Abstract

Some immigrants and refugees might be more vulnerable than other groups to pandemic influenza because of preexisting health and social disparities, migration history, and living conditions in the United States.

Vulnerable populations and their service providers need information to overcome limited resources, inaccessible health services, limited English proficiency and foreign language barriers, cross-cultural misunderstanding, and inexperience applying recommended guidelines. To increase the utility of guidelines, we searched the literature, synthesized relevant findings, and examined their implications for vulnerable populations and stakeholders.

Here we summarize advice from an expert panel of public health scientists and service program managers who attended a meeting convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 1 and 2, 2008, in Atlanta, Georgia.

IN APPLYING PREPARATION and response guidelines for pandemic influenza, providers of health and social services to immigrants and refugees must help them to overcome obstacles typical of migration histories and circumstances in the United States. As defined in US immigration law, an immigrant is a person who enters the country as a lawful permanent resident or who is granted that status after arrival.1 A refugee in the United States is a person living outside his or her country of permanent allegiance (nationality) and unable or unwilling to return there because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution arising from the refugee's race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion. Although the criteria for assigning asylee and refugee status are similar, most asylees apply for and acquire legal status after entering the United States, and most refugees negotiate the process before entry.

Foreign-born persons composed less than 5% of the US population in 1970 and 12% in 2005; they are projected to reach 15% in 2015. In 2005, of the approximately 37.4 million foreign-born persons in the United States, 31% were naturalized citizens, 30% were unauthorized migrants, 28% were legal permanent residents, 7% were refugees who arrived after 1980, and 3% were temporary legal residents.2 Compared with persons born in the United States, the foreign born are more likely to live in poverty,3 less likely to have a high school diploma,4 and less likely to have health care coverage.5 Although the relative disadvantage varies by nativity and immigration status among foreign-born cohorts,4,6,7 access to care barriers are most severe for undocumented persons. These individuals may avoid contact with public officials because of fear of detention and deportation; this leads to higher risk of adverse consequences of pandemic influenza than is faced by citizens and by other immigrants and refugees.2,8–11

We describe the implications of available guidance on community mitigation and related strategies12–29 for these vulnerable populations and their stakeholders and provide advice from an expert panel of public health scientists and service program managers convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on May 1 and 2, 2008, in Atlanta, Georgia. Their advice is tailored to the interests of public health practitioners and service agencies addressing the special needs and circumstances of immigrants and refugees living in the United States.

DETERMINANTS OF PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE

The prepandemic physical condition and mental health status of individuals are important determinants of need and capabilities. Immigrants' overall health status begins to resemble that of US-born persons as duration of US residence increases.30 Foreign-born persons tend to have higher prevalence of diabetes, certain infections, and occupational injuries but lower all-cause mortality and prevalence of circulatory diseases, overweight and obesity, and certain cancers than do US-born residents of the same race/ethnicity.31–33

Some health indicators suggest increased vulnerability to infectious diseases and perhaps to pandemic influenza among some subgroups of foreign-born persons, including unauthorized immigrants. Compared with the native born, some foreign-born persons experience lower rates of certain routine immunizations6; lower utilization of preventive care34; significantly higher rates of certain infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis31–33; and, among unauthorized or undocumented immigrants, greater delays in seeking treatment of some infectious diseases.31–33

Regardless of visa status, the challenges of readjusting to a new country, finding employment, and learning a new language contribute to high stress levels and unique mental health needs. Refugees and asylees often arrive with a history of trauma, loss of social support, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, or anxiety. These negative psychological states can be barriers to accurate personal risk assessment and initiation or maintenance of precautionary practices.35–37

Migration Status and Service Access

Refugees are resettled in the United States through federally sponsored programs that provide medical and monetary benefits for a specific period, subject to available funding.38 Single adults and married couples without children receive these benefits for 8 months from date of entry into the country. Families with children who are 18 years or younger might qualify for additional benefits, including temporary assistance for needy families and Medicaid for up to 5 years. Although immigrants who enter as legal permanent residents do not qualify for the majority of public benefits until after 5 years of legal residency, the State Children's Health Insurance Program, reauthorized in February 2009, enables increased access to health care for legal immigrant children and pregnant women.

Immigrants who enter the United States without legal status do not qualify for public benefits, except for certain services from the Department of Agriculture's Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Refugees are assisted by resettlement agencies with English-speaking professionals well versed in accessing health and social benefits, whereas immigrants are dependent on their families and neighborhood agencies and may be limited by language, unfamiliarity with available services, and difficulty in navigating the health care and social services systems.

Medical Screening and Other Health Services

Before coming to the United States, legal immigrants and refugees must have physical and mental examinations by US Department of State physicians to identify inadmissible health-related conditions. The CDC provides technical instructions to overseas physicians conducting these examinations and periodically revises the regulations that define inadmissible conditions to prevent disease threats to the United States.39 Pandemic influenza is included in the communicable diseases of public health significance as of October 6, 2008.

Applicants who meet all requirements for documentation of refugee status are eligible for Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) program services and assistance.38 Asylees Cuban and Haitian entrants, certified victims of trafficking and other crimes, and unaccompanied alien children are eligible for ORR services. ORR provides funding, and state governments administer refugee programs to ensure that all eligible clients receive medical screening services soon after they arrive in the United States or when they receive eligibility status. States often provide medical screening programs through agreements with departments of public health or through contracts with other health providers in coordination with voluntary resettlement agencies. In states without governmental involvement in medical screening, these agencies procure screening services from private clinics or physicians.

Voluntary resettlement agencies, based in local communities, receive support from the Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration and ensure that refugees receive transportation, interpretation, and translation services related to medical screening. Government and private agencies and the services they provide to refugees, asylees, and other legal immigrants are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Public and Private Agencies That Provide Services To Refugees, Asylees, and Other Legal Immigrants in the United States

| Agency | Services |

| Department of Health and Human Services | |

| Agency for Children and Families, Office of Refugee Resettlement | Provides funds to state governments and private-sector nonprofit agencies to support refugees' progress toward economic self-sufficiency, English language acquisition, and finally integration into their community |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine | Periodically revises the regulations that define inadmissible conditions to prevent disease threats to the United States |

| Provides technical instructions to overseas physicians under contract with the Department of State to conduct physical and mental examinations of legal immigrants and refugees to identify inadmissible health-related conditions before the person enters the United States | |

| Provides guidance to Office of Refugee Resettlement and their grantees, state agencies that provide medical screening upon arrival | |

| Department of State | |

| Bureau for Population, Refugees and Migration | Provides assistance to refugees in other countries |

| Provides grants to voluntary agencies | |

| State governmental agencies designated by governor to serve as refugee coordinators | Receive funds from the Office of Refugee Resettlement |

| Provide funds and oversee public and private agencies that deliver resettlement services to refugees | |

| Offices in most states are located in agencies that provide social and employment services | |

| Public health agencies provide medical screening | |

| Private voluntary agencies | Receive grants from the Department of State to resettle refugees admitted to US communities through affiliate agencies or branches |

| Grant funds support processing, reception, and placement of refugees |

Vulnerability to Pandemic Influenza

Although general statements about the social determinants of vulnerability to pandemic influenza and its consequences in migrant populations can make them seem homogeneous, immigrants and refugees are heterogeneous populations with differing risks for pandemic influenza and needs for preventive measures. Such needs vary between successive migrant cohorts from different parts of the world.

In general, causes of immigrants' and refugees' vulnerability to pandemic influenza include any combination of the following factors: high prevalence of chronic conditions that increase the risk for complications and death from influenza30; low rates of seasonal influenza vaccine coverage40,41; limited access to and use of preventive medical care42; social, linguistic, economic, and housing barriers to adoption and uptake of vaccines, antiviral agents, and nonpharmaceutical interventions promoted by public health officials40,41; cultural, religious, and traditional health care practices unfamiliar to Western-trained professionals40,41,43,44; and high risk of exposure to a pandemic strain of influenza through social networks extending beyond the United States. Disparities in preparedness, response, and recovery can be compounded by variations in exposure to pandemic influenza viruses, susceptibility after exposure, and treatment.45

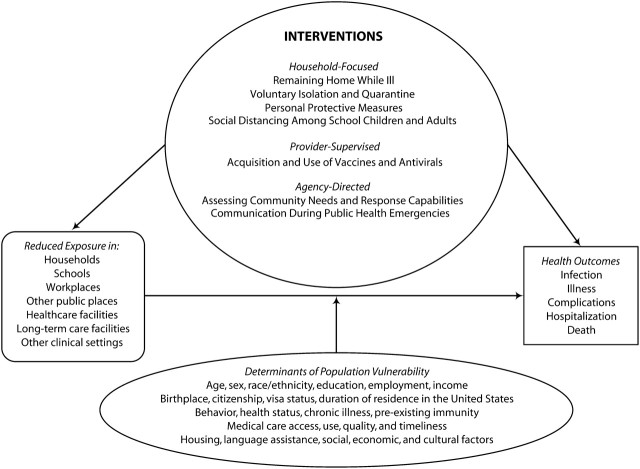

PARTNERS MEETING

To determine the utility of published guidelines, we searched the scientific literature, synthesized relevant findings, and examined their implications for vulnerable populations and their stakeholders. Guided by a conceptual framework (Figure 1), we selected keywords (immigrant, immigration, foreign born, refugee, influenza, and pandemic) to search the National Library of Medicine's PubMed online database and Internet sites (including http://www.pandemicflu.gov) for guidance documents, biomedical journal citations, and abstracts of articles published by July 31, 2008. We reviewed titles, abstracts, and reference lists of citations turned up by our search and assessed the available information for accuracy, source credibility, potential utility, and relevance to the information needs of immigrants, refugees, and related stakeholders.

FIGURE 1.

Logic framework depicting the conceptual approach to pandemic influenza preparedness and response among immigrants and refugees.

Note. Circle=interventions; ellipse=population attributes; rounded rectangle=intermediate outcomes; rectangle=adverse health outcomes; arrow=causal influences.

The May 2008 partners meeting further contributed to our efforts to tailor our report to the needs of our intended audience. The meeting participants, including the authors, represented a broad cross section of experts. The science and practice of pandemic influenza mitigation and the purpose, scope, content, and presentation of this article were discussed at the meeting.

We categorized possible interventions as household focused, provider supervised, or agency directed. For each pandemic-mitigating task or intervention prescribed in the published guidelines, we examined the implications for immigrants, refugees, and their service providers. We also examined the needs, obstacles, and potential solutions among the insights arising from the meeting and our research.

PARTNERS' ADVICE

Household-focused interventions depend on the preparation and active participation of immigrants and refugees in their homes, workplaces, and other settings. Professionals who deliver public health, health care, and emergency services also prescribe, dispense, and apply provider-supervised interventions. Agency-directed interventions include monitoring to detect and respond to influenza clusters and, during a crisis, communicating effectively with public officials, responders, and laypersons about preparedness for and response to pandemic influenza.

Household-Focused Interventions

For pandemic-mitigating interventions to be successful, all households, including those of immigrants and refugees, will need to participate in planning, practicing, and acting effectively, with support and material assistance from service providers.

Remaining home while ill.

Except for skilled migrants entering on H-1 visas, most migrants and refugees work in low-wage jobs that lack benefits (e.g., paid sick leave)46–49; therefore, they often choose to work while ill because of the real or perceived risk of losing pay or employment. Like other workers, they need information regarding influenza's symptoms and how to obtain medical care. Like other employers, employers of immigrants and refugees should consider instituting liberal leave policies, telecommuting arrangements, job security guarantees, and special pay incentives, even if government assistance is unavailable (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Advice From Expert Panelists at External Partners Meeting on Influenza Pandemics, May 1–2, 2008, Atlanta, GA

| Interventions | Advice for Public Officials, Practitioners, Service Agencies, Employers, and Other Respondents |

| Staying at home while ill | Provide immigrants and refugees with information on recognizing influenza symptoms and getting advice about medical care |

| Encourage all employers, including those with high proportions of immigrants and refugees among their workforce, to consider instituting liberal leave policies, telecommuting arrangements, job security guarantees, and special pay incentives, even in the absence of government assistance | |

| Voluntary isolation and quarantine | Protect immigrants and refugees, especially those who live in households where voluntary isolation or quarantine is in effect, from social stigma of being a presumed source of pandemic influenza in the community |

| Engage faith- and community-based organizations, cultural brokers, and other community messengers to work with families on how to best isolate and quarantine ill persons and to help them cope with any related social stigma | |

| Personal protective measures | Emphasize cultural competence and the importance of connections between religious and cultural beliefs and health practices among immigrants and refugees |

| Work with providers of services to immigrants and refugees to address availability, out-of-pocket costs, correct fit and use, and sanitary disposal of contaminated face masks and respirators | |

| Consider the feasibility of encouraging trusted members of immigrant and refugee communities to model and promote optimal cough etiquette and hand-hygiene practices throughout the year | |

| Consider the feasibility of encouraging and subsidizing use of inexpensive, readily available, and effective methods for disinfecting environmental surfaces contaminated with influenza virus inside homes | |

| Social distancing among school-aged children and adults | Mobilize cultural and religious incentives to motivate adherence to school-related and communitywide social distancing |

| Consider means to continue providing meals to vulnerable children at school during a pandemic (e.g., rotating schedules to avoid high person-density, optimizing distancing among children, enhancing ventilation, and providing convenient hand-hygiene facilities); finding alternative sources of these services also should be a high priority when schools are closed during a pandemic | |

| Acquisition and use of vaccines and antivirals | Encourage employers in industries in which immigrants and refugees are likely to be overrepresenteda to consider the needs of all employees, including the special needs of immigrants and refugees |

| Consider distribution in easily accessible community centers close to the homes of persons in isolation or quarantine, as well as using workplaces as supplementary points of distribution | |

| Give special attention to US–Mexico border region and to states with the largest immigrant and refugee populationsb | |

| Ensure that all population subsets, including immigrants and refugees, receive information on the rationale for priority groups as well as on location and timing of distribution of vaccines and antiviral drugs | |

| Ensure that distribution sites are easily accessible by all segments of the population | |

| Work with purchasers, manufacturers, distributors, doctors, dispensers, and other participants in the commercial drug distribution chain to ensure that immigrants and refugees who do not qualify for priority through occupation or age have fair and equitable access to antiviral agents during a influenza pandemic | |

| Investigate and apply lessons learned from the Women, Infants, and Children nutritional supplement program model, which provides benefits without asking about immigration status | |

| Assessment of community needs and response capabilities | Work with immigrants, refugees, and their service providers to collect essential group- or person-level data that balance the need for information to guide outreach programs with efforts to protect vulnerable populations from social stigma and discrimination |

| Communication during public health emergencies | Address the unique concerns of immigrant and refugee communities when developing messages that outline public health recommendations before or during an influenza outbreak or pandemic |

| Encourage use of bilingual, bicultural community health workers, develop low-literacy and culturally appropriate health education materials, and use all forms of media, including print, audio, audiovisual, and podcasts | |

| Engaging target audiences | Adhere to key principles of community engagement to promote effective and successful influenza preparedness and response among immigrants and refugees |

| Key principles require that communicators engage members of the target audiences in developing and delivering messages through existing trusted, effective channelsc; include appropriate institutions and sources of authority in those communitiesd; build credibility and trust by first addressing community concerns, including those that might not be directly related to pandemic influenza preparednesse; encourage and require cultural competence among providers who serve immigrants and refugeesf; integrate concern for pandemic influenza preparedness with concern for everyday activities and problems of target audiencesg; evaluate needs and vulnerabilities and use assets in positive approaches to overcome barriers to preparedness and response and to achieve desired health outcomesh |

For example, construction, farmers' markets, retail sales, hospitality, restaurants and other food-serving establishments, child care, and poultry and meat packing.

Details of preparedness and response in the US–Mexico border region are beyond the scope of this report.

For example, Vietnamese radio stations or Korean Church newsletters.

For example, church, community center, shaman, religious, or other acknowledged community leader.

For example, cigarette smoking among some groups of Asian Americans.

Indicators of cultural competency include a diverse staff, providers or translators who speak the clients' language, and signage and instructional literature in the clients' language and consistent with their cultural norms.

For example, encouraging religious leaders to include concerns about pandemic influenza preparedness in their teachings.

For example, encouraging efforts to increase the percentage of persons who follow good hand-washing practices rather than efforts to decrease the percentage of persons who do not.

Voluntary isolation and quarantine.

Immigrants and refugees sometimes live in crowded homes with their extended families.50–53 Implementing isolation and quarantine, which should be voluntary, might be difficult in a crowded household, especially when cultural or religious practices encourage physical closeness within families (e.g., praying and eating meals together). In addition, immigrants and refugees who live in households where isolation or quarantine is in effect might have to contend with the social stigma of being a presumed source of pandemic influenza in the community.54,55 Stakeholders should engage faith- and community-based organizations, cultural brokers, and other community leaders to work with families on how best to isolate and quarantine influenza patients and to help them cope with any related social stigma.

Personal protective measures.

The CDC recommends that persons who cannot avoid close contact with an infectious person (e.g., an at-home caregiver of a family member with a respiratory infection) consider using respirators.14 Immigrants and refugees sometimes have experience with face masks and respirators in occupations where they are used to control dust-related diseases (e.g., construction, mining, and grain agriculture) or to prevent respiratory infection during outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome and tuberculosis.54–56 In some Asian countries, wearing masks during respiratory illness is such a common practice that it is not stigmatized.57,58 For certain populations, however, experiences with stigma and discrimination associated with wearing face masks and respirators in public might act as barriers to their use.54–56 Moreover, cultural norms in their countries of origin (e.g., religious headwear), experiences in refugee camps overseas, and practical barriers to acquiring and correctly using face masks and respirators (e.g., fit testing) require providers to develop targeted educational materials for these populations. Cultural competency and understanding of connections between religious or cultural beliefs and health practices are critical in public health preparedness and response.

Stakeholders encourage public health practitioners to work with service providers to address availability, out-of-pocket costs, and correct fit and use of face masks and respirators, as well as sanitary disposal when they become contaminated. They encourage trusted community members to model and promote optimal cough etiquette and hand hygiene throughout the year. Practitioners should also encourage and subsidize use of inexpensive, readily available, and effective methods for cleaning and disinfecting environmental surfaces contaminated with influenza virus inside homes (e.g., bedside tables or lavatory surfaces). Morever, the use of vaccines, antivirals, and some personal protective devices (e.g., respirators) require supervision by health care providers to be effective

Social distancing among school children and adults.

Countries of origin may have different school attendance laws, and immigrant children may attend religious schools that present barriers to adherence to local laws and policies regarding school attendance while ill. Stakeholders encourage officials and communities to use cultural and religious incentives to motivate adherence to school-related social distancing. Stakeholders should also recognize that schools are often both community gathering places and providers of breakfast and lunch for immigrant and refugee children (Table 2).

Immigrants and refugees from war-torn regions (e.g., Iraq or Sudan) might be accustomed to avoiding crowded areas to reduce their risk for injury from bomb blasts. Transfer of crowd-avoidance behavior learned overseas to influenza-avoidance behavior in the United States is unknown but should be explored. By contrast, cultural or religious traditions requiring attendance at crowded public gatherings (e.g., funerals and festivals) might present barriers to cooperation with such interventions among new immigrants and refugees. The feasibility and practical implications of postponing such events until after pandemic influenza risk has passed should be explored with religious and secular leaders.

Provider-Supervised Interventions

To prepare for and effectively respond to pandemic influenza, providers of health care, emergency, and other services who operate fixed or mobile clinical facilities with community outreach capabilities should work closely with immigrants, refugees, and the agencies serving them.

Immigrants and refugees, like other residents, will be assigned priority for receiving vaccines or antivirals before or during a pandemic on the basis of occupation, work setting, and other eligibility criteria. They might be underrepresented in high-priority job tiers for which US citizenship or a permanent residence visa is a requirement. Conversely, immigrants, refugees, and their health care providers are likely to be well represented among caregivers in different sectors of the heath care workforce, including home health care providers, nurses, and resident physicians in training, and these workers will also be assigned varying priority levels.

Immigrants and refugees are overrepresented in certain industries—construction, farmers' markets, retail sales, hospitality, restaurants and other food-serving establishments, child care, and poultry and meat packing—and compose most of the workforce of certain large employers in the United States. Ensuring that all population groups receive information on the rationale for priority groups as well as information on location and timing of distribution of vaccines and antiviral drugs is a critical aspect of planning. Planners should also ensure that distribution sites are easily accessible by all population segments. The advantages and disadvantages of having points of distribution in easily accessible community centers close to the homes of persons in isolation or quarantine should be considered; workplaces could serve as supplementary dispensing points. In their countries of origin, immigrants and refugees may have received vaccines, antivirals, and other health care supplies from pharmacies; therefore, the role of pharmacies in distributing vaccines and antiviral drugs during a pandemic should be explored.

Through effective communication, public health officials, employers, pharmacists, health care providers, and others involved in distributing vaccines should ensure that immigrants, refugees, and their service providers are aware of the priority tier to which they belong and how they can receive vaccination. Participants in the commercial drug distribution chain should work with immigrants, refugees, and stakeholders to ensure that they have fair and equitable access to antiviral agents during an influenza pandemic. Voluntary resettlement agencies, with funding from federal agencies and philanthropy, might serve as links to refugee communities. Obstacles to accessing vaccines and antiviral agents arising from immigration status should be removed. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children allows qualifying clients to access benefits without revealing immigration status; public health officials should consider this model. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination among immigrants and refugees can be a key way to increase acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine.

Agency-Directed Interventions

In 2008, the World Health Organization issued guidelines for humanitarian agencies to use when planning for pandemic influenza preparedness and mitigation among refugee and displaced populations.28 The organization recommended that each agency serving such populations develop a pandemic preparedness plan linked to national and subnational plans within jurisdictions where refugees and displaced populations live. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association of County and City Health Officials, and CDC have issued similar guidance for state and local health departments whose activities address preparedness and response to pandemic influenza, including activities that help immigrants, refugees, and displaced persons.13,25

Assessing community needs and response capabilities.

Surveillance systems for seasonal influenza do not collect information about immigrants and refugees as a subset of the US population.59 Thus, planners and emergency responders might be unable to ascertain the pandemic's course and impact on immigrants and refugees separately from other subsets of the US population. Administrative systems that collect person-level service data from immigrants and refugees might be modifiable to fill this information gap.

Collecting such data might have both advantages and disadvantages. Advantages include greater ability to identify a population's special needs and more effective targeting of outreach programs. Disadvantages include lower use of services because of social stigma and fear of being identified and deported by authorities. Agencies that assess community needs and operate surveillance systems should work with immigrants, refugees, and their service providers to collect essential group-level or person-level data such as birthplace, language, literacy, education, income, and employment. The need for information to guide outreach programs should be balanced with efforts to protect vulnerable populations from social stigma and discrimination. Federal, state, and local health policies, laws, and regulations protecting privacy and confidentiality should inform data collection and use.

Communication during public health emergencies.

Emergency communication and education objectives during a severe influenza event are similar for different populations. However, immigrants and refugees might have specific beliefs, experiences, and cultural orientations that should be considered,60,61 such as distrust of public health officials or their messages about influenza. In addition, they might have more fear during a severe influenza outbreak tied to their immigration experience, adaptation to a new sociocultural environment, past discrimination, or previous encounters with government or medical institutions.61 Therefore, during a crisis, communicators might need to modify planning and communicating approaches in these communities to address unique concerns.

In certain countries, experiences with severe acute respiratory syndrome containment and HIV risk reduction have demonstrated that persons who are perceived by the public to be typical of infected persons are usually at greater risk for experiencing stigma and discrimination during infectious disease outbreaks.62 This risk is greater if media stories repeatedly associate the origin of an outbreak with specific or well-defined ethnic, geographic, or cultural profiles.63 Persons whose culture or country of origin are identified as the source of a pandemic episode might fear these psychosocial outcomes as much as the physical consequences of the illness.63–65 Stigma and fear have critical implications for managing infectious disease emergencies: they can encourage illness concealment, delay early detection and treatment, increase distrust of health authorities, lower the likelihood of compliance, and prolong recovery.63

Other, broader concerns and cultural beliefs among immigrants and refugees can be barriers to the adoption of certain health-protective behaviors during an influenza crisis. Undocumented immigrants might worry that their immigration status precludes them from receiving appropriate medical care and that coming forward could have negative consequences, including discrimination or deportation.61,64 Early communications and public education outreach that openly address these challenges before and during an influenza crisis may avert stigmatization, discrimination, and fear of reprisals related to immigration or refugee status.

Populations filter messages and risk information through their already existing belief and value systems. Thus, maximizing public health communication effectiveness for immigrants and refugees can depend on whether health messages reflect fundamental cultural values. Values most likely to be influential include family and community ties (familism), equity or fairness, and the definition of self in relation to others.66–68 For example, identifying oneself in reference to relationships with others (i.e., interdependent self-construal) is often a dominant cultural orientation within Asian American and Hispanic American communities.67,69 Recent research demonstrates that, depending on country of origin, emergency messages intended to motivate precautionary behaviors might be more effective for immigrant and refugee communities if they are framed as protection of loved ones rather than only of the individual.61 More research is needed that explicitly evaluates the effectiveness of different multicultural communication strategies.70

Public health officials and other stakeholders should address immigrant and refugee communities' unique concerns when developing messages that outline public health recommendations before or during an influenza outbreak or pandemic. They should encourage use of bilingual, bicultural community health workers, develop low-literacy and culturally appropriate health education materials, and use all forms of ethnic and mainstream media, including print, audio, audiovisual, and podcasts.

Engaging target audiences.

Adherence to key principles of community engagement promotes effective and successful influenza preparedness and response among immigrants and refugees. Language, literacy, and cultural appropriateness of local public health education and control efforts are important in areas where new arrivals from uncommon sources of migration (e.g., Nepal and Bhutan) are beginning to settle.

Several key principles should guide public health practitioners and other officials: (1) engage members of the target audiences in developing and delivering messages through existing trusted, effective channels; (2) include appropriate institutions and sources of authority in affected communities (e.g., churches, community centers, shamans, and religious or other acknowledged community leaders); (3) address community concerns, even those not directly related to pandemic influenza preparedness, to build credibility and trust; (4) strive to improve the cultural competence of providers who serve immigrants and refugees; (5) integrate pandemic influenza preparedness into everyday activities to the extent possible; and (6) use positive approaches when assessing needs and vulnerabilities and when employing community assets to overcome barriers to preparedness and response.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Jamila Rashid (facilitator) and Sarah Berry (note taker) during the session about immigrants and refugees at the external partners meeting on May 1 to 2, 2008, in Atlanta, Georgia. We acknowledge contributions to the recommendations from the following meeting participants: Adedeji Adefuye, Jenny Aguirre, Rubis Castro, Sara Chute, Eric Cleghorn, Pamela Collins, Ken Graham, Laura Hardcastle, Natalie Hernandez, Eric Kamba, Tom Keenan, Harriet Kuhr, Maureen Lichtveld, Loc Nguyen, David Oeser, Laura Smith, Mao Thao, Monica Vargas, and Emad Yanni. We are grateful to Walter W. Williams, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's associate director for minority health and director of the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities, for his review of the manuscript and to Nan T. Waters and Cheryll K. Smith-Akin for editorial assistance.

Human Participation Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because no research involving human subjects was conducted.

References

- 1.Loue S, Bunce A. The assessment of immigration status in health research. Vital Health Stat 2. 1999;No. 127:1–115. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_127.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2008. [PubMed]

- 2.Hoefer M, Rytina N, Campbell C. Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2005. Available at: http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/ILL_PE_2005.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 3.US Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. Annual social and economic supplement, 2004. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/foreign/ppl-176/tab02-12.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2009.

- 4.US Census Bureau. Educational attainment in the United States: 2007. Available at: http://blueprod.ssd.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p20-560.pdf. Accessed on February 17, 2009.

- 5.US Census Bureau. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p60-235.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2009.

- 6.Kandula NR, Kersey M, Lurie N. Assuring the health of immigrants: what the leading health indicators tell us. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:357–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidley AD. Profile of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2000. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2001. Current Population Reports, Series P23-206. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/p23-206.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan TC, Krishel SJ, Bramwell KJ, Clark RF. Survey of illegal immigrants seen in an emergency department. West J Med. 1996;164:212–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeToledo JC, Palmerola RA, Lowe MR. Health care of illegal immigrants post 9-11. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:764–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dwyer J. Illegal immigrants, health care, and social responsibility. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliot S. Staying within the lines: the question of post-stabilization treatment for illegal immigrants under Emergency Medicaid. J Contemp Health Law Policy. 2007;24:149–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton M. Administration for Children and Families, Office of Refugee Resettlement. State letter 06-10. Instructions to states to amend state plans with emergency operational planning for pandemic influenza. March 17, 2006. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/policy/sl06-10.htm. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 13.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). At-risk populations and pandemic influenza: planning guidance for state, territorial, tribal, and local health departments. June 2008. Available at: http://www.astho.org/index.php?template=at_risk_population_project.html. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance on planning for the use of surgical masks and respirators in health care settings during an influenza pandemic. October 2006. Available at: http://pandemicflu.gov/plan/healthcare/maskguidancehc.html. Accessed August 18, 2008.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance on environmental management of pandemic influenza virus. Available at: http://www.pandemicflu.gov/plan/healthcare/influenzaguidance.html. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC influenza pandemic operation plan (OPLAN). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic/cdcplan.htm. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 17.Holmberg SD, Layton CM, Ghneim GS, Wagener DK. State plans for containment of pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1414–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson AJ, Moore ZS, Edelson PJ, et al. Household responses to school closure resulting from outbreak of influenza B, North Carolina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1024–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meltzer MI. Pandemic influenza, reopening schools, and returning to work. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:509–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidance on preparing workplaces for an influenza pandemic—OSHA. 2007. Publication 3327-02N. Available at: http://www.osha.gov/Publications/influenza_pandemic.html. Accessed August 21, 2008.

- 21.Osterholm MT. Preparing for the next pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1839–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services. State and local government planning & response activities. Available at: http://www.pandemicflu.gov/plan/states/index.html. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS pandemic influenza plan. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/pandemicflu/plan/part1.html. Accessed August 11, 2008.

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services. Planning checklists. Available at: http://www.pandemicflu.gov/plan/checklists.html. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services. Community strategy for pandemic influenza mitigation. February 2007. Available at: http://www.pandemicflu.gov/plan/community/commitigation.html. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 26.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Homeland Security. Guidance on allocating and targeting pandemic influenza vaccine. July 2008. Available at: http://www.pandemicflu.gov/vaccine/allocationguidance.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2008.

- 27.World Health Organization. WHO global influenza preparedness plan: the role of WHO and recommendations for national measures before and during pandemics. September 2006. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/CDS_GIP_2006_5c.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- 28.World Health Organization. Pandemic influenza preparedness and mitigation in refugee and displaced populations: WHO guidelines for humanitarian agencies. 2nd ed. 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/diseasecontrol_emergencies/HSE_EPR_DCE_2008_3rweb.pdf. Accesses August 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu JT, Riley S, Fraser C, Leung GM. Reducing the impact of the next influenza pandemic using household-based public health interventions. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Argeseanu Cunningham S, Ruben JD, Venkat Narayan KM. Health of foreign-born people in the United States: a review. Health Place. 2008;14:623–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett ED, Walker PF. Role of immigrants and migrants in emerging infectious diseases. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:1447–1458, xi–xii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cain KP, Benoit SR, Winston CA, MacKenzie WR. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Achkar JM, Sherpa T, Cohen HW, Holtzman RS. Differences in clinical presentation among persons with pulmonary tuberculosis: a comparison of documented and undocumented foreign-born versus US-born persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1277–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu KT, Borders TF. Does being an immigrant make a difference in seeking physician services? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker MH, Maiman LA. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med Care. 1975;13:10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia K, Mann T. From ‘I Wish’ to ‘I Will’: social-cognitive predictors of behavioral intentions. J Health Psychol. 2003;8:347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychol Bull. 2003;129:10–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Office of Refugee Resettlement. Health. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/benefits/health.htm. Updated February 24, 2009. Accessed April 30, 2009.

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medical examinations of aliens—revisions to medical screening process. October 2008. Available at: http://www.regulations.gov/fdmspublic/component/main?main=DocumentDetail&o=0900006480739171. Accessed October 6, 2008.

- 40.Coady MH, Galea S, Blaney S, Ompad DC, Sisco S, Vlahov D. Project VIVA: a multilevel community-based intervention to increase influenza vaccination rates among hard-to-reach populations in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1314–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vlahov D, Coady MH, Ompad DC, Galea S. Strategies for improving influenza immunization rates among hard-to-reach populations. J Urban Health. 2007;84:615–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pylypchuk Y, Hudson J. Immigrants and the use of preventive care in the United States. Health Econ. [Epub ahead of print August 22, 2008]. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/121385551/abstract. Accessed October 2, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Bradt DA, Drummond CM. Avian influenza pandemic threat and health systems response. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18:430–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas JK, Noppenberger J. Avian influenza: a review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blumenshine P, Reingold A, Egerter S, Mockenhaupt R, Braveman P, Marks J. Pandemic influenza planning in the United States from a health disparities perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:709–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lowell BL, Jing Z. Unauthorized workers and immigration reform: what can we ascertain from employers? Int Migr Rev. 1994;28:427–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powers MG, Seltzer W, Shi J. Gender differences in the occupational status of undocumented immigrants in the United States: experience before and after legalization. Int Migr Rev. 1998;32:1015–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powers MG, Seltzer W. Occupational status and mobility among undocumented immigrants by gender. Int Migr Rev. 1998;32:21–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rivera-Batiz FL. Undocumented workers in the labor market: an analysis of the earnings of legal and illegal Mexican immigrants in the United States. J Popul Econ. 1999;12:91–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunn JR, Hayes MV, Hulchanski JD, Hwang SW, Potvin L. Housing as a socio-economic determinant of health: findings of a national needs, gaps and opportunities assessment. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(suppl 3):S11–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fennelly K. Listening to the experts: provider recommendations on the health needs of immigrants and refugees. J Cult Divers. 2006;13:190–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myers D, Lee SW. Immigrant trajectories into homeownership: a temporal analysis of residential assimilation. Int Migr Rev. 1998;32:593–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ponizovsky A, Perl E. Does supported housing protect recent immigrants from psychological distress? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1997;43:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacDougall H. Toronto's Health Department in action: influenza in 1918 and SARS in 2003. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62:56–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Person B, Sy F, Holton K, Govert B, Liang A. Fear and stigma: the epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:358–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reynolds MG, Anh BH, Thu VH, et al. Factors associated with nosocomial SARS-CoV transmission among healthcare workers in Hanoi, Vietnam, 2003. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lau JT, Kim JH, Tsui HY, Griffiths S. Perceptions related to bird-to-human avian influenza, influenza vaccination, and use of face mask. Infection. 2008. Sep 15 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lau JT, Kim JH, Tsui HY, Griffiths S. Anticipated and current preventive behaviors in response to an anticipated human-to-human H5N1 epidemic in the Hong Kong Chinese general population. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overview of influenza surveillance in the United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivity.htm. Updated April 17, 2009. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 60.Andrulis DP, Siddiqui NJ, Gantner JL. Preparing racially and ethnically diverse communities for public health emergencies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1269–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:439–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee S, Chan L, Chau A, Kwok K, Kleinman A. The experience of SARS-related stigma at Amoy Gardens. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2038–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barrett R, Brown PJ. Stigma in the time of influenza: social and institutional responses to pandemic emergencies. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 1):S34–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mathew AB, Kelly K. Disaster Preparedness in Urban Immigrant Communities: Lessons Learned From Recent Catastrophic Events and Their Relevance to Latino and Asian Communities in Southern California. Los Angeles, CA: Rivera Policy Institute, University of Southern California; 2008. Available at: http://trpi.org/PDFs/DISASTER_REPORT_Final.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weiss MG. Stigma interventions and research for international health. Lancet. 2006;367:536–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pellow DN. Framing emerging environmental movement tactics: mobilizing consensus, demobilizing conflict. Sociol Forum. 1999;14:659–683. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Paez ND, Myers HF. Exploring the complexities of familism and acculturation: central constructs for people of Mexican origin. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39:61–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sjoberg L. Factors in risk perception. Risk Anal. 2000;20:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Institute of Medicine. Speaking of Health: Assessing Health Communication Strategies for Diverse Populations. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10018&page=1. Accessed August 22, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]