Abstract

The Fox proteins are a family of regulators that control the alternative splicing of many exons in neurons, muscle, and other tissues. Each of the three mammalian paralogs, Fox-1 (A2BP1), Fox-2 (RBM9), and Fox-3 (HRNBP3), produces proteins with a single RNA-binding domain (RRM) flanked by N- and C-terminal domains that are highly diversified through the use of alternative promoters and alternative splicing patterns. These genes also express protein isoforms lacking the second half of the RRM (FoxΔRRM), due to the skipping of a highly conserved 93-nt exon. Fox binding elements overlap the splice sites of these exons in Fox-1 and Fox-2, and the Fox proteins themselves inhibit exon inclusion. Unlike other cases of splicing autoregulation by RNA-binding proteins, skipping the RRM exon creates an in-frame deletion in the mRNA to produce a stable protein. These FoxΔRRM isoforms expressed from cDNA exhibit highly reduced binding to RNA in vivo. However, we show that they can act as repressors of Fox-dependent splicing, presumably by competing with full-length Fox isoforms for interaction with other splicing factors. Interestingly, the Drosophila Fox homolog contains a nearly identical exon in its RRM domain that also has flanking Fox-binding sites. Thus, rather than autoregulation of splicing controlling the abundance of the regulator, the Fox proteins use a highly conserved mechanism of splicing autoregulation to control production of a dominant negative isoform.

Keywords: Fox, A2BP1, RBM9, HRNBP3, alternative splicing, autoregulation

INTRODUCTION

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing is a key mechanism of genetic regulation that controls the production of many tissue-specific proteins. Many proteins that regulate alternative splicing have been identified. One particularly interesting group of regulators is the Fox family of splicing factors that are related to the feminizing on X (Fox) gene product of C. elegans (Hodgkin et al. 1994; Nicoll et al. 1997). These proteins each contain a single highly conserved RNA recognition motif (RRM) that binds the sequence (U)GCAUG (Jin et al. 2003; Auweter et al. 2006; Ponthier et al. 2006; Yeo et al. 2009). This element serves an important role in controlling the splicing of many alternative exons (Black 1992; Huh and Hynes 1994; Kawamoto 1996; Del Gatto et al. 1997; Hedjran et al. 1997; Modafferi and Black 1997; Lim and Sharp 1998; Deguillien et al. 2001; Baraniak et al. 2006). The Fox proteins typically act as splicing activators when bound downstream of an alternative exon, or as silencers when bound upstream (Underwood et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2008; Yeo et al. 2009). However, exons can contain Fox elements upstream, downstream, and within the exon itself, and it is often not possible to predict the direction of Fox dependent splicing regulation (Tang et al. 2009).

In mammals there are three Fox paralogs: Fox-1 (Ataxin2-binding protein 1, A2BP1), Fox-2 (RNA-binding motif 9, RBM9), and Fox-3 (hexaribonucleotide-binding protein 3, HRNBP3, NeuN) (Shibata et al. 2000; Lieberman et al. 2001; McKee et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2009). Fox-1 is expressed in neurons and both skeletal and cardiac muscle cells, and Fox-3 has only been observed in neurons (Kiehl et al. 2001; McKee et al. 2005; Underwood et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2009; Tang et al. 2009). Fox-2 is also expressed in neurons and muscle but has a broader expression pattern, being observed in stem cells, hematopoetic cells, and in the embryo (Underwood et al. 2005; Baraniak et al. 2006; Ponthier et al. 2006; Yeo et al. 2009).

The mammalian fox genes are highly complex, using multiple promoters, alternative exons, and alternative splice sites to produce complex sets of proteins with differing N- and C-terminal domains, and differing subcellular distributions. How these multiple Fox paralogs and isoforms vary in activity is only beginning to be defined (Nakahata and Kawamoto 2005; Yang et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2009). The multiple promoters of Fox-1 and Fox-2 presumably drive their expression in different cellular contexts, but their tissue specificity is not well characterized. The choice of promoter can also change the N-terminal residues of the protein and presumably its activity. Changes in the splicing of the C-terminal domains leading to changes in the nucleo/cytoplasmic distribution of the proteins can be induced by extracellular stimuli, such as depolarization or CaM kinase signaling (Nakahata and Kawamoto 2005; Lee et al. 2009). There are also Fox-1 and Fox-2 isoforms lacking full-length RRM due to skipping of an alternative exon (FoxΔRRM). Fox-1 and Fox-2 ΔRRM are found in the muscle and heart (Nakahata and Kawamoto 2005; Yang et al. 2008). The alternative RRM exon of Fox-2 is repressed by full-length Fox-2 protein expression in T Rex-293 cells, demonstrating a mechanism of Fox-2 autoregulation (Baraniak et al. 2006).

The Fox-1 gene is unusually large, extending over 2 megabases of DNA. Several human mutations have mapped to this locus, with patients exhibiting severe neurodevelopmental phenotypes, including mental retardation, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder (Bhalla et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2007; Sebat et al. 2007). In other studies, Fox proteins have been shown to interact with Ataxin1 and Ataxin2, proteins mutated in spinal cerebellar ataxia types 1 and 2 (Shibata et al. 2000; Lim et al. 2006). In studying the involvement of the Fox proteins in neurological disease, it will be important to identify the exact isoforms expressed in each cell type.

Here, we further characterize the FoxΔRRM isoforms. We found that Fox-1, Fox-2, and Fox-3 can all produce these isoforms due to the skipping of a conserved alternative exon. The alternative RRM exon of Fox-1, but not Fox-3, is flanked by UGCAUG elements at identical positions with those of the Fox-2 exon. We show that the FoxΔRRM proteins have highly reduced RNA-binding activity, but are not inactive in splicing. These isoforms act in a dominant negative manner to repress the effect of the RRM-containing Fox proteins on splicing activation. Thus, overall cellular Fox activity can be autoregulated by the Fox proteins themselves through the production of an antagonistic Fox isoform.

RESULTS

In analyzing Fox gene expression, we initially determined the expression of Fox isoforms carrying the first exons defined by the multiple alternative promoters in the mouse (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1). Using RNA from cortex, striatum, cerebellum, heart, and skeletal muscle, we performed real-time PCR of putative 5′ exons identified in sequence databases. We found that these 5′ terminal exons (and presumably promoters) are highly tissue specific in their expression. All three genes have 5′ terminal exons that are broadly expressed in brain (e.g., Fox-1 E1B and E1D.1, Fox-2 E1D and E1F, Fox-3 E1C), and others that are restricted to cerebellum (Fox-1 E1C, Fox-2 E1A, Fox-3 E1A, and E1B). Fox-1 exon 1E is expressed in both heart and muscle, but not in brain. We also found Fox-2 isoforms that are specific to heart (E1E) and broadly expressed across the brain and heart (E1G). None of the identified Fox-2 first exons seem to be highly expressed in skeletal muscle, where the protein is known to be expressed. Although Fox-2 isoforms bearing exons 1E and 1F have been detected by RT-PCR and 5′ RACE in mouse skeletal muscle, their levels are not known (Yang et al. 2008). Thus, predominant 5′ terminal exon for the Fox-2 muscle isoforms is not clear. Similarly, the promoter driving Fox-2 expression in stem cells and other cell types is not yet known. Fox-2 isoforms bearing exons 1A and 1F were detected in murine erythroleukemia cells (MELC), where the E1A isoform increased during MELC differentiation, while E1F decreased (Yang et al. 2008). Three Fox-3 promoters were either broadly expressed in brain or specific to cerebellum and can account for all known Fox-3 expression. Fox-1 exon 1E, Fox-2 exon 1A, and Fox 2 exon 1F each bear an in-frame initiation codon and can encode unique N-terminal peptides. The Fox isoforms containing other first exons may use start codons in Fox-1 exon 7, Fox-1 exon 8, Fox-2 exon-3, and Fox-3 exon 5. Thus, the choice of transcriptional initiation site will affect the structure and potential activity of the protein product (Yang et al. 2008).

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of the mouse Fox genes. (A) The exons are shown as boxes. The coding sequence is shown in light gray, and the alternative in-frame start codons are indicated. The dark-gray box represents the alternative exon encoding the second half of the RRM domain. The exon annotation of Fox-1 and Fox-2 is as described for the human genes (Underwood et al. 2005). Exons 1C.1 and 1D.1 of Fox-1 derive from mouse-specific promoters. Alternative exons B40, M43, and A53 (Nakahata and Kawamoto 2005) and the FAPY C-terminal splice isoforms are also indicated. Fox-2 exon 13 (dashed box) is seen in human but not found in mice. The tissue specificity of the mouse Fox first exons is indicated below. The relative expression of these exons in mouse brain, heart, and skeletal muscle are compared in Supplemental Figure S1. Alignment of human and mouse alternative Fox RRM exons, the corresponding chick, frog, fish, and fly Fox exons, and the flanking splice sites (B). The sequences are grouped according to their similarity to the human Fox genes. The corresponding protein coding regions of the worm Fox genes are shown below. The exon and the UGCAUG elements are marked by open and gray boxes as indicated.

Although the N- and C-terminal domains of the Fox proteins are variable between different genes and different isoforms, the central RNA-binding domain is quite constant. This RRM motif exhibits a remarkably high level of conservation from worms to mammals, presumably in part to preserve its binding to the UGCAUG RNA element (Fig. 1B). In addition to the near constant peptide sequence of this domain, the genomic structure of the RRM of all Fox genes from Drosophila to mammals is always split into four conserved exons (Fig. 1A,B). The third RRM exon of each of the human and mouse Fox genes shows alternative splicing in EST databases (Fig. 1A,B, exon 11 of Fox-1, exon 6 of Fox-2, and exon 8 of Fox-3; data not shown). This exon is 93-nt long and its skipping would create an internal in-frame deletion of critical portions of the RNA-binding domain and presumably alter Fox protein function (Baraniak et al. 2006).

If the skipping of the RRM exon occurred in a significant fraction of any of the Fox genes transcripts, it would have important effects on Fox activity. We examined splicing of the alternative RRM exon for each of the Fox genes in mouse brain and muscle (Fig. 2A). In heart and muscle, exon 11 is skipped in 26.3% and 13.6% of Fox-1 transcripts, respectively. In skeletal muscle, 45% of the Fox-2 message excludes the equivalent exon 6, in agreement with an earlier analysis (Nakahata and Kawamoto 2005). This Fox-2 exon 6 excluded transcript is also abundant in cerebellum and heart (∼20% of the Fox-2 transcript), and less abundant, but still easily detectible, in striatum and cortex (8%–9%). Fox-3 is not expressed in muscle and heart, and in brain, only a very minor fraction of the Fox-3 mRNA lacks exon 8.

FIGURE 2.

Fox alternative RRM exon splicing in adult mouse. (A) The inclusion/skipping of Fox-1 exon 11, Fox-2 exon 6, and Fox-3 exon 8 in adult cerebellum, cortex, striatum, heart, and muscle was studied by RT-PCR. The bands marked by an asterisk represent incompletely denatured PCR product. Fox-2 exon 6 skipping is induced in differentiating C2C12. (B) Mouse myoblastoma C2C12 were stimulated to form myotubes in medium containing 2% horse serum. Cells were harvested 0, 2, 4, and 6 d after starting the differentiation. The splicing of Fox-2 exon 6 was studied by RT-PCR. Analysis of the muscle Fox proteins by Western blotting. (C) Protein lysate from purified mouse skeletal muscle nuclei were probed by antibodies specifically recognizing all Fox proteins with an intact RRM (lane αFoxRRM; see also Fig. 5B), Fox-1-specific antibody (lane αFox-1), and anti-Fox-2 antibody (lane αFox-2). The Fox-2ΔE6 isoforms (right) are detected only by the anti-Fox-2, but not by the anti-RRM or the anti-Fox-1 antibodies.

Among the Fox genes, Fox-2 expresses the most significant amounts of a FoxΔRRM isoform, and this is particularly abundant in muscle. Examining the alternative splicing of Fox-2 exon 6 in the C2C12 mouse myoblast cell line, we found that this exon is dynamically regulated during muscle differentiation. Exon 6 is skipped in 7.6% of Fox-2 mRNA in undifferentiated C2C12 cells. This isoform increases to 29% as these cells differentiate into myotubes (Fig. 2B). A large portion of the Fox-2 protein in mouse muscle is expected to be Fox-2ΔE6. Lysates from purified skeletal muscle nuclei were analyzed by immunoblot using a variety of Fox-reactive antibodies (Fig. 2C). An antibody raised to the constant RRM domain detects all Fox proteins containing a full RRM, but binds only weakly to the ΔRRM isoforms (Fig. 2C lane 1; also see Fig. 4, below). Of these bands, the Fox-1 proteins are identified with a Fox-1-specific antibody (lane 2) and Fox-2 with a Fox-2-specific antibody (lane 3). Interestingly, the Fox-2 antibody recognizes two bands not bound by the α-RRM antibody. These are each shifted from the major Fox-2 bands by 3–4 kDa and likely represent the Fox-2ΔE6 isoforms.

FIGURE 4.

Fox-1 and Fox-3, but not their ΔRRM isoforms inhibit the inclusion of Fox-2 exon 6. (A) RT-PCR analysis of the endogenous Fox-2 exon 6 splicing. Human HEK293 and mouse neuroblastoma N2A cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged Fox-1, Fox-1ΔE11, Fox-3, and Fox-3ΔE8 as indicated. (Lanes −) A control transfection with vector not bearing a protein reading frame was carried out in parallel. (Lanes −/−) Samples prepared similarly to the adjacent lanes −, except that reverse transcriptase was omitted. The fraction of Fox-2 mRNA excluding exon 6 is shown below each lane as a percent of the total. (B) The recombinant proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-FLAG and anti-FoxRRM antibodies. Anti-U1 70K Western is carried out in parallel as a loading control.

Exon 6 encodes 31 of the 73 residues within the Fox-2 RRM (Fig. 3A). Skipping of this exon eliminates β-strand 3 and α-helix 2 from the structure. β-Strand 3 includes the critical RNP1 motif for the RRM fold and makes several important contacts with the RNA. Thus, its elimination should drastically alter the protein conformation and RNA binding (Auweter et al. 2006). FLAG-tagged Fox-2 and Fox-2ΔE6 were expressed in HEK293 cells and protein–RNA crosslinks were produced by UV-irradiation in vivo. The recombinant proteins were immunoprecipitated by FLAG antibody and the RNA fragments within the RNA–protein crosslinks were 32P-labeled with polynucleotide kinase. The level of recovered protein was measured by immunoblot with FLAG antibody, and the amount of RNA crosslinked to each protein was determined by autoradiography (Fig. 3B). We find that the Fox-2 ΔRRM protein shows sixfold lower crosslinking to RNA in vivo than Fox-2 containing an intact RRM motif. Thus, the exon 6 deletion greatly reduces RNA binding by the protein. The residual binding could result from RNA contacts remaining in the ΔE6 isoform or from interactions of this isoform with other proteins binding RNA.

FIGURE 3.

The alternative RRM exon encodes the second half of the Fox RRM. (A) The RRM domain of mouse Fox-2 is aligned with the RRM model SMART00360 by a search engine for conserved protein domains (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi). The characteristic RNP1 and RNP2 features are boxed and the secondary structure is drawn to scale below. Skipping of the alternative exon causes deletion of the second half of the RRM, including β-strand 3 and α-helix 2. Fox-2ΔE6 binds RNA weakly in vivo. (B) FLAG-tagged Fox-2 and Fox-2ΔE6, lacking exon 6, were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells and UV-cross-linked in vivo. The FLAG-tagged proteins were affinity purified from cellular lysates pretreated with RNase A. The RNA–protein cross-links were 32P-labeled. After separation by SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane. (Left) The RNA–protein cross-links were detected and quantified by PhosphorImager and the total protein quantified by FLAG Western. (Right) The normalized RNA binding of Fox-2 and RBMΔE6.

The alternative Fox RRM exon is highly conserved across different Fox genes and across species. To look for cis elements potentially regulating these exons, we aligned the exons and their flanking sequences from human, mouse, chick, frog, fish, and fly (Fig. 1B). The Drosophila Fox gene has exactly the same exon as seen in vertebrates. The Fox genes of C. elegans contain exons that begin at the same amino acid as in other species, but extend further downstream and do not align with the other species at the downstream side. Examination of the aligned exons revealed three highly conserved UGCAUG Fox-binding sites flanking the Fox-1 exon as previously noted in Fox-2 (Baraniak et al. 2006). These elements are within the 5′ and 3′ splice sites and immediately downstream of the potential branch point. All vertebrate species have all three elements except for a single U to C change in one element of Xenopus. Remarkably, the branch point and 5′ splice site elements are also found in the Drosophila exon, although flies lack a UGCAUG at the 3′ splice site. The vertebrate Fox-3 exon has none of these Fox binding sites. As shown for mouse Fox-2, the positioning of these UGCAUG elements within the splice sites suggests that the alternative RRM exon is silenced by the Fox proteins themselves as part of a highly conserved autoregulatory loop.

We tested the effect of recombinant Fox and FoxΔRRM protein expression on Fox-2 exon 6 splicing. Human HEK293 and mouse neuroblastoma N2A cells both express Fox-2 mRNA, although immunoblot does not show Fox-2 protein expression in the HEK293 cells (data not shown). In both cell lines, Fox-2 exon 6 is skipped only rarely (1%–2%; Fig. 4A, lanes 2,8). HEK293 and N2A cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged Fox-1, Fox-1ΔE11, Fox-3, and Fox-3ΔE8. The proteins were detected in transfected cell lysates by immunoblot probed with anti-FLAG and anti-FoxRRM antibodies. The anti-FLAG antibody, which binds all of the recombinant proteins, demonstrated that the ΔRRM isoforms were well expressed at levels equivalent to the full-length isoforms. The anti-FoxRRM antibody binds preferentially to the full-length isoforms and only weakly recognizes the ΔRRM isoforms (Fig. 4B). Fox-2 exon 6 splicing was examined by RT-PCR after transient expression of the recombinant Fox proteins (Fig. 4A). Full-length Fox-1 and full-length Fox-3 both caused a five- to 10-fold increase in Fox-2 exon 6 skipping in both HEK293 and N2A cells, as described previously for full-length Fox-2 (Baraniak et al. 2006). The stronger effect seen for Fox-3 is presumably due to its higher expression relative to Fox-1 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, Fox-1ΔE11 and Fox-3ΔE8 did not strongly alter splicing of the Fox-2 RRM exon. These FoxΔRRM isoforms are well expressed in cells, but do not have the same repressor activity, presumably due to their lack of RNA binding.

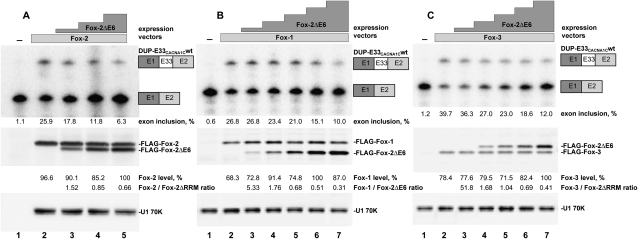

The FoxΔRRM proteins have intact N- and C-terminal domains that can presumably engage in protein–protein interactions, and in normal mouse tissues are coexpressed with the intact RRM isoforms. These proteins could thus affect the splicing of Fox-dependent exons by competing with the full-length Fox isoforms for other interactions. To examine this potentially dominant negative effect, we coexpressed Fox-2ΔE6 with full-length Fox-2, Fox-1, or Fox-3 in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5). Fox-dependent splicing was assayed using the minigene reporter DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt. This contains the highly Fox-dependent exon 33 of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel CaV 1.2 flanked by constitutive β-globin exons (Tang et al. 2009). CaV 1.2 exon 33 expressed from this minigene is skipped in HEK293 cells, which contain very little endogenous Fox protein. Coexpression of recombinant Fox proteins strongly induces exon inclusion to greater than 25% (Fig. 5A–C, lanes 1,2). Increasing amounts of FLAG-Fox-2ΔE6 coexpressed with full-length Fox-2 induce a concentration-dependent decrease of exon 33 splicing (Fig. 5A, lanes 3–5). At the point where expression of the full-length and ΔRRM isoforms is nearly equal, CaV1.2 exon 33 inclusion has been reduced to 11.8% (Fig. 5A, lane 4). Expression of Fox2ΔE6 in the absence of full-length protein had minimal effect on exon 33 (Supplemental Fig. S2, lanes 6–9). Thus, FoxΔRRM can negatively regulate Fox-2 activity. Fox-2ΔE6 also repressed exons activated by either Fox-1 or Fox-3 (Fig. 5B,C). These three paralogs presumably share an interaction needed for splicing enhancement that can be competed with the Fox-2ΔE6 isoform.

FIGURE 5.

Fox-2ΔE6 inhibits Fox-dependent activation of splicing. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with the minigene DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt, containing a Fox-dependent alternative middle exon. A constant amount of FLAG-Fox-2 was cotransfected with increasing amounts of FLAG-Fox-2ΔE6. (Lane −) A control transfection with the minigene only was performed in parallel. (Top) The inclusion of the alternative exon was determined by RT-PCR. The percent exon inclusion is given below. (Middle) The amounts of FLAG-Fox-2 and FLAG-Fox-2ΔE6 were measured by anti-FLAG western. (Bottom) Anti-U1 70K Western served as a loading control. The relative FLAG-Fox-2 levels, shown below each lane are normalized to the U1-70K content. The molar ratios of Fox-2 to Fox-2ΔE6 are indicated. The effect of Fox-2ΔE6 on Fox-1-dependent and Fox-3-dependent splicing of the DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt minigene was studied in a similar way and is shown in B and C, respectively.

We also tested the ΔRRM isoforms of the other Fox genes. These had similar effects as the Fox-2ΔE6 on DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt splicing. Fox-1ΔE11 reduced splicing enhancement by Fox-1 (Fig. 6A), and Fox-3ΔE8 reduced Fox-3 activity (Fig. 6B). Notably, Fox-1ΔE11 had little or no effect on the Fox-1-mediated skipping of endogenously expressed Fox-2 exon 6 (Fig. 6A, bottom). Fox-3ΔE8 had only a moderate effect on the exon skipping in this transcript induced by full-length Fox-3. This indicates that the FoxΔRRM isoforms may compete for interactions necessary for splicing enhancement, but not interactions involved in exon skipping. To examine this possibility, we coexpressed the Fox-2 isoforms with the minigene DUP-E9*CACNA1Cwt. This splicing reporter contains exon 9* of the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel CaV 1.2 that is repressed by Fox (Tang et al. 2009). Coexpressed Fox-2 strongly reduces CaV 1.2 exon 9* splicing from 79.6% to 5.2% in HEK293 cells (Fig. 7, lanes 2,3). Increasing amounts of Fox-2ΔE6 coexpressed with full-length Fox-2 did not restore exon 9* splicing, even at high concentrations (Fig. 7, lanes 3–7). Expression of Fox-2ΔE6 in the absence of full-length Fox-2 protein also did not affect CaV 1.2 exon 9* splicing (Supplemental Fig. S2, lanes 1–5). Thus, Fox2ΔE6 can antagonize splicing activation, but not splicing repression by Fox-2.

FIGURE 6.

Fox-1ΔE11 and Fox-3ΔE8 inhibit Fox-dependent activation of splicing. (A) The minigene DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt, FLAG-Fox-1, and increasing amounts of FLAG Fox-1ΔE11 were cotransfected in HEK293 cells. (B) A similar experiment was carried out with Fox-3 titered with Fox-3ΔE8. (Lanes −) Control transfections with the minigene only were performed at the same time. Lanes −/− were prepared similarly to lanes −, except that reverse transcriptase was omitted. (Top) The splicing of the minigene was analyzed by RT-PCR. The percent of exon inclusion is given below. (Middle) The amounts of Fox and FoxΔRRM were measured by anti-FLAG western. Anti-U1 70K Western served as a loading control. The relative FLAG-Fox levels, shown below each lane are normalized to the U1-70K content. The molar ratios of Fox to Fox-2ΔRRM are also indicated. (Bottom) The effect on splicing of exon 6 of the endogenous of Fox-2 was tested by RT-PCR. The fraction of the Fox-2 mRNA skipping exon 6 is shown below each lane.

FIGURE 7.

Fox-2ΔE6 does not alter Fox-dependent splicing repression. HEK293 cells were transfected with the minigene DUP-E9*CACNA1Cwt, containing a middle exon inhibited by Fox. FLAG-Fox-2 and FLAG-Fox-2ΔE6 were cotransfected into these cells as in Figures 5 and 6. The splicing of the middle exon and the expression of the Fox proteins were determined as above.

DISCUSSION

Many splicing factors are known to control their own expression through alternative splicing. This autoregulation most often occurs by generating an mRNA containing a premature termination codon that is subsequently eliminated by nonsense-mediated decay (NMD). The prototypical examples are the SR and SR-like proteins, where often a stop codon containing “poison exon” is activated by the SR protein through an ESE (Jumaa and Nielsen 1997; Sureau et al. 2001; Kumar and Lopez 2005; Lareau et al. 2007; Ni et al. 2007). Other splicing regulators can repress a critical exon within their pre-mRNA to induce a frameshift and NMD (Stoilov et al. 2004; Wollerton et al. 2004; Dredge et al. 2005; Hase et al. 2006; Saltzman et al. 2008). Indeed, nearly all hnRNP and related proteins show evidence in the EST databases for a NMD targeted isoform (P Stoilov and DL Black, unpubl.). Interestingly, pairs of paralogous splicing factors such as PTB/nPTB and hnRNP L/hnRNP L-like make use of the same mechanism to cross-regulate the expression between paralogs (Boutz et al. 2007b; Spellman et al. 2007; Makeyev and Maniatis 2008; Rossbach et al. 2009).

We find here that the Fox proteins exhibit a similar mechanism of auto and cross-regulation, but with an important difference in the product of this regulation (Fig. 8). Rather than targeting the message for NMD, the Fox-induced splicing creates a Fox isoform that lacks a proper RRM domain. This isoform is missing crucial residues for RNA binding, and, thus, will not mediate splicing enhancement or repression through the UGCAUG element. Instead, the intact N- and C-terminal domains of this isoform can counteract the effect of full-length Fox proteins in enhancing a Fox-dependent exon. Thus, rather than the autoregulated splicing reducing the overall level of the protein, the new isoform directly antagonizes Fox activity.

FIGURE 8.

Diagram of the regulation of Fox expression and activity through splicing of the alternative RRM exon. Fox pre-mRNA, mRNA, and protein isoforms are shown from left to right. The alternative exon, encoding the second half of the RRM motif is shown as a gray box, its flanking constitutive exons as open boxes. The blunt arrows indicate an inhibitory effect.

Autoregulation of the RRM exon is found in both Fox-1 and Fox-2, but perhaps not in Fox-3. Fox-3 shows some skipping of the equivalent exon in EST databases, but we find that this is expressed at very low levels in the brain. The intron sequence flanking this exon in Fox-3 does not contain Fox-binding sites and is not nearly as highly conserved as seen in Fox-1 and Fox-2. It is possible that under some conditions the skipping of this exon is modulated, but it doesn't appear to be autoregulated as seen in Fox-1 and Fox-2. On the other hand, Fox-3 can repress splicing of the alternative RRM exon in Fox-2. Moreover, the Fox-2ΔRRM isoform can antagonize splicing activation by full-length protein from any of the three Fox genes. Although not at the level of NMD, there is clearly a large amount of cross-regulation of activity between the different Fox paralogs.

A significant group of alternative exons shows a high degree of conservation across vertebrate lineages. This conservation is taken as evidence of the functional importance of the change in isoform. These alternative exons are typically flanked by extensive conserved intronic sequence (Sorek and Ast 2003; Yeo et al. 2005; Sugnet et al. 2006). The autoregulated exons of RNA-binding proteins often show particularly high levels of flanking intron conservation. This is seen in the sequence immediately flanking the 93-nt RRM exons of Fox-1 and Fox-2, where large regions are highly conserved across vertebrates (data not shown). This sequence extends far beyond the Fox-binding elements in the splice sites and indicates that other factors beside Fox levels will likely control splicing of these alternative RRM exons. Notably, the 93-nt exons of both Fox-1 and Fox-2 are skipped more frequently in muscle than in brain, again indicating that more than just Fox proteins are affecting their splicing (Fig. 2A). The high level of conservation presumably implies an important role for the alternative splicing of these RRM exons in physiology or development.

Although conservation of splicing regulatory patterns is commonly seen across vertebrates, it is uncommon to find clearly homologous alternative exons in vertebrates and insects. We find that two of the three UGCAUG elements flanking the vertebrate Fox-1 exon 11 and Fox-2 exon 6 are also found flanking an exactly equivalent exon in Drosophila melanogaster. Although this might be an example of convergent evolution, it is very likely that autoregulation of Fox splicing is also occurring in flies and that this will again produce an antagonistic isoform.

The inhibitory effect of FoxΔRRM isoforms on Fox-dependent splicing activation implies that the ΔRRM protein can engage in some of the same interactions as the full-length Fox proteins. It may be that full-length and ΔRRM proteins can form inactive heteromeric complexes. However, we have not been able to observe direct interactions between Fox isoforms in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown). Also, the ΔRRM isoforms do not counteract Fox-dependent silencing, indicating that FoxΔRRM does not simply inactivate the full-length isoforms. Fox-mediated silencing of splicing may require binding to pre-mRNA, but not binding to other proteins needed for enhancement. The protein interactions for which the full-length and FoxΔRRM proteins might compete are not yet clear. Of the described Fox interacting proteins, Ataxin2 is cytosolic and unlikely to be directly involved in splicing (Huynh et al. 1999). The other Fox-binding protein-implicated cerebellar ataxia, Ataxin1, is primarily nuclear (Servadio et al. 1995; Tsai et al. 2004). However, it is unclear whether Ataxin1 is endogenously expressed in HEK293 cells. So far, the only splicing factors known to contact Fox are the hnRNP H/F proteins, which were shown to interact with the C-terminal domain of Fox-2 (Mauger et al. 2008). It is not known whether hnRNP H/F can also bind Fox-1 and Fox-3, but they make interesting candidates for interaction with the FoxΔRRM isoforms.

The interactions required for splicing inhibition by the ΔRRM isoforms likely involve residues that are conserved among the three Fox paralogs. The N- and C-terminal domains of the Fox proteins are 40%–60% identical among the human paralogs and bear many gene-specific features (data not shown). The most conserved features are in the C terminus, where short motifs common to all three paralogs can be identified. Many of these conserved features are subject to alternative splicing, including polypeptides encoded on mutually exclusive brain and muscle-specific exons (B40 and M43). The last 14 amino acids (ending in FAPY) of one of the alternative C termini are also conserved between Fox-1, Fox-2, and Fox-3, and across species. These FAPY ends are required for nuclear localization of the protein (Nakahata and Kawamoto 2005; Lee et al. 2009). Understanding the mechanism by which the ΔRRM isoforms antagonize full-length Fox proteins will require a detailed examination of their interactions. These C-terminal residues might provide a good starting place for this analysis and for understanding the function of the remarkable diversity of isoforms produced from each of the Fox loci.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibody (Pacific Immunology) was raised to a Fox-2 fragment containing amino acid residues 120–205 and affinity purified on antigen. This antibody specifically recognizes the RRM domains of all human and mouse Fox proteins. The Fox-1-specific monoclonal antibody was produced as described (Tang et al. 2009). The Fox-2 antibody was purchased from Bethyl laboratories, Inc. Affinity-purified rabbit antibody to the 15 C-terminal amino acids of U1 70K was provided by Shalini Sharma.

Tissue culture

All cell lines were grown according to ATCC-recommended protocols. Myoblast C2C12 cells were differentiated with DMEM in low-sodium bicarbonate and 2% horse serum for 6 d (Kubo 1991).

Mouse tissue samples

Cerebellum, cortex, striatum, heart, and thigh muscle were dissected from 2-mo-old male and female 129S2 mice. Total RNA was extracted from these tissues using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Mouse skeletal muscle nuclei were prepared by homogenization in high-sucrose buffer, followed by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion (Grabowski 2005).

Western blot analysis

Cells or mouse skeletal muscle nuclei were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA) containing Complete protease inhibitors (Roche) for 20 min on ice. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 20,000g for 15 min and boiled for 5 min in SDS loading buffer. Proteins were resolved on 10% Tris-glycine gels.

For detection of endogenous Fox proteins, gels were transferred to nitrocellulose. Immunoblots were probed with αFoxRRM (1:10,000), αFox-1 (1:10,000), and αFox-2 (1:2,500) antibodies in 1× PBS, 0.25% gelatin, 0.2% Tween-20. Detection used horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia) with SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Pierce).

For detection of transiently expressed Fox isoforms, gels were transferred to PVDF. Immunoblots were probed with αFLAG (Sigma; 1:3,000), αFoxRRM (1:10,000), and αU1-70K (1:5,000), followed by incubation with Cy5 and Cy3-labeled anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies (GE Healthcare, 1:3,000). The membrane fluorescence was imaged by Typhoon PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and quantified using ImageQuant 5.1 software (Molecular Dynamics).

Plasmids

The Fox-1 and Fox-2 cDNA expression plasmids were described previously (Underwood et al. 2005). Fox-3 (protein accession no. NP_001034256) carrying an N-terminal FLAG tag was similarly constructed in pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). Fox-1ΔE11, Fox-2ΔE6, and Fox-3ΔE8 expression plasmids were created by deleting the 93-nt RRM exons. Each of these carried an N-terminal FLAG tag as well.

Transfections

The 40% confluent monolayer cells growing in 6-well plates were transfected with plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. For splicing reporter assays, 100 ng of DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt reporter (ZZ Tang and DL Black, in prep.), 760 ng of plasmid expressing a full-length Fox protein were transfected with varying amounts of a FoxΔRRM plasmid and pcDNA3.1 to total 4.0 μg for all the plasmids. For Fox2 exon 6 splicing assays, 4.0 μg each of Fox-1, Fox-3, Fox-1ΔE11, and Fox-3ΔE8 plasmids were used. The cells were harvested 36 h after transfection. For RNA analysis, total RNA was prepared with TRIzol reagent. For protein analysis, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with Complete protease inhibitors.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was reverse transcribed with (dT)20 primer and Superscript III Reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). For analysis of splicing, splice products were PCR amplified (18 cycles) using a 32P-labeled primer in the 5′ constitutive exon and a cold primer in the 3′ constitutive exon. The primer pairs were as follows (5′ primer and 3′primer): Mouse Fox-1 exon 11, TTTTAATGAGCGAGGCTCCA and CATTGGTGTAGGGGTTGACA; mouse Fox-2 exon 6, GGCAAAATCCTAGATGTGGAA and GCATATGGCGTGACCATCTT; mouse Fox-3 exon 8, CGGGAAAATTTTAGACGTGGA and CATTGGCATATGGGTTCC; human Fox-2 exon 6, CAGTTTGGCAAAATCCTAGATG and GGTGTGACCATCTTCTTATTGG. The primers DUP8 and DUP3 for DUP reporter minigene were as published (Modafferi and Black 1997). Products were separated by 8% polyacrylamide-urea gel electrophoresis, visualized by Typhoon PhosphorImager, and quantified using ImageQuant 5.1 software.

Real-time PCR

The tissue specificity of mouse Fox first exons was determined by real-time PCR performed with SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) 35 cycles, 58.5°C annealing temperature on iCycler IQ5 real-time thermocycler (Bio-Rad). PCR products were amplified using cDNA prepared as described above, a 5′ primer in each alternative first exon and a 3′ primer in a downstream constitutive exon. The primers were as follows: Fox-1 exon 1B, GCTTCCTTGATCAGGCTCAG (this primer is in exon 5 constitutively spliced with exon 1B); Fox-1 exon 1C, TGGCAGCTAATTGCAGTCGT; Fox-1 exon 1C.1, AAATGTGTTTGCAGCGAGTG; Fox-1 exon 1D.1, CAAGCAAGTGAGCGACAGAG; Fox-1 exon 1E, CTACTTCCCGGGACTGATGC; Fox-1 exon 8, GTGGTCAGGGACAGTGGTCT; Fox-2 exon 1A, GGCCACGCACAGAGGAG; Fox-2 exon 1D, ATGGACCAGCCCAGGAAC; Fox-2 exon 1E, TGAAGTGCCTTTTTGTAGTCCA; Fox-2 exon 1F, TGCTTCTTCTGGTTTATGGAGA; Fox-2 exon 1G, AGACTGAAGTCTTTCACCTGAGC; Fox-2 exon 3, TGAGAGATCCATTCTGGTTGC; Fox-3 exon 1A, CTGCAGACCTTTTTGGGAAT; Fox-3 exon 1B, GTGGGGAACGCTGAACC; Fox-3 exon 1C, GGAATCCGGAGACTATTCCTG; Fox-3 exon 3, GACAGGTTCCCGCTAAGGAG. GAPDH product was amplified using primers described (Boutz et al. 2007a). The relative mRNA levels were calculated by comparing threshold cycles for Fox products with GAPDH product using the ΔCT method (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Fox RNA binding in vivo

HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-Fox-2 and FLAG-Fox2ΔE6 as described above. The cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and irradiated with 450 mJ/cm2 in UV Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene) 36 h after transfection and lysed in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.6% NP-40, and Complete protease inhibitors. The RNA was degraded by incubation for 10 min at 30°C with 5 μg/mL RNaseA (Ambion). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 20,000g and incubated overnight with anti-FLAG Sepharose (Sigma). The anti-FLAG Sepharose was washed four times with 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 750 mM NaCl, 0.05% NP-40, once in the same buffer containing 150 mM NaCl (wash buffer), and equilibrated in PNK buffer (New England BioLabs). The bound crosslinked proteins were labeled by incubating the Sepharose with 1.5 μCi/μL [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer) and 0.5 U/μL polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs) for 10 min at 37°C. Following labeling, the Sepharose was washed four times with wash buffer. The bound proteins were eluted from the Sepharose by incubation for 2 h at 4°C in wash buffer containing 150 μg/mL 3× FLAG peptide (Sigma) and Complete protease inhibitors. The eluted proteins were resolved on 10% Bis-Tris Novex gel (Invitrogen) and transferred on PVDF membrane in buffer containing 25 mM Tris-Bicine (pH 7.2), 10% Methanol, and 0.02% SDS. The crosslinked proteins were visualized by Typhoon PhosphorImager and quantified using the ImageQuant 5.1 software. Following this, the membrane-bound Fox proteins were detected by quantitative FLAG Western blot as described above.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pamela Silver and Natalie Farny for providing the Fox-3 clone, Zhenzhi Tang for the DUP-E33CACNA1Cwt and DUP-E9*CACNA1Cwt minigenes, Lauren Gehman and Julia Nikolic for the Fox-1 antibody, and Shalini Sharma for the U1-70K antibody. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 GM49662 to D.L.B. D.L.B. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1838210.

REFERENCES

- Auweter SD, Fasan R, Reymond L, Underwood JG, Black DL, Pitsch S, Allain FH. Molecular basis of RNA recognition by the human alternative splicing factor Fox-1. EMBO J. 2006;25:163–173. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraniak AP, Chen JR, Garcia-Blanco MA. Fox-2 mediates epithelial cell-specific fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 exon choice. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1209–1222. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1209-1222.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla K, Phillips HA, Crawford J, McKenzie OL, Mulley JC, Eyre H, Gardner AE, Kremmidiotis G, Callen DF. The de novo chromosome 16 translocations of two patients with abnormal phenotypes (mental retardation and epilepsy) disrupt the A2BP1 gene. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:308–311. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Activation of c-src neuron-specific splicing by an unusual RNA element in vivo and in vitro. Cell. 1992;69:795–807. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90291-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutz PL, Chawla G, Stoilov P, Black DL. MicroRNAs regulate the expression of the alternative splicing factor nPTB during muscle development. Genes & Dev. 2007a;21:71–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.1500707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutz PL, Stoilov P, Li Q, Lin CH, Chawla G, Ostrow K, Shiue L, Ares M, Jr, Black DL. A post-transcriptional regulatory switch in polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins reprograms alternative splicing in developing neurons. Genes & Dev. 2007b;21:1636–1652. doi: 10.1101/gad.1558107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguillien M, Huang SC, Moriniere M, Dreumont N, Benz EJ, Jr, Baklouti F. Multiple cis elements regulate an alternative splicing event at 4.1R pre-mRNA during erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2001;98:3809–3816. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Gatto F, Plet A, Gesnel MC, Fort C, Breathnach R. Multiple interdependent sequence elements control splicing of a fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 alternative exon. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5106–5116. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dredge BK, Stefani G, Engelhard CC, Darnell RB. Nova autoregulation reveals dual functions in neuronal splicing. EMBO J. 2005;24:1608–1620. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski PJ. Splicing-active nuclear extracts from rat brain. Methods. 2005;37:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase ME, Yalamanchili P, Visa N. The Drosophila heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M protein, HRP59, regulates alternative splicing and controls the production of its own mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39135–39141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedjran F, Yeakley JM, Huh GS, Hynes RO, Rosenfeld MG. Control of alternative pre-mRNA splicing by distributed pentameric repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:12343–12347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J, Zellan JD, Albertson DG. Identification of a candidate primary sex determination locus, fox-1, on the X chromosome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1994;120:3681–3689. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh GS, Hynes RO. Regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing by a novel repeated hexanucleotide element. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1561–1574. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh DP, Del Bigio MR, Ho DH, Pulst SM. Expression of ataxin-2 in brains from normal individuals and patients with Alzheimer's disease and spinocerebellar ataxia 2. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:232–241. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<232::aid-ana14>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Suzuki H, Maegawa S, Endo H, Sugano S, Hashimoto K, Yasuda K, Inoue K. A vertebrate RNA-binding protein Fox-1 regulates tissue-specific splicing via the pentanucleotide GCAUG. EMBO J. 2003;22:905–912. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumaa H, Nielsen PJ. The splicing factor SRp20 modifies splicing of its own mRNA and ASF/SF2 antagonizes this regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:5077–5085. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto S. Neuron-specific alternative splicing of nonmuscle myosin II heavy chain-B pre-mRNA requires a cis-acting intron sequence. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17613–17616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl TR, Shibata H, Vo T, Huynh DP, Pulst SM. Identification and expression of a mouse ortholog of A2BP1. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:595–601. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-2056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KK, Adelstein RS, Kawamoto S. Identification of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) as Fox-3, a new member of the Fox-1 gene family of splicing factors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31052–31061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y. Comparison of initial stages of muscle differentiation in rat and mouse myoblastic and mouse mesodermal stem cell lines. J Physiol. 1991;442:743–759. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Lopez AJ. Negative feedback regulation among SR splicing factors encoded by Rbp1 and Rbp1-like in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2005;24:2646–2655. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau LF, Inada M, Green RE, Wengrod JC, Brenner SE. Unproductive splicing of SR genes associated with highly conserved and ultraconserved DNA elements. Nature. 2007;446:926–929. doi: 10.1038/nature05676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JA, Tang ZZ, Black DL. An inducible change in Fox-1/A2BP1 splicing modulates the alternative splicing of downstream neuronal target exons. Genes & Dev. 2009;23:2284–2293. doi: 10.1101/gad.1837009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AP, Friedlich DL, Harmison G, Howell BW, Jordan CL, Breedlove SM, Fischbeck KH. Androgens regulate the mammalian homologues of invertebrate sex determination genes tra-2 and fox-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:499–506. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Sharp PA. Alternative splicing of the fibronectin EIIIB exon depends on specific TGCATG repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3900–3906. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Hao T, Shaw C, Patel AJ, Szabo G, Rual JF, Fisk CJ, Li N, Smolyar A, Hill DE, et al. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell. 2006;125:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeyev EV, Maniatis T. Multilevel regulation of gene expression by microRNAs. Science. 2008;319:1789–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1152326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Duvall JA, Ilkin Y, Simon JS, Arreaza MG, Wilkes K, Alvarez-Retuerto A, Whichello A, Powell CM, Rao K, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular characterization of A2BP1/FOX1 as a candidate gene for autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:869–876. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauger DM, Lin C, Garcia-Blanco MA. hnRNP H and hnRNP F complex with Fox2 to silence fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 exon IIIc. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5403–5419. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00739-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AE, Minet E, Stern C, Riahi S, Stiles CD, Silver PA. A genome-wide in situ hybridization map of RNA-binding proteins reveals anatomically restricted expression in the developing mouse brain. BMC Dev Biol. 2005;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modafferi EF, Black DL. A complex intronic splicing enhancer from the c-src pre-mRNA activates inclusion of a heterologous exon. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6537–6545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahata S, Kawamoto S. Tissue-dependent isoforms of mammalian Fox-1 homologs are associated with tissue-specific splicing activities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2078–2089. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni JZ, Grate L, Donohue JP, Preston C, Nobida N, O'Brien G, Shiue L, Clark TA, Blume JE, Ares M., Jr Ultraconserved elements are associated with homeostatic control of splicing regulators by alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:708–718. doi: 10.1101/gad.1525507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll M, Akerib CC, Meyer BJ. X-chromosome-counting mechanisms that determine nematode sex. Nature. 1997;388:200–204. doi: 10.1038/40669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponthier JL, Schluepen C, Chen W, Lersch RA, Gee SL, Hou VC, Lo AJ, Short SA, Chasis JA, Winkelmann JC, et al. Fox-2 splicing factor binds to a conserved intron motif to promote inclusion of protein 4.1R alternative exon 16. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12468–12474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossbach O, Hung LH, Schreiner S, Grishina I, Heiner M, Hui J, Bindereif A. Auto- and cross-regulation of the hnRNP L proteins by alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1442–1451. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01689-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman AL, Kim YK, Pan Q, Fagnani MM, Maquat LE, Blencowe BJ. Regulation of multiple core spliceosomal proteins by alternative splicing-coupled nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4320–4330. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00361-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, Yamrom B, Yoon S, Krasnitz A, Kendall J, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servadio A, Koshy B, Armstrong D, Antalffy B, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Expression analysis of the ataxin-1 protein in tissues from normal and spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 individuals. Nat Genet. 1995;10:94–98. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H, Huynh DP, Pulst SM. A novel protein with RNA-binding motifs interacts with ataxin-2. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1303–1313. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R, Ast G. Intronic sequences flanking alternatively spliced exons are conserved between human and mouse. Genome Res. 2003;13:1631–1637. doi: 10.1101/gr.1208803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman R, Llorian M, Smith CW. Crossregulation and functional redundancy between the splicing regulator PTB and its paralogs nPTB and ROD1. Mol Cell. 2007;27:420–434. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoilov P, Daoud R, Nayler O, Stamm S. Human tra2-beta1 autoregulates its protein concentration by influencing alternative splicing of its pre-mRNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:509–524. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugnet CW, Srinivasan K, Clark TA, O'Brien G, Cline MS, Wang H, Williams A, Kulp D, Blume JE, Haussler D, et al. Unusual intron conservation near tissue-regulated exons found by splicing microarrays. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureau A, Gattoni R, Dooghe Y, Stevenin J, Soret J. SC35 autoregulates its expression by promoting splicing events that destabilize its mRNAs. EMBO J. 2001;20:1785–1796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZZ, Zheng S, Nikolic J, Black DL. Developmental control of CaV1.2 L-type calcium channel splicing by Fox proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4757–4765. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00608-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CC, Kao HY, Mitzutani A, Banayo E, Rajan H, McKeown M, Evans RM. Ataxin 1, a SCA1 neurodegenerative disorder protein, is functionally linked to the silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:4047–4052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400615101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood JG, Boutz PL, Dougherty JD, Stoilov P, Black DL. Homologues of the Caenorhabditis elegans Fox-1 protein are neuronal splicing regulators in mammals. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10005–10016. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.10005-10016.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollerton MC, Gooding C, Wagner EJ, Garcia-Blanco MA, Smith CW. Autoregulation of polypyrimidine tract binding protein by alternative splicing leading to nonsense-mediated decay. Mol Cell. 2004;13:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Huang SC, Wu JY, Benz EJ., Jr Regulated Fox-2 isoform expression mediates protein 4.1R splicing during erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2008;111:392–401. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo GW, Van Nostrand E, Holste D, Poggio T, Burge CB. Identification and analysis of alternative splicing events conserved in human and mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:2850–2855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409742102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo GW, Coufal NG, Liang TY, Peng GE, Fu XD, Gage FH. An RNA code for the FOX2 splicing regulator revealed by mapping RNA-protein interactions in stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:130–137. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang Z, Castle J, Sun S, Johnson J, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ. Defining the regulatory network of the tissue-specific splicing factors Fox-1 and Fox-2. Genes & Dev. 2008;22:2550–2563. doi: 10.1101/gad.1703108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]