Introduction

Blood flow dynamics play a key role in the development of atherosclerosis,1 arterial aneurysm rupture,2 cardiac remodeling,3 cardiac valve disease4 and other cardiovascular disease. Many investigators have studied the role of different types of flow patterns, and how shear stress affects the behavior of cells comprising blood vessels, such as endothelial and smooth muscle cells.1, 5, 6 Often cell types are isolated and exposed to a single type of flow in an in vitro model such as laminar, to-and-fro, orbital or more complicated patterns. These in vitro studies have led to the identification of several molecular mediators that respond to different flow patterns,7–11 and recently a shear stress receptor for endothelial cells has been identified.12

One limitation of these models is that vascular disease is a complex process, involving multiple cell types and interactions between cells and molecular mediators.13 In vivo, cells are exposed to a combination of flow types throughout the cardiac cycle. Therefore, there is a need to characterize complex patterns of blood flow dynamics in vivo.

Ultrasound has become a popular modality to study cardiovascular disease, and can provide information about hemodynamics, disease severity and progression. This is because it is less expensive than computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), is portable, quick and can provide blood flow velocities and some basic indication as to whether blood flow is laminar or complicated. The major limitation of ultrasound is that the signal-to-noise ratio tends to be low and the quality of the scan is operator dependent.14–16

In contrast, MRA offers several advantages over ultrasound. The quality of the data is less operator dependent, and there is more potential for quantitative information that has not yet been utilized in the field of vascular imaging.17 MRA contains information about both the magnitude and phase of an image, and several modalities are available which have particular applications in vascular imaging such as time-of-flight and phase contrast imaging.18 The major limitation of MRA is signal resolution;19 a voxel size of 1mm3 is considered small. In animal models, where arterial diameters are likely to be smaller that 2mm, a voxel size of 1mm3 allows for only a handful of voxels within the arterial lumen, yielding resolution insufficient to characterize blood flow. In addition, under complicated or turbulent flow conditions, a signal void would likely be created, due to disorganized molecular movement within a given pixel, thereby cancelling out the signal.20

Previous work has shown that radiofrequency coils can be constructed and surgically implanted. The coil enhances the local MR signal, thereby decreasing voxel size.21 In the field of cardiovascular imaging, intravascular coils22 that fit on the tip of a catheter have been described.23, 24 These have the advantage of percutaneous implantation, and have been used to image blood vessel architecture.25 Unfortunately, the presence of the coil within the blood vessel lumen alters blood flow,26 making them impractical for characterization of flow dynamics. Surface coils have also been used to achieve high signal resolution, and then used to study arterial remodeling in atherosclerosis,27 but no description of flow dynamics was obtained.

Therefore, given the quantitative potential of MRA for studying blood flow dynamics, but the limitation of voxel size, we constructed a surgically implantable, extravascular coil. This coil was studied in an animal model of carotid stenosis and used to characterize laminar and complicated blood flow.

Methods

Coil Construction

Rectangular, receive-only coils were constructed using a single loop of copper wire (Figure 1A). The coil was tuned to the Lamour frequency of the magnet, 123.2MHz, and the impedance was matched to 50 ohms. Coils were 4.5cm × 1cm and coated in silicon (MED ADH 4100 RTV, Rhodia Silicones, Ventura CA) to insulate and seal the components from the biological environment (Figure 1B). A small hole was placed in the center of the coil for suture stabilization, so as to ensure alignment with the long axis of the artery following implantation. Coils were connected via a long coaxial cable (Hirose Electric Co. Ltd. Simi Valley, CA) to a custom-made pre-amplifier, which then connected to the amplifier of the MR Scanner.

Figure 1.

Coil construction and implantation. A) Schematic diagram showing the components of our custom-made rectangular, receive-only coil. B) Photograph of the receive-only coil. C) Operative procedure. A stenosis was created in the left carotid artery of the rabbit and gradually adjusted until the flow was reduced by 50%, as assessed by ultrasonic flow probe (left panel; final result middle panel). The coil was then surgically implanted near the stenosed artery (right panel). D) MRA magnitude image showing the coil position. A signal void is created within the volume of the coil body (red arrows). The coaxial cable can be seen as it loops before exiting through the skin (green arrow). The left and right carotid arteries are visible (yellow arrows).

Animal Model

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University. New Zealand White rabbits (3 months old) were raised in pathogen-free conditions (Harlan Sprague Dawley) and housed locally at least 1 week before surgery. Male rabbits were explicitly used because of their smaller dulap in the neck. Anesthesia was induced with Ketamine (35 mg/kg) and Xylazine (5mg/kg), and then maintained with Isoflurane (0.5% – 1% continuous inhalation). Analgesia was provided pre-operatively and at 24 hours postoperatively and thereafter as needed with Carprofen (5mg/kg). All surgery was performed in a sterile operating environment. A midline incision was made in the anterior neck, the strap muscles were divided along their fibers, and the left carotid artery was isolated.

Blood flow was measured by placing an ultrasonic flow probe (Transonic Flowprobe, Ithaca, NY) around the adventitia of the artery. This was performed in order to verify that a stenosis had been created, and to control the extent of luminal narrowing. A stenosis was created in the mid portion of the left carotid artery (Figure 1C) by tightening a 3.0 silk suture around the adventitia until the flow was reduced by 50%. Flow was measured again at 3 minutes to ensure that the suture had not loosened, and that the flow was stably reduced. The coil was aligned in the direction of the long axis of the carotid artery, and then sutured to the strap muscles. The midpoint of the coil was placed over the stenosis to allow imaging proximal and distal to the stenosis. The coaxial cable was tunneled under the skin, and made to exit at the posterior neck. Excess cable was looped under the skin so that the connector visible at the skin was as short as possible to prevent detachment by the rabbit. The strap muscles and skin were closed with absorbable suture. No heparin was used during the procedure.

Ultrasound Stenosis Verification

Ultrasound evaluation (Visualsonics Vevo770, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) of both the control (contralateral) and stenosed carotid arteries was performed on the first post-operative day. We used a high resolution ultrasound (down to 30 microns) specifically designed for analysis of blood flow in small animals. Images were acquired with a linear array scanhead, probe frequency of 30 MHz and focal length of 6 mm. In pulsed-wave mode, velocity measurements were obtained at an angle of 60 – 80 degrees. Color Doppler was not used. Ultrasound measurements were obtained by 2 physicians trained in vascular ultrasound for small animal models. Ultrasound images were also reviewed by a board-certified vascular surgeon. No anesthesia was used for this measurement, as it is noninvasive and the rabbit was able to maintain a stable, comfortable position. Ultrasound evaluation was performed in order to confirm that the stenosis was still present. In addition, diameters and blood flow velocities in the control artery and in the proximal, in-stenosis and distal portions of the stenosed artery were obtained. Identification of arterial anatomy was confirmed by incompressibility of the vessel, and the presence of intraluminal velocity waveforms consistent with arterial blood flow.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

MR scanning was performed on the first post-operative day, within 4 hours of ultrasound imaging. Anesthesia was induced with Ketamine (35 mg/kg) and Xylazine (5mg/kg) to ensure that the rabbit maintained a stable position during MR scanning. No isoflurane or repeat dosing of anesthesia was needed. All examinations were performed on a 3T MR scanner (Siemens 3T Magnetom Trio, Malvern, PA). Images were obtained and interpreted by a certified MR technologist and a faculty member with expertise in cardio-vascular MR. A time-of-flight sequence was first employed to locate the 3-dimensional morphology of the stenosed and the control artery (slice thickness 1mm, TR/TE 23/3.6ms, nex=2, in-plane resolution 0.7 × 0.5mm and flip angle 25 degrees). Multiple slices oriented axial to the stenosed artery were then prescribed at regular intervals, sampling the proximal, in-stenosis and distal regions. A non-gated, free-breathing 2-dimensional phase contrast imaging sequence was then employed to acquire the magnitude and velocity-encoded phase images at each slice location. Imaging parameters were as follows: imaging matrix = 576 × 576 voxels, imaging field of view = 5.76 × 5.76 cm, velocity encoding = 30 cm/s, velocity sensitivity direction = along the long axis of the vessel, TR = 40 ms, TE = 10 ms, signal averaging over 9 acquisitions, flip angle 15 degrees, slice thickness 7mm, in-plane resolution 0.6 × 0.3mm, TR/TE: 150*13ms and nex=3. This allowed for a scan time of approximately 3 minutes per slice.

Signal Processing

The Dicom images were extracted from the MR scanner, and subsequent signal processing was performed using the Matlab software package (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Boundaries of the stenosed and control arteries were manually contoured from the magnitude images, and velocity profiles within the contours were obtained from the corresponding locations in the phase images.

For flow in a cylindrical pipe, assuming no-slip conditions along the wall, the velocity profile can be estimated by:

| Eq (1) |

where U is velocity, μ is viscosity, P is pressure, ρ is density, g is acceleration due to gravity, z is height, R is the radius of the pipe and r is the radial distance from the center of the pipe. Assuming that 1/4μ [−d/dx (P+ρgz)] is constant, this equation can be reduced to:

| Eq (2) |

Therefore, the velocity profile for laminar flow in a cylindrical pipe depends only on the radial distance from the center of the pipe, with the maximum velocity (c) occurring at the center of the pipe and velocities of zero along the pipe wall.

All velocity profiles were fit to this model of laminar flow by estimating the parameter (c) using ordinary least squares. The variance of the parameter estimation was calculated from the parameter covariance matrix to determine the goodness of the fit. Velocity profile fits with small variances were considered to be laminar, and complicated flow was defined as those fits with larger variances.

Diameters and average velocities obtained from ultrasound versus MRA are presented as the mean ± standard error of mean and different groups were compared by using the paired t-test (Statview 5.0; SAS institute, Inc, Cary, NC). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Coils Improve MRA Signal Resolution

To examine blood flow dynamics using MRA, a total of 6 carotid arteries were analyzed (3 control, 3 with surgical stenosis) in 3 rabbits. Blood flow was determined using an ultrasonic probe, and was 24.7 ± 2.6 ml/min prior to stenosis creation and reduced to 12.0 ± 1.7 ml/min by the stenosis (n=3).

In order to improve MRA signal resolution, extravascular coils were surgically implanted near the carotid artery. An MRA cross-section of the rabbit neck is shown in Figure 1D. A signal void is created within the boundaries of the coil (red arrows) and the wire leading to the connector can be seen as it loops before exiting the skin (green arrow). The left and right carotid arteries are visible (yellow arrows). Using this technique, MRA voxel size was reduced to 0.1mm x 0.1mm x 5mm. This allowed for approximately 200–300 voxels within the cross-sectional area of the carotid artery (Table I). Resolution of the Vevo 770 ultrasound is 0.03mm x 0.03mm.

Table I.

Ultrasound versus MRI Measurements

| Control | Proximal | In Stenosis | Distal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter on Ultrasound (mm) | 1.9 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 1.49 ± 0.2 |

| Diameter on MRI (mm) | 1.9 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.10* | 1.59 ± 0.1 |

| Number of Voxels on MRI | 318 ± 22 | 264 ± 22 | 110 ± 23 | 207 ± 28 |

| Average Velocity by Ultrasound (cm/s) | 1.5 ± 0.06 | 2.25 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| Average Velocity by MRI (cm/s) | 3.4 ± 0.30 * | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.9 * | 3.4 ± 0.4 * |

| Maximum Velocity by MRI (cm/s) | 14.2 ± 1.4 | 15.3 ± 4.1 | 16.8 ± 4.7 | 17.3 ±2.3 |

p < 0.05

Comparison of Ultrasound and MRA Measurements

In order to compare ultrasound measurements to MRA, carotid arteries were analyzed using both modalities. Figure 2A shows an ultrasound image of the stenosed carotid artery. The area of stenosis is marked with a yellow arrow. Figure 2B shows the same artery imaged with time-of-flight MRA, which was employed to initially locate the artery and the stenosis. The large bright area is an artifact created by the coil. The artery also appears bright close to the coil, due to signal enhancement in that area. The area of stenosis can be clearly seen, and is marked with a yellow arrow. Time-of-flight imaging was used to locate the area of stenosis so that imaging could be performed on multiple axial slices proximal, within and distal to the stenosis. Representative locations are indicated by orange lines overlaid on the image.

Figure 2.

Image localization of the carotid stenosis. A) Ultrasound image showing the area of stenosis (yellow arrow). B) Time-of-Flight MRA image. The large bright area is an artifact caused by the coil. The stenosed artery can be clearly seen, and is bright in the region of coil enhancement. The stenosis is visible (yellow arrow). Orange lines indicate representative locations of imaging slices.

Blood flow velocities were determined using B-mode ultrasound (Figure 3). The blue dotted line indicates the long axis of the vessel that was assigned to the artery image. When the artery was aligned such that blood was flowing somewhat into the probe, the velocity waveforms are of higher quality (Figure 3A) than when the blood flow runs completely perpendicular to the probe (Figure 3B). In addition, the ultrasound machine would not allow the user to choose an arterial angle that is completely flat; note that the measured long axis, as set by the blue dotted line, cannot be made to line up with the long axis of the artery (Figure 3B). In small animals, the carotid artery often runs relatively close and parallel to the skin. Thus, it is difficult for the ultrasound operator to achieve an optimal artery-probe orientation.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound imaging is operator dependent. A) Left panel: Image of the carotid artery, showing the chosen vessel long axis orientation (blue dotted line) and the calipers delineating the region of velocity measurement (red line). Right panel: B-mode ultrasound velocity waveform. B) Left panel: Blood is flowing perpendicular to the ultrasound probe. Right panel: The resulting B-mode velocity waveform is poor.

Table I compares measurements obtained from ultrasound and MRA analysis. In general, there was good agreement in vessel diameter measurements. However, within the stenosis, there was a statistically significant difference between ultrasound and MRA. At the stenosis, it was difficult to determine the vessel boundaries using MRA, and this resulted in the diameters being slightly overestimated.

Only mean, and not maximum, velocities were obtained with ultrasound since the calipers defining the area of velocity estimation span much of the luminal cross-section, and therefore represent an averaged velocity. In contrast, a velocity measurement was calculated for each MRA voxel using phase-contrast, which yields 200–300 velocity measurements per cross-section. Therefore, both a maximum and an average velocity could be accurately calculated for each arterial cross-section using MRA.

Ultrasound is user-dependent, but on average the time required to locate the carotid artery was 15 minutes and 5 velocity measurements could be obtained within 1 minute. Using MR, locating the carotid artery and orienting the scan axis could be accomplished in 15 minutes. Each slice required 3 minutes of scan time and produced 200–300 velocity measurements.

In general, there was poor agreement between ultrasound and MRA mean flow velocities. Calculations were significantly different for the control vessels, and the distal portion of the stenosed vessels. Within the stenosis, mean velocity calculations were lower using MRA compared to ultrasound (4.3 cm/s on ultrasound versus 2.1 cm/s on MRA).

Characterization of Velocity Profiles Using MRA

In order to characterize velocity profiles, phase-contrast MRA was used to image both the control and stenosed carotid arteries. The stenosis was initially located by time-of-flight imaging; then multiple magnitude and phase-contrast images were obtained proximal, within and distal to the stenosis. Figure 4 shows the magnitude and phase contrast images at 5 different locations: downstream, just distal, within, just proximal and upstream from the stenosis. Yellow arrows point to the control artery and red arrows point to the stenosed artery. The dark circular regions near the stenosed artery in panels B, C and D are residual air bubbles from surgery.

Figure 4.

MRA velocity profiles. Shown in left to right columns are: MRA magnitude images, MRA phase-contrast images, schematic diagram of vessel image location relative to the stenosis, 2-dimensional velocity profiles of the control artery, 3-dimensional velocity profiles of the stenosed artery and 2-dimensional velocity profiles of the stenosed artery. Yellow arrows indicate the control vessel and red arrows indicate the stenosed vessel. Image locations are as follows: A) Downstream from the stenosis. B) Immediately distal to the stenosis. C) Within the stenosis. D) Immediately proximal to the stenosis. E) Upstream from the stenosis.

Corresponding velocity profiles were obtained from the phase-contrast images. A 2-dimensional representation of the control artery velocity profile, where color gradation represents velocity magnitude in the direction of the long axis of the vessel is shown (Figure 4, page 2, column 1). In control vessels, velocity profiles resemble laminar flow, where velocity is near zero at the vessel wall and concentrically increases, reaching a maximum in the center of the vessel.

3-dimensional velocity profiles are shown for the stenosed artery (Figure 4, page 2, column 2). Velocity magnitude in the direction of the vessel long axis is represented by both height and color gradation. 2-dimensional velocity profiles are shown for the same vessel segments (Figure 4, page 2, column 3), and do not contain any additional information, but simply represent a top-down view of the 3-dimensional velocity profiles and are provided for comparison with the control velocity profiles. In the stenosed vessel, flow appears to be laminar upstream from the stenosis. Flow becomes complicated just proximal to the stenosis, becomes more laminar within the stenosis, then becomes complicated just distal to the stenosis. Additionally, there are regions of backflow (negative velocities) that can be seen in the 3-dimensional images. Downstream from the stenosis, flow returns to a laminar profile.

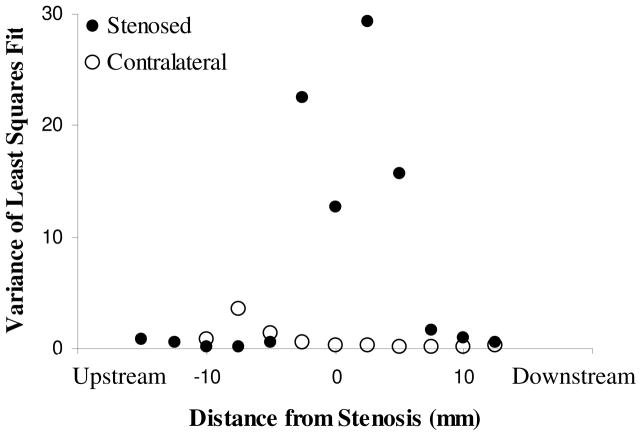

In order to characterize blood flow dynamics, velocity profiles were fit to a laminar flow model as described in equation 2. The variance of the parameter estimation was used as a metric of complicated flow, with small variances indicating a laminar profile and larger variances indicated a more complicated flow profile or deviation from laminar flow (Figure 5). The control artery exhibits laminar velocity profiles in all areas of the vessel, as evidenced by small variances in the model fit. In the stenosed artery, upstream locations yielded small variances. Before entering the stenosis, blood flow becomes more complicated (higher variances), then within the stenosis the variance decreased. Immediately distal to the stenosis, variance increased. Downstream from the stenosis, blood flow returns to a laminar profile.

Figure 5.

Variance of the parameter fit as a function of proximity to the stenosis. Small variances indicate that the velocity profile was well described by a laminar model; large variances indicate more complicated flow. In the control artery and in upstream and downstream locations of the stenosed artery, flow is well approximated by a laminar model. Immediately proximal to the stenosis, flow becomes complicated, followed by some reorganization within the stenosis. Immediately distal to the stenosis, flow is again complicated. Figure shown is representative (n=3).

Discussion

We successfully demonstrate that surgically implantable coils can be used to decrease MRA voxel size, thereby allowing sufficient image resolution to characterize arterial blood flow in a small vessel animal model. In this study, we achieve a voxel size of 0.1mm x 0.1mm x 5mm. Recent studies have achieved a voxel edge of 0.6mm using a 7T scanner, 28 and voxel size of 0.66 × 0.76 × 5.6–6.4 mm using a 3T scanner. 29 Blood flow velocity profiles were constructed from MRA phase-contrast images, and laminar flow could be quantitatively distinguished from more complicated flow by fitting these profiles to a laminar flow model. In addition, there was a consistent pattern of conversion from laminar to complicated flow proximal to the arterial stenosis, and a return to laminar flow downstream from the stenosis.

MRA Coils

The notion of using MR coils to increase signal resolution has been well described in the literature, and several designs have been implemented in vascular imaging. The cylindrical meanderline (zig-zag) coil design has been used to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio for carotid plaques. It can also be expanded against the walls of the artery, thereby stabilizing the coil against the pulsatile blood flow and minimizing motion artifacts. However, it acts to reduce the intensity of the blood signal, and as an intravascular coil, alters blood flow dynamics.30 A two-element, catheter-based phased array coil has also been described that both provides for device tracking and vessel wall imaging. The device consisted of 2 solenoid coils, wound in opposite directions, mounted collinearly on an angiographic catheter. However, it is also an intravascular coil, and alters blood flow dynamics.25 A high-temperature superconducting surface coil has been described that achieved a voxel size of 0.06 mm x 0.06 mm x 0.1mm and was used to analyze atheromatous coronary arteries ex vivo. However, this was a histological study, and no information regarding blood flow dynamics was obtained.21 Similarly, the progress of atherosclerotic lesions in the carotid artery of rabbits was studied using a customized surface coil, but did not evaluate blood flow.27

Limitations of MRA

MRA is more financially costly than ultrasound. In addition, initially locating the carotid artery is difficult, as it is a relatively small structure within the complex anatomy of the neck. Once the artery has been identified, a skilled MR technician must be able to align the scanning axis such that multiple cross-sections of the artery can be obtained sequentially. Therefore, replication of this technique requires an MR technician with experience in vascular imaging. We performed scanning on a standard 3T MR machine, similar to those used in clinical practice. The advantage of the coil is that fine resolution can be obtained on a clinical-grade scanner, and does not require a larger magnet.

Ultrasound versus MRA

Finer Spatial Resolution does Not Imply Finer Velocity Resolution

Ultrasound has been a popular imaging modality in clinical cardiac and peripheral vascular evaluation, primarily because it is portable and less costly than MRA. However, it has low signal to noise ratio, is operator-dependent and does not have the quantitative potential of MRA.17 In this study, we observed that ultrasound had better spatial resolution (voxel edge = 0.03mm) compared to coil-assisted MRA (voxel edge = 0.1mm). This image resolution may explain the discrepancy in measuring in-stenosis arterial diameter, and why in-stenosis diameters were overestimated using MRA in this study. However, despite finer spatial resolution, ultrasound did not achieve finer velocity measurement. In ultrasound, velocity measurement is noisy and must be obtained over a large area of voxels. Using phase-contrast MRA, a velocity measurement was obtained for each voxel, resulting in hundreds of velocity measurements within an arterial cross-section.

Differences in anesthesia may have been an additional factor that contributed to the poor agreement that we observed between ultrasound and MRA mean velocity measurement. Rabbits were not anesthetized during ultrasound measurement, but were anesthetized during MRA scanning. Anesthetics can often be associated with a baroreflex-mediated increase in heart rate. Furthermore, it is known that many anesthetics, including isoflurane, have significant vasodilating effects. All of these factors could have influenced the findings during MRA.

Additionally, ultrasound velocity measurement is very operator dependent, and critically depends on the probe orientation relative to the vessel. Ultrasound uses the Doppler shift to calculate blood flow velocity:

| Eq (3) |

where v is the velocity of the blood, f is the Doppler shift frequency, c is the acoustic velocity in blood (1.54 × 105 cm/s), Fo is the transmitted frequency and θ is the Doppler angle.31 Therefore, the most accurate measurements are obtained when blood flow is moving directly into the probe (θ = 0°), and inaccurate measurements result when the flow runs perpendicular to the probe (θ = 90°). In small animals, the carotid artery often runs very close and parallel to the skin, making it difficult to orient the probe in a favorable configuration relative to the artery. MRA does not have this limitation.

Future Directions

This study provides promising data to suggest that blood flow dynamics can be quantitatively studied using MRA, but there are many potential ways to improve this technique. During data collection, no cardiac gating was performed. The pattern and speed of blood flow is likely to change within the cardiac cycle, and velocity profiles could be obtained and compared at different time-points along the electrocardiogram. This may further delineate what percentage of time, and to what extent complicated flow is present within the vessel, and whether the time-course or frequency component of complicated flow is important for arterial remodeling, molecular expression and atherogenesis. In addition, respiratory gating may also improve data acquisition.

This study only analyzed the velocity profile in 1 dimension, in the long-axis of the vessel. If the velocity profile was obtained in 3 dimensions, then a 3-dimensional velocity vector map could be constructed. There are several known mathematical operators (such as the divergence and curl) that could then be used to quantify the behavior of the velocity profile and be used to delineate interesting features. Furthermore, flow was only characterized as laminar or non-laminar. More sophisticated signal processing could be performed to delineate important flow dynamics.

A voxel size of 0.1 × 0.1 × 5mm was obtained. The cost of a smaller voxel size is a decrease in the signal strength within the voxel, resulting in a smaller signal-to-noise ratio. Future work may focus on further decreasing the voxel size, particularly in the third dimension. However, the current voxel size is sufficient for studying arterial dynamics in very small vessels, and this technique may be expanded to even smaller animal models. In particular, mouse models are extremely useful, as several genetic mutations that influence arterial development and behavior have been described.32, 33

Ultimately, wall shear stress is the result of blood flow against the arterial wall, and has been shown to influence endothelial9, 12 and smooth muscle cell behavior.5, 11 Previous investigators have used computational fluid dynamics to estimate wall shear stress in blood vessels using MRI,34 and this technique could be combined with coil-assisted imaging to allow calculation of wall shear stress in small animal models.

Finally, wireless coils have been described that inductively couple their signal to MR surface coils.35 This modification would eliminate a wire connection to the scanner, and would be useful for long-term animal studies, in which an animal may be bothered by the external location of the connector.

Conclusions

Implantable, extra-vascular coils can enable small enough MRA voxel sizes to reproducibly calculate complex velocity profiles under both laminar and complicated flow in a small animal model. This technique may be applied to study blood flow dynamics of vessel remodeling and atherogenesis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the NIH and the American Vascular Association William J. von Liebig Award

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Davies PF, Spaan JA, Krams R. Shear stress biology of the endothelium. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33(12):1714–8. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaguchi R, Ujiie H, Haida S, et al. Velocity profile and wall shear stress of saccular aneurysms at the anterior communicating artery. Heart Vessels. 2008;23(1):60–6. doi: 10.1007/s00380-007-0996-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng A, Langer F, Nguyen TC, et al. Transmural left ventricular shear strain alterations adjacent to and remote from infarcted myocardium. J Heart Valve Dis. 2006;15 (2):209–18. discussion 218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher JT, Simmons CA, Warnock JN. Mechanobiology of the aortic heart valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2008;17(1):62–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald TN, Shepherd BR, Asada H, et al. Laminar shear stress stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis via the akt pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jcp.21404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helmlinger G, Geiger RV, Schreck S, Nerem RM. Effects of pulsatile flow on cultured vascular endothelial cell morphology. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113(2):123–31. doi: 10.1115/1.2891226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dardik A, Chen L, Frattini J, et al. Differential effects of orbital and laminar shear stress on endothelial cells. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(5):869–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimmeler S, Assmus B, Hermann C, et al. Fluid shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of akt in human endothelial cells: Involvement in suppression of apoptosis. Circ Res. 1998;83(3):334–41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadohama T, Nishimura K, Hoshino Y, et al. Effects of different types of fluid shear stress on endothelial cell proliferation and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212(1):244–51. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. Jama. 1999;282(21):2035–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueba H, Kawakami M, Yaginuma T. Shear stress as an inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Role of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and tissue-type plasminogen activator. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(8):1512–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.8.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, et al. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437(7057):426–31. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rader DJ, Daugherty A. Translating molecular discoveries into new therapies for atherosclerosis. Nature. 2008;451(7181):904–13. doi: 10.1038/nature06796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaitini D, Soudack M. Diagnosing carotid stenosis by doppler sonography: State of the art. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24(8):1127–36. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.8.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaff MR. Diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease: Utility of the vascular laboratory. Clin Cornerstone. 2002;4(5):16–25. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(02)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reid AW, Reid DB, Roditi GH. Vascular imaging: An unparalleled decade. J Endovasc Ther. 2004;11(Suppl 2):II163–79. doi: 10.1177/15266028040110S606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald TN, Muto A, Kudo FA, et al. Emerging vascular applications of magnetic resonance imaging: A picture is worth more than a thousand words. Vascular. 2006;14(6):366–71. doi: 10.2310/6670.2006.00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price RR, Creasy JL, Lorenz CH, Partain CL. Magnetic resonance angiography techniques. Invest Radiol. 1992;27(Suppl 2):S27–32. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199212002-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stehning C, Boernert P, Nehrke K. Advances in coronary mra from vessel wall to whole heart imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2007;6(3):157–70. doi: 10.2463/mrms.6.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozenshtein A, Boxt LM. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of patients with valvular heart disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2000;15(4):252–64. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poirier-Quinot M, Ginefri JC, Ledru F, et al. Preliminary ex vivo 3d microscopy of coronary arteries using a standard 1.5 t mri scanner and a superconducting rf coil. Magma. 2005;18(2):89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10334-004-0097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin AJ, Pleewes DB, Henkelman RM. Mr imaging of blood vessels with intravascular coil. J Mag Res Imag. 1992;2:421–429. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880020411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chwialkowski M, McDonald G, Heifer D, et al. Design and performance of catheter coils in vascular mr imaging. Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuehlsdorff S, Umathum R, Volz S, et al. Mr coil design for simultaneous tip tracking and curvature delineation of a catheter. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(1):214–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillenbrand CM, Elgort DR, Wong EY, et al. Active device tracking and high-resolution intravascular mri using a novel catheter-based, opposed-solenoid phased array coil. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(4):668–75. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volz S, Zuehlsdorff S, Umathum R, et al. Semiquantitative fast flow velocity measurements using catheter coils with a limited sensitivity profile. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):575–81. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronald JA, Walcarius R, Robinson JF, et al. Mri of early- and late-stage arterial remodeling in a low-level cholesterol-fed rabbit model of atherosclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(4):1010–9. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraff O, Theysohn JM, Maderwald S, et al. High-resolution mri of the human parotid gland and duct at 7 tesla. Invest Radiol. 2009 doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181b4c0cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amano Y, Takahama K, Kumita S. Noncontrast-enhanced three-dimensional magnetic resonance aortography of the thorax at 3.0 t using respiratory-compensated t1-weighted k-space segmented gradient-echo imaging with radial data sampling: Preliminary study. Invest Radiol. 2009 doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181b4c0ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrar CT, Wedeen VJ, Ackerman JL. Cylindrical meanderline radiofrequency coil for intravascular magnetic resonance studies of atherosclerotic plaque. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(1):226–30. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Http://www.Ob-ultrasound.Net/doppler_a.Html. [cited.

- 32.Nose M. A proposal concept of a polygene network in systemic vasculitis: Lessons from mrl mouse models. Allergol Int. 2007;56(2):79–86. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.r-04-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yutzey KE, Robbins J. Principles of genetic murine models for cardiac disease. Circulation. 2007;115(6):792–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.682534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida K, Nagao T, Okada K, et al. Development of a system for measuring wall shear stress in blood vessels using magnetic resonance imaging and computational fluid dynamics. Igaku Butsuri. 2008;27(3):136–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quick HH, Zenge MO, Kuehl H, et al. Interventional magnetic resonance angiography with no strings attached: Wireless active catheter visualization. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(2):446–55. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]