Abstract

Human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and HHV-6B are lymphotropic viruses which replicate in cultured activated cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) and in T-cell lines. Viral genomes are composed of 143-kb unique (U) sequences flanked by ∼8- to 10-kb left and right direct repeats, DRL and DRR. We have recently cloned HHV-6A (U1102) into bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vectors, employing DNA replicative intermediates. Surprisingly, HHV-6A BACs and their parental DNAs were found to contain short ∼2.7-kb DRs. To test whether DR shortening occurred during passaging in CBMCs or in the SupT1 T-cell line, we compared packaged DNAs from various passages. Restriction enzymes, PCR, and sequencing analyses have shown the following. (i) Early (1992) viral preparations from CBMCs contained ∼8-kb DRs. (ii) Viruses currently propagated in SupT1 cells contained ∼2.7-kb DRs. (iii) The deletion spans positions 60 to 5545 in DRL, including genes encoded by DR1 through the first exon of DR6. The pac-2-pac-1 packaging signals, the DR7 open reading frame (ORF), and the DR6 second exon were not deleted. (iv) The DRR sequence was similarly shortened by 5.4 kb. (v) The DR1 through DR6 first exon sequences were deleted from the entire HHV-6A BACs, revealing that they were not translocated into other genome locations. (vi) When virus initially cultured in CBMCs was passaged in SupT1 cells no DR shortening occurred. (vii) Viral stocks possessing short DRs replicated efficiently, revealing the plasticity of herpesvirus genomes. We conclude that the DR deletion occurred once, producing virus with advantageous growth “conquering” the population. The DR1 gene and the first DR6 exon are not required for propagation in culture.

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is a member of the Betaherpesvirus subfamily, as recently reviewed (46). The virus can enter hematopoietic cells, including T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells (DCs), as well as nonhematopoietic cells, as reviewed in references 8, 17, and 46. In culture, the virus replicates in activated peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs), cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs), and in T-cell lines (1, 17, 46). HHV-6 isolates fall into two distinct classes designated as HHV-6A and HHV-6B variants. The two variants can be distinguished by their restriction enzyme patterns, antigenicity, DNA sequences, and disease association (1, 36, 46). HHV-6B is the causative agent of roseola infantum, a prevalent children's disease characterized by high fever and skin rash (47). In rare cases, the virus exhibits neurotropism and has been found in children experiencing convulsions up to lethal encephalitis (1, 21, 46, 48).

HHV-6B reactivation from latency was found to occur in patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment in bone marrow and other transplantations. This was associated with febrile illness, delayed transplant engraftment, and neurological involvement, up to lethal encephalitis (5, 13, 34, 46). HHV-6A has thus far no clear disease association, although several studies have suggested central nervous system (CNS) tropism, including aggravation of symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) (6, 14, 33, 41).

HHV-6A and HHV-6B share general genomic architecture. The unit-length DNA molecules are approximately 160 kb, composed of a 143-kb unique (U) segment flanked by left and right direct repeats (DRL and DRR, respectively) (19, 24, 27, 46). The DRs are of sizes 8 to 10 kb in different viral isolates (2, 19, 24, 46). In both the HHV-6A and HHV-6B genomes, the herpesvirus conserved cleavage/packaging signals pac-1 and pac-2 (9, 15, 17) are located at the left and the right termini of the DRs (17, 19, 46). The PubMed sequence for the U1102 strain (accession no. NC_001664) starts with the pac-1 signal at positions 1 to 56, followed by multiple copies of perfect and imperfect telomere-like sequences, up to position 418. It was suggested that the telomeric repeats may have originated from host cell chromosomal telomeres (43). Additionally, the DR encodes several open reading frames (ORFs), four of which are dealt with in our paper: (i) the spliced DR1 at positions 501 to 759 and 843 to 2653; (ii) DR5 at positions 3738 to 4164; (iii) the spliced DR6 at positions 4725 to 5028 and 5837 to 6720; and (iv) an ORF of DR7, at positions 5629 to 6720, partially overlapping the DR6 gene (20). Hollsberg and coworkers (37) have recently found that the homologous gene in HHV-6B encodes a nuclear protein that forms a complex with viral DNA processivity factor p41. Gompels and coworkers have also shown that DR1 and DR6 are partly homologous to the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) US22 gene family. Both have a CXC motif: DR1 with homology to the HCMV US26 gene and DR6 with homology to the HCMV US22 gene (20). The map continues with reiterated perfect hexanucleotide telomeric sequences (GGGTAA)n at positions 7655 to 8008 (19, 43). The number of telomeric repeats was found to vary in different viral strains (2, 43). The DR terminates with the pac-2 signal.

We have recently cloned the intact HHV-6A genome into bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs), by direct cloning of unit-length DNA produced from circular or head-to-tail replication intermediates into modified BAC vectors containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) marker and ampicillin-puromycin (Amp-Puro) selection cassette (3). Surprisingly, the HHV-6A BAC clones as well as the parental HHV-6A (U1102) propagated in our laboratory in SupT1 cells were found to contain DRs of ∼2.7 kb instead of the expected ∼8- to 10-kb DRs, as in the early publications (19, 24, 27, 46) and in the PubMed sequence. This has raised the following questions. When did the deleted DRs arise? What was the detailed structure of deleted DRs?

HHV-6 was discovered by Gallo and colleagues in 1986 (35), and viral isolates were obtained in multiple laboratories from AIDS patients, patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, and patients with roseola infantum (12, 26, 42, 45, 47). The isolates were propagated initially in activated PBLs and CBMCs and then in continuous T-cell lines, including HSB-2, J-JHAN, SupT1, Molt-3, and MT-4 (11, 45). The U1102 strain isolated by Downing and colleagues (12) was contributed to our laboratory by Robert Honess and was propagated first in activated PBLs and CBMCs (11, 18, 36, 45) and then in J-JHAN and SupT1 T cells (4, 30). To answer the question with regard to the origin of the short DRs and their structure, we have compared earlier viral HHV-6A passages with the currently propagated virus and the HHV-6A BAC clones. We describe here the detailed structure of the DRL and DRR of the “new” virus, containing the short ∼2.7-kb DR. We show that the deletion contained the left multiple repeats of telomere-like sequences and the ORFs from DR1 up to the DR6 first exon. Review of viral passaging since 1992 indicated that the deletion occurred spontaneously. The deleted viruses were stably and efficiently propagated in SupT1 T cells, indicating that the DR1 and DR6 first exons are not essential for virus in vitro replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The SupT1 CD4+ human T-cell line (39) was obtained from James Hoxie, NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. The cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 medium, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. We received the HHV-6A (U1102) from Robert Honess (Leeds University, England) (12). CBMCs were obtained from Tel-Hashomer-Sheba Hospital and were prepared by Ficoll blood separation (32). The cells were activated and maintained in a mixture of RPMI 1640, 10% FCS, and 10 μg/ml phytohemagglutinin (PHA). Virus maintenance propagation was routinely by “cell-to-cell” infections involving cocultivation of the infected cells with fresh uninfected cells. For some experiments, the virus obtained from the medium was concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 h 15 min at 4°C at 21,000 rpm in a Beckman SW28 rotor. The infected cells showed typical cytopathic effects (CPE) of cell enlargement, ballooning, and syncytia. The following viruses were analyzed in this paper. (i) The virus designated “U1102-new-CBMC→SupT1” has been abbreviated here as “U1102-N-CB→S.” This stock corresponds to our current laboratory stock. The virus has been propagated since 1992 in activated PBLs and CBMCs. Since 1996, the virus has been propagated also in J-JHAN and SupT1 cell lines, each time for a limited period going back to large frozen “mother pools” to avoid the accumulation of mutations. (ii) The virus designated as “U1102-CB→CB” was propagated initially by cell-to-cell infections in activated CBMCs. A frozen sample from 1992 was thawed and propagated during 2009 in CBMCs, for 8 passages prior to DNA analyses. (iii) The virus designated “U1102-CB→S” was propagated in CBMCs and frozen in 1992. A frozen sample was thawed and propagated during 2009 for 8 passages in CBMCs followed by propagation in SupT1 cells for 24 passages prior to the DNA analyses. (iv) The virus designated “GS-CB→CB” corresponds to the HHV-6A (GS) strain that was propagated in CBMCs. An early viral stock was thawed and propagated during 2009 in CBMCs for 8 passages prior to analyses. (v) The virus designated “U1102-Japan-CBMC→CBMC,” abbreviated here as “U1102-J-CB→CB,” was a kind gift from Koichi Yamanishi and Yasuko Mori, Osaka University, Japan. It was propagated in Japan and recently in our laboratory during 2009 in CBMCs for 8 passages prior to analyses of viral DNA.

BAC clones.

The HHV-6A BACs were derived (3) by direct cloning of a unit-length viral genome prepared from circular or head-to-tail concatemeric genomes into a modified pIndigoBAC-5 plasmid. The viral BAC clones contain a GFP marker, an Amp-Puro cassette, and loxP sequences flanking the BAC region. Several HHV-6A BACs were prepared in three independent cloning experiments using different viral DNA preparations.

Preparation of packaged HHV-6A DNA.

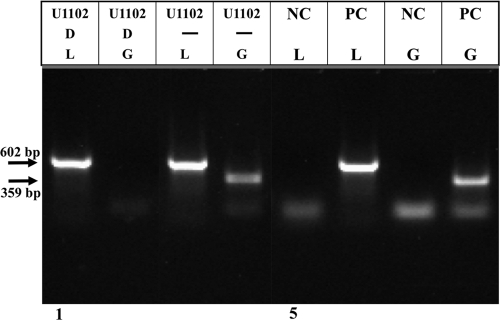

Infected cell cultures with pronounced CPE were fractionated by low-speed centrifugation, and the virus in the medium was concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 21,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 h 15 min in a Beckman SW28 rotor. Resultant pellets were treated with 30 μg DNase I in a final volume between 100 to 200 μl to eliminate unpackaged viral DNA and cellular DNA. DNA samples before and after the DNase I treatment were analyzed by PCR, employing primers for hGAPDH (human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), to detect remaining host DNA. HHV-6A primers from the left part of the genome (L), positions 15000 to 15602, were used to test recovery of viral DNA. The results of the PCR tests can be summarized as follows. (i) The DNase I digestion removed the hGAPDH sequences (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 4). (ii) The L primers yielded a PCR band of the appropriate size, 602 bp, with both DNase I-treated and untreated samples (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 3). The DNA preparations devoid of the cellular DNA were considered as packaged viral DNAs throughout the study.

FIG. 1.

Preparation of packaged DNase I-resistant viral DNA. Concentrated samples from infected cell medium without (−) and with DNase I (D) treatment were tested for the presence of cell DNA by PCR employing the hGAPDH (G) primers and for the presence of viral DNA by PCR with the L primers from positions 15000 to 15602 of HHV-6A (U1102) DNA. NC is a negative control without DNA template. PC is a positive control, including primers and total infected cell DNA.

Analyses of DNA from virus preparations embedded in agar plugs.

Medium of infected cells was concentrated by ultracentrifugation. The pellet was treated with 30 μg DNase I in a final volume between 100 to 200 μl and then mixed with an equal volume of 2% low-melting-point melted agar. The virion-embedded 1% agar preparations were poured into Bio-Rad agar plug molds and were incubated at 4°C for 15 min to allow solidification. The plugs containing virions were incubated in 2 ml lysis buffer containing 0.5 M EDTA, 500 μg proteinase K, and 1% N-lauroylsarcosine (Fluka). Plugs containing the DNA were then rinsed 4 times in 5 ml Tris-EDTA (TE) at room temperature with gentle agitation, each time for 45 to 60 min. The agar plugs that contained the viral DNA were treated with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) to inactivate residual proteinase K activity and were then incubated in 200 μl of restriction enzyme buffer. Following addition of 50 units of restriction enzyme, the plugs were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Segments of the plugs were loaded into gel wells along with DNA size markers: a 15- to -300-kb DNA ladder (Midrange I; New England BioLabs) and a 0.25- to 10-kb ladder (Perfect Plus; 1 kb of EURx). PFGE was conducted using the clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) apparatus (Bio-Rad) at 14°C. The electrophoresis parameters were 18 h at 6 V/cm at 120°C with switch times of 1 to 25 s. The gels were stained with 1 μg/ml ethidium-bromide (EtBr). They were transferred to Southern blots and hybridized with the probes specified.

Probes for Southern blot hybridizations.

The template for the hybridization was prepared first by PCR of total HHV-6A (U1102)-infected cells employing the following primers: pac-2 starting at sense position 159244 (5′CCCCCAACGCGCGCGCGCAC3′) and pac-1 starting at antisense position 52 (5′CCCCCCCTTTTTTTAGCCCCCCCGGG3′). The resultant 130-bp fragment included the pac-2-pac-1 junction sequences between putative two adjacent DRs. The hybridization probe was generated from the 130-bp fragment by digoxigenin (DIG) PCR (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), employing 2-fold excess of TTP to UTPDIG. Hybridization was carried out at 63°C for 16 to 24 h.

PCR analyses of the HHV-6A DNA in cell-free virions.

Infected cell medium was ultracentrifuged, and the pellets were tested by PCR before and after DNase I treatment employing the following primers. (i) The L primers, from positions 15000 to 15602, yield a 602-bp PCR product. The primer sequences were as follows: sense, 5′CCCCATTCAACATCCTATTGA3′; and antisense, 5′CCGGAAAGACCATTGCCG3′. (ii) The R primers, from the right part of the genome, positions 134263 to 134591, yield a 328-bp PCR product. The primer sequences were as follows: sense, 5′TTCTCCAGATGTGCCAGGGAAATCC3′; and antisense, 5′CATCATTGTTATCGCTTTCACTCTC3′. (iii) Primers from the cellular gene coding for hGAPDH yield a 359-bp PCR product. The primer sequences were as follows: sense, 5′CAGAAGACTGTGGATGGCCC3′; and antisense, 5′GTTGAGGGCAATGCCAGCC3′.

pGEM cloning and sequencing of PCR products.

The ∼2.7-kb DR sequences were amplified by PCR employing the EXL DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The primers used were from pac-1 positions 1 to 32 (5′CGCGTTTTAAAAATTACGTCAAATCCCCCGGG3′) to pac-2 positions 8087 to 8068 (5′CACGCGTCTCGCAGCGGCGC3′). The resultant PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega). The pGEM clones containing the cloned ∼2.7-kb PCR-amplified DR were sequenced, employing primers within the pGEM vector sense positions 2929 to 2959 (5′GGGTAACGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACG3′) and pGEM antisense positions 112 to 81 (5′GCATCCAACGCGTTGGGAGCTCTCCCATATGG3′).

Tests for the presence of DR1, DR5, and DR6 sequences.

The primers used to detect the first exon of DR1 were positions 504 to 527 (5′CCGCTAACGGTGCGTGCCGGGCAC3′) and positions 749 to 717 (5′CTTCGTAGGCCAGCCCTGAAGAAGATGCGGTTG3′). The expected fragment size was 245 bp. The primers used to detect the second exon of DR1 were positions 843 to 874 (5′GGTTCGACCCTAAACCCTACCATCCTTCGGCC3′) and positions 2648 to 2629 (5′CCGTGTGTGCGGCGGGCGGC3′). The expected fragment size was 1,805 bp. The primers used to detect the DR5 ORF (NC_001664.1) were sense positions 3738 to 3769 (5′CCTTCTCCGTACGTCCCCTTTCCGTAAGTGCC3′) and antisense positions 4164 to 4137 (5′CGAGGGCGGGCCCGAGCAAACAGTCTCG3′). The expected fragment size was 426 bp. The primers used to detect the first exon of DR6 were positions 4732 to 4756 (5′CGCGACACACACAGAGGACGGGCGG′3) and positions 5022 to 4992 (5′CTTGAACGCATCTGGGTCTCACGTGCGTCGC3′). The expected fragment size was 290 bp. The primers used to detect the second exon of DR6 were from positions 5837 to 5867 (5′CCCTAGACTCCTGTCTGTACGTATGTTGCGG3′) and positions 6717 to 6691 (5′CTTCACCTCCGTGGCGTCTAATCCAGG3′). The expected fragment size was 880 bp.

RESULTS

Overall design of the study and the assembly of the HHV-6A strains tested.

We have recently cloned unit-length HHV-6A DNA derived from circular or head-to-tail concatemeric replicating intermediates into BAC vectors (3). Several HHV-6A BAC clones, produced in three independent experiments possessed similar restriction enzyme patterns. Surprisingly, analyses of all the clones revealed that the BACs, as well as the parental virus from SupT1-infected cells contained a short DR with a size of ∼2.7 kb. Earlier reports concerning different viral strains have shown that DR sizes were from 8 to 10 kb in different viral isolates (2, 19, 24, 46). Our finding of the ∼2.7-kb DRs in the BAC clones and in viral replicating DNA raised the question whether the short DRs were an inherent property of the virus or resulted from DR shrinkage during laboratory passaging.

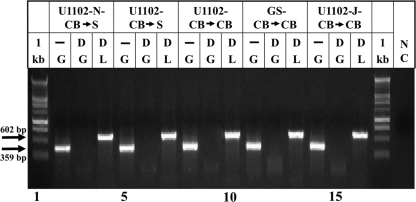

In attempt to compare the sizes of the DRs along laboratory passaging, several HHV-6A preparations were assembled from frozen early HHV-6A stocks, as described in Materials and Methods and compared to the “new” U1102-N-CB→S virus stocks with the short DRs (the current laboratory stock). The frozen early viral stocks were thawed and were further expanded either in CBMCs or in SupT1 cultures, to test if merely passaging of the viruses in SupT1 cells promoted DR shortening. Two additional HHV-6A stocks were included in the analyses. (i) The HHV-6A (42) strain, a kind gift from D. Ablashi, Z. Salahuddin, and R. Gallo, was passaged in our laboratory in CBMCs. A frozen early stock was now further propagated in CBMCs prior to the DNA analyses. (ii) An HHV-6A (U1102) stock passaged in CBMCs in Japan was a kind gift from K. Yamanishi and Y. Mori. The frozen sample received from them was further propagated in CBMCs prior to DNA analyses. In all cases, viruses secreted into the medium were concentrated, pelleted, and treated with DNase I to remove cellular and nonpackaged viral DNA, as described in Materials and Methods. PCR analyses employing the hGAPDH and the HHV-6A L primers verified the removal of cellular DNA from the viral DNA preparation (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Preparations of packaged DNase I-resistant DNA from different HHV-6 preparations. Concentrated samples from infected cell medium without (−) and with DNase I (D) treatment were tested for the presence of cell DNA by PCR employing the hGAPDH (G) primers and for the presence of viral DNA by PCR with the L primers from positions 15000 to 15602 of HHV-6A (U1102) DNA. The sizes of PCR products are marked, based on the known DNA sequences. Lanes 1 and 17 include the 1-kb DNA marker (1 kb). NC, negative control (without template).

The structure of the DRs in various HHV-6A preparations.

HHV-6A infections are relatively inefficient, and infectious virus yields per cell are several orders of magnitude lower than the yields of infectious alphaherpesviruses, including herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2. Analysis of HHV-6 DNA structure required virion concentration and careful handling of the large extracted DNA. After ultracentrifugation of infected cell medium, the DNase I-treated pellets containing packaged virions were embedded in agar plugs and all remaining handling was within the plugs to avoid DNA breakage. This included deproteinization to extract viral DNA and restriction enzyme cleavages. Segments of the plugs containing the cleaved DNAs were loaded into the gel wells for PFGE, along with the size markers.

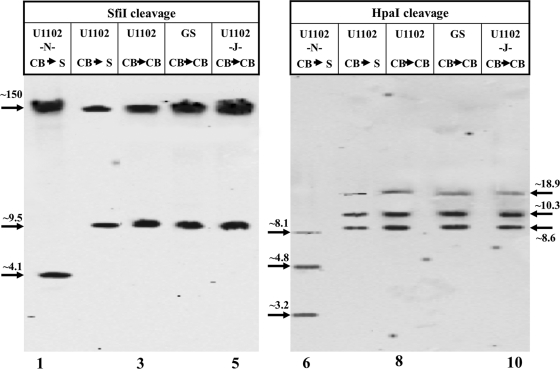

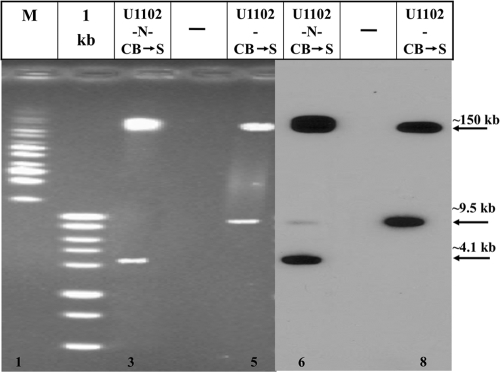

It was previously reported that HHV-6A DRL and DRR were similar in their sizes and sequences (20, 24, 27). In the present study, we have employed the SfiI and HpaI enzymes to determine the structure of the left and right DRs in the U1102 virus with the shorter DR. SfiI cleaves the HHV-6A genome once at position 9520 within the unique sequence, at the U2 gene. Based on the PubMed sequence, the cleavage of the linear packaged DNA with SfiI was expected to yield a left terminal fragment of size ∼9.5 kb. This fragment contains the ∼8-kb DRL and an additional 1,432 bp, from the end of the DR up to the SfiI site in the unique region. Gel blocks containing the DNase I-treated packaged virions were deproteinized in the plugs, and the resultant DNAs were cleaved with SfiI. Segments of the plugs were loaded onto the gel wells, along with size markers. The pulsed-field gels were blotted and hybridized with the 130-bp pac-2-pac-1 probe to detect the terminal sequences. As seen in Fig. 3 (lanes 1 to 5), digestion of all samples with the exception of the “new” lab strain (U1102-N-CB→S) yielded an ∼9.5-kb band in addition to the ∼150-kb large fragment, as expected from the PubMed sequence. It is noteworthy that all the stocks frozen in 1992 and passaged in 2009 8 times in CBMCs contained the ∼9.5-kb terminal SfiI fragment, with an ∼8-kb DRL. Moreover, the U1102-CB→S 1992 stock, which was passaged recently 8 times in CBMCs followed by 24 passages in SupT1 cells, also showed the ∼9.5-kb band. In contrast, the digestion of the laboratory strain U1102-N-CB→S with SfiI gave an ∼4.1-kb fragment, indicating shortening of the DRL by ∼5.4 kb, as was found in the HHV-6A BAC clones (3).

FIG. 3.

The DRs of the U1102-N-CB→S laboratory stock are shorter than the DRs from the various packaged viral stocks. DNAs extracted from the virus preparations embedded in agar plugs were digested with the SfiI (lanes 1 to 5) and the HpaI (lanes 6 to 10) enzymes. The PFGE gels were blotted and hybridized with the pac-2-pac-1 probe. Fragment sizes are denoted in kb.

The size of the DRR of the various test viruses was determined by HpaI digestion, and as seen in Fig. 3, the hybridization of the pac-2-pac-1 probe to the cleaved DNA again revealed differences between the “new” lab strain (U1102) and the other samples. The early HHV-6A virus stocks yielded 2 major bands of 8.6 kb and 10.3 kb and a minor band of 18.9 kb (Fig. 3, lanes 7 to 10). The major bands corresponded to the left and right genome sequences matching the linear genomes depicted in PubMed. A minority of the population formed circles with linked DRL and DRR (24, 38), yielding the larger 18.9-kb cleaved band. In contrast to the early viruses, cleavage of the “new” U1102-N-CB→S DNA with HpaI yielded two major bands of 3.2 kb and 4.9 kb and a minor band of 8.1 kb (Fig. 3, lanes 6). The DRL and the DRR of the U1102-N-CB→S preparation are each shorter by 5.4 kb than the DRs of the standard HHV-6A (U1102) genome (42).

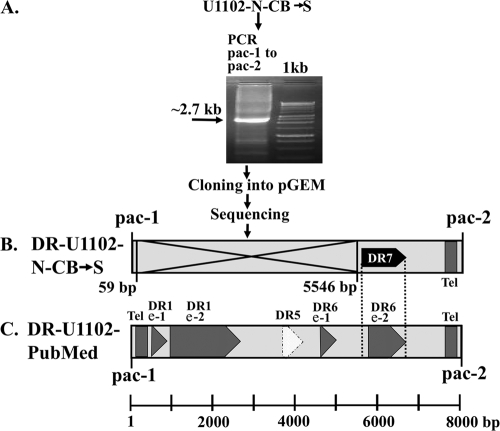

Cloning and sequencing of the HHV-6A (U1102) short DR.

Since the pac-1 and pac-2 are located at the borders of the DRs, they were chosen as primers for cloning the short DR and sequence analyses. The results confirmed the existence of a deletion in the U1102-N-CB→S preparation. The PCR of the laboratory strain yielded an ∼2.7-kb fragment (Fig. 4A), which was cloned into the pGEM vector. The sequencing of the ∼2.7-kb cloned DR revealed the presence of a large deletion. Specifically, following the first 59 bp containing the pac-1 signal, there was a deletion spanning positions 60 to 5545, including the two DR1 exons, the DR5 ORF and the first DR6 exon (Fig. 4B). The sequences which were retained in the U1102-N-CB→S mutant start from position 5546 and include the DR7 ORF at positions 5629 to 6720. Examination of this ORF reveals that it is preceded by a TATA signal and noncanonical promoter elements and it contains the second exon of DR6. Following conserved telomeric GGGTTA repeats, the DR terminates with the pac-2 signal. The deletion boundaries of the U1102-N-CB→S mutant (Fig. 4B) are apparent by comparison with the undeleted DR depicted schematically in Fig. 4C. The sequencing data of the pGEM clone fully corroborated the estimated ∼5.4-kb deletion, as apparent from the Southern blot of Fig. 3. The deletion was contiguous as predicted for a single-step event, rather than sequential deletions of noncontiguous sequences. Importantly, the deletion did not affect the propagation and infectivity of the U1102-N-CB→S stock.

FIG. 4.

Scheme of the pGEM cloning and sequencing of the DR of U1102-N-CB→S. (A) DNA from packaged virus was amplified by PCR, employing the pac-1-pac-2 primers. The ∼2.7-kb product was cloned into pGEM, and the resultant clones were sequenced. (B) Schematic diagram of the deleted DR in U1102-N-CB→S, based on the sequenced pGEM clones, showing an ∼5.4-kb deletion between bp 60 and 5545. The deletion is marked with a large X. The DR7 sequence (positions 5629 to 6720) overlaps the second exon of DR6, as denoted in PubMed. Relative positions of the DR7 start and stop codons are marked by dotted lines. (C) Schematic diagram of the arrangement of sequences within the HHV-6A (U1102) DR based on the PubMed sequence denoting the pac-1 and pac-2 signals, the telomeric repeats (tel), the DR1 and DR6 exons (denoted as e-1 and e-2), and the DR5 ORF.

A minority of the U1102-N-CB→S stock has nondeleted DRs.

We compared the U1102-N-CB→S with the early virus designated as U1102-CB→S. This virus stock was frozen in 1992, thawed in 2009, and propagated initially for 8 passages in CBMCs and then for 24 passages in SupT1 cells. As seen in Fig. 5 (lanes 5 and 8), the early virus kept the ∼9.5-kb SfiI fragment, throughout propagation for 24 passages in the SupT1 cells. To test whether the deletion was apparent in all the U1102-N-CB→S DNA molecules, viral stocks digested with SfiI (as in Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2) were exposed to Southern blot hybridization with the pac-2-pac-1 probe. The blot was overexposed to reveal minor bands. As seen in Fig. 5 (lanes 3 and 6), the SfiI cleavage of U1102-N-CB→S yielded the major ∼4.1- and ∼150-kb bands. However, after a very long exposure, a weak band of ∼9.5 kb was also visible, indicating that a minority of the population contained DNA molecules with undeleted DR. The ∼4.1-kb band was very intense compared to the ∼9.5-kb band, and the ratio between these bands could not be quantified by densitometry analyses. We conclude that the majority of the virions in the U1102-N-CB→S stock contained the short, ∼2.7-kb deleted DRs. Only a minority of the DNA population yielded the ∼9.5-kb SfiI band, corresponding to an ∼8-kb DR. Additionally, the DR of the U1102 CB→S early viral stocks did not shrink upon 24 passages in the SupT1 cells and viral DNAs contained solely the ∼9.5-kb SfiI terminal fragment.

FIG. 5.

The U1102-N-CB→S virus contains a majority of molecules with deleted DR and a minority of genomes with nondeleted DR. Lanes 3 and 6, EtBr and blot hybridizations of SfiI-digested packaged DNA preparations from the U1102-N-CB→S; lanes 5 and 8, EtBr and blot hybridizations of SfiI-digested packaged DNA preparations from the early stock U1102-CB→S which was propagated 24 passages in SupT1 cells. “1 kb” represents the 1-kb DNA marker, and M represents the midrange DNA marker.

Analyses of the U1102-N-CB→S for the presence of DR1-to-DR6 sequences.

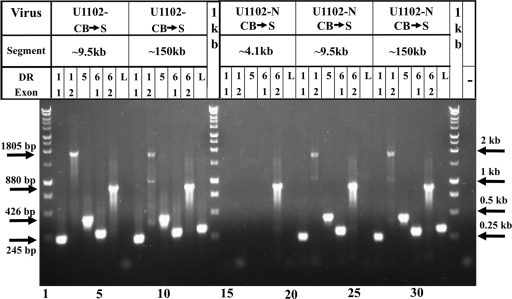

The sequence of the pGEM-cloned ∼2.7-kb DR (Fig. 4) revealed that the deletion included the sequences from DR1 up to the first exon of DR6. At the same time, when we tested the U1102-N-CB→S DNA preparation with primers from the two exons of DR1, the DR5 ORF, and the two DR6 exons, a positive PCR was obtained (data not shown). This could have reflected a translocation event from the DRL and DRR termini to other locations in the viral genome and/or the presence of a minority of DNA molecules with nondeleted DRs, as was shown in Fig. 5. In this last case, we expect that the DR1-through-DR6 primer would yield a positive PCR upon testing the minor leftmost ∼9.5-kb SfiI fragment as well as when testing the ∼150-kb fragment, extending from position 9.5 through the entire genome, including DRR. To test this prediction, the ∼4.1-kb, ∼9.5-kb, and ∼150-kb SfiI bands of the U1102-N-CB→S DNA were extracted from a gel similar to gel shown in Fig. 5. They were tested by PCR, employing primers of the DR1 exons 1 and 2, DR5, and the DR6 exons 1 and 2. The results (Fig. 6) can be summarized as follows: (i) the ∼4.1-kb band did not yield positive PCR fragments with primers of the DR1 exons, the DR5 ORF, and the first exon of DR6. Only the second exon of DR6 (primer DR6-2) was positive, as expected from the pGEM ∼2.7-kb sequence. (ii) The ∼9.5-kb minor band gave positive PCR fragments with all of the DR primers. It is thus shown that the ∼4.1- and 9.5-kb bands were adequately separated: the ∼4.1-kb band was negative, whereas the ∼9.5-kb terminal SfiI fragment with undeleted DR was PCR positive. (iii) The L primer located at positions 15000 to 15602 (PubMed accession no. NC_001664) did not yield a positive PCR product when tested employing the ∼4.1- and the ∼9.5-kb bands, as expected. (iv) The ∼150-kb band was PCR positive for the DR1, DR5, and DR6 primers, as well as the L primer, suggesting that the band contained also the minor species with undeleted DRs present in the U1102-N-CB→S viruses. Further confirmation of this suggestion was obtained by studying the HHV-6A BAC clones below.

FIG. 6.

PCR analyses of SfiI fragments with the DR1, DR5, and DR6 primers. Analyses of the U1102-N-CB→S and the early U1102-CB→S stock propagated 24 times in SupT1 cells. Viral DNAs from virions in the gel plugs were digested with SfiI and fractionated in the gel to ∼4.1-, ∼9.5-, and 150-kb bands, which were tested for the presence of the DR sequences by PCR. The following primers were employed: DR1 exon 1 (1-1); DR1 exon 2 (1-2); DR5 (5); DR6 exon 1 (6-1); DR6 exon 2 (6-2); and the L primers from positions 15000 to 15602. “1 kb” represents the 1-kb DNA ladder. The sizes of the PCR-amplified fragments are depicted at the left side of the gel. The sizes of some of the 1-kb ladder bands are depicted on the right.

The utilizing of the HHV-6A BAC clones for DR characterization.

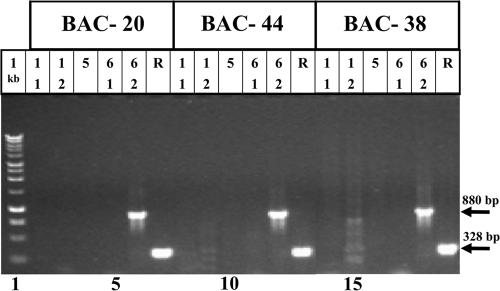

To verify that DR1-to-DR6 region was altogether deleted in the major types of U1102-N-CB→S DNA molecules and not just translocated to other sites within the genome, we employed the recent HHV-6A BAC clones, containing the complete HHV-6A genome, with a size of ∼160 kb (3). Three independently generated HHV-6A BAC clones were tested by PCR to determine whether the DR deletion was complete or the DR1, DR5 ORF, and DR6 exon 1 sequences were translocated elsewhere in the viral genome. The BAC clones 20, 44, and 38 were tested by PCR. As shown in Fig. 7, the DR1 exons 1 and 2, DR5, and the first exon of DR6 were altogether absent in the three HHV-6A BACs. The second exon of DR6 was present, producing a PCR fragment of 880 bp, as predicted from the sequencing data of the deleted DR. Thus, in the three BAC clones the deleted DR sequences were completely eliminated and there were no translocations.

FIG. 7.

PCR analyses of HHV-6A BAC clones for DR1, DR5, and DR6 DNA sequences. The three independently derived HHV-6A BAC clones (BAC-20, BAC-44, and BAC-38) were tested for the presence of the DR sequences by PCR. The following primers were employed: DR1 exon 1 (1-1); DR1 exon 2 (1-2); DR5 (5); DR6 exon 1 (6-1); and DR6 exon 2, 6-2. The R primers were from positions 134263 to 134591 of HHV-6A (U1102). “1 kb” represents the 1-kb DNA size ladder.

DISCUSSION

The study described in this paper was initiated after we noted that HHV-6A BAC clones and the parental replicative intermediates contained a short DR with a size of ∼2.7 kb (3). The sequencing of the pGEM-cloned DRL revealed the presence of a deletion, spanning positions 60 to 5545 of the viral genome, including the leftmost imperfect telomeric repeats, the spliced DR1 gene, and the first exon of the DR6 gene. The availability of viral stocks frozen in 1992 and the chronology of their passaging up to the present time have allowed us to follow the development of DR shrinkage. The early viral stocks of 1992 did not possess the ∼5.4-kb deletion and contained DRs of ∼8 kb, in accordance with the PubMed sequence. The nondeleted DRs were found also in the HHV-6A (U1102) stock from Japan and in the HHV-6A (GS) strain. Furthermore, our study involving the propagation of the virus in CBMCs followed by propagation in SupT1 cells for 24 passages has shown that the ∼8-kb DRs containing viruses were stable. The initial observation of short DR in the current U1102-N-CB→S virus stock propagated in SupT1 cells was confirmed by the sequencing data. These results suggest that the deletion occurred spontaneously at a single time point during the passaging. The finding that the deletion contained a contiguous stretch of DNA indicates there was a single deletion event, rather than gradual accumulation of deletions during the passaging affecting different portions of the DR sequences. Once produced, the deletion mutant appeared to have advantageous growth capability and it became the most abundant species in the passaged stocks.

To examine whether the deleted genes were translocated into other regions of the viral genome, we tested by PCR the BAC clones, containing the entire ∼160-kb genome (3). The results revealed that all the HHV-6A BAC clones contained the short DRs and were altogether lacking the DR1-to-DR6 first exon sequences: i.e., the deleted sequences were not translocated to other locations in the genome. Because the majority of viral DNA sequences in packaged U1102-N-CB→S virus contained the deleted DRs, we suggest that viral replication in vitro did not require DR1 and DR6 first exon gene expression.

The finding that both DRL and DRR contained the deletion indicated the existence of a mechanism for the duplication of the termini, most likely related to the presence of the pac-1 and pac-2 signals. Such a mechanism was first proposed in conjunction with the findings that the majority of replicating HSV-1 DNA molecules contained in their S-L junctions “bac” sequences with a single “a.” A lower proportion of genomes contained “baac” and higher numbers of “a” repeats (25). Because the signal for cleavage was in the HSV Uc-DR1-Ub sequence located in the “a-a” junction, we proposed and showed an “a” duplication occurred during packaging (9, 16, 44). We suggested that the duplication occurred by the double-stranded break gap repair mechanism (9, 16, 40). Duplication of the “a” sequence also was found in experiments with amplicon vectors in which “bac” junctions gave rise to cleavable “baac” junctions (9, 10, 16).

Duplication of single terminal sequence was shown in additional viruses. Thus, Mockarski and coworkers (28) have shown that the guinea pig CMV genomes contain almost exclusively single copies of the terminal repeat and they suggested that terminal repeat duplication occurred in conjunction with cleavage. We have recently documented that significant proportions of HHV-6A DNA replication intermediates as well as the HHV-6A BACs contained a single DR (3). We have proposed that the single DR evolved by intermolecular homologous reductive recombination of unstable DR-DR junctions most likely produced after viral DNA circularization. Later in the infection, the DR sequences must be duplicated so as to have the pac-1 and pac-2 signals properly juxtaposed to form the target for cleavage of concatemeric replication intermediates generated by the rolling circle mechanism. In the paper, we have shown that both DRL and DRR were shortened, fortifying the copying mechanism during packaging.

The sequencing data have shown the absence of DR1 and DR6 exon 1 sequences in the DRs. The sequences retained in the mutant virus included bp 1 to 59 of the genome, containing the pac-1 signal, skipping the deleted DR region to incorporate the DNA sequences from position 5546. Of interest is the fact that the DR7 sequences are situated 83 bp away from the deleted sequences and that upstream of the DR7 ORF there are noncanonical promoter sequences. Although The DR7 ORF was retained in the U1102-N-CB→S mutant, additional studies are required to determine whether the gene functions in viral DNA replication, as suggested for the homologous HHV-6B counterpart (37). Furthermore, it is of interest to test why the DR1 gene is nonessential for the propagation of the deleted HHV-6A stocks and what role the first exon of DR6 plays in the putative protein encoded by DR7 and the second DR6 exon.

Analyses of the packaged viral DNA by blot hybridizations with the pac-2-pac-1 probe, as well as the results of PCR tests, revealed the presence of virions containing nondeleted, ∼8-kb DRs. The levels of the nondeleted virus were too low to compare the relative abundance of the deleted and nondeleted genomes by densitometric analyses of the ∼4.1- and ∼9.5-kb SfiI bands (Fig. 5). The blot had to be overexposed for the visualization of the minor ∼9.5-kb band. In light of the low abundance of viruses with an ∼8-kb DR within the mixed population, it is unlikely that the infectivity of deleted viruses will depend on complementation with undeleted viruses. Rather, it is likely that the deleted DR1 to DR6 first exons are not required for viral replication. It is possible that the minute amount of ∼8-kb virus that secrete soluble product and/or small interfering RNA (siRNA) or microRNA (miRNA) product(s) might affect the replication of the DR-deleted virus. Experiments to test this possibility are ongoing.

Our current study has revealed spontaneous plasticity of the viral genome, during which segments not essential for in vitro viral propagation were deleted. The accumulation of genome variations including deletions as a consequence of serial passages have been observed in various herpesviruses, exemplified below by HCMV genome alterations. Spaete and coworkers (7) have reported strain variations that involved the loss of large DNA segments in the highly heterogenous region of the Toledo, Towne, and AD169 laboratory strains. They suggested that the loss occurred during laboratory passage. Shenk and coworkers (31) have analyzed 6 strains of HCMV. This included the laboratory strains AD169 and Towne that have been extensively passaged in fibroblasts and 4 clinical isolates that have been passaged to a limited extent (Toledo, FIX, PH, and TR). They have found substantial variation in the sequences of the many conserved ORFs. Mertens and collaborators (29) reported that although the HCMV UL78 gene was highly conserved among clinical isolates, the gene was dispensable for replication in fibroblasts and a renal artery organ-culture system. Ruan and coworkers (22) have reported the occurrence of sequence variation caused by frameshift mutations found in the UL143 gene in all HCMV clinical strains.

Earlier studies involving engineered deletions of defined viral DNA segments so as to test their functions were described. Of potential relevance to HHV-6A deletions retaining viable virus are the studies of Yamanishi and his colleagues, who deleted the sequences encoding the cluster of HHV-6A U3-to-U7 genes (23). They concluded that these genes were not obligatorily required for in vitro viral propagation. The mechanism by which the U1102-N-CB→S with shortened DRs replicated advantageously is currently under study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ester Michael for technical assistance. We thank Zvi Berneman, Darham Ablashi, Zaki Salahuddin, and Robert Gallo for the HHV6A (GS) strain. We thank Koichi Yamanishi and Yasuko Mori at the Japan National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Osaka, Japan, for the HHV-6A-U1102 strain propagated in Japan. We thank the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, for the SupT1 cells from James Hoxie.

Our research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF), the S. Daniel Abraham Institute for Molecular Virology, and the S. Daniel Abraham Chair for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 January 2010.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablashi, D., H. Agut, Z. Berneman, et al. 1993. Human herpesvirus-6 strain groups: a nomenclature. Arch. Virol. 129:363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achour, A., I. Malet, C. Deback, P. Bonnafous, D. Boutolleau, A. Gautheret-Dejean, and H. Agut. 2009. Length variability of telomeric repeat sequences of human herpesvirus 6 DNA. J. Virol. Methods 159:127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borenstein, R., and N. Frenkel. 2009. Cloning human herpes virus 6A genome into bacterial artificial chromosomes and study of DNA replication intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19138-19143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borenstein, R., O. Singer, A. Moseri, and N. Frenkel. 2004. Use of amplicon-6 vectors derived from human herpesvirus 6 for efficient expression of membrane-associated and -secreted proteins in T cells. J. Virol. 78:4730-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrigan, D. R., W. R. Drobyski, S. K. Russler, M. A. Tapper, K. K. Knox, and R. C. Ash. 1991. Interstitial pneumonitis associated with human herpesvirus-6 infection after marrow transplantation. Lancet 338:147-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cermelli, C., R. Berti, S. S. Soldan, M. Mayne, J. M. D'Ambrosia, S. K. Ludwin, and S. Jacobson. 2003. High frequency of human herpesvirus 6 DNA in multiple sclerosis plaques isolated by laser microdissection. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1377-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha, T. A., E. Tom, G. W. Kemble, G. M. Duke, E. S. Mocarski, and R. R. Spaete. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates carry at least 19 genes not found in laboratory strains. J. Virol. 70:78-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Bolle, L., L. Naesens, and E. De Clercq. 2005. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:217-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deiss, L. P., J. Chou, and N. Frenkel. 1986. Functional domains within the a sequence involved in the cleavage-packaging of herpes simplex virus DNA. J. Virol. 59:605-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deiss, L. P., and N. Frenkel. 1986. Herpes simplex virus amplicon: cleavage of concatemeric DNA is linked to packaging and involves amplification of the terminally reiterated a sequence. J. Virol. 57:933-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Luca, D., G. Katsafanas, E. C. Schirmer, N. Balachandran, and N. Frenkel. 1990. The replication of viral and cellular DNA in human herpesvirus 6-infected cells. Virology 175:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downing, R. G., N. Sewankambo, D. Serwadda, R. Honess, D. Crawford, R. Jarrett, and B. E. Griffin. 1987. Isolation of human lymphotropic herpesviruses from Uganda. Lancet ii:390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drobyski, W. R., W. M. Dunne, E. M. Burd, K. K. Knox, R. C. Ash, M. M. Horowitz, N. Flomenberg, and D. R. Carrigan. 1993. Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) infection in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients: evidence of a marrow-suppressive role for HHV-6 in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 167:735-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fotheringham, J., and S. Jacobson. 2005. Human herpesvirus 6 and multiple sclerosis: potential mechanisms for virus-induced disease. Herpes 12:4-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frenkel, N., and E. Roffman. 1995. Human herpesviruses 7, p. 2609-2622. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frenkel, N. 2006. The history of the HSV amplicon: from naturally occurring defective genomes to engineered amplicon vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 6:277-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frenkel, N., and R. Borenstein. 2006. Characterization of the lymphotropic Amplicons-6 and Tamplicon-7 vectors derived from HHV-6 and HHV-7. Curr. Gene Ther. 6:399-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frenkel, N., E. C. Schirmer, G. Katsafanas, and C. H. June. 1990. T-cell activation is required for efficient replication of human herpesvirus 6. J. Virol. 64:4598-4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gompels, U. A., and H. A. Macaulay. 1995. Characterization of human telomeric repeat sequences from human herpesvirus 6 and relationship to replication. J. Gen. Virol. 76:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gompels, U. A., J. Nicholas, G. Lawrence, M. Jones, B. J. Thomson, M. E. Martin, S. Efstathiou, M. Craxton, and H. A. Macaulay. 1995. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology 209:29-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall, C. B., C. E. Long, K. C. Schnabel, M. T. Caserta, K. M. McIntyre, M. A. Costanzo, A. Knott, S. Dewhurst, R. A. Insel, and L. G. Epstein. 1994. Human herpesvirus-6 infection in children. A prospective study of complications and reactivation. N Engl. J. Med. 331:432-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He, R., Q. Ruan, Y. Qi, Y. P. Ma, Y. J. Huang, Z. R. Sun, and Y. H. Ji. 2006. Sequence variability of human cytomegalovirus UL143 in low-passage clinical isolates. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 119:397-402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo, K., H. Nozaki, K. Shimada, and K. Yamanishi. 2003. Detection of a gene cluster that is dispensable for human herpesvirus 6 replication and latency. J. Virol. 77:10719-10724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindquester, G. J., and P. E. Pellett. 1991. Properties of the human herpesvirus 6 strain Z29 genome: G + C content, length, and presence of variable-length directly repeated terminal sequence elements. Virology 182:102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locker, H., and N. Frenkel. 1979. BamI, KpnI, and SalI restriction enzyme maps of the DNAs of herpes simplex virus strains Justin and F: occurrence of heterogeneities in defined regions of the viral DNA. J. Virol. 32:429-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez, C., P. Pellett, J. Stewart, C. Goldsmith, K. Sanderlin, J. Black, D. Warfield, and P. Feorino. 1988. Characteristics of human herpesvirus-6. J. Infect. Dis. 157:1271-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin, M. E., B. J. Thomson, R. W. Honess, M. A. Craxton, U. A. Gompels, M. Y. Liu, E. Littler, J. R. Arrand, I. Teo, and M. D. Jones. 1991. The genome of human herpesvirus 6: maps of unit-length and concatemeric genomes for nine restriction endonucleases. J. Gen. Virol. 72:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McVoy, M. A., D. E. Nixon, S. P. Adler, and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Sequences within the herpesvirus-conserved pac1 and pac2 motifs are required for cleavage and packaging of the murine cytomegalovirus genome. J. Virol. 72:48-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michel, D., I. Milotic, M. Wagner, B. Vaida, J. Holl, R. Ansorge, and T. Mertens. 2005. The human cytomegalovirus UL78 gene is highly conserved among clinical isolates, but is dispensable for replication in fibroblasts and a renal artery organ-culture system. J. Gen. Virol. 86:297-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mlechkovich, G., and N. Frenkel. 2007. Human herpesviruses 6A and 6B (HHV-6A and HHV-6B) cause alterations in E2F1/Rb pathways, E2F1 localization, as well as cell cycle arrest in infected T cells. J. Virol. 81:13499-13508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy, E., D. Yu, J. Grimwood, J. Schmutz, M. Dickson, M. A. Jarvis, G. Hahn, J. A. Nelson, R. M. Myers, and T. E. Shenk. 2003. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14976-14981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noble, P. B., J. H. Cutts, and K. K. Carroll. 1968. Ficoll flotation for the separation of blood leukocyte types. Blood 31:66-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pietilainen, J., J. O. Virtanen, L. Uotila, O. Salonen, M. Koskiniemi, and M. Farkkila. 2009. HHV-6 infection in multiple sclerosis. A clinical and laboratory analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.0278.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Rapaport, D., D. Engelhard, G. Tagger, R. Or, and N. Frenkel. 2002. Antiviral prophylaxis may prevent human herpesvirus-6 reactivation in bone marrow transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 4:10-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salahuddin, S. Z., D. V. Ablashi, P. D. Markham, S. F. Josephs, S. Sturzenegger, M. Kaplan, G. Halligan, P. Biberfeld, F. Wong-Staal, B. Kramarsky, et al. 1986. Isolation of a new virus, HBLV, in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Science 234:596-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirmer, E. C., L. S. Wyatt, K. Yamanishi, W. J. Rodriguez, and N. Frenkel. 1991. Differentiation between two distinct classes of viruses now classified as human herpesvirus 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:5922-5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schleimann, M. H., J. M. Moller, E. Kofod-Olsen, and P. Hollsberg. 2009. Direct repeat 6 from human herpesvirus-6B encodes a nuclear protein that forms a complex with the viral DNA processivity factor p41. PLoS One 4:e7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Severini, A., C. Sevenhuysen, M. Garbutt, and G. A. Tipples. 2003. Structure of replicating intermediates of human herpesvirus type 6. Virology 314:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, S. D., M. Shatsky, P. S. Cohen, R. Warnke, M. P. Link, and B. E. Glader. 1984. Monoclonal antibody and enzymatic profiles of human malignant T-lymphoid cells and derived cell lines. Cancer Res. 44:5657-5660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szostak, J. W., T. L. Orr-Weaver, R. J. Rothstein, and F. W. Stahl. 1983. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell 33:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tait, A. R., and S. K. Straus. 2008. Phosphorylation of U24 from human herpes virus type 6 (HHV-6) and its potential role in mimicking myelin basic protein (MBP) in multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett. 582:2685-2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tedder, R. S., M. Briggs, C. H. Cameron, R. Honess, D. Robertson, and H. Whittle. 1987. A novel lymphotropic herpesvirus. Lancet ii:390-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomson, B. J., S. Dewhurst, and D. Gray. 1994. Structure and heterogeneity of the a sequences of human herpesvirus 6 strain variants U1102 and Z29 and identification of human telomeric repeat sequences at the genomic termini. J. Virol. 68:3007-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vlazny, D. A., A. Kwong, and N. Frenkel. 1982. Site-specific cleavage/packaging of herpes simplex virus DNA and the selective maturation of nucleocapsids containing full-length viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:1423-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wyatt, L. S., N. Balachandran, and N. Frenkel. 1990. Variations in the replication and antigenic properties of human herpesvirus 6 strains. J. Infect. Dis. 162:852-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamanishi, K., Y. Mori, and P. E. Pellett. 2007. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7, p. 2819-2845. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley, Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamanishi, K., T. Okuno, K. Shiraki, M. Takahashi, T. Kondo, Y. Asano, and T. Kurata. 1988. Identification of human herpesvirus-6 as a causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet i:1065-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao, K., S. Honarmand, A. Espinosa, N. Akhyani, C. Glaser, and S. Jacobson. 2009. Detection of human herpesvirus-6 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with encephalitis. Ann. Neurol. 65:257-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]