1. Introduction

Tobacco smoke condensate (TSC) has been demonstrated to be tumorigenic in several animal species [1–7]. Tobacco smoke contains a variety of compounds of which at least 40 compounds have carcinogenic potential [8–10]. Polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) represent major constituents of tobacco smoke and the tumorigenic potential of PAHs is well documented [9–12]. PAHs by itself are not carcinogenic, but require metabolic activation to exert their carcinogenic effects. For example benzo(a)pyrene (BP), a prototype PAH, present in TSC is metabolically activated by the cytochrome P-450-dependent monooxygenase system preferentially to anti-BP-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide (BPDE), a reactive electrophile which binds to cellular DNA predominantly at the N2 position of deoxyguanosine (dG) and which is implicated as the ultimate carcinogenic metabolite of BP [13]. The carcinogenicity of TSC in mouse skin and the known content of PAHs in TSC suggest that the PAHs present in the cigarette smoke do not fully account for the observed TSC carcinogenicity [5, 14, 15]. Therefore, it was speculated that either other carcinogens or tumor-promoting substances, or both, are present in the TSC. Later it was demonstrated that the weakly acidic fraction of TSC called the phenolic fraction possesses strong tumor-promoting activity comparable to that of whole TSC [16, 17]. In animal studies it is observed that the weakly acidic phenolic components of tobacco smoke potentiates tobacco smoke neutral components (PAHs) induced tumorigenicity [16, 17]. Tobacco smoke contains more than 200 semi-volatile phenolic compounds [18]. The major phenolic components in tobacco smoke are phenols; alkyl substituated phenols e.g. cresols, ethyl/dimethyl/trimethyl phenols; di- and trihydroxybenzenes e.g. catechol, resorcinol, hydroquinone, etc. [18].The underlying mechanism of tumor promotion by TSC phenolic fraction is unknown. The possible mechanism(s) of tumor promotion by this fraction may include any of the known biological effects of established tumor promoters.

In context of tumor promotion, it is observed that AP-1 transcription factor has a role in TPA-induced cell transformation in JB6 (P+) cells (48, 49). It is also observed that NF-κB activity is required for the maintenance of transformed phenotypes in JB6 cells (51, 52). Modulation of transcription factors AP-1/NF-κB and activation of PKC by established tumor promoter TPA and others has been well documented in different cell lines including JB6 cells [19–28]. Although they are differentially modulated depending on cell types and other criteria [19–34] down-regulation of PKC has been implicated to have a role in tumor promotion [27, 28, 36]. It is observed that activation of PKC or increased intracellular PKC substrate phosphorylation is inversely related to tumor promotion in JB6 (P+) cells (35, 50). In this study to gain an insight into the molecular mechanism by which weakly acidic phenolic fraction potentiates PAH-induced carcinogenicity, we examined its effect on activation of AP-1, NF-κB and PKC in BPDE treated cells. Our results show that down-regulation of PKC by TSC phenolic fraction may have a role in potentiation of BPDE-induced carcinogenicity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and reagents

Promotion sensitive mouse epidermal JB6 Cl 41 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, USA). Cl 41 cells stably transfected with firefly luciferase reporter gene driven by minimal NF-κB or AP-1-responsive region were the gift from Dr. Nancy Colburn, National Cancer Institute-Frederick Cancer Research Facility, Frederick, MD. (+/−)-anti-BPDE was purchased from the NCI Chemical Carcinogen Reference Standard Repository. Tobacco smoke condensate was obtained from Arista Laboratories( (Richmond, VA); phospho-(Ser) PKC Substrate antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (MA); PKC inhibitors staurosporine, bisindolylmaleimide, Go6976 and rottlerin from EMD Chemicals, Inc. ( Gibbstown, NJ); modified Eagle’s Medium (MEM) and fetal calf serum (FCS) from Invitrogen Life Technologies (CA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Cell culture

JB6 Cl 41 cells were cultured in a humid atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2 using modified Eagle’s medium (MEM) containing 5% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM sodium pyruvate and penicillin/streptomycin (50µg/ml each). Cells were checked on a routine basis for Mycoplasma contamination by the Gibco Mycotect.

2.3. Preparation of Phenolic Fraction from Tobacco Smoke Condensate (TSC)

The whole tobacco smoke condensate was obtained from Arista Laboratories, Richmond, VA. The weakly acidic phenolic fraction of TSC was prepared following the procedure as described elsewhere [16] and is depicted in chart 1. TSC from 1000 cigarettes (15 g TSC) was dissolved in a mixture of 2N HCl and peroxide-free ether (1:3 v/v). The aqueous acidic layer was separated and the ether layer was then washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate to remove carboxylic acids, and with portions of 3% KOH to remove any carboxylic acid remaining together with the phenols present. The phenols were recovered from the KOH washing, neutralized with 2N HCl, excess sodium bicarbonate added, and the mixture was saturated with NaCl and extracted with portions of ether. The combined ether washings containing phenols were dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and the solvent is removed by heating in a water bath. Phenols obtained (yield 1.4 g) were stored in aliquots in small sealed dark ampoules at −25°C and is called the phenolic fraction of TSC. In order to avoid any significant changes of the phenolic samples due to storage, the stored samples of TSC phenolic fraction from each preparation was used within 3 to 4 weeks and each small ampoule once opened was used for one time.

Chart 1.

Preparation of weakly acidic phenolic fraction from tobacco smoke condensate

2.4. Determination of anchorage-independent cell growth

Anchorage-independent growth of promotion-sensitive JB6 Cl41 cells on soft agar was determined by following the procedure as described by others [37]. Briefly, 60mm culture dishes were first plated with 7 ml of 0.5% agar EMEM containing 10% calf serum (heat inactivated) and allowed to solidify. Exponentially growing JB6 cl41 cells after trypsinization (10,000 cells) were either treated with BPDE (0.5µM) alone or with BPDE (0.5µM) first for 1 hour followed by treatment with noncytotoxic concentration of TSCPhFr (10 and 30 µg/ml) in 1.5 ml 0.33% agar EMEM (10% serum). After treatment cells in the top agar were then poured onto the prehardened base medium containing 0.5% agar. The dishes were incubated at 37°C (5% CO2). After 14 days the number of colonies (containing at least 8 cells) in each dish was counted.

2.5. NF-κB and AP-1 activation assay

The activation of the transcription factors NF-κB or AP-1 was determined in appropriately treated JB6 (Cl 41) cells harboring either NF-κB or AP-1-luciferase reporter plasmids. After selection in presence of 400 µg/ml G418 cells in mid-log growth, cells were treated with BPDE dissolved in DMSO (0.05–0.1% of the culture volume) for 1 hour in serum-free medium and further incubated in medium containing 5% serum for 16 hours (unless mentioned otherwise) in the absence of BPDE. To examine the effect of TSC phenolic fraction, cells were first treated with BPDE for 1 hour in serum free medium and then with TSC phenolic fraction in 5% serum-containing MEM. Cells were harvested 16 hours after BPDE treatment. Luciferase activity in respective cell extract was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using Luciferase Assay kit (Promega, CA). Briefly, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (supplied in the kit), freeze-thawed and then centrifuged briefly at 14,000 rpm. Twenty µl of the supernatant was mixed with 100 µl of the luciferase assay reagent, and the light intensity was measured by a Luminometer with a 2 seconds measurement delay and 10 seconds measurement read. NF-κB/AP-1 activity in the respective cell extract was expressed as light units (LU) per mg protein.

2.6. Determination of intracellular PKC substrate phosphorylation

We performed Western immunoblotting of the cell extract (lysed in SDS sample buffer 6 hours after BPDE treatment) to determine PKC substrate phosphorylation as a measure of intracellular PKC activation using Phospho-(Ser) PKC Substrate Antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Phospho-(Ser) PKC Substrate Antibody detects endogenous levels of cellular proteins only when phosphorylated at serine residues in particular motif found in PKC substrates (surrounded by Arg or Lys at the −2 and +2 positions and a hydrophobic residue at the +1 position). The antibody does not cross-react with non-phosphorylated serine residues, with phospho-threonine in the same motif, or with phospho-serine in other motifs (Cell Signaling Technology data sheet).

3. Results

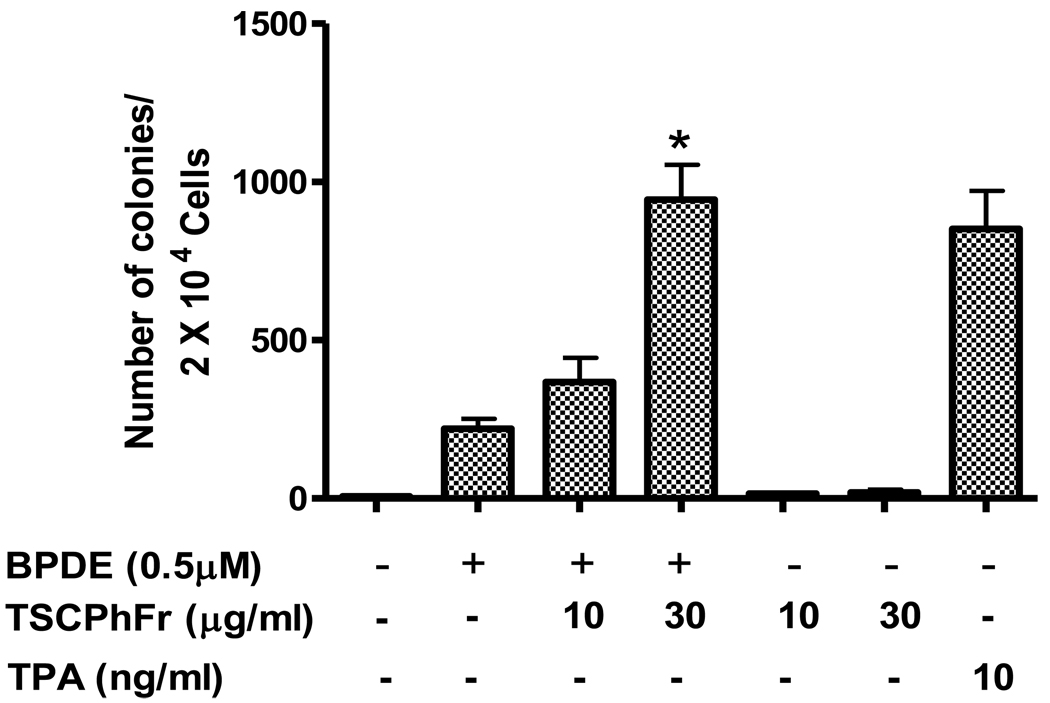

3.1. TSC phenolic fraction potentiates anchorage-independent growth of BPDE-treated Cl 41 cells

To examine the tumor promoting activity of TSC phenolic fraction we investigated whether TSC phenolic fraction can potentiate BPDE induced anchorage-independent growth of promotion sensitive JB6 cells (Cl 41). TSC phenolic fraction was prepared from tobacco smoke condensate as described before (Chart 1). Figure 1 indicates that BPDE by itself has some ability to cause anchorage-independent cell growth of JB6 cells on soft agar compared to untreated cells. Interestingly, we observed that TSC phenolic fraction at noncytotoxic concentration significantly potentiates BPDE-induced anchorage-independent cell growth in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment of cells with 30 µg/ml TSC phenolic fraction caused almost 4.3 fold potentiation of BPDE-induced anchorage-independent growth on soft agar. Regarding cytotoxicity of TSC phenolic fraction we observed that treatment of Cl 41 cells with 60 µg/ml concentration of TSC phenolic fraction is well below the cytotoxic level (more than 95% cell survival) as determined by Trypan blue exclusion assay (data not shown). TSC phenolic fraction by itself has no effect on anchorage-independent cell growth activity. This finding in in vitro cell culture model supports the previous observation of tumor promoting activity of TSC phenolic fraction in mouse skin [16, 17].

Figure 1.

Effect of TSC phenolic fraction on anchorage-independent growth of BPDE treated JB6 Cl41 cells. Experimental procedure is described in the text. Each bar shows the average of three independent experiments and the error bars indicate SD. (*) indicates statistical analysis of significance with paired t-Test (p<0.05).

3.2. TSC phenolic fraction inhibits BPDE-induced NF-κB activation but not AP-1 activation

The transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB are known to be influenced by established tumor promoter TPA [19–26]. Although AP-1 and NF-κB have roles in cell transformation, NF-κB activation status in JB6 cells was observed to have a threshold value beyond which cell death instead of increased cell transformation is observed [38]. We examined whether potentiation of BPDE-induced cell transformation by TSC phenolic fraction is associated with the modulation of activities of these two transcription factors. We used Cl 41 cells harboring AP-1-responsive and NF-κB- responsive luciferase gene to monitor the activation of AP-1 and NF-κB respectively. BPDE treatment of cells showed induction of both AP-1 and NF-κB activity (figure 2A and 2B) in a dose-dependent manner. 0.5 µM BPDE treatment caused 8.2 fold and 48 fold induction of AP-1 and NF-κB activity respectively compared to untreated cells. Interestingly, treatment of cells with TSC phenolic fraction did not have any effect on BPDE-induced AP-1 activation (figure 2A), whereas BPDE-induced NF-κB activation was found to be significantly inhibited by TSC phenolic fraction in a dose-dependent manner (figure B, 44% and 83% inhibition by 10 µg/ml and 30 µg/ml TSC phenolic fraction respectively). TSC phenolic fraction by itself has no effect on either AP-1 or NF-κB activation. To our knowledge this is the first report that TSC phenolic fraction inhibits NF-κB activation in chemical carcinogen-damaged cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of TSC phenolic fraction on activation of AP-1 and NF-κB in JB6 (P+) Cl 41 cells harboring AP1-luciferase and NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmids. Activation of AP-1 (A) and NF-κB (B) is measured as described in “Methods”. Cells were either untreated; treated with TSC phenolic fraction (10 µg/ml); with BPDE (0.2 µM, 0.5 µM); with 0.5 µM BPDE followed by TSC phenolic fraction (10 µg/ml or 30 µg/ml). Each bar indicates the mean ± SD of three parallel experiments. (*) indicates statistical analysis of significance with paired t-Test (p<0.05).

3.3. TSC phenolic fraction inhibits intracellular PKC substrate phosphorylation and PKC inhibition attenuates BPDE-induced NF-κB activation

Increased hyperplasia associated with down-regulation of PKC activity in mouse skin has been observed with established tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and it has been suggested that down-regulation of PKC may be a permissive event for epidermal hyperplasia and tumor promotion [27, 28]. Although the role of PKC in tumor promotion is not straightforward without complication there are suggestions that its down-regulation may be important in tumor promotion [35, 36]. PKC is also known to have a role in the activation of NF-κB (39–41). In this study we examined whether TSC phenolic fraction as a tumor promoter has ability to interfere with intracellular PKC activation. PKC activation is monitored by determining intracellular PKC substrate phosphorylation as described in “Methods”. Figure 3 demonstrates that in Cl41 cells there is high basal level of PKC substrate phosphorylation. Cells treated with either BPDE or TSC phenolic fraction did not show any significant change of PKC substrate phosphorylation. Interestingly, cells treated with 30 µg/ml TSC phenolic fraction significantly reduced PKC substrate phosphorylation in BPDE treated cells. These findings indicate that attenuation of BPDE-induced NF-κB activation by TSC phenolic fraction is associated with PKC down-regulation.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of PKC substrate phosphorylation by TSC phenolic fraction. Cells were either untreated or treated with 0.5 µM BPDE for 1 hr. followed by noncytotoxic concentration of TSC phenolic fraction for 6 hours and PKC substrate phosphorylation in the cell extract was determined by Western immunoblotting using phospho-(Ser) PKC Substrate antibody which is specific for PKC substrates phosphorylated at Ser residues within a particular motif.

Inhibition of PKC substrate phosphorylation by TSCPhFr is not due to its ability to activate intracellular phosphatase and sequester intracellular PKC substrates. Previously we observed that PKC activation by phorbol ester TPA (10 ng/ml) as measured by PKC substrate phoshorylation is not affected at all by TSCPhFr (unpublished data). If TSCPhFr has abilility to activate phosphatase and sequester intracellular PKC substrates then it is expected that TSCPhFr would also inhibit phorbol ester-induced PKC substrate phosphorylation, but it does not.

Next we examined whether PKC inhibition has any role in the attenuation of NF-κB activation by TSC phenolic fraction. It is observed that BPDE-induced NF-κB activation is differentially attenuated by different inhibitors of PKC (figure 4). The extent of NF-κB attenuation is least (27%) with conventional PKC inhibitor Go6976 (highly specific for PKC alpha, beta I, beta II and gamma isoforms) and moderate with non-specific PKC inhibitors staurosporine (39%) and bisindolylmaleimide (47%), whereas highest attenuation of NF-κB activation (62%) is observed with Rottlerin known to be highly specific for PKC δ. This suggests that PKC inhibition can cause attenuation of DNA damage-induced NF-κB activation. Thus our observation of the attenuation of NF-κB activation associated with inhibition of intracellular PKC activity by TSC phenolic fraction in BPDE treated cells indicates a possible link between the two.

Figure 4.

Effect of PKC inhibitors on BPDE-induced NF-κB activation in JB6 Cl 41 cells harboring NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid. Bar graph shows NF-κB activation in cells that were untreated (A); treated with 0.5 µM BPDE (B); treated with 0.5 µM BPDE plus respective PKC inhibitors staurosporine, 7 nM (C); bisindolylmaleimide, 100 nM (D); Go6976, 0.5 µM (E) and rottlerin, 30 µM (F). Each bar indicates the mean ± SD of three parallel experiments. (*) indicates statistical analysis of significance with paired t-Test (p<0.05).

3.4. PKC inhibition potentiates BPDE-induced anchorage-independent cell growth on soft agar

Since PKC down-regulation is implicated in tumor promotion [27, 28, 36] we further examined whether inhibition of PKC activity by TSC phenolic fraction has any correlation with its ability to potentiate the anchorage-independent growth of BPDE treated Cl41 cells on soft agar. It is evident from figure 5 that not only the carcinogen BPDE but also the PKC inhibitors Go6976 and rottlerin have varying ability to initiate anchorage-independent growth of Cl41 cells. The number of colonies on soft agar increased 21.9 fold, 11.4 fold and 31.5 fold with BPDE, Go6976 and rottlerin respectively. But we observed potentiation of anchorage-independent growth of BPDE treated cells by PKC inhibitors (with respect to the sum of the individual effect). Cells treated with Go6976 and rottlerin showed 1.8 fold and 3.1 fold potentiation of BPDE-induced cell growth respectively.

Figure 5.

Effect of PKC inhibitors on anchorage-independent growth of JB6 cl41 cells. Experimental procedure is described in the text. Each bar shows the average of three independent experiments and the error bar indicates SD.

4. Discussion

Our present study demonstrates that phenolic fraction (weakly acidic components) of TSC potentiates BPDE-induced anchorage-independent cell growth (an in vitro measure of cell transformation). This potentiating effect is associated with attenuation of NF-kB activation and PKC down-regulation. It is also evident from our findings that PKC inhibition can attenuate BPDE-induced NF-kB activation and potentiate anchorage-independent cell growth on soft agar. Although the role of PKC in tumor promotion is not straightforward without complication there are suggestions that its “down-regulation” may be important in tumor promotion [27, 28, 35, 36, 50]. The data presented in our study indicate that down-regulation of PKC may have a role in potentiation of BPDE-induced tumorigenicity by TSC phenolic fraction.

Based on our present findings it is not clear whether attenuation of NF-kB activity is an associated phenomenon or has direct correspondence with potentiation of BPDE-induced anchorage-independent cell growth. We observed that treatment of cells with different concentrations of B6-Amino-4-(4-phenoxyphenyl ethylamino) quinazoline (APQ) (Calbiochem), an inhibitor highly specific to NF-kB, either inhibits or potentiates BPDE-induced anchorage-independent cell growth (data not shown). In this regard we address some relevant issues pertaining to our findings and inference. First, if attenuation of NF-kB by TSC phenolic fraction (as we observed) has any correspondence with potentiation of anchorage-independent cell growth, then the role of NF-kB activation by BPDE in BPDE-induced cell transformation is questionable. Second, if PKC down-regulation attenuates NF-kB as we observed, then BPDE-induced NF-kB activation is expected to be associated with up-regulation of PKC. But we observed that BPDE has practically no effect on PKC. In response to the first issue it is explainable by the facts that either NF-kB activation by BPDE is an associated phenomenon having no relevance to the cell transformation process or the predictive assignment of the role of NF-kB toward cell transformation based on its activation status is complicated. The validity of the later explanation resides in the following observation by others. It is observed that TNF-alpha induced JB6 cell transformation efficiency is increased in a dose-dependent manner up to a maximum associated with a threshold value of NF-κB activation beyond which TNF-alpha-induced cell death is noticed [38]. It needs further investigation to examine whether the increased level of NF-kB activation above the threshold value has any correlation with cell death. Increase of NF-κB activity up to a certain limit (depends on cell type) in response to cellular insults may have positive correlation with cell transformation, whereas beyond that limit further increase of NF-kB activity may be associated with a completely opposite end point as cell death. If BPDE-induced NF-κB activation status in JB6 cells is beyond the aforementioned threshold limit which is indicative of induction of cell death, then attenuation of NF-κB will inhibit apoptotic cell death thereby favoring cell transformation process. As a partial support of this view we previously observed that BPDE indeed induces apoptotic cell death in JB6 cells [42]. In further support of our view it is also observed that NF-κB has dual roles towards apoptotic cell death function because as a transcription factor it can protect or contribute to apoptosis [43]. Taken together this indicates that NF-κB activation may be beneficial or detrimental in context with cell transformation. Regarding the second issue although PKC is observed to have a role in the activation of NF-κB [39–41] it is not the only regulatory determinant of NF-κB activation. NF-κB can be activated by other signaling molecules without any involvement of PKC [44–47]. So, it is quite possible that BPDE may induce NF-κB activity without up-regulating PKC. Once NF-κB is activated by BPDE in a PKC-independent manner, any further attempt to inhibit constitutive PKC activity (as we observed with TSC phenolic fraction in presence of BPDE) may negatively regulate NF-κB activation.

In conclusion, data obtained from our present study indicate that inhibition of PKC activity by TSC phenolic fraction may have a role in potentiation of tumorigenicity by BPDE, an ultimate carcinogenic metabolite of the PAH benzo(a)pyrene. Further studies are needed to confirm NF-kB’s role in this regard.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant R15CA125630 (to (JJM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Blacklock JWS. Production of lung tumors in rats by 3:4 benzpyrene, methylcholanthrene and condensate from cigarette smoke. Brit. J. Cancer. 1957;11:181–191. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1957.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block FG, Moore GE. Carcinogenic activity of cigarette-smoke condensate. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1959;22:401–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelberth-Holm J, Ahlmann J. Production of carcinoma in ST/Eh mice with cigarette tar. Acta. Path. Et microbiol. Scandinav. 1957;41:267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1957.tb01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammer D, Woodhouse DL. Biological tests for carcinogenic action of tar from cigarette smoke. Brit. J. Cancer. 1956;10:49–53. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1956.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orris L, Van Durren BL, Kosak AI, Nelson N, Schmitt FL. Carcinogenicity for mouse skin and aromatic hydrocarbon content of cigarette-smoke condensate. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1958;21:557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugiura K. Experimental production of carcinoma in mice with cigarette smoke tar. Gann. 1956;47:243–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynder EL, Graham EA, Corninger B. Experimental production of carcinoma with cigarette tar. Cancer Res. 1953;13:855–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stedman RL. The chemical composition of tobacco and tobacco smoke. Chem. Rev. 1968;68:153–207. doi: 10.1021/cr60252a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann D, Hecht SS. Advances in tobacco carcinogenesis. In: Cooper CS, Grover PL, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol 94/1. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 63–102. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecht SS. Approaches to chemoprevention of lung cancer based on carcinogens in tobacco smoke. Environ. Hlth. Perspect. 1997;105:955–963. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelkonen O, Nebert DW. Metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: etiologic role in carcinogenesis. Pharmacol. Rev. 1982;34:189–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stampfer MR, Bartley JC. Induction of transformation and continuous cell lines from normal human mammary epithelial cells after exposure to benzo(a)pyrene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:2394–2398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey RG. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Chemistry and Carcinogenicity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. p. 396. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Durren BL. Identification of some polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette-smoke condensate. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1958;21:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gellhorn A. The carcinogenic activity of cigarette tobacco tar. Cancer Res. 1958;18:510–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roe FJC, Salaman MH, Cohen J. Incomplete carcinogens in cigarette-smoke condensate: Tumor-promotion by a phenolic fraction. Brit. J. Cancer. 1959;13:623–633. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1959.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bock FG, Swain AP, Stedman RL. Composition studies on tobacco. XLIV. Tumor-promoting activity of subfractions of the weak acid fraction of cigarette smoke condensate. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1971;47:429–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chemistry and analysis of tobacco smoke, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 1986;38:83–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamph WW, Wamsley P, Sassone-Corsi P, Verma IM. Induction of proto-oncogene JUN/AP-1 by serum and TPA. Nature. 1988;334:629–631. doi: 10.1038/334629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee W, Mitchell P, Tjian R. Purified transcription factor AP-1 interacts with TPA-inducible enhancer elements. Cell. 1987;49:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90612-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita M, Ashino S, Oshima Y, Kawamura S, Ohuchi K, Takayanagi M. Inhibition of TPA-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation and production of NO and PGE2 by the anti-rheumatic gold compounds. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003;55:245–251. doi: 10.1211/002235702513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Steer JH, Joyce DA, Yip KH, Zheng MH, Xu JJ. 12-O- tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing RANKL-induced NF-kappaB activation. Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2159–2168. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.12.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menegazzi M, Guerriero C, Carcereri de Prati A, Cardinale C, Suzuki H, Armato U. TPA and cycloheximide modulate the activation of NF-kappa B and the induction and stability of nitric oxide synthase transcript in primary neonatal rat hepatocytes. FEBS-Lett. 1996;379:279–285. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, Johnston T, Jeon H, Ibrahim M, Ranjan D. Cyclosporin A activates NF-kappaB in EBV infected human B cells and promotes EBV-B cell transformation. Journal of Surgical Research. 2006;130:319–320. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaoka S, Inoue H, Sakurai M, Sugiyama T, Hazama M, Yamada T, Hatanaka M. Constitutive activation of NF-kappa B is essential for transformation of rat fibroblasts by the human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:873–887. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sur I, Ulvmar M, Jungedal R, Toftgård R. Inhibition of NF-kappaB signaling interferes with phorbol ester-induced growth arrest of keratinocytes in a TNFR1-independent manner. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2009;29:44–51. doi: 10.1080/10799890802679876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen LA, Monteiro-Riviere NA, Smart RC. Differential Down-Regulation of Epidermal Protein Kinase C by 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate and Diacylglycerol: Association with Epidermal Hyperplasia and Tumor Promotion. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5740–5745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Z, Hornia A, Jiang YW, Zang Q, Ohno S, Foster DA. Tumor promotion by depleting cells of protein kinase C delta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:3418–3428. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mischak H, Goodnight J, Kolch W, Martiny-Baron G, Schaechtle C, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Pierce JH, Mushinski JF. Overexpression of protein kinase C-delta and -epsilon in NIH3T3 cells induces opposite effects on growth, morphology, anchorage dependence and tumorigenicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:6090–6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe T, Ono Y, Taniyama Y, Hazama K, Igarashi K, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Cell division arrest induced by phorbol ester in CHO cells overexpressing protein kinase C-delta subspecies. PNAS. 1992;89:10159–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths G, Garrone B, Deacon E, Owen P, Pongracz J, Mead G, Bradwell A, Watters D, Lord J. The polyether bistratene A activates protein kinase C-delta and induces growth arrest in HL60 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;222:802–808. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohmori S, Shirai Y, Sakai N, Fujii M, Konishi H, Kikkawa U, Saito N. Three Distinct Mechanisms for Translocation and Activation of the δ Subspecies of Protein Kinase C. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18:5263–5271. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerda SR, Bissonnette M, Scaglione Sewell B, Lyons MR, Khare S, Mustafi R, Brasitus TA. PKC-delta inhibits anchorage-dependent and -independent growth, enhances differentiation, and increases apoptosis in CaCo-2 cells. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1700–1712. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kin Y, Shibuya M, Maru Y. Inhibition of protein kinase C delta has negative effect on anchorage-independent growth of BCR-ABL-transformed Rat1 cells. Leuk Res. 2001;25:821–825. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kischel T, Harbers M, Stabel S, Borowski P, Müller K, Hilz H. Tumor promotion and depletion of protein kinase C in epidermal JB6 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1989;165:981–987. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kischel T, Harbers M, Stabel S, Borowski P, Müller K, Hilz H. Tumor promotion and depletion of protein kinase C in epidermal JB6 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:981–987. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li JJ, Westergaard C, Ghosh P, Colburn NH. Inhibitors of both nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1 activation block the neoplastic transformation response. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3569–3576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzukawa K, Weber TJ, Colburn NH. AP-1, NF-kappa-B, and ERK activation thresholds for promotion of neoplastic transformation in the mouse epidermal JB6 model. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:865–870. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silberman DM, Zorrilla-Zubilete M, Cremaschi GA, Genaro AM. Protein kinase C-dependent NF-κB activation is altered in T-cells by chronic stress. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1744–1754. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5058-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Essential role of RelA Ser311 phosphorylation by ζ-PKC in NF-κB transcriptional activation. The EMBO Journal. 2003;22:3910–3918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin AG, San-Antonio B, Fresno M. Regulation of NF-κB transactivation. Implication of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and PKCζ in c-Rel activation by TNFα. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15840–15849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee JJ, Gupta SK, Kumar S. Inhibition of benzopyrene-diol-epoxide (BPDE)-induced bax and caspase-9 by cadmium: Role of mitogen activated protein kinase. Mutation Research. 2009;661:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foo SY, Nolan GP. NF-κB to the rescue: RELs, apoptosis and cellular transformation. Trends Genet. 1999;15:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryan KM, Ernst MK, Rice NR, Vousden KH. Role of NF-κB in p53-mediated programmed cell death. Nature. 2000;404:892–897. doi: 10.1038/35009130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohuslav J, Chen L, Kwon H, Mu Y, Greene WC. p53 Induces NF-κB Activation by an I-κB Kinase-independent Mechanism Involving Phosphorylation of p65 by Ribosomal S6 Kinase 1. The journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:26115–26125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meichle A, Schutze S, Hensel G, Brunsing D, Kronke M. Protein kinase C-independent activation of nuclear factor kappa B by tumor necrosis factor. J-Biol-Chem. 1990;265:8339–8343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schulze-Osthoff K, Ferrari D, Riehemann K, Wesselborg S. Regulation of NF-kappa B activation by MAP kinase cascades. Immunobiology. 1998;198:35–49. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(97)80025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong Z, Birrer MJ, Watts RG, Matrisian LM, Colburn NH. Blocking of tumor promoter-induced AP-1 activity inhibits induced transformation in JB6 mouse epidermal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:609–613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwon JY, Lee KW, Hur HJ, Lee HJ. Peonidin Inhibits Phorbol-Ester–Induced COX-2 Expression and Transformation in JB6 P+ Cells by Blocking Phosphorylation of ERK-1 and −2. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1095:513–520. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith BM, Colburn NH. Protein Kinase C and Its Substrates in Tumor Promoter sensitive and -resistant Cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:6424–6431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsu TC, Young MR, Cmarik J, Colburn NH. Activator protein 1 (AP-1)– and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)–dependent transcriptional events in carcinogenesis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;28:1338–1348. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhar A, Young MR, Colburn NH. The role of AP-1, NF-kappaB and ROS/NOS in skin carcinogenesis: the JB6 model is predictive. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2002;234/235:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]