Abstract

We have examined effects of the 20,23-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (20,23(OH)2D3), on differentiation and proliferation of human keratinocytes and the anti-inflammatory potential of 20,23(OH)2D3 from its action on nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). 20,23(OH)2D3 inhibited growth of keratinocytes with a potency comparable to that for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3). Cell cycle analysis showed that this inhibition was associated with G1/G0 and G2/M arrests. 20,23(OH)2D3 stimulated production of involucrin mRNA and inhibited production of cytokeratin 14 mRNA in a manner similar to that seen for 1,25(OH)2D3. Flow cytometry showed that these effects were accompanied by increased involucrin protein expression, and an increase in the cell size and granularity. Silencing of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) by corresponding siRNA abolished the stimulatory effect on involucrin gene expression demonstrating an involvement of VDR in 20,23(OH)2D3 action. This mode of action was further substantiated by stimulation of CYP24 gene expression and stimulation of the CYP24 promoter-driven reporter gene activity. 20,23(OH)2D3 displayed several fold lower potency for induction of CYP24 gene expression than 1,25(OH)2D3. Finally, 20,23(OH)2D3 inhibited the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in keratinocytes as demonstrated by EMSA, NF-κB-driven reporter gene activity assays and measurements of translocation of p65 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. These inhibitory effects were connected with stimulation of the expression of IκBα with subsequent sequestration of NF-κB in the cytoplasm and consequent attenuation of transcriptional activity. In summary, we have characterized 20,23(OH)2D3 as a novel secosteroidal regulator of keratinocytes proliferation and differentiation and a modifier of their immune activity.

Mammalian cytochrome P450scc cleaves the side chain of cholesterol producing pregnenolone from which other steroids are made (Tuckey, 2005). It is now well established from studies with the purified enzyme and the enzyme in adrenal mitochondria that cytochrome P450scc can also hydroxylate vitamins D2, D3 and their precursors ergosterol and 7-dehydrocholesterol (Guryev et al., 2003; Slominski et al., 2004, 2005a, b, 2006a, b, 2009; Tuckey et al., 2008a, b). Purified P450scc converts vitamin D3 to 20-hydroxyvitamin D3 (20(OH)D3), 20,23-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (20,23(OH)2D3) and 17,20,23-trihydroxyvitamin D3 (Slominski et al., 2005b; Tuckey et al., 2008a, b). In our recent study, we showed that the first product of this hydroxylation, 20(OH)D3, is a biologically active compound that inhibits proliferation and stimulates differentiation of human keratinocytes (Zbytek et al., 2008) and inhibits NF-κB activity (Janjetovic et al., 2009). We postulated that 20(OH)D3 and its derivatives may be produced in vivo where they could have systemic effects when produced by the adrenal cortex, corpus luteum and placenta, organs expressing high levels of P450scc (Lehmann, 2005; Slominski et al., 2005b; Tuckey, 2005). For skin, which expresses low levels of P450scc (Slominski et al., 2004), 20(OH)D3 or its metabolites (Tuckey et al., 2008a) could serve local para-, auto- or intracrine roles (Slominski et al., 2004).

The hormonally active form of vitamin D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), is produced from vitamin D3 by the action of 25-hydroxylases such as CYP27A1, in liver, followed by 1α-hydroxylation in kidneys by CYP27B1 (Holick, 2003; Feldman et al., 2005). This pathway for activation of vitamin D3 also occurs in epidermal keratinocytes which contain both CYP27A1 and CYP27B1 (Bikle et al., 1986a, b; Lehmann, 2005; Bikle, 2006; Holick, 2006). After binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR), 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts its biological activity in a cell-type specific manner with effects that include stimulation of calcium uptake (gut), modulation of the immune system, inhibition of cell proliferation, promotion of cell differentiation and apoptosis, and protection of cells against oxidative damage to their DNA (Pillai et al., 1988; Wiseman, 1993; Holick, 2003; Bikle, 2004a). The anti-proliferative and pro-differentiation activities of 1,25(OH)2D3 and structural analogues of this compound make them of interest for the treatment of cancer and other hyperproliferative disorders (Masuda and Jones, 2006). The toxic effect of hypercalcemia caused by pharmacological doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 renders this form of vitamin D of little use in cancer treatment. To overcome this problem several vitamin D analogues have been developed which have reduced calcemic activity but retain powerful antiproliferative activity (Masuda and Jones, 2006; Spina et al., 2006, 2007). These compounds act as partial receptor agonists inducing specific conformational changes in the receptor that influence which transcription factors are recruited and thus which genes are transcribed (Carlberg, 2003).

Our previous study indicates that P450scc-derived 20(OH)D3 acts through VDR as a partial receptor agonist, having antiproliferative activity on keratinocytes as potent as 1,25(OH)2D3, but unlike 1,25(OH)2D3, it only weakly stimulates the expression of the CYP24 gene (Zbytek et al., 2008). In the present study we have examined the biological activity of the product of 20(OH)D3 hydroxylation by P450scc, 20,23(OH)2D3 (Tuckey et al., 2008a), and compared it to the classical active form of vitamin D3, 1,25(OH)2D3. In our experiments we have used immortalized human HaCaT keratinocytes and primary epidermal keratinocytes, which are well-defined targets of 1,25(OH)2D3 action (Lehmann, 1997; Bikle, 2004a, b; Ren et al., 2006; Bar et al., 2007). Since it has been shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts anti-inflammatory effects on keratinocytes by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (Riis et al., 2004; Cohen-Lahav et al., 2006, 2007; Sun et al., 2006), we examined the effects of 20,23(OH)2D3 on the activity of this transcription factor.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of 20,23(OH)2D3

20,23(OH)2D3 was prepared by enzymatic hydroxylation of vitamin D3 by bovine cytochrome P450scc as described previously (Tuckey et al., 2008a). The product was purified by preparative TLC (Slominski et al., 2005b) followed by isocratic HPLC on a C18 column (Brownlee Aquapore, 22 cm × 4.6 cm, particle size 7 μm) using 70% methanol in water as mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The concentration of 20,23(OH)2D3 was determined using an extinction coefficient of 18,000 M−1 cm−1 at 263 nm (Hiwatashi et al., 1982).

Cell culture

Immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with glucose, L-glutamine, pyridoxine hydrochloride (Cell Grow), 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin antibiotic solution (Sigma) (Zbytek et al., 2003). Normal human keratinocytes (HEKn) were isolated from neonatal foreskin of African American donors using 2.5 UI/ml dispase and grown in keratinocyte basal medium (KBM) supplemented with keratinocytes growth factors (KGF) (Lonza) on collagen coated plates (Janjetovic et al., 2009). For experiments cells in their third passage were used. Prior to treatment with vitamin D3 metabolites, HaCaT cells were serum deprived for 24 h and further incubated in DMEM medium containing 5% charcoal treated serum (HyClone). For HEKn cells, 0.5% BSA solution was used when cells were treated with vitamin D3 derivatives.

Hydroxyvitamin D3 treatment of cells and [3H] thymidine incorporation

HaCaT keratinocytes were plated in 96-well plates, 10,000 cells/well. After overnight incubation of cells, 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or 20(OH)D3, initially dissolved in ethanol and then diluted in DMEM medium containing 5% charcoal treated serum, was added to the medium to achieve final concentrations of 0.1 nM or 10 nM (with the final concentration of ethanol vehicle being 0.1 μM). After 36 h of incubation with these compounds, [3H]-thymidine (specific activity 88.0 Ci/mmol; GE Healthcare, USA/Amersham Biosciences, USA) was added to a final activity of 1 μCi/ml of medium. Twelve hours later, media were discarded, cells detached with trypsin and harvested on a glass fiber filter (Packard, Meriden, CA).

[3H]-Thymidine was measured with a beta counter (Direct Beta-VCounter Matrix 9600; Packard). [3H]-Thymidine incorporation into DNA was measured in six separate experiments with measurements replicated 6 times within each experiment. The mean data from each experiment was analyzed with GraphPad Prism Version 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) using the t-test. Differences were considered significant when P <0.05.

Flow cytometry

Keratinocytes were treated with 10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol (diluted as for [3H]thymidine incorporation, above) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinisation, washed in PBS, fixed in 70% cold ethanol and stained with propidium iodine (Sigma). DNA content analysis was performed with a FACS Calibur flow cytometer. To test the stimulation of differentiation by 20,23(OH)2D3, HaCaT cells were treated the same way then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Fischer) in PBS for 1 h. Following washing with PBS, pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of permeabilizing solution containing 0.25% saponin, 0.1% BSA and 0.1% NaN3 in PBS and 0.2 μg primary antibody against involucrin (Novocastra, USA). Cells stained with isotype control antibody (IgG1, Caltag) were used as controls. After overnight incubation, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 100 μl of permeabilizing solution containing sheep anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:50, Novocastra). After 3 h of incubation cells were washed with PBS, centrifuged and resuspended in 500 μl of PBS. Samples were read with a FACS Calibur flow cytometer. FL-1 signal (collected from 10,000 events in side scatter/forward scatter window after debris exclusion) was recorded. Forward (relative to cell size) and side (relative to cell granularity) scatter were recorded. FL-1 signal values are presented as dMFI (difference between mean fluorescence intensity of sample stained with specific and isotype control antibody). Scatter signal values are presented as MSI (mean signal intensity).

Immunofluorescent staining

For involucrin immunostaining, HaCaT cells were seeded onto cover slides in 6-well plates and treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 or ethanol for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were washed in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Afterwards, cells were incubated in permeabilizing solution comprising 0.2% Triton-X 100 in PBS for 5 min, then washed with PBS and blocked in 1% BSA for 30 min. Primary antibody: mouse anti-human-involucrin (1:200 in 1% BSA), was added to the cells, which were incubated for 3 h at room temperature with shaking. After extensive washing in PBS, cells were incubated in secondary antibody solution of anti-mouse-FITC conjugate (NCL-SAM-FITC) (1:200, 1 ml of PBS with 1% BSA) for 1 h. Cells were further washed and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing propidium iodine (Vectashield). Stained cells were viewed with a fluorescent microscope and photographed under 40× magnification.

For NF-κBα immunostaining, HEKn cells were seeded onto cover glasses in 6-well plates and treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol for 24 h. Control cells were additionally treated with IL-1α (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. After treatment cells were washed in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then incubated in permeabilizing solution (0.2% Triton-X 100 in PBS) for 5 min, washed with PBS and blocked in 2% BSA for 30 min. Primary antibody, either goat anti-rabbit-p65 (1:100) or goat anti-rabbit-IκBα (1:100) in 1% BSA, was added to the cells and cells incubated overnight at 4°C. After extensive washing in PBS, cells were incubated in the secondary antibody solution comprising goat-anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 1:500 in PBS) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The cells on cover glasses were washed and mounted with mounting medium containing propidium iodine (Vectashield). Stained cells were analyzed using a fluorescent microscope and pictures were taken with 40× magnification.

Transfection and reporter assays

The CYP24-Luc construct was a generous gift from Dr. Tai Cheng (Boston University Medical Campus, Core Lab Director), and has been used previously by us (Zbytek et al., 2008). We sequenced the construct using forward primer (5′-CTAGCAAAATAGGCTGTCCC-3′) and reverse primer (5′ CTTTATGTTTTT GGCG TCTTCCA-3′). It contained four VDREs (marked bold) situated upstream of the CYP24 gene. Underlined sequence has two separated VDREs (GGATATTGGAAGGCG and ATTGGAAGGCGGACA). The sequences showed perfect match with the part (148–1,045) of rat P450cc24 (Pubmed ID, D17792; (Ohyama et al., 1991, 1993, 1994).

The sequence of the insert is as follows:

GAGCTCTGTTCTATCCGGCCGCAAAAGCAGGAG-TGCGACTGTGGATAACCCTGCCTGCTTTAGGTGGG-CTTTAGGGAGAAAGTGGGGCGCTTGGGAAGCTGT-GCGTGCCTCTGCTCTGTGCAGGGTGGGCGGTGC-GCAAGAAGGAAAGGCCCGAGGGACCTGTGGGAAA-CAGTCTAAAGGAAACTGAGCTATGCCCTGTAGGC-ATTGCACAGTCTCCTGAAGAACTAAGGCCACTAG-TATCCTTTATTGAGGACACACACCTGTGTAGACCTT-ACATGCGTTCATTTATTCGATTCCCTAACAAGTCAA-CCCGAAGCATCGAGGAATCTGGTAAGGAAATTCTG-CAAACCGCATTGGGCTTTCTTGCCTAATTTAAGA-CCCAAGGTAAGAAGATTATTTCCTCTCCCCCTCCCC-TCTTTTTGGTATAGCCTAGTAAGTTTCAAGTCCTCT-CTTCCTTCAGAAGCTCAAAAAGGCAACTTTCATCC-AAGGGAAGTCTGGCTCAGGCTGCGAAAACCTGTCT-CCCAGGATATTGGAAGGCGGACACTCTCCACTT-GCTTGGCAAGCGCGGGCGGCCTTCCGCGCTGTCCT-CAGGGACCTTGCCCGCCCTGCATGGCGATTGTGC-AAGCGCAGCTTTGGGCTCCTGCAAGGCCAGCTGCA-GCCTGCAGGAGGAGGGCGAGGAGGCGTGCTCGC-AGCGCACCCGCTGAACCCTGGGCTCGACCCGCC-TTTCTCAGGTTATCTCCGGGGTGGAGTCCACCG-GTGCGTCTGCCGGGCCAGCAGCGTGTCGGTCA-CCGAGGCCCCGGCGCCCTCACTCACCTCGCTGAC-TCCATCCTCTTCCCACACCCGCCCCCCGCGTCCC-TCCCAGCCGGTCCCCCTCCGCCCTGCTCAGCGTG-CTCATTGG.

The hVDR construct was a generous gift from Dr D. Bikle (University of California, San Francisco, CA). The pLuc and NF-κB-Luc constructs have been described previously (Zbytek et al., 2003, 2004, 2006). HaCaT keratinocytes were transfected with NF-κB-Luc, CYP-24-Luc and hVDR constructs using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) in DMEM medium with firefly luciferase reporter gene plasmid and with phRL-TK (which expresses Renilla luciferase and serves as normalization control; Promega, Madison, WI). Normal epidermal keratinocytes were transfected with the NF-κB-Luc construct using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) in KGM medium, along with firefly luciferase reporter gene plasmid and with phRL-TK. After transfection cells were incubated for 24 h in complete medium; fresh complete medium added and cells treated with test compounds or ethanol vehicle for another 24 h. The firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase signals were recorded with a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA); background luminescence was subtracted and the resulting promoter specific firefly signal was divided by the Renilla signal (proportional to the number of transfected cells). The values obtained were divided by the mean value for control (untreated) cells.

siRNA transfection

HaCaT keratinocytes were transfected with 20 nM VDR or scrambled siRNA (Dharmacon), on-Target plus smart pool human VDR or on-Target plus siControl non-targeting pool, using lipofectamine plus (Invitrogen) in DMEM medium, as described previously (Zbytek et al., 2008). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated for an additional 24 h with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 (as listed) or ethanol vehicle, then mRNA was isolated and used for gene expression analysis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay for NF-κB activation

HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with 0.1 μM 20,23(OH)2D3 for either 0 h, 30 min, 1 h, 4 h, 16 h, or 24 h. The cells were collected with trypsin/EDTA, washed with 1× PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of 0.2% Triton-X 100 in STM buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, 250 mM sucrose, and 1.1 mM MgCl2. The cell suspension was vortexed and incubated on ice for 10 min followed by 15 sec centrifugation at 4°C. This procedure was repeated twice. Cell pellets were then resuspended in 1 ml STM buffer and centrifuged for 15 sec. This step was also repeated twice. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 30 μl nuclear extraction buffer containing 0.4 M KCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and protease inhibitors cocktail (1:100 dilution, Sigma) in STM buffer, incubated on ice for 30 min with shaking and then centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 min at 4°C. Protein in the supernatant was measured using the Bradford protein procedure (Pavicevic et al., 2008).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were done using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Inc., Lincoln, NE) with NF-κB IRDye-labeled oligonucleotide (LI-COR). The DNA binding reaction was set up using 2.5 μg of the nuclear extract mixed with oligonucleotide and gel shift binding buffer consisting of 2.5 mmol/L DTT, 0.25% Tween-20 and 0.25 mg/ml poly(dI):poly(dC). The reaction was carried out at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. Orange loading dye (2 μl of 10× stock) was added to each sample which was then loaded on a prerun 5% TBE gel and run at 80 V for 1.5 h. The gel was scanned using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System.

Western blot

HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with 0.1 μM 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 for times of: 0 h, 30 min, 1 h, 4 h, 16 h, or 24 h. Cells were lysed and whole cell extract was prepared as described previously (Hanissian et al., 2004; Hanissian et al., 2005). Equal amounts of protein for each sample, determined using the Bradford method, were subjected to electrophoresis using an SDS–PAGE gel (7–15% gradient) then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA). The primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal antibodies of anti-IκB-α (Santa Cruz, USA), 1:250 dilution; anti-IκB-β (Santa Cruz), 1:250 dilution; anti-p65 (Santa Cruz), 1:500 dilution or anti-β actin-peroxidase (Sigma), 1:5,000 dilution. The secondary antibody used was anti rabbit –HRP (Santa Cruz), 1:7,000 dilution.

Levels of VDR and β-actin proteins were assessed 24 h after VDR siRNA transfection by Western blots with VDR(D6) antibody (Santa Cruz, 1:400) or anti-β actin-peroxidase (Sigma), 1:5,000 dilution.

Real-time RT PCR

The RNA from HaCaT or HEKn keratinocytes treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3, was isolated using the Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Stratagen). Reverse transcription (100 ng RNA/reaction) was performed using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Germany). Real-time PCR was performed using cDNA diluted 10-fold in sterile water and a TaqMan PCR Master Mix. Reactions (in triplicate) were performed at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min and then 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec. The primers and probes were designed with the universal probe library (Roche). Data were collected on a Roche Light Cycler 480. The amount of amplified product for each gene was compared to that for Cyclophilin B using a comparative CT method. A list of the primers used for RT-PCR DNA amplification is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR DNA amplification

| Gene | Primer sequence (left and right) |

|---|---|

| CYCLOPHILIN B1 | L: 5′-TGTGGTGTTTGGCAAAGTTC-3′ |

| R: 5′-GTTTATCCCGGCTGTCTGTC-3′ | |

| VDR | L: 5′-CTTACCTGCCCCCTGCTC-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGGGTCAGGCAGGGAAGT-3′ | |

| INVOLUCRIN | L: 5′-TGCCTCAGCCTTACTGTGAGT-3′ |

| R: 5′-TCATTTGCTCCTGATGGGTA-3′ | |

| CK14 | L: 5′-TTGAGGACCTGAGGAACAAGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-GACGGGCATTGTCAATCTG-3′ | |

| CYP24 | L: 5′-CATCATGGCCATCAAAACAAT-3′ |

| R: 5′-GCAGCTCGACTGGAGTGAC-3′ | |

| CYP27B1 | L: 5′-CTTGCGGACTGCTCACTG-3′ |

| R: 5′-CGCAGACTACGTTGTTCAGG-3′ | |

| IκBα | L: 5′-GTCAAGGAGCTGCAGGAGAT-3′ |

| R: 5′-GATGGCCAAGTGCAGGAA-3′ | |

| NF-κB1 | L: 5′-ACCCTGACCTTGCCTATTTG-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGCTCTTTTTCCCGATCTCC-3′ | |

| RelA | L: 5′-CGGGATGGCTTCTATGAGG-3′ |

| R: 5′-CTCCAGGTCCCGCTTCTT-3′ |

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–4), and were analyzed with a Student’s t-test (for two groups) or ANOVA using Prism 4.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistically significant differences are denoted with asterisks: *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.005.

Results

20,23(OH)2D3 inhibits proliferation of keratinocytes and arrests them at G0/G1 and G2/M phases of the cell cycle

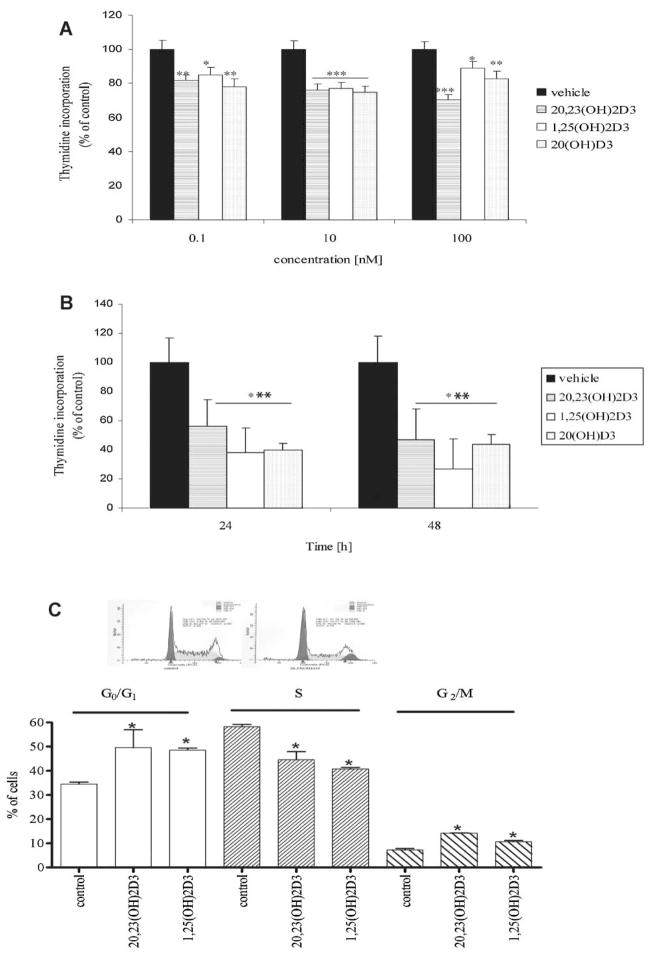

Treatment of HaCaT keratinocytes with 20,23(OH)2D3 for 48 h (Fig. 1A) led to the suppression of [3H]-thymidine incorporation into DNA in a concentration dependent manner when compared to control cells. As shown in Figure 1A, treatment of keratinocytes with 0.1–10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 led to a decrease in DNA synthesis by 30% and with 100 nM the decrease was close to 60%. A similar decrease in DNA synthesis was observed for cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 or 20(OH)D3 (Fig. 1A). Additional experiments have shown that when cells were treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 DNA synthesis decreased by 40% after 24 h, and by 55% after 48 h (Fig. 1B). This inhibitory effect of 20,23(OH)2D3 on DNA synthesis was comparable to that for 1,25(OH)2D3 or 20(OH)D3 (Fig. 1B). To better define the nature of this inhibition, HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with 10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 h and than analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1C). Treatment with 20,23(OH)2D3 resulted in similar changes in the distribution of cells in different cell cycle phases to those seen with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 1C). Control cells were distributed as follows: 34.5 ± 1.9% in G1/G0, 58 ± 2.4% in S and 7 ± 1.4% in G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Treatment of cells with 20,23(OH)2D3 resulted in significant G1/G0 (49.6 ± 12.7%) and G2/M (14.21 ± 0.5%) arrests. These effects were similar to those exerted by 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3, leading to significant changes to the distribution of cells in the different phases of the cell cycle: 48.64 ± 1.4% in G1/G0 and 10.61 ± 0.9% in G2/M phase.

Fig. 1.

20,23(OH)2D3 inhibits proliferation and arrests keratinocytes at G0/G1 and G2/M phases of the cell cycle. HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3or 20(OH)D3 for 48 h, at concentrations ranging from 0.1to 100 nM (A) orat a 100 nM concentration at different time points (24 h and 48 h) (B), and [3H]-thymidine incorporation into the DNA of cells was measured. Differences to control (ethanol treated cells) and between every dose are significant(*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). HaCaTcells were also treated with 10 nM 20,23 (OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 h, cells harvested, fixed, stained with PI and read with a flow cytometer (C). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.05 between control and treatment).

20,23(OH)2D3 stimulates differentiation

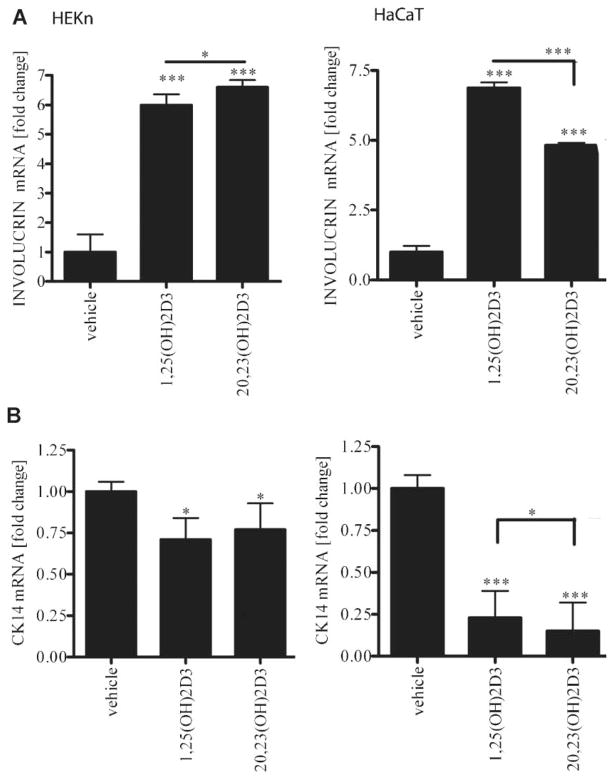

Previously it has been reported that both 1,25(OH)2D3 and P450scc-derived 20(OH)D3 can stimulate differentiation of keratinocytes (Bikle, 2004b; Zbytek et al., 2008) In this study we compared the action of 20,23(OH)2D3 with that of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the expression of involucrin and cytokeratin 14 genes, markers of epidermal keratinocyte differentiation. Cells were treated with 100 nM dihydroxyvitamin D3 compounds for 6 h. Treatment of cells with 20,23(OH)2D3 stimulated expression of the involucrin gene 6.5-fold in HEKn keratinocytes and 5-fold in HaCaT cells, similar to the effects seen for 1,25(OH)2D3 where the increase was sixfold in HEKn cells and sevenfold for HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 2A). Treatment of cells with 20,23(OH)2D3 caused a slight but significant inhibition of cytokeratin 14 gene expression in HEKn cells, similar to the effect observed with 1,25(OH)2D3, whereas a 75% decrease in cytokeratin 14 expression was observed in HaCaT keratinocyes (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

20,23(OH)2D3 stimulates keratinocytes differentiation on mRNA level. HEKn or HaCaT cells were treated for 6 h with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol as a vehicle. The mRNA was isolated and RTPCR performed using specific primers for involucrin (A) and CK14 genes (B). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

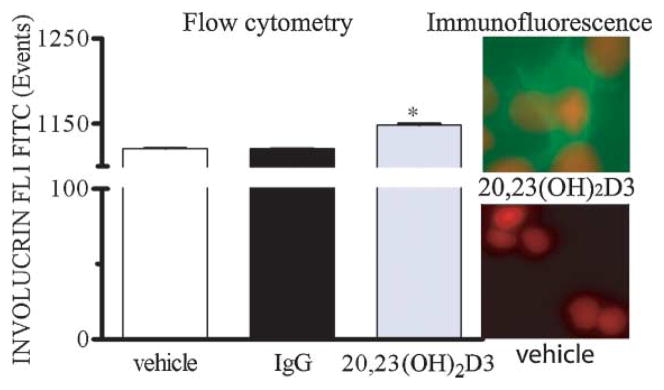

To examine whether the changes in gene expression measured at the level of mRNA correlated with changes in protein expression, involucrin protein was examined by flow cytometry and immunofluorescent microscopy. HaCaT keratinocytes treated with 10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 for 24 h showed increased expression of involucrin protein (Fig. 3). Moreover, we measured the effects of 20,23(OH)2D3 on forward and side scatter of light, parameters that reflect cell size and granularity, respectively. Both parameters are known to increase during keratinocyte differentiation. As shown in Table 2, 20,23(OH)2D3 significantly increased both forward and side scatter by HaCaT keratinocytes. 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly influenced only forward scatter.

Fig. 3.

20,23(OH)2D3 stimulates keratinocytes differentiation on protein level. HaCaT cells were treated with 10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 or ethanol as a vehicle for 24 h. The cells were harvested, fixed in 2% PFA, stained with anti-involucrin antibody and read with a flow cytometer. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.05 between control and treatment). IgG is used as a control. For immunofluorescent analysis, HaCaT cells were plated onto cover glass in 6-well plates and treated for 24 h with 10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 or ethanol, fixed, stained with anti-involucrin antibody (green) and nuclei with PI (red). Cells were photographed with a fluorescent microscope using 40× magnification.

TABLE 2.

20,23(OH)2D3 increases size and granularity of HaCaT keratinocytes

| Treatment | Forward scatter (mean signal intensity) | Side scatter (mean signal intensity) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 2014.43 ± 6.76 | 2143.6 ± 21 |

| 20,23(OH)2D3 | 2128.00 ± 17.32** | 2154.41 ± 30.22* |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 2122.12 ± 23.98** | 2110.12 ± 44.25 |

P <0.05.

P <0.01.

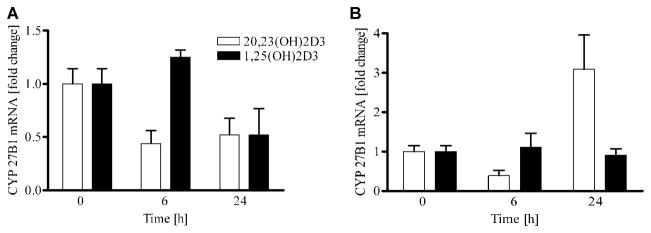

20,23(OH)2D3 does not inhibit expression of CYP27B1 or 27A1

Since CYP27B1 and CYP27A1 gene expression is inhibited by 1,25(OH)2D3 in the kidney and liver, respectively (Feldman et al., 2005), we compared the action of 20,23(OH)2D3 with that of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the expression of these genes in HaCaT and normal epidermal keratinocytes. As shown in Figure 4, 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 did not significantly alter the expression of CYP27B1 in either HEKn keratinocytes (Fig. 4A) or HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 4B). While both, 20,23(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 appeared to cause some variation in the levels of CYP27B1 gene expression tested after 6 and 24 h, these changes were not statistically different from non-treated cells.

Fig. 4.

20,23(OH)2D3 does not inhibit expression of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1 α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) in keratinocytes. HEKn (A) or HaCaT (B) keratinocytes were treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 or1,25(OH)2D3 at a100 nM concentration for 0, 6, and 24 h. Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed. CYP27B1 mRNA levels were measured according to manufacturer’s protocol (Roche). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

There was no effect of 20,23(OH)2D3 on CYP27A1 expression (data not shown).

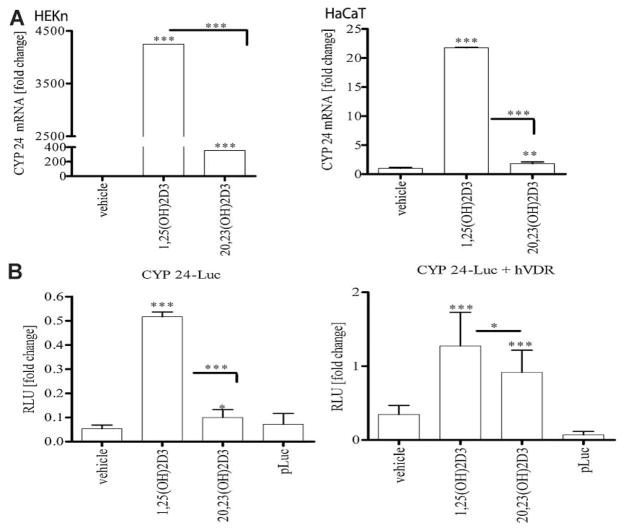

20,23(OH)2D3 is a less potent stimulator of CYP24 gene expression than 1,25(OH)2D3

Since the CYP24 gene is an important physiological target of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the kidney and peripheral tissues, including skin (Feldman et al., 2005), we compared the action of 20,23(OH)2D3 with that of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the expression of this gene in keratinocytes. Cells treated with 10 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 h showed enhanced expression of CYP24 as measured by RTPCR (Fig. 5A). Treatment of cells with 20,23(OH)2D3 stimulated expression of CYP24 approximately 400-fold in HEKn but only 2- to 3-fold in HaCaT keratinocyes when compared to control cells. In contrast, 1,25(OH)2D3 increased CYP24 expression 11 times more than 20,23(OH)2D3 in HEKn and 20 times more in HaCaT keratinocytes.

Fig. 5.

20,23(OH)2D3 is less potent at stimulating CYP24 gene expression in keratinocytes than 1,25(OH)2D3. A: HEKn and HaCaT cells were treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol as a vehicle for 24 h, mRNA was isolated and submitted for RTPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD(n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). B:HaCaT cells were transfected with luciferase constructs: CYP24 alone or with human VDR receptor and empty vector pLuc, using lipofectamine. 24 h post-transfection cells were treated with 10 nM, 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol as a vehicle for 24 h. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured with a luminometer. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

We further tested the biological activity of 20,23(OH)2D3 on the transcriptional activity of the CYP24 gene promoter in HaCaT and normal epidermal keratinocytes. HaCaT cells were transfected with either a luciferase reporter construct driven by the CYP24 promoter or a promoterless luciferase construct. As shown in Figure 5B, 20,23(OH)2D3 did not affect activity of the promoterless (pLuc) construct. However, it weakly but significantly stimulated the CYP24 promoter which is in contrast to the strong stimulation observed with 1,25(OH)2D3. Increasing levels of the VDR by co-transfection with plasmid encoding human VDR increased the stimulatory effect of 20,23(OH)2D3 on CYP24.

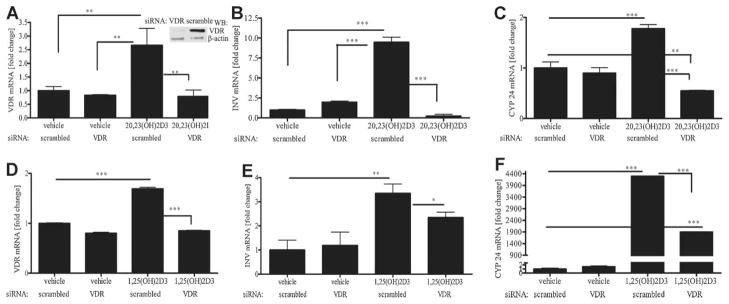

20,23(OH)2D3 requires VDR for its action on keratinocytes

To test the involvement of VDR in the action of 20,23(OH)2D3, keratinocytes were transfected with scrambled or VDR small interfering RNA (siRNA). Cells were treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol as a vehicle control for 24 h then mRNA levels for VDR, involucrin and CYP24 were measured. VDR siRNA caused almost complete disappearance of VDR expression at the mRNA level 24 h after transfection, as revealed by comparing the vehicle-control treated cells containing siRNA to the cells transfected with scrambled siRNA when treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6A) or 1,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6D). Disappearance of VDR at the protein level was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 6A, insert) as we have observed in other studies using this procedure (Zbytek et al., 2008; Janjetovic et al., 2009). Transfection of keratinocytes with VDR siRNA had no effect on the basal VDR mRNA levels (Fig. 6A, D). Treatment of cells transfected with scrambled siRNA with 20,23(OH)2D3 resulted in a significant increase in mRNA for involucrin (Fig. 6B), an effect also seen with 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (Fig. 6E). This stimulation of invrolucrin mRNA by 20,23(OH)2D3 was abolished in cells transfected with VDR siRNA. Similar results were observed for expression of CYP24, where the CYP24 mRNA levels were significantly lower for cells transfected with VDR siRNA compared to cells transfected with scrambled siRNA after treatment with 20,23(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6C). Treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in much higher expression of the CYP 24 gene which was significantly decreased after silencing VDR (Fig. 6F). These results support a role for VDR in the phenotypic effects induced by 20,23(OH)2D3 as occurs for 1,25(OH)2D3.

Fig. 6.

20,23(OH)2D3 requires VDR for its action on keratinocytes. HaCaT keratinocytes were transfected with 20 nM scrambled or VDR small interfering RNA (siRNA). Cells were incubated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 (A–C) or 1,25(OH)2D3 (D–F) or the vehicle control for 24 h. mRNA levels were measured for VDR (A, D), involucrin (B, E), and CYP24 (C, F), using reagents for RTPCR according to manufacturer’s protocol (Roche Applied Science, Manheim, Germany) and normalized relative to Cyclophilin B mRNA. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control). Levels of VDR and β-actin proteins were assessed 24 h after transfection with VDR or scrambled siRNA by Western blotting of whole cell extracts (A).

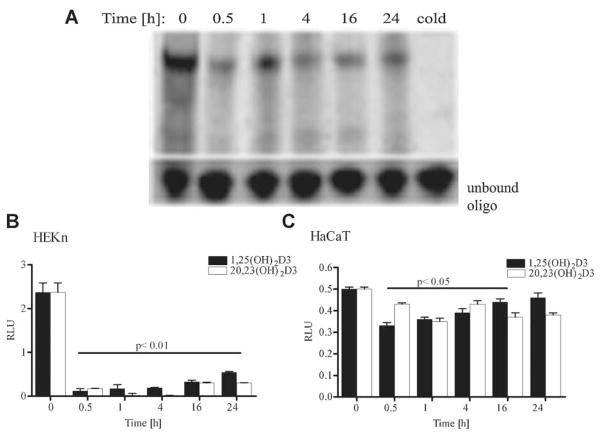

20,23(OH)2D3 attenuates NF-κB binding activity

Since 1,25(OH)2D3 has anti-inflammatory activity which is mediated by inhibition of NF-κB activity (Cohen-Lahav et al., 2007), the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB in HaCaT keratinocytes treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 was measured by EMSA (Fig. 7A). Nuclear extracts from HaCaT cells treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 were incubated with an NF-κB oligonucleotide probe based on the κB binding site in the immunoglobulin light chain enhancer, and subjected to electrophoresis. A decrease in nuclear protein binding to the κB response element was observed for extracts of 20,23(OH)2D3 -treated cells relative to control (vehicle-treated) cells (Fig. 7A). Inhibition of NF-κB activity was observed within 30 min after addition of 20,23(OH)2D3. Maximum inhibition was reached by 4 h, and inhibition persisted up to 24 h. A similar inhibition of NF-κB activity was observed in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Cohen-Lahav et al., 2006) and 20(OH)D3 (Janjetovic, 2009). High basal NF-κB activity in HaCaT cells is probably due to serum deprivation of cells as we have previously demonstrated that serum deprivation triggers NF-κB activation in HaCaT cells (Zbytek et al., 2003).

Fig. 7.

20,23(OH)2D3 attenuates NF-κB binding activity in HaCaT cells. A: Nuclear extracts were prepared from HaCaT cells treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 for 0 h (vehicle control), or times indicated, and subjected to an electrophoresis mobility shift assay using 2.5 μg of proteins per lane. “Cold” represents extract incubated with an excess of unlabeled NF-κB oligonucleotide. Normal keratinocytes (B) and HaCaT (C) were transfected with the NF-κB luciferase construct (NF-κB-Luc) using lipofectamine. 24 h post-transfection cells were treated for the indicated periods with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 (or ethanol vehicle). Cells were then lysed and luciferase activity was measured with a luminometer. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4).

In order to determine functional consequences of the decreased NF-κB DNA binding activity in the keratinocytes treated with 20,23(OH)2D3, we performed gene reporter assays to determine NF-κB driven transcriptional activity (Fig. 7B). HaCaT and normal human keratinocytes were transiently transfected with the pNFκB-Luc construct which contained the firefly luciferase reporter gene driven by NF-κB. In the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 or 20,23(OH)2D3, basal luciferase activity decreased. The inhibitory effect was more pronounced in normal human keratinocytes, with approximately a 2.5-fold decrease in the reporter activity (P <0.01) (Fig. 7B). In immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaT) the decrease in activity was less pronounced, but was still statistically significant (P <0.05) (Fig. 7C). 20,23(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited NF-κB driven reporter activity in keratinocytes in similar manner. Interestingly, NF-κB activity was significantly inhibited even after 24 h of treatment with either agent. Thus, despite the cell-type differences in magnitude, both 20,23(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibit NF-κB-dependent transcription, the latter response for 1,25(OH)2D3 being consistent with literature (Cohen-Lahav et al., 2006).

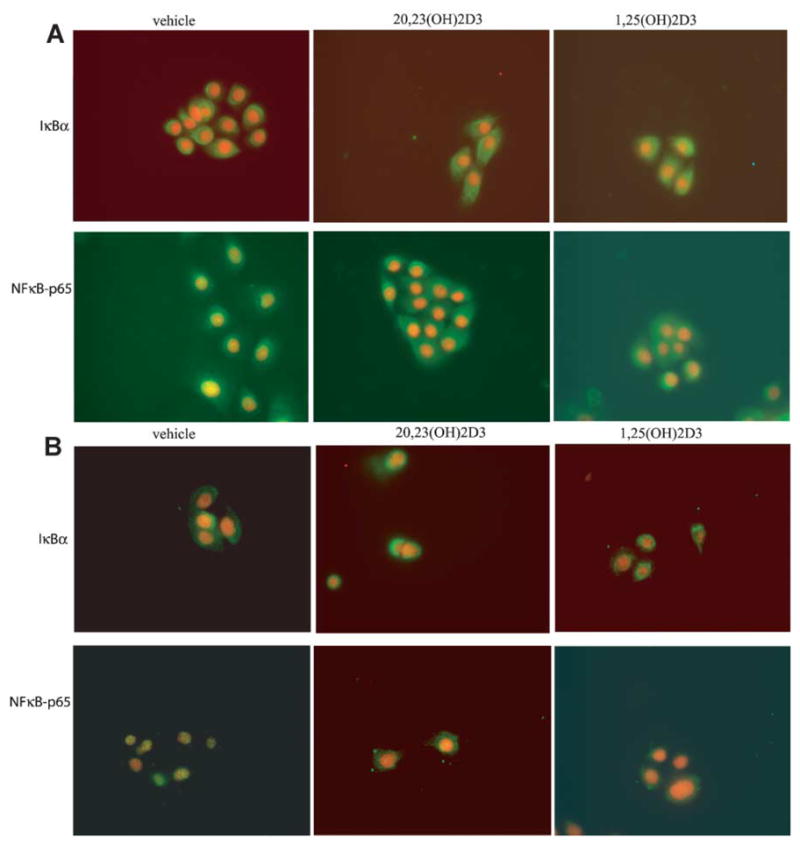

20,23(OH)2D3 inhibits translocation of the p65 NF-κB protein in keratinocytes

To further characterize the inhibitory effect of 20,23(OH)2D3 on NF-κB activity, we examined the cellular localization of the p65 NF-κB protein and IκBα in keratinocytes by fluorescent microscopy. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is usually localized mainly in the cytoplasm with only minor nuclear staining detected (Fig. 8A). Stimulation of normal keratinocytes by IL-1α induced p65 translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, indicative of the NF-κB activation (Fig. 8B). In contrast, treatment of cells with 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 almost completely blocked the nuclear translocation of p65, both before or after stimulation with IL-1α (Fig. 8A, B). In addition, there was a noticeable increase in IκBα protein localized in the cytoplasm after treatment with 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 in comparison to vehicle-treated cells without or after treatment with IL-1α (Fig. 8A, B). Similar results were obtained when HaCaT and normal keratinocytes were treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 for 1, 4, or 24 h (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

20,23(OH)2D3 inhibits translocation of NF-κ B-p65 proteinin keratinocytes. Primary human keratinocytes, third passage, were incubated for 4 h in KBM medium containing KGF and 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol as a vehicle, and additionally treated without (A) or with IL-1α (B) for 30 min and then fixed. Cells were stained with anti IκBα or NF-κB-p65 antibody followed by secondary antibody linked to FITC. Nuclei were stained red with PI. Cells were photographed using a fluorescent microscope at 40× magnification.

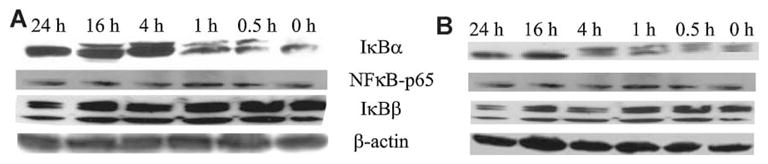

20,23(OH)2D3 increases IκBα protein levels

Since our results clearly show that that 20,23(OH)2D3 inhibits NF-κB activity, we looked at the mechanism underlying this process. In the classical NF-κB pathway, NF-κB activity is tightly controlled by inhibitory IκB proteins, which bind to NF-κB and sequester it in the cytoplasm. To determine whether 20,23(OH)2D3 affects the classical NF-κB pathway, the cellular levels of IκBα, IκBβ and the p65 NF-κB were determined by immunofluorescent staining at various times after 20,23(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 (serving as a positive control) addition to cells. Both, 20,23(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 also induced a time-dependent increase in IκBα levels in whole cell extracts of HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 9). IκBα was increased within 1 h of 20,23(OH)2D3 treatment, but by 24 h IκBα was diminishing (Fig. 9A). In contrast, cellular levels of p65 and IκBβ were unaffected by 20,23(OH)2D3 treatment of keratinocytes. Similar results were obtained when cells were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 9B). Protein levels were compared to β-actin as a loading control.

Fig. 9.

20,23(OH)2D3 increases IκBα protein levels in keratinocytes. HaCaT keratinocytes were stimulated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3 (A) or 1,25(OH)2D3 (B) for the indicated times. Cells were lysed and whole cell extracts prepared. An equal amount of protein for each cell treatment was loaded onto the polyacrylamide gel. Membranes were incubated with antibodies: anti-IκBα, anti-NF-κB-p65, anti-IκBβ and anti-β-actin (internal control).

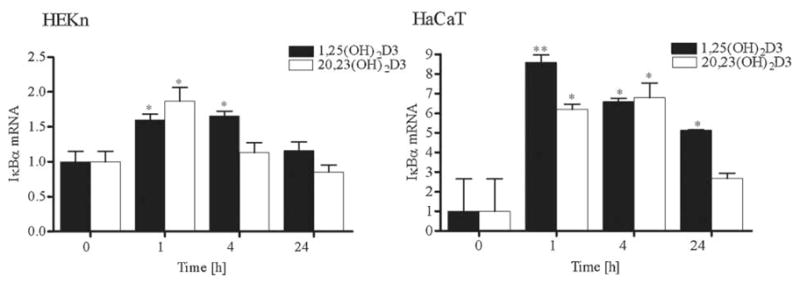

20,23(OH)2D3 stimulates IκBα mRNA expression, but does not affect NF-κB mRNA expression

To determine whether the increased IκBα protein levels in cells treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 results from increased IκBα mRNA expression, we measured IκB mRNA levels by quantitative real time PCR (qPCR). As shown in Figure 10 the IκBα-mRNA levels were significantly increased after 20,23(OH)2D3 treatment of HaCaT and normal human keratinocytes. The induction by 20,23(OH)2D3 of IκBα mRNA expression was greater in HaCaT cells than in normal keratinocytes. The stimulation was seen 1 h after treatment and returned to basal levels by 4 h in normal keratinocytes, while the induction of IκBα mRNA persisted up to 24 h in HaCaT cells. Moreover, the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on IκBα mRNA levels were qualitatively similar to those noted for 20,23(OH)2D3, although somewhat stronger and longer lasting. In contrast, mRNA levels of the p50 and p65 NF-κB subunits were unaffected by treatment with either 1,25(OH)2D3 or 20,23(OH)2D3 (data not shown).

Fig. 10.

20,23(OH)2D3 stimulates IκBα mRNA expression. HEKn and HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with 100 nM 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle for the indicated period of time. Cells were then lysed and total RNA extracted. mRNA levels for IκBα were measured by quantitative RTPCR and normalized relative to Cyclophilin B mRNA. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3) (*P < 0.05 vs. control, or **P < 0.01 vs. control).

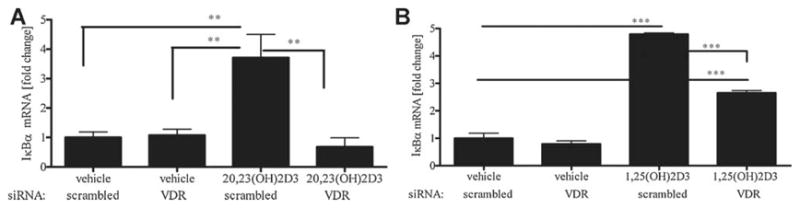

20,23(OH)2D3 requires VDR expression for its action on the NF-κB pathway

We already demonstrated that the action of 20,23(OH)2D3 on proliferation and differentiation of human keratinocytes is dependent on VDR expression (Fig. 6). Therefore, we examined whether the effect of 20,23(OH)2D3 on the NF-κB pathway was also dependent on VDR expression. Human keratinocytes were transiently transfected with siRNA to knockdown the VDR, treated with 20,23(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol vehicle and RNA isolated for gene expression analysis by qPCR. As shown in Figure 11, knockdown of the VDR receptor in keratinocytes completely blocked IκBα mRNA induction by 20,23(OH)2D3 (Fig. 11A) or 1,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 11B). In contrast, 20,23(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment induced an increase in IκBα mRNA in cells transfected with scrambled siRNA. The mRNA levels for p50 and p65 NF-κB proteins were unaffected by VDR knockdown (data not shown). Similar results have been obtained for the precursor to 20,23(OH)2D3, 20(OH)D3 as we have just reported recently (Janjetovic, 2009).

Fig. 11.

20,23(OH)2D3 requires VDR expression for its action on the NF- κB pathway in keratinocytes. HaCaT keratinocytes were transfected with 20 nM scrambled or VDR siRNA and incubated with 100 nM20,23(OH)2D3 (A), 1,25(OH)2D3 (B) or vehicle (ethanol) for 4 h, cells lysed and total RNA extracted. I κBα mRNA levels were measured by quantitative RTPCR and normalized relative to Cyclophilin B mRNA. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control).

Discussion

In continuation of our studies on the biological role of a novel secosteroidogenic pathway (Slominski et al., 2004, 2005b, 2009), we show that 20,23(OH)2D3, an intermediate product of P450scc metabolism of vitamin D3 (Tuckey et al., 2008a), inhibits proliferation and stimulates differentiation of keratinocytes, inhibits NF-κB activity and affects expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in vitamin D metabolism. The current study shows that 20,23(OH)2D3 acts similarly to 1,25(OH)2D3 (the hormonally active form of vitamin D3 that induces the keratinocyte differentiation program (Bikle, 2004b)), and also to 20(OH)D3 (Zbytek et al., 2008) as regards to both potency and effects on proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes. Both P450scc-generated compounds inhibited keratinocyte growth, as shown by reduced thymidine incorporation into DNA, and growth arrest in the G0/G1 and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, and stimulated differentiation as documented by an increase in involucrin gene and protein expression, increase in cell size and granularity and a decrease in cytokeratin 14 mRNA.

Since expression of CYP27A1 and CYP27B1 genes (encoding for 25- and 1-hydroxylase of vitamin D3, respectively) is inhibited by 1,25(OH)2D3 in the kidney and liver (Feldman et al., 2005), we compared the effects of 20,23(OH)2D3 to those of 1,25(OH)2D3. We found that 20,23(OH)2D3 has no significant effect on CYP27A1 and CYP27B1 expression, as reported for 1,25(OH)2D3 (Bar et al., 2007). The gene for CYP24 is a well-characterized target of 1,25(OH)2D3 action and CYP24 inactivates 1,25(OH)2D3 by hydroxylating it at C24 (Holick, 2003, 2006; Feldman et al., 2005; Lehmann, 2005; Bikle, 2006). While 20,23(OH)2D3 stimulated CYP24 gene expression it had a much lower potency than 1,25(OH)2D3. This was confirmed by testing the transcriptional activity of the CYP24 promoter where 20,23(OH)2D3 had significantly lower effect than 1,25(OH)2D3. This indicates that 20,23(OH)2D3 may act as a partial receptor agonist, not causing the full range of effects seen with 1,25(OH)2D3. This is further supported by our data that show that VDR is required for the actions of 20,23(OH)2D3. Nevertheless, the stimulation of mRNA levels for CYP24, involucrin and IκBα by 20,23(OH)2D3 was reduced by siRNA for the VDR, indicating that its phenotypic effects are induced by activation of the VDR. 20,23(OH)2D3 is thus a worthy compound for future testing of its ability to raise serum calcium levels. Partial receptor agonists which display diminished ability to stimulate calcium absorption, but that inhibit proliferation, are of interest as therapeutic agents to use for hyperproliferative diseases, including cancer (Grando et al., 1996; Elias et al., 2002; Masuda and Jones, 2006; Spina et al., 2006, 2007). While the metabolism of 20,23(OH)2D3 by CYP24 remains to be investigated, the relatively small stimulation of expression of CYP24 by this compound compared to 1,25(OH)2D3 may prolong its physiological actions in vivo and have minimal effects on the rate of inactivation of 1,25(OH)2D3 at biologically active concentrations.

Being familiar with the anti-inflammatory action of 1,25(OH)2D3 (Cohen-Lahav et al., 2006, 2007) and most recently with 20(OH)D3 activity (Janjetovic, 2009) in attenuating NF-κB, we compared the action of 20,23(OH)2D3 to that of 1,25(OH)2D3 on NF-κB activity. NF-κB is a major regulator of the inflammatory processes (Li et al., 2001; Li and Verma, 2002) as well as a modifier of cancerogenic properties (Umezawa, 2006; Van Waes, 2007; Liu et al., 2008). Phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB proteins allow for the release of NF-κB and then its translocation to the nucleus, where it can bind to the transcription-regulatory sequences to activate specific genes (Li and Verma, 2002). NF-κB plays an important role in protecting keratinocytes against apoptosis when cells undergo programmed cornification (Lippens et al., 2005). It has been shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 can reduce NF-κB DNA binding activity by increasing IκBα protein levels in human keratinocytes (Riis et al., 2004) as well as in murine macrophages (Cohen-Lahav et al., 2006, 2007) and fibroblasts (Sun et al., 2006).

This study shows that 20,23(OH)2D3 inhibits NF-κB activity in keratinocytes. It caused a reduction in NF-κB in DNA-binding complexes and reduced the expression of the luciferase signal driven by the NF-κB promoter in transfected keratinocytes. It also increased the expression of IκBα at both mRNA and protein levels and inhibited NF-κB translocation from cytoplasm to the nucleus. In contrast, 20,23(OH)2D3 had no effect on mRNA or protein levels of NF-κB p65 (RelA) or NF-κB p50. As already mentioned, 20,23(OH)2D3 requires VDR for its action on NF-κB activity. An increase in IκBα mRNA levels upon treatment with 20,23(OH)2D3 was totally blocked by silencing of the VDR gene. Thus 20,23(OH)2D3 acts in a similar manner to 1,25(OH)2D3 in inhibiting NF-κB activity by increasing IκBα concentrations, and sequestering NF-κB in the cytoplasm.

In conclusion, effects of 20,23(OH)2D3 on cell proliferation, differentiation and NF-κB activity in keratinocytes make this compound of potential therapeutic use for hyperproliferative and inflammatory skin diseases. The current documentation of these effects should also be of physiological importance since 20,23(OH)2D3 could be generated under in vivo conditions by the action of P450scc system (Slominski et al., 2004; Tuckey et al., 2008b).

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: NIH;

Contract grant number: R01AR052190.

The work was supported by NIH grant R01AR052190. We thank Dr. Tai Chen from Boston University for providing the Cyp24-LUC construct and Dr. Tae-Kang Kim for sequencing it. We also thank Dr. D. Bikle for the hVDR plasmid.

Literature Cited

- Bar M, Domaschke D, Meye A, Lehmann B, Meurer M. Wavelength-dependent induction of CYP24A1-mRNA after UVB-triggered calcitriol synthesis in cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:206–213. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle DD. Vitamin D and skin cancer. J Nutr. 2004a;134:3472S–3478S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3472S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle DD. Vitamin D regulated keratinocyte differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2004b;92:436–444. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle DD. Vitamin D: Production, metabolism and mechanism of action. 2006 www.endotext.com.

- Bikle DD, Nemanic MK, Gee E, Elias P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 production by human keratinocytes. Kinetics and regulation. J Clin Invest. 1986a;78:557–566. doi: 10.1172/JCI112609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle DD, Nemanic MK, Whitney JO, Elias PW. Neonatal human foreskin keratinocytes produce 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Biochemistry. 1986b;25:1545–1548. doi: 10.1021/bi00355a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlberg C. Molecular basis of the selective activity of vitamin D analogues. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:274–281. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Lahav M, Shany S, Tobvin D, Chaimovitz C, Douvdevani A. Vitamin D decreases NFkappaB activity by increasing IkappaBalpha levels. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:889–897. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Lahav M, Douvdevani A, Chaimovitz C, Shany S. The anti-inflammatory activity of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in macrophages. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias PM, Ahn SK, Denda M, Brown BE, Crumrine D, Kimutai LK, Komuves L, Lee SH, Feingold KR. Modulations in epidermal calcium regulate the expression of differentiation-specific markers. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1128–1136. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux FH. Vitamin D. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. p. 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Grando SA, Horton RM, Mauro TM, Kist DA, Lee TX, Dahl MV. Activation of keratinocyte nicotinic cholinergic receptors stimulates calcium influx and enhances cell differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:412–418. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12363399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guryev O, Carvalho RA, Usanov S, Gilep A, Estabrook RW. A pathway for the metabolism of vitamin D3: Unique hydroxylated metabolites formed during catalysis with cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14754–14759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336107100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanissian SH, Akbar U, Teng B, Janjetovic Z, Hoffmann A, Hitzler JK, Iscove N, Hamre K, Du X, Tong Y, Mukatira S, Robertson JH, Morris SW. cDNA cloning and characterization of a novel gene encoding the MLF1-interacting protein MLF1IP. Oncogene. 2004;23:3700–3707. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanissian SH, Teng B, Akbar U, Janjetovic Z, Zhou Q, Duntsch C, Robertson JH. Regulation of myeloid leukemia factor-1 interacting protein (MLF1IP) expression in glioblastoma. Brain Res. 2005;1047:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiwatashi A, Nishii Y, Ichikawa Y. Purification of cytochrome P-450D1 alpha (25-hydroxyvitamin D 3-1 alpha-hydroxylase) of bovine kidney mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;105:320–327. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(82)80047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF. Vitamin D: A millenium perspective. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:296–307. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF. Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2062–2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI29449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjetovic Z, Zmijewski MA, Tuckey RC, DeLeon DA, Nguyen MN, Pfeffer LM, Slominski AT. 20-Hydroxycholecalciferol, product of vitamin D3 hydroxylation by P450scc, decreases NF-kB activity by increasing IkBa levels in human keratinocytes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann B. HaCaT cell line as a model system for vitamin D3 metabolism in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:78–82. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann B. The vitamin D3 pathway in human skin and its role for regulation of biological processes. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:1246–1251. doi: 10.1562/2005-02-02-IR-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Carpio DF, Zheng Y, Bruzzo P, Singh V, Ouaaz F, Medzhitov RM, Beg AA. An essential role of the NF-kappa B/Toll-like receptor pathway in induction of inflammatory and tissue-repair gene expression by necrotic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:7128–7135. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippens S, Denecker G, Ovaere P, Vandenabeele P, Declercq W. Death penalty for keratinocytes: Apoptosis versus cornification. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1497–1508. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Xia X, Zhu F, Park E, Carbajal S, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J, Fischer SM, Hu Y. IKKalpha is required to maintain skin homeostasis and prevent skin cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:212–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Jones G. Promise of vitamin D analogues in the treatment of hyperproliferative conditions. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:797–808. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama Y, Noshiro M, Okuda K. Cloning and expression of cDNA encoding 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 1991;278:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80115-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama Y, Noshiro M, Eggertsen G, Gotoh O, Kato Y, Bjorkhem I, Okuda K. Structural characterization of the gene encoding rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:76–82. doi: 10.1021/bi00052a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama Y, Ozono K, Uchida M, Shinki T, Kato S, Suda T, Yamamoto O, Noshiro M, Kato Y. Identification of a vitamin D-responsive element in the 5′-flanking region of the rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase gene. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10545–10550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavicevic Z, Leslie CC, Malik KU. cPLA2 phosphorylation at serine-515 and serine-505 is required for arachidonic acid release in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:724–737. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700419-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S, Bikle DD, Elias PM. Vitamin D and epidermal differentiation: Evidence for a role of endogenously produced vitamin D metabolites in keratinocyte differentiation. Skin Pharmacol. 1988;1:149–160. doi: 10.1159/000210769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q, Kari C, Quadros MR, Burd R, McCue P, Dicker AP, Rodeck U. Malignant transformation of immortalized HaCaT keratinocytes through deregulated nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5209–5215. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riis JL, Johansen C, Gesser B, Moller K, Larsen CG, Kragballe K, Iversen L. 1alpha,25(OH)(2)D(3) regulates NF-kappaB DNA binding activity in cultured normal human keratinocytes through an increase in IkappaBalpha expression. Arch Dermatol Res. 2004;296:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00403-004-0509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, Semak I, Stewart J, Pisarchik A, Sweatman T, Marcos J, Dunbar C, Tuckey RC. A novel pathway for sequential transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol and expression of the P450scc system in mammalian skin. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4178–4188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A, Semak I, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, Gandy MN, Li J, Zbytek B, Li W, Tuckey RC. Enzymatic metabolism of ergosterol by cytochrome p450scc to biologically active 17alpha,24-dihydroxyergosterol. Chem Biol. 2005a;12:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A, Semak I, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, Li W, Szczesniewski A, Tuckey RC. The cytochrome P450scc system opens an alternate pathway of vitamin D3 metabolism. FEBS J. 2005b;272:4080–4090. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A, Semak I, Wortsman J, Zjawiony J, Li W, Zbytek B, Tuckey RC. An alternative pathway of vitamin D metabolism. Cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1)-mediated conversion to 20-hydroxyvitamin D2 and 17,20-dihydroxyvitamin D2. FEBS J. 2006;273:2891–2901. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Semak I, Sweatman T, Janjetovic Z, Li W, Zjawiony JK, Tuckey RC. Sequential metabolism of 7-dehydrocholesterol to steroidal 5,7-dienes in adrenal glands and its biological implication in the skin. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina CS, Tangpricha V, Uskokovic M, Adorinic L, Maehr H, Holick MF. Vitamin D and cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2515–2524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina CS, Ton L, Yao M, Maehr H, Wolfe MM, Uskokovic M, Adorini L, Holick MF. Selective vitamin D receptor modulators and their effects on colorectal tumor growth. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:757–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Kong J, Duan Y, Szeto FL, Liao A, Madara JL, Li YC. Increased NF-kappaB activity in fibroblasts lacking the vitamin D receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E315–E322. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00590.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckey RC. Progesterone synthesis by the human placenta. Placenta. 2005;26:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckey RC, Li W, Zjawiony JK, Zmijewski MA, Nguyen MN, Sweatman T, Miller D, Slominski A. Pathways and products for the metabolism of vitamin D3 by cytochrome P450scc. FEBS J. 2008a;275:2585–2596. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckey RC, Nguyen MN, Slominski A. Kinetics of vitamin D3 metabolism by cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) in phospholipid vesicles and cyclodextrin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008b;40:2619–2626. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa K. Inhibition of tumor growth by NF-kappaB inhibitors. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:990–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Waes C. Nuclear factor-kappaB in development, prevention, and therapy of cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1076–1082. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman H. Vitamin D is a membrane antioxidant. Ability to inhibit iron-dependent lipid peroxidation in liposomes compared to cholesterol, ergosterol and tamoxifen and relevance to anticancer action. FEBS Lett. 1993;326:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81809-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbytek B, Pfeffer LM, Slominski AT. Corticotropin-releasing hormone inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in human HaCaT keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1496–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbytek B, Pfeffer LM, Slominski AT. Corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulates NF-kappaB in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Endocrinol. 2004;181:R1–R7. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.181r001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbytek B, Pfeffer LM, Slominski AT. CRH inhibits NF-kappa B signaling in human melanocytes. Peptides. 2006;27:3276–3283. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbytek B, Janjetovic Z, Tuckey RC, Zmijewski MA, Sweatman TW, Jones E, Nguyen MN, Slominski AT. 20-Hydroxyvitamin D3, a product of vitamin D3 hydroxylation by cytochrome P450scc, stimulates keratinocyte differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2271–2280. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]