Abstract

Thoracic aortic calcium (TAC) has been associated with a higher prevalence of coronary arterial calcium (CAC). The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between TAC with both incident CAC and CAC progression in a cohort from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). MESA is a prospective cohort study of 6,814 participants free of clinical cardiovascular disease at entry who underwent non-contrast cardiac computed tomography scanning at baseline examination and at a 2 year follow up. We investigated the independent association between TAC and incident CAC among those without CAC at baseline and between TAC and CAC progression among those with CAC at baseline. The final study population consisted of 5,755 (84%) individuals (62±10 years, 48% males) who had a follow up CAC score an average of 2.4 years later. Incident CAC was significantly higher among those with TAC versus without TAC at baseline (11 per 100 person years versus 6 per 100 person years). Similarly, TAC was associated with a higher CAC change (p<0.0001) in those with some CAC at baseline. In demographic & follow-up duration adjusted analysis, TAC was associated with both incident CAC (RR 1.72; P < 0.0001) as well as with a greater CAC change (RR for 1st and 4th quartiles and 95% CI: RR 2.89; −3.16, 8.95; RR 24.21; 18.25, 30.18. In conclusion, TAC is associated with incidence and progression of CAC. Detection of TAC may improve risk stratification efforts. Future clinical outcomes studies are needed to support such approach.

Keywords: Thoracic aortic calcium, coronary arterial calcium, coronary disease progression, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

Introduction

Using a cohort from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), the purpose of this study was to assess the relation between thoracic aortic calcium (TAC) and both incident coronary arterial calcium (CAC) and the progression of coronary calcium. We hypothesized that the presence of TAC would help identify individuals with a baseline CAC score of zero who are more likely to develop new coronary calcium, as well as those with baseline CAC who are more likely to experience disease progression.

Methods

The MESA was initiated in July 2000 to investigate the prevalence, correlates, and progression of subclinical cardiovascular disease in individuals without known cardiovascular disease (1). This prospective cohort study includes 6814 women and men ages 45–84 years old recruited from six U.S. communities (Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Forsyth County, NC; Los Angeles County, CA; northern Manhattan, NY; and St. Paul, MN). There are 38% White (N=2624), 28% Black (N=1895), 22% Hispanic (N=1492), and 12% Chinese (N=803) individuals.

Medical history, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory data for the present study were taken from the first examination of the MESA cohort (July 2000 to August 2002). Information about age, gender, ethnicity, and medical history were obtained by questionnaires. Information regarding physical activity was collected at the baseline examination with a combination of self-administered and interviewer-administered questionnaires. Current smoking was defined as having smoked a cigarette in the last 30 days. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl or the use of hypoglycemic medication. Use of medications was based on clinic staff entry of prescribed medications.

Resting blood pressure was measured three times in the seated position using a Dinamap model Pro 100 automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Critikon, Tampa, Florida) and the average of the 2nd and 3rd readings was recorded. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or use of medication prescribed for hypertension. Body mass index was calculated from the equation weight (kg)/ height (m2). Total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured from blood samples obtained after a 12-hour fast. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated with the Friedewald equation.

After signing informed consent, all participants underwent 2 consecutive computed tomography scans for evaluation of CAC, which was quantified using the Agatston score. An ancillary study, supported by the National Institutes of Health, was performed to measure aortic and valvular calcium on the scans obtained for the MESA study. Three sites used an Imatron C-150XL CT scanner (GE-Imatron, San Francisco, CA), and three sites used a multi-detector CT scanner (4 slice).The method has been reported previously (2). A minimum of 35 contiguous images with a 2.5- or 3-mm slice thickness were obtained. Ascending and descending thoracic aortic calcium ranged from the lower edge of the pulmonary artery bifurcation to the cardiac apex (imaged on every study of coronary calcium) and were quantified by using the same lesion definition for coronary calcification. TAC values were not available for 2 individuals who were excluded.

All participants with both a baseline and a 2 year follow-up CT of the chest were included in the analysis. The presence of CAC was defined as an Agatston score >0. Progression of CAC was defined in 2 ways as previously described by Kronmal et al (3); incident CAC defined as detectable CAC at the follow-up examination (either examination 2 or 3) in a participant free of detectable CAC at examination 1 and change in CAC score in participants who had detectable CAC at examination 1.

For the primary analysis, participants were classified as those TAC = 0 and TAC > 0. Furthermore, those with TAC > 0, were further classified into quartiles according to increasing TAC scores. To assess bivariate associations between categorical classification of TAC and baseline risk factors, we used a chi-square test of independence (for categorical covariates) or an analysis of variance procedure (for continuous covariates).

Relative risk regression was used to model the probability of incident-detectable CAC among those free of CAC at examination 1. The probability of incident CAC was modeled as a function of covariates using a generalized linear model with log link and binomial error distribution. Relative risk regression rather than logistic regression was employed because the incidence of new calcification was >10%, so the odds ratio is an overestimate of the relative risk. To estimate the absolute and relative progression of CAC among those with detectable CAC at baseline, we used robust linear regression. These 2 end points were modeled separately. Risk factors considered include age, gender, race, MESA site, follow-up duration, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of coronary artery disease, LDL-C, HDL-C, and cholesterol lowering medications. A p value of ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 9 software.

Results

After excluding 1057 individuals without a follow-up CT scan for CAC score, the final study population consisted of 5755 MESA participants (mean age 62 ± 10 years; 48% males). The follow-up period was 2.4 ± 0.8 years. The characteristics of the study cohort are illustrated in table 1. Subjects were from different ethnic backgrounds, including 2279 (40%) Caucasians, 1558 (27%) African-Americans, 1232 (21%) Hispanics, and 686 (12%) Chinese subjects. Twenty-seven percent of the study population and 49% had detectable TAC and CAC, respectively.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population

| Variable | TAC=0 | TAC 1st Quartile |

TAC 2nd Quartile |

TAC 3rd Quartile |

TAC 4th Quartile |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=4211) | (N=403) | (N=374) | (N=388) | (N= 379) | ||

| Age (years) | 59±9 | 67±9 | 70±8 | 72±7 | 74±7 | <0.0001 |

| Women | 52% | 51% | 55% | 57% | 56% | 0.02 |

| Whites (N=2279) | 37% | 41% | 44% | 48% | 53% | <0.0001 |

| Chinese (N=686) | 12% | 11% | 15% | 15% | 12% | |

| African Americans (N=1558) | 29% | 27% | 23% | 17% | 16% | |

| Hispanics (N=1232) | 22% | 21% | 18% | 20% | 19% | |

| Current smoker | 13% | 11% | 12% | 9% | 12% | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 37% | 58% | 58% | 65% | 73% | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 12% | 15% | 17% | 20% | 20% | <0.0001 |

| Family history of heart attack | 41% | 48% | 46% | 47% | 50% | <0.0001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 117±31 | 122±31 | 116±31 | 118±32 | 116±29 | 0.07 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 51±15 | 50±14 | 51±14 | 52±14 | 51±15 | 0.37 |

| Body mass index kg/m2 | 29±6 | 28±5 | 28±5 | 28±5 | 28±5 | <0.0001 |

| Lipid lowering meds | 13% | 19% | 24% | 28% | 31% | <0.0001 |

TAC Scores According to Quartiles (1st: 1–64; 2nd: 65–267; 3rd: 268–836; 4th:≥837)

Increasing TAC scores were observed with increasing age. Most traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including age, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, and family history were significantly associated with the presence of TAC. LDL-C and HDL-C were not statistically significantly associated with increasing TAC scores.

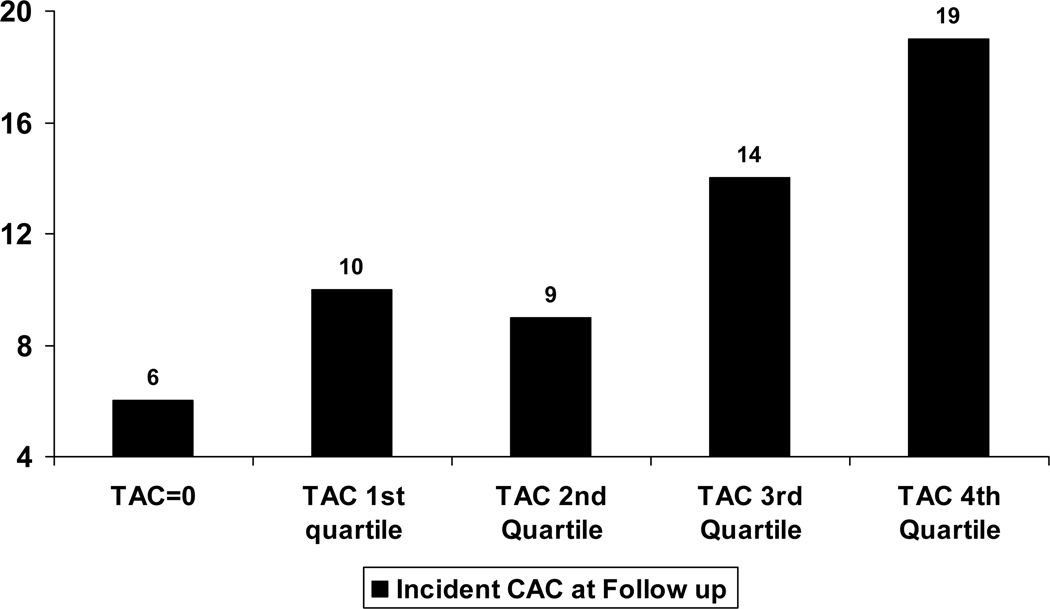

Figure 1 illustrates the incidence of CAC per 100 person years according to TAC among different ethnic groups. Overall, CAC incidence per 100 person years was higher among those subjects who had TAC at baseline versus those that did not (11 per 100 person years versus 6 per 100 person years). A similar association was observed across ethnic groups. The risk of developing new coronary calcium increased with increasing quartiles of TAC (Figure 2).Figure 3 illustrates the median annualized CAC change (CAC progression) according to TAC quartiles. Overall, we observed an increase in median CAC progression with increasing TAC burden.

Figure 1: Incident CAC per 100 person years according to TAC among different ethnic groups.

CAC – Coronary arterial calcification; TAC- Thoracic aortic calcification.

Subjects with no CAC but TAC at baseline were more likely to develop CAC, irrespective of ethnicity.

Figure 2: Incident CAC per 100 person years according to increasing TAC scores.

CAC – Coronary arterial calcification; TAC- Thoracic aortic calcification.

Overall, incidence CAC increased with increasing TAC scores.

Figure 3: Median annualized CAC change according to TAC quartiles among different ethnic groups.

CAC – Coronary arterial calcification; TAC- Thoracic aortic calcification.

In all ethnic groups, CAC progression increases with increasing TAC quartiles.

Incident CAC (new calcium among those with a CAC = 0 at baseline) was associated with the presence of baseline TAC in the overall population (RR 1.72; P < 0.0001) after adjusting for age, sex, race, MESA site, and follow-up period (model 1, table 2). The same association pattern was observed in all ethnic groups, although it was only statistically significant in African-Americans. After traditional cardiovascular risk factors were added to the regression model (model 2, table 2), the association in the overall population was slightly attenuated (RR 1.64; P = 0.002). No statistical interaction between TAC and ethnicity was observed on either regression model. As shown in table 3, for both regression models, incident CAC was associated with increasing TAC scores (P for trend < 0.0001 for both models).

TABLE 2:

Relative Risks for Incident Coronary Arterial Calcium at Follow-up in those with no Coronary Arterial Calcium at Baseline, According to the Presence of Baseline Thoracic Aortic

| Calcium | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk ratios (95% CI) | |||

| Overall | TAC=0 (N=4211) |

TAC>0 (N=1544) |

P value |

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 1.72 (1.28, 2.31) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 1.64 (1.20, 2.23) | 0.002 |

| Whites (N=2279) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 1.54 (0.96–2.45) | 0.07 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 1.36 (0.83–2.25) | 0.22 |

| Chinese (N=686) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 1.41 (0.54–3.71) | 0.48 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 1.43 (0.50–4.05) | 0.50 |

| African Americans (N=1558) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 2.25 (1.32–3.87) | 0.003 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 2.49 (1.40–4.47) | 0.002 |

| Hispanics (N=1232) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 1.65 (0.83–3.25) | 0.15 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 1.50 (0.75–3.01) | 0.25 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, and follow-up duration

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, follow-up duration, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of CAD, LDL-C, HDL-C, and cholesterol lowering medications.

TABLE 3:

Relative Risks for Incident Coronary Arterial Calcium at Follow-up exam Among Those with Baseline Coronary Arterial Calcium = 0, According to Baseline

| Thoracic Arterial Calcium Quartiles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Relative risk ratios (95% CI) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|

TAC=0

(N=4211) |

1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

|

TAC (1st

Quartile) (N=403) |

1.65 (1.068, 2.49) | 1.43 (0.92, 2.23) |

|

TAC (2nd

Quartile) (N=374) |

1.28 (0.77, 2.11) | 1.30 (0.77, 2.18) |

|

TAC (3rd

Quartile) (N=388) |

2.00 (1.09–3.65) | 1.65 (1.068, 2.49) |

|

TAC (4th

Quartile) (N= 379) |

3.80 (1.73–8.35) | 3.92 (1.69, 9.13) |

| P value for trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, and follow-up duration

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, follow-up duration, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of CAD, LDL-C, HDL-C, cholesterol lowering medications

To assess the relationship between absolute CAC change and TAC baseline score, we used multivariable adjusted robust generalized linear regression (table 4). The same covariates applied in the regression analyses of incident CAC (model 1 and 2) were used here. In both models, a baseline TAC score in the third and fourth quartiles was associated with a significant CAC change as compared to the first and second TAC quartiles (table 4). Further adjustment for baseline CAC significantly attenuated the association (4th TAC quartile: CAC change 6.47; 95% CI: 0.79, 12.4).

TABLE 4:

Multivariable Analysis of Absolute Progression of Coronary Calcium According to Baseline Thoracic Arterial Calcium Quartiles

| Robust Difference in Mean Progression (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Absolute CAC Change |

Model 1 | Model 2 |

|

TAC=0

(N=4211) |

0 (ref) | 0 (ref) |

|

TAC (1st Quartile)

(N=403) |

2.89 (−3.16, 8.95) | 0.49 (−5.72, 6.71) |

|

TAC (2nd Quartile)

(N=374) |

7.96 (1.66,14.27) | 4.57 (−1.96, 11.13) |

|

TAC (3rd Quartile)

(N=388) |

13.84 (7.90, 19.78) | 10.06 (3.77, 16.33) |

|

TAC (4th Quartile)

(N= 379) |

24.21 (18.25, 30.18) |

20.50 (14.20, 26.80) |

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, and follow-up duration

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, follow-up duration, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of CAD, LDL-C, HDL-C cholesterol lowering medications

We finally assessed the relation between absolute CAC change and baseline TAC according to ethnicity. We used multivariable adjusted robust linear regression and adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, follow-up period, body-mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of coronary artery disease, LDL-C, HDL-C, and cholesterol-lowering medications. In all ethnic groups, there was a significant difference in absolute CAC change between subjects in the 4th TAC quartile and those in the 1st TAC quartile (Whites: 18.07; 95% CI: 7.62, 28.51 vs. 2.49; 95% CI: −8.57, 13.57; Chinese: 20.81; 95% CI: 6.81, 34.81 vs. 8.97; 95% CI: −5.74, 23.69; African-Americans: 20.12; 95% CI: 5.57, 34.68 vs. −5.42; 95% CI: −17.11, 6.26; Hispanics: 20.62; 95% CI: 7.67, 36.56 vs. 3.44; 95% CI: −9.53, 16.42).

Discussion

This is the first large scale and ethnically diverse study to report on the association of TAC with incident CAC and CAC progression. Previously, Takasu and colleagues (4), using the same cohort (MESA), described the relation between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the presence of TAC. Our study adds to that previous MESA report and expands the present knowledge on the association of extra-coronary atherosclerosis and calcified coronary disease.

Our results demonstrate that the presence of TAC is associated with the development of new CAC, and that the association seems to be stronger with increasing TAC scores, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This overall association could have been driven by the results observed in African Americans, although a statistical test for interaction did not reach statistical significance. The same positive association was observed for CAC change or progression, although it was significantly attenuated after we adjusted for baseline CAC score. We decided to adjust for baseline CAC score since previous reports have suggested that CAC progression is primarily related to the baseline severity of coronary calcium (5, 6).

Kuller and colleagues (7) have previously shown that the presence of aortic calcium and carotid plaque is significantly related to incident CAC in postmenopausal women. The association between aortic calcium and incident CAC in the Kuller et al. study was stronger than that observed between incident CAC and carotid plaque. The presence of a carotid plaque index > 1 and/or an aortic calcium score > 100, as compared to both being negative, was significantly associated with the development of new CAC. Although the study lacks significant external validity, it definitely shows that the detection of extra-coronary atherosclerosis, in this case aortic and carotid plaque, could potentially help identify those individuals more likely to develop new calcified coronary disease.

Taylor and colleagues have reported similar results in a study of middle-age men, mostly Caucasians, who underwent baseline and follow-up electron beam computed tomography scans and baseline assessment of traditional risk factors and carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) measurements (8). The authors found that CAC progression was associated with higher CIMT measurements (0.660 mm vs. 0.603 mm; P=0.001). Each quintile of increasing CIMT was independently associated with a 35% increase in the odds of CAC progression (P = 0.01), after adjusting for Framingham risk score and Creactive protein. In contrast to our study, this study population was restricted to white men and was designed to identify CAC progression and not incident CAC. Nonetheless, it is consistent with Kuller’s and colleagues study and our study in that the presence of extra-coronary atherosclerosis, in particular TAC and carotid disease, may help identify individuals at a higher risk to develop new calcified coronary disease or at a higher risk of disease progression.

Detection and quantification of TAC can be achieved without much risk to the patient and involves low radiation exposure. Identification of individuals with TAC, who are more likely to have coronary artery disease, exhibit coronary atherosclerosis progression, and potentially have a higher event risk, may prove to be an effective risk stratification mechanism. These subjects should be treated aggressively from a cardiovascular prevention standpoint and should be monitored more closely. Future outcomes studies should look at the ability of TAC to increase prediction above and beyond baseline CAC score.

Although the data presented here expands our previous knowledge on the relationship of extra-coronary atherosclerosis and incident CAC and CAC progression, it is important to note that none of those measured parameters are equivalent to hard cardiovascular clinical outcomes. Hence, a limitation of the present study is the lack of outcomes data. In contrast to previous reports, our study offers a higher degree of result external validity, within the study age range, due to the intrinsic MESA design. Another limitation is that TAC was obtained from limited segments of the thoracic aorta. Notably, the extent of calcium in the arch of the aorta and where the aorta goes under diaphragm is typically significantly higher than that in the segments of the aorta that were interrogated for this study. This study used a 4-slice multi-detector computed tomography scanner which may be less sensitive in the detection of TAC as compared to newer scanners. There is also a confounding possibility due to inter-scan variability, which increases with increases in absolute CAC.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Funding support: This research was supported by R01-HL-63963-01A1 and R01-HL-071739-03 and contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Dr. Nasir is supported by Grant No. 1T32 HL076136-02 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 871–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR Jr, Sidney S, Bild DE, Williams OD. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: Standarized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology 2005: 234: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Shea S, Lima JA, Cushman M, Bild DE, Burke GL. Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: results from the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2007; 115: 2722–2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takasu J, Katz R, Nasir K, Carr JJ, Wong N, Detrano R, Budoff MJ. Relationship of thoracic aortic wall calcification to cardiovascular risk factors: the Multu-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am Heart J 2008; 155: 765–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chironi G, Simon A, Denarie N, Denarie N, Vedie B, Sene V, Megnien JL, Levenson J. Determinants of progression of coronary artery calcifications in asymptomatic men at high cardiovascular risk. Angiology 2002; 53: 677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon HC, Emerick AM, Hill JA, Gjertson DW, Goldin JG. Calcium begets calcium: progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects. Radiology 2002; 224: 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuller LH, Matthews KA, Edmundowicz D, Chang Y. Incident coronary artery calcium among postmenopausal women. Atherosclerosis 2008; Feb 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Taylor AJ, Bindeman J, Le TP, Bauer K, Byrd C, Feuerstein IM, Wu H, O’Malley PG. Progression of calcified coronary atherosclerosis: Relationship to coronary risk factors and carotid intima-media thickness. Atherosclerosis 2008; 197: 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]