Abstract

Background

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) T classification system for cholangiocarcinoma does not take into account the unique pathologic features of the bile duct. As such, the current AJCC T classification for distal cholangiocarcinoma may be inaccurate.

Methods

A total of 147 patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma were identified from a single institution database. The prognostic importance of depth of tumor invasion relative to the AJCC T classification system was assessed.

Results

The AJCC T classification was T1 (n = 11, 7.5%), T2 (n = 6, 4.1%), T3 (n = 73, 49.7%), or T4 (n = 57, 38.8%). When cases were analyzed according to depth of tumor invasion, most lesions were ≥5 mm (<5 mm, 9.5%; range, 5–12, 51.0%; >12 mm, 39.5%). The AJCC T classification was not associated with survival outcome (median survival, T1, 40.1 months; T2, 14.8 months; T3, 16.5 months; T4, 20.2 months; P = .17). In contrast, depth of tumor invasion was associated with a worse outcome as tumor depth increased (median survival, <5 mm, not reached; range, 5–12, 28.9 months; >12 mm, 12.9 months; P = .001). On multivariate analyses, tumor depth remained the factor most associated with outcome (<5 mm; hazard ratio [HR] = referent vs 5–12 mm; HR = 3.8 vs >12 mm; HR = 6.7 mm; P = .001).

Conclusion

The AJCC T classification for distal cholangiocarcinoma does not accurately predict prognosis. Depth of the bile duct carcinoma invasion is a better alternative method to determine prognosis and should be incorporated into the pathologic assessment of resected distal cholangiocarcinoma.

Cholangiocarcinoma is an epithelial cancer originating from bile duct epithelium. The median survival for advanced cholangiocarcinoma is less than 24 months.1 Although cholangiocarcinoma accounts for only 5% of cancer-related deaths in the United States, the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has been increasing over the last 4 decades.2 Surgery remains the only curative option for patients with cholangiocarcinoma, with a 5-year survival rate ranging from 9% to 41% for patients undergoing resection of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.3–6 Recent data from our own group have suggested that survival after curative resection of cholangiocarcinoma may have been increasing over the last 3 decades.7

Despite these trends, the staging system for cholangiocarcinoma remains inadequate. Specifically, the current T classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for cholangiocarcinoma8 has been criticized as being prognostically inaccurate.9–11 Furthermore, terminology used by the AJCC to define T1 and T2 disease, such as “confined to the bile duct histologically” and “beyond the wall of the bile duct” are vague, and provide no precise anatomic landmarks to define the true extent of disease.12 Precise definitions of extent of invasion are particularly important with cancers of the bile duct because the bile duct wall, in contrast to other gastrointestinal tract organs, is not uniformly concentric along its length. Rather, the bile duct wall is composed of varying amounts of fibrous tissue or loose connective tissue. A more precise and reproducible definition of the T classification for cholangiocarcinoma is therefore needed.

Previously, our group has proposed using “depth of invasion” as an alternative method to overcome these problems in the current AJCC staging system T classification.10 Although depth of tumor invasion was shown to predict outcome,9,10 there were a number of concerns raised about using it as a prognostic marker. First, the studies on which some of these concerns were based combined hilar and distal cholangiocarcinomas, which in fact may be inappropriate given the distinct biologic behavior13 and management of these diseases. Perhaps more importantly, there was concern that the use of depth of tumor invasion might be difficult to reproduce among pathologists. Previous data were also exclusively derived from a single East Asian institution, and so it was not known if these results could be reproduced in other institutions.

Therefore, the objective of the current study was to empirically evaluate the prognostic validity of the current AJCC cancer staging system for distal cholangiocarcinoma using data from the United States. We additionally investigated which clinicopathologic determinants were most associated with survival after resection of distal cholangiocarcinoma. Specifically, we sought to analyze the prognostic importance of depth of tumor invasion and, in turn, propose a new T classification system with specific relevance to distal cholangiocarcinoma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between January 1, 1984, and December 31, 2004, a total of 210 patients underwent pancreati-coduodenectomy for distal cholangiocarcinoma with curative intent at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD. Only patients with documented distal cholangiocarcinoma as defined by disease located below the margin of the duodenum were included. Cases of carcinoma arising in the ampulla of Vater or the pancreas, as well as carcinomas with obvious precancerous epithelial changes in the ampulla of Vater or pancreas, were excluded. Of the 210 cases of distal cholangiocarcinoma, 63 were excluded from the study (32 patients had incomplete follow-up and 31 patients had an insufficient number of slide sections available for re-evaluation and measurement of depth of tumor invasion). Based on these various exclusion criteria, 147 patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma remained for analysis. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study.

The following data were collected for each patient: demographics; operative details; resection margin status; tumor size and grade; histologic subtype (eg, papillary carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous); presence of lymph node metastasis; presence of perineural and/or vascular invasion; invasion of adjacent pancreas and/or duodenum; and survival status. In addition, data on the maximal depth of tumor invasion were assessed. Specifically, each case was reviewed by 2 independent pathologists (S.M.H. and R.A.A.). Depth of tumor invasion was measured on slides containing the primary tumor and was defined as the area of deepest infiltration from the mucosal surface (eg, from the basal lamina of the adjacent normal epithelium to the most deeply advanced tumor cells). In cases containing carcinoma in situ (CIS) at the periphery of the invasive tumors, the basal lamina of the CIS was used as the reference. Based on our previous work, maximum depth of tumor invasion was categorized into 3 groups: <5 mm; 5–12 mm; and >12 mm.9,10

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (v.17; SPSS, Chicago, IL) and The R Project for Statistical Computing R (http://www.r-project.org). Summary statistics were obtained using established methods and presented as percentages, mean, and median values. Chi-square statistics were used to compare frequencies of categorical variables among groups. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Variables that were significant on univariate analysis (eg, P < .05) were included in the multivariate models. Survival analyses were performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method (log-rank test). Cox proportional-hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

RESULTS

Table I shows the clinicopathologic features of the 147 patients in the study. The mean patient age was 61 years (range, 44–92), and the majority of patients were male (61.2%). At the time of the operation, the overwhelming majority (90.5%) of patients underwent an R0 resection, which is defined by the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) and AJCC (UICC/AJCC) staging system as a resection in which there is “no macroscopic or microscopic residual tumor.” On pathologic review, the mean size of the primary neoplasm was 2.0 cm (range, 0.3–8.0) with most neoplasms being either moderately differentiated (n = 99; 67.3%) or poorly differentiated (n = 43; 29.3%). The majority of patients (n = 93; 63.3%) had nodal metastasis associated with the primary neoplasm. Perineural or microscopic vascular invasion was identified in 66.7% (n = 98) and 25.9% (n = 38) of patients, respectively.

Table I.

Characteristics of distal cholangiocarcinoma cases (n = 147 patients)

| Factor | Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 90 (61.2) |

| Female | 57 (38.8) | |

| Differentiation | Well | 5 (3.4) |

| Moderately | 99 (67.3) | |

| Poorly | 43 (29.3) | |

| Histologic type | Adenocarcinoma | 143 (97.3) |

| Papillary carcinoma | 3 (2.0) | |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (0.7) | |

| T classification | T1 | 11 (7.5) |

| T2 | 6 (4.1) | |

| T3 | 73 (49.7) | |

| T4 | 57 (38.8) | |

| Nodal metastasis | Absent | 54 (36.7) |

| Present | 93 (63.3) | |

| Resection margin | Absent | 133 (90.5) |

| Present | 14 (9.5) | |

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 49 (33.3) |

| Present | 98 (66.7) | |

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 109 (74.1) |

| Present | 38 (25.9) | |

| Pancreas invasion | Absent | 19 (12.9) |

| Present | 128 (87.1) | |

| Duodenal invasion | Absent | 90 (61.2) |

| Present | 57 (38.8) | |

| Depth of invasion | <5 mm | 14 (9.5) |

| 5–12 mm | 75 (51.0) | |

| >12 mm | 58 (39.5) |

With regard to the extent of local disease, the distal cholangiocarcinoma invaded into the adjacent pancreas or duodenum in 87.1% and 38.8% of cases, respectively. Using the current AJCC T classification, of the 147 distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions, only 11 (7.5%) and 6 (4.1%), respectively, were categorized as T1 and T2. Of the 147 cases, the majority (130 cases) were either T3 (n = 73; 49.7%) or T4 (n = 57; 38.8%). When cases were analyzed according to depth of tumor invasion, most lesions were ≥5 mm (<5 mm, n = 14, 9.5%; 5–12 mm, n = 75, 51.0%; >12 mm, n = 58, 39.5%).

At a median follow-up of 16.8 months (range, 1.1–134.2), 3- and 5-year overall survival rates were 33% and 18%, respectively, with a median survival of 20.3 months. On univariate analysis, a number of clinicopathologic factors were associated with survival. Specifically, significant predictors of poor survival included lymph node metastasis, the presence of perineural or microscopic vascular invasion, invasion into the adjacent pancreas, as well as depth of tumor invasion (Table II). Patients with lymph node metastasis had a median survival of 15.0 months compared with 40.8 months for those without nodal metastasis (P = .003). The presence of perineural and microscopic vascular invasion were also associated with a poor prognosis. Whereas patients with no perineural invasion had a median survival of 31.4 months, those with peri-neural invasion had a median survival of 14.7 months (P < .001). Similarly, the presence of microscopic vascular invasion was associated with a significantly worse long-term outcome. Patients with microscopic vascular invasion had a median survival of 12.1 months compared to 24.5 months for patients without microscopic vascular invasion (P < .0001).

Table II.

Univariate analysis of pathologic features affecting patient survival with distal extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma

| Variable | Characteristics | Median survival (month) | 95% confidence interval

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Sex | Male | 20.2 | 12.2 | 28.2 | .79 |

| Female | 16.6 | 7.8 | 25.4 | ||

| Differentiation | Well | 12.7 | 10.2 | 15.2 | .09 |

| Moderate | 26.0 | 16.2 | 35.8 | ||

| Poor | 11.3 | 7.0 | 15.5 | ||

| T classification | T1 | 40.1 | 30.2 | 51.4 | .17 |

| T2 | 14.8 | 0 | 52.5 | ||

| T3 | 16.5 | 11.3 | 21.7 | ||

| T4 | 20.2 | 9.7 | 30.7 | ||

| Nodal metastasis | Absent | 40.8 | 25.6 | 55.9 | .003 |

| Present | 15.0 | 11.9 | 18.1 | ||

| Resection margin | Negative | 18.9 | 11.1 | 26.7 | .23 |

| Positive | 19.0 | 7.3 | 30.7 | ||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 31.4 | 15.3 | 47.6 | .001 |

| Present | 14.7 | 10.9 | 18.5 | ||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 24.5 | 12.0 | 37.0 | <.0001 |

| Present | 12.1 | 8.0 | 16.2 | ||

| Pancreas invasion | Absent | 40.8 | 32.9 | 48.7 | .02 |

| Present | 18.7 | 12.5 | 24.9 | ||

| Duodenal invasion | Absent | 18.7 | 8.1 | 29.4 | .50 |

| Present | 20.2 | 9.7 | 30.7 | ||

| Depth of invasion | <5 mm | * | – | – | <.0001 |

| 5–12 mm | 28.9 | 18.3 | 39.5 | ||

| >12 mm | 12.9 | 10.5 | 15.5 | ||

Cannot be calculated because 78.6% of patients were alive.

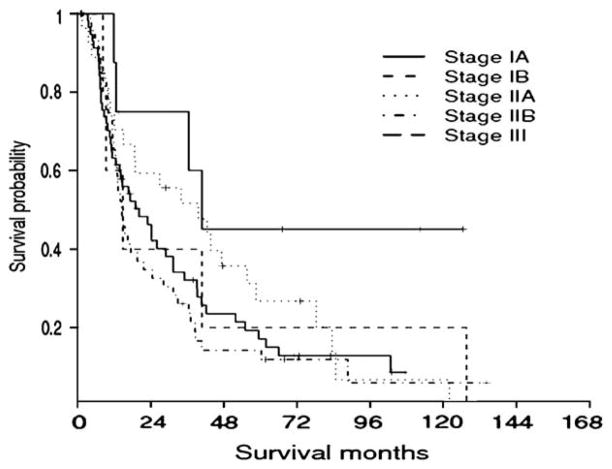

Univariate analysis revealed no significant difference in survival based on age, sex, tumor histology, or histologic grade. Perhaps, most interestingly, statistical analyses also showed that the AJCC T classification was not associated with survival outcome in patients undergoing resection of distal cholangiocarcinoma. The median survival of patients with T1, T2, T3, and T4 lesions were 40.1, 14.8, 16.5, and 20.2 months, respectively (P = .17) (Fig 1). In fact, there was no difference in overall survival in comparisons of T1–T2 lesions (P = .51), T2–T3 lesions (P = .36), or T3–T4 lesions (P = .99).

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis stratified according to the current 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual T classification staging scheme. There was no significant survival difference among the groups (P = .17).

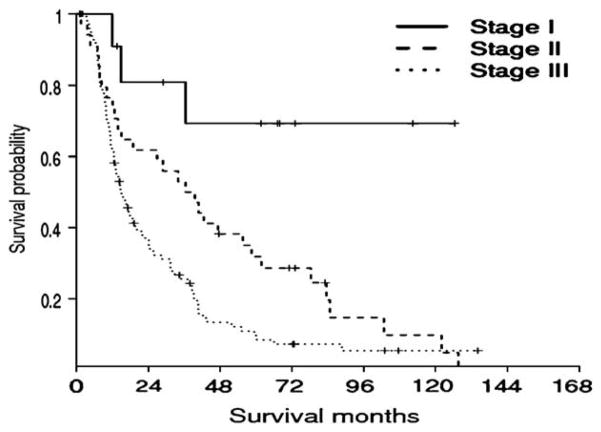

Unlike the AJCC T classification, depth of tumor invasion was a strong predictor of long-term outcome (P < .0001) (Fig 2). Patients with a distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions measuring >12 mm had a median survival of only 12.9 months (95% CI, 10.5–15.5 months) compared with 28.9 months (95% CI, 11.3–39.5 months) for patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions measuring 5 to 12 mm (P = .001). The median survival of patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma measuring <5 mm had not been reached (P = .005). These data corresponded to 5-year survival rates of 69.3%, 21.5%, and 4.1% for patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions measuring <5 mm, 5–12 mm, and >12 mm, respectively (P < .001).

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis stratified according to depth of tumor invasion. Unlike the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) T classification, depth of tumor invasion was a strong predictor of long-term outcome. The 5-year survival rates of patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions measuring <5 mm, 5–12 mm, and >12 mm were 69.3%, 21.5%, and 4.1%, respectively (P < .0001).

Increasing tumor depth was associated with an increased likelihood of having other adverse pathologic tumor characteristics. Specifically, those patients with a depth of tumor invasion >12 mm were significantly more likely to have lymph node metastasis, perineural invasion, and invasion into the adjacent pancreas (Table III). To assess whether depth of tumor invasion would remain a predictor of disease-specific death after adjusting for these factors, multivariate analyses were performed. As noted in Table IV, after adjusting for adverse pathologic factors such as lymph node metastasis, perineural and microscopic vascular invasion, as well as invasion into the adjacent pancreas, depth of tumor invasion remained the most potent predictor of survival.

Table III.

Associations between classification of invasion depth and clinicopathologic variables

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | <5 mm | 5–12 mm | >12 mm | P value |

| Nodal metastasis | 3 (3.2) | 41 (44.1) | 49 (52.7) | <.0001 |

| Perineural invasion | 5 (5.1) | 50 (51.0) | 43 (43.9) | .02 |

| Vascular invasion | 1 (2.6) | 17 (44.7) | 20 (52.6) | .07 |

| Pancreas invasion | 4 (3.1) | 69 (53.9) | 55 (42.7) | <.0001 |

Table IV.

Multivariate analysis for distal neoplasms

| Variable | Relative risk | 95% confidence interval

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Nodal metastasis | 1.15 | 0.73 | 1.80 | .55 |

| Perineural invasion | 1.70 | 1.11 | 2.61 | .015 |

| Vascular invasion | 1.73 | 1.12 | 2.65 | .013 |

| Pancreas invasion | 0.98 | 0.46 | 2.08 | .95 |

| Depth of invasion | .001 | |||

| <5 mm | 1 | — | ||

| 5–12 mm | 3.81 | 1.13 | 12.85 | .031 |

| >12 mm | 6.69 | 1.94 | 23.08 | .003 |

Depth of tumor invasion was associated with an incrementally higher risk of disease-specific death as tumor depth increased (Table IV). Patients with a distal cholangiocarcinoma measuring 5 to 12 mm or >12 mm had more than a 3-fold or 6-fold increased risk of death, respectively, compared with patients who had a lesion measuring <5 mm (<5 mm, referent; 5–12 mm, HR = 3.8; >12 mm, HR = 6.7; both P < .05).

Based on these data, we proposed a revised stage grouping (Table V). Survival of patients based on the current, 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8 T and N stage groupings was compared to the newly proposed staging system. As noted in Figure 3, the AJCC stage grouping had a poor ability to discriminate survival outcome among patients undergoing resection of distal cholangiocarcinoma. Specifically, the median survival of patients with stage IA, IB, IIA, IIB, and III disease was 40.8, 14.8, 39.6, 14.4, and 20.2 months, respectively (P = .15) (Fig 3). In fact, there was no difference in overall survival comparing a stage IA lesion to a stage IB lesion (P = .24), stage IB to IIA lesions (P = .88), stage IIA to IIB lesions (P = .11), or stage IIB to III lesions (P = .47).

Table V.

Proposed new stage grouping for distal cholangiocarcinoma that incorporates depth of tumor invasion

| T classification | N classification | Stage |

|---|---|---|

| T1 (depth of invasion, <5 mm) | N0 | I |

| T2 (depth of invasion, 5–12 mm) | N0 | II |

| T3 (depth of invasion, >12 mm) | N0 | III |

| Any T (T1, T2, or T3) | N1 | III |

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis stratified according to the current 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual stage grouping scheme. There was no significant survival difference among the stage groups (P = .15).

In contrast, the newly proposed stage grouping was a strong predictor of long-term outcome (P < .0001) (Fig 4). Using the newly proposed staging system that incorporated depth of tumor invasion, patients with stage III lesions had a median survival of only 14.7 months (95% CI, 11.1–18.3 months) compared with 36.5 months (95% CI, 19.5–53.5 months) for patients with stage II disease (P = .01). The median survival of patients with stage I distal cholangiocarcinoma had not been reached (proposed stage I vs II, P = .02; proposed stage I vs III, P < .0001). These data corresponded to 5-year survival rates of 69.3%, 28.7%, and 8.5% for patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions with stage I, II, and III disease, respectively (P < .0001).

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis based on our proposed stage grouping that incorporates depth of tumor invasion. Unlike the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage grouping, the proposed new stage grouping was a strong predictor of long-term outcome. The 5-year survival rates of patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma of proposed stages I, II, and III were 69.3%, 28.7%, and 8.5%, respectively (P < .0001).

DISCUSSION

Cholangiocarcinoma has an annual incidence of about 1 in 100,000 in the United States,14 and its incidence is increasing at a rate faster than hepatocellular carcinoma. Resection remains the cornerstone of curative therapy for cholangiocarcinoma. The most optimal utilization of the pathologic specimen for staging, however, remains ill defined. In fact, current AJCC staging for cholangiocarcinoma fails to reflect the distinct biology of the disease. The AJCC staging system combines both proximal and distal extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma into a single T classification scoring scheme.8 The combination of proximal and distal cholangiocarcinoma lesions into a single staging system may be inappropriate.13 Furthermore, the use of vague terms to define the extent of disease may be misleading,12 as noted previously.

The current study is important because it critically assessed the performance of the current AJCC T classification system in a cohort of patients exclusively with distal cholangiocarcinoma. In addition, to our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the prognostic importance of depth of tumor invasion in a Western series of patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma. Our data have important implications, because we found the current AJCC T staging systems to poorly stratify patients after resection of distal cholangiocarcinoma. Rather, depth of the bile duct carcinoma invasion was found to be a much better alternative method to determine prognosis than the current AJCC T classification scheme.

Currently, the AJCC T staging system uses tumor location within the extrahepatic bile duct to help categorize patients into prognostic groups (eg, T2 vs T3). For example, 2 neoplasms with the same depth of invasion in different portions of the bile duct may have different T classifications under the current staging system because of the different surrounding structures, such as the liver or pancreas, according to the portion of the bile duct. However, the fact that a smaller neoplasm invades the pancreas (T3) compared with a larger lesion that has no evidence of pancreas invasion (T2) due to its location may be more a reflection of anatomy than biology. Our data support this theory, as patients with T2 versus T3 lesions had comparable median survival (T2, 14.8 months vs T3, 16.5 months; P = .36). In fact, the failure of the current AJCC T staging system was particularly striking (Fig 3). The AJCC T classification scheme failed to demonstrate statistically significant differences in survival between any of the T subgroups.

In contrast, depth of tumor invasion of the distal cholangiocarcinoma was decidedly a predictor of survival when analyzed either as a continuous or categorical variable (Table III, Fig 4). Whereas the median survival had not been reached for patients with neoplasms measuring <5 mm, the median survival of patients with lesions measuring >12 mm was only 12.9 months. Previous data have also noted the prognostic importance of depth of tumor invasion for cholangiocarcinoma.9,10 Furthermore, other investigators have noted that a lack of tumor invasion, such as extra-hepatic bile duct carcinomas with extensive intra-epithelial ductal spread, carry a much better prognosis.15–18

The current study serves to both independently confirm depth of tumor invasion as an important prognostic factor in a Western cohort of patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma, as well as demonstrate that depth of tumor invasion remains discriminatory in its ability to stratify patients with regard to overall survival even after adjusting for competing risk factors (eg, lymph node metastasis, perineural and microscopic vascular invasion, as well as invasion into the adjacent pancreas) (Table IV). Other important pathologic risk factors associated with survival included lymph node metastasis and the presence of perineural or microscopic vascular invasion. Similar to most other solid gastrointestinal malignancies, the presence of metastatic disease in the regional lymph nodes was associated with a significantly worse outcome in this study. In fact, patients without lymph node metastasis had a median survival that was more than twice as great as patients with nodal metastasis (Table II). Peri-neural invasion and vascular invasion also portended a worse long-term outcome, as others have noted similarly.19–21

Unlike other studies, however, we were able to show that these adverse pathologic factors were significantly more likely to be present in patients with cholangiocarcinoma with a greater depth of tumor invasion (eg, >12 mm) (Table III). These data suggest that a greater depth of tumor invasion portends poor tumor biology and, as expected, a worse overall survival. Interestingly, after controlling for these other poor prognostic factors, depth of tumor invasion remained an independent predictor of outcome. As such, these data imply that, even in the presence of other competing risk factors, depth of tumor invasion may be the single best factor to predict outcome.

The current study had a number of limitations. Depth of tumor invasion was assessed only in a cohort of patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma. Whether depth of tumor invasion is an accurate predictor of outcome in patients with mid-duct or hilar cholangiocarcinoma will need to be examined in future studies. Furthermore, whereas depth of tumor invasion was strongly associated with outcome, measurement of tumor depth is not performed routinely for bile duct neoplasms; pathologists will need to learn how to take these measurements reproducibly. There is, however, precedent in other types of neoplasms (eg, melanoma) for using depth of tumor invasion as a standard prognostic factor. Although there was good concordance between the 2 pathologists (S.M.H. and R.A.A.) in the current study, additional studies are needed to determine the concordance rates of depth of cholangiocarcinoma tumor invasion measurements among pathologists across institutions.

In conclusion, the current AJCC T classification for distal cholangiocarcinoma does not accurately stratify patients with regard to prognosis. Depth of the bile duct carcinoma invasion is a better method for determining prognosis and should be incorporated routinely into the pathologic assessment of resected distal cholangiocarcinoma.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by research grants from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1KL2RR025006-01 to T.M.P.); the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (to T.M.P.); and research grants from the NIH (R01-DK081417 and K08-DK67187 to R.A.A.).

Footnotes

Presented at the 4th Annual Academic Surgical Congress (Joint Meeting of the Association of Academic Surgery and the Society of University Surgeons), Fort Myers, Florida, February 3–6, 2009.

References

- 1.Farley DR, Weaver AL, Nagorney DM. “Natural history” of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:425–9. doi: 10.4065/70.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, et al. Liver resection for hilar and peripheral cholangiocarcinomas: a study of 62 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:70–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755–62. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251366.62632.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugiura Y, Nakamura S, Iida S, et al. Extensive resection of the bile ducts combined with liver resection for cancer of the main hepatic duct junction: a cooperative study of the Keio Bile Duct Cancer Study Group. Surgery. 1994;115:445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bortolasi L, Burgart LJ, Tsiotos GG, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the distal bile duct. A clinicopathologic outcome analysis after curative resection. Dig Surg. 2000;17:36–41. doi: 10.1159/000018798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathan H, Pawlik TM, Wolfgang CL, et al. Trends in survival after surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: a 30-year population-based SEER database analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1488–96. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0282-0. discussion 1496–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong SM, Kim MJ, Pi DY, et al. Analysis of extrahepatic bile duct carcinomas according to the New American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system focused on tumor classification problems in 222 patients. Cancer. 2005;104:802–10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong SM, Cho H, Moskaluk CA, et al. Measurement of the invasion depth of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma: an alternative method overcoming the current T classification problems of the AJCC staging system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:199–206. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213384.25042.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshimi F, Asato Y, Amemiya R, et al. Comparison between pancreatoduodenectomy and hepatopancreatoduodenectomy for bile duct cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:994–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong SM, Presley AE, Stelow EB, et al. Reconsideration of the histologic definitions used in the pathologic staging of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:744–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argani P, Shaukat A, Kaushal M, et al. Differing rates of loss of DPC4 expression and of p53 overexpression among carcinomas of the proximal and distal bile ducts. Cancer. 2001;91:1332–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:115–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakanishi Y, Zen Y, Kawakami H, et al. Extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma with extensive intraepithelial spread: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:807–16. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paik KY, Heo JS, Choi SH, et al. Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile ducts: the clinical features and surgical outcome of 25 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:508–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh KS, Roh HR, Koh YT, et al. Clinicopathologic features of the intraductal growth type of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2000;31:12–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zen Y, Fujii T, Itatsu K, et al. Biliary papillary tumors share pathological features with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Hepatology. 2006;44:1333–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oida Y, Motojuku M, Morikawa G, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumor in small intestine. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:146–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida T, Matsumoto T, Sasaki A, et al. Prognostic factors after pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for distal bile duct cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:69–73. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]