Abstract

Background

Viliuisk encephalomyelitis is a disorder that starts, in most cases, as an acute meningoencephalitis. Survivors of the acute phase develop a slowly progressing neurologic syndrome characterized by dementia, dysarthria, and spasticity. An epidemic of this disease has been spreading throughout the Yakut Republic of the Russian Federation. Although clinical, neuropathologic, and epidemiologic data suggest infectious etiology, multiple attempts at pathogen isolation have been unsuccessful.

Methods

Detailed clinical, pathologic, laboratory, and epidemiologic studies have identified 414 patients with definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis in 15 of 33 administrative regions of the Yakut Republic between 1940 and 1999. All data are documented in a Registry.

Results

The average annual Viliuisk encephalomyelitis incidence rate at the height of the epidemic reached 8.8 per 100,000 population and affected predominantly young adults. The initial outbreak occurred in a remote isolated area of the middle reaches of Viliui River; the disease spread to adjacent areas and further in the direction of more densely populated regions. The results suggest that intensified human migration from endemic villages led to the emergence of this disease in new communities. Recent social and demographic changes have presumably contributed to a subsequent decline in disease incidence.

Conclusions

Based on the largest known set of diagnostically verified Viliuisk encephalomyelitis cases, we demonstrate how a previously little-known disease that was endemic in a small indigenous population subsequently reached densely populated areas and produced an epidemic involving hundreds of persons.

In 1854, geographer and ethnologist Richard Maak first described an unusual “weakening” (paralyzing) disease during his travel through Viliui villages.1 The initial medical characterization of the disorder was made in 1925–1926 by a medical team from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic’s Ministry of Health who were conducting an epidemiologic survey of the Viliui region.2 They described a chronic neurologic syndrome in 16 patients with onset of illness between 1891 and 1925. An outbreak of the disease, subsequently named Viliuisk encephalomyelitis, was observed in this same area from 1951 through 1958.3,4 By the mid-1960s, Viliuisk encephalomyelitis was detected in a much wider area, including densely populated regions of the Yakut Republic.4–6

Viliuisk encephalomyelitis is clinically and pathologically defined as a progressive meningoencephalitis that starts acutely with delirium or somnolence, meningism, bradykinesia, and disturbances of coordination lasting several weeks to several months.7,8 Some patients die in the acute phase; survivors develop a slowly progressing neurologic syndrome characterized by dementia, dysarthria, spasticity, muscle rigidity, and cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis–all lasting up to 6 years. Many patients die in this interval, but some remain in a steady state of global dementia and severe spasticity for 20 years or longer.7,8 Postmortem studies have shown diffuse infiltration of the meninges and the presence of multiple micronecrotic foci throughout the gray matter of the brain, surrounded by T- and B-lymphocytes and reactive astrocytes.9 Multiple attempts to isolate the causal agent from patients’ brain tissue have thus far been unsuccessful.7,8

The purpose of this study is to identify all cases of definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis that occurred from 1940 to 1999, in all regions of the Yakut Republic, to describe the general characteristics of this epidemic, and to examine the source and mechanisms of disease transmission and spread.

METHODS

Study Population

The vast and sparsely populated territory of the Yakut (Sakha) Republic, with an area of 3,100,000 km2 (almost as large as Western Europe), is located in northeastern Siberia at latitudes between 109E and 162E, and longitudes between 55N and 73N (Fig. 1). This region is the coldest area in the Northern hemisphere, with average January temperatures near −50°C and a world record of −71°C (−96°F). Yakutia is abundantly rich in raw materials, with diamond, gold, and tin ore mining industries being the major focus of the economy.

FIGURE 1.

Map of North-East Asia showing the area of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis distribution.

The Yakut (Sakha) population originated from a nomadic Central Asian tribe that migrated to northeastern Siberia 600–900 years ago under pressure from the Mongol expansion. The newcomers brought a dialect of Turkic language and a culture of breeding horses and cattle.10 By the 17th century, the Yakut people still lived in a relatively small area of the Lena-Amga valley (currently Central Yakutia). The land around these Yakut settlements was occupied by Evenks and Evens, who were reindeer-herder and hunters.10 The Yakuts were settled in villages with a relatively developed economy that was less affected by severe climatic conditions. Indigenous population groups were assimilated into the Yakuts. Remnants of the Evenk tribes in this region now speak the Yakut language and practice a Yakut-style economic lifestyle. The population of the middle reaches of Viliui River, where the Viliuisk encephalomyelitis epidemic began, was different from Yakuts in other regions, as the Viliui Yakuts were generally more liberal toward the local Evenk tribes and more readily accommodated and assimilated them.10 The Yakut-speaking population grew from 28,500 at the end of the 17th century to 225,000 at the end of the 19th century,11 to 432,000 in 2002. The Tsarist and Soviet Governments restricted movements of people by controlling interregional migration. Thus, the 1926 Census showed that 99% of the rural population lived their lives in either the village where they were born or in a neighboring village. However, after World War II, when the development of Siberian resources began to intensify, the local population was allowed to migrate to industrial centers and to regions more favorable for agricultural development.11

Case Definition and Ascertainment

The clinical diagnosis of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis is difficult because of clinical heterogeneity of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis and its occurrence in a region where several other neurodegenerative disorders have been prevalent.12 Diagnostic criteria were proposed in 19523 and slightly revised in 1965.12 Three patterns of definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis have been identified. The first is a rapidly progressive (acute) illness characterized by fever, confusion, coma or delirium, cerebral spinal fluid pleocytosis with elevated protein concentration, and fatal outcome within 12 months. (Neuropathologic confirmation is required.) Second is a slowly progressive disease in patients who survived the meningoencephalitic phase and developed progressive dementia, dysarthria, pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs, cerebral spinal fluid pleocytosis, and elevated protein concentration; it is fatal within 1–6 years after onset with no remissions. In typical cases, clinical data are generally sufficient for the diagnosis. Third is a prolonged disease (overall duration more than 6 years) that may start as an acute meningoencephalitis or develop insidiously and present as a diffuse brain syndrome with dementia, characteristic dysarthria, lower spastic paraparesis or quadriparesis, and no progression for extended periods; imaging characteristically shows severe diffuse brain atrophy.

Systematic studies involving the documentation and registration of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis patients were initiated in 1951 by the Neurology Department of the Viliuisk Regional Hospital.3,4 Living patients with disease onset in 1940–1949 were also registered. A second research center was established in the Republican Hospital in the city of Yakutsk in the early 1960s, when it has become clear that Viliuisk encephalomyelitis appeared in regions other than Viliui Valley.5 Research on Viliuisk encephalomyelitis attracted scientists from several Moscow and Sankt-Petersburg research institutions who accumulated a vast amount of data.13,14 These clinical and epidemiologic records were made available for the current study. In addition to reviewing records, more than 90% of the surviving registered patients were personally examined by at least one of the coauthors (V.V., F.P., A.D., R.N., D.C.G., or L.G.G.). Traveling groups of neurologists and epidemiologists periodically visited every affected village for detection of new patients. Each patient was periodically admitted to the Yakutsk Viliuisk encephalomyelitis diagnostic center for evaluation.

Of more than 1400 fully studied patients with suspected Viliuisk encephalomyelitis, 414 met diagnostic criteria for definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis and were included in the Registry upon which this study is based. Data were collected on date and place of birth, ethnicity, the exact or approximate (up to 4 weeks) date of disease onset, the location where the patient lived at the time of disease onset, household census and relationships, history of travel, and date of death. A 4-page clinical chart describing symptoms of the acute and chronic phases of illness and the results of laboratory, imaging, and neuropathologic studies was available for each Registry entry. Thirty-six patients studied pathologically (9% of patients in the Registry). Recently, oligoclonal analysis of the cerebral spinal fluid was introduced as an associated diagnostic test considering that almost all patients with definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis show intrathecal IgG bands in each stage of illness.15 The Registry was computerized in 1999.

Studies were performed under clinical protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Yakut (Sakha) Institute of Health and the US National Institutes of Health. The protocol was subsequently reviewed and approved by the Office for Protection from Research Risks, US Department of Health and Human Services. Informed consent was obtained for each element of this study.

Statistical Evaluation

Average annual Viliuisk encephalomyelitis incidence rates for each decade (1940–1949, 1950–1959, 1960–1969, 1970–1979, 1980–1989, and 1990–1999) was determined based on the number of cases that occurred within the specific decade. The population denominators in incidence rate estimations were obtained by interpolating the Yakut Republic Census data for 1949, 1954, 1959, 1970, 1979, 1989, and 2002. Data for the 7 Census years spanning 5 decades show steady growth of overall population size in the areas affected with Viliuisk encephalomyelitis (from 82,276 to 136,922).

The first registered Viliuisk encephalomyelitis cases occurred in several small villages around Lake Mastakh.1–4 Assuming that this was the epicenter of the initial outbreak, we estimated the spread to subsequently affected villages by measuring distance using Google Earth version 4.2 (available at: http://earth.google.com/). The decade-by-decade averages of these distances were calculated and compared using Student t test to evaluate the hypothesis that more distant villages were affected in later decades.

RESULTS

Trends in Incidence

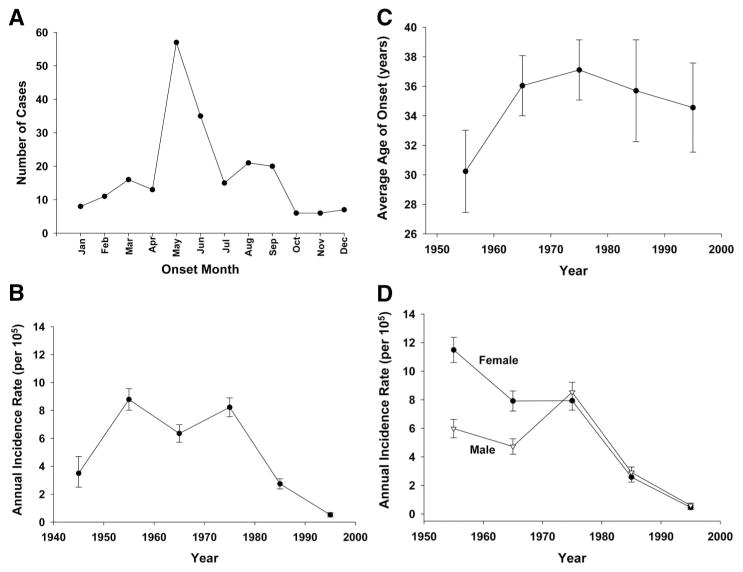

The database including 414 patients diagnosed with definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis was verified for errors, completeness, and duplicates before analysis of the data was initiated. All registered patients were born in small villages. All patients were ethnic Yakuts, except for 6 Evenks and 6 born from Yakut-Evenk mixed marriages. Most cases had disease onset in May, June, July, or August (60% of 215 cases with known day/week of disease onset) (Fig. 2A). This may be due to more intensive outdoor activities such as hunting, fishing, and farming that expose people to environmental factors that provoke the onset of illness.

FIGURE 2.

Basic characteristics of the Viliuisk encephalomyelitis epidemic in Eastern Siberia. A, monthly distribution of disease onsets, average for VE cases registered in 1950–1999; B, average annual incidence rate per 100,000 population decade-by-decade within 1940–1999; C, average age of disease onset in consecutive time intervals; D, average sex-dependent annual incidence rate. The 1940–1949 interval is represented by surviving patients who were diagnosed and registered in 1951. Vertical lines represent 95% CIs.

The average annual incidence rate of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis was at 3.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.5–4.7) cases per 100,000 population in 1940–1949. It increased to 8.8 (8.0–9.6) in 1950–1959 and remained at an elevated level of 6.4 (5.7–7.0) in 1960–1969 and 8.2 (7.6–8.9) in the 1970s. In the 1980s, incidence declined to 2.7 (2.4–3.1) and further to 0.5 (0.4–0.8) in the 1990s (Fig. 2B). Age of disease onset varied between 11 and 68 years; the mean age of onset was youngest in the beginning of the epidemic (30.2 years, 27.5–33.0) and increased to 37.1 years (35.1–39.1) at the height of the epidemic in 1970–1979 (Fig. 2C). The female-to-male ratio changed from a 2:1 female excess during the 1950s and 1960s to an approximately equal annual incidence rate among women and men in later decades (Fig. 2D). The excess of female morbidity coincided with a higher frequency of clinical forms characterized by acute onset and rapid progression of illness. The shifts in incidence rate, mean age at disease onset, and female-to-male ratio over the course of the epidemic are likely related to changing environmental factors.

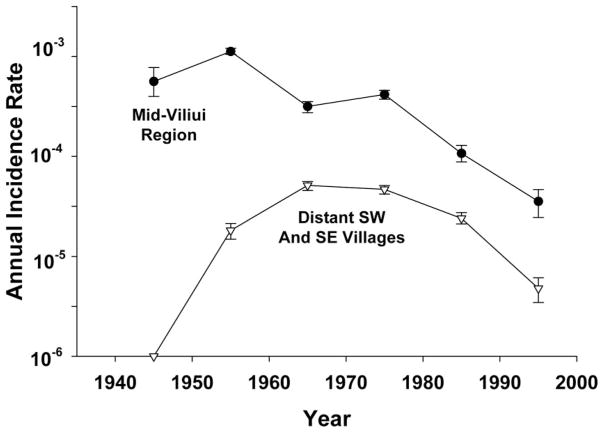

Geographic Spread

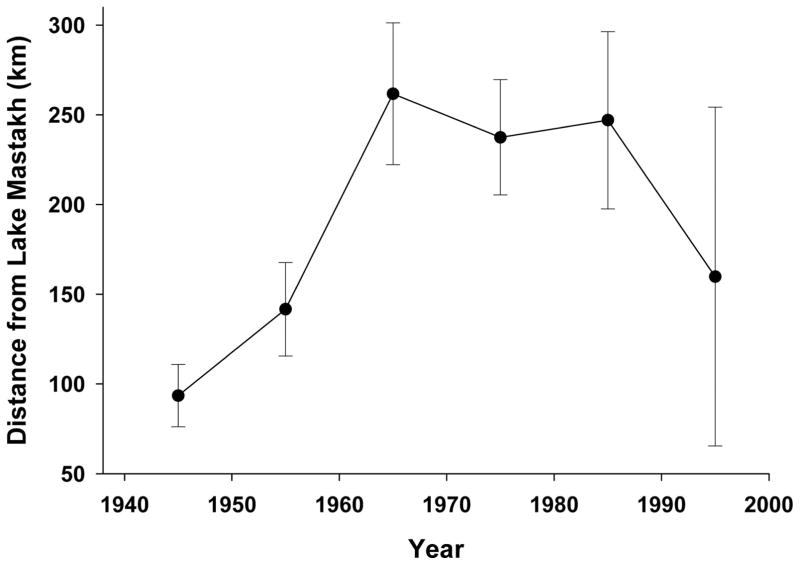

Viliuisk encephalomyelitis patients have been identified in 110 of 295 known villages with population sizes from 250 to 3000 individuals, located in 15 of 33 administrative regions of the Yakut Republic. Twenty-three patients lived in larger towns or cities at the time of disease onset and were not considered for geographic analysis because city patients were recent immigrants from villages. According to historic evidence, the first 16 cases were identified in villages around Lake Mastakh,2 and 2 decades later the 1940–1959 outbreak occurred in this same area.3,4 Subsequent cases occurred in progressively distant villages (Fig. 3); they were 94 km away from Lake Mastakh in 1940–1949, 142 km in 1950–1959, 262 km in the 1960s, and at similar distances in the next decade. The epidemic expanded toward the more densely populated southwestern Upper-Viliui industrial region and the central part of the Republic near the capital city of Yakutsk (Fig. 4). The overall number of affected villages grew from 4 in 1940–1949 to 18 in 1950–1959 to 52 in 1970–1979, and the affected territory has increased 15-fold (Fig. 4). The villages affected in 1980–1989 and 1990–1999, during the time of a substantial decline in Viliuisk encephalomyelitis incidence rates, are located closer to the original Mid-Viliui region (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 3.

Distance (in km) between the area of the initial Viliuisk encephalomyelitis outbreak (Lake Mastakh) and villages newly affected in subsequent decades. Vertical lines represent 95% CIs.

FIGURE 4.

Location of villages in which new patients with Viliuisk encephalomyelitis were identified within each of epidemic time periods. The 1940–1949 interval is represented by surviving patients who were diagnosed and registered in 1951.

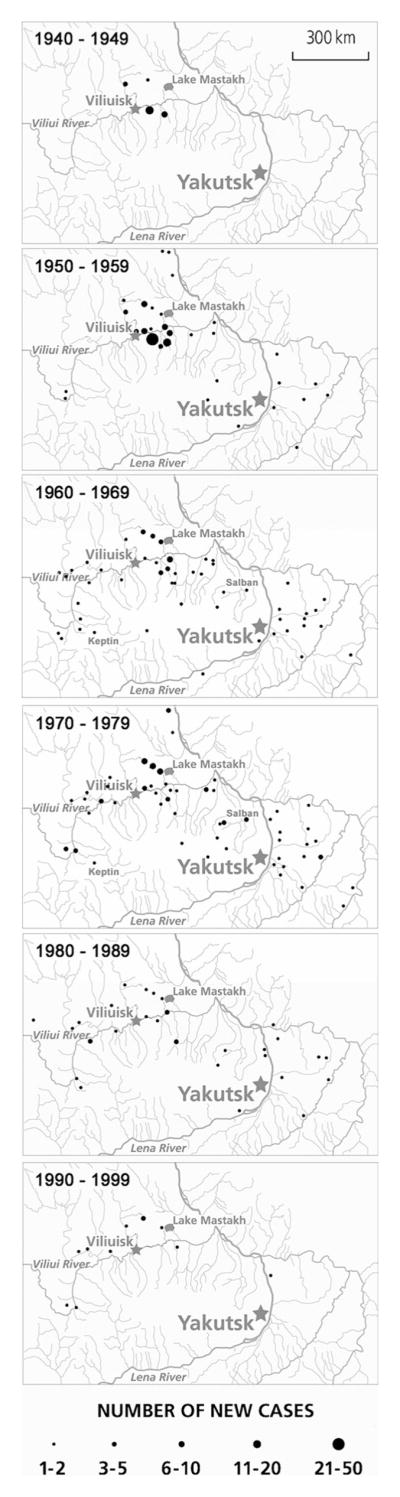

Epidemic curves reflecting decade-by-decade average annual incidence rate in the mid-Viliui region and the distant spill-over villages in the southwestern and southeastern densely populated territories (Fig. 5) indicate that Viliuisk encephalomyelitis incidence rate in the mid-Viliui region had already reached its highest level when studies were initiated. The disease was present in the mid-Viliui area for the next 50 years, albeit at decreasing levels, but the annual incidence rate still remains at 3.3 cases per 100,000 population. In contrast, the initial incidence rate in the distant villages was zero, it steadily grew to a rate of 27 (95% CI = 24.5–30.4) cases per 100,000 population in the 1970s, and subsequently decreased to a negligible number in the 1990s.

FIGURE 5.

Average annual incidence rate of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis in the Mid-Viliui region (filled circles) and newly affected villages along the route of population migration to the South-West and South-East densely populated regions (triangles). The 1940–1949 interval is represented by surviving patients who were diagnosed and registered in 1951. Vertical lines represent 95% CIs.

The Patterns of Accumulation of Cases in Households and Newly Affected Villages

Yakut families are large and have a complex structure. Adoption of young, old, and chronically sick community members is a longstanding Yakut tradition providing additional chances for survival in severe natural environments.9 Multiple cases of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis per household were observed more frequently than could be explained by chance; of the 1090 households we studied in 6 mid-Viliui villages, 48 were affected, 15 of them having 2 or more Viliuisk encephalomyelitis patients (Table). The observed number of households with 2 or more cases was much higher (P = <0.0001) than expected given the Viliuisk encephalomyelitis prevalence of 1.6% in these 6 villages at the time of the study. Numerous examples of disease transmission to nongenetic relatives as a result of residential exposure indicate that accumulation of cases in the households is mostly due to environmental rather than genetic risk. Most commonly, a household member would contract the disease after a prolonged cohabitation with an already ill Viliuisk encephalomyelitis patient. These observations suggest that horizontal disease transmission may be occurring within households to related or unrelated members.

TABLE.

Observed and Expected Number of Families With 0, 1, and 2 or More Viliuisk Encephalomyelitis Patients in Mid-Viliui Region

| No. Cases per Household | Observed | Expected |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1042 | 1026 |

| 1 | 33 | 62 |

| 2+ | 15a | 2 |

| Total | 1090 | 1090 |

Expected numbers are calculated based on the overall Viliuisk encephalomyelitis prevalence rate of 1.64% in the 6 Mid-Viliui villages at the time of the study.

Binomial P = <0.0001.

The spread of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis into more densely populated and more developed areas has occurred through documented massive migration. The majority of known migrant patients came from high-risk regions during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Doctors did not encounter Viliuisk encephalomyelitis outside of the mid-Viliui region before World War II, and there was no folk name for the disease anywhere outside of the mid-Viliui region; when the illness appeared in the central part of the country, it was called “Viliui disease” and subsequently “Viliuisk encephalomyelitis.” Analysis of data related to 4 newly affected villages established a chain of cases that started with immigrants from high-risk areas and involved local residents who never left their home village.16 In the village of Salban (Fig. 4), a migrant worker developed Viliuisk encephalomyelitis in 1960, 21 years after his resettlement from a Viliui village. His 2 local consecutive wives developed the disease in the 1970s. Two further cases were identified in other villagers. All 5 patients were classified as definite Viliuisk encephalomyelitis. In Keptin, another newly affected village (Fig. 4), Viliuisk encephalomyelitis was initially diagnosed in 2 women migrating from Viliui; both were affected at the time of resettlement. Subsequently, in the 1960s and 1970s, 3 villagers who were not known to dwell with the newcomers but who spent summers living with them in agricultural camps, also developed the disease.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed annual incidence rates and other characteristics of the Viliuisk encephalomyelitis epidemic in Eastern Siberia using a large dataset of patients with clinically and pathologically confirmed diagnoses. Cases were identified during a 60-year period from 1940 to 1999. The annual incidence rate at the height of the epidemic reached or exceeded levels characteristic of better known neurologic disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, hereditary ataxias, spastic paraplegias, or hereditary neuropathies. The disease affected predominantly young adults; in the initial phase of the epidemic the age of disease onset was younger, and young women were affected twice as often as men, similar to the sex ratio seen in multiple sclerosis.17 The average age of disease onset and the female-to-male ratio changed in the later years when chronic Viliuisk encephalomyelitis became the predominant clinical type of illness.18

Analysis identified the mid-Viliui region near Lake Mastakh as the original source of the Viliuisk encephalomyelitis epidemic. The disease later spread to neighboring regions and eventually to distant localities within more densely populated southwestern territories along the Viliui River and the central region of the Yakut Republic near the capital city of Yakutsk, with many new cases occurring in the local populations. The spread of VE occurred at a time of extensive and well documented human migration after World War II, when resettlement was allowed and, in fact, encouraged by the Soviet Government to promote rapid development of newly discovered mineral resources.11 The recent retraction of the disease to mid-Viliui areas suggests that the Viliui region has more stable Viliuisk encephalomyelitis foci, with perhaps easier human-to-human or animal-to-human transmission due to cultural traditions, economic circumstances or natural environment. The factors that led to gradual decline in disease incidence in the 1980s and 1990s include social and demographic changes that occurred in the country within the past 20 years and efforts at isolating patients with acute and slowly progressing forms of VE in specialized hospitals and a nursing home.

The spread of the disease to populations living in more economically developed villages of the central part of the Republic indicates that the causative agent or natural hosts may have been carried with the migrating mid-Viliui population. Although poverty, overcrowded conditions, poor diet, and unclean drinking water have long been associated with an increased risk,4 we find that educated and economically well-off families in better developed areas also contracted Viliuisk encephalomyelitis.

In conducting this analysis, we considered a range of hypotheses that have been proposed for the causation and transmission of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis. These include (1) a genetic hypothesis, stating that Viliuisk encephalomyelitis is a Mendelian disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance19; (2) a geobiochemical hypothesis, based on unusual biochemical features of the soil around Lake Mastakh and some areas along the Viliui River20; (3) an ecologic hypothesis that local ecologic systems of the Viliui region support circulation of an agent that causes Viliuisk encephalomyelitis21; and (4) a hypothesis that immune deficiencies in local population of the mid-Viliui region confer increased susceptibility to a ubiquitous Viliuisk encephalomyelitis agent.22 These hypotheses are effectively excluded by the evidence that the disease moved to genetically distinct populations (that have not intermarried with Evenks) and away from regions with biochemical or ecologic abnormalities, toward populations having diverse food sources and clean water supply. The recent disappearance of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis from the areas affected in later phases of the epidemic additionally confirms that the disease is not a genetically predetermined condition.

The fact that Viliuisk encephalomyelitis is a slowly developing meningoencephalitis with increased cerebral spinal fluid cell count and protein concentration, and overt inflammatory changes in the brain,8 suggest that Viliuisk encephalomyelitis represents an infectious disease with unusual features. Most likely, the disease is caused by an unconventional organism, which would explain the difficulty of its isolation and identification. The observations that cases aggregate in households and small newly affected villages suggest that Viliuisk encephalomyelitis is a transmissible disease, although alternative explanations such as seasonal or nonseasonal shared household effects cannot be excluded.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the BioTechnology Engagement Program of the US Department of Health and Human Services and also by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health.

We are grateful to the affected families for their enthusiastic participation in this study. We acknowledge the contribution of numerous physicians and scientists who made their nonpublished data available for analysis.

References

- 1.Maak RK. Viliuiskii okrug Yakutskoi oblasti [The Viliuisk area of the Yakutsk oblast] Vol. 3. Sankt-Petersburg, Russian Federation: University Press; 1887. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolpakova TA. Epidemiologicheskoe obsledovanie Viliuiskogo okruga Yakutskoi SSR [Epidemiological survey of the Viliuisk area, Yakut SSR] Leningrad: Transactions of a Governmental Commission for Investigations in the Yakut SSR; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrov PA. Viliuiskii entsefalit (entsefalomielit) [Viliuisk encephalitis (encephalomyelitis)]. S.S. Korsakov’s. J Neurol Psychiat (Russian) 1958;58:669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrov PA. Klinicheskaia kartina ostroi stadii Viliuiskogo entsefalita (entsefalomielita) [Clinical features of the acute stage of Viliuisk encephalitis (encephalomyelitis)] Yakutsk, Russian Federation: Yakutsk Publishing House; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vladimirtsev AI. Khronicheskii Yakutskii (Viliuiskii) entsefalit po materialam nevrologicheskogo otdeleniia Respublikanskoi bol’nitsy za 12 let [Chronic Yakut (Viliuisk) encephalitis during 12 years in records of the Neurology Service of the Republican Hospital] Bull Yakutsk Republican Hosp. 1964;9:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldfarb LG, Fedorova NI, Chumakov MP, et al. Sootnoshenie nasledstvennosti i sredovykh faktorov v etiologii Viliuiskogo entsefalomielita. 1. Chastota bol’nykh v semiakh [Heredity and environment in the etiology of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis. 1. Affected families] Genetika (Russian) 1979;15:1502–1512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldfarb LG, Gajdusek DC. Viliuisk encephalomyelitis in the Iakut population of Siberia. Brain. 1992;115:961–978. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.4.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vladimirtsev VA, Nikitina RS, Renwick N, et al. Family clustering of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis in traditional and new geographic regions. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1321–1326. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.061585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean CA, Masters CL, Vladimirtsev VA, et al. Viliuisk encephalomyelitis - review of the spectrum of pathological changes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1997;23:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pakendorf B, Novgorodov IN, Osakovskij VL, et al. Investigating the effects of prehistoric migrations in Siberia: genetic variation and the origins of Yakuts. Hum Genet. 2006;120:334–353. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedorova EN. Naselenie Yakutii: Proshloe I Nastoiashchee [Population of Yakutia: Past and Present] Novosibirsk, Russian Federation: Nauka; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chumakov MP, Goldfarb LG, Sarmanova ES, et al. Epidemiology of Noninfectious Diseases. Vol. 19. Irkutsk, Russian Federation: Irkutsk Medical School Proceedings; 1971. Predvaritel’nye rezul’taty izucheniia epidemiologii Viliuiskogo entsefalomielita [Preliminary results of epidemiologic studies of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis] pp. 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapoval AN, Sarmanova ES. O svoeobraznoi forme entsefalita [A peculiar form of encephalitis] Clin Med (Russian) 1955;33:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapoval AN. Viliuiskii entsefalomielit [Viliuisk encephalomyelitis] Yakutsk, Russian Federation: Yakutsk Publishing House; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green AJE, Sivtseva TM, Danilova AP, et al. Viliuisk encephalomyelitis: intrathecal synthesis of oligoclonal IgG. J Neurol Sci. 2003;212:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldfarb LG, Spitsyn VA, Fedorova NI, et al. Sootnoshenie nasledstvennosti i sredovykh faktorov v etiologii Viliuiskogo entsefalomielita. 2. Populliatsionno-geneticheskoeissledovanie v raionakh rasprostraneniia Viliuiskogo entsefalomielita [Heredity and environment in the etiology of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis. 2. Population-genetic studies] Genetika (Russian) 1979;15:1513–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso A, Jick SS, Olek MJ, Hernán MA. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in the United Kingdom: findings from a population-based cohort. J Neurol. 2007;254:1736–1741. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alekseev VP, Krivoshapkin VG, Makarov VN. Geographia Viliuiskogo Entsefalomielita [Geography of Viliuisk Encephalomyelitis] Yakutsk, Russian Federation: Institute of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zubri GL, Umanskii KG, Savinov AP, et al. O nozologicheskoi prinadlezhnosti bokhorora [Nozological classification of bokhoror] Genetika (Russian) 1977;13:1843–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avtsyn AP. Vvedenie v geograficheskuiu patologiiu [Introduction to geographical pathology] Moscow: Meditsina; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubov AV, Vladimirtsev VA, Alekseev VP, et al. Ekologicheskaya gipoteza Viliuiskogo entsefalomielita [Ecological hypothesis of Viliuisk encephalomyelitis]. Proceedings of a Republican Conference on Hygiene and Health; Yakutsk, Russian Federation. 1993. pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Autenschlus AI, Shatunov AY, Pankratov EV, et al. Immunologicheskiy status bol’nykh Viliuiskim entsefalomielitom [Immune status of patients with Viliuisk encephalomyelitis]. Proceedings of a Republican Conference on Hygiene and Health; Yakutsk, Russian Federation. 2002. pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]