlagh P et al . Treatment schedule is of importance when gefitinib is combined with irradiation of glioma and endothelial cells in vitro. Acta Oncol 2007; 46: 951–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]