Abstract

The signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) is a latent IL-6 inducible transcription factor that mediates hepatic and vascular inflammation. In this study, we make the novel observation that STAT3 forms an inducible complex with the apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1)/redox effector factor-1 (APE1/Ref-1), an essential multifunctional protein in DNA base excision repair, and studied the role of APE1/Ref-1 in STAT3 function. Using a transfection-coimmunoprecipitation assay, we observed that APE1 selectively binds the NH2-terminal acetylation domain of STAT3. Ectopic expression of APE1 potentiated inducible STAT3 reporter activity, whereas knockdown of APE1 resulted in reduced IL-6-inducible acute-phase reactant protein expression (C-reactive protein and serum amyloid P) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression. The mechanism for APE1 requirement in IL-6 signaling was indicated by reduced STAT3 DNA binding activity observed in response to small interfering RNA-mediated APE1 silencing. Consistent with these in vitro studies, we also observed that lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of acute-phase reactant protein expression is significantly abrogated in APE1 heterozygous mice compared with wild-type mice. IL-6 induces both STAT3 and APE1 to bind the suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 and γ-fibrionogen promoters in their native chromatin environment. Moreover, we observed that APE1 knockdown destabilized formation of the STAT3-inducible enhanceosome on the endogenous γ-fibrionogen promoter. Taken together, our study indicates that IL-6 induces a novel STAT3-APE1 complex, whose interaction is required for stable chromatin association in the IL-6-induced hepatic acute phase response.

STAT3-APE1 complex is required for stable chromatin association in the IL-6-induced hepatic acute phase response.

The signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a latent cytoplasmic transcription factor mainly activated by the IL-6 family of cytokines, interferons, epidermal growth factor, and leptin (1,2). Upon receptor-mediated activation, STAT3 is phosphorylated on a single tyrosine residue (Tyr-705) by Janus activated kinases, in a manner shared with all seven STAT family members. Phosphorylated STATs subsequently dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they activate target gene transcription by several mechanisms, including recruiting nuclear coactivators that mediate chromatin decondensation and communicating with proteins binding the core promoter (3,4,5).

STAT3 was first described as acute-phase response factor, a DNA binding protein activated in IL-6-stimulated hepatocytes that binds and mediates expression of acute-phase response (APR) genes (6). In the APR, significant alterations occur in secretion of plasma proteins (acute-phase reactants) that are largely mediated at the level of gene expression (7). Because the acute phase reactant proteins (APP) play important roles in macrophage opsonization, innate immunity, wound repair, and nutritional homeostasis, the signaling mechanisms by STAT3 transcription factors controlling the APR have been investigated intensively (8).

Biological effects of STAT3 have been evaluated by targeted gene ablation in transgenic mice. Unlike other STAT family members, all of which have produced viable mice with relatively limited phenotypes, ablation of STAT3 led to early embryonic lethality (9,10,11). In fact, targeted knockdown of STAT3 selectively in the hepatocyte shows its essential role in mediating expression of acute phase response genes, down-regulating gluconeogenic enzymes, protecting against Fas-mediated apoptosis, and promoting hepatocyte growth/regeneration (12,13,14). Together these findings indicate the critical role of STAT3 in mediating the transcriptional networks that underlie inducible liver function.

Although nuclear translocation is required for STAT3 activity, STAT3-dependent transcription is mediated by direct posttranslational modifications coupled with its complex formation with nuclear coactivators. For example, both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation are required for STAT3 dimerization and transcriptional activation (15), yet other posttranslational modifications, including glutathionylation (16) and acetylation (17), modify its function. Indeed, it has been found that both STAT1 and -3 isoforms are inducibly acetylated, a modification yielding a variety of consequences for target gene transcription (18,19,20). For example, we have shown that IL-6-induced acetylation of STAT3 NH2 terminus is required for interaction and promoter recruitment of the p300 coactivator and cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (19,21). The former interaction produces stabilization of enhanceosome formation, whereas the latter interaction results in STAT3 recruiting the positive transcription elongation factor-b complex, which phosphorylates the RNA Pol II COOH-terminal domain (CTD), converting it to active elongation mode (21). In addition, we have also recently shown that IL-6-induced acetyl-STAT3 promotes its association with histone deacetylase 1, required for proper nucleocytoplasmic distribution of STAT3 and for re-establishing homeostasis for the next inductive STAT3 cellular response (22). Thus, we have established an essential role of NH2-terminal acetylation of STAT3 in protein-protein interaction resulting in stable formation of the enhanceosome complex, target gene expression, and nucleoplasmic shuttling.

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1)/reduction-oxidation (redox) effector factor-1 (Ref-1) is an ubiquitously expressed multifunctional protein originally identified as an essential factor in the DNA base-excision repair pathway (23,24,25). That APE1/Ref-1 is activated by STAT3 was shown by the finding that constitutively activated STAT3 augments APE1/Ref-1 expression, and reduced apoptosis by suppressing oxidative stress and redox-sensitive caspase-3 activity (13). Because proteins involved in similar biological pathways are coexpressed, we investigated whether APE1 expression controls IL-6-STAT3-mediated hepatic and vascular inflammation. Here we show for the first time that IL-6 induces a nuclear complex of STAT3 and APE1 and that the NH2-terminal acetyl-acceptor domain of STAT3 is required for APE1 binding. APE1 knockdown by RNA interference inhibits STAT3 DNA binding activity and demonstrates the requirement of APE1 in transcriptional activation of STAT3-regulated APR genes. We observed defective lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced APP expression in APE1+/− heterozygous mice compared with APE1WT mice. We further confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay that IL-6 induces STAT3-mediated recruitment of APE1 to an endogenous target promoter, associated with enhanceosome complex formation with p300 and phospho-Ser2 CTD Pol II recruitment. In the absence of APE1, enhanceosome formation and Pol II CTD phosphorylation was significantly reduced. Taken together, our study provides important insight into the mechanism of IL-6-induced STAT3-APE1 complex in controlling the transcriptional switch underlying the hepatic APR.

Results

IL-6 induces a nuclear STAT3-APE1 complex

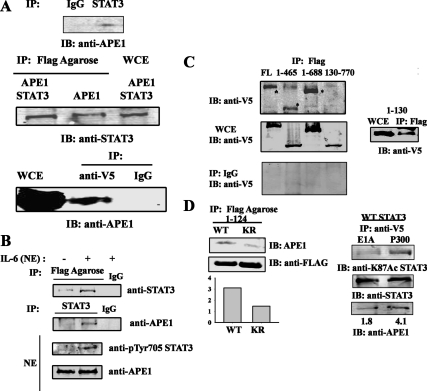

To elucidate the role of APE1 in IL-6-STAT3 transcriptional complex we first sought to determine whether STAT3 physically associates with APE1 in cellulo. For this purpose, whole cell extracts (WCE) prepared either from untransfected cells or from ectopically expressing FLAG-tagged APE1 in the presence or absence of V5-tagged STAT3. Extracts were subjected to nondenaturing coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay using anti-STAT3 (Fig. 1A, top panel) or anti-FLAG conjugated agarose beads (Fig. 1A, middle panel). The immune complexes were fractionated on SDS-PAGE and associated proteins were detected by Western immunoblot. We observed that endogenous STAT3 binds to endogenous APE1 (in Fig. 1A, top panel) and ectopically expressed APE1 (Fig. 1A, lane 1, middle panel) interacts with STAT3. Conversely, Co-IP assay of the extracts (containing ectopically expressed STAT3-V5 and APE1-FLAG) with anti-V5 antibody (Ab) followed by immunoblot with anti-APE1 Ab confirm that APE1 is present in STAT3 immune complex (Fig. 1A, lane 2, lower panel). We did not observe any complex formation using IgG as the immunoprecipitating Ab, demonstrating assay specificity.

Figure 1.

STAT3 complexes with APE1. A, The physical interaction of STAT3 with APE1. HepG2 cells were stimulated with IL-6 (8 ng/ml) and WCE (2 mg) were immunoprecipitated either by IgG or anti-STAT3 Ab. Endogenous APE1 was detected by Western immunoblot with anti-APE1 Ab (top panel). HEK293 cells were cotransfected with either pEF6-V5-STAT3 and pCMVAPE1-FLAG or pCMVAPE1-FLAG alone. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with IL-6 (8 ng/ml) for 30 m before WCE was prepared. One milligram of WCE was immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG conjugated agarose Ab. APE1-FLAG-bound STAT3 was detected by anti-STAT3 Ab in Western immunoblot (middle panel). WCE of pEF6–V5-STAT3 and pCMVAPE1-FLAG were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 Ab and STAT3-V5-associated APE1 was detected by anti-APE1 Ab (lower panel). Immunoprecipitation (IP) with control mouse IgG shows no signal indicating assay specificity. B, Inducible STAT3-APE1 association upon IL-6 stimulation. Unstimulated and IL-6 stimulated NEs (1.5 mg) were prepared from HepG2 cells transfected with pCMVAPE1-FLAG and immunoprecipitaed with either control mouse IgG or anti-FLAG conjugated agarose Ab or anti-STAT3 Ab. The immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western immunoblot with anti-STAT3 Ab (upper panel) or anti-APE1 Ab. Expression of phospho-Tyr-705 STAT3 and APE1 in HepG2 NEs were shown at the bottom panel. C, Mapping of APE1 binding site on STAT3. HEK293 cells were transfected with either full-length STAT3-V5 expression vector, (amino acids 1–770) or with different deletion mutants of STAT3 (aa 1–130, 1–465, 1–688, and 130–770) and pCMVAPE1-FLAG. IL-6 stimulated WCE were immunoprecipitated with anti FLAG Ab and Western immunoblots were performed with anti-V5 Ab (upper panel). *, FLAG-bound V5 STAT3 deletion mutants. Middle panel, Expression of different V5-tagged STAT3 deletion mutants; bottom panel, IP of WT STAT3 and its deletion mutants with control mouse IgG. Right panel, IP with low MW STAT3 deletion mutant (aa 1–130). D, Association of endogenous APE1 with acetylated STAT3. HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged STAT3 WT (1–124) and STAT3 K49R/K87R (KR) (1–124) (left panel). WCE were immunoprecipitated with FLAG-agarose conjugate and immune-complexes were detected with anti-APE1 Ab. Quantitation of APE1 protein associated with STAT3 WT (1–124) and STAT3 K49R/K87R (1–124) were shown at the bottom. HEK293 cells were transfected with WT STAT3 along with either P300 or adenovirus 12SE1A (right panel). WCE were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 Ab and immunoblotted with anti-K87Ac STAT3 Ab (top) or anti-STAT3 Ab (middle) or with anti-APE1 Ab (bottom). IB, Immunoblot; V5, tagged Ab.

Next, to determine whether the association of STAT3-APE1 is stimulus-dependent, cells transfected with FLAG-tagged APE1 were IL-6 stimulated. Nuclear extracts (NE) were then subjected to Co-IP assay using either anti-FLAG conjugated agarose beads (upper panel) or anti-STAT3 Ab (lower panel) and immune complexes were analyzed for the presence of either STAT3 (upper panel) or APE1 (lower panel). Figure 1B shows that IL-6 induces a strong STAT3-APE1 interaction in IL-6-stimuated NE, but not in unstimulated NE, indicating that the interaction is primarily stimulus-dependent (compare lane 2 vs. lane 1, Fig. 1B). Together, these data suggest that IL-6-induced STAT3 nuclear translocation is essential for the formation of a STAT3-APE1 complex.

APE1 interacts with the acetylated NH2 terminus of STAT3

To identify the domain(s) of STAT3 required for APE1 interaction, Co-IP experiments were conducted using WCEs from cells transfected with a series of V5-tagged STAT3 deletion mutations [amino acids (aa) 1–770, aa 1–130, aa 1–465, aa 1–688, and aa 130–770] and FLAG-tagged APE1. After immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG conjugated agarose beads, immune complexes were assayed in Western blot using anti-V5 Ab to detect associated STAT3. Full-length STAT3 (aa 1–770) and all carboxyl terminal- deleted STAT3 (aa 1–130, aa 1–465, aa 1–688) but not the NH2 terminal- deleted STAT3 (aa 130–770) were detected in APE1 immune-complex (Fig. 1C, top left panel, lane 4) indicating that the NH2-terminal domain of STAT3 is required for APE1 binding.

The STAT3 NH2-terminal domain (aa 1–130) contains the two major acetyl acceptor lysine residues of STAT3, at residue 49 and 87 (19). We therefore next tested whether the association between the STAT3 NH2-terminal domain and APE1 is regulated by STAT3 NH2-terminal acetylation. For this purpose, we conducted nondenaturing Co-IP assays of FLAG-tagged STAT3 wild-type (WT) (1–124) or acetylation-deficient STAT3 (K49R/K87R) (1–124) mutant for association with APE1. We observed that in contrast to STAT3 WT (1–124), STAT3 K49R/K87R (1–124) only weakly bound APE1 (Fig. 1D, left panel). We further confirm this by modulating the acetylation status of WT V5-tagged STAT3 by transfecting cells either with P300 or with adenovirus 12SE1A (19) (which inhibits P300-mediated acetylation). Cells transfected with P300 shows increased level of K87Ac STAT3 (right hand panel, top) and hence increased APE1 association (bottom) than the cells transfected with 12SE1A (Fig. 1D, right hand panel).

Together, these results indicate that NH2-terminal domain of STAT3 as well as its acetylation is necessary for functional recruitment and stable complex formation with APE1.

APE1 transactivates STAT3

To gain further insight into how STAT3-APE1 interaction could control target gene expression, we examined the effect of ectopically expressed APE1 on luciferase reporter activity driven by the IL-6-inducible enhancer and STAT3 DNA-binding site from the angiotensinogen promoter, termed (hAPRE1)5-LUC (26,27). We observed that in the presence of control empty vector there is a significant increase (12-fold induction) of luciferase activity in presence of IL-6 compared with the unstimulated cells. Expression of full-length APE1 (aa 1–318) further activated reporter activity (3.5-fold over empty vector) in IL-6 stimulated cells (Fig. 2A). Cotransfection of APE1 NH2-terminal deletion mutant Δ N (aa Δ 1–42) inhibited IL-6-induced STAT3 reporter activity, whereas expression of COOH-terminal deletion mutant Δ C (aa Δ 218–318) had very little effect on transcriptional coactivator property of APE1 (Fig. 2A). To further confirm the role of APE1 NH2-terminal deletion mutant in STAT3 transactivation we checked whether it at all binds to STAT3. Fig. 2B shows that APE1WT, but not the APE1Δ N (aa Δ 1–42), binds to endogenous STAT3 when subjected to Co-IP assay. These data further indicate that the NH2 terminus of APE1 is required for STAT3-dependent transactivation.

Figure 2.

APE1 enhances IL-6 mediated STAT3 transactivation. A, APE1 induces IL-6 mediated hAGT reporter activity. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with (hAPRE1)5-LUC and either with APE1 full-length (FL) expression vector (EV; aa, 1–318), or NH2-terminal deleted APE1 (ΔN, deletion of aa, 1–42) or COOH-terminal deleted APE1, (ΔC, deletion of aa 218–318) expression vectors were transfected. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were simulated with IL-6. Luciferase activity was measured after 24 h. *, P < 0.05 relative to empty vector, t test. Expression level of the APE1 FL and deletion mutants were shown by Western immunoblot (inset). B, APE1 NH2-terminal domain is required for STAT3 binding. HEK293 cells were transfected with either FLAG-tagged APE1 full-length (FL) expression vector or NH2-terminal deleted APE1 (ΔN, aa 1–42 deletion) and WCE were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG Ab and Western immunoblots (IB) were performed with STAT3 Ab (upper panel). Middle panel, Immune pulldown of FLAG-tagged WT APE1 and NH2-terminally deleted APE1 with anti-FLAG Ab. Lower panel, Expression of endogenous STAT3 and ectopically expressed APE1 WT and APE1ΔN. EV, Empty vector control.

APE1 facilitates STAT3 DNA binding

Previous studies indicated that APE1 functions as a redox factor and stimulated DNA-binding activity of numerous transcription factors involved in inflammation and cancer progression, such as NF-κB, AP-1, HIF1a, P53, and others (28,29,30). To investigate whether APE1 is required for inducible STAT3 DNA-binding activity, we knocked down APE1 expression by RNA interference. Western blot analysis showed that significant reduction of APE1 protein level (>70%) (Fig. 3A) was achieved with transfection of APE1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (100 nm) compared with control siRNA treatment. During this period, no morphological or growth defects were observed in response to APE1 down-regulation (data not shown). To determine whether APE1 knockdown affects STAT3 nuclear translocation, accumulation of phospho-Tyr705 STAT3 was determined by Western blot in IL-6 stimulated NE. We observed that IL-6-inducible phospho-Tyr705 STAT3 accumulation was not affected in APE1 siRNA-treated cells compared with control (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

APE1 is required for STAT3 DNA binding. A, APE1 knockdown in HepG2 cells by specific siRNA. HepG2 cells were transfected with indicated amounts of control and APE1 siRNA (Smart Pool from Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO). WCE were isolated 72 h after transfection and Western immunoblots were performed with anti-APE1 Ab (upper panel). Lower panel, Expression of β-actin as internal control. B, Nuclear translocation of phospho-Tyr-705 STAT3 after APE1 siRNA treatment. Unstimulated and IL-6-stimulated NEs were prepared from HepG2 cells transfected with either control siRNA or APE1 siRNA and Tyr phosphorylated STAT3 was detected by Western immunoblot analysis with phospho-Tyr-705 STAT3 Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Lower panel, Immunoblot of above NEs with anti-PCNA Ab as a nuclear marker. C, Effect of APE1 siRNA on STAT3 DNA binding. HepG2 cells were transfected with either control siRNA (lanes 1–5) or APE1 siRNA (lanes 6–10) and stimulated with IL-6 (lanes 2–5 and 7–10). Lanes 1 and 6 are unstimulated controls. NEs from homogeneous population of HepG2 cells were used to bind 32P-labeled WT SIE in EMSA. Lanes 5 and 10 are competition with unlabeled WT SIE. NE, Nuclear extract; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen.

Next, to examine whether APE1 affects STAT3 DNA-binding, we used EMSA with [32P]-labeled high affinity sis-inducible element (SIE) site, a sequence modified from the human c-fos promoter (31,32) and NE prepared from IL-6-stimulated HepG2 cells transfected with either control siRNA or APE1 siRNA (Fig. 3C). After 15 min of IL-6 stimulation, inducible complexes were formed in control siRNA-treated NE in a dose-dependent manner, detectable with as little as 5 μg of NE (Fig. 3C, lanes 2, 3, and 4). On the other hand, IL-6-stimulated STAT3 DNA-binding activity was significantly attenuated upon APE1 knockdown (Fig. 3C, lanes 7, 8, and 9). Inducible complex formation in presence of control and APE1 siRNA can be competed out with increasing amounts of cold WT oligonucleotides (50× molar excess), as shown in lanes 5 and 10, Fig. 3C. These results demonstrate that APE1 is required for stimulus-dependent STAT3-DNA-binding activity in vitro.

APE1 knockdown affects STAT3 target gene activation

To determine more directly that APE1 is an essential component of STAT3 transcriptional complex and affects STAT3 target gene activation, we used a HeLa S3 cell line stably expressing APE1-specific small hairpin RNA (shRNA) from a doxycycline-inducible promoter as described previously (33). Treatment of these cells with Dox for 8 d significantly down-regulated endogenous APE1 compared with cells stably expressing control shRNA (Fig. 4A). To examine this effect of APE1 knockdown on IL-6-inducible APP expression, the expression of human C-reactive protein and human serum amyloid A protein mRNA were measured by quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RT-PCR) (Fig. 4B). In contrast to untreated cells, where human C-reactive protein and human serum amyloid A protein were induced by 14- and 13-fold, respectively, their inductions in Dox-treated cells were significantly decreased in presence of IL-6. From this result, we concluded that IL-6-induced STAT3-regulated APP expression requires APE1 expression. Next, to determine whether the effect of APE1 on STAT3 transcription is cell type-specific or global phenomena, we examined the effect of APE1 knockdown (by siRNA treatment) on IL-6-inducible monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP1) expression. For this purpose, we used human acute monocytic leukemia THP1 cells and quantitated the abundance of MCP1 mRNA expression in APE1 down-regulated cells after IL-6 induction. Figure 4C shows that after APE1 knockdown, the induction of MCP1 mRNA was significantly abrogated after IL-6 induction compared with control. These data further suggest that APE1 play an important role in STAT3 target gene activation.

Figure 4.

APE1 knockdown affects STAT3 target gene expression. A, Doxycycline (Dox) treatment knockdown APE1 expression in tetracycline regulated HeLa S3 cells. Shown is the Western blot of APE1 expression after 7 d of Dox treatment. Lower panel, IB for anti-β-actin. B, APE1 knockdown affects STAT3 regulated APP expression. HeLa cells were treated with Dox for 10 d and total cellular RNA were isolated from unstimulated and IL-6-stimulated (30 min) cells and expression of human C reactive protein (hCRP) and human serum amyloid A protein (hSAP) were measured by Q-RT-PCR (Table 1). The fold change in IL-6-treated cells over IL-6-unstimulated control was obtained after correction for the amount of internal control, GAPDH. The mRNA induction in Dox-untreated cells was compared with that in Dox-treated cells. C, siRNA (Dharmacon, Inc., Lafayette, CO) mediated knockdown of APE1 affects MCP1 expression in THP1 cells. THP1 cells were transfected with either control siRNA or APE1 siRNA. Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with IL-6 for 24 h and total RNA was extracted for real time Q-RT-PCR analysis. The data were analyzed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.01.

LPS-induced APP expression is impaired in APE1 heterozygous mice

We showed previously that LPS is a potent activator of the hepatic APR and an inducer of APP in rodents (34). To determine whether APE1 modulates IL-6-STAT3-induced APP expression in vivo, we examined the LPS-induced APP response of APE1 heterozygous mice. APE1 heterozyous mice were used because APE1 nullizygous mice are embryonic lethal, whereas APE1 heterozygous mice have reduced APE1 expression, yet are viable and normal in appearance (35,36). Western blot analysis of liver tissue extract shows that APE1+/− mice have lower APE1 protein expression than that seen in WT C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5A). Groups of WT C56BL/6 and APE1+/− mice were then challenged with LPS for 3 h and hepatic APP expression quantitated by Q-RT-PCR. Figure 5B shows that although ip injection of LPS potently activated mouse α1-acid glycoprotein and c-fos expression in WT mice, this effect was significantly impaired in APE1+/− mice. These data further strengthen and support the in vitro findings that APE1 is a crucial component in IL-6-STAT3 pathway under pathophysiological conditions in vivo.

Figure 5.

LPS-induced APP expression is affected in APE1+/− mice. A, APE1 expression in WT C57BL/6 mice and APE1+/− mice. Four WT and APE1+/− mice liver extract were run on SDS-PAGE gel and after transfer on PVDF, Western immunoblot analysis were done with anti-APE1 Ab. Right panel, Average of APE1 protein level in WT and APE1+/− mice (n = 4). B, LPS- untreated and LPS-treated (17 mg/kg, 3 h) WT and APE+/− mice (four in each group, total of 16 mice) were killed and total RNA was isolated from liver and quantitated for real-time RT-PCR analysis for mouse AGP (mAGP) and C-fos genes (Table 1). Shown is the average of APP induction from each group (n = 4). The data were analyzed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05.

APE1 is required for stable enhanceosome assembly in STAT3 target promoter

APE1 by itself has no affinity for a specific cis-element; rather, it affects promoter activity by binding to transcription factor specific for distinct cis-element. To examine whether STAT3 is necessary for APE1 recruitment on STAT3-dependent suppressor of cytokine signaling (socs)3 promoter, we used a two-step ChIP assay in STAT3+/− and STAT3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells. Socs3 was selected as a target gene because earlier work has shown that socs3 is a highly inducible STAT3-dependent gene in MEFs (37), and because MEFs express low levels of IL-6Rα, oncostatin M (OSM) was used in this experiment to activate STAT3 signal transduction (37,38). Figure 6A shows that in STAT3+/− MEFs, both STAT3 and APE1 rapidly associate with the socs3 promoter within 30 min after OSM stimulation. In contrast, in STAT3−/− MEFs, APE1 is not recruited to the socs3 promoter. Unstimulated STAT3+/− and STAT3−/− MEFs did not show any significant level of STAT3 or APE1 binding to the mouse socs3 promoter (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Recruitment of STAT3, APE1 and enhanceosome complex on STAT3 target promoter. A, APE1 is recruited on socs3 promoter by STAT3. STAT3+/− and STAT3−/− MEFs were treated with OSM (20 ng/ml) for 30 min and two-step ChIP assay was performed by using Abs specifically recognizing STAT3, APE1, or IgG. The sequence of the socs3 promoter in the immunoprecipitates was amplified by Q-RT-PCR using specific primers. Shown is signal in the immunprecipitates expressed as a percentage of the DNA present in the input. The signals in OSM-treated STAT3+/− cells were compared with OSM-treated STAT3−/− MEFs. B, APE1 regulates enhanceosome assembly on human γ-FBG promoter. Tetracycline regulated HeLa S3 cells expressing APE1 shRNA were treated with doxycycline (Dox) for 10 d or left untreated as above and then stimulated with IL-6 for 20 min. ChIP assay was performed using STAT3, APE1, p300, and phosphoSer2 CTD Pol II Ab. The sequence in the promoter of the γ-FBG in the immunoprecipitates were amplified by Q-RT-PCR using specific primer set as shown in Table 2. IL-6 recruited STAT3, APE1, and p300 to γ-FBG promoter and also increases phospho-RNA Pol II (p-RNApol II)-loading in γ-FBG promoter in Dox-untreated cells. Dox-treated cells showed reduced p300 and phospho RNA Pol II association. The results were expressed as means ± sd from triplicates. The signals in Dox-untreated cells were compared with Dox-treated HeLa cells. The data were analyzed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.01.

We previously showed that IL-6 induces STAT3, p300, and RNA Pol II phospho-Ser2 CTD to form a stable enhanceosome complex on target genes (21). To examine whether APE1 is also a part of this complex, we performed ChIP assay in APE1 down-regulated HeLa cells. Figure 6B shows that in absence of Dox, IL-6 induces STAT3, APE1, p300, and phospho-Ser2 CTD Pol II binding on the endogenous γ-fibrionogen (FBG) promoter. Conversely, in presence of Dox, IL-6-induced STAT3 and p300 binding to the γ-FBG promoter were significantly inhibited. In addition, phospho-Ser2 CTD Pol II loading was potently attenuated in absence of APE1. We interpret this to mean that the reduced STAT3 and p300 binding caused by the APE1 knockdown secondarily affects phospho-Ser2 CTD Pol II binding because of its direct interaction with p300 (37). Together, these data indicate that STAT3 recruits APE1 to IL-6-inducible enhancers in a promoter and cell type-independent manner, and that APE1 is required for stable enhanceosome assembly.

Discussion

STAT3 is the major transcription factor activated by the IL-6 family of cytokines via gp130 receptor, controlling genes important in the hepatic APR (39,40). Although the STAT3 signaling from the cell membrane to the nucleus is well understood, the molecular events regulating gene transcription need more elucidation. In this study, we unraveled the molecular mechanism by which STAT3 transactivation is controlled by APE1, functioning to facilitate DNA binding and enhanceosome formation. Here we have demonstrated that IL-6-induced STAT3-APE1 complex formation plays an important role in STAT3-mediated activation of APR genes both in cellulo and in vivo. The evidence of APE1 in regulating STAT3's transcriptional activity include 1) their stable interaction in a IL-6-dependent manner, 2) down-regulation of APE1 levels significantly affected IL-6-STAT3-mediated activation of APP, and 3) knockdown of APE1 reduced stable enhanceosome complex formation to the endogenous STAT3 promoter.

We have shown that the NH2-terminal region of STAT3 (1–124) including the acetyl acceptor K49 and K87 are necessary for its interaction with APE1. Our earlier studies indicated that IL-6-induced NH2-terminal acetylation of STAT3 is important for its interaction with the transcriptional coactivator p300, which plays an essential role for activation of its target genes (19). It appears likely that acetylation-mediated conformational changes in STAT3's NH2-terminal domain modulate its interaction with partner proteins. Thus, we observed that IL-6-induced NH2-terminal acetylation of STAT3 enhances its binding to APE1 or other cofactors such as p300 and CDK-9 leading to activation of the STAT3-dependent promoter, whereas lack of acetylation in the STAT3 (1–124) K49R/ K87R mutant significantly decreased its association (Fig. 1D) (22,37).

Although activation of APE1 expression by constitutively activated STAT3 was implicated in Fas-induced liver injury (13), whether and how activated APE1 controls STAT3-mediated transcription was unknown. In this study, we provide evidence, for the first time, that APE1 directly regulates STAT3's trancriptional activity because down-regulation of APE1 levels decreased its target gene expression by modulating its binding to the promoter. To support this, we have shown that APE1 knockdown decreased STAT3's DNA binding activity in in vitro EMSA. However, the exact mechanism by which APE1 regulates STAT3's DNA-binding is still not clear. Although it was proposed previously that Cys65 was the redox-active residue in APE1 for activation of several transcription factors (41), we have found that ectopic expression of Cys 65 Ser mutant has no effect on IL-6-STAT3-mediated hAGT promoter activity (data not shown). This suggests that APE1's redox activity may not be required for promoting the transcriptional activity of STAT3. Both redox-dependent and redox-independent transcriptional functions of APE1 are required for modulating p53 DNA binding (29). Indeed, one recent study showed that mutation of all the Cys residues left APE1 still capable of enhancing c-Jun or p50 DNA binding in the presence of small amounts of glutathione or thyoredoxin. This novel activity was proposed as a redox chaperone activity of APE1 (28). Consistent with this possibility, whether and how APE1's redox chaperone activity regulate STAT3's DNA binding needed to be determined.

We have shown that APE1's NH2-terminal domain is essential for activation of STAT3's reporter activity because deletion of NH2-terminal was unable to activate STAT3-depenedent promoter-reporter (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this observation, one recent study also showed that the APE1 NH2-terminal domain is essential for stable binding with the transcription factor YB-1 and APE1 stimulates DNA-binding activity of YB-1 in a redox-independent way leading to activation of MDR1 promoter (42).

Although several transcriptional coactivators such as p300 and CDK9 had already been shown to play an important role in STAT3-dependent target gene activation, our present study has identified APE1 as a novel additional trancriptional coactivator in modulating STAT3 DNA binding activity. Our observation that knockdown of APE1 level decreased APR gene expression in cultured cells and as well as in vivo provide the first evidence that STAT3-dependent gene expression is dependent on APE1 levels and its activity.

Although APE1 was identified in diverse trans-acting complexes, APE1 by itself has no affinity for any specific cis element; rather, it affects promoter activity by binding to trans-acting factors specific for distinct cis elements (43). Recently, post translational modifications of APE1 such as acetylation and ubiquitination are identified to modify its function (44,45). APE1's presence in several trans-acting complexes requires interaction with diverse partners. In the case of the PTH negative calcium response element, APE1 was identified in a complex with hnRNP-L and histone deacetylase 1 (44,46). Similarly, in hypoxia-induced activation of VEGF expression, APE1 was found as a component of HIF1α transcriptional complex and in the MDR1 promoter, APE1-YB-1 interaction plays an important role in DNA binding (42). Consistent with this, our observation that STAT3 is essential for APE1's recruitment to the socs3 promoter is shown in the STAT3-deficient MEFs. Interpreted with our findings in the Dox-inducible APE1 knockdown cells that IL-6-induced STAT3 promoter occupancy was reduced, indicates that although APE1 binding is targeted via STAT3, its presence is required for stable STAT3 interaction with the target promoter.

It is interesting to note that STAT3 activates APE1 expression (13), and because IL-6 is the major regulator of STAT3 activation, we also observed an obvious time-dependent increase in APE1 expression in human aortic endothelial cells stimulated with IL-6 (our unpublished data). This raises the possibility that IL-6 may induce APE1 expression, which in turn modulates STAT3 transcription activity and thus would act in a positive feedback loop. Thus we propose that IL-6-induced p300-mediated acetylation of STAT3 stabilizes its interaction with APE1, p300, and other cofactors that, in turn, lead to positive transcription elongation factor-b recruitment and thus serve as a platform for loading of RNA pol II to enter transcription elongation mode (21).

In summary, we have shown that the IL-6-induced STAT3-APE1 complex plays an important role in STAT3-mediated activation of APR genes, both in cellulo and in vivo. Furthermore, the effect of APE1 in STAT3-mediated target gene activation in hepatocytes and monocytes have established that APE1 mediated activation of STAT3 function is a general phenomenon and thus implicate the role of APE1 in APR and hepatic inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells and HEK293 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured as previously described (19,21). STAT3+/− and STAT3−/− MEFs were obtained from Dr. Stephanie Watowitch at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). APE1 HeLa Tet-ON cell, a generous gift from Dr. Gianluca Tell, University of Udine, Italy, were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 3 μg/ml blasticidin, 100 μg/ml zeocin, 4.5 g/liter glucose, and 1 mm sodium pyruvate (33). Human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells (ATCC) were cultured at 37 C in 5% CO2 in RPMI medium 1640 with 25 mm HEPES and 2 mm l-glutamine supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 4.5 g/liter glucose, and 1 mm sodium pyruvate. Recombinant human IL-6 was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and recombinant mouse OSM was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Doxycycline and LPS were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Plasmids and transfection

Transient transfections in exponentially growing HepG2 cells were performed using Lipofectamine PLUS reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). One microgram of indicated promoter reporter was cotransfected with the transfection efficiency control plasmid pSV2PAP, and indicated expression plasmids into six-well plates (2.5 × 105cells). Twelve hours later, cells were stimulated with IL-6 (8 ng/ml, 24 h) before harvest and assay of luciferase and alkaline phosphatase activity. All transfections were carried out in triplicate plates in three independent experiments. For coimmunoprecipitation assay, indicated expression plasmids were cotransfected into 10-cm2 dishes using the same protocol and cells were harvested for protein extraction 24 h after transfection.

siRNA transfection

APE1 siRNA (Dharmacon Smart Pools) were transfected into cells by TransIT-siQUEST transfection reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI) at 50 nmol/liter final concentration, following the manufacturer's instruction.

Antibodies and immunoprecipitation

Polyclonal antibodies of p300 (N-15), anti-phospho-Tyr STAT3 (B7), STAT3 (C-20 and K-15), and antimouse human APE1 (sc-2104) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal APE1 Ab (NB100–116) was obtained from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibodies against V5 was purchased from Invitrogen and β-actin and FLAG-agarose conjugate were obtained, from Sigma-Aldrich. Monoclonal anti-phospho-Ser2 CTD Pol II Ab (H5) was from Covance (Emeryville, CA). For immunoprecipitation, either WCEs or NEs were used as mentioned. WCEs were prepared by lysing HepG2 or HEK293 cells in modified RIPA buffer [50 mm Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm PMSF, 1 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin]. Sucrose cushion-purified NEs were prepared by lysing HepG2 cells with nonionic detergent (0.5% IGEPAL-60) and centrifugation over a sucrose cushion as described (26,27). Extracts were precleared with protein A-Sepharose 4B (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 4 C and the cleared lysate incubated with primary Ab for 2–12 h at 4 C. Immune complexes were captured by adding 30 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (50% slurry) and rotated for 1 h at 4 C. Beads were washed three times for 5 min with cold PBS, immune complexes eluted by incubation in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and blocked with 5% milk for 1 h followed by primary antibody treatment for overnight at 4 C. Membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline Tween (TBST) containing 1% Tween and incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h. Signals were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence assay (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) or visualized by the Odyssey Infrared Imaging system (LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

EMSA

NEs were prepared by transfecting HepG2 cells with control and APE1 siRNA in the absence and presence of IL-6. Double stranded [32P]-labeled SIE oligonucleotide probe was used to bind 5–20 μg NE. WT and mutant SIE probes used as a compititors and SIE oligonucleotide were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The reactions were fractionated by nondenaturing electrophoresis on 5% PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Induction of APR in APE1+/− mice

APE1+/− heterozygous mice (35,36) and WT C57BL/6 mice were treated in compliance with our institutional animal care and use committee-approved protocol. APE1+/− mice and WT C57BL/6 mice were injected with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, 17 μg/g body weight) into the peritoneum under light anesthesia, and euthanized 0 and 3 h later (four mice for each time). Liver sections were then isolated for WCE and total RNA preparations.

Q-RT-PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted by Tri Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). One microgram of RNA was used for reverse transcription using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Three microliters of cDNA products were amplified in 20-μl reaction system containing 10 μl iQ SYBR Green Super Mix (Bio-Rad) and 400 nm primer mix. All the primers were designed by Primer Express version 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA) and were listed in Table 1. All reactions were processed in MyiQ Single-Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and results were analyzed by IQ5 program (Bio-Rad). To normalize template input, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (endogenous control) transcript level was measured for each sample. Data are expressed as fold change relative to unstimulated, after normalizing to GAPDH.

Table 1.

Primer set for Q-RT-PCR

| Target genes | Sense (5′–3′) | Antisense (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| hMCP1 | CATTGTGGCCAAGGAGATCTG | CTTCGGAGTTTGGGTTTGCTT |

| hCRP | GCGGGCCCTTCAGTCCTA | CACTTCGCCTTGCACTTCATAC |

| hSAP | AGCTGGGAGTCCTCATCAGGTA | CGCAGACCCTTTTTCACCAA |

| mAGP | GCGCTGCACACGGTCTTA | TGGGTTCTGAGCTTCCAACAT |

| mcfos | CCTGCCCCTTCTCAACGA | TCCACGTTGCTGATGCTCTT |

ChIP assay

Two-step ChIP was performed as described (47). In brief, 4–6 × 106 MEF cells per 100-mm dish were washed twice with PBS after stimulation. Protein-protein cross-linking was first performed with disuccinimidyl glutarate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) followed by protein-DNA cross-linking with formaldehyde. After cells were washed and collected in 1 ml PBS, pellets were lysed by sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer and sonicated four times, 15 sec each at setting four with 10 sec break on ice until DNA fragments lengths were between 200 and 1000 bp. Equal amounts of DNA were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4 C with 4 μg indicated Abs in ChIP dilution buffer. Immunoprecipitates were collected with 40 μl protein-A magnetic beads (Dynal Inc., Brown Deer, WI), and washed sequentially with ChIP dilution buffer, high-salt buffer, LiCl wash buffer, and finally in 1× TE buffer. DNA was eluted in 250 μl elution buffer for 15 m at room temperature. Samples were de-cross-linked in de-cross-linking mixture at 65 C for 2 h. DNA was phenol/chloroform extracted, precipitated by 100% ethanol and used for RT-PCR.

Table 2.

Primer set for ChIP assay

| Target promoter | Sense (5′–3′) | Antisense (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Human γ-FBG | AGCTTCAACCTGTGTGCAAAAT | CCGTTCCTTTTTCCTCATCCT |

| Mouse Socs3 | CGCGCACAGCCTTTCAGT | CCCCCGATTCCTGGAACT |

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sankar Mitra from University of Texas Medical Branch for providing APE1 expression plasmids and APE1+/− heterozygous mice and Dr. Gianluca Tell from University of Udine, Italy for generously providing APE1 shRNA HeLa Tet-on cell line. We also thank Dr. Stephanie Watowitch from University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and Dr. David Levy from New York University for providing STAT3+/− and STAT3−/− MEFs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute R01 HL070925 (to A.R.B.) and American Heart Association Grant 0665129Y (to S.R.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 23, 2009

Abbreviations: aa, Amino acids; Ab, antibody; APE1, apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1; APP, acute phase reactant proteins; APR, acute-phase response; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; Co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation; CTD, COOH-terminal domain; FBG, fibrionogen; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCP1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; NE, nuclear extracts; OSM, oncostatin M; Q-RT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; redox, reduction-oxidation; Ref-1; redox effector factor-1; SIE, sis-inducible element; shRNA, small hairpin RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; WCE, whole cell extracts; WT, wild type.

References

- Levy DE, Darnell Jr JE 2002 Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3:651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Lee CK 2002 What does Stat3 do? J Clin Invest 109:1143–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell Jr JE, Kerr IM, Stark GR 1994 Jak-STAT pathways and transcritptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell Jr JE 1997 STATs and gene regulation. Science 277:1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler C, Darnell Jr JE 1995 Transcriptional response to polypeptide ligands: the JAK-STAT pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 64:621–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegenka UM, Buschmann J, Lütticken C, Heinrich PC, Horn F 1993 Acute-phase response factor, a nuclear factor binding to acute-phase response elements, is rapidly activated by interleukin-6 at the posttranslational level. Mol Cell Biol 13:276–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch H, Schreiber G 1986 Transcriptional regulation of plasma protein synthesis during inflammation. J Biol Chem 261:8077–8080 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner I 1988 The acute phase response: an overview. Methods Enzymol 163:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M, Inoue M, Wei S, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Kishimoto T, Akira S 1996 STAT3 activation is a critical step in gp130-mediated terminal differentiation and growth arrest of a myeloid cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:3963–3966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Yamanaka Y, Nakae K, Kojima H, Ichiba M, Kiuchi N, Kitaoka T, Fukada T, Hibi M, Hirano T 1996 A central role for Stat3 in IL-6-induced regulation of growth and differentiation in M1 leukemia cells. EMBO J 15:3651–3658 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Pereira AP, Tininini S, Strobl B, Alonzi T, Schlaak JF, Is'harc H, Gesualdo I, Newman SJ, Kerr IM, Poli V 2002 Mutational switch of an IL-6 response to an interferon-γ-like response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:8043–8047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzi T, Maritano D, Gorgoni B, Rizzuto G, Libert C, Poli V 2001 Essential role of STAT3 in the control of the acute-phase response as revealed by inducible gene inactivation [correction of activation] in the liver. Mol Cell Biol 21:1621–1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga S, Terui K, Zhang HQ, Enosawa S, Ogawa W, Inoue H, Okuyama T, Takeda K, Akira S, Ogino T, Irani K, Ozaki M 2003 Stat3 protects against Fas-induced liver injury by redox-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Clin Invest 112:989–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss P, Unger-Smith NE, Lam FS, Hollenberg AN 2009 STAT3 targets the regulatory regions of gluconeogenic genes in vivo. Mol Endocrinol 23:827–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell Jr JE 1995 Maximal activation of transcritpion by STAT1 and STAT3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell 82:241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Kole S, Precht P, Pazin MJ, Bernier M 2009 S-glutathionylation impairs signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation and signaling. Endocrinology 150:1122–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Cherukuri P, Luo J 2005 Activation of Stat3 sequence-specific DNA binding and transcription by p300/CREB-binding protein-mediated acetylation. J Biol Chem 280:11528–11534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer OH, Baus D, Knauer SK, Stein S, Jäger E, Stauber RH, Grez M, Pfitzner E, Heinzel T 2006 Acetylation of Stat1 modulates NF-κB activity. Genes Dev 20:473–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Boldogh I, Brasier AR 2005 STAT3 NH2-terminal acetylation is activated by the hepatic acute-phase response and required for IL-6 induction of angiotensinogen. Gastroenterology 129:1616–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan ZL, Guan YJ, Chatterjee D, Chin YE 2005 Stat3 dimerization regulated by reversible acetylation of a single lysine residue. Science 307:269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Ray S, Brasier AR 2007 The functional role of an interleukin 6-inducible CDK9.STAT3 complex in human γ-fibrinogen gene expression. J Biol Chem 282:37091–37102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Lee C, Hou T, Boldogh I, Brasier AR 2008 Requirement of histone deacetylase1 (HDAC1) in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) nucleocytoplasmic distribution. Nucleic Acids Res 36:4510–4520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demple B, Harrison L 1994 Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu Rev Biochem 63:915–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S, Izumi T, Boldogh I, Bhakat KK, Hill JW, Hazra TK 2002 Choreography of oxidative damage repair in mammalian genomes. Free Radic Biol Med 33:15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi T, Wiederhold LR, Roy G, Roy R, Jaiswal A, Bhakat KK, Mitra S, Hazra TK 2003 Mammalian DNA base excision repair proteins: their interactions and role in repair of oxidative DNA damage. Toxicology 193:43–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman CT, Brasier AR 2001 Role of signal transducers and activators of transcription 1 and 3 in inducible regulation of the human angiotensinogen gene by interleukin-6. Mol Endocrinol 15:441–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Sherman CT, Lu MP, Brasier AR 2002 Angiotensinogen gene expression is dependent on signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-mediated p300/cAMP response element binding protein-binding protein coactivator recruitment and histone acetyltransferase activity. Mol Endocrinol 16:824–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando K, Hirao S, Kabe Y, Ogura Y, Sato I, Yamaguchi Y, Wada T, Handa H 2008 A new APE1/Ref-1-dependent pathway leading to reduction of NF-κB and AP-1, and activation of their DNA-binding activity. Nucleic Acids Res 36:4327–4336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman L, Moorthy NC, Murthy KG, Manley JL, Bustin M, Prives C 1998 High mobility group protein-1 (HMG-1) is a unique activator of p53. Genes Dev 12:462–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziel KA, Campbell CC, Wilson GL, Gillespie MN 2004 Ref-1/Ape is critical for formation of the hypoxia-inducible transcriptional complex on the hypoxic response element of the rat pulmonary artery endothelial cell VEGF gene. FASEB J 18:986–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K, Stark GR, Kerr IM, Darnell Jr JE 1993 A single phospotyrosine residue of Stat91 required for gene activation by interferon-γ. Science 261:1744–1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell Jr JE 1994 Stat3: A STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science 264:95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vascotto C, Cesaratto L, Zeef LA, Deganuto M, D'Ambrosio C, Scaloni A, Romanello M, Damante G, Taglialatela G, Delneri D, Kelley MR, Mitra S, Quadrifoglio F, Tell G 2009 Genome-wide analysis and proteomic studies reveal APE1/Ref-1 multifunctional role in mammalian cells. Proteomics 9:1058–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Brasier AR, Wright KA, Habener JF 1990 The permissive role of glucocorticoids on interleukin-1 stimulation of angiotensinogen gene transcription is mediated by an interaction between inducible enhancers. Mol Cell Biol 10:4389–4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthoudakis S, Smeyne RJ, Wallace JD, Curran T 1996 The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8919–8923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meira LB, Cheo DL, Hammer RE, Burns DK, Reis A, Friedberg EC 1997 Genetic interaction between HAP1/REF-1 and p53. Nat Genet 17:145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Ray S, Lee C, Brasier AR 2008 The STAT3 NH2-terminal domain stabilizes enhanceosome assembly by interacting with the p300 bromodomain. J Biol Chem 283:30725–30734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Snyder M, Levy DE, Zhang JJ 2006 Regulation of Stat3 transcriptional activity by the conserved LPMSP motif for OSM and IL-6 signaling. FEBS Lett 580:5880–5884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SL, Samols D, Sipe J, Kushner I 1992 The acute phase response: overview and evidence of roles for both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 30:133–135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney MM, Parise LV, Lord ST 1996 Dissecting clot retraction and platelet aggregation. Clot retraction does not require an intact fibrinogen γ chain C terminus. J Biol Chem 271:8553–8555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LJ, Robson CN, Black E, Gillespie D, Hickson ID 1993 Identification of residues in the human DNA repair enzyme HAP1 (Ref-1) that are essential for redox regulation of Jun DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol 13:5370–5376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay R, Das S, Maiti AK, Boldogh I, Xie J, Hazra TK, Kohno K, Mitra S, Bhakat KK 2008 Regulatory role of human AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1) in YB-1-mediated activation of the multidrug resistance gene MDR1. Mol Cell Biol 28:7066–7080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakat KK, Mantha AK, Mitra S 2009 Transcriptional regulatory functions of mammalian AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1), an essential multifunctional protein. Antioxid Redox Signal 11:621–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakat KK, Izumi T, Yang SH, Hazra TK, Mitra S 2003 Role of acetylated human AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1) in regulation of the parathyroid hormone gene. EMBO J 22:6299–6309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busso CS, Iwakuma T, Izumi T 2009 Ubiquitination of mammalian AP endonuclease (APE1) regulated by the p53-MDM2 signaling pathway. Oncogene 28:1616–1625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuninger DT, Izumi T, Papaconstantinou J, Mitra S 2002 Human AP-endonuclease 1 and hnRNP-L interact with a nCaRE-like repressor element in the AP-endonuclease 1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res 30:823–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak DE, Tian B, Brasier AR 2005 Two-step cross-linking method for identification of NF-κB gene network by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Biotechniques 39:715–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]