Abstract

Arrested ovarian development is a key characteristic of adult diapause in the mosquito, Culex pipiens. In this study we propose that ribosomal protein S3a (rpS3a), a small ribosomal subunit, contributes to this shut down. RpS3a is consistently expressed in females of C. pipiens that do not enter diapause, but in females programmed for diapause, expression of the rpS3a transcript is dramatically reduced for a brief period in early diapause (7–10 days after adult eclosion). RNA interference directed against rpS3a in nondiapausing females arrested follicle development, mimicking the diapause state. The effect of the dsRNA injection faded within 10 days, allowing the follicles to again grow, thus the suppression of rpS3a caused by RNAi did not permanently block ovarian development, implying that a brief suppression of rpS3a is not the only factor contributing to the diapause response. The arrest in development that we observed in dsRNA-injected females could be reversed with a topical application of juvenile hormone III, an endocrine trigger known to terminate diapause in this species. Though we speculate that many genes contribute to the diapause syndrome in C. pipiens, our results suggest that a shut down in the expression of rpS3a is one of the important components of this developmental response.

Keywords: ribosomal protein S3a, RNAi, diapause, Culex pipiens, ovarian development

Introduction

Adult females of Culex pipiens overwinter in diapause, a dormancy that is characterized by the absence of host-seeking behavior (Bowen et al., 1988; Mitchell, 1983), accumulation of huge fat reserves (Mitchell and Briegel, 1989; Robich and Denlinger, 2005), and an arrest of ovarian development (Christophers, 1911; Spielman and Wong, 1973b). This diapause is induced environmentally by short day length and low temperature (Sanburg and Larsen, 1973; Spielman and Wong, 1973a, b), and at the hormonal level by a shut-down in juvenile hormone (JH) production (Spielman, 1974; Readio et al., 1999). During diapause, the insulin pathway is blocked (Sim and Denlinger, 2008; 2009), a response that we suspect leads to a shutdown of JH synthesis, the accumulation of fat reserves and enhanced stress-resistance.

Ribosome biogenesis is closely linked to the regulation of four ribosomal RNAs (rRNA) and 70–80 ribosomal proteins (rp) (Mager, 1988; Niu and Fallon, 1999). These ribosomal proteins are among the major control points regulating mosquito reproduction, as demonstrated in Aedes aegypti (Raikhel, 1992). Ribosome synthesis supplies the translational machinery to maintain protein production for vitellogenesis in the mosquito fat body (Hagedorn et al, 1973; Raikhel et al, 2002), but ribosomal proteins have numerous secondary functions as well (Niu and Fallon, 2000; Wool, 1993). For example, ribosomal protein S3a (rpS3a) has numerous physiological functions including roles in apoptosis (Naora et al., 1995; 1998), cell transformation (Lecomte et al., 1997; Naora et al., 1996), and initiation of translation (Tolan et al., 1983). RpS3a also plays a role in oogenesis. In Drosophila melanogaster, ovarian development is inhibited when rpS3a is suppressed with an antisense construct (Reynaud et al., 1997), and the gene is up-regulated during oogenesis in Anopheles gambiae (Zurita et al., 1997). Using suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) Robich et al. (2007) showed that rpS3a is among the genes that are down-regulated during early diapause in C. pipiens. In this paper we further evaluate the relationship between rpS3a and diapause. We define a narrow temporal window during which this gene is down-regulated during diapause and use RNA interference (RNAi) to suppress rpS3a in nondiapausing females. This suppression results in a developmental arrest that mimics the ovarian arrest characteristic of diapause. We also show that this arrest can be countered with an application of juvenile hormone, the endocrine signal that normally terminates diapause in this species.

Results

Low expression of rpS3a during early diapause

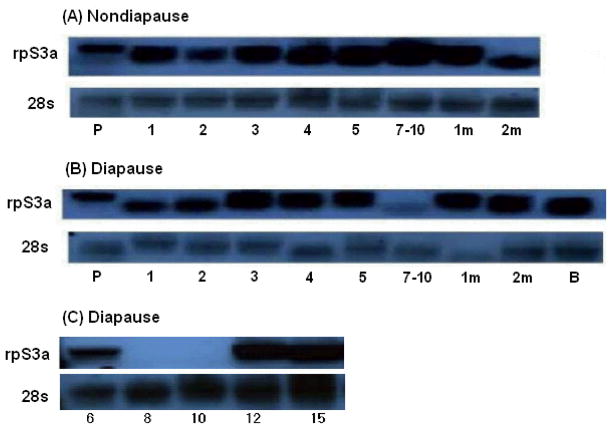

Northern blot hybridization showed that the rpS3a transcript was continuously expressed in pupae and in nondiapausing female adults for at least 2 months after adult eclosion (Figure 1 A), but in diapausing mosquitoes, expression of the transcript was low in females collected 7–10 days after eclosion (Figure 1 B). Additional samples collected 8 and 10 days after adult eclosion confirmed low expression of the transcript in diapausing females during this period (Figure 1 C). These results differ slightly from results reported in a previous paper from our laboratory (Robich et al., 2007). Both studies showed low expression of rpS3a mRNA in early diapause and high expression in late diapause, but the earlier study did not show evidence of rpS3a expression in the nondiapause sample. We attribute this difference to the fact that the earlier study was based on a much smaller fragment (469bp clone) than used in this study (1200bp clone).

Figure 1.

Northern blot hybridization showing expression of the mRNA encoding ribosomal protein S3a (rpS3a). (A) RpS3a was continuously expressed in nondiapausing females reared at 18°C long days. (B) In diapause mosquitoes, reared at 18°C short days, rpS3a was down-regulated in early (7–10 days) stages of diapause. (C) Further confirmation of the low expression of rpS3a on day 8 and 10 diapausing females. 28S ribosomal RNA was used as a control.

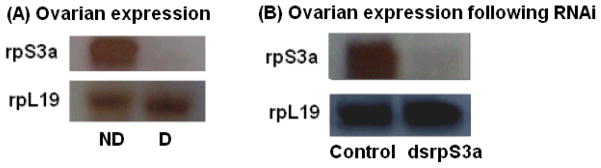

In addition to the whole body results presented in Figure 1, we examined expression in the ovaries and confirmed that the down-regulation of rpS3a was also evident in the ovaries of diapausing females (Figure 2 A).

Figure 2.

Northern blot hybridization confirming expression of rpS3a in the ovaries. (A) RpS3a expression was high in ovaries of nondiapausing mosquitoes (ND) 10 days after eclosion, but down-regulated in diapausing females of the same age. RpL19 was used to confirm equal loading. (B) RpS3a expression indicates suppressed expression in the ovaries of nondiapausing females injected with dsrpS3a on day 4 and examined on day 6.

Arrested ovarian development following dsRNA of rpS3a in nondiapausing females

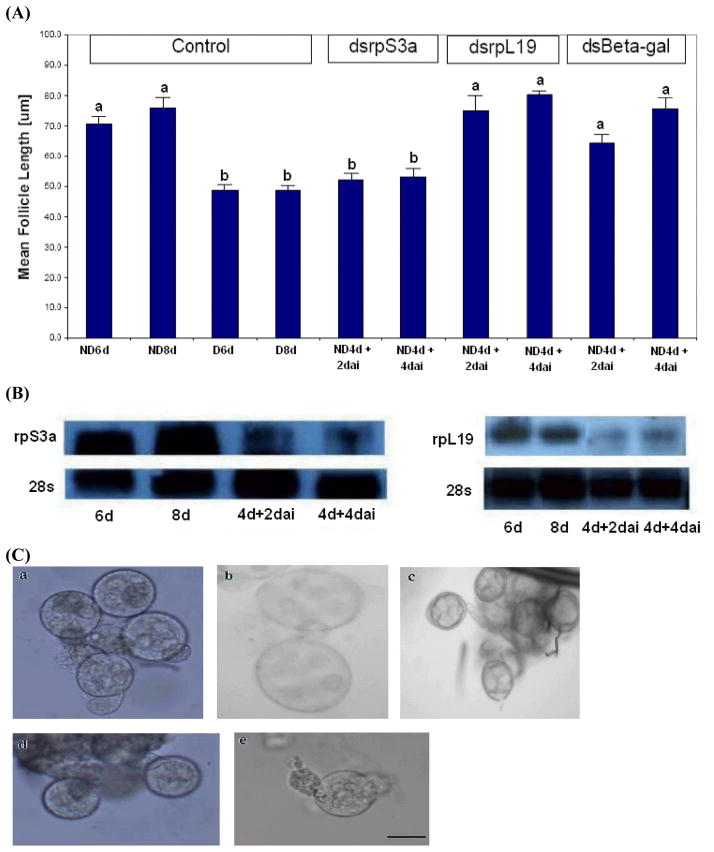

RNAi was used to directly evaluate the function of rpS3a. An injection of dsrpS3a into nondiapausing mosquitoes suppressed ovarian development and mimicked the arrest observed in diapause. Follicles observed 2 days after dsrpS3a injection into 4 day-old nondiapause mosquitoes were significantly smaller than those of 6 day-old nondiapause mosquitoes (Figure 3 A, P = 0.001, One-way ANOVA). Follicles were still in a stage of arrest 4 days after the dsRNA injection; the arrested follicles of the dsRNA-injected nondiapausing mosquitoes were similar in size and shape to follicles dissected from diapausing mosquitoes (Figure 3A and C). The arrest we noted using dsrpS3a was not seen in either the dsrpL19 (another ribosomal protein) or dsβ-gal controls (Figure 3A). Northern blot hybridization confirmed a reduction in the level of transcript following RNAi for rpS3a and rpL19 (Figure 3 B). Pair-wise comparison showed significant differences between the nondiapause control group and the dsrpS3a-injected group, and between the dsrpS3a-injected group and the dsrpL19-injected group (P < 0.01) at the 5% significance level. These results suggest that rpS3a is critical for the progression of ovarian development in C. pipiens.

Figure 3.

The effect of injection of dsRNA on expression of rpS3a. (A) Mean ± SD length of primary follicles after injection of dsrpS3a (10 follicles measured per mosquito; total of 10 mosquitoes for controls and 25 mosquitoes for others. ND = nondiapause mosquitoes, D = diapause mosquitoes, d = days after adult eclosion, dai = days after injection). Ovarian development was arrested when rpS3a was suppressed by dsRNA injection. dsRNAs of rpL19 and β-gal were injected as internal controls. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different (P > 0.05). (B) Northern blot hybridization confirmed suppression of rpS3a (left) and suppression of rpL19 (right) in nondiapause mosquitoes. 28S ribosomal RNA was used as a control. (C) Primary follicle images: a. Nondiapause mosquito, 6 days, b. Nondiapause mosquito, 8 days, c. Diapause mosquito, 8 days, d. Nondiapause mosquito, 4 days + 2 days after injection of dsrpS3a, e. Nondiapause mosquito, 4 days + 4 days after injection of dsrpS3a. (Scale bar = 50 μm)

To confirm that RNAi directed against rpS3a suppressed expression not only in the whole body but also within the ovary, we used Northern blot hybridization to evaluate expression within the ovary. As shown in Figure 2 B, an injection of dsrpS3a into nondiapausing females did indeed suppress expression of rpS3a within the ovary.

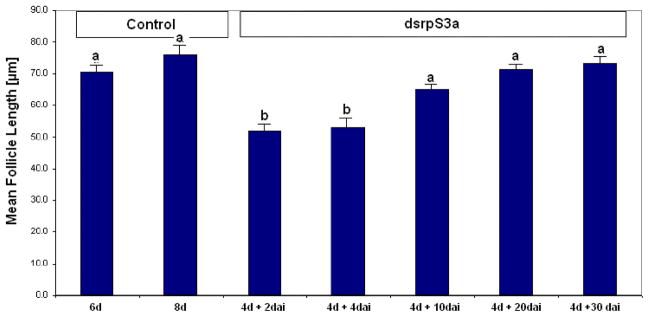

RNAi effect degrades with time

Duration of the RNAi effect was tracked by measuring primary follicle length at different intervals after dsRNA injection (Figure 4). Although the follicles were clearly arrested 2 and 4 days after dsRNA injection, development was again evident 10 days after injection. Follicle length gradually increased with time (Figure 4). When measured 20 and 30 days after injection, follicle lengths of dsRNA injected females were nearly identical to that of non-injected nondiapausing controls.

Figure 4.

The effect of dsrpS3a in nondiapausing mosquitoes at different times after injection. Mean ± SD primary follicle length slightly increased with time after dsrpS3a injection due to the presumed degradation of dsRNA (10 follicles measured per mosquito; total 10 mosquitoes for controls and 25 mosquitoes for others). d = days after adult eclosion, dai = days after injection of dsrpS3a. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

JHIII rescues the arrested ovarian development

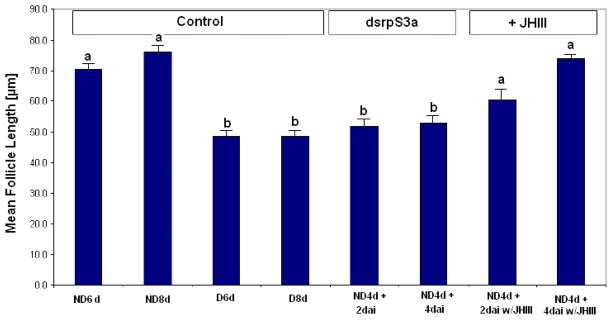

JHIII was used in an attempt to rescue the arrest in ovarian development caused by dsRNA of rpS3a. Primary follicles were significantly larger when dsRNA-injected females received an application of JHIII: this effect was already evident 2 days after JHIII treatment and was quite pronounced by 4 days (Figure 5). Pair-wise comparisons showed that the only significant differences at the 5% level were between the nondiapause and diapause controls and between the nondiapause controls and those injected with dsrpS3a. These results clearly show that JHIII can rescue the rpS3a suppressed mosquitoes, thus suggesting a causative link between suppression of rpS3a, ovarian developmental arrest and the JH deficiency known to regulate adult diapause in this mosquito.

Figure 5.

Juvenile hormone (JHIII) rescues the ovarian developmental arrest caused by an injection of dsrpS3a. Mean ± SD primary follicles initiated development when JHIII was applied immediately after a dsrpS3a injection (10 follicles measured per mosquito; total 10 mosquitoes for controls and 25 mosquitoes for others). ND = nondiapause mosquitoes, D = diapause mosquitoes, d = days after adult eclosion, dai = days after injection of dsrpS3a. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The evidence we present in this study is consistent with the idea that rpS3a may be a link in the diapause mechanism. Although rpS3a is highly expressed in both nondiapausing and diapausing females at the very beginning of adult life and also at an age of one month, the gene is down-regulated for a brief period, 7–10 days after adult eclosion, in diapausing females. This down-regulation is evident not only in whole bodies but also within the ovaries. We used RNAi directed against rpS3a to see if we could mimic a “diapause-like” ovarian arrest in nondiapausing females, and indeed dsrpS3a successfully arrested development in these females. Diapause, of course, represents more than a single gene response, and the arrest we observed was not a long-term arrest that is fully equivalent to diapause. Also the fact that the RNAi-induced suppression in nondiapausing females was not as pronounced as the naturally-occurring down-regulation of rpS3a during diapause likely contributes to the abbreviated arrest we observed. We suspect that the precise timing of rpS3a suppression is also critically important. But, taken together our current results suggest that the down-regulation of rpS3a noted in diapause-destined mosquito females is likely to be an important component of the diapause syndrome.

The duration of dsRNAin a test organism is critical for the success of an RNAi experiment (Montgomery et al., 1998). The gene knockdown effects of dsRNA are frequently maintained for 3–10 days, depending on the gene and organism (Byrom et al., 2002; Dorn et al., 2004; Hemmings-Mieszczak et al., 2003). In our experiments, the RNAi effect remained for at least 4 days but was lost after 10 days.

In diapausing females of C. pipiens, the arrest in ovarian development is prompted by a shut-down in the production of JH (Readio et al., 1999), and the arrest can be terminated by application of exogenous JH (Spielman, 1974). We have shown that JHIII, the juvenile hormone found in mosquitoes (Zhu et al., 2003), is also capable of terminating the arrest in ovarian development caused by suppression of rpS3a. Together, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that the arrest in ovarian development that characterizes diapause of C. pipiens is linked to reduced expression of rpS3a. It is not yet clear how JH rescues the arrested development. One might assume that the naturally high JH titer present in nondiapausing females would be sufficient to counter the dsRNA-induced arrest, but this apparently is not the case. Possibly suppression of rpS3a is somehow directly or indirectly blocking JH production or action, but these scenarios remain to be tested.

Although ribosomal proteins are best known for their primary role in protein synthesis (Wool et al., 1995; Wool, 1996), it is clear that many ribosomal proteins also serve secondary functions that differ substantially from their role in regulating protein synthesis (Coetzee et al., 1994; Hart et al., 1993; Kim et al., 2004; Watson et al., 1992; Wu et al., 2008). Specifically, down-regulation of rpS3a has been linked in several cases to an arrest in growth, e.g. in erythrocytes (Cui et al., 2000) and NIH 3T3 cells (Naora et al., 1998). In insects, one of the reported functions of rpS3a is a role in oogenesis. The rpS3a gene in D. melanogaster is highly expressed in follicular epithelial cells of the ovary (Reynaud et al., 1997), and using transgenic flies, they confirmed that suppression of the rpS3a gene causes an abnormality of oogenesis: egg production was significantly decreased in an antisense transgenic line. In the mosquito, A. gambiae, this gene is up-regulated in the ovary during oogenesis (Zurita et al., 1997). Our data on C. pipiens also supports a role for rpS3a in oogenesis, and we suggest that suppression of this gene is a feature of reproductive diapause in this species. Whether the role of rpS3a in diapause is strictly related to protein synthesis or may involve a secondary role is unresolved, but it is clear that there is some specificity to this response, as demonstrated by the fact that suppression of rpS3a elicits the diapause-like arrest, while suppression of another ribosomal protein, rpL19, does not.

Experimental Procedures

Insect rearing

The colony of C. pipiens (Buckeye strain) was maintained at 25°C, 75%R.H., with a 15L (light):9D (dark) cycle (Nondiapause, 25°C). Ground fish food (TetraMin, Tetra, Blacksburg, VA, USA) was provided as the larval food. As second instar larvae, experimental groups were transferred to either 18°C, 75% R.H., 9L:15D to program diapause (Diapause, 18°C) or to 18°C, 75% R.H., 15L:9D as a nondiapause control group (Nondiapause, 18°C). Adult mosquitoes were provided water and a 10% sucrose solution. The sucrose solution was removed from the cage of diapause-programmed mosquitoes 10 days after adult eclosion to mimic the low availability of a sugar source during the overwintering period.

Cloning rpS3a and Northern blot hybridization

The gene encoding rpS3a was cloned using a TOPO TA Cloning® kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with forward and reverse primers (5′-CAC GCC TTC TCA ATG TCC TT -3′ and 5′-AAG GTT GTG GAT CCG TTC AC -3′) designed from the retrieved sequences reported by Robich et al. (2007) and the A. aegypti rpS3a sequence from the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using BLAST programs. Sequence of ribosomal protein L19 (rpL19), used as a control, was archived in VectorBase (www.vectorbase.org, CPIJ014540-RA) and cloned as described above with primers (forward primer: 5′-ATG AGT TCC CTC AAG CTC CA -3′, reverse primer: 5′-ATC AGG ATG CGC TTG TTC TT -3′).

Total RNA was extracted from female mosquitoes using TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured to quantify RNA by a spectrophotometer at 260nm (BioSpecmini, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). For ovarian RNAs, 50 ovaries from 25 females were collected in each condition. Formaldehyde denaturing RNA gels were transferred onto a Hybond-nylon positive membrane (GE Healthcare Bio-Science, Uppsala, Sweden) using a Schleicher and Schuell TurboBlotter system (Schleicher and Schuell BioScience Inc, Keene, NH, USA). The rpS3a and rpL19 probes were labeled using the Dig High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA). 28S ribosomal RNA from C. pipiens was used to verify equal loading. All Northern blot hybridization results were replicated three times.

dsRNA of rpS3a

dsRNA of rpS3a using T7 (5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG - 3′) -forward primer (5′-CGT TGT TGG TGA TGA TCT GG - 3′) and T7-reverse primer (5′-AAG GTT GTG GAT CCG TTC AC - 3′), dsRNA of rpL19 using T7-primers (forward primer: 5′-ATG AGT TCC CTC AAG CTC CA -3′, reverse primer: 5′-ATC AGG ATG CGC TTG TTC TT -3′), and dsRNA of β-galactosidase used as the second control (primers described in Sim and Denlinger, 2009) were prepared by the MEGAscript T7 transcription kit (Ambion, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as previously described (Sim et al., 2007). 0.4ug/ul dsrpS3a or 0.5ug/ul dsrpL19 or 0.5ug/ul ds β-gal was injected into the thorax of cold, carbon dioxide -anesthetized nondiapausing female mosquitoes (reared at 18°C) 4 days after eclosion using a microinjector (Tritech Research, Los Angeles, CA, USA). All injected nondiapausing mosquitoes were placed at 18°C, 75% R.H., 15L:9D with cotton wicks soaked in a 10% sucrose solution. Ovaries of dsRNA injected mosquitoes (rpS3a, rpL19 and β-gal) were dissected 2, 4, 10, 20, and 30 days after injection, and the length of the primary follicles were measured using an Inverted Tissue Culture Microscope (Nikon Diaphot, Melville, New York, USA). To confirm RNAi efficiency, Northern blot hybridization was performed using RNAs extracted from dsrpS3a and dsrpL19 injected mosquitoes. Follicles were separated from ovaries using #00 insect pins (0.3mm diameter) under a microscope, and images of each follicle were made using a Zeiss Axioskop Widefield Light Microscope at the Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility at the Ohio State University.

JHIII application

Juvenile hormone (JH) III (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used in experiments designed to rescue the developmental arrest caused by an injection of dsrpS3a. 0.1ug/ul JHIII diluted in acetone was topically applied to females immediately after injection of dsrpS3a. Lengths of primary follicles were measured 2 and 4 days after injection/application as described above.

Statistics

One-way ANOVA using MINITAB (Minitab Inc., version 14, State College PA, USA) was used to analyze the statistical significance of differences in length of the primary follicles. A pair-wise comparison was used for multiple treatment comparisons, and a 5% significance level was applied to all tests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant R01-AI058279.

References

- Bowen MF, Davis EE, Haggar DA. A behavioral and sensory analysis of host-seeking behavior in the diapausing mosquito Culex pipiens. J Insect Physiol. 1988;34:805–813. [Google Scholar]

- Byrom M, Pallotta V, Brown D, Ford L. Visualizing siRNA in Mammalian cells: Fluorescence analysis of the RNAi effect. Ambio TechNotes. 2002;9:68. [Google Scholar]

- Christophers SR. The development of the egg follicle in Anophelines. Paludism. 1911;1:73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee T, Herschlag D, Belfort M. Escherichia coli proteins, including ribosomal protein S12, facilitate in vitro splicing of phage T4 introns by acting as RNA chaperones. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1575–1588. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui K, Coutts M, Stahl J, Sytkowski AJ. Novel interaction between the transcription factor CHOP (GADD153) and the ribosomal protein FTE/S3a modulates erythropoiesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;275:7591–7596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn G, Patel S, Wotherspoon G, Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Barclay J, Natt FJC, Martin P, Bevan S, Fox A, Ganju P, Wishart W, Hall J. siRNA relieves chronic neuropathic pain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn HH, Fallon AM, Laufer H. Vitellogenin synthesis by the fat body of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Evidence for transcriptional control. Dev Biol. 1973;31:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart K, Klein T, Wilcox M. A Minute encoding a ribosomal protein enhances wing morphogenesis mutants. Mech Dev. 1993;43:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90028-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Dorn G, Natt FJ, Hall J, Wishart WL. Independent combinatorial effect of antisense oligonucleotides and RNAi-mediated specific inhibition of the recombinant Rat P2X3 receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2117–2126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KY, Park SW, Chung YS, Chung CH, Kim JI, Lee JH. Molecular cloning of low-temperature-inducible ribosomal proteins from soybean. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:1153–1155. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte F, Szpirer J, Szpirer C. The S3a ribosomal protein gene is identical to the Fte-1 (v-fos transformation effector) gene and the TNF-α-indeuced TU-11 gene, and its transcript is altered in transformed and tumor cells. Gene. 1997;186:271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00719-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager WH. Control of ribosomal protein gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;949:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CJ. Differentiation of host-seeking behavior from blood-feeding behavior in overwintering Culex pipiens (Diptera; Culicidae) and observations on gonotrophic dissociation. J Med Entomol. 1983;20:157–163. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/20.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CJ, Briegel H. Inability of diapausing Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) to use blood for producing lipid reserves for overwinter survival. J Med Entomol. 1989;26:318–326. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/26.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MK, Xu S, Fire A. RNA as a target of double stranded RNA-mediated genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15502–15507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naora H, Nishida T, Shindo Y, Adachi M, Naora H. Association of nbl gene expression and glucocorticoid-indeuced apoptosis in mouse thymus in vivo. Immunology. 1995;85:63–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naora H, Nishida T, Shindo Y, Adachi M, Naora H. Constitutively enhanced nbl expression is associated with the induction of internucleosomal DNA cleavage by actinomycin D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:258–264. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naora H, Takai I, Adachi M, Naora H. Altered cellular responses by varying expression of a ribosomal protein gene: Sequential coordination of enhancement and suppression of ribosomal protein S3a gene expression induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:741–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu LL, Fallon AM. The ribosomal protein L34 gene from the mosquito, Aedes albopictus: exon intron organization, copy number, and potential regulatory elements. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29:1105–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu LL, Fallon AM. Differential regulation of ribosomal protein gene expression in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes before and after the blood meal. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:613–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan DR, Hershey JWB, Traut RT. Crosslinking of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF3 to the 40S ribosomal subunit from rabbit reticulocytes. Biochemie. 1983;65:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(83)80062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikhel AS. Vitellogenesis in mosquitoes. Adv Dis Vector Res. 1992;9:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Raikhel AS, Kokoza VA, Zhu J, Martin D, Wang SF, Li C, Sun G, Ahmed A, Dittmer N, Attardo G. Molecular biology of mosquito vitellogenesis: from basic studies to genetic engineering of anti-pathogen immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1275–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Readio J, Chen MH, Meola R. Juvenile hormone biosynthesis in diapausing and nondiapausing Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1999;36:355–360. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/36.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud E, Bolshakov VN, Barajas V, Kafatos FC, Zurita M. Antisense suppression of the putative ribosomal protein S3A gene disrupts ovarian development in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:462–467. doi: 10.1007/s004380050590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robich RM, Denlinger DL. Diapause in the mosquito Culex pipiens evokes a metabolic switch from blood feeding to sugar gluttony. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15912–15917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507958102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robich RM, Rinehart JP, Kitchen LJ, Denlinger DL. Diapause-specific gene expression in the northern house mosquito, Culex pipiens L., identified by suppressive subtractive hybridization. J Insect Physiol. 2007;53:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanburg LL, Larsen JR. Effect of photoperiod and temperature on ovarian development in Culex pipiens pipiens. J Insect Physiol. 1973;19:1173–1190. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(73)90202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim C, Hong YS, Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, Higgs S, Collins FH. Anopheles gambiae heat shock protein cognate 70B impedes o’nyong-nyong virus replication. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim C, Denlinger DL. Insulin signaling and FOXO regulate the overwintering diapause of the mosquito Culex pipiens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6777–6781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802067105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim C, Denlinger DL. A shut-down in expression of an insulin-like peptide, ILP-1, halts ovarian maturation during the overwintering diapause of the mosquito Culex pipiens. Insect Mol Biol. 2009;18:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman A. Effect of synthetic juvenile hormone on ovarian diapause of Culex pipiens mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 1974;11:223–225. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/11.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman A, Wong J. Studies on autogeny in natural populations of Culex pipiens. III. Midsummer preparation for hibernation in anautogenous populations. J Med Entomol. 1973a;10:319–324. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/10.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman A, Wong J. Environmental control of ovarian diapause in Culex pipiens. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1973b;66:905–907. [Google Scholar]

- Watson KL, Konrad KD, Woods DF, Bryant PJ. Drosophila homolog of the human S6 ribosomal protein is required for tumor suppression in the hematopoietic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11302–11306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wool IG. The Translational Apparatus. Plenum Press; New York: 1993. The bifunctional nature of ribosomal proteins and speculations on their origins. [Google Scholar]

- Wool IG. Extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:164–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, De Croos JNA, Storey KB. Cold acclimation-induced up-regulation of the ribosomal protein L7 gene in the freeze tolerant wood frog, Rana sylvatica. Gene. 2008;424:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JS, Chen L, Raikhel AS. Posttrapscriptional control of the competence factor beta FTZ-F1 by juvenile hormone in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13338–13343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234416100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita M, Reynaud E, Kafatos FC. Cloning and characterization of cDNAs preferentially expressed in the ovary of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 1997;6:55–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1997.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]