Abstract

A case of infectious endocarditis with septic embolization as a rare but potentially fatal complication of cardiac catheterization is described, followed by a detailed review of the literature. Obesity, diabetes, many skin punctures, previous bypass surgery and abnormal valves are predisposing factors for bacteremia following cardiac catheterization.

Keywords: Bacteremia, Complications, CVA, Diagnostic angiography, Infection, Sepsis, Stroke

CASE PRESENTATION

A 69-year-old woman with a history of coronary artery disease, coronary artery bypass graft surgery (six months previously), type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia presented to a local emergency department with a prolonged episode of chest pressure, dyspnea and diaphoresis. A review of the rest of her symptoms was unrevealing. Her vital signs were stable. Her temperature was 36.0°C, and the remainder of her examination was normal except for obesity. Cardiac auscultation did not reveal any murmurs. An electrocardiogram demonstrated inverted T waves in leads V2 through V6, and serial troponin T levels were mildly elevated at 0.65 μg/L. Her white blood cell count was normal (5.3×109/L) with a normal differential cell count. The following day, the patient underwent cardiac catheterization by percutaneous puncture of the right femoral artery using a modified Seldinger approach. Left ventriculography and aortography were performed. The aortic valve was noted to be normal. Coronary angiography revealed a severe ostial lesion of the left main coronary artery and total occlusion of the left internal mammary graft to the left anterior descending artery. Hemostasis was achieved by applying direct pressure to the right femoral artery. No closure device was used. The duration of cardiac catheterization was documented to be approximately 36 min. The patient was referred to a specialized cardiac centre for percutaneous coronary intervention of the left main ostial lesion. Before this procedure, on day 6 after cardiac catheterization, she complained of severe headache. The patient had a temperature of 38.5°C and was noted to have neck stiffness. Her white blood cell count was elevated at 19.1×109/L. Coronary intervention was postponed and she was urgently transferred to the University Medical Centre (Arizona, USA) for management of suspected meningitis. The patient showed no evidence of any other infections before or after her cardiac catheterization.

On neurological examination, she was alert and oriented, with intact cranial nerves. Her strength in the left upper extremity was grade 3/5 and grade 4/5 in the right upper extremity in all muscle groups. Her strength in the lower extremities was grade 4/5 bilaterally. Hyperreflexia was demonstrated in both upper and lower extremities. A grade 2/6 systolic murmur was recognized in the aortic area.

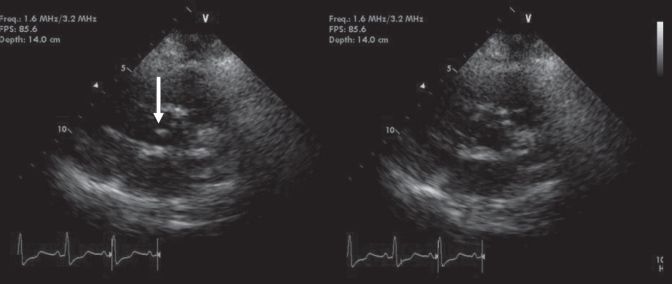

A magnetic resonance imaging scan of the head and neck revealed small subacute embolic infarcts involving the left motor cortex. Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck revealed an epidural fluid collection at the C3 through C6 levels, consistent with epidural abscess (Figure 1). A transthoracic echo-cardiogram demonstrated mobile vegetation on the aortic valve (Figure 2). Subsequently, four blood cultures confirmed the presence of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. The patient was treated with the appropriate antibiotic therapy but developed acute respiratory distress followed by an asystolic cardiac arrest that required intubation, and 1 min of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, on day 8 following her cardiac catheterization.

Figure 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging scan of the neck. White arrows indicate an epidural abscess

Figure 2).

Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram. Parasternal short-axis view showing mobile vegetation on the aortic valve (arrow) that can be seen during systole (left)

Subsequently, the patient was found to be quadriplegic. Her spinal abscess was treated with medical therapy based on the recommendations of the consulting neurosurgeon. The patient’s hospital course was complicated with acute renal failure, requiring dialysis and thrombocytopenia, both of which resolved. She was treated with long-term intravenous antibiotics. She was initially treated with vancomycin and ceftriaxone. However, when her cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant S aureus, she was put on cefazolin treatment for eight weeks. Following a two-month period in the medical intensive care unit, the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility in stable condition on a chronic ventilator and with percutaneous gastrostomy feeding.

DISCUSSION

Infections complicating cardiac catheterization

Bacteremia following cardiac catheterization is rare. In a prospective study (1) that evaluated 960 patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, only 0.4% of patients had positive blood cultures that were significantly associated with cardiac catheterizations and percutaneous coronary interventions. The risk factors for bacteremia following catheterization include obesity, duration of procedure, number of balloons used and the number of skin punctures performed.

Bacteremia occurring secondary to cardiac catheterization rarely leads to systemic or localized infection. Such infections reported as complications of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary angiography include sepsis (2), endocarditis (2–8), suppurative pancarditis (9), stent infection (6,10,11) septic arthritis (12–14), epidural abscess (15), necrotizing fasciitis (16) and groin wound infection (17,18). There are no published reports of native valve endocarditis leading to cerebral embolization, epidural abscess and paraplegia following cardiac catheterization. It is important to mention that we do not have clear evidence that the staphylococcal bacteremia occurred during her cardiac catheterization. It is also possible that the catheterization caused only endocardial damage and had predisposed the patient to infectious endocarditis; subsequently, the bacteremia occurred two days later from other sources such as the nasopharyngeal cavity.

A literature review on endocarditis following cardiac catheterization revealed eight previous cases, which are listed in Table 1. Based on these data, four patients with previous valvular disease had infective endocarditis following cardiac catheterization. Three patients had previously undergone coronary artery bypass graft surgery, similar to our case. Infected stents were found in three patients. The majority of patients developed symptoms and signs of endocarditis between one and seven days after the procedure.

TABLE 1.

Endocarditis following cardiac catheterization

| Author (reference), year | Demograpahic details and risk factors | Procedure | Time to endocarditis* | Bacteria isolated | Valve involved | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index case, 2007 | 69-year-old woman. History: CABG, obesity, diabetes mellitus | Cardiac catheterization | 6 days | Staphylococcus aureus | Aortic | Cerebral infarctions, epidural abscess, quadriplegia, recovery with antibiotics |

| Palmer and Ramsdale (7), 2005 | 61-year-old man status post. History: CABG, mild MR | Cardiac catheterization and stenting x2 | 1 day | Coagulase-negative staphylococcus | Mitral | Hemorrhagic brain infarct due to septic embolus. Recovery with antibiotics |

| Ross et al (4), 2001 | 63-year-old woman. History: Obesity, CABG, on low-dose steroids | Angioplasty and stenting | Following month | Corynebacterium jeikeium | Aortic | Multiorgan failure and death |

| Leroy et al (6), 1996 | 49-year-old man. History: CAD | Palmaz-Schatz stent and control angiography one day later | 7 days | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Mitral | LAD aneurysm, anterior mitral valve chordae rupture. Cardiac arrest and death following CT surgery |

| McCready et al (2), 1991 | 56-year-old woman | Catheterization and PTCA | 1 day | S aureus | Aortic | Aortic valve insufficiency and death |

| 70-year-old woman | Catheterization and PTCA | 1 day | S aureus | Aortic | Septic emboli. Recovery with antibiotics | |

| Perez (3), 1986 | 57-year-old man. History: rheumatic valve disease | Cardiac catheterization | 3 days | Moraxella-like M-6 bacteria | Aortic | Recovery following atrioventricular valve replacement |

| Rubin et al (5), 1978 | 63-year-old man. History: CAD and rheumatic valve disease | Cardiac catheterization | 5 days | Micrococcus mucilaginosus incertae sedis | Mitral | Recovery with antibiotics |

| Winchell (8), 1953 | 44-year-old woman. Rheumatic mitral valve | Cardiac catheterization | 11 days | Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus | Mitral | Recovery with antibiotics |

Duration after procedure for endocarditis to appear. CABG Coronary artery bypass graft; CAD Coronary artery disease; CT Cardiothoracic; LAD Left anterior descending; PTCA Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

A wide variety of bacteria caused endocarditis in these case series. The most common causative organism of bacteremia following cardiac catheterization is S aureus (19), similar to our patient. Furthermore, our patient had diabetes – a risk factor for endocarditis in the general population (20). Obesity is another risk factor for bacteremia during cardiac catheterization, which was also present in our patient (1). Obese patients have been noted to have chronic S aureus colonization of the skin in the groin region (21). This can explain the increased susceptibility of these patients to staphylococcal bacteremia during femoral puncture.

In most reported cases, the aortic valve was predominantly affected, except in patients with previous mitral valve disease. Three of the eight reported cases had a fatal outcome, suggesting that a poor prognosis is associated with infectious endocarditis in the setting of cardiac catheterization.

Based on the guidelines for infectious endocarditis, antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended before performing cardiac catheterization in high-risk patients. Cardiac catheterization is not significantly associated with bacteremia. Despite our case of infectious endocarditis, possibly occurring during the cardiac catheterization procedure, we do not support routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis before cardiac catheterization in high-risk patients. To date, available clinical data do not support prophylactic antibiotic treatment.

A further literature review revealed that iatrogenic causes of infectious endocarditis occur in 28.4% of all endocarditis cases. Patients with iatrogenic causes were older, had poor health and were associated with a higher rate of in-hospital and one-year mortality (59.5% versus 29.6%) (22). Among nondental procedures, only surgery appears to increase the risk in univariate analysis. However, in multivariate analysis, only infectious episodes and skin wounds significantly increased the risk for infectious endocarditis (23).

REFERENCES

- 1.Banai S, Selitser V, Keren A, et al. Prospective study of bacteremia after cardiac catheterization. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1004–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00990-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCready RA, Siderys H, Pittman JN, et al. Septic complications after cardiac catheterization and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:170–4. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.29134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez RE. Endocarditis with Moraxella-like M-6 after cardiac catheterization. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:501–2. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.3.501-502.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross MJ, Sakoulas G, Manning WJ, Cohn WE, Lisbon A. Corynebacterium jeikeium native valve endocarditis following femoral access for coronary angiography. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E120–1. doi: 10.1086/319592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin SJ, Lyons RW, Murcia AJ. Endocarditis associated with cardiac catheterization due to a Gram-positive coccus designated Micrococcus mucilaginosus incertae sedis. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;7:546–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.7.6.546-549.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leroy O, Martin E, Prat A, et al. Fatal infection of coronary stent implantation. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;39:168–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0304(199610)39:2<168::AID-CCD12>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer ND, Ramsdale DR. Mitral valve endocarditis resulting from coagulase-negative Staphylococcus after stent implantation in a saphenous vein graft. Cardiol Rev. 2005;13:152–4. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000128842.48947.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winchell P. Infectious endocarditis as a result of contamination during cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1953;248:245–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195302052480605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grewe PH, Machraoui A, Deneke T, Muller KM. Suppurative pancarditis: A lethal complication of coronary stent implantation. Heart. 1999;81:559. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfonso F, Moreno R, Vergas J. Fatal infection after rapamycin eluting coronary stent implantation. Heart. 2005;91:e51. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.061838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunther HU, Strupp G, Volmar J, von Korn H, Bonzel T, Stegmann T. [Coronary stent implantation: Infection and abscess with fatal outcome.] Z Kardiol. 1993;82:521–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frazee BW, Flaherty JP. Septic endarteritis of the femoral artery following angioplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:620–3. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway AM, Smith MG, Obeid M. Diphtheroid infection of a total knee arthroplasty following femoral percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006;72:366–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurzweil PR, Spencer CW. Infection of a total knee arthroplasty following percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Orthopedics. 1993;16:909–10. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930801-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oriscello RG, Fineman S, Vigario JC, Robertello ME. Epidural abscess as a complication of coronary angioplasty: A rare but dangerous complication. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;33:36–8. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810330110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calderon E, Carter E, Ramsey KM, Vande Waa JA, Green WK, Alpert MA. Necrotizing fasciitis: A complication of percutaneous coronary revascularization. Angiology. 2007;58:360–6. doi: 10.1177/0003319707301752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleveland KO, Gelfand MS. Invasive staphylococcal infections complicating percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: Three cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:93–6. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiener RS, Ong LS. Local infection after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: Relation to early repuncture of ipsilateral femoral artery. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;16:180–1. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samore MH, Wessolossky MA, Lewis SM, Shubrooks SJ, Jr, Karchmer AW. Frequency, risk factors, and outcome for bacteremia after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:873–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Movahed MR, Hashemzadeh M, Jamal MM. Increased prevalence of infectious endocarditis in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2007;21:403–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szilagyi DE, Smith RF, Elliott JP, Vrandecic MP. Infection in arterial reconstruction with synthetic grafts. Ann Surg. 1972;176:321–33. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197209000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-Hidalgo N, Almirante B, Tornos P, et al. Contemporary epidemiology and prognosis of health care-associated infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1287–97. doi: 10.1086/592576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacassin F, Hoen B, Leport C, et al. Procedures associated with infective endocarditis in adults. A case control study. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:1968–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]