Abstract

Background

Although psoriasis is considered to have a “dual peak” in age of onset, currently no studies exist regarding the incidence of psoriasis in children.

Objective

The objective of this study is to determine the incidence of psoriasis in childhood.

Methods

A population-based incidence cohort of children aged <18 years first diagnosed with psoriasis between January 1, 1970 and December 31,1999 was assembled. The complete medical record of each child was reviewed and psoriasis diagnosis was validated by a confirmatory diagnosis in the medical record by a dermatologist or medical record review by a dermatologist. Age- and sex-specific incidence rates were calculated and were age- and sex-adjusted to 2000 U.S. white population.

Results

The overall age and sex adjusted annual incidence of pediatric psoriasis was 40.8 per 100,000 (95% confidence interval 1: 36.6, 45.1). When psoriasis diagnosis was restricted to dermatologist confirmed subjects in the medical record, the incidence was 33.2 per 100,000 (95% CI: 29.3, 37.0). Incidence of psoriasis in children increased significantly over time from 29.6 per 100,000 in 1970 to 1974 to 62.7 per 100,000 in 1995-1999 (p<0.001). Chronic plaque psoriasis was the most common type (73.7%), and the most commonly involved sites were the extremities (59.9%) and the scalp (46.8%).

Limitations

The population studied was a mostly Caucasian population in the upper Midwest.

Conclusion

The incidence of pediatric psoriasis increases with increasing age. There is no apparent “dual-peak” in incidence. The incidence of pediatric psoriasis increased in recent years in both boys and girls.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Psoriasis, Population-based study

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the skin, nails, and joints. It is quite common, with lifetime prevalence estimates commonly at 1-3% of the general population.2, 3 While several prevalence estimates exist in the literature, incidence studies are lacking, likely due to the difficulty in accurately documenting such cases and lack of standard diagnostic criteria.

Two studies performed at different time periods in Olmsted County, Minnesota, found an overall incidence of 57.6 per 100, 000 from 1980 through 1983 (adults and children), and 107.7 per 100, 000 from 1982 to 1991 (adults only).4, 5 A more recent study of both adults and children in the United Kingdom demonstrated an incidence of 140 per 100, 0006, suggesting that psoriasis incidence may be increasing over time. Indeed, our recent findings indicated that the incidence of adult-onset psoriasis increased significantly over the last three decades from 50.8 per 100,000 in 1970-74 to 100.5 per 100,000 in 1995-19997.

While two of the previous incidence studies included pediatric psoriasis patients, no studies to date have specifically examined the incidence of psoriasis from birth into adolescence. It is believed that approximately one-third of psoriatic patients develop the disease during childhood.8 The existence of “two incidence peaks” has been suggested, with one peak in adolescence before 20 years of age and the other in adulthood.9, 10 Nevertheless, the exact time of this early “incidence peak” is not very well documented. Thus, our goal was to accurately identify the age-specific incidence of psoriasis in childhood and trends in incidence between 1970 and 2000. We also compared disease characteristics at initial presentation in childhood onset and adult onset psoriasis.

METHODS

Study Setting

This population based retrospective study was carried out in Olmsted County, Minnesota, which has a population of 124,277 according to 2000 census. We used the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project,11 a medical records-linkage system containing complete inpatient and outpatient records from all healthcare providers in Olmsted County, including the Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Group, local nursing homes and the few private practitioners. All medical, surgical, and histological diagnoses and other key information from these healthcare providers are abstracted and entered into computerized indices to facilitate case identification. The Rochester Epidemiology Project allows ready access to the complete (inpatient and outpatient, labs) medical records for each subject from different healthcare providers, including both paper and electronic medical records. Therefore, this population-based data resource ensures virtually complete ascertainment and follow-up of all clinically diagnosed cases of psoriasis in a geographically-defined community with the unique ability to access original medical records for case validation.

Study population and data collection

Using the resources of Rochester Epidemiology Project, we identified all subjects who were residents of Olmsted County aged <18 years with diagnostic codes consistent with psoriasis (ICD9 696.1, 696.2, 696.8, 696.5, 696.3) between January 1, 1970 and December 31, 1999. Children with only psoriatic arthritis codes were not included. The complete medical records of all subjects were reviewed by a study nurse or dermatologist co-investigator and psoriasis was validated by either a confirmatory diagnosis in the medical record by a dermatologist, or a physician's description of the lesions in the medical record or a skin biopsy, whenever available. In case of a doubtful diagnosis, the medical record was reviewed by the dermatologist co-investigator (MMT). Incidence date was defined as the physician diagnosis date. Prevalent psoriasis subjects, subjects with missing medical records and those who denied research authorization were excluded.

Data were collected on demographics (date of birth, sex, race and ethnicity); duration of psoriasis symptoms (lesions) before the physician diagnosis; type of lesions (chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, pustular or sebo-psoriasis); site of lesions (palms and/or soles, elbows and/or knees, trunk, face, scalp, axilla, groin, inframammary, intergluteal/perianal or genital); and presence of nail involvement at the time of diagnosis. Dates and results of skin biopsies, when performed, were also reviewed. Where appropriate, findings in the pediatric population were compared with the findings in the adult psoriasis population identified in the same source population of Olmsted County during the same time period and using identical methodology7.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (percentage, means, etc.) were used to summarize the data. Disease characteristics of pediatric-onset and adult-onset patients were compared using chi-square and rank sum tests. Age and sex-specific incidence rates for psoriasis were calculated for individuals aged <18 years. Age- and sex-specific incidence rates were calculated by using the number of incident psoriasis cases as the numerator and population estimates based on decennial census counts as the denominator, with linear interpolation between census years, as described previously.12 Only children who were residents of Olmsted County at the onset of psoriasis and who fulfilled the study criteria were included in the incidence calculations. Overall incidence rates were age- and sex-adjusted to the 2000 white population of the United States. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the incidence rates were constructed using the assumption that the number of incident cases per year follows a Poisson distribution. Incidence trends were examined using Poisson regression models with smoothing splines for age and calendar year. The expected number of deaths was estimated using the cohort method and life tables from the Minnesota White population13.

Results

Characteristics of study population

We identified a total of 887 potential subjects <18 years of age with diagnostic codes consistent with psoriasis between January 1, 1970 and December 31, 1999. After screening the complete medical records from all healthcare providers, 357 psoriasis subjects fulfilled criteria for inclusion in the incidence cohort. Of the 530 excluded subjects, 456 had diagnoses other than psoriasis (e.g., pityriasis rosea, psoriasiform dermatitis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) and 74 were prevalent subjects (i.e. psoriasis prior to study time frame or moved to Olmsted County within the study time frame with pre-existing psoriasis).

The median age at diagnosis (25th and 7th percentile) of psoriasis was 11.0 (6.8, 14.4) years and 187 (52%) subjects were female (Table 1). The median age at incidence was relatively stable across the three decades at 10.4 years from 1970-1979, 12.0 at 1980-1989, and 10.5 at 1990-1999 (p= 0.35). The diagnosis of psoriasis was confirmed by a dermatologist in 290 (81%) subjects. The percentage of subjects confirmed by a dermatologist did not change significantly over time. The majority of subjects in the incidence cohort had chronic plaque psoriasis (263; 74%), followed by guttate psoriasis in 49 (14%) and sebo-psoriasis in 27 (8%) subjects. Psoriasis lesions most commonly involved the extremities including elbows and knees (214; 60%), the scalp 167 (47%), and the trunk 125 (35%). Approximately half (183; 51%) of patients had lesions at more than one anatomic site. Skin biopsy was performed in only 51 (14%) patients, 34 (67%) of which were confirmatory of the diagnosis of psoriasis. Nail involvement at incidence was present in 59 (17%) subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 357 (290 Dermatology Confirmed & 67 Not Confirmed) Incident Pediatric Psoriasis Subjects Between 1/1/1970 & 12/31/1999 in Olmsted County MN.

| Time period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 - 1979 (N=96) |

1980 - 1989 (N=102) |

1990 - 1999 (N=159) |

Total (N=357) |

|

| Age at incidence, median (IQR) | 10.4 (6.8, 14.3) |

11.1 (7.5, 14.9) |

10.3 (6.8, 13.6) |

10.6 (6.8, 14.4) |

| Male | 10.9 (7.1, 14.4) |

12.0 (5.4, 14.8) |

10.5 (6.5, 13.2) |

10.8 (6.5, 14.1) |

| Female | 10.2 (6.6, 14.2) |

12.2 (8.9, 14.9) |

10.5 (7.4, 14.4) |

11.0 (7.6, 14.6) |

| Female, no. (%) | 46 (48%) | 60 (59%) | 81 (50.9%) | 187 (52.4%) |

| Dermatologist Confirmation no. (%) | 78 (81%) | 88 (86%) | 124 (78%) | 290 (81%) |

| Skin Biopsy performed no. (%) | 25 (26%) | 14 (14%) | 12 (8%) | 51 (14%) |

| Psoriasis Type, no. (%) | ||||

| Chronic Plaque | 68 (71%) | 72 (71%) | 123 (77%) | 263 (74%) |

| Guttate | 16 (17%) | 16 (16%) | 17 (11%) | 49 (14%) |

| Sebo-Psoriasis | 4 (4%) | 10 (10%) | 13 (8%) | 27 (8%) |

| Pustular Psoriasis | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) |

| No Documentation | 5 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 6 (4%) | 14 (4%) |

| Location of Lesions, no. (%) | ||||

| Scalp | 41 (43%) | 48 (47%) | 78 (49%) | 167 (47%) |

| Elbows and/or knees, arms, legs | 59 (61%) | 67 (66%) | 88 (55%) | 214 (60%) |

| Palms and/or Soles | 5 (5%) | 6 (6%) | 7 (4%) | 18 (5%) |

| Trunk | 41 (43%) | 37 (36%) | 47 (30%) | 125 (35%) |

| Face | 16 (17%) | 17 (17%) | 30 (19%) | 63 (18%) |

| Axilla | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 9 (3%) |

| Inframammary | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Intergluteal, perianal | 5 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 11 (7%) | 20 (6%) |

| Genital | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 7 (4%) | 11 (3%) |

| Groin | 2 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 15 (9%) | 21 (6%) |

| Multiple Locations involved | 49 (51%) | 56 (55%) | 78 (49%) | 183 (51%) |

| Nail Involvement | 14 (15%) | 17 (17%) | 28 (18%) | 59 (17%) |

Table 2 shows a comparison of psoriasis disease characteristics at presentation in children and adults. The male to female gender ratio was 1.10 in pediatric-onset and 0.97 in adult-onset psoriasis (p= 0.29). The majority of subjects in both pediatric and adult-onset psoriasis had chronic plaque psoriasis (74% of children, 79% of adults), followed by guttate psoriasis, sebo-psoriasis, and pustular psoriasis. However, significantly more children than adults presented with guttate psoriasis (14% vs. 8%, p< 0.001), and significantly more adults than children presented with pustular psoriasis (3.% vs. 1.%, p+ 0.029). While psoriasis most commonly involved the extremities in children (60%), the most common location of involvement in adults was the scalp (42%). Lesions in the extremities (p< 0.001), trunk (p< 0.001), face (p< 0.001), and groin (p= 0.009) were significantly more common in children than adults. Genital (p= 0.009) and intergluteal (p= 0.005) involvement were more common in adults than children.

Table 2.

Comparison of Characteristics of Psoriasis in 357 Pediatric and 1,633 Adult-Onset Psoriasis Subjects.

| Criteria | Pediatric-Onset Psoriasis (N = 357) |

Adult-Onset Psoriasis* (N = 1,633) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female:male ratio | 1.10 | 0.97 | 0.29 |

| Psoriasis Type, No. (%) | |||

| Chronic plaque | 263 (73.7%) | 1292 (79%) | 0.024 |

| Guttate | 49 (13.7%) | 133 (8%) | <0.001 |

| Sebo-psoriasis | 27 (7.6%) | 87 (5.3%) | 0.10 |

| Pustular psoriasis | 4 (1.1%) | 53 (3.3%) | 0.029 |

| Location of Lesions, No. (%) | |||

| Scalp | 167 (46.8%) | 685 (42.0%) | 0.095 |

| Elbows, knees, arms, legs | 214 (59.9%) | 564 (35.0%) | <0.001 |

| Palms and/or soles | 18 (5%) | 118 (7.2%) | 0.14 |

| Trunk | 125 (35%) | 318 (19.0%) | <0.001 |

| Face | 63 (17.6%) | 176 (10.8%) | <0.001 |

| Axilla | 9 (2.5%) | 21 (1.3%) | 0.08 |

| Intergluteal, perianal | 20 (5.6%) | 170 (10.0%) | 0.005 |

| Genital | 11 (3.1%) | 110 (6.7%) | 0.009 |

| Groin | 21 (5.9%) | 50 (3.1%) | 0.009 |

| Multiple locations involved | 183 (51.3%) | 762 (46.7%) | 0.12 |

| Nail Involvement | 59 (16.5%) | 236 (14.0%) | 0.32 |

Data in this column comes from a previously published study7 on incidence of adult onset psoriasis.

Temporal trends in incidence of psoriasis

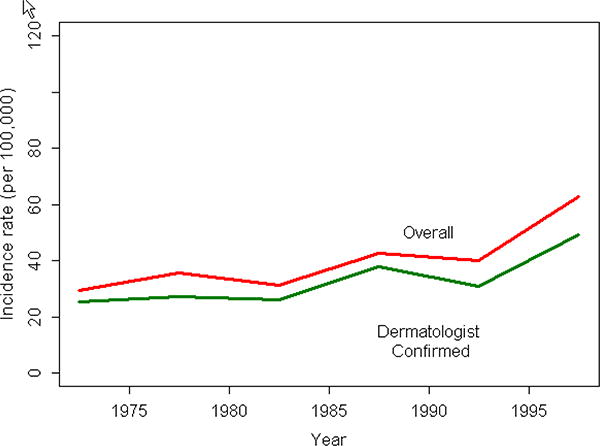

Table 3 shows the overall annual incidence of psoriasis in children over the 30-year time period from 1970 to 2000. The overall annual age and sex adjusted incidence of psoriasis between January 1, 1970 and December 31, 1999 was 40.8 (95% CI: 36.6, 45.1) per 100,000. Overall annual incidence gradually increased from 29.6 (95% CI: 209, 38.3) per 100,000 in 1970-1974 to 42.7 (95% CI: 31.8, 53.7) per 100,000 in 1985-1989 and 62.7 (95% CI: 50.4, 65.0) per 100,000 in 1995-1999 (p value for trend <0.001). When the incidence cohort was restricted to dermatologist confirmed subjects, the overall incidence was 33.2 per 100,000 (95% CI: 29.3, 37.0) and the increasing trend was similarly observed for dermatologist confirmed psoriasis subjects over the study period. Figure 1 illustrates the annual incidence of psoriasis in children. The incidence is steadily increasing during the entire time period and this temporal trend is very similar to the trends seen in adults during the same time period7.

Table 3.

Overall Annual Incidence of Psoriasis Over Time in Children <18 Years (per 100,000).

| Time Period | Incidence Rate (per 100,000)* and 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Dermatology Confirmed | Overall | |

| 1970-1974 | 25.6 (17.5, 33.6) | 29.6 (20.9, 38.3) |

| 1975-1979 | 27.4 (18.8, 36.0) | 35.7 (25.9, 45.5) |

| 1980-1984 | 26.2 (17.6, 34.8) | 31.4 (22.0, 40.8) |

| 1985-1989 | 37.7 (27.4, 48.0) | 42.7 (31.8, 53.7) |

| 1990-1994 | 30.8 (21.7, 39.9) | 40.0 (29.7, 50.3) |

| 1995-1999 | 49.4 (38.5, 60.3) | 62.7 (50.4, 65.0) |

| Total | 33.2 (29.3, 37.0) | 40.8 (36.6, 45.1) |

Age- and sex-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. white population.

Figure 1.

Trends in incidence of psoriasis between 1970 and 2000 (children <18 years).

Age and sex-specific incidence of psoriasis

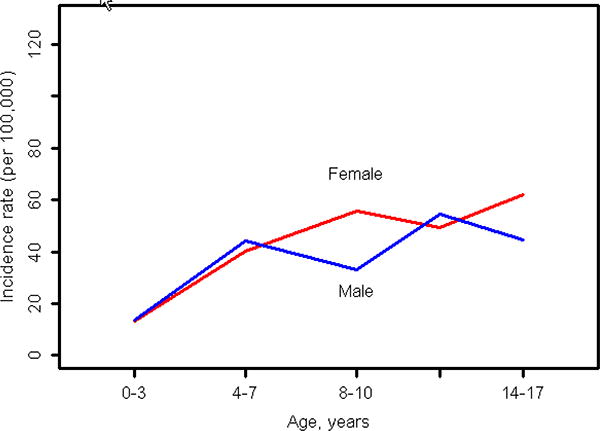

As shown in Table 4, the overall age-adjusted incidence of psoriasis in girls (43.9 per 100,000; 95% CI: 37.6, 50.3) was slightly higher than in boys (37.9 per 100,000; 95% CI: 32.1, 43.6; p= 0.09). Figure 2 illustrates the age-and sex-specific incidence of psoriasis in children and demonstrates a general increase in incidence as age increases in both boys and girls, with a more rapid increase up to age 7 in both genders. Incidence is relatively flat after age 7 in both genders.

Table 4.

Age- and Sex-Specific Annual Incidence of Psoriasis in Children <18 Years (per 100,000).

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No. | Rate | No. | Rate | No. | Rate | |

| 0-3 years | 14 | 13.7 | 13 | 13.2 | 27 | 13.5 |

| 4-7 years | 45 | 44.1 | 39 | 40.2 | 84 | 42.2 |

| 8-10 years | 27 | 33.2 | 42 | 55.7 | 69 | 44.0 |

| 11-13 years | 40 | 54.6 | 35 | 49.6 | 75 | 52.2 |

| 14-17 years | 44 | 44.7 | 58 | 61.9 | 102 | 53.1 |

| Total (95% CI) | 170 | 37.9* (32.2, 43.6) |

187 | 43.9* (37.6, 50.2) |

357 | 40.8† (36.6, 45.0) |

Age-adjusted to the 200 U.S. white population.

Age- and sex-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. white population.

Figure 2.

Incidence of pediatric onset psoriasis by age groups for males and females (children <18 years).

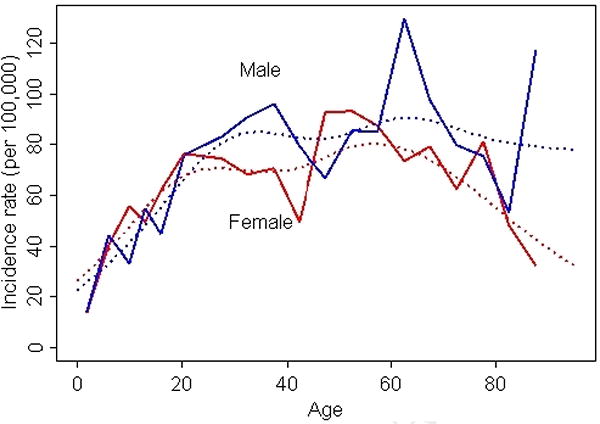

Figure 3 illustrates the age- and sex-specific incidence of psoriasis in all age groups, starting from birth. Previously published data7 from adult incident subjects have been used to generate this figure. Overall incidence rapidly increases in childhood and young adulthood in both males and females, after which the rate of increase in incidence is much slower. Although the smoothed splines suggest 2 small peaks in the 30's and 60's, this was not significant.

Figure 3.

Age-specific incidence of psoriasis (1/1/1970-12/31/1999, Olmsted County, MN). Bold lines represent the overall (crude) incidence curves and dotted lines represent incidence curves derived using smoothing splines.

Over an average of 14.4 years of follow-up of this pediatric psoriasis cohort, only 2 subjects were deceased. The expected number of deaths was 3.4, corresponding to a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) 0.59 (95% CI: 0.07, 2.12). Therefore, it was not feasible to evaluate excess mortality and causes of mortality in this relatively young cohort.

Discussion

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory condition of the skin that affects an estimated 2% of the overall United States population in their lifetime.3 Prevalence estimates vary slightly, depending on the ethnicity of the population studied. Psoriasis is also one of the most common inflammatory disorders of the skin in children, with one Turkish study estimating the prevalence in children as high as 3.8%.14 Despite being so common, to our knowledge, no epidemiologic studies exist regarding the incidence of psoriasis in children. The current study is the first to describe the incidence of psoriasis in the pediatric population.

In this study we found the overall age and sex adjusted annual incidence of pediatric psoriasis to be 40.8 per 100,000. This is considerably lower than the adult incidence recently reported by our group (78.9 per 100, 000)7 as well as other recent adult studies that have estimated the incidence of psoriasis at 140 per 100, 0006 and 108 per 100, 000.5 Two of the previous incidence studies have included small numbers of pediatric patients in their analysis. A recent study by Huerta and colleagues performed in the United Kingdom, estimated the incidence in the pediatric population of approximately 116 per 100, 000.6 This is nearly three times higher than that found in our study, and this may be due to several factors. First, no record review was performed to validate the diagnostic codes. Second, there was no mechanism in place to exclude prevalent cases, thus likely overestimating the incidence of pediatric psoriasis. Furthermore, similar to our study, they did not require confirmation of the diagnosis of psoriasis by a dermatologist. While approximately 80% of our patients did have specialty confirmation, most of the patients in the Huerta study likely did not, as most psoriasis cases in the United Kingdom are not referred to a dermatologist.15, 16 This is likely reflected in their very high incidence rates in the overall adult and pediatric population as compared to our recently published adult study (140 vs. 78.9 per 100, 000)6, 7. In addition, they have not reported how many pediatric patients were included in their study and likely the number of children was a small percentage of the overall study population. It is also possible that the genetic make-up and/or risk factor distribution in the United Kingdom may be different than the population in Olmsted County, Minnesota. The other large incidence study that included pediatric patients was that of Bell and colleagues who studied the incidence of psoriasis in Rochester, Minnesota, which makes up most of the population of Olmsted County. In the Bell study, the incidence of psoriasis among patients less than 20 years of age was 30.9 per 100, 000 (21 patients total). The study years were 1980 to 1983, and this number is very similar to the incidence of 31.4 per 100, 000 found in our study from 1980 to 1984 (Table 3).

Several prevalence studies have demonstrated that approximately one-third of psoriatic patients develop their symptoms sometime during childhood, although some of these may not be diagnosed until adulthood.8, 17 Furthermore, others have hypothesized a “dual peak” in the incidence of psoriasis, with one occurring during childhood or adolescence and the other in adulthood. Henseler and colleagues found a first peak of psoriasis onset to occur at 16 years of age in girls and at 22 years of age in males, with the second peak around 60 years of age in both men and women.9 Smith and colleagues found similar results with modes for onset of psoriasis at 21 and 62 years for males and 17 and 57 years for females.10 Several older studies had shown similar results.18, 19 None of these studies, however, were incidence studies. Our study does not support a “dual peak” in age of onset and instead, demonstrates that the incidence of psoriasis actually increases steadily with age until approximately the 7th decade of life, with a more rapid increase in the rate of incidence until age 30-35 (Figure 3). In children there seems to be a more rapid increase in the rate of incidence in both genders until age 7, after which it levels off a bit in both boys and girls (Figure 2). No dual peak was identified. Thus, clinicians must maintain a clinical suspicion for the diagnosis of psoriasis at all ages as there does not appear to be a true “peak” or “peaks” in psoriasis incidence.

There was a significant increase in incidence of psoriasis in the pediatric population with time with incidence per 100,000 increasing steadily from 29.6 in 1970 to 1974 to 62.7 in 1995-1999 (p<0.001). This temporal trend is similar to the trends seen in the adult population7. This is an interesting and intriguing finding which may have several potential explanations. It is possible that improved access to medical care has led to increased diagnosis over time, but that seems unlikely as the population of Olmsted County has had excellent access to general and specialized medical care for over a century, as evidenced by the fact that 81% of our patients had their diagnoses confirmed by a dermatologist. It also seems unlikely that increased recognition of the disease has led to the increased incidence over time as the clinical features of psoriasis have been recognized for hundreds of years, and criterion for diagnosis have not changed significantly over time.

Pediatric psoriasis has been linked to several risk factors, including medications such as antimalarials,20 stress,14, 21 infections such as streptococcus,14, 22 and obesity.23, 24 Prescribing habits in the pediatric population for medications such as antimalarials likely have not changed significantly enough to be contributing to the increase in incidence over time. It is possible that the amount of psychosocial stress experienced by children has increased as societal norms and pressures have changed over the last several decades, however that is quite difficult to quantify. Although it has not been objectively studied, it may be that infection rates in children have increased since 1970, particularly now that more and more children are in daycare and exposed to multiple bacterial and viral agents on a daily basis. This may be contributing somewhat to the increase in incidence noted over our study period. Furthermore, the obesity epidemic has recently been recognized as a difficult challenge facing our population. Not only is adult obesity increasing at a rapid rate, but so is obesity in childhood along with all of its associated health problems.25, 26 Obesity and being overweight has recently been described as a risk factor for psoriasis in the adult population and it is likely that it plays a significant role in children as well.23, 24, 27, 28 Thus, this may be an additional explanation for the increasing pediatric psoriasis incidence seen from 1970 to 2000. Further research in children is needed to better characterize this possible association.

Earlier prevalence studies of pediatric psoriasis have reported a female predominance in childhood that has approached a ratio of 2:1.29, 30 Our current study, however, found that boys and girls were fairly equally affected during childhood. While there was a slight predominance of female patients (52%), this was not statistically significant. Our findings are similar to those found in several recent epidemiologic studies of pediatric psoriasis from the United States, China, Australia, and India.8, 31-34 The difference between findings from the older and newer studies may be explained by differences in study design and easier access to healthcare in more recent years.

We found the median age at incidence to be 10.6 years. There was no significant difference in age at diagnosis between the two genders, and there was no difference per time period studied. This is similar to two recent studies demonstrating the mean age at presentation for pediatric psoriasis to be 9.96 years and 11 years.14, 31

Most of the children were found to have chronic plaque psoriasis (74%), followed by guttate psoriasis (14%), seb-psoriasis (8%), and least commonly pustular psoriasis (1%). This is in concordance with multiple other studies in children that have found rates of plaque psoriasis in children to be 60.6 to 69.6%.31, 32, 34 One recent Australian study found chronic plaque psoriasis to be the most common type but with a proportion much lower at 34.1%.33 This study, however, broke down the types of psoriasis into 16 different categories, several of which may overlap with the category of chronic plaque psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis is often the next most common type of childhood psoriasis with proportions ranging from 9.7 to 28.9%, and is often linked to an infectious trigger, particularly streptococcal infection.31, 32, 34

The most predominant types of psoriasis seen in children were actually quite similar to that what was seen in our recent adult study7. However, there were also several notable distinctions. While chronic plaque psoriasis was the most predominant type in both adults and children, we found that guttate psoriasis was significantly more common in children than adults and pustular psoriasis was significantly more common in adults than in children (Table 2).

In our study most children had involvement of their psoriasis most frequently on the extremities (60%), closely followed by involvement on the scalp (47%). This is in contrast to the adult population where scalp involvement was the most common (42%) followed by the extremities (35%). Furthermore, pediatric patients had significantly more involvement of the trunk, face, and groin than did adult patients, thus indicating that practitioners must keep a high level of suspicion for psoriasis when encountering rashes in these locations in children. Most of the studies done in the past in pediatric patients found that the scalp and extremities were the two most common sites involved, with some reporting extremity more common than scalp disease,14, 31, 32 and others finding scalp more common than extremity involvement.8, 34

Recent studies in adults have determined psoriasis to be an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular disease and possibly for the metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus.1, 35-38 This association has not been found in children, and in fact, psoriasis has not been determined to be an independent risk factor for any chronic disease in childhood. One study reported that eighteen of the 419 psoriatic children they studied had other systemic disorders, but these were all interpreted to be due to chance, and not due to psoriasis.32 We haven't examined comorbidities in our cohort of children with psoriasis. Further prospective studies would be useful in determining the risk of long-term comorbidities in patients with pediatric-onset psoriasis.

In contrast to some previous reports of increased mortality in patients with severe psoriasis,39, 40 we did not observe a significantly increased risk of mortality in our adult-onset psoriasis cohort7. Only two of the patients in our pediatric psoriasis cohort were deceased, and therefore, we were unable to perform a formal survival analysis. Therefore, we are unable to comment on mortality in pediatric-onset psoriasis.

There were several potential limitations to our current study. First, the population of Olmsted County is a relatively homogeneous population consisting of approximately 90% Caucasians, thus limiting the ability to generalize our data to more ethnically diverse populations. However, the strength of the Rochester Epidemiology Project is the availability of complete medical records for decades and ability to examine trends using consistent eligibility criteria. It is possible that incidence rates reported in this manuscript may be an underestimate due to underreporting of the psoriasis as well as disease that may not be brought to medical attention. Children with psoriatic arthritis were not included, although the incidence of arthritis is children is expected to be extremely low. Furthermore, incidence dates may not be entirely accurate due to the delay between the onset of symptoms and seeking medical care. However, both of these potential limitations are unlikely because parents are more likely to bring their children in for evaluation of a skin disease than they are to bring themselves in, thus reducing the amount of underreporting. They are also more likely to bring their children early and the structure of the medical system in Olmsted County is that of readily-accessible medical care, therefore limiting the time a patient must wait before receiving medical care. Since the primary focus of this study was incidence trends, we did not assess the potential role of obesity as a risk factor for psoriasis in children.

In conclusion, this is the first population-based incidence study reporting on the incidence of psoriasis in children. We were unable to define a “dual-peak” in the incidence of pediatric psoriasis, but instead found that incidence rates increased steadily with age from birth to the 7th decade of life. We also observed an increase in incidence in both boys and girls throughout the study period from 1970 to 2000. The reasons for this are largely unknown but may involve a variety of factors including changes in diagnostic patterns and/or increasing prevalence of risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Further research is necessary to more clearly delineate these risk factors. Pediatric practitioners, in the meantime, must maintain a level of suspicion for the diagnosis of psoriasis in all age groups.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Mitch Bais for his assistance in obtaining medical records and Dianne Carlson for her assistance in data collection.

Funding: Funded by an unrestricted research grant from Amgen Inc. and NIAMS AR30582

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;156(2):271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, Neimann AL, Berlin JA, Margolis DJ. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005 Dec;141(12):1537–1541. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, Margolis DJ, Rolstad T. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004 Mar;9(2):136–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell LM, Sedlack R, Beard CM, Perry HO, Michet CJ, Kurland LT. Incidence of psoriasis in Rochester, Minn, 1980-1983. Arch Dermatol. 1991 Aug;127(8):1184–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shbeeb M, Uramoto KM, Gibson LE, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA, 1982-1991. J Rheumatol. 2000 May;27(5):1247–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huerta C, Rivero E, Rodriguez LA. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Arch Dermatol. 2007 Dec;143(12):1559–1565. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Dann FJ, Gabriel SE, Maradit Kremers H. Trends in incidence of adult-onset psoriasis over three decades: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Mar;60(3):394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raychaudhuri SP, Gross J. A comparative study of pediatric onset psoriasis with adult onset psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 May-Jun;17(3):174–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henseler T, Christophers E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: characterization of two types of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Sep;13(3):450–456. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AE, Kassab JY, Rowland Payne CM, Beer WE. Bimodality in age of onset of psoriasis, in both patients and their relatives. Dermatology. 1993;186(3):181–186. doi: 10.1159/000247341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996 Mar;71(3):266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder D, O K. A SAS macro which utilizes local and reference population counts appropriate for incidence, prevalence, and mortality rate calculations in Rochester and Olmsted County, Minnesota. Technical Report Series Rochester, MN: Section of Medical Research Statistics, Mayo Clinic. 1982 (Report No: 20) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therneau TM. Technical Report Series No. 63. Expected survival based on hazard rates (updated) Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic, Department of Health Sciences Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seyhan M, Coskun BK, Saglam H, Ozcan H, Karincaoglu Y. Psoriasis in childhood and adolescence: evaluation of demographic and clinical features. Pediatr Int. 2006 Dec;48(6):525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basarab T, Munn SE, Jones RR. Diagnostic accuracy and appropriateness of general practitioner referrals to a dermatology out-patient clinic. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Jul;135(1):70–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillard SE, Finlay AY. Current management of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: patterns of prescribing and resource use in primary care. Int J Clin Pract. 2005 Nov;59(11):1260–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farber EM, Nall ML. The natural history of psoriasis in 5,600 patients. Dermatologica. 1974;148(1):1–18. doi: 10.1159/000251595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burch PR, Rowell NR. Psoriasis: aetiological aspects. Acta Derm Venereol. 1965;45(5):366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunawardena DA, Gunawardena KA, Vasanthanathan NS, Gunawardena JA. Psoriasis in Sri-Lanka--a computer analysis of 1366 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1978 Jan;98(1):85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb07337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsankov N, Angelova I, Kazandjieva J. Drug-induced psoriasis. Recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000 May-Jun;1(3):159–165. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Picardi A, Mazzotti E, Gaetano P, et al. Stress, social support, emotional regulation, and exacerbation of diffuse plaque psoriasis. Psychosomatics. 2005 Nov-Dec;46(6):556–564. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassandra M, Conte E, Cortez B. Childhood pustular psoriasis elicited by the streptococcal antigen: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003 Nov-Dec;20(6):506–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2003.20611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005 Dec;141(12):1527–1534. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin Y, Zhang F, Yang S, et al. Combined effects of HLA-Cw6, body mass index and waist-hip ratio on psoriasis vulgaris in Chinese Han population. J Dermatol Sci. 2008 Nov;52(2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benson L, Baer HJ, Kaelber DC. Trends in the diagnosis of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: 1999-2007. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(1):e153–158. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998 Jan;22(1):39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altobelli E, Petrocelli R, Maccarone M, et al. Risk factors of hypertension, diabetes and obesity in Italian psoriasis patients: a survey on socio-demographic characteristics, smoking habits and alcohol consumption. Eur J Dermatol. 2009 Feb 12; doi: 10.1684/ejd.2009.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray ML, Bergstresser PR, Adams-Huet B, Cohen JB. Relationship of psoriasis severity to obesity using same-gender siblings as controls for obesity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009 Mar;34(2):140–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farber EM, Carlsen RA. Psoriasis in childhood. Calif Med. 1966 Dec;105(6):415–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyfors A, Lemholt K. Psoriasis in children. A short review and a survey of 245 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1975 Apr;92(4):437–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb03105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan X, Xiao FL, Yang S, et al. Childhood psoriasis: a study of 277 patients from China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007 Jul;21(6):762–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar B, Jain R, Sandhu K, Kaur I, Handa S. Epidemiology of childhood psoriasis: a study of 419 patients from northern India. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Sep;43(9):654–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris A, Rogers M, Fischer G, Williams K. Childhood psoriasis: a clinical review of 1262 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001 May-Jun;18(3):188–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018003188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nanda A, Kaur S, Kaur I, Kumar B. Childhood psoriasis: an epidemiologic survey of 112 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1990 Mar;7(1):19–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1990.tb01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Sep;159(4):895–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Meier CR. Psoriasis and the risk of incident diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Dec;159(6):1331–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. Jama. 2006 Oct 11;296(14):1735–1741. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Nov;55(5):829–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007 Dec;143(12):1493–1499. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearce DJ, Lucas J, Wood B, Chen J, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. Death from psoriasis: representative US data. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(5):302–303. doi: 10.1080/09546630600825067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]