Abstract

Recent studies suggest that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are functional messenger molecules in central sensitization, an underlying mechanism of persistent pain. Because spinal cord long-term potentiation (LTP) is the electrophysiological basis of central sensitization, this study investigates the effects of the increased or decreased spinal ROS levels on spinal cord LTP. Spinal cord LTP is induced by either brief, high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of a dorsal root at C-fiber intensity or superfusion of a ROS donor, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH), onto rat spinal cord slice preparations. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) evoked by dorsal root stimulations with either Aβ- or C-fiber intensity are recorded from the superficial dorsal horn. HFS significantly increases the slope of both Aβ- and C-fiber evoked fEPSPs, thus suggesting LTP development. The induction, not the maintenance, of HFS-induced LTP is blocked by a N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5). Both the induction and maintenance of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs are inhibited by a ROS scavenger, either N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone or 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl. A ROS donor, t-BOOH-induced LTP is inhibited by N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone but not by d-AP5. Furthermore, HFS-induced LTP and t-BOOH-induced LTP occlude each other. The data suggest that elevated ROS is a downstream event of NMDA receptor activation and an essential step for potentiation of synaptic excitability in the spinal dorsal horn.

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are byproducts of normal cellular metabolism. An excessive level of ROS, however, is involved in many degenerative diseases in the CNS (Contestabile 2001; Jenner 1994) due to a prominent role of ROS in cell damage and death, including that of neurons. Recent evidence suggests that ROS also play a critical role in persistent neuropathic (Kim et al. 2004) and inflammatory (Salvemini et al. 2006) pain. Several lines of indirect evidence suggest that ROS serve as functional messenger molecules in central sensitization, an underlying mechanism for persistent pain (Gao et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2007; Schwartz et al. 2008). To investigate ROS involvement in central sensitization in detail, we examined the effects of ROS donors and ROS scavengers on spinal cord long-term potentiation (spinal cord LTP), which is considered to be the electrophysiological basis of central sensitization.

As a model of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, LTP has been studied extensively in the hippocampus and is thought to be a cellular basis for learning and memory (Bliss and Collingridge 1993). LTP-like phenomena also have been observed in the spinal cord in both in vitro and in vivo experiments and have been termed spinal cord LTP (Ikeda et al. 2003; Liu and Sandkuhler 1995; Randic et al. 1993). Spinal cord LTP is in many ways similar to the better-studied hippocampal LTP because both types show an increased responsiveness of the affected neurons with a prolonged time course and also show a dependency on N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors for the triggering process (Liu and Sandkuhler 1995, 1998; Randic et al. 1993; Svendsen et al. 1998). Spinal cord LTP is thought to be a major mechanism of central sensitization, a nociceptor-dependent increase in neuronal excitability in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Cook et al. 1987; Ji et al. 2003; Woolf 1983), which is characterized by a reduction in the activation threshold, an increase in the responsiveness of dorsal horn neurons, and an enlargement of their receptive fields (Cook et al. 1987). Maintained central sensitization is an important mechanism underlying persistent neuropathic and inflammatory pain (Ji et al. 2003; Sandkuhler 2000), and spinal cord LTP is the physiological representation of central sensitization (Ji et al. 2003; Sandkuhler 2000; Willis 2002). Thus investigating the involvement of ROS in spinal cord LTP may provide insights into the role of ROS in central sensitization and persistent pain.

To determine the role of ROS in central sensitization, the present study examines the effects of ROS scavengers and donors on the development and maintenance of spinal cord LTP by recording field excitatory synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) from the spinal cord dorsal horn using an in vitro spinal cord slice preparation. The results show that ROS are essential not only for the induction but also for the maintenance of spinal cord LTP as manifested by increased Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs, which might be the underlying mechanism of Aβ-fiber-mediated pain (touch-evoked pain, allodynia).

METHODS

Experimental animal preparation

Young male Sprague-Dawley rats (18–22 days old) were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley in Houston, TX. Protocols for animal care and use are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch and comply with the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane in oxygen (3% for induction and 1.5% for maintenance), and a laminectomy was performed. The spinal cord was excised from the mid-thoracic to low lumbar levels and was quickly placed in cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) [containing (in mM): 117 NaCl, 3.6 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, bubbled with a mixed gas of 95% O2-5% CO2]. After being trimmed and embedded in an agar block, the L4–L6 spinal cord segments were then sliced transversely at a thickness of 450–500 μm, with the corresponding dorsal roots attached using a vibratome (Leica, VT1000S). Spinal cord slices with the attached dorsal roots were incubated in ACSF at 30°C for 1 h.

Determination of stimulation paradigms

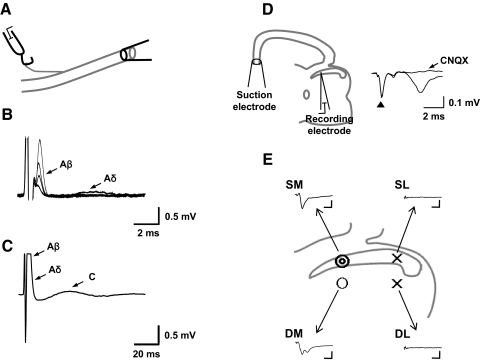

To determine the type of afferent fibers activated by electrical stimulation, compound action potentials were recorded from the dorsal root (n = 5) while stimulating the peripheral nerve in an in vitro peripheral nerve preparation (Fig. 1A). The isolated in vitro peripheral nerve was prepared by dissecting out the dorsal root and dorsal root ganglion along with the attached either L4 or L5 spinal nerve. After placing the peripheral nerve preparation in a recording chamber, the cut proximal end of the spinal nerve was placed in a suction electrode for electrical stimulation. Extracellular compound action potentials were recorded from the dorsal root using a silver wire hook electrode while stimulating the spinal nerve with various stimulus parameters.

Fig. 1.

A: compound action potentials were recorded with a hook electrode from the isolated dorsal rootlet while stimulating the cut proximal end of the dorsal root by a suction electrode. B and C: examples of extracellular compound action potential recordings evoked at 2 different stimulus intensities (B, 30–60 μA; C, 1 mA). The threshold intensities for Aβ-, Aδ- and C-fiber activation were 40, 60, and 700 μA, respectively. The stimulus duration was 0.5 ms. Calculated conduction velocities were 17.6, 6.1, and 1.5 m/s for Aβ-, Aδ- and C-fibers, respectively. D: field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) recording setup and examples of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. fEPSPs were recorded from the superficial medial dorsal horn while stimuli were applied to the cut proximal end of the attached dorsal root with a suction electrode. The fEPSPs evoked by Aβ-strength stimulus was completely blocked by bath application of 20 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxalene-2,3-dione (CNQX), suggesting that fEPSP is mediated by glutamate AMPA/kinate receptors. ▲, stimulus artifact. E: an outline of the dorsal quadrant of a transverse spinal cord slice with recorded fEPSPs at 4 locations: superficial medial (SM), superficial lateral (SL), deep medial (DM), and deep lateral (DL) dorsal horn. The probabilities of recording fEPSPs with a clear 1st peak were signified by symbols ( , 6–8 of 10 samples; ○, 1–3 of 10 samples; ×, 0 of 10 samples). Typical examples of raw traces of fEPSP from each location (SM, SL, DM, and DL) are shown. Calibration bars are 3 ms and 0.1 mV. Note that most of fEPSPs (6 of 10) from DM have multiple peaks.

, 6–8 of 10 samples; ○, 1–3 of 10 samples; ×, 0 of 10 samples). Typical examples of raw traces of fEPSP from each location (SM, SL, DM, and DL) are shown. Calibration bars are 3 ms and 0.1 mV. Note that most of fEPSPs (6 of 10) from DM have multiple peaks.

Field potential recordings

After incubation in ACSF, the spinal cord slices were placed in a recording chamber equipped with an ACSF superfusion system. Recordings were made with a glass micropipette electrode (ACSF internal solution, 2 MΩ), and electrical stimulation was applied through a suction electrode attached to the cut end of the dorsal root (Fig. 1D). fEPSPs in response to dorsal root stimulation (test stimulus) were recorded and amplified using the Multiclamp 700B (Axon Instruments). Data were collected and analyzed using pCLAMP (Axon Instruments). Recording temperature was kept at 30°C.

The parameter of test stimuli for Aβ-fibers was 30–50 μA (0.5 ms) and that for C-fibers was 1–1.2 mA (0.5 ms). Test stimuli were delivered once every 30 s (4 times every 2 min). From each recorded tracing, the slope of fEPSP was measured between 10 and 90% of the fEPSP peak amplitude. Each presented fEPSP slope value is an average of four individual fEPSP recordings obtained during the designated 2-min period. Baseline responses were recorded for 20 min before any experimental manipulations.

To avoid contamination from Aδ- and C-fiber-evoked events, Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs were identified based on the following two criteria: the fEPSPs with a clear first peak and a constant latency. The latency between the stimulus artifact and the beginning of fEPSPs was measured and used for conduction velocity calculation. The fEPSPs that were evoked by stimuli of Aβ-fiber intensities and had Aβ-fiber latencies were considered as Aβ-fiber evoked fEPSPs.

To find the most suitable location for recording of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs, we initially recorded fEPSPs from four different locations in the spinal dorsal horn while stimulating the dorsal root with Aβ fiber intensities (Fig. 1E). These four areas include superficial medial [SM; medial part of the substantia gelatinosa (SG)], superficial lateral (SL: lateral part of SG), deep medial (DM: medial part of lamina IV-V), and deep lateral (DL: lateral part of lamina IV-V) dorsal horn. Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs were recorded routinely from the medial (SM and DM) region but rarely from the lateral (SL and DL) region. The fEPSPs recorded from the SM usually showed a monophasic wave form with a single peak. The fEPSPs recorded from the DM, however, frequently showed a complex wave form with multiple peaks, which made it difficult to analyze. From the recordings made in 10 preparations, a single peak wave form was observed in 8 of 10 from SM but 2 of 8 from DM. No single peak wave form was recorded from the SL and DL. Based on these results, all fEPSP recordings in this study were made from the SM region of the dorsal horn. The superficial dorsal horn encompasses substantia gelatinosa and can be identified as a distinctive translucent band across the dorsal part of the dorsal horn as shown in Fig. 1D.

To induce spinal cord LTP, the cut end of the dorsal root was stimulated with high-frequency stimulation (HFS) with a suction electrode. The parameters of HFS are 1-s-long trains of pulses (100 Hz, 1.2 mA, 0.5 ms) repeated five times at 10-s intervals that activate C-fibers. The HFS used in this study consistently induced a prolonged increase of fEPSP slope values >20% compared with the pre-HFS control levels, which condition was defined as LTP.

Pharmacological compounds

For pharmacological studies, compounds were dissolved in an ACSF superfusion solution at various concentrations immediately before use. N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN), 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl (TEMPOL), and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). d-(+)-2-amino-5-phosphopentanoic acid (d-AP5) and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxalin-2,3-dione (CNQX) were purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO). PBN and TEMPOL were used as ROS scavengers and t-BOOH was used as a ROS donor. PBN is a nonspecific ROS scavenger while TEMPOL acts as a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic. A NMDA receptor antagonist, d-AP5, and an AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist, CNQX, were prepared as a 1,000× stock solution and then diluted in ACSF before use.

Statistical analysis

The slope values of four consecutive fEPSPs evoked every 30 s were averaged to produce one slope value for each 2-min interval, and data are presented as single slope values. The average and variability (SE) of the slope value data from multiple preparations (spinal cord slices) were plotted at 2-min intervals in the figures. The values at the mid time points during control period (e.g., 10–12 min of 20 min of control) as well as after certain manipulations (drug application or HFS) were used for statistical comparisons of means. The statistical evaluations were made by using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Test stimulus parameters for A- and C-fibers

The ranges of stimulus intensities required to activate Aβ-, Aδ-, and C-fibers were 32 ± 8, 68 ± 18, and 850 ± 67 μA with 0.5-ms stimulus pulse duration, respectively (Fig. 1, B and C, and Table 1, n = 5). No Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked response was detected with stimulus intensities <25 and 700 μA (0.5 ms), respectively. The conduction velocities of Aβ-, Aδ-, and C-fibers were 15.7 ± 3.8, 8.6 ± 2, and 1.1 ± 0.2 m/s, respectively. Based on these results, the stimulus intensities of 30–50 μA (0.5 ms) and 1–1.2 mA (0.5 ms) were selected to evoke Aβ- and C-fiber-mediated fEPSPs, respectively, in spinal cord slice preparation. These stimulus parameters are similar to those used in other studies of spinal cord LTP (Ikeda et al. 1998; Sandkuhler et al. 1997; Schneider and Perl 1988).

Table 1.

Compound action potential

| Threshold, μA |

Conduction Velocity, m/s |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ | Aδ | C | Aβ | Aδ | C | |

| Means ± SE | 32 ± 8 | 68 ± 18 | 850 ± 67 | 15.7 ± 3.8 | 8.6 ± 2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

Examples of Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs are shown in Fig. 2, B and C, respectively. Treatment with an AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist, CNQX (20 μM), completely blocked both Aβ- and C-fibers-evoked fEPSPs within 3–5 min after the drug treatment (n = 5). An example of CNQX effect on Aβ-fibers-evoked fEPSPs is shown in Fig. 1D. Thus the data indicate that the recorded fEPSPs are mediated by postsynaptic glutamate AMPA and kainate receptors.

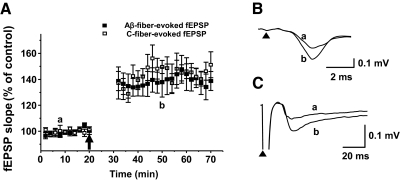

Fig. 2.

Recordings of Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs before and after LTP induction in spinal cord slices. A: each fEPSP slope value is the average of 4 recordings made every 2 min in each specimen and then averaged again from the recordings of 6 different specimens. Slope values were plotted as percent of control against time (n = 6). The intensities of test stimuli to elicit Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs were 30–50 μA (0.5-ms duration) and 1–1.2 mA (0.5-ms duration), respectively. Baseline fEPSPs in response to the test stimuli were recorded for 20 min. The conditioning high-frequency stimuli (HFS), which consisted of 5 1-s trains of 100-Hz pulses (1.2 mA, 0.5 ms) given at 10-s intervals, were delivered at 20 min (↑). After HFS, recording was paused for 10 min for stabilization of preparation. Responses to test stimuli were then recorded for an additional 40 min. The slopes of fEPSPs were significantly increased after HFS, indicating the induction of LTP. B and C: examples of Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSP recordings before (a) and after (b) HFS. ▲, stimulus artifacts.

HFS induces LTP of Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs through NMDA receptor activation

The Aβ- and C-fiber evoked fEPSPs were recorded for 20 min before LTP induction by high-frequency stimulation and used as baseline responses. The fEPSPs were also recorded for 40 min starting 10 min after HFS, and the summary data are shown in Fig. 2A (n = 6). Examples of Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSP recordings at baseline (a) and after LTP induction (b) are shown in Fig. 2, B and C, respectively. The slope values of four fEPSP recordings (30-s intervals) made over a 2-min period were averaged and the summary data of relative averaged slope values are plotted in Fig. 2A. After conditioning HFS with C-fiber intensity [1-s-long trains of pulses (100 Hz, 1.2 mA, 0.5 ms) repeated five times at 10-s intervals], ∼71% of spinal cord slices (41/58) showed a >20% enhancement of the slopes of the Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs (Fig. 2, A–C). On average, the slopes of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs at 30 min after HFS showed an increase to 140 ± 9% (mean ± SE; n = 6) and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs showed an increase to 144 ± 8% (n = 6) after HFS compared with pre-HFS control levels (Fig. 2A).

On the other hand, when HFS (100 Hz) was delivered with Aβ-fiber intensity (30–50 μA, 0.5 ms), spinal cord LTP was induced in 2 of 10 tested spinal cord slices (20%). Low-frequency stimulation (20 Hz) with C-fiber intensity yielded LTP induction in 3 of 10 slices (30%). Thus the data indicate that although it is possible to induce LTP with either HFS with Aβ-fiber intensities or low-frequency stimulation with C-fiber intensities, the probability of LTP induction was too low to be useful. Thus HFS with C-fiber intensity, although parameters are artificial and nonphysiological, was used to induce LTP in this study. The data also suggest that the enhanced fEPSPs by Aβ-fiber stimuli, suggesting LTP at Aβ-fiber synapses, may be heterosynaptic LTP because it requires C-fiber activation.

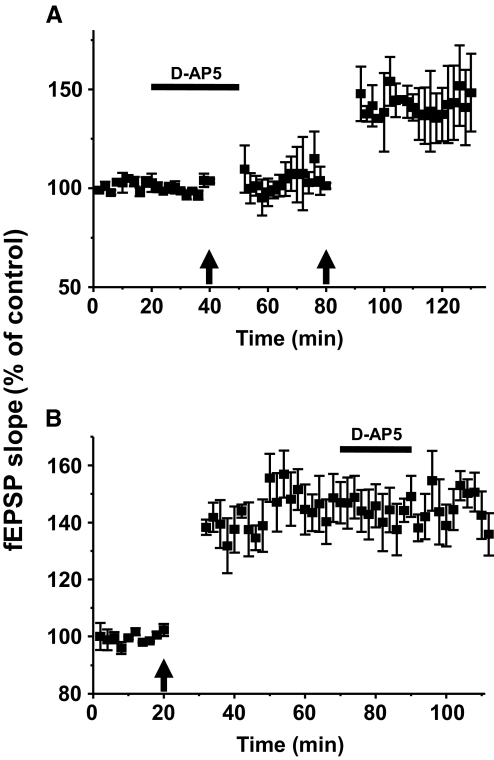

To determine whether NMDA receptors are involved in LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs, we examined the effects of an NMDA receptor antagonist, d-AP5, on the induction and maintenance phases of the LTP. As shown in Fig. 3 A (n = 5), application of 50 μM of d-AP5 alone did not affect the baseline slopes of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. When conditioning HFS was delivered during the period of d-AP5 superfusion (30 min), the magnitudes of the fEPSPs at 20 min after HFS were not significantly changed (98 ± 7%) from the pre-HFS control values (100 ± 2%). When the same conditioning HFS was delivered after d-AP5 was washed out (indicated by the 2nd ↑ in Fig. 3A); however, the slopes of the fEPSPs at 20 min after HFS were significantly increased (154 ± 12% of control, P < 0.05, n = 5), showing the development of LTP in the absence of the NMDA receptor antagonist (Fig. 3A). Thus the data indicate that the induction of LTP by HFS is NMDA receptor dependent. On the other hand, when d-AP5 was applied (50 μM, for 20 min) after LTP was fully established, the magnitudes of fEPSPs were not changed compared with the pre-d-AP5 levels (P > 0.05, n = 6, Fig. 3B). These data indicate that NMDA receptor activation is necessary for the induction but not the maintenance of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs when it is induced by HFS.

Fig. 3.

LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs and the effect of a N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, d-AP5. A: LTP-inducing HFS (indicated by ↑) was delivered twice in spinal cord slices (n = 5). The first stimulation was delivered during the superfusion with 50 μM of d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5, indicated by the horizontal bar). The 2nd HFS was delivered 30 min after washing out the d-AP5 (2nd ↑ at 80 min). HFS failed to induce LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs in the presence of d-AP5, suggesting that NMDA receptor activation is essential for LTP induction by HFS. B: to test NMDA receptor involvement in maintenance phase of LTP, d-AP5 was applied after spinal cord LTP is fully established (n = 6) by HFS (↑). The results show that d-AP5 had no effect on the maintenance of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. The data suggest that NMDA receptor activation is necessary for the induction but not the maintenance of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs.

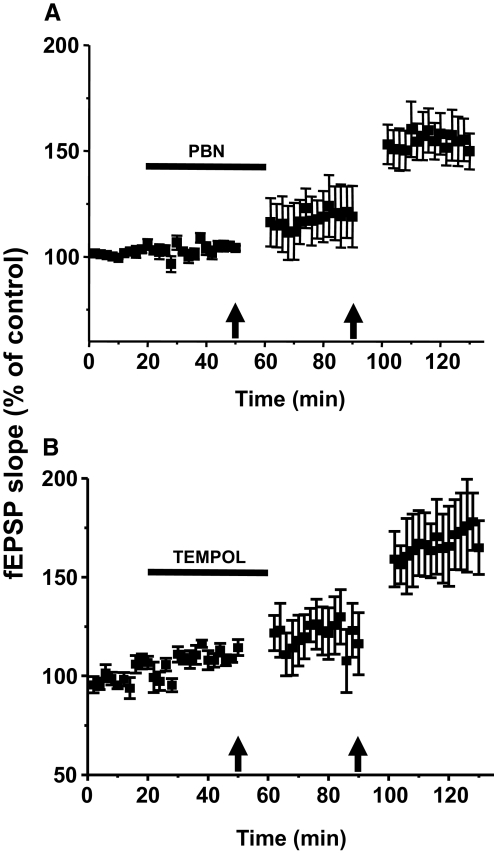

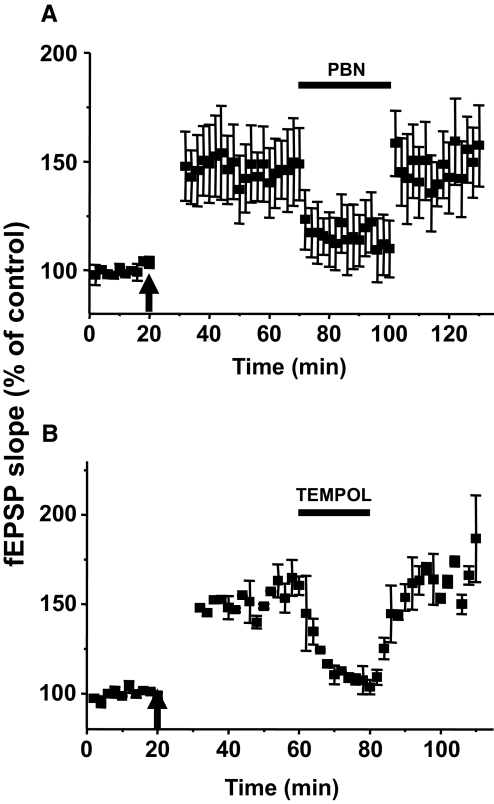

ROS scavengers block the induction of spinal cord LTP

First, we tested whether ROS are involved in the generation of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. After 20 min of control baseline Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSP recordings, the recording chamber was superfused with 1 mM PBN for 30 min, and Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs were recorded during the entire PBN superfusion period. The magnitude of fEPSP slopes during PBN treatment was not significantly different from that of the pretreatment baseline values (P > 0.05, n = 6, Fig. 4 A), thus indicating that ROS are not involved in baseline responses. To determine whether ROS play a role in the induction of LTP, the same conditioning HFS was delivered twice: once during the PBN infusion and then 30 min after PBN was washed out with ACSF. When HFS was delivered during PBN (1 mM) treatment, the Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs at 20 min after HFS were increased slightly but significantly (121 ± 14%, HFS with PBN, P < 0.05, n = 6) compared with the pre-HFS values (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, when the second HFS was delivered 30 min after washing out the PBN (HFS without PBN), the slope magnitudes of fEPSPs recorded at 20 min after HFS increased to 172 ± 18% (Fig. 4A), and this value is highly significant compared with the results with PBN (P < 0.001, n = 6).

Fig. 4.

The effect of a ROS scavenger [1 mM of N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN), n = 6, A] and superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetics [5 mM of 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl (TEMPOL), n = 3, B] on the induction of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. After 20 min of baseline recordings of fEPSPs, drug was superfused for 40 min as indicated by the horizontal bar (from the 20th to 60th min). HFS was delivered twice, 10 min before the end of drug superfusion and 30 min after washing out drug as indicated (↑). The data show that HFS-induced spinal cord LTP is blocked in the presence of PBN and TEMPOL but restored when those were washed out.

To confirm the role of ROS in the induction of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs, we also tested the effect of another ROS scavenger, TEMPOL (Fig. 4B). In contrast to the nonspecific overall ROS scavenging effect of PBN, TEMPOL acts mainly as a mimetic of superoxide dismutase. The mean slope value of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs during 30 min TEMPOL treatment (5 mM) did not change compared with the baseline (P > 0.05, n = 3). Thus TEMPOL alone has no effect on fEPSPs under normal conditions. When HFS was delivered during TEMPOL (5 mM) treatment, the fEPSPs were not increased compared with the baseline (P > 0.05, n = 3). On the other hand, when the second HFS was delivered after TEMPOL was washed out (HFS without TEMPOL), the slope magnitudes of fEPSPs were increased significantly (P < 0.05, n = 3). These data indicate that ROS play a critical role for induction of spinal cord LTP.

ROS are involved on the maintenance phase of spinal cord LTP

To test the role of ROS in the maintenance of spinal cord LTP, the effects of a ROS scavenger, PBN, on Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs were examined after LTP induction by HFS. After confirming the induction of LTP following HFS, the recording chamber was superfused with 1 mM of PBN for 30 min and then flushed with ACSF. The data obtained from six slice preparations are shown in Fig. 5 A. The fEPSP slopes were increased significantly after HFS (n = 6), thus confirming LTP development. Ten minutes after PBN application, the slopes of fEPSPs fell to 114 ± 12%, which is significantly lower than the levels in LTP state (at 10 min after HFS, 152 ± 18%), thus showing a reversal of LTP by PBN (P < 0.05; n = 6; Fig. 5A). When PBN was washed out, the slopes of the fEPSPs increased back to 158 ± 15% (at 10 min after washing out), indicating that LTP is reestablished.

Fig. 5.

The effect of ROS scavengers, PBN and TEMPOL, on the maintenance of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. A: Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs before and after HFS (↑) and during PBN application (n = 6). Fifty minutes after HFS, the spinal cord slice was superfused with 1 mM PBN for 30 min (indicated by a horizontal bar). fEPSPs were recorded for an additional 30 min after washing out the PBN. B: the same experiment as A was repeated with 5 mM TEMPOL for 20 min instead of PBN for 30 min (n = 5). The data suggest that ROS are involved in the maintenance of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs.

To confirm the role of ROS in the enhancement of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs, we tested another ROS scavenger TEMPOL. When TEMPOL (5 mM) was applied to spinal cord slices for 20 min, it greatly reduced LTP. The fEPSPs recorded 10 min after TEMPOL treatment were significantly decreased compared with the potentiated fEPSPs at 20 min after HFS (from 148 ± 6 to 110 ± 5%, P < 0.001, n = 5), as shown in Fig. 5B. Thus both ROS scavengers, PBN and TEMPOL, reduce LTP, suggesting the involvement of ROS in the maintenance phase of spinal cord LTP.

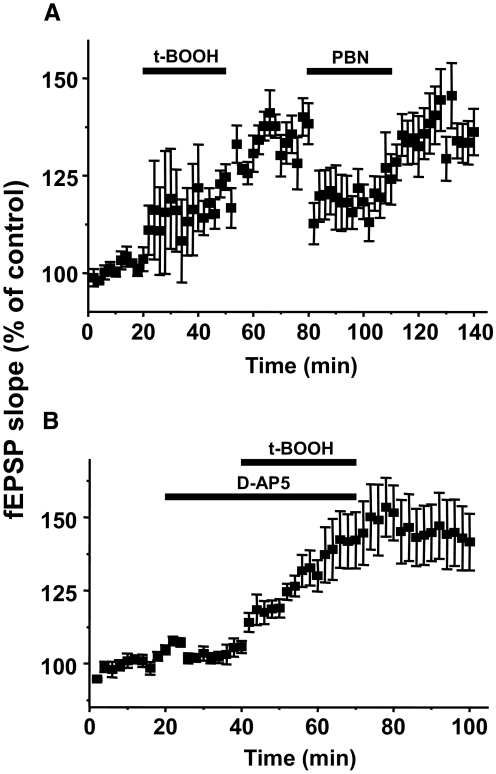

ROS donor, t-BOOH, induces spinal cord LTP independent from NMDA receptor activation

Thus far, this study shows that ROS are critical for the development and maintenance of spinal cord LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs following HFS of primary afferents. The question then arises whether ROS alone is sufficient to induce spinal cord LTP. To test this, we examined the effect of a ROS donor, t-BOOH, on fEPSPs. After 20-min recordings of baseline Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs, 5 mM of t-BOOH was superfused for 30 min and fEPSPs were recorded during t-BOOH application, as shown in Fig. 6 A. There was a gradual potentiation of fEPSPs during the t-BOOH superfusion and a further significant increase for another 30 min compared with control, reaching 138 ± 5% at 30 min after washing out t-BOOH (P < 0.05, n = 6). This indicates that t-BOOH alone can induce and maintain LTP-like potentiation of fEPSPs. The potentiated fEPSPs were subsequently attenuated to 119 ± 8% of control at 10 min after 1 mM PBN treatment and then returned to high LTP levels (135 ± 6%) at 10 min after PBN was removed. The data show that exogenously supplied ROS can produce an enhancement of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs in the spinal cord, thus mimicking the HFS-induced spinal cord LTP. The data suggest that ROS are both necessary and sufficient for the induction of spinal cord LTP.

Fig. 6.

Induction of LTP of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs by a ROS donor, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH), and its relationship to NMDA receptor activation. A: changes in the averaged relative slope values of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs with superfusion of t-BOOH (5 mM, 30 min) and then PBN (1 mM, 30 min). The fEPSP slopes were gradually increased during t-BOOH superfusion and further thus reached a significantly potentiated fEPSP, LTP state, by 60–80 min after initiation of t-BOOH (n = 6). PBN (1 mM) superfuion (80–110 min) after washing out t-BOOH (30 min) significantly reduced fEPSPs that were potentiated by t-BOOH. B: the effect of a NMDA receptor antagonist d-AP5 on t-BOOH induced spinal cord LTP. Application of d-AP5 (50 μM, 20 min) did not change the baseline Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. When t-BOOH (5 mM, 30 min) is also added to the bath, fEPSPs gradually increased and reached to greatly potentiated fEPSPs. These potentiated fEPSPs were sustained another 40 min after removal of both d-AP5 and t-BOOH. The data show that t-BOOH induce spinal cord LTP is independent from NMDA receptor activation.

Because both NMDA receptors and ROS are involved in the induction of spinal cord LTP (Figs. 3A and 4), it became important to investigate the relationship of these two factors. To test this, we examined the effect of NMDA receptor antagonist d-AP5 on t-BOOH-induced LTP. As shown in Fig. 6B, d-AP5 failed to block the potentiation of Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs (P < 0.05, n = 6) in 30 min t-BOOH (5 mM) superfusion, although it did block the LTP induced by HFS (Fig. 3A). This experiment was repeated in six different preparations with the same result, thus showing that NMDA receptors are necessary when spinal LTP is induced by HFS but not by a ROS donor, suggesting that the involvement of ROS in spinal cord LTP may be a downstream event following NMDA receptor activation.

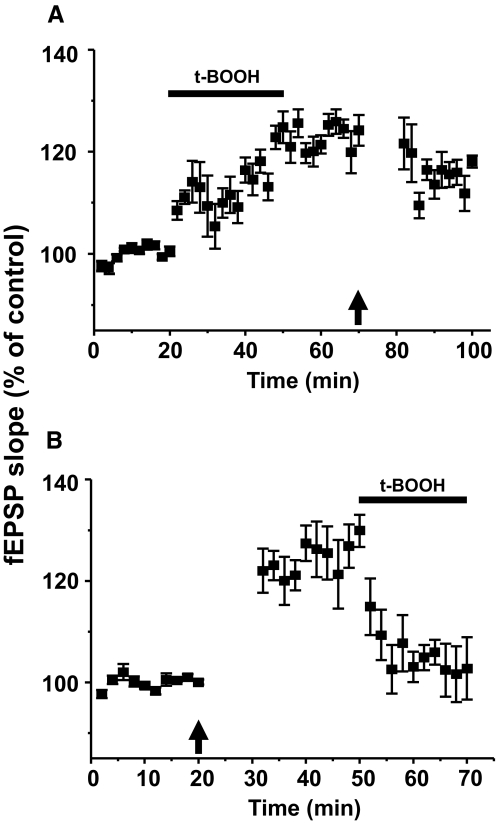

Spinal cord LTP induced by a ROS donor occludes HFS-induced LTP

Based on the preceding data, we deduce that HFS activates the NMDA receptors on spinal dorsal horn neurons, which leads to endogenous ROS generation, and then ROS leads to the development and maintenance of spinal cord LTP. This hypothesis thus predicts that LTP induced by HFS will occlude with that induced by a ROS donor or vice versa. To test this hypothesis, we performed occlusion experiments, and results are shown in Fig. 7. In one preparation, LTP was induced by a ROS donor, t-BOOH (5 mM), and then HFS was delivered after LTP is clearly established. As shown in Fig. 7A, the slopes of fEPSPs at 20 min after t-BOOH treatment were significantly increased compared with the pre-t-BOOH levels (from 100 ± 0.5 to 124 ± 3%, P < 0.05, n = 6), thus showing induction of LTP. When HFS was delivered to this LTP condition (↑), the slopes of fEPSPs were slightly attenuated (114 ± 1%, P < 0.05, n = 6) rather than enhanced at 20 min after HFS. When the sequence of LTP induction methods were reversed (Fig. 7B), the LTP established by HFS was significantly reduced at 10 min after t-BOOH treatment (from 126 ± 5 to 103 ± 3%, P < 0.05, n = 6). The data thus suggest that either manipulation can generate ROS that are sufficient for LTP induction and both manipulations share the same downstream mechanism in that overproduction of ROS beyond the optimal level by both manipulations may be detrimental to LTP.

Fig. 7.

LTP induced by a reactive oxygen species (ROS) donor attenuated HFS-induced LTP and vice versa. A: after 20 min of baseline recordings of fEPSPs, 5 mM of t-BOOH was superfused for 30 min as indicated by the horizontal bar (n = 6). After confirming the development of potentiated fEPSPs, t-BOOH was washed out for 20 min and then HFS (↑) was delivered. Enhanced fEPSPs by t-BOOH were moderately attenuated after HFS (n = 6, P < 0.05). B: the sequence of LTP induction methods were reversed in this experiment (n = 6). Thus HFS (↑) was delivered after 20 min baseline recordings to induce spinal cord LTP. When LTP was established 30 min after HFS, 5 mM of t-BOOH was superfused into the bath (20 min). fEPSPs were greatly attenuated (n = 6, P < 0.001) during t-BOOH application. These data indicate that LTP induction by t-BOOH is occluded by that of HFS and vice versa. The significant reduction of fEPSPs after the 2nd LTP induction stimulus indicates that too high levels of ROS (beyond that necessary to maintain LTP) due to added stimulus, seem to interfere with LTP.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that HFS of the dorsal root induces an enhancement of both Aβ- and C-fiber-evoked fEPSPs of the spinal dorsal horn, thus indicating the development of spinal cord LTP. The ROS scavengers reduce the induction and maintenance of spinal cord LTP. Spinal cord LTP is mimicked by a ROS donor, t-BOOH, and this is reduced by a ROS scavenger. These data suggest that ROS are both essential and sufficient for induction and maintenance of spinal cord LTP. The induction, but not the maintenance, of spinal cord LTP is dependent on NMDA receptors when induced by HFS. The induction of spinal cord LTP by t-BOOH, however, is not dependent on NMDA receptor activation. Thus it seems reasonable to speculate that NMDA receptor activation following HFS leads to spinal ROS elevation, which in turn induces spinal cord LTP. The data suggest that the involvement of ROS in spinal cord LTP may be a downstream event following NMDA receptor activation.

The CNS has multiple possible sources of ROS. They include various enzyme activities, such as monoamine oxidase, cyclooxygenase, nitric oxide synthase, and NADPH oxidase, as well as mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (Chetkovich et al. 1993; Kukreja et al. 1986; Pou et al. 1992). Biologically important ROS are also multiples: such as superoxide, hydroxyl radical, hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide, peroxinitrite, etc. Among these, three different types of ROS have been proposed to be involved in the LTP process: 1) superoxide generated from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (Jenner 1994) and cyclooxygenase reaction, 2) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) produced through enzymatic or chemical dismutation (Dringen et al. 2005), and 3) nitric oxide (NO) generated from l-arginine by NO synthase (Garthwaite and Boulton 1995). Of these, mitochondria are considered the major ROS source in LTP because superoxide is a natural metabolic byproduct of the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation process that increases during enhanced Ca2+ signaling (Dugan et al. 1995; Dykens 1994; Reynolds and Hastings 1995). Studies on isolated mitochondria indicate that Ca2+ accumulation causes leakage of electrons from the respiratory chain and increases the production of superoxide (Castilho et al. 1995). In cultured cortical neurons, Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial superoxide production is also observed after NMDA receptor activation (Dugan et al. 1995; Gunasekar et al. 1995; Reynolds and Hastings 1995). Furthermore, superoxide generation during hippocampal LTP induction (Bindokas et al. 1996) and inhibition of hippocampal LTP by superoxide dismutase (Klann 1998) strongly support the involvement of superoxide in LTP induction in the hippocampus. Superoxide accumulation due to MnSOD (SOD2) inactivation by nitration is also observed in the spinal dorsal horn neurons in capsaicin-induced persistent pain (Schwartz et al. 2009). A great reduction of spinal cord LTP by a superoxide dismutase mimetic, TEMPOL, shown in this study, further supports that superoxide may be a critical type of ROS in spinal cord LTP. Another type of ROS that has shown to be involved in synaptic plasticity is NO generated by activation of NO synthase (NOS). NOS activity is increased not only in hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Schuman and Madison 1991; Zorumski and Izumi 1993) but also in capsaicin-induced central sensitization in the spinal cord (Meller and Gebhart 1993; Wu et al. 1998, 2001). In addition, NO, produced from postsynaptic neurons as a consequence of NMDA receptor activation, is shown to serve as a retrograde messenger to enhance glutamate release from presynaptic terminals (Arancio et al. 1996; Schuman and Madison 1991; Xu et al. 2007). While it is shown that the induction of LTP is initiated postsynaptically by Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors, the maintenance of LTP can be greatly influenced by presynaptic transmitter release. Thus NO as a retrograde messenger could be an important contributor for spinal cord LTP. Because either a NOS inhibitor (Osborne and Coderre 1999) or a SOD mimetic (Tal 1996; Wang et al. 2004) interfere with the development of pain, both NO and superoxide are likely ROS involved in pain and central sensitization. The role of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), however, is open to dispute. A brief exposure of brain slices to H2O2 induces LTP in the hippocampus (Katsuki et al. 1997; Thiels et al. 2000b). However, extended exposure of hippocampal slices to either a low or a high concentration of H2O2 reduces or completely blocks LTP (Auerbach and Segal 1997; Pellmar et al. 1991). One explanation for this apparent contradiction is that H2O2 generation may be a necessary step for the full expression of LTP, but too high a concentration of H2O2 or prolonged exposure to exogenous H2O2 may interfere with LTP. The significant reduction of fEPSPs after t-BOOH application on already established spinal cord LTP may also represent the case of too high a level of ROS having a negative impact on LTP, as shown in this study (Fig. 7). Taking all these together, we speculate that superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and NO are all likely candidate ROS contributing to LTP of the spinal cord. The relationships among these different types of ROS and their exact mechanism in spinal cord LTP and central sensitization need to be further investigated in future studies.

The present data show that ROS scavengers do not depress fEPSPs in the control state but transiently depress fEPSPs after LTP, suggesting that elevated ROS levels in the spinal cord are linked to the maintenance of spinal cord LTP. There is a basal level of ROS production in a normal physiological condition, and multiple endogenous antioxidant mechanisms (such as MnSOD in mitochondria and CuZnSOD in the cytosol) maintain the level of ROS very low normally (McCord and Fridovich 1969). That must be the reason why ROS scavengers do not produce any effect, because there are not many ROS to scavenge or influence cell function. On the other hand, data show that ROS scavengers depress fEPSPs after LTP. A possible explanation is that ROS production is somehow greatly increased in LTP condition, thus higher than normal levels of ROS are maintained during LTP. This high level of ROS is an important contributor to LTP, possibly acting as intracellular signaling molecules. Removal of excessive ROS by scavengers consequently reduces the level of LTP transiently until the high level of ROS is restored by increased production.

It is not known how elevated spinal ROS enhance responsiveness of the dorsal horn neurons. In both hippocampal CA1 neurons and spinal dorsal horn neurons, induction of LTP is dependent on postsynaptic Ca2+ influx after NMDA receptor activation (Collingridge et al. 1983; Liu and Sandkuhler 1995; Malenka et al. 1988; Svendsen et al. 1998), which is triggered by HFS of afferent fibers. Calcium influx, in turn, activates numerous signal transduction cascades, e.g., calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (Xia and Storm 2005; Yang et al. 2004), protein kinase C (PKC) (Klann et al. 1998; Yang et al. 2004), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Xin et al. 2006), which are known to be essential for LTP. In addition, several studies suggest that ROS also activate PKC and ERK2, both of which are shown to be activated after LTP-inducing stimulation and necessary for the induction of LTP (Kanterewicz et al. 1998; Klann et al. 1998). Thus it is reasonable to speculate that ROS act as intermediate steps between intracellular calcium increases and the activation of various kinases that are essential for LTP. In line with this idea, studies have shown that NMDA receptor activation results in calcium-dependent production of superoxide (Bindokas et al. 1996) and an increased PKC activation during hippocampal LTP (Klann et al. 1998; Knapp and Klann 2002; Thiels et al. 2000a). In addition, increased levels of spinal ROS are correlated with an increased phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunit 1 (NR1) through PKC activation in neuropathic rats (Gao et al. 2007). Thus the data suggest that ROS are acting as signaling molecules to activate PKC during LTP in the spinal cord as well as in the hippocampus. Future study is warranted to identify a definite connection between ROS and signal transduction cascades in spinal cord LTP.

First-order synapses of primary afferent terminals in the spinal cord are heterogeneous and arise from many different specialized afferents that can be selectively excited by specific stimuli and that have specific projection distribution patterns in the spinal cord (Magerl et al. 2001; Schmidt et al. 1995). Although the vast majority of SG neurons respond to high-threshold nociceptive inputs (Willis and Coggesahll 1991), an excitation of SG neurons by innocuous mechanical stimuli and Aβ-fiber electrical stimulation have been reported in in vivo studies (Bennett et al. 1980; Woolf and Fitzgerald 1983). Furthermore, Aβ fiber-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents detected from SG neurons were facilitated by peripheral inflammation when recorded from spinal cord slice preparations (Baba et al. 1999). Because Aβ fibers do not project directly to SG (Woolf 1987) and the dendrites of many SG neurons do not leave SG (Bennett et al. 1980), it is assumed that the Aβ fiber-evoked fEPSPs in the SG are the results of indirect synaptic relays from deeper laminae. Whether conveyed directly or indirectly, the SG cells seem to receive inputs not only from C-fibers but also from Aβ fibers and modify the output of projection neurons in lamina I as well as deep layers (laminae IV-VI) of the dorsal horn (Willis and Coggesahll 1991). Our fEPSP recordings from spinal cord slices confirm that conditioning HFS, which activates C-fibers, induces LTP of both C- and Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs. Aβ-fiber inputs that normally carry tactile sensation to the spinal cord have shown to produce pain in the spinal cord sensitized condition—touch-evoked pain. And ROS scavengers blocked Aβ-fiber-evoked fEPSPs in spinal cord LTP as well as touch-evoked pain in neuropathic animals (Kim et al. 2004). Based on these data, we speculate that ROS may be involved in potentiation of synaptic excitability of dorsal horn neurons receiving low-threshold afferent fiber input, which is considered the basis of allodynia in chronic pain (Schmidt and Willis 2007). However, it is still possible that the present data reflect a potentiation of the activity of purely nonnociceptive spinal neurons because it is not clear if the recorded signals come from the activity of nonnociceptive spinal neurons or spinal neurons receiving input from both nociceptive and nonnociceptive afferents.

As a technical issue, this study used HFS at C-fiber intensity as a conditioning stimulus to induce spinal cord LTP. This is the most frequently used conditioning stimulation to induce LTP in the brain and spinal cord both in vivo and in vitro (Ikeda et al. 2003; Randic et al. 1993; Sandkuhler 2007). HFS produces highly reliable LTP induction in the present study as well. The physiological relevance of this HFS, however, is not clear at this time since primary C-fiber afferents do not normally fire beyond a few spikes per second (Ji et al. 2003). Nevertheless, Duggan et al. (1995) and Liu and Sandkuhler (1997) have shown that bursts of 100-Hz stimulation of C-fibers are more effective than bursts of 20-Hz stimulation or prolonged 2-Hz stimulation. Furthermore, dorsal horn AMPA-receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic potentials remain potentiated for tens of minutes following brief HFS (Ji et al. 2003; Randic et al. 1993). Therefore we used this same brief HFS as a convenient experimental tool to elicit potent LTP.

In summary, the results of the present study suggest that ROS play a critical role in both induction and maintenance of spinal cord LTP. The data also suggest that ROS may act as intracellular signaling molecules activating various signaling cascades situated downstream from NMDA receptor activation during the induction of spinal cord LTP following HFS.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants R01 NS-31680 and P01 NS-11255.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to J. Yowtak and D. Broker for excellent assistance in editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Arancio O, Kiebler M, Lee CJ, Lev-Ram V, Tsien RY, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Nitric oxide acts directly in the presynaptic neuron to produce long-term potentiation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Cell 87: 1025–1035, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JM, Segal M. Peroxide modulation of slow onset potentiation in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 17: 8695–8701, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Doubell TP, Woolf CJ. Peripheral inflammation facilitates Abeta fiber-mediated synaptic input to the substantia gelatinosa of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 19: 859–867, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Abdelmoumene M, Hayashi H, Dubner R. Physiology and morphology of substantia gelatinosa neurons intracellularly stained with horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol 194: 809–827, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindokas VP, Jordan J, Lee CC, Miller RJ. Superoxide production in rat hippocampal neurons: selective imaging with hydroethidine. J Neurosci 16: 1324–1336, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 361: 31–39, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilho RF, Kowaltowski AJ, Meinicke AR, Bechara EJ, Vercesi AE. Permeabilization of the inner mitochondrial membrane by Ca2+ ions is stimulated by t-butyl hydroperoxide and mediated by reactive oxygen species generated by mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med 18: 479–486, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetkovich DM, Klann E, Sweatt JD. Nitric oxide synthase-independent long-term potentiation in area CA1 of hippocampus. Neuroreport 4: 919–922, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Kehl SJ, McLennan H. Excitatory amino acids in synaptic transmission in the Schaffer collateral-commissural pathway of the rat hippocampus. J Physiol 334: 33–46, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contestabile A. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Curr Top Med Chem 1: 553–568, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AJ, Woolf CJ, Wall PD, McMahon SB. Dynamic receptive field plasticity in rat spinal cord dorsal horn following C-primary afferent input. Nature 325: 151–153, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dringen R, Pawlowski PG, Hirrlinger J. Peroxide detoxification by brain cells. J Neurosci Res 79: 157–165, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Sensi SL, Canzoniero LM, Handran SD, Rothman SM, Lin TS, Goldberg MP, Choi DW. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species in cortical neurons following exposure to N-methyl-d-aspartate. J Neurosci 15: 6377–6388, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens JA. Isolated cerebral and cerebellar mitochondria produce free radicals when exposed to elevated CA2+ and Na+: implications for neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 63: 584–591, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Kim HK, Chung JM, Chung K. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in enhancement of NMDA-receptor phosphorylation in animal models of pain. Pain 131: 262–271, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J, Boulton CL. Nitric oxide signaling in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Physiol 57: 683–706, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekar PG, Kanthasamy AG, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. NMDA receptor activation produces concurrent generation of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species: implication for cell death. J Neurochem 65: 2016–2021, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Synaptic plasticity in spinal lamina I projection neurons that mediate hyperalgesia. Science 299: 1237–1240, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Ryu PD, Park JB, Tanifuji M, Asai T, Murase K. Optical responses evoked by single-pulse stimulation to the dorsal root in the rat spinal dorsal horn in slice. Brain Res 812: 81–90, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Oxidative damage in neurodegenerative disease. Lancet 344: 796–798, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization and LTP: do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci 26: 696–705, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanterewicz BI, Knapp LT, Klann E. Stimulation of p42 and p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases by reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide in hippocampus. J Neurochem 70: 1009–1016, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki H, Nakanishi C, Saito H, Matsuki N. Biphasic effect of hydrogen peroxide on field potentials in rat hippocampal slices. Eur J Pharmacol 337: 213–218, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Park SK, Zhou JL, Taglialatela G, Chung K, Coggeshall RE, Chung JM. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play an important role in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Pain 111: 116–124, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann E. Cell-permeable scavengers of superoxide prevent long-term potentiation in hippocampal area CA1. J Neurophysiol 80: 452–457, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann E, Roberson ED, Knapp LT, Sweatt JD. A role for superoxide in protein kinase C activation and induction of long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem 273: 4516–4522, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp LT, Klann E. Potentiation of hippocampal synaptic transmission by superoxide requires the oxidative activation of protein kinase C. J Neurosci 22: 674–683, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreja RC, Kontos HA, Hess ML, Ellis EF. PGH synthase and lipoxygenase generate superoxide in the presence of NADH or NADPH. Circ Res 59: 612–619, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kim HK, Kim JH, Chung K, Chung JM. The role of reactive oxygen species in capsaicin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and in the activities of dorsal horn neurons. Pain 133: 9–17, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XG, Sandkuhler J. Long-term potentiation of C-fiber-evoked potentials in the rat spinal dorsal horn is prevented by spinal N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor blockage. Neurosci Lett 191: 43–46, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Sandkuhler J. Characterization of long-term potentiation of C-fiber-evoked potentials in spinal dorsal horn of adult rat: essential role of NK1 and NK2 receptors. J Neurophysiol 78: 1973–1982, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XG, Sandkuhler J. Activation of spinal N-methyl-d-aspartate or neurokinin receptors induces long-term potentiation of spinal C-fiber-evoked potentials. Neuroscience 86: 1209–1216, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magerl W, Fuchs PN, Meyer RA, Treede RD. Roles of capsaicin-insensitive nociceptors in cutaneous pain and secondary hyperalgesia. Brain 124: 1754–1764, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Kauer JA, Zucker RS, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic calcium is sufficient for potentiation of hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science 242: 81–84, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JM, Fridovich I. The utility of superoxide dismutase in studying free radical reactions. I. Radicals generated by the interaction of sulfite, dimethyl sulfoxide, and oxygen. J Biol Chem 244: 6056–6063, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller ST, Gebhart GF. Nitric oxide (NO) and nociceptive processing in the spinal cord. Pain 52: 127–136, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne MG, Coderre TJ. Effects of intrathecal administration of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Br J Pharmacol 126: 1840–1846, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellmar TC, Hollinden GE, Sarvey JM. Free radicals accelerate the decay of long-term potentiation in field CA1 of guinea pig hippocampus. Neuroscience 44: 353–359, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pou S, Pou WS, Bredt DS, Snyder SH, Rosen GM. Generation of superoxide by purified brain nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 267: 24173–24176, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randic M, Jiang MC, Cerne R. Long-term potentiation and long-term depression of primary afferent neurotransmission in the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 13: 5228–5241, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds IJ, Hastings TG. Glutamate induces the production of reactive oxygen species in cultured forebrain neurons following NMDA receptor activation. J Neurosci 15: 3318–3327, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvemini D, Doyle TM, Cuzzocrea S. Superoxide, peroxynitrite and oxidative/nitrative stress in inflammation. Biochem Soc Trans 34: 965–970, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkuhler J. Learning and memory in pain pathways. Pain 88: 113–118, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkuhler J. Understanding LTP in pain pathways. Mol Pain 3: 9, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkuhler J, Chen JG, Cheng G, Randic M. Low-frequency stimulation of afferent Adelta-fibers induces long-term depression at primary afferent synapses with substantia gelatinosa neurons in the rat. J Neurosci 17: 6483–6491, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Schmelz M, Forster C, Ringkamp M, Torebjork E, Handwerker H. Novel classes of responsive and unresponsive C nociceptors in human skin. J Neurosci 15: 333–341, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Willis WD. Encyclopedia of Pain New York: Springer, 2007, vol. 1 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SP, Perl ER. Comparison of primary afferent and glutamate excitation of neurons in the mammalian spinal dorsal horn. J Neurosci 8: 2062–2073, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman EM, Madison DV. A requirement for the intercellular messenger nitric oxide in long-term potentiation. Science 254: 1503–1506, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz ES, Kim HY, Wang J, Lee I, Klann E, Chung JM, Chung K. Persistent pain is dependent on spinal mitochondrial antioxidant levels. J Neurosci 29: 159–168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz ES, Lee I, Chung K, Chung JM. Oxidative stress in the spinal cord is an important contributor in capsaicin-induced mechanical secondary hyperalgesia in mice. Pain 138: 514–524, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen F, Tjolsen A, Hole K. AMPA and NMDA receptor-dependent spinal LTP after nociceptive tetanic stimulation. Neuroreport 9: 1185–1190, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal M. A novel antioxidant alleviates heat hyperalgesia in rats with an experimental painful peripheral neuropathy. Neuroreport 7: 1382–1384, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E, Kanterewicz BI, Knapp LT, Barrionuevo G, Klann E. Protein phosphatase-mediated regulation of protein kinase C during long-term depression in the adult hippocampus in vivo. J Neurosci 20: 7199–7207, 2000a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E, Urban NN, Gonzalez-Burgos GR, Kanterewicz BI, Barrionuevo G, Chu CT, Oury TD, Klann E. Impairment of long-term potentiation and associative memory in mice that overexpress extracellular superoxide dismutase. J Neurosci 20: 7631–7639, 2000b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Porreca F, Cuzzocrea S, Galen K, Lightfoot R, Masini E, Muscoli C, Mollace V, Ndengele M, Ischiropoulos H, Salvemini D. A newly identified role for superoxide in inflammatory pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 309: 869–878, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WD. Long-term potentiation in spinothalamic neurons. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 40: 202–214, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WD, Coggeshall RE. Sensory mechanisms of the spinal cord. New York: Plenum, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ. Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature 306: 686–688, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ. Central terminations of cutaneous mechanoreceptive afferents in the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 261: 105–119, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Fitzgerald M. The properties of neurones recorded in the superficial dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 221: 313–328, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Fang L, Lin Q, Willis WD. Nitric oxide synthase in spinal cord central sensitization following intradermal injection of capsaicin. Pain 94: 47–58, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Lin Q, McAdoo DJ, Willis WD. Nitric oxide contributes to central sensitization following intradermal injection of capsaicin. Neuroreport 9: 589–592, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z, Storm DR. The role of calmodulin as a signal integrator for synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 267–276, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin WJ, Gong QJ, Xu JT, Yang HW, Zang Y, Zhang T, Li YY, Liu XG. Role of phosphorylation of ERK in induction and maintenance of LTP of the C-fiber evoked field potentials in spinal dorsal horn. J Neurosci Res 84: 934–943, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Mabuchi T, Katano T, Matsumura S, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Sakimura K, Mishina M, Ito S. Nitric oxide (NO) serves as a retrograde messenger to activate neuronal NO synthase in the spinal cord via NMDA receptors. Nitric Oxide 17: 18–24, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HW, Hu XD, Zhang HM, Xin WJ, Li MT, Zhang T, Zhou LJ, Liu XG. Roles of CaMKII, PKA, and PKC in the induction and maintenance of LTP of C-fiber-evoked field potentials in rat spinal dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol 91: 1122–1133, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorumski CF, Izumi Y. Nitric oxide and hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Biochem Pharmacol 46: 777–785, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]